Abstract

Purpose

To explore the effects of high-altitude hypoxia on the microenvironment of oocyte development and fertilization potential, we compared the metabolomic patterns of follicular fluid from women living in different altitude areas and traced their oocyte maturation and subsequent development.

Methods

A total of 315 clinical cases were collected and divided into three groups according to their residence altitudes: 138 cases in low-altitude (< 2300 m) group, 100 cases in middle-altitude (2300–2800 m) group and 77 cases in high-altitude (> 2800 m) group. The clinical outcomes were statistically estimated, including hormonal level, oocyte maturation, in vitro fertilization, and embryo development. Meanwhile, a metabolomic analysis was performed on the follicular fluid of women from different groups using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry and differential metabolites were analyzed through the KEGG pathway.

Results

The clinical data indicated that the physical condition and reproductive hormone secretion were similar among different groups. Although personalized gonadotropin-releasing hormone strategies were applied, the numbers of antral follicles and obtained oocytes were not impacted by the residence altitude change. In in vitro culture, the maturing rate, fertility rate and cleavage rate of high-altitude group were compared with the other groups. However, the rates of high-quality embryo, formative blastocyst, and available blastocyst were gradually decreased with the rise of residence altitude. Metabolome analysis identified 1193 metabolites in female follicular fluid. Differential analysis indicated that metabolic components in follicular fluid were remarkably changed with the elevation of residence altitude. These differential metabolites were closely related with amino acid metabolism, protein digestion and absorption, oocyte meiosis and steroid biosynthesis.

Conclusion

The residence altitude alters the microenvironment of follicular fluid, which could damage the oocyte developmental potential. This study provides diagnostic basis and therapeutic targets for research on female oocyte and embryo development.

Keywords: Embryo development, Female fertility, Follicular fluid, Hypoxic adaptation, Oocyte maturation

What does this study add to the clinical work

| This study revealed the critical influence of high-altitude hypoxia on female follicular fluid and oocyte developmental potential. |

Introduction

Approximately 10 to 15% of the population experiences infertility throughout the world, and the number keeps increasing all the time [1, 2]. Most of infertile couples have an identifiable cause, including ovulatory dysfunction, male factor infertility, and tubal disease. Lifestyle and environmental factors can adversely affect human fertility, such as dietary changes [3], unhealthy lifestyle [4], and environmental stress [5]. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) has developed rapidly over the past few decades, including artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF), embryo transplantation, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and preimplantation genetic testing [6–8]. Although ART helps avoid some reproductive disorders, it still requires high-quality oocytes in order to satisfy in vitro maturation and subsequent embryo development [9, 10].

Hypoxia has been widely accepted as an important environmental factor that has a major impact on reproductive health in animals [11, 12]. Despite that moderate hypoxia could enhance embryonic cell lineage choices [13] and be beneficial for the labor progression [14], the oocyte [15], embryo [16] and fetal development [17] have been shown to be impaired by hypoxic environment. Nevertheless, studies based on human oocyte development in hypoxic environment are still relatively rare. A hypothesis has been provided that hypoxia could be the main determinant of follicular senescence [18] due to the high sensitivity of ovarian antral follicle on the oxygen concentration [19]. Therefore, it is necessary to study whether hypoxia environment will cause the abnormality of female follicular state and oocyte development.

Follicular fluid is a liquid filling the follicular antrum, composed of hormones, enzymes, anticoagulants, electrolytes, reactive oxygen species, antioxidants, and so on [20]. As an important mediator in the communication between granular cells, follicular fluid is an essential element to the oocyte maturation and successful fertilization [21, 22]. Metabolome is a new omics feature of organisms. Compared with genome, transcriptome and proteome, metabolome can reflect the state of follicular environment more directly and hence should be a better alternative to detect the physiological dynamics. We suppose that the change of follicular fluid can reflect the reproductive potential difference of women from different residence altitudes. Hence, in this study, we collected the follicular fluids in women of childbearing age from different residence altitudes and performed retrospective analysis of oocyte maturation and embryo development. Our findings provide a key basic data of female reproductive function living in high-attitude area and contribute to the understanding of the hypoxic effect on female fertility maintenance.

Materials and methods

Study participants

A total of 315 women who underwent IVF treatments at the Fertility Center of Qinghai People’s Hospital from September 2017 to September 2022 were recorded and retrospectively analyzed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) with female age ≤ 30 years old; (2) with a body mass index (BMI) of 18.5–23.0 kg/m2; (3) who underwent their first IVF cycle; (4) with male who has normal semen routine; (5) signing an informed consent form. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) infertility due to polycystic ovarian syndrome or unknown reasons; (2) chromosome abnormalities in either spouse; (3) previous malignant tumors such as ovarian tumors; (4) suffering from other systemic diseases, such as severe lymphatic and hematopoietic disorders; (5) with activities, such as smoking, alcohol consumption and medical supplement.

Outcomes of controlled ovarian stimulation

Patients were grouped into three groups according to their residence altitudes: low-altitude group, 138 cases at an altitude under 2300 m; middle-altitude group, 100 cases at an altitude of 2300–2800 m; high-altitude group, 77 cases at an altitude above 2800 m. On day 3 of the IVF cycle protocol, 6 ml blood was collected between 7 and 10 a.m. Samples were centrifuged at 1000 g for 20 min at room temperature and serums were immediately transported to the Medical Diagnostic Center of Qinghai People’s Hospital for hormone level detection. The 6 main reproductive hormones were detected, including follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol (E2), progesterone (P), prolactin (PRL) and testosterone (T), by chemiluminescent immunoassay on Immulite 2000 immunoassay system (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Germany).

Women in the study underwent one of the following controlled ovarian stimulation protocols based on clinical indication: luteal-phase gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-agonist protocol: in the luteal phase of the preceding cycle, follicular state was detected by B-ultrasonography and 0.05–0.10 mg triptorelin was injected to reach the pituitary health regulation standard. Then human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) was given to promote ovulation. When there were 1 follicle with a diameter over 18 mm or 2 follicles with a diameter over 17 mm, 0.25 mg hCG trigger was performed and oocyte retrieval was scheduled after 34–36 h; GnRH-antagonist protocol: based on serum hormone level and follicular size, patients were administered with the proper amount of cetrorelix acetate daily. When there were 2 or 3 follicles with a diameter over 18 mm, 0.20 mg triptorelin was injected and oocyte retrieval was scheduled after 34–36 h.

IVF and embryo culture

The retrieved cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were placed in G-IVF™ PLUS medium (10136, Vitrolife, Sweden) covered by paraffin oil and incubated in a humidified 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. The oocyte maturity was evaluated after incubation for 2 h. Besides, fresh ejaculated semen samples were obtained by masturbation after 2–7 days’ abstention. Sperm concentration and progressive motility were assessed by computer-assisted semen analysis according to the fifth edition of WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen [23]. Semen samples were used with the following parameters [24]: sperm concentration ≥ 15 million sperm/mL, the total motility ≥ 40%, and the sperm percentage with abnormal morphology ≤ 14%. The preparation was performed by discontinue density gradient centrifugation and used for insemination with a concentration of 0.1–0.2 × 106 after incubating COCs for 2–6 h.

Assessment of fertilization was carried out at 16–18 h after insemination according to the presence of two pronuclei and a second polar body. The zygotes were cultured in G-1™ PLUS medium (10128, Vitrolife, Sweden) for 3 days and then transferred into G-2™ PLUS medium (10132, Vitrolife, Sweden) for another 3 days. Embryo morphology and quality were evaluated according to Gardner’s criteria [25], considering the cell quality, blastomere number and the amount of anucleate fragmentation.

Untargeted metabolomic analysis of follicular fluid

For metabolomic analysis, 19, 18 and 19 follicular fluid samples were collected from low-altitude, middle-altitude and high-altitude groups. During oocyte retrieval, follicular fluids were taken from a woman’s first follicle with a single lumen oocyte retrieval needle (C-351760-SL, Pacific Contrast Scientific Instruments, China). Once the oocytes were picked up, the follicular fluid was centrifuged at 1000 g for 20 min at room temperature to separate the supernatant and pellet. The resulting aliquots were transported to the Shanghai Applied Protein Technology Co., Ltd. for liquid chromatography triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC–MS/MS). To extract metabolites, cold extraction solvent methanol/acetonitrile/H2O (2:2:1, v/v/v) was added and adequately vortexed. After resting on ice for 20 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was vacuum-dried at 4 °C. For LC–MS analysis, the samples were redissolved in 100 μL of acetonitrile/water (1:1, v/v). The extracts were separated by Agilent 1290 Infinity LC Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Primary and secondary spectra were collected using AB Sciex TripleTOF 6600 Mass spectrometer. Raw data were converted into MzXML files through ProteoWizard. The data were analyzed by the XCMS software (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, USA) for peak alignment, retention time correction and area extraction. The metabolites were identified by MS/MS using an in-house database established with authentic standards.

The principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to distinguish the differences between the two groups and the unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine significance of difference. The variable influence on projection (VIP) > 1 and P < 0.05 was set as significant. The functional enrichment was performed by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis using MetaboAnalyst.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are expressed as the mean and standard deviation. Statistical analysis was conducted by one-way ANOVA and the Tukey’s test using the general linear model using SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, USA). Differences were considered to be significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

To shed light on the effect of high-altitude hypoxia on human oocyte quality, clinical data from a total of 315 women were assigned to low-altitude group (n = 138), middle-altitude group (n = 100) and high-altitude group (n = 77) according to their residence altitudes. Most clinical features were consistent across all three groups, including age, infertility time and the main reproductive hormone level, which provides the basis for the further experiments. Although higher doses of GnRH were given to women from high-altitude group (P = 0.036), their administration time and antral follicle count (AFC) were similar with women from other two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical data of women from different altitudes [± s, M (P25, P75)]

| Items | Low-altitude (n = 138) | Middle-altitude (n = 100) | High-altitude (n = 77) | F/H value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 30.60 ± 3.62 | 30.65 ± 3.14 | 30.86 ± 3.03 | 0.151 | 0.860 |

| Infertility time (m) | 32.93 ± 14.29 | 33.47 ± 15.45 | 35.31 ± 16.28 | 0.662 | 0.537 |

| FSH (IU/L) | 7.54 ± 2.08 | 7.35 ± 3.71 | 7.94 ± 3.21 | 0.891 | 0.411 |

| LH (IU/L) | 3.93 (3.05, 5.01) | 4.27 (3.53, 5.49) | 4.24 (2.96, 8.18) | 0.338 | 0.845 |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 34.00 (27.00, 38.00) | 33.00 (30.25, 47.50) | 30.00 (29.00, 42.00) | 0.630 | 0.730 |

| P (ng/ml) | 0.46 (0.34, 0.68) | 0.48 (0.26, 0.69) | 0.55 (0.28, 0.87) | 0.687 | 0.709 |

| PRL (ng/ml) | 13.03 ± 5.48 | 12.36 ± 5.30 | 13.24 ± 6.01 | 0.653 | 0.521 |

| T (ng/ml) | 0.35 (0.27, 0.43) | 0.39 (0.25, 0.50) | 0.32 (0.27, 0.44) | 2.671 | 0.263 |

| GnRH amount (IU) | 2196.36 ± 734.48b | 2137.88 ± 517.30b | 2400.16 ± 807.70a | 3.362 | 0.036 |

| GnRH time (d) | 10.36 ± 2.14 | 10.35 ± 1.77 | 10.68 ± 1.99 | 0.761 | 0.468 |

| AFC | 14.43 ± 7.84 | 16.10 ± 6.69 | 14.73 ± 6.48 | 1.658 | 0.192 |

Different letters indicate significant differences with P < 0.05

Effect of altitude change on female IVF outcomes

There were 1970, 1543 and 1058 oocytes obtained from oocyte recovery procedure in three groups, respectively. Unexpectedly, more MI oocytes were found in the middle-altitude group (P = 0.013). However, no significant difference was found on the average number of obtained oocytes (P = 0.370) and MII oocytes (P = 0.556) over the study period. The similar maturing rates were counted in three groups (P = 0.135), implying that the oocyte maturation was not severely affected by residence altitudes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Oocyte maturation of women from different altitudes [± s, M (P25, P75), %]

| Items | Low-altitude (n = 138) | Middle-altitude (n = 100) | High-altitude (n = 77) | F/H/χ2 value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obtained oocyte | 14.28 ± 8.98 | 15.43 ± 8.09 | 13.74 ± 7.29 | 0.997 | 0.370 |

| MII oocyte | 12.99 ± 8.53 | 13.76 ± 7.48 | 12.52 ± 6.69 | 0.588 | 0.556 |

| MI oocyte | 0 (0, 1)b | 1 (0, 3)a | 0 (0, 1)b | 8.638 | 0.013 |

| GV oocyte | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.611 | 0.737 |

| Maturing rate (%) | 90.96 (1792/1970) | 89.18 (1376/1543) | 91.12 (964/1058) | 4.005 | 0.135 |

Different letters indicate significant differences with P < 0.05

In the IVF experiment, 1792, 1376 and 964 oocytes were used with normal sperm. As before, the differences of fertilized oocyte numbers (P = 0.788) and fertility rates (P = 0.156) were not obvious among three groups. Furthermore, the change of residence altitudes did not cause the increment of 1 PN and multiple PN zygotes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Fertilization ability of oocytes in women from different altitudes [± s, M (P25, P75), %]

| Items | Low-altitude (n = 138) | Middle-altitude (n = 100) | High-altitude (n = 77) | F/H/χ2 value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilized oocyte | 11.45 ± 8.02 | 11.04 ± 5.40 | 10.81 ± 6.38 | 0.239 | 0.788 |

| 2 PN zygote | 10.12 ± 6.83 | 9.88 ± 4.55 | 10.19 ± 6.02 | 0.072 | 0.930 |

| 1 PN zygote | 0 (0, 1)ab | 0 (0, 1)b | 0 (0, 1)a | 7.261 | 0.027 |

| Multiple PN zygote | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | 1.650 | 0.438 |

| Fertility rate (%) | 77.96 (1397/1792) | 71.80 (988/1376) | 81.43 (785/964) | 3.709 | 0.156 |

Different letters indicate significant differences with P < 0.05

For clarifying the subsequent developmental potential of oocytes obtained from women in different groups, the embryo development was traced. The result showed that the effect of high-altitude hypoxia on embryo development happened in blastocyst stage, but not in the cleavage stage. The main indicators, including high-quality embryo rate, formative blastocyst number, blastocyst rate, available blastocyst number and available blastocyst rate, revealed a trend of gradual decrease with the elevation of residence altitudes (P < 0.05, Table 4). All these demonstrate that although the oocyte maturation and fertility seem normal in different groups, the damage of high-altitude hypoxia on embryo development is not negligible.

Table 4.

Embryonic development ability of patient population [± s, M (P25, P75), %]

| Items | Low-altitude (n = 138) | Middle-altitude (n = 100) | High-altitude (n = 77) | F/H/χ2 value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleavage embryo | 9.79 ± 6.42 | 9.26 ± 4.18 | 9.22 ± 5.20 | 0.385 | 0.681 |

| Cleavage rate (%) | 85.29 (1351/1584) | 83.88 (926/1104) | 85.34 (710/832) | 1.206 | 0.547 |

| High-quality embryo | 5.38 ± 3.25 | 5.06 ± 2.35 | 4.47 ± 3.03 | 2.367 | 0.095 |

| High-quality embryo rate (%) | 53.11 (742/1397)a | 51.21 (506/988)a | 43.82 (344/785)b | 17.926 | < 0.001 |

| Formative blastocyst | 3 (2, 4)a | 2 (0, 4)b | 1 (0, 2)c | 32.631 | < 0.001 |

| Blastocyst rate (%) | 62.96 (391/621)a | 57.47 (223/388)ab | 53.15 (118/222)b | 7.459 | 0.024 |

| Available blastocyst | 2 (2, 3)a | 2 (0, 3)b | 1 (0, 2)c | 42.724 | < 0.001 |

| Available blastocyst rate (%) | 53.62 (333/621)a | 47.42 (184/388)ab | 41.44 (92/222)b | 10.660 | 0.005 |

Different letters indicate significant differences with P < 0.05

Feature annotation of female follicular fluid

For chemical annotation of metabolic features, significant features were matched with authentic standards (level-2 evidence) by comparing their molecular weights and retention times [26]. Those with molecular weight differed by more than 10 ppm and retention time differed by more than 30 s were excluded. If features matched to multiple metabolites based on molecular weight and retention time, we chose those with the closest retention times. Only those with high-quality peaks were considered as high-quality matches to further minimize false positive matches.

Based on the Human Metabolome Database 5.0 [27], we identified the superclass and class of each matched metabolite. A total of 1193 unique features were observed in the follicular fluid metabolome after data quality assurance, of which 722 positive and 471 negative ion modes, which belonged to 14 superclasses and 89 classes. Most metabolites were enriched in lipids and lipid-like molecules, organic acids and derivatives, organoheterocyclic compounds, and benzenoids (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chemical classifications of metabolites in female follicular fluid

Effects of female residence altitude on follicular fluid metabolome

The differences between different groups were calculated by principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). As shown in Fig. 2A–C, the distinct separations were found in all the three comparisons. It implies that the change of residence altitude can affect the global metabolic pattern of female follicular fluid. The differential metabolites were preliminarily screened with fold change less than 0.67 or more than 1.50 and P value less than 0.05. There were 95 (43 up and 52 down), 166 (65 up and 101 down) and 145 (44 up and 101 down) metabolites found in middle-altitude vs. low-altitude, high-altitude vs. low-altitude, and high-altitude vs. middle-altitude comparisons (Fig. 2D–F).

Fig. 2.

The metabolome analysis of follicular fluid in women from different groups. A–C OPLS-DA score graphs of middle-altitude vs. low-altitude (A), high-altitude vs. low-altitude (B), and high-altitude vs. middle-altitude (C). D–F Volcano Maps of metabolic differences in middle-altitude vs. low-altitude (D), high-altitude vs. low-altitude (E), and high-altitude vs. middle-altitude (F)

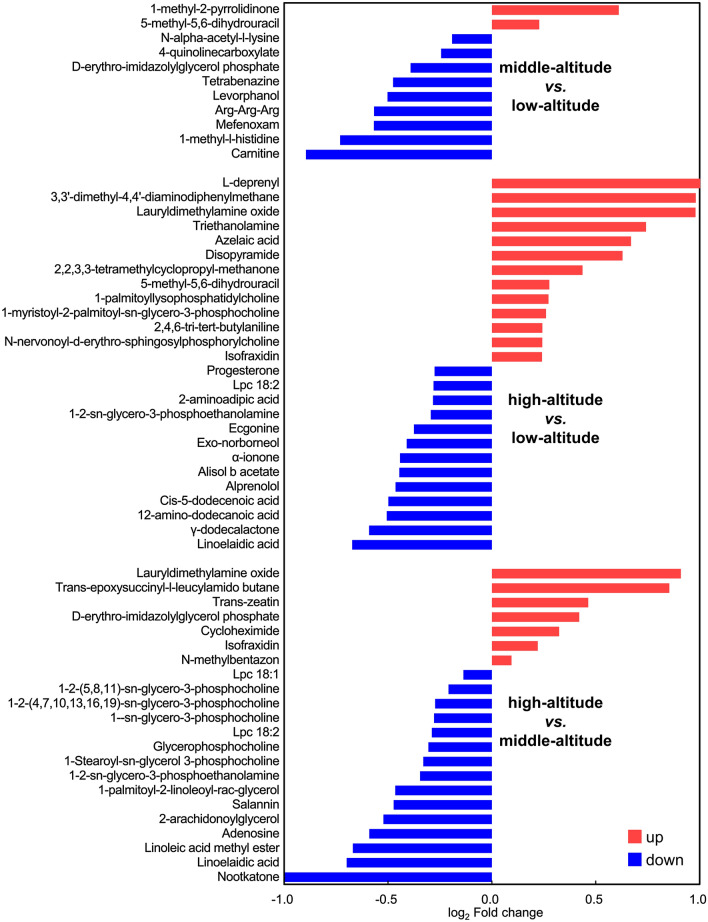

Differential metabolites were further chosen with OPLS-DA VIP > 1. We obtained 19, 52 and 39 differential metabolites in three comparisons respectively. The representative features are listed in Fig. 3. Furthermore, the metabolites with differences in at least two comparisons were deemed essential to the response of follicular fluid to hypoxic environment.

Fig. 3.

Multiple comparison of differential metabolites in follicular fluid from middle-altitude vs. low-altitude, high-altitude vs. low-altitude, and high-altitude vs. middle-altitude

For example, linoelaidic acid, an unsaturated fatty acid critical for female reproduction, was significantly downregulated in high-altitude group compared with low-altitude and middle-altitude groups. So did carnitine, an important participator in fatty acid oxidation, which was higher in low-altitude group than other two groups (Fig. 4A). KEGG enrichment analysis showed that differential metabolites between middle-altitude and low-altitude groups were enriched in histidine and cholesterol metabolism (Fig. 4B), and differential metabolites between high-altitude and middle-altitude groups were related with protein digestion and absorption, neuroactive ligand receptor interaction, and cGMP-PKG pathway (Fig. 4D). Even more striking, differential metabolites between high-altitude and low-altitude groups exhibited a clear correlation with oocyte meiosis, progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation, and steroid biosynthesis (Fig. 4C). The above results demonstrated that residence altitude can significantly change the metabolic components of female follicular fluid, which should be one of the important reasons of impaired oocyte developmental potential.

Fig. 4.

Key differential metabolites and metabolic pathways among low-altitude, middle-altitude, and high-altitude group. A Representative differential metabolites which were different in at least two comparisons. B–D KEGG pathway analyses of differential metabolites from middle-altitude vs. low-altitude (B), high-altitude vs. low-altitude (C), and high-altitude vs. middle-altitude (D)

Discussion

During the lifespan of mammals, oocyte is the beginning and foundation of intricate fetal development. Whether normal in vivo development by mating [28] or in vitro development through assisted reproductive technology [29], oocyte quality is always the core of successful fertilization and embryo development. Undoubtedly, this involves multiple controlling factors, including chromosome assembly [30], secreted factors [31], and mitochondrial function [32]. However, there are still imperceptible defects difficult to be detected clinically, which could have great long-term influence on embryo quality and fetal health through genetic and epigenetic patterns [33, 34]. This leads to the problem that some oocytes seem like high-quality cells based on morphological and routine tests, which could fail to support the normal full-term development after fertilization [35, 36]. In our study, the clinical data of women from different altitudes indicated that the serum hormone levels of women had suffered no obvious impact by residence altitude, so had oocyte maturing rate and fertility rate. Nonetheless, serious problem started to emerge during early embryo development. The embryo quality and blastocyst formation were significantly damaged in women from high-altitude area, the high-quality embryo rate, blastocyst rate and available blastocyst rate fall sharply by 9.29%, 9.81% and 12.18% respectively. It implies that oocyte could have certain defects which cannot be determined by simple clinical morphological diagnosis.

Oocyte developmental potential is brought about by numerous endogenous and exogenous factors. A series of genetic determinants about oocyte abnormalities have been excavated [37], such as ZP3, CDC20 and TUBB8. However, the genetic test can only predict reproductive diseases caused by gene mutation without assessing oocyte status. Transcription factors are the most direct effectors orchestrating oocyte function [33], some key oocyte-secreted factors, GDF9 and BMP15, have been affirmed through exogenous supplement experiment [31] but are still far away from clinical practice. Therefore, a great deal of research is focused on finding new noninvasive landmark of oocyte quality [38–40]. In particular, intrafollicular condition as a major link between maternal metabolism and oocyte quality [41], is considered as one of the most potential indicators, massive efforts are put into deciphering the composition and function of follicular fluid.

Compared with targeted analyses, untargeted metabolomics allows uncover as many assortments of metabolites as possible without necessarily identifying or quantifying a particular compound [42]. Our analysis revealed the metabolic difference in women caused by the change of residence altitude, including fatty acids, lysophospholipids, steroids and other substances. The enrichment analysis of KEGG annotation on metabolic pathways showed that there were significant differences in amino acid metabolism, cholesterol metabolism, protein digestion and absorption, steroid biosynthesis, oocyte meiosis, progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation, neural active ligand–receptor interaction and cGMP-PKG pathway. These differential metabolites and metabolic pathways are closely related to oocyte quality, and some factors have been shown to affect oocyte and embryo development. The unbalanced concentration of various fatty acids was found in follicular fluid of women from high-altitude area, which has been proven to be crucial for oocyte competence [43]. Several key differential metabolites have been found to be relevant to compromised fertilization and embryo development, including oleic acid, linoleic acid, palmitate, dodecanoic acid, dodecenoic acid, pentadecanoic acid, and prostaglandin f2β. Another important factor is lysophosphatidylcholine (Lpc), which was downregulated with increased elevation. Previous study confirms that Lpc can promote granular cell growth and oocyte maturation by activating nitric oxide and extracellular signal-regulated kinases [44]. Amino acid is the basis of protein synthesis, and the digestion and absorption processes are closely related with hormone level and ovarian function [45]. A series of key amino acids were reduced sharply, including histidine, lysine, arginine, phenylalanine, and methionine. These substances can provide security for oocyte maturation and lay a good foundation for subsequent embryo development. Considering the possibility of clinical application, the concentrations of several key metabolites can be detected in follicular fluid after COC retrieval, such as lauryldimethylamine oxide, isofraxidin, linoelaidic acid, and Lpc. These indicators could be helpful for evaluation of oocyte developmental potential.

In summary, our results provide insight for deciphering the key characteristics of follicular fluid in women from different residence altitudes. The study sheds new light on our understanding of the effect of high-altitude hypoxia on female oocyte development. The excavation of potential regulative metabolites can be used as a reference for estimating female oocyte development at high altitudes. It will have potential benefits toward exploring the addition of key metabolites on personalized treatment plan for women living at high altitudes in assisted reproductive cycle.

Author contributions

ZFX conceived the study and designed the experiments. XLL and QDW performed the study and contributed to the data collection. ZFX wrote the manuscript. ZFX and XLL contributed to the critical revision of article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Western Light Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences and Qinghai Kunlun Talents Program in 2020.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qinghai Provincial People’s Hospital (2021–69).

Consent to participate

Informed consents were obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Giudice LC (2006) Infertility and the environment: the medical context. Semin Reprod Med 24(3):129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson SA, Kallen AN (2021) Diagnosis and management of infertility: a review. JAMA 326(1):65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaskins AJ, Chavarro JE (2018) Diet and fertility: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 218(4):379–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2018) Electronic address, a.a.o. and M. practice committee of the American society for reproductive, smoking and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 110(4):611–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaskins AJ et al (2021) Impact of ambient temperature on ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril 116(4):1052–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanbo T, Abyholm T (1991) Assisted reproductive technology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 3(5):649–655 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szamatowicz M (2016) Assisted reproductive technology in reproductive medicine–possibilities and limitations. Ginekol Pol 87(12):820–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham ME et al (2023) Assisted reproductive technology: short- and long-term outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol 65(1):38–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combelles CM, Racowsky C (2005) Assessment and optimization of oocyte quality during assisted reproductive technology treatment. Semin Reprod Med 23(3):277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vollenhoven B, Hunt S (2018) Ovarian ageing and the impact on female fertility. F1000Res 7:1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jankovic Velickovic L, Stefanovic V (2014) Hypoxia and spermatogenesis. Int Urol Nephrol 46(5):887–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fajersztajn L, Veras MM (2017) Hypoxia: from placental development to fetal programming. Birth Defects Res 109(17):1377–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Anguita N et al (2022) Hypoxia induces an early primitive streak signature, enhancing spontaneous elongation and lineage representation in gastruloids. Development. 10.1242/dev.200679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wray S, Alruwaili M, Prendergast C (2021) Hypoxia and reproductive health: hypoxia and labour. Reproduction 161(1):F67–F80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimamoto S et al (2019) Hypoxia induces the dormant state in oocytes through expression of Foxo3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116(25):12321–12326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang W et al (2021) Hypoxic in vitro culture reduces histone lactylation and impairs pre-implantation embryonic development in mice. Epigenetics Chromatin 14(1):57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritchie HE, Oakes DJ, Kennedy D, Polson JW (2017) Early gestational hypoxia and adverse developmental outcomes. Birth Defects Res 109(17):1358–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molinari E, Bar H, Pyle AM, Patrizio P (2016) Transcriptome analysis of human cumulus cells reveals hypoxia as the main determinant of follicular senescence. Mol Hum Reprod 22(8):866–876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson JG, Brown HM, Kind KL, Russell DL (2015) The ovarian antral follicle: living on the edge of hypoxia or not? Biol Reprod 92(6):153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fahiminiya S, Gerard N (2010) Follicular fluid in mammals. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 38(6):402–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azari-Dolatabad N et al (2021) Follicular fluid during individual oocyte maturation enhances cumulus expansion and improves embryo development and quality in a dose-specific manner. Theriogenology 166:38–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C et al (2021) Proteomic analysis of the alterations in follicular fluid proteins during oocyte maturation in humans. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 12:830691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu JC, Huang YF, Lu NQ (2010) WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen: its applicability to andrology laboratories in China. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 16(10):867–871 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stimpfel M, Jancar N, Vrtacnik-Bokal E, Virant-Klun I (2019) Conventional IVF improves blastocyst rate and quality compared to ICSI when used in patients with mild or moderate teratozoospermia. Syst Biol Reprod Med 65(6):458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner DK, Stevens J, Sheehan CB, Schoolcraft WB (2007) Analysis of blastocyst morphology. Human preimplantation embryo selection. Informa Healthcare, London, pp 79–88 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sumner LW et al (2007) Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis chemical analysis working group (CAWG) metabolomics standards initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 3(3):211–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wishart DS et al (2022) HMDB 5.0: the human metabolome database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res 50(1):D622–D631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keefe D, Kumar M, Kalmbach K (2015) Oocyte competency is the key to embryo potential. Fertil Steril 103(2):317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Homer HA (2020) The role of oocyte quality in explaining “unexplained” infertility. Semin Reprod Med 38(1):21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Severson AF, von Dassow G, Bowerman B (2016) Oocyte meiotic spindle assembly and function. Curr Top Dev Biol 116:65–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilchrist RB, Lane M, Thompson JG (2008) Oocyte-secreted factors: regulators of cumulus cell function and oocyte quality. Hum Reprod Update 14(2):159–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirillova A, Smitz JEJ, Sukhikh GT, Mazunin I (2021) The role of mitochondria in oocyte maturation. Cells 10(9):2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamazaki N et al (2021) Reconstitution of the oocyte transcriptional network with transcription factors. Nature 589(7841):264–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang X, Ma J, Schatten H, Sun Q (2012) Epigenetic changes associated with oocyte aging. Sci China Life Sci 55(8):670–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassil R et al (2021) Can oocyte diameter predict embryo quality? Reprod Sci 28(3):904–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruebel ML, Latham KE (2020) Listening to mother: long-term maternal effects in mammalian development. Mol Reprod Dev 87(4):399–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sang Q, Zhou Z, Mu J, Wang L (2021) Genetic factors as potential molecular markers of human oocyte and embryo quality. J Assist Reprod Genet 38(5):993–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turathum B, Gao EM, Chian RC (2021) The function of cumulus cells in oocyte growth and maturation and in subsequent ovulation and fertilization. Cells 10(9):2292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goovaerts IG, Leroy JL, Jorssen EP, Bols PE (2010) Noninvasive bovine oocyte quality assessment: possibilities of a single oocyte culture. Theriogenology 74(9):1509–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Q, Sun QY (2007) Evaluation of oocyte quality: morphological, cellular and molecular predictors. Reprod Fertil Dev 19(1):1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leroy JL et al (2011) Intrafollicular conditions as a major link between maternal metabolism and oocyte quality: a focus on dairy cow fertility. Reprod Fertil Dev 24(1):1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hood RB et al (2023) Serum and follicular fluid metabolome and markers of ovarian stimulation. Hum Reprod 38(11):2196–2207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng Y et al (2022) Follicular free fatty acid metabolic signatures and their effects on oocyte competence in non-obese PCOS patients. Reproduction 164(1):1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sriraman V et al (2008) Identification of ERK and JNK as signaling mediators on protein kinase C activation in cultured granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 294(1–2):52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang J et al (2019) The genetic mechanism of high prolificacy in small tail han sheep by comparative proteomics of ovaries in the follicular and luteal stages. J Proteomics 204:103394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.