Abstract

Small animal models in which in vivo HIV-1 infection, pathogenesis, and immune responses can be studied would permit both basic research on the biology of the disease, as well as a system to rapidly screen developmental therapeutics and/or vaccines. To date, the most widely-used models have been the severe combined immunodeficient (SCID)-hu (also known as the thy/liv SCID-hu) and the huPBL-SCID mouse models. Recently three new models have emerged, i.e., the intrasplenic huPBL/SPL-SCID model, the NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mouse model, and the Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse model. Details on the construction, maintenance and HIV-1 infection of these models are discussed.

Keywords: Mouse HIV-1 models, intrasplenic huPBL/SPL-SCID model, NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mouse model, Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse model

1. Introduction

Following the discovery of the HIV-1 virus, great efforts were made to develop rodent models that could mimic the course of the viral infection [reviewed in Ref. (4)]. To date, the most commonly used rodent models in HIV-1 investigation are variations of the severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse, i.e., the SCID-hu (also known as the thy-liv SCID) model (35) and huPBL-SCID model (38). In the SCID-hu mouse, fragments of human fetal thymus and liver are implanted under the kidney capsules of a SCID mouse. Two to 3 months later, a thymus-like conjoint human organ develops which supports long-term multi-lineage thymopoeisis leading to maturation of human thymocytes and circulation of human T-cells in the mouse peripheral blood (4). When large quantities of fetal thymic and liver tissues are implanted under both kidney capsules, significant numbers of human T cells can be detected in the peripheral blood, spleens, and lymph nodes (28). Injection of HIV-1 into the implant or intraperitoneally (i.p.) results in the killing, activation and severe depletion of human CD4+ cells within a few weeks, associated with increased viral load (34). After intraimplant injection of HIV-1, significant HIV-1 infection is detected by quantitative coculture, not only in the hu-thy/liv implant, but in the spleen and peripheral blood as well (14,44). Over time, HIV-1 infection is associated with inversion of the CD4/CD8 ratio of peripheral human T cells or almost complete depletion of the CD4 cells (27). A limitation of this model is that, the implanted tissues infected with HIV-1 are of fetal origin, and thus may not necessarily reflect the structure, function and response to HIV infection of their adult counterparts. Also, although circulating human T-cells persist in the peripheral blood for over a year, no mature B cells can be detected (41,47), and no humoral or cellular immune responses to the viral infection, are induced in this model (4,34). In addition, access to human fetal tissue is required to construct the model; proficient surgical skills are needed to be able to implant the tissue under the kidney capsule; and there is a two month delay following surgery, to allow the implanted tissue to grow to sufficient size, before the mouse can be used.

In the huPBL-SCID model, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are injected into the peritoneum of a SCID mouse resulting in a population of human leukocytes, predominantly T cells, persisting in the peritoneal cavity (38). These cells produce high levels of immunoglobulin (Ig) and are readily infected with HIV-1, with a typical infection persisting for up to 16 weeks associated with a rapid loss of CD4+ T cells (4,39). Over time, however, the range of B and T cell receptors become oligoclonal, T cells become anergic to stimulation, and the ability to generate cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) against viral antigens is lost (4,11,37,51,55). Although it has been reported by several groups, the capacity of these mice to produce primary immune responses is not definitive (32,54,55). While the HIV-1 huPBL-SCID model is a valuable tool for studying primary infection with HIV-1 virus, its usefulness is limited by the short-term nature of infection and the absence of a robust primary cellular or humoral responses.

To overcome the restrictions of the aforementioned models, three novel mouse models have been developed over the past 2 years. All of these models have been implemented and utilized in our laboratory and so we present here detailed procedures we have adapted from the original reports for making and using them. These models are:

The intrasplenic huPBL/SPL-SCID model for the assessment of CTL activity in acute HIV-1 infection;

The HIV-1 Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse model;

The HIV-1 NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull model.

1.1. The Intrasplenic huPBL/SPL-SCID Model for the Assessment of CTL Activity in Acute HIV-1 Infection

The initial control of HIV-1 replication during the acute phase of infection is associated with the generation of HIV-1 epitope-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (16,23,29,36,43), and the loss of this CTL activity and/or viral escape from CTL recognition is associated with increased viral loads and accelerated progression to AIDS (17,20,45,59). A strong correlation exists between the potency and specificity of this response and: (a) viral load and clinical outcome (40,42); (b) delay or arrest in disease progression in non-progressors (10,18,46); and (c) protection from infection in some HIV-1-exposed individuals (8,31,48,49). Understanding the in vivo correlates of protection conferred by HIV-1-specific CTLs would be greatly facilitated by the development of an in vivo model of acute infection in which novel therapies and basic research can be performed. Other requirements include that the model be cheap, relatively simple to make, capable of high-throughput studies and have a high degree of experimental reproducibility. A model that fulfills these criteria is the intrasplenic huPBL/SPL-SCID model for the assessment of CTL activity in acute HIV-1 infection (24,25). This model can be used to evaluate in vivo anti-HIV CTL activity during acute HIV-1 infection. PBMCs, isolated from a leukopack, are acutely infected with HIV-1 and then injected into the spleens of SCID mice with or without HLA matched or mismatched HIV-1 specific CTLs. The procedure takes about 10 min per mouse and since so many PBMCs are isolated from one leukopack, it is possible to generate over 20 mice from the same donor resulting in very reproducible results. One week later the spleen is harvested and the number of HIV-1-infected PBMCs is determined by limiting dilution co-culture. The human PBMCs persist in the mouse for at least 2 weeks, are readily detectable by flow cytometry and constitute over 1% of the leukocytes in the SCID mouse spleen.

The model is very similar to the huPBL-SCID mouse, but while the human PBMCs are injected intraperitoneally in the huPBL-SCID model and are predominantly localized to the peritoneal cavity, the hu-PBL/SPL-SCID mouse model utilizes intrasplenic injections. An advantage of directly injecting the CTLs and PBMCs into the spleen is that it localizes both cells into one distinct lymphoid organ, which increases the probability of the two cell types interacting, as opposed to the disseminated and diffuse cell distribution of the cells among the organs when injecting i.p. (24,25). Another advantage of this model is that the location where the CTL and infected cells interact is in a lymphoid organ which parallels what occurs in HIV-1 infected individuals.

1.2. The HIV-1 Rag2−/−γc−/− Mouse Model

Since the initial description of the humanized Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse model (13,33,56,58), several reports have demonstrated that this mouse model can be used in the study of HIV-1 pathogenesis (1–3,15,50,60). The interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor γ chain, referred to as the “gamma common (γc) chain”, plays a critical role in lymphoid development, due to its role as a constituent of the IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15 receptors (6,9). Mouse knock-outs for the γc-chain gene lack natural killer (NK) cells and have diminished T and B cells. Recombinase-Activating-Gene-2 (Rag-2) plays a significant role in V(D)J recombination during B and T cell development, and loss of Rag-2 abrogates the maturation of these cells [reviewed in Ref. (7)]. When γc-chain-null mice are crossed onto a Rag-2 deficient background, residual T and B cells are eliminated. This double knockout lacks functional T, B and NK cells (7,9,52), and is, therefore, permissive for human cell transplantation.

In the HIV-1 Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse model, newborn mice (1–6 days old) are sublethally irradiated and then intrahepatically injected with human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (from human cord blood or human fetal liver). At about 1 month, mice develop de novo B, T and dendritic cells, form primary and secondary lymphoid organs, and are capable of generating functional immune responses (12,56). At 2–8 months of age, mice can be injected either intraperitoneally [i.p. (1–3,15)] intravenously [i.v. (60)] or intrasplenically [i.s. (50)] with HIV-1 leading to productive viral replication, CD4+ T cell depletion, lymphadenopathy, and in some cases anti-HIV-1 immunoglobulin production.

The advantages of using Rag2−/−γc−/− mice are: (a) unlike SCIDs, that are reported to be “leaky”, Rag2−/−γc−/−mice do not generate functional murine T and B cells (5); (b) the engraftment with human lymphocytes promote formation of primary and secondary lymphoid tissues and development of functional immune responses (12,56); and (c) Rag2−/−γc−/− are less radiosensitive, and have longer life span, allowing long-term follow-up (7).

1.3. The HIV-1 NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull Model

Another mouse model, very similar to the Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse, is the nonobese-diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mouse line harboring a complete null mutation of the common cytokine receptor γ chain [NOD/SCID/interleukin 2 receptor (IL2r) γnull]. Just like the Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse, this mouse efficiently supports development of functional human hemato-lymphopoiesis (19,21,22,53,57). An advantage however, over the Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse, however, is that engraftment occurs even when the mice are injected with human CD34+ HSC at 4–6 weeks of age. When purified human CD34+ stem cells are transplanted intravenously into NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull adult or newborn mice, 10–70% repopulation occurs. This model is of particular interest to HIV-1 investigators due to the fact that human IgA-secreting B cells have been found in the intestinal mucosa of these mice. These mice can also be infected with HIV-1 (57).

2. Materials

2.1. The Intrasplenic huPBL/SPL-SCID Model for the Assessment of CTL Activity in Acute HIV-1 Infection

2.1.1. Mice

Specific pathogen-free male and female SCID mice, 8–12 weeks old, are bred and maintained in gnotobiotic conditions.

2.1.2. CTL Clones

HIV-1 specific clones can be either isolated from an HIV infected patients or derived from in vitro immunization. For example, we have seen similar efficiency of this model with the patient derived CTLs: 18030.D23.18, 161jXA14 (HLA-A2 restricted CTLs that recognize the P1777–85 SLYNTVATL (SL9) peptide) and 68A62 [an HLA-A2 restricted CTL that recognizes the POL464–472 ILKEPVHGV (IV9) peptide] clones, generously provided by Dr. Bruce Walker (25), and in vitro immunization derived clones: CC2C and CC5A which are A*0201-restricted SL9-specific CTL clones, generously provided by Dr. June Kan-Mitchell (26).

CTLs are expanded bi-weekly by adding 1 × 105 CTLs to 6 × 106 irradiated HLA-mismatched PBMCs to a well of a 12-well plate in complete media [RPMI (Gibco) +10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Mediatech Inc.) + penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) + Hepes buffer (Gibco) + l-glutamate (Gibco)] containing 30 ng/mL of anti-CD3 (Orthoclone OKT3, Ortho-Biotech). The next day IL-2 (Roche) is added (25 units/mL) and re-added in fresh complete media two to three times a week at 50 units/mL (26). See Note 1.

2.2. The HIV-1 Rag2−/−γc−/− Mouse Model

2.2.1. Mice

RAG2−/−γc−/− mice (see Note 2) are bred and maintained at gnotobiotic conditions. Mating pairs are continually set up since implantation of human stem cells can only be done in newborn mice younger than 7 days. See Note 3.

2.3. The HIV-1 NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull Model

2.3.1. Mice

NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns [within 48 h of birth (21)] or adults [6–10 weeks old (19,22,53,57)] are bred and maintained at gnotobiotic conditions.

3. Methods

3.1. The Intrasplenic huPBL/SPL-SCID Model for the Assessment of CTL Activity in Acute HIV-1 Infection

3.1.1. In Vivo Acute Killing Assay

For more details on this assay, please refer to Ref. (24,25).

Human PBMCs are isolated from a leukopack (yields 500–800 × 106 PBMCs) by collecting the interface of a Ficoll–Paque gradient (typically, 5 mLs of leukopack blood is diluted in 25 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and loaded over 15 mL of Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare) in 50 mL conical tubes and spun for 30 min (stopped without applying brakes) at 25 °C at 1,500 rpm).

Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)-type of the donor PBMCs is determined by flow cytometry, e.g., we typically determine HLA-A2 positivity or negativity with the fluorescein (FITC)-labeled BB7.2 anti HLA-A2 antibody (BD Pharmingen).

The HLA-matched and mismatched PBMCs are activated with phytohemagglutinin [PHA, 5 μg/mL (Sigma)] and IL-2 for 24 h in complete media.

To acutely infect cells, we incubate > 100 × 106 PBMCs with infectious HIV-1, e.g., HIV – 1JR–CSF (800 TCID50) at 37 °C in 1 mL of RPMI (no FBS). Four hours later 9 mL of complete media is added and the cells are incubated at 37 °C overnight.

The next day, the cells are washed and resuspended at 5–10 × 106 in 0.1 mL of sterile cold PBS in an insulin syringe with or without CTLs (the infected PBMCs:CTL ratio is 1:1).

SCID mice are anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100 mg/kg + 40 mg/kg) by i.p. injection, a small incision is made in the skin and peritoneum. The spleen is gently pulled through the hole and injected with the cells. The peritoneal incision is sutured and the skin is stapled closed.

The procedure takes about 10 min and since we isolate so many PBMCs from one leukopack, we are able to generate over 20 mice from the same donor that can be used immediately, resulting in very reproducible results.

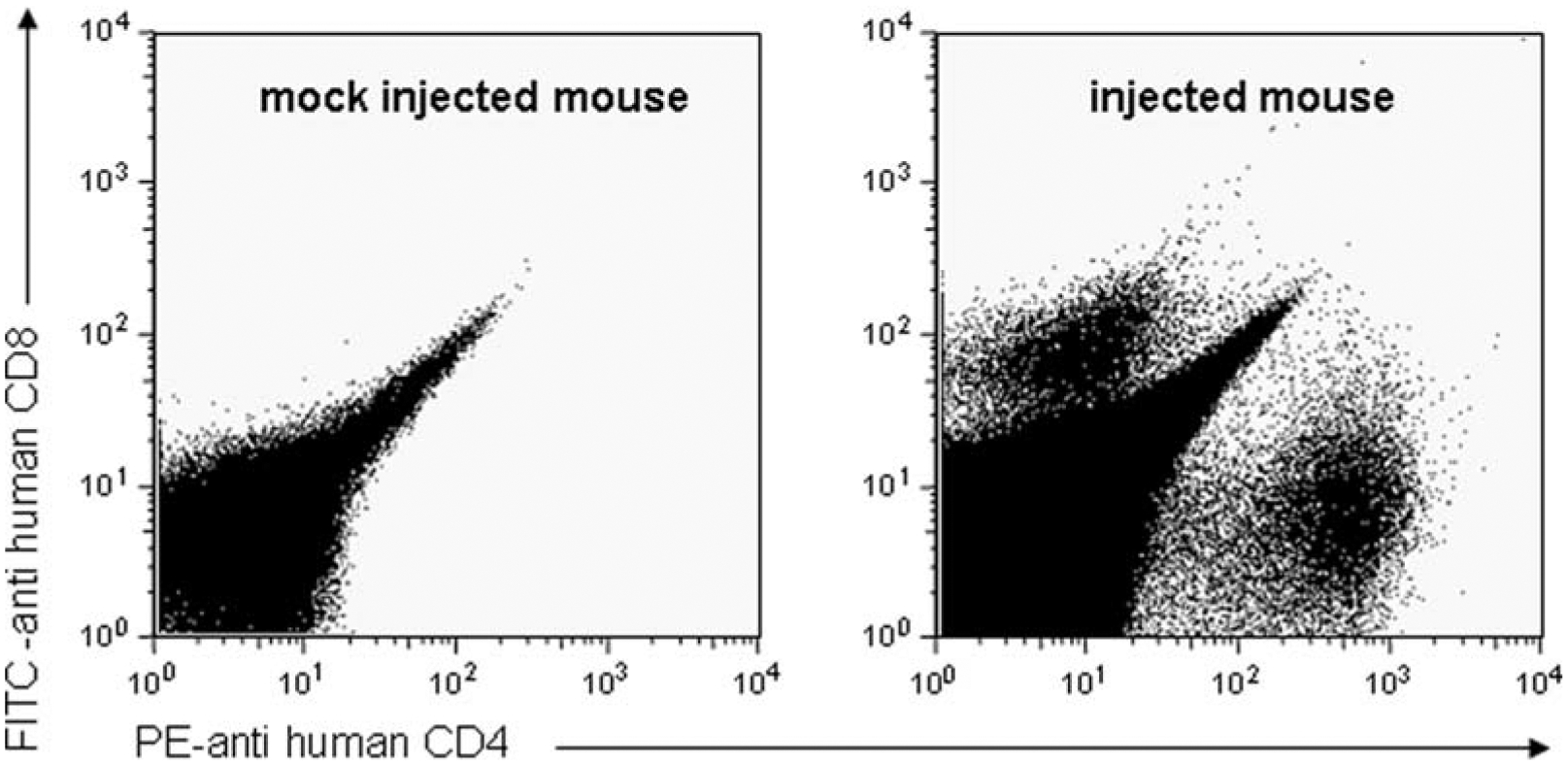

The human PBMCs persist in the mouse for at least 2 weeks, are readily detectible by flow cytometry and constitute over 1% of the cells in the SCID mouse spleen (see Fig. 21.1).

Seven days later mice are killed and the spleens are removed.

A single cell preparation is made by disrupting the spleen and filtering the cells through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon).

The cells are then loaded over a Ficoll–Paque density gradient (see above 3.1.1.1). The interface is collected, washed and cells are counted. See Note 4.

HIV-1-infected cell titer in the spleen is measured by limiting dilution co-culture as described below (see 3.1.2).

Fig. 21.1. Persistence of PBMCs in the spleen of a SCID mouse.

10 × 106 activated PBMCs in 0.1 mL of sterile cold PBS were injected (or mock injected with PBS only) into the spleens of male SCID mice (aged 8–12 weeks) – see Materials and Methods (Sections 2 and 3). Spleens were removed at 1 week and a single cell suspension was prepared. Red blood cells were lysed, and cells were stained for anti-human CD4 (FITC, BD Pharmingen) and CD8 (PE, BD Pharmigen) and DAPI (for viability) and collected on an LSR II.

3.1.2. Limiting Dilution Co-culture

1 × 106 uninfected, PHA + IL-2 activated PBMCs (see 3.1.1.3) are plated in 1 mL of complete media with IL-2 (50 units/ml) in 24-well plates.

Splenocytes are then added to the wells in fivefold limited dilutions, in quadruplicate, ranging from 1 × 106 cells/well to 320 cells/well.

One week later, p24 antigen levels in the supernatants of all the wells are determined by p24-antigen-specific ELISA (see 3.1.3) and the results are expressed in TCID50, i.e., the level of dilution of the cells at which half of the wells (i.e., two of wells of the quadruplicate) contain infectious virus (30). See Fig. 21.2 for an example of results from such a killing assay.

Fig. 21.2. Novel in vivo method for assessment of CTL activity against HIV-1 infected cells.

5–10 × 106 HLA-A*0201 positive or negative cells were acutely infected with HIV-1 overnight in complete RPMI. The next day cells were harvested and injected with or without CTLS into the spleens of SCID mice. One week later serial ×5 dilutions, starting at 1 × 106 cells were added to 1 × 106 activated PBMCs in a total of 2 mL of complete media+IL-2. Seven days later supernatants were collected and p24 ELISA was done. The results presented are the means of three experiments done in duplicate.

3.1.3. p24 ELISA

Typically, a commercial p24 kit can be used. In the past we have successfully used the Alliance HIV-1 P24 ANTIGEN ELISA Kit (Perkin Elmer) but it is also possible to use a lab-generated ELISA to measure p24 antigen concentrations without the kit (24):

For the lab-generated ELISA, MaxiSorp ELISA plates (NUNC) are coated for 1 h at 37 °C, with 100 μL of anti-p24 HIV-1 monoclonal antibody (1 μg/mL; ImmunoDiagnostics) in 0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer pH 8.5 and blocked for 2 h at 37 °C with 0.2 mL blocking buffer (0.1% casein in wash buffer (1.44 M NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20, 250 mM Trizma base, pH 7.5).

Plates are aspirated and samples (diluted in blocking buffer) are added and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C.

The plate is washed ×4 with wash buffer, and secondary antibody is added (biotynylated rabbit anti-p24 antibody in blocking buffer – made in-house) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C.

The plate is washed again and Streptavidin–horse radish per-oxidase (BD Pharmingen) is added and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C.

Plates are washed again and substrate is added (0.1 mL of Sigma FAST OPD) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min.

The reaction is stopped with 0.1 mL of 4 N sulfuric acid and read at 490 nm (above background of 650 nm) using an ELISA reader.

3.2. The HIV-1 Rag2−/−γc−/− Mouse Model

3.2.1. Sources of Human Stem Cells

3.2.1.1. Isolation of CD34+ Cells from Human Cord Blood

Human CD34+ stem cells can be isolated from either cord blood or fetal liver.

Human cord blood can be obtained with written parental informed consent from healthy full-term newborns with the approval of the local Institutional Research Board.

The cord blood is loaded over a Ficoll–Paque gradient (typically 15 mL of cord blood is diluted with 15 mL of PBS and then gently loaded over 15 mL of Ficoll) and spun (with no brake) for 30 min at 1,500 rpm at 25 °C. The interface is collected and washed twice with PBS.

CD34+ cells are then enriched using immunomagnetic beads according to manufacturer’s instructions (CD34+ Progenitor Cell Isolation Kit; Miltenyi Biotec). See Note 5.

Cells can either frozen [10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma), in complete media] or transplanted immediately.

Numbers and purity of CD34+ cells are typically evaluated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). CD34+ cell purity is typically > 90% following density gradient and CD34+ enrichment.

3.2.1.2. Isolation of CD34+ Cells from Human Fetal Tissue

Human fetal liver can be obtained from elective abortion after obtaining written informed consent.

Human fetal liver cells are isolated by gentle disruption of the tissue in PBS – typically, we cut the liver up into 1-inch pieces and then disrupt the tissue with the plunger of a 10-mL syringe. We then collect the single cell suspension into the 10-mL syringe and filter it twice through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon).

The cells are then centrifuged and washed again with PBS. We typically load cells derived from one liver into 10 50-mL conical tubes.

These cells are then layered over Ficoll (as described above) and density gradient centrifuged.

The interface is collected and washed of any residual Ficoll.

CD34+ cells are then enriched by using immunomagnetic beads according to manufacturer’s instructions (CD34+ Progenitor Cell Isolation Kit; Miltenyi Biotec).

Cells can either frozen (10% DMSO in complete media) or transplanted immediately.

Numbers and purity of CD34+ cells are typically evaluated by FACS. CD34+ cell purity is typically > 90% following density gradient and CD34+ enrichment – see Fig. 21.3.

Fig. 21.3. CD34 enrichment.

Single cell preparations are made from human fetal liver by gentle disruption of the tissue in PBS. The single cell preparation is then collected and loaded over Ficoll and density gradient centrifuged. The interface is collected and washed of any residual Ficoll. CD34+ cells are then enriched by using immunomagnetic beads according to manufacturer’s instructions (CD34+ Progenitor Cell Isolation Kit; Miltenyi Biotec). Cells can either frozen (10% DMSO in complete media) or transplanted immediately. Numbers and purity of CD34+ cells are typically evaluated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

3.2.2. Transplantation of Human CD34+ Cells into Rag2−/−γc−/−

Newborn mice are irradiated within 1 week of age (usually at day 1–3 following birth) with sub-lethal irradiation doses that range between 3.50 and 5 Gy (1–3,15,50,60), others have also demonstrated that intrapartum busulfan administration to pregnant dams results in higher engraftment (15 mg/kg administered subcutaneously as a 20% DMSO solution at day 18 postcoitus) (15).

At 1–5 h postirradiation, mice are transplanted with the CD34+ cells in 0.03–0.1 mL of PBS by intrahepatic injection. When CD34+ cells are isolated from cord blood, animals typically receive 0.01–0.6 × 106 cells (12,15,60), while when CD34+ cells are isolated from fetal liver, animals typically receive 1–5 × 106 cells (1,3,50,60). The dark colored liver is easily discernible through the skin of the pup, making this injection technically easy. See Note 6.

3.2.3. Analysis of Engraftment

At 1–2 months of age, peripheral blood is collected by retro-orbital or tail vein bleeding.

Red blood cells are lysed by suspending the collected blood in Ammonium Chloride (8 g/mL) for 10 min. The cells are then washed twice with PBS, and stained with anti-human CD45, CD4, CD8, CD14 (or CD11b), CD19 (BD Bioscience) and any other marker of interest in FACs buffer (1 g/L NaN3). In order to see significant populations, at least 1,000,000 cells usually need to be collected.

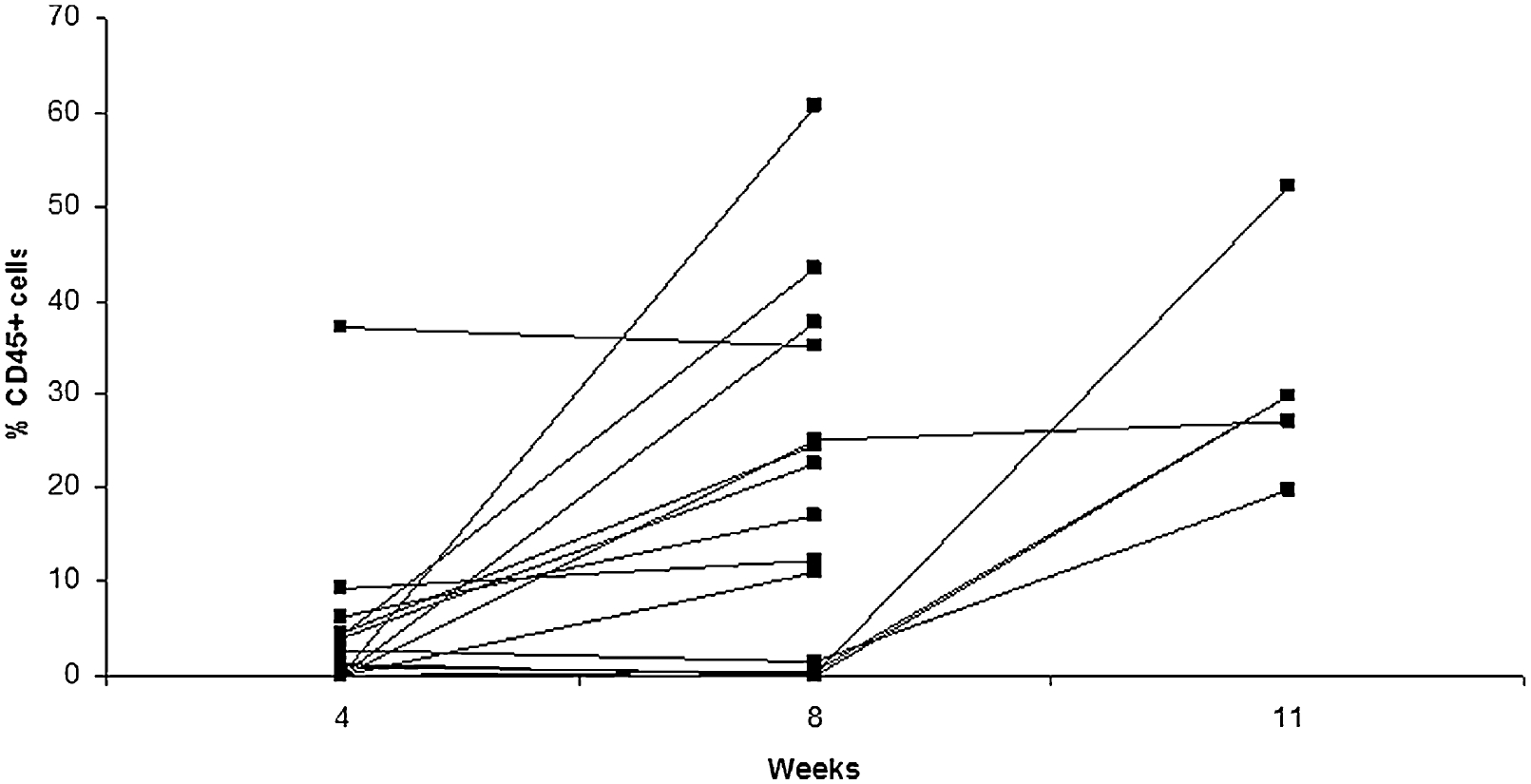

Human CD45+ peripheral blood cell percentages are extremely variable, being as low as 1% and as high as 80% (1–3,12,15,56,60). We typically consider a mouse that has at least 1% CD45+ cells of the lymphocyte gate to be engrafted – see Fig. 21.4.

The mice are then infected by injection with HIV-1.

Fig. 21.4. Human Cell Engraftment in Rag2−/−γc−/−.

CD34+ human hematopoietic stem cells were injected intrahepatically into 1- to 7-day-old new born Rag2−/− γc−/− mice. Mice were bled at 4, 8 and/or 11 weeks and PBMCs were stained for the expression of anti-human CD45. Presented is the percentage of anti-human CD45+ cells for 12 individual mice.

3.2.4. HIV-1 Infection of Humanized RAG2−/−γc−/−

3.2.5. Analysis of HIV-1 Infection and Immune Response

Mice are killed at different time points following infection and peripheral blood, liver, spleen, bone marrow, thymus, lungs and lymph nodes are typically harvested.

3.2.5.1. HIV-1 Infection Analysis

Plasma viral load is typically monitored with the Roche Amplicor Monitor v.1.5. assay (Roche Diagnostics).

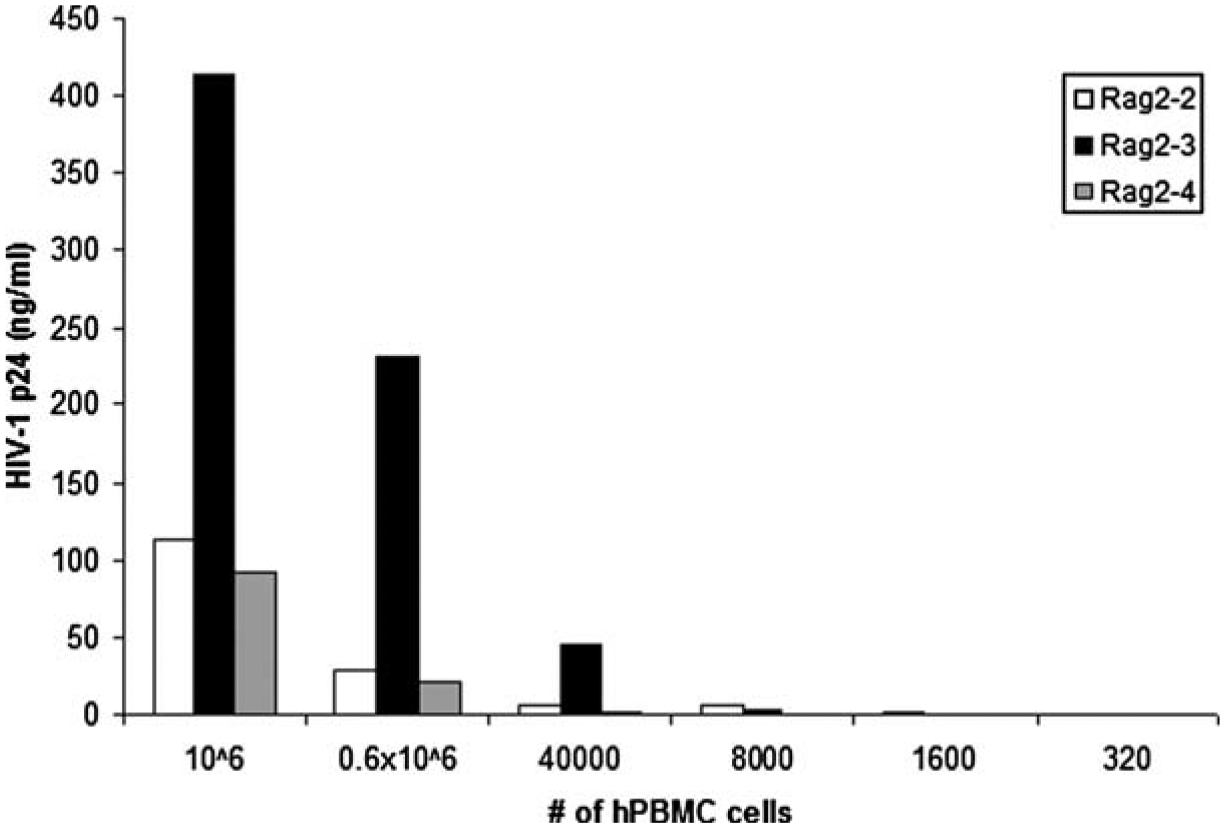

Infectious HIV-1 in all other organs is typically detected by limiting dilution co-culture of these cells with PHA/IL-2 activated PBMCs as described above (see 3.1.2) – see Fig. 21.5.

In addition, several groups have performed immunohistochemistry with anti-p24 antibody on paraffin sections showing successful infections of nearly all organs.

Fig. 21.5. HIV-1 titer of splenocytes isolated from Rag2−/− γc−/− infected intrasplenically.

HIV-1JR−CSF (800 TCID50) was injected intrasplenically into humanized Rag2−/− γc−/−. For to 8 weeks following infection, splenocytes were harvested and cocultured by limiting dilution with 1 × 106 activated human PBMCs. One week later, supernatants were collected and assayed for productive HIV-1 infection by measuring p24 concentration by ELISA. Presented are the data of three separate mice.

3.2.5.2. CD4+ Cells Depletion

There are two ways to determine CD4+ cell depletion:

In order to determine CD4+ depletion, all tissues are usually stained for CD45, CD4, CD8, etc. and FACSed. A ratio is then made between the CD4+ population of the CD45 gated cells, and the CD8+ population of the CD45 cells. Before HIV-1 infection this is typically 2:1 to 4:1 (within normal range observed in healthy humans) – this however inverts following HIV-1 infection in most reports (1–3,15).

Another way of determining CD4+ cell decline is to use the GUAVA Easycytes kit according to manufacturer’s instructions for a readout of number of CD4+ cells/mL of blood (60).

3.2.5.3. Measuring Humoral Immune Responses to the HIV-1 Infection

The levels of human IgM and human IgG in peripheral blood has been determined by some groups. In one report, IgG against p34, gp41, p52, p58, and gp160 was found in one animal by Western blot (2). In another, no antibodies were found against HIV-1 proteins (1). Another group found no antibodies to HIV-1 proteins but did show that these mice could launch an immune response when vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae type b with the Act HIB (Aventius Paster Inc.) conjugate vaccine (15). See Notes 7 and 8.

3.3. The HIV-1 NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull Model

3.3.1. Sources of Human Stem Cells

See the description provided in Section 3.2.1.

3.3.2. Transplantation of Human CD34+ Cells into NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull

Mice are sub-lethally irradiated [1 Gy for newborns (21) and between 2.4 and 3 Gy for adults (19,22,53,57)].

Within 12 h of irradiation, mice are intravenously transplanted with 0.01–1.5 × 106 CD34+ cells. Newborns injected via a facial vein (21), while adults are injected via a tail vein (19,22,53,57).

3.3.3. Analysis of engraftment

See the description provided in Section 3.2.3.

3.3.4. HIV-1 infection of humanized NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull

In one report, mice were injected i.v. (57) with HIV-1 virus at titers that ranged between 200 and 65,000 TCID50.

3.3.5. Analysis of HIV-1 infection and immune response

See the description provided in Section 3.2.5.

4. Notes

Fresh media should always be prepared when thawing CTLs – we find this is best for CTL viability.

Most report that is best to use Rag2−/−γc−/− on a BALB/c background.

We find that the highest repopulation occurs when mice are injected within the first 3 days of life.

We typically layer the spleens in small volumes over ficoll, i.e., 1 mL of splenocytes (in PBS) over 1 mL of Ficoll.

It is very important to filter chord blood derived cells to ensure that they do not clog the filters.

One technical problem we have encountered in making these mice is that handling the mice following irradiation and injection may cause the mother to reject the pups and stop nursing them. We have circumvented this, by smearing the pups with urine collected from the mother before returning the pups to the mother.

Though at least two groups have attempted to look at HIV-specific cellular immune responses in both the HIV-1 Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse model and the HIV-1 NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull model, to date, no-one has successfully shown the emergence or presence of such an immune response (1,2).

To date no-one has shown mucosal immunity in either the HIV-1 Rag2−/−γc−/− mouse model or the HIV-1 NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull model which could prove invaluable in an HIV-1 model.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AI67136, and the Einstein/MMC Center for AIDS Research AI51519).

References

- 1.An DS, Poon B, Fang RH, et al. (2007) Use of a novel chimeric mouse model with a functionally active human immune system to study human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Clin Vaccine Immunol 14, 391–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baenziger S, Tussiwand R, Schlaepfer E, et al. (2006) Disseminated and sustained HIV infection in CD34+ cord blood cell-transplanted Rag2−/−gamma c−/− mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 15951–15956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berges BK, Wheat WH, Palmer BE, et al. (2006) HIV-1 infection and CD4 T cell depletion in the humanized Rag2−/−gamma c−/− (RAG-hu) mouse model. Retrovirology 3, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borkow G (2005) Mouse models for HIV-1 infection. IUBMB Life 57, 819–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosma MJ, Carroll AM (1991) The SCID mouse mutant: definition, characterization, and potential uses. Annu Rev Immunol 9, 323–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao X, Shores EW, Hu-Li J, et al. (1995) Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor gamma chain. Immunity 2, 223–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chicha L, Tussiwand R, Traggiai E, et al. (2005) Human adaptive immune system Rag2−/−gamma(c)−/− mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1044, 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Maria A, Cirillo C, Moretta L (1994) Occurrence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific cytolytic T cell activity in apparently uninfected children born to HIV-1-infected mothers. J Infect Dis 170, 1296–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiSanto JP, Muller W, Guy-Grand D, et al. (1995) Lymphoid development in mice with a targeted deletion of the interleukin 2 receptor gamma chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92, 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferbas J, Kaplan AH, Hausner MA, et al. (1995) Virus burden in long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a determinant of anti-HIV CD8+ lymphocyte activity. J Infect Dis 172, 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia S, Dadaglio G, Gougeon ML (1997) Limits of the human-PBL-SCID mice model: severe restriction of the V beta T-cell repertoire of engrafted human T cells. Blood 89, 329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gimeno R, Weijer K, Voordouw A, et al. (2004) Monitoring the effect of gene silencing by RNA interference in human CD34+ cells injected into newborn RAG2−/− gammac−/− mice: functional inactivation of p53 in developing T cells. Blood 104, 3886–3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman JP, Blundell MP, Lopes L, et al. (1998) Enhanced human cell engraftment in mice deficient in RAG2 and the common cytokine receptor gamma chain. Br J Haematol 103, 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein H, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Katopodis NF, et al. (1996) SCID-hu mice: a model for studying disseminated HIV infection. Semin Immunol 8, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorantla S, Sneller H, Walters L, et al. (2007) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pathobiology studied in humanized BALB/c-Rag2−/−gammac−/− mice. J Virol 81, 2700–2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotch F, Gallimore A, McMichael A (1996) Cytotoxic T cells–protection from disease progression–protection from infection. Immunol Lett 51, 125–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goulder PJ, Phillips RE, Colbert RA, et al. (1997) Late escape from an immun-odominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat Med 3, 212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrer T, Harrer E, Kalams SA, et al. (1996) Cytotoxic T lymphocytes in asymptomatic long-term nonprogressing HIV-1 infection. Breadth and specificity of the response and relation to in vivo viral quasispecies in a person with prolonged infection and low viral load. J Immunol 156, 2616–2623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiramatsu H, Nishikomori R, Heike T, et al. (2003) Complete reconstitution of human lymphocytes from cord blood CD34+ cells using the NOD/SCID/gammacnull mice model. Blood 102, 873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huynen MA, Neumann AU (1996) Rate of killing of HIV-infected T cells and disease progression. Science 272, 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishikawa F, Yasukawa M, Lyons B, et al. (2005) Development of functional human blood and immune systems in NOD/SCID/IL2 receptor {gamma} chain(null) mice. Blood 106, 1565–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K, et al. (2002) NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood 100, 3175–3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jassoy C, Walker BD (1997) HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and the control of HIV-1 replication. Springer Semin Immunopathol 18, 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joseph A, Zheng JH, Follenzi A, et al. (2008) Lentiviral vectors encoding human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell receptor genes efficiently convert peripheral blood CD8 T lymphocytes into cytotoxic T lymphocytes with potent in vitro and in vivo HIV-1-specific inhibitory activity. J Virol 82, 3078–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph A, Zheng J, Patel M, et al. (2007) An intrasplenic huPBL/SPL SCID model for the study of acute in vivo CTL activity against HIV-1 infected cells. In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kan-Mitchell J, Bisikirska B, Wong-Staal F, et al. (2004) The HIV-1 HLA-A2-SLYNTVATL is a help-independent CTL epitope. J Immunol 172, 5249–5261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kollmann TR, Kim A, Pettoello-Mantovani M, et al. (1995) Divergent effects of chronic HIV-1 infection on human thymocyte maturation in SCID-hu mice. J Immunol 154, 907–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kollmann TR, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Zhuang X, et al. (1994) Disseminated human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) infection in SCID- hu mice after peripheral inoculation with HIV-1. J Exp Med 179, 513–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koup RA, Safrit JT, Cao Y, et al. (1994) Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J Virol 68, 4650–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaBarre DD, Lowy RJ (2001) Improvements in methods for calculating virus titer estimates from TCID50 and plaque assays. J Virol Methods 96, 107–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langlade-Demoyen P, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Ferchal F, et al. (1994) Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) nef-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in noninfected heterosexual contact of HIV-infected patients. J Clin Invest 93, 1293–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markham RB, Donnenberg AD (1992) Effect of donor and recipient immunization protocols on primary and secondary human antibody responses in SCID mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Infect Immun 60, 2305–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazurier F, Fontanellas A, Salesse S, et al. (1999) A novel immunodeficient mouse model–RAG2 x common cytokine receptor gamma chain double mutants–requiring exogenous cytokine administration for human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment. J Interferon Cytokine Res 19, 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCune JM (1991) SCID mice as immune system models. Curr Opin Immunol 3, 224–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCune JM, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, et al. (1988) The SCID-hu mouse: murine model for the analysis of human hematolymphoid differentiation and function. Science 241, 1632–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMichael AJ, Rowland-Jones SL (2001) Cellular immune responses to HIV. Nature 410, 980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosier DE (1996) Modeling AIDS in a mouse. Hosp Pract (Minneap), 31, 41–48, 53,–45, 59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosier DE (1996) Viral pathogenesis in hu-PBL-SCID mice. Semin Immunol 8, 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, et al. (1988) Transfer of a functional human immune system to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nature 335, 256–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, et al. (1991) Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human-PBL-SCID mice. Science 251, 791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musey L, Hughes J, Schacker T, et al. (1997) Cytotoxic-T-cell responses, viral load, and disease progression in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med 337, 1267–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Namikawa R, Weilbaecher KN, Kaneshima H, et al. (1990) Long-term human hematopoiesis in the SCID-hu mouse. J Exp Med 172, 1055–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogg GS, Jin X, Bonhoeffer S, et al. (1998) Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science 279, 2103–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pantaleo G, Demarest JF, Soudeyns H, et al. (1994) Major expansion of CD8+ T cells with a predominant V beta usage during the primary immune response to HIV. Nature 370, 463–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pettoello-Mantovani M, Kollmann TR, Katopodis NF, et al. (1998) thy/liv-SCID-hu mice: a system for investigating the in vivo effects of multidrug therapy on plasma viremia and human immunodeficiency virus replication in lymphoid tissues. J Infect Dis 177, 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips RE, Rowland-Jones S, Nixon DF, et al. (1991) Human immunodeficiency virus genetic variation that can escape cytotoxic T cell recognition. Nature 354, 453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rinaldo C, Huang XL, Fan ZF, et al. (1995) High levels of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) memory cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity and low viral load are associated with lack of disease in HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors. J Virol 69, 5838–5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roncarolo MG, Carballido JM, Rouleau M, et al. (1996) Human T-and B-cell functions in SCID-hu mice. Semin Immunol 8, 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rowland-Jones S, Sutton J, Ariyoshi K, et al. (1995) HIV-specific cytotoxic T-cells in HIV-exposed but uninfected Gambian women. Nat Med 1, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowland-Jones SL, Dong T, Fowke KR, et al. (1998) Cytotoxic T cell responses to multiple conserved HIV epitopes in HIV-resistant prostitutes in Nairobi. J Clin Invest 102, 1758–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sango K, Joseph A, Buhl S, et al. (2007) HIV-1 specific humoral responses induced by intrasplenic infection of HIV-1 in a humanized Rag2−/−gamma-common-chain−/− mouse model. In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saxon A, Macy E, Denis K, et al. (1991) Limited B cell repertoire in severe combined immunodeficient mice engrafted with peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from immunodeficient or normal humans. J Clin Invest 87, 658–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam KP, et al. (1992) RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell 68, 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, et al. (2005) Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J Immunol 174, 6477–6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Somasundaram R, Jacob L, Adachi K, et al. (1995) Limitations of the severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model for study of human B-cell responses. Scand J Immunol 41, 384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tary-Lehmann M, Saxon A, Lehmann PV (1995) The human immune system in hu-PBL-SCID mice. Immunol Today 16, 529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Traggiai E, Chicha L, Mazzucchelli L, Bronz L, Piffaretti JC, Lanzavecchia A and Manz MG (2004) Development of a human adaptive immune system in cord blood cell-transplanted mice. Science 304, 104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watanabe S, Terashima K, Ohta S, et al. (2007) Hematopoietic stem cell-engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2Rgamma null mice develop human lymphoid systems and induce long-lasting HIV-1 infection with specific humoral immune responses. Blood 109, 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weijer K, Uittenbogaart CH, Voordouw A, et al. (2002) Intrathymic and extrathymic development of human plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors in vivo. Blood 99, 2752–2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wolinsky SM, Korber BT, Neumann AU, et al. (1996) Adaptive evolution of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 during the natural course of infection. Science 272, 537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang L, Kovalev GI, Su L (2007) HIV-1 infection and pathogenesis in a novel humanized mouse model. Blood 109, 2978–2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]