Abstract

Biochemical studies have suggested that, in hyperthermophilic archaea, the metabolic conversion of glucose via the ED (Entner–Doudoroff) pathway generally proceeds via a non-phosphorylative variant. A key enzyme of the non-phosphorylating ED pathway of Sulfolobus solfataricus, KDG (2-keto-3-deoxygluconate) aldolase, has been cloned and characterized previously. In the present study, a comparative genomics analysis is described that reveals conserved ED gene clusters in both Thermoproteus tenax and S. solfataricus. The corresponding ED proteins from both archaea have been expressed in Escherichia coli and their specificity has been identified, revealing: (i) a novel type of gluconate dehydratase (gad gene), (ii) a bifunctional 2-keto-3-deoxy-(6-phospho)-gluconate aldolase (kdgA gene), (iii) a 2-keto-3-deoxygluconate kinase (kdgK gene) and, in S. solfataricus, (iv) a GAPN (non-phosphorylating glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; gapN gene). Extensive in vivo and in vitro enzymatic analyses indicate the operation of both the semi-phosphorylative and the non-phosphorylative ED pathway in T. tenax and S. solfataricus. The existence of this branched ED pathway is yet another example of the versatility and flexibility of the central carbohydrate metabolic pathways in the archaeal domain.

Keywords: carbohydrate metabolism, Entner–Doudoroff pathway, gluconate dehydratase, hyperthermophilic archaea, 2-keto-3-deoxygluconate (KDG), phosphorylation

Abbreviations: ED pathway, Entner–Doudoroff pathway; EMP, Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway; GA, glyceraldehyde; GAD, gluconate dehydratase; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; GAPN, non-phosphorylating GAP dehydrogenase; GDH, glucose dehydrogenase; KDG, 2-keto-3-deoxygluconate; KDGal, 2-keto-3-deoxygalactonate; KDPG, 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate; MLE, muconate-lactonizing enzyme; MR, mandelate racemase; NAL, N-acetylneuraminate lyase; TBA, thiobarbituric acid

INTRODUCTION

Comparative studies of the glycolysis in thermophilic and hyperthermophilic archaea have revealed a large number of modifications in the classical bacterial and eukaryal routes: the ED (Entner–Doudoroff) pathway and the EMP (Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas) pathway [1–4]. Whereas the ED-like pathway seems to be restricted to the aerobic archaea (e.g. Sulfolobus solfataricus [5] and Thermoplasma acidophilum [6]), the archaeal modified EMP pathways are found in most anaerobic archaea (e.g. Pyrococcus furiosus, Thermococcus sp., Desulfurococcus amylolyticus and Archaeoglobus fulgidus) [2–4]. The presence of both modified pathways has so far been demonstrated only in the anaerobe Thermoproteus tenax [4,7–10].

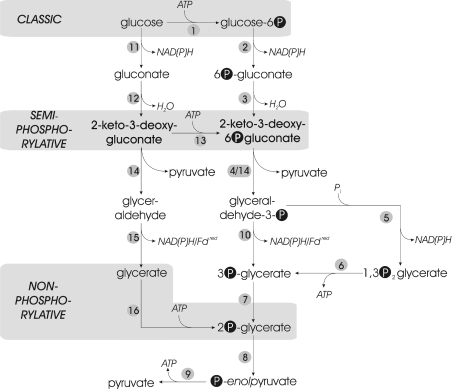

The classical ED pathway [11] involves (i) the initial phosphorylation of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate either by a glucokinase or by the action of a phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system, (ii) the oxidation to 6-phosphogluconate by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and phosphogluconolactonase, (iii) the dehydration to KDPG (2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate) by 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase, and (iv) the cleavage of the characteristic KDPG intermediate by KDPG aldolase, yielding GAP (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate) and pyruvate. GAP is further metabolized via the lower, common shunt of the EMP pathway, yielding a second molecule of pyruvate (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Glucose catabolism via the different ED pathways.

Overview of the classical and modifications of the ED pathway, each with the characteristic phosphorylation level indicated. Non-phosphorylated intermediates are depicted on the left, and phosphorylated intermediates on the right. The key phosphorylation reactions for the different ED versions are highlighted in grey boxes (glucokinase/hexokinase for the classical ED, KDG kinase for the semi-phosphorylative ED and glycerate kinase for the non-phosphorylative ED). Key to enzymes: 1, glucokinase/hexokinase; 2, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; 3, 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase; 4, KDPG aldolase; 5, GAPDH; 6, 3-phosphoglycerate kinase; 7, phosphoglycerate mutase; 8, enolase; 9, pyruvate kinase; 10, GAPN/GAP oxidoreductase; 11, GDH; 12, GAD; 13, KDG kinase; 14, KD(P)G aldolase; 15, aldehyde dehydrogenase/aldehyde oxidoreductase; and 16, glycerate kinase.

Whereas the classical pathway seems to be restricted to bacteria, modifications have been identified in all three domains of life: the Eukarya, Bacteria and Archaea [12]. One of the modified versions of the ED pathway that is generally referred to as the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway [13], concerns (i) the oxidation of glucose to gluconate via GDH (glucose dehydrogenase), (ii) the conversion of gluconate by a specific GAD (gluconate dehydratase) into KDG (2-keto-3-deoxygluconate), (iii) the subsequent phosphorylation by KDG kinase to form KDPG, and (iv) the cleavage by KDPG aldolase (Figure 1). The semi-phosphorylative ED pathway has been shown to operate in several species of Clostridium [14], as well as the halophilic archaea Halobacterium saccharovorum and Halobacterium halobium [15].

Another variant pathway, the so-called non-phosphorylative ED pathway, has been reported for the hyperthermophilic archaea S. solfataricus [5], S. acidocaldaricus [10], T. tenax [4,7–10], the thermophilic archaeon T. acidophilum [6] and several species of the fungal genus Aspergillus [16]. In contrast with the semi-phosphorylative ED modification, KDG (rather than KDPG) has been reported to be subjected to aldol cleavage by the KDG aldolase, forming pyruvate and GA (glyceraldehyde). GA is further oxidized to form glycerate, either by an NAD(P)+-dependent glyceraldehyde dehydrogenase [6] or by a ferredoxin-dependent GA oxidoreductase [8,17–19]; glycerate is phosphorylated to 2-phosphoglycerate by glycerate kinase [6]. 2-Phosphoglycerate enters the lower shunt of the EMP pathway and forms a second molecule of pyruvate via the enolase and pyruvate kinase reaction (Figure 1).

In the present study, the ED pathways of two hyperthermophilic crenarchaea have been re-evaluated: (i) S. solfataricus and (ii) T. tenax.

S. solfataricus grows optimally at 80–85 °C and pH 2–4. Aerobic heterotrophic growth is reported on several carbon sources such as starch, glucose, arabinose, fructose and peptide-containing substrates like peptone, tryptone and yeast extract [20]. The non-phosphorylative ED pathway was proposed as the pathway for glucose catabolism on the basis of 14C-labelling studies and identification of the characteristic intermediates (KDG and GA) [5], as well as characterization of key enzyme activities [5,21,22]. The GDH and KDG aldolase of S. solfataricus have been studied in detail, and more recent studies [22] indicate that this pathway is promiscuous and represents an equivalent route for glucose and galactose catabolism in this organism. In addition to a GDH that exhibits high activity with glucose and galactose, the KDG aldolase was shown to lack facial selectivity in catalysing the cleavage of KDG as well as KDGal (2-keto-3-deoxygalactonate), both yielding GA and pyruvate. At the time the present study was submitted, the archaeal GAD had not yet been identified (however, see the Discussion section).

T. tenax is a sulphur-dependent anaerobe that grows optimally at approx. 90 °C, pH 5 [23], and was shown to grow both chemolithoautotrophically (CO2 and H2) and chemo-organoheterotrophically on different carbon sources (e.g. glucose and starch). T. tenax uses two different pathways for glucose catabolism, the modified EMP and the non-phosphorylative ED pathway, as deduced from detected enzyme activities in crude extracts, and from the identification of characteristic intermediates in 14C-labelling experiments and in vivo 13C NMR studies [4,7–10,24]. However, the reconstruction of the central carbohydrate metabolism by the use of genomic and biochemical data revealed the presence of the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway in T. tenax [4].

In the current view about the ED pathway in archaea, it is assumed that a semi-phosphorylative version is operative in haloarchaea, whereas a non-phosphorylative version is present in hyperthermophilic and thermophilic archaea. The aforementioned biochemical data on S. solfataricus and T. tenax do not disagree with this assumption. However, in our ongoing attempts to reconstruct the archaeal central carbohydrate-metabolizing pathways, a comparative genomics approach has revealed ED gene clusters that are conserved in T. tenax [4], S. solfataricus, S. tokodaii and Halobacterium sp. NRC. We present here a qualitative analysis of the corresponding gene products of T. tenax and S. solfataricus. A detailed biochemical analysis of the individual enzymes is ongoing (H. Ahmed, T. J. G. Ettema, J. van der Oost and B. Siebers, unpublished work). The present study reports new insights into the operation of the modified ED pathways in hyperthermophilic archaea.

EXPERIMENTAL

Strains and growth conditions

Cultures of T. tenax (DSM 2078, [23]) and S. solfataricus P2 (DSM 1617, [25]) were grown as reported previously [26,27]. For S. solfataricus, carbon sources were added to a final concentration of 0.2% (w/v). Escherichia coli strains DH5α (Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands), BL21 (DE3), BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus (Novagen, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) and JM109 (DE3) (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) for cloning, and expression studies were grown under standard conditions [28] following the manufacturer's instructions.

Chemicals and plasmid

All chemicals and enzymes were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, VWR (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) or Roche Diagnostics in analytical grade. 14C-labelled glucose and pyruvate were obtained from Amersham Biosciences. For heterologous expression, the pET vector system (pET-15b, pET-24a and pET-24d; Novagen) was used.

Heterologous expression

For expression of the gdh (GDH; EMBL accession no. AJ621346), gad (GAD; EMBL accession no. AJ621281), kdgA [KD(P)G aldolase; EMBL accession no. AJ621282] and kdgK (KDG kinase; EMBL accession no. AJ621283) from T. tenax and the gad (SSO3198), kdgA (SSO3197), kdgK (SSO3195) and gapN [non-phosphorylating GAPDH (GAP dehydrogenase); SSO3194] from S. solfataricus, the genes were cloned into the pET vector system (Novagen) using the restriction sites introduced by PCR mutagenesis (Table 1). PCR mutagenesis was performed using Pwo or Taq polymerase (Peqlab; Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) and genomic DNA from T. tenax or S. solfataricus as the template. The sequence of the cloned genes was verified by dideoxy sequencing and expression of the recombinant enzymes in E. coli BL21 (DE3), BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus and JM109 (DE3) was performed following the manufacturer's instructions (Novagen and Promega respectively).

Table 1. Primer sets, strains and hosts used in the present study.

The introduced mutations are shown in boldface and the restriction sites are underlined. f, forward primer; rev, reverse primer; Sso, S. solfataricus; Tm, T. maritima; Ttx, T. tenax.

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Plasmid | Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ttx gdh | GDH-BspHI-f | TAGAGGCTCATGAGGGCTG | pET-15b | BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus |

| GDH-BamHI-rev | ACTACCGTGGATCCACAAC | |||

| Ttx gad | GAD-NcoI-f1 | TTTGGCCAGCGCCATGGCCTCATCG | pET-15b | BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus |

| GAD-XhoI-rev | AAATGCCGGCCTCGAGGGAATGGGA | |||

| Ttx kdgA | KDGA-NcoI-f | AGGGCGCCCCGAGTACTATCCATGGAGA | pET-15b | BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus |

| KDGA-XhoI-rev | GGGGCTCCCCTCGAGCTACCAGGC | |||

| Ttx kdgK | KDGK-NdeI-f | GAGCCAGCTGAGCATATGATAAGCCTGG | pET-24a | BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus |

| KDGK-EcoRI-rev3 | TTGCCCAGAATTCCGCTCCTC | |||

| Sso gad | BG1069 (NcoI-f) | GCGCGCCATGGCGAGAATCAGAGAAATAGAACCAATAG | pET-24d | BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus |

| BG1070 (BamHI-rev) | GCGCGGGATCCTCAAACACCATAATTCTTCCAGGTTCCC | |||

| Sso kdgA | BG1067 (NcoI-f) | GCGCGCCATGGCGCCAGAAATCATAACTCCAATCATAACC | pET-24d | BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus |

| BG1068 (BamHI-rev) | GCGCGGGATCCCTATTCTTTCAATATTTTAAGCTCTAC | |||

| Sso kdgK | BG1071 (NcoI-f) | GCGCGCCATGGTTGATGTAATAGCTTTGGGAGAGCC | pET-24d | JM109 (DE3) |

| BG1072 (NcoI-mut-f)* | CTGGGGCTGGTGACGCAATGGCAGGGACATTTGTTTCC | |||

| BG1073 (NcoI-mut-rev)* | GGAAACAAATGTCCCTGCCATTGCGTCACCAGCCCCAG | |||

| BG1074 (EcoRI-rev) | GCGCGGAATTCTTACGTTTTAAACTCATTTAAAAATC | |||

| Sso gapN | BG1451 (NcoI-f) | GCGCGCCATGGAGAAAACATCAGTGTTG | pET-24d | JM109 (DE3) |

| BG1452 (BamHI-rev) | GCGCGGGATCCTTACAAGTATTCCCAAATACCTTTCCC | |||

| Tm eda† | pET-28b | BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus | ||

| Ttx gapN‡ | pET-15b | BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus |

Protein purification

Recombinant E. coli cells (1 g wet weight) were suspended in 2 ml of 100 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C) containing 7.5 mM dithiothreitol (buffer A) and passed three times through a French pressure cell at 150 MPa. Cell debris and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation (60000 g for 30 min at 4 °C). For enrichment, the resulting crude extracts were diluted 1:1 with buffer A and subjected to a heat precipitation for 30 min at different temperatures. Extracts containing recombinant T. tenax and S. solfataricus protein were incubated at the following temperatures: T. tenax and S. solfataricus KD(P)G aldolase and T. tenax GAD at 85 °C (30 min), T. tenax GDH and KDG kinase at 80 °C (30 min). Extracts containing recombinant S. solfataricus GAPN were incubated at 70 °C (20 min) and S. solfataricus GAD and KDG kinase at 65 °C (20 min). After heat precipitation, the samples were cleared by centrifugation (60000 g for 30 min at 4 °C). GAPN, GAD and KDG kinase of S. solfataricus were dialysed overnight against 50 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C), 7.5 mM dithiothreitol (2 litres, 4 °C) and directly used for enzymatic assays. GAD, KD(P)G aldolase and KDG kinase of T. tenax and KD(P)G aldolase of S. solfataricus were dialysed overnight [50 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C), 7.5 mM dithiothreitol, 300 mM KCl and alternatively for GAD 200 mM KCl] and subjected to gel filtration on HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 prep grade (Amersham Biosciences) preequilibrated in the respective buffer. Fractions containing the homogeneous enzyme fraction were pooled and used for enzymatic assays. The kinetic parameters (Vmax and Km) were calculated by iterative curve-fitting (Hanes) using the program Origin (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA, U.S.A.).

Enzyme assays

KD(P)G aldolase and GAD activity were measured at 70 °C using the TBA (thiobarbituric acid) assay as described previously [21] but with the following modifications. The KD(P)G aldolase assay was performed in 100 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C), 5 mM pyruvate and 2 mM D,L-GA or D,L-GAP were added as substrates for the enzyme (6 or 12 μg of T. tenax and S. solfataricus protein after gel filtration respectively; total volume, 1 ml). The experiments were performed in the presence of 2 mM GA or GAP and 5 mM pyruvate, since at higher concentrations of GAP (20 mM GAP and 50 mM pyruvate) the observed activity is no more proportional to the amount of enzyme.

GAD activity (30 and 60 μg of T. tenax protein after gel filtration; 840 μg of S. solfataricus protein after heat precipitation; total volume, 1 ml) was assayed in the presence of 10 mM gluconate and galactonate. The absorbance was followed at 549 nm (molar absorption coefficient ϵchromophore=67.8×103 M−1·cm−1) [29,30]. Galactonate (10 mM) was prepared from galactonate γ-lactone by incubation in 1 M NaOH for 1 h (4 M stock solution) and subsequent dilution in 50 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C) as described in [31].

The activity of the T. tenax and S. solfataricus KDG kinases was determined at 70 and 60 °C respectively using a continuous assay. The phosphorylation of KDG by ATP was monitored by coupling the formation of KDPG with the reduction of NAD+ via KD(P)G aldolase and GAPN of T. tenax [32]. The standard assay was performed in 100 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C) in the presence of KDG kinase (1.5 and 3 μg of T. tenax protein after gel filtration; 40 and 80 μg of S. solfataricus protein after heat precipitation), 2 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NAD+, KD(P)G aldolase (3 μg of T. tenax enzyme after gel filtration) and GAPN (25 μg of T. tenax enzyme, protein fraction after heat precipitation). It was ensured that the amount of auxiliary enzymes is not rate-limiting. The reaction was started by addition of KDG kinase. Enzymatic activities were measured by monitoring the increase in absorption at 340 nm (ϵNADH, 70°C=5.8 mM−1·cm−1).

KDG was synthesized via the KD(P)G aldolase from T. tenax as described previously [22]. Briefly, 1 g of D,L-GA and 2.2 g of pyruvate were mixed in 100 ml of water containing 6.6 mg of enzyme and the reaction mixture was incubated for 8 h at 70 °C. Protein was removed by acetone precipitation and the reaction mix was separated by Dowex 1×8 anion-exchange chromatography using a linear 0.0–0.2 M HCl gradient. Fractions containing KDG without GA and pyruvate were identified using the TBA assay, the lactate dehydrogenase assay and TLC. Alternatively, KDG was formed by coupling the reaction with the dehydration of gluconate using GAD from T. tenax.

GAPN activity was determined in a continuous assay at 70 °C. The standard assay was performed in the presence of 90 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C), 160 mM KCl, 3 mM D,L-GAP and 2 mM NADP+ [32,33]. The reaction was started by the addition of GAP and the enzyme concentration was 70 μg of protein/ml assay volume (ϵNADH, 70°C=5.8 mM−1·cm−1; ϵNADPH, 70°C=5.71 mM−1·cm−1).

In vitro assays with crude extracts

Crude extracts of T. tenax and S. solfataricus cells grown on glucose were prepared as reported for the recombinant E. coli cells. After centrifugation, the protein solution was dialysed overnight against 50 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C), 7.5 mM dithiothreitol (2 litres, 4 °C) and directly used for enzymatic assays. Activities in crude extracts (450 or 900 μg of protein; total volume, 1 ml) were determined as described for the recombinant proteins.

14C-labelling experiments and TLC

KD(P)G aldolase activity from T. tenax and S. solfataricus was monitored by incubation of dialysed fractions after heat precipitation (16 μg of T. tenax and 11 μg of S. solfataricus protein) in 100 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C) in the presence of 0.3 μCi of [2-14C]pyruvate, 50 mM pyruvate and 20 mM of either GA or GAP (total volume, 30 μl). A sample was withdrawn before and after incubation at 70 °C (30 min) and analysed by TLC [silica gel G-60 plates without fluorescence indicator (VWR) developed in butan-1-ol/acetic acid/water (3:1:1, by vol.)] and autoradiography (Agfa X-ray 90 films). Intermediates were identified by their Rf values determined previously [7] and by the formation of KDG and KDPG using the characterized KDPG aldolase (EDA) of Thermotoga maritima [34]. The expression plasmid of T. maritima KDPG aldolase (pTM-eda) was kindly provided by C.A. Fierke (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.). The enzyme of T. maritima was enriched by heat precipitation (30 min, 75 °C) from the expression host [BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus].

For the in vitro reconstruction of the ED pathway, the labelled intermediates were monitored after the addition of the different ED enzymes [GDH (13 μg of T. tenax protein), GAD (11 μg of T. tenax protein), KD(P)G aldolase (23 μg of T. tenax protein), KDG kinase (35 μg of T. tenax protein)]. The assay was performed in the presence of 0.3 μCi of [U-14C]glucose, 100 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.0, 70 °C), 10 mM glucose and 5 mM NADP+. ATP (10 mM) and Mg2+ (10 mM) were added in the presence of KDG kinase. Samples (30 μl volume) were incubated for 10, 30 and 60 min at 70 °C and the labelling was monitored by TLC as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

On the basis of biochemical studies using crude extracts as well as characterization of key enzymes, it has been proposed that hyperthermophilic archaea utilize the non-phosphorylative ED pathway for glucose degradation [4–10]. However, using a comparative genomics approach, we detected a conserved ED cluster in the genomes of T. tenax [4], S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii that resembles the cluster present in Halobacterium sp. NRC1 (Figure 2).

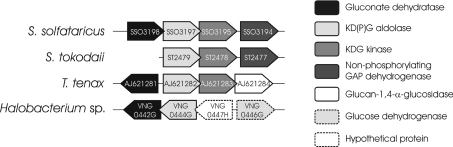

Figure 2. ED gene clusters in archaea identified by conserved genome context analysis.

Schematic representation of the conserved gene clusters in archaeal genomes, comprising key genes of the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway. The genes are indicated by their systematic gene name; except for T. tenax, the accession numbers are displayed and orthologous genes are shaded in the same grey scale. Genes are not drawn to scale.

The ED gene cluster

The ED gene clusters of the hyperthermophilic crenarchaea T. tenax [4] and S. solfataricus comprise genes encoding KD(P)G aldolase (COG0329), a putative KDG kinase (COG0524) and a putative GAD (gad gene, COG4948). In addition, a gene encoding a GAA (glucan-1,4-α-glucosidase; gaa gene, COG3387) was identified in the T. tenax ED cluster and a gene coding for a GAPN (gapN gene, COG1012) was found in the S. solfataricus ED gene cluster (Figure 2). The S. tokodaii gene cluster resembles that of S. solfataricus; however, in this organism, the gad gene is not part of the gene cluster. Homologues of the gad and kdgA genes (both share 29% identity with the T. tenax enzymes) are also present in the ED cluster of Halobacterium sp. NRC1 (gcd, orf-kdgA-gad), which additionally comprises genes that encode GDH (gcd, COG1063) and a hypothetical protein (Figure 2).

Whereas the S. solfataricus KDG aldolase was cloned and characterized previously [21,22], no functional information was available on the other genes present in the gene cluster when the present study was initiated [2–4]. The genes encoding the putative dehydratases (COG4948) that reside in the T. tenax and S. solfataricus ED clusters exhibit high similarity to members of the diverse MR (mandelate racemase)/MLE (muconate-lactonizing enzyme) subgroup of the enolase superfamily, which includes some sugar dehydratases [35]. The conserved clustering of these genes within the ED clusters of T. tenax and S. solfataricus suggests that their gene products are likely candidates for the missing GAD (gad gene) activity (Figure 2) [2–4]. Despite the fact that GAD activity has been measured in different bacterial, archaeal and eukaryal (fungal) sources [30,36–38], the gene has not been identified for a long time. As such, it represented a missing link in central carbohydrate metabolism, and only recently GAD activity was reported for the recombinant T. tenax [4] and the purified native S. solfataricus enzymes [31,39]. The enzyme shows no homology with the classical phosphogluconate dehydratase (ED dehydratase, edd; EC 4.2.1.12, COG0129).

The conserved clustering of genes encoding putative KDG kinases in addition to gapN (in S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii) was rather surprising, since the modified ED pathway has been reported to proceed via non-phosphorylated intermediates at the C-6 position. This conserved gene clustering did suggest the operation of the semi-phosphorylative pathway in these organisms. Moreover, the high similarity of the thermophilic proteins to the haloarchaeal KDG kinase and KDPG aldolase suggests a similar substrate specificity, again indicating the presence of the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway in T. tenax and S. solfataricus.

Enzyme characterization

The gdh, gad, kdgA and kdgK genes of T. tenax and the gad, kdgA, kdgK and gapN genes of S. solfataricus were cloned and expressed in E. coli using the pET expression system. The recombinant enzymes were enriched from crude extracts by heat precipitation (GDH of T. tenax; GAD, KDG kinase and GAPN of S. solfataricus) and key enzymes were further purified by gel filtration [GAD, KD(P)G aldolase, KDG kinase of T. tenax; KD(P)G aldolase of S. solfataricus]. Due to the heat precipitation at 65–90 °C (30 min) and the high assay temperature at 70 °C, the activity of residual, contaminant E. coli proteins is highly unlikely and was further diminished by analysis of a heat-precipitated extract of the expression host with plasmid without insert.

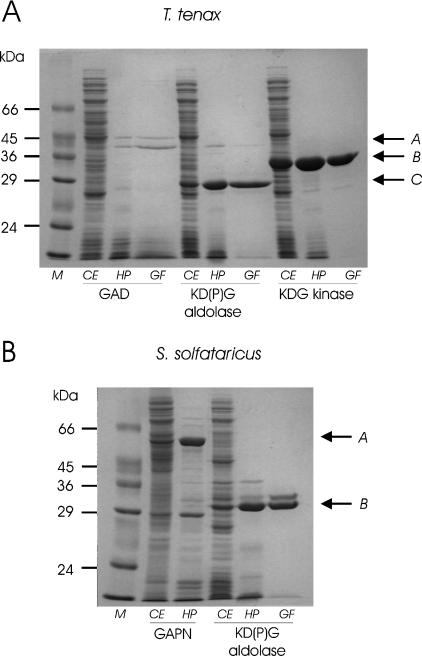

For all enzymes, with the exception of the S. solfataricus GAD and KDG kinase, a good expression and sufficient enrichment was observed (Figure 3). For the T. tenax GAD, two bands were enriched after gel filtration (Figure 3A); however, both proteins exhibited different elution profiles after gel filtration without salt and the upper band was clearly associated with catalytic GAD activity. Whereas, as observed from SDS/PAGE, the molecular mass approximately corresponds to the calculated mass for T. tenax GAD (43/44.033 kDa) and T. tenax KDG kinase (32/33.308 kDa), some deviation is observed for both KD(P)G aldolases [T. tenax (26/30.982 kDa), S. solfataricus (30/33.108)] and S. solfataricus GAPN (54/56.927) (apparent/calculated molecular masses are given in parentheses). However, these differences of 3–5 kDa are in agreement with generally observed minor deviations.

Figure 3. Recombinant production and purification of T. tenax and S. solfataricus ED proteins.

(A) SDS/PAGE of recombinant expression and purification of T. tenax GAD, KD(P)G aldolase and KDG kinase. Arrows indicate the purified recombinant GAD (A), KD(P)G aldolase (C) and KDG kinase (B). (B) SDS/PAGE of recombinant expression and purification of S. solfataricus KD(P)G aldolase and GAPN. Arrows indicate the purified recombinant GAPN (A) and KD(P)G aldolase (B). Lanes containing crude cell extracts (CE), soluble fractions after heat precipitation (HP) and gel filtration (GF) were loaded with 20, 10 and 5 μg of protein respectively. Lane M corresponds to the protein marker, Dalton Mark VII-L (Sigma).

Expression of S. solfataricus GAD and KDG kinases was rather poor, as only little recombinant protein was observed in the soluble fraction. In addition, unlike the native enzyme [31,39], the recombinant S. solfataricus GAD appeared to be relatively instable, not allowing the heat precipitation step to be performed above 65 °C. Attempts to improve the poor recombinant expression by the use of different expression hosts [BL21 (DE3), BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus, JM109 (DE3) and ROSETTA] and different suspension buffers were not successful.

GDH

The T. tenax GDH catalyses the oxidation of glucose yielding gluconate. The gene was unequivocally identified by the previously determined N-terminal sequence of the GDH isolated and characterized from T. tenax cells and confirmed by the activity of the recombinant protein (results not shown) [9]. The enzyme was used for the in vitro reconstruction of the pathway.

GAD

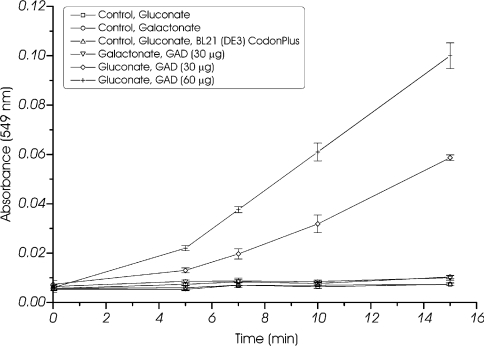

GAD catalyses the dehydration of gluconate yielding KDG. The T. tenax GAD was assayed by monitoring KDG formation using the discontinuous TBA assay (70 °C). The enriched T. tenax enzyme after heat precipitation (0.272±0.007 unit/mg of protein) exhibits high sensitivity towards salts (KCl). After ion chromatography (Q-Sepharose; Amersham Biosciences), all activity was lost, and the activity was reduced after gel filtration in the presence of 200 mM KCl. As shown in Figure 4, the time-dependent formation of KDG from gluconate was only observed in the presence of enzyme (fraction after gel filtration) and substrate (T. tenax: 0.065±0.006 unit/mg of protein at 10 mM gluconate), thus confirming the proposed GAD activity.

Figure 4. GAD activity of T. tenax.

GAD activity (protein fraction after gel filtration) was monitored at 70 °C using the discontinuous TBA assay. Activity on gluconate (10 mM; 30 and 60 μg of protein) as well as galactonate (10 mM; 30 μg of protein) and controls without enzyme (10 mM gluconate and galactonate) or substrate (results not shown) and heat-precipitated extract of BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus with pET-15b without insert are shown. All experiments were performed in triplicate and the S.D. is given. GAD activity was only observed in the presence of gluconate and the observed activity is proportional to the amount of enzyme.

The specific activity is proportional to the amount of recombinant protein (2.1±0.1 m-units/30 μg; 3.7±0.1 m-units/60 μg). No activity could be detected with negative controls without protein (gluconate and galactonate), without substrate (results not shown), as well as with a heat-precipitated cell-free extract of BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus with the plasmid pET-15b without insert. Considering the reports of pathway promiscuity in S. solfataricus [22], the activity of the T. tenax enzyme was analysed in the protein fraction after heat precipitation or gel filtration; however, no GAD activity with galactonate as substrate was observed. In agreement with this finding, GAD activity on only gluconate (not galactonate) was observed in crude extracts of T. tenax, whereas activity with both substrates was observed in S. solfataricus crude extracts (Table 3).

Table 3. Specific activities of ED enzymes in crude extracts of T. tenax and S. solfataricus.

Errors are given from three independent measurements. n.d., not detected.

| Specific activity (m-units/mg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme activity | Substrate concentration (mM) | T. tenax | S. solfataricus |

| GAD | 10 mM gluconate | 10.9±0.7 | 15.2±0.9 |

| 10 mM galactonate | n.d. | 5.7±0.6 | |

| KD(P)G aldolase | 2 mM GA, 5 mM pyruvate | 1.4±0.1 | 1.5±0.4 |

| 2 mM GAP, 5 mM pyruvate | 1.7±0.3 | 13.4±0.8 | |

| KDG kinase | 10 mM KDG, 2 mM ATP | 9.1±0.5 | 8.7±0.3 |

| GAPN | 3 mM GAP, 2 mM NADP+ | 1.13±0.04* | 32.3±0.5 |

| 3 mM GAP, 1 mM NAD+ | 3.5±0.1 | n.d.* | |

* Assay was performed in the presence of 20 mM NADP+/NAD+.

The high thermal instability of the recombinant S. solfataricus GAD did not allow further characterization of the enzyme. After submission of this paper for publication, the purification and characterization of GAD from S. solfataricus was reported by two independent groups [31,39]. Surprisingly, these studies report some contradicting results about molecular mass and catalytic activity with galactonate; our analysis supports the proposed substrate promiscuity in S. solfataricus [22].

The GADs of T. tenax and S. solfataricus are members of the MR subgroup of the enolase superfamily and thus represent the first reported GAD in this superfamily [35]. The enolase superfamily harbours a diverse set of enzymes, which at first sight catalyses markedly different overall reactions (e.g. enolase, MR, galactonate dehydratase, MLE I, β-methylaspartate ammonia lyase and o-succinylbenzoate synthase). A common feature of all family members is the first step of their catalytic action, i.e. the abstraction of the α-proton of a carboxylic acid to form an enolic intermediate. The enolase superfamily is divided into the MR, MLE I and enolase subgroups. In the MR subgroup, so far only glucarate dehydratase from Pseudomonas putida, Bacillus subtilis and E. coli as well as galactonate dehydratase from E. coli has been biochemically characterized [35,40]. Homologues of the S. solfataricus and T. tenax GAD have been identified in many archaeal, bacterial and eukaryal species. However, functional annotation of these proteins remains difficult due to the broad substrate specificity within the enolase superfamily.

KDG aldolase

KDG aldolase catalyses the reversible cleavage of KDG yielding pyruvate and GA. The T. tenax and S. solfataricus KDG aldolase activity was assayed in the anabolic direction of KDG formation from C-3 substrates (condensation reaction) using the discontinuous TBA assay. In contrast with previous reports on the S. solfataricus KDG aldolase [21], activity was observed not only with GA but also with the phosphorylated substrate GAP. The time-dependent formation of KDG and KDPG was monitored in the presence of the T. tenax or S. solfataricus enzyme and GA and GAP respectively, as substrates (Figure 5). The observed activity is proportional to the amount of recombinant protein, as shown for GA (T. tenax: 12.6±0.5 m-units/6 μg and 24.6±1.3 m-units/12 μg; S. solfataricus: 13.1±1.5 m-units/6 μg and 23.3±1.5 m-units/12 μg) and GAP (T. tenax: 66.9±2.7 m-units/6 μg and 141.3±6.4 m-units/12 μg; S. solfataricus: 31.8±5.1 m-units/6 μg and 66.7±4.3 m-units/12 μg). The negative controls without protein, only one substrate and the cell-free extract of expression host with empty vector (results not shown) revealed no activity.

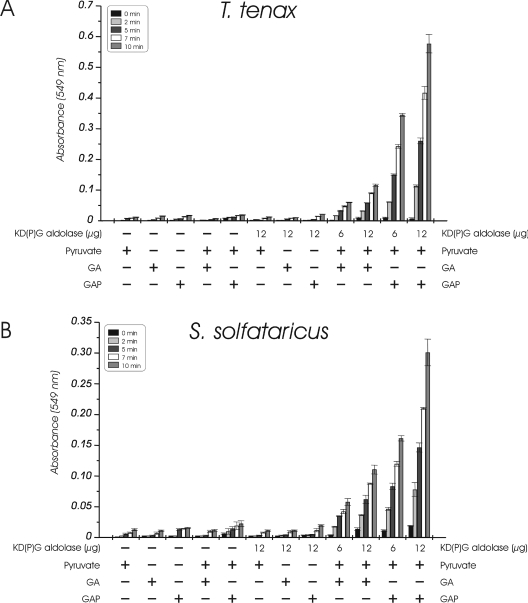

Figure 5. KD(P)G aldolase activity of T. tenax (A) and S. solfataricus (B).

The formation of KDG and KDPG from pyruvate (5 mM) and GA or GAP (2 mM) respectively was monitored at 70 °C using the discontinuous TBA assay. The dependence on the amount of protein (6 and 12 μg of protein, fraction after gel filtration) and controls with one (GA, GAP or pyruvate) or both (pyruvate and GA or GAP respectively) substrates without enzyme and with one substrate (GA, GAP or pyruvate respectively) in the presence of enzyme are shown. For each probe, three independent measurements were performed and the experimental error is given. In the presence of KD(P)G aldolase, the formation of KDG from GA and pyruvate as well as KDPG from GAP and pyruvate was observed. The activity with non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated substrates is proportional to the amount of enzyme used in the assay.

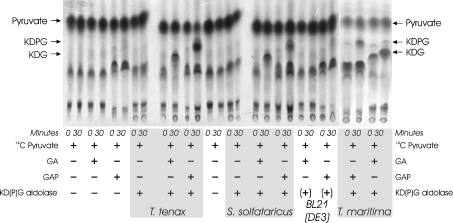

In order to confirm these results, both enzymes were assayed in the presence of 14C-labelled pyruvate, the products were separated by TLC and afterwards monitored by autoradiography (Figure 6). In agreement with the aforementioned enzyme assays, the formation of both labelled products was observed: KDG from GA and pyruvate or KDPG from GAP and pyruvate. No product formation was observed in the controls without protein, with protein and only one substrate (GA, GAP or pyruvate respectively) and with cell-free extract of the host BL21 (DE3) with plasmid pET-15b without insert after heat precipitation. As an additional control, the characterized KDPG aldolase (EDA) of the anaerobic, hyperthermophilic bacterium T. maritima, which was reported for activity on phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated substrates [34] was used. In accordance with the T. tenax and S. solfataricus KD(P)G aldolase, KDG and KDPG formation was observed (Figure 6). The different spots of pyruvate are probably caused by the instability of an aqueous solution of pyruvic acid and sodium salt due to intra- and intermolecular aldol-type condensations as indicated by the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences). The observed change in the pattern of the labelled pyruvate (second spot) is obviously due to the presence of GAP alone, as shown by the controls without KD(P)G aldolase and BL21 (DE3) extract.

Figure 6. Detection of 14C-labelled KDG and KDPG through TLC and autoradiography.

The KD(P)G aldolases of T. tenax and S. solfataricus (fraction after heat precipitation) were incubated at 70 °C in the presence of labelled pyruvate ([2-14C]pyruvate) and either GA or GAP. Control samples containing different combinations of KD(P)G aldolase and substrates are shown as indicated. In addition, control samples of the expression host BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus with pET-15b without insert after heat precipitation, indicated by ‘+’, and formation of 14C-labelled KDG and KDPG by the KDPG aldolase (EDA) of T. maritima (fraction after heat precipitation) [34] are shown. The formation of 14C-labelled KDG and KDPG was monitored via TLC and visualized using autoradiography. As for the KDPG aldolase of T. maritima, the formation of both KDG (from GA and pyruvate) and KDPG (from GAP and pyruvate) is observed in the presence of the KD(P)G aldolase of T. tenax or S. solfataricus.

Thus, in contrast with former reports, both the T. tenax and S. solfataricus enzymes are 2-keto-3-deoxy-(6-phospho)-gluconate [KD(P)G] aldolases of low substrate specificity that are active on phosphorylated (GAP and KDPG) as well as non-phosphorylated (GA and KDG) substrates. The recombinant S. solfataricus aldolase was re-investigated by the group of M. Danson (University of Bath, Bath, U.K.) and the activity on phosphorylated substrates was indeed confirmed (M. Danson, personal communication). This bifunctional KD(P)G aldolase appears to be a key enzyme in both the non- and the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway, which would be in line with the presence of the kdgA gene homologue in the haloarchaeal ED cluster.

Recent studies of the S. solfataricus KD(P)G aldolase revealed a lack of facial selectivity in the aldolase reaction, catalysing the formation as well as the cleavage of both KDG and KDGal, with GA and pyruvate as substrate and product respectively [22]. At present, no information is available about facial selectivity for the T. tenax enzyme.

Homologues of the T. tenax and S. solfataricus KDG aldolases were identified in many bacterial, archaeal and eukaryal species. However, they share no similarity with the classical ED aldolase (EDA) [21], but are members of the NAL (N-acetylneuraminate lyase) superfamily [41]. Although members of the NAL superfamily catalyse substantially different overall reactions (e.g. dihydrodipicolinate synthases, NAL and trans-o-hydroxybenzylidene-pyruvate aldolase/dehydratase), their catalysis generally proceeds by a Schiff base mechanism. Each of the enzymes of the NAL superfamily harbours a conserved lysine (Lys165 in NAL) located in the sixth strand of β-sheet of the single β/α (TIM) barrel domain [41]. The corresponding active-site lysine residue has indeed been identified in the crystal structure of the KD(P)G aldolase of S. solfataricus (Lys155) [42]. In E. coli K12, two KD(P)G aldolase homologues in addition to the classical EDA were identified (yjhH and yagE). Both are organized in gene clusters encoding ED dehydratase orthologues (yjhG and yagF, [43]), permeases (yjhF and yagG), regulators (yjhIand yagI) and a hypothetical protein (yjhU) or a putative β-xylosidase (yagH) respectively (results not shown). This functional organization indicates that, in E. coli, other related, so far unknown ED modifications may also exist.

KDG kinase

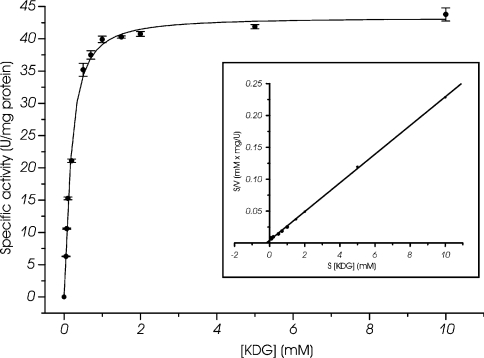

KDG kinase catalyses the phosphorylation of KDG yielding KDPG. Enzyme activity of T. tenax and S. solfataricus was only observed in the presence of ATP and Mg2+. The KDG kinase activity of T. tenax (fraction after gel filtration) was monitored in response to different substrate concentrations, and as shown in Figure 7, the enzyme follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics for KDG (Km=0.178±0.011 mM, Vmax=43.260±0.007 units/mg of protein). The measured enzyme activity of T. tenax was directly proportional to the amount of enzyme added to the assay (62.8±0.3 m-units/1.5 μg, 124.0±0.4 m-units/3 μg; at 5 mM KDG). Since the expression of the S. solfataricus KDG kinase was rather poor, the activity was determined directly after heat precipitation in the presence of 3 mM KDG and was shown to be directly proportional to the amount of enzyme added to the assay (4.1±0.2 m-units/40 μg and 8.3±1.1 m-units/80 μg).

Figure 7. KDG kinase activity of T. tenax.

The KDG kinase activity was determined in a continuous assay at 70 °C by monitoring the formation of GAP after KDPG cleavage via KD(P)G aldolase and GAPN of T. tenax. The rate dependence on the KDG concentration, determined by the TBA assay, is shown. The enzyme follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics for KDG. The inset shows the linear transformation according to Hanes. For the assay, it was ensured that the amount of auxiliary enzymes is not rate-limiting and the measured enzyme activity was directly proportional to the amount of enzyme added to the assay (results not shown). Three independent assays were performed for each substrate concentration and the S.D. is given. The rate-dependent formation of GAP was only monitored in the presence of KDG, ATP, Mg2+, auxiliary enzymes and the KDG kinase of T. tenax.

The coupled KDG kinase assay is not optimal, since KD(P)G aldolase is also active on the substrate KDG, resulting in an unknown effective KDG concentration in the assay. Furthermore, the S. solfataricus KD(P)G aldolase was reported to form the diastereomeric products KDG and KDGal by condensation of GA and pyruvate, and so far we have no information about the stereo-selectivity of the T. tenax enzyme, which was used for the generation of KDG. Therefore the same assay was tested by generating KDG from gluconate by the T. tenax GAD during the assay, which specifically forms KDG, but again allows no determination of the effective KDG concentration. The measured enzyme activity was directly dependent on the gluconate concentration (6.6±0.5, 12.2±0.6, 14.8±0.3 and 22.5±0.9 units/mg of protein with 1, 1.5, 5 and 10 mM gluconate respectively).

In addition, the KDG kinase activity of both enzymes was also analysed using a discontinuous assay by monitoring the formation of ADP from the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of KDG (generated by GAD) via pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase. The time-dependent formation of ADP was only observed in the presence of gluconate, GAD and the KDG kinase of T. tenax or S. solfataricus, whereas no ADP formation was observed with the negative controls (no protein, GAD alone, KDG kinase without GAD and cell-free extract with empty vector) (results not shown).

Obviously, the KDG kinase is the key enzyme in the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway. The enzyme is a member of the ribokinase (PfkB) enzyme family, which is composed of prokaryotic sequences related to ribokinase, including enzymes such as fructokinases, the minor 6-phosphofructokinase of E. coli, 1-phosphofructokinase and archaeal ADP-dependent glucokinases and phosphofructokinases [44,45]. So far, the KDG kinase purified from E. coli was characterized [46] and activity was demonstrated for the gene product of Erwinia chrysanthemi ([47], accession no. X75047, 25% identity with the T. tenax enzyme). The latter enzyme is involved in pectin and hexuronate (glucuronate and galacturonate) catabolism, routes that converge through the common intermediate KDG. KDG kinase activity has also been proposed for the kdgK gene of B. stearothermophilus T6 [48] due to its high similarity to the Erwinia enzyme and the organization in the xylan and glucuronic acid utilization gene cluster.

Homologues of the T. tenax and S. solfataricus KDG kinase were identified in many archaeal genomes [e.g. A. pernix (28% identity), Py. furiosus (30% identity) and Py. aerophilum (31% identity)] and bacterial genomes [Ps. putida (34% identity), B. halodurans (30% identity) and Streptomyces coelicolor (33% identity)]. Interestingly, KDG kinase orthologues were not detected in the genomes of T. acidophilum, T. volcanium and Picrophilus torridus. This suggests either that a strictly non-phosphorylative ED pathway is operative in these thermophilic archaea or that the kdgK gene has been substituted via a nonorthologous gene displacement. In addition, we failed to identify KDG kinase orthologues in the eukarya and, thus, the KDG kinase seems to be a key player in glucose catabolism (semi-phosphorylative ED pathway) and sugar acid (extracellular polymer) degradation in prokaryotes.

GAPN

GAPN catalyses the irreversible, non-phosphorylating oxidation of GAP to 3-phophoglycerate (Figure 1). The T. tenax GAPN has been studied in detail previously [32,33,49]. The GAPN of S. solfataricus shows high similarity (56% identity) to the enzyme of T. tenax. The clustering of gapN with ED genes in S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii underlines the role of GAPN in the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway and more generally in the common shunt of the EMP pathway.

The S. solfataricus GAPN activity was determined in a continuous assay at 70 °C by monitoring the formation of NADPH or NADH. The enzyme follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics for NADP+ and GAP. For NADP+ a Km of 0.099±0.009 mM and a Vmax of 3.3±0.1 units/mg of protein were determined, and for GAP a Km of 0.453±0.052 mM and a Vmax of 3.4±0.1 units/mg of protein were determined. GAP concentrations above 4 mM had an inhibitory effect on GAPN activity. The enzyme shows only remote activity with NAD+ and no saturation of the enzyme was observed up to 10 mM NAD+ (results not shown). A detailed characterization of the S. solfataricus enzyme is currently under way (H. Ahmed, T. J. G. Ettema, J. van der Oost and B. Siebers, unpublished work).

In summary, the proposed activities of the ED genes could be confirmed by analysis of the recombinant gene products: GDH, GAD, KD(P)G aldolase, KDG kinase and GAPN (Table 2). In addition, the dual activity of the KD(P)G aldolase, which is active on non-phosphorylated as well as phosphorylated substrates, suggests that, in contrast with previous assumptions, the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway is operative in these hyperthermophiles.

Table 2. Specific activities of the recombinant ED enzymes of T. tenax and S. solfataricus.

Errors are given from three independent measurements. n.d., not detected.

| Enzyme activity | Organism | Substrate concentration (mM) | Specific activity (units/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAD | T. tenax | 10 mM gluconate | 0.065±0.006 |

| 10 mM galactonate | n.d. | ||

| KD(P)G aldolase | T. tenax | 2 mM GA, 5 mM pyruvate | 2.1±0.1 |

| 2 mM GAP, 5 mM pyruvate | 11.5±0.6 | ||

| S. solfataricus | 2 mM GA, 5 mM pyruvate | 2.2±0.2 | |

| 2 mM GAP, 5 mM pyruvate | 5.8±0.7 | ||

| KDG kinase | T. tenax | 5 mM KDG, 2 mM ATP* | 41.6±0.3 |

| S. solfataricus† | 3 mM KDG* | 0.104±0.001 | |

| GAPN | S. solfataricus† | 3 mM GAP, 2 mM NADP+ | 3.36±0.08 |

* KDG was generated by KD(P)G aldolase and purified by anion-exchange chromatography.

† Protein fraction after heat precipitation.

In vitro reconstruction of the ED pathways

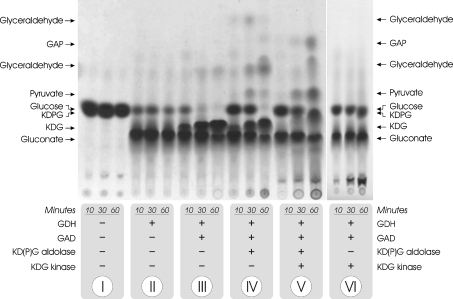

In order to analyse the activities of the different ED enzymes and to confirm their function in the ED pathway, [U-14C]glucose was incubated in the presence of different combinations of T. tenax ED enzymes [GDH, GAD, KD(P)G aldolase and KDG kinase] and co-substrates (NADP+, ATP and Mg2+). Subsequently, the labelled intermediates that were formed during the incubation were separated by TLC and afterwards detected by autoradiography (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Reconstruction of the ED pathway in vitro.

[U-14C]glucose was incubated in the presence of different combinations of ED enzymes from T. tenax [GDH, GAD, KD(P)G aldolase and KDG kinase; protein fractions after heat precipitation] as indicated (10, 30 and 60 min at 70 °C respectively), and the labelled intermediates were separated by TLC and visualized using autoradiography. The labelling pattern in the presence of KDG kinase and KD(P)G aldolase (V) indicates the co-existence of both the semi-phosphorylative and non-phosphorylative ED modifications in T. tenax.

The stepwise addition of GDH, GAD and KD(P)G aldolase to labelled glucose (I–IV; Figure 8) reveals the characteristic intermediates of the non-phosphorylative ED pathway: gluconate, KDG, pyruvate and GA. However, after the addition of KDG kinase and co-substrates (ATP and Mg2+), KDPG formation is observed in the presence or absence of KD(P)G aldolase (V and VI; Figure 8), while KDG disappears. In addition, in the presence of KD(P)G, aldolase formation of GAP is observed, as a characteristic intermediate of the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway, in addition to formation of gluconate, pyruvate and some GA. The identification of GA and GAP in this sample indicates that, at least in vitro, both the non-phosphorylative and the semi-phosphorylative versions of the ED pathway are active in parallel. Identical labelling patterns were observed when using the KD(P)G aldolase and KDG kinase of S. solfataricus instead of the two T. tenax enzymes (results not shown).

A possible role of the ED pathway in gluconeogenesis was analysed using a similar approach with 14C-labelled pyruvate. However, in the presence of KD(P)G aldolase, GAD and GDH and the respective substrates and co-substrate (GA, pyruvate and NADPH), only the formation of KDG was observed (results not shown), indicating that the pathway is at least partly irreversible, or it is catalysed by a distinct set of enzymes.

In addition, the in vitro reconstruction experiments demonstrate that gluconolactonase activity (EC 3.1.1.17) is not needed for the functional reconstruction of the pathway. Interestingly, whereas a potential gluconolactonase-encoding gene seems to be absent from the T. tenax genome, potential candidates (SSO3041 and ST2555) were identified adjacent to the GDH-encoding genes (SSO3042 and ST2556) in S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii. The clustering of these genes in these organisms indicates a functional link between their gene products. Possibly, the presence of a gluconolactonase-encoding gene allows an accelerated glucose turnover in S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii, since the ED pathway seems to be the only route for glucose catabolism in these organisms.

In vivo operation of a branched ED pathway in T. tenax and S. solfataricus

The aforementioned in vitro results strongly suggest functional non- and semi-phosphorylative versions of the ED pathway in T. tenax and S. solfataricus (Figure 1). This would be the first demonstration of the presence of the semi-phosphorylative ED pathway in T. tenax and S. solfataricus in particular, and in hyperthermophilic archaea in general, and the first indication of the presence of both ED modifications in one organism (pathway dualism). The conserved functional organization of the ED genes encoding enzymes of the semi-phosphorylative modification (KDG kinase and GAPN) and for the common, ‘core’-modified ED shunt (GAD; KD(P)G aldolase) raises questions about their regulation as well as the utilization of both modified ED versions in vivo.

In order to prove that the two ED modifications are operative in vivo, enzyme assays were performed on crude extracts of T. tenax and S. solfataricus cells grown on glucose. As shown in Table 3, the enzyme activities of GAD, KD(P)G aldolase, KDG kinase and GAPN could be measured in these crude extracts, indicating that the operation of a semi-phosphorylative ED pathway is possible in these organisms. As a peculiarity, GAD activity on galactonate was only observed in S. solfataricus crude extracts, supporting our studies of the recombinant T. tenax enzyme and reports about pathway promiscuity in S. solfataricus. In addition, it is demonstrated that aldolase activity could be demonstrated with pyruvate and either GA or GAP as substrates. This observation is in good agreement with the results of the characterization of the recombinant KD(P)G aldolase. However, our results do not rule out that a non-phosphorylative ED pathway is operating in parallel with the semi-phosphorylative version.

At present, no information is available for the specific enzymes of the non-phosphorylative ED pathway. Several dehydrogenases and aldehyde oxidoreductases as well as a homologue for glycerate kinase (COG2379, T. tenax AJ621345, SSO0666) are encoded by the T. tenax and S. solfataricus [2–4] genomes, allowing the operation of the non-phosphorylative ED modification in both organisms. The putative glycerate kinase of T. tenax shows high similarity to the orthologues identified in S. solfataricus (26% identity), T. acidophilum (23% identity) and T. maritima (33% identity); however, no functional information is available at present for any of the gene product. Since glycerate kinase represents the key activity of the non-phosphorylative ED pathway, expression of the T. tenax enzyme is currently under way in order to elucidate its function in vivo.

Physiological implications

The presence of various pathways for carbon metabolism in one organism raises questions about their physiological significance. With the anaerobe T. tenax and the aerobe S. solfataricus, two hyperthermophiles are studied, which exhibit significant differences in the central carbon metabolism and thus might allow one to gain new insights into the flexibility of carbon metabolism.

Genome data and biochemical studies indicate that the anaerobe T. tenax uses at least two different pathways for glucose metabolism, a modification of the reversible EMP pathway and one or two modifications of the ED pathway, a semi-phosphorylative and a non-phosphorylative version. The clustering of the gaa gene, encoding a GAA, with the ED genes indicates the central role of ED modifications in the hydrolytic degradation of polysaccharides (e.g. glycogen). In contrast, the modified EMP pathway seems to have a central function in the phosphorolytic glycogen degradation by glycogen phosphorylase, which was characterized recently [4,50]. The selection of the different pathways in vivo seems to be influenced strongly by the energy demand of the cell. Whereas no ATP is generated by the ED modifications, one (glucose degradation) or two ATPs (phosphorolytic glycogen degradation) are generated using the EMP variant, taking into account that: (i) PPi, the phosphoryl donor of phosphofructokinase, is a waste product of the cell [51], and (ii) GAPN is used for glucose catabolism, which omits the formation of 1,3-diphosphoglycerate and as such does not couple the oxidation of GAP with the generation of ATP.

In the aerobe S. solfataricus, the modifications of the ED pathway seem to represent the only pathway for glucose and galactose degradation [22]. Analyses of genome data indicate an incomplete EMP pathway, and it is suggested that the enzymes that are present may be involved in fructose degradation or in the anabolic gluconeogenetic direction for glycogen synthesis [2,3,52].

The identification and characterization of the enzymes that constitute the modified ED pathway shed new light on the functional role of this glycolytic pathway in hyperthermophilic archaea and suggests a much broader distribution of ED-like pathways in other archaea, bacteria and eukarya than was previously assumed. This finding supports the important roles of the ED pathway and its variants in glucose degradation and as a funnel for sugar acid (polymer) degradation, and again underlines the variability and flexibility of central carbon-metabolizing pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. We thank C. A. Fierke for providing the expression plasmid of T. maritima KDPG aldolase.

References

- 1.Ronimus R. S., Morgan H. W. Distribution and phylogenies of enzymes of the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway from archaea and hyperthermophilic bacteria support a gluconeogenic origin of metabolism. Archaea. 2002;1:199–221. doi: 10.1155/2003/162593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verhees C. H., Kengen S. W. M., Tuininga J. E., Schut G. J., Adams M. W. W., de Vos W. M., van der Oost J. The unique features of glycolytic pathways in Archaea. Biochem. J. 2003;375:231–246. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verhees C. H., Kengen S. W. M., Tuininga J. E., Schut G. J., Adams M. W. W., de Vos W. M., van der Oost J. The unique features of glycolytic pathways in Archaea. Biochem. J. 2004;377:819–822. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siebers B., Tjaden B., Michalke K., Dörr C., Ahmed H., Zaparty M., Gordon P., Sensen C. W., Zibat A., Klenk H., et al. Reconstruction of the central carbohydrate metabolism of Thermoproteus tenax by use of genomic and biochemical data. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:2179–2194. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.2179-2194.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Rosa M., Gambacorta A., Nicolaus B., Giardina P., Poerio E., Buonocore V. Glucose metabolism in the extreme thermoacidophilic archaebacterium Sulfolobus solfataricus. Biochem. J. 1984;224:407–414. doi: 10.1042/bj2240407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budgen N., Danson M. J. Metabolism of glucose via a modified Entner-Doudoroff pathway in the thermoacidophilic archaebacterium Thermoplasma acidophilum. FEBS Lett. 1986;196:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siebers B., Hensel R. Glucose catabolism of the hyperthermophilic archaeum Thermoproteus tenax. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1993;111:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selig M., Schönheit P. Oxidation of organic-compounds to CO2 with sulfur or thiosulfate as electron-acceptor in the anaerobic hyperthermophilic archaea Thermoproteus tenax and Pyrobaculum islandicum proceeds via the citric-acid cycle. Arch. Microbiol. 1994;162:286–294. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siebers B., Wendisch V. F., Hensel R. Carbohydrate metabolism in Thermoproteus tenax: in vivo utilization of the non-phosphorylative Entner-Doudoroff pathway and characterization of its first enzyme, glucose dehydrogenase. Arch. Microbiol. 1997;168:120–127. doi: 10.1007/s002030050477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selig M., Xavier K. B., Santos H., Schönheit P. Comparative analysis of Embden-Meyerhof and Entner-Doudoroff glycolytic pathways in hyperthermophilic archaea and the bacterium Thermotoga. Arch. Microbiol. 1997;167:217–232. doi: 10.1007/BF03356097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Entner N., Doudoroff M. Glucose and gluconic acid oxidation of Pseudomonas saccharophila. J. Biol. Chem. 1952;196:853–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conway T. The Entner-Doudoroff pathway: history, physiology and molecular biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1992;9:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szymona M., Doudoroff M. Carbohydrate metabolism in Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1958;22:167–183. doi: 10.1099/00221287-22-1-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreesen J. R., Gottschalk G. The occurrence of the modified Entner-Doudoroff pathway in Clostridium aceticum. Arch. Microbiol. 1969;69:160–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00409760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomlinson G. A., Koch T. K., Hochstein L. I. The metabolism of carbohydrates by extremely halophilic bacteria: glucose metabolism via a modified Entner-Doudoroff pathway. Can. J. Microbiol. 1974;20:1085–1091. doi: 10.1139/m74-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elzainy T. A., Hassan M. M., Allam A. M. New pathway for nonphosphorylated degradation of gluconate by Aspergillus niger. J. Bacteriol. 1973;114:457–459. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.1.457-459.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukund S., Adams M. W. The novel tungsten-iron-sulfur protein of the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus furiosus, is an aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase. Evidence for its participation in a unique glycolytic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:14208–14216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schicho R. N., Snowden L. J., Mukund S., Park J. B., Adams M. W. W., Kelly R. M. Influence of tungsten on metabolic patterns in Pyrococcus furiosus, a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Arch. Microbiol. 1993;159:380–385. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kardinahl S., Schmidt C. L., Hansen T., Anemuller S., Petersen A., Schafer G. The strict molybdate-dependence of glucose-degradation by the thermoacidophile Sulfolobus acidocaldarius reveals the first crenarchaeotic molybdenum containing enzyme – an aldehyde oxidoreductase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;260:540–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grogan D. W. Phenotypic characterization of the archaebacterial genus Sulfolobus: comparison of five wild-type strains. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:6710–6719. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6710-6719.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchanan C. L., Connaris H., Danson M. J., Reeve C. D., Hough D. W. An extremely thermostable aldolase from Sulfolobus solfataricus with specificity for non-phosphorylated substrates. Biochem. J. 1999;343:563–570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamble H. J., Heyer N. I., Bull S. D., Hough D. W., Danson M. J. Metabolic pathway promiscuity in the Archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus revealed by studies on glucose dehydrogenase and 2-keto-3-deoxygluconate aldolase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34066–34072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zillig W., Stetter K. O., Schäfer W., Janekovic D., Wunderl S., Holz I., Palm P. Thermoproteales: a novel type of extremely thermoacidophilic anaerobic archaebacteria isolated from Icelandic solfatares. Zentbl. Bakteriol. Hyg. 1 Abt. Org. C. 1981;2:205–227. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dörr C., Zaparty M., Tjaden B., Brinkmann H., Siebers B. The hexokinase of the hyperthermophile Thermoproteus tenax – ATP-dependent hexokinases and ADP-dependent glucokinases, two alternatives for glucose phosphorylation in Archaea. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:18744–18753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zillig W., Stetter K. O., Wunderl S., Wunderl S., Priess H., Scholz J. The Sulfolobus-‘Caldariella’ group: taxonomy on the basis of the structure of DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Arch. Microbiol. 1980;125:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunner N. A., Siebers B., Hensel R. Role of two different glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases in controlling the reversible Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway in Thermoproteus tenax: regulation on protein and transcript level. Extremophiles. 2001;5:101–109. doi: 10.1007/s007920100181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brinkman A. B., Bell S. D., Lebbink R. J., de Vos W. M., van der Oost J. The Sulfolobus solfataricus Lrp-like protein LysM regulates lysine biosynthesis in response to lysine availability. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:29537–29549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. 2nd edn. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. Molecular Cloning – A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skoza L., Mohos S. Stable thiobarbituric acid chromophore with dimethyl sulphoxide. Application to sialic acid assay in analytical de-O-acetylation. Biochem. J. 1976;159:457–462. doi: 10.1042/bj1590457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gottschalk G., Bender R. D-gluconate dehydratase from Clostridium pasteurianum. Methods Enzymol. 1982;90:283–287. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)90141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamble F. J., Milburn C. C., Taylor G. L., Hough D. W., Danson M. J. Gluconate dehydratase from the promiscuous Entner-Doudoroff pathway in Sulfolobus solfataricus. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunner N. A., Brinkmann H., Siebers B., Hensel R. NAD+-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Thermoproteus tenax. The first identified archaeal member of the aldehyde dehydrogenase superfamily is a glycolytic enzyme with unusual regulatory properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6149–6156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorentzen E., Hensel R., Knura T., Ahmed H., Pohl E. Structural basis of allosteric regulation and substrate specificity of the non-phosphorylating glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Thermoproteus tenax. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:815–828. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffiths J. S., Wymer N. J., Njolito E., Niranjanakumari S., Fierke C. A., Toone E. J. Cloning, isolation and characterization of the Thermotoga maritima KDPG aldolase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:545–550. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babbitt P. C., Hasson M. S., Wedekind J. E., Palmer D. R. J., Barrett W. C., Reed G. H., Rayment I., Ringe D., Kenyon G. L., Gerlt J. A. The enolase superfamily: a general strategy for enzyme-catalyzed abstraction of the alpha-protons of carboxylic acids. Biochemistry. 1996;35:16489–16501. doi: 10.1021/bi9616413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bender R., Gottschalk G. Purification and properties of D-gluconate dehydratase from Clostridium pasteurianum. Eur. J. Biochem. 1973;40:309–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bender R., Gottschalk K. Enzymatic synthesis of 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-gluconate from D-gluconate. Anal. Biochem. 1974;61:275–279. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kersters K., De Ley J. D-glucose dehydratase from Alcaligenes. Methods Enzymol. 1975;42:301–304. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(75)42131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim S., Lee S. B. Identification and characterization of Sulfolobus solfataricus D-gluconate dehydratase: a key enzyme in the nonphosphorylated Entner-Doudoroff pathway. Biochem. J. 2005;387:271–280. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubbard B. K., Koch M., Palmer D. R. J., Babbitt P. C., Gerlt J. A. Evolution of enzymatic activities in the enolase superfamily: characterization of the (D)-glucarate/galactarate catabolic pathway in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14369–14375. doi: 10.1021/bi981124f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Babbitt P. C., Gerlt J. A. Understanding enzyme superfamilies – chemistry as the fundamental determinant in the evolution of new catalytic activities. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30591–30594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Theodossis A., Walden H., Westwick E. J., Connaris H., Lamble H. J., Hough D. W., Danson M. J., Taylor G. L. The structural basis for substrate promiscuity in 2-keto-3-deoxygluconate aldolase from the Entner-Doudoroff pathway in Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:43886–43892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peekhaus N., Conway T. What's for dinner?: Entner-Doudoroff metabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:3495–3502. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3495-3502.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bork P., Sander C., Valencia A. Convergent evolution of similar enzymatic function on different protein folds – the hexokinase, ribokinase, and galactokinase families of sugar kinases. Protein Sci. 1993;2:31–40. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ito S., Fushinobu S., Yoshioka I., Koga S., Matsuzawa H., Wakagi T. Structural basis for the ADP-specificity of a novel glucokinase from a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Structure. 2001;9:205–214. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cynkin M. A., Ashwell G. Uronic acid metabolism in bacteria. IV. Purification and properties of 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-gluconokinase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1960;235:1576–1579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat N., Nasser W., Robert-Baudouy J. Molecular characterization of the Erwinia chrysanthemi kdgK gene involved in pectin degradation. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:2386–2392. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2386-2392.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shulami S., Gat G., Sonenshein A. L., Shoham Y. The glucuronic acid utilization gene cluster from Bacillus stearothermophilus T-6. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:3695–3704. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3695-3704.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pohl E., Brunner N., Wilmanns M., Hensel R. The crystal structure of the allosteric non-phosphorylating glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeum Thermoproteus tenax. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19938–19945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmed H., Tjaden B., Hensel R., Siebers B. Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas and Entner-Doudoroff pathways in Thermoproteus tenax: metabolic parallelism or specific adaptation? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2004;32:2–4. doi: 10.1042/bst0320303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siebers B., Klenk H. P., Hensel R. PPi-dependent phosphofructokinase from Thermoproteus tenax, an archaeal descendant of an ancient line in phosphofructokinase evolution. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:2137–2143. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2137-2143.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.She Q., Singh R. K., Confalonieri F., Zivanovic Y., Allard G., Awayez M. J., Chan-Weiher C. C. Y., Clausen I. G., Curtis B. A., De Moors A., et al. The complete genome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:7835–7840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141222098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]