Abstract

Background and Objectives

Tirzepatide is a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, which was approved in 2023 by the US Food and Drug Administration for weight management in adults with obesity or overweight. The purpose of this study was to conduct qualitative exit interviews with participants who had participated in the SURMOUNT-4 clinical trial, to better understand the patient experience of tirzepatide.

Methods

Online exit interviews were conducted with adults from the USA who had participated in the SURMOUNT-4 clinical trial for weight management, recruited from 16 US-based SURMOUNT-4 clinical sites. Interviews utilized a semi-structured interview guide, and included questions related to receiving tirzepatide, using a single-use injection pen device, and the overall trial experience. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed, and analyzed using a content analysis.

Results

Eighty-six adults (83% female; mean age 49.9 years) participated in the interviews. All participants shared at least one perceived benefit of tirzepatide experienced during the open-label phase of SURMOUNT-4, including improved appetite control, increased energy, or improved clothing fit. Despite the gastrointestinal side effects experienced, many participants liked the efficacy of tirzepatide, and reported that the single-use injection pen device for administering the study medication was easy to use. Most participants were willing to continue taking tirzepatide.

Conclusions

Study findings showed that beyond the direct pharmacological effects of treatment with tirzepatide, participants reported a wide range of perceived improvements across several aspects of their lives. Participants also reported a few negative experiences, including side effects. It is possible that the participants who had a more positive experience were more inclined to participate in the exit interviews. This study highlights the value of exit interviews, which can provide more learning about patient experiences during a clinical trial.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40271-025-00730-0.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| This exit interview study provides new insights into the perceived benefits of pharmacologic treatment for weight management from the patient perspective. |

| In addition to weight loss, participants noted a number of additional positive changes including increased energy, better physical functioning, improved emotional well-being, and enhanced social life. |

| These findings indicate the meaningful impact of tirzepatide on patients’ lives, complementing clinical trial results. |

Background

Obesity is a chronic disease, and its increasing prevalence [1] is a public health concern as it is associated with a rising incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, an increased risk for premature death, and an increased risk for some cancers [2–4]. A 5–10% loss of body weight through approaches such as calorie restriction, physical activity, and behavioral therapy has been shown to reduce obesity-related cardiovascular risk factors, and in some cases, improve health-related quality of life [5–7]. However, lifestyle therapies alone fail to achieve sustainable weight loss in most individuals living with obesity [8], both because of biological mechanisms, such as decreased metabolism caused by weight loss, or increased appetite due to decreased leptin [9], and additional factors such as a loss of motivation (e.g., to engage in physical activity), low self-confidence, or psychosocial stressors [10].

Tirzepatide is a treatment that targets glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors, delivered as a weekly injection. Tirzepatide has demonstrated safety and efficacy in multiple phase III studies in adults living with obesity or overweight, to support weight loss and weight maintenance [11–15], and is approved in the USA, European Union, and other countries for weight management in adults with obesity or overweight and weight-related comorbidities [16].

One of the phase III trials, SURMOUNT-4, enrolled 783 participants living with obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30), or overweight (BMI ≥ 27) with at least one weight-related comorbidity (excluding diabetes mellitus) [15]. All participants received 36 weeks of tirzepatide in an open-label lead-in treatment phase, and then were randomized to continue tirzepatide or switch to placebo for an additional double-blind treatment phase of 52 weeks. This was followed by a 4-week safety follow-up period. The mean weight reduction between week 0 and 88 was 25.3% for those randomized to continue tirzepatide, versus 9.9% for those who switched to placebo, demonstrating the efficacy of tirzepatide in this trial population. Additionally, quantitative findings indicated significant improvements in physical functioning and mental health in participants who continued taking tirzepatide relative to those who switched to placebo [15].

While clinical trials can provide quantitative insights into the efficacy and safety of a treatment, an endpoint analysis does not necessarily offer deep insights into the lived experiences of trial participants or provide context into whether treatment-related changes are meaningful. Exit interviews, completed at the end of a clinical trial, are recommended as a means to obtain further qualitative insights into the patient experience [17–19] and help to increase the interpretability of quantitative trial results [20, 21]. For instance, exit interviews conducted after previous clinical trials of tirzepatide for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-2 and SURPASS-3) indicated that the treatment benefits observed, such as improved glycemic control, weight loss, and increased energy levels, were important to participants. Furthermore, the exit interviews provided detailed qualitative insights into the broader benefits experienced by participants, such as an improved ability to exercise, complete daily activities, and work [21]. Therefore, this non-interventional, qualitative exit interview study was designed to understand the experience of participants with obesity or overweight, without diabetes, who had participated in SURMOUNT-4, to learn more about their experiences with receiving tirzepatide, and their experiences using a single-use injection pen device to administer the study medication.

Methods

Study Overview

This non-interventional, cross-sectional, qualitative exit interview study involved one-to-one online interviews lasting up to 90 minutes with adults who had participated in the SURMOUNT-4 clinical trial. All participants provided written informed consent before taking part in an interview, and received an honorarium for their time upon completion of the interview.

Participants

The target sample size was 20% of the overall enrolled SURMOUNT-4 population, which was selected to maximize the likelihood of adequate representation of both placebo and tirzepatide participants, as the trial arm was blinded during recruitment. Convenience sampling was used to recruit adults (aged ≥18 years) who had participated in SURMOUNT-4 in the USA [15]; further information on the SURMOUNT program is published elsewhere [11, 15].

Interview participants were recruited from 16 US clinical sites during or after their SURMOUNT-4 week 88 primary endpoint visit. Participants were eligible for an interview once they had completed their week 92 safety follow-up. Trial participants who had discontinued the trial or the study medication after week 36 were also eligible to be interviewed. The research team and participants were blinded to the treatment arm at the time of the interview.

Data Collection

Qualitative Interview Data

Qualitative interviews were conducted remotely using web-assisted software by experienced interviewers. Semi-structured interview guides were used, which included open-ended concept elicitation questions and probes to explore each participant’s experience receiving tirzepatide, using the single-use injection pen device, and their overall trial experience. Participants were also asked about any perceived treatment benefits and negative impacts experienced during the open-label and blinded phases of SURMOUNT-4.

Demographic Data

Clinical characteristics were shared from the SURMOUNT-4 clinical trial database for the patients who participated in an exit interview, following a trial database lock and unblinding. In addition, recruiting sites completed a demographic form for each participant.

Analysis

Unique identifiers were used to anonymize interview participants. Participant IDs took the form: site number—recruitment order—gender—treatment arm (where TZP represents tirzepatide and PB represents placebo). The suffix -D was added to the IDs of any participants who discontinued the trial or discontinued the study medication.

Qualitative Analysis

Audio recordings from the qualitative interviews were transcribed verbatim, redacted, and analyzed in ATLAS.ti (version 9) using a directed content analysis for concept elicitation techniques, [22, 23] by experienced coders. A preliminary codebook was developed to structure the coding in line with the research objectives, and codes were then extended and revised to align inductively with the data. The coding process was iterative, with several rounds of review and discussion within the research team to ensure that codes were applied consistently. A content analysis was selected to allow for manifest level analyses, where participant language was used in the name of each code, and the final code list (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]) became the final list of concepts, without additional levels of interpretation and abstraction. This approach was chosen as it enables the description of participant experiences from a realist perspective and allows frequencies to be calculated and reported, and best aligns with the study objective to understand the experience of participants in SURMOUNT-4.

Conceptual saturation refers to the point at which gathering more data about a construct is unlikely to provide new information to address the research question, [24] and is used to evaluate whether a sample size is sufficient in qualitative research, based on the data collected. Saturation was assessed for the total sample of participants in accordance with recognized methods [25, 26] and industry guidance, [24] and was evaluated at the domain level, owing to the quantity of data collected. Interview transcripts were grouped into nine sets in the sequential order that interviews were performed (eight sets of ten, and one set of six), and elicited concepts were compared between sets to identify which set each domain was first spontaneously reported in, and whether any new data was reported in the final set.

Quantitative Analysis

SURMOUNT-4 clinical data and responses to the site-completed demographic forms were summarized with descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, and range for continuous data; frequencies and percentages for categorical data).

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 86 patients participated in a qualitative exit interview between February and August 2023. Interviews were conducted, on average, 37 days after the week 92 safety visit (standard deviation: 27 days). Two interview participants had discontinued the trial treatment early but continued to attend SURMOUNT-4 study visits. Both discontinuers explained that they had stopped taking the trial treatment as they believed they had been assigned to placebo following randomization and were disappointed to not still be receiving tirzepatide. The remaining 84 participants completed all study treatment doses and study visits.

The average age of interview participants was 49.9 years (standard deviation = 13.2 years), and the majority were female (n = 71/86, 83%), White (n = 69/86, 81%), and did not identify as Hispanic or Latino (n = 75/86, 87%). Additional demographic and clinical data are shared in Table 4 of the ESM.

Based on SURMOUNT-4 unblinded data after the exit interviews were completed, 50 (58%) exit interview participants were randomized to tirzepatide, and 36 (42%) were randomized to placebo in the double-blind phase of the trial. During the open-label phase when all participants were taking tirzepatide, interview participants lost an average of 24.7 kg, or 22.6% of their start body weight. On average, weight continued to decrease in the group randomized to continue tirzepatide, while weight increased in the group that switched to placebo (see Table 1), which aligns with the broader SURMOUNT-4 population findings [15].

Table 1.

Exit interview participant weight during SURMOUNT-4

| Time point | Full sample | Tirzepatide (N = 50) | Placebo (N = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean weight in kg, mean (SD) | |||

| Week 0 | 110.9 (22.2) | 111 (21.3) | 110.7 (23.6) |

| Week 36 | 86.2 (21.2) | 86.4 (20.7) | 86 (22.1) |

| Week 88 | 88.1 (25.6) | 80.1 (22.9) | 99.2 (25.0) |

| Weight change, week 0 to week 36 | |||

| Mean (SD) change in kg | − 24.7 (8.6) | − 24.7 (7.7) | − 24.7 (9.8) |

| Mean (SD) % change | − 22.6% (7.4) | − 22.6% (7.1) | − 22.3% (8.0) |

| Weight change, week 36 to week 88 | |||

| Mean (SD) change in kg | + 1.9 (13.1) | − 6.3 (9.1) | + 13.1 (8.7) |

| Mean (SD) % change | + 2.2% (15.4) | − 7.7% (10.1) | + 15.8% (10.1) |

kg kilogram, SD standard deviation

Saturation

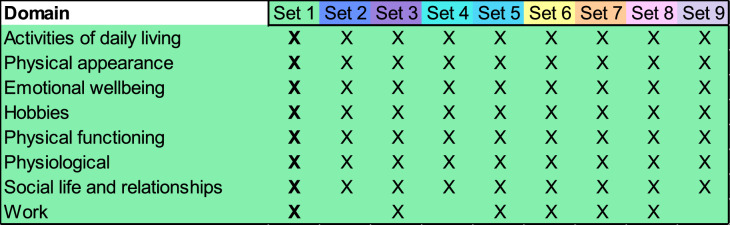

Eight domains were identified when coding the participant experience of tirzepatide. All eight domain-level impacts were spontaneously reported in Set 1 (of nine sets), and so conceptual saturation was achieved. Saturation results, reported at the set level because of the large number of interviews completed, are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Saturation analysis results, where saturation was achieved in Set 1, where Set 1–Set 8 consisted of ten interviews each, and Set 9 consisted of the final six interviews

Tirzepatide Experience

As interviews were semi-structured, not all questions were asked to all participants, therefore counts may not always equate to the total sample size.

Perceived Treatment Benefits and Impacts

All 86 participants reported that they had experienced weight loss during the open-label (pre-randomization) phase where all trial patients received tirzepatide. Aside from weight loss, participants reported many additional changes during this phase, categorized as a perceived treatment benefit if a concept had improved, or a negative impact if a concept had worsened. These experiences were categorized into eight domains: physiological, physical appearance, physical functioning, emotional well-being, social life and relationships, activities of daily living, work, and hobbies.

The most frequently reported positive and negative experiences are presented in Table 2. All other perceived benefits and negative impacts reported during the open-label phase of SURMOUNT-4 are listed in Table 5 onwards of the ESM. Participants also reported several side effects, presented in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Treatment benefits and negative impacts reported by participants during the open-label phase of SURMOUNT-4

| Domain | Experience | Count (N = 86) | Quote(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived treatment benefits | |||

| Physiological | Weight loss | 86 |

“I definitely had started losing weight, um, in those first 36 weeks.” (S5-37-F-TZP) “My weight came off very quickly, I mean, within, within the first, I mean, four weeks.” (S1-05-M-PB) |

| Physiological | Appetite decrease | 78 |

“Almost immediately, it suppressed my appetite. I would be eating and then suddenly get full and stop, where I’ve never experienced that in the past.” (S10-14-M-PB) “I felt like I responded quickly when I initially started it, as far as having, um, a decrease in my appetite, um, eating smaller portions, just because I wasn’t able to eat very much, jus-just due to feeling fuller.” (S2-36-F-TZP) |

| Physiological | Energy level increase | 53 |

“My body goes in cycles, like, as the day gets darker, you know, there’s less light, then I get tired more and don’t have as much energy. But I, I noticed during—while I was taking the medicine, the entire time, I had, err, lots of energy.” (S11-60-F-TZP) “Err, within the first 36 week, yes, there were changes. Like I said, um, I were getting more energy because I’m shedding weight. I wasn’t so lazy anymore.” (S1-76-F-TZP) |

| Physical appearance | Improved clothing fit | 49 |

“Well, you know, when you’re continually gaining weight, you find yourself having to, you know, adjust to the size. You can sometimes find yourself buying more clothes and before you know it, you have a whole new size of clothes.” (S14-93-M-PB) “I pulled out clothes I haven’t wore since before having my kids, and they actually fit me.” (S3-75-F-TZP) |

| Emotional well-being | Increased positivity | 47 |

“[I experienced] less depression, not that I had—I, I didn’t have significant depression to begin with, but just less feelings of feeling down.” (S2-36-F-TZP) “I just felt a lot more positive.” (S3-64-F-PB-D) |

| Emotional well-being | Increased confidence | 41 |

“Like, I lost weight, um, I gained confidence back, um, just overall a happier person, um, participating in all types of, um, situations.” (S14-90-F-TZP) “No, I mean, it was, it was great. Um, I, I had confidence, um, I, I felt very good and, and happy about what I was doing and, and the direction I was heading in.” (S13-732-F-PB) |

| Physical functioning | Improved walking | 36 |

“... some of the [...] impact was just with, you know, being able to have be-better stamina and walk without, you know, being winded or, um, you know, keep up with other people’s pace.” (S14-88-F-PB) “But I think by month two, I realized that I was walking better, walking further.” (S6-83-F-TZP) |

| Perceived negative impacts | |||

| Physiological | Loss of muscle tone | 3 | “I guess the only negative would’ve been I probably lost some strength. Err, I-I’m pretty active physically. I play a lot of what, err, what we call here as senior softball, and I probably lost some of my batting power, err, until we got to the end of the program.” (S6-69-M-PB) |

| Physical appearance | Increased loose skin | 3 | “The only bad thing is, um, like, my arms got a little more, um, I don’t know, oh, saggy, so I’ve been trying to work on my arms.” (S13-52-F-TZP) |

| Emotional well-being | Increased anxiety/worry | 2 | “Towards the end of the 36-week period, I was starting to get a little worried about how much weight I was continuing to lose. it was, actually, kind of, funny, you know, because here all this time, I’ve been worried about I’m eating too much and trying to find the right diet and trying to lose weight. Now all of a sudden, I’m going, ‘You know, last time I checked in I lost eight more pounds’ and I’m to the point where I’m starting to worry about losing eight more pounds.” (S2-26-F-PB) |

Fig. 2.

Summary of adverse events experienced by exit interview participants during SURMOUNT-4a. aWhere ‘other’ corresponds to n = 1 each of general malaise, no/low efficacy, delayed gastric emptying, lactose intolerance, cognitive impacts, itching, gallbladder pain, neck pain, nerve pain, feeling irritable, low blood pressure, dry skin, dry hair, and unspecified liver issues

As reported in Table 2, in addition to weight loss, perceived physiological benefits included a decreased appetite (n = 78/86, 91%) and/or increased energy levels (n = 53/86, 62%). Participants reported that they wanted to eat less, or felt full more quickly when eating. One participant described a new-found sense of “eating to live, instead of living to eat” (S14-88-F-PB). In relation to their energy levels, participants reported having more energy and “not be[ing] so sluggish” (S16-96-F-TZP), noting that this had a subsequent positive effect on the number of daily activities they could complete. One participant described feeling “more awake, more alive” (S5-03-M-TZP). In contrast, one participant reported experiencing a loss of energy as they reduced their calorie intake (n = 1/86, 1%), and some reported fatigue as a side effect of tirzepatide (n = 4/86, 5%; Fig. 2).

Changes in physical appearance were frequently reported. Participants (n = 49/86, 57%) reported that their clothes either fit more comfortably or that their clothing size had changed, and also often described having positive experiences finding new clothes to wear (n = 24/86, 28%). One participant shared that they were “actually able to wear some in-style clothes” (S1-05-M-PB), while others reported that they felt more professional in work attire because of their weight loss. However, changes related to physical appearance were not always positive: for instance, three participants (n = 3/86, 4%) reported that they were left with loose skin after losing weight, which left one participant feeling “a little self-conscious” (S13-54-F-TZP), and another participant reporting that buying new clothes had been a financial burden.

Participants also reported improvements in their physical functioning, including being able to walk further, at greater speeds, or with less discomfort (n = 36/86, 42%). Changes in physical functioning were often associated with increased energy, decreased shortness of breath, and decreased pain (e.g., joint pain). Many participants also reported that their general activity levels had increased (n = 30/86, 35%), and noted that they had developed more endurance and felt more physically comfortable engaging in physical activity as they lost weight.

Aside from self-consciousness related to loose skin, and anxiety/worry related to excessive weight loss, many participants reported that their weight loss positively affected their emotional well-being, including increased positive mood (n = 47/86, 55%), and increased confidence (n = 41/86, 48%), which was frequently associated with outward behaviors such as participating in activities and events. One participant described feeling “like a whole different person, physically and mentally” (S9-43-F-TZP) when reflecting on their experience during the open-label phase.

Social life and relationships were also reported as impacted. Participants reported increased participation in social events (n = 33/86, 38%), and many noticed an increase in the number of compliments received by others (as a result of their weight change; n = 33/86, 38%). Perceived improvements in social life and relationships were often associated with positive changes in physical appearance, increased energy levels, and generally improved physical functioning. However, two participants (n = 2/86, 2%) noted that they had received negative feedback on their changing appearance, particularly that they had “lost too much weight” (S6-69-M-PB).

Despite not being reported as frequently, participants shared many additional perceived benefits related to activities of daily living, work, and hobbies/leisure time. The most frequently reported activities of daily living benefit was an improved ability to do household chores. This was often attributed to feeling “a little more energiz[ed] and rested” (S14-93-M-PB). Improved work performance was also frequently mentioned as a change that participants experienced while receiving tirzepatide (n = 15/86, 17%). Additionally, some participants reported an improved willingness or ability to engage in leisure activities (n = 5/86, 6%). Typically, these participants acknowledged that their weight loss meant they were able to participate in activities where their size had previously been a barrier, such as zip-lining or riding amusement park rides.

Adverse Events

Adverse events (AEs) were the most frequently shared negative experience with tirzepatide. Adverse events were not probed, but were often spontaneously shared when participants discussed what they had disliked about tirzepatide or their overall trial experience. The most common AE reported was nausea (n = 43/86, 50%), followed by diarrhea (n = 16/86, 19%). A summary of AEs described during the exit interviews is shown in Fig. 2. Most participants reported that AEs resolved either by themselves, with treatment, or with decreases in the tirzepatide dose (which was permitted in the open-label phase of the study).

Comparison of Tirzepatide and Placebo Experiences

When describing their experiences during the blinded phase of the trial, participants shared further positive or negative treatment-associated changes, or acknowledged the maintenance of some of the improvements that they had initially noticed during the open-label phase. Once the interviews were completed, trial unblinding allowed the researchers to identify which interview participants had been randomized to continue tirzepatide (n = 50/86, 58%) or randomized to receive placebo (n = 36/86, 42%) during the blinded phase of SURMOUNT-4. This allowed for a post-hoc sub-group analysis of interview concepts by treatment arm. As interviews were semi-structured (lasting 90 minutes), not all open-label phase changes were revisited in the subsequent blinded phase discussion.

The top five concepts discussed by participants when speaking about their blinded phase experiences are presented in Table 3, and include counts for the concept improving (a perceived benefit), being maintained, or worsening (a negative impact). Results are separated by treatment arm with accompanying quotes. Additional blinded phase experiences are reported in Table 13 onwards of the ESM. All 50 interview participants randomized to continue tirzepatide reported one or more additional perceived benefits during the blinded phase, or a maintenance of the improvements initially experienced during the open-label phase. Eighteen participants (n = 18/50, 36%) reported experiencing one or more aspects of their daily lives worsen while continuing to receive tirzepatide.

Table 3.

Most frequently reported experiences during the blinded phase of SURMOUNT-4

| Concept | Type of experience | Quote(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived benefit (improvement) | Maintenance | Negative impact (worsening) | ||

| Appetite | ||||

|

Tirzepatide (N = 18)a |

4 | 11 | 3 | “I still didn’t have cravings, and I still, you know, didn’t feel hungry.” (S10-16-F-TZP) |

|

Placebo (N = 28) |

0 | 4 | 24 | “I noticed that, err, I was starting to desire more to eat. The things that—the sweety toothy things that I had been able to turn a blind eye to before were more appealing again. And, um, just that, that level of easy willpower was waning.” (S14-88-F-PB) |

| Positivity | ||||

|

Tirzepatide (N = 21) |

6 | 15 | 0 | “Oh, I got happier. I mean, I guess you could say that I got happier as the weight was coming off.” (S7-41-F-TZP) |

|

Placebo (N = 21) |

0 | 8 | 13 | “I didn’t gain all the weight that I lost, but I still felt very sad about it.” (S1-28-F-PB) |

| Energy level | ||||

|

Tirzepatide (N = 23) |

5 | 16 | 2 | “But I, I noticed during—while I was taking the medicine, the entire time, I had, err, lots of energy.” (S11-60-F-TZP) |

|

Placebo (N = 10) |

1 | 2 | 7 | “Then all of a sudden, your health—you’re not feeling as healthy, you’re not having the same amount of energy.” (S4-38-F-PB) |

| Confidence | ||||

|

Tirzepatide (N = 14) |

6 | 8 | 0 | “… just [experience] a continued increase in my confidence.” (S2-36-F-TZP) |

|

Placebo (N = 7) |

2 | 2 | 3 | “I think it [confidence] has dwindled through the blind treatment period, because I’ve gained weight.” (S15-86-F-PB) |

| Participation in social events | ||||

|

Tirzepatide (N = 9) |

3 | 6 | 0 | “Social life, yes, it has changed tremendously. I have been more confident with dating, actually going out, going out to eat, all of that.” (S9-34-F-TZP) |

|

Placebo (N = 12) |

2 | 7 | 3 | “I got to be a little more social, kind of, during that, err, blind label period as I was feeling better.” (S13-72-F-PB) |

aCounts indicate the number of participants who spoke about each concept during spontaneous discussion. All participants did not speak in detail about their experiences during the blinded phase of SURMOUNT-4

In contrast, nearly all participants receiving placebo (n = 33/36, 92%) reported a loss of one or more of the perceived benefits that they had noticed in the open-label phase during the blinded phase of SURMOUNT-4. Only 13 (n = 13/36, 36%) participants randomized to placebo felt that they had experienced any new perceived benefits during the blinded phase, and 23 (n = 23/36, 64%) felt that they had managed to maintain at least one improvement noticed during the open-label phase. Self-reported participation in social events was broadly equal between tirzepatide and placebo groups, where six participants randomized to tirzepatide reported that they had maintained improvements to their social life during the blinded phase, as did seven participants randomized to placebo (Table 3).

Overall Perception of Tirzepatide

Participants were asked about their overall experience receiving tirzepatide, and generally provided positive feedback about the drug.

“It was positive—I have to say, it was positive in every way. I can’t think of a, of a drawback that I would even—I would have to really think hard to come up with something that was negative about the experience, ‘cause it was just—it was great.” (S4-15-F-TZP)

“[Tirzepatide is] amazing. I mean I had some minor side effects, but they weren’t significant enough to affect how I felt.” (S4-11-F-PB)

However, one exit interview participant felt that they had experienced minimal treatment benefit from tirzepatide.

“Honestly, I didn’t find it to be super effective, for me. Um, I noticed with [past weight loss attempts], um, I had had pretty significant, um, um, weight loss, err, very early on, um, and that’s just not—I did not experience that with this, um, with this medication at all.” (S11-61-F-PB)

Participants were also asked to explain what they liked about the drug other than its effect on their weight. Most frequently, participants reported that they liked the improved appetite regulation (n = 35/86, 41%) and reduced cravings (n = 19/86, 22%) that they had experienced. Participants were also positive about the weekly dose and the low time burden required for the treatment (n = 16/86, 19%).

“I mean, the best way is it just kept me from really thinking about food and I just stopped craving sweets or carbs as much, as well. They just didn’t sound as good as they always sound when I’m not [laughs] on the drug.” (S11-70-F-PB)

“I did enjoy the fact that it was only a once a week.” (S3-24-F-TZP)

When asked if there was anything they had disliked about tirzepatide, participants most frequently mentioned their experience of AEs (n = 40/86, 47%), followed by needing to refrigerate the study medication (n = 14/86, 16%).

“At the beginning it was a little, um, difficult, because I think that my body had to adjust to the medication. Certain things, like, um, where I may experience some nausea, um, stomach cramping, um, a little diarrhea and things like that, because it was something that I wasn’t used to. Um, but overall, I, um, did very well. Um, the weight started coming off quickly.” (S3-24-F-TZP)

“I think the only thing that was, kind of, inconvenient was the fact that it needed to be kept refrigerated. Sometimes that was a bit of a struggle, um, but overall, I didn’t really have any-anything negative about it.” (S4-13-F-PB)

Willingness to Continue Tirzepatide

Of the 85 participants who were asked, the majority (n = 77/85, 91%) confirmed that they would continue taking tirzepatide in order to lose more weight or maintain their current weight, or would take it again in the future if they regained weight. This included both participants who had discontinued the study medication during the blinded phase as their appetite and cravings had returned (after unblinding, both participants were confirmed to be randomized to placebo). Fifty-eight participants who had expressed interest in taking tirzepatide again (58/77, 75%) had experienced at least one side effect.

“I definitely would love to take it in the future […] it helped me with my weight loss, it helped me with, you know, just my mobility as far as, like, moving around and doing different activities. So, it just, just makes you feel good. It made me feel good all the way around, you know, during the time I was in the trial.” (S7- 39-F-PB)

“My tummy always hurt, not as much as it did the 24-hour period when I felt gross, but it, it never felt good, and I had headaches, I told [R], my Nurse, about that, um, but that’s it. I mean, the positives definitely outweighed the, the negative … I would take it right now if I could get my hands on it.” (S10-17-F-TZP)

Two participants were unsure whether they would continue taking tirzepatide for weight loss/maintenance, either because of low efficacy or the side effects/AEs that they had experienced. Six other participants stated that they would not consider taking tirzepatide in the future because of their experience of persistent AEs (e.g., daily diarrhea; n = 2/6, 33%), the lack of information available on potential long-term impacts or risk of complications from tirzepatide (n = 2/6, 33%), concerns about needing to rely on the drug permanently to maintain weight loss (n = 1/6, 17%), or because it was not necessary for them to manage their weight (n = 1/6, 17%).

“I would have to pass on it because I felt so bad on it.” (S13-54-F-TZP)

“Probably not until there’s more, more, um, study information available. And I say that from the standpoint of are there any long-term effects on staying on tirzepatide without the—‘cause it’s my understanding tirzepatide is for diabetes, yeah. Um, is there—and I guess, not knowing if there’s long-term effects or … studies that show whether there’s any long-term effects of staying on tirzepatide long-term.” (S14-93-M-PB)

Single-Use Injection Pen Device Experience

Almost all participants (n = 84/86, 98%) reported that the single-use injection pen device for tirzepatide was easy to use. The remaining two participants (n = 2/86, 2%) expressed mixed feelings because of either having issues with the device during the trial or being nervous about self-injecting. Both participants felt that the device became easier to use with experience.

Participants particularly liked that the device was simple to use, with minimal steps to follow (n = 37/86, 43%), and that it was pre-loaded with the study medication (n = 28/86, 33%). Several participants also commented that they experienced low or no pain (n = 16/86, 19%) or that they liked the small needle size (n = 14/86, 16%).

“It would have been very difficult to not do it right. It had a locking device on it. It didn’t make any difference if it was warm or cold. You really didn’t feel it. The needle was small, it, it went in. Yeah, it was very easy to do.” (S4-12-M-TZP)

“Compared to some other injections, like I’ve said, that I know my family has to do, I like that it was already—the medication was already drawn up, you didn’t have to do any adjusting for dosages. It was just ready to go for you, that was really convenient.” (S8-31-F-TZP)

Some participants (n = 16/86, 19%) felt that aspects of the device were less favorable, including the overall size of the device (n = 8/16, 50%), having to use a needle to administer the medication (n = 5/16), and the wastefulness of the single-use packaging (n = 3/16, 19%).

“It was really long… it’s difficult to travel with, I would say, but—I mean, if it was shorter, it would be easier to carry.” (S4-18-M-TZP)

“I feel like, it’s pretty wasteful, honestly. Like, the amount of packaging that goes into each pen is—you know, there’s a lot of waste that goes into it and I know that, you know, part of the reason that I like it is because it was so easy to use, which is why it’s in a pen, but, you know, in my mind, I’m like, gosh, this is just so much junk getting thrown away every time. So, that always, kind of, stuck in my mind a bit.” (S11-61-F-PB)

Overall Trial Experience

Participants generally reported that SURMOUNT-4 had been a positive experience for them. More than half of participants reported that the site staff were a particularly positive aspect of their trial experience (n = 43/86, 50%), with site staff frequently described as “very friendly” (S1-28-F-PB). Participants also praised site staff for being able to present information about the trial “in a really easy way to understand” (S5-07-F-TZP), for being available at any time to answer questions, for providing remedies to side effects, and for generally being their “biggest cheerleaders” (S13-52-F-TZ) throughout the trial.

“It could not have been more positive, and I told—you know, my last visit, when I was in there, I told them, too, I mean to a person. And, you know, I don’t know if it—I’m sure this study was run, you know, terrifically well by [R], but, like, the clinic that I did it at was just absolutely so easy to work with and accommodating and, um, just to a, to a person that was there, they were all just fantastic.” (S4-14-F-TZP)

Participants also reported feeling rewarded by their participation, knowing that they were contributing to wider scientific knowledge (n = 14/86, 16%).

“And so, I found it to be, like, a really rewarding experience to, like, help contribute to that because I was having such great benefits and I was like, “Once this drug hits the market, like, it’s going to be able to help so many people.” (S3-64-F-PB-D)

Where time permitted, participants were also asked if they would consider participating in a future clinical trial for a drug that was relevant to them (not limited to obesity/weight management). Most confirmed that they would be willing to take part in a future trial (n = 63/67, 94%) with the remaining four participants explaining that their participation in any future trial would depend on the trial requirements or their own personal circumstances at the time.

Discussion

This cross-sectional, non-interventional, qualitative exit interview study included 86 adults who had participated in the SURMOUNT-4 clinical trial, investigating the effect of tirzepatide on weight reduction and maintenance in participants who have obesity or overweight without diabetes. During the open-label phase of SURMOUNT-4, all 86 exit interview participants experienced weight loss, alongside a variety of additional perceived benefits, and some negative impacts and/or side effects. Most commonly, participants experienced improved appetite control, increased energy levels, improved clothing fit, and increased levels of happiness. The results of this interview study reinforce the quantitative findings of the SURMOUNT-4 clinical trial, which identified significant improvements in physical functioning and mental health alongside changes in weight [15]. These exit interviews have allowed participants in SURMOUNT-4 to freely reflect on their experiences with tirzepatide and the clinical trial, and to share deeper insights not only related to their weight, physical functioning, and mental health, but also daily life, social life, physical appearance, work, and leisure time, based on what was noticeable and important to them. The eight domains reported in this interview study frequently appear in the wider literature related to the impact of obesity [27–29], and so changes across each domain are likely to be relevant and important to many individuals who are living with obesity and overweight, who may consider pharmaceutical weight management options in the future.

The results highlight that participants had generally positive experiences with tirzepatide, with one participant describing it as “by far, the best decision I ever made” (S9-09-F-TZP). Despite AEs such as nausea and diarrhea being frequently reported, many participants were willing to continue taking tirzepatide in the future, which mirrors opinions shared in a previous qualitative study conducted with patients receiving a different weight management drug [30]. In addition, the changes reported by participants in this study have a considerable overlap with factors known to be associated with weight loss maintenance, including increased physical activity, increased social connections and support, and reduced emotional distress [8, 10], suggesting that the use of pharmaceutical weight management options may help facilitate long-term weight loss maintenance.

Participant experiences reported in this study align closely with SURPASS-2/SURPASS-3 exit interview study findings [21], particularly to the types of changes experienced, the emotional impact of weight changes, and the general experience of AEs. Findings suggest that the effects of tirzepatide appear to be consistent across different populations, including those with and without type 2 diabetes. Despite not achieving the target sample size, the final sample size of 86 participants is considered a strength of this exit interview study as it is large for qualitative research, and larger than the typical sample for exit or in-trial interview research [21, 31]. Given that a large sample size was achieved, and conceptual saturation was reached within the first ten interviews conducted, the results are likely to be representative of the SURMOUNT-4 clinical trial population in the USA. Qualitative methods were also employed in line with industry guidance and recommendations [17], strengthening findings.

Overall, the participant sample was well represented by those randomized to tirzepatide (n = 50, 58%) and to placebo (n = 36, 42%), which is close to the 1:1 treatment arm split in SURMOUNT-4 [11]. The mean age, percentage of White participants, and mean BMI of the overall sample at baseline were also comparable to the SURMOUNT-4 trial population [15]. However, this study sample included a higher number of female participants (n = 71/86, 83%), in comparison to the overall SURMOUNT-4 trial (69.7% female). Male participants in SURMOUNT-4 are therefore not as well represented in this exit interview study, and while the proportion of non-White participants closely aligns with SURMOUNT-4, the lack of ethnic diversity in this study is considered a limitation. Given that the prevalence of obesity in the USA appears to be highest in Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black demographic groups [32], further research in obesity and pharmaceutical weight management should ensure that these groups are well represented. Additionally, this study was conducted in the USA only, and therefore results may not be transferable to the global SURMOUNT-4 population.

As interviews were conducted, on average, five weeks after completing SURMOUNT-4, participant responses may be impacted by recall bias. It is unknown whether participants would have shared more positive or more negative experiences if interviewed within a shorter window. Furthermore, despite concerted recruitment efforts, only two study medication discontinuers (both randomized to the placebo arm) participated in an interview, and no participants who discontinued the entire SURMOUNT-4 trial were interviewed. The sample is therefore potentially biased to those who had a positive tirzepatide experience, as they completed the trial and willingly took part in an interview. This limitation may also account for the much smaller number of negative experiences reported, relative to the amount of positive feedback shared.

Conclusions

This exit interview study provided in-depth insights into the participant experience of SURMOUNT-4. Participants were largely positive about their trial experience, and perceived tirzepatide to be effective both for weight loss and subsequent improvements in aspects of daily life such as physical functioning, emotional well-being, and social life and relationships, which are frequently negatively impacted by living with obesity or overweight. Participants also described the single-use injection pen device used in SURMOUNT-4 as easy to use and shared positive feedback about the device, supporting this as an acceptable method of delivery for tirzepatide.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. The authors thank the SURMOUNT-4 clinical trial sites who supported recruitment activities for this study, and the participants for their time and participation.

Declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Conflict of interest

Chloe Carmichael, Elizabeth Collins, Danielle Burns, and Helen Kitchen are employed by Clarivate, a company that received funding from Eli Lilly and Company for time spent conducting this research. Irina Jouravskaya, Jiat Ling Poon, Donna Mojdami, Madhumita Murphy, Nadia Ahmad, and Chisom Kanu are employed by and own stock in Eli Lilly and Company.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol and associated documents were submitted for review to the Advarra Institutional Review Board and received approval on 3 January, 2023 (ID: Pro00067958).

Consent to participate

Participants provided written informed consent before any study activities were initiated. Participants were informed that this study was being completed for research purposes. Participants were informed that the anonymized coded data and transcripts would be analyzed and shared. Participants were informed that every effort would be made to report their information in a way that protects their privacy by avoiding any mention of their name or other information that could identify them.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and/or design. Data collection and analysis were directed by EC, DB, CC, and HK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by EC, DB, and CC. All authors commented on and revised the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed 1 Aug 2024.

- 2.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body fatness and cancer: viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794–8. 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Medical Association. Report of the Council on science and public health: is obesity a disease? https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/about-ama/councils/Council%20Reports/council-on-science-public-health/a13csaph3.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2024.

- 4.Kyle TK, Dhurandhar EJ, Allison DB. Regarding obesity as a disease: evolving policies and their implications. Endocrinol Metab Clin. 2016;45(3):511–20. 10.1016/j.ecl.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mertens IL, Van Gaal LF. Overweight, obesity, and blood pressure: the effects of modest weight reduction. Obes Res. 2000;8(3):270–8. 10.1038/oby.2000.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen MD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;129(25):2985–3023. 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolotkin RL, Andersen JR. A systematic review of reviews: exploring the relationship between obesity, weight loss and health-related quality of life. Clin Obes. 2017;7(5):273–89. 10.1111/cob.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dombrowski SU, Knittle K, Avenell A, Araújo-Soares V, Sniehotta FF. Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348: g2646. 10.1136/bmj.g2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evert AB, Franz MJ. Why weight loss maintenance is difficult. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30(3):153–6. 10.2337/ds017-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elfhag K, Rössner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005;6(1):67–85. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.le Roux CW, et al. Tirzepatide for the treatment of obesity: rationale and design of the SURMOUNT clinical development program. Obesity. 2022;31(1):96–110. 10.1002/oby.23612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jastreboff AM, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garvey WT, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity in people with type 2 diabetes (SURMOUNT-2): a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10402):613–26. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01200-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wadden TA, et al. Tirzepatide after intensive lifestyle intervention in adults with overweight or obesity: the SURMOUNT-3 phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2023;29:2909–18. 10.1038/s41591-023-02597-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aronne LJ, et al. Continued treatment with tirzepatide for maintenance of weight reduction in adults with obesity: the SURMOUNT-4 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;331(1):38–48. 10.1001/jama.2023.24945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new medication for chronic weight management. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-medication-chronic-weight-management. Accessed 1 Aug 2024.

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: methods to identify what is important to patients. Guidance for Industry 2, Food and Drug Administration staff, and other stakeholders. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-methods-identify-what-important-patients. Accessed 7 July 2024.

- 18.US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: incorporating clinical outcome assessments into endpoints for regulatory decision-making. Draft guidance for Industry 4, Food and Drug Administration staff, and other stakeholders. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-incorporating-clinical-outcome-assessments-endpoints-regulatory. Accessed 1 Aug 2024.

- 19.Willgoss T, Kitchen H, Krupnick R, Burbridge C, DiBenedetti D. Innovations in in-trial interviews: novel approaches to capturing the patient experience in quality of life research. In: Presented at the ISOQOL 30th annual conference; 18–21 October, 2023; Calgary.

- 20.Staunton H, et al. An overview of using qualitative techniques to explore and define estimates of clinically important change on clinical outcome assessments. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3(1):16. 10.1186/s41687-019-0100-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matza LS, Stewart KD, Landó LF, Patel H, Boye KS. Exit interviews examining the patient experience in clinical trials of tirzepatide for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Patient. 2022;15(3):367–77. 10.1007/s40271-022-00578-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmichael C, Collins E, Marshall C, Macey J. Qualitative content analysis for concept elicitation (CACE) in clinical outcome assessment development. In: Presented at the ISPOR EU 2023; 12–15 November, 2023; Copenhagen. https://www.ispor.org/heor-resources/presentations-database/presentation/euro2023-3788/133489. Accessed 28 Jan 2025.

- 23.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick DL, et al. Content validity: establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1: eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14(8):967–77. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep. 2015;20(9):1408–16. 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2281. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1263–78. 10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Homer CV, Tod AM, Thompson AR, Allmark P, Goyder E. Expectations and patients’ experiences of obesity prior to bariatric surgery: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2): e009389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas SL, Hyde J, Karunaratne A, Herbert D, Komesaroff PA. Being ‘fat’in today’s world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in Australia. Health Expect. 2008;11(4):321–30. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rand K, et al. “It is not the diet; it is the mental part we need help with”. A multilevel analysis of psychological, emotional, and social well-being in obesity. Int J Qual Stud Health. 2017;12(1):1306421. 10.1080/17482631.2017.1306421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierret AC, Benton M, Sen Gupta P, Ismail K. A qualitative study of the mental health outcomes in people being treated for obesity and type 2 diabetes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. Acta Diabetol. 2024. 10.1007/s00592-024-02392-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galipeau N, Ollis S, McLafferty M, Love E, Litcher-Kelly L. PCR146 in-trial interview sample size: a review of the published literature. Value Health. 2023;26(6):S339. 10.1016/j.jval.2023.03.1922. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. In: Centers for disease control and prevention. NCHS Data Brief. 2017. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/49223. Accessed 17 Dec 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.