Summary

The rapid development of China's 5G ‘Internet Plus’ industry has led to increasing use of the Internet to provide healthcare services. Internet-based services in China are already widely used to prevent, identify, monitor, and manage mental disorders, but few of these services have been formally evaluated. To provide a clear baseline of this rapidly evolving field, we searched articles published before December 31, 2022, about internet-based interventions and surveys for mental health-related conditions in China in five international databases (Web of Science, PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase, and Cochrane Library) and four Chinese databases (CNKI, SinoMed, VIP, and WanFang). The 143 identified studies—54 in Chinese and 89 in English—described internet-based interventions and surveys in individuals with mental disorders, community residents, college students, older adults, pregnant women, and health professionals. The number of identified studies, which were mainly conducted in economically developed regions of the country, quadrupled after the 2019 onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Available studies suggest—but do not prove—that internet-based interventions can reduce the severity of psychiatric symptoms, decrease healthcare costs, and improve the quality of life for individuals with mental disorders. Innovative smartphone applications could potentially improve the quality and expand the scope of internet-based interventions, making them a key component in ongoing efforts to prevent and monitor mental illness, enhance the self-management of mental disorders, and alleviate psychological distress among adolescents and other at-risk populations. However, achieving this long-term goal will require establishing standardised methods of administering internet-based interventions, training mental health professionals to implement and monitor the interventions, identifying methods of maintaining the confidentiality of collected information, and rigorously assessing the effectiveness of the interventions based on periodic assessment of uniform outcome measures. Clinical and policy research about expanding internet-based mental health interventions should focus on confidentiality, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness.

Keywords: Mental health, Internet-based treatment, Management of mental disorders, Digital hospital, China's mental health care

Introduction

Rationale

The rapid development of China's 5 G' Internet Plus' industry has been associated with a correspondingly rapid increase in internet use to provide healthcare services. In 2021, the national government's annual work report considered standards for promoting ‘Internet plus Health care’ for the first time, indicating the increasing importance of the internet-based medical industry.1

As internet technologies continue their rapid development, the mental health applications of these technologies are increasing. If used appropriately, these technologies could help meet the challenge of simultaneously expanding the coverage and improving the quality of mental health services. These internet-based mental health applications would be particularly beneficial in communities with limited mental health services and among community members reluctant to use available mental health services due to the ongoing stigmatisation of mental illnesses. In China, internet-based services are already used to prevent, identify, monitor, and manage mental disorders.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 However, the availability, utilisation, and methods of assessing the effectiveness of these internet-based mental health services remain unknown.

Due to the uneven distribution of medical facilities, human resources, and information systems, one of the most significant challenges facing mental health services in China is reducing the inequity in the rural versus urban distribution of services. Expanding internet-based services is one potential way to address this long-standing problem rapidly. According to the China Digital Rural Development Report 2022,9 the number of rural Internet users has reached 293 million, which translates to a rural internet penetration rate of 58·8%. This more than doubled the rural penetration rate reported in 2016 (at the beginning of China's 13th Five-Year Plan) and substantially decreased the gap in internet coverage between urban and rural communities. By September 2022, all 33 province-level administrative regions in China, 85% of prefectures and cities, and 69% of districts and counties had set up regional information platforms for universal health care.9

Seven previous reviews about internet-based interventions for specific mental disorders included studies conducted in China, three about depression,2, 3, 4 two about insomnia,5,6 one about post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),7 and one about multiple mental disorders.8 Five of the reviews published in English-language databases included a few studies from China.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 The review about internet interventions in China for PTSD7 (published in 2012), focused on barriers to help-seeking for PTSD, not on internet-based services for PTSD. A 2021 review included 39 intervention studies conducted in mainland China that used ‘digital health technologies’8; many of the included studies were computerised programs or virtual reality interventions, not internet-based interventions. Thus, the available literature does not reflect the current dynamic nature of mental health-related internet-based interventions in greater China, nor does it consider the role of internet-based services during the COVID-19 epidemic.

A scoping review is needed to map the rapidly changing landscape of mental health-related internet services in China and to identify available literature about the use and evaluation of these services. Such a review could provide policymakers and mental health practitioners with a synthesis of currently available information on this topic and identify areas where increased investment in and expanded monitoring of this increasingly important component of China's mental health service network are needed.

Objectives

This scoping review aims to systematically map currently available research and other information sources about the use of the internet in China to identify and treat individuals with mental disorders or to provide psychological support services to prevent mental disorders in different types of community residents. The review will also highlight critical gaps in the current knowledge about this rapidly evolving field. The interventions and surveys considered in this review are limited to those based on smartphone or internet technology, not including computerised interventions or interventions based on new digital technologies, such as virtual reality technology. The specific questions addressed in the review are:

-

1)

What is the current use of internet-based services to prevent, identify, monitor, and manage mental health problems in China?

-

2)

What methods have been used to assess the effectiveness of internet-based evaluation and treatment services for mental disorders in China, and what is the quality of these studies?

Methods

Protocol and registration

The study protocol was draughted based on the methods described in the checklist of the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR).10 The article search strategy, article selection criteria, and the list of data items extracted from selected documents were revised based on the findings of a pilot study. The final protocol was registered prospectively with the Open Science Framework on August 10, 2021. OSF Registration: 10.17605.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies that fulfilled the following criteria.

-

➢

Participants: the general population or individuals with mental disorders who live in China.

-

➢

Intervention/Exposure: internet-based education, screening, assessment, or treatment related to mental health conditions aimed at improving knowledge about mental illnesses, identifying individuals at risk for mental disorders, providing psychological counselling, providing crisis support for psychological emergencies (such as suicidal ideation), preventing mental illness in high-risk individuals, and monitoring the ongoing management of persons with mental disorders.

-

➢

Outcomes: description of all types of mental health services provided via the internet, level of utilisation of these services, methods used to evaluate the effectiveness of the services, and quality of studies that report on the effectiveness of the services.

-

➢

Study design: observational studies, intervention studies, and qualitative studies, that collect and report primary data.

We excluded studies if:

-

➢

The report was a protocol or only an abstract without a corresponding full article.

-

➢

The study was not published in English or Chinese.

-

➢

The study was not conducted in China.

-

➢

The study was about animal models of mental illness or only involved analysis of genetic materials.

-

➢

The study did not report any predefined outcomes.

-

➢

The study was a review, meta-analysis, or systematic review that only reports secondary data.

Search strategy

Five English-language databases (Web of Science, PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase, and Cochrane Library) and four Chinese-language databases (CNKI, VIP, SinoMed, and WanFang) were used to search for relevant peer-reviewed publications published before December 31, 2022. Chinese dissertations and theses related to this topic were identified from the corresponding section of the CNKI database. The complete electronic search strategies for the five English-language and the four Chinese-language databases are presented in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Material.

We also considered searching for documents published in three English-language pre-print databases: medRxiv [https://www.medrxiv.org/search], PsyArXiv [https://psyarxiv.com], and Peerj [https://peerj.com/subjects/public-health/]. However, a preliminary search of these databases identified no relevant papers, so these databases were not considered in the final search.

We inspected the reference list of eligible papers to identify studies that met inclusion criteria which were not identified in the electronic searches of the databases.

Selection of sources of evidence

Two independent reviewers screened all studies identified by the electronic searches. After the initial screening of the titles and abstracts, two independent reviewers conducted a second, full-text screening of potentially eligible articles to decide which articles should be included in the analysis. Any disagreements about inclusion were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers or, if they could not reach a consensus, by a third (senior) reviewer.

Data charting process

The final data-charting form and coding instructions (shown in Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials) were then used to code all eligible papers. Two reviewers independently coded each paper and discussed disagreements about any items in the data-charting form; if a consensus was not reached, a third (senior) reviewer made the final decision. Some variables coded from the original papers (including the intervention's implementation dates, sample size, participants' age, educational status, etc.) were subsequently categorised when summarising the results.

Data items

Extracted information included data about the following seven issues:

-

1)

Characteristics of the study/report (author, institution, full article citation, date of publication, type of data [research study, research report, thesis, or government report], study design, period (s) report refers to, geographic region(s) covered [national, provincial, municipal], urban versus rural community, sampling method, etc.)

-

2)

Types of participants in the study/report: (all community members, specific population cohorts [e.g., children, adolescents, elderly, etc.], mentally ill individuals, family members of mentally ill individuals, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, social workers, etc.)

-

3)

Characteristics of participants: (age, gender, education, residence [urban vs. rural], access to in-person mental health services [community-based and hospital-based])

-

4)

Types of mental health problems considered: (specific diagnosis [e.g., schizophrenia, depression] and/or a specific class of mental health condition [e.g., anxiety, psychosis, substance abuse, suicide, children's disorders, dementia, etc.])

-

5)

Specifics of the internet-based intervention (general education about mental health/illness, counselling, drug management, psychotherapy, monitoring, early identification, clinical follow-up, etc.)

-

6)

Method for assessing the outcome of the study

-

7)

The main finding of the study

Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence

We assessed the risk of bias for each of the 87 identified randomised controlled intervention trials using a modified version of the Cochrane Risk of Bias 1 tool (RoB1).11,12 As shown in Table 1, this tool considers seven different aspects of the study's design, conduct, and reporting; after assessing these specific items, the rater makes an overall judgement, classifying the risk of bias in the reported results as ‘low’, ‘moderate’, or ‘high’.

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment (based on a revised version of the Cochrane RoB tool 1) of the results reported in 87 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) about mental health-related internet-based interventions in China from 2000 to 2022.

| Risk of bias criteria and overall ratings | All years 2000–2022 (N = 87) n (%) |

Early period 2000.1–2015.12 (N = 9) n (%) |

Middle period 2016.1–2019.12 (N = 20) n (%) |

COVID period 2020.1–2022.12 (N = 58) n (%) |

Comparison of three time periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items used to assess risk of bias | |||||

| Abandoned the initially planned randomisation procedure during the study | 3 (3·4%) | 0 (0·0%) | 0 (0·0%) | 3 (5·2%) | p = 0·688a |

| Participants were assigned to treatment groups according to the order of admission | 4 (4·6%) | 0 (0·0%) | 1 (5·0%) | 3 (5·2%) | p = 1·000a |

| Unclear if true randomisation was used for the assignment of participants to treatment groups | 19 (21·8%) | 4 (44·4%) | 6 (30·0%) | 9 (15·5%) | p = 0·079a |

| Method of concealing allocation to treatment group not specified | 81 (93·1%) | 9 (100·0%) | 19 (95·0%) | 53 (91·4%) | p = 1·000a |

| Participants were not blinded to group allocation | 70 (80·5%) | 7 (77·8%) | 15 (75·0%) | 48 (82·8%) | p = 0·637a |

| Incomplete follow-up of participants | 2 (2·3%) | 0 (0·0%) | 0 (0·0%) | 2 (3·4%) | p = 1·000a |

| Did not report the reason for drop-outs | 11 (12·6%) | 1 (11·1%) | 4 (20·0%) | 6 (10·3%) | p = 0·481a |

| Overall rating of risk of bias | |||||

| Low risk | 12 (13·8%) | 2 (22·2%) | 2 (10·0%) | 8 (13·8%) | |

| Moderate risk | 32 (36·8%) | 3 (33·3%) | 6 (30·0%) | 23 (39·7%) | H = 1·49b (p = 0·475) |

| High risk | 43 (49·4%) | 4 (44·4%) | 12 (60·0%) | 27 (46·6%) |

Freeman-Halton extension of two-tailed Fisher Exact test.

Kruskal–Wallis rank test, H-value.

Synthesis of results

The review provides an overview of the current use of the internet in China to identify, treat, manage, prevent, and provide education about mental disorders. The papers were classified along two dimensions: 1) studies among individuals with mental disorders (subdivided by type of mental disorder) and studies in different cohorts of healthy community members (subdivided by type of community cohort), and 2) (within each of these target-group-specific groups of papers) intervention studies and cross-sectional surveys. This results in four groups of papers: clinical intervention studies, clinical surveys, non-clinical intervention studies, and non-clinical surveys. After describing the characteristics of all identified studies, we separately discuss the types of internet-based mental health activities undertaken in each of these four categories of studies and, to the extent possible, provide examples of the various kinds of activities. These reported activities include—but are not limited to—assessing the level of mental health literacy, providing education about mental health issues, screening for the presence of mental health disorders, providing direct (stand-alone) services to persons with less serious mental disorders, and monitoring and augmenting the follow-up treatment of persons who have received standard (in-person) services for relatively serious mental disorders. We also provide an assessment of the risk of bias in the 87 RCT intervention studies and a separate discussion of the 19 studies focused on assessing or reducing the mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The PRISMA Checklist for Scoping Reviews for this manuscript is shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

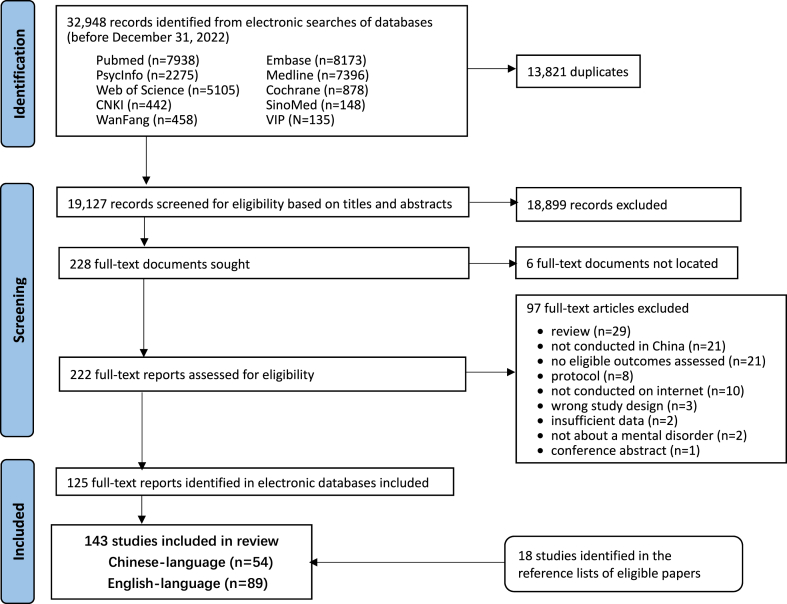

Fig. 1 shows the results of the electronic search of the ten databases. In total, 32,948 records were identified, including 13,821 duplicates and 18,899 records that were subsequently excluded by screening the titles and abstracts. The full text for six of the remaining 228 documents was not located, so 222 full-text documents were screened for eligibility. After excluding 97 papers, 125 full-text reports were included in the review. A subsequent review of the reference lists of these included papers identified an additional 18 reports meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria that had not been identified in the electronic searches. A total of 143 eligible reports—54 in English and 89 in Chinese—are included in this review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the scoping review about internet-based mental health interventions and surveys in China.

Characteristics of the identified studies

Supplementary Table S5 provides detailed descriptions of all 143 included studies. As shown in Fig. 2, the studies were published between 2001 and 2022, but only 5 publications appeared in the 11 years from 2001 to 2011, while 138 publications appeared in the 11 years from 2012 to 2022. Moreover, during the COVID-19 era, the number of publications about internet-based mental health interventions doubled from 2019 to 2020 and then redoubled from 2021 to 2022. These studies included 87 (60·8%) randomised controlled intervention trials (RCT),13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40,41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60,61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99 22 (15·4%) cross-sectional studies,100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121 18 (12·6%) pre-post studies,122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139 11 (7·7%) non-randomised controlled trials,140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150 2 (1·4%) longitudinal studies,151,152 2 (1·4%) non-intervention randomised crossover studies,153,154 and 1 (0·7%) cohort study.155 The proportion of RCT in the pre-COVID era from 2001 to 2019 (61·7% [29/47]) was similar to the proportion during the COVID era from 2020 to 2022 (60·4% [58/96]).

Fig. 2.

Number of reports about internet-based mental health interventions and surveys conducted in China from 2001 to 2022.

As shown in Fig. 3, the 143 studies included 19 (13·3%) nationwide studies and 124 (86·7%) regional studies conducted in 25 of China's 33 provincial-level administrative regions (hereafter, ‘provinces’). Two of the regional studies included study sites in two provinces,44,60 one in three provinces,46 and one in four provinces.112 The eight provinces that did not conduct regional studies included Gansu, Jilin, Liaoning, Macau, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Most of the studies were conducted in the economically developed parts of the country, primarily in the eastern and southern provinces; relatively few studies were conducted in the western and northern parts of the country. Moreover, 105 (73·4%) of the studies were undertaken exclusively in urban communities, while 27 (18·9%) were conducted in both urban and rural communities, and only 4 (2·8%) were exclusively conducted in rural communities. (The remaining 7 studies did not provide information about the location of the participating communities). In most provinces, RCTs accounted for at least half of all studies; the exceptions (where RCTs accounted for less than 50% of studies) were Hainan, Hong Kong, Hunan, Jiangsu, Macau, and Taiwan.

Fig. 3.

Location of 143 studies about internet-based mental health interventions and surveys in China: 2001–2022∗. ∗For five regional (i.e., non-national) studies conducted in more than one province, fractional amounts are computed for the participating provinces so that each study is counted only once. Eight province-level administrative regions did not conduct province-specific studies: Gansu, Jilin, Liaoning, Macau, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Tibet, and Xinjiang.

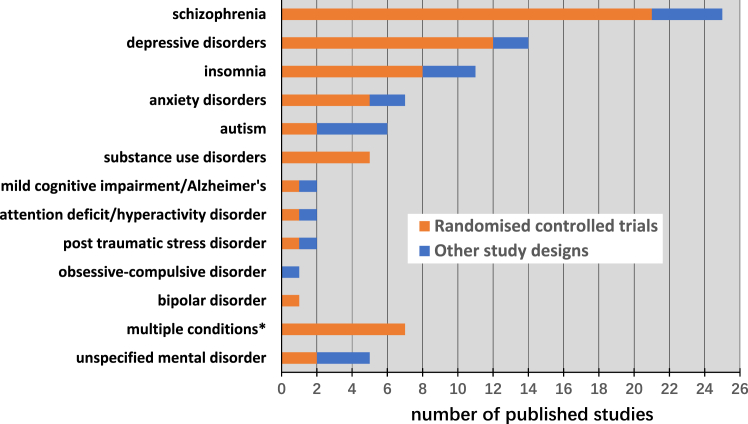

The 143 studies included 88 (61·3%) interventions and surveys for individuals with different types of mental disorders, 52 (36·4%) interventions and surveys of different cohorts of healthy community members, and 3 (2·1%) miscellaneous studies—a cross-sectional study that assessed mental health internet applications111 and two randomised crossover trials about the concordance of in-person and online administration of symptom scales.153,154 Internet-based studies about twelve specific mental disorders or conditions were identified (Fig. 4); the most frequently considered were schizophrenia (25 studies), depressive disorders (14 studies), insomnia (11 studies), anxiety disorders (7 studies), autism (6 studies), and substance used disorders (5 studies). There was only a single intervention study about three important disorders: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder, and bipolar disorder. Seven studies simultaneously considered multiple disorders, and five studies enrolled individuals with ‘mental illness’ or ‘serious mental illness’ without specifying the diagnosis or diagnoses. Among the 88 studies among individuals with mental disorders, 26 used ICD criteria to determine the diagnosis, 24 used DSM criteria, 9 used the (now defunct) 3rd edition of the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD-3), 14 used other diagnostic methods (including diagnostic-specific criteria and cutoff scores of symptom scales), and 14 did not report on the method of determining the diagnosis.

Fig. 4.

Number and type of 88 studies about internet-based interventions and surveys for different types of mental health disorders in China: 2001–2022. ∗Includes three studies about anxiety and depression; two studies about anxiety, depression, and insomnia; one study about insomnia, pain disorder, and eating disorder; and one study about autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

The 52 studies in non-clinical community cohorts targeted nine types of participants (Fig. 5); the most common target groups were college students (10 studies), healthcare workers (8 studies), the general population (7 studies), and pregnant or postnatal women (7 studies).

Fig. 5.

Number and type of 52 studies about internet-based mental health interventions and surveys in different cohorts of healthy individuals in China: 2001–2022. ∗Includes one study about individuals seeking general health services, one about persons who have been traumatised, one about individuals hospitalised during COVID-19, and one about adolescents at risk for depression.

The 82 intervention studies for individuals with mental disorders included 32 (39·0%) that were administered entirely over the internet (i.e., ‘pure’ models) and 50 (61·0%) that combined internet-based activities with face-to-face or telephone-based activities (i.e., ‘hybrid’ models). Among these 82 studies, 64 (78·0%) involved the participation of a mental health professional, 48 (58·3%) provided basic information about mental illnesses, 23 (28·3%) included medication monitoring, 35 (42·7%) used the WeChat platform, and 25 (30·5%) involved interactions between participants who used other social media networks. The corresponding results for the 34 intervention studies in no-patient cohorts were as follows: 28 (82·4%) were pure internet interventions, while 6 (17·6%) used hybrid models; 23 (67·6%) involved the participation of a mental health professional; 15 (44·1%) provided basic information about mental illnesses; 2 (6·9%) included medication monitoring (of the ill relatives of family-member participants), 9 (26·%) used the WeChat platform; and 7 (20·6%) included interactions between participants over social media networks.

The proportion of studies using the RCT design was much higher among studies in persons with mental disorders than among studies in non-clinical community cohorts (75·0% [66/88] vs. 40·4% [21/52], Chi = 16·54, p < 0·001).

Critical appraisal of the quality of randomised controlled trials about mental health-related internet-based interventions

We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB1) to assess the quality of the evidence reported in the 87 identified RCTs about mental health-related internet-based interventions; the summary of the results is shown in Table 1, and the detailed results are presented in Supplementary Table S6. The main methodological problems were that 93% of the reports did not clarify the method of concealing group allocation, and 22% were unclear about the randomisation method. In 85% of the studies, participants were not blinded to group assignment; this is a difficult issue to address in internet-based studies because it is only feasible to blind participants to the intervention when the control group is administered an alternative (‘placebo’) internet intervention. The overall risk of bias in the reported results was rated as high in 49% of the studies, moderate in 37%, and low in only 14%. As shown in Table 1, when considering three time periods (2000–2015, 2016–2019, and 2020–2022), there were no statistically significant changes over time in the prevalence of the specific problems identified in the ROB1 tool or the overall risk of bias in the studies. However, when combining the two pre-COVID time periods, there was a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of studies that were unclear about the method of randomisation, from 34·5% (10/29) in 2000–2019 to 15·5% (9/89) in 2020–2022 (Chi = 4·07, p = 0·044), though the prevalence of the other specific problems and the overall risk of bias were not significantly different in the studies from these two time periods. There was no significant difference in the overall risk of bias between the 67 RCTs in clinical populations (9 [13·4%] low risk, 23 [34·3%] moderate risk, and 35 [52·3%] high risk) and the 20 RCTs in non-clinical groups (4 [20·0%] low risk, 9 [45·0%] moderate risk, and 7 [35·0%] high risk) (Mann Whitney U = 791, p = 0·223).

Internet-based interventions and surveys of different clinical populations

Schizophrenia

Twenty-five internet-based studies for individuals with schizophrenia were included in this review, including twenty-one RCTs,13,16,18,24,30, 31, 32, 33,39,44,47,51,53,60,73,77,88,95, 96, 97, 98 two pre-post studies,136,137 one controlled trial,147 and one cross-sectional study.118 The cross-sectional study assessed the willingness of 400 community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia to use WeChat-based mental health services; it also compared 163 patients who regularly used the internet to 237 who did not regularly use the internet and found that those who regularly used the internet had less prominent depressive symptoms, better social functioning, and a higher quality of life.118 The average number of participants in the 24 intervention studies was 124 (range, 25–277) individuals, and the average duration of the intervention was 12·5 (range, 1–40) months. Only four of the studies included participants from rural communities. All of these intervention studies combined online services with routine clinical services; thus, they were all ‘hybrid’ interventions. These studies compared the internet-augmented clinical services to treatment as usual (TAU), which was variously reported as standard medication follow-up, regular outpatient visits, and periodic community follow-up. Three of the studies were published in English, 21 in Chinese.

Fifteen intervention studies reported the results of establishing a social messaging group on the WeChat platform.18,30, 31, 32, 33,39,44,47,53,60,73,88,95,97,98 Except for one study that focused on reminding patients to take their medication,97 all of the remaining WeChat groups were coordinated by a mental health professional. Nine of these WeChat groups30, 31, 32,39,44,60,88,95,98 provided patients with regular (usually monthly) post-hospitalisation follow-up, medication monitoring, recommendations about self-management, and on-demand consultation for urgent problems. Two WeChat groups that included both patients and their caregivers47,53 provided general information about the illness and specific advice about managing ongoing problems. Compared to patients who did not receive the WeChat intervention, those who received the intervention showed better social functioning, reduced relapse rates, and higher quality of life. Three studies conducted in inpatient settings18,33,73 found that augmenting routine treatment with a group WeChat platform discussing medication and other treatment-related issues resulted in better medication adherence, improved insight regarding the illness, reduced negative symptoms, and greater satisfaction with inpatient nursing care.

The remaining nine intervention studies that did not use the WeChat platform included two reports on a single RCT (at 6 months and 12 months) in rural communities that compared a waitlist condition to an intervention that combined mobile-texting reminders and educational messages with care supervision by lay health supporters13,77; at 6 months and 12 months the intervention group had higher medication adherence, reduced symptoms and better social functioning. A study that augmented routine care with a daily text message reminder to take medication24 reported a significantly lower two-year relapse rate. A study that compared one-year medication adherence in discharged patients provided regular telephone reminders, text-messaging reminders, or routine follow-up care51 found that adherence was significantly better in the telephone group than in the text-messaging group, but both the telephone and text-messaging groups had significantly better adherence than the routine follow-up group. A study that provided a one-year therapist-guided group therapy intervention16 (on a non-WeChat social network platform) reported improved symptoms and lower relapse rates than a community-based preventive intervention. A study that provided patients with web-based information tools about rehabilitation (without the assistance of a therapist)96 reported reduced relapse rates over the two-year follow-up. And two pre-post studies136,137 and one non-random controlled trial147 (all by the same research group) that augmented comprehensive outpatient treatment with an online on-demand consultation component reported symptomatic improvement in all three studies.

Depression

Fourteen studies on the effect of internet-based studies of patients with depression were identified, including 12 RCTs,27,40,49,61,64,65,71,76,81,83,90,91 one pre-post study,127 and one cohort study.155 The cohort study used a mobile phone app to augment the screening, referral, follow-up, and management of 3168 individuals with subthreshold depression over 12 months to identify those who developed major depressive disorder.155 The 13 intervention studies had an average sample size of 195 (range, 54–800) individuals and the average duration of the intervention was 5·5 (range, 1–25) months. Only three studies included participants from rural communities. Eight studies in individuals with major depressive disorder that used WeChat prompts reported decreased depressive and anxiety symptoms, better medication adherence, and improved activities of daily living.40,49,61,64,76,91,127,154 Four studies that provided depressed individuals with internet-based cognitive therapy found significantly greater symptomatic improvement in the intervention group compared to a waitlist control group and, importantly, no significant difference in the degree of improvement between the internet-based treatment group and depressed individuals who received in-person psychotherapy.65,81,83,90 One RCT compared three months of internet-based versus traditional telephone-based post-hospitalisation follow-up of individuals with depression27; it reported significantly better medication adherence, quality of life, positive attitude about the future, and overall satisfaction with the treatment outcome in the internet-based follow-up group.

Insomnia

Eleven studies considered internet-based interventions for insomnia, including eight RCTs,37,72,75,80,82,85,87,93 two pre-post studies,126,139 and one retrospective controlled trial.145 The average sample size was 730 (range, 60–6002) individuals, and the average duration of the intervention was 5·0 months, ranging from 1 week to 18 months. Only one of the studies included rural residents. Seven studies compared internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) with in-person CBT or pharmacotherapy48,72,75,80,82,93,139; the drug group had a more rapid onset of improvement in total sleep time and sleep efficiency (starting about four weeks after initiating treatment), but by the 8th week of treatment all three groups showed significant improvements in total sleep time and sleep efficiency. However, there was a non-significant greater improvement in the in-person CBT group compared to the iCBT group. One 14-month study in older patients with insomnia85 compared combined online WeChat-based cognitive behavioural therapy and music therapy to a control group that received telephone-based health education sessions reported significantly better post-intervention sleep quality in the intervention group than in the control group.

Anxiety and social anxiety

Seven studies focused on the potential effectiveness of internet-based mental health interventions for anxiety disorders, including five RCTs15,29,45,59,62 and two controlled trials.140,143 The average sample size was 128 (range, 44–255) individuals, and the average duration of the intervention was 7·6 (range, 3–14) weeks. Two of the studies included some rural participants. Five studies compared symptomatic changes in individuals with social anxiety between those using self-guided iCBT, therapist-guided iCBT, and remaining untreated on waitlists15,59,62,140,143; both iCBT groups experienced significantly greater improvement in social anxiety symptoms compared to the waitlist group, but there was no significant difference in the magnitude of the improvement between the self-guided and therapist-guided iCBT groups.

Autism

Six studies focused on internet-based studies about children with autism, including two RCTs,25,52 three pre-post studies,122,134,138 and one cross-sectional online autism screening study.109 The average sample size of the five intervention studies was 41 (range, 10–110) individuals, and the average duration of the intervention was 3·9 months, ranging from four days to one year. Only one of the studies included participants from rural communities. One of the RCTs52 compared a self-directed web-based learning platform for parents combined with weekly videoconferencing group coaching to the provision of the learning platform without the weekly group coaching and found significantly improved outcomes for both the parents and their children. A five-week uncontrolled pre-post study by An and colleagues122 used a mobile application that provided training in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) with five different levels of difficulty to train ten children with autism; two children achieved 50% accuracy in all five levels, five children achieved 50% accuracy in two levels, and three children achieved 50% accuracy in one level.

Substance dependence

Five RCTs, all conducted in urban centres, assessed internet-based treatments for substance use disorders.28,38,78,84,99 The average sample size was 61 (range, 40–100) participants, and the average duration of the intervention was 2·2 (range, 1–6) months. Three studies compared routine community-based care (TAU) for substance dependence to TAU augmented with one to six months of comprehensive internet-based health training (including daily text messages, surveys of cravings, and iCBT); they reported significantly reduced drug-positive rates and reduced number of days using drugs each week in the augmented TAU group.38,78,84 A study comparing TAU to an online computerised cognitive addiction therapy application99 reported significantly improved working memory in patients with drug use disorders who used the online application. However, another study28 reported that 46% (32/70) of individuals with substance use disorders preferred in-person interviews rather than an internet-based mHealth application (which assessed daily drug use and provided related health messages), indicating that work is still needed to increase patients' acceptance of internet-based mental health interventions for substance use disorder.28

Dementia

An RCT58 conducted in rural Guangdong with 86 participants with Alzheimer's Disease compared routine health education to a six-month internet-based ‘continuous nursing intervention’; it reported cognitive improvement in both groups, with greater improvement in the internet intervention group. A four-week controlled trial144 conducted in Hong Kong with a sample of 60 participants compared standard telehealth treatment for individuals with dementia and their caregivers to telehealth augmented with online video conferences; patients in the video conference group had less cognitive deterioration, and their caregivers had better physical and mental health.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Two studies with both urban and rural participants investigated the effect of internet-based mental health interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder, one RCT66 with 103 participants and one pre-post study135 with 146 participants. The RCT66 compared psychological symptoms and overall functioning among individuals on a waitlist to those who received a three-month web-based intervention; it reported improved depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and social functioning in the intervention group. The pre-post study reported improved PTSD and depressive symptoms after a three-month online intervention that included three modules: self-talk, relaxation, and professional help.

Other disorders

There were three disorders for which a single internet-based intervention was identified. An RCT21 conducted in Shanghai with 145 children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) compared a waitlist group to a six-month, non-pharmaceutical group intervention that included executive function training and an online parent training program; children in the intervention group had significantly improved attention, behavioural and emotional regulation, and cognitive functioning, but there was no significant improvement in the level of hyperactivity or impulsivity. An RCT in Hubei42 that followed 82 individuals with bipolar disorder for three months after hospital discharge found that follow-up based on a WeChat platform that facilitated patient interaction with clinicians significantly improved medication adherence compared to routine post-hospitalisation follow-up. A six-week controlled trial in Shanghai150 in 28 individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder compared in-person group CBT to iCBT; both groups showed improvements in obsessive-compulsive symptoms, the iCBT group also showed improvement in depressive symptoms, and the per-patient cost of the treatment was significantly less in the iCBT group.

Internet-based mental health-related interventions and surveys in non-clinical populations

Internet-based mental health applications have been employed in a variety of non-clinical populations as a screening tool, as a preventative intervention, and to provide education about mental health issues. The target groups for these types of interventions include the general population, individuals who may be at elevated risk of developing a mental disorder, and those who need basic information about mental health issues because they are caregivers or healthcare providers for individuals with mental disorders.

Adults, the elderly, and non-college youth in the general population

Fifteen internet-based studies in the general population included three focused on non-college youth,46,89,131 seven on adults,101,104,115,117,141,142,152 and five on older adults69,106,114,133,146 These studies included seven cross-sectional surveys,101,104,106,114,115,117,133 one longitudinal study,152 and seven intervention studies.46,69,89,131,141,142,146 Eight of the studies included both urban and rural participants.

The seven cross-sectional surveys included 45–15,000 (average 3015) participants. Three of the surveys reported elevated levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic.101,104,117 Another survey reported that eHealth literacy (i.e., the ability to evaluate and appropriately use health information from electronic sources) was associated with health-promoting lifestyles and better cognitive health in older adults.106 A national survey of 15,000 adult community residents during the COVID-19 epidemic reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression (11%), anxiety (7%), and PTSD (20%).115

The seven intervention studies included three RCTs,46,69,89 three controlled trials,141,142,146 and one pre-post study.131 These studies had an average of 215 (range, 62–617) participants, and the intervention continued for an average of 10·0 (range, 3–26) weeks. Three of the studies were conducted in both urban and rural communities. One study reported that compared with an educational brochure intervention, a six-week internet-based dissonance-based eating disorder prevention intervention significantly improved body dissatisfaction, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem in young women.46 Another study found that a nine-week online bodyweight high-intensity interval training (HIIT) intervention (with a waitlist as the control condition) significantly reduced anxiety and stress and improved global cognitive performance in young women.89 A study among female adults that compared the in-person and online administration of an eight-week ‘intuitive eating’ intervention (with weekly 20–40 min modules about eating-related attitudes)91 found that both groups reported significantly improved body image and reduced disordered eating behaviours, but there was no significant difference in the results of the in-person and online groups. Compared to a waitlist condition, a four-week self-help mindfulness intervention among adults in the general population was effective in reducing stress and stress-related psychological symptoms.142 Compared to routine in-person visits, augmenting in-person visits with a six-month smartphone-based video conferencing intervention significantly improved older individuals' feelings of loneliness, physical health, vitality, and pain; however, this intervention was not associated with a significant improvement in depressive symptoms.146

The longitudinal study152 assessed global cognitive functioning in 13,457 adults in the general population over four years. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, ownership of a desktop computer or cellphone was independently associated with less cognitive decline over time.

College students

Ten internet-based studies among college students include two surveys and eight intervention studies. The cross-sectional surveys assessed depressive and anxiety symptoms in 4882 medical students105 and perceived stress and social support in 1123 college students.120 The eight mental health interventions included six RCTs,22,26,35,54,63,74 one controlled trial,148 and one pre-post study.132 The sample size of the intervention studies ranged from 39 to 263 (average 108) individuals, and the length of the intervention ranged from 20 min to 16 weeks (average 7·9 weeks). Compared to a non-treatment control group, a sixteen-week internet-based group counselling intervention significantly reduced students' interpersonal sensitivity.148 Compared to a non-treatment control group, a one-month ‘Healthy Online Self-help’ intervention (provided either an interactive or non-interactive platform) effectively reduced the number of hours college students spent online each week and decreased their scores on a diagnostic screening instrument for mental health disorders.54 A 16-week study that augmented a college psychology course (the control condition) with internet-based psychological counselling (the intervention condition) reported significantly decreased depressive and anxiety symptoms and significantly improved quality of life in the intervention group.74 An eight-week pre-post study that assessed a digital mental health intervention based on the World Health Organization's ‘Step-by-Step’ guidelines reported that the intervention effectively reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and self-defined stress.132 However, another study about a one-month online self-directed counselling intervention for depressive symptoms reported limited effect.35

Healthcare providers

The eight internet-based studies among healthcare workers—all conducted in urban communities—included five cross-sectional surveys and three intervention studies. The surveys had sample sizes ranging from 345 to 3684 (average, 1336) individuals. Two of the surveys assessed anxiety and depressive symptoms during COVID-19,108,110 two assessed burnout (one pre-COVID103 and one post-COVID107), and one assessed PTSD symptoms during COVID-19.112 The survey about the occurrence of PTSD symptoms among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of adaptive coping skills and family support networks in combatting the negative mental health consequences of the pandemic on frontline healthcare workers.112 The single pre-COVID survey103 reported that healthcare workers who experience abuse or violence (from patients or their family members) are more likely to experience burnout.

The three intervention studies—which were all conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic—included two RCTs23,149 and one pre-post study.125 One RCT23 in 85 frontline nurses compared in-person training about basic psychological issues to a 10-day internet-based unstructured psychological counselling intervention; it reported that the online intervention could significantly reduce the stress and negative emotions experienced by the nurses. The other RCT149 in 60 medical staff compared a standard 15-day online psychological training package (the control group) to the standard online psychological training augmented with a ‘resourcefulness training’ component (the intervention group); it reported that participants in the intervention group had greater post-intervention improvements in their sense of resourcefulness, tenacity, and positive attitudes.

Pregnant and postnatal women

Six studies focused on pregnant and perinatal women, including two cross-sectional surveys conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic116,121 and four RCTs.41,50,57,85 Two of the studies included rural participants. An online survey among 19,515 pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic found high levels of self-reported depressive symptoms (45%), anxiety symptoms (29%), and suicidal ideation (7%).116 The four RCTs had samples ranging from 108 to 168 (average, 130) women, and the duration of the intervention was 1–7 (average, 3·7) months. Three of the RCTs compared standard prenatal and postnatal care to standard care augmented with internet-based applications that administer mindfulness training to pregnant and recently postnatal women41,57,86; all three studies reported significantly less depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms in the intervention group.

Caregivers of the seriously ill

Five studies about caregivers of persons with serious illnesses included one cross-sectional survey,119 and four intervention studies.20,123,124,129 The cross-sectional survey119 asked 449 family members of community-dwelling individuals with serious mental disorders from rural communities about their preference for WeChat-based versus in-person psychoeducation, peer support, and professional support. The results showed that 23% did not want either type of support, 45% reported acceptance of both types of support, 27% preferred in-person support, and only 5% preferred WeChat-based support.

The four intervention studies included one RCT20 and three pre-post studies.119,123,124,129 The RCT20 compared routine education for family members of critically ill individuals in a hospital intensive care unit to routine education augmented by an interactive mobile phone education-related application; the mobile phone application significantly reduced family members' anxiety, though it did not increase their level of satisfaction with the information they received about their ill family member's condition. Two pre-post studies assessed the effects of providing internet-based services to the caregivers of individuals with dementia—a nine-week iCBT129 intervention and a six-month telecare medical support system123—both studies reported that caregivers experienced fewer upsetting thoughts and less emotional turmoil. However, another pre-post-trial of a four-week intervention using an online education application for 254 caregivers of individuals with eating disorders conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found no significant improvement in the level of these caregivers' symptoms of depression and anxiety.124

Parents

Three internet-based interventions, all of which were RCTs, focused on parents. One study19 compared 196 parents of healthy children on a waitlist to 187 who received a three-week self-help online mindfulness intervention; parents in the intervention group reported significantly fewer anxiety symptoms and greater subjective well-being. Another RCT70 in 67 families aimed at reducing children's psychosocial problems by providing parent-child pairs with an eight-week program of mobile phone-administered parent-child exercises and games using the ‘Family Move’ internet application; one month and six months after the intervention, parents in the intervention group reported that their children had improved levels of physical activity and psychosocial well-being. The third RCT79 in 150 parents of premature infants compared the effectiveness of traditional outpatient follow-up after hospital discharge at reducing parental anxiety and depression to WeChat-based follow-up and management after discharge; the WeChat-based remote follow-up was significantly better than conventional follow-up.

Internet-based surveys and interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic

Nineteen (19·8%) of the 96 identified studies published between 2020 and 2022 were explicitly focused on assessing or reducing the mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. These studies included ten cross-sectional surveys101,104,107,108,110,112,115, 116, 117,121 and nine intervention studies.22,23,56,68,94,124,125,130,149 Four of these studies included rural participants. Three of the studies (all RCTs) were in clinical populations with mild to moderate anxiety and depressive symptoms56,68,94; the remaining 16 studies were in non-clinical samples.

The average sample size of the surveys was 4317 (range 345–19,515) individuals. Four surveys were conducted in the general population,101,104,115,117 four were among health professionals,107,108,110,112 and two were among pregnant women.116,121 These studies all assessed depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, other negative affective states, and the factors that were associated with these negative emotional states during COVID-19. One study in the general population (n = 917) found that viewing stressful content on social media networks (versus traditional media) was significantly associated with more pronounced depression, anxiety, and stress.101 A national study (n = 15,000)115 reported that individuals with higher levels of eHealth literacy (i.e., the ability to use health information from electronic sources appropriately) had less serious depressive symptoms, insomnia, and PTSD symptoms. The studies among healthcare workers focused on elevated levels of stress, psychological symptoms, PTSD, and burnout; they found that providing healthcare workers psychological support, helping them maintain adaptive coping strategies, and encouraging them to mobilise family support networks were the most effective methods for reducing the adverse psychological effects of the pandemic.110,112 A study about the severity of depressive symptoms among 1266 pregnant women during the COVID-19 lockdown policy in Wuhan (capital city of Hubei Province) and Lanzhou (capital city of Gansu Province) found that frequent use of the internet was associated with more severe symptoms and good family support was associated with less severe symptoms.121

The intervention studies included five RCTs,22,23,56,68,94 three pre-post studies,124,125,130 and one controlled trial.149 Five of these nine intervention studies focused on methods for reducing stress and associated psychological symptoms in frontline nurses and other healthcare workers.22,23,94,125,149 The assessed online interventions included mindfulness training,22 unstructured psychological counselling,23 resourcefulness training,149 iCBT,94 and a tailored three-stage psychological training package.125 One two-month RCT among 114 young adults under COVID-19 quarantine compared mindfulness-based versus social-support-based mobile health (mHealth) interventions and found that the mindfulness mHealth intervention was more effective at reducing participants' level of anxiety.56

Discussion

Over the last decade, China has experienced a rapid increase in the use of the internet as a medium to transmit information about mental health, screen community members for mental disorders, provide stand-alone mental health interventions, and augment conventional (i.e., in-person) mental health care. This explosive expansion has been driven by 1) advances in the availability of broadband services, 2) increased use of the internet, smartphones, and social networking platforms by community members, 3) growing awareness of the importance of psychological well-being and mental health to overall health, and 4) active government support for the use of the internet to expand access to health services. However, in the absence of standardised methods and relevant regulations, many insufficiently tested mental health-related internet services have emerged, some based on Western models and others home-grown. Most internet-based surveys are single-wave, cross-sectional studies that enrol convenience samples, so they cannot be used to help develop mental health policies or programs. Most intervention studies—regardless of format, duration, or intensity—report significant improvement in symptoms, but the poor methodological quality of the studies and the lack of post-intervention follow-up assessments make it impossible to be confident about the effectiveness and potential long-term utility of these interventions. Overall, mental health-related internet-based services in China are still in the early phase of their development; additional work will be needed before they can mature into a core component of China's overall mental health care delivery system.

Summary of evidence

This scoping review of research about internet-based mental health interventions and surveys in China from 2000 to 2020 identified 143 studies, 54 published in Chinese and 89 in English. Only three of the studies were published before 2011; the number of studies gradually increased from 2011 until 2019 and then rapidly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (in 2020–2022)—presumably due to concern about the psychological effects of the pandemic and the restricted access to traditional mental health services during the pandemic. Most identified studies were conducted in urban communities in economically developed parts of the country; only four of the studies were located in rural communities. Study participants were individuals with specific mental disorders in 89 (62·2%) studies and different cohorts of healthy community members in 51 (35·7%) studies.

The 143 studies include 87 RCT intervention studies (66 in individuals with mental disorders and 21 in community-based cohorts), 29 intervention studies using non-random designs (16 among patients and 13 in community cohorts), 21 cross-sectional surveys (4 in patients and 17 in community cohorts), and six other types of studies (one cohort study, two longitudinal studies, two non-intervention randomised crossover studies, and one cross-sectional study that evaluated mental health internet applications). The intervention studies for individuals with mental disorders were either adjunctive internet-based interventions aimed at improving the outcome of traditional in-person mental health services (primarily focused on individuals with more serious disorders who needed medication or other in-person services) or ‘stand-alone’ self-directed or clinician-supported internet interventions (primarily focused on community residents with less serious conditions).

Most of the 24 intervention studies in individuals with schizophrenia were initiated during post-hospitalisation follow-up; they included eight studies that used the internet to replace some of the traditional in-person follow-up visits; eight studies that provided educational materials about medication usage, rehabilitation, and self-management; four studies that provided regular text messages to encourage medication adherence; and four studies that provided on-demand online consultation with mental health professionals. Two of these studies were conducted among rural residents with limited access to mental health services; the internet interventions described in these rural studies (a mobile texting app in rural Guangdong,13 and an internet-based training app in rural Hunan77) did not entirely replace the need for in-person services, but they did improve the medication adherence among participating individuals with schizophrenia who had minimal in-person contact with psychiatrists or other mental health personnel.

Internet-based intervention studies for individuals with depression, insomnia, anxiety disorders, and other mental health disorders included different combinations of stand-alone internet interventions, internet interventions used to replace traditional in-person follow-up services, and internet interventions aimed at augmenting traditional in-person services (by providing educational or training apps about self-management, activities of daily living, and psychological resilience).

The most frequently reported stand-alone internet-based intervention for individuals with mental disorders was internet-administered cognitive behaviour therapy (iCBT). The 22 studies using iCBT included 16 of the 87 RCT intervention studies and 6 of the 29 non-RCT intervention studies among individuals with mental disorders. It was used in 9 of the 11 intervention studies about insomnia, 5 of the 7 intervention studies about anxiety, and 3 of the 13 intervention studies about depression. The course of iCBT treatment lasted from one to six months. Among the 17 iCBT intervention studies with control groups, self-guided iCBT was compared to treatment as usual (TAU) in seven studies, therapist-guided iCBT in four studies, in-person CBT in three studies, in-person group CBT in two studies, and group iCBT in one study. The remaining 5 iCBT studies include 3 pre-post studies without a control group, and two studies that provided no treatment to the control group. All 22 studies reported symptomatic improvement in the iCBT groups, but the results for some of the controlled iCBT studies did not indicate whether the improvement in the iCBT group was significantly greater than that in the control group. The content of these iCBT interventions was similar, but different treatment durations, enrolment criteria, and outcome measures made it impossible to combine the results in a meta-analysis.

Among the 34 internet-based intervention studies for different cohorts of healthy community members (21 RCTs, 8 pre-post studies, and 5 controlled trials), eight interventions were in college students, seven in the general population, five in perinatal mothers, four in caregivers of individuals with serious illnesses, three in frontline healthcare personnel during COVID-19, three in parents, and four in other types of community members. The duration of these interventions ranged from a 20-min online video aimed at reducing mental health stigma in college students26 to a one-year depression prevention program in adolescents considered at risk for developing a depressive disorder.34 Most of these internet-based interventions were self-directed, but some were guided by or had supplementary counselling support from mental health providers. Most of the interventions aimed to reduce participants' feelings of depression, anxiety, or overall stress by administering online applications that trained respondents in mindfulness, CBT, or resilience at times of emotional crisis. Other types of objectives reported for some of the studies included reducing problematic eating behaviours46,141 or encouraging vigorous physical activity among women,46,89,141 reducing weekly online hours among college students,54 promoting mental health literacy in youth,131 or providing caregivers education about how to manage their family member's illness.24,79,123 Among the 26 intervention studies with control groups, the intervention groups were compared to persons who did not receive any intervention in 12 studies, persons who received traditional support services in 5 studies, persons who received in-person support services in 3 studies, persons who received non-specific health education in 3 studies, and persons who received other types of interventions in 3 studies. Five controlled intervention studies reported no significant differences between the intervention and control groups.20,35,45,124,146 The remaining 21 studies reported achieving the study objectives; however, the reports for some of the controlled studies did not indicate whether the improvement in the intervention group was significantly greater than that in the control group. Only four of the studies reassessed participants at some time after the completion of the intervention,26,69,70,149 so it is uncertain whether the reported positive outcomes persisted after the completion of the intervention.

The three online cross-sectional surveys among individuals with mental disorders include a study that compared the demographic and clinical characteristics and attitudes about using WeChat-based mental health services of community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia who did and did not use the internet,118 a study involving the online assessment of temporal processing competence in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),100 and a study that assessed the prevalence and severity of symptoms in children for autism spectrum disorder.109 The 19 online cross-sectional surveys in non-clinical community cohorts included seven studies in the general population, five in healthcare workers, two in college students, two in pregnant women, and three in other types of respondents. The seven studies in the general population included four studies about the prevalence of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during the COVID-19 pandemic,101,104,115,117 and three studies among older adult community members about anxiety and depression,114 eHealth literacy,106 and cognitive functioning.113 Four of the five cross-sectional surveys of healthcare workers assessed burnout and the prevalence of psychological symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD among frontline workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.107,108,110,112 Other cross-sectional surveys include two studies that assessed anxiety and depressive symptoms among pregnant women during COVID-19,116,121 a study about the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in college students,105 and a survey that identified factors associated with mobile phone addiction in college students.120 All of these cross-sectional studies used samples of convenience, and they were only conducted at a single point in time, so it is not possible to assess the representativeness of the results or the extent to which the reported prevalence for the different disorders or their relationship to potential predictive factors change over time.

Limitations of this review and the available research

The current review has two potential limitations. 1) After screening the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the 19,127 unique papers identified in the electronic search of five English-language and five Chinese-language databases, 143 eligible papers were included in the review. When screening these papers, we used a rigorous operational definition of ‘internet-based activities related to mental health’, but it is possible that some activities on the borderlines between telephone-based and internet-based activities and between internet-based and AI-based activities were excluded. 2) We choose to analyse results based on the target group and type of study (intervention vs. non-intervention). Analyses based on other dimensions (e.g., comparing hybrid v ‘pure’ internet interventions and surveys, or grouping studies based on the goal of the study -- education about mental health/illness, counselling, monitoring, early identification, clinical follow-up, etc.) may have arrived at different conclusions.

The main limitations of the identified research about internet-based mental health research in China include 1) the lack of studies in low-resourced locations where internet services could be of most benefit, 2) the limited range of mental health disorders considered in the intervention studies, 3) the low methodological quality of the intervention studies, 4) the lack of long-term follow-up assessments to determine if the reported beneficial effects of the interventions have any lasting effect, 5) the lack of evaluation of the potential negative consequences of using of the internet to provide mental health services, and 6) the use of single-wave cross-sectional studies that, unlike multi-wave studies, are unable to assess changes over time (or following specific policy interventions) in the prevalence of disorders, the level of mental health literacy, or attitudes about mental health and mental health services.

China also lacks research about the process of developing, standardising, and monitoring internet-based mental health services. These types of ‘meta’ studies about internet services are needed to inform the creation of the legal, professional, and financial infrastructure that will be required before internet-based services can achieve the goal of becoming an integral component of the overall mental health care system. This includes studies about 1) ensuring the confidentiality of user's personal information, 2) improving awareness of and acceptability of internet-based services to community members, mental health patients and their family members, and mental health care providers, 3) standardising methods for providing internet-based educational, screening, and disorder-specific services, 4) assessing the relative cost-effectiveness of in-person, internet-based, and combined in-person with adjunctive internet-based services for different disorders, 5) comparing alternative mechanisms for funding different types of internet-based services (self-pay, government insurance, line-items in departmental budgets, or other), 6) developing licensure requirements for internet providers of mental health services, 7) training mental health providers in the optimal methods for using the internet either as a stand-alone treatment or as an augmented treatment to standard mental health care, and 8) monitoring the outcomes of national and provincial policies, regulations, and programs aimed at promoting the use of the internet to improve community psychological wellbeing and mental health.

Conclusions

In conclusion, although a few published studies have found internet-based interventions in China beneficial for individuals with some mental illnesses, given the serious methodological problems of most of these studies, the lack of comparability between the available studies, and the sparse literature about internet-based interventions for most common mental disorders, it is too early to recommend the widespread use of these methods in China. It is also impossible to assess the practical value of internet-based surveys about mental health issues; they are rarely based on representative samples, are almost all one-time, cross-sectional studies, and are never used to inform programs or policies. This scoping review identified three major problems in the current literature: 1) those who could potentially benefit the most—the rural population—have not been studied, 2) there are no standardised online applications that healthcare professionals can use to identify individuals at high risk of mental disorders, and 3) no criteria or regulations have been developed by academic institutions or mental health associations that could be used to standardise the implementation, oversight, and evaluation of internet-based mental health care interventions. These issues must be resolved before it will be possible to make a realistic assessment of the potential contribution of internet-based surveys and interventions to China's overall mental health enterprise.

Recommendations

There are four main ways internet-based services could help improve and sustain the mental health of China's population. However, the currently available research about internet-based mental health activities in China is generally of poor quality and limited in scope, so it remains unclear what activities are beneficial and, importantly, how to up-scale effective services and integrate them with the traditional mental health service network. Several changes in the development, evaluation, and promulgation of internet-based mental health services are needed.

-

1)

Internet-based surveys of the mental health status, level of mental health literacy, and attitudes about mental health issues and services in the total population and specific cohorts within the population. To realise the potential benefits of such surveys, several changes in the current method of conducting surveys in China will be needed. 1) The samples included in the surveys must represent the target population of interest. 2) The psychometric properties of the internet-administered Chinese versions of the instruments used to assess psychological symptoms, knowledge, or attitudes need to be rigorously assessed. 3) The surveys must be repeated periodically (at least every five years) to monitor changes over time. And 4) (in internet surveys that screen for mental disorders) there need to be sufficient clinical services available to provide services to individuals the surveys identify as being at high risk of a serious mental disorder (or suicide) and a precise mechanism for survey respondents to access these services.

-

2.

Internet-based treatment services for less serious mental disorders (i.e., those that can be effectively treated without medication). The current human resources available in China to diagnose and treat mental disorders are unable to meet the identified need for such services. Moreover, many individuals with relatively minor mental disorders (e.g., non-psychotic depressive or anxiety disorders, insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, etc.) either do not recognise that they suffer from a treatable disorder or are unwilling to consider treatment from mental health services (which can be due to cost, inconvenience, or mental illness-related stigma). Internet-based treatment options that rigorously protect participants' privacy, such as internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy, could help fill this gap. However, presently, the enrolment criteria, specific procedures, frequency, duration, and evaluation criteria for these interventions in China vary widely. There is no clear rationale for the chosen format: the interventions can be provided to individuals or groups, can last from a few days to several months, have varying levels of involvement of mental health professionals, and can be free of charge or require payment (which is typically not covered by current health insurance policies). Moreover, the quality of the RCTs that assess the effectiveness of these interventions in China is poor, and, importantly, the available studies rarely assess the long-term effectiveness of the interventions, so the overall benefit of these internet-based services is unknown. Several changes are needed. 1) Researchers in China must develop a relatively small set of standardised internet-based interventions for each type of condition. 2) These interventions' long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness should be compared, and the best options should be promoted nationally. 3) Internet-based screening procedures that identify individuals most likely to benefit from each type of intervention need to be developed and implemented. 4) Professional mental health organisations should help develop and promote national and provincial-level regulations that monitor the internet to ensure that the mental health services available online are effective and are provided by qualified organisations or individuals.

-

3.

Augmenting traditional psychiatric services for persons with serious mental illnesses by using the internet to monitor symptoms, promote adherence to medication recommendations, provide targeted information about the patient's illness, and administer ancillary treatments (e.g., to reduce depression, improve life skills, etc.). The challenge in providing these ‘add-on’ services is that they must be individualised to the needs of each patient and may need to change over time as the patient's condition changes. For example, in some cases, a short-term internet-based intervention is sufficient, whereas in other cases, the internet service needs to be ongoing. The current research about internet-based augmentation of traditional mental health services in China is piecemeal, so it is impossible to come to a definitive conclusion about the utility of internet-based augmented services. Three things need to happen. 1) Research is needed to develop a battery of evidence-based augmented services for each of the major mental disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism, etc.). 2) Once effective internet-based augmented services are available, it will be necessary to conduct rigorous studies of the cost-effectiveness of these services. 3) Finally, other research will be needed to determine how best to train current (and future) mental health providers how to flexibly use these augmented services to best meet the changing needs of their patients.

-

4)