Abstract

Objective:

Transcranial focused ultrasound (tFUS) is being explored for neuroscience research and clinical applications due to its ability to affect precise brain regions noninvasively. The ability to target specific brain regions and localize the beam during these procedures is important for these applications to avoid damage and minimize off-target effects. Here, we present a method to combine optical tracking with magnetic resonance (MR) acoustic radiation force imaging to achieve targeting and localizing of the tFUS beam. This combined method provides steering coordinates to target brain regions within a clinically practical time frame.

Methods:

Using an optically tracked hydrophone and bias correction with MR imaging we transformed the FUS focus coordinates into the MR space for targeting and error correction. We validated this method in vivo in 18 macaque FUS studies.

Results:

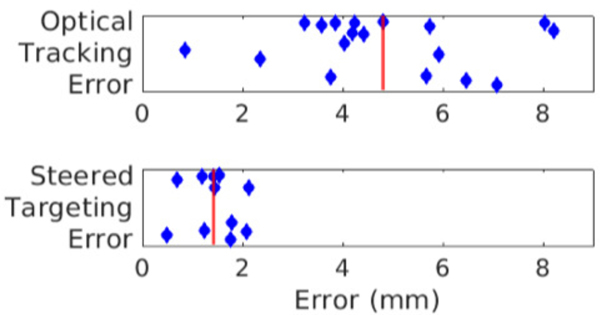

Across these in vivo studies a single localization scan allowed for the average targeting error to be reduced from 4.8 mm to 1.4 mm and for multiple brain regions to be targeted with one transducer position.

Conclusions:

By reducing targeting error and providing the means to target multiple brain regions within a single session with high accuracy this method will allow further study of the effects of tFUS neuromodulation with more advanced approaches such as simultaneous dual or multi-site brain stimulation.

Keywords: image-guidance, magnetic resonance imaging, MR-ARFI, neuronavigation, ultrasound

I. Introduction

Transcranial focused ultrasound (tFUS) is a developing technology which is being used for research and clinical purposes, including reversible neuromodulation [1], targeted drug release [2], [3], blood brain barrier opening (BBBO) [4], [5], and thermal [6] and mechanical ablation [7]. A major benefit of tFUS over other noninvasive brain stimulation methods is the ability to noninvasively target small brain structures on the millimeter scale; however, targeting at the millimeter scale is difficult because the pressure field cannot be directly measured, and a small shift in location can result in displacement from the intended target into a different region of the brain. Targeting and localization of the ultrasound focus in real-time is therefore a fundamentally limiting challenge that must be overcome in tFUS studies to ensure that the intended target is sonicated within a clinically practical time frame.

Targeting the tFUS beam to a location in the head can be achieved using several methods. Generally, image guidance (either pre-acquired or online) is used such that the predicted focus location in the brain can be determined and the transducer can be moved until this predicted location is at the target of interest. This prediction is often based on the free field pressure distribution that does not account for skull induced aberrations which can result in significant beam distortion and spatial shifts [8]. Often MR guidance, with either a preacquired image or an image of the tFUS setup, is used to visualize brain anatomy and the predicted focus location is projected into this image. A number of methods have been described including MR tracking coils [9], [10] and optical tracking [11], [12], [13], [14].

Optical tracking has been widely deployed with single element transducers. A number of recent studies have used optical tracking for neuronavigation of the tFUS transducer for neuromodulation and BBBO [11], [14], [15], [16]. These systems use an infrared stereocamera to measure the position and orientation of a tracker that is attached to a tool and have been in use for a number of years for surgical cases [17]. By associating a geometric transform that converts the position of the point of interest of the tool (e.g. the ultrasound focus location of the transducer), that point of interest can be localized in space [11]. A preacquired image containing a set of fiducials visible in image and physical space can be registered to the tracking system to project the tool into image space [18]. The overall target registration error (TRE) for optically tracked tFUS transducers is between 1–3 mm [11], [12], [14], [19], [20]. A major advantage of optical tracking is the ability to target different brain regions since the transducer can be freely moved. Placing the transducer so that both the focus is at the target and the incident angle on the skull allows for transmission requires different rotations and translations for each target. Optical tracking allows the transducer to be placed near the brain region of interest. Without optical tracking the location of the target would have to be estimated from external head features and the transducer’s focus location would have to be estimated based on the shell of the transducer. The optical tracking information can also assist in MR-ARFI planning by placing the imaging volume at the expected focus location.

Localization of the tFUS beam can be performed using MR imaging methods. MR thermometry [21] can measure small temperature rises induced by the tFUS beam but presents an issue of off-target heating effects (which may not be present in the therapy of interest due to different tFUS pulse designs), neuronal effects from heating, and safety concerns. Small temperature rises are often used for localization in thermal ablation therapies where a larger temperature rise will be used for the therapy but it presents confounds in other applications such as neuromodulation or targeted drug delivery. Neuronal activity has been shown to change with temperature change, and ultrasonic heating has been explicitly shown to inhibit neural activity [22], [23]. Safety concerns in the brain can be minimized by using low pressure levels and ramping up to detect minimal heating but the absorption in the skull is much greater than the brain and there is potential that the skull and surrounding tissue will heat up much more than the target region in the brain. Significant heating should not be present in neuromodulation pulses which have a much lower time-averaged intensity. While a larger aperture transducer can spread the ultrasound energy across more of the skull to reduce skull heating, the increased transducer size will limit possible experimental setups and may not reduce skull heating when targeting cortical regions close to the skull.

Magnetic Resonance Acoustic Radiation Force Imaging (MR-ARFI) can be used to measure micron-scale displacements induced by the acoustic radiation force in the brain [12], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. This often requires intensities which go beyond the FDA limits for diagnostic ultrasound but has been used successfully for beam localization without generating detectable bioeffects [28]. Since ARFI pulses can be spread out in time to lower the duty cycle the spatial peak temporal average intensity of the pulses can be lower than what is needed for thermometry, thereby reducing skull heating.

Here, we describe a method to combine optical tracking of a phased array transducer and MR-ARFI localization to accurately target specific brain targets. Electronic steering informed by beam measurements and optical tracking improves targeting capability in tFUS since the error inherent to optical tracking transformation and skull induced shifts can be overcome by steering the beam. Transducer calibration and steering were measured in a water tank and the full targeting capability is used for ongoing nonhuman primate (NHP; macaque monkeys) fMRI neuromodulation studies with tFUS. Quantification of the total system error before and after steering correction is reported. By combining the steering capability of the phased array with optical tracking and MR-ARFI, we were able to correct for optical tracking and skull-induced error and steer the beam to the intended target.

II. Methods

A. Optical Tracking

An optical tracking camera (NDI Polaris Vicra, Northern Digital Inc., Waterloo, Ontario, CA) was used to track the location of the FUS transducer, and the software application 3D Slicer [29] was used to combine this tracking information with MR images using the OpenIGTLinkIF module [30] and PLUS server [31]. Procedures were based on previous work with a single element transducer [12] and extended to allow electronic steering with a phased array. The trackers used in this study consisted of both commercial and custom-built rigid bodies that used passive tracking spheres (the trackers seen in Fig. 1) (Northern Digital Inc., Waterloo, Ontario, CA). Custom rigid bodies were designed following the camera manufacturer’s guidelines. The goal of the tracking system is to provide the ultrasound coordinates (defined by the transducer geometry) relative to an anatomical image. This requires consideration of four coordinate systems: the MR image coordinates, the tracking camera coordinates, the transducer tracker coordinates, and the ultrasound coordinate system (Fig. 1). The MR coordinate system is defined by the scanner and is included in the image headers which are read into 3D Slicer. The tracking camera coordinates are streamed from the camera which is tracking a reference tracker. Both the phantom and NHP were in fixed positions relative to the reference tracker (Fig. 2A). This reference tracker allowed the camera position to move if needed and maintained a fixed coordinate system between repeated scans which may be acquired with different orientations. The coordinates of the transducer tracker, a tracking tool mounted onto the back of the transducer, was also streamed from the tracking camera and enabled tracking the transducer relative to reference tracker. Finally, the ultrasound coordinate system which has its origin at the geometric focus is given by a fixed offset and rotation from the transducer tracker coordinate system.

Figure 1.

The four coordinate systems of interest in optically tracked FUS. The transducer steering coordinate system can be related to the imaging coordinate system through a series of transformations which allow for accurate targeting of specific brain structures with FUS. An infrared stereocamera (*) is used to locate the transducer in physical space and 3D Slicer (†), Slicer IGT (‡), and the PLUS server (§) are used to connect this camera to a MR viewing environment.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup for optical tracking in vivo. A: A model of the physical set up of the optically tracked NHP neuromodulation experiment. The NHP was placed on a custom table for MR imaging with its head fixed in place using a stereotactic frame built into the NHP table. The FUS transducer was placed over the head on a frame built into the table. The transducer has an optical tracker placed on the back and a water bubble for ultrasound coupling. Fiducials were placed on the ear bars and eye bars of the frame (red spheres). A reference tracker was fixed to the table for optical tracking. MR coils were placed on either side of the head (not pictured). The black dashed region was the approximate MR imaging region in B. B: The 3D Slicer view of the NHP experiment. The optically tracked focus model is shown with the green cylinder. Fiducial markers (red spheres) were localized and registered to the physical marker locations. The individual elements of the transducer were visualized in the MR space.

We can denote a location in a space A as and a transform from coordinate system A to coordinate system B by . The inverse of the transform is the same as a transformation in the opposite direction so that . The four coordinate systems described above can be denoted as the image space from the MRI (I), the physical space recorded by the camera (P), the tracker space (T), and the ultrasound coordinate system space (U). Thus, we can use the following equation to find a coordinate in image space from a coordinate in ultrasound space

| (1) |

Conversely, a coordinate in ultrasound space can be calculated from a coordinate in image space by using the inverse transforms.

Each transform is reported by the camera or calculated through a calibration procedure. was measured from the Polaris Vicra system as a 4-element quaternion and converted to an augmented transformation matrix in the OpenIGTLink module of 3D Slicer and generated for the user. For this study a reference tracker which was fixed relative to the phantom or NHP was used to allow the camera to move during the experiment. Using this additional tracker established the physical coordinate system P relative to the location and orientation of the reference tracker as measured by the camera. was found by registering a set of fiducial markers visualized with MRI to the same markers located in physical space using an NDI tracked stylus. Doughnut shaped markers (MM3002, IZI Medical Products Owings Mills, MD) were used so that the optically tracked stylus could be positioned with the tracked tip of the stylus inside the doughnut. The SlicerIGT Fiducial Registration Wizard extension [32] was used to register these two sets of fiducial locations. had to be calculated for each experiment.

The last transform needed for optical tracking, , connects the transducer tracker and transducer ultrasound coordinate systems for electronic steering. This transform was needed to link the estimated pressure distribution and steering coordinates through the camera space and into MR space. An optically tracked, calibrated hydrophone (HNC 0400, Onda Corp., Sunnyvale CA) experiment was used to measure the location of maximum pressure relative to the transducer tracker at 27 steered locations in the ultrasound space, in a manner similar to previously reported methods [12]. A tracker was placed on a hydrophone holder which could be attached to a three-axis stage. Because needle hydrophone tips are susceptible to damage, a mock hydrophone was used to perform a pivot calibration [33] within the NDI Track software to measure the hydrophone tip location in physical space relative to the hydrophone tracker. The transducer was placed in a water tank with the transducer tracker fixed in place and programmed to sonicate a 3×3×3 grid of points separated by 5 mm each (Fig 3A). The three-axis stage was used to move the hydrophone to find the maximum pressure for each steered location and the location of the hydrophone tip and the transducer tracker were recorded. The set of steered locations in ultrasound space were registered with the hydrophone tip locations relative to the tracker providing the transformation between the tracker on the transducer and FUS coordinate system [34]. Image-based bias correction was used to reduce errors inherent in methods used to generate the initial calculation of , resulting in a final bias-corrected transform of [11], [12].

Figure 3.

Transducer tracker to ultrasound space transformation. A: collection of 27 optically tracked pressure maxima was found for 27 steered locations of the FUS beam along all three axes and a transformation was generated between these data points. A: The optically tracked hydrophone focus locations transformed into ultrasound coordinates and plotted on top of the known steered locations in the ultrasound coordinate system. Points were sonicated in a 3 × 3 × 3 grid with 5 mm step sizes. B: To test the targeting error of the optically tracked hydrophone the transformation between the pressure maxima and the steered locations was generated using 26 of the 27 locations and the 27th point was used to measure the error. This measurement was made for each point. All errors were under 0.6 mm with a mean error shown with the red line of 0.25 mm.

Using (1), we projected a model of the free field focus from the ultrasound space into the MR space to estimate the focus location relative to anatomical MR images. MR-ARFI was used to visualize the focus location to validate this estimate. The translational error between the visualized focus, , and the tracker-predicted focus, , were quantified by placing a marker at the coordinate of the visualized focus, , in image space. This coordinate was transformed into ultrasound space giving, corresponds to the translational error between the tracked and actual focus locations. Electronically steering the transducer focus to steered the beam to , the optical tracking-predicted focus, correcting any error in optical tracking workflow and helping to correct for skull induced focal displacements. Due to fiducial registration and tracking error, some error will change from trial to trial and cannot be eliminated with bias correction alone.

B. Steering to the Target

Once the error vector was known it could be used also to steer to any point within the steering range of the transducer. A marker was placed at a desired target in MR space and transformed into the ultrasound coordinate space. The transformation gave the steering vector needed to go from the initial focus estimate to the new target. By then adding the offset found from the error vector to this point, the tracking error could be corrected so that the ultrasound focus coincided with the desired target. Restated using coordinate notation, there was 1) a target in image space where we desired to place the tFUS focus, 2) the focus location of the first sonication as determined by MR-ARFI, and 3) the estimated focus location from optical tracking . The steering values, for any was determined by including the offset:

| (2) |

C. Compensation for intensity loss during steering

Sonications were performed with a 128-element randomized phased array with a radius of curvature (ROC) of 72 mm and diameter of 103 mm operated at 650 kHz, which has a free field pressure full width at half maximum of 2.2 mm and 9.3 mm in the lateral and axial directions [35]. The transducer output was characterized during a second hydrophone experiment in a water tank. A ‘lateral-axial’ grid for the transducer which extended from 0 to 15 mm from the geometric focus in the lateral direction and −15 to 15 mm in the axial direction in 5 mm steps (the plane is seen in Fig. 4). The peak negative pressure (PNP) at the focus was recorded with a fiber optic hydrophone (FOH, Precision Acoustics, Dorchester, UK), which was cross-calibrated to the calibrated needle hydrophone, for increasing driving values up to a mechanical index (MI) of 4 and a linear fit was performed. The fit parameters for this plane were then interpolated to a 0.1 mm step size. Any point in this steering range was then mapped to this 2D plane to determine the driving value needed to generate a given pressure. Additional information is provided in supplemental material.

Figure 4:

Linear fit coefficients for the transducer and driving system calculated with pressures up to approximately 3.2 MPa. Top: The slope of the fit between pressure in megapascal and driving amplitude. Bottom: the y intercept of the linear fit.

D. Animal handling

All work on NHPs (macaques) was performed with approval of the Vanderbilt University IACUC (protocol number M1900053, approve May 11, 2020). The NHPs were initially sedated with ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg) and atropine sulfate (0.05 mg/kg) and then anesthetized with isoflurane (1.0–1.5%) delivered over oxygen. The NHP head was placed in a stereotactic frame with ear bars, eye bars, and a mouthpiece (Fig. 2). Data was collected in six different macaque monkeys (2 male and 4 female) Two fiducials were located on each of the ear bars and a fiducial was placed on each eye bar. The transducer with a degassed deuterated water-filled coupling bag was placed on top of the shaved head with ultrasound coupling gel applied and the MR coils positioned by the head

E. MR imaging

A T1-weighted image was acquired to localize the fiducials in image space and for target selection and the NHP removed from the magnet. The field of view and MR parameters were adjusted to visualize all fiducials. A target of interest in the brain was selected and a marker was placed at the target in 3D Slicer. The fiducials were used to register the physical space to image space as described above and the transducer was positioned so the optically tracked, predicted focus was near the target. The NHP was returned to the magnet and a second T1-weighted image was acquired to register the initial placement to NHP head position and MR-ARFI performed at the initial placement. In vivo MR imaging was performed on a clinical 3T system (Ingenia Elition X, Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands). For the 3T scanner a pair of surface coils (dStream Flex S, Philips Healthcare, Best, NL) were placed on either side of the phantom or NHP with the transducer positioned above.

To test the ability of our targeting method to correct initial target registration error (TRE), we measured the initial and corrected TRE in 18 nonhuman primate neuromodulation studies. In vivo MR-ARFI was performed with up to 6.5 ms pulses at 5.5–9.0 MPa free field PNP. The pressure in the brain was expected to be significantly attenuated due to the skull. A transmission percentage of 39% was estimated based on previous tests though an ex vivo skull [26] resulting in an estimated PNP of 2.1–3.5 MPa. This corresponded to an in vivo mechanical index (MI) of 2.7–4.3. ARFI sonications used a pulse repetition frequency of 1 Hz with a maximum of 328 sonications per image.

MR-ARFI was performed using a 3D spin echo sequence. The Motion encoding gradients (MEG) were trapezoidal, had durations of 8 ms, had amplitudes of 40 mT/m, and were triggered 2 ms after the sonication start time. The ARFI scans acquired 2 mm × 2 mm × 4 mm voxel size with 6 slices and a TE/TR of 35 ms/500 ms. The ARFI images were reconstructed to a 1.04 mm × 1.04 mm in plane pixel size. A set of two ARFI scans were performed with the first scan using positive MEG polarity and the second scan using negative MEG polarity. FUS was applied on one dynamic of each scan and was turned off for a second dynamic so that a set of four images was obtained, comprising FUS off + MEG, FUS on + MEG, FUS off - MEG, FUS on - MEG. The resulting four images were used to compute displacement maps as described in Ref. [26].

F. In vivo steering

When a clear offset in the tFUS axial direction was noted (the transducer positioned too low or high relative to the target) the initial ARFI was performed at an axially steered location and the initial steering location noted as . The steering coordinate to hit the target of interest was then calculated using (2). In some cases, the axial steering was not performed due to the beam length in this direction. The transducer was then electronically steered to this target coordinate and a MR-ARFI image acquired.

We performed optically tracked targeting for a total of 19 targets across 18 studies in 6 NHPs. One study included two steered locations with the same transducer placement resulting in 18 measures of the error between the optical tracking predicted focus and an initial ARFI scan as calculated by the Euclidian distance. On three days we did not save the target location used for steering and cannot calculate the error between the steered ARFI and the target. Further, on four days we choose not to steer the ARFI as the beam was located at the targeted tissue. This resulted in 11 measures of the error between the steered ARFI and the target of interest.

Following the in vivo studies, transcranial acoustic simulations of the transducer at the initial focus position were performed using the optical tracking information with a custom simulation pipeline [36] using the k-Wave toolbox [37]. These simulations used individual CT data to estimate skull acoustic properties and were perform for 16 of the NHP targets. The centroid of the half maximum pressure region within the focus was identified and compared to the optically tracked predicted focus. This difference will mainly be due to skull induced shifts in the focus position allowing an estimate of how much of our total error is due to the skull.

III. Results

A. Hydrophone Transducer Calibration

The transducer was steered from the geometric focus to a series of lateral and axial points in 5 mm increments and the pressure recorded for a series of input driving amplitudes. As expected, higher driving amplitudes were needed when steering away from the geometric focus. At each point tested, the system could generate sufficient pressure for transcranial displacement detection via MR-ARFI, and this pressure could be matched to the geometric focus. A linear fit was found for each point between driving amplitude and focal pressure of the type . The coefficient maps from this fitting were interpolated to 0.1 mm steps and function written to estimate the driving amplitude needed to generate a pressure at a steered point within this range (Fig. 4). We see a reduction in pressure as we steer away from the geometric focus of the transducer laterally for a giving driving amplitude. When steering the focus farther from the transducer axially we see a reduction in pressure but when steering the focus closer to the transducer axially we first see an increase in pressure, then a decrease in pressure is observed as we continue to steer inwards. A large linear offset was observed due to weak nonlinearity at the higher pressures measured.

B. Ultrasound Coordinate Space Transformations

The hydrophone-based transformation was generated by registering 27 known sonication locations in ultrasound space to the measured focus location of an optically tracked hydrophone. The fiducial registration error between these two datasets was 0.26 mm (Fig. 3A). To test the accuracy of the transform the registration was performed in a leave-one-out fashion in which 26 points were used to generate the transformation and the final point was used to measure the target registration error (TRE). The mean TRE across these 27 points was 0.25 ± 0.14 mm with a maximum error of 0.59 mm (Fig. 3B).

C. Optical Tracking Accuracy

The in vivo MR-ARFI tests found an optical tracking TRE of 4.8 ± 1.9 mm (mean ± standard deviation) after bias correction. A more robust bias estimation may further reduce the error of the system. It is possible that further refinement of the bias in could result in lower optical tracking error but this result is well within our steering envelope.

D. In Vivo Steering

Rigid registration was feasible in all cases, and we achieved a fiducial registration error of 2.5 ± 0.8 mm (range 0.7 to 3.7 mm). In NHP experiments the mean error between the initial ARFI scan and the target of interest was found to be 6.5 ± 2.9 mm which is within our steerable range. After determining the steering coordinate and steering to the target of interest we found an error of 1.4 ± 0.5 mm between the target of interest and the steered ARFI location (Fig. 5). In one of our studies, we targeted multiple areas of interest within the brain based on optical tracking information and a single transducer position and localization scan (Fig. 6). Two brain regions were selected, the insula and thalamus, and the beam was steered to the desired targets and MR-ARFI measured displacement occurred at the selected target points with errors from the center of the ARFI displacement to the targeted point of 1.8 and 0.5 mm.

Figure 5.

Comparison between in vivo optical tracking error and steered target error Summary of in vivo steering, the red line represents the mean error. Top: The error between the selected center of the initial ARFI displacement focus and optical tracking predicted focus (4.8 ± 1.9 mm mean and standard deviation). Bottom: The error between the selected center of the steered ARFI displacement focus and the target of interest. After electronically steering the transducer to the target of interest using information from both optical tracking and the initial ARFI displacement map we are able to place the center of our measured focus within 2 mm of the targeted point (1.4 ± 0.5 mm mean and standard deviation).

Figure 6.

Steering to brain regions of interest. Left: ARFI localization scan targeting the insula. Middle: The MR-ARFI focus location when steering 5 mm towards the transducer. Right: ARFI localization scan targeting the thalamus. Using the optical tracking transformations and the localization scan from the center panel we were able to select points in the insula and thalamus and steer the beam so that the target point was within the ARFI focus.

Simulations resulted in an estimated error between the transcranial simulated focus and the optical tracking-predicted focus of 1.7 ± 1.1 mm (range 0.4 to 4.0 mm). This error can be separated into axial error, along the beam propagation direction, and lateral error perpendicular to the beam propagation direction. The axial simulation error was 1.6 ± 1.1 mm (range 0.1 to 4.0 mm) and the lateral simulation error was 0.6 ± 0.4 mm (range 0.0 to 1.5 mm). These simulations provide an estimate of the skull induced error.

IV. Discussion

Transcranial FUS is being used for a wide range of applications in which accurate and precise targeting is critical. The ideal targeting system would be noninvasive (i.e. not cause unwanted bioeffects), allow for beam correction, and use a measurement of the beam location to ensure accurate targeting. Combining optical tracking with a phased array and MR-ARFI provides a method to place the transducer focus near a desired target, localize the beam, and then steer the beam to correct for any residual error and to sonicate further targets. In this work, we demonstrated a method that allows for rapid and accurate target selection during tFUS procedures while minimizing the number of MR-ARFI localization scans needed, reducing both time and tFUS exposure.

Deep brain targets are of interest for FUS neuromodulation since FUS is uniquely able to target these structures noninvasively with high spatial resolution [38]. Considering the importance of targeting multiple brain regions in other non-invasive neuromodulation methods (e.g. transcranial magnetic stimulation [39]), the ability to efficiently target the FUS beam is of great importance. In this study, the optical tracking information about the transducer’s position within the image space was used to align the transducer near a target of interest in the NHP brain. An MR-ARFI localization scan then determined where the FUS beam was located in vivo and tracking error was determined. This error was then used to correct the steering of the transducer to effectively sonicate the intended brain region as measured by MR-ARFI. By applying the vector between the intended target from optical tracking and the location measured by MR-ARFI, the method described here accomplishes targeting similar to that used during ablation procedures with substantially lower average power and without the need to generate heat.

A. Targeting Considerations

Optical tracking is frequently used for image guidance in tFUS applications and studies designed to assess accuracy report errors in the 2–3 mm range [11], [12], [14]. Prior work has used optical tracking with a single element transducer to target specific brain structures, which does not allow for electronically steered corrections between the estimated focus locations and a measured focus to be applied. In the present study, steering allowed us to overcome error in the initial placement of the transducer which potentially allows for a quicker setup followed by steering while maintaining high accuracy (~1.4 mm in the present study).

The distance between the ARFI-detected focus and intended target after steering is the main error of interest in the present work, which we found to be 1.4 mm. We reported the error between the optically tracked focus and ARFI-detected focus to be 4.8 ± 1.9 mm prior to steering, which arises from uncertainties each transform in Fig. 1 and skull-induced aberrations. We performed a bias correction (Fig. S1, as in [11], [12]) but residual bias may still exist. The tracker-to-physical transform error will depend on the accuracy of the tracking camera (NDI Polaris, Northern Digital Inc., Waterloo, Ontario, CA), which has a vendor-reported accuracy of 0.25 mm and has been reported as having 0.93 mm error when compared to a robotic positioning system with similar custom trackers [13]. The error in the physical-to-image space transform is likely the largest source of error in our setup and results from fiducial localization error [18]. The expected value of the fiducial registration error is proportional to the expected value of the target registration error but the two quantities are not correlated in a single experiment [40]. Finally, the skull-induced aberration will depend on the geometry of the transducer and skull as well as the tissue properties of the skull. Using simulations, we found 1.7 mm of error with much of this error in the axial direction.

Other methods of targeting can also be used. MR tracking coils are a bright signal source wrapped in a coil which can be easily located in MR space. By placing these on the transducer in fixed locations, the position of the tracking coils can be used to measure where the transducer is located within the MR space. The focus of the transducer can then be linked with these trackers to predict where the focus will be in a new experiment [9]. This type of system has been deployed for a human breast ablation system with an error between the predicted focus and center of mass of heating of 2.9 mm in phantoms and 6.1 mm in vivo [10]. A similar method has been reported using MR visible tracking spheres in image space to localize the transducer and predict the focus location. In phantom tests the accuracy was 0.9 mm with thermometry and 1.3 mm with MR-ARFI and a transcranial MR-ARFI test found an accuracy of 7.5 mm [41]. The method presented here with MR-ARFI corrected, optically tracked steering was able to produce a comparable in vivo error of 4.8 mm before steering and, at the expense of time outside of the magnet, able to be prospectively targeted to the region of interest before the initial sonications. The use of ARFI based steering helps to overcome the targeting error from optical tracking.

B. Target Selection and Safety

Recent studies with FUS neuromodulation have targeted multiple regions of the brain to better understand networks and to act as controls so that the effects of stimulations can be better understood [42], [43]. Accurate electronic steering of an array transducer allowed for multiple regions to be targeted without having to adjust the transducer’s physical position. With electronic steering, the focus of the transducer could be rapidly moved between targets in millisecond time scales which is much faster than the hemodynamic response measured by fMRI [44]. The FUS system used in this study is also capable of sonicating multiple targets at once [45]. The ability to target separated brain regions with a single experimental setup will allow for new hypotheses to be tested.

The method described here helps reduce the number of sonications required to steer the focus to the intended location—an important goal for translating high precision transcranial ultrasound. Safety of FUS pulses in the brain is currently being studied, and there does not yet exist a well-defined standard for ultrasound pulses used in ARFI. FDA guidelines on safety requirements for ultrasound imaging devices were developed based on assessments of ultrasound devices deployed in 1976 and for short duration pulses that are many times shorter than those used for ARFI [46], [47]. While diagnostic imaging metrics and limitations were not designed for transcranial ARFI pulses, they still provide a useful means to quantify the pulse. To generate a detectable displacement of approximately 1.5 μm, we used a pulse with an estimated PNP at the transcranial focus of 3.0 MPa. This corresponds to an MI of 3.7 which exceeds the diagnostic imaging guideline of 1.9 and is above the guidelines for maximum Isppa (300.6 W/cm2). Ispta (2555.1 mW/cm2) was estimated to be above the FDA guidelines for diagnostic imaging (190 W/cm2 and 720 mW/cm2 respectively). Both Isppa and Ispta were calculated by assuming a sine wave with 3.0 MPa amplitude and a pulse duration and PRF based on the pulsing parameters. Because much of the transmitted sound is scattered and absorbed in the skull, the peak negative pressure experienced by neural tissue is much lower than if the skull were not present. Thermal safety is also of concern with repeated FUS pulses. Studies have shown through simulation and MR thermometry that MR-ARFI can localize the beam while keeping thermal deposition below 0.5 °C in the brain [26], [27]. MR-ARFI is capable of sensing displacements as low as 100 nanometers in phantoms [25], [48], but the sensitivity in in vivo imaging is often lower due to the inhomogeneous media, motion, and other factors. Previous studies of neuromodulation and ARFI FUS pulses have not found any histological evidence of damage at higher MI than was used in this study [28] but further study is needed to ensure damage or secondary effects are not occurring.

C. MR-ARFI Considerations

The size of MR-ARFI voxels achievable presents a limit in the precision of localizing the focus with ARFI that is comparable to that found with thermometry. Our MR-ARFI images were collected using a 2-mm in-plane resolution and slice thickness of 3 mm with a 1-mm slice gap, while our transducer produces an ellipsoidal focus with full-width at half maximum dimensions of 2.2 mm × 2.2 mm × 9.3 mm. The resultant displaced region is typically larger than the FWHM because the displacement is a function of the tissue properties (e.g. absorption, tissue elasticity) and time averaged over the gradient duration of 8.5 msec [49]. MR thermometry images from clinical Insightec studies use orthogonal single slice imaging with a size of 1.1 mm × 1.1 mm × 3 mm [50] to localize a beam with a lateral FWHM estimated to be 1.4 mm [51]. MR-ARFI is therefore similarly spatially undersampled compared to clinically approved thermometry.

Additional rounds of MR-ARFI based steering corrections could be used to further reduce the total error between the target of the center of the displacement region. The average error of 1.4 mm after a single round of MR-ARFI confirmed sufficient overlap between the ARFI-detected focus and target brain region for our study. In general, we sought to minimize the number of ARF pulses, because ARF pulses may modulate the brain and the peak negative pressure exceeds limits for diagnostic ultrasound. It may be feasible to improve targeting accuracy by performing multiple rounds of localization as is done in ablation studies where in one study an average of 4.7 localization sonications were performed until a good effect was observed [52].

Accuracy will also depend on the size of the focus and the size and shape of the brain region of interest. Because our error is measured from a point target as opposed to a whole brain region we expect that a large portion of our beam is expected to fall into the targeted region. Observing what brain regions overlap with the displaced tissue or a region around the MR-ARFI defined focus may provide better measures of what brain regions are being affected by the tFUS rather than looking only at the Euclidian targeting distance to a single point [53].

In this work we did not attempt aberration correction. The repeated collection of MR-ARFI displacement information has been examined to correct for aberrations due to the skull [54], [55], [56], [57]. Optical tracking information could potentially be used for aberration correction without the need to perform ARFI because it provides an estimate of the transducer element location relative to the skull which is needed to correct for skull induced aberration by calculating the phase offset induced by the skull [8]. However, registration errors innate to optical tracking would likely reduce the efficacy of aberration correction since the calculated phase corrections would be based on a geometry that included optical tracking errors. We have explored refining the transducer location estimate by using the vector between the optically tracked predicted focus and the location of the beam after a single ARFI [36]. The improved estimate of the transducer location may improve aberration correction. The displacement information may also be useful for estimating in vivo pressure and tissue effects [58], [59].

V. Conclusion

In this work we detail a method to target and sonicate multiple brain regions of interest with transcranial FUS within one session. By improving the targeting of FUS we can perform better basic research into FUS neuromodulation with better confidence of what brain regions are being sonicated. This improved targeting can also help with clinical applications of FUS since all applications require accurate targeting. The presented methods allow for quick, accurate targeting while minimizing the number of localizations scans needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants U18EB029351 and T32EB001628.”

Contributor Information

M. Anthony Phipps, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science and the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Nashville, TN, USA.

Thomas J. Manuel, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science and the Vanderbilt University Department of Biomedical Engineering, Nashville, TN, USA.

Michelle K. Sigona, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science and the Vanderbilt University Department of Biomedical Engineering, Nashville, TN, USA.

Huiwen Luo, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science and the Vanderbilt University Department of Biomedical Engineering, Nashville, TN, USA.

Pai-Feng Yang, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science and the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Nashville, TN, USA.

Allen Newton, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science and the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Nashville, TN, USA.

Li Min Chen, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science and the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Nashville, TN, USA.

William Grissom, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science, the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, and Vanderbilt University Department of Biomedical Engineering, Nashville, TN, USA.

Charles F. Caskey, Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science, the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, and Vanderbilt University Department of Biomedical Engineering, Nashville, TN, USA.

References

- [1].Darmani G. et al. , ‘Non-invasive transcranial ultrasound stimulation for neuromodulation’, Clinical Neurophysiology, vol. 135. Elsevier, pp. 51–73, Mar. 01, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2021.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Airan RD et al. , ‘Noninvasive Targeted Transcranial Neuromodulation via Focused Ultrasound Gated Drug Release from Nanoemulsions’, Nano Letters, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 652–659, 2017, doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b03517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang JB et al. , ‘Noninvasive Ultrasonic Drug Uncaging Maps Whole-Brain Functional Networks’, Neuron, vol. 100, no. 3, pp. 728–738.e7, Nov. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Meng Y. et al. , ‘Safety and efficacy of focused ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier opening, an integrative review of animal and human studies’, Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 309. Elsevier B.V., pp. 25–36, Sep. 10, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Roberts JW et al. , ‘Focused ultrasound for the treatment of glioblastoma’, Journal of Neuro-Oncology, vol. 157, no. 2. Springer, pp. 237–247, Apr. 01, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s11060-022-03974-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Elias WJ et al. , ‘A Randomized Trial of Focused Ultrasound Thalamotomy for Essential Tremor’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 375, no. 8, pp. 730–739, 2016, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Xu Z. et al. , ‘Histotripsy: the first noninvasive, non-ionizing, non-thermal ablation technique based on ultrasound’, International Journal of Hyperthermia, vol. 38, no. 1. Taylor & Francis, pp. 561–575, 2021. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2021.1905189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kyriakou A. et al. , ‘A review of numerical and experimental compensation techniques for skull-induced phase aberrations in transcranial focused ultrasound’, International Journal of Hyperthermia, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 36–46, Dec. 2014, doi: 10.3109/02656736.2013.861519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Svedin BT et al. , ‘Focal point determination in magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound using tracking coils’, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 77, no. 6, pp. 2424–2430, 2017, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Payne A. et al. , ‘A Breast-Specific MR Guided Focused Ultrasound Platform and Treatment Protocol: First-in-Human Technical Evaluation’, IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 893–904, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2020.3016206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kim H. et al. , ‘Image-guided navigation of single-element focused ultrasound transducer’, International Journal of Imaging Systems and Technology, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 177–184, 2012, doi: 10.1002/ima.22020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chaplin V. et al. , ‘On the accuracy of optically tracked transducers for image-guided transcranial ultrasound’, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 1317–1327, 2019, doi: 10.1007/s11548-019-01988-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Preiswerk F. et al. , ‘Open-source neuronavigation for multimodal non-invasive brain stimulation using 3D Slicer’, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wu SY et al. , ‘Efficient blood-brain barrier opening in primates with neuronavigation-guided ultrasound and real-time acoustic mapping’, Scientific Reports, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 7978, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25904-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee W. et al. , ‘Image-Guided Focused Ultrasound-Mediated Regional Brain Stimulation in Sheep’, Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 459–470, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Legon W. et al. , ‘Transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation of the human primary motor cortex’, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 10007, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28320-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Khadem R. et al. , ‘Comparative Tracking Error Analysis of Five Different Optical Tracking Systems’, Computer Aided Surgery, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 98–107, Jan. 2000, doi: 10.3109/10929080009148876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Labadie RF et al. , ‘Image-guided surgery: What is the accuracy?’, Current Opinion in Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, vol. 13, no. 1. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, pp. 27–31, Feb. 2005. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wei KC et al. , ‘Neuronavigation-Guided Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening: A Preliminary Study in Swine’, AJNR: American Journal of Neuroradiology, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 115, Jan. 2013, doi: 10.3174/AJNR.A3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xu L. et al. , ‘ Characterization of the Targeting Accuracy of a Neuronavigation-guided Transcranial FUS system in vitro, in vivo, and in silico ‘, IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, pp. 1–11, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2022.3221887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rieke V. and Pauly KB, ‘MR thermometry’, Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 376–390, 2008, doi: 10.1002/jmri.21265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang H. et al. , ‘Brain temperature and its fundamental properties: A review for clinical neuroscientists’, Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 8, no. SEP, pp. 1–17, 2014, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Darrow DP et al. , ‘Reversible neuroinhibition by focused ultrasound is mediated by a thermal mechanism’, Brain Stimulation, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1439–1447, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.1016/J.BRS.2019.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sarvazyan AP et al. , ‘Shear wave elasticity imaging: A new ultrasonic technology of medical diagnostics’, Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology, vol. 24, no. 9, pp. 1419–1435, Dec. 1998, doi: 10.1016/S0301-5629(98)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McDannold N. and Maier SE, ‘Magnetic resonance acoustic radiation force imaging’, Medical Physics, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. 3748–3758, 2008, doi: 10.1118/1.2956712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Phipps MA et al. , ‘Considerations for ultrasound exposure during transcranial MR acoustic radiation force imaging’, Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52443-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ozenne V. et al. , ‘MRI monitoring of temperature and displacement for transcranial focus ultrasound applications’, NeuroImage, vol. 204, p. 116236, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gaur P. et al. , ‘Histologic safety of transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation and magnetic resonance acoustic radiation force imaging in rhesus macaques and sheep’, Brain Stimulation, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 804–814, May 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fedorov A. et al. , ‘3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network’, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 1323–1341, Nov. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tokuda J. et al. , ‘OpenIGTLink: An open network protocol for image-guided therapy environment’, International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 423–434, Dec. 2009, doi: 10.1002/rcs.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lasso A. et al. , ‘PLUS: Open-source toolkit for ultrasound-guided intervention systems’, IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 61, no. 10, pp. 2527–2537, Oct. 2014, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2322864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ungi T. et al. , ‘Open-source platforms for navigated image-guided interventions’, Medical Image Analysis, vol. 33. Elsevier B.V., pp. 181–186, Oct. 01, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yaniv Z, ‘Which pivot calibration?’, in Medical Imaging 2015: Image-Guided Procedures, Robotic Interventions, and Modeling, R JW III and Yaniv ZR, Eds., SPIE, 2015, p. 941527. doi: 10.1117/12.2081348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fitzpatrick JM et al. , ‘Image Registration’, in Handbook of Medical Imaging, Volume 2, Medical Image Processing and Analysis, Sonka M. and Fitzpatrick JM, Eds., Bellingham, WA: SPIE Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chaplin V. et al. , ‘A random phased-array for MR-guided transcranial ultrasound neuromodulation in non-human primates’, Physics in Medicine and Biology, vol. 63, no. 10, Apr. 2018, doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aabeff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sigona MK et al. , ‘Generating Patient-Specific Acoustic Simulations for Transcranial Focused Ultrasound Procedures based on Optical Tracking Information’, IEEE Open Journal of Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, pp. 1–1, 2023, doi: 10.1109/OJUFFC.2023.3318560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Treeby BE and Cox BT, ‘k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields’, Journal of Biomedical Optics, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 021314, 2010, doi: 10.1117/1.3360308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Di Biase L. et al. , ‘Transcranial Focused Ultrasound (tFUS) and Transcranial Unfocused Ultrasound (tUS) neuromodulation: From theoretical principles to stimulation practices’, Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 10, no. JUN, p. 549, 2019, doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Trevizol AP et al. , ‘Unilateral and bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant late-life depression’, International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 822–827, Jun. 2019, doi: 10.1002/GPS.5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fitzpatrick JM, ‘Fiducial registration error and target registration error are uncorrelated’, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.813601, vol. 7261, no. 13, pp. 21–32, Mar. 2009, doi: 10.1117/12.813601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Qiao Y. et al. , ‘MARFit: An Integrated Software for Real-Time MR Guided Focused Ultrasound Neuromodulation System’, IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 30, pp. 264–273, 2022, doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2022.3146286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Folloni D. et al. , ‘Manipulation of Subcortical and Deep Cortical Activity in the Primate Brain Using Transcranial Focused Ultrasound Stimulation’, Neuron, vol. 101, no. 6, pp. 1109–1116.e5, Mar. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Verhagen L. et al. , ‘Offline impact of transcranial focused ultrasound on cortical activation in primates’, eLife, vol. 8, Feb. 2019, doi: 10.7554/eLife.40541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Miezin FM et al. , ‘Characterizing the hemodynamic response: Effects of presentation rate, sampling procedure, and the possibility of ordering brain activity based on relative timing’, NeuroImage, vol. 11, no. 6 I, pp. 735–759, 2000, doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Singh A. et al. , ‘Improving the heating efficiency of high intensity focused ultrasound ablation through the use of phase change nanodroplets and multifocus sonication’, Physics in Medicine and Biology, vol. 65, no. 20, p. 205004, Oct. 2020, doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab9559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].FDA, ‘Information for Manufacturers Seeking Marketing Clearance of Diagnostic Ultrasound Systems and Transducers’. pp. 1–64, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Miller DL, ‘Safety Assurance in Obstetrical Ultrasound’, Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 156–164, Apr. 2008, doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen J. et al. , ‘Optimization of encoding gradients for MR-ARFI’, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 63, no. 4, pp. 1050–1058, 2010, doi: 10.1002/mrm.22299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sarvazyan AP et al. , ‘Acoustic Radiation Force: A Review of Four Mechanisms for Biomedical Applications’, IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, vol. 68, no. 11, pp. 3261–3269, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2021.3112505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Seasons GM et al. , ‘Predicting high-intensity focused ultrasound thalamotomy lesions using 2D magnetic resonance thermometry and 3D Gaussian modeling’, Medical Physics, vol. 46, no. 12, pp. 5722–5732, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1002/MP.13868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].O’Neill BE et al. , ‘Estimation of thermal dose from MR thermometry during application of nonablative pulsed high intensity focused ultrasound’, Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 1169–1178, May 2012, doi: 10.1002/JMRI.23526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Feltrin FS et al. , ‘Focused ultrasound using a novel targeting method four-tract tractography for magnetic resonance–guided high-intensity focused ultrasound targeting’, Brain Communications, vol. 4, no. 6, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.1093/BRAINCOMMS/FCAC273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mishra A. et al. , ‘Disrupting nociceptive information processing flow through transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation of thalamic nuclei’, Brain Stimulation, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 1430–1444, Sep. 2023, doi: 10.1016/J.BRS.2023.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kaye EA et al. , ‘Application of Zernike polynomials towards accelerated adaptive focusing of transcranial high intensity focused ultrasound’, Medical Physics, vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 6254–6263, Sep. 2012, doi: 10.1118/1.4752085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hertzberg Y. et al. , ‘Ultrasound focusing using magnetic resonance acoustic radiation force imaging: Application to ultrasound transcranial therapy’, Medical Physics, vol. 37, no. 6Part1, pp. 2934–2942, May 2010, doi: 10.1118/1.3395553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Marsac L. et al. , ‘MR-guided adaptive focusing of therapeutic ultrasound beams in the human head’, Medical Physics, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 1141–1149, Feb. 2012, doi: 10.1118/1.3678988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Liu N. et al. , ‘Random calibration for accelerating MR-ARFI guided ultrasonic focusing in transcranial therapy’, Physics in Medicine and Biology, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 1069–1085, 2015, doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/3/1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Li N. et al. , ‘Improving in situ acoustic intensity estimates using MR acoustic radiation force imaging in combination with multifrequency MR elastography’, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 88, no. 4, pp. 1673–1689, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1002/MRM.29309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mohammadjavadi M. et al. , ‘Transcranial ultrasound neuromodulation of the thalamic visual pathway in a large animal model and the dose-response relationship with MR-ARFI’, Scientific Reports 2022 12:1, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.