Abstract

The principal objective of the present study was to identify specific alterations in mitochondrial respiratory functions during the aging process. Respiration rates and the activities of electron transport chain complexes were measured at various ages in mitochondria isolated from thoraces of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, which consist primarily of flight muscles. The rates of state 3 respiration (ADP-stimulated), RCRs (respiratory control ratios) and uncoupled respiration rates decreased significantly as a function of age, using either NAD+- or FAD-linked substrates; however, there were no differences in state 4 respiration (ADP-depleted) rates. There was also a significant age-related decline in the activity of cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV), but not of the other mitochondrial oxidoreductases examined. Exposure of mitochondria isolated from young flies to low doses of KCN or NaAz (sodium azide), complex IV inhibitors, decreased cytochrome c oxidase activity and increased the production of H2O2. Collectively, these results support the hypothesis that impairment of mitochondrial respiration may be a causal factor in the aging process, and that such impairment may result from and contribute to increased H2O2 production in vivo.

Keywords: cytochrome c oxidase, Drosophila melanogaster, electron transport, mitochondria, mitochondrial respiration, reactive oxygen species

Abbreviations: ANT, adenine nucleotide translocator; CCCP, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone; coxI, complex IV subunit I; DNP, 2,4-dinitrophenol; DTNB, 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid); FCCP, carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; α-GP, α-glycerophosphate; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; NaAz, sodium azide; PHPA, p-hydroxyphenylacetate; RCR, respiratory control ratio; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase

INTRODUCTION

The nature of the mechanisms underlying the aging process is presently unclear; however, the age-related deterioration of functions associated with mitochondria has been suggested to play a major role in this process [1]. Besides being the main site of ATP production, mitochondria are the predominant intracellular generators of ROS (reactive oxygen species), specifically superoxide anion radical (O2•−) and its stoichiometric product, H2O2 [2,3]. The latter molecule can diffuse readily through cellular membranes and undergo scission to produce the highly reactive hydroxyl free radical, which is capable of causing a variety of macromolecular oxidative modifications. Accumulation of such oxidative damage has been widely postulated to be a primary causal factor in the aging process, and mitochondria are considered to be the most immediate targets of oxidative damage [1,4]. In support of this view, mitochondrial ROS production and oxidative damage increase as a function of age [5–10]. In addition, in vitro exposure of isolated mitochondria to ROS causes a variety of deleterious alterations in mitochondrial respiratory functions [11]. Conversely, the impairment of electron transfer between oxidoreductases of the mitochondrial electron transport chain causes the upstream components to become more electron-laden and susceptible to autoxidation, thereby decreasing respiratory activity and enhancing ROS production [7,9]. It remains unclear whether there is a causal link between age-related changes in respiratory activity, including the function of the oxidoreductases, and increased rates of ROS production in older animals. Thus the identification of specific age-associated changes in mitochondrial respiratory functions might help to explain the basis of the contemporaneous increases in O2•−/H2O2 generation.

In mammals, including humans, defects in the electron transport chain clearly contribute to the aetiology of several disease states; however, investigations of whether similar defects occur during normal aging have yielded inconsistent results [12–20]. Similarly, in insects, there is a considerable amount of contradictory evidence, with some studies reporting a decline in oxygen consumption and/or alterations in electron transport chain complex activities with increasing age, whereas others report no significant age-related alterations [21–25]. Although several possibilities have been raised to explain such discordant findings, the most frequently implicated are age-associated increases in mitochondrial fragility, damage during isolation and inadequate verification of mitochondrial purity. Indeed, Maklashina and Ackrell [26] have recently challenged the very notion that there is any age-associated defect in mitochondrial respiration, because the majority of studies reporting such defects omitted internal markers for the purity and yield of mitochondrial preparations. Consequently, no straightforward answer exists to the question whether or not mitochondrial respiratory function and/or electron transport are compromised during aging.

Insects are a uniquely well-suited class of animals in which this question can be addressed, because flying insects with asynchronous flight muscles undergo dramatic decreases in both wing-beat frequency and the capacity for sustained flight as a function of age [27,28]. Thus any association between age-related changes in mitochondrial respiratory activities and physiological function should be apparent in such a model. Additionally, due to the presence of tracheolar invaginations, insect tissues are exposed directly to air, and thus to a much higher oxygen concentration than mammalian tissues [29]. Mitochondria isolated from insects also generate O2•−/H2O2 at relatively rapid rates [7,10]. Although Drosophila melanogaster is a comparatively small insect, the availability of genetic tools from studies of its development and aging has made it the main model for gerontological research among arthropods. Accordingly, thoraces of D. melanogaster, which consist primarily of flight muscle, were used as a source of mitochondria for the measurement of changes in respiration rates and activities of oxidoreductases within the electron transport chain as a function of age, incorporating the activity of citrate synthase as a control for mitochondrial purity and yield. There was a decrease in mitochondrial respiratory capacity with increasing age, as well as a decrease in cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) activity, both of which may result from and contribute to an age-related increase in oxidative stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All chemicals were of reagent grade and purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), unless noted otherwise. Ferrocytochrome c was prepared as described by Trounce et al. [30]. Acetyl-CoA was prepared as described by Robinson et al. [31].

Animals

A relatively long-lived y w strain of D. melanogaster in an Oregon R background was used in these studies (mean life span ∼70 days). Male flies were collected 1±1 day post-eclosion, using brief exposure to carbon dioxide anaesthesia, and were subsequently maintained in groups of 25 at 25 °C under constant light. The flies were transferred to vials containing fresh cornmeal–sucrose–yeast medium every 1–2 days initially and every single day beyond 30 days of age.

Isolation of mitochondria

For measurements of mitochondrial respiration plus citrate synthase activity, groups of 125–200 male flies/substrate were used. Live flies were chilled briefly on ice and thoraces were severed from the heads and abdomens. Isolated thoraces were placed in a chilled mortar, containing 300–400 μl of ice-cold isolation buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.3), to which 2% (w/v) BSA (fatty acid content <0.003%) had been added. The thoraces were pounded gently without shearing to release mitochondria, and the preparation was maintained at 0–5 °C throughout subsequent washing and centrifugation procedures. The brei was filtered through Spectra/Mesh® nylon (pore size=10 μm), and the volume was raised to 1.5 ml by washing the nylon membrane with an additional isolation buffer. After centrifugation for 10 min at 2200 g, the pellet was rinsed briefly in BSA-free isolation buffer, and then resuspended in 1.0 ml of the BSA-free buffer. The centrifugation was repeated and the mitochondria were then resuspended in 240–300 μl of BSA-free isolation buffer. For measurements of the activities of respiratory complexes I, I/III, II/III and IV, plus citrate synthase, groups of 75 flies were used, and mitochondria were prepared as described for mitochondrial respiration, with the following modifications: (i) BSA-free buffer was used throughout the isolation procedure (150–200 μl for pounding of thoraces) and (ii) after a single centrifugation for 10 min at 2200 g, the pellet was resuspended in 180 μl of buffer.

Citrate synthase activity

Citrate synthase activity was measured as the increase in absorbance due to the reduction of DTNB [5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)] at 412 nm, coupled to the reduction of CoA by citrate synthase in the presence of oxaloacetate (molar absorption coefficient, ϵ=13.6 mM−1·cm−1), as described by Robinson et al. [31]. The absorbance of the reaction mixture (100 μM DTNB, 0.3 mg of acetyl-CoA and 2–10 μg of sonicated mitochondria or crude homogenate) was followed for 2 min to determine the acetyl-CoA hydrolase activity present in the sample. Oxaloacetic acid (500 μM) was added to initiate the reaction and the increase in absorbance was monitored for an additional minute. Citrate synthase activity was calculated by subtracting the rate of the reaction due to acetyl-CoA hydrolase activity from the rate after the addition of oxaloacetic acid. To determine whether the isolation procedures employed in the present study affected the yield and purity of mitochondrial preparations, a comparison was made between mitochondrial respiration rates and the activities of oxidoreductases before and after normalizing to citrate synthase activity, as well as measuring citrate synthase activity in crude homogenates.

Mitochondrial respiration

Rates of mitochondrial respiration (state 3, ADP-stimulated; state 4, ADP-deleted; and uncoupled respiration) were determined polarographically using a Clark-type oxygen electrode connected to the computer-operated Oxygraph control unit (Hansatech Instruments, Norfolk, U.K.). For all the experiments, the temperature was maintained at 28 °C and the total reaction volume was 1.0 ml. Freshly isolated mitochondria (30–60 μg of protein) were added to the respiration buffer (120 mM KCl, 5 mM potassium phosphate, 3 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.2% BSA, pH 7.2) and allowed to equilibrate for 1 min. Either an NAD+-linked substrate (10 mM pyruvate plus 10 mM malate, or 10 mM pyruvate plus 10 mM proline) or FAD-linked substrate [10 mM α-GP (α-glycerophosphate) or 10 mM succinate] was then added to the chamber and allowed to equilibrate for 1 min, followed by the addition of ADP (100 μM final concentration).

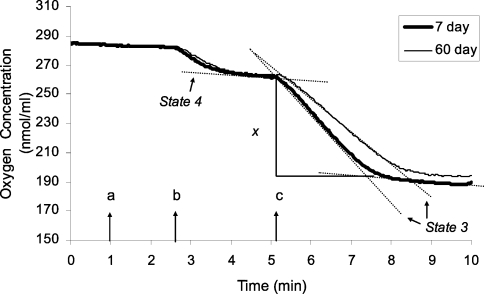

In measurements involving NAD+-linked substrates, after the removal of ADP by conversion to ATP (state 4 respiration), a second addition of ADP (400 μM) was made and the resulting slope was used to calculate the rate of state 3 respiration (Figure 1). To preclude the possibility that depletion of O2 in the reaction chamber could artificially diminish state 4 respiration, this rate was calculated after the first addition of ADP was depleted (Figure 1). However, there was no consistent difference between state 4 respiration rates measured before and after the second addition of ADP. For FAD-linked substrates, the transition between state 3 and state 4 respiration was unclear (Figure 2); therefore only one addition of 100 μM ADP was made to induce state 3 respiration, and 1–2 μg of oligomycin was added to inhibit ATP synthase and determine the rate of state 4 respiration. The RCR (respiratory control ratio) was calculated as the ratio of state 3 to state 4 respiration. The ADP/O ratio was calculated from the amount of oxygen consumed during state 3 respiration and the concentration of ADP (400 μM; Figure 1). In a fresh sample aliquot, the rate of uncoupled respiration was determined by adding 200 μM DNP (2,4-dinitrophenol), after the recovery from an initial addition of 100 μM ADP. All measurements of respiration were performed in triplicate, within 1 h after the isolation of mitochondria, and both the RCR and ADP/O ratios remained stable during this time interval.

Figure 1. Representative oxygen-electrode traces of mitochondria from flight muscles of Drosophila respiring on NAD+-linked substrates.

Mitochondria were isolated from thoraces of 7- and 60-day-old flies. The incubation mixture consisted of 30 μg of protein, 120 mM KCl, 5 mM potassium phosphate, 3 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.2% BSA (pH 7.2). Substrates (10 mM pyruvate plus 10 mM proline) were added at point a, 100 μM ADP at point b and 400 μM ADP at point c. For NAD+-linked substrates, the rate of state 3 respiration was measured as the slope after the addition of 400 μM ADP. To preclude the possibility that depletion of O2 in the reaction chamber could artificially diminish state 4 respiration, this rate was calculated after the first addition of 100 μM ADP was depleted. The ADP/O ratio was calculated from the amount of oxygen (x) consumed during state 3 respiration: [ADP]/(x×2).

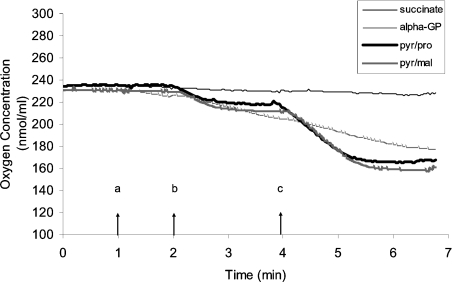

Figure 2. Representative oxygen-electrode traces of Drosophila mitochondria respiring on FAD- and NAD+-linked substrates.

Mitochondria were isolated from thoraces of 10-day-old flies. The reaction mixture consisted of 30 μg of protein, 120 mM KCl, 5 mM potassium phosphate, 3 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.2% BSA (pH 7.2). Substrates (10 mM succinate, 10 mM α-GP, 10 mM pyruvate plus 10 mM proline or 10 mM pyruvate plus 10 mM malate) were added at point a, 100 μM ADP at point b and 400 μM ADP at point c.

In these studies, DNP was used to uncouple mitochondria for the following reasons: (i) in Drosophila mitochondria, the rates of uncoupled respiration were the same or higher with DNP, as compared with uncoupled respiration rates with FCCP (carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone) or CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone); (ii) the use of DNP avoids the addition of ethanol or DMSO to the sample (FCCP and CCCP are not soluble in water), which could potentially alter mitochondrial properties; and (iii) in addition to uncoupling mitochondria, FCCP and CCCP can inhibit enzymes containing thiol groups [32]; therefore the use of DNP avoids any confounding that may occur with the use of those inhibitors.

Oxidoreductase activities

The activities of the electron transport chain complexes were measured in sonicated mitochondrial preparations containing both the matrix and membrane fractions. Before sonication, mitochondrial suspensions were diluted to 1 mg/ml with hypotonic buffer (30 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4). They were then sonicated on ice for 3×30 s (output power 40–60 W, 30% duty cycle), with a 1 min rest period between cycles, using a Branson Sonifier 250 equipped with a microtip (Branson, Danbury, CT, U.S.A.).

The activities of all complexes were measured in triplicate at 30 °C, in a total reaction volume of 1 ml, using a Beckman DU-640 spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Spinco Division, Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.), as previously described [16,30]. For complexes I, I/III and IV, the measurements were repeated using at least two separate cohorts of flies to verify the results.

The activity of NADH-dehydrogenase (complex I) was measured as the decrease in absorbance due to the oxidation of NADH at 340 nm, with 425 nm as the reference wavelength (ϵ=6.81 mM−1·cm−1). The absorbance of the reaction mixture (25 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM KCN, 2.5 mg of BSA, 100 μM NADH, 100 μM ubiquinone-2 and 2 μg of antimycin A) was measured for 1 min to monitor the stability of the reagents and allow the temperature to equilibrate. The addition of sonicated mitochondria (5–10 μg of protein) initiated the reaction and the decrease in absorbance was monitored for 2 min, after which rotenone (15 μM final concentration) was added and the absorbance was monitored for 2 min. Complex I activity reported here is the rotenone-sensitive rate.

The activity of NADH-cytochrome c oxidoreductase (complexes I/III) was measured as the increase in absorbance due to the reduction of ferricytochrome c at 550 nm, with 580 nm as the reference wavelength (ϵ=19 mM−1·cm−1). The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), 80 μM horse heart cytochrome c, 100 μM NADH, 2 mM KCN and 5 mM MgCl2. The reaction was initiated by the addition of sonicated mitochondria (5–15 μg of protein) and the increase in absorbance was monitored for 2 min, after which rotenone (3.75 μM final concentration) was added and the absorbance was monitored for an additional minute. The complexes I/III activity reported here is the rotenone-sensitive rate.

The activities of succinate- and α-GP-cytochrome c oxidoreductases (complexes II/III) were also determined as the increase in absorbance due to the reduction of ferricytochrome c at 550 nm, with 580 nm as the reference wavelength (ϵ=19 mM−1·cm−1). The reaction mixture (40 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 20 mM succinate or 20 mM α-GP, 3.75 μM rotenone, 2 mM KCN and 0.5 mM EDTA) was incubated with sonicated mitochondria (2–10 μg of protein) for 20 min to allow for complete activation of succinate and α-GP dehydrogenases, after which the reaction was initiated with 30 μM horse heart cytochrome c and monitored for 2 min.

Cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) activity was measured by following the decrease in absorbance due to the oxidation of ferrocytochrome c at 550 nm, with 580 nm as the reference wavelength (ϵ=27.7 mM−1·cm−1). The absorbance of the reaction mixture (10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.45 μM dodecyl maltoside and 15 μM ferrocytochrome c) was measured for 1 min to monitor the stability of the reagents and allow the temperature to equilibrate. The reaction was then initiated by adding sonicated mitochondria (1–5 μg of protein), and the decrease in absorbance was monitored for an additional 30 s.

Electrophoresis and Western blotting

Electrophoresis of mitochondrial samples was performed using a discontinuous SDS/PAGE system, as described by Schagger and von Jagow [33]. Briefly, 10 μg of mitochondrial protein was boiled for 3 min in sample buffer [0.1 M Tris/HCl (pH 6.8), 24% (v/v) glycerol, 8% (w/v) SDS, 0.02% Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 and 0.2 M dithiothreitol], and then separated on a 10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel, using tricine as the trailing ion. Gels were then stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 or processed for immunoblotting.

For immunoblotting, the separated proteins were transferred on to PVDF membranes (Immobilon™-P) at 100 V for 1 h in a buffer containing 16 mM Tris, 120 mM glycine and 10% (v/v) methanol. The membranes were then blocked for 1 h at 37 °C in 5% (w/v) non-fat milk in TTBS (10 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20), followed by an incubation for 1 h at 37 °C with the primary antibody (1:5000, anti-OxPhos, Complex IV subunit I; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). The membranes were washed for 4×5 min in TTBS both before and after the 1 h (37 °C) incubation with the secondary antibody (1:5000, anti-mouse; Pierce, Rockford, IL, U.S.A.). Proteins were visualized using the ECL-Plus™ Western-blotting detection kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.) and the density of the bands was quantified using a computer-assisted densitometry system (NIH ImageJ). Each sample was measured in duplicate or triplicate. The blots were reprobed with an antibody raised against recombinant Cu,Zn-SOD (superoxide dismutase) (1:5000; Berkeley Antibody, Richmond, CA, U.S.A.), and compared with the Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained gels, to ensure that sample loading volumes were equal. Cu,Zn-SOD was chosen as a loading control because there was no change in Cu,Zn-SOD protein concentration during aging [53].

Mitochondrial H2O2 production

The rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production in intact mitochondria was measured fluorometrically, as described previously [3]. Briefly, H2O2 release was monitored by the increase in fluorescence (excitation wavelength=320 nm and emission wavelength=400 nm) due to the oxidation of PHPA (p-hydroxyphenylacetate), coupled to the horseradish peroxidase-mediated enzymatic reduction of H2O2. Known concentrations of H2O2 were used to establish the standard curve. The reaction mixture consisted of 154 mM KCl, 10 mM potassium phosphate, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA (pH 7.4), 20–40 μg of mitochondrial protein, 166 μg/ml PHPA and 1.3 units/ml horseradish peroxidase. After equilibration at 30 °C, 7 mM α-GP and 1.5 μM rotenone were added to the reaction mixture, followed by increasing concentrations of KCN to inhibit complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) activity and to measure the effect of complex IV inhibition on H2O2 production. To corroborate the results, the experiment was repeated using NaAz (sodium azide), an alternative inhibitor of cytochrome c oxidase. In addition, a negative control containing all the contents of the reaction mixture, except mitochondria, was used to verify that the increase in fluorescence was not simply an artifact of the KCN or NaAz addition.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means of individual samples measured in duplicate or triplicate. Linear regression analysis was used to determine the significance of age-related changes, with P=0.05 as the threshold of statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SYSTAT 10 software.

RESULTS

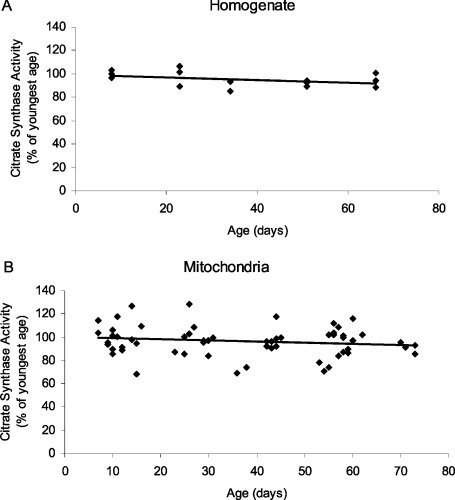

Mitochondrial yield and purity are stable as a function of age

The activity of citrate synthase, an enzyme located in the mitochondrial matrix, was measured in order to determine whether there was an age-dependent variation in the yield and purity of mitochondrial preparations. Citrate synthase activity remained stable as a function of age, both in crude homogenates and mitochondrial preparations (Figure 3), suggesting that the isolation procedures used in this study provided mitochondrial preparations of comparable purity at different ages.

Figure 3. Citrate synthase activity in (A) homogenates and (B) mitochondria of D. melanogaster at different ages.

The activity was measured as the change in absorbance of DTNB, in the presence of CoA and oxaloacetate, and used as a control for the purity and yield of mitochondrial preparations in this study. Linear regression analysis revealed no significant age-related changes in the activity of citrate synthase (P=0.1, homogenate; P=0.2, mitochondria).

D. melanogaster mitochondria utilize NAD+- and FAD-linked substrates differently

Results of initial experiments using a single mitochondrial preparation from 10-day-old flies indicated distinct differences between NAD+- and FAD-linked respiration and these differences persisted at older ages (Figure 2). First, the rate of mitochondrial respiration with succinate (FAD-linked) was very low, which is consistent with earlier reports suggesting that succinate does not readily cross the inner mitochondrial membrane [34]. In contrast, respiration rates were much higher in the presence of α-GP (also FAD-linked) and two NAD+-linked substrate pairs (pyruvate plus proline and pyruvate plus malate). Secondly, the transition between state 3 and state 4 respiration was more clearly demarcated for pyruvate plus proline and pyruvate plus malate, as compared with α-GP (Figure 2), which is also consistent with previous findings [34]. Accordingly, in subsequent experiments, oligomycin was used to induce state 4 respiration in mitochondria utilizing α-GP as the substrate.

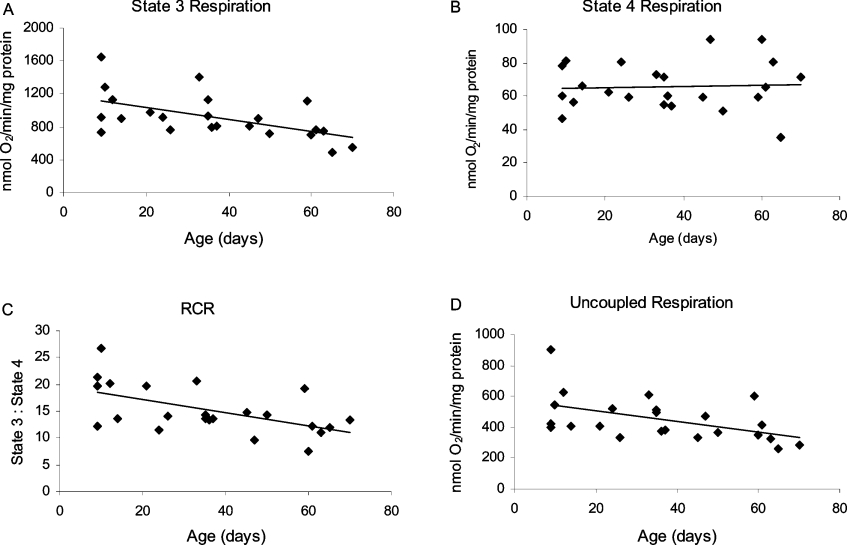

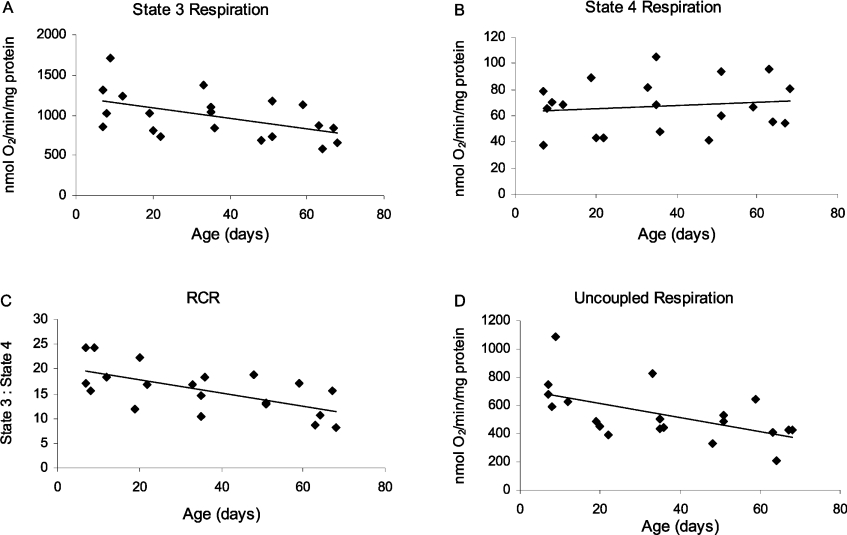

NAD+-linked mitochondrial respiratory efficiency decreases with increasing age

The effects of aging on mitochondrial respiration (state 3, state 4 and uncoupled respiration rates, RCR and ADP/O ratios) were examined in Drosophila using NAD+-linked substrates (Figures 1, 4 and 5). Representative traces of mitochondrial respiration in 7- and 60-day-old flies are shown in Figure 1, illustrating a significant, age-related decrease in the rate of state 3, but not state 4 respiration. Based on linear regression analysis of the data, the magnitude of the decrease in state 3 respiration between 10 and 65 days of age was 36% for pyruvate plus proline (Figure 4A, P=0.006) and 31% for pyruvate plus malate (Figure 5A, P=0.03). However, no age-related changes were discernable in state 4 respiration with either of the substrate pairs (Figures 4B and 5B). Consequently, there was a significant decrease in RCR for both pyruvate plus proline (Figure 4C, P=0.006) and pyruvate plus malate (Figure 5C, P=0.003). The high RCR values (Figures 4C and 5C) and ADP/O ratios (results not shown) also suggest that the structural and functional integrity of the mitochondrial preparations was preserved throughout these experiments.

Figure 4. Pyruvate plus proline-stimulated respiration of Drosophila mitochondria at different ages.

(A) State 3 respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM pyruvate and 10 mM proline, and in the presence of 400 μM ADP. (B) State 4 respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM pyruvate and 10 mM proline, and after the depletion of 100 μM ADP. (C) RCRs were calculated as ratios of state 3 respiration to state 4 respiration. (D) Uncoupled respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM pyruvate and 10 mM proline, depletion of 100 μM ADP and in the presence of 200 μM DNP. Linear regression analysis revealed a significant age-related decrease in state 3 respiration (P=0.006), RCR (P=0.006), and uncoupled respiration (P=0.02), but not in state 4 respiration (P=0.8). Data are presented as means of individual samples measured in triplicate; the significance values of means normalized to citrate synthase activity are shown in Table 1.

Figure 5. Pyruvate plus malate-stimulated respiration of Drosophila mitochondria at different ages.

(A) State 3 respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM pyruvate and 10 mM malate, and in the presence of 400 μM ADP. (B) State 4 respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM pyruvate and 10 mM malate, and after the depletion of 100 μM ADP. (C) RCR. (D) Uncoupled respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM pyruvate and 10 mM malate, depletion of 100 μM ADP and in the presence of 200 μM DNP. Linear regression analysis revealed a significant age-related decrease in state 3 respiration (P=0.03), RCR (P=0.003), and uncoupled respiration (P=0.01), but not in state 4 respiration (P=0.6). Data are presented as means of individual samples measured in triplicate.

Treatment of mitochondria with the uncoupler, DNP, causes a collapse of the mitochondrial proton electrochemical potential gradient and allows mitochondrial respiration to occur in the absence of ATP synthesis, at maximum capacity, until all the oxygen has been consumed. There was a significant age-related decrease in the rate of mitochondrial respiration in the presence of DNP, using either pyruvate plus proline (Figure 4D, P=0.02) or pyruvate plus malate (Figure 5D, P=0.01) as substrate. The magnitude of the decrease between 10 and 65 days of age, based on the linear regression equation, was 30–40% for both substrate pairs. Furthermore, normalizing the respiration rates and RCR for pyruvate plus proline to citrate synthase activity did not alter the significance levels (Table 1). For pyruvate plus malate, only two out of five sets of samples were normalized to citrate synthase, due to the limited sample sizes of the other preparations; therefore no comparison of significance levels is presented for pyruvate plus malate.

Table 1. Comparison of significance levels before and after normalizing to citrate synthase activity.

There is no comparison of significance values for pyruvate plus malate because sample size only allowed citrate synthase activity to be measured in two out of the five sample sets.

| P values | ||

|---|---|---|

| Normalized to mitochondrial protein* | Normalized to citrate synthase activity* | |

| Pyruvate plus proline respiration | ||

| State 3 respiration | 0.006 | 0.01 |

| State 4 respiration | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| RCR | 0.006 | 0.03 |

| Uncoupled respiration | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| ADP/O | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| α-GP respiration | ||

| State 3 respiration | 0.008 | 0.03 |

| State 4 respiration | 0.4 | 0.07 |

| RCR | 0.001 | 0.04 |

| Uncoupled respiration | 0.005 | 0.03 |

| Oxidoreductase activity | ||

| NADH dehydrogenase | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| NADH-cytochrome c oxidoreductase | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| α-GP-cytochrome c oxidoreductase | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Succinate-cytochrome c oxidoreductase | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase | <0.0005 | <0.0005 |

FAD-linked mitochondrial respiratory efficiency decreases with increasing age

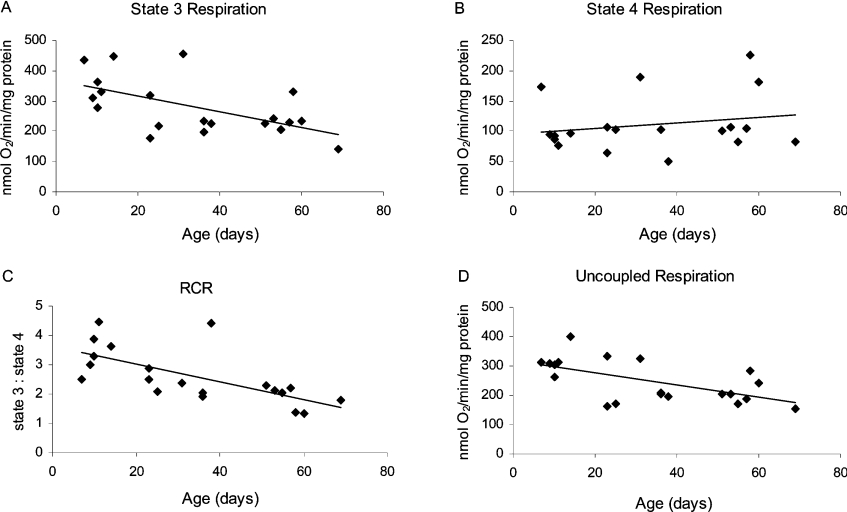

With α-GP as the substrate, there was a significant age-related decrease in state 3 respiration (Figure 6A, P=0.008), RCR (Figure 6C, P=0.001) and uncoupled respiration (Figure 6D, P=0.005), but no discernable change in state 4 respiration (Figure 6B), as described above for the NAD+-linked substrates. The magnitude of the decrease in state 3 respiration rate was 42%, versus 39% for uncoupled respiration. As indicated above, the transition to state 4 respiration was indistinct with α-GP as the substrate (Figure 2). Therefore the state 4 respiration rates and RCRs reported for α-GP were determined after the addition of oligomycin, and accurate ADP/O ratios could not be obtained. Normalizing the results to citrate synthase activity did not alter the significance levels (P<0.05 versus P≥0.05, Table 1).

Figure 6. α-GP-stimulated respiration of Drosophila mitochondria at different ages.

(A) State 3 respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM α-GP and in the presence of 100 μM ADP. (B) State 4 respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM α-GP, 100 μM ADP and 1–2 μg of oligomycin. (C) RCR. (D) Uncoupled respiration was measured after the addition of 10 mM α-GP, 100 μM ADP and 200 μM DNP. Linear regression analysis revealed a significant age-related decrease in state 3 respiration (P=0.008), RCR (P=0.001) and uncoupled respiration (P=0.005), but not in state 4 respiration (P=0.4). Data are presented as means of individual samples measured in triplicate; the significance values of means normalized to citrate synthase activity are shown in Table 1.

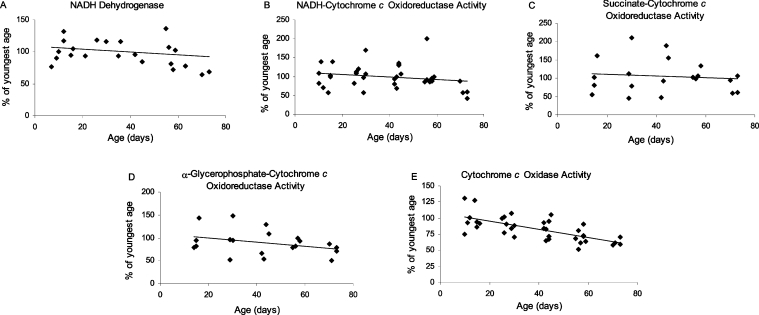

Cytochrome c oxidase activity decreases as a function of age

The activities of the mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes (oxidoreductases) were examined in sonicated mitochondrial preparations, containing both the matrix and membrane fractions (Figure 7). There were no significant differences in the activities of complex I (Figure 7A, P=0.3), complexes I/III (Figure 7B, P=0.2) or complexes II/III (Figures 7C and 7D, succinate, P=0.7; α-GP, P=0.2) as a function of age. In contrast, there was a significant decrease in the activity of cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) by 35% between the ages of 10 and 65 days (Figure 7E, P<0.0005). Furthermore, normalizing the activities of the respiratory complexes to citrate synthase activity did not alter the significance levels of the results (Table 1). Thus there was a specific, age-associated decline in the activity of complex IV, but not in the other respiratory complexes, and impurities in the mitochondrial preparations were excluded as a probable explanation for these results.

Figure 7. Activities of electron transport chain oxidoreductases in mitochondria isolated from thoraces of Drosophila at different ages.

Activities of the oxidoreductases were measured in sonicated mitochondrial preparations. (A) NADH dehydrogenase activity (complex I) was measured as the rotenone-sensitive rate of NADH oxidation at 340 nm, with 425 nm as the reference wavelength. (B) NADH-cytochrome c oxidoreductase activity (complexes I/III) was measured as the rotenone-sensitive rate of NADH-stimulated ferricytochrome c reduction at 550 nm, with 580 nm as the reference wavelength. (C) Succinate-cytochrome c oxidoreductase activity (complexes II/III) was measured as succinate-stimulated reduction of ferricytochrome c at 550 nm, with 580 nm as the reference wavelength. (D) α-GP-cytochrome c oxidoreductase activity (complexes II/III) was measured as the rate of α-GP-stimulated reduction of ferricytochrome c at 550 nm, with 580 nm as the reference wavelength. (E) Cytochrome c oxidase activity (complex IV) was measured as the rate of ferrocytochrome c oxidation at 550 nm, with 580 nm as the reference wavelength. Linear regression analysis revealed no significant age-related trends in the activities of complex I (P=0.3), complexes I/III (P=0.2) or complexes II/III (succinate, P=0.7; α-GP, P=0.2), but complex IV activity decreased 35% between 10 and 65 days of age (P<0.0005).

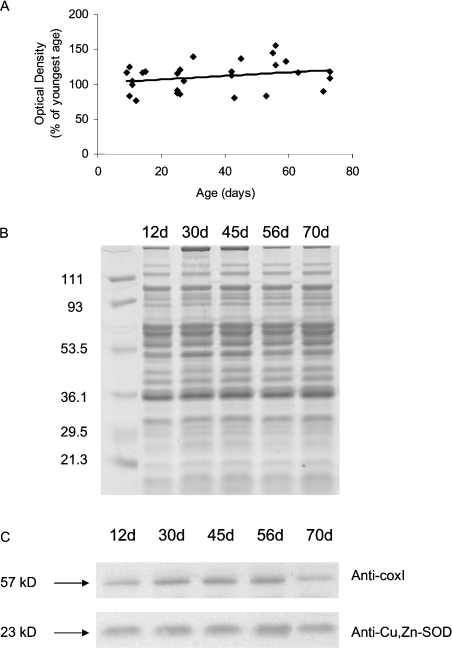

Cytochrome c oxidase protein levels do not change with age

Western-blot analysis of mitochondrial samples was used to determine whether an age-related decrease in complex IV protein abundance could contribute to the decrease in complex IV activity. There was no significant difference in the level of coxI (complex IV subunit I) protein as a function of age (Figure 8, P=0.2). These results were verified by using Cu,Zn-SOD, found in the cytosol and mitochondrial intermembrane space, as a loading control, as well as by comparing the blots with Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained gels. No difference was seen either in the protein levels of Cu,Zn-SOD or in total protein content on Coomassie-stained gels (Figures 8B and 8C). When the ratios of coxI and Cu,Zn-SOD densitometric values were examined, no changes in the significance levels were found (results not shown).

Figure 8. coxI protein levels determined by Western-blot analysis.

Mitochondria were isolated from thoraces of Drosophila at different ages (A) Quantification of densitometry data for coxI protein. Data were analysed using NIH ImageJ, with each data point representing the mean of an individual sample measured in duplicate or triplicate. (B) Representative Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained gel demonstrating the equal loading of proteins. (C) Representative Western blots of coxI protein (top panel) and Cu,Zn-SOD protein (bottom panel), which was used as a loading control for coxI.

In vitro inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase increases H2O2 production

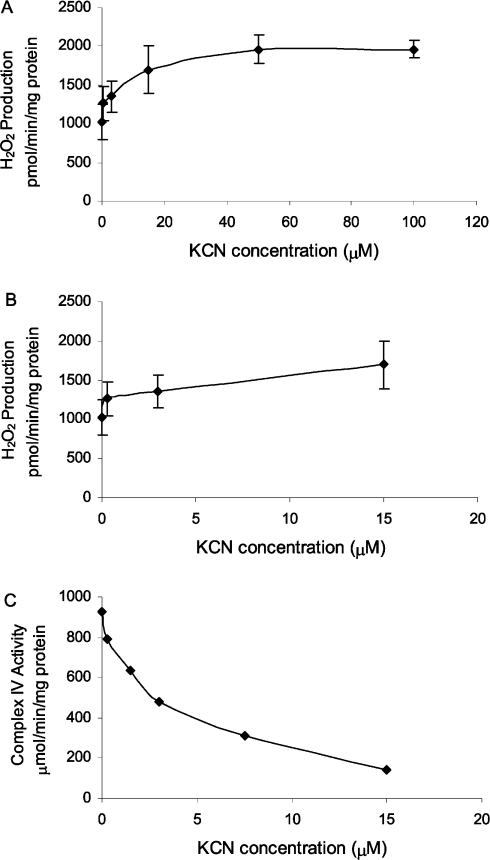

To determine whether the observed decrease in complex IV activity in aged flies could explain the previously reported, age-related increase in H2O2 production [7,10], the rate of H2O2 release from mitochondria was measured in the presence of increasing amounts of KCN, an inhibitor of complex IV activity. Titration of mitochondrial samples with increasing concentrations of KCN (0–100 μM) resulted in a doubling of the rate of H2O2 production (Figures 9A and 9B); however, H2O2 production ceased at KCN concentrations above 500 μM (results not shown). This finding is consistent with the previously reported effects of KCN on H2O2 release in housefly mitochondria [23]. Similar results were obtained using NaAz to inhibit complex IV activity (results not shown), but no increase in fluorescence was observed after the addition of KCN and NaAz if no mitochondrial protein was present in the reaction mixture (results not shown).

Figure 9. Effect of KCN on H2O2 production in Drosophila mitochondria in the presence of 7 mM α-GP and 1.5 μM rotenone (A, B), and on the activity of cytochrome c oxidase (C).

H2O2 release was monitored by the increase in fluorescence (excitation wavelength=320 nm; emission wavelength=400 nm) due to the oxidation of PHPA, coupled to the horseradish peroxidase-mediated enzymatic reduction of H2O2.

Additionally, sonicated preparations of mitochondria, isolated from 9–10-day-old flies, were titrated with different concentrations of KCN, and complex IV activity was measured. Complex IV activity decreased as the concentration of KCN increased (Figure 9C). In the presence of 3 μM KCN, there was a 48% decrease in complex IV activity and a 32% increase in H2O2 production (Figures 9B and 9C). There was a corresponding 40% decrease in complex IV activity in Drosophila between the ages of 10 and 70 days, suggesting that an age-associated increase in H2O2 production could arise, in part, from the concomitant loss of cytochrome c oxidase activity.

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed specifically to avoid potential pitfalls that may have compromised the results of some earlier investigations of mitochondrial respiration and/or oxidoreductase activities, by including the following procedures: (i) the avoidance of mechanical homogenization, in order to minimize damage that could result in mitochondrial uncoupling; (ii) the use of citrate synthase activity to control for differences in mitochondrial purity; (iii) the use of several different substrates in the investigation of mitochondrial respiratory activity; and (iv) the use of large samples of flies, from multiple cohorts at several different ages, with statistical analysis based on linear regression rather than pooling of results into arbitrary age groups. The main findings are that, in D. melanogaster: (i) there is no age-related decrease in citrate synthase activity; (ii) thoracic mitochondria differ in their ability to utilize NAD+- and FAD-linked substrates; (iii) there are age-associated decreases in state 3 respiration, RCR and uncoupled respiration, but no change in state 4 respiration, using either NAD+- or FAD-linked substrates; (iv) there is an age-associated decrease in complex IV activity, but no decline in the activities of complex I, complexes I/III or complexes II/III; and (v) experimental inhibition of complex IV activity results in increased H2O2 production.

A direct comparison of the rates of respiration using the different substrates employed in this study has not been made previously in D. melanogaster; however, the present results are in broad agreement with earlier findings in other insect species [35]. First, the use of succinate as a substrate resulted in extremely slow rates of respiration, which is consistent with the observation that citric acid cycle intermediates, including succinate, do not readily cross the mitochondrial membranes of insect flight muscle [34,35]. Secondly, in the presence of α-GP, the transition from state 3 to state 4 respiration was not distinctly identifiable. Thirdly, in this study, the rate of respiration was approx. 4-fold faster during pyruvate oxidation when compared with α-GP oxidation. This finding is consistent with the predicted rate of oxygen consumption during pyruvate oxidation, via the citric acid cycle, being five times greater than that during α-GP oxidation, in which glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase generates FADH2 [35]. Although earlier studies in blowflies found that oxygen is consumed at a higher rate during α-GP oxidation [36], these studies may not have employed ideal conditions for the measurement of pyruvate-based respiration.

State 4 respiration occurs when ADP is exhausted and represents the resting or basal state of the mitochondria. In the present study, there was no increase in state 4 respiration as a function of age, which is consistent with findings in the blowfly [21] and rat [20,37,38], whereas in human liver state 4 respiration decreased [39] and in housefly it increased with age [6]. Nevertheless, changes in state 4 respiration must be interpreted with caution, because they may result from aging in vivo or from damage to mitochondria caused by harsh isolation procedures, such as excessive centrifugation, suboptimal buffers, or mechanical homogenization [34]. Such procedures can alter mitochondrial membrane properties, e.g. increasing the proton leak, leading to an increase in uncoupled electron transport and causing a spurious increase in the state 4 respiration rates of isolated mitochondria [6,34,37]. These methodological considerations are especially important in studies of insect aging, because the fusion of mitochondria into relatively large structures in older flies increases their fragility, making gentle pounding of the fly thoraces with a mortar and pestle preferable to homogenization [40].

State 3 respiration occurs in the presence of excess substrate and ADP, and is considered to be the active state of mitochondrial respiration. Results of this study demonstrate that the rate of state 3 respiration decreases as a function of age in D. melanogaster, if α-GP, pyruvate plus malate or pyruvate plus proline was used as the substrate. This age-related decrease in state 3 respiration is consistent with a number of earlier reports on insects and mammalian tissues [20–22,37,38,41], albeit some studies involving different species, tissues, substrates, and/or methodologies have reported that there are no age-related changes in state 3 respiration [19,20,22,41]. Although it is possible that age-related trends in state 3 respiration might differ among species, an alternative reason for these conflicting results could be that many of the studies did not include an internal standard, such as citrate synthase activity, to control for variations in mitochondrial protein concentration. In addition, the early insect studies reported extremely low respiratory control and ADP/O ratios, indicating that damage to the mitochondria might have occurred during isolation. In contrast, the relatively high RCRs (Figures 4C, 5C and 6C) and high ADP/O ratios obtained at all ages in the present study indicate that the quality of the mitochondrial preparations was good, and citrate synthase activity was used to control for variations in mitochondrial protein yield and purity.

There can be several potential causes for the observed decrease in state 3 respiration, including a decrease in substrate availability and an impairment of electron flow within the respiratory chain. The activities of aconitase, a key enzyme in the citric acid cycle, and ANT (adenine nucleotide translocator), which regulates the intramitochondrial ADP/ATP ratio, both decline by approx. 50% during aging in insects [42,43]. Inhibition of aconitase activity in vitro, using either fluoroacetate or fluorocitrate, has been found to decrease oxygen consumption in whole cells [44]. A decrease in aconitase activity would be predicted to inhibit glycolysis and the citric acid cycle, diminishing the production of NADH and FADH2 and thus the supply of reducing equivalents for electron transport. In contrast, a decline in ANT activity would be expected to decrease the supply of ADP to the F1Fo-ATPase and increase the membrane potential, impeding the flow of electrons and decreasing oxygen consumption. In either case, the ultimate consequence would be an age-related decrease in ATP production and, thus, in the supply of energy for the cell.

A decrease in cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) activity is an alternative mechanism whereby electron flow within the respiratory chain could be impaired. Indeed, a decline in complex IV activity is the most consistently reported age-related alteration in the electron transport systems of both insect and mammalian mitochondria [13–16,24]. However, the conclusion that there is any overt effect of aging on the electron transport system has been questioned recently [26], because many studies of mitochondrial respiration omitted crucial controls, such as the measurement of citrate synthase activity. By incorporating all of the controls recommended by Maklashina and Ackrell [26], the present study demonstrates not only that state 3 respiration but also complex IV activity declines with advancing age in Drosophila. This decrease in the activity of complex IV would be predicted to have a direct impact on rates of oxygen consumption and electron transport in vivo, as has been shown in vitro using specific inhibitors of complex IV (e.g. cyanide and azide) [23,25].

The impairment of complex IV activity would also be expected to increase the fraction of upstream electron carriers in a reduced state, thereby increasing the rate of univalent reduction of oxygen and subsequently the generation of O2•−/H2O2. Consistent with this prediction and with previous reports [23], the results of the present study demonstrate that titrating Drosophila mitochondria with KCN increases H2O2 production. These findings suggest that the decrease in complex IV activity observed during aging could at least partially explain the previously reported increase in H2O2 production in aged flies [6,7,10]. Although the precise sites of ROS production in the electron transport chain are still a matter of debate, and their identification is beyond the scope of this paper, a recent study in Drosophila has demonstrated that NADH dehydrogenase (complex I) and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase contribute significantly to the generation of mitochondrial ROS [45].

At least two different causal mechanisms may be proposed to explain this age-related decrease in complex IV activity. First, in addition to causing an increase in ROS production, the observed decline in complex IV activity could also be a direct consequence of increased ROS generation. Age-related increases in rates of mitochondrial O2•−/H2O2 generation have been documented for various insect and mammalian species [5–8,10] and both exogenous nitric oxide and H2O2 have been shown to diminish the activities of oxidoreductases in the electron transport chain, with complex IV being more sensitive than the other oxidoreductases [46,47].

A second possibility is that the decrease in complex IV activity could result from a loss in the abundance of subunits encoded by mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA). mtDNA is believed to be a prime target for oxidative damage due to its close proximity to the electron transport chain, and due to the absence of protective histone proteins and DNA repair enzymes in mitochondria [48,49]. Although there is no accumulation of mtDNA deletions in aging D. melanogaster [50], a decrease in mtDNA transcription has been reported, specifically affecting subunit I of cytochrome oxidase (coxI), corresponding to a decrease in complex IV activity [13,25,50]. This decreased transcription of coxI is most apparent in insects that have lost the ability to fly, and it can be induced experimentally by exogenous H2O2 [50]. Either oxidative damage, leading to a more rapid degradation of cytochrome c oxidase, or a decrease in coxI transcription could contribute to an age-associated decrease in cytochrome c oxidase protein levels. There are conflicting reports in the literature, with some groups reporting a decrease in coxI protein with increasing age [51], and others reporting an increase [52]; however, in the present study no change in coxI protein levels was detected. Therefore the decrease in complex IV activity was not the result of a decrease in coxI protein levels. The more likely explanation for the decrease in complex IV activity is oxidative inactivation, with no corresponding loss of protein abundance.

In conclusion, based on the present and previous studies, two age-related changes in mitochondrial function appear to occur most frequently, transcending phylogenetic boundaries: (i) a decrease in mitochondrial state 3 respiration and RCR; and (ii) a decrease in cytochrome c oxidase activity. The age-related decreases in state 3 respiration, RCR and uncoupled respiration observed in this study, without concomitant changes in state 4 respiration or ADP/O ratios, suggest that during aging there is damage to the electron transport chain in vivo, rather than a decrease in mitochondrial coupling caused by the isolation procedure, which results in a decline of electron transport with increasing age. The functional consequences of the decrease in state 3 respiration could include a decrease in ATP production, whereas decreased cytochrome c oxidase activity has been shown to be associated with increased H2O2 generation. The decrease in cytochrome c oxidase activity may also be responsible for the decreased state 3 respiration rate, causing a backlog of electrons and increased ROS generation by the upstream electron carriers. Collectively, these results suggest a possible link between losses of mitochondrial function and the decline in organismal stamina, which is a hallmark of aging.

Acknowledgments

B. H. Sohal provided valuable assistance in the preparation of fly mitochondria. This work was supported by grant RO1 AG7657 from the National Institute on Aging (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.).

References

- 1.Harman D. The biological clock: the mitochondria? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chance B., Sies H., Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol. Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwong L. K., Sohal R. S. Substrate and site specificity of hydrogen peroxide generation in mouse mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;350:118–126. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miquel J., Economos A. C., Fleming J., Johnson J. E., Jr Mitochondrial role in cell aging. Exp. Gerontol. 1980;15:575–591. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nohl H., Hegner D. Do mitochondria produce oxygen radicals in vivo? Eur. J. Biochem. 1978;82:563–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farmer K. J., Sohal R. S. Relationship between superoxide anion radical generation and aging in the housefly, Musca domestica. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1989;7:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohal R. S., Sohal B. H. Hydrogen peroxide release by mitochondria increases during aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1991;57:187–202. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90034-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sohal R. S., Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;273:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohal R. S., Dubey A. Mitochondrial oxidative damage, hydrogen peroxide release and aging. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1994;16:621–626. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sohal R. S., Agarwal A., Agarwal S., Orr W. C. Simultaneous overexpression of Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase and catalase retards age-related oxidative damage and increases metabolic potential in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:15671–15674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillered L., Ernster L. Respiratory activity of isolated rat brain mitochondria following in vitro exposure to oxygen radicals. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1983;3:207–214. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boffoli D., Scacco S. C., Vergari R., Solarino G., Santacroce G., Papa S. Decline with age of the respiratory chain activity in human skeletal muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1226:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreu A. L., Arbos M. A., Perez-Martos A., Lopez-Perez M. J., Asin J., Lopez N., Montoya J., Schwartz S. Reduced mitochondrial DNA transcription in senescent rat heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;252:577–581. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navarro A., Boveris A. Rat brain and liver mitochondria develop oxidative stress and lose enzymatic activities on aging. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004;287:R1244–R1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00226.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrandiz M. L., Martinez M., De Juan E., Diez A., Bustos G., Miquel J. Impairment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the brain of aged mice. Brain Res. 1994;644:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91699-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwong L. K., Sohal R. S. Age-related changes in activities of mitochondrial electron transport complexes in various tissues of the mouse. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;373:16–22. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torii K., Sugiyama S., Takagi K., Satake T., Ozawa T. Age-related decrease in respiratory muscle mitochondrial function in rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1992;6:88–92. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasmussen U. F., Krustrup P., Kjaer M., Rasmussen H. N. Experimental evidence against the mitochondrial theory of aging. A study of isolated human skeletal muscle mitochondria. Exp. Gerontol. 2003;38:877–886. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold P. H., Gee M. V., Strehler B. L. Effect of age on oxidative phosphorylation in the rat. J. Gerontol. 1968;23:509–512. doi: 10.1093/geronj/23.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiu Y. J., Richardson A. Effect of age on the function of mitochondria isolated from brain and heart tissue. Exp. Gerontol. 1980;15:511–517. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulos B., Shukla S., Sacktor B. Bioenergetic properties of mitochondria from flight muscle of aging blowflies. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1972;149:461–469. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(72)90345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wohlrab H. Age-related changes in the flight muscle mitochondria from the blowfly Sarcophaga bullata. J. Gerontol. 1976;31:257–263. doi: 10.1093/geronj/31.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohal R. S. Aging, cytochrome oxidase activity and hydrogen peroxide release by mitochondria. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1993;14:583–588. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90139-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morel F., Mazet F., Touraille S., Alziari S. Changes in the respiratory chain complexes activities and in the mitochondrial DNA content during ageing in D. subobscura. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1995;84:171–181. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01653-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarze S. R., Weindruch R., Aiken J. M. Oxidative stress and aging reduce COX I RNA and cytochrome oxidase activity in Drosophila. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1998;25:740–747. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maklashina E., Ackrell B. A. Is defective electron transport at the hub of aging? Aging Cell. 2004;3:21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2003.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rockstein M., Bhatnagar P. L. Frequency of wing beat in the aging housefly, Musca domestica L. Biofl. Bull. 1966;131:479–486. doi: 10.2307/1539987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams C. M., Barness L. A., Sawyer W. H. The utilization of glycogen by flies during flight and some aspects of the physiological aging of Drosophila. Biol. Bull. 1943;84:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wigglesworth V. B., Lee W. N. The supply of oxygen to flight muscles of insects: a theory of tracheole physiology. Tissue Cell. 1982;14:501–518. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(82)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trounce I. A., Kim Y. L., Jun A. S., Wallace D. C. Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Methods Enzymol. 1996;264:484–509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson J. B., Brent L. G., Sumegi B., Srere P. A. An enzymatic approach to the study of the Krebs tricarboxylic acid cycle. In: Darley-Usmar V. M., Rickwood D., Wilson M. T., editors. Mitochondria: A Practical Approach. Oxford: IRL Press; 1987. pp. 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollenbeck P. J., Bray D., Adams R. J. Effects of the uncoupling agents FCCP and CCCP on the saltatory movements of cytoplasmic organelles. Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 1985;9:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(85)90094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schagger H., von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Den Bergh S. G., Slater E. C. The respiratory activity and permeability of housefly sarcosomes. Biochem. J. 1962;82:362–371. doi: 10.1042/bj0820362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacktor B. Biological oxidations and energetics in insect mitochondria. In: Rockstein M., editor. The Physiology of Insecta. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 271–353. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sacktor B., Childress C. C. Metabolism of proline in insect flight muscle and its significance in stimulating the oxidation of pyruvate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1967;120:583–588. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horton A. A., Spencer J. A. Decline in respiratory control ratio of rat liver mitochondria in old age. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1981;17:253–259. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(81)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ventura B., Genova M. L., Bovina C., Formiggini G., Lenaz G. Control of oxidative phosphorylation by complex I in rat liver mitochondria: implications for aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1553:249–260. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yen T. C., Chen Y. S., King K. L., Yeh S. H., Wei Y. H. Liver mitochondrial respiratory functions decline with age. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989;165:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sohal R. S., McCarthy J. L., Allison V. F. The formation of ‘giant’ mitochondria in the fibrillar flight muscles of the housefly, Musca domestica. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1972;39:484–495. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(72)90115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinbach E. C., Garbus J. Oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria from aged rats. J. Biol. Chem. 1959;234:412–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan L. J., Sohal R. S. Mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocase is oxidatively modified during aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:12896–12901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Das N., Levine R. L., Sohal R. S. Selectivity of protein oxidative damage during aging in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem. J. 2001;360:209–216. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gardner P. R., Nguyen D. D., White C. W. Aconitase is a sensitive and critical target of oxygen poisoning in cultured mammalian cells and in rat lungs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:12248–12252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miwa S., St-Pierre J., Partridge L., Brand M. D. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production by Drosophila mitochondria. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2003;35:938–948. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benzi G., Curti D., Pastoris O., Marzatico F., Villa R. F., Dagani F. Sequential damage in mitochondrial complexes by peroxidative stress. Neurochem. Res. 1991;16:1295–1302. doi: 10.1007/BF00966660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiva S., Brookes P. S., Patel R. P., Anderson P. G., Darley-Usmar V. M. Nitric oxide partitioning into mitochondrial membranes and the control of respiration at cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:7212–7217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131128898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caron F., Jacq C., Rouviere-Yaniv J. Characterization of a histone-like protein extracted from yeast mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1979;76:4265–4269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clayton D. A. Replication of animal mitochondrial DNA. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 1982;28:693–705. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwarze S. R., Weindruch R., Aiken J. M. Decreased mitochondrial RNA levels without accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletions in aging Drosophila melanogaster. Mutat. Res. 1998;382:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5726(97)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hudson E. K., Tsuchiya N., Hansford R. G. Age-associated changes in mitochondrial mRNA expression and translation in the Wistar rat heart. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1998;103:179–193. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicoletti V. G., Tendi E. A., Lalicata C., Reale S., Costa A., Villa R. F., Ragusa N., Giuffrida Stella A. M. Changes of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase and FoF1 ATP synthase subunits in rat cerebral cortex during aging. Neurochem. Res. 1995;20:1465–1470. doi: 10.1007/BF00970595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Radyuk S. N., Klichko V. I., Orr W. C. Profiling Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase expression in Drosophila melanogaster – a critical regulatory role for intron/exon sequence within the coding domain. Gene. 2004;328:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]