Abstract

Background:

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic significantly impacted global health, with India experiencing one of the highest case and death tolls. However, data specific to India’s sociodemographic and clinical factors influencing COVID-19 mortality remains limited.

Objective:

This study aimed to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 mortality in India.

Methods:

This retrospective, cross-sectional study analyzed medical records of 4961 adult COVID-19 patients admitted to a tertiary care center in North India, from April 2020 to December 2021. Sociodemographic and clinical data were captured using a structured proforma. Univariate analysis (chi-square test) and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis were performed to identify factors associated with mortality.

Results:

Of the 4961 patients, 557 (11.2%) died, and 4404 (88.8%) survived. Increased age, rural residency, professional occupation, and comorbidities (diabetes and hypertension), multimorbidity, increased disease severity, cold and flu symptoms, breathlessness, and the need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission and ventilator support were significantly (P <0.05) associated with higher COVID-19 mortality. While some associations were observed with sociodemographic factors like religion, education level, and monthly family income in univariate analysis, these were not significant in survival analysis.

Conclusion:

In this cohort of COVID-19 patients in India, advanced age, rural residency, professional occupation, comorbidities, multimorbidity, severe symptoms, and the need for ICU admission and ventilator support were identified as significant risk factors for mortality. Early identification and intervention for these high-risk groups may improve survival rates.

Keywords: COVID-19, India, mortality, risk factors, comorbidity

1. BACKGROUND

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), had a devastating global impact (1). By November 6, 2024, COVID-19 had infected more than 700 million individuals and caused over 7 million deaths worldwide. India bore a significant burden, with a COVID-19 prevalence exceeding 45 million cases and over half a million deaths, ranking second globally (2).

Studies, primarily conducted in Western and Chinese populations, have identified several risk factors associated with fatal outcomes in COVID-19 patients, including older age, male gender, current smokers, pre-existing comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic pulmonary disease, cancer, and the development of complications (3-5).

The COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges to healthcare systems worldwide. Understanding the factors associated with mortality is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies and preparing for future pandemics. While the pandemic’s impact was widespread, data specific to the Indian context, with its unique demographics and healthcare infrastructure, remains limited (6, 7). This study, conducted at a tertiary healthcare centre in Faridabad, North India, aims to identify sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with mortality among COVID-19 patients admitted during the peak pandemic months (April 2020 to December 2021). These findings will contribute to the development of tailored guidelines for COVID-19 management across different healthcare systems and inform preparedness strategies for future infectious disease outbreaks worldwide.

2. OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 mortality in India.

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

This retrospective, cross-sectional, observational study was conducted at a tertiary care centre located in North India.

Ethical considerations

The study was performed in lines with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Employee’s State Insurance Corporation Medical College and Hospital (Date: 9-4-2021/F.No.134/A/11/16/Academic/MC/2016/196).

Study participants

This study retrospectively analysed the medical records of adult patients (aged 18 years and older) admitted to our hospital between April 1, 2020, and December 31, 2021, who met the World Health Organization (WHO) interim guidance criteria for COVID-19 diagnosis. Diagnosis was confirmed via real-time polymerase chain reaction (RTPCR) testing of nasopharyngeal swabs. All hospitalized patients received therapy in accordance with state and national guidelines [8]. Patients were eligible for discharge upon clinical improvement and a negative RTPCR test for SARS-CoV-2.

Data collection

Data was collected at the Medical Records Department of our institute from the medical records of the included patients using a validated, and structured proforma. Patients with incomplete data were excluded from the study. The sociodemographic data captured included age, sex, religion, area of residence, education, occupation, and total family income. The clinical data extracted included signs and symptoms as reported by the patients, presence of comorbidities, severity of the symptoms as classified by the treating clinician, requirement for intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and requirement of ventilatory support.

Working definitions

For this study, we classified patients as rural or urban based on their residence at the time of admission, using the definitions provided by the Census of India 2011 (9). Education levels were classified as illiterate (cannot read or write), elementary school (up to grade 5), secondary school (up to grade 10), high school (up to grade 12), and university (undergraduate or postgraduate). Occupations were classified as unemployed (actively seeking but not employed), unskilled worker (performing manual labour), semi-skilled (doing technical work but without formal training), farmer/shop owner (involved in agriculture or small business ownership), skilled worker (possessing specialized technical expertise), and professional (holding advanced qualifications such as law, medicine, etc).

Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg. Diabetes was defined as HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL. Cold and flu was defined as non-specific upper respiratory tract symptoms such as cough, running nose, congestion, with or without fever. Patients were defined as having mild, moderate or severe COVID-19 infection, according to the guidelines laid down by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India [8].

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage (%). Univariate analysis of categorical variables was done using the chi-square test to identify potential factors associated with mortality. Variables found to be significantly associated with mortality (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were then further analysed using the Kaplan-Meier survival curves to assess their impact on time to event (mortality). The Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to compare survival curves between groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Data analysis was done using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23) for Windows, with initial data entry into Microsoft Excel.

4. RESULTS

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 4961 COVID-19 cases were admitted to our hospital between April 2020 to December 2021. Of these 557 (11.2%) patients died, and 4404 (88.8%) survived. Their sociodemographic parameters are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of our cohort was 51.27 ± 14.41 years. Majority of the included patients were males (65.5%). The largest age group was 41-50 years (25.8%) followed by 51-60 years (25.5%). Most patients identified as Hindu (54.9%). The majority resided in urban areas (75.4%). A substantial portion of the patients were university educated (53%), and the most common occupation category was unskilled worker (23%). The most frequently reported total family monthly income fell within the <20000 INR range (46.7%). Over 70% had comorbidities, including diabetes (42.7%) and hypertension (43.1%) [Table 1]. The majority of the patients experienced cold and flu-like symptoms (88.4%), sore throat (70.3%), breathlessness (60.9%), and pain in abdomen (53%). Over half required ICU admission (52.5%) and a quarter needed ventilator support (25.4%) [Table 1].

Table 1. Association of sociodemographic and clinical variables of COVID-19 patients with mortality. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; INR, Indian National Rupees; ICU, intensive care unit; * statistically significant (P value <0.05).

| Variable | Survived (n = 4404) |

Dead (n = 557) |

Total (n = 4961) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) Male Female |

2886 (88.9) 1518 (88.6) |

362 (11.1) 195 (11.4) |

3248 (100) 1713 (100) |

0.801 |

| Age categories, years (%) < 20 21-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 61-70 71-80 > 80 |

57 (93.4) 281 (93.0) 725 (90.6) 1134 (88.5) 1133 (89.5) 691 (88.4) 295 (88.6) 88 (65.2) |

4 (6.6) 21 (7.0) 75 (9.4) 148 (11.5) 133 (10.5) 91 (11.6) 38 (11.4) 47 (34.8) |

61 (100) 302 (100) 800 (100) 1282 (100) 1266 (100) 782 (100) 333 (100) 135 (100) |

0.001* |

| Religion (%) Hinduism Islam Christianity Others |

2440 (89.6) 846 (87.9) 472 (89.7) 646 (86.1) |

282 (10.4) 117 (12.1) 54 (10.3) 104 (13.9) |

2722 (100) 963 (100) 526 (100) 750 (100) |

0.035* |

| Area (%) Rural Urban |

1042 (85.3) 3362 (89.9) |

179 (14.7) 378 10.1) |

1221 (100) 3740 (100) |

0.001* |

| Education (%) Illiterate Elementary school Secondary school High school University |

325 (92.1) 500 (90.9) 585 (89.7) 680 (87.3) 2301 (87.9) |

28 (7.9) 50 (9.1) 67 (10.3) 95 (12.2) 317 (12.1) |

353 (100) 550 (100) 652 (100) 779 (100) 2627 (100) |

0.049* |

| Occupation (%) Unemployed Unskilled worker Semi-skilled worker Farmer/shop owner Skilled worker Professional |

574 (87.1) 1028 (90.1) 716 (90.5) 790 (88.8) 706 (89.1) 590 (85.8) |

85 (12.9) 113 (9.9) 75 (9.5) 100 (11.2) 86 (10.9) 98 (14.2) |

659 (100) 1141 (100) 791 (100) 890 (100) 792 (100) 688 (100) |

0.027* |

| Total family monthly income (INR) (%) <20000 20001-30000 30001-40000 40001-50000 >50000 |

2046 (88.4) 1016 (90.2) 429 (86.1) 423 (92.0) 490 (87.3) |

269 (11.6) 111 (9.8) 69 (13.9) 37 (8.0) 71 (12.7) |

2315 (100) 1127 (100) 498 (100) 460 (100) 561 (100) |

0.019* |

| Comorbidities (%) Yes No |

3028 (85.4) 1376 (97.3) |

519 (14.6) 38 (2.7) |

3547 (100) 1414 (100) |

0.001* |

| Number of comorbidities (%) No comorbidity 1 comorbidity 2 comorbidities 3 comorbidities ≥ 4 comorbidities |

1378 (97.5) 1328(95.7) 996 (92.1) 447 (78.0) 255 (50.7) |

38 (2.5) 59 (4.3) 86 (7.9) 126 (22.6) 248 (49.3) |

1416 (100) 1387 (100) 1082 (100) 573 (100) 503 (100) |

0.001* |

| Diabetes (%) Yes No |

1719 (81.2) 2685 (94.4) |

397 (18.8) 160 (5.6) |

2116 (100) 2845 (100) |

0.001* |

| Hypertension (%) Yes No |

1739 (81.4) 2665 (94.4) |

398 (18.6) 159 (5.6) |

2137 (100) 2824(100) |

0.001* |

| Cold and flu (%) Yes No |

3875 (88.4) 529 (91.8) |

510 (11.3) 47 (8.2) |

4385 (100) 576 (100) |

0.013* |

| Sore throat (%) Yes No |

3098 (88.9) 1306 (88.5) |

388 (11.6) 169 (11.5) |

3486 (100) 1475 (100) |

0.467 |

| Diarrhea (%) Yes No |

1308 (88.4) 3096 (88.9) |

171 (11.6) 386 (11.1) |

1479 (100) 3482 (100) |

0.627 |

| Pain in abdomen (%) Yes No |

2310 (87.9) 2094 (89.8) |

318 (12.1) 239 (10.2) |

2628 (100) 2333 (100) |

0.039* |

| Loss of smell (%) Yes No |

2570 (88.7) 1834 (88.9) |

327 (11.3) 230 (11.1) |

2897 (100) 2064 (100) |

0.908 |

| Loss of taste (%) Yes No |

1561 (89.2) 2843 (88.5) |

189 (10.8) 368 (11.5) |

1750 (100) 3211 (100) |

0.481 |

| Breathlessness (%) Yes No |

2654 (87.9) 1750 (90.2) |

366 (12.1) 191 (9.8) |

3020 (100) 1941 (100) |

0.013* |

| Disease severity (%) Mild Moderate Severe |

1832 (91.6) 1724 (88.9) 848 (83.0) |

168 (8.4) 215 (11.1) 174 (17.0) |

2000 (100) 1939 (100) 1022 (100) |

0.001* |

| ICU admission (%) Yes No |

2122 (81.1) 2282 (97.4) |

496 (18.9) 61 (2.6) |

2618 (100) 2343 (100) |

0.001* |

| Ventilator support (%) Yes No |

791 (62.7) 3613 (97.6) |

470 (37.3) 87 (2.4) |

1261 (100) 3700 (100) |

0.001* |

Univariate analysis

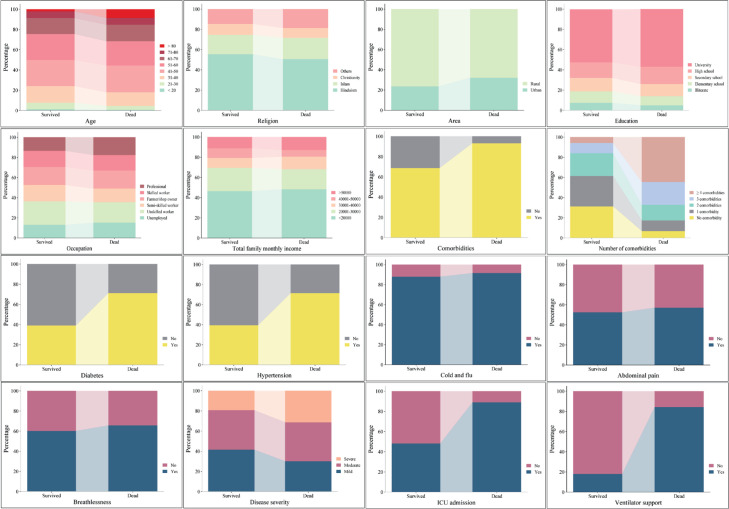

Univariate analysis of the sociodemographic parameters indicated that increasing age was significantly associated with higher mortality (P = 0.001), with the >80 age group experiencing the lowest survival rate (65.2%). Area of residence and religion were also significantly (P = 0.001) associated with mortality. While statistically significant, weaker associations were observed for education level (P = 0.049), occupation (P = 0.027), and total family monthly income (P = 0.019). No significant association was observed between mortality and sex (P = 0.801) [Table 1, Figure 1]. Presence of comorbidities revealed a strong association with mortality (P = 0.001). Patients with any comorbidities had a significantly higher risk of death (14.6%) compared to those without (2.7%). The risk of mortality increased with the number of comorbidities (P = 0.001), with patients having ≥ 4 comorbidities experiencing the highest mortality rate (49.3%). Both diabetes and hypertension were significantly (P = 0.001) associated with increased mortality [Table 1, Figure 1]. Patients experiencing cold and flu symptoms, abdominal pain, and breathlessness (all P < 0.005) were associated with increased mortality. Disease severity was also strongly associated with mortality (P = 0.001), with severe cases having a higher death rate. Similarly, ICU admission(P = 0.001) and need for ventilator support (P = 0.001) were strongly associated with increased mortality. No significant associations were found between mortality and sore throat, diarrhoea, loss of smell, or loss of taste (Table 1, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Univariate analysis of sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients. Factors showing statistical significance are depicted.

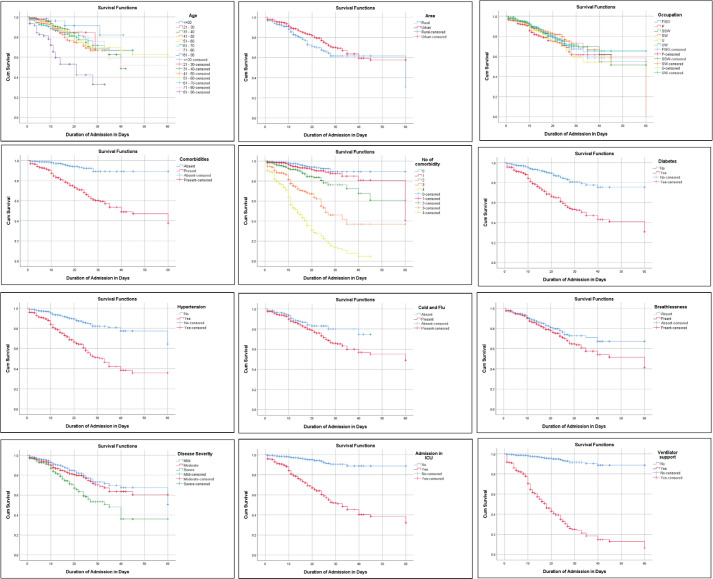

Survival analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank testing, performed on variables found to be associated with mortality by the chi-squared test, confirmed that increased age, rural residence, professional occupation, presence of comorbidities (including diabetes and hypertension), multimorbidity, cold and flu symptoms, breathlessness, disease severity, ICU admission, and the need for ventilator support were significantly associated with mortality (P < 0.005). No statistically significant association with survival was found for religion, education level, total monthly family income, and abdominal pain (P = 0.088, 0.053, 0.132, and 0.052, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients. Factors showing statistical significance are depicted.

5. DISCUSSION

This study of COVID-19 patients in India found that that increasing age, rural residency, professional occupation, the presence of comorbidities (particularly diabetes and hypertension), multimorbidity, and increased disease severity were significantly associated with higher mortality, often requiring ICU admission, and ventilator support.

Our cohort had a survival rate of 88.8% and mortality rate of 11.2%, which are consistent with mortality rates reported in other studies with similar settings [10]. Consistent with a large meta-analysis (11), our study found a significant association between increasing age and higher COVID-19 mortality, with the lowest survival in patients over 80. The meta-analysis similarly reported increased risk over age 50, especially over 60, and a six-fold increase for those 80 and above (11). Consistent with a previous study conducted in the US, we found that patients from rural areas had higher mortality rates. This rural-urban disparity could have resulted from a combination of factors, including limited healthcare access, lower health literacy, and delays in seeking treatment among the rural population [12]. Our findings of lower survival rates among professionals is consistent with previous research indicating elevated COVID-19 risk for healthcare workers and educators (13).

Our study confirms the significant impact of comorbidities on COVID-19 mortality. Consistent with previous reports (14, 15), the presence of any comorbidity, particularly hypertension and diabetes, was associated with increased mortality. Moreover, multimorbidity was associated with dramatically increased mortality, with patients having ≥4 comorbidities experiencing an approximately 18-fold higher risk of death compared to those without comorbidities. Diabetes is thought to increase COVID-19 mortality by impairing immunity, promoting inflammation, and increasing complications like lung injury and insulin resistance. Similarly, hypertension increases COVID-19 mortality due to vascular damage, inflammation, and immune dysregulation leading to heart failure and thromboembolic events (16).

Consistent with global reports, our study found a strong association between disease severity and COVID-19 mortality (5). Cold and flu symptoms, while indicative of mild illness, could progress to severe illness. Breathlessness, a key symptom of respiratory distress, was significantly associated with mortality (17). ICU admission and ventilator support, while lifesaving, also signalled critically impaired respiratory function and were strongly associated with mortality, as observed in previous studies (5, 6). These findings underscore the importance of early recognition, and management of these symptoms could be vital for improving survival rates.

While univariate analysis suggested potential associations between several sociodemographic and clinical factors, including religion, education level, total family monthly income, and abdominal pain, these relationships did not remain statistically significant in the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. However, religion, education level, and abdominal pain trended towards significance. This discrepancy between the univariate and survival analyses may be due to several factors, including the influence of confounding variables or the reduced power of the survival analyses. A previous study had reported that confounding sociodemographic factors might mediate the relationship between religion and COVID-19 mortality [18]. In contrast to previous studies, our findings indicated that higher education is associated with higher COVID-19 mortality (19). This discrepancy may be attributable to confounding factors, such as occupation-related risks leading to increased COVID-19 exposure. Furthermore, consistent with previous reports, our cohort demonstrated the highest hospitalization rate among the lowest income group (<20000 INR) (20). However, the mortality rate was highest in the 30001-40000 INR income group.

Limitation of the study

The study has several limitations. Sample size calculation was not performed and data were collected from a single tertiary care centre, limiting the generalizability of the findings. The study’s cross-sectional nature precludes the establishment of causal relationships between identified factors and COVID-19 mortality. While our study included several sociodemographic and clinical variables, the potential influence of unmeasured confounders cannot be ruled out. This study only considered the two most common comorbidities in India, diabetes and hypertension, and other comorbidities, while also relevant, were not assessed for associations. We did not include multivariate analysis in our study.

Despite the limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 mortality within the Indian context, where limited data is available.

Larger, multi-centre prospective studies incorporating multivariate analysis are crucial for establishing causal relationships of risk factors and COVID-19 mortality. Expanding data collection to include a broader range of sociodemographic and clinical variables would further enhance understanding of the various factors influencing COVID-19 mortality.

6. CONCLUSION

Our study identifies several key factors associated with increased COVID-19 mortality in the Indian context, including older age, rural residency, professional occupation, comorbidities (diabetes and hypertension), multimorbidity, and indicators of severe disease such as breathlessness, ICU admission and ventilator support. These findings underscore the critical need for targeted healthcare strategies to manage high-risk populations and improve survival rates.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Asim Das, Dean of ESIC-MCH, Faridabad, during the COVID-19 waves, for his support and guidance in facilitating this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement:

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of E Hospital.

Declaration of patient consent:

Written informed consent was waived because of the secondary use of medical data.

Authors’ contributions:

Prasad J and Vig SL contributed to the concept and design of the study and supervised the project. Parashar L (PhD Research Scholar), Shekhar H, and Arya H were responsible for collection of the data and doing the statistical analysis. Meshram GG drafted the manuscript and prepared the graphs and tables. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest:

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Financial support and sponsorship:

All authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leong DP, Loeb M, Mony PK, Rangarajan S, Mushtaha M, Miller MS, et al. Risk factors for recognized and unrecognized SARS-CoV-2 infection: a seroepidemiologic analysis of the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Microbiol Spectr. 2024 Feb;12:2, e0149223. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01492-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization: COVID-19 Epidemiological update - 6 November 2024. Available at URL: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update-edition-173. (Accessed: 15.3.2025). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dessie ZG, Zewotir T1. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Aug;21(1):855. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartantri Y, Debora J, Widyatmoko L, Giwangkancana G, Suryadinata H, Susandi E, et al. Clinical and treatment factors associated with the mortality of COVID-19 patients admitted to a referral hospital in Indonesia. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2023 Apr;11:100167. doi: 10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arunan B, Kumar SS, Ranjan P, Baitha U, Gupta G, Kumar A, et al. Risk Factors of Severity and Mortality Among COVID-19 Patients: A Prospective Observational Study From a Tertiary Care Center. Cureus. 2022 Aug;14(8):e27814. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rathod D, Kargirwar K, Patel M, Kumar V, Shalia K, Singhal P. Risk Factors associated with COVID-19 Patients in India: A Single Center Retrospective Cohort Study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2023 Jun;71(6):11–12. doi: 10.5005/japi-11001-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health Family Welfare - Government of India. Revised Guidelines on Clinical Management of COVID-19. 2020 Available at URL: https://covid19dashboard.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/RevisedNationalClinicalManagementGuidelineforCOVID1931032020.pdf. (Accessed: 15.3.2025) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office of Registrar General Census Commissioner India. CensusInfo. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2011 Available at URL: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/HLO/HH14.html. (Accessed: 15.3.2025) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonanad C, García-Blas S, Tarazona-Santabalbina F, Sanchis J, Bertomeu-González V, Fácila L, et al. The effect of age on mortality in patients with COVID-19: A meta-analysis with 611,583 Subjects. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020 Jul;21(7):915–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnan A, Kumar R, Amarchand R, Mohan A, Kant R, Agarwal A, et al. Predictors of Mortality among Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 during the First Wave in India: A Multisite Case-Control Study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023 Mar;108(4):727–733. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.22-0705.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousufuddin M, Mahmood M, Barkoudah E, Badr F, Khandelwal K, Manyara W, et al. Rural-urban Differences in Long-term Mortality and Readmission Following COVID-19 Hospitalization, 2020 to 2023. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024 Apr;11(5):ofae197. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofae197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henneberger PK, Cox-Ganser JM. Occupation and COVID-19: Lessons From the Pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024 Aug;12(8):1997–2007.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2024.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge E, Li Y, Wu S, Candido E, Wei X. Association of pre-existing comorbidities with mortality and disease severity among 167,500 individuals with COVID-19 in Canada: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2021 Oct;16(10):e0258154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell CD, Lone NI, Baillie JK. Comorbidities, multimorbidity and COVID-19. Nat Med. 2023 Feb;29(2):334–343. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bigdelou B, Sepand MR, Najafikhoshnoo S, Negrete JAT, Sharaf M, Ho JQ, et al. COVID-19 and Preexisting Comorbidities: Risks, Synergies, and Clinical Outcomes. Front Immunol. 2022 May;13:890517. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.890517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hentsch L, Cocetta S, Allali G, Santana I, Eason R, Adam E, et al. Breathlessness and COVID-19: A Call for Research. Respiration. 2021;100(10):1016–1026. doi: 10.1159/000517400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaughan CH, Ayoubkhani D, Nafilyan V, Goldblatt P, White C, Tingay K, et al. Religious affiliation and COVID-19-related mortality: a retrospective cohort study of prelockdown and postlockdown risks in England and Wales. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021 Jan doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215694. jech-2020-215694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhuo J, Harrigan N. Low education predicts large increase in COVID-19 mortality: the role of collective culture and individual literacy. Public Health. 2023 Aug;221:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2023.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maher A, Dehnavi H, Salehian E, Omidi M, Hannani K. Relationship Between Income Level and Hospitalization Rate in COVID-19 Cases; an Example of Social Factors Affecting Health. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2022 Apr;10(1):e23. doi: 10.22037/aaem.v10i1.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]