Abstract

Phloem, an exceptional plant vascular tissue, facilitates the transport of photoassimilates, RNAs, and other signaling substances from the leaves to the roots throughout the plant. Among the specialized phloem cells are the conductive sieve elements (SEs), which are unique in that they remain alive despite lacking several cell organelles, including the nucleus, plastids, and most mitochondria. These SEs contain a specific proteinaceous structure composed of phloem-specific proteins (P-proteins), whose function is not yet fully understood. Various P-proteins have been characterized in broad range of model species, including Arabidopsis thaliana, and reported in Fabaceae and Cucurbitaceae plants. To date, only one P-protein has been identified in the model tree species Populus trichocarpa. Given the presence of multiple P-protein encoding genes across numerous plant species, we hypothesized the existence of multiple such genes in the Populus genome. Our genomic analysis uncovered 12 genes being potential orthologues to one of A. thaliana P-protein – SEOR (sieve element occlusion-related) genes, which may contribute to the proteinaceous structures observed in differentiating sieve elements. Our transcriptomic and proteomic analyses confirmed the expression of at least seven of these genes, indicating that the protein structure visible in mature sieve elements in P. trichocarpa may be heterogeneous.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-06439-4.

Keywords: Phloem, Sieve element, P-protein, SEO, SEOR, Populus trichocarpa

Background

One of the principal adaptations plants have developed during their evolution to thrive in terrestrial environments is the capability to transport assimilates and signaling molecules throughout their structure, a function primarily facilitated by phloem tissue. This component of the plant vascular system is engaged in the transport of photoassimilates, RNAs, and other signaling molecules from leaves to all parts of the plant [1]. Phloem is characterized by a high degree of cell specialization and heterogeneity, attributed to the fact that not all phloem cells serve a conductive function. This tissue includes conductive sieve elements (SEs), companion cells, phloem parenchyma involved in radial transport and storage, and dead fiber cells that provide mechanical support. Sieve elements are distinctive cell types that lack certain organelles such as the nucleus, plastids, and most mitochondria during differentiation, yet they remain viable [2, 3].

Most angiosperm plants generate phloem-specific proteins (P-proteins) in their SE precursor cells [1]. The initial observation of sieve element-specific protein structures, termed “slime” by Hartig in 1854, noted a specific accumulation of material on the sieve plates or across the sieve element lumen [4]. Subsequent studies confirmed the proteinaceous nature of this slime [5], leading to these proteins being designated as "P-protein" [6]. Despite investigations into P-proteins since the 1960s, their functions remain largely speculative. What is known now is these proteins recognition as aggregates detectable in angiosperm sieve elements [7] and exhibition a variety of structures across different plant species and developmental stages [8, 9]. Their potential roles have long been hypothesized [10], predominantly as mechanisms for sieve element occlusion [11–13] or as physical barriers against phloem-feeding insects or microbes [10, 13]. These hypothetical functions have been comprehensively reviewed by Noll et al. [14]. To date, the specific functions of P-proteins remain elusive, with the notable exception of forisomes in Fabaceae species, which have been demonstrated to participate in responses to certain phloem-feeding aphids [15].

These proteins are known to assemble into dense bodies during SE differentiation, dispersing in mature phloem conductive cells [16]. However, certain P-protein bodies, identified as non-dispersive P-protein bodies (NPBs), were initially only documented in dicot plants [17] before being detected in the monocot family of Zingiberaceae [18]. Intriguingly, NPBs were first thought to be degraded nuclear remnants [19, 20] until ultrastructural studies confirmed their protein aggregation nature [21, 22]. P-protein synthesis commences prior to sieve element enucleation [23], resulting in electron-dense structures initially described as granular, fibrillar, or tubular [6, 24, 25]. These structures have been observed within the same cell, suggesting that they represent various stages of the P-protein differentiation process [8]. During sieve element maturation, some P-proteins form into large bodies, which become smaller and relocate to the cell periphery during selective autophagy events in SE development, taking their position in the mature SE [26]. Due to their location and potential functions, these proteins have been named SEO (sieve element occlusion) proteins.

Certain plant families exhibit distinct P-protein characteristics, notably the Cucurbitaceae, whose dispersive P-proteins undergo reversible, oxidative cross-linkage to form high molecular weight polymers [10]. In cucurbits, a specific phloem filament protein, PP1, is not a homolog of sieve element occlusion proteins (SEOs) [27]. This uniqueness suggests that the filaments formed by PP1 are specific to the large sieve elements of cucurbits [28]. Another well-studied group in terms of P-proteins is the Fabaceae, which feature unusual phloem protein structures called forisomes [29]. These are non-dispersive P-protein bodies that can transition into dispersed states in response to changes in local calcium concentrations [29, 30]. In Medicago truncatula, for example, forisomes consist of at least three SEO proteins [27], while a broader range of SEO family genes has been identified in this species [31]. The number of SEO encoding genes varies significantly across Fabaceae species, ranging from a single gene in Vicia faba and Pisum sativum to 26 in Glycine max [32]. A. thaliana is another model species with extensively studied phloem-specific proteins. Initially, two SEO-related (SEOR) genes, At3g01680 and At3g01670, were identified, encoding AtSEOR1 and AtSEOR2 proteins respectively [33], along with a third gene, At1g67790, which was initially considered a non-expressed pseudogene [32]. Recent studies employing single-cell RNA-sequencing techniques have revealed that this gene, encoding the AtSEORc protein, is actively transcribed in phloem cells [34]. Furthermore, the expression of all Arabidopsis SEOR genes has been specifically associated with the final stage of phloem differentiation [35].

Given the utility of P-proteins as markers for investigating long-distance molecular transport in plants, their study in tree model species is particularly intriguing. In Malus domestica, initially, only one SEOR encoding gene was identified [32]. However, research in another tree species, Populus trichocarpa, has shown the presence of NPB bodies in its sieve elements, which, unlike forisomes, do not respond to Ca2+ ions or cell wall wounding [36]. This remains the only study of SEOR proteins in P. trichocarpa thus far, revealing just one protein potentially orthologous to Arabidopsis AtSEOR1 [36]. Based on extensive genomic studies of Populus and other model plants, we investigated SEOR proteins in P. trichocarpa. Our genomic analysis uncovered 12 genes in the P. trichocarpa genome, potentially orthologous to three A. thaliana SEOR-encoding genes. Subsequent ultrastructural, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses identified NPBs in P. trichocarpa sieve elements and delineated SEOR proteins with yet unknown function.

To standardize the nomenclature of phloem-specific proteins being used in this work, we define “P-protein” as a term for all phloem-specific proteins, defined historically and recently as elements of sieve element-specific protein bodies. SEO refers to proteins found in Fabaceae species that have been shown to have an occlusion function in sieve elements, while SEOR denotes proteins encoded by orthologues of SEO genes in other plant species, for which no occlusive function has been demonstrated so far.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

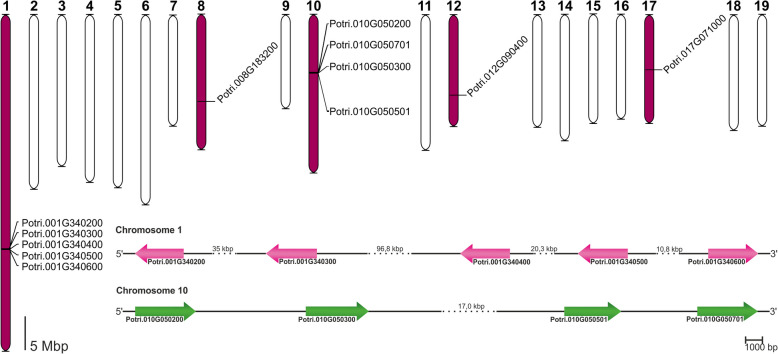

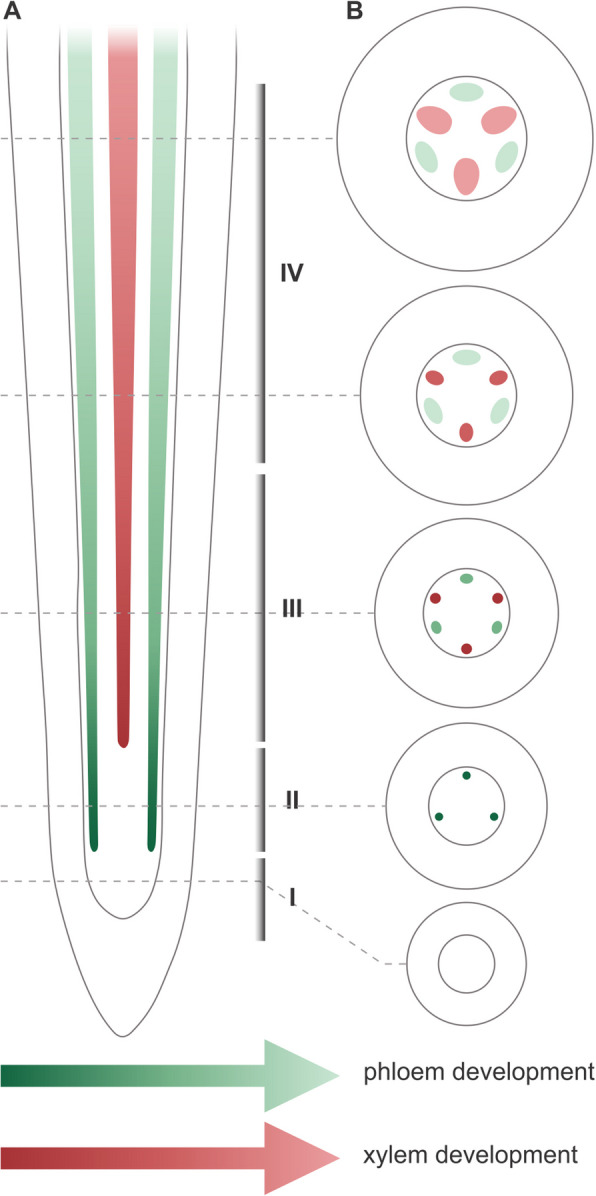

Experiments were conducted using black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa Torr. & A. Gray ex Hook.) pioneer roots from plants germinated from seeds supplied by a seed bank. The initial cultivation phase occurred in a Conviron GR96 plant growth chamber, maintaining a 16/8-h day/night photoperiod at temperatures of 18/14 °C. Three-month-old plants were transferred to the experimental field site at the Institute of Dendrology, Polish Academy of Sciences in Kórnik, Poland (52°14′39.3′′N, 17°06′10.6′′E). Here, plants were grown in a semi-open foil tunnel greenhouse, with the plants positioned in rhizotrons arranged vertically within an underground chamber as previously described [37]. The pioneer roots were identified according to the methods outlined by Bagniewska-Zadworna et al. [38]. Fragments were subsequently sectioned corresponding to the primary vascular tissue developmental stages: I – meristematic tissue, II – phloem precursors, III – maturing phloem and xylem precursors, IV – mature phloem and maturing xylem (Fig. 1), according to Bagniewska-Zadworna et al. [38–40]. Additionally, stems (Sects. 0–2 cm from the apical meristem) and leaves (sections around 2–3 cm2 containing the midrib) were harvested for RT-qPCR analysis.

Fig. 1.

Illustrative overview of the primary vascular tissue developmental stages in the pioneer root of P. trichocarpa: A – tangenial section; B transverse sections. The phloem and xylem are represented in a gradient of green and red shades respectively, and not drawn to scale. I – meristematic tissue, II – phloem precursors, III – maturing phloem and xylem precursors, IV – mature phloem and maturing xylem

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Root fragments measuring 5 mm were immediately fixed in a freshly prepared solution containing 2% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 2% (v/v) formaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylic buffer (pH 7.3; Polysciences), followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C. Subsequent steps were adapted from methods optimized for phloem tissue [41], with minor modifications suitable for pioneer roots of P. trichocarpa. Samples were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylic buffer (pH 7.3; Polysciences) for 2 h, then counterstained with 2% uranyl acetate in 5% ethanol for 1 h in darkness at room temperature. Following dehydration in a graded ethanol series (10–100%, v/v), the samples were infiltrated with an ethanol series (3:1, 1:1, 1:3), culminating in 100% acetone, then embedded in Spurr's low-viscosity resin (Polysciences) through a series of acetone (1:1) mixtures and subsequently pure resin. Polymerization occurred at 60 °C for 72 h. Ultrathin sections were cut using an ultramicrotome EM UC6 (Leica-Reichert) with a diamond knife at a thickness of 0.1 μm, placed on formvar-coated copper grids, stained with 2% lead citrate and 2% uranyl acetate, and examined using an HT7700 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at 100 kV. At least five sections from different plants were analyzed.

SEOR gene identification

Genes encoding SEOR proteins were identified through genome comparative analysis using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) with default parameters for protein–protein BLAST [42]. Peptide sequences from well-characterized SEOR genes in A. thaliana served as queries to search for potential orthologues in the P. trichocarpa genome version v4.1, available in Phytozome 13, The Plant Genomic Resource [43, 44].

Genome distribution and conserved motif detection

Gene locations were mapped using the MAP tool to illustrate the distribution of identified P. trichocarpa SEOR genes across its genome. Conserved motifs among SEOR proteins were identified using the MEME tool (Multiple Em Motif Elicitation Version 5.5.5;) [45]. Detected motifs were further analyzed with SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool) [46] to determine if they correspond to any known protein domains listed in the Pfam database.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees were constructed for all identified genes from P. trichocarpa, their orthologues in A. thaliana, and other SEO/SEOR proteins known from several plant model species: Medicago truncatula, Vicia faba, Pisum sativum, Cucumis sativus, and Malus domestica. This analysis was based on encoded protein amino acid sequences using MEGA 11 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11) [47]. The maximum likelihood method was employed, utilizing the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) substitution model and the bootstrap method with 1000 replications to test phylogeny.

Analysis of gene expression by single-nucleus RNA-sequencing

Single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-Seq) was conducted on nuclei isolated from pioneer root fragments corresponding to the primary stages of vascular tissue development (Fig. 1, stages I-IV). The method for nuclei isolation was adapted from Dorrity et al. [48] with minor modifications for Populus roots. Isolated nuclei were stained with DAPI (SIGMA; excited with a 405 nm laser) and sorted using a BD FACSAria™ Fusion flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, USA) equipped with a 100 µm nozzle. The sorting protocol involved removing debris and selecting single nuclei based on a positive DAPI signal. Post-sorting, nuclei were concentrated by centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min and resuspended in 1 × PBS containing 0.04% BSA. Nuclei quality was assessed using an ImageStreamX MkII imaging flow cytometer (Cytek Biosciences, USA; Additional file, Fig. S1).

Single-nucleus transcriptomic libraries were prepared with the Chromium Controller and the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kit (10 × Genomics, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Approximately 20,000 nuclei were combined with reverse transcription reagents and processed on the Chromium Next GEM Chip G to produce gel beads in emulsion (GEMs). This process released primers from the gel beads, facilitating the synthesis of barcoded cDNA from captured mRNA.

After incubation, GEMs were pooled, and the cDNA was purified using magnetic beads. The barcoded cDNA underwent PCR amplification, followed by enzymatic fragmentation and size selection. Illumina P5 and P7 adaptors, i7 and i5 sample indexes, and the TruSeq Read 2 sequencing primer site were added through end repair, A-tailing, adaptor ligation, and PCR, resulting in the completion of the final libraries. Sequencing was conducted on the NovaSeqX 10B platform (Illumina) by Macrogen Europe (Netherlands).

snRNA-seq data analysis

Raw sequencing data were processed using Cell Ranger v7.1.0 (10 × Genomics). A reference genome for P. trichocarpa (black cottonwood; isolate Nisqually-1) was prepared using the 'cellranger mkref' command, incorporating the P. trichocarpa v4.1 genome assembly and gene annotations from Phytozome v13 (BioProject PRJNA10772, Assembly GCA_000002775.4) [44, 49, 50]. The 'cellranger count' command was executed with default settings using STAR v2.7.2a [51] as the aligner. The resulting gene-nucleus matrices were analyzed using the Seurat package v5.1.0 [52] in R v4.2.1. Low-quality nuclei were excluded based on the following criteria: gene counts > 200, UMIs < 20,000, mitochondrial content < 5%, and log10(gene count per UMI) > 0.8. Only genes detected in at least five nuclei were included. Samples were combined using the 'merge' function, and each was normalized separately using the 'sctransform v2' function [53] implemented in Seurat. Dimensionality reduction was conducted on 3,000 highly variable features. The 'FindNeighbors' function was applied with 51 principal components for the full datasets, and clustering was performed using the Louvain algorithm. Nucleus clusters were visualized with UMAP and annotated based on the expression of known marker genes. The 'NormalizeData' function was used for differential gene expression analysis and plotting within the Seurat RNA assay. Gene markers for each nucleus cluster were identified using the 'FindMarkers' function, with differentially expressed genes defined by an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05, pct.1 > 0.5, and pct.2 < 0.3.

Analysis of gene expression by RT-qPCR

RNA isolation was conducted using the Ribospin™ Plant kit (GeneAll Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Seoul, South Korea) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA synthesis followed, utilizing the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). A 1:10 dilution of cDNA was used for the PCR reactions. The RT-qPCR (Reverse Transcriptase quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction) was performed with the SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems) in a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The PCR program included an initial denaturation by hot start at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of a three-step thermal cycling protocol: denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 60 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 15 s. Actin and UBQ (ubiquitin) were selected as housekeeping genes due to their consistent expression across all cells and time points. Multiple primer pairs, specific to one or more SEOR encoding genes, were employed (Tab. 1), as some genes are highly similar, and making gene-specific primer design was impossible. Data analysis was conducted using the 2−ΔΔCt method [54]. Each analysis included three technical replicates for each of the three biological replicates across four experimental variants. Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistica 10 software (StatSoft Poland Inc., Tulsa, OH, USA) (Additional file, Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Primers used in RT-qPCR analysis

| Name | Gene | Primer F 5′ ➝ 3’ | Primer R 5′ ➝ 3’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP1 |

Potri.017G071000 Potri.001G340600 Potri.001G340500 Potri.001G340400 Potri.001G340300 Potri.001G340200 |

AGGAGTGTTCTGGCTTGTG | TCATCCTTGGCGTAAATCAGG |

| PP2 | Potri.012G090400 | TGGTAGCACAATGATGAAGGC | TCATATGTACCCTCTACGATGGC |

| PP3 | Potri.008G183200 | TGCAAAAGCAGTTGCGAAAG | AGGTTCTCGTTTACAATAACACCG |

| PP4 | Potri.010G050300 | CTCCTGATGGCCGTGAATT | CATCAAGTTGTGCTTGATGAGC |

| PP5 |

Potri.010G050200 Potri.010G050701 |

CTCAGCTGTTGTGAACTACACA | TCGAAGTTGAGAAGGGGTATG |

| PP6 | Potri.010G050501 | AACTCCATACCCCATTCCAC | TTACATGATGAACTTCTCCAGGG |

| Actin | Potri.001G309500 | GCCCAGAAGTCCTCTTCCAG | AAGGGCGGTGATCTCCTTG |

| Ubiquitin | Potri.005G096700 | AGGAACGCGTTGAGGAGAAG | TATAAGCAAAAACCGCCCCTG |

Proteomic analysis

Proteomic analysis utilized pioneer root fragments corresponding to four vascular developmental stages [40]. Three biological replicates were processed for protein isolation from 250–350 mg of fresh root fragments, each comprising a pool of roots from 3–5 plants, using a modified phenol extraction method [55].

Plant material was pulverized in liquid nitrogen and extracted in extraction buffer (0.7 M sucrose; 0.5 M Tris; 50 mM EDTA; 0.1 M KCl; 2% β-mercaptoethanol; 2% DTT; 2 mM PMSF; 1% insoluble PVP; pH 7.5; 1 ml per 200 mg of weight) for 15 min on ice. Water-saturated phenol with 0.1% 8-hydroxyquinoline (to achieve a yellow coloration) was added, and the mixture was shaken continuously for 10 min. Following centrifugation, the phenol phase was collected and mixed 1:1 with extraction buffer, shaken for 5 min, then centrifuged again. The phenol phase was then mixed with five volumes of ice-cold 0.1 M ammonium acetate in methanol and precipitated at −20 °C for 2 days. Proteins were pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with ammonium acetate solution and acetone, then air-dried. Proteins were resuspended in rehydration buffer (100 mM ammonium bicarbonate with 0.5% SDC in water), and concentrations were estimated using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For LC–MS/MS sample preparation, 20 µg of protein per sample was dissolved in 25 µl of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate.

LC–MS/MS sample preparation included protein digestion with trypsin. Samples were initially incubated with DTT for 5 min at 95 °C, followed by alkylation with IAA for 20 min in darkness at room temperature. Samples were then digested with trypsin (2 µl) for 18 h at 37 °C. After digestion, 1.5 µl of 10% TFA was added, and samples were vortexed for 10 min, centrifuged, and the peptide-containing supernatant was transferred to new vials for LC–MS/MS analysis performed by Laboratory of Mass Spectrometry in Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, Polish Academy of Sciences.

Total spectrum count was employed to quantify protein levels in the tested root fragments corresponding to various phloem developmental stages (I-IV). Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 10 software (StatSoft Poland Inc., Tulsa, OH, USA).

Results

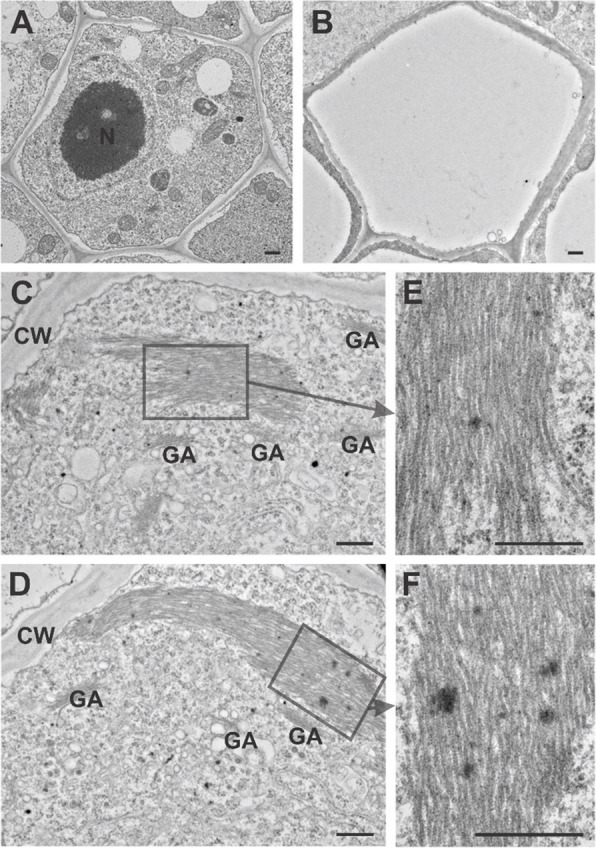

Detection of P-protein bodies in Populus trichocarpa sieve elements in transmission electron microscopy analyses

Sieve elements in the pioneer roots of P. trichocarpa were distinguished from other phloem cell types by their regular, mostly pentagonal shape in cross-section (Fig. 2A, 2B). Unlike both parenchyma and companion cells, differentiating SEs lack a large central vacuole (Fig. 2A). The defining feature of phloem differentiation is the reduction of cytoplasm in conducting cells, which lack nuclei and most other organelles (Fig. 2B). Only mitochondria, plastids, smooth endoplasmic reticulum, and small vesicles persisted in mature SEs, all of which were reduced in number and anchored to the cell wall. However, the most definitive marker of SEs was the presence of P-proteins, already visible in cells with dense cytoplasm that were still developing. P-proteins form filamentous structures in the sieve element lumen, closely associated with the cell wall (Fig. 2C-D). These filaments, with a diameter of ~ 24 nm, were primarily aligned in parallel bundles (Fig. 2E-F). Various cross-sections revealed that filaments may change direction, indicating that the arrangement of the entire P-protein bundle is more complex than initially perceived.

Fig. 2.

Sieve elements and P-proteins in the pioneer root of P. trichocarpa. An undifferentiated sieve element with electron-dense cytoplasm containing all organelles (corresponds to stadium II in Fig. 1). B Mature sieve element with electron-translucent cytoplasm, devoid of the nucleus and most other organelles (corresponds to stadium IV in Fig. 1). C-D P-proteins in different cross sections of the same sieve element (corresponds to stadium III in Fig. 1). E–F Regularly arranged bundles of P-protein filaments (corresponds to stadium III in Fig. 1). N – Nucleus, CW – Cell Wall, GA – Golgi Apparatus, scale bars = 500 nm

SEOR gene family in Populus trichocarpa

Analysis of the latest version of the P. trichocarpa genome (v4.1) aimed to identify all potential orthologues of known A. thaliana SEOR genes, encoded by At3g01680, At3g01670, and At1g67790. BLASTp searches, based on sequence homology, identified 12 genes potentially encoding SEOR proteins in P. trichocarpa (Fig. 3). Selection of P. trichocarpa SEOR orthologues was based on an E-value threshold of less than 1e−30 to mitigate false positives or negatives [56] and a sequence identity above 70%. The peptides encoded by the selected genes were all 684–723 amino acids in length.

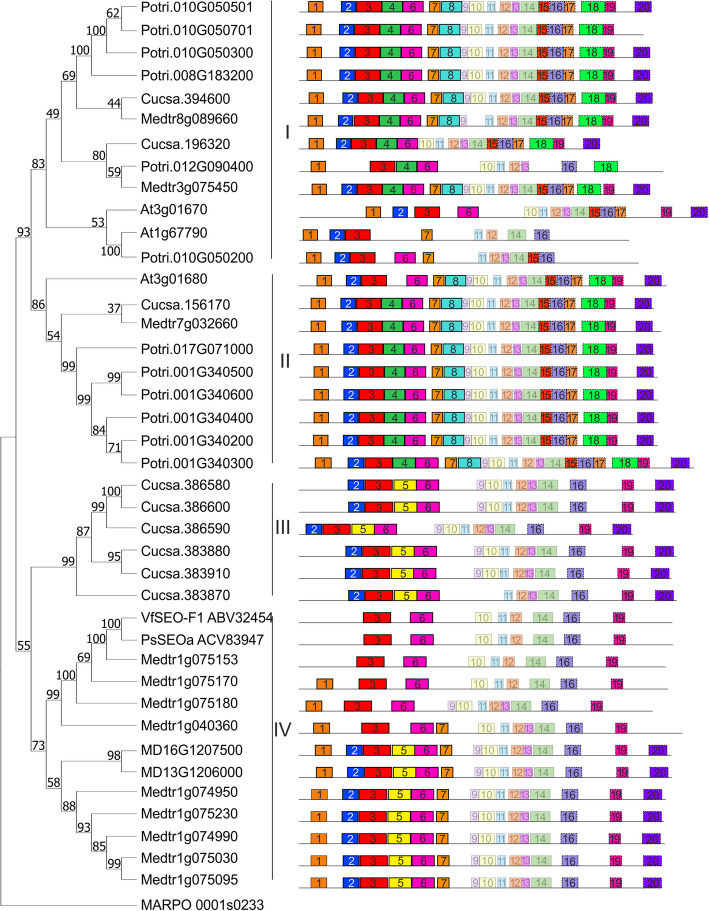

Fig. 3.

Chromosomes of P. trichocarpa showing the locations of all identified SEOR encoding genes. Chromosomes harboring at least one SEOR gene are colored purple. Additionally, position of SEOR-encoding genes identified on chromosome 1 (pink) and 10 (green)

To explore the evolutionary trajectory of SEOR protein genes in P. trichocarpa, their genomic locations were analyzed. All identified SEOR protein genes were exclusively found on chromosomes 1, 8, 10, 12, and 17, with none located on the other 14 chromosomes (Fig. 3). Chromosomes 1 and 10 hosted multiple SEOR protein genes – five and four genes, respectively (Fig. 3). Three genes were individually located on different chromosomes (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic analysis using a maximum likelihood approach produced an unrooted tree, modeling the evolutionary relationships of SEO/SEOR proteins between P. trichocarpa and several other model species (Fig. 4). Populus proteins were categorized into two groups, labeled I and II, containing 6 proteins each (Fig. 4). Group I contains proteins encoded by genes located on chromosome 8, 10 and 12 (Fig. 4). Group II consists poplar proteins encoded by genes located on chromosome 1 and 17 (Fig. 4). Poplar SEOR proteins are grouped with all Arabidopsis SEOR proteins and single SEO/SEOR from other model species (two A. thaliana, two C. sativus and two M. truncatula SEO/SEOR proteins in group I; one A. thaliana, one C. sativus and one M. truncatula SEO/SEOR proteins in group II). Most SEO proteins in Fabaceae species are grouped separately in group III and IV with two from M. domestica (Fig. 4). Additionally, an analysis of conserved peptide motifs using the MEME online tool (http://meme.nbcr.net/) [57] identified 20 motifs (Fig. 4), detailed in Additional file (Table S1). All motifs found were annotated using SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool) [46, 58] and the Pfam database [59], with 14 identified as fragments of the SEO_N (motifs 1–8) and SEO_C (motifs 15–20) domains, characteristic for SEO/SEOR proteins.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree of SEO/SEOR genes from model species: P. trichocarpa (Potri), A. thaliana (At), Medicago truncatula (Medtr), Vicia faba (Vf), Pisum sativum (Ps), Cucumis sativus (Cucsa), and Malus domestica (MD) with identified conserved peptide motifs. Peptide motifs identified as fragments of SEO_N and SEO_C domains are fully colored and framed with a solid and dashed black line, respectively. Unidentified motifs are presented as partially transparent

SEOR gene expression

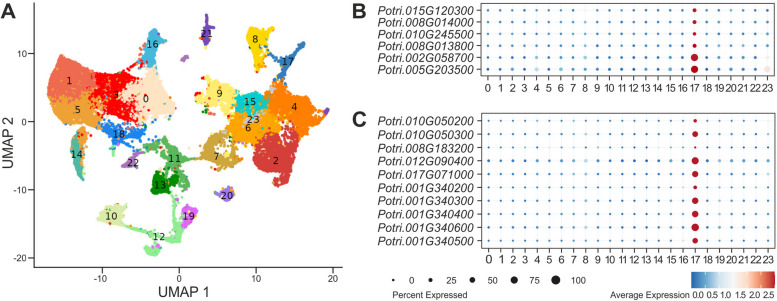

Analyses of SEOR encoding gene expression were conducted using single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq), which has been recently adapted to plant research [60], and additionally RT-qPCR technique. snRNA-seq analysis targeted whole pioneer roots, encompassing both primary phloem and xylem, whereas RT-qPCR focused on root fragments corresponding to identified vascular tissue development stages (I-IV). Additionally, organ specificity of selected gene expression was assessed using RT-qPCR on leaf and stem fragments. The pre-processing of snRNA-seq data facilitated the detection and removal of low-quality nuclei. Consequently, over 33,000 root nuclei from two highly correlated biological replicates were profiled, demonstrating the high quality of the data. Subsequently, nuclei were clustered into 24 groups based on their expression profiles and visualized in 2D Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) space (Fig. 5A). Among these clusters, cluster 17, containing 600 nuclei, was identified using six known marker genes [61, 62] (Fig. 5B) as representing phloem sieve elements (Fig. 5). Notably, 589 of these nuclei (over 98%) expressed at least one SEOR gene. The snRNA-seq analysis revealed the expression of 10 out of the 12 identified SEOR encoding genes, all of which were expressed: Potri.010G050200, Potri.010G050300, Potri.008G183200, Potri.010G090400, Potri.017G071000, Potri.001G340200, Potri.001G340300, Potri.001G340400, Potri.001G340500, Potri.001G340600 (Fig. 5C). All these genes were specifically expressed in nuclei from cluster 17 (Fig. 5C). Additionally, SEOR gene expression was significantly higher in nuclei corresponding to sieve elements (Fig. 5C). However, the percentage of nuclei exhibiting high average expression of SEOR genes (over 1.5) varied among individual genes, from less than 1% for one gene (Potri.008G183200) to between 20% and nearly 80% for others (Potri.010G340600) (Fig. 5C; Available data).

Fig. 5.

A UMAP visualization of 24 cell clusters in the P. trichocarpa root. Dots represent single nuclei with colors denoting clusters. B Expression pattern of known sieve element marker genes. C Expression pattern of identified SEOR genes across all clusters. Dot diameter indicates the proportion of cluster nuclei expressing the gene, and color denotes the average relative expression of a particular gene in each cluster

Parallel to snRNA-seq, RT-qPCR analysis was performed on root fragments representing subsequent vascular tissue developmental stages, ranging from meristematic tissue (stage I), through phloem precursors (stage II), phloem maturation (stage III), to mature phloem with developing xylem (stage IV). Due to the high similarity and sequence overlap among the studied genes, it was not feasible to design a specific pair of primers for each SEOR gene. Consequently, some primer pairs were designed to overlap several gene sequences (Tab. 1). Almost all tested primer pairs exhibited similar expression profiles, with relative expression levels increasing across the developmental stages (Fig. 6A). The highest gene expression for each was observed at stage IV, characterized by fully differentiated phloem cells (Fig. 6A). Additionally, gene expression was evaluated in stem and leaf tissues, and reaction with every primer pair gave the same PCR-product as in root samples (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Heatmap visualization of relative expression of P. trichocarpa SEOR genes in four root developmental stages (I-IV) using six pairs of primers specific for one or overlapping sequences of 2/6 genes, as detailed in Tab. 1. Relative quantification for each primer pair-reaction was normalized according to actin and ubiquitin gene expression. Pink indicates up-regulation relative to stage I, which represents the apical meristem (with no differentiating phloem cells), and green indicates down-regulation. Color intensity represents expression levels

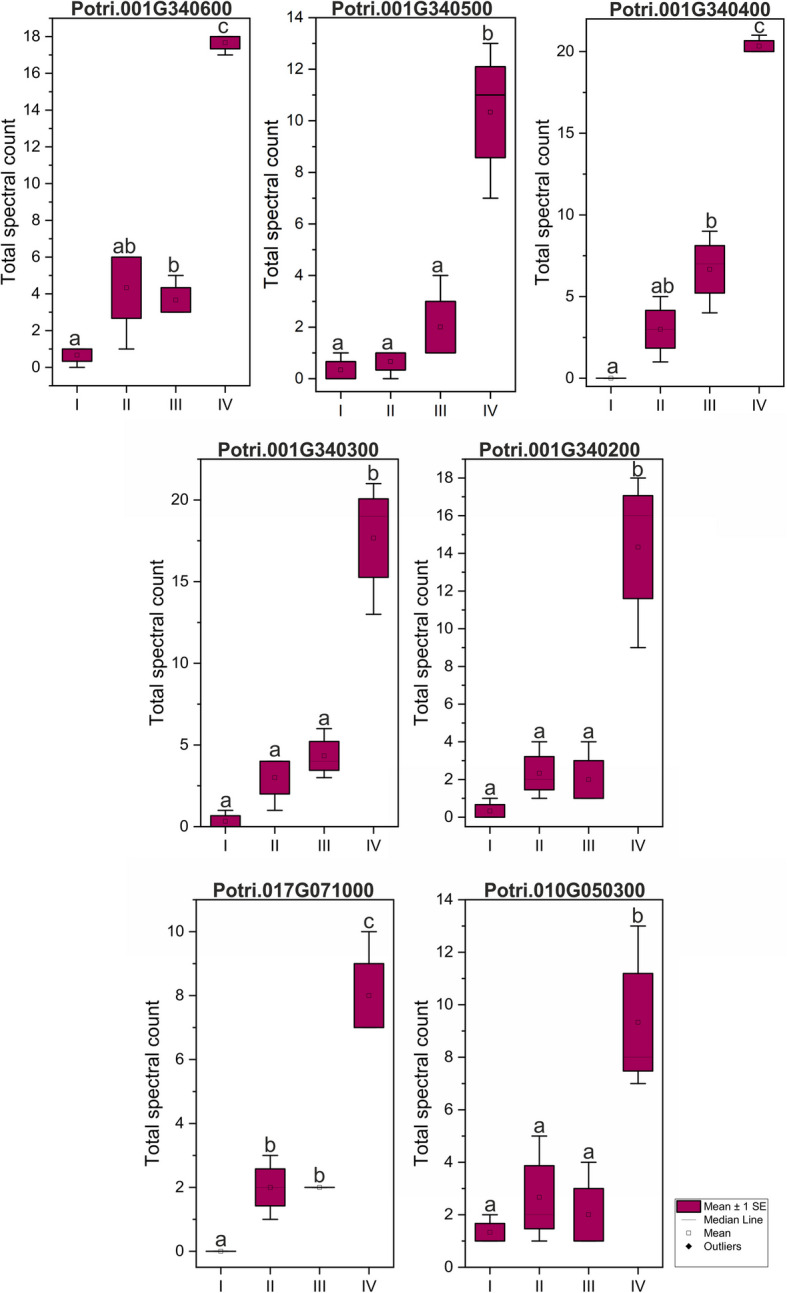

SEOR protein identification in LC–MS/MS analysis

Proteome analysis using LC–MS/MS techniques confirmed the presence of seven SEOR proteins in P. trichocarpa root samples (Fig. 7). All of them were also detected at the transcriptomic level via snRNA-seq (Potri.001G340600, Potri.001G340500, Potri.001G340400, Potri.001G340300, Potri.001G340200, Potri.017G071000, Potri.010G050300). Additionally, the expression analyses at the transcriptomic and proteomic levels showed divergence for three proteins, which gene expression was observed without detectable protein levels (Potri.008G183200, Potri.010G050200, and Potri.012G090400) (Figs. 5, 7). Moreover, the proteome analysis facilitated quantitative assessments. An increasing trend in the abundance of identified SEOR proteins was noted through the root developmental stages (I-IV) (Fig. 7). Notably, at stage IV, which features fully developed phloem cells, the quantities of all identified P-proteins, as measured by total spectrum count, were significantly higher (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Normalized total spectral counts for identified SEOR proteins across root developmental stages I-IV, from three biological replicates, showing mean values ± standard error. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test, p-value < 0.05

Discussion

Mature sieve elements are almost devoid of cytoplasm, yet they contain characteristic protein structures whose functions are mostly unknown or unclear. However, the cellular specificity of these structures suggests a significant role in sieve element functionality.

In our study, we observed phloem-characteristic protein agglomerates in developing sieve elements using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 2). These structures are reminiscent of those observed in maturing Nicotiana tabacum sieve elements [6, 63]. In tobacco, phloem protein imaging across immature and mature sieve elements typically shows one agglomerate per cell, occasionally positioned near the plasma membrane or more frequently on sieve plates [64]. It has been hypothesized that these phloem-specific proteins contribute to sieve plate occlusion by forming a plug upon cellular wounding, though this function remains controversial [64–66].

Historically, SEO, being family of phloem-specific proteins, were identified exclusively within the Fabaceae species as structural elements of forisomes. Subsequent discoveries of SEO encoding gene orthologues in numerous non-Fabaceae plants, which lack forisomes, have led to ambiguities regarding the general function of these proteins, thus, these genes have been collectively termed SEOR. To date, only two specialized types of P-proteins have been characterized: the Fabaceae-specific SEO proteins being part of forisomes and the Cucurbitaceae-specific PP1. Forisomes are capable of undergoing conformational changes induced by calcium ions, which facilitate the opening or plugging of sieve elements following wounding and promote subsequent plant regeneration [29, 67]. This functionality has been validated through immunological studies in the model legume species M. truncatula, which possesses three SEO proteins [27, 68]. The other functionally characterized P-protein, PP1, identified in Cucurbita maxima, forms filamentous structures within the slime plugs of sieve elements [69]. Intriguingly, the C. maxima PP1 protein lacks significant sequence similarity or specific domains associated with SEO proteins, suggesting it should not be categorized within the SEO gene family. Nonetheless, it may perform a similar, unique function in Cucurbitaceae plants, as no PP1 orthologues have been found in other species [32, 70]. Despite the characterization of these two types of P-proteins, the molecular nature and function of phloem proteins, found across many mono- and dicotyledonous species, remain elusive. Notably, the number of SEO/SEOR encoding genes varies significantly among plant species, ranging from a single gene in species such as Pisum sativum and Canavalia gladiata to 55 genes in Cercis canadensis (Tab. 2; based on [32] and Phytozome database). To bridge the knowledge gap concerning P-proteins, we conducted a comprehensive analysis in the tree model species P. trichocarpa. Our multidisciplinary research spanning genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic levels concludes that fully developed sieve elements, though largely devoid of cytoplasm, still harbor specific protein structures.

Table 2.

The number of identified SEO and SEOR genes mentioned by Rüping [32] and found in Phytozome database in the year of writing (in brackets)

| Species | SEO/SEOR genes |

|---|---|

| Medicago truncatula | 9 (13) |

| Glycine max | 26 |

| Vicia faba | 1 (13) |

| Canavalia gladiata | 1 |

| Pisum sativum | 1 |

| Malus domestica | 2 (16) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 3 |

| Vitis vinifera | 15 |

| Solanum phureja | 3 |

| Amaranthus hypochondriacus | 6 |

| Anacardium occidentale | 12 |

| Arachis hypogaea | 38 |

| Camelina sativa | 9 |

| Brassica rapa | 5 |

| Carya illinoinensis cv. ‘Elliott’ | 24 |

| Cercis canadensis | 55 |

| Corymbia citriodora | 46 |

| Fragaria × ananassa cv. ‘Royal Royce’ | 35 |

| Lotus japonicus | 11 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | 6 |

| Theobroma cacao | 8 |

Previously, only one P. trichocarpa gene was identified as a potential orthologue of the A. thaliana SEOR gene, Potri.017G071000 [36]. Our comprehensive genome-wide analysis has revealed that the P. trichocarpa genome contains 12 SEOR encoding genes (Fig. 3), representing the highest number identified in any tree model species to date.

The organization of SEO/SEOR encoding genes within genomes is intriguing aspect of this gene family. Previous studies have shown that many SEO genes are arranged in tandem duplications across various model species. In M. truncatula, this applies to seven out of nine genes on chromosome 1, V. vinifera to three and eight genes on chromosomes 1 and 14, respectively, and in G. max to five and six genes on chromosomes 10 and 20, respectively [32]. Our analysis also identified SEOR genes being arranged in tandem duplications in P. trichocarpa on chromosomes 1 and 10 containing five and four SEOR encoding genes respectively. This pattern suggests that the tandem arrangement of SEO/SEOR-protein encoding genes might be a common phenomenon among plant species. The organization of these genes reflects the evolutionary history of the Populus genome, shaped by duplication events. The most recent salicoid-specific duplication impacted around 92% of the genome [50]. It was followed by a series of rearrangements, featuring tandem fusions and duplications, also local, potentially including segments containing SEOR encoding genes.

Originally, P-proteins were believed to form only immobilized structures within individual sieve elements [71, 72]. However, subsequent research demonstrated that P-proteins could undergo long-distance transport across graft unions [73]. Intriguingly, while the trafficking involves proteins, SEOR-protein mRNA was not detectable in the tested Cucumis sativus scion [73], contrasting with reports of mRNA transport from companion cells to sieve elements [74]. In Cucurbita species, SEOR-protein mRNA has been found to accumulate exclusively in companion cells [70, 75]. Our snRNA-seq analysis did not reveal extensive expression of SEOR encoding genes in companion cells, which were identified as cluster number 8 (Fig. 5).

One hypothesized function of SEO/SEOR-proteins is to protect the phloem or respond to phloem-feeding insects and fungal pathogens. To date, this function remains unconfirmed. However, it has been shown that SEOR-proteins can specifically interact with OGA488 [76], an oligosaccharide used for chitin detection. Chitin is a component of phloem-feeding insect stylets and fungal pathogen cell walls. The biological significance of SEOR-protein binding to OGA488, whether incidental or functional, remains unclear. Additionally, non-dispersive phloem-protein bodies in P. trichocarpa, composed of SEOR proteins, do not respond to cellular wounding [36], which does not support the proposed protective function.

Transcriptomic investigation on P. trichocarpa stem has shown that seven SEOR-encoding genes may be expressed: Potri.001G340200, Potri.001G340300, Potri.001G340400, Potri.001G340600, Potri.010G050300, Potri.012G090400, Potri.017G071000 [61]. Our single-nucleus RNA sequencing analysis revealed 10 expressed SEOR genes, what may indicate differences in the SEOR-gene expression between poplar organs.

Proteomic investigations of sieve elements are challenging due to difficulties in isolating them; most studies have utilized phloem sap, which varies in protein composition by plant organ, age, or experimental conditions [77]. Phloem sap contains only the soluble proteome and lacks immobile proteins essential for sieve element functions [78]. To date, SEOR proteins have not been observed in phloem sap, with the sole exception of a potential orthologue of Arabidopsis SEOR1 (At3g01680 encoded) found in the exudate from C. maxima [28]. Our proteomic research, which identified seven SEOR proteins, suggests that P-protein bodies in P. trichocarpa may comprise more than the single protein previously reported [36].

Our findings indicate that both gene expression and protein levels are significantly elevated in the fourth developmental stage of the root, correlating with pseudotime data from single-cell RNA sequencing of Arabidopsis root, which shows all SEOR encoding genes being highly expressed at the final stage of phloem development [35]. SEO/SEOR encoding genes are prevalent throughout the plant kingdom, having been identified in numerous mono- and dicotyledonous plant species.

Our investigation into the SEOR genes in P. trichocarpa marks the first examination of this surprisingly large gene family, likely formed through numerous duplication events within the Populus genome. These proteins are hypothesized to contribute to the specific protein structures observed in sieve elements (Fig. 2). However, the precise functions of these SE-specific proteins remain elusive. Given their prevalence in most studied plant species, uncovering their role in phloem cells could be pivotal. Potential functions may include the modulation of pore opening/closing between neighboring sieve elements or providing structural support to sieve elements, which are nearly devoid of cellular content. Another potential role for SEOR-proteins could be related to phloem-dependent systemic signaling, as the phloem is a critical component in the long-distance transport of numerous physiologically significant molecules, such as photoassimilates [79, 80] and signaling molecules (proteins, mRNA, hormones, and lipids) [81–83]. This function is particularly vital for plant development under both physiological conditions and in response to biotic and abiotic stresses.

In this study, ultrastructural observations of maturing phloem cells were integrated with genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic approaches to conduct a comprehensive identification and analysis of SEOR proteins in the model tree species, P. trichocarpa. This multi-omic approach has enabled us to characterize proteins that are likely crucial for sieve element function. The certain function of these proteins is still unknown despite over a century of research, however there are some reports indicating that SEOR function may be connected to the defense response to biotic stresses. Ultimately, our study lays the groundwork for future functional studies of phloem cells, which are technically challenging but increasingly feasible. Advancing our understanding of phloem physiology is of paramount importance, especially in the context of ongoing climate change.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Magdalena Ślachetka from the Department of General Botany at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań for her support in plant cultivation and material collection. We acknowledge the use of the infrastructure developed under the project NEBI – National Research Center for Imaging in the Biological and Biomedical Sciences, POIR.04.02.00-00-C004/19, co-financed through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) in the frame of Smart Growth Operational Programme 2014-2020 (Measure 4.2 Development of modern research infrastructure of the science sector). The computations were performed using the infrastructure resources of the Poznan Supercomputing and Networking Center (PSNC), contract no. 1021/0711/2023.

Abbreviations

- NPB

Non-dispersive P-protein body

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SE

Sieve element

- SEO

Sieve element occlusion

- SEOR

Sieve element occlusion-related

- snRNA-seq

Single-nucleus RNA-sequencing

Authors’ contributions

KK and ABZ conceived the original concept and research plan, designed the experiments, and oversaw the study. KK was responsible for designing and performing genomic and RT-qPCR analyses, preparing samples for proteomic analysis, analyzing proteomic data. ASC and MT conducted the flow cytometry experiments. ASC and MMZ designed and performed the snRNA-seq, focusing on library preparation and data analysis, respectively. PJ provided validation and oversight for the flow cytometry and snRNA-seq components of the study. KK and KMM were responsible for plant provision, material collection and isolation of nuclei for snRNA-seq. KMM and JM conducted the TEM analysis. KK drafted the manuscript with contributions from ASC, MMZ and KMM, while PJ and ABZ provided critical feedback and supervision. All authors participated in data analysis and approved the final manuscript. PJ and ABZ also provided essential resources, and ABZ provided funding for the research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Grant no. 2020/39/B/NZ3/00018 from the National Science Centre, Poland to ABZ.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the RepOD repository, [https://repod.icm.edu.pl/privateurl.xhtml?token=e9dd8cc5-9051-48f1-a813-ca3f7e202ddb] and GEO database [https://eur01.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2Fgeo%2Fquery%2Facc.cgi%3Facc%3DGSE281380&data=05%7C02%7Ckarolina.kulak%40amu.edu.pl%7Ccf0435b38c3e42a0a2e408dd03bb9160%7C73689ee1b42f4e25a5f666d1f29bc092%7C0%7C0%7C638670826323633465%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJFbXB0eU1hcGkiOnRydWUsIlYiOiIwLjAuMDAwMCIsIlAiOiJXaW4zMiIsIkFOIjoiTWFpbCIsIldUIjoyfQ%3D%3D%7C0%7C%7C%7C&sdata=lh%2FBy44VuSTzaOjckguoggtTNIUWyZ83vS6yplvagME%3D&reserved=0].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Karolina Kułak, Email: karolina.kulak@amu.edu.pl.

Agnieszka Bagniewska-Zadworna, Email: agnieszka.bagniewska-zadworna@amu.edu.pl.

References

- 1.Evert RF. Esau’s Plant Anatomy: John Wiley & Sons. New Jersey: Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michalak KM, Wojciechowska N, Marzec-Schmidt K, Bagniewska-Zadworna A. Conserved autophagy and diverse cell wall composition: unifying features of vascular tissues in evolutionarily distinct plants. Ann Bot. 2024;133(4):559–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heo JO, Blob B, Helariutta Y. Differentiation of conductive cells: a matter of life and death. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;35:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aikman D. Phloem transport. Nature. 1974;252:760. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behnke HD, Sjolund RD. Sieve Elements: comparative structure, introduction and development. Berlin: Springer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esau K, Cronshaw J. Tubular components in cells of healthy and tobacco mosaic virus-infected Nicotiana. Virology. 1967;33(1):26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esau K. Minor Veins in Beta-Leaves - Structure Related to Function. P Am Philos Soc. 1967;111(4):219–33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cronshaw J. Phloem structure and function. Annu Rev Plant Phys. 1981;32:465–84. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evert RF. Dicotyledons. Sieve Elements. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990:103–37.

- 10.Read SM, Northcote DH. Subunit structure and interactions of the phloem proteins of Cucurbita maxima (pumpkin). Eur J Biochem. 1983;134(3):561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eschrich W. Biochemistry and fine structure of phloem in relation to transport. Ann Rev Plant Physio. 1970;21:193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjolund RD, Shih CY, Jensen KG. Freeze-fracture analysis of phloem structure in plant-tissue cultures: III. P-protein, sieve area pores, and wounding. J Ultrastruct Res. 1983;82(2):198–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Will T, van Bel AJE. Physical and chemical interactions between aphids and plants. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(4):729–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noll GA, Furch ACU, Rose J, Visser F, Prüfer D. Guardians of the phloem - forisomes and beyond. New Phytol. 2022;236(4):1245–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medina-Ortega KJ, Walker GP. Faba bean forisomes can function in defence against generalist aphids. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38(6):1167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cronshaw J, Sabnis DD. Phloem Proteins. Sieve Elements. In: Behnke H-D, Sjolund RD (eds) Sieve elements, comparative structure, induction and development. Berlin: Springer; 1990:257–283.

- 17.Behnke HD. Nondispersive protein bodies in sieve elements - a survey and review of their origin, distribution and taxonomic significance. Iawa Bull. 1991;12(2):143–75. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behnke HD. Sieve-element plastids, nuclear crystals and phloem proteins in the Zingiberales. Bot Acta. 1994;107(1):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esau K. A study of some sieve tube inclusions. Am J Bot. 1947;34(4):224–33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra U, Spanner DC. Fine structure of sieve tubes of Salix caprea (L) and its relation to electroosmotic theory. Planta. 1970;90(1):43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deshpande BP, Evert RF. A reevaluation of extruded nucleoli in sieve elements. J Ultrastruct Res. 1970;33(5–6):483–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esau K. Protein inclusions in sieve elements of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). J Ultrastruct Res. 1978;63(2):224–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cronshaw J, Esau K. Tubular and fibrillar components of mature and differentiating sieve elements. J Cell Biol. 1967;34(3):801–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evert RF, Eschrich, Eichhorn SE. P-Protein distribution in mature sieve elements of Cucurbita-Maxima. Planta. 1973;109(3):193–210. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Wu JL, Hao BZ. Ultrastructure of p-protein in Hevea brasiliensis during sieve tube development and after wounding. Protoplasma. 1990;153(3):186–92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knoblauch M, van Bel AJE. Sieve tubes in action. Plant Cell. 1998;10(1):35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelissier HC, Peters WS, Collier R, van Bel AJE, Knoblauch M. GFP tagging of sieve element occlusion (SEO) proteins results in green fluorescent forisomes. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49(11):1699–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin MK, Lee YJ, Lough TJ, Phinney BS, Lucas WJ. Analysis of the pumpkin phloem proteome provides insights into angiosperm sieve tube function. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(2):343–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knoblauch M, Noll GA, Van Bel AJE, Prüfer D, Peters WS. Forisomes consist of a novel class of contractile proteins. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003;82:70–1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knoblauch M, Peters WS, Ehlers K, van Bel AJE. Reversible calcium-regulated stopcocks in legume sieve tubes. Plant Cell. 2001;13(5):1221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters WS, Haffer D, Hanakam CB, van Bel AJE, Knoblauch M. Legume phylogeny and the evolution of a unique contractile apparatus that regulates phloem transport. Am J Bot. 2010;97(5):797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rüping B, Ernst AM, Jekat SB, Nordzieke S, Reineke AR, Müller B, et al. Molecular and phylogenetic characterization of the sieve element occlusion gene family in Fabaceae and non-Fabaceae plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anstead JA, Froelich DR, Knoblauch M, Thompson GA. Arabidopsis P-protein filament formation requires both AtSEOR1 and AtSEOR2. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53(6):1033–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wendrich JR, Yang BJ, Vandamme N, Verstaen K, Smet W, Van de Velde C, et al. Vascular transcription factors guide plant epidermal responses to limiting phosphate conditions. Science. 2020;370(eaay4970):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roszak P, Heo JO, Blob B, Toyokura K, Sugiyama Y, de Luis Balaguer MA, et al. Cell-by-cell dissection of phloem development links a maturation gradient to cell specialization. Science. 2021;374(eaba5531):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullendore DL, Ross-Elliott T, Liu Y, Hellmann HH, Roalson EH, Peters WS, et al. Non-dispersive phloem-protein bodies (NPBs) of Populus trichocarpa consist of a SEOR protein and do not respond to cell wounding and Ca2+. Peer J. 2018;6:e4665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wojciechowska N, Marzec-Schmidt K, Kalemba EM, Zarzynska-Nowak A, Jagodzinski AM, Bagniewska-Zadworna A. Autophagy counteracts instantaneous cell death during seasonal senescence of the fine roots and leaves in Populus trichocarpa. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagniewska-Zadworna A, Byczyk J, Eissenstat DM, Oleksyn J, Zadworny M. Avoiding transport bottlenecks in an expanding root system: Xylem vessel development in fibrous and pioneer roots under field conditions. Am J Bot. 2012;99(9):1417–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagniewska-Zadworna A, Stelmasik A. Root heterogeneity and developmental stage determine the pattern of cellulose synthase and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene expression profiles during xylogenesis in Populus trichocarpa (Torr. Et Gray). Int J Plant Sci. 2015;176(5):458–67.

- 40.Bagniewska-Zadworna A, Arasimowicz-Jelonek M, Smolinski DJ, Stelmasik A. New insights into pioneer root xylem development: evidence obtained from plants grown under field conditions. Ann Bot. 2014;113(7):1235–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunziker P, Halkier BA, Schulz A. Arabidopsis glucosinolate storage cells transform into phloem fibres at late stages of development. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(16):4305–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuskan GA, DiFazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science. 2006;313(5793):1596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sreedasyam A, Plott C, Hossain MS, Lovell JT, Grimwood J, Jenkins JW, et al. JGI Plant Gene Atlas: an updateable transcriptome resource to improve functional gene descriptions across the plant kingdom. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(16):8383–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bailey TL, Johnson J, Grant CE, Noble WS. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Letunic I, Khedkar S, Bork P. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D458–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11 Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(7):3022–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dorrity MW, Alexandre CM, Hamm MO, Vigil AL, Fields S, Queitsch C, et al. The regulatory landscape of roots at single-cell resolution. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodstein DM, Shu SQ, Howson R, Neupane R, Hayes RD, Fazo J, et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(D1):D1178–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tuskan GA, DiFazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science. 2006;313(5793):1596–604. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hao YH, Stuart T, Kowalski MH, Choudhary S, Hoffman P, Hartman A, et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2024;42(2):293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choudhary S, Satija R. Comparison and evaluation of statistical error models for scRNA-seq. Genome Biol. 2022;23(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hurkman WJT, C.K. Solubilization of plant membrane proteins for analysis by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Plant Physiol. 1987;81:802–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Nestor BJ, Bayer PE, Fernandez CGT, Edwards D, Finnegan PM. Approaches to increase the validity of gene family identification using manual homology search tools. Genetica. 2023;151(6):325–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bailey TL, Elkan C, editors. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology; 1994; Menlo Park, California: AAAI Press. [PubMed]

- 58.Letunic I, Bork P. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D493–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz HR, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kulak K, Wojciechowska N, Samelak-Czajka A, Jackowiak P, Bagniewska-Zadworna A. How to explore what is hidden? A review of techniques for vascular tissue expression profile analysis. Plant Methods. 2023;19:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Y, Tong S, Jiang Y, Ai F, Feng Y, Zhang J, et al. Transcriptional landscape of highly lignified poplar stems at single-cell resolution. Genome Biol. 2021;1–22(1):319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanden NC, Schulz A. Stationary sieve element proteins. J Plant Physiol. 2021;266:153511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wooding FBP. P protein and microtubular systems in Nicotiana callus phloem. Planta. 1969;85(3):284–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ernst AM, Jekat SB, Zielonka S, Müller B, Neumann U, Rüping B, et al. Sieve element occlusion (SEO) genes encode structural phloem proteins involved in wound sealing of the phloem. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(28):E1980–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Froelich DR, Mullendore DL, Jensen KH, Ross-Elliott TJ, Anstead JA, Thompson GA, et al. Phloem ultrastructure and pressure flow: sieve-element-occlusion-related agglomerations do not affect translocation. Plant Cell. 2011;23(12):4428–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knoblauch M, Froelich DR, Pickard WF, Peters WS. SEORious business: structural proteins in sieve tubes and their involvement in sieve element occlusion. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(7):1879–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knoblauch M, Noll GA, Müller T, Prüfer D, Schneider-Hüther I, Scharner D, et al. ATP-independent contractile proteins from plants. Nat Mater. 2003;2(9):600–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Noll GA, Fontanellaz ME, Rüping B, Ashoub A, van Bel AJE, Fischer R, et al. Spatial and temporal regulation of the forisome gene for1 in the phloem during plant development. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;65(3):285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beyenbach J, Weber C, Kleinig H. Sieve-Tube proteins from Cucurbita maxima. Planta. 1974;119(2):113–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clark AM, Jacobsen KR, Bostwick DE, Dannenhoffer JM, Skaggs MI, Thompson GA. Molecular characterization of a phloem-specific gene encoding the filament protein, phloem protein 1 (PP1), from Cucurbita maxima. Plant J. 1997;12(1):49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith LM, Sabnis DD, Johnson RPC. Immunocytochemical localization of phloem lectin from Cucurbita maxima using peroxidase and colloidal-gold labels. Planta. 1987;170(4):461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fisher DB, Wu Y, Ku MSB. Turnover of soluble proteins in the wheat sieve tube. Plant Physiol. 1992;100(3):1433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Golecki B, Schulz A, Thompson GA. Translocation of structural P proteins in the phloem. Plant Cell. 1999;11(1):127–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuhn C, Franceschi VR, Schulz A, Lemoine R, Frommer WB. Macromolecular trafficking indicated by localization and turnover of sucrose transporters in enucleate sieve elements. Science. 1997;275(5304):1298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bostwick DE, Dannenhoffer JM, Skaggs MI, Lister RM, Larkins BA, Thompson GA. Pumpkin phloem lectin genes are specifically expressed in companion cells. Plant Cell. 1992;4(12):1539–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Azizpor P, Sullivan L, Lim A, Groover A. Facile labeling of sieve element Phloem-protein bodies using the reciprocal oligosaccharide probe OGA. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:80923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Thompson GA, van Bel AJE. Phloem: molecular cell biology, systemic communication, biotic interactions. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- 78.Anstead JA, Hartson SD, Thompson GA. The broccoli (Brassica oleracea) phloem tissue proteome. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lalonde S, Wipf D, Frommer WB. Transport mechanisms for organic forms of carbon and nitrogen between source and sink. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:341–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Raven PH, Evert RF, Eichhorn SE. Biology of Plants. New York: Worth Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oparka KJ, Cruz SS. The great escape: phloem transport and unloading of macromolecules. Annu Rev Plant Phys. 2000;51:323–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hoad GV. Transport of hormones in the phloem of higher plants. Plant Growth Regul. 1995;16(2):173–82. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Benning UF, Tamot B, Guelette BS, Hoffmann-Benning S. New aspects of phloem-mediated long-distance lipid signaling in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2012;28(3):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the RepOD repository, [https://repod.icm.edu.pl/privateurl.xhtml?token=e9dd8cc5-9051-48f1-a813-ca3f7e202ddb] and GEO database [https://eur01.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2Fgeo%2Fquery%2Facc.cgi%3Facc%3DGSE281380&data=05%7C02%7Ckarolina.kulak%40amu.edu.pl%7Ccf0435b38c3e42a0a2e408dd03bb9160%7C73689ee1b42f4e25a5f666d1f29bc092%7C0%7C0%7C638670826323633465%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJFbXB0eU1hcGkiOnRydWUsIlYiOiIwLjAuMDAwMCIsIlAiOiJXaW4zMiIsIkFOIjoiTWFpbCIsIldUIjoyfQ%3D%3D%7C0%7C%7C%7C&sdata=lh%2FBy44VuSTzaOjckguoggtTNIUWyZ83vS6yplvagME%3D&reserved=0].