Abstract

We report the isolation and partial genetic characterization of two equine strains of granulocytic Ehrlichia of the genogroup Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Frozen whole-blood samples from two Swedish horses with laboratory-verified granulocytic ehrlichiosis were inoculated into HL-60 cell cultures. Granulocytic Ehrlichia was isolated and propagated from both horses. DNA extracts from the respective strains were amplified by PCR using primers directed towards the 16S rRNA gene, the groESL heat shock operon gene, and the ank gene. The amplified gene fragments were sequenced and compared to known sequences in the GenBank database. With respect to the 16S rRNA gene, the groESL gene, and the ank gene, the DNA sequences of the two equine Ehrlichia isolates were identical to sequences found in isolates from clinical cases of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in humans and domestic animals in Sweden. However, compared to amplified DNA from an American Ehrlichia strain of the E. phagocytophila genogroup, differences were found in the groESL gene and ank gene sequences.

Granulocytic Ehrlichia causes febrile diseases in many different animals and in humans. The first human cases were described for the United States in 1994, but clinical cases are now accumulating from many countries, mainly in temperate regions (3, 24, 29; A. van Dobbenburgh, A. P. van Dam, and E. Fikrig, Letter, N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1214-1216, 1999). In Scandinavia, clinical granulocytic ehrlichiosis (GE) has been reported for humans, cattle, sheep, horses, dogs, and cats (5, 7, 14, 26). The infectious agents are strictly intracellular rickettsia-like bacilli, with the capacity for intracellular life in the wildlife reservoir and the infected host, as well as prolonged survival in the principal vector, hard-bodied ticks of the genus Ixodes. Until the successful isolation of granulocytic ehrlichias in HL-60 cells, the possibilities of studying these bacteria were limited to indirect and molecular biological methods (16). Today, reports of successful isolation of granulocytic Ehrlichia from humans and animals are available from the United States but not from other parts of the world. The aim of this study was to isolate, maintain in culture, and genetically characterize European strains of granulocytotrophic Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Moreover, earlier reports on the isolation of granulocytic Ehrlichia spp. were based only on isolation from fresh blood. In this paper, we report the isolation of European E. phagocytophila of equine origin from stored frozen whole blood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Two horses (a 4-month-old Swedish trotting horse and a 21-year-old pony from southwest Sweden) entered the Halland Animal Hospital, Slöinge, Sweden, in the fall of 1998 with fever, malaise, and anorexia. EDTA-blood was collected under sterile conditions and frozen at −20°C without further preparation. Additional blood was collected and investigated by direct microscopy. Blood smears showed cytoplasmic inclusions in approximately 25 to 30% of the neutrophils in both cases, supporting the clinical diagnosis of GE. Both horses were treated with intravenous oxytetracycline (7 mg/kg of body weight daily for 7 days) and recovered clinically within 24 h.

Culture of ehrlichias in HL-60 cells.

Promyelocytic HL-60 leukemia cells (ATCC CCL240) were maintained in antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and 20% fetal bovine serum. The HL-60 cells were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 (16). An aliquot of 0.5 ml of the sedimented leukocyte-rich fraction of equine EDTA-blood (kept at −20°C for 7 months) was inoculated into 25-cm2 flasks with HL-60 cells at a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml. The infected cells were then monitored daily by microscopy and examination of Giemsa-stained cytospin-prepared cell spreads. The cultures were kept at a density of 2 × 105 to 4 × 105 cells/ml by feeding them with medium two to three times a week. Infection of the cells was quantified by the presence of morulae and by indirect immunofluorescence assay using a bovine anti-Ehrlichia immunoglobulin G-positive serum and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-bovine immunoglobulin G antibody (product no. 209-095-088; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), diluted 1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline, as secondary antibody. Noninfected HL-60 cells were used as negative controls.

PCR amplification and sequence analysis.

DNA was extracted from infected and noninfected cells with the QIAamp Tissue Kit protocol (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Nested PCR protocols targeting the 16S rRNA gene, the ank gene, and the groESL gene were followed as described previously, but with minor changes (21, 22, 27). The primers used to amplify the 16S rRNA gene were 16SF1 (5′ AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTC) and GE10 (5′ TTCCGTTAAGAAGGATCTAATCTCC) for the primary reaction and EC12A (5′ TGATCCTGGCTCAGAACGAACG) and EHR790 (5′ CTTAACGCGTTAGCTACAACACAG) for the nested reaction. In the groESL assay, HS43 (5′ ATAGCTAAGGAAGCATAGTC) and HS45 (5′ ACTTCACGTCTCATAGAC) were used for the primary reaction, and GEHS1 (5′ AGTCTTATGCTACGGTTGTTTG) and EHS6 (5′ ACAATATCAGATCCAGCAGC) were used for the nested reaction. In the ank gene assay, AQ2F3 (5′ GAAGAAATTACAACTCCTGAAG) and AQ2R2 (5′ CAGCCAGATGCAGTAACGTG) were used for the primary reaction, and AQ2F2 (5′ TTGACCGCTGAAGCACTAAC) and AQ2R1 (5′ ACCATTTGCTTCTTGAGGAG) were used for the nested reaction. Each of the primers was subsequently used for direct sequencing of the appropriate purified PCR product. Two additional primers were needed to sequence the 781-bp region amplified by the 16S rRNA PCR, EB4 (5′ GTATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGCAC) and EHR521 (5′ TGTAGGCGGTTCGGTAAGTTAAAG). Sequencing reaction products were separated and analyzed using an automated sequencer (ABI 377; Applied Biosystems) and fluorescent-labeled dideoxynucleotide technology. Sequences were edited and analyzed with the Staden software program and the Wisconsin Sequence Analysis Package (Genetics Computer Group) (11, 12). Gene sequences used for comparison were obtained from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank).

RESULTS

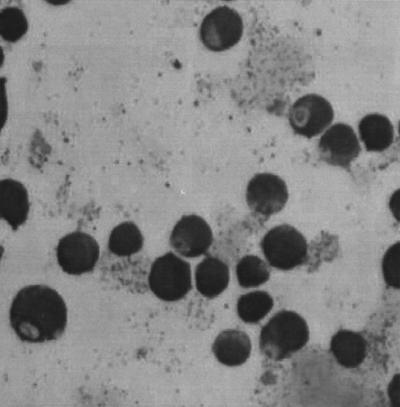

The two strains showed similar propagation patterns. Seven days after equine blood and HL-60 cells were mixed, the first signs of morulae could be noted in the infected cells when they were analyzed with Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations (Fig. 1). Noninfected cells, grown and analyzed in parallel, showed no corresponding cell changes. During the following days, the extent of infection increased: 10% infected cells at day 7 and 60% at day 16. After day 16, the infection declined so that at day 26 only 20% of the cells were infected.

FIG. 1.

Photomicrograph of E. phagocytophila-infected HL-60 cells stained with Giemsa stain. Magnification, approximately ×900.

Cells infected with the respective strain were positive in PCR assays targeting the 16S rRNA gene, the ank gene, and the groESL gene of granulocytic Ehrlichia. The amplified 781-bp fragments of the 16S rRNA gene sequences were identical to corresponding sequences of amplified DNA obtained in Swedish human cases of GE (19). Similarly, the groESL gene and the ank gene sequences of the equine Ehrlichia isolates were identical for the two isolates and identical to the sequences of the corresponding gene fragments from Swedish human strains (21).

DISCUSSION

GE in horses was described as a clinical entity in Scandinavia in 1990 (6). The two infected horses in the present study resided in an area in southern Sweden where GE is commonly diagnosed in horses and dogs. They showed typical clinical signs of ehrlichiosis and responded well to treatment. Thus, the two Ehrlichia isolates described represent pathogenic granulocytic Ehrlichia strains from an area of southern Sweden where GE is endemic. To our knowledge, these two strains of equine origin are the first two European granulocytic Ehrlichia strains to be isolated and propagated in cell culture.

As gene sequence data for granulocytic ehrlichias accumulate, proposals have been made to merge E. equi, E. phagocytophila, and the human GE agent into a single species, E. phagocytophila (10, 13, 27). In accordance with these proposals and with data obtained in this study, E. phagocytophila has been used to designate the clinical isolates in this study.

The establishment of an infection in a cell line may vary in time and rate. In this study 10% of the HL-60 cells were infected 1 week after infection with the two equine isolates. Other studies of in vitro cultures of E. phagocytophila in HL-60 cells have shown that some culture systems result in an infection rate of ≥50 to 60% while other systems never reach more than a 2 to 5% infection rate. The infections are also established with different rapidities (16). These differences probably relate to the bacterial load of the inoculum, to Ehrlichia strain variations, and to variations in the HL-60 cell populations.

The16s rRNA gene has become the “gold standard” for classification of bacteria. In this study, the nucleotide sequences of the 781-bp fragments of the 16S rRNA gene of the equine E. phagocytophila isolates were completely identical to the most common sequence variant of 16S ribosomal DNA obtained in clinical cases of GE in humans, cattle, horses, dogs, and cats in Scandinavia and other parts of Europe, as well as in human and canine cases in the United States (4, 7, 15, 17-19, 24).

In order to investigate the genetic and antigenic relationship between closely related bacterial species, the comparison of more-variable genes, e.g., genes of structural proteins, may be of value, since the 16S rRNA gene is too conserved to be able to resolve strain differences at this level. One possible gene to study is the ank gene, coding for a 160-kDa cytoplasmic protein antigen (8, 25). Analyses of this gene from several granulocytic Ehrlichia strains from geographically different areas resulted in the division of E. phagocytophila into three distinct clades: northeastern United States, upper midwestern United States, and Europe (21). The ank gene sequences of our two equine isolates were identical to previously described ank gene sequences in Swedish and Slovenian E. phagocytophila isolates from humans and animals but showed only 94 to 96% identity with ank gene sequences of North American E. phagocytophila isolates. The groESL sequences obtained from our equine E. phagocytophila isolates were identical to each other and to a previously characterized Swedish E. phagocytophila isolate from an infected human but differed from all other Ehrlichia groESL sequences present in GenBank by at least two nucleotides (27).

The principal wildlife reservoir of E. phagocytophila is believed to be small mammals, mainly rodents, and deer (1). The fact that both the reservoir and vector species differ between North America and Europe and that coevolution of the bacteria, the vector, and the host must to a large extent be independent processes on the two continents means that significant differences in strain characteristics can be expected, both genetically and in terms of phenotypic traits, such as antigenic profile, host preferences, and virulence. Antigenic pleomorphism has been reported earlier for various isolates of E. phagocytophila (2, 20, 30). Our results show differences between the North American and European variants of E. phagocytophila and suggest that the ank gene provides useful information complementary to that from the 16S rRNA gene that can be used to divide E. phagocytophila into clades corresponding to geographic distribution (9). This is interesting, as some of the differences found may lead to better geographically adapted diagnostic tools and to understanding of differences in bacterial virulence and host preferences (2, 20, 23, 28, 30). Thus, these results warrant further comparisons of E. phagocytophila strains of different geographic origins in terms of genetic relationships, expression of antigens, ecology, and epidemiology.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Intervet Veterinary Research Foundation (981116), the Health Research Council of Southeast Sweden (F98-118), and the Swedish National Board for Laboratory Animals (CFN, Dnr 00-41).

We thank Gunvor Johansson at the Halland Animal Hospital for expert technical assistance in collecting samples and J. Stephen Dumler for helpful advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberdi, M. P., A. R. Walker, and K. A. Urquhart. 2000. Field evidence that roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) are a natural host for Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:315-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asanovich, K. M., J. S. Bakken, J. E. Madigan, M. Aguero-Rosenfeld, G. P. Wormser, and J. S. Dumler. 1997. Antigenic diversity of granulocytic Ehrlichia isolates from humans in Wisconsin and New York and a horse in California. J. Infect. Dis. 176:1029-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakken, J. S., S. J. Dumler, S. M. Chen, M. R. Eckman, L. L. Van Etta, and D. H. Walker. 1994. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the upper Midwest United States. A new species emerging? JAMA 272:212-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakken, J. S., J. Kreuth, C. Wilson-Nordskog, R. Tilden, K. Asanovich, and J. S. Dumler. 1996. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE): clinical and laboratory characteristics of 41 patients from Minnesota and Wisconsin. JAMA 275:199-205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjöersdorff, A., J. Berglund, B. E. Kristiansen, C. Söderström, and I. Eliasson. 1999. Variable presentation and course in human granulocytic ehrlichiosis; 12 case reports of the new tick-borne zoonosis. Läkartidningen 96:4200-4204. (In Swedish with English summary.) [PubMed]

- 6.Bjöersdorff, A., D. Christenson, A. Johnsson, A. C. Sjöström, and J. E. Madigan. 1990. Granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the horse—the first verified cases in Sweden. Sven. Veterinärtidning 42:357-360. (In Swedish with English summary.)

- 7.Bjöersdorff, A., L. Svendenius, J. H. Owens, and R. F. Massung. 1999. Feline granulocytic ehrlichiosis—a report of a new clinical entity and characterisation of the infectious agent. J. Small Anim. Pract. 40:20-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caturegli, P., K. M. Asanovich, J. J. Walls, J. S. Bakken, J. E. Madigan, V. L. Popov, and J. S. Dumler. 2000. ankA: an Ehrlichia phagocytophila group gene encoding a cytoplasmic protein antigen with ankyrin repeats. Infect. Immun. 68:5277-5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chae, J. S., J. E. Foley, J. S. Dumler, and J. E. Madigan. 2000. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of 16S rRNA, 444 Ep-ank, and groESL heat shock operon genes in naturally occurring Ehrlichia equi and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent isolates from Northern California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1364-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, S. M., J. S. Dumler, J. S. Bakken, and D. H. Walker. 1994. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:589-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dear, S., and R. Staden. 1991. A sequence assembly and editing program for efficient management of large projects. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:3907-3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devereux, J., P. Haeberli, and O. Smithies. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumler, J. S., K. M. Asanovich, J. S. Bakken, P. Richter, R. Kimsey, and J. E. Madigan. 1995. Serologic cross-reactions among Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia phagocytophila, and human granulocytic ehrlichia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1098-1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egenvall, A., Å. Hedhammar, and A. Bjöersdorff. 1997. Clinical features and serology of 14 dogs affected by granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Sweden. Vet. Rec. 140:222-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engvall, E. O., B. Pettersson, M. Persson, K. Artursson, and K. E. Johansson. 1996. A 16S rRNA-based PCR assay for detection and identification of granulocytic Ehrlichia species in dogs, horses, and cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2170-2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman, J. L., C. Nelson, B. Vitale, J. E. Madigan, S. J. Dumler, T. J. Kurtti, and U. G. Munderloh. 1996. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greig, B., K. M. Asanovich, P. J. Armstrong, and J. S. Dumler. 1996. Geographic, clinical, serologic, and molecular evidence of granulocytic ehrlichiosis, a likely zoonotic disease, in Minnesota and Wisconsin dogs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:44-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson, K. E., B. Pettersson, M. Uhlen, A. Gunnarsson, M. Malmqvist, and E. Olsson. 1995. Identification of the causative agent of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Swedish dogs and horses by direct solid phase sequencing of PCR products from the 16S rRNA gene. Res. Vet. Sci. 58:109-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlsson, U., A. Bjöersdorff, R. F. Massung, and B. Christensson. 2001. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis—a clinical case in Scandinavia. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 33:73-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnarelli, L. A., J. W. Ijdo, S. J. Dumler, R. Heimer, and E. Fikrig. 1998. Reactivity of human sera to different strains of granulocytic ehrlichiae in immunodiagnostic assays. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1835-1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massung, R. F., J. H. Owens, D. Ross, K. D. Reed, M. Petrovec, A. Bjoersdorff, R. T. Coughlin, G. A. Beltz, and C. I. Murphy. 2000. Sequence analysis of the ank gene of granulocytic ehrlichiae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2917-2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Massung, R. F., K. Slater, J. H. Owens, W. L. Nicholson, T. N. Mather, V. B. Solberg, and J. G. Olson. 1998. Nested PCR assay for detection of granulocytic ehrlichiae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1090-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogden, N. H., K. Bown, B. K. Horrocks, Z. Woldehiwet, and M. Bennett. 1998. Granulocytic ehrlichia infection in ixodid ticks and mammals in woodlands and uplands of the UK. Med. Vet. Entomol. 12:423-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrovec, M., S. L. Furlan, T. A. Zupanc, F. Strle, P. Brouqui, V. Roux, and J. S. Dumler. 1997. Human disease in Europe caused by a granulocytic Ehrlichia species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1556-1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storey, J. R., L. A. Doros-Richert, C. Gingrich-Baker, K. Munroe, T. N. Mather, R. T. Coughlin, G. A. Beltz, and C. I. Murphy. 1998. Molecular cloning and sequencing of three granulocytic Ehrlichia genes encoding high-molecular-weight immunoreactive proteins. Infect. Immun. 66:1356-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuen, S. 1993. Tick-borne fever in lambs of different ages. Acta Vet. Scand. 34:45-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sumner, J. W., W. L. Nicholson, and R. F. Massung. 1997. PCR amplification and comparison of nucleotide sequences from the groESL heat shock operon of Ehrlichia species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2087-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuomi, J. 1967. Experimental studies on bovine tick-borne fever. 3. Immunological strain differences. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 71:89-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker, D. H. 1998. Tick-transmitted infectious diseases in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 19:237-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhi, N., Y. Rikihisa, H. Y. Kim, G. P. Wormser, and H. W. Horowitz. 1997. Comparisons of major antigenic proteins of six strains of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent by Western immunoblot analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2606-2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]