Abstract

Staphylococcal exotoxins (SE) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulate cells of the immune system to produce proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines which mediate septic shock and acute lung inflammation. A coculture of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and pulmonary A549 epithelial cells was used to investigate inflammatory responses triggered by staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), toxic shock syndrome toxin 1, and LPS. The levels of interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, gamma interferon-inducible protein 10, monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, and RANTES were enhanced by 3.8-, 4.2-, 3.1-, 8.9-, 2-, and 2.9-fold, respectively, in cocultures of SEB-stimulated cells compared to in SEB-stimulated PBMC. In LPS-stimulated cocultures, only MCP-1 and RANTES levels were increased. These data suggest that the modulation of specific cytokines and chemokines is dependent on the stimulus and that there is bidirectional interaction between PBMC and lung epithelial cells to influence the immune response to these different stimuli.

Immune reactions in the epithelium are among the first lines of defense against inhaled pathogens and external challenges. Epithelial cells secrete chemokines in response to infection with pathogenic respiratory viruses and bacteria (6, 25). Although bacterial endotoxins and exotoxins do not induce chemokine release directly from epithelial cells (31), inhalation of these bacterial products causes lung pathology characteristic of these agents in animal models (3, 8). Moreover, systemic administration of these bacterial products also results in acute lung injury (5, 23). Because peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) are important in both defending against infection and in modulating immune responses in the lung, their role as mediators of lung injury in response to inhaled bacterial products was undertaken. An in vitro coculture system was devised to study the interaction of human pulmonary A549 epithelial cells and PBMC in response to endotoxin and staphylococcal exotoxins (SE).

Bacterial exotoxins and endotoxin are among the most common etiological agents that cause septic shock (12, 22, 27). Although similar cytokines are released from PBMC stimulated with these structurally distinct bacterial products, the stimulants act through different cell surface receptors. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) and the structurally related toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) are bacterial exotoxins that activate antigen-presenting cells by binding directly to major histocompatibility complex class II molecules (7, 28). These exotoxins are also called superantigens because of their ability to polyclonally stimulate large populations of T cells (4). Interaction of SE with antigen-presenting cells and T cells results in hyperproduction of cytokines and chemokines, resulting in toxic shock (11, 14, 17, 21, 24). The cytokines include tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and interleukin 1 (IL-1) and are proinflammatory mediators with immunoenhancing effects (16). Both IL-1 and TNF-α are, in turn, potent inducers of chemokine production by many cell types, including pulmonary epithelial cells. The CXC chemokine IL-8 induces neutrophil migration preferentially, whereas the CC chemokines, such as monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, and RANTES, have chemotactic and costimulatory effects on monocytes, T cells, natural killer cells, and eosinophils (1, 2, 18). The chemokines produced by airway epithelial cells play a critical role in regulating local inflammatory processes in the lung.

In contrast, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from gram-negative bacteria binds to a different receptor on monocytes/macrophages. A serum LPS-binding protein first binds to LPS and facilitates its binding to cell surface protein CD14 on monocytes/macrophages and other cells (10, 32). The subsequent interaction of LPS/CD14 complex with Toll-like receptors on these cells initiates transmembrane signaling (10, 20) and cellular activation resulting in cytokine and chemokine release, which can then induce chemokine production by lung epithelial cells.

This study was undertaken to investigate the interdependence of PBMC and pulmonary epithelial cells in the regulation of cytokine and chemokine production in response to stimulation by two different activators, superantigens or endotoxin. Differential modulation of specific cytokines and chemokines was observed in cocultures depending on the stimulating agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Purified SEB and TSST-1 were obtained from Toxin Technology (Sarasota, Fla.). LPS (Escherichia coli 055:B5) was obtained from Difco (Detroit, Mich.). Human recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2), rIL-6, rIL-8, and rIFN-γ were obtained from Collaborative Research (Bedford, Mass.). Human rMCP-1, rMIP-1α, rMIP-1β, rIP-10, rRANTES, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IRA), anti-IL-1β, anti-IL-8, anti-TNF-α, anti-MIP-1α, and anti-MIP-1β were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.). Anti-IL-1β, anti-IL-6, and anti-RANTES were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, Ill.). Anti-IL-2, anti-IFN-γ, anti-MCP-1, and anti-IP-10 were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). Anti-intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) was obtained from Biosource International (Camarillo, Calif.) and AMAC (Westbrook, Maine), respectively. Human rTNF-α, peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G and peroxidase-conjugated anti-goat immunoglobulin G were obtained from Boehringer-Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.). Human rIL-1β was generously provided by J. Oppenheim (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md.). All other common reagents were from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.).

Cell cultures.

PBMC were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation of heparinized blood from normal human donors. PBMC were plated at 106 cells/ml in 24-well plates in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (culture medium). Cells were stimulated with SEB (50 ng/ml) or TSST-1 (50 ng/ml) or LPS (100 ng/ml) for 16 h. Supernatants were harvested and analyzed for cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-2, and IFN-γ) and chemokines (MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, IL-8, and IP-10) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Human A549 cells, a type II alveolar epithelial cell line, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). A549 cells were grown in cell culture flasks in RPMI 1640 culture medium. Nonstimulated epithelial cell culture supernatant did not contain suppressive factors that would influence T-cell responses. Cells were plated at 2 to 2.5 × 105/ml in 24-well plates in culture medium and were grown for 6 to 16 h to confluence. PBMC and pulmonary epithelial A549 cells were cocultured by adding 106 PBMC/ml to the A549 cells plated as described above. Cocultures were stimulated with SEB (50 ng/ml) or TSST-1 (50 ng/ml) or LPS (100 ng/ml) for 16 h. Supernatants of cocultures were harvested and analyzed for cytokines and chemokines. In some cocultures of PBMC and A549 cells, A549 cells were fixed with ice-cold ethanol and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before adding PBMC and stimulants. To physically separate PBMC and A549 cells, PBMC were added to Transwell (Costar) with inserts with A549 cells in the lower compartment.

Cytokine/chemokine assays.

All cytokines and chemokines in culture supernatants from PBMC or PBMC-A549 cocultures were measured by sandwich ELISA as previously described (14, 15, 17). Matched antibody pairs for each cytokine or chemokine were used in ELISA for that specific cytokine or chemokine. Human recombinant cytokines/chemokines (20 to 1,000 pg/ml) were used as standards for calibration on each plate. The intra-assay precision was 4 to 6%, and the interassay variability ranged from 6 to 9%. The sensitivity of each assay was 10 pg/ml.

Measurement of cell surface ICAM-1 expression.

ICAM-1 expression on A549 cells was measured by a direct cell ELISA (13). Cells were cultured at 2 to 2.5 × 104/well in 0.1 ml of culture medium in 96-well plates. Cell culture supernatants from PBMC stimulated with SEB, TSST-1, or LPS were tested for their ability to induce ICAM-1 on A549 cells. After stimulation with supernatants or cytokines in quadruplicate for 4 h, cells were fixed with ice-cold ethanol and were washed with wash buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20). Cells were then incubated with mouse anti-human ICAM-1 antibodies in ELISA buffer (PBS supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum) for 40 min at 37°C and were then washed four times with wash buffer. Peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody in ELISA buffer was added, and plate contents were incubated for 20 min at 37°C. Bound enzyme was determined by adding 3,3′,5,5′ -tetramethylbenzidine and hydrogen peroxide.

Statistical analysis.

Data were expressed as the mean± standard deviation and were analyzed for significant difference by Student’s t test with Stata (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.). Differences were considered statistically significant if P was < 0.05.

RESULTS

Cytokine and chemokine production in PBMC and pulmonary epithelial cell cocultures.

Previous studies showed that staphylococcal superantigens induce high levels of the cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-γ, as well as of the chemokines MCP-1, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β from PBMC (11, 14, 17, 24). Table 1 shows the levels of cytokines and chemokines produced by PBMC in response to SEB (50 ng/ml), TSST-1 (50 ng/ml), or LPS (100 ng/ml). The production of these mediators varied considerably among donors. LPS-stimulated PBMC produced the same cytokines and chemokines as SEB- or TSST-1-stimulated PBMC, with the exception of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IP-10. Similar results were obtained with PBMC from another 10 normal donors stimulated with a different concentration of SEB, TSST-1, and LPS (150 ng/ml). In contrast, no cytokine or chemokine was released from pulmonary A549 epithelial cells incubated with SEB, TSST-1, or LPS (data not shown), in agreement with the observations of other investigators (25).

TABLE 1.

Cytokine and chemokine profile of PBMC supernatantsa

| Cytokine or chemokine | Level of cytokine or chemokine (pg/ml) produced by PBMC in response to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEB | TSST-1 | LPS | |

| IL-1β | 100 ± 87 | 61 ± 37 | 643 ± 83 |

| TNF-α | 1,263 ± 343 | 847 ± 356 | 1,591 ± 1,052 |

| IL-6 | 145 ± 93 | 227 ± 155 | 585 ± 121 |

| IFN-γ | 2,054 ± 1,283 | 862 ± 427 | 12 ± 11 |

| IL-2 | 1,582 ± 464 | 637 ± 226 | 2 ± 1 |

| MCP-1 | 1,435 ± 718 | 1,018 ± 971 | 1,452 ± 1,940 |

| MIP-1α | 1,880 ± 1,386 | 1,889 ± 1,695 | 7,931 ± 3,600 |

| MIP-1β | 1,874 ± 650 | 1,751 ± 579 | 1,817 ± 849 |

| RANTES | 960 ± 722 | 794 ± 693 | 1,076 ± 732 |

| IL-8 | 8,155 ± 4,040 | 9,826 ± 4,443 | 15,598 ± 6,850 |

| IP-10 | 3,448 ± 3,184 | 5,037 ± 3,204 | 20 ± 11 |

Data represent mean ± standard deviation of data from four to seven donors. Standard deviation indicates differences in cytokine and chemokine levels among donors. Background levels with medium only were negligible in comparison to levels found in stimulated cell cultures, except for MIP-1β, RANTES, and IL-8, with background levels of 452 ± 325, 200 ± 159, and 1,957 ± 1,196, respectively.

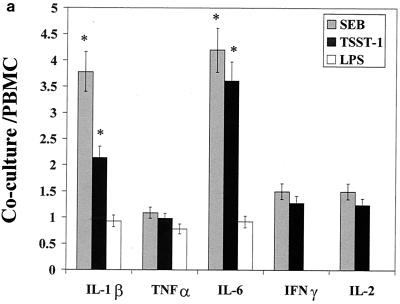

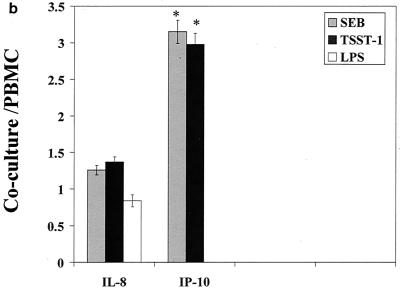

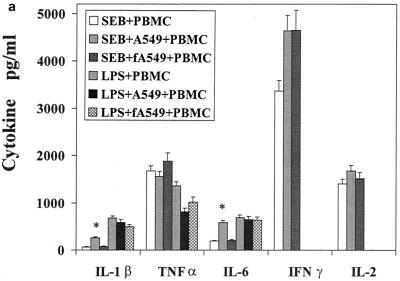

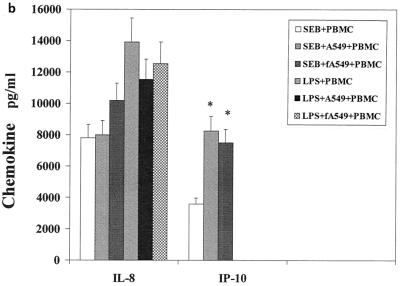

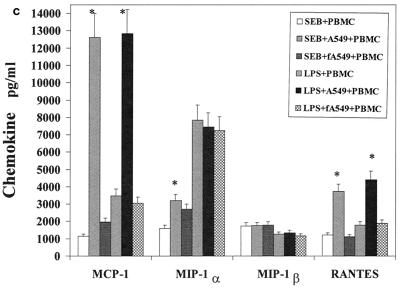

The influence of the interaction of PBMC and pulmonary A549 epithelial cells in regard to the release of these immunological mediators was also examined. Confluent monolayers of A549 were cocultured with PBMC in the presence of SEB, TSST-1, or LPS. The cytokines and chemokines produced in these cocultures were measured and compared to those produced by PBMC stimulated with SEB, TSST-1, or LPS. Their difference was expressed as a ratio of the amount of cytokine produced by stimulated coculture to the amount of cytokine produced by stimulated PBMC (Fig. 1a to c). Interaction of PBMC with A549 cells up-regulated SEB-induced IL-1β, IL-6, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and RANTES by 3.8-, 4.2-, 3.1-, 8.9-, 2-, and 2.9-fold, respectively (P < 0.05). IFN-γ and IL-2 levels were slightly but not significantly increased, by 1.5- and 1.4-fold (P < 0.08), respectively. TSST-1-stimulated cocultures also showed similar increases in these cytokines and chemokines. However, in LPS-stimulated cocultures, only MCP-1 and RANTES were increased (by 5.2- and 3.6-fold, respectively; P < 0.05). In contrast, TNF-α, IL-8, and MIP-1β levels were unchanged in cocultures compared with levels in PBMC whether SEB, TSST-1, or LPS was used. Thus, dramatic increases occurred in the levels of MCP-1 and RANTES, regardless of whether SEB, TSST-1, or LPS was used as the inducing agent. But the modulation of IL-1β, IL-6, IP-10, and MIP-1α was completely stimulant dependent, with SE causing an up-modulation and LPS resulting in unchanged levels of these mediators.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of cytokine and chemokine levels in cocultures of PBMC and pulmonary A549 cells with PBMC in response to SEB (50 ng/ml), TSST-1 (50 ng/ml), and LPS (100 ng/ml). The y axis represents the ratio of cytokines produced in cocultures to those produced by PBMC stimulated with the same agent. Values are the means of ratios ± standard deviations obtained from five donors. A ratio of 1 corresponds to equal amounts of cytokine in cocultures and PBMC. *, statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between stimulant-treated cocultures and stimulant-treated PBMC.

Because IFN-γ is a potent activator of antigen-presenting cells and epithelial cells, its presence in SE-stimulated PBMC supernatant but not in LPS-stimulated supernatant may account for some of these differences. To address this issue, A549 epithelial cells were pretreated with 100 U of IFN-γ/ml and were then cocultured with PBMC in the presence of LPS. The same profile of cytokines and chemokines was observed as that obtained for LPS-stimulated cocultures without IFN-γ (data not shown). Addition of IFN-γ directly to LPS-stimulated cocultures also failed to change this profile. Anti-IFN-γ added to cocultures stimulated with SEB also did not result in changes in the cytokine and chemokine profile in cocultures. Thus, the presence of IFN-γ in superantigen-activated PBMC is unlikely to account for the differences observed between superantigen- and endotoxin-stimulated cocultures.

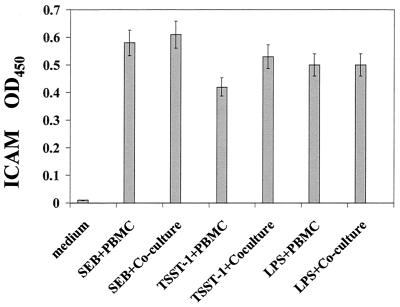

Cell surface expression of ICAM on pulmonary A549 epithelial cells in response to conditioned medium.

To explore the possibility that cytokines in supernatants of SE- and LPS-stimulated PBMC stimulate epithelial cell surface costimulatory molecules which would facilitate interaction with PBMC, conditioned medium from PBMC was used to stimulate A549 cells directly. Because of the role that ICAM plays in both cell adhesion and costimulation, the ability of supernatants from SEB-, TSST-1, or LPS-stimulated PBMC cultures to directly regulate ICAM expression on A549 cells was investigated. Addition of conditioned medium from SEB-, TSST-1- and LPS-stimulated PBMC resulted in similar increases in ICAM expression (Fig. 2). Thus, the ability of supernatants from SEB-, TSST-1-, and LPS-stimulated PBMC to affect ICAM expression on A549 was the same, independent of the stimulant used.

FIG. 2.

ICAM expression in pulmonary A549 cells stimulated with conditioned medium from SEB-, TSST-1-, and LPS-stimulated PBMC. Data are mean ± standard deviation of quadruplicate cultures. Results are representative of three experiments. OD450, optical density at 450 nm.

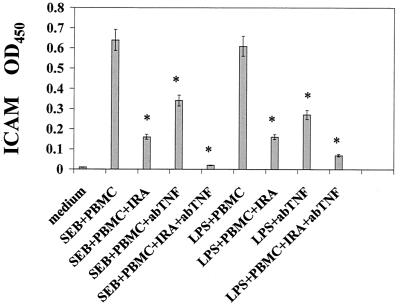

The up-regulation of ICAM expression on A549 cells induced by conditioned medium was further investigated to determine which cytokines were responsible for this effect. Previous studies indicate that IL-1 and TNF-α are potent stimulants for the expression of ICAM on many cell types (16, 26, 31). Figure 3 shows that adding IRA or anti-TNF-α reduced ICAM expression by 74 and 56%, respectively, in A549 cells treated with supernatants from SEB-stimulated PBMC. Similar inhibition of ICAM expression was observed on A549 cells treated with conditioned medium from LPS-stimulated PBMC. ICAM expression was inhibited completely when IRA and anti-TNF-α were added together, which demonstrated synergy of IL-1 and TNF-α in the up-modulation of ICAM surface expression on A549 lung epithelial cells.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of ICAM expression in pulmonary A549 cells stimulated with conditioned medium from SEB-, TSST-1-, and LPS-stimulated PBMC. IL-1 receptor antagonist (IRA) and anti-TNF-α were added at 50 ng/ml and 10 μg/ml, respectively. Data are mean± standard deviation of quadruplicate cultures. Results are representative of two experiments. *, statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between stimulant-treated PBMC and stimulant-treated PBMC plus the reagents (IRA, anti-TNF-α, or IRA and anti-TNF-α) indicated. OD450, optical density at 450 nm.

Cytokine and chemokine profiles in cocultures with fixed A549 cells.

Transwell plates were used to physically separate PBMC and pulmonary A549 cells to determine if cell contact was necessary for this modulation to occur. However, the cytokine and chemokine levels in SEB- or LPS-stimulated cocultures did not differ from those of SEB- or LPS-stimulated PBMC without A549 when Transwell plates were used (data not shown). This result suggests a requirement for cell-to-cell contact between PBMC and A549 cells in modulating the changes in cytokines and chemokines shown in Fig. 1a to c.

Fixed A549 epithelial cells were used to examine whether pulmonary epithelial cells produce these cytokines and chemokines in SEB- or LPS-stimulated PBMC-A549 cocultures. The increase in IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and RANTES levels seen in SEB- and TSST-1-stimulated coculture was not observed when PBMC were cocultured with fixed A549 (Fig. 4). TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-8, IP-10, and MIP-1α levels remained the same whether fixed A549 or“metabolically active” A549 cells were used in cocultures. These results suggest that PBMC is the source of some of these cytokines and chemokines and that the up-modulation of IP-10 and MIP-1α from SEB-stimulated coculture depends on physical contact between PBMC and A549 epithelial cells.

FIG. 4.

Levels of cytokine and chemokine in PBMC, cocultures of PBMC and pulmonary A549 cells, and cocultures with fixed A549 cells. Values shown represent mean ± standard deviation of quadruplicate cultures. Results are representative of two experiments. *, statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between stimulant-treated cocultures and stimulant-treated PBMC.

DISCUSSION

The results presented indicate that LPS and SEB and TSST-1 activated PBMC-pulmonary epithelial cell cocultures differentially. Interaction of PBMC and pulmonary epithelial cells activated PBMC and epithelial cells bidirectionally and was stimulus dependent. Contact of PBMC with pulmonary epithelial cells differentially regulated the production of cytokines and chemokines, with SE having a stimulatory effect on IL-1β, IL-6, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and RANTES release, whereas LPS resulted in increases of MCP-1 and RANTES in these cocultures. Direct signaling between activated PBMC and otherwise unresponsive epithelial cells to SE and LPS may amplify local immune responses to SE and LPS in different ways, depending on the insulting stimulus. Because cytokines modulate pathological processes and contribute to tissue injury and disease pathogenesis, the cells that produce these cytokines are critical targets for therapeutic modulation. Thus, although PBMC may participate in host immune defenses by cytokine and chemokine production, pulmonary epithelial cells also play a pivotal role as a first line of defense against invading pathogens. No release of cytokine or chemokine from A549 was observed when these epithelial cells were stimulated directly with LPS or SE. Therefore, direct exposure of pulmonary epithelial cells to microbial products does not appear to be a significant source of proinflammatory mediators. Interestingly, T lymphocytes associated with mucosal sites are less responsive towards SE, as lamina propria lymphocytes and intraepithelial lymphocytes produce negligible amounts of IFN-γ and IL-6 when stimulated with SEB and TSST-1 (29). Conditioned medium from PBMC cultures containing cytokines stimulated pulmonary epithelial cells to increase adhesion receptors, such as ICAM, in agreement with previous studies (26, 33). This mode of activation was nonspecific, as conditioned medium from LPS- or SE-stimulated PBMC induced the same level of ICAM expression. However, the cytokine and chemokine release from cells in PBMC and epithelial cell coculture was differentially regulated depending on the stimulus. Thus, SE generated mostly an up-modulation of cytokines and chemokines, whereas LPS caused the specific increase in MCP-1 and RANTES only. These changes are cell dependent, as direct cell contact is required for the differential modulation in SE- or LPS-stimulated cocultures.

Other in vitro coculture systems have also been used to investigate the interaction between immune cells and epithelial cells or fibroblasts (9, 19). SEB-stimulated PBMC caused a rearrangement of epithelial transport and barrier functions when cocultured with an intestinal epithelial cell line (19). The present findings complement published reports supporting the role of IL-1 and TNF-α in the modulation of epithelial cell surface expression of ICAM (26). However, the new evidence of bidirectional modulation of cytokines and chemokines induced in response to SE or LPS by PBMC and pulmonary epithelial cells presented here indicates that activating signals from pulmonary epithelial cells may further potentiate inflammatory reactions in the lung and in PBMC. The concomitant stimulation by cell surface and secreted products of activated PBMC and pulmonary epithelial cells represents targets for immunomodulation.

It is difficult to dissect the adhesive events and the early cytokine cascades in modulating the levels of individual cytokines because of the propensity of both PBMC and A549 cells to produce these mediators. ICAM is an adhesion receptor present in many cell types, including monocytes, T cells, and epithelial cells (29). The use of ICAM as a costimulatory molecule is also well documented (30, 33).

Since the chemokines IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and RANTES have a costimulatory role in T-cell activation, their increased production in these cocultures could lead to further augmentation of T-cell activation. These chemokines are also chemotactic for monocytes, T cells, and eosinophils and can induce migration of these cells to the lung. The present findings indicate that cellular interaction of PBMC and pulmonary epithelial cells is bidirectional and that the differential modulation of cytokines and chemokines is stimulus dependent.

This cross talk and costimulation between cell types may then control subsequent steps in the immune response by activating T cells, neutrophils, natural killer cells, and eosinophils. A cytokine network represents one mechanism of communication between PBMC and epithelial cells. Cell contact represents another form of signaling, resulting in differential cytokine and chemokine release that is stimulus dependent and therefore much more specific to the insulting agent.

Acknowledgments

I thank Marilyn Buckley for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacon, K. B., B. A. Premack, P. Gardner, and T. J. Schall. 1995. Activation of dual T cell signaling pathways by the chemokine RANTES. Science 269:1727–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bokoch, G. M. 1995. Chemoattractant signaling and leukocyte activation. Blood 86:1645–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brigham, K. L., and B. Meyrick. 1986. Endotoxin and lung injury. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 133:913–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi, Y., B. Kotzin, L. Hernon, J. Callahan, P. Marrack, and J. Kappler. 1989. Interaction of Staphylococcus aureus toxin “superantigens” with human T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:8941–8945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denis, M., L. Guojian, M. Widmer, and A. Cantin. 1994. A mouse model of lung injury induced by microbial products: implications of tumor necrosis factor. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 10:658–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diamond, G., D. Legarda, and L. K. Ryan. 2000. The innate immune response of the respiratory epithelium. Immunol. Rev. 173:27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gascoigne, N. R. J., and R. T. Ames. 1991. Direct binding of secreted TCR β chain to superantigen associated with MHC class II complex protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:613–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herz, U., R. Ruckert, K. Wollenhaupt, T. Tschernig, M. Neuhaus-Steinmetz, R. Pabst, and H. Renz. 1999. Airway exposure to bacterial superantigen (SEB) induces lymphocyte-dependent airway inflammation associated with increased airway responsiveness—a model for non-allergic asthma. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogaboam, C. M., N. W. Lukacs, S. W. Chensue, R. M. Strieter, and S. L. Kunkel. 1998. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 synthesis by murine lung fibroblasts modulates CD4+ T cell activation. J. Immunol. 160:4606–4612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingalls, R. R., H. Heine, E. Lien, A. Yoshimura, and D. Golenbock. 1999. Lipopolysaccharide recognition, CD14, and lipopolysaccharide receptors. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 13:341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jupin, C., S. Anderson, C. Damais, J. E. Alouf, and M. Parant. 1988. Toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 as an inducer of human tumor necrosis factors and gamma interferon. J. Exp. Med. 167:752–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotzin, B. L., D. Y. M. Leung, J. Kappler, and P. A. Marrack. 1993. Superantigens and their potential role in human disease. Adv. Immunol. 54:99–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krakauer, T. 1995. A sensitive ELISA for measuring the adhesion of leukocytic cells to human endothelial cells. J. Immunol. Methods 177:207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krakauer, T. 1995. Inhibition of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1-induced cytokine production and T cell activation by interleukin-10, interleukin-4, and dexamethasone. J. Infect. Dis. 172:988–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krakauer, T. 1998. Variability in the sensitivity of nine ELISAs in the measurement of human interleukin 6. J. Immunol. Methods 219:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krakauer, T., J. Vilcek, and J. J. Oppenheim. 1998. Proinflammatory cytokines: TNF and IL-1 families, chemokines, TGFβ and others, p.775–811. In W. Paul (ed.), Fundamental immunology, 4th ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 17.Krakauer, T. 1999. Induction of CC chemokines in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by staphylococcal exotoxins and its prevention by pentoxifylline. J. Leukoc. Biol. 66:158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luster, A. D. 1998. Chemokines—chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKay, D. M., and P. K. Singh. 1997. Superantigen activation of immune cells evokes epithelial (T84) transport and barrier abnormalities via IFN-γ and TNFα: inhibition of increased permeability, but not diminished secretory responses by TGF-β2. J. Immunol. 159:2382–2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medzhitov, R., P. Preston-Hurlburt, and C. A. Janeway. 1997. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature 388:394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miethke, T., C. Wahl, K. Heeg, B. Echtenacher, P. H. Krammer, and H. Wagner. 1992. T cell-mediated lethal shock triggered in mice by the superantigen SEB: critical role of TNF. J. Exp. Med. 175:91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison, D. C., and J. L. Ryan. 1987. Endotoxins and disease mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Med. 38:417–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neumann, E., B. Engelhardt, H. Wagner, and B. Holzmann. 1997. Induction of acute inflammatory lung injury by staphylococcal enterotoxin B. J. Immunol. 158:1862–1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsonnet, J., R. K. Hickman, D. D. Eardley, and G. B. Pier. 1985. Induction of human interleukin-1 by toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. J. Infect. Dis. 151:514–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rennard, S. I., D. J. Romberger, J. H. Sisson, S. G. Von Essen, I. Rubinstein, R. A. Robbins, and J. R. Spurzem. 1994. Airway epithelial cells: functional roles in airway disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 150:S27–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothlein, R., M. Czajkowski, M. M. O’Neill, S. D. Marlin, E. Mainolfi, and V. J. Merluzzi. 1988. Induction of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 on primary and continuous cell lines by pro-inflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 141:1665–1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlievert, P. M. 1993. Role of superantigens in human disease. J. Infect. Dis. 167:997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scholl, P., A. Diez, W. Mourad, J. Parsonnet, R. S. Geha, and T. Chatila. 1989. Toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 binds to major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:4210–4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sperber, K., L. Silverstein, C. Brusco, C. Yoon, G. E. Mullin, and L. Mayer. 1995. Cytokine secretion induced by superantigens in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, lamina propria lymphocytes, and intraepithelial lymphocytes. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2:473–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Springer, T. A. 1990. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature 346:425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Standiford, T. J., S. L. Kunkel, M. A. Basha, S. W. Chensue, J. P. Lynch, G. B. Toews, J. Westwick, and R. M. Strieter. 1990. IL-8 gene expression by pulmonary epithelial cell line: a model for cytokine networks in the lung. J. Clin. Investig. 86:1945–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulevitch, R. J., and P. S. Tobias. 1995. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13:437–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wegner, C. D., R. H. Gundel, P. Reilly, N. Haynes, L. G. Letts, and R. Rothlein. 1990. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in the pathogenesis of asthma. Science 247:456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]