Highlights

-

•

Citizens Advice on Prescription provides advice/support via health services to reduce financial insecurity.

-

•

The intervention included a quick referral process with proactive follow-up by case workers.

-

•

It led to fewer antidepressant prescriptions and mental health emergencies.

-

•

It reduces mental health-related GP consultations and A&E attendances.

-

•

Citizens advice on prescription likely improves mental health and is cost-saving to the health service.

1. Introduction

Individuals living on low incomes experience poorer health outcomes (Marmot et al., 2010). Income losses, debt and housing payment problems have all been found to increase mental health problems (Cooper & Stewart, 2015; Mason et al., 1982; Turunen & Hiilamo, 2014). A growing body of work has examined the impact of national welfare schemes on health outcomes and inequalities. In general, policies that provide more generous social security benefits lead to improvements in mental health, whilst policies that narrow eligibility criteria or lower generosity of support are associated with worsening of mental health (Cooper & Stewart, 2015; Simpson et al., 2021; Thomson et al., 2022; Wickham et al., 2017, 2020). As well as a cause of mental ill-health, poverty is also a consequence (Boardman et al., 2015; Elliot, 2016; Payne, 2018).

Providing advice and support for people to access the welfare system as well as support to address other social determinants of health, such as employment and housing, has the potential to help mitigate the negative health impacts of poverty (Gabbay et al., 2017a). Whilst there has been some research investigating the provision of welfare advice – particularly in health care settings, much of this has been limited by small sample sizes and a lack of robust causal methods to evaluate health impacts. Most studies have focused on whether welfare advice successfully helps recipients secure financial support, with limited attention given to the broader health effects of these interventions (Adams et al., 2006; Reece et al., 2022). The few studies that have examined health outcomes generally report positive associations between welfare advice and mental health improvements. For example, one small controlled study found a reduction in psychological distress among recipients of welfare advice, although the effects did not reach statistical significance at conventional levels (Woodhead et al., 2017). A recent systematic review on the effectiveness and experiences of welfare advice services co-located within health settings highlights several benefits, including financial gains and improvements in mental health and well-being for individuals accessing these services. However, the review underscores the need for more robust, high-quality research employing causal methods and larger sample sizes to strengthen the evidence base (Reece et al., 2022). Much of the existing evidence remains primarily associational rather than causal.

Households in the UK have been experiencing multiple social and economic shocks in recent year as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Daras et al., 2021) and increased costs for essential goods due to increased demand and disruption in supply following the pandemic alongside rising global food and energy prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Several national welfare policies and cuts to public services in the UK have also increased the risk of poverty for some groups, adversely affecting health (Barr et al., 2016; Taylor-Robinson et al., 2019; The Living Standards Outlook, 2022, 2022, 2022; Wickham et al., 2020). In response to this in Liverpool, one of the most disadvantaged cities in England, the NHS funded the Citizens Advice on Prescription (CAP) programme, providing rapid access through health services to social welfare advice and support – including help with financial issues, housing difficulties, debt, relationship breakdown, bereavement, domestic abuse, social isolation and fuel poverty, as well as signposting to local wellbeing services. With CAP supporting more than 5000 clients per year, this is one of the largest such schemes in England.

Citizens Advice on Prescription has the potential to influence mental health through multiple pathways: (1) reduced psychological distress through emotional support and practical advice provided by case workers, (2) improved material conditions due to increased welfare benefit receipt and improved debt management increasing household income (3) enhanced social connections and reduced isolation through enhanced engagement in local wellbeing activities and (4) healthier behaviours (e.g., increased physical activity, improved diet). These improvements are interconnected; for instance, greater financial security could enable participation in other beneficial activities, such as training, which in turn may enhance income and financial stability.

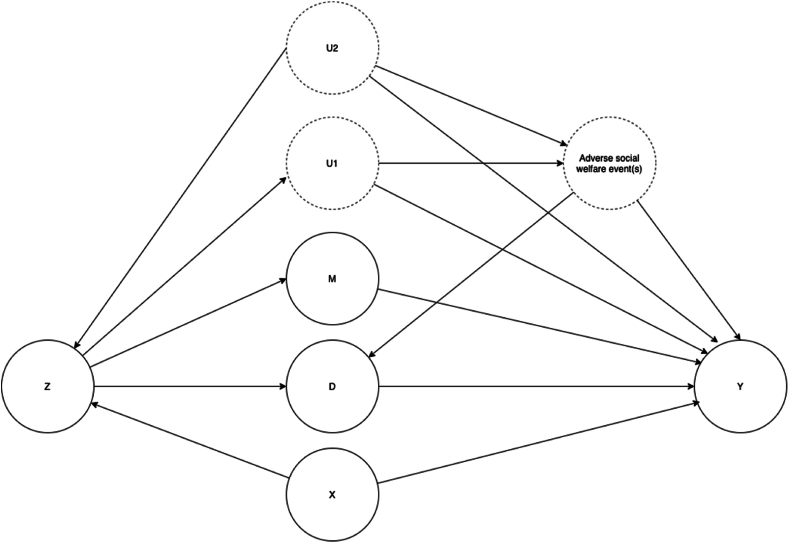

Concurrent qualitative research conducted alongside this study indicated that people often received the CAP intervention due to severe financial, social or health crises. (Evaluating the health impact and) The service was also available for individuals facing more long-term financial adversity. These crises or ongoing adversity have potentially major impacts on health outcomes and support from CAP could potentially mitigate these effects via overall life stress reduction, leading to fewer adverse consequences than would have otherwise been the case. (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Logic model highlighting pathways through which the CAP programme is expected to impact on health.

It is important to test the effectiveness of such services and their impact on health outcomes, to determine if they are an effective use of health care resources. We therefore applied a causal instrumental variable approach to estimate the mental health impacts of this large programme of social welfare advice and support.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and study population

Our analysis used a unique anonymised linked dataset covering the whole population of Liverpool (497,000) (Office of National Statistics O, 2024) including data from primary and secondary care records and the case management system of Citizens Advice. These datasets were pseudonymised and linked by NHS digital's Data Services for Commissioners Regional Office (DSCRO), following which, anonymised data were shared with NHS Cheshire and Merseyside. The NHS matched addresses to Unique Property References Numbers (UPRNs) (Government Digital Service, 2022) enabling anonymised household indicators enabling analysis of household level effects. Data were available from 2017 to 2023; our analysis focused on the post-pandemic period 2021–23, and we used additional historical data from 2017 to 20 in the construction of control variables and our instrumental variable. We included all individuals registered with a GP and resident in Liverpool between 2021 and 2023 who were alive during the study period. We excluded people living at addresses with more than 10 people living at the same address as this likely represented house of multiple occupancy rather than individual households, giving a total population of 435,031. The intervention group included all people in households that had newly received support through CAP in 2021–2023 whose data could be linked with health care records. Households previously receiving support in 2017–2020 were excluded from the intervention group. There were 12042 new recipients of CAP services during this period, and the DSCRO was able to find exact matches in health records for 8205 people (68 %) from 7828 households. We defined all individuals living at the same address, as CAP recipients if at least one member of the household received CAP support. We analysed the impact at the household level as the intervention was focused on alleviating poverty which will affect the whole household. This provided 20,773 in our intervention group of members of households who had received support from CAP (mean number of people per household = 2.7).

The intervention date was defined as the quarter in which the individual was first recorded on Citizens Advice's case management system. As the intervention dates were staggered throughout the year and as there is no “intervention date” for the individuals who did not receive the intervention, we applied a ’placebo’ intervention date to each individual in the non-intervention group by randomly sampling from the intervention dates from the intervention group (Piroddi et al., 2022a). This means that the placebo intervention dates follow an identical distribution in the two groups and the average follow up time is identical and follows the same seasonal distribution. We only included people in the sample with at least one quarter of follow up time post intervention date.

2.2. Intervention

Initially, to promote referrals, CAP case workers liaised with frontline health workers to raise awareness. Following this, patients who accessed Liverpool-based health services and who had been identified by health care professionals as at risk of financial hardship were referred to Citizens Advice on Prescription (CAP) via email or telephone. There were no specific eligibility criteria, with referrals based on health professionals' discretion. Within two working days of referral, a CAP case worker contacted the referred patients to carry out preliminary telephone assessments and arrange a face-to-face or telephone follow up session. A tailored plan of support was developed with each client often involving multiple sessions. This was most often in the form of support for welfare benefits, and included help with other financial matters, housing difficulties, debt, relationship breakdown, bereavement, domestic abuse, social isolation and/or fuel poverty as prioritized in agreement with the patient during the assessment. Some patients, if needed and wanted, were also signposted to access local health and wellbeing services and activities. The intervention was initially introduced in 2014, however the health services that have been able to refer into CAP have expanded over time. The service was initially piloted in a small number of Liverpool GP practices in 2014 and was extended to include all practices and mental health services in 2015. Between 2018 and 2023 the intervention was further extended to include other health services including respiratory services, cancer care, health visiting, midwifery and perinatal mental health services.

2.3. Measures

We used the following outcome measures in our analysis.

-

•

The mean quarterly number of Average Daily Quantities (ADQs) of antidepressants prescribed per person following the intervention date. ADQs are a standardised way of measure prescribing quantities used by the NHS in England (NHSBA, 2012). Antidepressant prescriptions were defined based on Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) codes recorded on each GP practice's clinical management system. These SNOMED codes were mapped to the British National Formulary (BNF) codes, and antidepressants selected based on inclusion in the chapter 4.3, excluding Amitriptyline, which is now largely used for pain management.

-

•

The average quarterly number of mental health related GP consultations per person following the intervention date. These were defined as contacts with a GP or nurse in general practice, coded on the GP clinical system with one or more of a set of mental health related codes (see Appendix 1 for details of the code list).

-

•

The quarterly number of mental health related attendances at an accident and emergency department (A&E) following the intervention date. These were defined as attendances at A&E recorded in the Emergency Care Services Dataset, the method and diagnostic codes used for these measures are in Appendix 1. (Emergency Care Data Set)

-

•

The quarterly number of mental health related emergency admissions following the intervention date, recorded from the Secondary Uses Services Admitted Patient Care data; the method and diagnostic codes used for these measures are in Appendix 1. (Secondary Uses Service (SUS); Springate et al., 2014; Thayer et al., 2024; Organization, 1992; Janca et al., 1993; Cornes et al., 2021; Schofield et al., 2021; Morgan et al., 2017)

Following comments from a reviewer we have additionally included all cause Accident and Emergency and emergency admissions as outcomes, to explore whether there were positive or negative effects on wider health care utilisation. Other covariates included age, age squared, sex, neighbourhood indices of multiple deprivation (IMD) (Ministry of Housing & Communities and Local Government, 2019), diagnosis of depression, anxiety, severe mental illness, alcohol or other substance abuse (Appendix 1 shows the SNOMED codes used to define each of these conditions). We included several measures to reflect preintervention levels and trends in mental health outcomes in 2018–2020 and in the quarter before receiving the intervention. These included numbers of GP consultations for mental health reasons, anti-depressant ADQs prescribed and number of A&E attendances for mental health reasons. To account for differences between GP practices in access to services and propensity for prescribing and admission we included the GP practice average rates for each outcome between 2018 and 2020 and the % reporting difficulty in accessing a GP practice reported in the GP patient survey in 2019.

2.4. Analysis

As highlighted above generally people receive CAP due to socioeconomic shocks, ongoing financial insecurity or a deterioration in economic circumstances. As we do not have information in our dataset on such adverse events (e.g. job loss, debts, homelessness) or ongoing financial circumstances, we cannot match people receiving CAP who have experienced these adverse events to others who have also experienced them but who have not received support from CAP. This means that other methods that rely on selection of observables such as difference in differences, propensity score matching or inverse probability of treatment weighting are unlikely to provide an unbiased estimate of the intervention effect (Shadish et al., 2002). We therefore used an instrumental variable approach as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Direct Acyclic Graph showing potential causal relationships, where Z is an instrument, M are measured mediators between Z and the outcomes Y and C are measured confounders between Z and the outcomes Y and we assume that there are no unmeasured confounders or mediators (U1 and U2).

Instrumental variables are used to control for unobserved confounders in observational studies so that causal inferences can be made (Greenland, 2000). While instrumental variables have been primarily used in economics research, they have also been increasingly applied in epidemiological studies. A key concern with using observational data to infer causality is that individuals may be more likely to receive treatment due to confounders which also influence outcomes, for example in CAP, experiencing job loss may lead to a referral to CAP and would also directly influence mental health. To address this, we need to identify a factor, known as an instrument, that influences whether someone receives the intervention, but does not directly influence the outcome, conditional on other observed variables. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 2, to be valid our instrument Z must only be associated with the outcome Y through its effect on treatment D, conditional on any observed mediators(M) of the effect of Z on Y or any observed confounders (X) of the effect of Z on Y. i.e. there should be no unobserved mediators (U1) or confounder (U2). In other words, Z should be something that increases the probability of some people receiving the intervention while being independent of the adverse events that are driving the need for the CAP intervention.

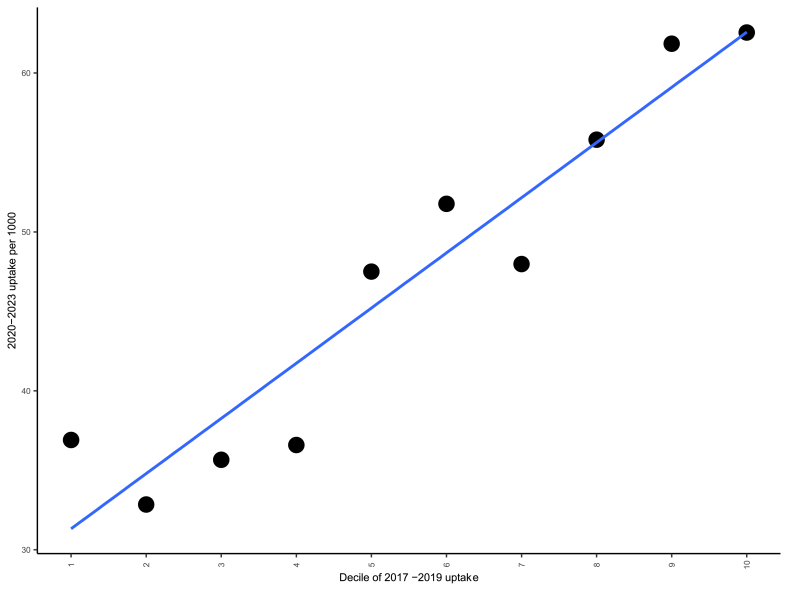

Our selection of instrument was based on preference-based instruments that have been applied frequently in previous medical research using physician (Brookhart et al., 2006; Korn & Baumrind, 1998; Wang et al., 2005), region (Brooks et al., 2003; Stukel et al., 2007), or provider (Brookhart & Schneeweiss, 2007; Johnston, 2000) preferences for treatments as an instrument to estimate causal effects. GP practices are the main referrers into the CAP intervention, however there is a great deal of variation in referral rates that is not explained by differences in population need. Some practices are much more likely to refer patients into CAP than others, this is largely due to some having provided the service for longer, being more engaged in the service or also having social prescribing link workers provided by Citizens Advice Liverpool. We used the rank of the 96 GP practices in Liverpool according to their number of referrals into CAP from before the pandemic (2017–2019) as our instrument as this provides a good measure of the propensity of a practice to refer into the service in 2021–2023, conditional on other indicators of population need (e.g. deprivation, age and morbidity, X in Fig. 2).

For this to be a valid instrument it should be both a relevant and exogenous. It should affect our outcomes only through its relationship with receipt of the intervention and not through any other pathway, that cannot be controlled for. Clearly there is potential for mediators to act between this instrument and our health outcomes. For example, high referring practices may also be better at managing mental health problems, have lower thresholds of prescribing or better access to other services supporting mental health problems leading to lower A&E attendances or emergency admissions. We have however controlled for these paths by conditioning on past A&E attendances, admissions and prescribing rates both at the individual and GP practice level (M in Fig. 2). Remaining biases could remain if there are pathways that that we have not controlled for, we explore this by comparing other characteristics of GP practices with higher and lower predicted probability of referral into CAP (see below). A second assumption is that an instrument is “relevant” and strongly corelated. A weak correlation between the instrument and the explanatory variable can result in imprecise estimates and weak instrument bias (Angrist & Pischke, 2009). We test this association below.

Our estimations using this instrument were then computed using a two stage least squares regression model (Angrist & Pischke, 2009; Wooldridge, 2002). In the first stage we modelled receipt of the intervention in 2021–2023 as a function of our instrument and a set of control variables, at the individual and GP practice level ( Equation (1)). The second stage is a similar Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression of each of our outcomes regressed on the fitted values from the first stage, and the same set of control variables.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where is the receipt of the intervention by individual ‘i’ in GP practice ‘j’ in 2021–2023. is our instrumental variable, is a set of controls for individuals and is a set of controls for GP practices. refers to each of our mental health outcomes. We repeated this procedure for each of the four health care utilisation outcomes listed above including as controls age, sex, IMD, diagnosis with depression, anxiety, severe mental illness, alcohol or other substance abuse, the pre-intervention individual level of the outcome in 2018–2020 and in the quarter before intervention, the GP practice average rates of the outcome 2018–2020 and percentage of the practice registered population reporting difficulty in accessing a GP. For each model we tested the strength of our instrument with the Sanderson and Windmeijer (2016) multivariate F test, to investigate weak instrument problems and the Wu-Hausman test to investigate whether the intervention variable is indeed endogenous. As OLS methods may not be robust to non-normal distributed error terms, we derive confidence intervals using bootstrapping approach (Bland & Altman, 2015; Briggs & Gray, 1999) to determine the level of sampling uncertainty surrounding these estimates by replicating the full analysis on 1000 samples, deriving the 95 % confidence intervals from this distribution. Full model results are given in appendix 3. To investigate how CAP affected outcomes over time of follow up, we repeated our analysis separately for each quarter of follow up, up to a maximum of 8 quarters (i.e. 2 years).

To explore our assumptions in relation to the exchangeability of groups defined by our instrument, we plot the trend in each of our outcomes for two groups, based on the upper and lower quartiles of their predicted receipt of CAP, for four quarters before and after the intervention. Their predicted receipt of CAP was estimated based on the rank of their GPs' historical referral rate (i.e. our instrument), as in equation (1). To account for observed differences in outcomes that are adjusted through the controls in our model, we plot the trend in adjusted outcomes as the residuals from a linear regression, including all our control variables as above and the outcome as a dependant variable. If these groups defined by our instrument are similar, we would expect similar trends in both groups for these adjusted outcomes prior to intervention. To further examine whether differences remain between these groups after the IV and covariate adjustment, we investigate the balance in other GP practice characteristics between these two groups, that we did not include in our model. It is possible that practices that are more likely to refer into the scheme are different in other ways that might bias the results – for example having more capacity or better quality of care. To do this we compare measures that are routinely available through GP practice profiles, (National General Practice Profiles) including the practice's Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) achievement, the % of people reporting a positive experience of their practice, the number of full time equivalent clinical staff per 10,000 patients, the average number of appointments per registered patients and the % of patients reporting a long standing illness. The QOF is a national quality improvement programme that all practices participate in, where practices receive points for meeting certain quality standards.

2.5. Estimating the net costs and impact on quality adjusted life years

Estimates from the instrumental variable model indicate the effect of the intervention on each of the four health care utilisation outcomes amongst members of households supported by CAP. We calculate any cost saving or additional costs to the NHS resulting from a reduction or an increase in these outcomes using the NHS average estimated tariff costs for mental health related A&E attendances and emergency admissions in Liverpool during this time period calculated from the NHS Secondary User Service data for Liverpool. (Secondary Uses Service (SUS)) For antidepressant prescribing we use the net ingredient costs per ADQ of antidepressants of the and for GP consultations we use the Unit Costs for Health and Social Care 2023 developed by the Personal Social Services Research Unit (Jones et al., 2024).

We estimate the annual cost to the NHS of CAP per member of households supported, using data provided by Citizens Advice Liverpool on total costs of the service of £1,254,417, per year. Details of the costing of the programme are provided elsewhere (Granger et al., 2025). These costs only include the CAP service funded by the NHS, and do not include costs that may accrue to other services due to increased onward referral or increased uptake of welfare benefits for example. This gave an estimated cost per household member supported of £55. We estimated the net cost to the NHS of the service as the difference between the cost to the NHS of providing the programme from the estimated costs saved to the NHS from the impact of the intervention on the four health care utilisation outcomes, as estimated from the instrumental variable analysis. We assume that any reductions or increases in healthcare utilisation are only sustained over one year. We used bootstrapping to derive confidence intervals for these estimates as outlined above (Bland & Altman, 2015; Briggs & Gray, 1999).

3. Results

A total of 444,896 individuals made up our study population, 20,773 of whom were members of households that received CAP support between 2021 and 2023. In Appendix 2 we show shows the overall trend for each of the four outcomes in the year before and after receipt of CAP, compared to the trend in the rest of the population. Consistently across the four outcomes the level of the outcome is markedly higher in the intervention group compared to the non-intervention group with the trend rapidly increasing leading up to the point CAP users received support and shows a declining trend in outcomes during the months following the intervention.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the intervention group and the rest of the population in Liverpool. The intervention group is very different in all characteristics: CAP users exhibit more adverse health outcomes; are older; have a higher prevalence of mental health conditions; live in more deprived areas; and have higher levels of utilisation across all our outcomes. These variables are all adjusted for in our analysis and the instrumental variable approach additionally aims to account for other unobserved or residual confounding.

Table 1.

Characteristics of people receiving CAP compared to the rest of the population in Liverpool.

| Not receiving CAP | CAP | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 424,123 | 20,773 | |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 42.01 (22.38) | 42.85 (22.76) | <0.001 |

| Male (%) | 213219 (50.8) | 10212 (49.3) | <0.001 |

| Depression (%) | 47717 (11.4) | 5142 (24.8) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety (%) | 61754 (14.7) | 5496 (26.6) | <0.001 |

| Severe Mental Illness (%) | 4748 (1.1) | 558 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Substance or alcohol misuse (%) | 14717 (3.5) | 1214 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| IMD (mean (SD)) | 43.29 (20.72) | 51.16 (18.10) | <0.001 |

| Antidepressants ADQ 2018–2020 per person (mean (SD)) | 120.13 (461.23) | 253.07 (684.08) | <0.001 |

| GP practice average antidepressant ADQs per patient 2018–2020 (mean (SD)) | 126.48 (36.37) | 134.43 (33.94) | <0.001 |

| Antidepressants (ADQ) per person Quarter before intervention (mean (SD)) | 12.62 (46.78) | 30.58 (71.87) | <0.001 |

| GP consultations 2018–2020 per 1000 people (mean (SD)) | 524.23 (2114.20) | 1160.24 (3395.96) | <0.001 |

| GP practice average GP consultations 2018–2020 per 1000 people (mean (SD)) | 553.65 (238.44) | 571.65 (252.38) | <0.001 |

| GP consultations Quarter before intervention per 1000 people (mean (SD)) | 37.06 (238.87) | 205.28 (639.53) | <0.001 |

| Emergency admissions 2018–2020 per 1000 people (mean (SD)) | 93.91 (640.49) | 216.68 (919.10) | <0.001 |

| GP practice average emergency admissions 2018–2020 per 1000 people (mean (SD)) | 102.35 (31.33) | 110.74 (28.64) | <0.001 |

| Emergency admissions Quarter before intervention per 1000 people (mean (SD)) | 9.30 (90.52) | 32.84 (174.55) | <0.001 |

| A&E attendances 2018–2020 per 1000 people (mean (SD)) | 17.55 (256.96) | 41.80 (513.05) | <0.001 |

| GP practice average A&E attendances per 1000 people 2018–2020 (mean (SD)) | 18.86 (9.24) | 19.34 (9.64) | <0.001 |

| A&E attendances Quarter before intervention per 1000 people (mean (SD)) | 2.32 (58.38) | 9.88 (110.19) | <0.001 |

| % reporting difficulty accessing GP practice (mean (SD)) | 71.36 (12.45) | 70.54 (12.43) | <0.001 |

Fig. 3 shows the trend in adjusted outcomes 1 year before and 1 year after receipt of CAP for two groups based on the upper and lower quartiles of their predicted receipt of CAP based on our IV – the rank of GP practices historical referral rate. The difference between trends in these two groups reflects the contrast that is estimated in the IV regression below. The trend before the intervention is broadly similar in the two groups, then tends to diverge after the intervention, falling to a greater extent in the high predicted uptake group compared to the low predicted uptake group, for antidepressants, GP consultations and A&E attendances. When comparing the characteristics of the GP practice populations between these two groups (high and low predicted receipt of CAP), we find that they are well-matched across a number of quality measures, suggesting that there are not major differences between the characteristics of the GPs associated with propensity to refer that may bias the findings (see Appendix 3)

Fig. 3.

Trend in adjusted outcomes for high and low uptake groups based on the upper and lower quartile of their IV predicted uptake of CAP.

In the first-stage of the two-stage instrumental variable regression the F-statistics vary between 187 and 308 indicating that the instrument was relevant and highly corelated with the probability of receiving CAP. More specifically, the first stage result (see Appendix 4) indicates that each one-unit increase in the rank of GP practice historical uptake was associated with an additional two people per 1000 population receiving CAP in 2020–2023. In relative terms someone registered with a GP in the 90th percentile of CAP referrals in 2017–2019 was around twice as likely receive a CAP referral in 2020-23 than someone who was registered with a GP in 10th percentile (see Appendix 5). The Wu-Hausman test firmly rejects the null hypotheses, providing evidence that the intervention variable is indeed endogenous and the usual OLS methods would lead to biased estimates.

Table 2 shows the estimated impact of first CAP receipt in 2021–2023, for each of our four outcomes, from the two-stage instrumental variable regression. The intervention was associated with a reduction in all four of the outcomes, suggesting improved mental health for households receiving CAP compared to those not receiving support. These were statistically significant at the 5 % level for all outcomes apart from emergency admissions. This suggests that the decline in these outcomes following intervention, was greater than it would have been in the absence of the intervention.

Table 2.

Estimated effect of the CAP intervention on four mental health related outcomes per quarter based on two stage least squares instrumental variable regression, for all household members receiving CAP. Confidence intervals based on 1000 bootstrap replications.

| Outcome |

95 % CI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect on household member receiving CAP | Estimate | Lower | upper | P value |

| Anti-depressants (per person) | −15.7 | −20.6 | −2.7 | 0.03 |

| MH GP consultations (per 1000) | −190.5 | −227.4 | −71.9 | <0.001 |

| MH A&E attendances (per 1000) | −23.4 | −31.1 | −1.1 | 0.01 |

| MH emergency admission (per 1000) | −10.5 | −23.8 | 26.5 | 0.59 |

When estimating the effect for each quarter of follow up (see Appendix 6) we generally find that effect sizes appear to increase over time, i.e. suggesting that the benefits accumulate over time, leading to greater benefits at longer follow-up times. This was true for GP consultations and anti-depressants over two years of follow-up, however for A&E attendances after a year of follow-up benefits appear to wane. Larger effects were observed when only including individuals who directly accessed CAP, rather than all household members (see Appendix 7). When including all cause A&E attendances and hospital admissions as outcomes, we find much larger effects on all cause A&E attendances, suggesting the intervention was associated with a reduction of 142 A&E attendances per 1000 people receiving the intervention. We find no statistically significant association with all cause admissions. (see Appendix 8).

The average saving to the NHS resulting from the estimated reduction in antidepressant prescribing, mental health related GP consultations and mental health related A&E attendances was estimated to be £91 per person (95 % CI £44 to £107). We have not used the reduction in all cause A&E attendances in this calculation, as that outcome was not part of the pre-planned analysis and added later following reviewers’ comments. As the cost of the service was estimated to be £55 per household member, this gives a net cost of the service of -£36 (95 % -£51 to +£11). In other words, the intervention is likely to be cost saving to the NHS. Based on 1000 bootstrap replications, the 95 % confidence intervals indicate the true value could range between a £51 per person cost saving to an £11 per person net cost with 93.4 % of the effect estimates from these replications being less than zero, suggesting it is likely that the service is cost saving to the NHS. It should also be noted that this is a saving/net cost to the NHS, the service could have led to increased costs in other sectors for example to the welfare system. If the estimated effect on all cause A&E attendances was included in this calculation that would greatly increase the estimated cost saving by an additional ∼ £200 per person.

4. Discussion

We found that the Citizens Advice on Prescription programme in Liverpool appears to have led to lower antidepressant prescribing, mental health related GP attendances and mental health related A&E attendances for people receiving support. The estimated cost savings to the NHS relative to the costs of providing the intervention indicate that is likely to be a net cost saving to the NHS.

The analyses presented here have several strengths. First, we used a large, linked dataset that covered the whole population of the city of Liverpool, over multiple years during which the intervention was implemented. This provided a much larger sample than previous studies. Detailed information on morbidities and historical health service use addressed some of the issues of low power often found with instrumental variable studies (Lu et al., 2023) whilst also enabling adjustment for several observable confounders. However, several challenges remain in estimating causal effects from observational data.

Firstly, whilst the instrument we used has strengths both in theoretical terms and is a good predictor of current uptake of the intervention, the underlying assumptions needed for causal inference are untestable (Labrecque & Swanson, 2018). It is still possible that unobserved ‘back door’ pathways explain some of the associations observed. For example, there may be characteristics of GP practices that meant they were historically more likely to refer patients to CAP that also led to improvements in mental health outcomes during the study period. For example, they may have greater clinical experience, provide higher quality of care, or have greater awareness of the social determinants of health, which could improve mental health outcomes through better prevention, diagnosis, treatment, or management. While we controlled for GP practice-level averages of outcomes (e.g., prescribing rates and mental health service use) and measures of patient-reported difficulty in accessing GP services, these adjustments may not fully account for subtle variations in GP practice quality. When we did compare practice on a range of practice quality indicators that were not in our original control set however, we do find they are well balanced, suggesting that there are not major systematic differences. Our use of pre-pandemic referral behaviour as our instrument also partially mitigates this concern by anchoring GP referral propensity to historical patterns, which are less likely to be influenced by current unobserved patient or practice level factors.

Secondly, even if these assumptions hold, the estimates presented here do not necessarily reflect the average treatment effect for those receiving the intervention (Labrecque & Swanson, 2018). Where there is heterogeneity of treatment effects, then the results may reflect the average causal effect within a subset of compliers (i.e. people who receive the intervention because of a GP practice's propensity for referring patients). This is referred to as the LATE (local average treatment effect) as opposed to the ATE – Average Treatment Effect. For example, it could be that the patients with the greatest needs were likely to be referred regardless of which GP practice they were registered with whilst those with the least needs were equally unlikely to be referred by any GP practice. Therefore, it would be the people with intermediate needs whose probability of referral was most affected by a GP practice's propensity for referring. Our results would then represent the effect of the intervention for this intermediate group and not necessarily the effect on high or low need groups. If the effect on these other groups was smaller – that could mean that our results are an underestimate. It is not possible however to determine precisely whether the effect of our instrument on the probability or the intervention effect varied across subgroups to determine the extent to which the LATE we estimate differs from the ATE.

Thirdly, our analysis is limited to using outcomes that rely on data recorded in electronic health records. This means using outcomes that are derived from health care utilisation. Whilst it is reasonable to hypothesise that improvements in the mental health of participants would lead to declines in the four health care utilisation outcomes, it is also possible that interventions such as CAP led to increases in health care utilisation. For example, if addressing social welfare issues enables people to access health care to address previously unmet needs then this would lead to increased utilisation even if overall health and quality of life has improved. The findings of the intervention reported here are therefore best considered as a conservative estimate of health benefits resulting from the intervention.

Fourthly, our analysis was only able to assess costs and savings to the NHS, and even then, may not have included all costs or savings to the NHS. It is likely that the intervention led to increased costs to the welfare system for example, due to people being supported to access benefits to which they were entitled. Previous evidence has also found there are multiplier effects in terms of economic benefits from increasing access to social protection (Cardoso et al., 2023). We were not able to assess the wider costs and benefits. As outlined above, wider NHS costs and benefits may have resulted from the intervention increasing uptake of NHS services other than the outcomes measures here.

Whilst this study indicates potential positive impacts of Citizens Advice on Prescription, conclusively estimating the impact would require a randomised controlled trial. Given the high potential for patient benefits reported here, investment in a cluster randomised trial should be considered.

Our findings have important implications for practice. Several national policies over the past few decades have proposed that the NHS should have a greater role in tackling the social determinants of health (Department of Health, 2003; NHS England, 2019). However, it has often been difficult for commissioners and clinicians to know what NHS-focused action on the social determinants should look like in practice. This has been hampered by a lack of evidence comparing the costs and benefits of such approaches compared to other health care interventions. The CAP approach provides a practical option for tackling routine social and welfare support accessible through health services. The approach provided access to support for relatively large numbers of people (with an estimated 75,000 people living in households supported by CAP from 2017 to 2023) living with high levels of both socioeconomic and health need. An estimated 70 % of the cohort were living in poverty, 90 % had long term conditions and 60 % had multiple conditions. At the point they accessed support through CAP, they had extremely high levels of health care service use (Gebremariam et al., 2023). Characteristics of Liverpool's CAP that are potentially important include a simple rapid referral process without complex eligibility criteria, with case managers pro-actively contacting clients. In other words, clinicians just needed to make one phone call to make the referral, and the patient was then contacted within two working days. This process likely enabled high levels of access when health care professionals were often juggling multiple competing priorities and patients in need were typically dealing with multiple crises. Adding any complexity to the referral process could potentially lead to a large reduction in service uptake by those with the greatest need. Getting the service embedded in new NHS service areas also had challenges, meaning that it took time for it to become normal practice to ask people about their social and economic circumstances and to refer them into the service. Outreach, training and awareness raising with clinicians was an important ongoing component of the approach (Gabbay et al., 2017b; Gebremariam et al., 2023).

The NHS is currently experiencing massive pressures from increasing demand and financial constraints, with pressures on many Integrated Care Boards to take measures to reduce costs. (NHS Confederation, 2024) In times of financial constraint, NHS organisations often focus on modifying processes of care, such as improving referral pathways, integrating care teams or expanding telehealth options, to try and reduce demand (Healthy London Partnership), despite the fact that there is limited evidence that such modifications are effective (Flores-Mateo et al., 2012; Piroddi et al., 2022b). Rather counter-intuitively, interventions that reduce the social determinants of health care utilisation are often cut when budgets are tight. (Investing in the public health) The findings reported here indicate that each household member supported was estimated to save the NHS £36. This would indicate that the programme overall had saved the NHS £2.7 million (95 % CI 3.8 million saving to £750,000 net cost), between 2017 and 2023. However, we acknowledge that these estimates only reflect reductions in specific types of health care use and do not account for all potential healthcare costs or benefits. Furthermore, we do not take account of costs and benefits in other sectors resulting from the programme-such and the welfare system and wider preventative activities provided by community organisations or local government. Nonetheless, our findings offer evidence that direct support through health services to address social and financial adversity can play a role in alleviating pressures on the NHS.

This large-scale programme offering social and welfare advice and support for people through health services, successfully enabled large numbers of people with high need to improve in their mental health and to reduce their use of health care services. Expanding the provision of Citizens Advice on prescription across the NHS would likely improve health outcomes for patients and save the NHS money. This should be carried out alongside continued evaluation to enhance the evidence base for effectiveness.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Gebremariam Aregawi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Piroddi Roberta: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation. Daras Konstantinos: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Anderson De Cuevas Rachel: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Abba Katharine: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Gabbay Mark: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Validation. Corcoran Rhiannon: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Granger Rachel: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Ezeofor Victory: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Tudor Edwards Rhiannon: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Validation. Mahoney Clare: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Validation. Barr Benjamin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was granted from the University of Liverpool Central Ethics Committee, ref: 10313.

Data sharing

All data analysed for this research is held by NHS Cheshire and Merseyside.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was granted from the University of Liverpool Central Ethics Committee, ref: 10313.

Declaration of interest

Clare Mahoney is the lead commissioner at NHS Cheshire and Merseyside for the Service. No other authors have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme (project reference: NIHR202465). BB, KD, MG and RP are supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (grant reference number NIHR200182). RP was supported by NIHR Three Research Schools Fellowship in Mental Health Research (NIHR MHF016). The research was part-funded by a grant award that was applied by CM from the Health Foundation: Innovating for Improvement, Round 6. The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Appendix 1. Codes and definition used to define each outcome

Anti-depressant prescriptions

Data on antidepressant prescribing was sourced from the extract of data from GP practice clinical systems that flows to the Cheshire and Merseyside NHS secure data environment. The quantity of antidepressant prescribed each month included all prescriptions within the BNF chapter 4.3. The quantity of each prescription was then converted into an Average Daily Quantity (ADQ) using a look up table giving the ADQ equivalent for each formulation (see https://pldr.org/download/emyye/ff7/Indicator_specification_p_1_07.pdf)

Mental health related GP consultations

Data on mental health related GP consultations were sourced from the extract of data from GP practice clinical systems that flows to the Cheshire and Merseyside NHS secure data environment. Mental health related GP consultations were defined as any GP encounter or event, limited to a maximum of 1 per day, that included a set of mental health related SNOMED codes the SNOMED codes listed are outlined below.

Table A. 1.

SNOMED concept codes to search GP records for common mental health conditions.

| cluster | SNOMED Concept | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 402191000000101 | [X] Anxiety disorders: [other specified] or [anxiety hysteria] |

| Anxiety | 192405006 | [X]Anxiety disorder, unspecified |

| Anxiety | 450751000000102 | [X]Anxiety disorder, unspecified |

| Anxiety | 192399008 | [X]Other anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 468761000000105 | [X]Other anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 192403004 | [X]Other mixed anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 478661000000105 | [X]Other mixed anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 192397005 | [X]Other phobic anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 402951000000107 | [X]Other phobic anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 268714001 | [X]Other specified anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 469151000000104 | [X]Other specified anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 192400001 | [X]Panic disorder [episodic paroxysmal anxiety] |

| Anxiety | 416621000000108 | [X]Panic disorder [episodic paroxysmal anxiety] |

| Anxiety | 192398000 | [X]Phobic anxiety disorder, unspecified |

| Anxiety | 464911000000101 | [X]Phobic anxiety disorder, unspecified |

| Anxiety | 192393009 | [X]Phobic anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 472131000000109 | [X]Phobic anxiety disorders |

| Anxiety | 192610003 | [X]Separation anxiety disorder of childhood |

| Anxiety | 399651000000100 | [X]Separation anxiety disorder of childhood |

| Anxiety | 386808001 | Abnormal fear |

| Anxiety | 58963008 | Acrophobia |

| Anxiety | 192042008 | Acute post-trauma stress state |

| Anxiety | 47372000 | Adjustment disorder with anxiety |

| Anxiety | 782501005 | Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood |

| Anxiety | 70691001 | Agoraphobia |

| Anxiety | 191722009 | Agoraphobia with panic attacks |

| Anxiety | 61569007 | Agoraphobia without history of panic disorder |

| Anxiety | 34938008 | Alcohol induced anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 82339009 | Amphetamine induced anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 191736004 | Anancastic neurosis |

| Anxiety | 54307006 | Animal phobia |

| Anxiety | 48694002 | Anxiety |

| Anxiety | 225644006 | Anxiety about altered body image |

| Anxiety | 247808006 | Anxiety about body function or health |

| Anxiety | 702535006 | Anxiety about breathlessness |

| Anxiety | 300895004 | Anxiety attack |

| Anxiety | 231504006 | Anxiety depression |

| Anxiety | 197480006 | Anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 51493001 | Anxiety disorder caused by cocaine |

| Anxiety | 724722007 | Anxiety disorder caused by dissociative drug |

| Anxiety | 2.2621E+13 | Anxiety disorder caused by drug |

| Anxiety | 724723002 | Anxiety disorder caused by ketamine |

| Anxiety | 724708007 | Anxiety disorder caused by MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) |

| Anxiety | 724654009 | Anxiety disorder caused by opioid |

| Anxiety | 55967005 | Anxiety disorder caused by phencyclidine |

| Anxiety | 762331007 | Anxiety disorder caused by stimulant |

| Anxiety | 737341006 | Anxiety disorder caused by synthetic cannabinoid |

| Anxiety | 762515000 | Anxiety disorder caused by synthetic cathinone |

| Anxiety | 52910006 | Anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition |

| Anxiety | 37868008 | Anxiety disorder of adolescence |

| Anxiety | 53467004 | Anxiety disorder of childhood |

| Anxiety | 109006 | Anxiety disorder of childhood OR adolescence |

| Anxiety | 788866004 | Anxiety due to dementia |

| Anxiety | 231506008 | Anxiety hysteria |

| Anxiety | 94641000119109 | Anxiety in pregnancy |

| Anxiety | 207363009 | Anxiety neurosis |

| Anxiety | 70655008 | Caffeine induced anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 34563004 | Cancer phobia |

| Anxiety | 39951001 | Cannabis induced anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 192611004 | Childhood phobic anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 191708009 | Chronic anxiety |

| Anxiety | 19887002 | Claustrophobia |

| Anxiety | 191737008 | Compulsive neurosis |

| Anxiety | 191733007 | Cyesiophobia |

| Anxiety | 38617005 | Dental phobia |

| Anxiety | 192108001 | Disturbance of anxiety and fearfulness in childhood and adolescence |

| Anxiety | 192111000 | Disturbance of anxiety and fearfulness in childhood and adolescence NOS |

| Anxiety | 657791000000107 | Disturbance of anxiety and fearfulness in childhood and adolescence NOS |

| Anxiety | 371631005 | Episodic paroxysmal anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 191728008 | Fear of crowded places |

| Anxiety | 102912007 | Fear of death |

| Anxiety | 21897009 | GAD - Generalised anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 15277004 | Hallucinogen induced anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 20876004 | Inhalant induced anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 54587008 | Isolated phobia |

| Anxiety | 70997004 | Mild anxiety |

| Anxiety | 61387006 | Moderate anxiety |

| Anxiety | 191738003 | Obsessional neurosis |

| Anxiety | 17496003 | Organic anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 50026000 | Organic anxiety disorder caused by psychoactive substance |

| Anxiety | 191720001 | Phobic anxiety |

| Anxiety | 386810004 | Phobic anxiety |

| Anxiety | 47505003 | Posttraumatic stress disorder |

| Anxiety | 191709001 | Recurrent anxiety |

| Anxiety | 1686006 | Sedative, hypnotic AND/OR anxiolytic-induced anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 126943008 | Separation anxiety |

| Anxiety | 11806006 | Separation anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 85061001 | Separation anxiety disorder of childhood, early onset |

| Anxiety | 80583007 | Severe anxiety (panic) |

| Anxiety | 25501002 | Social anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety | 191724005 | Social phobia, fear of eating in public |

| Anxiety | 191725006 | Social phobia, fear of public speaking |

| Anxiety | 191726007 | Social phobia, fear of public washing |

| Anxiety | 231521002 | Weight fixation |

| Anxiety symptoms | 859891000000103 | Able to manage anxiety |

| Anxiety symptoms | 247825008 | Anxiety about behavior or performance |

| Anxiety symptoms | 225642005 | Anxiety about not coping with parenthood |

| Anxiety symptoms | 225635005 | Anxiety about treatment |

| Anxiety symptoms | 247805009 | Anxiety and fear |

| Anxiety symptoms | 69479009 | Anxiety hyperventilation |

| Anxiety symptoms | 198288003 | Anxiety state |

| Anxiety symptoms | 191711005 | Anxiety state NOS |

| Anxiety symptoms | 633361000000109 | Anxiety state NOS |

| Anxiety symptoms | 191704006 | Anxiety state unspecified |

| Anxiety symptoms | 621271000000109 | Anxiety state unspecified |

| Anxiety symptoms | 286709003 | Character trait finding of level of anxiety |

| Anxiety symptoms | 81350009 | Free-floating anxiety |

| Anxiety symptoms | 286644009 | Level of anxiety |

| Anxiety symptoms | 1149156003 | Reduced level of anxiety |

| Depression | 310495003 | [X]Mild depression |

| Depression | 430421000000104 | [X]Mild depressive episode |

| Depression | 465441000000108 | [X]Moderate depressive episode |

| Depression | 755331000000108 | [X]Recurrent major depressive episodes, severe, with psychosis, psychosis in remission |

| Depression | 397711000000100 | [X]Severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms |

| Depression | 397701000000102 | [X]Severe depressive episode without psychotic symptoms |

| Depression | 755321000000106 | [X]Single major depressive episode, severe, with psychosis, psychosis in remission |

| Depression | 83458005 | Agitated depression |

| Depression | 788120007 | Antenatal depression |

| Depression | 790961000000101 | Antenatal depression |

| Depression | 231504006 | Anxiety depression |

| Depression | 191659001 | Atypical depressive disorder |

| Depression | 191627008 | Bipolar affective disorder, current episode depression |

| Depression | 191634005 | Bipolar affective disorder, currently depressed, in full remission |

| Depression | 192080009 | Chronic depression |

| Depression | 14183003 | Chronic major depressive disorder, single episode |

| Depression | 357705009 | Cotard syndrome |

| Depression | 35489007 | Depressed |

| Depression | 196381000000100 | Depression resolved |

| Depression | 191495003 | Depressive disorder caused by drug |

| Depression | 698957003 | Depressive disorder in remission |

| Depression | 78667006 | Depressive neurosis |

| Depression | 300706003 | Endogenous depression |

| Depression | 191608002 | Endogenous depression - recurrent |

| Depression | 274948002 | Endogenous depression - recurrent |

| Depression | 231499006 | Endogenous depression first episode |

| Depression | 321717001 | Involutional depression |

| Depression | 370143000 | Major depression |

| Depression | 63412003 | Major depression in complete remission |

| Depression | 30605009 | Major depression in partial remission |

| Depression | 42810003 | Major depression in remission |

| Depression | 70747007 | Major depression single episode, in partial remission |

| Depression | 36923009 | Major depression, single episode |

| Depression | 19527009 | Major depression, single episode, in complete remission |

| Depression | 42925002 | Major depressive disorder, single episode with atypical features |

| Depression | 69392006 | Major depressive disorder, single episode with catatonic features |

| Depression | 63778009 | Major depressive disorder, single episode with melancholic features |

| Depression | 25922000 | Major depressive disorder, single episode with postpartum onset |

| Depression | 430852001 | Major depressive disorder, single episode, severe with psychotic features |

| Depression | 231500002 | Masked depression |

| Depression | 87512008 | Mild major depression |

| Depression | 79298009 | Mild major depression, single episode |

| Depression | 237349002 | Mild postnatal depression |

| Depression | 40379007 | Mild recurrent major depression |

| Depression | 720454007 | Minimal major depression one episode |

| Depression | 310496002 | Moderate depression |

| Depression | 832007 | Moderate major depression |

| Depression | 15639000 | Moderate major depression, single episode |

| Depression | 16266831000119100 | Moderate major depressive disorder co-occurrent with anxiety single episode |

| Depression | 18818009 | Moderate recurrent major depression |

| Depression | 719593009 | Moderately severe depression |

| Depression | 720453001 | Moderately severe major depression one episode |

| Depression | 413169006 | On depression register |

| Depression | 1153575004 | Persistent depressive disorder |

| Depression | 58703003 | Postnatal depression |

| Depression | 104851000119103 | Postpartum major depression in remission |

| Depression | 231485007 | Post-schizophrenic depression |

| Depression | 426578000 | Premenstrual dysphoric disorder in remission |

| Depression | 191455000 | Presenile dementia with depression |

| Depression | 192049004 | Prolonged depressive adjustment reaction |

| Depression | 765176007 | Psychosis and severe depression co-occurrent and due to bipolar affective disorder |

| Depression | 73867007 | Psychotic depression |

| Depression | 191676002 | Psychotic reactive depression |

| Depression | 87414006 | Reactive depression |

| Depression | 288751000119101 | Reactive depressive psychosis, single episode |

| Depression | 40568001 | Recurrent brief depressive disorder |

| Depression | 191616006 | Recurrent depression |

| Depression | 1089641000000100 | Recurrent depression with current moderate episode |

| Depression | 1089511000000100 | Recurrent depression with current severe episode and psychotic features |

| Depression | 66344007 | Recurrent major depression |

| Depression | 46244001 | Recurrent major depression in complete remission |

| Depression | 33135002 | Recurrent major depression in partial remission |

| Depression | 68019004 | Recurrent major depression in remission |

| Depression | 268621008 | Recurrent major depressive episodes |

| Depression | 764691000000109 | Recurrent major depressive episodes, in partial remission |

| Depression | 764701000000109 | Recurrent major depressive episodes, in remission |

| Depression | 191610000 | Recurrent major depressive episodes, mild |

| Depression | 191611001 | Recurrent major depressive episodes, moderate |

| Depression | 764611000000100 | Recurrent major depressive episodes, severe |

| Depression | 191613003 | Recurrent major depressive episodes, severe, with psychosis |

| Depression | 413170007 | Removed from depression register |

| Depression | 247803002 | SAD - Seasonal affective disorder |

| Depression | 84760002 | Schizoaffective disorder, depressive type |

| Depression | 191459006 | Senile dementia with depression |

| Depression | 310497006 | Severe depression |

| Depression | 450714000 | Severe major depression |

| Depression | 75084000 | Severe major depression without psychotic features |

| Depression | 251000119105 | Severe major depression, single episode |

| Depression | 77911002 | Severe major depression, single episode, with psychotic features, mood-congruent |

| Depression | 20250007 | Severe major depression, single episode, with psychotic features, mood-incongruent |

| Depression | 76441001 | Severe major depression, single episode, without psychotic features |

| Depression | 237350002 | Severe postnatal depression |

| Depression | 28475009 | Severe recurrent major depression with psychotic features |

| Depression | 36474008 | Severe recurrent major depression without psychotic features |

| Depression | 764711000000106 | Single major depressive episode, in remission |

| Depression | 191601008 | Single major depressive episode, mild |

| Depression | 191604000 | Single major depressive episode, severe, with psychosis |

| Depression | 1153570009 | Treatment resistant depression |

| Depression review | 413972000 | Depression annual review |

| Depression review | 413973005 | Depression interim review |

| Depression review | 883491000000106 | Did not attend depression review |

| Depression symptoms | 871840004 | Depressive episode |

| Depression symptoms | 394924000 | Depressive symptoms |

Mental health related A&E attendances,

A&E attendance counts are sourced from NHS datasets ECDS – Emergency Care Dataset (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-collections-and-data-sets/data-sets/emergency-care-data-set-ecds). Mental health related A&E attendances were defined as all attendances at any A&E department that included a set of SNOMED codes found in any position. The set of codes were derived from a comprehensive search of SNOMED dictionary terms. These are include several thousand codes because of the length of the list we have not included all of them here. The numbers of codes found by comprehensive search in the SNOMED catalogues are in Table A. 2.

Table A. 2.

Number of SNOMED codes for every category of mental health condition searched.

| condition | Number of SNOMED codes |

|---|---|

| Alcohol abuse | 338 |

| Suicide and self-harm | 552 |

| Eating disorders | 79 |

| Substance abuse | 2353 |

| Other (depression, severe mental illness) | 349 |

In practice, despite the large number of codes, only few of these were used in ECDS records. In the following tables we list the codes found 2018–2023 in Cheshire and Merseyside. If codes were used in less than 10 records, we have not reported them here.

Table A. 3.

SNOMED codes used to define mental health related A&E attendances.

| SNOMED code | Description |

|---|---|

| 25702006 | Alcohol intoxication (disorder) |

| 85561006 | Uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal (disorder) |

| 66590003 | Alcohol dependence (disorder) |

| 308742005 | Alcohol withdrawal-induced convulsion (disorder) |

| 67426006 | Toxic effect of alcohol (disorder) |

| 191480000 | Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (disorder) |

| 276853009 | Deliberate self-injury |

| 72366004 | Eating disorder |

| 56882008 | Anorexia nervosa |

| 77675002 | Anorexia nervosa, restricting type |

| 66214007 | Substance misuse |

| 1156755000 | Poisoning caused by gaseous substance (disorder) |

| 295124009 | Paracetamol overdose |

| 295830007 | Overdose of antidepressant drug (disorder) |

| 307052004 | Illicit drug use |

| 242253008 | Narcotic overdose |

| 296015009 | Sedative overdose |

| 295217003 | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory overdose |

| 296335002 | Overdose of beta-adrenergic blocking drug (disorder) |

| 296938005 | Iron product overdose (disorder) |

| 296355001 | Overdose of calcium-channel blockers (disorder) |

| 242824002 | Intentional paracetamol overdose |

| 43302000 | Anticoagulant overdose |

| 295125005 | Accidental acetaminophen overdose |

| 69322001 | Psychotic disorder |

| 13746004 | Bipolar disorder (disorder) |

| 25702006 | Alcohol intoxication (disorder) |

| 85561006 | Uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal (disorder) |

| 66590003 | Alcohol dependence (disorder) |

| 308742005 | Alcohol withdrawal-induced convulsion (disorder) |

| 67426006 | Toxic effect of alcohol (disorder) |

| 191480000 | Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (disorder) |

| 25702006 | Alcohol intoxication (disorder) |

| 66590003 | Alcohol dependence (disorder) |

| 85561006 | Uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal (disorder) |

| 308742005 | Alcohol withdrawal-induced convulsion (disorder) |

| 191480000 | Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (disorder) |

| 67426006 | Toxic effect of alcohol (disorder) |

| 276853009 | Deliberate self-injury |

| 72366004 | Eating disorder |

| 56882008 | Anorexia nervosa |

| 77675002 | Anorexia nervosa, restricting type |

| 66214007 | Substance misuse |

| 1156755000 | Poisoning caused by gaseous substance (disorder) |

| 295124009 | Paracetamol overdose |

| 295830007 | Overdose of antidepressant drug (disorder) |

| 307052004 | Illicit drug use |

| 242253008 | Narcotic overdose |

| 296015009 | Sedative overdose |

| 295217003 | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory overdose |

| 296335002 | Overdose of beta-adrenergic blocking drug (disorder) |

| 296938005 | Iron product overdose (disorder) |

| 296355001 | Overdose of calcium-channel blockers (disorder) |

| 242824002 | Intentional paracetamol overdose |

| 43302000 | Anticoagulant overdose |

| 295125005 | Accidental acetaminophen overdose |

| 295124009 | Paracetamol overdose |

| 295830007 | Overdose of antidepressant drug (disorder) |

| 307052004 | Illicit drug use |

| 242253008 | Narcotic overdose |

| 295217003 | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory overdose |

| 296015009 | Sedative overdose |

| 296335002 | Overdose of beta-adrenergic blocking drug (disorder) |

| 69322001 | Psychotic disorder |

| 13746004 | Bipolar disorder (disorder) |

| 69322001 | Psychotic disorder |

| 13746004 | Bipolar disorder (disorder) |

Mental health related emergency admissions

The ICD-10 codes used in this work were cross checked using clinical codes list repository [1] and phenotype library [2], with background from WHO specification [3] and symptoms companion [4]. Mental health related emergency admissions were defined, using Secondary Uses Services (SUS) admitted patient care spell (APCS) tables (https://digital.nhs.uk/services/secondary-uses-service-sus) as any emergency [Admission_Method = 2], admission including any of the following codes in any diagnostic position.

Table A. 4.

ICD-10 codes used to query diagnostic fields in SUS APCS to identify clusters of mental health disorders.

| Disorder cluster | ICD-10 code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Self-harm [5,6,7] | ||

| X60-X84 | Intentional self-harm | |

| Y10-Y34 | Injury/poisoning of indeterminate intent | |

| Alcohol [5,6] | ||

| F10 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to the use of alcohol | |

| X45 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to alcohol | |

| X65 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to alcohol | |

| Y15 | Poisoning by exposure to alcohol of indeterminate intent | |

| Drugs and substance [5,6] | ||

| F11-F19 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (excluding alcohol) | |

| T36-T50 | Poisoning by drugs, medicaments and biological substances | |

| Eating disorders [3,4] | ||

| F50 | Eating disorders | |

| F98.2 | Feeding disorders of infancy and childhood | |

| F98.3 | Pica of infancy and childhood | |

| Other mental disorders [3,4] | ||

| F20-F29 | Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders | |

| F30-F39 | Mood [affective] disorders | |

| F40-F48 | Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders | |

| F51-F59 | Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (excl. eating disorders) | |

| F60-F69 | Disorders of adult personality and behaviour | |

| F70-F79 | Mental retardation | |

| F80-F89 | Disorders of psychological development | |

| F90-F98 | Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | |

| F99 | Unspecified mental disorder | |

| R45.8 | Other symptoms and signs involving emotional state: Suicidal ideation (tendencies) | |

Appendix 2. Outcomes before and after the CAP intervention

Appendix 3. Comparison of the GP practice characteristics of two groups defined by the upper and lower quartiles of their predicted receipt of CAP based on our IV – the rank of GP practices historical referral rate

Table A. 5.

Comparison of the GP practice characteristics: Adjusted.

| High uptake (quartile 4) | High uptake (quartile 4) | |

|---|---|---|

| The percentage of all QOF points achieved across all domains as a proportion of all achievable points. | 87 | 87 |

| % who have a positive experience of their GP practice | 85 | 83 |

| The average number of appointments per registered patients | 5 | 5 |

| The number of full time equivalent clinical staff per 10,000 patients | 15 | 15 |

| The % of patients reporting a long standing illness | 54 | 54 |

Measures are adjusted for the control variables included in our models using inverse probability weights, for the inverse probability the predicted receipt of CAP based on our IV.

Table A. 6.

Comparison of the GP practice characteristics: Unadjusted.

| High uptake (quartile 4) | High uptake (quartile 4) | |

|---|---|---|

| The percentage of all QOF points achieved across all domains as a proportion of all achievable points. | 88 | 88 |

| % who have a positive experience of their GP practice | 85 | 83 |

| The average number of appointments per registered patients | 6 | 5 |

| The number of full time equivalent clinical staff per 10,000 patients | 15 | 15 |

| The % of patients reporting a long standing illness | 57 | 53 |

QOF – Quality and Outcomes Framework - https://qof.digital.nhs.uk/

Appendix 4. Full model output

Table A. 7.

Full model output.

| model 1.1 | model 1.2 | model 2.1 | model 2.2 | model 3.1 | model 3.2 | model 4.1 | model 4.2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV stages | First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | First | Second |

| Dependent Var.: | cap_household | ad_adqs | cap_household | num_gp_consultations | cap_household | aae_mh | cap_household | emadm_mh |

| Constant | 0.0206∗∗∗ (0.0024) | −1.091∗∗∗ (0.2820) | 0.0276∗∗∗ (0.0024) | −0.0088∗∗ (0.0027) | 0.0279∗∗∗ (0.0023) | 0.0003 (0.0005) | 0.0198∗∗∗ (0.0025) | 0.0012 (0.0008) |

| Rank of 2017-19 GP practice uptake (IV) | 0.0002∗∗∗ (1.37e-5) | 0.0002∗∗∗ (1.45e-5) | 0.0002∗∗∗ (1.41e-5) | 0.0002∗∗∗ (1.38e-5) | ||||

| age | −0.0009∗∗∗ (5.6e-5) | 0.0767∗∗∗ (0.0082) | −0.0009∗∗∗ (5.56e-5) | 0.0009∗∗∗ (7.1e-5) | −0.0008∗∗∗ (5.6e-5) | −5.9e-6 (1.18e-5) | −0.0008∗∗∗ (5.59e-5) | −0.0003∗∗∗ (2.06e-5) |

| Age squared | 9.66e-6∗∗∗ (6.1e-7) | −0.0007∗∗∗ (8.99e-5) | 1.03e-5∗∗∗ (6.06e-7) | −1.2e-5∗∗∗ (8.14e-7) | 9.22e-6∗∗∗ (6.09e-7) | −4.53e-8 (1.32e-7) | 8.94e-6∗∗∗ (6.09e-7) | 4.6e-6∗∗∗ (2.28e-7) |

| Sex (Male) | 0.0019∗∗ (0.0006) | −0.5260∗∗∗ (0.0630) | 0.0016∗∗ (0.0006) | −0.0087∗∗∗ (0.0006) | 0.0014∗ (0.0006) | 8.01e-5 (0.0001) | 0.0014∗ (0.0006) | −0.0005∗∗∗ (0.0002) |

| Depression | 0.0349∗∗∗ (0.0012) | 2.184∗∗∗ (0.2791) | 0.0238∗∗∗ (0.0013) | 0.0541∗∗∗ (0.0018) | 0.0424∗∗∗ (0.0012) | 0.0026∗∗∗ (0.0004) | 0.0408∗∗∗ (0.0012) | 0.0071∗∗∗ (0.0008) |

| Indices of Multiple Deprivation | 0.0006∗∗∗ (1.7e-5) | 0.0157∗∗ (0.0052) | 0.0007∗∗∗ (1.6e-5) | 0.0002∗∗∗ (4.69e-5) | 0.0007∗∗∗ (1.65e-5) | 3.04e-5∗∗∗ (7.89e-6) | 0.0006∗∗∗ (1.89e-5) | 5.11e-5∗∗∗ (1.35e-5) |

| Antidepressants ADQ 2018–2020 per person | −9.79e-6∗∗∗ (1.08e-6) | 0.0102∗∗∗ (0.0001) | ||||||

| Antidepressants (ADQ) per person Quarter before intervention | 0.0003∗∗∗ (1.07e-5) | 0.5452∗∗∗ (0.0021) | ||||||

| GP practice average antidepressant ADQs per patient 2018–2020 | 5.64e-5∗∗∗ (9.57e-6) | 0.0077∗∗∗ (0.0011) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 0.0147∗∗∗ (0.0011) | 1.628∗∗∗ (0.1470) | 0.0064∗∗∗ (0.0011) | 0.0379∗∗∗ (0.0011) | 0.0179∗∗∗ (0.0011) | 0.0007∗∗ (0.0002) | 0.0173∗∗∗ (0.0011) | 0.0036∗∗∗ (0.0004) |

| Severe Mental Illness | 0.0306∗∗∗ (0.0029) | 1.713∗∗∗ (0.3581) | 0.0385∗∗∗ (0.0029) | 0.0032 (0.0035) | 0.0350∗∗∗ (0.0029) | 0.0048∗∗∗ (0.0006) | 0.0311∗∗∗ (0.0029) | 0.0109∗∗∗ (0.0009) |

| Substance or alcohol misuse | 0.0185∗∗∗ (0.0017) | 0.3379 (0.2150) | 0.0182∗∗∗ (0.0017) | 0.0194∗∗∗ (0.0019) | 0.0182∗∗∗ (0.0017) | 0.0069∗∗∗ (0.0003) | 0.0174∗∗∗ (0.0017) | 0.0101∗∗∗ (0.0006) |

| % reporting difficulty accessing GP practice | −0.0002∗∗∗ (2.57e-5) | −0.0059∗ (0.0027) | −0.0002∗∗∗ (2.55e-5) | 3.58e-6 (2.43e-5) | −0.0002∗∗∗ (2.56e-5) | 1.58e-6 (4.33e-6) | −0.0002∗∗∗ (2.59e-5) | −3.98e-6 (6.92e-6) |

| Household received CAP | −15.21∗ (7.118) | −0.1899∗∗ (0.0592) | −0.0227∗ (0.0093) | −0.0101 (0.0187) | ||||

| GP consultations 2018–2020 | 0.0009∗∗∗ (0.0002) | 0.0075∗∗∗ (0.0002) | ||||||

| GP practice average GP consultations 2018–2020 | −0.0096∗∗∗ (0.0014) | 0.0214∗∗∗ (0.0012) | ||||||

| GP consultations Quarter before intervention | 0.0863∗∗∗ (0.0012) | 0.2117∗∗∗ (0.0052) | ||||||

| A&E attendances 2018–2020 | 0.0042∗∗∗ (0.0012) | 0.0203∗∗∗ (0.0002) | ||||||

| GP practice average A&E attendances per 1000 people 2018–2020 | −0.5119∗∗∗ (0.0373) | −0.0118. (0.0066) | ||||||

| A&E attendances Quarter before intervention | 0.0617∗∗∗ (0.0052) | 0.2161∗∗∗ (0.0010) | ||||||

| Emergency admissions 2018–2020 | 0.0042∗∗∗ (0.0005) | 0.0146∗∗∗ (0.0001) | ||||||

| GP practice average emergency admissions 2018–2020 | 0.0474∗∗∗ (0.0126) | 0.0122∗∗∗ (0.0035) | ||||||

| Emergency admissions Quarter before intervention | 0.0821∗∗∗ (0.0034) | 0.1226∗∗∗ (0.0018) | ||||||

| ________________________________________ | _____________________ | ____________________ | ____________________ | ____________________ | ____________________ | ____________________ | ____________________ | ____________________ |

| S.E. type | IID | IID | IID | IID | IID | IID | IID | IID |

| F-test (1st stage) | 182.72 | – | 227.64 | – | 308.11 | – | 184.44 | – |

| F-test (1st stage), cap_household | – | 182.72 | – | 227.64 | – | 308.11 | – | 184.44 |

| F-test (1st stage), p-value | 1.26E-41 | – | 2.01E-51 | – | 5.94E-69 | – | 5.31E-42 | – |

| F-test (1st stage), p-value, cap_household | – | 1.26E-41 | – | 2.01E-51 | – | 5.94E-69 | – | 5.31E-42 |

| Wu-Hausman | – | 5.9347 | – | 15.299 | – | 6.464 | – | 0.69958 |

| Wu-Hausman, p-value | – | 0.01485 | – | 0.0000918 | – | 0.01101 | – | 0.40293 |

Appendix 5. Relationship between decile of practice uptake in 2017–2019 (our instrument) and 2020–2023 uptake of CAP

Appendix 6. Estimates for each quarter of follow up

Appendix 7. Estimates only including individuals accessing CAP directly in the intervention group

Table A. 8.

Estimated effect of the CAP intervention on four mental health related outcomes per quarter based on two stage least squares instrumental variable regression, for individuals directly accessing CAP.

| Outcome |

95 % CI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect on individual receiving CAP | Estimate | Lower | upper | P value |

| Anti-depressants (per person) | −35.2 | −69.2 | −1.3 | 0.042 |

| MH GP consultations (per 1000) | −424.7 | −720.9 | −128.6 | 0.005 |

| MH A&E attendances (per 1000) | −57.6 | −110.1 | −5.1 | 0.031 |

| MH emergency admission (per 1000) | −36.8 | −131.2 | 57.6 | 0.445 |

Appendix 8. Estimates effect on all cause A&E attendances and Emergency admission

Table A. 9.

Estimated effect of the CAP intervention on all cause A&E attendances and Emergency admission per quarter based on two stage least squares instrumental variable regression.

| Outcome |

95 % CI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect on household member receiving CAP | Estimate | Lower | upper | P value |

| All cause A&E attendances (per 1000) | −142.9 | −181.8 | −33.7 | 0.01 |

| All cause emergency admission (per 1000) | 28.7 | 11.1 | 84.0 | 0.28 |

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- Adams J., White M., Moffatt S., Howel D., Mackintosh J. A systematic review of the health, social and financial impacts of welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrist J.D., Pischke J.-S. Princeton university press; 2009. Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist's companion. [Google Scholar]

- Barr B., Taylor-Robinson D., Stuckler D., Loopstra R., Reeves A., Whitehead M. ‘First, do no harm’: Are disability assessments associated with adverse trends in mental health? A longitudinal ecological study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2016;70:339–345. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J.M., Altman D.G. Statistics notes: Bootstrap resampling methods. BMJ. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman J., Dogra N., Hindley P. Mental health and poverty in the UK–time for change? BJPsych International. 2015;12:27–28. doi: 10.1192/s2056474000000210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs A.H., Gray A.M. Handling uncertainty in economic evaluations of healthcare interventions. BMJ. 1999;319:635–638. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookhart M.A., Schneeweiss S. Preference-based instrumental variable methods for the estimation of treatment effects: Assessing validity and interpreting results. International Journal of Biostatistics. 2007;3 doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]