Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 2

In this update we have corrected the references to Figure 5 in the results section.

Abstract

Background

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) plays important roles in intestinal homeostasis, limiting tumour growth and promoting differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Spineless, the Drosophila homolog of AHR, has only been studied in the context of development but not in the adult intestine.

Methods

The role of Spineless in the Drosophila midgut was studied by overexpression or inactivation of Spineless in infection and tumour models and RNA sequencing of sorted midgut progenitor cells.

Results

We show that spineless is upregulated in the adult intestinal epithelium after infection with Pseudomonas entomophila ( P. e.). Spineless inactivation increased stem cell proliferation following infection-induced injury. Spineless overexpression limited intestinal stem cell proliferation and reduced survival after infection. In two tumour models, using either Notch RNAi or constitutively active Yorkie, Spineless suppressed tumour growth and doubled the lifespan of tumour-bearing flies. At the transcriptional level it reversed the gene expression changes induced in Yorkie tumours, counteracting cell proliferation and altered metabolism.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate a new role for Spineless in the adult Drosophila midgut and highlight the evolutionarily conserved functions of AHR/Spineless in the control of proliferation and differentiation of the intestinal epithelium.

Keywords: aryl hydrocarbon receptor, spineless, Drosophila, intestinal epithelium, tumour suppressor

Plain language summary

The transcription factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) plays important roles in the intestine, limiting tumour growth and promoting the normal epithelial lining. Spineless, the fruit fly homolog of AHR, has only been studied in the context of embryonic development but not in the intestine of adult flies. Here, we show that spineless is upregulated in the adult intestinal epithelium after infection with a bacterium. Blocking Spineless function increased stem cell proliferation after bacterial infection. Increasing Spineless had the opposite effect and limited intestinal stem cell proliferation. It also reduced survival after bacterial infection. In two separate tumour models, Spineless suppressed tumour growth and doubled the lifespan of tumour-bearing flies. Increasing Spineless reversed the gene expression changes induced in tumours, counteracting cell proliferation and changes to the cellular metabolism. These findings demonstrate a new role for Spineless in the adult fruit fly midgut and highlight the evolutionarily conserved functions of mammalian AHR and fruit fly Spineless in the control of proliferation and differentiation of the intestinal epithelium.

Introduction

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor with barrier-protective roles in the intestine 1 . AHR is an environmental sensor of the basic helix-loop-helix Per-Arnt-Sims (bHLH-PAS) family that binds ligands derived from the diet, microbial metabolism or industrial sources. Ligand binding leads to release of AHR from its chaperone complex and nuclear translocation 2 . AHR then dimerizes with AHR nuclear translocator (ARNT) for DNA binding at canonical binding sites. AHR is widely expressed in many intestinal immune cells, stromal cells and the intestinal epithelium 3 , where it is important in the anti-bacterial defence and in limiting tumour growth 1 . Ablation of AHR in the intestinal epithelium of mice leads to increased susceptibility to infection with Citrobacter rodentium and increased malignant transformation in an AOM-DSS model 4 . AHR is needed to end the regenerative response of the intestinal epithelium after injury to allow the epithelial barrier to return to its mature state 5 . Treatment of mice with AHR ligand-rich diet was shown to be beneficial in tumour models and epithelial healing after injury with DSS 4, 5 .

Spineless is the closest Drosophila homolog to AHR and binds the same DNA sequence 6, 7 . Amino-acid identity between AHR and Spineless is 41% overall but substantially higher in the PAS domains and reaches 70% in the DNA-binding site 8 . The lowest similarity is found in the ligand-binding domain. This is in line with the idea that Spineless is a ligand-independent transcription factor that cannot bind prototypic AHR ligands like dioxin and does not require ligands for nuclear translocation 9, 10 . Moreover, Drosophila is unaffected by the prototypical AHR ligand dioxin 11 . Akin to the AHR-ARNT dimer in vertebrates, Spineless forms a heterodimer with the bHLH-PAS family member Tango and this heterodimer then translocates to the nucleus to bind to dioxin-response elements 7 . Another line of evidence for strong evolutionary conservation between these homologs comes from a study showing that AHR could rescue the developmental phenotypes of Spineless mutants in Drosophila 11 . The authors also demonstrated that AHR/Spineless functions in Drosophila are highly dependent on gene dosage of Tango or ARNT and that dioxin treatment could enhance AHR functions in murine AHR-transgenic Drosophila. Thus, Drosophila Spineless might be a useful model to study evolutionarily conserved AHR functions.

The functions of Spineless have been studied extensively in Drosophila development. Spineless was first identified for controlling antenna development, with mutants causing the aristapedia phenotype 12 . Spineless has since been shown to function together with Tango to control antennal identity and the development of tarsal segments of the leg 7, 8, 13, 14 . Spineless also plays important roles in regulating dendrite morphology in neurons 15 , the development of sternopleural bristles 16 , and photoreceptor specification in the retina 17– 21 . Few studies have focused on the function of Spineless in adult flies and the role of Spineless in the adult intestine has not been studied.

The Drosophila midgut consists of a single layer of epithelial cells surrounded by a basement membrane and visceral muscle. Similar to the mammalian intestine, the epithelium regenerates from intestinal stem cells (ISC), which give rise to transient enteroblasts (EB) and further differentiate into mature absorptive enterocytes 22 . The Drosophila intestine also contains a secretory lineage, the enteroendocrine cells. ISC are characterized by expression of Escargot (Esg) and Delta (Dl) and suppression of Notch (N) signalling for their maintenance 23, 24 . Upon asymmetric division and differentiation into EB, cells downregulate Delta, activate Notch signalling and induce Suppressor of Hairless (Su(H)). Differentiation into Pou domain protein 1 (Pdm1)-positive enterocytes is driven by Jak/Stat signalling, Notch activation and a downregulation of Esg. Prospero (Pros) is induced during differentiation into enteroendocrine cells. A range of local, systemic, and environmental stimuli are integrated through multiple signalling pathways (including Notch, Jak/Stat, Egfr and Hippo) to govern ISC proliferation and differentiation and to maintain the epithelial barrier and its function 22 . Many of these pathways have also been shown to interact with AHR to regulate stem cell maintenance and differentiation in the mammalian intestinal epithelium 1, 4, 5, 25, 26 .

Given the critical roles that AHR plays in the mammalian intestine, we hypothesized that Spineless may have evolutionarily conserved functions in the Drosophila midgut. We found that spineless is indeed upregulated in the adult midgut after bacterial infection where it limits the regenerative response and functions as a tumour suppressor in two independent models.

Methods

Fly Stocks and manipulation of midgut progenitor cells

The following transgenic lines were used: rotund-Gal4, Su(H)-Gal4, Su(H)-Gal80, esg-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts, UAS-GFP, UAS-GFP.NLS (nuclear localization signal), UAS- N RNAi (#GD27228, Vienna Drosophila Resource Centre), UAS- yki act (w*;; UAS- yki.S111A.S168A.S250A.V5; #228817 Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) 27 .

The following fly lines were generated in this study: UAS-ssHA, ssGFP, UAS-anti-GFP.

Esg ts refers to tub-GAL80 ts , esg-GAL4 which was used to express transgenes in midgut ISC and EB populations. We used the following driver to limit transgene expression to ISC ( esg-Gal4, Su(H)-Gal80, tub-Gal80 ts ) or EB ( Su(H)-Gal4, tub-Gal80 ts ) only. Drivers were crossed to w 1118 wildtype flies or UAS-GFP as control. To inactivate spineless in midgut progenitor cells, we used flies with ssGFP (homozygous), tub-GAL80 ts , esg-GAL4, UAS-anti-GFP. Flies with ssGFP (homozygous), tub-GAL80 ts , esg-GAL4 without UAS-anti-GFP served as control.

Crosses were set up at 18°C to activate Gal80 ts, thus restricting the expression of the Gal4-induced transgenes. Adult female offspring were selected at 0–4 days of age and shifted to 29°C to induce expression of transgenes. During incubation at 29°C, flies were transferred onto fresh food every 3–4 days.

Genetic modification of flies

To generate flies expressing Ss fused to GFP ( ssGFP), the ss locus was modified by CRISPR/Cas9-stimulated homologous recombination. DNA encoding eGFP followed by a lox-3Pax3-CHE-lox cassette was inserted just before the stop codon as described 28 . These following primers where used to generate the CFD4ss vector that expresses the gRNA targets sites under the control of U1 and U6 promoters. Cas9 targets overlapping with ss stop codon are in bold. CFD4ssT1=TATATATAGGAAAGATATCCGGGTGAActtcG cgtcttCTAgcggtggccgGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAG, CFD4ssT2=attttaacttgctatttctagctctaaaac ccgcTAGaagacgaatagaCgacgTTAAATTGAAAATAGGTC. The IOssGFP@CTV-Pax-Cherry vector was designed to insert GFP before ss stop codon. These oligonucleotides were used for homology arm 1: HR1F= CCCGGGCTAATTATGGGGTGTCGCCCTTCGGCAGTGGCTATGGAAGTCCAACATCTACGC, HR1R= cccggtgaacagctcctcgcccttgctcacGCGGTGGCCGTGGTGCAGGTGATGCGA. These primers were used for homology arm 2: HR2F= gtataatgtatgctatacgaagttatggcagTAGaagacgaatagattgcaccagtaat, HR2R= GCCCTTGAACTCGATTGACGCTCTTCGACttgcttgggatcaacggggattggc. These 2 PCRs fragments where inserted into the IOGFP@CTV-Pax-Cherry vector using Gibson reaction. The proper insertion of GFP before the stop codon was confirmed by PCR using genomic DNA from ssGFP candidates using the following primers: scr geno ss5’armF= gtggctactacacggattatccc, scr eGFPR= cgggcagcttgccggtggtgc, scr CHEF= cagtacgaacgcgccgaggg, scr geno ss3'armR= ttggcgctacaaaccgaagcc.

To generate UAS-anti-GFP, we fused the CD8 ORF (NCBI Ref.: NP_001074579) to GBP (vhhGFP4) 29 separated by a Gly/Ser linker and inserted this new ORF in pUAST.

The following primers were used to generate the CD8NB PCR fragment using a vector containing the CD8-NB ORF (see below): NotCD8F = agatct GCGGCCGCgcaataATGGCCTCACCGTTGACCCGC, XbaNBR = GCCT tctagaTCAGTCGACCGGTGGATCCCG. The CD8-NB ORF:

ATGGCCTCACCGTTGACCCGCTTTCTGTCGCTGAACCTGCTGCTGCTGGGTGAGTCGATTATCCTGGGGAGTGGAGAAGCTAAGCCACAGGCACCCGAACTCCGAATCTTTCCAAAGAAAATGGACGCCGAACTTGGTCAGAAGGTGGACCTGGTATGTGAAGTGTTGGGGTCCGTTTCGCAAGGATGCTCTTGGCTCTTCCAGAACTCCAGCTCCAAACTCCCCCAGCCCACCTTCGTTGTCTATATGGCTTCATCCCACAACAAGATAACGTGGGACGAGAAGCTgaattcGTCGAAACTGTTTTCTGCCATGAGGGACACGAATAATAAGTACGTTCTCACCCTGAACAAGTTCAGCAAGGAAAACGAAGGCTACTATTTCTGCTCAGTCATCAGCAACTCGGTGATGTACTTCAGTTCTGTCGTGCCAGTCCTTCAGAAAGTGAACTCTACTACTACCAAGCCAGTGCTGCGAACTCCCTCACCTGTGCACCCTACCGGGACATCTCAGCCCCAGAGACCAGAAGATTGTCGGCCCCGTGGCTCAGTGAAGGGGACCGGATTGGACTTCGCCTGTGATATTTACATCTGGGCACCCTTGGCCGGAATCTGCGTGGCCCTTCTGCTGTCCTTGATCATCACTCTCATCTGCTACCACAGCCGCGGATCCggcGGAggCTCGAGcGGAggcGGTATGGCCGATGTGCAGCTGGTGGAGTCTGGGGGAGCCTTGGTGCAGCCGGGGGGGTCTCTGAGACTCTCCTGTGCAGCCTCTGGATTCCCCGTCAATCGCTATAGTATGAGGTGGTACCGCCAGGCTCCAGGGAAGGAGCGCGAGTGGGTCGCGGGTATGAGTAGTGCTGGTGATCGTTCAAGTTATGAAGACTCCGTGAAGGGCCGATTCACCATCTCCAGAGACGACGCCAGGAATACGGTGTATCTGCAAATGAACAGCCTGAAACCTGAGGACACGGCCGTGTATTACTGTAATGTCAATGTGGGCTTTGAGTACTGGGGCCAGGGGACCCAGGTCACCGTCTCCTCAAGgaattcGATATCAAGCTTATCGATACCGTCGACGGTACCGCGGGCCCGGGATCCACCGGTCGACTGA.

To obtain flies allowing over-expression of HA tagged version of Ss ( UAS-ssHA), we inserted 2 HA tags (before the stop codon) in the ss cDNA (isoform A) 20 . The resulting DNA was inserted in pUAST before p-element-mediated transformation.

The following primers were used to generate the ssHA PCR fragment using ssRA cDNA as a template: NotssF = gatcga GCGGCCGCccctagcaATGAGCCAGCTGGGCACCGTCTAC, Xba2HAssR=gatc tctagaCTAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCATAGGGATAtccgccCGCATAGTCAGGGACGTCGTATGGGTAGCGGTGGCCGTGGTGCAGGTG.

Bacterial infection

Pseudomonas entomophila (stock kindly provided by Bruno Lemaitre) was grown in LB medium at 29°C for 24h. Bacterial culture was centrifuged at 3000xg for 15 min and pellets resuspended in 5% sucrose solution for a final concentration of OD 600=200. 1ml concentrated bacteria solution was added to filter paper placed on top of standard fly food for infection. Flies were shifted to 29°C for 5 days and starved in an empty vial for 2 hours prior to infection. Survival was recorded daily. Survival data from individual experiments are shown in Table 1. Initial experiments with w1118 flies showed that infected flies (n=155) had a median survival of 2 days, but uninfected flies provided with a 5% sucrose solution on filter paper showed no death by day 6 (n=39). For tumour survival experiments with low-dose P. entomophila infection flies were first shifted to 29°C for 1 day, then infected with bacterial solutions concentrated to OD 600=70 in 5% sucrose and returned to normal fly food 24h later. Survival data from individual experiments are shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Summary of survival data from P. entomophila infection experiments.

| experiment # | genotype 1 | genotype 2 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| median

survival (days) |

n | median

survival (days) |

n | ||

| ssGFP, esg ts | ssGFP, esg ts>anti-GFP | ||||

| 1 | 4 | 39 | 4 | 57 | 0.5900 |

| 2 | 2 | 69 | 3 | 60 | 0.0007 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 192 | 2 | 163 | 0.0006 |

| pooled ( Figure 1Q) | 3 | 291 | 3 | 280 | 0.0684 |

| esg ts>GFP | esg ts>GFP, ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 3 | 29 | 2 | 30 | 0.0003 |

| 2 | 2 | 59 | 2 | 60 | 0.2980 |

| 3 | 3 | 271 | 2 | 143 | 0.0002 |

| pooled ( Figure 1R) | 3 | 305 | 2 | 233 | <0.0001 |

| ISC>GFP | ISC>GFP, ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 4 | 200 | 3 | 183 | 0.0002 |

| 2 | 2 | 108 | 2 | 143 | 0.0060 |

| pooled ( Figure 2P) | 4 | 308 | 2 | 326 | 0.0001 |

| EB>GFP | EB>GFP, ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 3 | 131 | 2 | 168 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 2 | 164 | 1 | 171 | 0.0015 |

| pooled ( Figure 2P) | 2 | 295 | 2 | 339 | 0.0001 |

Summary data including the number of flies (n), the median survival, and uncorrected p value of log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test are shown for each individual survival experiment and the pooled data.

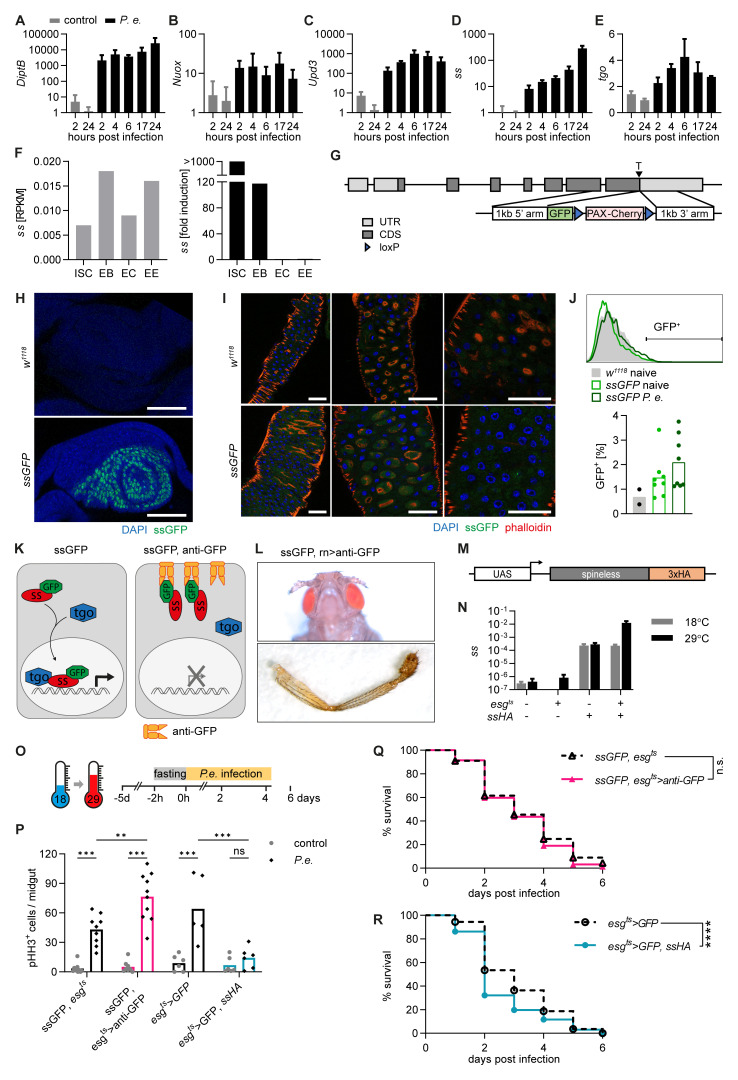

Figure 1. Spineless limits intestinal stem cell proliferation after Pseudomonas entomophila infection.

A-E) Gene expression was determined by qPCR from isolated midguts of w1118 flies at different timepoints after P. entomophila infection. Data are from one experiment with n=3 samples per timepoint. Gene expression was normalized to Rpl32 and uninfected controls. F) RNA-Sequencing data obtained from flygutseq.buchonlab.com (Dutta et al., Cell Reports 2015). Spineless gene expression in different intestinal cell populations and induction 48h after P. entomophila infection is shown. G) Schematic of the targeting contstruct to generate ssGFP flies where GFP is inserted at the C-terminus of the spineless gene. H) ssGFP expression is visible in the antenna imaginal disk of L3 larvae from ssGFP flies. Images are from one experiment. Scale bars: 50µm. I) Representative fluorescent images of the midgut of w1118 and ssGFP flies 24h after P. entomophila infection. Scale bars: 50µm. J) GFP expression was analysed by flow cytometry in the midguts of naive w1118 and naive and P. entomophila infected ssGFP flies 24h after infection. A representative histogram and quantification of GFP + cells is shown. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. K) Schematic of spineless inactivation using ssGFP flies and membrane-anchored anti-GFP antibody. L) Representative images of aristapedia and leg phenotypes typical of ss mutant flies were seen in rn-Gal4, uas- anti-GFP, ssGFP flies. These flies also exhibited a pharate lethal phenotype. Data are from one experiment. M) Schematic of the transgene construct to generate spineless overexpressing flies. N) Gene expression was determined by qPCR in the midgut of naive flies incubated at 18°C or 29°C. Gene expression was normalized to Rpl32. Data are from one experiment with n=3 samples per genotype and temperature. O) Schematic of P. entomophila infection. P) The number of pHH3 + cells per midgut was quantified at 24h post P. entomophila infection. Data are from 3 independent experiments, n=5-10 per genotype and were analysed by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. Q, R) Survival following P. entomophila infection. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments, n=230-300 flies per genotype and compared using Log-Rank test of survival curves. P.e., Pseudomonas entomophila; RPKM, reads per kilobase per million; ISC, intestinal stem cells; EB, enteroblasts; EC, enterocytes; EE, enteroendocrine cells.

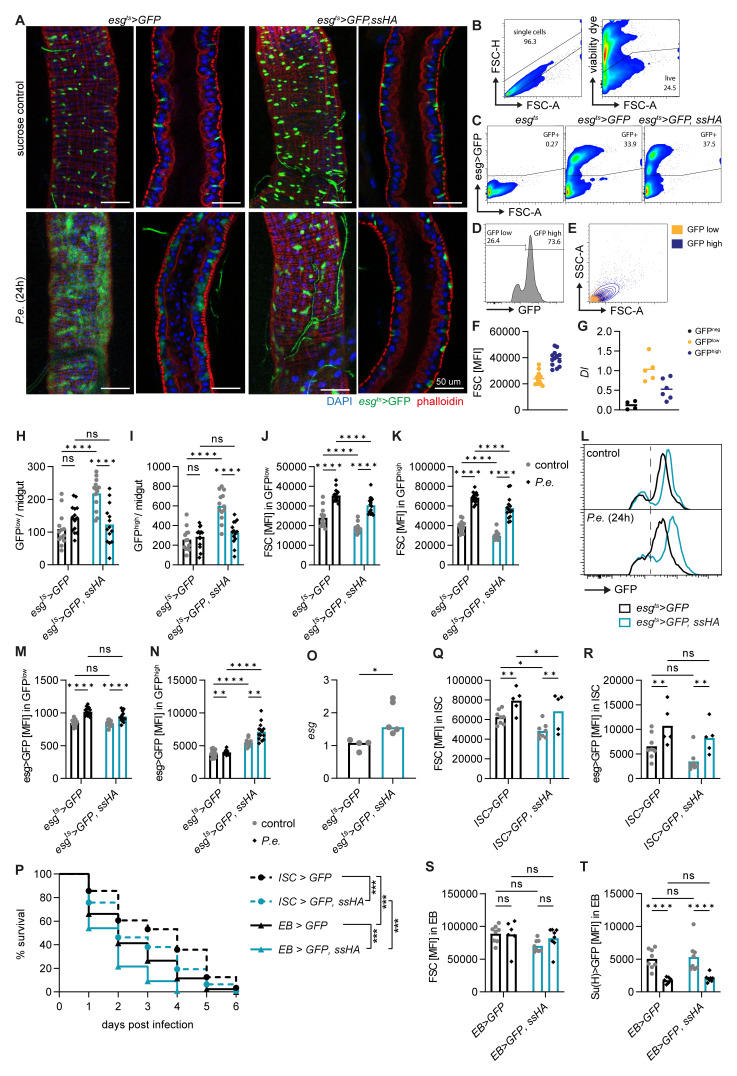

Figure 2. Spineless overexpression reduces survival through ISC- and EB-specific effects.

A) Representative images of P. entomophila infected midguts at 24h post infection. B- E) Gating strategy to analyse ISC and EB populations in the midgut of naïve flies by flow cytometry. Each sample is from n=2 pooled midguts. B) Exclusion of doublets and dead cells. C) GFP expression is shown for different genotypes. Cells were pre-gated on live, single cells as shown in B. D) GFP high and GFP low subsets amongst GFP + cells. E) Comparison of size and granularity of the GFP high and GFP low subsets. F) Quantification of forward scatter (FSC) as a measure of cell size in GFP high and GFP low cells. G) Delta ( Dl) expression in GFP neg, GFP low and GFP high subsets was determined by qPCR in FACS-sorted cells from naive esg ts>GFP flies and normalized to Rpl32. Data are pooled from two experiments, n=4–6 samples per cell type. H- N) Midguts from uninfected controls and at 24h post P. entomophila infection were analysed by flow cytometry. Each datapoint is from n=2 pooled midguts. H, I) Quantification of GFP low and GFP high cell numbers per midgut. J, K) Mean fluorescent intensity for FSC (cell size) in GFP low and GFP high populations. L) Representative flow cytometry plots depicting GFP fluorescent intensity in GFP + cells. M, N) Geometric mean fluorescent intensity of GFP in GFP low and GFP high populations. H- K, M, N) Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=13-14 samples per genotype. O) Escargot ( esg) expression was determined by qPCR in FACS sorted GFP high cells from naïve flies and gene expression was normalized to Rpl32. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments for n=4–5 samples per genotype and were analysed by t-test. P- T) P. entomophila infection in flies overexpressing spineless specifically in ISC ( esg-Gal4, Su(H)-Gal80, tub-Gal80 ts ) or in EB ( Su(H)-Gal4, tub-Gal80 ts ). P) Survival following P. entomophila infection. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=295–339 flies per genotype and were compared using Log-Rank test of survival curves with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Q, R) Fluorescent intensity of FSC and GFP in ISC populations from uninfected controls and at 24h post P. entomophila infection in esg-Gal4, Su(H)-Gal80, tub-Gal80 ts flies. Data are from one experiment with n=5–8 samples per genotype and for each sample 2 midguts were pooled. S, T) P. entomophila infection in flies overexpressing spineless specifically in EB ( Su(H)-Gal4, tub-Gal80 ts ). Fluorescent intensity of FSC and GFP in EB populations from uninfected controls and at 24h post P. entomophila infection. Data are from one experiment with n=5–8 samples per genotype and for each sample 2 midguts were pooled. H- K, M, N, Q- T) Data were analysed by 2way-ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. P.e., Pseudomonas entomophila.

Table 2. Summary of survival data from tumour experiments with P. entomophila infection.

| experiment # | genotype 1 | genotype 2 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| median survival

(days) |

n | median survival

(days) |

n | ||

| esg ts | esg ts>ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 21 | 120 | 19 | 120 | 0.4071 |

| 2 | 17 | 79 | 15 | 67 | 0.4222 |

| pooled ( Figure 3G) | 19 | 199 | 18 | 187 | 0.2361 |

| esg ts>N RNAi | esg ts>N RNAi, ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 9 | 122 | 19 | 120 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 8 | 74 | 10 | 112 | 0.0127 |

| pooled ( Figure 3G) | 8 | 196 | 18 | 232 | <0.0001 |

| ssGFP, esg ts | ssGFP, esg ts>anti-GFP | ||||

| 1 | 33 | 176 | 30 | 180 | 0.0224 |

| 2 | 3 | 77 | 11 | 85 | <0.0001 |

| pooled ( Figure 3D) | 17 | 253 | 23 | 265 | 0.2165 |

| ssGFP, esg ts> N RNAi | ssGFP, esg ts> N RNAi, anti-GFP | ||||

| 1 | 9 | 158 | 7 | 122 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 3 | 83 | 2.5 | 44 | 0.0599 |

| pooled ( Figure 3D) | 7 | 241 | 7 | 166 | 0.0001 |

Summary data including the number of flies (n), the median survival, and uncorrected p value of log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test are shown for each individual survival experiment and the pooled data.

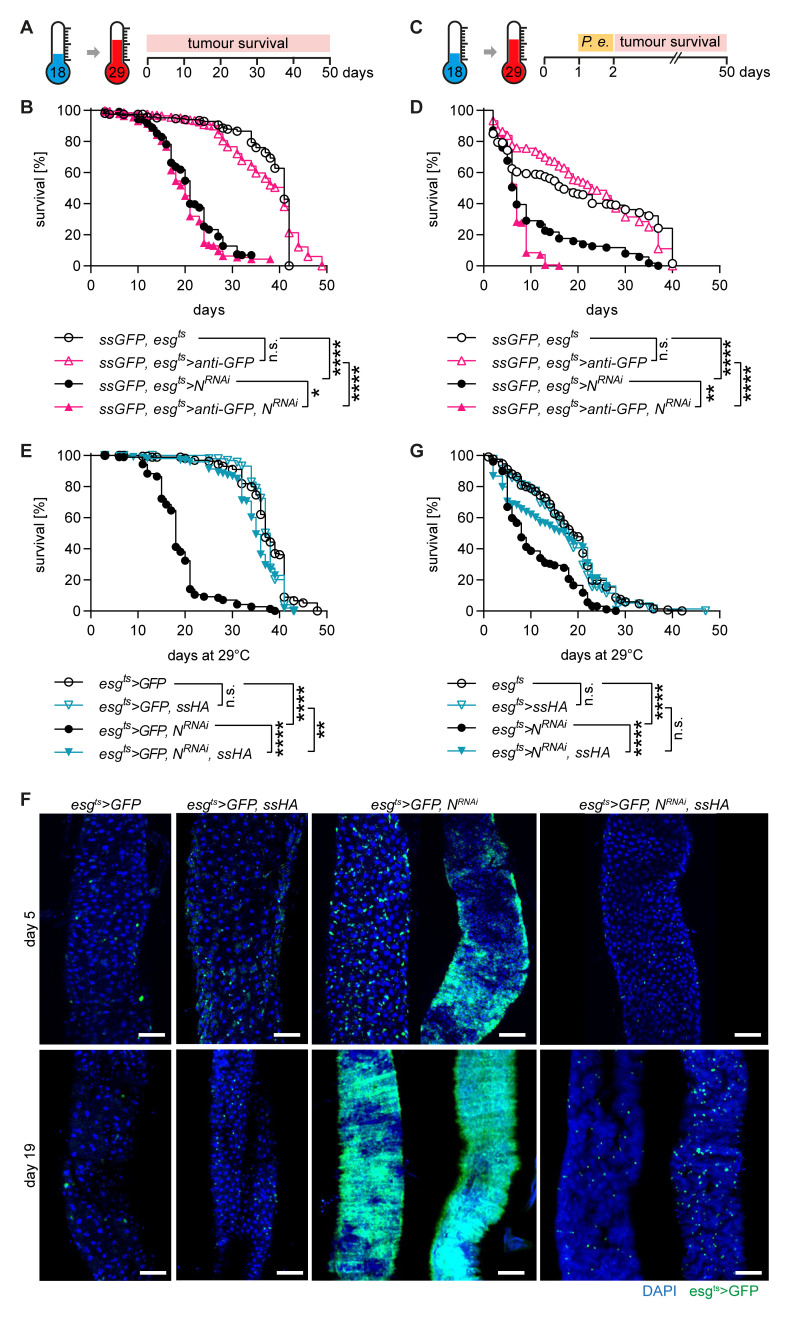

Figure 3. Spineless prevents tumour formation in the Notch RNAi tumour model.

A) Schematic of Notch RNAi tumour model. B) Survival of flies with spineless inactivation and controls in the Notch RNAi tumour model. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=189-297 flies per genotype. C) Schematic of Notch RNAi tumour model with 24h low-dose P. entomophila infection. D) Survival of flies with spineless inactivation and controls in the Notch RNAi tumour model with 24h low-dose P. entomophila infection. Data are from two experiments with n=166-265 flies per genotype. E) Survival of spineless overexpression and controls in the Notch RNAi tumour model. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=173-202 flies per genotype. F) Representative fluorescent images of controls and spineless overexpressing flies at different timepoints of the Notch RNAi tumour model. Scale bars: 50µm. G) Survival of spineless overexpression and controls in the Notch RNAi tumour model with 24h low-dose P. entomophila infection. Data are from two experiments with n=187-232 flies per genotype. B, D, E, G) Data were analysed using Log-Rank test of survival curves and Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Tumour survival experiments

Crosses were set up at 18°C to activate GAL80ts, thus restricting the expression of the Gal4-induced transgenes. Adult female offspring were selected at 0–4 days of age and shifted to 29°C to induce expression of transgenes. Every 2–3 days during incubation at 29°C, flies were transferred onto fresh food and survival was recorded. Survival data from individual experiments are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of survival data from tumour experiments.

| experiment # | genotype 1 | genotype 2 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| median survival

(days) |

n | median survival

(days) |

n | ||

| esg ts>GFP | esg ts>GFP, ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 90 | 0.0267 |

| 2 | 37 | 137 | 37 | 91 | 0.0561 |

| pooled ( Figure 3E) | 37 | 173 | 38 | 181 | 0.0446 |

| esg ts>GFP, N RNAi | esg ts>GFP, N RNAi, ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 21 | 33 | 35 | 40 | 0.0016 |

| 2 | 18 | 141 | 36 | 162 | <0.0001 |

| pooled ( Figure 3E) | 18 | 174 | 35 | 202 | <0.0001 |

| ssGFP, esg ts | ssGFP, esg ts>anti-GFP | ||||

| 1 | 39 | 58 | 35 | 121 | 0.3217 |

| 2 | >40 | 131 | >40 | 126 | 0.5531 |

| pooled ( Figure 3B) | 41 | 189 | 41 | 247 | 0.0156 |

| ssGFP, esg ts> N RNAi | ssGFP, esg ts> N RNAi, anti-GFP | ||||

| 1 | 18 | 109 | 18 | 98 | 0.249 |

| 2 | 21 | 188 | 21 | 141 | 0.0237 |

| pooled ( Figure 3B) | 21 | 297 | 20 | 239 | 0.0068 |

| esg ts | esg ts>ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 39 | 379 | 40 | 405 | 0.0721 |

| 2 | 32 | 223 | 37 | 127 | 0.2309 |

| pooled ( Figure 4B) | 37 | 602 | 39 | 532 | 0.0001 |

| esg ts> yki act | esg ts> yki act, ssHA | ||||

| 1 | 7 | 310 | 30 | 236 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 8 | 117 | 31 | 173 | <0.0001 |

| pooled ( Figure 4B) | 7 | 427 | 31 | 409 | <0.0001 |

Summary data including the number of flies (n), the median survival, and uncorrected p value of log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test are shown for each individual survival experiment and the pooled data.

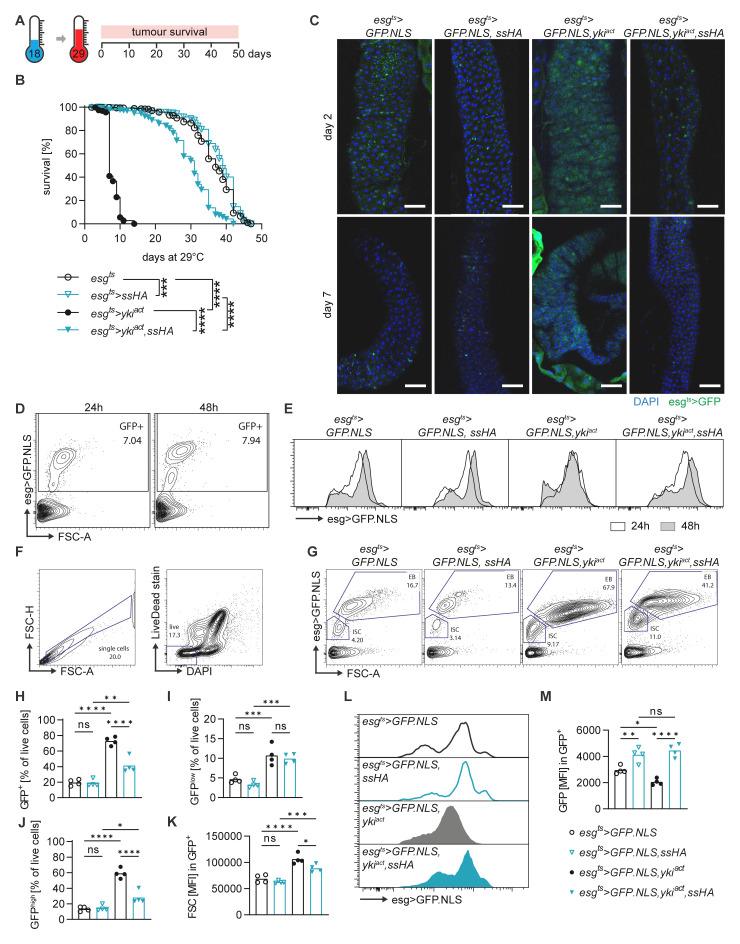

Figure 4. Spineless delays tumour formation in the yki act tumour model.

A) Schematic of yki act tumour model. B) Survival of spineless overexpression and controls in the yki act tumour model. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=409-592 flies per genotype and compared using Log-Rank test of survival curves with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. C) Representative fluorescent images of controls and spineless overexpressing flies at different timepoints after induction of the yki act tumour model. Scale bars: 50µm. D, E) Comparison of GFP expression at 24h and 48h after temperature shift from 18°C to 29°C. Cells were pre-gated on live, single cells. Data are from one experiment with n=3-5 samples per genotype and each sample is pooled from 2 midguts. D) FSC and GFP fluorescence in esg ts>GFP.NLS flies. E) Comparison of GFP intensity across different genotypes. F- M) Flow cytometric analysis of midguts from day 2 of tumour induction at 29°C. Data are from n=4 samples (each sample is pooled from 24-30 midguts) and were analysed by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. F, G) Representative flow cytometry plots of the gating of live, single cells ( F) and GFP expressing cells as a percentage of live, single cells ( G). H- K) Quantification of GFP + cells, GFP low and GFP high populations and cell size of GFP + cells. L) Representative flow cytometry plots of GFP intensity within GFP + cells. M) Quantification of GFP fluorescent intensity within GFP + cells.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9, www.graphpad.com; open access alternative: R Studio www.r-project.org). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted and analysed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. The p values of multiple comparisons of survival curves were adjusted using the Bonferroni method. Pooled survival data from 2–3 independent experiments is shown. The data from the individual experiments are shown in Table 1– Table 3. 2-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons was used to analyse grouped comparisons. All data points and ‘‘n’’ values reflect biological replicates (either from single or from pooled flies). P values are indicated by asterisk: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0,001, **** p<0.0001.

Immunofluorescence staining and microscopy

Drosophila midguts were dissected and fixed with 4% (w/v) Formaldehyde (Thermofisher, 28906) in PBS (ThermoFisher, 14190169) at room temperature for 30 minutes, permeabilised with PBS 0.2% Triton x-100 (Thermofisher, 85112) (PBST) at room temperature for 30 minutes and blocked with 10% (w/v) Bovine Serum Albumin (SigmaAldrich, A9647) in PBST (PBSA) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Primary antibody rabbit anti-Phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) (Cell signalling, 9701) was diluted 1:1000 in PBSA and added at 4°C overnight. Stained tissue was washed with PBS the next day and stained with secondary antibodies donkey anti-rabbit A555 (LifeTech, A21429) 1:1000 diluted in PBSA at room temperature for 3 hours followed by 1:10000 PBS-diluted DAPI staining (5mg/mL in H 2O, SigmaAldrich, D9542) for 10 minutes before PBS washing. Ovaries and posterior abdomen were removed, and the remaining midguts were then mounted with antifade (Thermofisher, P36934) on 21-well glass slides (1 gut/well). Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope and were further processed in ImageJ (FIJI, version 2.1.0, https://imagej.net/). Proliferating cells were manually counted under Zeiss AxioImager M1 epifluorescence microscope using 20x objective. pHH3 + cells were counted from 3–5 whole female midguts per experiment. Images within stacks were collected at 3-5µm z-interval, 5–7 images per stack were taken to cover the complete depth of samples acquired from R2 of the midugt 30 .

Flow cytometry

The cell isolation protocol was adapted from Dutta et al. 31 . 96-well v-bottom plate was prepared with 40µL/well of digestion buffer on ice (30µL PBS, 10µL of 4mg/mL Elastase (Sigma, E0258), 0.4µL of 5mg/mL DNase I (Fisher Scientific, 10104159001). Unless otherwise stated, each sample is pooled from 2 midguts. 2 midguts/well were digested at 27°C with shaking for 1h, followed by pipetting 20 times for mechanical separation. Cells were washed in wash buffer (PBS, 2mM EDTA (Thermo Fisher, 15575020), 0.2% BSA), centrifuged and incubated with Live/Dead nIR stain (Thermofisher, L10119) at 4°C for 30 minutes, washed in PBS and fixed with 4% PFA at room temperature for 30 minutes. Samples were washed in PBS, resuspended in wash buffer with count bright beads (Invitrogen, C36950) to determine absolute cell numbers per midgut and filtered through 40µm filters. Samples were acquired on a BD Fortessa instrument (BD Biosciences) and analysed using FlowJo v10 (TreeStar, www.flowjo.com; open access alternative: https://floreada.io). Samples were gated on single cells using FSC-A/FSC-H and SSC-A/SSC-H and to exclude debris on FSC-A/SSC-A. Dead cells were excluded based on Live/Dead near-IR staining and autofluorescence (405nm laser, 450/50 filter) before gating on GFP + cells.

Cell sorting

Midguts were dissected and digested as described above for flow cytometry. 10–30 midguts per sample were digested in 100–300µl digestion buffer. Live cells were sorted through a 70µm nozzle on a BD Fusion instrument (BD Biosciences). Cells were gated as is shown in Figure 4G.

RNA isolation and qPCR

Entire midguts (2 midguts per sample) or sorted cells (2000–20,000) were vortexed in TriReagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, 15596018) and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturers protocol, using Glycogen (Thermo Fisher, R0551) to precipitate the RNA pellet. RNA was reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher, 4368814). The cDNA served as a template for the amplification of genes of interest and housekeeping genes by real-time quantitative PCR, using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, 4351372), universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, 4318517) and the QuantStudio 7 System (Applied Biosystems). The following primer/probes were used: Ribosomal protein L32 (Dm02151827_g1), spineless (Dm02134622_m1), tango (Dm02373281_s1), DptB (Dm01821557_g1), unpaired 3 (Dm01844142_g1), Dual oxidase (Dm01800981_g1), NADPH oxidase (Dm01826191_g1), Delta (Dm02134951_m1), escargot (Dm01841264_s1). mRNA expression was determined using the ΔC T method by normalizing to Rpl32 gene expression. To determine expression of spineless isoforms, genes were amplified using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher, 4368702). Two sets of primers were used for the ss-A isoform: forward 1 (GCGAGGAGTTGGTTCCAATG), reverse 1 (ACTGCGAGTACTGCGTGTAG), 242bp product and forward 2 (GCGAGGAGTTGGTTCCAATG), reverse 2 (CGGATGCGGATGATGGTACG), 268bp prodcut. For isoform ss-C/D the following primers were used: forward 1 (GCGAGGAGTTGGTTCCAATG), reverse 1 (CTGCTGAAGCCGATCCATTC), 395bp product and forward 2 (GCGAGGAGTTGGTTCCAATG), reverse 2 (CAAATCACCAGAGGAGCGGA), 456bp product. The primers for isoform ss-C/D also generate products of 686bp and 747bp, respectively for ss-A.

RNA sequencing and data analysis

ISC and EB populations were sorted by FACS as described above. DAPI was used as an additional staining to exclude dead cells. Cells were gated as shown in Figure 4G. RNA from 5,000–30,000 cells was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen, 74004) and eluted in 15µl water. RNA quality and concentration was analysed on a Bioanalyzer and only samples with RIN>7 were used for sequencing. NEBNext Low Input RNA libraries were prepared manually following the manufacturer’s protocol (NEBNext® Single Cell/Low Input RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® Instruction Manual Version 5.0_5/20, NEB #E6420L). Samples were normalized to 1ng total RNA material per library in 8μl of nuclease-free water. RNA samples underwent reverse transcription, and the resulting cDNA was amplified by 10 cycles of PCR (according to the manufacturer recommendation for 1 ng input DNA). Amplified cDNA was subjected to two consecutive bead clean-ups with a 0.6X and 0.9X ratio of SPRISelect beads [B23318; Beckman Coulter] to sample volume. cDNA was fragmented enzymatically to target an insert size of ~200bp. Adaptors (diluted to 0.6µM) were ligated to the cDNA fragments and adaptor-ligated samples were cleaned up with SPRISelect beads (ratio: 0.8x). For the amplification of the sequencing library, 25µl of Q5 Master Mix was added, plus 10µl of a unique index (NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina [NEB #E6609]). Libraries were amplified by 8 PCR cycles. Final libraries were cleaned up with SPRISelect beads (ratio: 0.9x). The quality of the purified libraries was assessed using an Agilent D1000 ScreenTape Kit on an Agilent 4200 TapeStation. Libraries were sequenced to a depth of at least 25M reads on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 run in 101-8-8-101 configuration.

Sequencing runs were concatenated into single gzipped fastq files. These were then aligned to genome BDGP6 using nf-core/rnaseq 3.1 32 . The resulting counts file salmon.merged.gene_counts.tsv was used to create a SummarizedExperiment ( https://bioconductor.org/packages/SummarizedExperiment) which was then analysed using DESeq2 33 to produce tables of differentially expressed genes and rnk files for Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). PCA plots were made using the DESeq2 function varianceStabilizingTransformation. R computations were carried out using R version 4.2.3 (2023-03-15), "Shortstop Beagle". Hierarchical clustering of genes was conducted with Morpheus (Broad Institute), using one minus pearson correlation with average linkage method. GSEA was conducted using GSEA 4.2.2 (Broad Institute) with standard settings. The gene sets were taken from gsean ( https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/gsean.html) using the GO_dme data set and these were translated into Ensembl gene ids using the biomaRt package 34 . Leading edge analysis was used to remove overlapping pathways and to identify the underlying genes. We used published marker genes for ISC and EB 35 (obtained from supplemental table 6 of reference 35) as gene sets for comparison with our GFPhigh versus GFP low cells.

We used the Homologous Gene Database ( https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/hgd/) to obtain a list of homologous proteins between Drosophila and mouse. This list was then filtered on genes regulated by AHR and Spineless. Fly genes with differential expression between ssHA and controls with |FC|>2 in either GFP low or GFP high cells were retained. For mouse genes, we used previously published RNA sequencing date from wildtype and AHR knockout intestinal organoids (GSE133092) 5 . Mouse genes with differential expression between AHR knockout and controls with |FC|>2 in either stem cell or differentiated conditions were retained. This yielded a list of 213 mouse genes and 260 homologous fly genes that are regulated by AHR and Spineless. Gene ontology of mouse genes was analysed using DAVID ( https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) and selected pathways are shown.

Results

Spineless limits intestinal stem cell proliferation after Pseudomonas entomophila infection

Given the critical functions of AHR in the mammalian intestine, we sought to determine if Spineless has similar evolutionarily conserved roles in the Drosophila midgut. We infected flies with the enteropathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas entomophila as a model of intestinal damage and regeneration. Bacterial infection induced expression of antimicrobial defence genes DiptB, Nuox, Upd3 ( Figure 1A–C). Spineless was expressed at low levels in the steady state intestine and was induced over 200-fold 24h following bacterial infection ( Figure 1D). Expression of the Spineless binding protein tango ( tgo) remained largely unchanged after infection ( Figure 1E). We analysed published RNA-sequencing data of different intestinal cell populations from Dutta and colleagues 36 which confirmed low expression of spineless in the steady-state midgut and strong induction after P. entomophila infection ( Figure 1F). Of note, spineless was only induced in intestinal stem cells (ISC) and enteroblasts (EB), but not in enterocytes or enteroendocrine cells. This suggests a potential role for Spineless in the progenitor compartment following bacterial infection.

We generated new lines to conditionally inactivate or overexpress Spineless to study its function in midgut progenitors. ssGFP flies were created by targeted insertion of GFP at the C-terminus of the endogenous spineless locus ( Figure 1G). Homozygous ssGFP flies showed no apparent phenotype and ssGFP was clearly visible in the antenna imaginal disk ( Figure 1H). In the midgut, we could not detect a clear GFP signal in naïve or P. entomophila infected ssGFP flies ( Figure 1I, J). Flies expressing a membrane-anchored anti-GFP nanobody ( UAS-anti-GFP) were created to prevent ssGFP from translocating to the nucleus and thereby render it inactive ( Figure 1K). To achieve cell type-specific Spineless inactivation, we utilized the GAL4/UAS system. GAL4 can be expressed under a cell type-specific promoter to induce expression of transgenes with a GAL4 binding site (UAS). We used the promoter of rotund, which is expressed in the imaginal disk, to induce anti-GFP. ssGFP, rotund>anti-GFP flies showed aristapedia and leg phenotypes typical of Spineless mutants ( Figure 1L) 7, 8 , confirming that this approach can block Spineless function.

We made use of the escargot ( esg)- Gal4 driver and the temperature sensitive repressor tubGal80 t s to manipulate Spineless expression in ISC and EB of the adult midgut only. To inactivate Spineless in adult midgut ISC and EB, we generated ssGFP, esg ts>anti-GFP flies. To overexpress Spineless, UAS-ss flies with a C-terminal 3xHA tag were generated ( Figure 1M). At the permissive temperature of 29°C, spineless expression in the midgut was increased about 10,000-fold in esg ts>ssHA flies compared to controls ( Figure 1N). Flies were reared at 18°C and switched to 29°C 5 days prior to infection ( Figure 1O). Infection with P. entomophila induces epithelial damage followed by a wave of ISC proliferation that leads to epithelial regeneration 37– 40 . ISC proliferation was induced in controls following P. entomophila infection. Spineless inactivation further increased ISC proliferation while Spineless overexpression abolished the ISC proliferative response ( Figure 1P). These findings are similar to the role of AHR in promoting intestinal stem cells in the mammalian intestine 5, 41, 42 . We hypothesized that this could reduce the ability of Spineless overexpressing flies to survive infection. While inactivation of Spineless did not affect survival following infection with P. entomophila ( Figure 1Q), overexpression of Spineless accelerated death following infection ( Figure 1R). This suggests that overexpression of Spineless limits ISC proliferation after P. entomophila infection, which may impair epithelial regeneration and could thereby lead to reduced survival.

Spineless overexpression reduces survival through ISC- and EB-specific effects

In the midgut, esg>GFP labels ISC and EB and therefore allows quantification of these cells as well as measurement of cell size and GFP intensity. In naïve flies, Spineless overexpression increased esg>GFP positive cells on fluorescent images of the midgut compared to wildtype flies ( Figure 2A), suggesting that it affects intestinal progenitor dynamics. In wildtype flies, P. entomophila infection resulted in a noticeable increase in the number of esg>GFP positive cells and an increase in their cell size. Spineless overexpression blocked the increase in cell number and size after P. entomophila infection, in line with the lack of increased ISC proliferation measured by pHH3 + cell quantification (as seen in Figure 1P).

We then used flow cytometry to quantify the intestinal cell populations. Esg>GFP positive cells are readily detectable by flow cytometry after gating on live, single cells ( Figure 2B, C). Within the GFP + cells, two populations are visible, smaller GFP low cells and larger GFP high cells ( Figure 2D-F). This difference in GFP fluorescent intensity and cell size has previously been used to distinguish ISC from EB 43 . We found indeed higher Delta expression in GFP low than GFP high populations by qPCR from FACS sorted cells, suggesting that these may be ISC and EB, respectively ( Figure 2G). We used this gating strategy to gain further insights into GFP low (ISC) and GFP high (EB) cells. This approach corroborated that Spineless overexpression increased the number of GFP + cells at steady state and led to a decrease in the number of GFP low and GFP high cells in infected versus naïve Spineless overexpressing flies ( Figure 2H, I). We note a large variability in the normalized cell numbers, which may result from differential susceptibility to cell death of large or fused cells during midgut processing. Flow cytometric analysis further confirmed an increase in cell size in wildtype flies after P. entomophila infection and a reduction in cell size in naïve or infected flies overexpressing Spineless compared to wildtype flies ( Figure 2J, K).

Within the GFP low and GFP high cells, esg>GFP fluorescence increased after infection in wildtype controls ( Figure 2L–N). Escargot was shown to maintain stemness in ISC and EB 44, 45 . In EB, Escargot also enhances Notch signalling by inhibiting Amun which may promote differentiation 44 . Spineless overexpression did not affect GFP fluorescent intensity driven by esg>GFP in GFP low cells ( Figure 2M), but increased fluorescence intensity in both naïve and infected GFP high cells ( Figure 2N). We confirmed that escargot gene expression was increased by qPCR in FACS-sorted GFP high cells from naïve flies ( Figure 2O). This suggests that Spineless may directly affect escargot expression in EB.

We next sought to determine whether Spineless overexpression in ISC or EB was responsible for the reduced survival following P. entomophila infection. Overexpression of Spineless using cell type-specific drivers for either ISC or EB reduced survival after infection in both cases ( Figure 2P). Spineless overexpression in ISC reduced ISC cell size but had no significant effect on esg>GFP fluorescent intensity ( Figure 2Q, R), in line with the results observed with the esg ts driver. Spineless overexpression in EB did not affect EB cell size or Su(H)>GFP expression ( Figure 2S, T). Taken together, these results suggest that Spineless reduces survival following bacterial infection by limiting ISC proliferation and possibly by altering EB maturation through escargot.

Spineless prevents intestinal tumour formation in the Notch RNAi tumour model

Limiting the proliferation of ISC is detrimental in the context of infection-induced damage and regeneration but could be beneficial in the context of tumours. We therefore hypothesized that Spineless may prevent tumour formation in the midgut. Loss of Notch signalling (through Notch RNAi) results in the proliferation of neoplastic ISC-like cells that fail to differentiate and form multi-layered tumours 23– 34, 36– 46 . To determine the role of spineless in this tumour model, we generated ssGFP, esg ts>anti-GFP, N RNAi flies to inactivate spineless and Notch signalling as well as esg ts>N RNAi, ssHA flies to overexpress spineless while reducing Notch expression. Spineless inactivation only had a very minor effect on survival in the Notch RNAi tumour model, reducing median survival from 21 to 20 days ( Figure 3A, B). Tumour growth induced by Notch RNAi can be accelerated by infecting flies with P. entomophila, which induces a wave of stem cell proliferation 46, 47 . We therefore infected flies with a low dose of P. entomophila for 24h and then followed their survival. Indeed, bacterial infection reduced the median survival of tumour flies from 21 to 7 days ( Figure 3B-D). Flies with Spineless inactivation succumbed even faster to tumours, with a maximum survival of only 16 days compared to 37 days for control tumour flies after P. entomophila infection ( Figure 3D).

Spineless overexpression completely blocked the development of tumours ( Figure 3E, F). The median survival was increased from 18 days to 35 days by overexpressing Spineless in the Notch RNAi tumour model, which nearly matched the median survival of control flies (38 days). In the Notch RNAi model increased numbers of esg ts>GFP positive cells or clonal tumours could already be seen by day 5 ( Figure 3F). By day 19, the esg ts>GFP positive tumours took over most of the midgut in surviving flies. Spineless overexpressing flies showed no signs of tumour development at day 5 and at most a slight increase in the number of esg ts>GFP positive cells by day 19. Spineless overexpression also increased survival when the Notch RNAi tumour model was combined with low-dose P. entomophila infection ( Figure 3G). Thus, Spineless can block tumour development in the Drosophila midgut, likely by inhibiting ISC proliferation.

Spineless delays tumour formation in the yki act tumour model

We used a second tumour model to confirm the effect of Spineless. The transcriptional coactivator yorkie can regulate ISC proliferation during midgut epithelial regeneration 40, 48– 50 . Mutation of 3 serine phosphorylation sites to alanine leads to a constitutively active form of yorkie ( yki act) that is no longer subject to control by the Hippo pathway and leads to the formation of intestinal tumours 27, 51 . We generated esg ts>yki act ,ssHA flies to overexpress Spineless in this tumour model. Spineless overexpression increased median survival from 7 days in esg ts>yki act flies to 31 days, while control flies without yki act had a median survival of 37–39 days ( Figure 4A, B). This suggests that in this tumour model Spineless overexpression can also significantly delay tumour onset. The expansion of tumour cells in esg ts>yki act flies was already visible after 2 days by microscopy but not visible in spineless overexpressing flies even by day 7 ( Figure 4C).

Next, we sought to use flow cytometry to profile the GFP + cells in the midgut at an early timepoint of yki act tumour development. GFP + cells were already visible 24h after temperature shift, but the distinction between GFP low and GFP high cells was more apparent and the GFP intensity was higher after 48h ( Figure 4D, E). We therefore chose the 48h timepoint. The expansion of tumour cells with GFP high fluorescence and large cell size was clearly visible at this time ( Figure 4F, G). The frequency of GFP + cells increased more than 3-fold in esg ts>yki act flies and was suppressed by spineless overexpression, although not to baseline levels ( Figure 4H). To quantify the frequency of GFP low and GFP high cells within GFP + cells ( Figure 4I, J), the gates had to be adjusted for each genotype to fit the populations ( Figure 4G). In this analysis Spineless overexpression suppressed the GFP high population in yki act tumours. Tumour cells showed an increased size (FSC) compared to GFP + cells from tumour-free flies, which was partially rescued by spineless overexpression ( Figure 4K) and decreased intensity of GFP expression which was fully rescued by spineless overexpression ( Figure 4L, M). Together, these findings demonstrate that Spineless can strongly suppress or delay tumour formation in two independent models.

Spineless affects cell metabolism, proliferation, and differentiation pathways

To understand how Spineless blocks the development of tumours, we sorted GFP low cells (likely ISC) and GFP high cells (likely EB) populations from flies with or without yki act tumours and with or without spineless overexpression to analyse their transcriptome. We chose 48h post temperature shift to analyse the transition from normal to tumour cells and to be able to distinguish and isolate the GFP low and GFP high cells populations by FACS. Given the differences in size and GFP intensity between the genotypes, the gates were adjusted for each genotype to best fit the populations ( Figure 4G). Principle component analysis indicated distinct clustering of GFP low and GFP high populations (mostly along PC2) as well as genotypes (mostly along PC1) ( Figure 5A). Samples from Spineless overexpressing flies grouped away from controls in the opposite direction of yki act tumour cells and yki act,ssHA cells clustered closer to controls than to yki act tumour cells. This was also apparent in the number and overlap of differentially expressed genes across different comparisons in both the GFP low and GFP high cells ( Figure 5B, C) and broadly reflects the ability of Spineless to suppress tumour growth as seen in the survival experiments. Importantly, yki act and ssHA expression were not reduced when expressed together as compared to flies that only overexpressed yki act or ssHA alone ( Figure 5D, E), confirming that the inhibition of tumour growth in yki act,ssHA flies is not merely the result of reduced yki act expression.

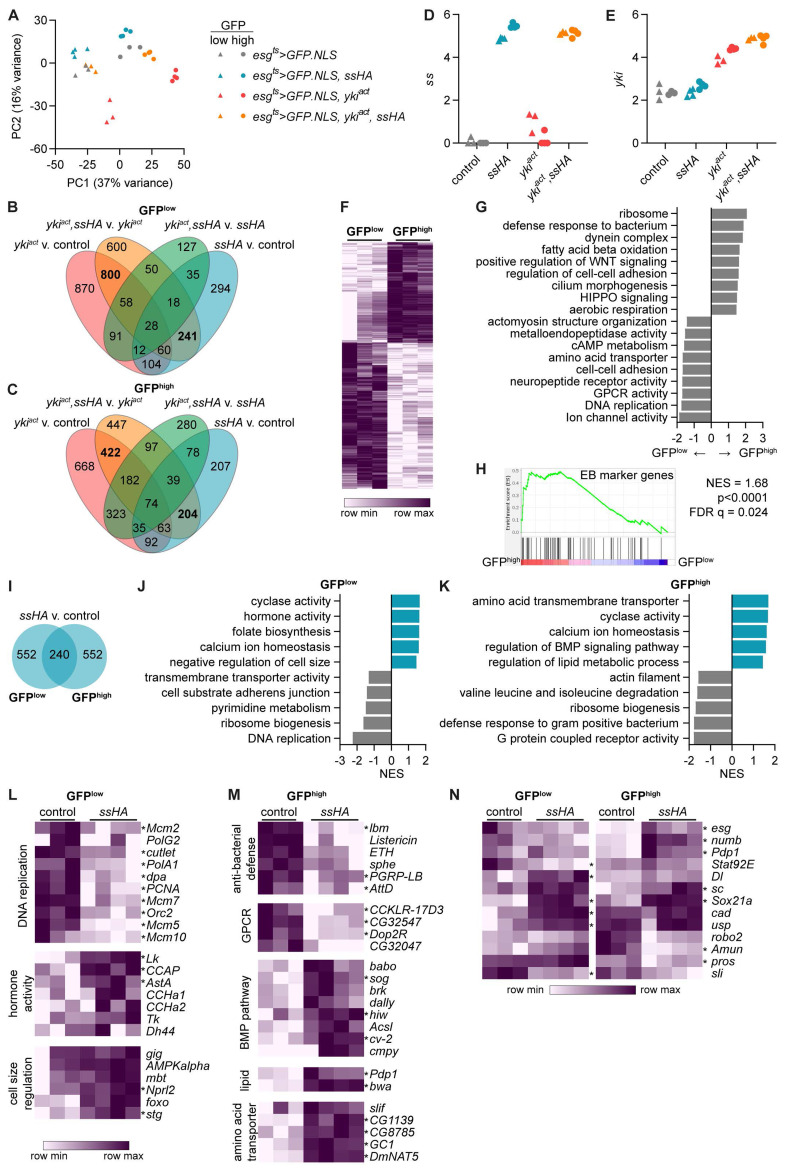

Figure 5. Spineless alters cell metabolism, proliferation and differentiation in midgut progenitors.

Bulk RNA sequencing was conducted on sorted GFP low and GFP high cell populations 48h after temperature shift from 18°C to 29°C in the indicated genotypes. A) Principle component analysis of sequenced GFP low and GFP high samples. B, C) Overlap of differentially expressed genes (adjusted p value <0.05, |FC|>2). 3388 unique genes were differentially expressed between the different genotypes across all ISC samples ( B) and 3211 unique genes across all EB samples ( C). D, E) Expression of ss and yki in sequenced samples is depicted in log 10 (raw counts +1). F) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes between GFP low and GFP high populations in control flies ( esg ts>GFP.NLS). Shown are 484 genes upregulated and 702 genes downregulated in GFP high vs. GFP low cells with p adj<0.05 and |log 2(FC)|>1. G) Gene set enrichment analysis comparing GFP high vs. GFP low cells from esg ts>GFP.NLS flies. Selected pathways with p<0.05 are shown. H) Gene set enrichment analysis comparing GFP high vs. GFP low cells from esg ts>GFP.NLS flies against known marker genes of EB (reference 35) showing positive enrichment of EB marker genes in GFPhigh cells. I) Number of differentially expressed genes between esg ts>GFP.NLS,ssHA and esg ts>GFP.NLS samples (padj<0.05, |FC|>2). I, J) Gene set enrichment analysis comparing J) GFP low and K) GFP high cells from esg ts>GFP.NLS,ssHA to esg ts>GFP.NLS samples. Selected pathways with p<0.05 are shown. L), M) Examples of genes from the leading edge of enriched pathways shown in J) and K). N) Key genes involved in midgut stem cell maintenance and differentiation. L- N) Genes with significant differential expression (p adj<0.05, |FC|>2) are denoted by *.

Within control esg ts>GFP.NLS flies we observed substantial changes between the two sorted populations. 702 genes were upregulated and 484 genes downregulated in sorted GFP high versus GFP low cells ( Figure 5F, Table 4). GFP low cells were enriched for genes relating to Ion channel activity, DNA replication, and GPCR activity ( Figure 5G). GFP high cells were enriched for genes relating to ribosomes, defense response against bacteria, and metabolic pathways including fatty acid beta oxidation and aerobic respiration. They also showed increased expression of genes relating to WNT and HIPPO signaling as well as cilium morphogenesis, suggesting differentiation towards mature epithelial cells. We also compared our data to published single cell RNA sequencing data from Hung et al. 35 , and found significant enrichment of their EB markers in GFPhigh versus GFP low cells ( Figure 5H). Their ISC marker genes were not significantly enriched in our dataset.

Table 4. Top 50 up- or down-regulated genes between GFP high and GFP low cells in esg ts>GFP.NL S flies.

| upregulated | downregulated | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | GFP

high vs. GFP

low

[log 2 (fold change)] |

Gene ID | GFP

high vs. GFP

low

[log 2 (fold change)] |

| FBgn0266489 | 11.34 | FBgn0051354 | -9.26 |

| FBgn0260464 | 10.86 | FBgn0020299 | -8.93 |

| FBgn0261360 | 9.61 | FBgn0039380 | -8.88 |

| FBgn0050151 | 7.67 | FBgn0016975 | -8.87 |

| FBgn0085342 | 7.04 | FBgn0028517 | -8.39 |

| FBgn0031032 | 6.55 | FBgn0000406 | -8.22 |

| FBgn0029810 | 6.46 | FBgn0085380 | -7.56 |

| FBgn0264605 | 6.45 | FBgn0266677 | -7.54 |

| FBgn0085291 | 6.43 | FBgn0040968 | -7.48 |

| FBgn0036953 | 6.33 | FBgn0032602 | -7.24 |

| FBgn0266645 | 6.29 | FBgn0041706 | -7.16 |

| FBgn0029970 | 6.14 | FBgn0036323 | -7.12 |

| FBgn0039523 | 6.03 | FBgn0042696 | -7.11 |

| FBgn0062412 | 5.88 | FBgn0036834 | -7.07 |

| FBgn0035300 | 5.77 | FBgn0031850 | -6.89 |

| FBgn0030607 | 5.74 | FBgn0004516 | -6.85 |

| FBgn0050090 | 5.57 | FBgn0054045 | -6.76 |

| FBgn0031514 | 5.51 | FBgn0034275 | -6.76 |

| FBgn0003129 | 5.18 | FBgn0050440 | -6.72 |

| FBgn0266742 | 5.05 | FBgn0036553 | -6.68 |

| FBgn0051454 | 4.98 | FBgn0028527 | -6.66 |

| FBgn0052536 | 4.72 | FBgn0040507 | -6.64 |

| FBgn0031098 | 4.61 | FBgn0263761 | -6.62 |

| FBgn0001208 | 4.56 | FBgn0039827 | -6.54 |

| FBgn0042627 | 4.47 | FBgn0035086 | -6.51 |

| FBgn0035317 | 4.29 | FBgn0026403 | -6.50 |

| FBgn0028955 | 4.23 | FBgn0250871 | -6.45 |

| FBgn0266935 | 4.17 | FBgn0034943 | -6.44 |

| FBgn0033065 | 3.94 | FBgn0028863 | -6.42 |

| FBgn0031630 | 3.86 | FBgn0039478 | -6.37 |

| FBgn0015288 | 3.84 | FBgn0034935 | -6.35 |

| FBgn0030945 | 3.81 | FBgn0030634 | -6.33 |

| FBgn0040609 | 3.78 | FBgn0002573 | -6.29 |

| FBgn0039385 | 3.70 | FBgn0035695 | -6.23 |

| FBgn0038832 | 3.68 | FBgn0027589 | -6.23 |

| FBgn0010774 | 3.67 | FBgn0031811 | -6.17 |

| FBgn0003002 | 3.64 | FBgn0036467 | -6.00 |

| FBgn0261801 | 3.62 | FBgn0003308 | -6.00 |

| FBgn0031021 | 3.53 | FBgn0039201 | -5.98 |

| FBgn0263652 | 3.51 | FBgn0039681 | -5.96 |

| FBgn0021776 | 3.51 | FBgn0086913 | -5.96 |

| FBgn0013323 | 3.43 | FBgn0039719 | -5.96 |

| FBgn0033447 | 3.39 | FBgn0004429 | -5.94 |

| FBgn0263046 | 3.37 | FBgn0053777 | -5.93 |

| FBgn0266624 | 3.35 | FBgn0030261 | -5.93 |

| FBgn0264503 | 3.33 | FBgn0033130 | -5.89 |

| FBgn0003261 | 3.33 | FBgn0039038 | -5.88 |

| FBgn0032782 | 3.17 | FBgn0261673 | -5.88 |

| FBgn0034013 | 3.09 | FBgn0031930 | -5.86 |

| FBgn0033446 | 3.09 | FBgn0036715 | -5.85 |

We next focused our attention on the gene expression changes driven by overexpression of Spineless. 792 genes were differentially expressed between Spineless overexpression and control samples in both the GFP low and GFP high populations, with 240 genes in common ( Figure 5I). As expected, spineless was highly overexpressed in both cell types ( Figure 5D). Using gene set enrichment analysis, we found that Spineless reduced expression of genes relating to DNA replication in GFP low cells ( Figure 5J), which correlates well with our earlier findings that Spineless suppressed cell proliferation after P. entomophila infection ( Figure 1). Pathways relating to DNA replication were only enriched in GFP low cells, but not GFP high cells which is in line with EB not proliferating ( Figure 5J, K). In GFP low cells, Spineless increased expression of genes relating to hormone activity, including several hormones secreted by enteroendocrine cells ( AstA, Tk, CCha1, CCha2) 52 ( Figure 5L). This suggests that Spineless overexpression may result in an increase in esg>GFP + enteroendocrine cells, a population that has previously been reported 53 . Spineless overexpression also increased expression of genes relating to negative regulation of cell size, such as Nprl2, foxo and stg ( Figure 5J, L). This is in line with our earlier findings that GFP low cells from Spineless overexpressing flies were smaller on flow cytometry ( Figure 2J) and ISC-specific overexpression of Spineless reduced their cell size ( Figure 2Q). Spineless overexpression increased expression of genes relating to calcium ion homeostasis and cyclase activity and reduced expression of genes relating to ribosome biogenesis in both GFP low and GFP high cells ( Figure 5J, K).

In GFP high cells, Spineless overexpression reduced expression of anti-bacterial defence genes, GPCR activity and actin filament ( Figure 5K, M). Genes relating to lipid metabolism, amino acid transporters and the BMP pathway were increased. The BMP signalling pathway has been shown to antagonize the response to injury and return ISC to a quiescent state after injury-induced proliferation 54– 56 . Inhibition of the BMP pathway by Spineless may contribute to the reduced stem cell proliferation in response to infection we observed earlier.

In addition to annotated GO pathways, we also sought to directly analyse the expression of genes with known critical roles in the midgut ( Figure 5N). Stat92E is a key transcription factor downstream of JAK-STAT signalling. It is normally increased during midgut regeneration after injury to promote stem cell proliferation 57 . Spineless overexpressing GFP low cells showed decreased expression of Stat92E, which may in part explain their reduced proliferative capacity. The mammalian genes Cdx2 and Rxra are directly regulated by AHR in the intestinal epithelium of mice 5 . Spineless increased the expression of their homologs caudal ( cad) and ultraspiracle ( usp) in GFP low cells. The sequencing data confirmed increased esg expression in GFP high but not GFP low cells from Spineless overexpressing flies, in line with our earlier flow cytometry and qPCR data ( Figure 2M–O). Esg has been reported to maintain stemness in ISC and EB 44, 45 . In EB, Escargot also enhances Notch signalling by inhibiting Amun which may promote differentiation. Increased expression of the Notch ligand Delta ( Dl) in GFP low cells and the transcription factor Sox21a in GFP low and GFP high cells could promote increased differentiation of EB to enterocytes 22, 58– 60 and the enteroendocrine marker pros was decreased in GFP high cells. However, many of the differentially expressed genes promote differentiation into enteroendocrine cells. Scute (sc) overexpression in ISC and EB leads to an increase in Pros + enteroendocrine cells 61 , numb facilitates enteroendocrine cell fate specification by limiting Notch signalling 62 , and Pdp1 is a transcription factor in enteroendocrine cells with binding sites in the promoters of hormones 35 . Spineless increased expression of sc, numb and Pdp1 in GFP high cells. Sli encodes Slit, a ligand for the receptor Robo2. The Slit/Robo2 pathway forms part of a negative feedback loop that limits commitment to the enteroendocrine lineage 63 . We found decreased expression of s li in GFP low cells and of robo2 in GFP high cells from Spineless overexpressing flies. Taken together, the RNA sequencing data suggest that Spineless changes expression of a range of key factors involved in epithelial cell differentiation and might promote cell fate specification of enteroendocrine cells.

Spineless and AHR regulate common target genes in the intestinal epithelium

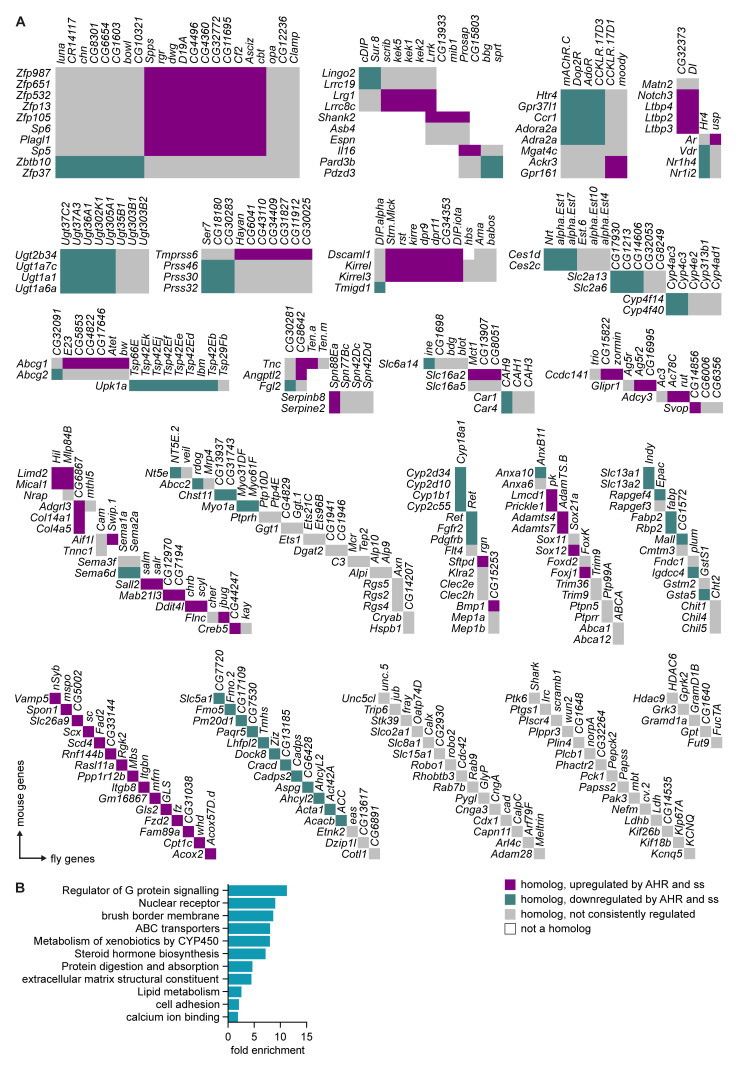

To determine if AHR and Spineless had evolutionary conserved target genes in the intestinal epithelium, we generated a list of broadly homologous genes that were directly or indirectly regulated by AHR in mouse epithelium and by Spineless in the Drosophila midgut. This yielded 213 mouse genes and 260 homologous fly genes ( Figure 6A). We then used gene ontology analysis of the mouse genes to determine which pathways were regulated by AHR/Spineless ( Figure 6B). Target genes were enriched for pathways critical for mature epithelial cells, such as brush border maintenance, protein digestion and absorption and the extracellular matrix. Several enriched pathways were similar to those enriched in ssHA compared to control, such as lipid metabolism and calcium ion binding. These data suggest that AHR and Spineless control over 200 evolutionarily conserved genes, many of which have key functions in the intestinal epithelium.

Figure 6. Regulation of evolutionarily conserved genes by Spineless and AHR.

A) Homology between mouse genes regulated by AHR and fly genes regulated by Spineless. Beyond the homolog clusters, genes are arranged in no particular order. B) Gene ontology analysis using DAVID of AHR-regulated mouse genes with homology to fly genes with differential expression between esg ts>GFP.NLS,ssHA and esg ts>GFP.NLS samples. Selected pathways are shown.

yki act induces proliferation and changes cellular metabolism in the midgut

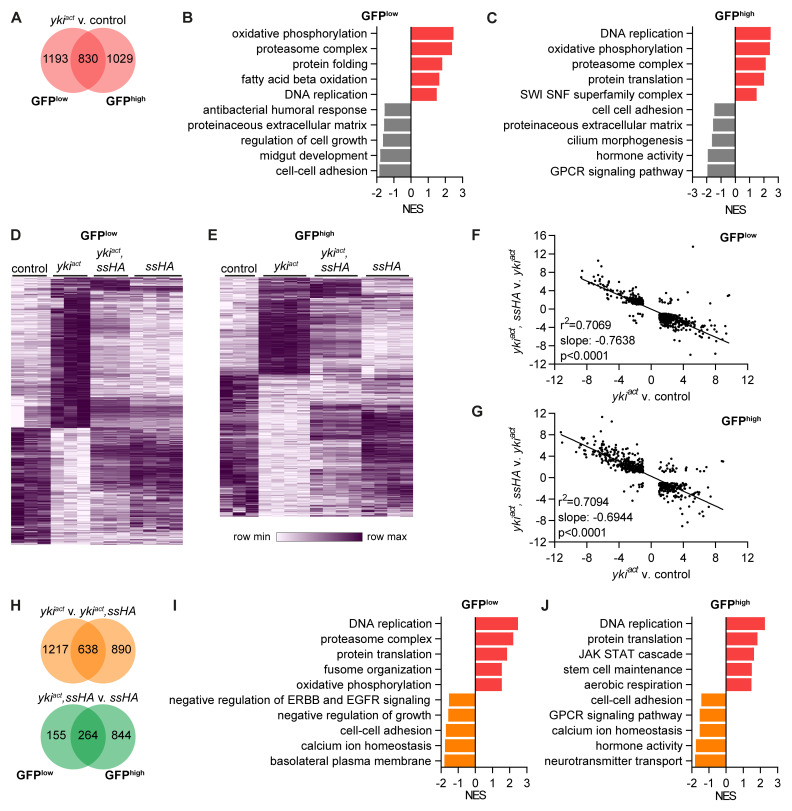

Next, we analysed the pathways that were differentially expressed in yki act tumour samples. Tumour cells clustered farthest from control cells on the PCA ( Figure 5A) and correspondingly had the highest number of differentially expressed genes, 2023 in GFP low and 1859 in GFP high cells, 830 of which were in common ( Figure 7A). Tumour GFP low cells were enriched for pathways relating to cell proliferation such as DNA replication and showed an altered metabolism with increased expression of oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid beta oxidation pathways ( Figure 7B). Pathways relating to cell-cell adhesion, midgut development, regulation of cell growth, the extracellular matrix and antibacterial response were all downregulated in tumour GFP low cells. In GFP high cells, tumour samples continued to upregulate pathways of cell proliferation and altered metabolism ( Figure 7C). They also upregulated genes in the SWI SNF superfamily complex such as Iswi, Acf, HDAC1 and Nurf-38, which are involved in chromatin remodelling. Tumour GFP high cells downregulated pathways relating to cell-cell adhesion and the extracellular matrix similar to GFP low cells and also reduced expression of genes involved in cilium morphogenesis, GPCR signalling and hormone activity. This shows that yki act tumour cells reduced expression of genes critical for the normal function of epithelial cells in exchange for genes driving proliferation and altered metabolism.

Figure 7. Spineless reverses effects of yki act tumour on gene expression.

A) Number of differentially expressed genes between esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act and esg ts>GFP.NLS samples (padj<0.05, |FC|>2). B, C) Gene set enrichment analysis comparing B) GFP low and C) GFP high cells from esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act to esg ts>GFP.NLS samples. Selected pathways are shown. D, E) Hierarchical clustering of genes differentially expressed between esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act and esg ts>GFP.NLS samples. D) 2023 genes with differential expression in ISC are shown. E) 1859 genes with differential expression in EB are shown. F, G) Simple linear regression analysis of F) 946 genes in B) GFP low cells and G) 741 genes in GFP high cells that are differentially expressed in both comparisons of esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act to esg ts>GFP.NLS and of esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act,ssHA to esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act . H) Number of differentially expressed genes between esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act to esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act,ssHA samples or between esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act,ssHA to esg ts>GFP.NLS,ssHA samples (padj<0.05, |FC|>2). I, J) Gene set enrichment analysis comparing I) GFP low and J) GFP high cells from esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act to esg ts>GFP.NLS,yki act,ssHA samples. Selected pathways are shown.

Spineless reverses effects of yki act tumour on gene expression

From the PCA it was apparent that yki act tumour samples clustered separately from controls and concurrent spineless overexpression reversed this effect so that yki act,ssHA samples clustered closer to controls. This reversal was also visible on the level of individual genes. Hierarchical clustering of all genes with differential expression in yki act vs. control GFP low cells showed that Spineless reversed the expression of most of those genes ( Figure 7D). This effect was less pronounced in GFP high cells ( Figure 7E). For genes that were differentially expressed in both comparisons ( yki act v. control and yki act,ssHA vs. yki act ), the effect of yki act was almost perfectly reversed by Spineless in both GFP low and GFP high cells ( Figure 7F, G). This effect was also visible in the number of differentially expressed genes between yki act,ssHA vs. yki act , which were similar to the numbers between yki act tumours and controls ( Figure 7H). In contrast, there were only 419 differentially expressed genes in GFP low cells between and yki act,ssHA vs. ssHA, suggesting that the tumours had a limited effect on gene expression in the presence of Spineless. In GFP high cells, the difference was much larger with 1108 genes. On the level of pathways the comparison of yki act vs. yki act,ssHA was similar to that of yki act vs. controls ( Figure 7I, J). Concurrent Spineless overexpression in yki act tumours suppressed the cell proliferation and oxidative phosphorylation pathways and increased pathways relating to normal epithelial function such as cell-cell adhesion, regulation of growth, basolateral membrane, hormone activity and GPCR signalling. These results clearly show that Spineless can largely reverse the effects of yki act on gene expression and as a result restore normal cell function and metabolism pathways in midgut progenitors.

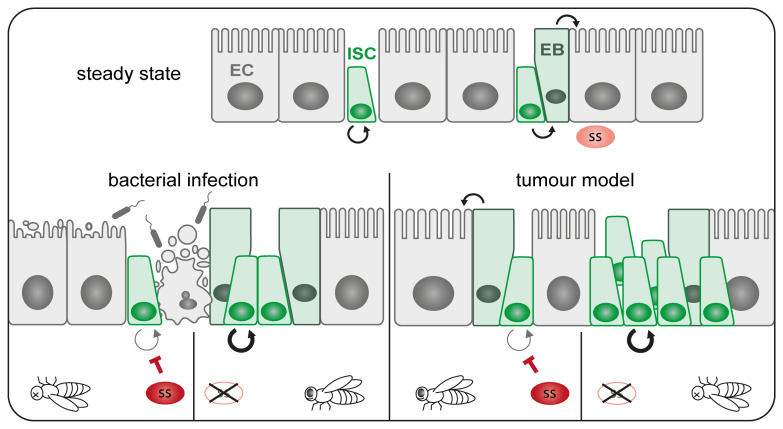

Taken together, our results demonstrate how Spineless can act as a tumour suppressor in the adult Drosophila intestine by limiting stem cell proliferation and promoting epithelial cell differentiation ( Figure 8). This shows that Spineless has functional activity in the adult intestine and adds to a growing body of evidence that Spineless fulfils roles beyond development.

Figure 8. Schematic of Spineless function in the intestine.

At steady state ISC undergo self-renewal in symmetric divisions or asymmetric divisions in to ISC and EB, which in turn give rise to mature enterocytes. Spineless is expressed at low levels during steady state. Bacterial infection leads to epithelial damage and stem cell proliferation to regenerate the epithelium. Spineless overexpression blocks ISC proliferation and reduces survival while spineless inactivation increases ISC proliferation. In tumour models, spineless overexpression blocks tumour growth and promotes differentiation thereby prolonging fly survival. Spineless inactivation accelerates tumour growth and decreases lifespan. EB, enteroblast; EC, enterocyte; ISC, intestinal stem cell; ss, spineless.

Discussion

Our Drosophila study shows that Spineless regulates several conserved pathways in the intestine that are known to be regulated by AHR in mammals. The BMP gradient increases from crypt to villus and drives terminal differentiation of goblet cells and enterocytes in the mammalian intestine 64 . Genes in the BMP pathway were increased by Spineless overexpression in GFP high cells, suggesting that Spineless promotes differentiation of the epithelial lineage. Interactions between AHR and the BMP pathway have previously been suggested 65, 66 , but have not been explored in the intestine. Spineless overexpression also increased expression of cad in GFP low cells. Its homolog Cdx2 is a direct target of AHR in mouse epithelial cells 5 . Both cad and Cdx2 function in regionalization of the intestine 35, 67 . Cad has also been shown to repress antimicrobial genes 68 , which could explain reduced expression of anti-bacterial defence genes following Spineless overexpression. Cad overexpression results in reduced ISC proliferation and epithelial regeneration after injury 69 , similar to what we observed when overexpressing Spineless during P. entomophila infection. Likewise, usp, the homolog of the direct AHR target Rxra 70 was also increased by Spineless. This suggests that AHR/Spineless have evolutionarily conserved target genes with critical functions in epithelial homeostasis.

This work identified novel tumour suppressing functions for Spineless. In mice, AHR was shown to suppress colorectal cancer development in an epithelial cell-intrinsic manner 4, 71 . We found that Spineless inactivation resulted in slightly accelerated death from Notch RNAi tumours and Spineless overexpression delayed tumour growth and drastically prolonged survival in two independent tumour models. The minor effect of Spineless inactivation compared to overexpression may be due to the low baseline expression of Spineless in the midgut, while overexpression increased spineless mRNA 10,000-fold. Spineless may suppress tumour growth on a fundamental level. Our results support two potential tumour-suppressing mechanisms for Spineless: the ability to restrain stem cell proliferation as observed following P. entomophila infection and to promote epithelial differentiation as highlighted by the transcriptomic data. Evidence for Spineless suppressing proliferation was also visible on the mRNA level, where it reversed yki act -induced pathways relating to DNA replication and cell division. Spineless largely reversed the effects of yki act on gene expression and thereby restored normal cell function and metabolism in midgut progenitors. Further experiments are needed to confirm these changes in gene expression on the functional level. AHR was shown to directly affect transcription downstream of the Hippo pathway by restricting chromatin accessibility to Yap/Tead transcriptional targets 5 and to interact with chromatin remodelling complexes 72 . It is possible that Spineless similarly alters chromatin accessibility to repress yki target genes. Previous work found that Spineless binding is associated with chromatin opening during butterfly wing metamorphosis 73 . The role of AHR in cancer in general is still debated and it may differentially affect tumour cells and immune cells 74, 75 . In the mammalian intestine, several studies find beneficial functions for AHR as a tumour suppressor 1 , suggesting that the Drosophila model system could be used to further study tumour suppressing functions of AHR/Spineless.

A limitation of this study is that the findings on the tumour suppressor functions of Spineless are largely based on overexpression studies. We did observe minor effects of Spineless inactivation, which lead to accelerated death in the Notch RNAi tumour model. The effects of Spineless overexpression, however, were much more pronounced and further explored in the yki act tumour model and the RNA sequencing data. It is possible that overexpression of Spineless at such high levels results in the interaction with novel cellular targets and therefore novel phenotypes. In mammals, AHR is needed to end the regenerative response of the intestinal epithelium after injury to allow the epithelial barrier to return to its mature state 5 . Whether Spineless fulfils similar functions by limiting ISC proliferation and promoting differentiation into mature epithelial cells after bacterial infection or in tumour models remains to be tested in flies with Spineless inactivation or knockdown.

Others have shown that Spineless may affect movement, the oxidative stress response, or long-term memory formation in adult flies 76, 77 . Our work adds to this growing body of evidence that Spineless fulfils roles beyond development in adult Drosophila. In a study by Sonowal and colleagues Drosophila healthspan was increased by indoles in a Spineless-dependent manner 78 . This result is surprising given that the ligand-binding domain of AHR is not conserved in Spineless and Spineless nuclear translocation is independent of dioxin 6, 11 . In our study, Spineless inactivation or overexpression had no apparent effect on organismal survival in the absence of tumours.

Spineless function is most likely controlled on the transcriptional level but which factors control its expression or if there are additional protein complexes that can retain Spineless in the cytoplasm similar to AHR is not known. Ligand-dependent activation of AHR in vertebrates might offer an evolutionary advantage by allowing a rapid response and the integration of environmental signals. Despite these differences in activation, AHR and Spineless bind the same DNA sequence and we show here that they regulate evolutionarily conserved target genes and pathways critical for the maintenance of intestinal epithelial homeostasis.

Ethics

Ethical approval was not required.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Science technology platforms at the Francis Crick Institute. We thank the Fly Facility, especially Joachim Kurth for help with microinjections and fly maintenance, the Flow Cytometry Facility, the Advanced Sequencing Facility and the Light Microscopy Facility. We are thankful to Robert Johnston for providing the ss cDNA plasmid, to Nalle Pentinmikko for discussion and reagents and to Oscar Diaz, Anke Liebert, and Murali Rao Maradana for critical reading and discussion of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Wellcome [220497; Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship to N.L.D.] [210556; Wellcome Investigator Award to B.S.]; the Francis Crick Institute, which receives its core funding from Cancer Research UK [CC2016]; the UK Medical Research Council [CC2016].

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 3; peer review: 2 approved, 2 approved with reservations]

Data availability

NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus: The RNA sequencing dataset generated in this study is accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE229388 ( http://identifiers.org/GEO:GSE229388) 79 . BioImage Archive: Original images have been submitted to BioStudies BioImage Archive under accession number S-BIAD1553 ( http://identifiers.org/BioStudies:S-BIAD1553) 80 .

Author contributions

M.T. and J.S. performed and analysed experiments. C.A. designed and created genetically modified flies and designed experiments. M.S. carried out computational analysis of RNA sequencing data. A.F. and Y. L. performed experiments. A.G, J.P.V. and B.S. supervised the project. N.L.D. designed, performed and analysed experiments, supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1. Stockinger B, Shah K, Wincent E: AHR in the intestinal microenvironment: safeguarding barrier function. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(8):559–70. 10.1038/s41575-021-00430-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGuire J, Okamoto K, Whitelaw ML, et al. : Definition of a dioxin receptor mutant that is a constitutive activator of transcription: delineation of overlapping repression and ligand binding functions within the PAS domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(45):41841–9. 10.1074/jbc.M105607200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diny NL, Schonfeldova B, Shapiro M, et al. : The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor contributes to tissue adaptation of intestinal eosinophils in mice. J Exp Med. 2022;219(4): e20210970. 10.1084/jem.20210970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Metidji A, Omenetti S, Crotta S, et al. : The environmental sensor AHR protects from inflammatory damage by maintaining Intestinal Stem Cell homeostasis and barrier integrity. Immunity. 2018;49(2):353–362. e5. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shah K, Maradana MR, Joaquina Delàs M, et al. : Cell-intrinsic Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor signalling is required for the resolution of injury-induced colonic stem cells. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1): 1827. 10.1038/s41467-022-29098-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McMillan BJ, Bradfield CA: The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor sans Xenobiotics: endogenous function in genetic model systems. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(3):487–98. 10.1124/mol.107.037259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Emmons RB, Duncan D, Estes PA, et al. : The spineless-aristapedia and tango bHLH-PAS proteins interact to control antennal and tarsal development in Drosophila. Development. 1999;126(17):3937–45. 10.1242/dev.126.17.3937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duncan DM, Burgess EA, Duncan I: Control of distal antennal identity and tarsal development in Drosophila by spineless-aristapedia, a homolog of the mammalian dioxin receptor. Genes Dev. 1998;12(9):1290–303. 10.1101/gad.12.9.1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kudo K, Takeuchi T, Murakami Y, et al. : Characterization of the region of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor required for ligand dependency of transactivation using chimeric receptor between Drosophila and Mus musculus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789(6–8):477–86. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Butler RA, Kelley ML, Powell WH, et al. : An Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR) homologue from the soft-shell clam, Mya arenaria: evidence that invertebrate AHR homologues lack 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo- p-dioxin and β-naphthoflavone binding. Gene. 2001;278(1–2):223–34. 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00724-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cespedes MA, Galindo MI, Couso JP: Dioxin toxicity in vivo results from an increase in the dioxin-independent transcriptional activity of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. PLoS One. 2010;5(11): e15382. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Struhl G: Spineless-aristapedia: a homeotic gene that does not control the development of specific compartments in Drosophila. Genetics. 1982;102(4):737–49. 10.1093/genetics/102.4.737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kozu S, Tajiri R, Tsuji T, et al. : Temporal regulation of late expression of Bar homeobox genes during Drosophila leg development by Spineless, a homolog of the mammalian dioxin receptor. Dev Biol. 2006;294(2):497–508. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Emmons RB, Duncan D, Duncan I: Regulation of the Drosophila distal antennal determinant spineless. Dev Biol. 2007;302(2):412–26. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]