ABSTRACT

Objectives

Despite its high prevalence and strong linkages with dangerous health outcomes, research on Adjustment Disorder (AjD) is hindered by lack of diagnostic clarity. AjD is categorized as a stress‐related disorder, highlighting the important role of the stressor(s) on AjD symptom onset and severity. The military community shows increased risk for AjD, and existing tools do not capture the stressors most relevant and appropriate to this unique community. A diagnostic assessment tool developed specifically for this specialized population may provide critical capability to clinical assessment.

Methods

A Delphi method was used to create a military‐specific version of the standard assessment for Adjustment Disorders (ADNM‐20), named ADNM‐20‐MIL. This tool was pilot‐tested in a sample of U.S. Active Duty Service Members (ADSMs) with AjD diagnoses.

Results

Throughout the Delphi process, military‐specific stressors were identified and integrated into the ADNM‐20‐MIL, then refined and validated, ensuring their applicability and relevance to the military context.

Conclusions

The ADNM‐20‐MIL will enable timely diagnosis and targeted treatment for AjD, which remains a highly prevalent and destabilizing diagnosis in ADSMs.

Keywords: adjustment disorder, behavioral health, mental health, military stressors, US military

1. Background/Introduction

Adjustment disorder (AjD) is characterized by challenges in daily functioning stemming from a preceding stressor that exceed what is expected for that stressor (American Psychiatric Association 2022). The requirement for linkage between AjD symptoms and their preceding stressor(s) is one of the main defining characteristics of this diagnosis. However, AjD has only recently been recognized as a stress‐related disorder, alongside other well‐defined disorders such as Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This reclassification occurred with the advent of DSM‐5 and ICD‐10 and their subsequent updates DSM‐5‐TR and ICD‐11 (American Psychiatric Association 2022; World Health Organization 2019). Prior to that recognition, AjD was a stand‐alone diagnosis with ill‐defined boundaries, which resulted in limited clinical and research advancement in this field (Casey 2018; O’Donnell et al. 2019). Understanding that psychiatric diagnoses occur on a continuum, and frequently may share common symptom clusters, it is important to recognize and distinguish various disorders from each other based on specific symptoms, etiology, and trajectories. It is also important to have clear thresholds for when difficulties in response to adversity cross the line toward disease onset and pathology. One way to formalize those distinctions is through psychometrically valid and reliable assessment tools developed to capture each disorder.

As a stress‐related disorder, Adjustment Disorder (AjD) is similar to Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in that all require a preceding stressor which triggers symptom onset (O’Donnell et al. 2016, 2019). However, both ASD and PTSD require that the preceding stressor be traumatic in nature, and both the DSM‐5‐TR and ICD‐11 have clear explanations of what constitutes a traumatic stressor (American Psychiatric Association 2022; World Health Organization 2019). Contrastingly, AjD's preceding stressor event can, but does not have to be, traumatic. This can add to the ambiguity of the AjD diagnosis (Casey 2018). Adjustment Disorder also shares symptoms of distress and impairment in functioning with Depression and Anxiety disorders; yet, neither of these diagnoses explicitly require a preceding stressor (American Psychiatric Association 2022; World Health Organization 2019). While AjD is a common diagnosis, its diagnostic criteria remain nonspecific beyond the requirements of a recent preceding stressful event, excessive preoccupation with that event's impact on one's life, and resultant functioning difficulties (Carta et al. 2009). The absence of precise diagnostic criteria for AjD can be helpful in circumstances where it enables providers to “flag” initial or temporary mental illness when symptom severity does not meet the criteria for other diagnoses, but yet surpasses what would be typically expected (Carta et al. 2009). However, this lack of specificity can also be problematic as it contributes to the ongoing ambiguity of AjD diagnosis. This highlights the need for an AjD‐specific assessment tool that provides diagnostic fidelity by capturing both: the preceding stressor(s) as well as the resultant AjD symptoms.

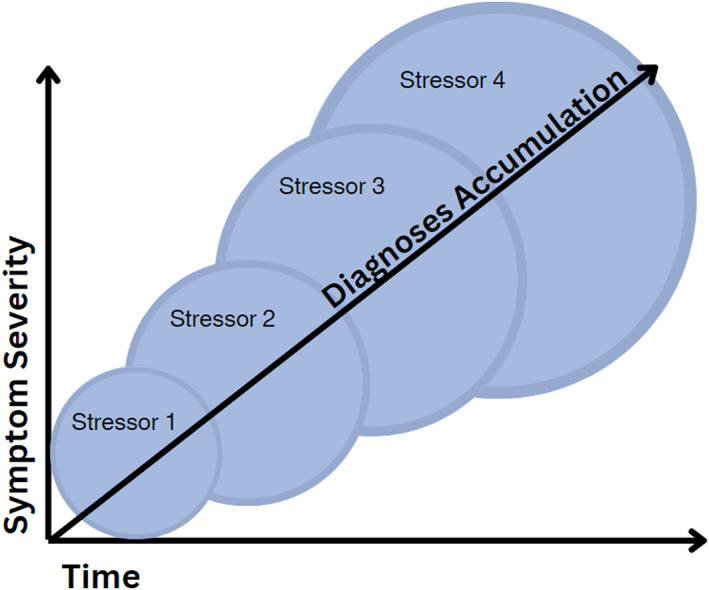

For an AjD diagnosis to apply, the causative stressor must be recent, within one (World Health Organization 2019) to 3 months (American Psychiatric Association 2022), and must cause a reaction that is more intense than what would typically be expected (American Psychiatric Association 2022). By linking stressors and symptoms early‐on, it is possible to identify AjD before an individual naturally accumulates more stressors as functioning deteriorates over time, which then could confound their diagnosis (Figure 1). Although, this time‐linked connection between the causal stressor event and the resulting symptoms is primordial for the AjD diagnosis; we currently know little about this linkage. Current knowledge is also lacking regarding whether specific stressors are more or less likely to be associated with an eventual AjD diagnosis and whether there is a stressor accumulation effect on the eventual setting‐in of AjD symptoms and their severity. While AjD is not necessarily preceded by a traumatic stressor, and cannot be diagnosed if criteria for another mental illness are met, it nevertheless demonstrates a high comorbidity with both suicidality and completed suicide when compared to depressive disorders and other mental health diagnoses (Fegan and Doherty 2019; Casey et al. 2015). This underscores the importance of identifying non‐traumatic stressors and stressful events as impactful contributors to mental health, and treating subsyndromal psychiatric symptoms and maladaptive behaviors quickly.

FIGURE 1.

Stressor accumulation.

Current literature on assessment tools specific for AjD in civilians is emerging with one promising assessment tool that has been found to have strong psychometric properties across multiple civilian populations, the Adjustment Disorder New Module‐20 (ADNM‐20) (Einsle et al. 2010; Zelviene et al. 2017; Lorenz et al. 2016; Bachem et al. 2017). The Adjustment Disorder New Module‐20 (ADNM‐20) is a recently developed assessment tool designed to measure AjD symptoms based on ICD‐11 criteria (Einsle et al. 2010; Zelviene et al. 2017; Lorenz et al. 2016; Bachem et al. 2017). This tool has provided a new and promising approach to identifying and researching AjD because of its unique ability to assess for trigger stressors along with their linkage to AjD‐specific symptoms. While demonstrating good psychometric properties across civilian populations (Zelviene et al. 2017; Bachem et al. 2017; Lorenz et al. 2016), the ADNM‐20 has not yet been tested in the military context and, critically, lacks military‐specific stressors. Studies in military populations have instead used varied diagnostic approaches to examine AjD, with some studies using ICD codes while others using proxies like psychological distress, post‐traumatic stress, or subthreshold Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Bajjani‐Gebara et al. 2021). The U.S. military is a population in which AjD diagnosis, as measured by ICD‐9 or ICD‐10 diagnostic codes, constitutes almost a third of the total incident psychiatric diagnoses across its Army, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Marine Corps branches (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division 2021; Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division 2024). Given that AjD prevalence rates are generally greater in military populations when compared to general civilian populations (Ayuso‐Mateos et al. 2001; Van Wijk 2024), there is an important need for a military‐specific assessment tool that can identify relevant stressors early‐on so that timely and targeted treatment can begin to minimize the potential accumulation of additional stressors and resultant symptom severity over time.

In order to adapt the ADNM‐20 for use in a military population, it was necessary to identify stressors that are specifically applicable to this population. This is complex in the military setting because aspects of the military touch all elements of one's life and getting away from the stressor is not always possible. By virtue of being in the military, active duty service members are encapsulated by military doctrine and requirements, the necessity of unit cohesion, and the importance of working together within the unit to execute the assigned unit's military mission successfully whether in the deployed setting or in garrison. The military is also an innately high‐pressure environment and some level of symptomatic response to its common stressors is not uncommon or inherently debilitating (Chronic Adjustment Disorder Diagnosis and Disposition (CHADD) Working Group and Navy Psychological Health Clinical Community (PHCC) 2020). However, in the U.S. military, AjD's prevalence rate ‐as measured by ICD‐9 or ICD‐10 diagnostic codes‐reached 7.1% in 2017, maintaining its position as the most common mental health diagnosis from 2007 to 2024 (Defense Health Agency (DHA) and Psychological Health Center of Excellence 2017; Stahlman and Oetting 2018) and from 2016 to 2020 (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division 2021, 2024). Research in military populations shows strong associations between AjD and adverse outcomes such as suicides (Bachynski et al. 2012; George et al. 2019; Kochanski‐Ruscio et al. 2014), psychiatric hospitalizations (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC) 2013; Booth‐Kewley and Larson 2005; Freeman and Woodruff 2011; Lindstrom et al. 2006) and AjD‐related evacuations from combat zones (Hall et al. 2024; Goodman et al. 2011). These factors can result in reduced troop numbers and require reallocation of resources necessary for medical evacuations, which may impact military readiness and potentially compromise mission achievement.

This study's aim was to use a Delphi method to identify military‐specific stressors that are relevant to AjD in the military population, develop a military‐specific version of the ADNM‐20 assessment tool, called ADNM‐20‐MIL, and then pilot‐test the resultant ADNM‐20‐MIL. No changes were made to the symptom items of the ADNM‐20 as these are cross‐cutting among various populations.

2. Methods

2.1. Transparency and Openness

This study's design and its analysis were not pre‐registered. Data, analysis code, and research materials are not available.

2.2. Design

A Delphi method was used to develop a military‐specific version of the ADNM‐20, called the ADNM‐20‐MIL. Delphi method is an iterative process used to gain consensus between a group of panelists (Diamond et al. 2014; Nasa et al. 2021). Delphi method panelists are usually selected based on pre‐set criteria that focus on obtaining broad perspectives on general topics, and targeted perspectives on narrower issues (Nasa et al. 2021). In the current study, we employed both approaches. We selected Research Advisory Board (RAB) members to provide broad perspectives on the overall military experience along with Delphi method panelists to provide perspectives specific to mental health care and research within the military.

The currently used Delphi method emphasizes anonymity among participants while delivering controlled feedback between rounds of questionnaires, called Delphi rounds (Nasa et al. 2021). Responses from each round were aggregated and shared with the group between rounds, with the goal of finding consensus for each survey item. Consensus was measured by item‐level content validity index (I‐CVI), which was used to establish concordance between panelists. High I‐CVI values represented both consensus and stability for each survey item in the final round of the Delphi (Polit and Beck 2006; Diamond et al. 2014). While no changes were made to the symptom items of the ADNM‐20 as these are cross‐cutting among various populations, this adaptation targeted the named stressors of the ADNM‐20 to ensure that they were relevant to the military population.

After completion of the above‐described Delphi method to create the ADNM‐20‐MIL, pilot‐testing of the ADNM‐20‐MIL then followed using a different military participant sample‐this time active duty service members with AjD.

All study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Harris et al. 2009, 2019). Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from Uniformed Services University prior to the commencement of the study (IRB number: USUHS.2021‐075). All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations set forth by the IRB. Consistent with the Uniformed Services University IRB, military personnel were free to choose to participate, and could only participate outside of their duty hours.

2.3. Participants

This study consisted of three separate participant groups: both the Research Advisory Board members and the Delphi method members participated in the Delphi method study phase; and the pilot study participants in the pilot study phase as described in the following section. Participants in the Delphi phase, including the Research Advisory Board and military healthcare providers serving as panelists, were unpaid and participated voluntarily. All participants in the pilot phase, consisting of active duty military members with an AjD diagnosis, received compensation for their participation.

2.3.1. Research Advisory Board

A Research Advisory Board composed of six military‐affiliated individuals was assembled to review the current ADNM‐20 and suggest initial modifications to the stressor items of the assessment tool. To ensure diverse military perspectives were included, a study matrix was developed to guide the selection of all RAB members. RAB members were invited from a variety of military branches, positions, and military treatment facility locations. RAB members represented skill sets across the continuum of expertise, to include early, mid, and late career, as well as both retired and active duty service members representing Army, Navy, and Air Force branches. Because the military is a diverse community, special attention was given to ensure racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities' representation.

2.3.2. Delphi Method Participants

Delphi method participants' selection targeted the specific inclusion of military behavioral health providers who treat active duty military populations over the age of 18, and researchers and clinicians who study Adjustment Disorders and/or military mental health. Delphi method participants were excluded if they participated in the Research Advisory Board. Eight panel members were recruited to participate in two Delphi rounds (Shang 2023). Our Delphi panel included active duty service members in order to prioritize their lived experiences. This is critical, because individuals who enlist may join in an undesignated status where their long‐term career trajectory is not necessarily clearly defined, and reasonable expectations may vary between branches, and between billets. The normal course of duty is not the same for every service member, but the stressors included in the ADNM‐20‐MIL were meant to capture elements of service that are more common to ADSMs than their civilian counterparts.

2.3.3. Pilot Study Participants

Pilot study participants included active duty service members, age 18 years and older, with a diagnosis of AjD in the past 12 months, with or without anxiety and/or depressed mood. Participants were excluded if they had any other psychiatric or substance use disorder in the past 12 months, or if they had already participated in the Delphi. A priori power analysis revealed the need for 20 participants to conduct the planned statistical analysis with an 80% power.

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. RAB Pre‐Delphi Round

Before Round 1 of the Delphi study phase, RAB members were asked to review the original ADNM‐20 and suggest additional stressors that would make the assessment tool military‐centric. At the end of this process, the edited assessment tool was uploaded to REDCap (Harris et al. 2009, 2019).

2.4.2. Delphi Round 1

In Round 1, panelists (military health care providers) used REDCap to determine the applicability, relevancy, and stability of the stressor items in a military population. Applicability and stability were measured with a dichotomous “yes/no” scale, and relevancy was measured with a five‐category Likert scale: “extremely likely/somewhat likely/likely/somewhat unlikely/unlikely.”

Item‐level content validity index (I‐CVI) was used to determine item‐level consensus. Consensus was defined a priori as I‐CVI of greater than or equal to 0.75 (Diamond et al. 2014). I‐CVI was calculated by averaging the applicability agreement rate (A) and the relevancy agreement rate (R) for each item (I‐CVI = (A + R)/2) (Polit and Beck 2006; Diamond et al. 2014). The applicability agreement rate (A) was calculated for each item by dividing the number of panelists who rated that item as “yes” by the total number of panelists who rated the item. The relevancy agreement rate (R) was calculated by dividing the number of panelists who rated that item as extremely likely, somewhat likely, or likely to precipitate AjD in active duty service members, by the total number of panelists who rated the item.

Item stability was captured by asking panelists if the item could be edited to better reflect the military context and if so, to provide suggestions. The stability agreement rate (S) was calculated for each item by dividing the number of panelists who rated that item as “no” by the total number of panelists who rated the item. In this instance, “no” indicated the item did not require additional editing and was applicable and relevant as written.

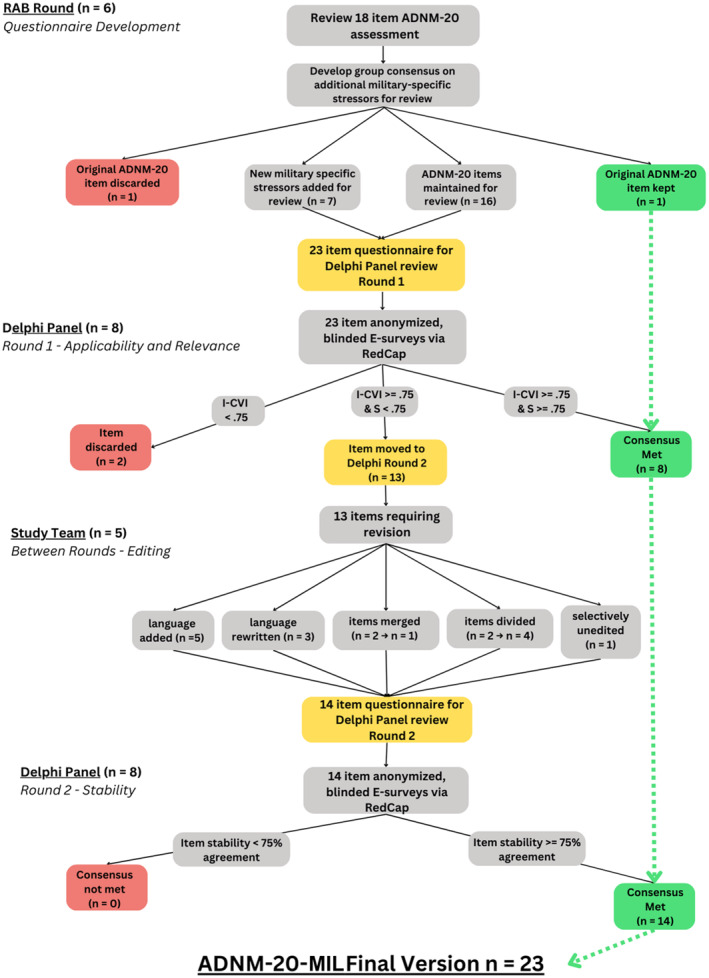

In Round 1, if I‐CVI was less than 0.75, the item was discarded. If I‐CVI was greater than 0.75 but S was less than 0.75, meaning the item is applicable and relevant, but requires editing, it was moved to Round 2. Consensus was met if I‐CVI was greater than or equal to 0.75, indicating the item was both applicable and relevant to the military community, and S was greater than 0.75, indicating the item did not require additional editing (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Survey development and Delphi round results. This flowchart follows the Delphi process through the development of the survey from its original version I (RAB Round), through Round 1 of the Delphi, internal study team editing, and Round 2 of the Delphi.

2.4.3. Delphi Round 2

Before Round 2, revisions to items were made based on the suggested edits from Round 1, and amalgamated data were provided to the same group of panelists for their review and consideration. Panelists then participated in another Delphi round to achieve consensus on the remaining stressor items. In Round 2, consensus was met if 75% of the panelists agreed the item required no further editing (Figure 2).

2.4.4. Pilot Study

Following Round 2 of the Delphi, and after consensus was met for the stressors items of the ADNM‐20‐MIL, consenting participants (active duty military members with an AjD diagnosis) completed a web‐based version of the ADNM‐20‐MIL, along with two additional questions pertaining to the ease, usability, and appropriateness of the ADNM‐20‐MIL stressor items. Participants completed the ADNM‐20‐MIL and additional feedback questions on two separate occasions, two weeks apart.

Internal reliability of the pilot‐testing for ADNM‐20‐MIL was performed by calculating internal reliability consistency coefficients for the total instrument as well as its test‐retest reliability. The instrument's internal reliability was examined by computing the Cronbach alpha for the total score of the ADNM‐20‐MIL. For test‐retest reliability, a one‐way random effects model was fitted to the repeated measures data with the total score as the response variable. Feedback was solicited regarding participants' perceptions of ADNM‐20‐MIL clarity and difficulty.

3. Results

3.1. RAB Round

RAB members removed 1 item from the original 18 item stressor list of the ADNM‐20 assessment tool: the second of two “Other” options, used when a participant wants to name a stressor that is not listed as a stressor item on the assessment tool. RAB members also reached a consensus to keep the first “Other” option as is, so this item was not present on the Delphi survey questionnaire for item‐level review. This resulted in 16 remaining original items for Delphi panelist review. Additionally, after thorough deliberations based on their personalized lived military experiences and knowledge of the military environment, RAB members recommended the addition of the following 7 military‐specific items as a way to ensure the ADNM‐20‐MIL's stressor list is applicable to the military: (1) loss of a significant relationship, (2) legal or disciplinary issues, (3) new deployment underway or other orders to leave home base, (4) adaptation to entering military service, (5) social isolation, lack of support, lack of unit camaraderie, (6) conflict with peers, (7) conflict with chain of command. This resulted in 23 stressor items on the survey questionnaire to be examined in Round 1 of the Delphi process (Figure 2).

3.2. Delphi Round 1

Consensus was met if I‐CVI was greater than or equal to 0.75 and S was greater than 0.75. Eight items met these criteria: (1) divorce/separation (I‐CVI = 0.94, S = 1.00), (2) moving to a new home (I‐CVI = 0.88, S = 1.00), (3) financial problems (I‐CVI = 1.00, S = 1.00), (4) termination of important leisure activity (I‐CVI = 0.81, S = 1.00), (5) loss of a significant relationship (I‐CVI = 0.88, S = 1.00), (6) legal or disciplinary issues (I‐CVI = 0.94, S = 1.00), (7) new deployment, underway, or other orders to leave home base (I‐CVI = 0.88, S = 1.00), and (8) adaptation to entering military service (I‐CVI = 0.94, S = 1.00) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Delphi Round 1: Consensus met stressors.

| Original ADNM‐20 stressor | I‐CVI | Stability agreement rate |

|---|---|---|

| ADNM‐20‐1: Divorce/separation |

|

|

| ADNM‐20‐11: Moving to a new home |

|

|

| ADNM‐20‐12: Financial problems |

|

|

| ADNM‐20‐16: Termination of an important leisure activity |

|

|

| RAB addition‐1: Loss of a significant relationship |

|

|

| RAB addition‐2: Legal or disciplinary issues |

|

|

| RAB addition‐3: New deployment underway or other orders to leave home base |

|

|

| RAB addition‐4: Adaptation to entering military service |

|

|

Note: P = Proportion of item applicability = # Delphi participants who said yes for applicability/total delphi participants. R = Proportion of item relevance = # Delphi participants who rated that item as somewhat likely, likely, or extremely likely to precipitate AjD in active duty service members/total Delphi participants. Item CVI = Mean (P; R).

Items with I‐CVI less than 0.75, regardless of S, were discarded. Two items had I‐CVIs less than 0.78 and were removed: (1) conflicts with neighbors (I‐CVI = 0.5), (2) unemployment (I‐CVI = 0.44).

Items were forwarded to Round 2 if I‐CVI was ≥ 0.75 and S < 0.75 in Round 1 (Figure 2). Thirteen items moved to Round 2. These included: (1) family conflict (Round 1: I‐CVI = 0.88, S = 0.25), (2) conflicts in work life (Round 1: I‐CVI = 0.94, S = 0.25), (3) Illness of a loved one (Round 1: I‐CVI = 0.94, S = 0.38), (4) death of a loved one (Round 1: I‐CVI = 0.94, S = 0), (5) adjustment due to retirement (Round 1: I‐CVI = 0.94, S = 0), (6) too much/too little work (Round 1: I‐CVI = 0.88, S = 0.25), (7) pressure to meet deadlines/time pressure (Round 1: I‐CVI = 0.94, S = 0.25), (8) own serious illness (Round 1: I‐CVI = 1.00, S = 0.25), (9) serious accident (Round 1: I‐CVI = 1.00, S = 0), (10) assault (Round 1: I‐CVI = 1.00, S = 0.63), (11) social isolation, lack of support, or lack of camaraderie in unit (Round 1: I‐CVI = 1.00, S = 0), (12) conflicts with peers (Round 1: I‐CVI = 0.81, S = 0.25), (13) conflict with chain of command (Round 1: I‐CVI = 1.00, S = 0.25).

3.3. Delphi Round 2

Before panelists began the second round of the Delphi process, the study team reviewed the proposed edits for the 13 remaining items. All 13 items had I‐CVIs of greater than 0.75 in Round 1, so the primary focus of Round 2 was editing these items so they were more clearly related to the military context. Five items were edited to clarify the meaning of the original stressor by placing a brief description in parentheses: (1) family conflicts, (2) death of a loved one, (3) adjustment due to retirement, (4) too much/too little work, (5) conflict with peers (Table 2). Three items were rewritten: (1) illness of a loved one, (2) pressure to meet deadlines/time‐pressures, (3) own serious illness (Table 2). Two items were merged into one: (1) conflicts in work life and (2) conflict with chain of command, became: conflicts in worklife (including conflicts with chain of command) (Table 2). Two items were divided into two separate items: serious accident became: (1) combat related injuries or trauma, and (2) non‐combat related injuries or trauma; and, social isolation, lack of support, lack of unit camaraderie became (1) isolation or restriction of movement related to military missions, and (2) geographic separation from family (Table 2). While edits were suggested for the final item, assault, the study team ultimately decided to leave this item unedited in Round 2. The suggested edits included naming specific types of assault, and ultimately that level of detail is not strictly necessary for the diagnosis of Adjustment Disorder, and is potentially triggering for patients completing the assessment tool. Therefore, it was left intentionally broad.

TABLE 2.

Delphi Round 2: Stressor modifications.

| Edit | Original ADNM‐20 stressor | Military‐adapted ADNM‐20‐MIL stressor |

|---|---|---|

| Language added | ADNM‐20‐2: Family conflict | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐4: Family conflict (including conflicts with spouse or significant other, conflicts with children, or conflicts with extended family) |

| ADNM‐20‐6: Death of loved one | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐7: Death of a loved one (including death of a family member, friend, unit member, or pet) | |

| ADNM‐20‐7: Adjustment due to retirement | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐8: Adjustment due to retirement (including transition to civilian workforce or emotional reaction to leaving the military) | |

| ADNM‐20‐9: Too much/too little work | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐9: Too much/too little work (high ops tempo, not enough work, or work that is not challenging enough) | |

| RAB addition‐6: Conflict with peers | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐6: Conflicts with peers (including conflicts with friends, or conflicts with unit members) | |

| Rewritten | ADNM‐20‐5: Illness of a loved one | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐16: Loved one's serious illness |

| ADNM‐20‐10: Pressure to meet deadlines/time pressures | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐10: Work‐related stressors (including pressure to meet deadlines) | |

| ADNM‐20‐13: Own serious illness | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐12: Personal illness or health decline | |

| Merged | ADNM‐20‐3: Conflicts in worklife | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐5: Conflicts in worklife (including conflicts with chain of command) |

| RAB addition‐7: Conflict with chain of command | ||

| Split | ADNM‐20‐14: Serious accident | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐13: Combat‐related injuries or trauma |

| ADNM‐20‐MIL‐14: Non‐combat related injuries or trauma | ||

| RAB addition‐5: Social isolation, lack of support, lack of unit camaraderie | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐15: Isolation or restriction of movement related to military mission | |

| ADNM‐20‐MIL‐3: Geographic separation from family |

Note: Edits were made to 12 of the 13 remaining items following Round 1.

Following this process, Delphi panelists began Round 2. As in Round 1, consensus was met if at least 75% of the panelists agreed on the edits made after the feedback provided in Round 1. All 13 items in Round 2 met this criteria (Table 3). This resulted in the final 23‐stressor list for the military adapted assessment tool, ADNM‐20‐MIL, now ready for pilot‐testing.

TABLE 3.

Consensus results from Round 2 of the Delphi process.

| Original ADNM‐20 stressor | Military‐adapted ADNM‐20‐MIL stressor | Consensus |

|---|---|---|

| ADNM‐20‐2: Family conflict | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐4: Family conflict (including conflicts with spouse or significant other, conflicts with children, or conflicts with extended family) | 6/8 = 0.75 |

| ADNM‐20‐3: Conflicts in worklife | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐5: Conflicts in worklife (including conflicts with chain of command) | 6/8 = 0.75 |

| RAB addition‐7: Conflict with chain of command | ||

| ADNM‐20‐5: Illness of a loved one | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐16: Loved one's serious illness | 8/8 = 1 |

| ADNM‐20‐6: Death of loved one | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐7: Death of a loved one (including death of a family member, friend, unit member, or pet) | 8/8 = 1 |

| ADNM‐20‐7: Adjustment due to retirement | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐8: Adjustment due to retirement (including transition to civilian workforce or emotional reaction to leaving the military) | 8/8 = 1 |

| ADNM‐20‐9: Too much/too little work | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐9: Too much/too little work (high ops tempo, not enough work, or work that is not challenging enough) | 8/8 = 0.875 |

| ADNM‐20‐10: Pressure to meet deadlines/time pressures | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐10: Work‐related stressors (including pressure to meet deadlines) | 6/8 = 0.75 |

| ADNM‐20‐13: Own serious illness | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐12: Personal illness or health decline | 6/8 = 0.75 |

| ADNM‐20‐14: Serious accident | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐13: Combat related injuries or trauma | 8/8 = 1 |

| ADNM‐20‐MIL‐14: Non‐combat related injuries or trauma | 8/8 = 1 | |

| ADNM‐20‐15: Assault | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐18: Assault | 8/8 = 1 |

| RAB addition‐5: Social isolation, lack of support, lack of unit camaraderie | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐15: Isolation or restriction of movement related to military mission | 8/8 = 1 |

| ADNM‐20‐MIL‐3: Geographic separation from family | 8/8 = 1 | |

| RAB addition‐6: Conflict with peers | ADNM‐20‐MIL‐6: Conflicts with peers (including conflicts with friends, or conflicts with unit members) | 7/8 = 0.875 |

3.4. Pilot‐Testing

To pilot‐test the ADNM‐20‐MIL, 22 active duty military members with an AjD diagnosis were asked to take the ADNM‐20‐MIL at two timepoints (Time1‐T1 and Time2‐T2), two weeks apart. Twenty‐two participants took the ADNM‐20‐MIL at T1, and 16 retook a second round at the 2 weeks‐interval, T2. Six participants were lost to follow‐up. Out of the total 22 pilot study participants, 52.38% were female and the mean age was 30.77 years (SD = 9.55). Our sample closely mirrored the demographics of the Armed Forces population, except for a higher proportion of women than in the general military population. However, this was not unexpected, as women have a higher incidence of AjD (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division 2024), and therefore a greater proportion of women in this sample was anticipated. Additional demographic details are presented in Table 4. The ADNM‐20‐MIL's internal consistency as well as its test‐retest reliability results were strong in this sample. The Cronbach alpha for the total ADNM‐20‐MIL score was 0.91, 95% CI [0.82, 0.95] and its test‐retest reliability coefficient was robust at 0.82, 95% CI [0.48, 0.93] in this sample.

TABLE 4.

Participant demographics ‐ pilot study.

| Total sample | DOD demographics*** | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex* | Sample size | Percentage | Percentage |

| Male | 10 | 47.62% | 82.3% |

| Female | 11 | 52.38% | 17.7% |

| Age | Average | STDEV | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 30.77 | 9.55 | 28.6 |

| Sample size | Percentage | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity** | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0.00% | 1.0% |

| Asian | 1 | 4.17% | 3.6% |

| Black or African American | 7 | 29.17% | 17.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 | 12.50% | 18.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.00% | 0.8% |

| White | 13 | 54.17% | 69.6% |

| Other | 0 | 0.00% | 1.8% |

| Branch | |||

| Army | 12 | 54.55% | 35.3% |

| Navy | 8 | 36.36% | 25.8% |

| Marines | 1 | 4.55% | 13.6% |

| Air force | 1 | 4.55% | 24.7% |

| Space force | 0 | 0.00% | 0.7% |

Note: Total sample size = 22; *one participant did not provide their sex; **some participants selected more than one ethnicity; ***Department of Defense (DoD 2023).

Participants were also asked to provide feedback regarding item clarity and difficulty following the assessment, at each timepoint. Following T1, 3/16 (18.75%) of participants reported some level of difficulty with the assessment. The difficulty reported following T1 was related to the directions, and some participants reported frustration due to the inability to expand upon the prescribed yes/no binary choice for each listed item stressor. Following the 2nd time point (T2), zero (0%) of participants reported any level of difficulty with the assessment.

4. Discussion

The current study is the first to adapt and pilot‐test an AjD‐specific assessment tool (the ADNM‐20‐MIL) in a U.S. Military sample. We used a rigorous Delphi method to identify which of the original stressors in the ADNM‐20 were relevant to the military and which ones needed editing or changing. After reaching consensus through two Delphi rounds, the original 18‐item stressor list in the ADNM‐20 resulted in a 23‐item stressor list in the ADNM‐20‐MIL. No changes were made to the symptoms list of the ADNM‐20. Our initial pilot‐testing of the ADNM‐20‐MIL revealed robust internal consistency for the entire tool (0.91, 95% CI [0.82, 0.95]) as well as good test‐retest reliability coefficient in this population (0.82, 95% CI [0.48, 0.93]). The assessment tool was well received by participants. This initial work is needed because it constitutes the basis for future continued efforts to evaluate the psychometric properties of the ADNM‐20‐MIL longitudinally and in a larger military sample. Additionally, having an empirically sound ADNM‐20‐MIL assessment tool will enhance diagnostic fidelity across providers and enable timely and accurate diagnosis of this disorder, all of which are necessary to further test disease specific treatment interventions in this population.

As a stress‐related disorder, an AjD diagnosis requires the presence of a preceding stressor; but the standard diagnostic manuals provide differing and amorphous diagnostic criteria beyond stressor identification. This is in stark contrast to other stress‐related disorders, like PTSD, for which DSM‐5‐TR's Criterion A, descriptions of the traumatic stressor (American Psychiatric Association 2022) as well as the Life Events Checklist for DSM‐5 (LEC‐5) (Weathers et al. 2015) provide clear guidance on potentially traumatic events that are known to be linked to PTSD. Researchers, clinicians, and patients all benefit from the clearly defined symptoms and stressors that comprise a diagnosis such as PTSD. Assessment tools like the PCL‐5 and the LEC‐5 (Weathers et al. 2015) have allowed researchers to understand the peculiarities of a PTSD diagnosis and how certain stressors can exacerbate symptoms leading to PTSD. This level of granularity does not exist for AjD, yet, but it is needed to make progress in understanding this disorder. Adjustment Disorders are predicated on understanding what a “normative” reaction is to the stressors of a particular situation. Provider access to a tool like the ADNM‐20‐MIL, which is grounded in the context of the population it services, will likely increase diagnostic fidelity.

Despite the widespread prevalence of AjD and its significant potential negative outcomes, AjD research continues to face challenges due to a lack of clarity in the details contributing to the diagnosis (O’Donnell et al. 2019; Kazlauskas et al. 2018; Zelviene and Kazlauskas 2018). Diagnostically, a stressor that results in AjD can be a single event, or a chronic, ongoing occurrence. The stressor can be traumatic, or non‐traumatic. Additionally, although it is expected that symptoms abate within 6 months once the stressor or its consequences have terminated, symptoms can continue if the stressor or its consequences continue. Both ICD‐11 and DSM‐5‐TR provide guidance regarding the need for and the timeline of the preceding trigger stressor event for an AjD diagnosis; however neither offers practical ways to operationalize how to measure this linkage between stressor and symptoms. Similar to how a traumatic event is clearly defined as a necessary condition for the diagnosis of PTSD, AjD diagnosis needs to have the relationship between its trigger stressor and symptoms defined and measured. This is even more necessary in the case of AjD because of its amorphous allowance of its trigger stressor to be traumatic or not, acute or chronic, and also its allowing the diagnosis to continue even if the stressor's consequences, and not necessarily the stressor itself, continue. Assessment tools that can capture both: the trigger stressor(s) and the linkage between trigger stressor(s) and AjD symptoms help extend DSM‐5‐TR and ICD‐11 guidance and can promote research on AjD's etiologies, trajectories, and treatments. There is increasing evidence for chronic trajectories for AjD in both civilian (O’Donnell et al. 2016) and military populations (M. Morgan et al. 2022). Consequently, AjD diagnosis is not always transient, and if it becomes chronic, it could be a gateway to other potentially more severe psychiatric diagnoses such as major depression, generalized anxiety, or PTSD. Current knowledge regarding AjD‐specific treatment is limited due to low quality of evidence mainly due to lack of psychometrically valid and reliable assessment tools to measure treatment effectiveness in both civilian (O'Donnell et al. 2018) and military populations (Bajjani‐Gebara et al. 2021).

Rigorously tested and psychometrically valid assessment tools provide an added layer of context, which is crucial not only for understanding disease pathology, but for supporting the development and testing of effective treatments. The development of a military‐specific assessment tool is the next step on a path toward diagnostic fidelity for AjD. It is critical to have an instrument that is accurately tuned to military specific stressors, because causative stressors are fundamentally linked to symptom manifestation, severity, and duration of AjD, and correctly identifying these stressors is critical to the successful assessment and treatment of AjD in this unique population.

Moving forward, implementing the ADNM‐20‐MIL will allow higher quality of research for AjD. Researchers can begin to tally stressor events ‐ which stressors are associated with the worst symptoms? Do stressors cluster? Are clinicians seeing patterns in their patients in terms of how patients score on the ADNM‐20‐MIL, and how symptoms present? The ADNM‐20‐MIL gives the field the power to ask and answer new questions. Additionally, the ADNM‐20‐MIL, by being tailored to military‐specific stressors, may result in lower prevalence rates compared to assessment tools designed for the general population (e.g., ICD‐9, ICD‐10), which apply broader diagnostic criteria not specific to military experiences. Having the means to apply tighter and more military‐centric assessment tools like the ADNM‐20‐MIL equips providers with the capability to identify early and intervene promptly to disrupt AjD disease from transitioning into more severe psychiatric outcomes, becoming chronic AjD, or causing separation from the military. This is a documented need, as one study that investigated 1,676,735 records of service members who entered the military during a 10‐year period (beginning 2004 through end of 2013) and identified 138,741 records of service members with AjD, found that nearly a quarter (24.3%) of them transitioned to another psychiatric diagnosis, another 8.9% transitioned to have chronic AjD, and nearly another quarter (23.1%) separated from the military (M. A. Morgan et al. 2023).

In the future, the civilian ADNM‐20 and the military ADNM‐20‐MIL may converge or be used interchangeably, however, the process of empirically and psychometrically validating these tools for use in the military, and comparing their performance, must occur first, as with the PCL‐M and PCL‐C assessment tools used for PTSD (Wilkins et al. 2011).

Additionally, the recently launched Warfighter Brain Health Initiative by the Department of Defense (DoD) underscores the importance of unifying medical communities to optimize brain health in ADSMs. This includes optimizing cognitive performance by identifying and monitoring brain health ‐ including mental health illnesses such as Adjustment Disorder. This support, in conjunction with the availability of the ADNM‐20‐MIL, should translate into the development of a training infrastructure for clinicians working inside the DoD to create a common language in describing, diagnosing, tallying, and treating instances of AjD in the military population.

5. Limitations

There are limitations related to the generalizability of these findings, particularly in regard to the specific characteristics of our sample and issues with self‐report of mental health symptoms. The ADNM‐20‐MIL tool was piloted exclusively with a U.S. military sample, which may limit the broader applicability of these findings to other populations (Simons et al. 2017). While the U.S. military is more diverse than the general population, our results may not generalize to all active‐duty service members or beyond. Throughout the research process, we prioritized input from our carefully‐selected RAB to ensure the diversity present in the military was largely reflected in how this work was designed. We recognize that while this approach strengthens the potential implications of this tool for public policy and clinical practice, it does not guarantee the full representativeness of the military's diverse composition being fully accounted for in this tool. While our sample aligns with the broader distribution of the Armed Forces, future work could enhance generalizability of the ADNM‐20‐MIL by employing targeted recruitment strategies (Clark and Bajjani‐Gebara 2025) to increase representation from smaller branches, such as the Space Force, as well as from underrepresented demographic groups. This study constitutes the initial step in the process of continuing to investigate the ADNM‐20‐MIL in future larger samples and over longitudinal periods.

Another potential limitation, although not specific to this study per se but rather pertaining to reporting of mental health symptoms in general, is that of service members' perceptions of stigma's consequences on their military career and how that affects their seeking of mental health care (Sharp et al. 2015; Coleman et al. 2017), and potentially how they may respond to survey questions. While complete eradication of mental health stigma may not be possible, having psychometrically valid assessment tools can enhance accurate AjD diagnosis, which in turn can contribute to stigma reduction by reducing subjectivity in provider assessments and promoting diagnostic fidelity.

6. Conclusions

The work described here was crucial for ensuring that the ADNM‐20‐MIL is suitable for future use within the military population. This study achieved this by applying a Delphi method to adapt the 18‐stressor ADNM‐20 to the 23‐stressor ADNM‐20‐MIL and pilot‐testing it with ADSM individuals with AjD diagnoses. The development of the ADNM‐20‐MIL represents a significant advancement in the field. The next step is to more rigorously evaluate the ADNM‐20‐MIL for validity and reliability by conducting longitudinal testing in a large cohort of ADSMs. This will also help determine sensitivity of the ADNM‐20‐MIL to changes over time. This enhanced psychometric evaluation into the assessment tool's effectiveness for the military population, is currently underway and will be detailed in a future publication. Effective assessment and treatment of adjustment disorder aligns with the Department of Defense's many initiatives to advance Warfighter Brain Health science and will help prevent disability and ensure positive outcomes for ADSMs as they continue with their military careers and as they eventually transition back into the general civilian population.

Author Contributions

Jouhayna Bajjani‐Gebara: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology. Dawnkimberly Hopkins: data curation, project administration, writing – review and editing. Joan Wasserman: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, visualization, writing – review and editing. Ryan Landoll: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing. Margaux Keller: data curation, project administration, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Disclosure

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or the Department of Defense. The views expressed also do not reflect the official policy or position of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine Inc.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Research Advisory Board members, study champions, students, and consultants who supported this work.

Funding: This study was funded by the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (CDMRP).

Preliminary results presented at the Military Health Systems Research Symposium which was held in August 2022 and September 2023.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . 2022. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787. [DOI]

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC) . 2013. “Summary of Mental Disorder Hospitalizations, Active and Reserve Components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000‐2012.” MSMR 20, no. 7: 4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division . 2021. “Update: Mental Health Disorders and Mental Health Problems, Active Component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2016–2020.” Medical Surveillance Monthly Report 28, no. 8: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division . 2024. “Diagnoses of Mental Health Disorders Among Active Component U.S. Armed Forces, 2019–2023.” Medical Surveillance Medical Report 31, no. 12: 2–11. https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2024/12/01/MSMR‐Mental‐Health‐Update‐2024. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayuso‐Mateos, J. L. , Vázquez‐Barquero J. L., Dowrick C., et al. 2001. “Depressive Disorders in Europe: Prevalence Figures From the ODIN Study.” British Journal of Psychiatry: Journal of Mental Science 179: 308–316. 10.1192/bjp.179.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachem, R. , Perkonigg A., Stein D. J., and Maercker A.. 2017. “Measuring the ICD‐11 Adjustment Disorder Concept: Validity and Sensitivity to Change of the Adjustment Disorder–New Module Questionnaire in a Clinical Intervention Study.” International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 26, no. 4: e1545. 10.1002/mpr.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachynski, K. E. , Canham‐Chervak M., Black S. A., Dada E. O., Millikan A. M., and Jones B. H.. 2012. “Mental Health Risk Factors for Suicides in the US Army, 2007‐‐8.” Injury Prevention: journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention 18, no. 6: 405–412. 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajjani‐Gebara, J. , Wilcox S. L., Williams J. W. Jr, et al. 2021. “Adjustment Disorders in U.S. Active Duty Military Women: A Scoping Review for the Years 2000 to 2018.” Women's Health Issues: official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health 31, no. Suppl 1: S33–S42. 10.1016/j.whi.2020.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth‐Kewley, S. , and Larson G. E.. 2005. “Predictors of Psychiatric Hospitalization in the Navy.” Military Medicine 170, no. 1: 87–93. 10.7205/milmed.170.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta, M. G. , Balestrieri M., Murru A., and Hardoy M. C.. 2009. “Adjustment Disorder: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Treatment.” Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health: CP & EMH 5, no. 1: 15. 10.1186/1745-0179-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey, P. , ed. 2018. Adjustment Disorder: From Controversy to Clinical Practice. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/med/9780198786214.001.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casey, P. , Jabbar F., O'Leary E., and Doherty A. M.. 2015. “Suicidal Behaviors in Adjustment Disorder and Depressive Episode.” Journal of Affective Disorders 174: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic Adjustment Disorder Diagnosis and Disposition (CHADD) Working Group, Navy Psychological Health Clinical Community (PHCC) . 2020. “Chronic Adjustment Disorder: Diagnosis and Disposition – Best Practices and Guidelines.” Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) Collaborative Care Board (CCB). [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. , and Bajjani‐Gebara J.. 2025. “Revolutionizing Remote Human Subjects’ Research Recruitment in the US Military During and Post COVID‐19: Lessons Learned from a Multiphase Mental Health Psychometrics Study.” Military Medicine. In Press. 10.1093/milmed/usaf090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, S. J. , Stevelink S. A. M., Hatch S. L., Denny J. A., and Greenberg N.. 2017. “Stigma‐Related Barriers and Facilitators to Help Seeking for Mental Health Issues in the Armed Forces: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Literature.” Psychological Medicine 47, no. 11: 1880–1892. 10.1017/S0033291717000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defense Health Agency (DHA), Psychological Health Center of Excellence 2017. Psychological Health by the Numbers: Mental Health Disorder Prevalence Among Active Duty Service Members, 2005–2016.

- Department of Defense 2023. 2023 Demographics Report: Profile of the Military Community. Military OneSource. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2023‐demographics‐report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, I. R. , Grant R. C., Feldman B. M., et al. 2014. “Defining Consensus: A Systematic Review Recommends Methodologic Criteria for Reporting of Delphi Studies.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67, no. 4: 401–409. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einsle, F. , Köllner V., Dannemann S., and Maercker A.. 2010. “Development and Validation of a Self‐Report for the Assessment of Adjustment Disorders.” Psychology Health & Medicine 15, no. 5: 584–595. 10.1080/13548506.2010.498892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegan, J. , and Doherty A. M.. 2019. “Adjustment Disorder and Suicidal Behaviours Presenting in the General Medical Setting: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 16: 2967. 10.3390/ijerph16162967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M. D. , and Woodruff S. I.. 2011. “Incidence and Predictors of Mental Health Hospitalizations in a Cohort of Young U.S. Navy Women.” Military Medicine 176, no. 5: 524–530. 10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, B. J. , Ribeiro S., Lee‐Tauler S. Y., et al. 2019. “Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Military Service Members Hospitalized Following a Suicide Attempt versus Suicide Ideation.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 18: 3274. 10.3390/ijerph16183274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, G. P. , DeZee K. J., Burks R., Waterman B. R., and Belmont P. J.. 2011. “Epidemiology of Psychiatric Disorders Sustained by a U.S. Army Brigade Combat Team During the Iraq War.” General Hospital Psychiatry 33, no. 1: 51–57. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. , Olsen C., Gomes J., Bajjani‐Gebara J., Meyers E., and Wilson R.. 2024. “Relative Risk of All‐Cause Medical Evacuation for Behavioral Health Conditions in U.S. Central Command.” Military Medicine 189, no. 1–2: e279–e284. 10.1093/milmed/usad306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. A. , Taylor R., Minor B. L., et al. 2019. “The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Partners.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics 95: 103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. A. , Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., and Conde J. G.. 2009. “Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) – A Metadata‐Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42, no. 2: 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskas, E. , Zelviene P., Lorenz L., Quero S., and Maercker A.. 2018. “A Scoping Review of ICD‐11 Adjustment Disorder Research.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 8, no. sup7: 1421819. 10.1080/20008198.2017.1421819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanski‐Ruscio, K. M. , Carreno‐Ponce J. T., De Young K., Grammer G., and Ghahramanlou‐Holloway M.. 2014. “Diagnostic and Psychosocial Differences in Psychiatrically Hospitalized Military Service Members With Single Versus Multiple Suicide Attempts.” Comprehensive Psychiatry 55, no. 3: 450–456. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom, K. E. , Smith T. C., Wells T. S., et al. 2006. “The Mental Health of U.S. Military Women in Combat Support Occupations.” Journal of Women's Health 15, no. 2: 162–172. 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, L. , Bachem R., and Maercker A.. 2016. “The Adjustment Disorder–New Module 20 as a Screening Instrument: Cluster Analysis and Cut‐Off Values.” International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 7, no. 4: 215–220. 10.15171/ijoem.2016.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M. , Spanovic‐Kelber M., Bellanti D. M., et al. 2022. “Outcomes and Prognosis of Adjustment Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 156: 498–510. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M. A. , O'Gallagher K., Kelber M. S., Garvey Wilson A. L., and Evatt D. P.. 2023. “Diagnostic and Functional Outcomes of Adjustment Disorder in U.S. Active Duty Service Members.” Journal of Affective Disorders 323: 185–192. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasa, P. , Jain R., and Juneja D.. 2021. “Delphi Methodology in Healthcare Research: How to Decide its Appropriateness.” World Journal of Methodology 11, no. 4: 116–129. 10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell, M. , Metcalf O., Watson L., Phelps A., and Varker T.. 2018. “A Systematic Review of Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adjustment Disorder in Adults.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 31, no. 3: 321–331. 10.1002/jts.22295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, M. L. , Agathos J. A., Metcalf O., Gibson K., and Lau W.. 2019. “Adjustment Disorder: Current Developments and Future Directions.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 14: 2537. 10.3390/ijerph16142537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, M. L. , Alkemade N., Creamer M., et al. 2016. “A Longitudinal Study of Adjustment Disorder After Trauma Exposure.” American Journal of Psychiatry 173, no. 12: 1231–1238. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F. , and Beck C. T.. 2006. “The Content Validity Index: Are You Sure You Know What's Being Reported? Critique and Recommendations.” Research in Nursing & Health 29, no. 5: 489–497. 10.1002/nur.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Z. 2023. “Use of Delphi in Health Sciences Research: A Narrative Review.” Medicine 102, no. 7: e32829. 10.1097/MD.0000000000032829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, M. L. , Fear N. T., Rona R. J., et al. 2015. “Stigma as a Barrier to Seeking Health Care Among Military Personnel With Mental Health Problems.” Epidemiologic Reviews 37, no. 1: 144–162. 10.1093/epirev/mxu012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons, D. J. , Shoda Y., and Lindsay D. S.. 2017. “Constraints on Generality (COG): A Proposed Addition to All Empirical Papers.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 12, no. 6: 1123–1128. 10.1177/1745691617708630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlman, S. , and Oetting A. A.. 2018. “Mental Health Disorders and Mental Health Problems, Active Component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2016.” Medical Surveillance Monthly Report 25, no. 3: 2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wijk, C. H. 2024. “Prevalence Estimate for Adjustment Disorders in the South African Navy.” Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health: CP & EMH 20, no. 1: e17450179301661. 10.2174/0117450179301661240528064329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers, F. W. , Blake D. D., Schnurr P. P., Kaloupek D. G., Marx B. P., and Keane T. M.. 2015. The Life Events Checklist for DSM‐5 (LEC‐5). National Center for PTSD. https://www.ptsd.va.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, K. C. , Lang A. J., and Norman S. B.. 2011. “Synthesis of the Psychometric Properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Military, Civilian, and Specific Versions.” Depression and Anxiety 28, no. 7: 596–606. 10.1002/da.20837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2019. ICD‐11: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 11th ed. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zelviene, P. , and Kazlauskas E.. 2018. “Adjustment Disorder: Current Perspectives.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 14: 375–381. 10.2147/NDT.S121072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelviene, P. , Kazlauskas E., Eimontas J., and Maercker A.. 2017. “Adjustment Disorder: Empirical Study of a New Diagnostic Concept for ICD‐11 in the General Population in Lithuania.” European Psychiatry 40: 20–25. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.