Abstract

The ability of the Luminex system to simultaneously quantitate multiple analytes from a single sample source has proven to be a feasible and cost-effective technology for assay development. In previous studies, my colleagues and I introduced two multiplex profiles consisting of 20 individual assays into the clinical laboratory. With the Luminex instrument’s ability to classify up to 100 distinct microspheres, however, we have only begun to realize the enormous potential of this technology. By utilizing additional microspheres, it is now possible to add true internal controls to each individual sample. During the development of a seven-analyte serologic viral respiratory antibody profile, internal controls for detecting sample addition and interfering rheumatoid factor (RF) were investigated. To determine if the correct sample was added, distinct microspheres were developed for measuring the presence of sufficient quantities of immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgM in the diluted patient sample. In a multiplex assay of 82 samples, the IgM verification control correctly identified 23 out of 23 samples with low levels (<20 mg/dl) of this antibody isotype. An internal control microsphere for RF detected 30 out of 30 samples with significant levels (>10 IU/ml) of IgM RF. Additionally, RF-positive samples causing false-positive adenovirus and influenza A virus IgM results were correctly identified. By exploiting the Luminex instrument’s multiplexing capabilities, I have developed true internal controls to ensure correct sample addition and identify interfering RF as part of a respiratory viral serologic profile that includes influenza A and B viruses, adenovirus, parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, and 3, and respiratory syncytial virus. Since these controls are not assay specific, they can be incorporated into any serologic multiplex assay.

The Luminex (Austin, Tex.) Multi-Analyte Profiling (LabMAP) technology is based on microscopic polystyrene particles called microspheres that are internally labeled with two different fluorophores. When excited by a 635-nm laser, the fluorophores emit light at different wavelengths, 658 and 712 nm. By varying the 658-nm/712-nm emission ratios, an array of up to 100 different fluorescent profiles has been created. Using precision fluidics, digital signal processors, and advanced optics, the unique Luminex 100 analyzer classifies each microsphere according to its predefined fluorescent emission ratio. Thus, multiple microspheres coupled to different analytes can be combined in a single sample. A third fluorophore coupled to a reporter molecule allows for quantitation of the interaction that has occurred on the microsphere surface.

The Luminex 100 system has been shown to be a feasible and cost-effective technology for assay development. Our institute has validated two multiplex assays for use in the clinical laboratory, one that includes a profile of six cytokines and one that includes a profile of pneumococcal antibodies of 14 different serotypes (J. W. Pickering, T. B. Martins, R. W. Greer, M. C. Schroder, M. E. Astill, C. M. Litwin, and H. R. Hill, submitted for publication). Other published applications of the current Luminex format include analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (5, 8) and mutation screening (1). With the Luminex instrument’s ability to classify up to 100 distinct microspheres, we now have the ability to add true internal controls to determine correct sample and reagent addition, identify interfering substances such as heterophile antibodies (7) and rheumatoid factors (RFs), and monitor instrument performance parameters. During the development of a seven-analyte serologic viral respiratory profile, internal controls were investigated to determine if the correct sample was added and if interfering RF was present in the sample. When reporting negative results, a concern among technicians in a clinical laboratory is whether the patient sample was actually added to the reaction mixture. The patient sample may be left out of the reaction mixture due to human or automated instrument pipetting errors, sample clots, or other factors. These sampling errors generally go undetected in standard laboratory assays. Because of the multiplexing ability of the Luminex, true internal controls for the validation of sample addition can now be added to each individual well or reaction. To accomplish this, a goat anti-human immunoglobulin M (IgM) or anti-human IgG antibody is coupled to a specific microsphere that can be added to IgM- or IgG-specific serologic assay panels. This coupled microsphere then binds IgM or IgG isotypes present in the patient’s serum. If the patient sample is present, it will be detected by the anti-human IgM or IgG reporter conjugate, generating a semiqualitative result.

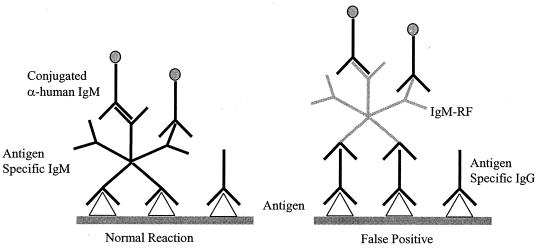

A second control was developed to detect significant levels of interfering IgM RFs. RFs represent one of the most serious problems in IgM testing (3). RFs are autoimmune antibodies, usually of the IgM class, which recognize human IgG. In antibody testing, specific IgG present in the serum binds to antigen, presenting a site for the anti-IgG IgM RF to bind. The IgM is then recognized by the labeled anti-IgM conjugate, giving rise to a false-positive result (Fig. 1). Traditional enzyme immunoassay (EIA) methods for IgM antibody testing typically employ an absorbent in the serum diluent consisting of a goat anti-human IgG antibody to minimize potential RF IgM interference. In our assay, an RF control was developed by coupling human IgG to a specific Luminex microsphere. If RFs are present in the patient sample, they will bind to the human IgG. The reporter anti-human IgM antibody added next to detect specific respiratory viral IgM antibodies will also detect the potentially interfering IgM RFs.

FIG. 1.

False-positive reaction caused by RF interference.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Coupling of microspheres.

A Luminex multiplex panel of nine analytes, including seven viral antigens and two internal controls, was developed. Partially purified antigens for adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza A virus (Flu A), influenza B virus, and parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, and 3 were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, Calif.) and BioWhittaker (Walkersville, Md.) and covalently coupled to carboxylated Luminex microspheres. For the sample addition control, 1 μg of goat anti-human IgG (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml or 5 μg of goat anti-human IgM (Sigma Chemical) per ml was coupled to specific microspheres. The interfering RF control was developed (6) by coupling 50μg of human IgG (Sigma Chemical) per ml to another microsphere. Coupling of the antigens or antibodies to the carboxylated microspheres was accomplished using a two-step carbodiimide reaction (4). Carboxylated microspheres were activated for 20 min at 6.25 × 106/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 6.1) with 5 mg each of 1-ethyl-3(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide-HCL and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) per ml. Activated microspheres were then washed by centrifugation with PBS, pH 7.2, and incubated with the previously described antigens and antibodies for 1 h at room temperature on a rocker. The coupled microspheres were then washed twice with PBS (pH 7.2)-0.05% Tween 20 and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS (pH 7.2)-0.1% bovine serum albumin-0.05% sodium azide. The microspheres were then incubated for 30 min on a rocker to allow blocking of the unreacted sites and stored at 4°C in the PBS-bovine serum albumin-sodium azide mixture.

Luminex-multiplexed IgG and IgM serology assays.

The nine different analyte-coupled microspheres were mixed together at a concentration of 1.0 × 105 copies of each microsphere/ml. Fifty microliters of the microsphere mixture was added to 100 μl of diluted serum (1:100 in PBS-Tween 20) for a final concentration of 5,000 copies of each individual microsphere (45,000 total) per reaction. Serum samples and microspheres were incubated for 20 min at room temperature using a 96-well microtiter plate on a shaker. This was followed by the addition of 50 μl of R-phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human IgG or IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) to each well of the microtiter plate. Following a second 20-min incubation on the shaker, the microtiter plate was placed in a Luminex 100 instrument with an XY platform (automated microtiter plate handler), on which the microspheres were counted and analyzed. The amount of antibody bound to the microspheres was determined with anti-human IgG or IgM conjugated to phycoerythrin. When the microspheres were excited at a wavelength of 532 nm, phycoerythrin emited light at a wavelength of 575 nm. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) at 575 nm is directly proportional to the amount of antibody bound to the microspheres. Since the analyte specificity and position of each bead classification in the array are known, a single fluorescent reporter molecule can be used to measure antibody levels for all nine microspheres.

For the serum addition validation control, a calibrator was established to identify patient samples with less than 20 mg of IgM antibody per dl. The normal range for total IgM for individuals 10 years and older is 60 to 253 mg/dl. A semiquantitative result was then established using the calibrator, in which a value of 20 IgM units (MU) equals 20 mg of IgM antibody per dl. The calibrator was created by diluting normal human serum with bovine serum albumin until a value of 20 mg/dl was obtained by my standard nephelometric quantitative method.

For the RF interference control, a calibrator was created by pooling an RF IgM-positive serum sample with RF-negative blood bank serum samples until a value of 10 IU/ml was obtained based on a commercial EIA method (Zeus Scientific, Raritan N.J.). By dividing the Luminex MFI value of the unknown sample by the calibrator, an index value (IV) was established to identify any samples containing >10 IU of RF IgM (IV, 1.0 or greater) per ml as having potentially interfering concentrations of RF.

A calibrator for the serologic viral respiratory immunoassays was developed by pooling slightly positive serum samples. The reactivities of the calibrator and serum samples used in this study were determined with commercially available IgM-specific viral respiratory EIA kits obtained from Immuno-Biological Laboratories (Stuttgart, Germany) and by in-house complement fixation assays. The MFI value obtained by the Luminex technology for the patient sample was divided by the MFI value of the calibrator to calculate an IV. An IV of 1.0 or greater indicated that significant concentrations of IgM antibody to the specific viral antigen were detected, and the result was considered positive. An IV of less than 1.0 was considered negative.

RESULTS

For the serum addition validation control, the established calibrator was used to identify patient samples with less than 20 mg of IgM antibody per dl. Eighty-two patient samples were tested on the Luminex as part of a nine-analyte multiplex IgM serological assay, which included the seven viral respiratory antigens and two internal controls. Fifty-nine of the 82 patient samples were reported as valid or acceptable for the presence of at least 20 mg of IgM antibody per dl, indicating that the correct sample (serum) was submitted and that the sample was diluted correctly. Twenty-three of the 82 samples were identified as having low concentrations (<20 mg/dl) of IgM antibody. A breakdown of these 23 samples that did not meet the minimum IgM antibody concentrations was as follows: 1 sample received no serum in the sample dilution; 2 samples were incorrectly pipetted, receiving only 1/10 of the required sample volume; 1 sample was normal serum with the IgM previously removed; 4 samples were the wrong sample type, namely, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which normally contains less than 1 mg of IgM antibody per dl; 2 were from infants less than 1 month old (normal range, 0 to 24 mg/dl); and 13 were from adults with abnormally low levels (<20 mg/dl) of IgM antibody. A serum validation control for IgG serologic assays was also developed for detecting samples containing less than 400 mg of IgG per dl which performed similarly to the IgM serum control (data not shown). The normal range of IgG for individuals 10 years and older is 768 to 1,632 mg/dl.

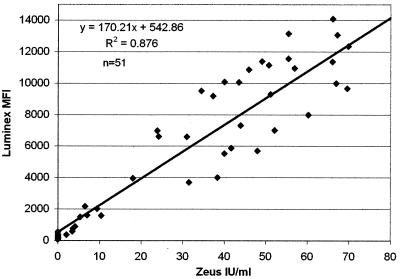

For the development of the RF interference control, the results of 52 samples tested for IgM RF by Luminex were compared to results obtained by the Zeus Scientific EIA method. Overall correlation between the results of the two methods was good (r2 = 0.88) (Fig. 2). More importantly, a clear cutoff range from 2,200 to 4,000 MFI units was observed on the Luminex between negative (<10 IU/ml) and significant (>20 IU/ml) values obtained from the EIA. By using the established calibrator, all samples having an IV of 1.0 or greater (>10 IU/ml of RF IgM) were identified as having potentially interfering concentrations of RF. By including the two internal controls in an IgM serological assay, the following algorithm was established. If the patient sample was reported as negative for IgM antibody to the specific viral respiratory antigens, then the value of the serum addition control was checked. If the value was over 20 MU, then it was assumed that the sample type and dilution were correct and that the negative result was valid. If the value for the serum addition control was less than 20 MU, then the negative IgM result was suspect, the sample type and age of the patient were investigated, and the testing of the sample was repeated, if warranted. If the patient sample result was positive for IgM antibodies to any of the seven specific viral respiratory antigens, then the value of the RF interference control was examined. If the RF interference control had an IV of 1.0 or greater, then significant concentrations of interfering RF were present in the sample, indicating that a false-positive reaction may have occurred. These samples were retested using an anti-human IgG absorbent in the sample diluent to prevent IgM RF binding. If the repeated sample result remained positive, then a positive IgM result was reported for the specific viral antigen(s).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of results of 52 samples tested for RF IgM by the Luminex assay and a commercial EIA. Zeus IU, international units as determined by the Zeus EIA.

From a multiplex IgM assay including the seven viral antigens and two internal controls, the results for adenovirus, the serum validation control, and an RF interference control are shown in Table 1. Two samples, 2 and 6, which were adenovirus IgG positive and IgM negative by EIA, were run under normal conditions and spiked with RF. In the initial multiplex run, the two normal IgM sera were negative for adenovirus IgM antibodies, with IVs of 0.4 for sample 2 and 0.8 for sample 6 (with an IV of 1.0 or greater being positive), while the same two samples spiked with RF gave positive results (IVs of 3.0 and 2.3, respectively). The positive RF interference control IV of 4.8 for both of the RF-spiked samples indicates that the positive results of 3.0 and 2.3 for the adenovirus samples may not have been true-positive results but rather false-positive results caused by interfering RF. The serum IgM control values of greater than 20 MU confirm that the reactions received an adequate amount of serum. When these same samples were absorbed with an anti-human IgG diluent and retested, the results for the normal adenovirus samples remained negative (both had an IV of 0.2), while RF-spiked samples changed from positive (IVs, 3.0 and 2.3) to negative (IV for both, 0.1). This shows that the diluent was effective in eliminating the IgG to which the RF was binding. The serum IgM control values confirm that sample was added to the reaction mixture but that, because of the lower values for IgM, the anti-human IgG diluent removed some of the IgM from the sample.

TABLE 1.

Results from a multiplex IgM assay including seven viral respiratory analytes and two internal controls showing initial and absorbed results for adenovirus, an RF interference control, and a serum addition control

| Sample | Initial multiplex run

|

Absorbed with anti-IgG diluent

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus IVa | RF control IVb | Serum IgM control (MU)c | Adenovirus IV | Serum IgM control (MU) | |

| 2 (adenovirus IgG+, IgM−) | 0.4 (−) | 0.5 (−) | 43 | 0.2 (−) | 33 |

| 6 (adenovirus IgG+, IgM−) | 0.8 (−) | 0.1 (−) | 41 | 0.2 (−) | 31 |

| 2 (spiked with RF) | 3.0 (+) | 4.8 (+) | 52 | 0.1 (−) | 35 |

| 6 (spiked with RF) | 2.3 (+) | 4.8 (+) | 52 | 0.1 (−) | 35 |

IVs of >1.0 were considered positive (see symbols in parentheses).

An IV of 1.0 ≈ 10 IU of IgM per ml.

20 MU ≈ 20 mg of IgM antibody per dl.

The data shown in Table 2 were taken from the same multiplex assay as described above but show the results with the Flu A antigen-coupled microsphere. Similar to the previous results, samples 6 and 21 were IgM negative for Flu A when they were run under normal conditions (IVs, 0.4 and 0.3, respectively) but had positive results (IVs, 7.1 and 3.8, respectively) when they were spiked with RF. These again were false-positive reactions due to RF interference, which was shown in the absorbed run when the spiked-sample results changed to negative for Flu A (IVs, 0.2 for sample 6 and 0.1 for sample 21). More interesting is sample 27, which was Flu A positive for both IgG and IgM by EIA. When run normally in the initial multiplex run, this sample was positive for Flu A IgM (IV, 5.5) and negative for RF (IV, 0.4). When this same sample was spiked with RF, it gave an even greater Flu A response (IV, 14.3) and was also positive for RF (IV, 4.1). When these samples were run with the absorbent, the normal sample remained Flu A positive (5.1 IV) while the Flu A results for the RF-spiked sample remained positive but the IV dropped from 14.3 to 4.8.

TABLE 2.

Results from a multiplex IgM assay including seven viral repiratory analytes and two internal controls showing initial results and results with an absorbent for Flu A, an RF interference control, and a serum addition control

| Sample | Initial multiplex run

|

Absorbed with anti-IgG diluent

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flu A IVa | RF control IVb | Serum IgM control (MU)c | Adenovirus IV | Serum IgM control (MU) | |

| 6 (Flu A IgG+, IgM−) | 0.4 (−) | 0.0 (−) | 41 | 0.2 (−) | 31 |

| 21 (Flu A IgG+, IgM−) | 0.3 (−) | 0.0 (−) | 36 | 0.1 (−) | 32 |

| 27 (Flu A IgG+, IgM+) | 5.5 (+) | 0.4 (−) | 41 | 5.1 (+) | 33 |

| 6 (spiked with RF) | 7.1 (+) | 4.1 (+) | 52 | 0.5 (−) | 32 |

| 21 (spiked with RF) | 3.8 (+) | 4.8 (+) | 51 | 0.2 (−) | 33 |

| 27 (spiked with RF) | 14.3 (+) | 4.1 (+) | 55 | 4.8 (+) | 33 |

IVs of >1.0 were considered positive (see symbols in parentheses).

An IV of 1.0 ≈ 10 IU of IgM RF per ml.

20 MU ≈ 20 mg of IgM antibody per dl.

DISCUSSION

All clinical diagnostic tests should include sufficient controls to ensure that the assay on a whole is functioning properly. With the multiplexing abilities of the Luminex, it is now possible to add true internal controls to each individual reaction mixture. The presence of controls allows quality control parameters to be established to ensure that each individual reaction has received the correct reagents and is free from known interfering substances.

A semiquantitative serum validation control effectively indicated that sufficient patient serum was added to each well or reaction mixture. In a multiplex assay in which 82 samples were tested, 23 of 23 samples (100%) were correctly identified as having abnormally low levels (<20 mg/dl) of IgM antibody. A serum validation result of >20 MU assures the laboratorian that a patient sample has been added to each individual reaction well. It is also a good indicator that the correct sample type has been submitted for the serologic assay. For assays requiring serum samples, it is often difficult to visually distinguish between serum and CSF. If the sample dilutions are performed by an automated method, there is even less of a chance of detecting an incorrect sample type. It is important to determine the sample type, since reference ranges for CSF have not been established for most serologic assays and these samples are normally run with a disclaimer. By adding anti-human IgG- or IgM-coupled microspheres to multiplex Luminex assays, a simple but effective internal control which utilizes the same secondary reporter antibody as the viral-antigen-specific microspheres was developed. A control for IgG antibody detection for IgG serologic assays was also developed and performed similarly.

Results with a semiquantitative RF control showed good correlation with the results of an EIA (r2 = 0.88), and in a run of samples from 52 patients, the Luminex assay correctly identified 32 of 32 samples (100%) as having elevated or significant levels (>10 IU/ml) of IgM RF. The effectiveness of the assay with the RF control was further shown by spiking viral respiratory serum samples with RF. By testing samples in a standard serum diluent and a diluent containing anti-human IgG as an absorbent, it was possible to distinguish true IgM-positive samples from false-positive samples caused by interfering RF. Testing patient samples directly for the presence of RF has several advantages over the traditional serologic method of treating all samples with an anti-human IgG absorbent. Commercial IgG absorbents are expensive, adding to the cost $1.75 to $2.50 per patient sample. The cost of adding an RF control on the Luminex is less than $0.25 per sample. Since only a small percentage of the population possesses IgM RFs, treating every sample with an IgG absorbent adds significantly to the cost of an assay. The IgG absorbents have also been shown to remove as much as 20% of the IgM isotypes from serum samples (2). This could potentially cause false-negative results on low-level IgM-positive samples. Additionally, the Luminex internal RF control provides additional information to the clinician by reporting a semiquantitative result for the presence of IgM RFs rather than trying to indirectly block RF interference with an IgG absorbent.

Even though these internal controls were developed in conjunction with the viral respiratory profile, they are not assay specific. They could, therefore, be incorporated in any serologic multiplex assay to ensure that sufficient serum has been added to the reaction mixture or to determine the presence and possible interference of RF in IgM antibody assays.

The multiplexing ability of the Luminex instrument is proving to be a powerful platform for the development of multiple-analyte profiles which require fewer reagents, a smaller volume of patient sample, and lower costs than those of traditional diagnostic methodologies. By employing additional microspheres as internal controls, quality control parameters can now be included for each individual patient or reaction. Internal controls could be developed to ensure that correct concentrations of each individual reagent (sample, conjugate, substrate) have been added and that patient samples are free from known interfering substances such as RFs, heterophile antibodies, bilirubin, hemolysis, and other substances. Internal controls could also be utilized to increase precision and accuracy by monitoring instrument fluctuations, allowing intra- and interassay normalization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dunbar, S. A. and J. W. Jacobson. 2000. Application of the luminex LabMAP in rapid screening for mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene: a pilot study. Clin. Chem. 46:1498–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martins, T. B., T. D. Jaskowski, C. L. Mouritsen, and H. R. Hill. 1995. An evaluation of the effectiveness of three immunoglobulin G (IgG) removal procedures for routine IgM serological testing. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2:98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meurman, O. H. and B. R. Ziola. 1978. IgM-class rheumatoid factor interference in the solid-phase radioimmunoassay of rubella-specific IgM antibodies. J. Clin. Pathol. 31:483–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staros, J. V., R. W. Wright, and D. M. Swingle. 1986. Enhancement by N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide of water-soluble carbodiimide-mediated coupling reactions. Anal. Biochem. 156:220–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor, J. D., D. Briley, Q. Nguyen, K. Long, M. A. Iannone, M. S. Li, F. Ye, A. Afshari, E. Lai, M. Wagner, J. Chen, and M. P. Weiner. 2001. Flow cytometric platform for high-throughput single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. BioTechniques 30:661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wener, M. H., and M. Mannik. 1997. Rheumatoid factors, p.942–948. In N. R. Rose, E. C. de Macario, J. D. Folds, H. C. Lane, and R. M. Nakamura (ed.), Manual of clinical laboratory immunology, 5th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Willman, J. H., T. B. Martins, T. D. Jaskowski, E. R. Ashwood, H. R. Hill, and C. M. Litwin. 2001. Multiplex screening for heterophile antibodies in patients with indeterminant HIV immunoassay results. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 115:764–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye, F., M. S. Li, J. D. Taylor, Q. Nguyen, H. M. Colton, W. M. Casey, M. Wagner, M. P. Weiner, and J. Chen. 2001. Fluorescent microsphere-based readout technology for multiplexed human single nucleotide polymorphism analysis and bacterial identification. Hum. Mutat. 17:305–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]