Abstract

The unambiguous identification of Acinetobacter strains, particularly those belonging to the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex, is often hindered by their close geno- and phenotypic relationships. In this study, monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against the O antigens of the lipopolysaccharides from strains belonging to the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex were generated after the immunization of mice with heat-killed bacteria and shown by enzyme immunoassays and Western blotting to be specific for their homologous antigens. Since the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex comprises the most clinically relevant species, the MAbs were subsequently tested in dot and Western blots with proteinase K-treated lysates from a large collection of Acinetobacter isolates (n = 631) to determine whether the antibodies could be used for the reliable identification of strains from this complex. Reactivity was observed with 273 of the 504 isolates (54%) from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex which were included in this study. Isolates which reacted positively did so with only one antibody; no reactivity was observed with isolates not belonging to the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex (n = 127). To identify additional putative O serotypes, isolates from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex which showed no MAb reactivity were subjected to a method that enables the detection of lipid A moieties in lipopolysaccharides with a specific MAb on Western blots following acidic treatment of the membrane. By this method, additional serotypes were indeed identified, thus indicating which strains to select for future immunizations. This study contributes to the completion of a serotype-based identification scheme for Acinetobacter species, in particular, those which are presently of the most clinical importance.

Acinetobacter spp. have gained increased recognition in recent years as pathogens which have the potential to cause severe nosocomial infections in critically ill patients (1, 33). However, the quick and reliable identification of Acinetobacter strains has been hampered for a number of years due to the close pheno- and genotypic relatedness of some species within the genus, particularly those of clinical relevance (1, 8). Based on DNA homology studies, 23 DNA groups (genomic species) are currently delineated, nine of which have received formal species names (3, 4, 12, 20, 32). Strains from genomic species 2 (Acinetobacter baumannii), 3, and 13 sensu Tjernberg and Ursing (13TU) (32) are frequently isolated from clinical specimens and are often associated with nosocomial outbreaks (1, 33); they belong, together with genomic species 1 (Acinetobacter calcoaceticus), to the so-called A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex (11, 13). A. calcoaceticus strains are seldom isolated from patients or associated with infections (1). Other Acinetobacter strains are also isolated infrequently from patients, although both Acinetobacter junii and Acinetobacter johnsonii have been reported to be involved in cases of septicemia (2, 29). Due to the increased importance of Acinetobacter in the clinical environment and the lack of a reliable phenotypic method for the unambiguous identification of all members of the genus to the species level, we have focused on the development of an O-serotype-based identification scheme for Acinetobacter. Ongoing studies (22-27) have been centered mainly on the generation of O-antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against strains belonging to the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex, but to date, these antibodies have been tested only on small numbers of clinical isolates within a limited geographical range.

Here, we report on the serological characterization of five MAbs which were generated against the O antigens of the lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) from strains belonging to species within the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex. These antibodies were tested together with three previously described O-antigen-specific MAbs (24, 25) on a large collection of strains which had been isolated from various clinical and environmental sources in different countries worldwide. The aim of the present study was to determine the extent to which the current panel of O-antigen-specific MAbs can be used for the identification of strains from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex, the results of which will also be useful for the generation of future MAbs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

A total of 504 Acinetobacter isolates belonging to the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex were investigated in the present study (Table 1). Additional Acinetobacter strains (n = 127) belonging to genomic species outside the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex were also examined (Table 2). Most strains had been characterized previously to the species level by DNA-DNA hybridization and/or by other methods such as amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis, ribotyping, and biotyping (4–7, 9, 12, 13, 16, 19, 30, 32, 34) and were obtained from various culture collections worldwide. The strains were originally isolated from different clinical and environmental specimens, e.g., blood, cerebrospinal fluid, sputum, urine, and soil. They were preserved in nutrient broth supplemented with 20% (vol/vol) glycerol at −80°C.

TABLE 1.

Reactivities of O-antigen-specific MAbs with LPSs of proteinase K-treated whole-cell lysates from Acinetobacter isolates investigated in this study and banding patterns obtained following immunostaining with MAb A6a

| Genomic species | No. of isolates tested | No. of isolates reactive with the following MAb generated against the indicated speciesb:

|

No. of patterns obtained after acid hydrolysis | No. of isolates which did not react with any of the O-antigen-specific MAbs or with MAb A6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S51-3 | S53-1 | S48-3-13 | S48-3-17 | S53-13 | S53-32 | S48-26 | S48-13 | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 13TU | ||||

| 1 | 11 | 3 (27) | 2 (18) | — | — | — | 1 (9) | — | — | 2 | 2 (18) |

| 2 | 330 | 19c (6) | — | 92 (28) | 52 (16) | 13 (4) | 39 (12) | — | — | 13 | 55 (17) |

| 3 | 105 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 12 (11) | — | 12 | 20 (19) |

| 13TU | 58 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 33c (57) | 1 | 3 (5) |

Values in parentheses are percentages of isolates. Acid-treated membrane-bound LPSs of proteinase K-digested bacterial lysates from Acinetobacter isolates which did not react with any of the O-antigen-specific MAbs used in this study were treated with MAb A6 (18).

Dashes indicate no reactivity.

For some isolates, we obtained a banding pattern different from the banding pattern obtained with the homologous strain (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Non-A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex strains investigated in this study

Bacterial LPS, whole-cell lysates, and proteinase K digestion.

LPS was extracted by the phenol-water method (36) from the Acinetobacter strains against which MAbs were prepared (see below) and lyophilized. Preparation of whole-cell lysates and proteinase K digestion were performed as reported elsewhere (22).

MAbs.

The generation of MAbs was performed by immunizing BALB/c mice with heat-killed (100°C, 1 h) bacteria.Acinetobacter strains 7 (A. calcoaceticus) and 44 (genomic species 3), against which rabbit antisera had been produced in a previous study (22), were selected as immunogens.Acinetobacter strains ATCC 23055 (A. calcoaceticus) and ATCC 15308 (A. baumannii), purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.), as well as Acinetobacter strain NCTC 10303 (A. baumannii), purchased from the National Collection of Type Cultures (Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom), were used as additional immunogens. These strains were selected additionally because they belong to the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex, thus making them interesting immunogens for this study, and are often used as reference strains for their respective species (1, 33). All MAbs were generated according to an immunization protocol described previously (24, 25) except that booster injections with the additionally selected immunogens were administered intravenously (via the tail vein). Only those animals whose serum exhibited the strongest reactivity with the respective immunogen in a dot blot assay were given a booster injection. Two days after the last injection, these mice were exsanguinated and their spleens were removed. Spleen cells were recovered from each separate animal and subsequently fused with mouse myeloma cells (X63Ag8) at a ratio of 1:1 using polyethylene glycol 1500 (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) according to standard protocols. Screening of hybridomas, cloning by limiting dilution, isotyping, and purification of selected MAbs by protein G affinity chromatography were performed as described previously (24, 25). Antibody purity was ascertained by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (KMF Laborchemie Handels GmbH, St. Augustin, Germany). The generation of MAbs S48-3-13, S48-3-17, and S48-13 has been reported previously (24, 25). All antibodies were stored at −20°C until further use.

Serological methods.

Enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), dot blotting, and Western blotting were performed as described previously (22, 35) with purified LPS or proteinase K-treated bacterial lysates as antigens. Hydrolysis of membrane-bound LPS in 1% acetic acid and the detection of its lipid A moieties with MAb A6 (18) were carried out as described elsewhere (21).

RESULTS

Immunization of mice and preparation of MAbs.

All BALB/c mice were immunized successfully. However, only those animals whose sera exhibited the strongest reactivity with the homologous antigen by dot blotting were given booster injections, and their spleen cells were subsequently used for the generation of hybridoma cells. Hybridomas (one per antigen) which exhibited the highest EIA titers (expressed as the reciprocal value of the highest dilution of cell culture supernatant which yielded an optical density at 405 nm [OD405] of >0.2) were selected for further studies. They were cloned by limiting dilution (three times), isotyped, and purified by affinity chromatography on protein G. Purity was ascertained by Coomassie staining of SDS-PAGE gels (data not shown). MAb S51-3, against A. calcoaceticus strain 7, was of the immunoglobulin G1 isotype. MAbs S48-26, S53-1, S53-13, and S53-32, against Acinetobacter genomic species 3 strain 44, A. calcoaceticus strain ATCC 23055, A. baumannii strain ATCC 15308, and A. baumannii strain NCTC 10303, respectively, were of the immunoglobulin G3 isotype. The MAbs used in this study are listed in Table 1. The results described below were obtained with affinity-purified MAbs.

Specificities of MAbs in EIAs.

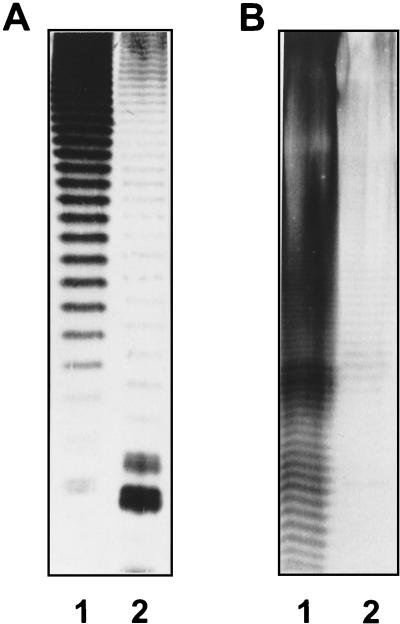

All MAbs were highly specific for their homologous antigens, as determined by their reactivities in EIAs with purified LPS (5 μg/ml; 50 μl/well) as a solid-phase antigen. Antibody concentrations which yielded an OD405 of>0.2 were between 0.5 ng/ml (MAb S51-3) and 630 ng/ml (MAb S53-13) with the homologous LPS (data not shown). None of the MAbs reacted with any of the heterologous LPS preparations; no OD405 of >0.2 was observed at antibody concentrations of up to 5 μg/ml for MAbs S48-26, S51-3, S53-1, and S53-32 or up to 50 μg/ml for MAb S53-13. Checkerboard titrations showed that all antibodies bound to the homologous LPS over a wide range of antigen concentrations (0.01 to 10μg/ml) (data not shown). The characterizations of MAbs S48-3-13, S48-3-17, and S48-13 have been reported previously (12, 13). The specificities of all antibodies were verified by Western blotting using a 10% separating gel (Fig. 1). A banding pattern characteristic of that of an O-polysaccharide chain was observed for all isolates when these were immunostained with the homologous antibody; none of the patterns were identical. No heterologous O-antigen reactivity was observed, and no reactivity with the core-lipid A moiety was observed when LPSs were separated on a 15% gel (data not shown), thus indicating that the generated MAbs are specific for their homologous antigens.

FIG. 1.

Reactivities of LPSs (25 μg each) from Acinetobacter strains used for immunization (see Materials and Methods) after SDS-PAGE on a 10% resolving gel and immunostaining with homologous MAb in a Western blot. Lane 1, A. baumannii strain 24; lane 2; A. baumannii strain 34; lane 3,Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU strain 108; lane 4,Acinetobacter genomic species 3 strain 44; lane 5, A. calcoaceticus strain 7; lane 6, A. calcoaceticus strain ATCC 23055; lane 7, A. baumannii strain ATCC 15308; lane 8,A. baumannii strain NCTC 10303.

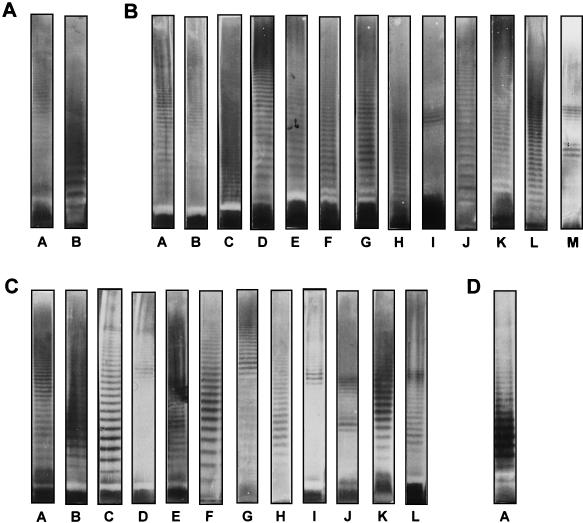

The antibodies were subsequently tested in dot blots with proteinase K-treated bacterial lysates from all Acinetobacter isolates included in this study. Reactivity was observed with 273 of the 504 isolates from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex used in this study (Table 1). None of the MAbs reacted with any of the isolates from species outside of the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex (Table 2), and none of the isolates from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex reacted with more than one antibody. Interestingly, MAbs S51-3 and S53-32 also reacted with isolates not belonging to the same genomic species as that of the strain which was used for immunization (i.e., A. calcoaceticus and A. baumannii with MAbs S51-3 and S53-32, respectively). The reactivities observed in dot blots could be confirmed by performing Western blot analysis. Although in most cases the obtained ladder patterns were indistinguishable from the pattern obtained with the respective homologous LPS (data not shown), a different banding pattern was observed for a number of isolates when they were immunostained with MAb S48-13 or MAb S51-3 (Fig. 2). Comparison of the core-lipid A moieties of these isolates with that of the homologous strain in silver-stained SDS-15% polyacrylamide gels showed no difference in migration distance (data not shown), thus suggesting that the O antigens of these isolates are antigenically related but structurally distinct.

FIG. 2.

Representative Western blots indicating differences in banding patterns observed between certain Acinetobacter isolates stained with MAb S48-13 (A) or S51-3 (B). Lanes 1, homologous strain; lanes 2, heterologous strain.

Determination of O serotypes by acid hydrolysis.

To identify additional putative O serotypes among those isolates from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex which had not reacted with any of the MAbs, a method was used to visualize any LPS via its lipid A moiety with a specific antibody (MAb A6) on Western blots following acidic treatment of the membrane-bound antigen. Twenty-eight O banding patterns were obtained (Table 1; Fig. 3): 2 were obtained for A. calcoaceticus, 13 were obtained for A. baumannii, 12 were obtained for Acinetobacter genomic species 3, and 1 was obtained for Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU. For some strains, no banding pattern was observed. The obtained patterns were different from the patterns that were observed for isolates from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex which had reacted with the O-antigen-specific MAbs and thus may indeed represent additional O serotypes within the respective Acinetobacter species. However, some of the patterns obtained after acid hydrolysis and immunostaining with MAb A6 were observed to be highly similar (Fig. 3). Patterns D and M, which were observed in some A. baumannii isolates, were found to be indistinguishable from patterns B and J, respectively, which were observed in some Acinetobacter genomic species 3 isolates.A. baumannii pattern E was found to be similar to pattern A, which was obtained with Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU isolates, and A. baumannii pattern A was indistinguishable from A. calcoaceticus pattern A.

FIG. 3.

Representative O banding patterns observed for the species indicated below following acid hydrolysis of membrane-bound LPS after SDS-PAGE (10% resolving gel) of proteinase K-digested bacterial lysates and transfer onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. (A) A. calcoaceticus; (B) A. baumannii; (C) Acinetobacter genomic species 3; (D) Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU.

DISCUSSION

The potential of members of the genus Acinetobacter to cause infection has been known for decades (14, 15, 17). However, only after the improvement of species classification within the genus as a result of DNA-DNA hybridization studies (3, 4, 20, 32) was it possible to gain insight into the ecology and the clinical significance of individual Acinetobacter species. The increased recognition of members of the genus Acinetobacter as nosocomial pathogens (1, 33) has prompted numerous research groups to search for practical methods for the identification of Acinetobacter species which can be used reliably in clinical microbiology laboratories (4, 13). Due to the successful use of LPSs as taxonomic markers for a variety of gram-negative bacteria, we are currently investigating the possibility of an identification method for Acinetobacter strains, based on the O antigens of their LPSs. In the present study, a panel of five O-antigen-specific MAbs was generated against the LPSs of strains from species belonging to the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex and, together with three previously described MAbs, tested on a large collection of Acinetobacter strains isolated from various clinical and environmental sources in different geographical areas to determine the extent to which strains from the currently clinically important genomic species can be identified by these antibodies.

Reactivity was observed only with isolates from species comprising the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex. For two MAbs, reactivity was also observed with isolates belonging to species different from that of the strain which was used for generating the respective MAb. This observation supports an initial hypothesis (22) that O-antigenic determinants recognized by some antibodies may be present in more that one genomic group. With the generation of more O-antigen-specific MAbs in the future, it will be possible to clarify which determinants are specific for a given genomic group and which are not. So far, these are the only two MAbs which have shown cross-species reactivity.

Using a novel method to visualize any LPS via its lipid A moiety (the antigenicity of which is exposed only after acid hydrolysis) with antibody in Western blotting (21), it was possible to tentatively identify additional O serotypes among those isolates from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex which had not reacted with any of the O antigen-specific MAbs used in this study. A total of 28 additional banding patterns were observed. Although most of the banding patterns obtained after acid hydrolysis were distinguishable from each other and from the patterns observed for isolates from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex which had reacted with the O antigen-specific MAbs, some patterns were found to be highly similar. Four of the banding patterns observed for A. baumannii isolates were indistinguishable from patterns observed for the other Acinetobacter species within the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex, namely, A. calcoaceticus (one pattern), Acinetobacter genomic species 3 (two patterns), and Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU (one pattern). Since the acid hydrolysis method does not give information as to the chemical compositions of the polysaccharide chains, it is uncertain whether these O antigens are indeed identical. Detailed biochemical and serological analyses of those polysaccharides which displayed similar banding patterns will be necessary to determine whether they are structurally and antigenically identical. However, those isolates from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex which displayed a distinct banding pattern after acid hydrolysis have already provided a basis for future immunizations and screening strategies. The lack of detection of a banding pattern for all isolates (Table 1) which were subjected to the acid hydrolysis method has also been observed in previous studies (24, 25). The exact reason for this phenomenon is still uncertain but may be explained by these isolates having a severely reduced level of O-antigen expression, e.g., due to so far unidentified cultivation requirements, or by these isolates naturally producing LPS which does not contain an O antigen.

In this study, we have thus generated O-antigen-specific MAbs and shown that they are readily useful for the identification of strains belonging to species from the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex, which comprises those species which are of the utmost clinical importance within the genus Acinetobacter at present. As shown recently (23), such antibodies could be adapted to the format of a latex agglutination test for practical use in clinical microbiology laboratories. Although the MAbs generated in the present study do not cover all the isolates that were tested, we were able to delineate further putative O serotypes among species of the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex, which will be useful in choosing future immunization strategies aimed at isolating antibodies specific for these additional serotypes. Whether MAbs against other members of the genus Acinetobacter are indeed necessary is certainly questionable, since most species are thought to represent colonization rather than infection (10, 28, 31). Therefore, although our studies do not exclude the generation of antibodies against non-A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex strains (26), they will continue to focus primarily on obtaining O-antigen-specific MAbs against the clinically important genomic groups, i.e., A. baumannii, Acinetobacter genomic species 3, and Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU, in order to fill current gaps. This will enable us to provide a complete O-serotyping scheme for these species, as has been successfully established for many other clinically significant gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, as has been reported in a recent study (27), such MAbs also have the potential to be employed as a means to define the prevalence of Acinetobacter serotypes in clinical settings and for the facile tracing of strains causing outbreaks in hospitals.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank B. van Harsselaar, M. Willen, V. Susott, U. Agge, D. Meyer, and S. Cohrs for technical assistance. We also thank A. Horrevorts (Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, The Netherlands), W. D. H. Hendriks (Zuiderziekenhuis, Rotterdam, The Netherlands), B. T. Lim (Regional Laboratory of Medical Microbiology, Dordrecht, The Netherlands), M. Vaneechoutte (Department of Clinical Chemistry, Microbiology and Immunology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium), K. Towner (Public Health Laboratory Service, University Hospital, Queen’s Medical Center, Nottingham, United Kingdom), T. L. Pitt (Laboratory of Hospital Infection, Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom), P. Gerner-Smidt (Department of Clinical Microbiology, Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark), H. Seifert (Institute of Medical Microbiology and Hygiene, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany), H. J. Grundmann (Institute of Environmental Medicine and Hospital Hygiene, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany), S. Schubert (Department of Medical Microbiology and Virology, Kiel University Hospital, Kiel, Germany), E. Savov (Department of Clinical Microbiology, Military Medical Academy, Sofia, Bulgaria), M. Fleischer (Department of Microbiology, Academy of Medicine, Wroclaw, Poland), L. Kiss (Laboratory of Bacteriology, Hajdu-Bihar County Institute, National Public Health Service, Debrecen, Hungary), J. Vila (Laboratori de Microbiologia, Institut d’ Investigació Biomèdica August Pi i Sunyer, Hospital Clínic, Facultat de Medicina, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain), L. Dolzani (Istituto di Microbiologia, Università degli Studi, Trieste, Italy), M. Gennari (Istituto di Ispezione degli Alimenti di Origine Animale, Facoltà di Medicina Veterinaria, Università degli Studi, Milan, Italy), and N. El-Khizzi (Division of Microbiology, Armed Forces Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) for providing some of the original Acinetobacter cultures or clinical specimens that were investigated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergogne-Bérézin, E., and K. J. Towner. 1996. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:148–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernards, A. T., A. T. de Beaufort, L. Dijkshoorn, and C. P. A. van Boven. 1997. Outbreak of septicaemia in neonates caused by Acinetobacter junii investigated by amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis (ARDRA) and four typing methods. J. Hosp. Infect. 35:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvet, P. J. M., and P. A. D. Grimont. 1986. Taxonomy of the genus Acinetobacter with recognition of Acinetobacter baumannii sp. nov.,Acinetobacter haemolyticus sp. nov., Acinetobacter johnsonii sp. nov., and Acinetobacter junii sp. nov. and amended descriptions of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter lwoffii. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 36:228–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvet, P. J. M., and S. Jeanjean. 1989. Delineation of new proteolytic genomic species in the genus Acinetobacter. Res. Microbiol. 140:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dijkshoorn, L., I. Tjernberg, B. Pot, M. F. Michel, J. Ursing, and K. Kersters. 1990. Numerical analysis of cell envelope protein profiles of Acinetobacter strains classified by DNA-DNA hybridization. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 13:338–344. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dijkshoorn, L., R. van Dalen, A. van Ooyen, D. Bijl, I. Tjernberg, M. F. Michel, and A. M. Horrevorts. 1993. Endemic Acinetobacter in intensive care units: epidemiology and clinical impact. J. Clin. Pathol. 46:533–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dijkshoorn, L., H. M. Aucken, P. Gerner-Smidt, M. E. Kaufmann, J. Ursing, and T. L. Pitt. 1993. Correlation of typing methods for Acinetobacter isolates from hospital outbreaks. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:702–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkshoorn, L. 1996.Acinetobacter—microbiology, p.37–69. In E. Bergogne-Bérézin, M. L. Joly-Guillou, and K. J. Towner (ed.), Acinetobacter: microbiology, epidemiology, infections, management. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 9.Dijkshoorn, L., H. Aucken, P. Gerner-Smidt, P. Janssen, M. E. Kaufmann, J. Garaizar, J. Ursing, and T. L. Pitt. 1996. Comparison of outbreak and nonoutbreak Acinetobacter baumannii strains by genotypic and phenotypic methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1519–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gennari, M., and P. Lombardi. 1993. Comparative characterization of Acinetobacter strains isolated from different foods and clinical sources. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 279:553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerner-Smidt, P. 1992. Ribotyping of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2680–2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerner-Smidt, P., and I. Tjernberg. 1993.Acinetobacter in Denmark. II. Molecular studies of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex. APMIS 101:826–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerner-Smidt, P., I. Tjernberg, and J. Ursing. 1991. Reliability of phenotypic tests for identification of Acinetobacter species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glew, R. H., R. C. Moellering, and L. J. Kunz. 1977. Infections with Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Herellea vaginicola): clinical and laboratory studies. Medicine 56:79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoppe, M., J. Potel, and R. Malottke. 1983. Clinical importance of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus isolations from blood cultures and venous catheters. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 256:80–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horrevorts, A., K. Bergman, L. Kollée, I. Breuker, I. Tjernberg, and L. Dijkshoorn. 1995. Clinical and epidemiological investigations of Acinetobacter genomospecies 3 in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1567–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juni, E. 1984. Acinetobacter, Brisou and Prévot 1954, 727AL, p.303–307. In N. R. Krieg (ed.), Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 1. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 18.Kuhn, H.-M., L. Brade, B. J. Appelmelk, S. Kusumoto, E. T. Rietschel, and H. Brade. 1992. Characterization of the epitope specificity of murine monoclonal antibodies directed against lipid A. Infect. Immun. 60:2201–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nemec, A., L. Janda, O. Melter, and L. Dijkshoorn. 1999. Genotypic and phenotypic similarity of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in the Czech Republic. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemec, A., T. de Baere, I. Tjernberg, M. Vaneechoutte, T. J. K. van der Reijden, and L. Dijkshoorn. 2001. Acinetobacter ursingii sp. nov. and Acinetobacter schindleri sp. nov., isolated from human clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1891–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pantophlet, R., L. Brade, and H. Brade. 1997. Detection of lipid A by monoclonal antibodies in S-form lipopolysaccharide after acidic treatment of immobilized LPS on Western blot. J. Endotoxin Res. 4:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pantophlet, R., L. Brade, L. Dijkshoorn, and H. Brade. 1998. Specificity of rabbit antisera against lipopolysaccharide of Acinetobacter. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1245–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pantophlet, R. 1999. Serological characterization of poly- and monoclonal antibodies against O-polysaccharides of Acinetobacter lipopolysaccharides. Ph.D. thesis. Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands.

- 24.Pantophlet, R., L. Brade, and H. Brade. 1999. Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii strains with monoclonal antibodies against the O antigens of their lipopolysaccharides. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pantophlet, R., L. Brade, and H. Brade. 1999. Use of a murine O-antigen-specific monoclonal antibody to identify Acinetobacter strains of unnamed genomic species 13 Sensu Tjernberg and Ursing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1693–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pantophlet, R., L. Brade, and H. Brade. 2001. Generation and serological characterization of murine monoclonal antibodies against O antigens from Acinetobacter reference strains. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:825–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pantophlet, R., A. Nemec, L. Brade, H. Brade, and L. Dijkshoorn. 2001. O-antigen diversity among Acinetobacter baumannii strains from the Czech Republic and Northwestern Europe, as determined by lipopolysaccharide-specific monoclonal antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2576–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seifert, H., R. Baginski, A. Schulze, and G. Pulverer. 1993. The distribution of Acinetobacter species in clinical culture materials. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 279:544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seifert, H., A. Strate, A. Schulze, and G. Pulverer. 1993. Vascular catheter-related bloodstream infection due to Acinetobacter johnsonii (formerly Acinetobacter calcoaceticus var. lwoffii): report of 13 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 17:632–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seifert, H., and P. Gerner-Smidt. 1995. Comparison of ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for molecular typing of Acinetobacter isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1402–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seifert, H., L. Dijkshoorn, P. Gerner-Smidt, N. Pelzer, I. Tjernberg, and M. Vaneechoutte. 1997. Distribution of Acinetobacter species on human skin: comparison of phenotypic and genotypic identification methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2819–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tjernberg, I., and J. Ursing. 1989. Clinical strains of Acinetobacter classified by DNA-DNA hybridization. APMIS 97:595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Towner, K. J. 1997. Clinical importance and antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter spp. J. Med. Microbiol. 46:721–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vila, J., J. Ruiz, M. Navia, B. Becerril, I. Garcia, S. Perea, I. Lopez-Hernandez, I. Alamo, F. Ballester, A. M. Planes, J. Martinez-Beltran, and T. Jimenez de Anta. 1999. Spread of amikacin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated in Spain due to an epidemic strain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:758–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vinogradov, E. V., R. Pantophlet, L. Dijkshoorn, L. Brade, O. Holst, and H. Brade. 1996. Structural and serological characterization of two O-specific polysaccharides from Acinetobacter. Eur. J. Biochem. 239:602–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westphal, O., and K. Jann. 1965. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Extraction with phenol-water and further applications of the procedure. Methods Carbohydr. Chem. 5:83–91. [Google Scholar]