ABSTRACT

Tacrolimus (Tac) is an immunosuppressive drug used to reduce the risk of allograft rejection; however, it can induce renal injury. High mobility group box 1 (HMGB‐1) protein, which induces inflammation through the aberrant stimulation of the Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4)/myeloid differentiation primary response protein (MyD88)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB) trajectory, could represent a molecular target for alleviating Tac‐induced renal damage. The present study aimed to investigate the potential protective role of the GLP‐1 agonist, dulaglutide (Dula), against Tac‐induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Rats were administered Tac (5 mg/kg/day) and vehicle or Dula (0.2 mg/kg once a week) for 14 days. Treatment with Dula reduced serum creatinine plus blood urea nitrogen and attenuated Tac‐induced renal histopathological changes. Dula treatment also hampered renal inflammation and restored redox homeostasis, as indicated by remarkably reduced tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α), interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β), malondialdehyde (MDA), and NADPH oxidase 1 levels alongside marked replenishment in reduced glutathione (GSH) content. These effects were mediated through the upregulation of miR‐22 expression and the consequent inhibition of the HMGB‐1/TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB trajectory. Collectively, Dula has been demonstrated to protect rats against Tac‐induced nephrotoxicity by reducing inflammation, restoring redox homeostasis, and modulation of the miR‐22/HMGB‐1/TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB trajectory. Dula may be beneficial clinically in preventing Tac‐induced renal injury.

Keywords: dulaglutide, HMGB‐1, miR‐22, nephrotoxicity, tacrolimus, TLR4

Initial in‐vivo evidence is given for the capacity of dulaglutide to improve kidney function in tacrolimus‐induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Dulaglutide reduced renal inflammation and restored redox homeostasis. Mechanistically, the nephroprotective effect of dulaglutide was potentially mediated through modulation of the miR‐22/HMGB‐1/TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB trajectory.

1. Introduction

Tacrolimus (Tac), a calcineurin inhibitor, is a commonly prescribed immunosuppressive drug that is clinically used to decrease allograft rejection risk in transplant recipients. Meanwhile, Tac‐induced kidney injury is considered the major factor limiting its long‐term use [1]. Remarkably, molecular mechanisms underlying the reported nephrotoxicity following Tac exposure remain unclear, but the disruption of redox homeostasis or the induction of inflammatory responses are commonly proposed mechanisms [2, 3].

High mobility group box 1 (HMGB‐1) is a nonhistone chromatin‐related DNA‐binding protein that plays a pivotal role in regulating DNA transcriptional activity. Notably, HMGB‐1 is ubiquitously expressed in nearly all cell types including renal cells [4]. Of note, HMGB‐1 overexpression was formerly displayed to be implicated in the pathologies of a number or diseases including hypoxia [5], Osteoarthritis [6], cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury [7], and traumatic brain injury [8].

Additionally, Emerging evidence highlighted the fundamental role of HMGB‐1 expression in the pathogenesis of a plethora of renal disorders including renal inflammation [4], diabetic kidney disease or diabetic nephropathy [9, 10], lupus nephritis [11], acute kidney injury, and chronic renal diseases [12]. HMGB‐1‐induced inflammation is mediated through the aberrant stimulation of the Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4)/myeloid differentiation primary response protein (MyD88)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB) trajectory [13]. Therefore, HMGB‐1 represents a novel potential molecular target for alleviating Tac‐induced renal injury.

Micro‐RNAs are short noncoding RNA strands (18–25 nucleotides) that regulate gene expression by stimulating mRNA degradation [14, 15]. Micro‐RNAs are central to various cellular physiological and pathological functions such as anti‐inflammatory activity, proliferation, angiogenesis, cell repair mechanisms, and carcinogenesis [16]. For instance, microRNA‐22 (miR‐22) is a 22‐nucleotide noncoding micro‐RNA that was reported to be involved in the pathophysiology of sepsis‐triggered acute renal damage [17]. Evidently, accumulating evidence highlighted the implication of miR‐22 in a range of physiological activities that encompass cellular metabolism, epigenetic modification plus embryonic development [18]. The crosstalk between miR‐22 and HMGB‐1 was highlighted by earlier in‐vitro reports that demonstrated the capacity of miR‐22 to regulate HMGB‐1 function in vascular smooth muscle cells, retinoblastoma alongside osteosarcoma leading to hampering of cell proliferation and migration [19, 20, 21]. In this regard, the potential role of miR‐22 in attenuating Tac‐induced renal damage via modulating HMGB‐1 expression with subsequent suppression of the TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB signaling has not been fully explored.

Dulaglutide (Dula) belongs to glucagon‐like‐peptide 1 receptor (GLP‐1R) agonists that is approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Since GLP‐1R is ubiquitously expressed in the kidney, GLP‐1R agonists enhance kidney outcomes in individuals with diabetic kidney disease [22]. Of note, Dula has demonstrated renoprotective effects in both clinical and preclinical studies. Clinically, dulaglutide use is associated with improved renal outcomes, including a slower decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and a reduced incidence of end‐stage kidney disease events [23, 24]. Preclinical studies further elucidate these benefits, showing that Dula ameliorates kidney damage by modulating inflammatory responses, reducing oxidative stress, and decreasing fibrosis. Collectively, these findings suggest that Dula's protective effects on diabetic kidney disease are mediated, at least in part, through its influence on inflammatory, oxidative stress, and fibrotic pathways [25]. In addition, an earlier in‐vitro model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)‐induced cardiomyocyte damage highlighted the alleviation of LPS‐induced inflammatory responses following Dula treatment. This observation was potentially ascribed to the reported modulation of TLR4/Myd88/NF‐κB cascade following Dula administration [26]. Since modulating Tac‐induced renal injury represents an unmet clinical need, the current study aimed at investigating Dula's potential effectiveness in mitigating Tac‐induced renal damage in rats and identifying its molecular mechanisms, particularly the role of the miR‐22/HMGB‐1/TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB signaling pathway.

2. Results

2.1. Dula Ameliorates the Deterioration in Renal Function Induced by Tac

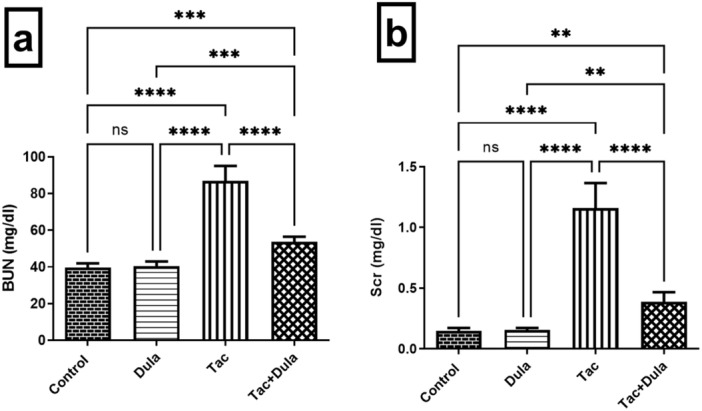

Figure 1 illustrates an increment in the serum levels of BUN and Scr to reach 2.19‐ and 7.83‐folds, respectively, following repeated injection of Tac compared with the normal rats. Dula administration induced a remarkable reduction in the levels of BUN and Scr by 38.30% and 66.66%, respectively, as compared with the Tac‐exposed group.

Figure 1.

Influence of Dula treatment on renal function in the Tac‐treated rats; (a) BUN and (b) Scr. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D. (six rats/group). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001, ns = no significance. Dula, Dulaglutide; Tac, tacrolimus.

2.2. Dula Hampers Tac‐Induced Inflammatory Changes

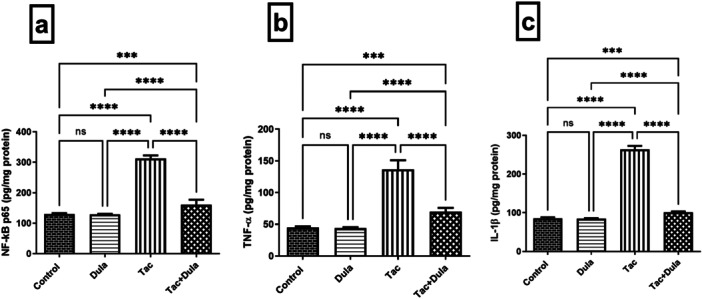

Tac triggered an inflammatory status as evidenced by the marked elevation in the renal contents of NF‐kB p65, TNF‐α, and IL‐1β to 2.40‐, 3.04‐ and 1.91‐folds, respectively, with respect to the normal control group (Figure 2). Treatment with Dula substantially decreased the levels of those markers by 48.46%, 48.99%, and 61.77%, respectively, as compared to Tac‐exposed rats.

Figure 2.

Effect of Dula treatment on inflammatory markers in the Tac‐treated rats: (a) NF‐kB p65, (b) TNF‐α, and (c) IL‐1β. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 6 rats in each group). Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by Turkey's Multiple Comparisons test. ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001, ns = no significance. Dula, Dulaglutide; Tac, tacrolimus.

2.3. Dula Diminishes Tac‐Induced Oxidative Stress

The Tac‐induced redox imbalance (Figure 3) was demonstrated by the marked elevation in NOX‐1 and MDA contents by 2.90‐ and 3.83‐folds, respectively, together with a significant depletion in renal GSH content by 54.36% compared with control rats. However, Dula exhibited a significant antioxidant effect verified by its ability to reduce NOX‐1 and MDA contents by 53.55% and 54.63%, respectively, and enhance GSH level by 1.73‐folds compared with the Tac‐intoxicated rats.

Figure 3.

Effect of Dula treatment on oxidative stress biomarkers in the Tac‐treated rats: (a) NOX‐1, (b) MDA, and (c) GSH in the Tac‐provoked animals. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D. (six rats/group). Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by Turkey's Multiple Comparisons test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.001, ns = no significance. Dula, Dulaglutide; Tac, tacrolimus.

2.4. Dula Inhibits Tac‐Induced Activation of miR‐22/HMGB‐1/TLR4/MyD88 Trajectory

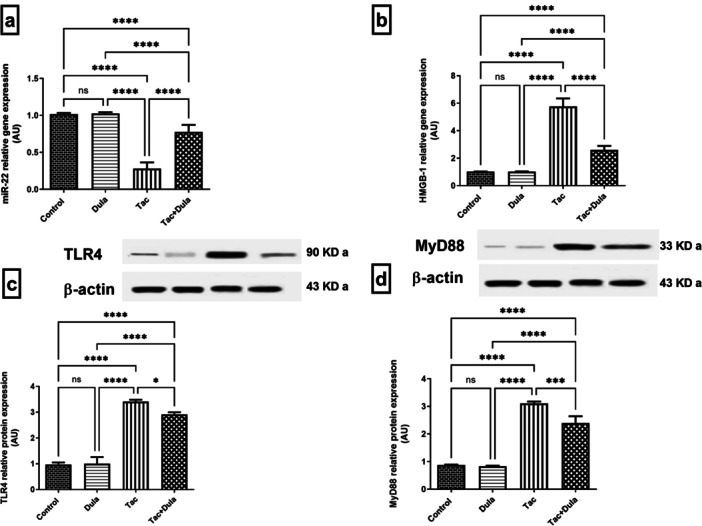

Administration of Tac declined the renal expression of miR‐22 by 72.30%, which caused an upregulation of the mRNA expression of HMGB‐1 and its downstream targets TLR4 and MyD88 protein expressions by 5.67‐, 3.50‐ and 3.56‐folds, respectively, when compared with control rats (Figure 4). Dula treatment increased the miR‐22 mRNA expression by 2.76‐folds together with a remarkable reduction in HMGB‐1 mRNA expression, TLR4, and MyD88 protein expressions by 55.00%, 14.57%, and 22.67%, respectively, as compared to Tac.

Figure 4.

Influence of Dula treatment on expression of (a) miR‐22, (b) HMGB‐1, (c) TLR4, and (d) MyD88 in the Tac‐treated animals. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D. (six rats/group for RT‐PCR and three rats/group for W.B.). Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by Turkey's Multiple Comparisons test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001, ns = no significance. Dula, Dulaglutide; Tac, tacrolimus.

2.5. Dula Improves Histopathological Changes Induced by Tac

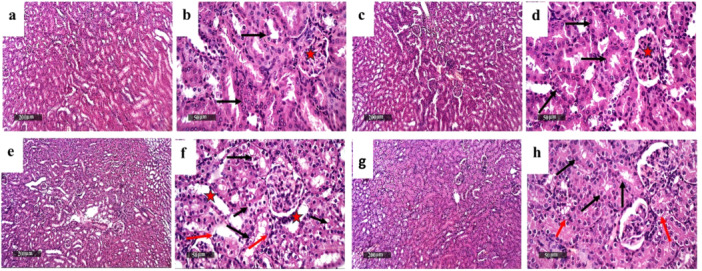

As apparent from Figure 5, photomicrograph sections from control (Figure 5a,b) and Dula alone (Figure 5c,d) revealed almost intact well‐organized morphological features of the renal parenchyma. In contrast, sections of Tac (Figure 5e,f) revealed focal figures of tubular vacuolar degenerative changes at cortical and corticomedullary zone segments accompanied by mild tubular dilation alongside mild interstitial mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates. Conversely, sections of the Dula‐treated rats (Figure 5g,h) showed significant renoprotective potential, as evidenced by intact nephronal segments of the epithelium with preserved integrity.

Figure 5.

Effect of Dula treatment on Tac‐induced histopathological alterations. Sections (a and b) control and (c and d) Dula revealed almost intact, well‐organized morphological characteristics of renal parenchyma with abundant records of apparent intact nephron segments with mostly preserved tubular epithelium (arrow), minimal evidence of degenerated tubular epithelial cells, intact renal corpuscles (star), and intact vasculatures. In contrast, sections of Tac (e and f) revealed focal figures of tubular vacuolar degenerative changes records at cortical and corticomedullary zone segments (black arrow) accompanied with mild tubular dilation (star) as well as mild interstitial mononuclear inflammatory cells infiltrates were shown (red arrow). In contrast, sections of the Dula‐treated rats (g and h) showed significant renoprotective potential evidenced by intact nephron segments epithelium with preserved integrity (black arrow), minimal sporadic degenerative changes (red arrow) without abnormal tubular dilatations or inflammatory infiltrates.

3. Discussion

The discovery of immunosuppressive drugs, including Tac, has revolutionized the field of organ transplantation because they significantly have increased the success rate of such surgeries. However, Tac administration is implicated in inducing irreversible kidney injury, including glomerulosclerosis, atrophy of the renal tubules, arteriolar hyalinosis, and interstitial fibrosis [27]. This requires the establishment of an innovative therapeutic strategy to minimize the damaging effect of Tac on the kidney. Our investigation has demonstrated the first in‐vivo evidence on the potential protective role of Dula in mitigating Tac‐induced nephrotoxicity then we have unraveled the role of miR‐22/HMGB‐1/TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB signaling pathway modulation in mediating such effect.

Findings of the current investigation demonstrated that Tac‐provoked rats exhibited a profound deterioration in renal function as evidenced by the significant elevation in SCr and BUN, suggesting Tac‐induced renal damage that was further confirmed by the histopathological examination showing tubular degeneration and interstitial inflammatory reactions following Tac exposure. These findings align well with earlier reports [28, 29]. However, treatment with Dula succeeded in attenuating Tac‐induced changes in kidney function and histopathology.

HMGB‐1, a highly abundant nuclear protein, has recently emerged as a key player in pathogenesis of renal diseases [12]. Extracellular HMGB‐1 was documented to intensify macrophage inflammation and is clearly linked to the degree of histopathological changes of renal tissue damage in lupus nephritis [30, 31]. Moreover, earlier investigations reported HMGB‐1 upregulation in chronic kidney disease [32]. HMGB‐1 exhibits a crucial proinflammatory activity ascribed to its capacity to bind to transmembrane receptors, including TLR4 [33]. Significantly, HMGB‐1 is an endogenous agonist for TLR4; once activated, it triggers NF‐κB translocation with consequent activation of the downstream NF‐κB inflammatory axis via a MyD88‐dependent manner [34]. Sequentially, stimulation of the NF‐κB signaling triggers a series of inflammatory responses via stimulating the expression of its target genes and inducing proinflammatory cytokines secretion (e.g., IL‐1β and TNF‐α), causing significant tissue damage [35]. Remarkably, amplification of inflammatory responses could take place owing to TNF‐α release stimulating further HMGB‐1 secretion and organ damage in a positive feedback manner [36].

The findings of the present report showed a profound elevation in HMGB‐1 expression in the kidney of Tac‐intoxicated animals. Our results also revealed that the Tac‐treated group showed a remarkably enhanced expression of TLR4 and MyD88 as well as NF‐κB p65, TNF‐α, and IL‐1β levels. The participation of TLR4 in both acute and chronic inflammatory renal injury has been previously documented. TLR4 stimulation was shown to be involved in the development of interstitial nephritis mainly through stimulation of proinflammatory cytokines synthesis [37]. It has been documented that calcineurin inhibitors like Tac exhibit toxicity via modulation of the TLR4/MyD88 signaling axis with subsequent increased proinflammatory mediators' synthesis in NF‐κB dependent mechanism [3]. Our results are also in line with earlier reports stating the association between HMGB‐1 alongside TLR4/Myd88/NF‐κB trajectory as well as their potential role in various kidney injury models [38, 39] including Tac‐induced renal injury [40]. Notably, treatment with Dula ameliorated Tac‐induced changes in the expression HMGB‐1, TLR4, and MyD88, alongside the levels of NF‐κB p65, TNF‐α, and IL‐1β. These findings accord well with an earlier investigation that provided initial in‐vitro evidence that Dula‐mediated suppression of TLR4/Myd88/NF‐κB signaling cascade plus its downstream proinflammatory cytokines could be ascribed to the reported attenuation of LPS‐induced inflammation [26]. The anti‐inflammatory effect of Dula was previously documented in both in‐vitro [26] and in‐vivo [41, 42] studies.

The current study showed remarkable downregulation of miR‐22 gene expression in the renal tissue of Tac‐provoked animals. This observation accords well with previous reports showing that HMGB‐1 is a target gene for miR‐22 [19, 20, 43]. Consistently, an earlier study has reported miR‐22 as an inhibitor for TLR4 gene expression via targeting HMGB‐1 in sepsis‐induced kidney injury model [17]. Additionally, our findings demonstrated a profound upregulation of miR‐22 gene expression in kidney tissue following Dula treatment accompanied by a significant downregulation of the HMGB‐1/TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB signaling cascade.

Previous studies also highlighted that redox imbalance and oxidative stress are principal culprits of Tac‐induced nephrotoxicity and renal inflammation [1, 44, 45]. In this setting, our results displayed a profound increase in MDA and NOX‐1 levels with remarkable suppression of GSH content in the Tac‐administered group. Reportedly, oxidative stress is strongly associated with elevated inflammatory cytokine levels due to hyper‐activation of the innate immunity system with subsequent renal tissue damage [46, 47]. Of note, TLR4 signaling activation can increase NOX‐1 expression that stimulates the release of reactive oxygen species with subsequent lipid peroxidation and depletion of antioxidant defense enzymes, thereby inducing kidney damage [48]. However, Dula treatment attenuated Tac‐induced oxidative stress, which is in accordance with earlier studies documenting the antioxidant effects of Dula in different diseases [49, 50, 51]. The primary limitation of this study is the lack of knockout or silencing experiments for miR‐22/HMGB‐1, which would have provided more definitive insights into their functional roles. Future studies should incorporate these approaches to further validate our findings.

4. Conclusion

Our results are the first to reveal Dula's nephroprotective potential in mitigating Tac‐induced nephrotoxicity in rats via modulation of miR‐22/HMGB‐1/TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB trajectory. Thus, Dula may be beneficial clinically in preventing Tac‐induced renal injury. Notably, further preclinical and clinical studies are required for evaluating the potential benefit of Dula in mitigating Tac‐induced renal toxicity in organ transplant recipients. Clinically, current data establish a platform for the development of a novel therapeutic approach for alleviating Tac‐induced nephrotoxicity that represent a major limitation for its clinical use in organ transplant recipients.

5. Experimental

5.1. Animals

Male Wistar rats (150–200 g) were procured from the animal facility of the Egyptian Drug Authority (Cairo, Egypt) to be used in the present study. Rats were housed under controlled conditions including humidity (60% ± 10%), room temperature (25°C ± 2°C), and 12‐h light‐dark cycle. They were granted free access to food and water ad libitum. The study protocol was reviewed then approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University (Permit Number: PT 3351). The study procedures were in accordance with the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals for all experiments. Reporting of animal experiments is in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0.

5.2. Drugs and Chemicals

Dula and Tac were purchased from Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, Indiana, United States) and Astellas (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. They were dissolved in normal saline. All chemicals and reagents used were of the highest commercially available quality.

5.3. Experimental Design

A total of 36 rats were arbitrarily divided into four groups with nine animals each.

-

∘

Group I (normal control group): received saline i.p. daily for 14 days and s.c once a week.

-

∘

Group II (Dula): received Dula (0.2 mg/kg/week, s.c.) once a week [52].

-

∘

Group III (Tac): received Tac (5 mg/kg, i.p.) daily for 14 days [53].

-

∘

Group IV (Tac + Dula): received Tac (5 mg/kg, i.p.) daily for 14 days and Dula (0.2 mg/kg, s.c.) once a week.

Twenty‐four hours after the last injection of Tac, animals were anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital (10 mg/kg, i.p.) [54]. Blood samples were withdrawn from the retro‐orbital plexus and collected in non‐heparinized tubes. Then, rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Both kidneys of each animal were rapidly excised and divided into two sets. Kidneys of the first set (n = 6) were stored at −80°C, where the right kidneys were used for ELISA and Western blot analysis, and the left kidneys were used for RT‐qPCR analysis. Kidneys of the second set (n = 3) were immersed in formalin [10% (v/v)] for 24 h then were used for histopathological examination.

5.4. Biochemical Parameters

5.4.1. Assessment of Renal Function

Both blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (Scr) levels were estimated using kits supplied by Biomed‐Egychem (Badr City, Cairo, Egypt).

5.4.2. Measurement of Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

Renal lipid peroxidation was assessed colorimetrically via measuring the malondialdehyde (MDA) level through reaction with thiobarbituric acid [55] using Biodiagnostic Egypt (Dokki, Giza, Egypt) kit. Besides, reduced glutathione (GSH) content was quantified via a colorimetric assay using Ellman's reagent [56].

5.4.3. Enzyme‐Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Renal NF‐κB p65, interleukin (IL)‐1β, and NADPH oxidase 1 (NOX‐1) levels were assesed using rat ELISA kits (MyBiosource Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) (Cat# MBS 2505513, MBS 825017, and MBS 2702015, respectively). Similarly, renal tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α) levels were quantified using rat ELISA kits (Cusabio, Huston, TX, USA) (Cat# CSB‐E11987r). We followed the instructions directed by the manufacturer for all the procedures. Protein content was measured using a previously reported method by [57].

5.4.4. Western Blot Analysis

After the determination of renal tissue total protein, equal amounts of protein were loaded onto 8% SDS‐PAGE gel and then resolved by electrophoresis based on their molecular weight. Then, proteins were electroblotted using a semidry transfer system (Bio‐Rad Laboratories GmbH, München, Germany) onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Next, the membranes were soaked in a blocking solution composed of Tris‐buffered saline with Tween‐20 (0.05%) and skimmed milk (5%) at 4°C for 12 h. After that, the membranes were exposed to antibodies specific for TLR4 (Cat# 48‐2300), MyD88 (Cat# TA502117), and β‐actin (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). Horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated antibodies were added after washing. Eventually, enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Amer‐sham Biosciences, Arlington, IL, USA), were used for developing the blots and the intensity of the resulted bands was assessed for each target protein after normalization to β‐actin.

5.4.5. Real‐Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT‐qPCR)

RT‐qPCR detected the mRNA expression of both miR‐22 and HMGB‐1 following total renal RNA extraction using the SV Total RNA Isolation system (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Then, an RT‐PCR kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) was used for reverse‐transcription of the isolated RNA into cDNA. qRT‐PCR was carried out with SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). A similar procedure was employed for miR‐22 extraction using the mirVana™ PARIS™ kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA). cDNA synthesis for miR‐22 was performed with the TaqMan™ MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA), followed by qRT‐PCR using the TaqMan™ MicroRNA Assay (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Table 1 shows the primers used for PCR analysis. β‐actin served as the internal control for normalizing HMGB‐1 mRNA expression, while U6 was used to normalize miR‐22 expression. Target genes relative expression levels were measured using the 2−ΔΔCT method [58]. The results are expressed as fold changes.

Table 1.

Primer sequences utilized in qRT‐PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| miR‐22 | GAGCTGCACTGACCAGTAGG | GTGCTGGCAGATGGATCACT |

| HMGB‐1 | TGATTAATGAATGAGTTCGGGC5 | TGCTCAGGAAACTTGACTGTTT |

| β‐actin | TGACTGACTACCTCATGAAGATCC | TCTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATT |

| U6 | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA | AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

5.5. Histopathological Assessment

After killed, the rats' kidneys were washed with saline, then fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h, followed by gradient alcohol dehydration, then cleared with xylene. Renal samples were embedded in paraffin (at 56°C for 24 h) and were sectioned at 4 µm. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The slides were ultimately analyzed using a light microscope.

5.6. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (S.D.) and analyzed using a one‐way analysis of variance followed by Turkey's multiple comparison test. Statistical graphs were produced using GraphPad Prism software (version 8; San Diego, CA, USA). The p values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this study through project number (TU‐DSPP‐2024‐116). This current work was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project number (TU‐DSPP‐2024‐116). Author Hany H. Arab has received the specified research support from Taif University, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Vandenbussche C., Van der Hauwaert C., Dewaeles E., et al., “Tacrolimus‐Induced Nephrotoxicity in Mice Is Associated With Microrna Deregulation,” Archives of Toxicology 92 (2018): 1539–1550, 10.1007/s00204-018-2158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Terzi F. and Ciftci M. K., “Protective Effect of Silymarin on Tacrolimus‐Induced Kidney and Liver Toxicity,” BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 22 (2022): 331, 10.1186/s12906-022-03803-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodrigues‐Diez R., González‐Guerrero C., Ocaña‐Salceda C., et al., “Calcineurin Inhibitors Cyclosporine A and Tacrolimus Induce Vascular Inflammation and Endothelial Activation Through TLR4 Signaling,” Scientific Reports 6 (2016): 27915, 10.1038/srep27915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu T., Li Q., Jin Q., et al., “Targeting HMGB1: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Chronic Kidney Disease,” International Journal of Biological Sciences 19 (2023): 5020–5035, 10.7150/ijbs.87964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reismann M., Wehrmann F., Schukfeh N., Kuebler J. F., Ure B., and Glüer S., “Carbon Dioxide, Hypoxia and Low pH Lead to Overexpression of C‐myc and HMGB‐1 Oncogenes in Neuroblastoma Cells,” European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 19 (2009): 224–227, 10.1055/s-0029-1202778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ke X., Jin G., Yang Y., et al., “Synovial Fluid HMGB‐1 Levels Are Associated With Osteoarthritis Severity,” Clinical Laboratory 61 (2015): 809–818, 10.7754/clin.lab.2015.141205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tao X., Sun X., Yin L., et al., “Dioscin Ameliorates Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Through the Downregulation of TLR4 Signaling via HMGB‐1 Inhibition,” Free Radical Biology and Medicine 84 (2015): 103–115, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu Y., Ni H., Chen Q., et al., “Inhibition of BRD4 Expression Attenuates the Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis by Downregulating the HMGB‐1/NF‐κB Signaling Pathway Following Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats,” Neuroscience Letters 812 (2023): 137385, 10.1016/j.neulet.2023.137385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu C., Cheng Y., Liu Z., and Fu X., “Hedysarum Polybotrys Polysaccharide Attenuates Renal Inflammatory Infiltration and Fibrosis in Diabetic Mice by Inhibiting the HMGB1/RAGE/TLR4 Pathway,” Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 26 (2023): 493, 10.3892/etm.2023.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang Y., “MiR‐92d‐3p Suppresses the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy Renal Fibrosis by Inhibiting the C3/HMGB1/TGF‐β1 Pathway,” Bioscience Reports 41 (2021): BSR20203131, 10.1042/BSR20203131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li S., Ruan D., Wu W., et al., “Potential Regulatory Role of the Nrf2/HMGB1/TLR4/NF‐κB Signaling Pathway in Lupus Nephritis,” Pediatric Rheumatology 21 (2023): 130, 10.1186/s12969-023-00909-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou T. B., “Role of High Mobility Group Box 1 and Its Signaling Pathways in Renal Diseases,” Journal of Receptors and Signal Transduction 34 (2014): 348–350, 10.3109/10799893.2014.904875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J., Chen Q., Dai Z., and Pan H., “miR‐22 Alleviates Sepsis‐Induced Acute Kidney Injury via Targeting the HMGB1/TLR4/NF‐κB Signaling Pathway,” International Urology and Nephrology 55 (2023): 409–421, 10.1007/S11255-022-03321-2/FIGURES/9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bartel D. P., “MicroRNAs: Target Recognition and Regulatory Functions,” Cell 136 (2009): 215–233, 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanei M. and Chen X., “Mechanisms of microRNA Turnover,” Current Opinion in Plant Biology 27 (2015): 199–206, 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farh K. K.‐H., Grimson A., Jan C., et al., “The Widespread Impact of Mammalian MicroRNAs on mRNA Repression and Evolution,” Science 310 (2005): 1817–1821, 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang H., Che L., Wang Y., et al., “Deregulated microRNA‐22‐3p in Patients With Sepsis‐Induced Acute Kidney Injury Serves as a New Biomarker to Predict Disease Occurrence and 28‐Day Survival Outcomes,” International Urology and Nephrology 53 (2021): 2107–2116, 10.1007/s11255-021-02784-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiong J., “Emerging Roles of microRNA‐22 in Human Disease and Normal Physiology,” Current Molecular Medicine 12 (2012): 247–258, 10.2174/156652412799218886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guo S., Bai R., Liu W., et al., “miR‐22 Inhibits Osteosarcoma Cell Proliferation and Migration by Targeting HMGB1 and Inhibiting HMGB1‐Mediated Autophagy,” Tumor Biology 35 (2014): 7025–7034, 10.1007/s13277-014-1965-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu M., Wang S. M., Jiang Z. X., Lauren H., and Tao L. M., “Effects of miR‐22 on Viability, Migration, Invasion and Apoptosis in Retinoblastoma Y79 Cells by Targeting High‐Mobility Group Box 1,” International Journal of Ophthalmology 11 (2018): 1600–1607, 10.18240/ijo.2018.10.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang S., Wang M., Wu W., et al., “Mir‐22‐3p Inhibits Arterial Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Migration and Neointimal Hyperplasia by Targeting HMGB1 in Arteriosclerosis Obliterans,” Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 42 (2017): 2492–2506, 10.1159/000480212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawanami D. and Takashi Y., “GLP‐1 Receptor Agonists in Diabetic Kidney Disease: From Clinical Outcomes to Mechanisms,” Frontiers in Pharmacology 11 (2020): 967, 10.3389/fphar.2020.00967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Botros F. T., Gerstein H. C., Malik R., et al., “Dulaglutide and Kidney Function–Related Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A REWIND Post Hoc Analysis,” Diabetes Care 46 (2023): 1524–1530, 10.2337/dc23-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim S., An J. N., Song Y. R., Kim S. G., Lee H. S., and Cho A., “Effect of Once‐Weekly Dulaglutide on Renal Function in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease,” PLoS One 17 (2022): e0273004, 10.1371/journal.pone.0273004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. El Amin Ali A. M., Osman H. M., Zaki A. M., et al., “Reno‐Protective Effects of GLP‐1 Receptor Agonist and Anti‐Platelets in Experimentally Induced Diabetic Kidney Disease in Male Albino Rats,” Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences 25 (2022): 1487–1497, 10.22038/IJBMS.2022.65061.14494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang R., Wang N., Han Y., Xu J., and Xu Z., “Dulaglutide Alleviates LPS‐Induced Injury in Cardiomyocytes,” ACS Omega 6 (2021): 8271–8278, 10.1021/acsomega.0c06326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chapman J. R., “Chronic Calcineurin Inhibitor Nephrotoxicity—Lest We Forget,” American Journal of Transplantation: Official Journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons 11 (2011): 693–697, 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Azouz A. A., Omar H. A., Hersi F., Ali F. E. M., and Hussein Elkelawy A. M. M., “Impact of the ACE2 Activator Xanthenone on Tacrolimus Nephrotoxicity: Modulation of Uric Acid/ERK/p38 MAPK and Nrf2/SOD3/GCLC Signaling Pathways,” Life Sciences 288 (2022): 120154, 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shigematsu T., Tajima S., Fu R., et al., “The mTOR Inhibitor Everolimus Attenuates Tacrolimus‐Induced Renal Interstitial Fibrosis in Rats,” Life Sciences 288 (2022): 120150, 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu J., Yue Y., and Xiong S., “Extracellular HMGB1 Augments Macrophage Inflammation by Facilitating the Endosomal Accumulation of ALD‐DNA via TLR2/4‐Mediated Endocytosis,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) ‐ Molecular Basis of Disease 1867 (2021): 166184, 10.1016/j.bbadis.2021.166184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu T., Xiaojuan F., Jinxi L., et al., “Extracellular HMGB1 Induced Glomerular Endothelial Cell Injury via TLR4/MyD88 Signaling Pathway in Lupus Nephritis,” Mediators of Inflammation 1 (2021): 1–15, 10.1155/2021/9993971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leelahavanichkul A., Huang Y., Hu X., et al., “Chronic Kidney Disease Worsens Sepsis and Sepsis‐Induced Acute Kidney Injury by Releasing High Mobility Group Box Protein‐1,” Kidney International 80 (2011): 1198–1211, 10.1038/ki.2011.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen X., Wu S., Chen C., et al., “Omega‐3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation Attenuates Microglial‐Induced Inflammation by Inhibiting the HMGB1/TLR4/NF‐κB Pathway Following Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury,” Journal of Neuroinflammation 14 (2017): 143, 10.1186/s12974-017-0917-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang Z., Liu Q., Liu M., et al., “Upregulation of HMGB1‐TLR4 Inflammatory Pathway in Focal Cortical Dysplasia Type II,” Journal of Neuroinflammation 15 (2018): 27, 10.1186/s12974-018-1078-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Park J. S., Gamboni‐Robertson F., He Q., et al., “High Mobility Group Box 1 Protein Interacts With Multiple Toll‐Like Receptors,” American Journal of Physiology‐Cell Physiology 290 (2006): C917–C924, 10.1152/ajpcell.00401.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lu Y.‐C., Yeh W.‐C., and Ohashi P. S., “LPS/TLR4 Signal Transduction Pathway,” Cytokine 42 (2008): 145–151, 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Svensson M., Yadav M., Holmqvist B., Lutay N., Svanborg C., and Godaly G., “Acute Pyelonephritis and Renal Scarring Are Caused by Dysfunctional Innate Immunity in mCxcr2 Heterozygous Mice,” Kidney International 80 (2011): 1064–1072, 10.1038/ki.2011.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mohamed M. E., Abduldaium Y. S., and Younis N. S., “Ameliorative Effect of Linalool in Cisplatin‐Induced Nephrotoxicity: The Role of HMGB1/TLR4/NF‐κB and Nrf2/HO1 Pathways,” Biomolecules 10 (2020): 1488, 10.3390/biom10111488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Michel H. E. and Menze E. T., “Tetramethylpyrazine Guards Against Cisplatin‐Induced Nephrotoxicity in Rats Through Inhibiting HMGB1/TLR4/NF‐κB and Activating Nrf2 and PPAR‐γ Signaling Pathways,” European Journal of Pharmacology 857 (2019): 172422, 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zmijewska A. A., Zmijewski J. W., Becker E. J. Jr., Benavides G. A., Darley‐Usmar V., and Mannon R. B., “Bioenergetic Maladaptation and Release of HMGB1 in Calcineurin Inhibitor‐Mediated Nephrotoxicity,” American Journal of Transplantation 21 (2021): 2964–2977, 10.1111/ajt.16561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hupa‐Breier K. L., Dywicki J., Hartleben B., et al., “Dulaglutide Alone and in Combination With Empagliflozin Attenuate Inflammatory Pathways and Microbiome Dysbiosis in a Non‐Diabetic Mouse Model of NASH,” Biomedicines 9 (2021): 353, 10.3390/biomedicines9040353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang Y., Wang Y., Wu Y., and Wang Y., “Dulaglutide Ameliorates Intrauterine Adhesion by Suppressing Inflammation and Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition via Inhibiting the TGF‐β/Smad2 Signaling Pathway,” Pharmaceuticals 16 (2023): 964, 10.3390/ph16070964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li X., Wang S., Chen Y., Liu G., and Yang X., “miR‐22 Targets the 3′ UTR of HMGB1 and Inhibits the HMGB1‐Associated Autophagy in Osteosarcoma Cells During Chemotherapy,” Tumor Biology 35 (2014): 6021–6028, 10.1007/s13277-014-1797-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gao P., Du X., Liu L., et al., “Astragaloside IV Alleviates Tacrolimus‐Induced Chronic Nephrotoxicity via p62‐Keap1‐Nrf2 Pathway,” Frontiers in Pharmacology 11 (2021): 610102, 10.3389/fphar.2020.610102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lim S. W., Jin L., Luo K., et al., “Klotho Enhances FoxO3‐Mediated Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Expression by Negatively Regulating PI3K/AKT Pathway During Tacrolimus‐Induced Oxidative Stress,” Cell Death & Disease 8 (2017): e2972, 10.1038/cddis.2017.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen X., Wei W., Li Y., Huang J., and Ci X., “Hesperetin Relieves Cisplatin‐Induced Acute Kidney Injury by Mitigating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Apoptosis,” Chemico‐Biological Interactions 308 (2019): 269–278, 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li W., He W., Xia P., et al., “Total Extracts of Abelmoschus Manihot L. Attenuates Adriamycin‐Induced Renal Tubule Injury via Suppression of ROS‐ERK1/2‐Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation,” Frontiers in Pharmacology 10 (2019): 567, 10.3389/fphar.2019.00567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Qi M., Yin L., Xu L., et al., “Dioscin Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide‐Induced Inflammatory Kidney Injury via the microRNA let‐7i/TLR4/MyD88 Signaling Pathway,” Pharmacological Research 111 (2016): 509–522, 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Khalaf M. M., El‐Sayed M. M., Kandeil M. A., and Ahmed S., “A Novel Protective Modality Against Rotenone‐Induced Parkinson's Disease: A Pre‐Clinical Study With Dulaglutide,” International Immunopharmacology 119 (2023): 110170, 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chang W., Zhu F., Zheng H., et al., “Glucagon‐Like Peptide‐1 Receptor Agonist Dulaglutide Prevents Ox‐LDL‐Induced Adhesion of Monocytes to Human Endothelial Cells: An Implication in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis,” Molecular Immunology 116 (2019): 73–79, 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zheng W., Pan H., Wei L., Gao F., and Lin X., “Dulaglutide Mitigates Inflammatory Response in Fibroblast‐Like Synoviocytes,” International Immunopharmacology 74 (2019): 105649, 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wu L., Wang Y., Zhan Y., et al., “Dulaglutide, a Long‐Acting GLP‐1 Receptor Agonist, Can Improve Hyperandrogenemia and Ovarian Function in DHEA‐Induced PCOS Rats,” Peptides 145 (2021): 170624, 10.1016/j.peptides.2021.170624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ara C., Dirican A., Unal B., Bay Karabulut A., and Piskin T., “The Effect of Melatonin Against FK506‐Induced Renal Oxidative Stress in Rats,” Surgical Innovation 18 (2011): 34–38, 10.1177/1553350610381088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pawlik M. W., Kwiecien S., Ptak‐Belowska A., et al., “The Renin‐Angiotensin System and Its Vasoactive Metabolite Angiotensin‐(1‐7) in the Mechanism of the Healing of Preexisting Gastric Ulcers. The Involvement of Mas Receptors Nitric Oxide, Prostaglandins and Proinflammatory Cytokines,” Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology: An Official Journal of the Polish Physiological Society 67 (2016): 75–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., and Yagi K., “Assay for Lipid Peroxides in Animal Tissues by Thiobarbituric Acid Reaction,” Analytical Biochemistry 95 (1979): 351–358, 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Beutler E., Duron O., and Kelly B. M., “Improved Method for the Determination of Blood Glutathione,” Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine 61 (1963): 882–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lowry O., Rosebrough N., Farr A. L., and Randall R., “Protein Measurement With the Folin Phenol Reagent,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 193 (1951): 265–275, 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pfaffl M. W., “A New Mathematical Model for Relative Quantification in Real‐Time RT‐PCR,” Nucleic Acids Research 29 (2001): 45e–445e, 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.