ABSTRACT

The locus coeruleus–norepinephrine (LC‐NE) system is involved in mediating a wide array of functions, including attention, arousal, cognition, and stress response. Dysregulation of the LC‐NE system is strongly linked with several stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders, highlighting the LC's pivotal role in the development of these disorders. Located in the dorsal pontine tegmental area, the LC contains noradrenergic neurons that serve as the main source of NE in the central nervous system. Activation of the LC and subsequent release of NE at different levels of the neuroaxis is adaptive, allowing the body to adjust appropriately amid a challenging stimulus. However, prolonged and repeated LC activation leads to maladaptive responses that implicate LC‐NE dysfunction in stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders. As the primary initiator of the stress response, corticotropin‐releasing factor (CRF) activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Following the discovery of CRF more than four decades ago, numerous studies established that CRF also acts as a neurotransmitter that governs the activity of other neurotransmitters in the brain neurotransmitter system. The LC‐NE system receives abundant CRF afferents arising from several brain nuclei. CRF afferents to LC‐NE are activated and recruited in the pathogenesis of stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders. Presented in this review are the CRF neuroanatomical connectivity and physiological characteristics that modulate LC‐NE function, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders. Additionally, this review illustrates the contribution of LC‐NE to the apparent sex‐dependent differences in stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders. Hence, the LC‐NE system is a promising target for the development of therapeutic strategies for stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords: corticotropin releasing factor, locus coeruleus, norepinephrine, sex differences, stress, stress response

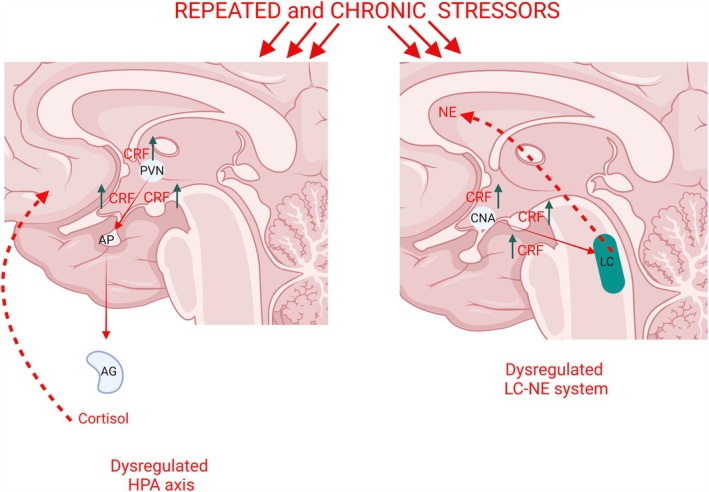

Repeated and chronic exposure to stressors may activate the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine (LC‐NE) system. Depression and post‐traumatic stress disorders precipitated by a stressful event are associated with the hypersecretion of the corticotropin‐releasing factor (CRF) leading to elevated CRF levels in the brain (green arrows pointed up). CRF hypersecretion in the CNA increases CRF release in the LC‐NE that leads to the dysregulation of the LC‐NE system (dotted red lines) and consequently stress‐related psychiatric disorders.

Abbreviations

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropic hormone

- ad

Alzheimer's disease

- AUD

alcohol use disorder

- BNST

bed nucleus of stria terminalis

- CN

central nucleus of the amygdala

- CRF

corticotropin‐releasing factor

- CRFr

CRF type 1 receptor

- CRFr2

CRF type 2 receptor

- DBH

dopamine beta hydroxylase

- DSM‐5

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition

- DR

dorsal raphe nucleus

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- Gai‐coupled; hM4Di DREADD

inhibitory designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drugs

- HPA

hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

- LC

locus coeruleus

- LC‐NE

locus coeruleus‐norepinephrine

- LL

long latency

- NIAAA

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

- NE

norepinephrine

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PTSD

post‐traumatic stress disorders

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus

- single‐nucleus RNA‐Seq

single‐nucleus ribonucleic‐acid sequencing

- SL

short latency

- SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- 5‐HT

serotonin

1. Introduction

Stress is recognized as a paramount risk factor for various neuropsychiatric disorders. Stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders—including anxiety disorders, depression, and post‐traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) and substance use disorders—pose a significant global burden to public health (US Burden of Disease Collaborators 2018) and cost the economy trillions of dollars annually (Trautmann et al. 2016). In the United States, these disorders are the leading contributor to years lost to disability, surpassing cardiovascular disease or cancer (Kamal et al. 2017). Stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders are associated with severe anguish and impaired behavioral function in affected individuals, resulting in negative societal impacts. These impacts are not limited to those affected directly by the disorders but also extend to their families and those within their social and work microcosm (Patel et al. 2016). Stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders do not occur in isolation but demonstrate a strong pattern of comorbidity (Barr et al. 2022). Consistently, clinical studies show that the most common configurations of overlap include mood, anxiety and substance use disorders (Barr et al. 2022). It is expected that the long‐term impact to global economic burden of these disorders will continue to increase, given the projections of demographic changes and increased life expectancy (Patel et al. 2016).

Following exposure to a stressor, whether either acute or chronic, one of the first systems that stress targets is a tiny, bilateral nucleus located in the dorsal pontine tegmental area in the brainstem known as the locus coeruleus (LC). The LC contains a cluster of noradrenergic neurons that have widespread projections throughout the entire neuroaxis. The release of neurotransmitter norepinephrine (NE) is critically involved in modulating a multitude of functions ascribed to LC‐NE system, including attention (Aston‐Jones et al. 1999), arousal (Breton‐Provencher and Sur 2019), cognition (Sara 2009), and stress response (Valentino and Van Bockstaele 2008). Given the widespread projections of noradrenergic LC, the release of NE not only affects the cellular and molecular properties of the target neurons but affects the efficacy of synaptic transmission throughout the nervous system. When the release of NE from the LC is dysregulated, then these neuronal and synaptic properties may be impaired throughout the nervous system as well. Thus, the modulation of LC‐NE system is a critical component of the neuronal machinery underlying adaptation to stress, and if stress exposure continues in a repeated and chronic fashion, then dysregulation of the LC‐NE system may result and subsequently contribute to the pathophysiology underlying neuropsychiatric disorders. Indeed, it is recognized that repeated and chronic stress exposure is linked with the emergence and severity of stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders (Zorn et al. 2017). Therefore, understanding how the LC‐NE system responds to stress is crucial in understanding the pathogenesis of stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders. Albeit dearth of comprehensive understanding regarding the underlying physiological processes of this pathophysiology, studies show that stress induces clear effects on the structure and function of the brain (McEwen 2006). Investigating the mechanisms by which the mediators underlying stress response intersect with the neural substrates involved in the disorders may unravel the link between LC, stress and stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders.

A large number of investigations have been conducted since the discovery of the LC nearly 250 years ago to characterize its role in human physiology and behavior. Indeed, there is extensive literature on the role of the LC‐NE system in stress‐related psychiatric disorders. However, this field is ever‐expanding, in depth and breadth, and this review aims to integrate the existing knowledge of the LC with new knowledge generated by scientific advances and modern techniques, including single‐nucleus ribonucleic‐acid sequencing (RNA‐Seq), optogenetics, chemogenetics, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), in order to provide deeper insights into the role that the LC‐NE plays in the development of stress‐related psychiatric disorders. This review will also incorporate the recent characterization of the emerging roles of the LC‐NE in stress resiliency and its involvement in Alzheimer's disease (ad), as well as the impact of sex differences on the LC physiology and downstream behavior. Additionally, the review discusses therapeutic implications, emphasizing the potential of targeting the LC‐NE system for treating stress‐related psychiatric disorders.

2. The Discovery of LC and Neuroanatomy

Human brains are constantly processing a wide array of environmental stimuli. Some of this information is perceived as ambient and inert, while others elicit attention and may be perceived as threatening, known as stressors. The LC responds to any of these stimuli. The research interest in LC emerged in the late 17th century with Felix Vicq d'Azyr's discovery of the LC (Tubbs et al. 2011). Other sources consider Johann Christian Reil as the first to describe LC (Reil 1809). The discovery of the LC quickly paved the way to an immense research interest in investigating the anatomy of the LC. The LC is situated near the wall of the fourth ventricle, medial to the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus and the superior vestibular nucleus (Russell 1955; Swanson 1976). Bilaterally, the LC comprised approximately 20,000–33,000 neurons in humans (Wagner‐Altendorf et al. 2019) and approximately 3100–3400 in rats (Swanson 1976). Among the laboratory experimental animals, extensive and comprehensive studies of LC have utilized rats. An analysis of publications available on Pubmed (Pubmed accessed on January 27, 2024) containing the keywords “locus coeruleus” and “rats, monkey, mice, cats, rabbits, birds, guinea pigs, chickens, dogs, frogs, opossums or drosophila/fruitfly” demonstrated that there has been extensive research and comparative anatomy of the LC across species, with the following number of publications (by species): 5410 articles in rats, 2268 in monkeys, 1192 in mice, 526 in cats, 149 in rabbits, 113 in birds, 62 in guinea pigs, 36 in chickens, 31 in dogs, 27 in frogs, 12 in opossums, and 2 in drosophila/fruitfly.

The borders of the LC were first demonstrated in 1955 using the Nissl staining (Russell 1955). Further characterization of the LC cytoarchitecture and type of cells the LC exhibits was later described utilizing Golgi staining (Swanson 1976). The discovery of formaldehyde by Ferdinand Blum in 1893 revolutionized the methods for localization of proteins/enzymes in tissues using immunohistochemistry, given that formaldehyde is a fixative that does not denature proteins in tissues.

One of the earliest and most consequential neuroanatomical findings was that LC neurons contain the largest cluster of noradrenergic neurons (Dahlstrom and Fuxe 1964). However, the use of formaldehyde in immunohistochemical fluorescence to label specific enzymes in neurons, including the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of dopamine to NE called dopamine beta hydroxylase (DBH), allowed for the very first localization of DBH expression in the LC (Goldstein et al. 1971) demonstrating that the LC is the neuroanatomical site of NE synthesis in the brain.

The cellular distribution of DBH in LC was subsequently followed by investigation of the LC at the ultrastructural level. In 1964, the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) was discovered at the National Institutes of Health (Nagatsu and Nagatsu 2016). TH is responsible for catalyzing the conversion of amino acid L‐tyrosine to L‐3,4‐dihydroxyphenylalanine, the first and rate‐limiting step in the biosynthesis of catecholamines, including dopamine, NE, and epinephrine. Utilizing TH as a marker for LC neurons, the first high‐resolution subcellular investigation was first conducted by Pickel and colleagues in 1975 (Pickel et al. 1975). These studies demonstrated that TH could be visualized as an electron dense product labeled with peroxidase‐antiperoxidase immunohistochemical technique and therefore characterized the subcellular distribution of TH in the perikarya and neuronal processes including dendrites and axons in LC neurons (Pickel et al. 1975). Although TH localization was both evident in longitudinal and cross sections of LC neurons, the peroxidase‐antiperoxidase technique utilized in these first ultrastructural investigations was not able to provide optimum resolution to distinguish between the TH distribution on the surface and matrix of tubular structures identified (Pickel et al. 1975). However, the immunogold labeling technique introduced in 1971 (Faulk and Taylor 1971) allowed visualization of localization not only of enzymes (i.e., DBH or TH) as markers for noradrenergic neurons in specific parts of perikarya and neuronal processes in the LC but also other proteins, including receptors, neuropeptides, and neurotransmitters (Van Bockstaele et al. 1996; Reyes et al. 2011). Thus, extensive evidence has elucidated interactions of neuromodulators, neuropeptides, and the LC‐NE that illuminate the diverse functions attributed to the LC‐NE system.

The emergence of the single‐nucleus RNA‐Seq has accelerated our understanding of the LC‐neuronal subtypes and their roles in the stress response (Caramia et al. 2023; Mukai et al. 2023). Through single‐nucleus RNA‐Seq, it is now possible to identify a myriad of substances, neuropeptides, and neuropeptide receptors expressed in LC‐NE (Caramia et al. 2023; Mukai et al. 2023). For example, single‐nucleus RNA‐Seq revealed that LC‐NE neurons expressed neuropeptides, co‐transmitters, and receptors, and a number of which are involved in stress response (Caramia et al. 2023; Mukai et al. 2023).

3. Activation of LC Neurons

In the presence of various environmental stressors, the LC‐NE neurons are activated and produce distinct modes of firing patterns, namely, tonic and phasic activity. These firing patterns create distinct functional outcomes. Electrophysiological studies using single and multiple extracellular recordings in both anesthetized (Carter et al. 2010) and unanesthetized and freely moving, behaviorally responsive (Foote et al. 1980; Aston‐Jones and Bloom 1981; Abercrombie and Jacobs 1987) rats, mice, cats, and monkeys have identified and characterized LC's firing patterns (Foote et al. 1980; Aston‐Jones and Bloom 1981; Abercrombie and Jacobs 1987; Carter et al. 2010). In fact, LC neurons exhibit phasic and tonic modes of output, which differ in both the pattern of spike discharge and NE release properties (Florin‐Lechner et al. 1996).

The tonic spontaneous LC discharges are correlated with wakefulness while LC firing occurs. The LC firing declines during non‐rapid eye movement sleep and rapid eye movement sleep is noiseless or devoid of firing (Aston‐Jones and Bloom 1981; Rasmussen and Jacobs 1986; Carter et al. 2010). A decrease in LC tonic firing is linked with hypoarousal and attention deficits (Howells et al. 2012). In the absence of a stressor or a threat, the tonic LC activity sustains vigilance and attention (David Johnson 2003). Exposure to stressful events and stimuli heightens LC tonic discharge into a high tonic firing. Thus, the LC‐NE neurons robustly increase tonic firing discharge in response to stress (Curtis et al. 1997; Curtis et al. 1999; Valentino and Van Bockstaele 2008). High tonic LC firing is associated with scanning or labile attention, behavioral flexibility, and diminishing focus, while phasic LC firing is associated with focused attention (Aston‐Jones et al. 1999). Phasic LC discharges, characterized by short excitatory burst occur in response to a variety of salient stimuli (Foote et al. 1980; Aston‐Jones and Bloom 1981). The LC neurons shift between tonic and phasic LC firing in order to adapt to changing attentional imperatives. Accordingly, tonic LC firing promotes scanning of the environment, while phasic LC firing promotes focusing on environmental cue or stimulus.

Combining in vivo chemogenetics, optogenetics, and retrograde tracing showed the engagement of LC tonic activity following stress exposure (McCall et al. 2015). In this report, chemogenetic studies selectively targeted an inhibitory designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drugs (Gαi‐coupled; hM4Di DREADD to LC‐NE neuron) by injecting a Cre‐dependent AAV into the LC of TH‐IRES‐Cre‐mice. Chemogenetic activation revealed that manifestation of the anxiety phenotype is precluded following selective inhibition of LC‐NE during stress (McCall et al. 2015). Optogenetic manipulation of LC‐NE neurons showed that this technique can be utilized to sustain the tonic LC‐NE firing mimicking the response to stress. These findings suggest that alterations in LC firing patterns may play a pivotal role in stress‐induced anxiety and may in part participate in the development of stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders.

LC activity is stimulated by a variety of stimuli, including non‐noxious, noxious, appetitive, aversive, or novel (Aston‐Jones and Bloom 1981; Abercrombie and Jacobs 1987), or stimuli that necessitate a response (Rajkowski et al. 2004). If the animal is exposed to a stimulus that is not aversive nor noxious, responses have been shown to acclimatize over time (Herve‐Minvielle and Sara 1995). Together, these studies suggest that the activation of LC neurons may reflect a unique function of identifying a threat component in a given stimulus and therefore recognizing such stimulus as a stressor.

Indeed, methodological advances in recent years, including optogenetics, chemogenetics, viral tract tracing, and encoded calcium indicators have been utilized to monitor the LC‐NE activity (McCall et al. 2015; Antila et al. 2022). For example, calcium indicators introduced in LC‐NE neurons showed an increase in calcium transients indicative of poor sleep quality (Antila et al. 2022). Imaging advances, including positron emission tomography (PET) and fMRI, have expanded our understanding of LC function. For instance, the utilization of PET scans has allowed measurement of catecholamine synthesis in the LC, while fMRI has been used to characterize the effect of LC neurochemical function on LC network activity (Chen et al. 2023; Parent et al. 2024).

Given that the LC has afferent neurons, particularly CRF (Valentino et al. 1992; Valentino et al. 1994; Van Bockstaele et al. 1996, 1998; Van Bockstaele et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2011; Reyes et al. 2019), that influence its role in the development stress‐related psychiatric disorders, using fear‐induced bradycardia as a tool (Battaglia et al. 2024) combined with neuroanatomical and functional approaches can be helpful in investigating the role of LC in integrating cognitive, emotional and autonomic responses during chronic stress exposure that could possibly lead to stress‐related psychiatric disorders. For instance, in response to a threatening stimulus, fear‐induced bradycardia may emerge as a component of a generalized state of freezing (Hamm 2020). In fact, an association between fear‐induced bradycardia and freezing has been demonstrated in rats (Walker and Carrive 2003). Using the same paradigm, with fear‐induced bradycardia as a technique, the CRF afferents that activate LC may elicit deceleration of heart beats as a response to negative outcomes, which has been shown in several studies (Battaglia et al. 2024).

4. Afferent Inputs to LC

A variety of techniques have investigated the afferents derived from several nuclei that regulate the activity of LC neurons. The LC afferents are important, as they are not only functionally distinct but also chemically distinct that carry information to LC. Understanding the LC afferents is vital to understanding the complexity of functions ascribed to the LC, particularly in the stress response and the development of stress‐related psychiatric disorders.

4.1. Corticotropin‐Releasing Factor Afferents of LC

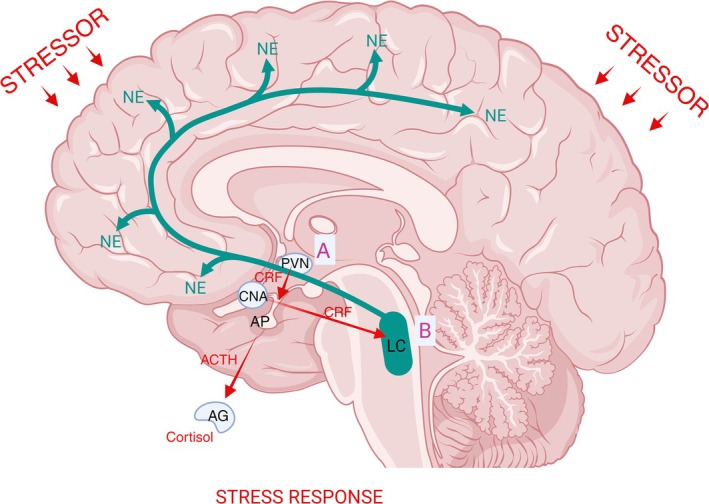

Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRF) is a 41‐amino acid neuropeptide, discovered in 1981 (Vale et al. 1981), which functions to orchestrate the endocrine, physiological, and behavioral limbs of the stress response. Abundantly distributed in the hypothalamus (Swanson et al. 1983), CRF in the hypothalamus modulates the release of pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in response to stress (Figure 1). CRF is also enriched in extrahypothalamic areas in the brain (Swanson et al. 1983) and is deeply involved in stress response. A number of stressors that stimulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis also activate the LC‐NE system (Figure 1), suggesting that the two stress systems are engaged in parallel by the same stressors or that the activation of one system consequently activates the other system. However, this review focuses on the role CRF afferents in the LC‐NE system that activate the LC's activity in the presence of a stressor.

FIGURE 1.

Exposure to stressors (red small arrows) activates the hypothalamic–pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and the locus coeruleus‐norepinephrine (LC‐NE) system. (A) Corticotropin‐releasing factor (CRF) is abundant in the hypothalamus, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) in particular. CRF is releaseld from the PVN via the hypophysial portal system that signals the anterior pituitary (AP) gland to release the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the systemic circulation. In turn the ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex (AG) to release glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rodents) that then modulates physiological and behavioral response. (B) CRF is abundant in the extrahypothalamic areas such as the central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA). Stress exposure increases CRF release (red arrow from the CNA) in the LC‐NE system that in turn increases LC tonic discharges and NE release (green arrows).

Combining retrograde and anterograde tracing has illustrated that the LC receives CRF afferents from various nuclei (Valentino et al. 1992; Valentino et al. 1994; Van Bockstaele et al. 1996, 1998; Van Bockstaele et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2011; Reyes et al. 2019). Through high resolution electron microscopy, it has been shown that the CRF afferents to the LC form synaptic association with noradrenergic LC dendrites (Van Bockstaele et al. 1996, 1998; Van Bockstaele et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2011). Injection of a retrograde tracer (wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and coupled to gold or fluorogold) into the LC region where the density of CRF‐immunoreactive fibers is concentrated yielded numerous retrogradely labeled CRF neurons in the central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA) (Van Bockstaele et al. 1998; Reyes et al. 2019). To confirm that the CRF afferents arising from the CNA project to LC, an anterograde tracer (biotinylated dextran amine) was injected into the CNA and yielded dense CRF‐labeled axon terminals in the LC that form synaptic specialization with TH‐labeled LC dendrites (Van Bockstaele et al. 1996, 1998). The anatomical association of CRF afferents from the CNA with the noradrenergic LC neurons may serve to consolidate the emotional and cognitive component of response to stress (Van Bockstaele et al. 1998; Van Bockstaele et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2019).

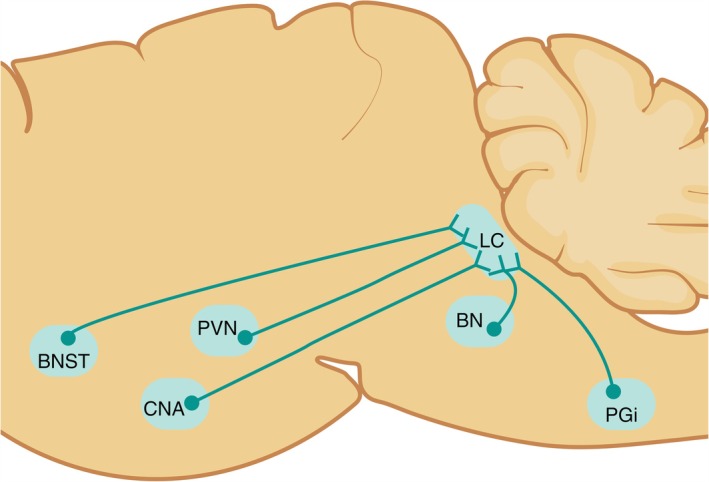

Combining anterograde tracer and electron microscopy shows that CRF‐labeled axon terminals originating from the bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST) also form synaptic specializations with LC noradrenergic dendrites (Van Bockstaele et al. 1999). Another source of CRF afferents in LC is the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) (Valentino et al. 1992). For these studies, anterograde tracing and electron microscopy, as well as retrograde tracing and immunohistochemistry, were utilized to characterize the CRF afferents from the PVN to the LC neurons (Valentino et al. 1992). Using retrograde tracing and immunohistochemistry, additional sources of CRF afferents to the LC were discovered to originate from the Barrington's nucleus and paragigantocellularis (Valentino et al. 1992; Valentino et al. 1994).

The percentages of anterogradely/retrogradely labeled neurons that are CRF‐immunoreactive vary in their nuclei of origin as shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. From the CNA, 35% of anterogradely labeled neurons show CRF‐immunoreactivity (Van Bockstaele et al. 1998), while from BNST only 13% of anterogradely labeled neurons show CRF‐immunoreactivity immunoreactivity (Van Bockstaele et al. 1999). From the Barrington's nucleus, almost one third of retrogradely labeled neurons exhibit CRF immunoreactivity (Valentino et al. 1994) while from the PVN, 30% of retrogradely labeled neurons were CRF immunoreactive (Reyes et al. 2005). Compared to all the other CRF afferents in the LC, nucleus paragigantocellularis recorded the lowest retrogradely labeled neurons with CRF immunoreactivity, only 8% (Valentino et al. 1992). The disparity in the percentages of CRF afferents to the LC may reflect differences in potency of influencing LC neurons. Electrolytic lesions, microdissection, and radioimmunoassay of the CNA result in a significant decline in the CRF concentrations in the LC, whereas lesioning of the PVN causes an elevation of CRF concentrations in LC and a decline in the median eminence (Koegler‐Muly et al. 1993). The opposite directions in which CRF concentrations move in the LC and median eminence following PVN lesions may also be due to the difference in the trajectory of PVN neurons, indeed the LC‐projecting neurons are completely distinct from the median eminence‐projecting neurons (Reyes et al. 2005). In addition, differences in percentages of CRF afferents may be a reflection that CNA, PVN, and Barrington's nucleus may be major sources of CRF afferents to the LC and therefore may impact the LC activity in a neurochemically distinct fashion during stress and neuropsychiatric disorders.

TABLE 1.

Percentages of CRF afferents that project to LC neurons.

| Source/nucleus | Percentage of CRF‐neurons projecting to LC | Tracer/immunohistochemistry | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paragigantocellularis | 8% | Retrograde tracer—Wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase couple to gold/lightfield microscopy | (Valentino et al. 1992) |

| Bed nucleus of stria terminalis | 13% | Anterograde tracer—Biotinylated dextran amine/lightfield microscopy/darkfield/electron microscopy | (Van Bockstaele et al. 1999) |

| Paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus | 30% | Retrograde tracer—Wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase couple to gold or fluorogold/immunofluorescence | (Reyes et al. 2005) |

| Barrington nucleus | 33% (1/3) | Retrograde tracer—Wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase couple to gold or fluorescein‐conjugated latex beads/lightfield microscopy/immunofluorescence | (Valentino et al. 1992) |

| Central nucleus of the amygdala | 35% | Anterograde tracer—Biotinylated dextran amine/lightfield microscopy/darkfield/electron microscopy | (Van Bockstaele et al. 1998) |

FIGURE 2.

Schematics showing the corticotropin‐releasing factor (CRF) afferents to the locus coeruleus (LC). The nuclei that send CRF afferents projections to the LC originate from the Barrington's nucleus (BN), bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST), central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA), nucleus paragigantocellularis (PGi), and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN).

5. LC and Prefrontal Cortex

Anatomical and physiological studies have unraveled that neuronal connectivity and circuitry exist between prefrontal cortex and LC (Luppi et al. 1995; Jodo et al. 1998; Breton‐Provencher and Sur 2019). Evidence gathered through the use of anterograde tracers, Phaseolus vulgaris agglutinin or horseradish peroxidase, and the retrograde tracer cholera toxin B subunit, have shown that frontal cortex and LC reciprocally and bidirectionally innervate each other (Luppi et al. 1995). Additionally, experiments utilizing a local infusion of lidocaine or ice‐cold Ringer's solution while simultaneously recording neuronal activity in the frontal cortex and LC, revealed that there is a strong inhibitory influence of the frontal cortex on the tonic LC spontaneous activity (Sara and Herve‐Minvielle 1995). Likewise, lesioning of the dorsomedial or prelimbic region of the prefrontal cortex accompanied by lidocaine microinjection into the diminished LC firing rates and LC cells (Jodo et al. 1998). In these studies, the ascending dorsal bundle was lesioned to ensure that the influence of LC afferents to the frontal cortex was abolished (Jodo et al. 1998), given that the antidromic activation of LC from the prefrontal cortex alters the non‐driven LC neurons via collateralized projections.

6. LC and Stress Response

Exposure to stress increases NE release and activates the HPA axis, the primary neural pathway in stress response, which begins with the release of CRF (Figure 1). Stress and CRF work in concert in response to a stressor (Figure 1). The PVN that contains CRF synthesizing neurons in abundance releases CRF into the hypophysial portal vessels, which in turn send signals to the anterior pituitary gland to release the ACTH in the systemic circulation (Figure 1). Subsequently, the ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex to synthesize and release glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rodents) into the systemic circulation (Figure 1). The glucocorticoids then modulate physiological and behavioral response (Charmandari et al. 2005). Additionally, glucocorticoids systemically send signals acting as a negative feedback mechanism within the PVN (Sawchenko 1987) and hippocampus (Jacobson and Sapolsky 1991). Another neural pathway of stress response is the activation of NE system (Figure 1). The sustained activation of the LC‐NE system is a hallmark of stress given the LC's widespread connections (Figure 1) and physiological attributes. Thus, the concomitant and coordinated actions of NE and CRF promote the acute response to stress (Gresack and Risbrough 2011), by initiating physiological and behavioral adaptations required to manage stressors. Under circumstances of acute stress, NE increases arousal, alertness, and focused attention in the central system; in the periphery, NE's actions increase heart rate, blood flow, blood glucose, and blood flow to skeletal muscles—generally, preparing the body for action.

It is well established that the HPA axis plays a key role in coordinating the body's response to stress. Likewise, the significant role of LC‐NE system in the stress response has been reported and demonstrated in a multitude of studies. Exposure to stress increases CRF release in the LC‐NE that in turn increases LC tonic discharges and ultimately NE release (Young et al. 2021). As LC tonic firing activity is increased upon CRF action, the LC's ability to respond to salient stimuli with phasic firing is compromised and promotes an anxious state (McCall et al. 2015).

6.1. CRF Regulation of the LC Neurons

Alterations in neuropeptidergic system influencing LC‐NE activation may play an important for the pathogenesis of stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders. Clinical studies demonstrated that neuromodulators and neuropeptides play crucial roles in long‐term consequences of chronic and repeated stress exposure (Raskind et al. 2013). Following exposure to a stressor, the release of CRF is important in mediating the acute response to stress to maintain homeostasis critical for survival. However, in the midst of chronic and repeated stress, CRF continues to engage the LC‐NE system, and this has been well investigated. Alterations in the CRF‐LC neuronal systems may in part contribute to the pathogenesis of stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders.

The diverse projections of CRF throughout the brain and several other criteria later established that CRF also acts as a neurotransmitter (Sawchenko et al. 1993) that modulates the activity of the brain neurotransmitter systems. Thus, it is widely recognized that CRF governs diverse physiological and behavioral effects of stress through a machinery engaging CRF‐containing and synthesizing neurons as well as CRF receptors localized in extrahypothalamic structures (Swanson et al. 1983). Upon binding of CRF to CRF receptors, the receptors are internalized. In other words, the CRF receptors are redistributed from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm. The first in vivo evidence of a CRF cognate receptor, CRF type 1 receptor (CRFr), localization in LC neurons was first demonstrated in 2006 (Reyes et al. 2006). While internalization of CRFr was first shown in cultured neurons (Rasmussen et al. 2004), the first in vivo CRFr trafficking was characterized in rat LC dendrites (Reyes et al. 2006). As CRF binds to the CRF receptors, the internalized CRF receptors can either progress to degradation/downregulation or recycling (Reyes et al. 2008).

Outside of the LC‐NE, CRF mediates the stress response through the CRF type 2 receptor (CRFr2). CRF has been shown to regulate the serotonin (5‐HT)‐containing neurons localized in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR) (Valentino and Commons 2005). During stress response, CRF regulates the DR‐5‐HT system via CRFr and CRFr2 which exhibit opposing effects on DR neuronal activity depending on the doses of CRF (Kirby et al. 2000; Pernar et al. 2004). As such, low doses of CRF decrease DR neuronal activity and engage CRFr while higher doses of CRF increase DR neuronal activity and engage CRFr2 (Kirby et al. 2000; Pernar et al. 2004). It is hypothesized that the opposing effects allow passive or active behavioral coping strategies (Valentino and Commons 2005). In fact, in naive rats that were not exposed to stress, CRFr and CRFr2 behaved differently in their distributions within the DR neurons such that CRFr are predominantly localized along the plasma membrane, while CRFr2 are predominantly localized within the cytoplasm. Conversely, in the presence of stress, the distribution was reversed so that CRFr2 are recruited along the plasma membrane, while CRFr are localized within the cytoplasm (Waselus et al. 2009).

While widely distributed throughout the brain, CRF is localized in LC (Morin et al. 1999). As stated previously, CRF afferents to the LC, visualized using high resolution EM, showed that CRF axon terminals from several brain nuclei form synaptic association with noradrenergic LC dendrites but are not co‐localized with them (Van Bockstaele et al. 1996, 1998; Van Bockstaele et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2011). During stressful conditions, radioimmunoassay and immunohistochemistry have shown that CRF levels in LC are profoundly affected and therefore are elevated (Chappell et al. 1986). The CRF neurotransmission in the LC has been shown by a multitude of studies. For example, local intra LC or intracerebroventricular CRF administration elevates LC neuronal discharge rate in vivo (Curtis et al. 1997). The CRF‐induced activation of LC neurons is translated into an increased NE release in LC efferents or target brain structures including the forebrain (Curtis et al. 1997; Curtis et al. 1999).

A diverse range of stressors have been shown to increase LC neuronal activity and NE release or turnover demonstrating a role of endogenous CRF in the activity of LC neurons (Abercrombie and Jacobs 1987; Morilak et al. 1987a, 1987b). Previous studies supporting CRF activation of LC neurons were confirmed when an increase in electrophysiologic LC activity in response to certain stressful stimuli was observed to be prevented by local intracoerulear delivery of CRF antagonist (Curtis et al. 1994; Curtis et al. 1997). Further, the attenuation of the behavioral and autonomic limbs of stress response has been demonstrated when CRF antagonist was administered in the CNS prior to stress exposure (Lenz et al. 1988). Prior exposure to stress or CRF administration affects the CRF regulation of LC‐NE such that the lower doses of CRF increases LC sensitivity producing a greater electrophysiological activity of LC neurons while the higher doses of CRF renders LC less responsive (Curtis et al. 1999). It is likely that increased sensitivity of CRF in the face of a low degree of stress as a result of prior stress increases arousal. Repeated and chronic exposure to a stressor leads to heightened LC activation and hyperarousal that eliminates the ability to focus and complete a task. Taken together, CRF may participate in the adaptation of LC‐NE neurons following repeated or chronic stress exposure, and without an interruption, the process could become maladaptive, dysregulating LC‐NE activation, and in part participate in the progression to a neuropsychiatric disorder.

7. Stress‐Related Psychiatric Disorders

7.1. Anxiety

Although not every exposure to stress drives acute anxiety, as some individuals are vulnerable while others are resilient to stress (Akil and Nestler 2023), exposure to a stressor may drive acute‐induced anxiety to some individuals. This response is important to maintain arousal and vigilance in order to sustain attention which is critical in focusing and completing tasks, such as those involved in evaluating and responding to stressor stimuli. The acute induced anxiety in response to a stressor is adaptive because the short‐term activation of LC may underlie behavioral and cognitive changes beneficial to survival in the face of a threatening condition. Such an increase in LC activation induces a shift creating a state of high behavioral flexibility and scanning attention to environmental cue (Aston‐Jones et al. 1999). Prolonged or chronic LC activation may lead to reduced ability to continuously engage with task‐relevant information that requires not scanning but rather focused responses to the existing environment. Interference to sensory responses is evidently observed in some stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders (Orr et al. 2002).

Potentially prolonged or chronic LC activation may promote progression to stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders as prolonged or chronic engagement of LC in stress induces changes in LC neuronal activity and functions. For example, while exposure to 30‐ to 60‐min restraint stress (Stamp and Herbert 2001; de Medeiros et al. 2005; Keshavarzy et al. 2015) or 1‐day exposure to social defeat (Reyes et al. 2019) upregulated c‐Fos expression in LC neurons, prolonged daily exposure to restraint stress (9 days) or social defeat (5 days) significantly reduced c‐Fos expression (Stamp and Herbert 2001; Reyes et al. 2019). Furthermore, prolonged or chronic stress induced by oral administration of corticosterone for 21 days increased mRNA and protein levels of NE transporter and DBH in the LC (Fan et al. 2014). These increases were accompanied by concomitant increases of mRNA and protein levels of NE transporter and DBH in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex (Fan et al. 2014), the brain regions that form a bidirectional circuit with LC (Luppi et al. 1995). Consequently, elevated NE transporter and DBH leads to an increased behavioral phenotype characteristic of anxiety‐like behavior, assessed using elevated T‐maze and open field (Fan et al. 2014). Meanwhile, the elevated T‐maze (a modified version of the elevated plus‐maze) has been utilized in rodents to test spatial working memory (Rossetti and Carboni 2005; D'Isa et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2022). While raising up LC activity, prolonged or chronic stress exposure in like manner also increases LC sensitivity to subsequent exposure to a stressor. For instance, rats chronically exposed (2–3 weeks) to a cold environment (5°C) showed electrophysiological firing of LC neurons that was significantly increased after foot shock stimulation (Mana and Grace 1997) and intracerebroventricular delivery of CRF (Jedema et al. 2001), indicating that chronic stress may intensify LC reactivity and may heighten NE levels and release throughout the brain to the succeeding stressor thereby increasing LC sensitivity. While chronic stress may lead to stress‐related psychiatric disorders, the habituation of LC‐NE has also been reported (Lachuer et al. 1994) so that chronic stress may not necessarily lead to a psychopathology in all instances. It is likely that the habituation of LC‐NE to a chronic stressor represents resilience, a phenotype that is linked to the inhibition of LC‐NE function (Wood et al. 2010; Chaijale et al. 2013; Reyes et al. 2015; Reyes et al. 2019).

In humans, a study combining high resolution and quantitative magnetic resonance, specifically using ultra‐high field 7‐Tesla MRI demonstrated the association between LC and anxiety in vivo (Morris et al. 2020). In this study, they found that patients with anxiety and stress‐related disorder had larger LC as compared to control participants without anxiety or stress‐related disorders. Of particular interest was the finding that larger LC size was linked with poorer attentional and inhibitory control and higher anxious arousal in participants (Morris et al. 2020).

7.2. Depression and Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder

Stress is associated with the etiology and pathogenesis of depression and PTSD. There is a myriad of factors that contribute to depression and PTSD, including dysregulation of the HPA axis (de Kloet et al. 2006) and the LC‐NE (Schildkraut 1965) (Figure 3). Hence, in the presence of repeated or chronic stress, the response of LC‐NE may contribute to the development of depression and PTSD.

FIGURE 3.

Repeated and chronic exposure to stressors (red arrows on top of the panels) activates the hypothalamic–pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and the locus coeruleus‐norepinephrine (LC‐NE) system. Depression and post‐traumatic stress disorders precipitated by a stressful event is associated with the hypersecretion of the corticotropin‐releasing factor (CRF) leading to elevated CRF levels (green arrows). Left panel: CRF hypersecretion in the PVN (green arrows) leads to CRF release via the hypophysial portal system (red arrow) that sends signals to the anterior pituitary (AP) and to the adrenal gland (AG). Consequently, this cascade of events leads to the dysregulation of the HPA axis (red dotted arrows). Right panel: CRF hypersecretion in the CNA (green arrows) releases CRF to the LC‐NE (red arrow) that leads to the dysregulation of the LC‐NE system (red dotted arrows).

Reports show that depression precipitated by a stressful event is associated with CRF hypersecretion (Lesch et al. 1988). This is supported by elevated CRF levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of depressed patients compared to non‐depressed individuals (Nemeroff et al. 1984). Consistently, patients suffering from PTSD exhibit elevated CRF levels in the cerebrospinal fluid as well (Bremner et al. 1997). CRF hypersecretion is not only observed in the cerebrospinal fluid, but CRF immunoreactivity also increased, as revealed using autoradiographic images in the LC of depressed individuals (Austin et al. 2003). Several brain nuclei send the CRF afferents to LC neurons (Valentino et al. 1992; Valentino et al. 1994; Van Bockstaele et al. 1996, 1998; Van Bockstaele et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2011; Reyes et al. 2019) and anatomical studies have supported that LC‐NE is enriched with CRF fibers (Swanson et al. 1983), supporting the notion of the LC as downstream neural substrate for CRF dysregulation in depression and PTSD.

CRF hypersecretion in the LC‐NE in depression precipitated by chronic or repeated stress exposure (Figure 3) may affect the LC's noradrenergic function as it is well documented that various stressors have the ability to activate the LC‐NE system. CRF release increases the LC‐NE neuronal firing rate, and given the link of heightened LC activation with stress‐induced depression, mirrors the contribution of CRF in the pathogenesis of depression, by directly influencing the LC neuronal activity. CRF hypersecretion dysregulates LC neuronal firing rates characterized by increased tonic LC activity and thereby reducing responses of LC neurons to phasic sensory stimuli (Valentino and Curtis 1991). In this sense, chronic corticosterone treatment, a validated animal model of depression, induces a desensitization of an α2‐adrenoceptors, which exert a tonic inhibitory regulation both in firing rate in LC and in NE release in prefrontal cortex by noradrenergic neurons (Horrillo et al. 2019). These results confirmed that chronic cold exposure decreased α2‐autoreceptor mediated inhibition of noradrenergic neurons (Jedema et al. 2008). Congruent to this theory, depressed patients have shown decreased responses to discrete stimuli, such as visual stimuli and painful electrical stimuli (Buchsbaum et al. 1981). In response to a phasic sensory stimuli, LC firing discharge is characterized by a brief period of about 80–100 ms of elevated LC discharge occurring 15–20 ms after the stimulus, then followed by the post‐activation pause which is described as a longer period of relatively decreased LC discharge (Valentino and Curtis 1991). Impairment of sensory responses has been observed in individuals with stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders such as PTSD (Orr et al. 2002). Individuals with PTSD exhibited increased attention to task‐irrelevant related information and decreased attention to task‐relevant information (Orr et al. 2002).

7.3. Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

AUD as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) “is a medical condition characterized by an impaired ability to stop or control alcohol despite adverse social, occupational, or health consequences” (NIAAA 2024). Colloquially, AUD is referred to as alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, alcohol addiction and alcoholism (NIAAA 2024). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM‐5), combines alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence as AUD (Alcoholism 2013).

Similar to other addictive substances, acute use of alcohol initially activates the dopaminergic reward system (Spanagel 2009). The activation of reward system causes positive reinforcement promoting the continued use of alcohol. However, when continued alcohol use becomes a mechanism to circumvent the negative effects of withdrawal, then negative reinforcement ensues (Koob and Le Moal 2005). Alcohol withdrawal serves as a harbinger that dependence has just been established, and the addiction cycle has been initiated. Each of the three stages of the addiction cycle—binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation—is impacted by stress. A bidirectional interactions exist between alcohol and stress, such that the use of alcohol to alleviate psychological distress from symptoms of a neuropsychiatric disorder (Buckheit et al. 2020) intersects with the impact of alcohol on the brain and behavior (Homish et al. 2019). Withdrawal from alcohol is a stressor fueling continued alcohol use, while continued alcohol use increases stress‐related symptoms (Sinha 2008).

Similar to stress (Charmandari et al. 2005), acute or chronic alcohol use also activates the HPA axis (King et al. 2006; Richardson et al. 2008). Acute alcohol use activates the HPA axis that increases the circulating glucocorticoids and stimulates the acute release and elevation of the ACTH (Richardson et al. 2008). Conversely, chronic ethanol use dysregulates the HPA axis by blunting the corticosterone response and causing adrenal hypertrophy (King et al. 2006). As HPA axis dysregulation is evident with chronic alcohol use, it is hypothesized that the HPA dysregulation which occurs during stress drives the continued use of alcohol (Buckheit et al. 2020). Acute and chronic alcohol use produces behavioral phenotypes that are contradictory to each other in terms of anxiety‐related behaviors. While acute alcohol use decreases anxiety, and this is anxiolytic (Varlinskaya and Spear 2006), chronic alcohol use increases anxiety, and anxiogenic (King et al. 2006). This is evidenced in preclinical studies, which show that acute alcohol use increases exploratory behaviors as assessed in elevated zero maze paradigm, which is associated with the anxiolytic effects (Acevedo et al. 2014). A significant decrease in the exploratory behavior was observed following chronic alcohol use (Retson, Reyes, and Van Bockstaele 2015), demonstrating a reversal effect of chronic alcohol on the anxiety phenotype from being anxiolytic to being anxiogenic as the alcohol use transitions from acute to chronic. While the anxiolytic effects during acute alcohol use (Acevedo et al. 2014) and transitioning to anxiogenic effects during chronic alcohol use (Retson, Reyes, and Van Bockstaele 2015) have been established, withdrawal from chronic alcohol use, characterized by compulsive drug taking and anxiety, is a significant concern in AUD because it drives AUD patients to relapse, thereby returning alcohol users to compulsive use long after acute withdrawal (Koob and Le Moal 2005). Preclinical studies show that acute and chronic alcohol exposure also engages LC‐NE. Alcohol exposure alters the LC neuronal activity using c‐Fos as a marker of activation (Retson, Reyes, and Van Bockstaele 2015; Robinson et al. 2020).

8. Sex Differences in Stress‐Related Psychiatric Disorders

Stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, and PTSD are more prevalent in women compared to men, as women are roughly twice as likely to suffer from these neuropsychiatric disorders (SAMHSA 2021). Additionally, while a higher prevalence of AUD was reported in men (Grant et al. 2015), greater signs of depression are evident in alcoholic women compared to alcoholic men (Guinle and Sinha 2020).

The LC‐NE may contribute to the sex differences in the prevalence of stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders. That is because not only is the LC‐NE system a stress responsive nucleus in the presence of a stressor, but evidence shows that the LC structure in the female rats is characterized by greater LC size and higher number of noradrenergic neurons compared to adult male rats (Luque et al. 1992). In addition, studies in humans reported lower number of LC neurons in men (mean = 15,731 neurons), compared to women, (mean = 18,300 neurons) (Busch et al. 1997; Ohm et al. 1997). Nevertheless, the sex differences in rats' LC size and number of noradrenergic neurons are dependent on strain (Garcia‐Falgueras et al. 2006). These animal and human studies suggest similarity of human LC with some strains of rats, and it is likely that larger LC and a greater number of noradrenergic neurons would mean greater LC activation during stress in women and greater vulnerability amid stress in women. These strain‐dependent sex differences in LC size may result in behavioral and physiological consequences. However, given the similarity in sex‐dependent LC size disparities in humans and some rat strains, it would be informative to investigate whether the larger LCs observed in females have behavioral and physiological consequences, and whether this may contribute to a higher prevalence of stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders in women.

Adult female rats exhibit dendritic processes that are denser and extend to a greater area compared to adult male rats (Bangasser et al. 2011). In addition, analysis of individual LC neurons revealed that dendritic trees in adult female rats are longer while Sholl analysis (a quantitative method to evaluate the morphological characteristics and complexity of dendritic arborization) of LC dendritic processes present a more complex branching pattern compared to male rats (Bangasser et al. 2011). Using immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin, an integral synaptic vehicle protein, a significantly greater immunoreactivity was seen in the female rats compared to male rats (Bangasser et al. 2011) suggesting greater synaptic contact on LC‐dendritic process that receive innervation from diverse CRF afferents (Valentino et al. 1992; Valentino et al. 1994; Van Bockstaele et al. 1996, 1998; Van Bockstaele et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2011; Reyes et al. 2019) and indicate that there may be greater increase LC activation in the female rendering greater vulnerability to stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders. Sex differences in the LC dendritic tree and architecture may be mediated by the sex hormones, estrogen, and testosterone. Previous reports showed that while estrogeninduces dendritic growth, spinogenesis, and synaptogenesis in Purkinje cells in the cerebellar neurons (Sasahara et al. 2007), testosterone induces pruning of dendrites and spines in the medial amygdalar neurons (Zehr et al. 2006). It is also likely that sex differences in LC dendrites are attributed to CRF, as reports showed that CRF increases dendritic length and dendritic branching in the developing hippocampus using CRFr knock out mice (Chen et al. 2004). In addition, CRF also prompts neurite outgrowth in immortalized noradrenergic neuronal CATH.a cells that resemble LC‐derived neurons (Cibelli et al. 2001). Cibelli and colleagues concluded that CRF exerts its functions via the cAMP and MAP kinase signaling pathways (Cibelli et al. 2001). Similarly, CRF promotes LC neuronal growth and arborization and these structural effects of CRF require CRFr activation, and protein kinase A, MAP kinase, and Rac1 signaling pathways (Swinny and Valentino 2006).

Sex‐dependent differences were also observed in LC's response to stress or CRF activation of LC neurons. A greater LC activation was observed in females compared to males following exposure to hypotensive stress (Curtis et al. 2006). Likewise, CRF administered at a low dose caused a shift to the left of the CRF dose–response curve, thereby increasing LC neuronal firing in the female, but a similar low dose was unsuccessful in activating LC neuronal firing in the male (Curtis et al. 2006). Prior history of stress exposure, including swim stress and foot shock impairs the CRF‐mediated activation of LC‐NE system in a sex‐dependent manner, such that in the female LC, CRF was 10–30 times more potent in activating LC neurons than in male rats (Curtis et al. 2006). On the other hand, a previous history of stress exposure changes the CRF‐dose response curve for LC activation in the male causing a shift to the left but not in females, so that low CRF doses in males increases LC neuronal activation (Curtis et al. 2006).

Alteration of activity in CNA neurons that are specifically CRF‐containing neurons also exhibit sex‐dependent differences following alcohol exposure (Retson, Hoek, et al. 2015). In one study, c‐Fos activity in female rats was greater compared to controls while a comparable c‐Fos activity was observed in male control and ethanol‐treated rats (Retson, Hoek, et al. 2015). Regarding long‐term CNA activation, use of δFosB as a marker showed that female rats have significantly elevated δFosB consistent with greater elevation of c‐Fos compared to control rats after chronic ethanol exposure (Retson, Hoek, et al. 2015). Moreover, chronic alcohol exposure in the male rats, fueled an increased δFosB expression compared to control. Taken together, these results suggest that, while males habituate to CNA activation following alcohol exposure, females do not habituate to alcohol exposure in this way, which may contribute to sex‐dependent differences in AUD (Retson, Hoek, et al. 2015). Additionally, it was also reported that δFosB in CRF‐containing neurons in the CNA that are activated by chronic alcohol exposure are increased in male rats compared to control (Retson, Hoek, et al. 2015). The LC receives CRF afferents from the CNA (Van Bockstaele et al. 1998; Reyes et al. 2019) as described earlier, and CRF and LC‐NE are important components of stress and are indispensable systems for stress‐induced and drug‐seeking and relapse (Smith and Aston‐Jones 2008). Future studies should interrogate whether the CRF‐containing neurons in the CNA that project to the LC are engaged in a sex‐dependent fashion during acute and chronic alcohol exposure as well as alcohol withdrawal.

Excessive activation of LC neurons because of CRF hypersecretion necessitates compensatory mechanisms that promote homeostasis. Internalization of CRF receptors is one mechanism to protect LC neurons from excessive activation and regulate postsynaptic sensitivity to CRF. While stress‐ or CRF‐mediated CRFr internalization was observed in the male, it was not observed in the female (Reyes et al. 2006; Reyes et al. 2008; Bangasser et al. 2010). This mechanism was also observed in genetic models of CRF‐overexpressing mice that showed dense innervation of CRF in the LC in both male and female mice, compared to their wildtype counterparts (Bangasser et al. 2013). However, females showed elevated LC discharge rates compared to male CRF‐overexpressing mice. Moreover, CRFr internalization was only observed in male CRF‐overexpressing mice and not in female CRF‐overexpressing mice suggesting that the cellular adaptation of CRFr internalization and the compensatory mechanism of CRFr internalization to protect LC neurons from excessive CRF may be compromised in females (Bangasser et al. 2013).

Furthermore, chronic alcohol exposure induced a predominant localization of CRFr along the plasma membrane only in the female but not in the male (Retson, Hoek, et al. 2015), and this is consistent to the CRFr localization pattern described following stress exposure in the female but not in the male (Bangasser et al. 2010; Bangasser et al. 2013). The sex‐dependent differences in CRFr trafficking may underlie predisposition of female LC‐NE to conditions resulting in elevated CRF in LC. Persistent elevated CRF leads to excessive LC neuronal activity, which has been linked to arousal (Aston‐Jones and Bloom 1981; Berridge and Foote 1991). Hence, in the female, the lack of stress‐mediated CRFr internalization when CRF is hypersecreted may predispose the female to hyperarousal which is one of the symptoms observed in stress‐induced neuropsychiatric disorders.

9. Resilience to Stress and LC

While the intensity, duration, and magnitude of a challenge or stressor may vary depending on the specific situation or event, the response of each individual to the same challenge or stressor is also variable. Particular individuals may be vulnerable when faced with stressors and may easily develop stress‐related psychiatric disorders, while other individuals may be more resistant to the development of stress‐related psychiatric disorders—and notably, this vulnerability/resistance may be dependent on the individual stressor or stressor type. Resilience is a broad term to describe the neuropsychological and behavioral traits underpinning this phenomenon, defined by the National Institutes of Health (Office of Dietary Supplements, accessed Jan 6 2025) as encompassing “the capacity to resist, adapt to, recover, or grow from a challenge.” Understanding the mechanisms underlying resilience is vital in targeting treatments to alleviate the symptoms of stress‐related psychiatric disorders. Recently, longitudinal data in animal models, such as swine, showed that resilience traits show low to moderate heritability, when measured in response to deviations in parameters including body weight, feed intake and feeding behavior (Gorssen et al. 2023), confirming the notion of interindividual variability in response to stressors and suggesting a strong genetic component to resilience in the face of stressors.

Animal models of resilience and/or vulnerability to stress have emerged in the past two decades with the aim of elucidating the role of LC‐NE in resilience and vulnerability. For example, the repeated social defeat paradigm (Wood et al. 2010; Chaijale et al. 2013; Reyes et al. 2015; Reyes et al. 2019) has been adapted and modified from the resident‐intruder model originally designed by Miczek (Miczek 1979) and used to show that vulnerable and resilient individuals can be generated and identified using this paradigm (Wood et al. 2010; Chaijale et al. 2013; Reyes et al. 2015; Reyes et al. 2019). In response to a single resident‐intruder exposure, intruder rats with a relatively short latency to defeat were identified as vulnerable or short latency (SL) phenotype. With repeated stress exposure, rats exhibited either a SL or long latency (LL) to defeat. LL rats were identified as resilient phenotype (Wood et al. 2010; Chaijale et al. 2013; Reyes et al. 2015; Reyes et al. 2019). Vulnerable (SL) and resilient (LL) phenotype animals also displayed neurophysiological differences related to LC function. Vulnerable (SL) phenotype animals showed HPA axis dysregulation and behavior similar to melancholic depression, while resilient (LL) phenotype animals demonstrated proactive behavior in resisting defeat that was linked with decreased efficacy of CRF (Wood et al. 2010). In addition, vulnerability was linked to an increase in ACTH and corticosterone release during the chronic social stress and decrease in pituitary level of CRFr (Wood et al. 2010). Vulnerability was associated with predominant CRFr localization along the plasma membrane, whereas resiliency was associated with predominant cytoplasmic CRFr localization (Reyes et al. 2019). With repeated stress, resilient and vulnerable rats demonstrated defined patterns of neuronal activation. Resilient rats showed significant activation of the nucleus paragigantocellularis‐enkephalinergic LC afferents but not the CNA‐CRF LC afferents or LC neurons (Reyes et al. 2015; Reyes et al. 2019). This mechanism may be partially mediated by the stress‐induced downregulation of delta opioid receptors (DORs) in the LC during stress (Tkaczynski et al. 2022). Notably, overexpression of DORs in the LC has been shown to inhibit stress‐induced LC firing activity and anxiety‐like behavior (Tkaczynski et al. 2022). Conversely, vulnerable rats showed significant activation of LC neurons and CNA‐CRF LC afferents but not the paragigantocellularis‐enkephalinergic LC afferents (Reyes et al. 2015; Reyes et al. 2019). Electrophysiological studies have shown that resiliency is also influenced by age and sex. In adult male and female rats, LC firing was resilient to the long‐term effects of acute stress. However, in adolescent rats at 1 week post‐stress exposure, LC firing was significantly decreased in female rats but increased in male rats (Borodovitsyna et al. 2022). In addition, combining retrograde tracing and ex vivo slice recording revealed that LC neurons projecting to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) increased LC firing activity exclusively in resilient mice (Zhang et al. 2019). Furthermore, with the use of optogenetic technique to mimic activation of LC neurons projecting to the VTA, a resilience‐type phenotype could be produced in vulnerable mice. This resilience mechanism requires the expression of alpha1 and beta3 adrenergic receptors in VTA dopaminergic neurons to induce the resilience‐like behavior (Zhang et al. 2019).

An epidemiologic community study showed that samples from PTSD patients exhibited high levels of catecholamines (Young and Breslau 2004). Moreover, the levels of cortisol and catecholamines (e.g., NE) in PTSD patients were associated with subsequent symptoms of PTSD 1 month after exposure to trauma (Delahanty et al. 2000). These clinical studies highlight the participation of LC‐NE in adaptive response to stressor. Clinical studies attempting to define biomarkers for PTSD resilience among military service members post‐deployment demonstrated alterations in the catecholamine levels associated with PTSD symptoms. Specifically, within 2 months after return from deployment, lower NE blood levels were evidently associated with lower PTSD symptoms three months post‐deployment, particularly in association with intensity and avoidance symptoms (Highland et al. 2015). Another clinical study involving PTSD patients showed a direct association of LC hyperactivity with the PTSD symptom of hyperresponsiveness (Naegeli et al. 2018). Using psychophysiological recording and fMRI during passive exposure to a brief, 95‐dB, loud sound occurring intermittently demonstrated that an increased autonomic hyperresponsiveness was linked to a significantly larger response of the LC in trauma‐exposed PTSD patients, but not in non‐PTSD trauma‐exposed cohorts (Naegeli et al. 2018). Taken together, these clinical studies demonstrate the role of LC‐NE system activation in vulnerability to stress and that LC‐NE diminished activation appears to provide resilience against stressors.

10. AD and LC

Given the central role of LC‐NE in attention, arousal, cognition, memory, and stress response, the involvement of LC‐NE in neurodegenerative diseases such as ad has been the target of research endeavors as early as 1906 when Alois Alzheimer commenced the research to define the link between the brain and the mental illness (Ellison 2025). Contributing to 60%–70% of total dementia cases worldwide, AD is considered as the most common form of dementia and disproportionately affects women (World Health Organization 2022), a gender disparity which exists in ad prevalence globally and is not wholly explained by the longer average lifespan of women. Indeed, this disparity aligns with the tendency of increased prevalence of stress‐related psychiatric disorders in general among women. Whether this disparity is contributed to the sex differences that exist within the LC‐NE system needs further investigation. One of the neurophysiological hallmarks of ad pathology is the remarkable and progressive degeneration of the TH neurons in the LC (Kelly et al. 2017) and marked degeneration of LC in postmortem brain of ad patients (Brunnstrom et al. 2011). The progressive degeneration of TH‐containing neurons in the LC suggests a decreased NE supply in ad which alters the firing patterns of LC neurons, both the tonic and phasic. Given that LC releases NE in brain nuclei involved in memory, including the hippocampus, amygdala and prefrontal cortex, degeneration and decreased NE impacts LC functions during ad disease processes, including memory formation and retrieval (Loughlin et al. 1986; Luppi et al. 1995; Jodo et al. 1998; Breton‐Provencher and Sur 2019). Moreover, degeneration of the LC‐NE is accompanied by significant decrease in LC integrity (Brunnstrom et al. 2011; Kelly et al. 2017). Clinical studies using 3T MRI revealed that tau pathology has been demonstrated in the LC earlier compared to other brain regions (Olivieri et al. 2019). Importantly, reduced NE from the LC is associated with increased amyloid beta and tau pathologies across the brain in ad patients (Pamphlett and Kum Jew 2015). These findings have clinical implications and that the LC‐NE may be an important region in the early pathology of ad and may potentially be a target in the treatment of ad.

11. Implications of LC‐NE System Dynamics in Therapeutic Strategies

It has been established that repeated exposure to stress may be associated with psychiatric disorders. Stress—whether acute or chronic—impacts the LC‐NE system's response to acute stress by increasing NE release, which promotes a canonical stress response with the purpose of producing adaptation that enables the organism to cope with the stressor. Chronic or repeated exposure to stress increases synthesis and utilization of LC‐NE stress response that may increasingly amplify or “ramp up” the LC reactivation to subsequent stressors and thereby leads to the dysregulation of the LC‐NE system. In turn, dysregulation induces complex behavioral and neural and neuroendocrine responses that may eventually lead to neuropsychiatric pathology.

Using the Montgomery conflict test, a behavioral test used to investigate anxiety‐like behavior in rodents, it was shown that the typical benzodiazepine diazepam, and the triazolo‐benzodiazepine alprazolam both counteracted the anxiogenic response in rats typically seen in this paradigm (Soderpalm and Engel 1989). Moreover, benzodiazepine treatment significantly attenuates stress‐induced NE release in the LC and stress‐induced negative emotions (Tanaka et al. 2000). These preclinical studies demonstrate direct targeting of the LC‐NE system. Binding sites of benzodiazepines have been demonstrated in postmortem human LC tissue (Hellsten et al. 2010). Given that benzodiazepines are fast‐acting, they are commonly‐used anxiolytics for the treatment of anxiety in human. Diazepam for example has a long half‐life and provides immediate anxiolytic relief. Targeting LC‐NE by benzodiazepines offers immediate relief and is recommended for short‐term use in humans, given the risk of dependency when utilized for longer periods of time (de las Cuevas et al. 2003). Whether the benefit of benzodiazepines treatment outweighs the potential risk of dependency for certain treatment regimens, individuals, and situations and whether dependency engages the LC‐NE system are still crucial outstanding questions and are the target of ongoing research.

The use of in vivo extracellular recordings in rats has shown that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) significantly decrease LC‐NE neuronal firing rate (Szabo and Blier 2002). In addition, SSRIs decrease LC‐NE activation following stress exposure (de Medeiros et al. 2005). As SSRIs decrease LC neuronal firing rate and activation, it may lead to significant reductions in anxiety‐related behavior (Muigg et al. 2007). Commonly used for their antidepressant and anxiolytic effects, SSRIs are known as the first line of medication in anxiety disorders because of their safety profile and the reduced safety and misuse concerns as compared to other medications like benzodiazepines (Bandelow et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2019).

The sex differences demonstrated in the LC‐NE system in both pre‐clinical and clinical studies may suggest variability in the effectiveness of various therapies and treatment for stress‐related psychiatric disorders in women versus men patients. For instance, it has been demonstrated that use of the beta‐blocker propranolol during reconsolidation of traumatic memories (a therapy technique that plays an important role in the treatment of PTSD) resulted in increased effectiveness of the reconsolidation process in women as compared to men (Gray et al. 2019; Lonergan et al. 2013).

Several clinical trials have also revealed that tricyclic antidepressants, which block the reuptake of serotonin and NE in the presynaptic terminals and thereby increasing the levels of these neurotransmitters, are more effective in men compared to women. Conversely, SSRIs show a significantly increased effectiveness in women as compared to men; interestingly, this efficacy diminishes as menopause begins (Kornstein and McEnany 2000). Thus, it is recommended that gender and menopausal status should be considered in choosing the antidepressant for depressed patients (Kornstein and McEnany 2000). In addition, such sex differences may contribute to greater vulnerability among women in benzodiazepine use and abuse in stress‐related psychiatric disorders (Zamboni et al. 2022).

A variety of animal models have been utilized to provide understanding of the role of the LC‐NE system in the pathophysiology of stress‐related psychiatric disorders and their treatments. However, it is also recognized that a gap continues to exist in the complexities of the pathological, psychological, and physiological processes underlying stress‐related psychiatric disorders. For instance, the complex nature of the human stressors at work—including stress resulting from experiencing discrimination, financial hardship, workplace challenges, housing instability, and nightmares among PTSD patients—are uniquely human experiences that cannot be effectively modeled in animals. Thus, it is worth stating that animal models are not suitable to fully replicate the human condition of stress exposure and are not capable of answering the many of the most nuanced questions. The gap between animal models and humans is a critical factor that may potentially contribute to the decreased efficacy or failure of some drugs that have been shown to be effective when pre‐clinically tested in animal models for the treatment of psychiatric disorders (Spierling and Zorrilla 2017). Translation of research results conducted in animal models into humans poses a challenge that must be taken into a consideration. Clinical studies continue to be a crucial bridge for validation of therapeutics and treatment and remain the only way to verify that outcomes obtained in animal models are truly translatable to humans.

12. Conclusions

Stress is a constant, inevitable, and common element woven into the fabric of human life. Exposure to stress not only increases the activation of the HPA axis but also increases the activation of the LC‐NE system. While diverse functions are ascribed to LC‐NE, its role in stress response implicates the LC‐NE in the pathophysiology of stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders. Great strides have been made in demonstrating that dysregulation of LC‐NE neurocircuits underlies the development of neuropsychiatric disorders. Central to stress is the activation of CRF, which orchestrates the stress response by promoting a cascade of immediate and persistent cellular and molecular changes (Chappell et al. 1986; Lenz et al. 1988; Koegler‐Muly et al. 1993; Curtis et al. 1997; Curtis et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2006; Reyes et al. 2008; Bangasser et al. 2010; Bangasser et al. 2013; Reyes et al. 2019). As CRF afferents are abundantly localized in the LC‐NE system (Valentino et al. 1992; Valentino et al. 1994; Van Bockstaele et al. 1996, 1998; Van Bockstaele et al. 1999; Reyes et al. 2011; Reyes et al. 2019), CRF's release immediately activates LC‐NE (Curtis et al. 1997; Young et al. 2021) with broad projections throughout the neuroaxis. However, prolonged, persistent, and repeated CRF release and hypersecretion dysregulates the LC‐NE system that ultimately promotes long‐lasting cellular changes, eventually impacting the functions of the LC‐NE and brain areas innervated by LC neurons and its noradrenergic neurotransmission. This cascade of events could lead to stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders (Nemeroff et al. 1984; Lesch et al. 1988; Bremner et al. 1997). Indeed, stress via the CRF‐LC‐NE pathway promotes synaptic plasticity that allows dynamic adaptation at the initial or acute stress exposure. Nevertheless, prolonged and persistent activation of the CRF‐LC‐NE pathway may partly explain symptoms of stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders. This pathway likely constitutes a mechanism by which prolonged and persistent stress succumbs to dysregulation of LC‐NE system thereby pointing to its essential role in the development of stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders.

Significant gaps in our knowledge remain regarding the mechanism and neuronal circuitry underlying sex‐dependent differences in stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders. Given the higher prevalence of stress‐related neuropsychiatric disorders in women (SAMHSA 2021), the higher prevalence of AUD in men (Grant et al. 2015) and the greater signs of depression are evident in alcoholic women (Guinle and Sinha 2020) behooves a better understanding of sex differences in CRF‐LC‐NE pathway function. Improved understanding of this system will aid in improved targeting of therapeutic approaches that can be individualized and eventually pave the way for better treatment outcomes.

Author Contributions

Beverly A. S. Reyes: conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1111/ejn.70111.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Drs. Catherine C. Theisen, Igor Horrillo, Kenny Simansky, and Jacqui Barker for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institute On Alcohol Abuse And Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R21AA030361 to BASR. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

All figures were created using Biorender.com.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R21AA030361 to B.A.S.R.

Associate Editor: Yoland Smith

Data Availability Statement

This is a review article and does not include experimental data.

References

- Abercrombie, E. D. , and Jacobs B. L.. 1987. “Single‐Unit Response of Noradrenergic Neurons in the Locus Coeruleus of Freely Moving Cats. I. Acutely Presented Stressful and Nonstressful Stimuli.” Journal of Neuroscience 7: 2837–2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo, M. B. , Nizhnikov M. E., Molina J. C., and Pautassi R. M.. 2014. “Relationship Between Ethanol‐Induced Activity and Anxiolysis in the Open Field, Elevated Plus Maze, Light‐Dark box, and Ethanol Intake in Adolescent Rats.” Behavioural Brain Research 265: 203–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akil, H. , and Nestler E. J.. 2023. “The Neurobiology of Stress: Vulnerability, Resilience, and Major Depression.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 120, no. 49: e2312662120. 10.1073/pnas.2312662120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholism NIAAA. NIAAANIHGOV . 2013. “Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DMS‐IV and DSM‐5”.

- Antila, H. , Kwak I., Choi A., et al. 2022. “A Noradrenergic‐Hypothalamic Neural Substrate for Stress‐Induced Sleep Disturbances.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119: e2123528119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston‐Jones, G. , and Bloom F. E.. 1981. “Norepinephrine‐Containing Locus Coeruleus Neurons in Behaving Rats Exhibit Pronounced Responses to Non‐Noxious Environmental Stimuli.” Journal of Neuroscience 1: 887–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston‐Jones, G. , Rajkowski J., and Cohen J.. 1999. “Role of Locus Coeruleus in Attention and Behavioral Flexibility.” Biological Psychiatry 46: 1309–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin, M. C. , Janosky J. E., and Murphy H. A.. 2003. “Increased Corticotropin‐Releasing Hormone Immunoreactivity in Monoamine‐Containing Pontine Nuclei of Depressed Suicide men.” Molecular Psychiatry 8: 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow, B. , Reitt M., Rover C., Michaelis S., Gorlich Y., and Wedekind D.. 2015. “Efficacy of Treatments for Anxiety Disorders: A Meta‐Analysis.” International Clinical Psychopharmacology 30: 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangasser, D. A. , Curtis A., Reyes B. A., et al. 2010. “Sex Differences in Corticotropin‐Releasing Factor Receptor Signaling and Trafficking: Potential Role in Female Vulnerability to Stress‐Related Psychopathology.” Molecular Psychiatry 15, no. 877: 896–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]