Abstract

NPC (Niemann–Pick type C) disease is a rare lipidosis characterized by the accumulation of LDL (low-density lipoprotein)-derived non-esterified cholesterol in the E/L (endosomal/lysosomal) system. The gene products that are responsible for the two NPC complementation groups are distinct and dissimilar, yet their cellular and disease phenotypes are virtually indistinguishable. To investigate the relationship between NPC1 and NPC2 and their potential role in NPC disease pathogenesis, we have developed a method for the rapid and efficient isolation of late endocytic vesicles from mouse liver by magnetic chromatography. Late endosomes from Wt (wild-type) and NPC1 mice were found to differ not only in their cholesterol and sphingomyelin content, as expected, but also in their non-esterified (‘free’) fatty acid content, with NPC1 vesicles showing an approx. 7-fold increase in non-esterified fatty acid levels compared with Wt vesicles. Furthermore, we show that the NPC2 protein is in an incompletely deglycosylated form in NPC1 late endosomes by a mechanism that is specific to the NPC2 protein and not a global aberration of protein glycosylation/deglycosylation or trafficking, since NPC2 secreted from NPC1 cells is indistinguishable from that secreted from Wt cells. Also, a greater proportion of the normally soluble cellular NPC2 protein partitions with detergent-insoluble late endosomal internal membrane domains in NPC1 vesicles. In addition, we show that, although a small amount of the NPC2 protein associates with these membranes in Wt vesicles, this localization becomes much more pronounced in NPC1 vesicles. These results suggest that the function of the NPC2 protein may be compromised as well in NPC1 endosomes, which might explain the paradoxical phenotypic similarities of the two NPC disease complementation groups.

Keywords: glycosylation, late endosome, lipid, magnetic isolation, Niemann–Pick type C

Abbreviations: AO, Acridine Orange; EDS, energy dispersive spectroscopy; E/L, endosomal/lysosomal; Lamp1, lysosome-associated membrane protein 1; LBPA, lysobisphosphatidic acid; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; M6P, mannose 6-phosphate; NEFA, non-esterified (‘free’) fatty acid; NPC, Niemann–Pick type C; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; PMS, post-mitochondrial supernatant; PNGase F, peptide N-glycosidase F; SM, sphingomyelin; SOD, superoxide dismutase; SPD, superparamagnetic dextran-coated iron oxide; StART, StAR (steroidogenic acute regulatory protein)-related lipid transfer; TGN, trans-Golgi network; Wt, wild-type

INTRODUCTION

NPC (Niemann–Pick type C) is a rare lipidosis characterized by the accumulation of LDL (low-density lipoprotein)-derived non-esterified cholesterol in the E/L (endosomal/lysosomal) system and a subsequent disruption of cholesterol homoeostasis [1,2]. Cholesterol also accumulates in the TGN (trans-Golgi network), and its relocation to and from the plasma membrane is delayed [3]. Patients exhibit progressive neurodegeneration and hepatosplenomegaly, which leads to death during early childhood [3].

The dissimilarity of the gene products responsible for the two NPC complementation groups [4,5] has raised more questions than insight regarding disease pathogenesis. The majority of NPC patients (∼95%) carry mutations in the NPC1 gene. This gene encodes a large multi-pass transmembrane late endosomal protein, NPC1, which has been implicated in the movement of lipids from late endosomes [6–8]. Recently, the NPC1 protein has been shown to bind to a photoactivated cholesterol analogue [9]; however, its exact substrate(s) has not yet been determined. NPC1 has also been shown to facilitate the transport of fatty acids, but not cholesterol, across bacterial membranes, suggesting that it may play a role in endosomal membrane dynamics through these actions [10].

Comparatively less is known about the second gene, NPC2, mutations in which account for approx. 5% of NPC disease patients. NPC2 is a small soluble lysosomal protein that was first isolated as a cholesterol-binding protein secreted from human epididymis [11] and was subsequently identified as NPC2 using a proteomics approach [5,12]. The role of this protein in NPC disease pathogenesis is not clear, but there is compelling evidence for a role in cholesterol transport, since it has been shown to contain a cholesterol-binding pocket whose integrity is required for maintenance of cellular cholesterol levels [13,14]. However, there has been some uncertainty regarding the mechanism of this action, since the structure of the bovine NPC2 protein lacks an open hydrophobic cavity, indicating that the protein would have to undergo a significant conformational change to allow for cholesterol binding [13].

To date, there have been few studies investigating the relationship between NPC1 and NPC2 and their role in NPC disease pathogenesis. Although it was originally supposed that the two proteins would interact with each other [5], there has been no experimental evidence to support this hypothesis. Recently, several reports have suggested that the two proteins co-operate with each other in facilitating late endosomal lipid transport, but the nature of such a co-operation has not been elucidated [15,16]. However, as mentioned above, a deficiency in either NPC1 or NPC2 results in an indistinguishable cellular phenotype. A potential explanation for this may be that a lack of NPC1 activity affects the function and/or location of NPC2, leading to a phenotype that is a result of NPC2 malfunction. To test this hypothesis and to determine what effects, if any, deficient NPC1 activity has on the NPC2 protein and to facilitate these studies, we have developed a method to isolate late endosomes from the livers of Wt (wild-type) and NPC1 mice based on magnetic chromatography of endocytosed dextran-covered colloidal iron particles. By harvesting livers at progressively longer times following particle injection, we were able to isolate fractions that were specifically enriched for early endosomes, late endosomes and lysosomes, as assessed by localization of marker proteins. Late endosomes from Wt and NPC1 mice were different in their protein/lipid composition, similar to those previously reported [16–18], validating this new vesicle isolation approach. Interestingly, NPC1 vesicles also contained previously unappreciated elevated levels of NEFAs [non-esterified (‘free’) fatty acids]. In addition, we found that the NPC2 protein is incompletely deglycosylated in NPC1 late endosomes, with a greater proportion of the normally soluble NPC2 protein localized to detergent-insoluble domains in NPC1 vesicles. Even though a small amount of NPC2 protein associates with late endosomal internal membranes in Wt vesicles, this localization becomes much more pronounced in NPC1 vesicles. These events are specific to the NPC2 protein and not a global aberration of protein glycosylation/deglycosylation or trafficking, and may have implications for the function or lack thereof of the NPC2 protein in NPC1 endosomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) unless otherwise indicated. Antibodies against Rab5, Rab7, calregulin and CD81, as well as secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). The antibody against copper SOD (superoxide dismutase) was from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.), and the antibody against TGN38 was from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). The polyclonal antibody against the MLN64 StART [StAR (steroidogenic acute regulatory protein)-related lipid transfer] domain [19] and the anti-NPC1 polyclonal antibody [10] have been described. The GM5387, GM41B and GM3123 human fibroblast cell lines were from Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ, U.S.A.), and the NPC-null mutant cell line (DMN98.16) was a gift from Dr Peter Pentchev [NIDDK (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.].

Production of antibodies

Rab9 polyclonal antibodies were produced against a 74-amino-acid fragment (amino acids 128–201) that has the least homology with the other Rab-family proteins, as determined by ClustalW alignment. The fragment was isolated by PCR from a Rab9 cDNA [20] and was cloned into the pet-29 prokaryotic expression vector (EMD Biosciences). The Rab9 fragment–His6 fusion protein was expressed in BL21 pLysS bacteria by induction with 0.4 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside) at 30 °C for 4.5 h and purified on a nickel-affinity column under denaturing conditions. The purified protein was resolved by SDS/12% PAGE, after which the protein band was excised and used to immunize New Zealand white rabbits.

Anti-NPC2 antibodies were produced using full-length bacterially expressed protein as above, whereas anti-α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase antibodies were produced using recombinant protein expressed in CHO (Chinese-hamster ovary) cells [21]. Anti-Lamp1 (lysosome-associated membrane protein 1) antibodies were produced against the terminal 11 amino acids (amino acids 379–389) representing the cytoplasmic tail of the Lamp1 protein [22].

Isolation of endocytic vesicles from mice by magnetic chromatography

SPD (superparamagnetic dextran-coated iron oxide) particles were prepared essentially as described in [23]. Briefly, 5 ml of 1.2 M FeCl2 and 5 ml of 1.8 M FeCl3 were mixed with 5 ml of 30% NH4OH, while stirring at room temperature (25 °C). Particles were collected with a large magnet and were washed first with 5% NH4OH and then twice with distilled water. Particles were then resuspended in 40 ml of 0.3 M HCl and mixed for 30 min, after which 2 g of solid dextran T-40 was added and the solution was mixed for 16 h at room temperature. The colloidal suspension was dialysed against cold water for 48 h. Following the removal of large aggregates by centrifugation at 20000 g, particles were concentrated ∼7-fold using poly(ethylene glycol) with an 8 kDa molecular-mass cut-off. Before injection, NaCl was added to the colloidal suspension to a final concentration of 154 mM.

Mice maintained on a regular chow diet were injected with particles at 40–50 days of age, before the onset of visually detectable ataxia associated with NPC1 mice [24]. Particles (100 μl) were injected intravenously into the mouse tail veins. After 0.5, 1, 2 or 4 h, mice were killed, and their livers were excised. Livers were resuspended in diluent B (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM Tricine/NaOH, pH 7.8, and 1 mM EDTA) at a concentration of 2.5 g/10 ml and chopped into small pieces. After homogenizing with ten strokes of a Potter–Elvejehn homogenizer at 700 rev./min, the lysate was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in one-half of the original volume of diluent B and centrifuged again at 1000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were combined, passed through a Dounce homogenizer ten times and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to harvest the PMS (post-mitochondrial supernatant). Vesicle isolation was achieved by passing this supernatant through a column containing steel mesh enclosed within a 0.6 T magnet (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). The column flow-through was centrifuged at 100000 g for 1 h at 4 °C to yield cytosol. The column was washed with 10 column vol. of diluent B, and then vesicles were eluted with 1 column vol. of diluent B following removal of the column from the magnet. Vesicles were used immediately for electron microscopy or in vitro acidification assays or flash frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath and stored at −80 °C.

Electron microscopy and EDS (energy dispersive spectroscopy)

Purified vesicles were pelleted at 25000 g for 30 min at 4 °C and then fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 3 h. The pellet was washed with cacodylate buffer and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in cacodylate buffer for 1 h. The pellet was washed again with cacodylate buffer and dehydrated with sequential changes of increasing concentrations of ethanol and propylene oxide and then embedded in EMbed 812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA, U.S.A.). The pellet was ultrathin-sectioned; half the grids were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for morphological observation. The other half was left unstained and used for EDS to identify the elemental composition of the electron-dense particles.

In vitro acidification assays

The integrity of the isolated vesicles was assessed by performing AO (Acridine Orange) fluorescence-quenching assays as described previously [25]. Briefly, 100 μg of vesicles were mixed with assay buffer (1.5 mg/ml cytosol, 150 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris/Hepes, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgSO4, 5 μM AO and 100 μM PMSF) in a glass cuvette. Vesicle acidification was initiated by addition of an ATP regeneration mix (1 mM ATP, 5 mM creatine phosphate and 10 units/ml creatine phosphokinase) and inhibited by addition of 1 μM nigericin. Fluorescence measurements were performed with excitation at 450 nm (slit width, 1 nm) and emission at 525 nm (slit width, 2 nm) over 7 min in a 37 °C water jacket using a DeltaRam fluorescence spectroscopy system (Photon Technology International, Lawrenceville, NJ, U.S.A.).

Western blotting

For vesicle profiling, 10 μg of protein from each vesicle fraction was subjected to electrophoresis through a 4–12% Bis-Tris pre-cast gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.) in Mes buffer and transferred on to a Protran membrane using an XCell II apparatus (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Blots were probed using primary antibodies against Rab7, Rab5 or α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase and secondary anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using Lumi-light (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.), according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

For comparison of proteins in the PMS and isolated vesicle preparations, an equal amount of each fraction was subjected to electrophoresis, blotting and processing as above. For comparison of proteins in Wt and NPC1 vesicles, 10 μg of protein from each vesicle preparation was processed as above. For detection of NPC1 in vesicle preparations, 20 μg of protein was subjected to electrophoresis through a 3–8% Tris/acetate pre-cast gel (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions, blotted, and processed as above. For analyses of glycosylation differences, 10 μg of protein from Wt and NPC1 vesicles was digested with PNGase F (peptide N-glycosidase F) (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.), according to the manufacturer's instructions and then subjected to electrophoresis, blotting and processing as above.

For analyses of proteins in separated membrane fractions, 950 μl of each fraction was precipitated with 1/5 vol. of 100% trichloroacetic acid for 30 min on ice. Samples were centrifuged at 20000 g at 4 °C for 15 min. The pellets were washed in ice-cold acetone, centrifuged at 20000 g at 4 °C for 5 min, before being dried and subjected to electrophoresis, blotting and processing as above.

Cholesterol and fatty acid quantification

The cholesterol concentrations in vesicle preparations and PMS were determined using a diagnostic cholesterol reagent (Sigma–Aldrich), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and comparison with a standard curve. Four independent preparations were used for each sample in duplicate.

The concentration of NEFAs in Wt and NPC1 vesicles was determined using a colorimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics) and comparison with a standard curve. Four independent preparations were used for each sample in duplicate.

Analysis of secreted and intracellular proteins from cell lines derived from Wt and NPC1 mice

Cell lines from 3–6-day-old Wt and NPC1 mice [26] were generated by killing mice in a sterile environment and removing their liver tissue, which was minced into 3–4-mm pieces. These were washed in PBS, transferred to 1 ml of ice-cold 0.25% trypsin/100 mg of tissue and incubated at 4 °C for 16 h. Cells were dispersed by pipetting and were then kept in culture until they began to proliferate. Wt and NPC1 cells were each seeded in three wells of a six-well plate and maintained in Opti-MEM® supplemented with 0.292 mg/ml L-glutamine and 0.25 mg/ml gentamicin in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 4 days. At the end of that time, the culture medium from each well was collected and concentrated in separate Centricon-3 concentrators (Millipore, Billerica, MA, U.S.A.). The cells in each well were lysed in buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.9, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Igepal and 1 mM PMSF), clarified by centrifugation at 20000 g for 5 min, and then the protein concentration was determined by the fluorescamine method as described previously [27]. Cell lysates (5 μg) and a volume of culture medium corresponding to 15 μg of cellular protein were subjected to electrophoresis through a 4–12% Bis-Tris pre-cast gel (Invitrogen) in Mes buffer, blotted, and processed as above.

Detergent solubilization of proteins

Vesicles were pelleted by centrifugation at 20000 g for 30 min at 4 °C, resuspended at 1 mg/ml in cold Triton X-114 lysis buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-114 and protease inhibitor cocktail) and incubated with agitation for 16 h at 4 °C. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation at 20000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was washed with a small volume of lysis buffer, which was then combined with the supernatant and layered on top of a sucrose cushion (6% sucrose, 0.06% Triton X-114, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 min and then centrifuged at 3000 g for 2 min at room temperature. The detergent droplet at the bottom of the tube, containing integral membrane and membrane-associated proteins [28], was separated from the rest of the soluble fraction. The insoluble, soluble and detergent fractions were freeze-dried and subjected to Western blotting as described above.

TLC

For lipid comparisons in Wt and NPC1 vesicles, an amount of lipid equivalent to 100 μg of protein was extracted from four independent vesicle preparations per sample using the standard Folch procedure [29] and spotted on to silica gel 60 plates (EM Separations, Gibbstown, NJ, U.S.A.). High-performance TLC was performed using chloroform/methanol/30% ammonia (65:35:5, by vol.) as a solvent system for the separation of phospholipids and cyclohexane/ethyl ethanoate (3:2, v/v) as a solvent system for the separation of NEFAs. Lipids were visualized by charring after spraying with a 3% cupric acetate solution in 8% phosphoric acid. TLC plates were scanned, and bands were quantified using the public-domain ImageJ program (National Institutes of Health).

For lipid comparisons in Wt and NPC1 PMS, 50 μg of protein from four independent preparations per sample was used for extraction and TLC as above. For analysis of lipid content in separated membrane fractions, 50 μl of each fraction was used for extraction and TLC as above.

For NEFA comparisons in human fibroblast cell lines, 50 μg of cellular protein was used for extraction and TLC as above.

Gradient centrifugation of membrane domains

Separation of internal and limiting membranes was performed as described previously [30]. Briefly, vesicles were subjected to three rounds of freezing/thawing before being centrifuged at 20000 g for 45 min at 4 °C. The pellet, containing the membrane fraction of the vesicles, was resuspended in 40% sucrose in 3 mM imidazole, pH 7.4, and loaded at the bottom of an 8–40% linear sucrose gradient prepared in the same buffer. The sample was centrifuged at 35000 rev./min for 19 h at 4 °C in an SW41 rotor. Fractions of 1 ml were collected from the top of the tube and used for protein and lipid analyses.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of endocytic vesicles

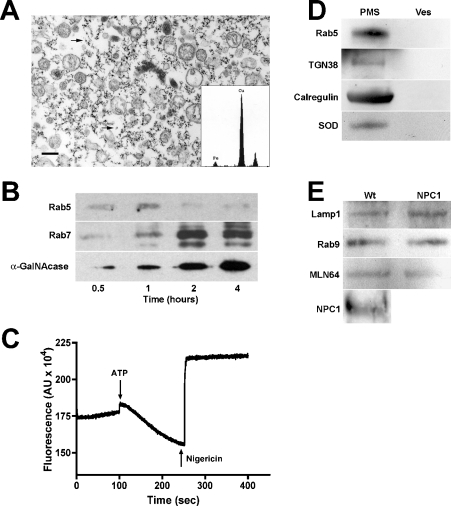

SPD particles have been used previously to purify endocytic vesicles from the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum [23]. We have adapted this technique for use in small animals for studies of mouse models of E/L storage disorders, as it allows for large-scale preparation of endocytic organelles for biochemical and proteomic analyses. Since these SPD particles cannot be metabolized, we hypothesized that, upon intravenous injection, they would cycle through the liver and be endocytosed by that organ. Therefore mice were injected with particles, and their livers were subjected to homogenization and magnetic chromatography to purify endocytic vesicles. The efficiency of purification was monitored by enzymatic assays of the E/L system-specific enzyme marker β-galactosidase. Enrichment between 15- and 25-fold of β-galactosidase activity was routinely achieved for vesicle preparations (results not shown). In addition, β-galactosidase latency [31] was greater than 70%, as determined in the presence and absence of detergent (results not shown). Electron microscopy of the preparations revealed a vesicle population that was essentially free of mitochondria (<5%) and other non-vesicular components (Figure 1A). Analysis of the numerous electron-dense spots (Figure 1A, arrows) surrounding the isolated vesicles by EDS revealed that they were composed of iron (Figure 1A, inset), consistent with their identity as the iron oxide particles used to isolate these vesicles.

Figure 1. Characterization of purified late endosomal vesicles.

(A) Electron micrograph of a typical vesicle preparation showing purified endocytic vesicles; arrows indicate particles composed of colloidal iron. Inset, elemental composition of electron-dense spots determined by EDS. The copper peaks result from the copper grids on which the specimen was mounted. Scale bar, 0.5 μm. (B) Vesicles isolated at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 h after particle injection were analysed for marker proteins associated with specific vesicle populations: Rab5 for early endosomes, Rab7 for late endosomes, α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase (α-GalNAcase) for late endosomes/lysosomes. Vesicles isolated at 1, 2 and 4 h after particle injection were enriched for early endosomal, late endosomal and E/L markers respectively. (C) The functional integrity of purified vesicles was routinely determined by an AO fluorescence-quenching assay as described in the Materials and methods section. Addition of ATP initiates vesicle acidification via the action of the proton ATPase-driven quenching of AO fluorescence. This effect is reversed by the addition of the proton ionophore nigericin. (D) Crude PMS and purified late endosomes (Ves) from Wt mice were characterized for their content of non-late endosomal proteins: early endosomes (Rab5), TGN (TGN38), endoplasmic reticulum (calregulin) and mitochondria (SOD). (E) Purified vesicles from Wt and NPC1 mice contain equivalent levels of late endosomal marker proteins, indicating similar uptake and endocytosis kinetics in Wt and NPC1 mouse livers. Furthermore, vesicles isolated from Wt mice contained significant amounts of NPC1 protein, indicating that these vesicles are NPC1-containing late endosomes.

Since SPD particles have been shown to migrate through the E/L system in a time-dependent manner [23], we hypothesized that different components of this system could be enriched and isolated by varying the timing of tissue isolation following particle injection. Thus livers were harvested at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 h post-injection to determine whether late endosomes could be specifically isolated for our studies of NPC disease. After vesicle isolation, preparations were analysed for marker proteins associated with specific compartments of the E/L system. Association of the small GTPase Rab5, an early endosomal marker, was maximal between 0.5 and 1 h post-injection (Figure 1B; Rab5), suggesting, as expected, that the early time-point preparations were enriched for early endosomes. Similarly, maximal association of the late endosomal marker Rab7 was seen with vesicles isolated at 2 h post-injection (Figure 1B; Rab7). The enzyme α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase, a late endosomal/lysosomal marker, showed maximal association with vesicles isolated at 4 h (Figure 1B; α-GalNAcase). Taken together, these results indicate that the preparations can be enriched for specific vesicle populations by controlling the time of tissue harvest following particle injection. For all subsequent studies using late endosomes, livers were harvested and processed at 2 h after particle injection.

Critical to the functional characterization of any vesicular population is the preservation of its functional integrity, therefore purified late endosomes were routinely analysed by an AO fluorescence-quenching assay [25]. Briefly, AO freely diffuses into intact vesicles, where its intrinsic fluorescence is quenched as vesicles are acidified via the action of the v-type proton ATPase on the vesicular limiting membrane. Thus decreased AO fluorescence correlates with the vesicles' ability to acidify and thus their preserved structural and functional integrity. As shown in Figure 1(C), purified late endosomes quenched AO fluorescence upon addition of ATP to initiate proton pumping (Figure 1C; ATP). Furthermore, addition of the ionophore nigericin abolished the quenching of the dye (Figure 1C; Nigericin), a result that was also obtained by treating vesicles with the proton-pump-specific inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (results not shown). These results indicate that vesicles isolated by magnetic chromatography are structurally intact and possess functional proton pumps on their membranes.

Analysis of the vesicle preparations by electron microscopy suggested that the vesicle population was heterogeneous (Figure 1A). To confirm that this heterogeneity was due to the presence of a mixed population of late endocytic vesicles and not due to contamination by other organelles, an equal volume of the crude PMS and purified Wt vesicle fractions were analysed for the presence of marker proteins of various organelles. The early endosomal GTPase Rab5, the integral TGN membrane protein TGN38, the endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum protein calregulin and the mitochondrial Mn-SOD were evident in the crude PMS (Figure 1D; PMS), but were not detectable in the purified vesicle fractions (Figure 1D; Ves), indicating that these preparations did not contain appreciable amounts of contaminating organelles.

Since NPC disease is characterized by a defect in retrograde transport from the late endosome [32,33], it was important to confirm that the endosomal populations being isolated from Wt and NPC1 mice at 2 h post-injection of the SPD particles were comparable. Studies have shown that the uptake of both sucrose and LDL into cells lacking NPC1 occurs at the same rate as in Wt cells [6,33], suggesting similar kinetics of endocytosis in Wt and NPC1 cells. Thus Wt and NPC1 late endocytic vesicles were analysed for the association of late endosomal marker proteins. Levels of the E/L membrane protein Lamp1 were comparable in purified Wt and NPC1 vesicles (Figure 1E), as were the small GTPase Rab9 and the late-endosomal StART-domain containing protein MLN64 [34], suggesting that the Wt and NPC1 vesicles isolated in this manner are biochemically equivalent. Furthermore, isolated Wt late endosomes were shown to contain a significant amount of NPC1 protein (Figure 1E; NPC1), whereas, as expected [26], no signal was detected in isolated NPC1 late endosomes (results not shown).

Lipid profiles of purified Wt and NPC1 late endosomes

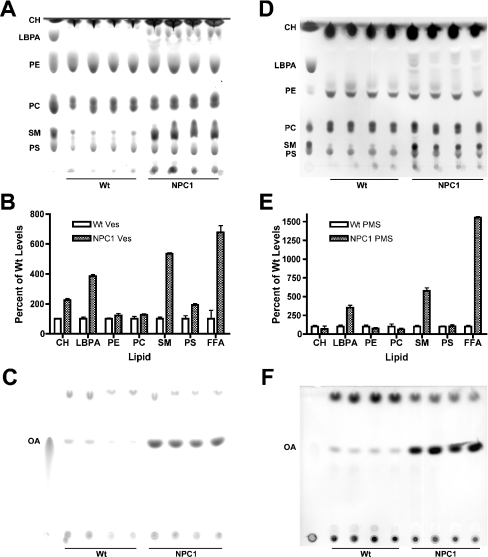

Since the biochemical hallmark of NPC disease is cholesterol accumulation in the E/L system, late endosomes from Wt and NPC1 mice were purified as described above to determine the lipid profile of these organelles. Lipids extracted from these endosomes were subjected to TLC to ascertain any lipid differences between the two populations. Four independent Wt and NPC1 vesicle preparations were used for each analysis and each TLC was performed at least twice to eliminate any technical and/or separation variability. Previous studies have shown that, in addition to cholesterol, NPC1 mice exhibit elevated levels of SM (sphingomyelin) and gangliosides [16–18] and, indeed, NPC1 late endosomes contained an approx. 6-fold higher level of SM and a greater than 2-fold higher level of cholesterol than Wt late endosomes (Figures 2A and 2B; SM, CH). NPC1 late endosomes also had an approx. 4-fold higher level of LBPA (lysobisphosphatidic acid) (Figures 2A and 2B; LBPA), a lipid that has been reported to be specifically localized to the internal membranes of multivesicular bodies [35]. This observed increase in LBPA levels is in agreement with reports of elevated LBPA levels in the livers and spleens of NPC1 patients [36]. There were no significant differences in the levels of the membrane phospholipids PE (phosphatidylethanolamine) and PC (phosphatidylcholine) (Figures 2A and 2B; PE, PC), but PS (phosphatidylserine) levels were slightly elevated (approx. 2-fold) in NPC1 vesicles (Figures 2A and 2B; PS), suggesting that membrane organization and structure is altered in NPC1 endosomes. Moreover, not only were PS levels increased in NPC1 vesicles, but also NEFA levels were strikingly elevated. The approx. 7-fold increase in NEFA levels in NPC1 vesicles compared with Wt vesicles (Figures 2B; FFA, and 2C; OA) was the largest increase seen for the lipids analysed and thus lends support to the notion that NPC1 plays a role in fatty acid mobilization [10,37]. Taken together, these results indicate that the lipid composition of Wt and NPC1 late endosomes is distinct. However, whether these differences contribute to or are a secondary effect of NPC dysfunction is currently under investigation.

Figure 2. Analysis of the lipid composition of Wt and NPC1 purified late endosomes.

(A) Comparison of the phospholipid composition of Wt and NPC1 late endosomes. An amount of lipid equivalent to 100 μg of protein was extracted from four independent Wt and NPC1 vesicle preparations and analysed by TLC using chloroform/methanol/30% ammonia (65:35:5, by vol.) as a solvent system. Lipids were visualized by charring after spraying with cupric phosphate and identified using standards as denoted. CH, cholesterol. (B) The TLC plates from (A) and (C) were scanned, and the spot intensity for each lipid was quantified using the ImageJ program. The amount of each lipid in NPC1 endosomes was expressed as a percentage of the amount of the corresponding lipid in Wt endosomes, which was arbitrarily set at 100%. (C) Comparison of the NEFA composition of Wt and NPC1 late endosomes. Lipids were extracted as in (A) and were separated by TLC using cyclohexane/ethyl ethanoate (3:2, v/v) as a solvent system. Lipids were visualized by charring after spraying with cupric phosphate and identified as above. (D) Phospholipid composition of Wt and NPC1 crude PMS. An amount of lipid equivalent to 50 μg of protein was extracted, separated and visualized as in (A). (E), The TLC plates from (D) and (F) were scanned, and spots were quantified and expressed as above. (F) Comparison of the NEFA composition of Wt and NPC1 crude PMS. An amount of lipid equivalent to 50 μg of protein was extracted, separated and visualized as in (C). FFA, NEFA; OA, oleic acid; Ves, vesicle.

To determine whether these lipid differences reflect changes that are confined to the late endosome or whether they reflect global cellular changes, lipid profiles of Wt and NPC1 crude PMS were analysed. The differences in lipid composition between the Wt and NPC1 PMS were very similar to those seen in the purified vesicles (Figures 2B and 2E), suggesting that these lipid changes are mainly a consequence of changes within the late endosome. However, SM levels were increased approx. 9-fold in the NPC1 PMS (Figures 2D and 2E; SM), compared with approx. 6-fold in the NPC1 vesicles (Figures 2A and 2B; SM), suggesting that SM accumulation was not restricted to the late endosome, but also occurred in other membrane domains within the cell. Interestingly, the increase in PS levels seen in NPC1 vesicles (Figures 2A and 2B; PS) was not recapitulated to the same extent in NPC1 PMS (Figures 2D and 2E; PS). However, the approx. 7-fold increase in NEFA levels seen in NPC1 vesicles (Figures 2B; FFA, and 2C; OA) was also observed in NPC1 PMS, which exhibited an approx. 14-fold increase in NEFA levels (Figures 2E; FFA, and 2F; OA). The greater increase in NEFA levels in the NPC1 PMS compared with that of NPC1 vesicles indicates that the NEFA increase in the NPC1 mice is a widespread phenomenon throughout NPC1 cells.

Cholesterol and NEFA levels were also quantified using a diagnostic kit to confirm further these lipid differences between Wt and NPC1 vesicles. NPC1 vesicles exhibited an approx. 1.5-fold increase in cholesterol levels compared with Wt vesicles (Figure 3A; CH), which is slightly less than the increase determined by TLC (Figure 2B; CH). However, the increase in cholesterol levels in the PMS of NPC1 mice was approx. 2.5-fold higher than Wt PMS levels by this method (Figure 3B; CH), in exact agreement with the increase seen by TLC (Figure 2E; CH). Furthermore, the levels of NEFAs in NPC1 vesicles were found to be approx. 8.5-fold higher than those of Wt vesicles (Figure 3A; FFA), in agreement with the increase determined by TLC (Figure 2B; FFA). Quantification of the NEFA levels in the PMS of Wt and NPC1 mice could not be carried out by this method.

Figure 3. Cholesterol and NEFA accumulation in Wt and NPC1 late endosomes and fibroblasts.

(A) The amount of cholesterol (CH) and NEFAs (FFA) in Wt and NPC1 endosomes was determined as described in the Materials and methods section. Cholesterol and NEFA levels in NPC1 endosomes were expressed as percentages of the amount in Wt endosomes, which was arbitrarily set at 100%. Values represent the average levels found in four independent preparations. (B) The amount of cholesterol (CH) in Wt and NPC1 crude PMS was quantified as described in the Materials and methods section. Values are expressed as above and represent the mean of four independent preparations. (C) Analysis of NEFA levels in Wt, NPC1-null and NPC1-I1061T human fibroblasts. An amount of lipid equivalent to 50 μg of cellular protein was extracted, separated by TLC and visualized as described in Figure 2. Wt1, GM5387 cells; Wt2, GM41B cells; Null, DMN98.16 cells; I1061T, GM3123 cells. (D) Analysis of cholesterol and NEFA levels in vesicles isolated from Wt, heterozygous (Het) and NPC1 mice. The amount of cholesterol in vesicles was determined using a diagnostic kit as described in the Materials and methods section. For NEFA analysis, an amount of lipid equivalent to 25 μg of vesicular protein was extracted, separated by TLC, visualized and quantified as described in Figure 2. Cholesterol and NEFA levels were expressed as percentages of the amount in Wt endosomes, which was arbitrarily set at 100%. Values represent the average levels found in three independent preparations from different mice.

While this work was being completed, a study appeared reporting that no accumulation of NEFAs could be observed in NPC1 human fibroblasts compared with Wt human fibroblasts [38]. However, the GM3123 NPC1 fibroblasts used in that study are heteroallelic for the most common mutation, I1061T [39], and carry a polymorphism in their second allele that has been determined to be benign [15]. The presence of the I1061T mutation is associated with a wide range of clinical phenotypes, from neurological juvenile onset to non-neuronopathic adult form [40], which may reflect the nature of the second allele mutation and interplay of the two mutant NPC1 proteins in the cell. Furthermore, I1061T fibroblasts have been shown to express a significant amount of vesicle-localized NPC1 protein, as determined both by Western blot and immunofluorescence studies [33,40], suggesting that it may not be an ideal model with which to study NPC1 function. To address this conflicting result and to determine if NPC1 protein expression correlates with NEFA accumulation in human fibroblasts, lipids from Wt and NPC1 fibroblasts were extracted and subjected to TLC analyses and quantification. The GM3123 NPC1 cell line contains slightly fewer NEFAs (Figure 3C; I1061T) than the two Wt cell lines, which contain variable amounts of NEFAs (Figure 3C; Wt1 and Wt2). However, the NPC1-null cell line contains strikingly higher levels (approx. 6-fold) of NEFAs than either the Wt or GM3123 cell lines (Figure 3C; Null, and results not shown), suggesting that NEFAs accumulate when no NPC1 protein is present. Further analysis showed no significant difference in cholesterol accumulation between the GM3123 and the NPC1-null cell lines; both cell lines contained approx. 2-fold higher levels of cholesterol than Wt fibroblasts (results not shown), which is consistent with a previously published report [41].

Cholesterol and NEFA accumulation was also determined for vesicles isolated from heterozygous NPC1 mice. Three independent vesicle preparations (from different mice) were used for each determination. Vesicles isolated from heterozygous mice exhibited cholesterol levels that were intermediate between vesicles from Wt and NPC1 mice (Figure 3D; Cholesterol). NEFA levels in vesicles from heterozygous mice were also elevated (approx. 1.5-fold) compared with Wt vesicles, but did not approach the levels seen in vesicles from NPC1 mice (Figure 3D; FFA).

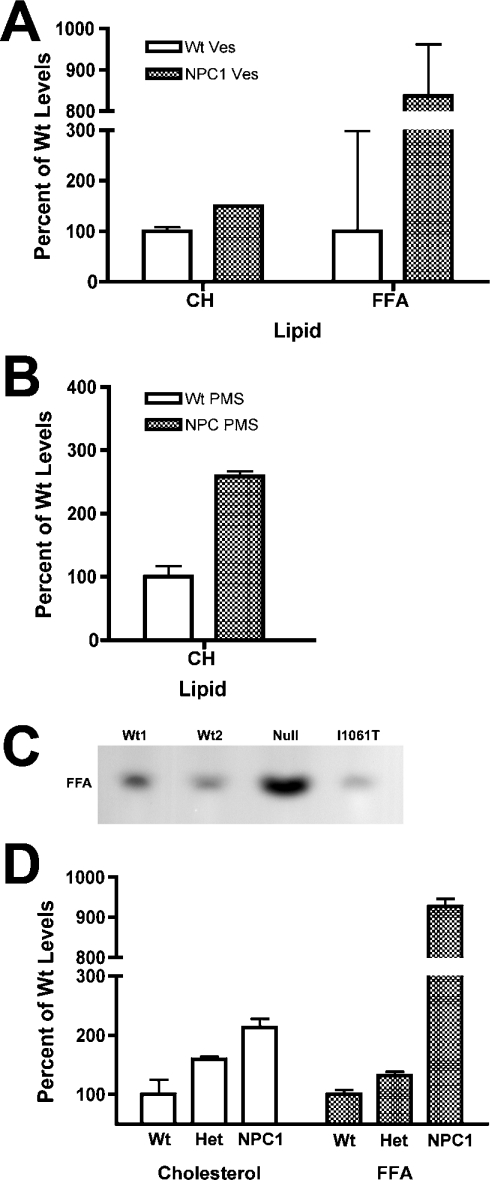

Rab7, but not Rab9, exhibits altered association with Wt and NPC1 late endosomes

Since NPC1 cells have been shown to have a transport block between late endosomes and the TGN, Wt and NPC1 vesicles were analysed for association of proteins known to play a role in late endosomal transport. Two Rab GTPases are important for transport at the late endosome: Rab9, which mediates movement between the late endosome and TGN, and Rab7, which mediates movement between the late endosome and lysosome. These Rab proteins cycle between an active membrane-bound form and an inactive cytosolic form. We have shown recently that increased expression of Rab9, but not Rab7, in NPC1 cells leads to a correction of the cholesterol storage phenotype [42]. However, late endosomes from Wt and NPC1 mice showed no difference in Rab9 association (Figure 4A; Rab9). In contrast, NPC1 late endosomes showed a 3-fold increase in Rab7 association compared with Wt vesicles (Figure 4A; Rab7), suggesting that the association–dissociation equilibrium of Rab7 with NPC1 late endosomes is disturbed. Solubilization of these vesicles with Triton X-114 showed that the majority of Rab7 was associated with the detergent fraction (results not shown), confirming that the protein is membrane-associated. These results are consistent with a previous report suggesting that the excess cholesterol in NPC1 vesicles prevents Rab7 dissociation, which may in turn inhibit NPC1 vesicle motility [43]. These data confirm that the purified vesicles provide a good model for characterizing both endosomal lipid and protein changes caused by the lack of NPC1 activity.

Figure 4. Analysis of proteins associated with Wt and NPC1 purified late endosomes.

(A) Association of Rab7, but not Rab9, is altered in NPC1 endosomes. Protein (5 μg) from Wt and NPC1 endosomes was subjected to electrophoresis and Western blotting against Rab7 and Rab9. Following quantification, the amount of Rab7 in NPC1 late endosomes was found to be approx. 3-fold higher than the amount found in Wt late endosomes. (B) Microheterogeneity of NPC2 in NPC1 vesicles is due to variations in N-linked oligosaccharides. Protein (10 μg) from Wt and NPC1 vesicles was incubated with (+) or without (−) PNGase F and then subjected to electrophoresis and Western blotting against NPC2. (C) Processing of soluble lysosomal enzymes is normal in NPC1 vesicles. Protein (10 μg) from Wt and NPC1 vesicles was subjected to electrophoresis and Western blotting against α-galactosidase A and α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase. (D) NPC2 protein destined for the secretory pathway in NPC1 mice does not show the same altered processing as the endosome-associated NPC2 protein. Cells derived from Wt and NPC1 mice were cultured for 3 days in serum-free medium, after which an amount of medium equivalent to 3 μg of total cellular protein was subjected to electrophoresis and Western blotting against NPC2. The secreted NPC2 protein in the medium (secreted) from Wt and NPC1 cells was identical, in contrast with the cellular NPC2 (cells) detected in 10 μg of cell lysate.

NPC1 late endosomes contain an aberrant form of NPC2

It is well established that deficiency of either NPC1 or NPC2 protein leads to a nearly identical phenotype, despite the dissimilarity of the two proteins, and this observation has led to suggestions that the two proteins might somehow directly interact [5]. Alternatively, we hypothesized that a lack of NPC1 activity affects the function of NPC2. To gain insight into this process and to determine if NPC2 expression is affected by a lack of NPC1 activity, we investigated the expression and association of the NPC2 protein with NPC1 vesicles. NPC2 expression levels have previously been reported to be elevated in human NPC1 fibroblasts; however, that study examined total cellular NPC2 levels rather than NPC2 specifically associated with vesicles [15]. Late endosomes from Wt and NPC1 mice showed no significant difference in their NPC2 content, but, intriguingly, the NPC2 protein in NPC1 vesicles was always detected as a broad band of slightly higher molecular mass than the two sharp bands detected in Wt vesicles (Figure 4B; Wt and NPC1, −PNGase F). Normally, NPC2 is detectable as a distinct doublet representing the two differentially glycosylated isoforms of the protein [44], but the broad diffuse band detected in NPC1 vesicles suggests that, in NPC1 vesicles, NPC2 exhibits increased microheterogeneity.

Since NPC2 is a small soluble E/L glycoprotein that traffics via the M6P (mannose 6-phosphate) receptor [5], this microheterogeneity suggested that endosomal processing of NPC2 might be altered in NPC1 mice. To determine whether the increased NPC2 heterogeneity reflects differences in post-translational processing, proteins extracted from Wt and NPC1 vesicles were subjected to glycosidase digestion to remove N-linked oligosaccharides. Deglycosylated NPC2 from Wt and NPC1 endosomes exhibited an identical molecular mass banding pattern (Figure 4B; Wt and NPC1, +PNGase F), confirming that the different NPC2 banding patterns in the undigested vesicles result from variations in their N-linked oligosaccharides.

Proteins destined for the E/L system acquire complex glycosylation in the Golgi complex and TGN, and then the process is reversed as they arrive at the E/L compartment and oligosaccharide trimming is initiated. Thus the oligosaccharide profile of NPC2 in NPC1 endosomes may be altered because the protein is retarded in the TGN and does not reach the E/L system. This scenario is unlikely since we detected slightly greater amounts of NPC2 protein associated with NPC1 late endosomes (approx. 1.5 times) than with Wt late endosomes (Figure 4B; Wt and NPC1, −PNGase F). Alternatively, the altered NPC2 processing in NPC1 endosomes may reflect widespread protein trafficking/processing defects in NPC1 cells. To date, there have been only a handful of conflicting reports about altered protein trafficking in NPC1 cells. The most studied protein has been the cation-independent M6P receptor, which has been reported to accumulate in LBPA-rich late endosomal compartments in NPC1 fibroblasts [45]. Such localization would be expected to affect the trafficking of all proteins that use the receptor for delivery to the lysosome. However, normal movement and activity of the M6P receptor and other soluble lysosomal enzymes have been observed in NPC1 disease cells [46]. To determine whether there is a global defect in protein processing/trafficking in NPC1 mice, Wt and NPC1 vesicles were analysed for expression of other soluble lysosomal proteins. Western blot analysis of the E/L enzymes α-galactosidase A and α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase revealed no differences in either their expression levels or protein species (Figure 4C), indicating that the lysosomal protein trafficking/processing machinery is functional in NPC1 cells. To address the possibility that alterations in ER and/or Golgi processing were responsible for the observed NPC2 glycosylation patterns, cell lines derived from Wt and NPC1 mouse livers were analysed for NPC2 protein secretion. The NPC2 protein secreted from both cell lines was identical (Figure 4D; Secreted), in sharp contrast with the cellular form of NPC2 (Figure 4D; Cells), which exhibited the same glycoform differences as those seen in intact vesicles (Figure 4B). These results indicate that the secretory pathway functions normally in NPC1 cells and supports further the notion that the mechanism that gives rise to the different forms of NPC2 in NPC1 vesicles is specific to both the NPC1 vesicles and the NPC2 protein.

NPC2 solubility and localization are altered in NPC1 mice

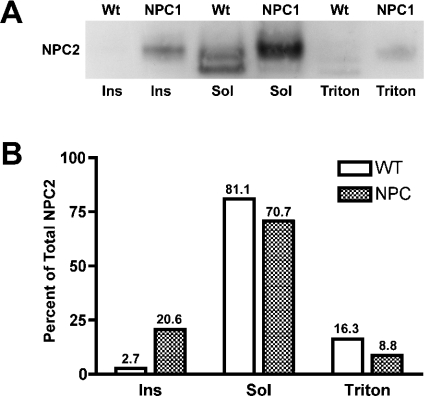

The NPC2 studies described above were performed under conditions that are suitable for soluble proteins. Since global protein glycosylation/deglycosylation appears to be normal in NPC1 mice, another explanation for incomplete NPC2 deglycosylation is that NPC2 is located in a region that is inaccessible to exoglycosidases. To test this hypothesis, vesicles were partitioned into Triton-X-114-soluble, -insoluble and -detergent fractions [28,47] and analysed for their NPC2 content. As expected, the majority of NPC2 protein in Wt vesicles is soluble (Figure 5; Wt Sol), with almost none (<3%) detected in the insoluble fraction (Figure 5; Wt Ins) and a small amount (approx. 16%) detected in the detergent fraction (Figure 5; Wt Triton). The detergent-associated NPC2 protein may be destined for degradation, since proteins in the late endosome are internalized into interior membrane domains en route to the lysosome for degradation [48]. Alternatively, NPC2 may associate transiently with membranes as part of its yet undefined function. In contrast, in NPC1 vesicles, a smaller percentage (approx. 9%) of NPC2 protein partitioned to the detergent fraction (Figure 5; NPC1 Triton), while >20% partitioned to the insoluble fraction (Figure 5; NPC1 Ins), suggesting that, in the disease endosomes, a significant proportion of NPC2 protein may be associated with insoluble membrane microdomains and is no longer completely soluble.

Figure 5. Detergent solubilization of NPC2 protein associated with Wt and NPC1 late endosomes.

(A) Wt and NPC1 vesicles (10 μg) were pelleted and solubilized for 16 h with Triton X-114. Insoluble material (Ins) was pelleted by centrifugation. The supernatant was layered on top of a sucrose cushion and centrifuged. The detergent droplet (Triton) at the bottom of the tube containing integral membrane and membrane-associated proteins was separated from the rest of the soluble (Sol) fraction. All fractions were freeze-dried before being subjected to electrophoresis and Western blotting against NPC2. (B) Bands from (A) were quantified using the ImageJ program, and the amount in each lane was expressed as a percentage of the total amount of NPC2 protein in Wt or NPC1 vesicles.

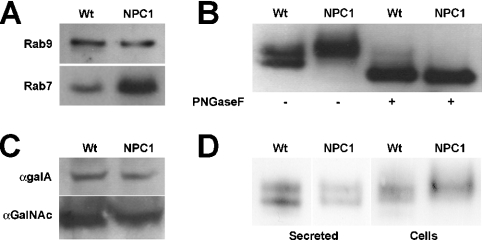

NPC2 associates with internal membranes in late endosomes

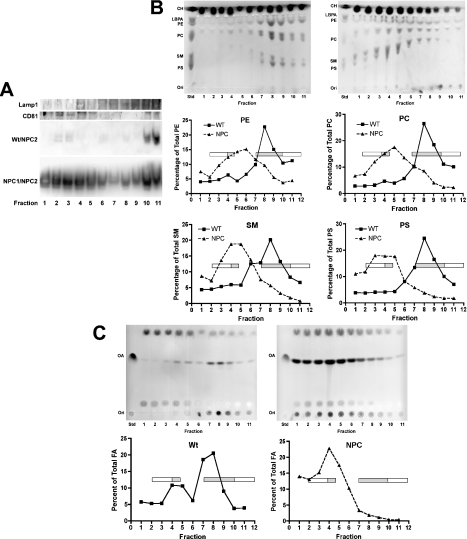

Late endosomes are complex structures comprising both limiting and internal membranes that can be distinguished by their associated proteins and lipids [30]. The observation that a small proportion of NPC2 partitions with detergent-soluble membranes in Wt vesicles (Figure 5; Wt Triton) suggests that the protein might associate transiently with these membranes as part of its function. Knowledge of whether NPC2 preferentially associates with either limiting or internal endosomal membranes might provide better insight into its function, since the two domains perform different functions [49]. Thus late endosomal membranes were centrifuged through a sucrose gradient as described previously to separate the various membrane domains [30]. To discriminate between fractions enriched in limiting or internal membranes, fractions were analysed for association of Lamp1, which localizes mainly to the limiting membrane but is also found in internal membranes, and CD81, a tetraspanin membrane protein found almost exclusively on internal membranes [49]. Subfractionation of Wt membranes showed Lamp1 association mainly with fractions 4 and 7–11 (Figure 6A; Lamp1), whereas CD81 associated mainly with fractions 2–4 and 10–11 (Figure 6A; CD81). NPC1 membranes showed some alteration in their fractionation profiles for these proteins compared with Wt membranes (results not shown); this result is most likely due to changes in the lipid composition and thus membrane dynamics of the NPC1 vesicles, as described below. Analysis of membrane-associated NPC2 distribution in Wt vesicles revealed that the bulk of the protein was found in fractions 2–4 and 10–11 (Figure 6A; Wt/NPC2), indicating that NPC2 co-localizes with CD81 and thus associates primarily with internal membranes. This association is probably transient, since >80% of NPC2 in Wt vesicles is soluble (Figure 5; Wt Sol). The difference in NPC2 membrane association between Wt and NPC1 vesicles was apparent in the analysis of NPC2 distribution in fractionated NPC1 vesicular membranes. A much higher amount of NPC2 protein was found associated with NPC1 membranes and, although the protein appeared in all fractions, the greatest amounts were detected, similarly to the Wt membrane preparations, in the fractions corresponding to internal membranes (Figure 6A; NPC1/NPC2). The ‘spill over’ of NPC2 into all fractions might reflect the altered membrane dynamics in disease vesicles and may contribute to the ‘dysfunction’ of NPC1 membranes.

Figure 6. Characterization of membrane domains in Wt and NPC1 late endosomes.

Membranes from Wt and NPC1 vesicles (4 mg) were subjected to sucrose density gradient centrifugation to separate membrane domains. (A) Wt membrane fractions were precipitated and analysed for association of the limiting membrane marker Lamp1 and the internal membrane marker CD81. Wt and NPC1 fractions were also analysed for association of NPC2 as indicated. (B) Lipid content of Wt and NPC1 membrane fractions. Top panels, Wt (left-hand panel) and NPC1 (right-hand panel) membrane fractions from (A) above were analysed by TLC for phospholipid content. Marker standards are indicated. Middle and bottom panels, plates were scanned, and lipids were quantified. Each graph represents the indicated phospholipid; the amount of each phospholipid in each fraction was expressed as a percentage of the total amount of that phospholipid in all fractions. Open and solid bars denote limiting membranes and internal membranes respectively. (C) NEFA content of Wt and NPC1 membrane fractions. Top panels, Wt (left-hand panel) and NPC1 (right-hand panel) membrane fractions were analysed by TLC for NEFA content. Bottom panels, plates were scanned, and NEFAs were quantified. The amount of NEFAs in each fraction was expressed as a percentage of the total amount of NEFAs in all fractions. Open and solid bars denote limiting membranes and internal membranes respectively. Std, standard; Ori, origin; CH, cholesterol; OA, oleic acid.

To gain a clearer understanding of membrane dynamics in NPC1 vesicles, TLC analyses of the lipid composition of the membrane fractions from Wt and NPC1 vesicles were carried out. The lipid profiles of Wt and NPC1 membrane fractions were dissimilar; in Wt vesicles, phospholipids concentrated in fractions 8 and 9, whereas, in NPC1 vesicles, they were distributed throughout all fractions, but were concentrated in fractions 4–5 (Figure 6B, top panels). The increased amounts of phospholipids seen in whole NPC1 vesicles (Figures 2A and 2B), as well as in these membrane fractions, suggests that NPC1 vesicles may contain more membrane than Wt vesicles, which is not surprising in light of NPC1's potential role in lipid transport. Furthermore, the phospholipid composition of each fraction was altered in NPC1 vesicles (Figure 6B, bottom panels).

Moreover, the distribution of NEFA was also dramatically altered in NPC1 vesicle fractions. As shown in Figure 6(C), most of the NEFA in Wt vesicles localized to fractions 7 and 8, with a small amount in fractions 4 and 5. Not only did NPC1 vesicles contain more NEFA (approx. 7 times more; Figures 2B and 2C), but also the bulk was localized to one peak in fractions 3–5. Taken together, these results suggest that NPC1 late endosomal membranes are structurally different from Wt vesicular membranes. These alterations appear to be the direct result of excess accumulated lipids, including cholesterol, phospholipids and NEFAs, in these organelles. This imbalance in turn causes a dramatic change in the architecture of the internal endosomal membranes, with devastating results as exemplified by the cellular phenotype of NPC disease.

DISCUSSION

The method described in the present paper for the specific isolation of late endosomes from small animals such as mice should be of great utility in the study of small animal models of E/L system disorders. The plethora and availability of mouse models of E/L storage disorders [50] makes this approach extremely powerful and of great utility. The method is simple and rapid, and provides large quantities of intact vesicles that can be used for cellular biochemical, proteomic or lipidomic characterization. A similar technique has been used to isolate lysosomes from tissue culture cells derived from patients with lysosomal storage disorders [51], albeit with very low recovery of intact vesicles, precluding any routine biochemical or proteomic analyses. We routinely isolate milligram quantities of vesicles from mouse liver, of which >70% are intact and functional, as assessed by enzymatic and in vitro acidification assays. To validate this method, we have confirmed biochemically using purified late endosomes that the small GTPase Rab7 is associated with NPC1 endosomes at high levels compared with Wt endosomes. These results had been reported previously using a cell culture system; it has been suggested that the membrane association of Rab7 in NPC1 endosomes is caused by cholesterol accumulation, and this strong association may in turn interfere with vesicle motility [43].

Information about the differences in the protein and lipid content or composition of late endosomes from Wt and NPC1 mice might provide insight into NPC1 function and its role in NPC disease pathogenesis. That the lipid profiles of NPC1 vesicles were significantly different from Wt vesicles is not surprising. Although NPC1 is a lipidosis whose ‘primary’ storage molecule has historically been viewed as cholesterol, NPC1 mice have also been shown to store a host of other lipids, including SM, gangliosides and glycosphingolipids [16–18]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of elevated levels of membrane phospholipids such as PS and NEFA in NPC1 late endosomes. These results suggest that membrane topology and organization is altered in NPC1 vesicles, which could have pleiotropic effects on cellular transport and signalling cascades. This notion of altered or ‘scrambled’ NPC1 late endosomal membranes is supported by our findings that most of the lipid changes detected in the NPC1 PMS are recapitulated in purified NPC1 vesicles, indicating that these changes are vesicle-specific, rather than global changes at the cellular level. Two notable exceptions were SM and NEFA, which showed a greater difference in the NPC1 PMS compared with the NPC1 vesicles, suggesting that SM and NEFA accumulation in NPC1 cells may extend to cellular membranes beyond the late endosome. Interestingly, the almost 7-fold increase in NEFA levels was the most striking lipid difference between Wt and NPC1 late endosomes and was significantly larger than the increase seen in cholesterol, the ‘classic’ marker for NPC disease. These results lend support to the notion that NPC1 may play an important role in fatty acid metabolism or transport as we have suggested previously [10]. In fact, in support of our conclusions, a recent study has shown that the exit of NEFAs from NPC1 late endosomes is retarded [37].

An important question that remains unanswered in the NPC field is the similarity of the cellular and disease phenotypes between the two NPC complementation groups, NPC1 and NPC2. As discussed above, the two proteins are quite different and share no structural homologies. Since no evidence for an interaction between the two proteins is currently available, we hypothesized that the lack of functional NPC1 protein also affects the function of NPC2. In such a scenario, the phenotype of NPC1 and NPC2 disease would be mostly attributable to a dysfunction of NPC2. We thus utilized our system to provide evidence for this hypothesis by characterizing the NPC2 protein in NPC1 vesicles. Although it has been reported previously that NPC1 patient fibroblasts have elevated levels of NPC2 protein [15], we found comparable protein levels associated with Wt and NPC1 late endosomes from mouse livers. These may reflect species differences or tissue-type differences, as has been seen with lysosomal enzyme activity from different tissues in NPC1 patients [52]. We noted, however, that N-linked glycosylation of NPC2 in Wt and NPC1 late endosomes was different, a fact that could be explained by several scenarios: (i) a global defect in E/L glycosidase function; (ii) a defect in M6P-receptor-dependent trafficking of proteins to the E/L system; or (iii) an NPC2-specific mechanism that renders the protein somehow resistant to E/L processing.

The first and second possibilities were experimentally discounted because other soluble lysosomal proteins were processed identically and found at comparable levels in both Wt and NPC1 endosomes. Nevertheless, there has been some controversy surrounding the trafficking of the cation-independent M6P receptor from the TGN in NPC1 cells. It has been suggested that the receptor localizes exclusively to the TGN and not the late endosome in both Wt and NPC1 fibroblasts [46], and this localization explains why most lysosomal enzymes that depend on correct M6P receptor recycling have normal activity in NPC1 fibroblasts. However, another study has shown that the M6P receptor is trapped in late endosomal compartments in NPC1 cells [45]. Our results suggest that M6P-receptor-dependent trafficking of soluble lysosomal proteins, as well as glycosidic processing, are normal in NPC1 mouse endosomes. Furthermore, analysis of secreted NPC2 protein from Wt and NPC1 mouse cells indicates that processing and transport through the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi complex and secretion are also normal in NPC1 mice.

The third scenario to explain altered NPC2 processing in NPC1 endosomes suggests that a mechanism specific to the NPC2 protein renders the protein resistant to processing by glycosidic enzymes. One means by which this could occur is sequestration in a subendosomal location that is inaccessible to those enzymes. NPC2 protein has been shown to traffic with NPC1 in late endosomal tubules on its way to lysosomes in Wt fibroblasts [16]. In NPC1 patient fibroblasts, NPC2 has been localized mainly to cholesterol-loaded late endocytic compartments [15], such as the vesicles that we isolated in the present study. Although it has been suggested that the concentration of NPC2 in late endocytic vesicles may be due to defective recycling of the M6P receptor [16], our data argue against this hypothesis, since soluble lysosomal proteins are targeted and processed correctly.

Since the exact function of NPC2 remains unclear, it is difficult to assess the full ramifications of its association with an insoluble fraction of late endocytic vesicles. This fraction may represent NPC2 protein that is interacting with transmembrane proteins or associated with membrane microdomains, as is the case with the lipid-binding protein annexin 2 [53]. NPC2 was first isolated as a secreted protein [54] and can bind to cholesterol in serum [12]. It has also been observed that, as cholesterol is mobilized from lysosomes, the expression of vesicular NPC2 diminishes [16], suggesting that NPC2 may travel with cholesterol through the cell and perhaps even be secreted with it. If NPC2 does in fact travel with cholesterol, the massive accumulation of cholesterol in the E/L system would explain why only NPC2 and not other M6P-receptor-dependent proteins are trapped in NPC1 late endocytic vesicles. However, some evidence arguing against this ‘co-secretion’ mechanism has been presented in a recent report demonstrating that the majority of sterols secreted from astrocytes are not released together with NPC2 [55]. Furthermore, the study showed that the secretion of both NPC2 and cholesterol from NPC1 astrocytes was normal, which is consistent with our data showing that the NPC2 protein secreted from NPC1 mouse cells is identical with that secreted from Wt mouse cell, even though their cellular forms differ.

Our studies suggest that, although most cellular NPC2 is soluble under Wt conditions, some protein does associate transiently with late endosomal internal membranes. Given the proposed cholesterol-transport function of NPC2, this localization is consistent with observations that the bulk of cholesterol in the endocytic pathway is located in internal membranes [56,57]. However, in NPC1 vesicles, much more NPC2 is found associated with membranes and, in particular, the internal membrane fractions. Late endosomal internal membranes are heterogeneous structures with varied lipid and protein compositions [30]. In fact, the differences observed in the lipid and protein profiles of late endosomal subfractions of mouse vesicles compared with those published in an earlier study [30] may be due to the differences between in vitro and in vivo models, since cultured cell models have a much higher proliferative capacity than animal liver, and phospholipid turnover is regulated in part by cell cycle status [58]. It may be that, in NPC1 mice, increased lipid content in vesicles causes an accumulation of membranes that leads to the formation of multilamellar vesicles similar to those seen in class E mutants [59]. Indeed, multilamellar storage vesicles are observed in NPC patient fibroblasts and in normal fibroblasts treated with drugs that mimic the NPC cellular lesion [60,61]. It has been demonstrated that, at least in yeast, these multilamellar vesicles prevent the processing of specific enzymes [62]. It is also conceivable that the lipid accumulation in NPC1 vesicles results in increased raft formation, which might interfere with normal endosome function.

The conundrum surrounding the mechanism by which two very different proteins can cause an almost identical phenotype in NPC disease has been a puzzle since the gene responsible for the second complementation group was discovered. Both proteins have been implicated in lipid metabolism in the E/L system and it was originally thought that the two proteins must somehow interact [15,16]. To date, however, there is no evidence of this interaction. Our observations that NPC2 exhibits altered glycolytic processing and localization within vesicles deficient in NPC1 suggest that NPC2 function might also be compromised in NPC1 mice. A recent study has demonstrated the importance of N-glycosylation for NPC2 function and localization [44]. Thus it is tempting to speculate that NPC2 is in fact the primary defect in NPC disease and that defects in NPC1 also result in NPC2 ‘malfunctioning’, which would explain how two disparate proteins could produce the same phenotype. This scenario is consistent with results obtained from NPC1/NPC2 double mutant mice, which exhibit similar disease onset and progression to NPC1-null mice, whereas the NPC2 hypomorphic mice have later disease onset and progression [17]. No true NPC2-null mouse model has been generated, so the precise effects of NPC2 deficiency cannot be fully evaluated. It is possible that complete lack of NPC2 results in lethality in mice, which could explain why patients with defects in NPC2 have a more severe NPC disease than patients with defects in NPC1 [63]. Further studies utilizing endosomes from NPC2 mice should clarify the cellular functions of NPC1 and NPC2 and will provide more information with which to probe the relationship between these proteins and NPC disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 DK065793 and RO1 DK54736 and by a grant from the March of Dimes Foundation. F. W. C. is a recipient of a Cameron and Hayden Lord medical research foundation fellowship.

References

- 1.Vanier M. T., Rodriguez-Lafrasse C., Rousson R., Gazzah N., Juge M.-C., Pentchev P. G., Revol A., Louisot P. Type C Niemann–Pick disease: spectrum of phenotypic variation in disruption of intracellular LDL-derived cholesterol processing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1096:328–337. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(91)90069-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pentchev P. G., Brady R. O., Blanchette-Mackie E. J., Vanier M. T., Carstea E. D., Parker C. C., Goldin E., Roff C. F. The Niemann–Pick C lesion and its relationship to the intracellular distribution and utilization of LDL cholesterol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1225:235–243. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson M. C., Vanier M. T., Suzuki M. C., Morris J. A., Carstea E., Neufeld E. B., Blanchette-Mackie E. J., Pentchev P. G. Niemann–Pick disease type C: a lipid trafficking disorder. In: Scriver C. R., Beaudet A. L., Sly W. S., Valle D., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 3611–3633. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carstea E. D., Morris J. A., Coleman K. G., Loftus S. K., Zhang D., Cummings C., Gu J., Rosenfeld M. A., Pavan W. J., Krizman D. B., et al. Niemann–Pick C1 disease gene: homology to mediators of cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1997;277:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naureckiene S., Sleat D. E., Lackland H., Fensom A., Vanier M. T., Wattiaux R., Jadot M., Lobel P. Identification of HE1 as the second gene of Niemann–Pick C disease. Science. 2000;290:2298–2301. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko D. C., Gordon M. D., Jin J. Y., Scott M. P. Dynamic movements of organelles containing Niemann–Pick C1 protein: NPC1 involvement in late endocytic events. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:601–614. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang M., Dwyer N. K., Love D. C., Cooney A., Comly M., Neufeld E., Pentchev P. G., Blanchette-Mackie E. J., Hanover J. A. Cessation of rapid late endosomal tubulovesicular trafficking in Niemann–Pick type C1 disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:4466–4471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081070898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang M., Dwyer N. K., Neufeld E. B., Love D. C., Cooney A., Comly M., Patel S., Watari H., Strauss J. F., 3rd, Pentchev P. G., Hanover J. A., Blanchette-Mackie E. J. Sterol-modulated glycolipid sorting occurs in Niemann–Pick C1 late endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3417–3425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohgami N., Ko D. C., Thomas M., Scott M. P., Chang C. C., Chang T. Y. Binding between the Niemann–Pick C1 protein and a photoactivatable cholesterol analog requires a functional sterol-sensing domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:12473–12478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405255101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies J. P., Chen F. W., Ioannou Y. A. Transmembrane molecular pump activity of Niemann–Pick C1 protein. Science. 2000;290:2295–2298. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirchhoff C., Osterhoff C., Young L. Molecular cloning and characterization of HE1, a major secretory protein of the human epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 1996;54:847–856. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.4.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamura N., Kiuchi S., Tamba M., Kashima T., Hiramoto S., Baba T., Dacheux F., Dacheux J. L., Sugita Y., Jin Y. Z. A porcine homolog of the major secretory protein of human epididymis, HE1, specifically binds cholesterol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1438:377–387. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedland N., Liou H. L., Lobel P., Stock A. M. Structure of a cholesterol-binding protein deficient in Niemann–Pick type C2 disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:2512–2517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437840100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko D. C., Binkley J., Sidow A., Scott M. P. The integrity of a cholesterol-binding pocket in Niemann–Pick C2 protein is necessary to control lysosome cholesterol levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:2518–2525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530027100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blom T. S., Linder M. D., Snow K., Pihko H., Hess M. W., Jokitalo E., Veckman V., Syvanen A. C., Ikonen E. Defective endocytic trafficking of NPC1 and NPC2 underlying infantile Niemann–Pick type C disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:257–272. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M., Sun M., Dwyer N. K., Comly M. E., Patel S. C., Sundaram R., Hanover J. A., Blanchette-Mackie E. J. Differential trafficking of the Niemann–Pick C1 and 2 proteins highlights distinct roles in late endocytic lipid trafficking. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 2003;92:63–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sleat D. E., Wiseman J. A., El-Banna M., Price S. M., Verot L., Shen M. M., Tint G. S., Vanier M. T., Walkley S. U., Lobel P. Genetic evidence for nonredundant functional cooperativity between NPC1 and NPC2 in lipid transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:5886–5891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308456101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Te Vruchte D., Lloyd-Evans E., Veldman R. J., Neville D. C., Dwek R. A., Platt F. M., Van Blitterswijk W. J., Sillence D. J. Accumulation of glycosphingolipids in Niemann–Pick C disease disrupts endosomal transport. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:26167–26175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311591200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies J. P., Scott C., Oishi K., Liapis A., Ioannou Y. A. Inactivation of NPC1L1 causes multiple lipid transport defects and protects against diet-induced hypercholesterolemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12710–12720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies J. P., Cotter P. D., Ioannou Y. A. Cloning and mapping of human Rab7 and Rab9 cDNA sequences and identification of a Rab9 pseudogene. Genomics. 1997;41:131–134. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ioannou Y. A., Bishop D. F., Desnick R. J. Overexpression of human α-galactosidase A results in its intracellular aggregation, crystallization in lysosomes, and selective secretion. J. Cell Biol. 1992;119:1137–1150. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuda M., Viitala J., Matteson J., Carlsson S. R. Cloning of cDNAs encoding human lysosomal membrane glycoproteins, h-lamp-1 and h-lamp-2: comparison of their deduced amino acid sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:18920–18928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez-Paris J., Nolta K., Steck T. Characterization of lysosomes isolated from Dictyostelium discoideum by magnetic fractionation. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:9110–9116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voikar V., Rauvala H., Ikonen E. Cognitive deficit and development of motor impairment in a mouse model of Niemann–Pick type C disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2002;132:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshansky V., Vinay P. Proton gradient formation in early endosomes from proximal tubules. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1284:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(96)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loftus S. K., Morris J. A., Carstea E. D., Gu J. Z., Cummings C., Brown A., Ellison J., Ohno K., Rosenfeld M. A., Tagle D. A., et al. Murine model of Niemann–Pick C disease: mutation in a cholesterol homeostasis gene. Science. 1997;277:232–235. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ioannou Y. A., Zeidner K. M., Grace M. E., Desnick R. J. Human α-galactosidase A: glycosylation site 3 is essential for enzyme solubility. Biochem. J. 1998;332:789–797. doi: 10.1042/bj3320789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bordier C. Phase separation of integral membrane proteins in Triton X-114 solution. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:1604–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folch J., Lees M., Sloane Stanley G. H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi T., Beuchat M. H., Chevallier J., Makino A., Mayran N., Escola J. M., Lebrand C., Cosson P., Gruenberg J. Separation and characterization of late endosomal membrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32157–32164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storrie B., Madden E. A. Isolation of subcellular organelles. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:203–225. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82018-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi T., Beuchat M.-H., Lindsay M., Frias S., Palmiter R. D., Sakuraba H., Parton R. G., Gruenberg J. Late endosomal membranes rich in lysobisphosphatidic acid regulate cholesterol transport. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:113–118. doi: 10.1038/10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neufeld E. B., Wastney M., Patel S., Suresh S., Cooney A. M., Dwyer N. K., Roff C. F., Ohno K., Morris J. A., Carstea E. D., et al. The Niemann–Pick C1 protein resides in a vesicular compartment linked to retrograde transport of multiple lysosomal cargo. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:9627–9635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alpy F., Stoeckel M. E., Dierich A., Escola J. M., Wendling C., Chenard M. P., Vanier M. T., Gruenberg J., Tomasetto C., Rio M. C. The steroidogenic acute regulatory protein homolog MLN64, a late endosomal cholesterol-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:4261–4269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi T., Stang E., Fang K. S., de Moerloose P., Parton R. G., Gruenberg J. A lipid associated with the antiphospholipid syndrome regulates endosome structure and function. Nature (London) 1998;392:193–197. doi: 10.1038/32440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pentchev P. G., Vanier M. T., Suzuki K., Patterson M. C. Niemann–Pick Disease Type C: a celllular cholesterol lipidosis. In: Scriver C. R., Beaudet A. L., Sly W. S., Valle D., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 2625–2639. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leventhal A. R., Leslie C. C., Tabas I. Suppression of macrophage eicosanoid synthesis by atherogenic lipoproteins is profoundly affected by cholesterol-fatty acyl esterification and the Niemann–Pick C pathway of lipid trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8084–8092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310672200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passeggio J., Liscum L. Flux of fatty acids through NPC1 lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:10333–10339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millat G., Marcais C., Rafi M. A., Yamamoto T., Morris J. A., Pentchev P. G., Ohno K., Wenger D. A., Vanier M. T. Niemann–Pick C1 disease: the I1061T substitution is a frequent mutant allele in patients of Western European descent and correlates with a classic juvenile phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:1321–1329. doi: 10.1086/302626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millat G., Marcais C., Tomasetto C., Chikh K., Fensom A. H., Harzer K., Wenger D. A., Ohno K., Vanier M. T. Niemann–Pick C1 disease: correlations between NPC1 mutations, levels of NPC1 protein, and phenotypes emphasize the functional significance of the putative sterol-sensing domain and of the cysteine-rich luminal loop. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:1373–1385. doi: 10.1086/320606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frolov A., Zielinski S. E., Crowley J. R., Dudley-Rucker N., Schaffer J. E., Ory D. S. NPC1 and NPC2 regulate cellular cholesterol homeostasis through generation of low density lipoprotein cholesterol-derived oxysterols. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25517–25525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walter M., Davies J. P., Ioannou Y. A. Telomerase immortalization upregulates Rab9 expression and restores LDL cholesterol egress from Niemann–Pick C1 late endosomes. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:243–253. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200230-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lebrand C., Corti M., Goodson H., Cosson P., Cavalli V., Mayran N., Faure J., Gruenberg J. Late endosome motility depends on lipids via the small GTPase Rab7. EMBO J. 2002;21:1289–1300. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chikh K., Vey S., Simonot C., Vanier M. T., Millat G. Niemann–Pick type C disease: importance of N-glycosylation sites for function and cellular location of the NPC2 protein. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2004;83:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi T., Beuchat M. H., Lindsay M., Frias S., Palmiter R. D., Sakuraba H., Parton R. G., Gruenberg J. Late endosomal membranes rich in lysobisphosphatidic acid regulate cholesterol transport. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:113–118. doi: 10.1038/10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umeda A., Fujita H., Kuronita T., Hirosako K., Himeno M., Tanaka Y. Distribution and trafficking of MPR300 is normal in cells with cholesterol accumulated in late endocytic compartments: evidence for early endosome-to-TGN trafficking of MPR300. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:1821–1832. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300153-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor R. S., Wu C. C., Hays L. G., Eng J. K., Yates J. R., 3rd, Howell K. E. Proteomics of rat liver Golgi complex: minor proteins are identified through sequential fractionation. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:3441–3459. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(20001001)21:16<3441::AID-ELPS3441>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Felder S., Miller K., Moehren G., Ullrich A., Schlessinger J., Hopkins C. R. Kinase activity controls the sorting of the epidermal growth factor receptor within the multivesicular body. Cell. 1990;61:623–634. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90474-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]