Abstract

Objective To determine the effectiveness of innovations in management of chronic disease involving nurses for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Design Systematic review of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources 24 electronic databases searched for English or Dutch language studies published between January 1980 and January 2005.

Review methods Included studies described inpatient, outpatient, and community based interventions for chronic disease management that were led, coordinated, or delivered by nurses. Hospital at home and early discharge schemes for acute exacerbations of COPD were excluded.

Results We identified nine relevant randomised controlled trials, most of which had some potential methodological flaws. All the interventions seemed to be variations on a case management model. The interventions described could be divided into brief (one month) and longer term (around a year) or more intensive interventions. Only two studies examined the effect of brief interventions, these found little evidence of any benefit. Meta-analysis of the long term interventions failed to detect any influence on mortality at 9-12 months' follow-up (Peto odds ratio 0.85, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 1.26). There was evidence that the long term interventions had not improved patients' health related quality of life, psychological wellbeing, disability, or pulmonary function. The evidence on whether long term interventions reduced readmissions to hospital was equivocal, but the only study exclusively directed at patients on long term oxygen therapy reported a reduction in readmission. We identified several outcomes where little or no evidence was available; these included patients' satisfaction, self management skills, adherence with treatment recommendations, the likelihood of smoking cessation, and the effect of the interventions on carers.

Conclusion There is little evidence to date to support the widespread implementation of nurse led management interventions for COPD, but the data are too sparse to exclude any clinically relevant benefit or harm arising from such interventions.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects an estimated 600 million people worldwide1 and in Europe it is the fifth leading cause of death.2–3 Each year the NHS spends more than £800m ($1415m, €1161m) on the disease,4 and exacerbations of COPD are a principal cause of the pressure on acute hospital beds in winter.5 Recognition of the public health burden of COPD has provided the impetus to develop new models of care. In the United Kingdom innovations in clinical service for COPD are being driven by a host of initiatives to redesign roles and processes in primary care and at the primary and secondary care interface, including changes to community and primary care nursing6,7 and general practitioners' contracts8 and schemes to support self management, such as the expert patient programme,9 together with the national service frameworks.10

The literature around these service innovations describes two types of interventions: hospital at home or early discharge schemes for acute exacerbations and interventions aimed at improving the management of COPD as a chronic disease. Such interventions may be multidisciplinary but commonly they are led, coordinated, and delivered (at least in part) by nurses. Ram and colleagues recently reviewed the role of early discharge schemes and hospital at home schemes for acute exacerbations of COPD11 and suggested that they are safe and should be adopted. But what is the evidence to support schemes to improve the chronic disease management of COPD?

As part of a larger project12 that attempted to synthesise all the available evidence (including qualitative, quantitative, economic, and “grey”13 literature) on the effectiveness of all the different clinical service innovations for COPD provided or led by nurses, we conducted a systematic review of randomised controlled trials of chronic disease management interventions for COPD.

Methods

Types of trials

To be considered for inclusion, studies had to evaluate clinical service interventions or packages of care aimed at improving the management of patients with COPD in the community. Eligible studies included inpatient, outpatient, or community based interventions that were either nurse led, nurse coordinated, or largely delivered by nurses. (Whenever necessary we contacted authors to establish the nature of the intervention.) We excluded drug trials, hospital at home or early discharge schemes for patients with acute exacerbations, educational interventions directed solely at other healthcare providers, and studies in which a substantial proportion of patients did not have COPD.

Types of outcomes

Principal outcomes of interest included survival, use of healthcare resources, activities of daily life, patients' health related quality of life (HRQOL), and carers' quality of life. We also examined all other reported outcomes.

Identification and selection of trials

We performed a systematic literature review of English and Dutch language papers using a predefined protocol. (We included Dutch papers because of the tradition of research on community nursing in the Netherlands.) We searched 16 electronic English language databases for the period January 1980 to January 2005 and eight Dutch citation databases and hand searched the conference proceedings of seven respiratory associations (see bmj.com, appendix 1). We also wrote to researchers and practitioners to identify unpublished trials.

Two reviewers working independently screened every citation retrieved in the searches and obtained the full text of all potentially eligible studies. BC undertook data extraction, using forms developed for the study, and quality assessment, which was checked by ST. HV extracted data from the Dutch language papers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion among the steering group.

Assessment of methodological quality of trials

We used the Delphi list14 and the Jadad criteria15 to assess methodological quality. We used the results of our data extraction together with the outcomes of the quality assessment to allocate an evidence score to each individual study using the levels of evidence from the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine.16

Synthesis

We grouped the findings of each study by type or duration of intervention and synthesised each outcome variable separately with an overall score for level of evidence for each outcome. When feasible and appropriate we conducted meta-analyses and calculated Peto odds ratios or Cohen's d standardised differences using Comprehensive Meta Analysis software (Biostat, NJ, 1999). Potentially important outcomes that had not been evaluated in any of the studies were identified by wider consultation, in particular with consumers, and by the review's advisory groups.

Results

Search for trials

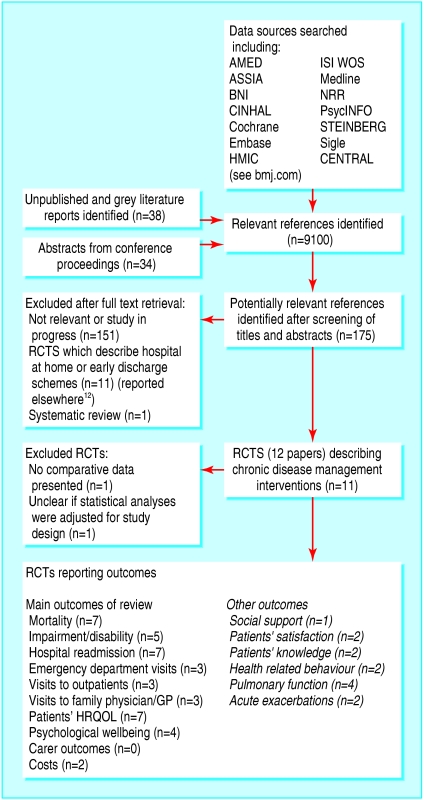

After screening of titles and abstracts we identified 175 potentially relevant articles, of which we included nine randomised controlled trials describing interventions for the management of chronic disease (fig 1).17–25 We also identified one systematic review26 that included four of the trials we identified. We identified five potentially relevant studies whose results were unavailable because the studies were ongoing or being written up (see bmj.com, appendix 2). We excluded two potential trials because one did not present any data comparing the intervention and control groups27 and in the other the results of the statistical analyses did not seem to be adjusted for the cluster randomised design.28

Fig 1.

Process of study selection

Methodological quality

Most of the trials had potential methodological limitations, and only two studies reported on both random sequence generation and allocation concealment (see bmj.com, appendix 3). Five trials either did not report a clear calculation of sample size or failed to achieve the intended sample size. We assessed the level of evidence for each of the individual trials to be either 2b (“low quality randomised controlled trial”) or 1b– (individual randomised controlled trial with a wide confidence interval; we have also used this where no confidence interval was supplied).16

Description of the studies

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the included studies. Most studies included patients with moderate or severe COPD (British Thoracic Society definitions29); one study included only patients receiving long term oxygen therapy.21 The interventions could be divided into brief interventions after a hospital admission (two studies,22,23 both around one month in duration) and more intensive24 or long term studies (around a year duration17–21,25) with follow-up at one year. The interventions studied had many similarities and all seemed to be variations on a “case management” approach (involving “the active management of high risk people with complex needs with case managers, usually nurses, taking responsibility for caseloads working in an integrated system”30). All the interventions included home visits by a nurse, except for one that was clinic based25 and two studies that were unclear on this point.19,22 Three interventions included telephone follow-up.21,22,24 Promotion of self care or self management30 was a major component of most of the home visits. This typically involved educating patients about medication and giving advice on stopping smoking, fitness, and the early identification of acute exacerbations. Some interventions included regular spirometry or pulse oximetry.19–21 Only the two most recent studies mentioned providing a supply of drugs or a prescription to be kept at home and filled in the event of an acute exacerbation,24,25 and these were also the only studies to mention the introduction of self treatment plans for patients. Two of the studies promoted exercise or physical activity,20,24 and one included a fitness programme led by a physiotherapist.25

Table 1.

Characteristics of trials included in the review

| Study | Intervention group | Control group | Duration | Description of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockcroft 198717 UK | n=42, 69% men, mean age 69.2 years (range 46-84), mean (SD) FEV1 0.78 I (0.31) | n=33, 67% men, mean age 70.5 years (range 51-84), mean (SD) FEV1 0.88 I (0.43) | 9 months | Intervention: respiratory health worker visiting patients at home. Discharge planning component: not specified, not all patients recruited after acute admission. Home visits: patients visited once a month. Visits educative and supportive, tailored to individual needs. Intervention structured to published nursing model that entailed identifying problems in activities of daily living and setting goals to increase independence in these activities. Patients encouraged to recognise signs of deterioration and to take appropriate action, including contacting doctor. Nurses did not contact doctors except in cases of emergency (happened only once). Out of hours cover: not specified. Procedure for clinical deterioration: not specified. Clinical support to nurses: from consultant chest specialist and consultant physiotherapist who were independent of study. Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: not specified |

| Bergner 198818 USA | n=99, 64% men* | 2 comparison groups: office care (n=100, 67% men), standard home care (n=102, 78% men)* | 12 months | Intervention: specialised respiratory home care programme delivered by trained respiratory nurses. Discharge planning component: not specified, not all patients recruited after acute admission. Home visits: home care nurse visited within 24 hours of study entry and then as often as nurse considered necessary but at least once a month during study year. Nurses provided acute and continuing care—no other details given. Out of hours cover: not specified. Procedure for clinical deterioration: not specified. Clinical support to nurses: nurses worked with primary physician, care and medications provided only with physician approval. Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: not specified |

| Littlejohns 199119 UK | n=73, 67% men, mean (SD) age 62.9 (7.6) years, mean (SD) FEV1 45.2% (22.4%) of predicted, mean (SD) FVC 70.0% (17.3%) of predicted, mean (SD) SaO2 at rest 95.6% (3.0%), on exercise 91.5% (4.6%) | n=79, 63% men, mean (SD) age 62.5 (7.6) years, mean (SD) FEV1 50.2% (23.0%) of predicted, mean (SD) FVC 73.2% (19.0%) of predicted, mean (SD) SaO2 at rest 96.1% (2.7%), on exercise 91.7% (4.3%) | 12 months | Intervention: respiratory health worker. Discharge planning component: not applicable. Home visits: not specified. Intervention: patients received normal care at chest clinic plus respiratory health worker who provided health education directed at the patient and primary care team; monitoring of treatment compliance and optimisation of treatment by ensuring correct inhalation techniques and supervision of domiciliary oxygen etc; monitoring of spirometry results and symptoms to enable acute exacerbations and worsening heart failure to be detected and treated early; liaison between hospital based services (including domiciliary physiotherapy and social services) and GP. Out of hours cover: not specified. Procedure for deterioration: not specified. Clinical support to nurses: not specified Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: not specified |

| Smith 199920 Australia | n=48, 56% men, mean (SD) age 70.0 (1.2) years, mean (SD) FEV1 0.84 I (0.06) | n=48, 65% men, mean (SD) age 69.8 (1.2) years, mean (SD) FEV1 0.90 I (0.07) | 12 months | Intervention: “respiratory home based nursing intervention” (HBNI). Discharge planning component: inpatients visited by HBNI nurse on ward, discharge planning with goals for discharge. Case conference with social worker, hospital medical officer, GP, and HBNI nurse if considered beneficial (outpatients and GP referrals evaluated at home, discussion with GP on patient's needs, involvement of domiciliary services facilitated, appliances provided, and need for O2 therapy assessed at home). Home visits: inpatients seen by HBNI nurse within week of discharge. All referrals followed up by 2-4 weekly visits, spirometry and oximetry performed at each visit, and results communicated to GP. Ongoing education including use of inhaler medication, medication compliance, and fitness advice (as required fitness advice including: upper and lower limb training, “intimacy advice,” and coping strategies for dyspnoea). Education and counselling around smoking cessation, referral to GP for nicotine replacement. Nurse also aimed to identify exacerbations early. Out of hours cover: not specified. Procedure for clinical deterioration: not specified. Clinical support to nurses: not specified. Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: not specified |

| Farrero 200021 Spain | n=60†, mean (SD) age 68 (7) years, mean (SD) FVC 40% (11%) predicted, mean (SD) FEV1 28% (8%) predicted, mean (SD) PaO2 51 (6) mm Hg, mean (SD) PaCo2 54 (7) mmHg | n=62†, mean (SD) age 69 (8) years, mean (SD), FVC 38% (11%) of predicted, mean (SD) FEV1 27% (9%) predicted, mean (SD) PaO2 50 (7) mm Hg, mean (SD) PaCo2 56 (8) mm Hg | 12 months | Intervention: hospital based home care programme. Discharge planning component: not applicable. Home visits: every three months by respiratory nurse. Visits included: questionnaire designed to detect changes in underlying respiratory symptoms; spirometry; pulse oximetry breathing room air and oxygen. Phone calls: monthly phone calls to patient by respiratory nurse. Out of hours cover: not stated. Procedure for clinical deterioration: patient could initiate attention depending on problem, resolved either by phone call, home visit, or visit to day hospital equipped to carry out chest radiography, arterial blood gases, and ECG and to provide intensive medical treatment if necessary. Clinical support to nurses: respiratory nurse supervised by respiratory physician. Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: not specified |

| Egan 200222 Australia | n=33, 36% men, mean age 67.2 years, 19% had FEV1 <35% predicted | n=33, 60% men, mean age 67.8 years, 19% had FEV1 <35% predicted | Duration of intervention 6 weeks, follow-up for 3 months | Intervention: nursing based case management. Discharge planning component: case manager (CM) conducted case conference and arranged discharge planning. Intervention: after admission CM conducted comprehensive nursing assessment to identify physical, psychosocial, and resource needs, during admission CM coordinated patient's care using clinical path. CM provided education for patient and carer on managing disease, treatment, rehabilitation, and available community services, conducted case conference and arranged discharge planning. After discharge CM provided ongoing support and acted as referral point for community services for patient with follow-up care at 1 and 6 weeks after discharge. Home visits: not clear if CM visited patient at home. Phone calls: CM made phone calls to patient and caregiver on regular basis. Out of hours cover: not specified. Procedure for clinical deterioration: not specified. Clinical support to nurses: not specified. Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: not specified |

| Hermiz 200223 Australia | n=84, 49% men, mean age 67.1 years‡ | n=93, 46% men, mean age 66.7 years‡ | Duration of intervention 1 month, follow-up 3 months | Intervention: home based care by community nurse. Discharge planning component: none. Home visits: visit by community nurse one week and one month after discharge. First visit included detailed assessment of patient's health status and respiratory function; written and verbal education on disease and advice on smoking cessation; managing activities of daily living and energy conservation; exercise; understanding and use of drugs; health maintenance; and early recognition of signs that require medical intervention. Nurse also identified problems and, if indicated, referred patients to other services, such as home care. Care plan documenting problem areas, education provided, and referral to other services posted to patient's GP, and GP contacted by phone, if necessary. Second visit included: progress and need for further follow-up reviewed. Patients encouraged to refer to education booklet for guidance and to keep in contact with GP. Out of hours cover: not applicable. Procedure for clinical deterioration: not applicable. Clinical support for nurses: not specified. Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: not specified |

| Bourbeau 200324 Canada | n=96 (52% men), mean (SD) age 69.4 (6.5) years, mean (SD) FEV1 1 l (0.33), FEV1:FVC 45% | n=95 (59% men), mean (SD) age 69.6 (7.4) years, mean (SD) FEV1 0.98 l (0.31), FEV1:FVC 45% | 12 months | Intervention: “disease specific self management programme” delivered by trained health professionals (most were nurses) acting as case managers. Discharge planning component: not applicable. Home visits: weekly for first 8 weeks, visits lasted one hour. Intervention included an educational programme covering: basic information about COPD, breathing and coughing techniques, energy conservation, relaxation exercises, inhaler technique, an individualised action plan for acute exacerbation, healthy lifestyles (smoking, nutrition, sexuality, sleep, and managing emotions), leisure activities and travelling, a simple home exercise programme, and education around long term oxygen therapy, if appropriate. After week 7 patients encouraged to follow (unsupervised) the home exercise programme at least 3 times a week for 30-45 mins. Phone calls: weekly for first 8 weeks then monthly, patients also able to phone case managers for advice and supervision of treatment. Out of hours cover: not specified. Procedure for clinical deterioration: patients had customised action plan for acute exacerbation, contact list, symptom monitoring list linked to appropriate therapeutic actions, and prescription for drugs. Clinical support for case managers: received supervision and collaboration from treating physician. Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: not specified |

| Monninkhof 200325 Netherlands | n=127 (85% men), mean (SD) age 65 (7) years, mean (SD) FEV1 1.7 l (0.56) | n=121 (84% men), mean (SD) age 65 (7) years, mean (SD) FEV1 1.76 l (0.54) | 12 months | Intervention: comprehensive self management educational programme, delivered by respiratory nurse, and fitness course delivered by physiotherapists. Discharge planning component: not applicable. Intervention: five clinic based, 2 hour, group self management education sessions held at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12 weeks. Educational programme included information about COPD; coping with breathlessness; plan for acute exacerbation; exercise; relaxation and energy conservation; nutrition; communication with their chest physician; and social relationships. Home visits: not specified. Phone calls: not specified. Out of hours cover: not specified. Procedure for clinical deterioration: patients had self treatment action plans for acute exacerbation based on symptom perception, including prescription for drugs or medication to keep at home. Clinical support to nurses: not specified. Additional services and health carers involved in intervention: one or two 1 hour small group fitness sessions a week led by physiotherapist for duration of follow-up. Beside physical goals fitness programme aimed at coping with COPD, social interactions, and behavioural change. Programme included strength training, breathing and cardiovascular exercises, individual goals and training log. Note: patient recruitment followed on from earlier RCT of fluticasone propionate (patients were re-randomised for this study) |

FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second, FVC=forced vital capacity, SaO2=arterial oxygen saturation, PaO2=partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, GP=general practitioner, ECG=electrocardiography, COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Across study: mean age 65.1 years, mean FEV1 33.8% predicted.

All patients required and were receiving long term oxygen therapy.

No data provided on severity of COPD at baseline.

Synthesis of findings

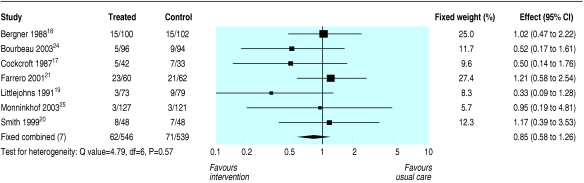

Table 2 shows the effects of the brief and long term interventions on the outcomes examined. The results of statistical meta-analysis are shown where possible, but most outcome data were presented in various ways across the studies and it either was not possible to perform a meta-analysis or would have been potentially misleading because only two of the small number of studies reporting an outcome could have been included. Information on brief interventions is limited because there were only two randomised controlled trials. Meta-analysis of the trials of the long term or intensive interventions failed to detect any influence on mortality at 9-12 months' follow-up (Peto odds ratio 0.85 favouring intervention, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 1.26; fig 2). We found a similar result when we carried out sensitivity analyses excluding the trial involving only patients on long term oxygen therapy.

Table 2.

Effects of interventions for management of COPD by nurses in community with estimated level of evidence score

| Outcome*examined | Effect of intervention on outcome | Estimated level of evidence† |

|---|---|---|

| Patients' HRQOL: | ||

| Brief interventions | No difference detected when measured by disease specific instruments | 1a# |

| Long term or intensive interventions | No difference detected (disease specific or generic instruments) at 12 month follow-up | 1a# |

| Patients' psychological wellbeing: long term interventions | No difference detected | 1a# |

| Impairment and disability: long term interventions | No difference detected in total SIP scores (or outside assessment) | 1a# (2b) |

| No of COPD exacerbations: long term interventions | No difference detected | 1a# |

| Pulmonary function: long term interventions | No difference detected | 1a# |

| Mortality: long term interventions | No difference detected | 1a |

| Emergency department attendance: long term interventions | May be reduced | 1a# |

| No of outpatient visits: long term interventions | No difference detected | 1a# |

| Patients' psychological wellbeing: brief interventions | No difference detected | 2b |

| Patients' knowledge of COPD: long or brief interventions | May be increased | 2b |

| Social support: brief interventions | No difference detected when measured by social support survey | 2b |

| Unscheduled or respiratory readmission: brief interventions | No difference detected | 2b |

| Patients' symptoms: long term interventions | No difference detected | 1b- |

HRQOL=health related quality of life; SIP=sickness impact profile.

Outcomes listed are not necessarily primary outcomes of trials.

Adapted from levels of evidence (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)16: 1a=systematic review with homogeneity of randomised controlled trials, 1a# denotes that at least two randomised controlled trials report on the outcome, but we were unable to perform a statistical meta-analysis (see text for explanation), 1b-= single RCT with wide confidence interval or no confidence interval supplied, 2b= evidence from a single lower quality RCT.

Fig 2.

Effects of nurse led management interventions for COPD on mortality from trials of long term or intensive interventions (Peto odds ratios)

Neither of the randomised controlled trials of brief interventions found evidence of a reduction in readmissions to hospital. The box summarises the outcomes where the evidence is equivocal. Evidence for a reduction in all cause readmissions at around 12 months' follow-up with the long term or more intensive interventions was equivocal. Bourbeau et al (40% reduction in readmissions for acute exacerbations, 57% reduction in other admissions, confidence intervals not given, both P = 0.01)24 and Farrero et al (mean number of admissions per intervention patient 0.5 (SD 0.9) v 1.3 (SD 1.7) per control patient)21 reported a significant reduction in hospital admissions with their interventions, but three other studies reporting this outcome found no significant effect on hospital admissions.17,19,20 Only two studies reported on respiratory readmissions at 12 months, again the results differed.17,24 The evidence around days spent in hospital and visits to the general practitioner or family physician was also equivocal, but there was some evidence for fewer visits to an emergency department (table 2).

Meta-analysis of the three studies23–25 reporting health related quality of life measured by the total St George's respiratory questionnaire score at between three and six months' follow-up found no detectable effect (Cohen's d standardised difference (expressed in units of SD) 0.06, –0.14 to 0.26, fixed effects model, test for heterogeneity P = 0.61). Overall the evidence suggested that long term interventions do not improve patients' health related quality of life at 12 months' follow-up and may not improve patients' psychological wellbeing, impairment and disability, or pulmonary function. For many outcomes there was only reasonable quality evidence from a single trial, and the evidence was even weaker, or entirely absent, for several other outcomes (summarised in the box). In particular, there was an absence of evidence around the effect of these interventions on carers.

Discussion

At present there is little evidence from randomised controlled trials to support the widespread adoption of chronic disease management by respiratory nurses, including case management, for patients in the community with moderate or severe COPD. The evidence is sparse and what evidence there is has generally failed to detect any evidence of benefit except for readmission to hospital, where the evidence is equivocal.

Only two trials examined brief interventions for chronic disease management, and they found virtually no evidence to support their implementation. Although there is no evidence that long term interventions influence mortality, health related quality of life, psychological wellbeing, disability, or pulmonary function at 12 months, it is possible that these interventions do confer benefits but that the effect sizes are too small to have been detected by the studies conducted to date. As the evidence around readmissions to hospital is equivocal, the possibility that case management might reduce hospital readmissions at 12 months' follow-up requires further investigation. Of the two studies that reported a reduction in readmissions, one was the only study directed exclusively at patients on long term oxygen therapy21 and such patients may benefit from case management. The other intervention24 may have been more highly structured than earlier interventions with negative findings. Furthermore, hospital readmission for all causes may be an inappropriate outcome to assess the effectiveness of chronic disease management as better care might result in more elective admissions. The sparse evidence from randomised controlled trials on respiratory readmissions, however, is equivocal.

Summary of reported outcomes where evidence is equivocal, very weak, or absent

Equivocal evidence of effect on:

Hospital readmissions, respiratory cause or all causes: long or intensive interventions

Days spent in hospital: long or intensive interventions

Visits to the general practitioner or family physician

No evidence available or only weak evidence on:

Patients' self management skills, coping, or self confidence

Smoking cessation among patients or their adherence with recommended treatment

Patients' and carers' satisfaction with the interventions or their preferences for care

Carers' quality of life

Effect on other community services and the opinion of the providers of other community services

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

We directed extensive effort at the identification of unpublished and ongoing studies and the systematic documentation of the estimated level of evidence for a wide range of outcomes. However, we included only English or Dutch language papers and we may have overestimated the methodological limitations of the included studies because we relied on published reports.

Comparison with other studies

Our review complements the work of Ram and colleagues, who recently reviewed the effectiveness of hospital at home or early discharge schemes for COPD.11 All of the studies in their review were led or delivered by nurses, and the authors concluded that they could be safely used to care for patients and seemed to be cost effective. A Cochrane systematic review of educating patients with COPD on self management, last updated in 2002, found no effect on hospital admissions, emergency room visits, days off work, and lung function and inconclusive results around health related quality of life.31 The authors concluded that more research was needed. Pulmonary rehabilitation is known to be beneficial for patients with COPD,32 but only one of the interventions in our review had a pulmonary rehabilitation component.25 It should also be noted that few of the interventions studied seemed to involve the use of written protocols and care pathways, thus they may not represent more recent developments in management of chronic disease.

In contrast to the findings of our disease specific review, a meta-analysis of disease management programmes33 for a wide variety of chronic illnesses, including COPD, found education of patients and reminders (prompts to remind patients to perform specific tasks related to their care) were associated with improvements in patients' disease control. Much of the other evidence on disease management comes from large non-experimental studies of generic interventions such as Evercare34 and Kaiser Permanente.35 Generic interventions aimed at high risk individuals may be more effective than disease specific interventions for COPD or the effect size of interventions for COPD that have been tested may be too small to be seen in the limited evaluations carried out to date, most of which had potential methodological weaknesses. Elphick and colleagues have suggested that systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials often fail to give adequate information on the long term outcomes of chronic diseases and have called for consideration of the inclusion of data from observational studies as well.36 We attempted this in our extended review12 but found that the inclusion of other types of study contributed little to our current findings. The extended review also identified a dearth of qualitative research in this area. We could not find a systematic review of chronic disease management interventions by nurses for asthma, but a Cochrane systematic review of programmes combining self management and regular practitioner review in asthma found these interventions to be beneficial.37 The difference between the findings of the Cochrane review and ours may reflect differences in the nature of these two chronic respiratory conditions.

Implications for policy makers and future research

Nurse led hospital at home or early discharge schemes for patients with COPD living in the community should be prioritised over the type of nurse led models of chronic disease management that have been studied to date. There is little evidence available at present to support most of these models that have been evaluated so far, although some studies are ongoing. Existing services providing this sort of care should be robustly evaluated against the aims of the particular service.

What is already known on this topic

There is evidence to support generic interventions for management of chronic disease

The massive public health burden of COPD has driven the development of clinical service innovations around the management of patients

Nurses are the key healthcare personnel involved in chronic disease management interventions for COPD

What this study adds

There is little robust evidence to support nurse management of chronic disease services for patients in the community with moderate or severe COPD

The interventions evaluated to date have not had a detectable effect on mortality, disability, and patients' health related quality of life or psychological wellbeing, while the evidence around hospital readmissions is equivocal

The evidence around other potentially important outcomes—such as patients' adherence to treatment regimens or satisfaction with care and the effect on carers—is extremely weak or absent

The evidence around long term or intensive case management and hospital readmission is currently equivocal and requires further study. The potential benefits, in terms of fewer hospital admissions and visits to emergency departments, with schemes for chronic disease management in patients with COPD receiving long term oxygen therapy should also be explored further. In addition, several potentially important outcomes have not been fully evaluated, including patients' satisfaction, self management, patients' coping and adherence, smoking cessation, and the effects on carers.

Supplementary Material

Details of searches, ongoing randomised controlled trials, and assessment of trial quality can be found on bmj.com

Details of searches, ongoing randomised controlled trials, and assessment of trial quality can be found on bmj.com

We thank Brian Schirn, Gene Feder, Martin Underwood, Gill Foster, Jill Goddard, Hazel Kilvington, Marie Montague, Sarah Cotter, Melanie Wakelin, Anne Spencer, Linda Stephenson, Lynette Edwards, staff at the Royal College of Nursing, members of the British Lung Foundation Breathe Easy groups, the International Primary Care Respiratory Group, and the Association of Respiratory Nurses.

Contributors: SJCT, CJG, JAW, JR, and RMB initiated and designed the study. BC, SJCT, CJG, JR, RMB, HJMV, and GE conducted the systematic review and interpreted the data. SJCT, BC, CJG, JAW, GE, RMB, HJMV, and JR drafted the paper. SJCT is guarantor.

Funding: NHS research and development service delivery and organisation programme. SJCT is funded by a Department of Health career scientist award in public health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The world health report 1998—life in the 21st century: a vision for all. www.who.int/whr/1998/en/ (accessed Oct 2004).

- 2.Murray CJL, Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Stein C. The global burden of disease 2000 project: aims, methods and data sources. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. (Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy Discussion Paper No 36.)

- 3.Pauwels R. COPD: the scope of the problem in Europe. Chest 2000;117: 332-5S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Bethesda, ML: NHLBI, 2003.

- 5.Damiani M, Dixon J. Managing the pressure: emergency hospital admissions in London, 1997-2001. London: Kings Fund, 2002.

- 6.Department of Health. Liberating the talents. Helping primary care trusts and nurses to deliver the NHS Plan. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/07/62/50/04076250.pdf (accessed Oct 2004).

- 7.Department of Health. Supporting people with long term conditions. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/09/98/68/04099868.pdf (accessed Jan 2005).

- 8.Department of Health. Investing in general practice—the new general medical services contract. www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/Publications/ PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/fs/en (accessed Oct 2004).

- 9.Secretary of State for Health. The expert patient: a new approach to chronic disease management for the 21st century. London: Stationery Office, 2001.

- 10.Department of Health. Chronic disease management and self-care. National Service Frameworks. A practical aid to implementation in primary care. www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/fs/en (accessed Oct 2004).

- 11.Ram FS, Wedzicha JA, Wright J, Greenstone M. Hospital at home for patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review of the evidence. BMJ 2004;329: 315-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Candy B, Taylor SJC, Griffiths CJ, Ramsay J, Wedzicha JA, Schirn B, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of innovations involving nurses for people in the community with chronic obstructive airways disease. London: Centre of General Practice and Primary Care, Institute of Community Health Science, Barts and The London, Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry, 2004.

- 13.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness. CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews. 2nd ed. York: CRD, 2001. (CRD Report No 4.)

- 14.Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Kessels AG, Boers M, Bouter LM, et al. The Delphi list a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51: 1235-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carrol D. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17; 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation. www.cebm.net/levels_of_evidence.asp#levels (accessed Mar 2005).

- 17.Cockcroft A, Bagnall P, Heslop A, Andersson N, Heaton R, Batstone J, et al. Controlled trial of respiratory health worker visiting patients with chronic respiratory disability. BMJ 1987:294; 225-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergner M, Hudson LD, Conrad DA, Patmont CM, McDonald GJ, Perrin EB, et al. The cost and efficacy of home care for patients with chronic lung disease. Med Care 1988;26: 566-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littlejohns P, Baveystock CM, Parnell H, Jones PW. Randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of a respiratory health worker in reducing impairment, disability, and handicap due to chronic airflow limitation. Thorax 1991;46: 559-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith BJ, Appleton SL, Bennett PW, Roberts GC, Del Fante P, Adams R, et al. The effect of a respiratory home nurse intervention in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Aust N Z J Med 1999;29: 718-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrero E, Escarrabill J, Prats E, Maderal M, Manresa, F. Impact of a hospital-based home-care program on the management of COPD patients receiving long-term oxygen therapy. Chest 2001;119: 364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egan E, Clavarino A, Burridge L, Teuwen M, White, E. A randomized control trial of nursing-based case management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lippincotts Case Manag 2002;7: 170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermiz O, Comino E, Marks G, Daffurn K, Wilson S, Harris, M. Randomised controlled trial of home based care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ 2003;325: 938-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, Rouleau M, Beaupre A, Begin R, et al. Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med 2003;163: 585-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monninkhof E, van der Valk P, van der Palen J, van Herwaarden C, Zielhuis G. Effects of a comprehensive self-management programme in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2003;22: 815-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith B, Appleton S, Adams R, Southcott A, Ruffin R. Home care by outreach nursing for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(3): CD000994. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kara M, Turkinaz ASTI. Effect of education on self-efficacy of Turkish patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pat Ed Counseling 2004;55: 114-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rea H, McAuley S, Stewart A, Lamont C, Roseman P, Didsbury P. Chronic disease management programme can reduce days in hospital for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int Med J 2004;34: 608-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The COPD Guidelines Groups of the Standards of Care Committee of the BTS. BTS guidelines for the management of COPD. Thorax 1997;52(suppl 5): S1-28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health. Improving chronic disease management. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/07/52/13/04075213.pdf (accessed 2004 October).

- 31.Monninkhof EM, van der Valk PDLPM, van der Palen J, van Herwaarden CLA, Partidge MR, Walters EH, et al. Self-management education for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4): CD002990. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Lacasse Y, Brosseau L, Milne S, Martin S, Wong E, Guyatt GH, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(4): CD003793. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Weingarten SR, Henning JM, Badamgarav E, Knight K, Hasselblad V, Gano A, et al. Interventions used in disease management programmes for patients with chronic illness—which ones work? Meta-analysis of published reports. BMJ 2002;325: 925-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kane RL, Keckhafer G, Robst J. Evaluation of the Evercare demonstration program. Final report. www.cms.hhs.gov/researchers/demos/evercare/ Evaluation_Evercare_Demonstration_Program.pdf (accessed Oct 2004).

- 35.Feachem RGA, Sekhri NK, White KL. Getting more for their dollar: a comparison of the NHS with California's Kaiser Permanente. BMJ 2002;324: 135-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elphick HE, Tan A, Ashby D, Smyth RL. Systematic reviews and lifelong diseases. BMJ 200;325: 381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J, Wilson AJ, Abramson M, Haywood P, et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3): CD001117. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.