Abstract

Background

The COVID- 19 pandemic significantly impacted health services, particularly immunisation services, reducing the coverage of measles immunisation from the targeted 95%. This has resulted in post-pandemic measles outbreaks globally, and those at risk in Sabah are the marginalised population, who encounter barriers when it comes to getting measles immunisation. In this study, a community-based intervention was implemented to evaluate the effectiveness of a community-based intervention in improving the measles-containing vaccine (MCV) completion rate and assessing the community’s acceptance of and satisfaction with the proposed intervention programme.

Method

The study applied a cluster randomised control trial (RCT). The intervention involved trained community volunteers who were trained on the reminder and recall strategy to help ensure the completion of the MCV among children in the community, where three doses of measles vaccine were provided when they were 6, 9, and 12 months of age. The intervention was administered in five settlements over a period of six months. As a comparison, another five settlements were provided with regular vaccination health services. The rates of MCV completion between the intervention group versus control group that received regular vaccination health services were then compared. The community’s acceptance of and satisfaction with the intervention were assessed using a validated Acceptability of Intervention Measure-Intervention Appropriateness Measure-Feasibility of Intervention Measure (AIM-IAM-FIM) and Client Satisfaction Questionnaire 8 (CSQ- 8).

Result

The findings of the study showed that the rate of completion of the three doses of measles vaccine was slightly higher among those who received the intervention (80.4%) with a lower percentage having received one dose (2.6%) and no dose at all compared to those who only received routine healthcare services. Furthermore, the odds of having completed the MCV increased by three times for those who received the intervention (AOR: 2.848, 95% CI: 0.176, 45.996), although it was not significant. There was also a six-fold increase in the satisfaction score among those who received the community-based intervention compared to those who received the routine vaccination services (p = < 0.001, 95% CI = 2.634, 8.919). Finally, the majority (97%) of those in the community accepted the implemented intervention.

Conclusion

A community-based intervention has the potential to enhance the completion of MCV, but it has to be refined further to be successful. The findings of this study can provide information to policy makers and implementers of vaccination programmes regarding the importance of engaging marginalised communities and ensuring their acceptance of and satisfaction with the intervention to achieve the desired target.

Trial Registration

This study was retrospectively registered at the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Registry (ISRCTN12774704) on 17 th November 2023.

Keywords: Public health interventions, Community participation, Measles immunisation programme, Social determinants of health

Introduction

Vaccination is essential in preventing child morbidity and mortality caused by measles. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), measles vaccination (MCV) has prevented around 56 million deaths worldwide [1], and the vaccination itself is a cost-effective strategy in developing countries [2]. Nevertheless, there are still children, especially those in high-risk groups, who fail to receive their MCV on time [3]. The COVID- 19 pandemic also contributed to the reduction in MCV coverage worldwide, causing an increase in measles cases in many countries [4].

Malaysia is one of the countries that is committed to eliminating measles and has been supporting the Immunisation Agenda 2021–2030 since 2004 [5]. However, the COVID- 19 pandemic impacted healthcare in Malaysia, as it did in other nations, where routine immunisation services were affected [6] due to restrictions on many activities, resulting in a decrease in measles immunisation coverage [7]. During the pandemic, coverage of the measles-containing vaccine, second dose (MCV2) was 84%, which was below than the aim of 95% for herd immunity, although the proportion has subsequently grown to 95% or higher [8]. The management of public health with regard to measles includes surveillance, case and outbreak investigations, immunisation activities, infection control, and sharing of public health information [5]. Prevention through vaccination is the best action and, based on Malaysia’s vaccination schedule, two doses of measles vaccine are provided to children at the age of 9 and 12 months, according to the WHO recommendation for primary immunisation [9].

However, in the state of Sabah, three doses of measles vaccine are provided. The initial dose is given at six months due to the higher risk of exposure to measles as a consequence of the presence of migrants in the state [10]. These migrants are marginalised and at higher risk of transmitting vaccine-preventable diseases, including measles [11], as they encounter barriers when it comes to accessing health services, especially vaccinations [12, 13]. Before the COVID- 19 pandemic, cases of measles among the unvaccinated marginalised children were usually documented in Sabah, and supplementary vaccination measures to enhance MCV coverage were effective, resulting in a drop of 40% in infections from 2018 to 2019, despite a spike in cases in the adjacent Philippines [14]. Similarly, polio which is a vaccine preventable disease has also been reported in Sabah among the at-risk marginalised communities [15]. In Malaysia, routine vaccinations for children are free and can be obtained by migrants for a minimal fee [11]. Therefore, some may get vaccinated after an outbreak through supplementary immunisation activities (SIAs) [16]. Sadly, SIAs can be delayed or disrupted by a pandemic [17]. However, in Malaysia, there was an increase in SIAs during the recovery period of the pandemic among those who missed their vaccinations [18, 19]. Nevertheless, other strategies should also be considered to complement the available SIAs that are being carried out to increase vaccination coverage, especially among the high-risk groups.

Various studies have concluded that interventions, especially community involvement, can effectively improve the specific needs of marginalised populations living in urban slums and informal settlements worldwide [20]. Therefore, a community-based intervention, which is a multi-component intervention for marginalised communities [21], could complement existing routine vaccination services. In addition, combining strategies for a targeted population based on their specific barriers could increase the likelihood of vaccination completion. Studies have also concluded vaccine uptake among children in high-risk groups can be effectively increased through recall strategies [22], including home visits [23] and outreach activities by community volunteers [24]. Thus, having a community-based intervention, where community volunteers provide reminders, make home visits, and assist as needed could produce better outcomes. Nevertheless, more evidence is needed to establish the effectiveness of community-based interventions, especially targeting marginalised populations, who are the primary contributors to measles cases in Sabah.

In Malaysia, several health initiatives involving community-based interventions have been established to combat dengue and non-communicable diseases [25, 26]. However, community-based participation has yet to be employed in vaccination healthcare services to improve vaccination coverage. In some countries, community-based interventions have effectively enhanced prenatal and neonatal health outcomes [27]. However, to ensure the successful implementation of these interventions, specific standards and criteria must be followed, depending on the context [28]. It is advantageous to empower a community as it is a sustainable way of achieving the vaccination coverage target of 95% or herd immunity. This method is also impactful, especially since it involves a collaborative design with a bottom-up approach, based on the needs of the targeted marginalised community [29]. Therefore, this research was aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of a community-based intervention in improving the MCV completion rate and assessing the community’s acceptance of and satisfaction with the proposed intervention programme.

Methods

Study population and setting

This study was conducted in Kota Kinabalu, the capital of Sabah, located on the island of Borneo. This city is the principal gateway into Sabah and, being a major transit centre, many immigrants have established informal settlements within the city. These informal settlements have become the most impoverished areas, and many of the people living here do not have equitable access to healthcare.

The participants for this study were children living in 10 informal settlements in the district of Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. Subjects are assigned randomly to intervention and control and comparison between the control and intervention enable the effect to be determined. The eligibility criteria included: (i) born between October 2021 and March 2022, (ii) positive parental consent, and (iii) children of parents living in informal settlements for ≥ 6 months. The exclusion criteria included: (i) children with contraindications toward the MCV, and (ii) children of parents who were community volunteers at these informal settlements. The participant’s parents or caretakers needed to have access to a mobile phone, through which the intervention was done. For those who did not own a phone, the enrolment was paused until the participant confirmed with the owner of the shared phone that text messages and incentives, as applicable, could be sent to the mobile phone. Other than that, the vaccination status of the children was determined through a review of their medical records, and irrespective of the group allocation, all the children were able to receive the routine vaccination services provided at health clinics.

Study design

A cluster randomised control trial (RCT) was conducted to study the effectiveness of a community-based intervention in improving MCV coverage through the involvement of community volunteers. The study was conducted in 10 informal settlements of the marginalised population in Kota Kinabalu from March 2022 to March 2023. All the participants completed their follow-up upon reaching the age of one by the end of the study period. It was hypothesised that the implementation of the community-based intervention would be able to improve the completion of three MCV doses among the children of the marginalised population. The intervention was conducted in collaboration with clinics under the management of the Kota Kinabalu District Health Office and the communities living in the areas. The acceptance and perception of the communities living in the study areas regarding the intervention programme were gauged before the study [30]. Thus, the conduct, analysis, and reporting of the trial were according to the guidelines of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) that had been adapted for a cluster RCT [31].

For a cluster RCT, response bias, sampling bias, and attrition bias, were taken into consideration. Allocation bias could occur in a cluster randomised control trial design, particularly if the process of randomly assigning clusters to intervention and control groups was not properly concealed, whereas recruitment bias could occur if the process of recruiting participants into the study was influenced by knowing which cluster (intervention or control) they belong to, undermining the validity of the outcome. Furthermore, attrition bias may arise when participants drop out of the research in an unplanned manner, resulting in a systematic difference between the intervention and control groups, possibly skewing the trial findings owing to missing data from those who left the study. As a result, allocation bias was eliminated by centralising randomisation, whereas recruitment bias was eliminated by implementing precise inclusion criteria for participant selection in order to reduce discretion. To limit bias, attrition bias was avoided by regularly monitoring cluster participation to resolve concerns that might cause them to drop out, as well as utilising intention-to-treat analysis, in which all clusters participating in the research were evaluated even if they had incomplete data.

Randomisation

The clusters in this study were the 10 informal settlements of marginalised populations, and they were randomly assigned and evenly allocated to two groups (Table 1). The simple randomisation process was done using R software to designate each informal settlement to the assigned cluster. The settlements were chosen based on five criteria: (i) a community that included legal and illegal migrants, (ii) a majority of the community members were socially excluded, (iii) a majority of the community members had difficulties in gaining access to healthcare, (iv) lived in urban settlements, and (v) had low vaccination coverage. They were excluded from the trial if they had ongoing community health programmes that could result in bias in the study outcome. A total of 10 informal settlements were involved, where five settlements received the community-based intervention, while five received no intervention and only routine vaccination services. A cluster RCT was preferred to an individually randomised approach to avoid potential contamination of intervention activities within the clusters.

Table 1.

Localities under the trial arms cluster for community-based intervention to improve measles vaccination completion in marginalised community settlements in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, from March 2022 to March 2023

| Intervention Cluster | Control Cluster |

|---|---|

| Kampung Lok Urai | Kampung Skim Penempatan |

| Kampung Kesuapan | Kampung Cenderakasih |

| Kampung Gaya Tengah | Kampung Delima |

| Kampung Gaya Asli | Kampung Kalasanan |

| Kampung Pondo | Kampung Numbak |

Intervention

The community-based intervention in this study used a reminder and recall strategy done by community volunteers through the creation of a program called the Measles Intervention Involving Community Action (MIICA) which sought to improve the completion of MCV among children from marginalised populations (Fig. 1). This intervention was done to address barriers in the community before the study [30]. For the marginalised population, one of the barriers was that those who were non-Malaysian had to pay a minimal fee for vaccination. As a result, those in the intervention group received messages from community volunteers recruited from the same informal settlements who reminded them of their appointments at the health clinic for their three MCV doses. The vaccination appointment dates were relayed to the community volunteers by the principal researcher. Then, the community volunteers relayed the intervention message via SMS to inform the participants to go to the health clinic to receive their MCV on the scheduled date.

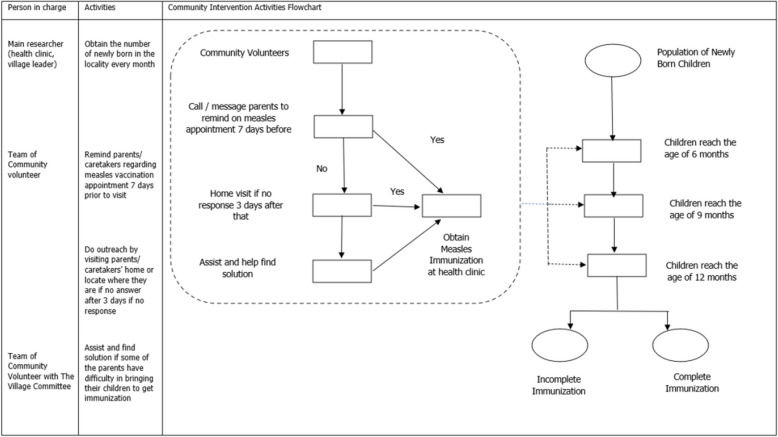

Fig. 1.

Community intervention activities flowchart

For the intervention group, SMS reminders were delivered seven days before the scheduled MCV date at ages 6, 9, and 12 months. If the parents or caretakers did not respond and the participants missed their vaccination appointments, the community volunteers would make a home visit three days later to assist them so that the participants could get their vaccinations. The participant’s vaccination status was then documented in the maternal and child’s health (MCH) booklet. If the MCH booklet was not available, a verbal report of the vaccination history was taken.

Control

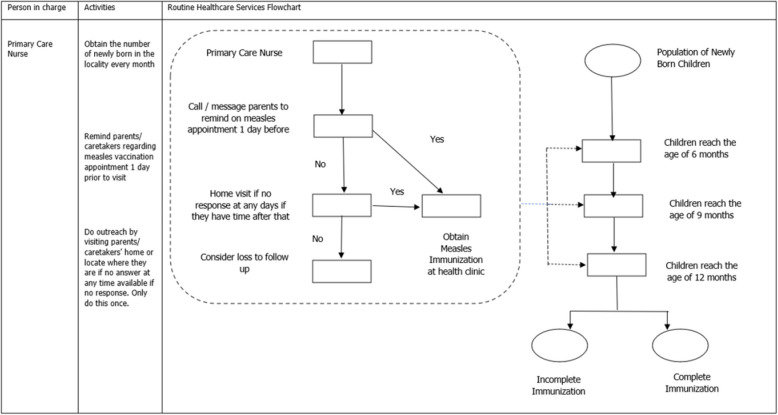

The control group continued to receive the available routine vaccination healthcare services at the health clinics (Fig. 2). The nurses reminded the participants of their vaccination at least one time prior to every vaccination appointment and made home visit if they did not response to the phone call reminders. However, these activities were dependent on the workload and available free time of the nurses, and so, many did not receive such care.

Fig. 2.

Routine healthcare services flowchart

Measles Intervention Involving Community Action (MIICA) programme planning and development

In the initial planning stage, advocacy visits were made and planning meetings were convened with the community leaders of every settlement, local politicians, and representatives of the Kota Kinabalu district health clinics to convince them to embrace and support the project. A qualitative study was conducted to understand the perspective of the community regarding the programme [30]. The barriers faced by the marginalised populations were acquired from a prior study and discussed. The community volunteers were recruited by the settlement’s committee and they were mobilised and trained to assist in the programme. A team comprising 10 community volunteers was created for each settlement. The training sessions for the community volunteers were planned and organised based on the input of the community leaders. During the sessions, the barriers faced by the community were presented as scenarios to the volunteers, and they discussed and provided solutions on how the participants could be assisted in obtaining their MCV.

Monitoring and follow-up

Supervisory support and monitoring visits were done by the principal researcher. As it was difficult to reach many of the settlements, the monitoring visits were limited but constant communication was maintained with the community volunteers throughout the study via WhatsApp. After each SMS reminder was conveyed to the participants, the volunteers updated them in their WhatsApp group. The volunteers also shared their successes and failures with those participants who needed home visits and assistance to obtain MCV at the health clinics. The principal researcher monitored and recorded the information updated in the WhatsApp group to ensure that every participant in the intervention group received the required intervention.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of children aged 12 months with complete MCV. The participants met the outcome definition when they received all three doses of the MCV. Those who missed any one of the vaccine doses were considered to have an incomplete vaccination. Data for the primary outcome came from the written vaccination records in the MCH booklets of the children, which were collected at the end of the 12-month follow-up. There were two copies of the MCH booklets, where one copy was kept by the parents or caretakers, while another copy was kept by the health clinics. The MCH booklet from the health clinics was chosen as the primary source document because it was a formal record of the vaccines received. Verbal reports of vaccination at the 12-month follow-up, in the absence of written documentation, were considered as not having received the MCV. Meanwhile, the secondary outcome was the parents’ or caretaker’s satisfaction with and acceptance of the intervention received. The outcome was measured using the translated and adapted Acceptability of Intervention Measure-Intervention Appropriateness Measure-Feasibility of Intervention Measure (AIM-IAM-FIM) Questionnaire and Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ- 8) at the end of the study.

Study tools

In this study, two instruments were used to measure the participants’ satisfaction with and acceptance of the intervention received by them. The Malay version of the CSQ- 8 consisted of eight items for measuring satisfaction with the intervention, where the total scores ranged from 8–32 [32], with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction. The translated and adapted version of the AIM-IAM-FIM was used to measure acceptance of the intervention [33]. It consisted of seven self-measured items, where Cronbach’s alpha was 0.938.

Sample size

Current statistics indicate an MCV coverage of approximately 70% at 12 months of age for children living in Kota Kinabalu. A target of 10% improvement in the vaccination status was set within the population based on another study with the implementation of SMS reminders [34]. An intra-cluster correlation (ICC) of 0.20 with 20 clusters per arm was considered for the cluster sampling [35]. The primary outcome would be binary, i.e., ‘yes’ or ‘no’ as to whether the community-based intervention improved the MCV status. Therefore, the formula for the standard parallel-group, two-armed design with binary outcomes was applied, giving a total of 470 participants that had to be enrolled in this study. Among the 10 settlements, five settlements with 235 participants received the community-based intervention, while another five settlements with 235 participants received routine healthcare services.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis used in this study was the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, which included all the participants from the randomised clusters who provided the follow-up data on the vaccination up to the age of 12 months. The categorical variables on the sociodemographic data were characterised using frequencies and percentages. The primary outcome, namely, the effectiveness of the community-based intervention in improving the status or completion of the MCV, was analysed using a multilevel logistic regression analysis, taking into account the correlation between the subjects within the same cluster. It was then adjusted to the individual sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. The findings were presented using the odds ratio with a confidence interval (CI) of 95% and statistical significance (p).

Meanwhile, for the secondary outcome, a descriptive study of the community's satisfaction with and acceptance of the intervention was performed using the mean. The scores were then classified according to percentiles (quartiles). In addition, the analysis for satisfaction was compared between the study arms using a multilevel linear regression analysis, taking into account the correlation between the subjects within the same cluster. It was then adjusted to the individual sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. The study utilised the control group as the reference group for all the analyses. The statistical significance, p, was established at 0.05, and IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 was used for the data analysis.

Results

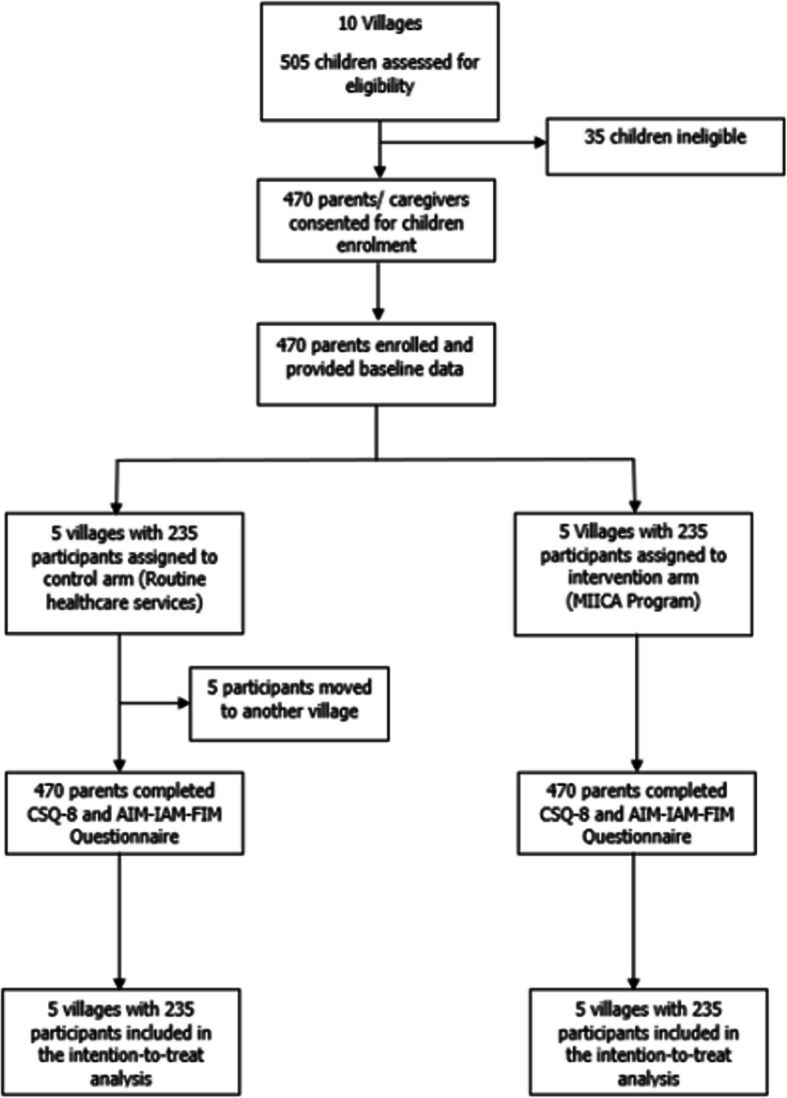

From October 2021 to March 2022, 470 children were enrolled together with their parents or caretakers from the 10 settlements of the marginalised population. A total of 505 children underwent eligibility assessments, of which 470 children from the 10 settlements met the established criteria, as can be seen from the trial profile (Fig. 3). A total of 35 children were deemed ineligible for the study as their parents had indicated that they would not be residing in the corresponding villages for a duration exceeding six months. All 470 children were duly registered to participate in the study after consent was obtained from their respective parents or caretakers, and all had proper documentation recorded in their MCH booklet.

Fig. 3.

The trial profile

The sociodemographic data of the participants are presented in Table 2. The participants within the two study arms who completed the study were balanced in terms of characteristics, except for their gender, mother’s employment status and time needed to travel to the healthcare facilities. A chi-squared test and, when appropriate, Fisher exact test, showed no statistical differences in the caretaker’s age, mother’s education level, type of healthcare facilities, and logistical issues with accessing nearby healthcare services between the two arms. Overall, both study groups were mainly female (79%), whose mothers had primary school-level education (53%), were unemployed (86%), went to public healthcare facilities to get vaccinated (98%), had no logistical issues with getting to the healthcare facilities (91%), and had no healthcare insurance (100%). The mean age for the caretakers in both study arms were 31 years old. Meanwhile, the time needed to go to the healthcare facilities varied according to the localities in the clustered areas. All those in the intervention arm clusters took 30 min or more to get to the nearest healthcare facility, while the mean time for the participants in the control arm were 11 min to reach their destination.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants for community-based intervention to improve measles vaccination completion in marginalised community settlements in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, from March 2022 to March 2023

| Characteristics | Intervention, n = 235 (%) | Control, n = 235 (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Age in years (Mean ± SD) | 1.97 ± 1.291 | 2.07 ± 1.209 | 0.397a |

| Caretaker’s age in years (Mean ± SD) | 31.27 ± 9.114 | 31.38 ± 5.694 | 0.440 a |

| Time needed to go to nearest healthcare facilities in minutes (Mean ± SD) | 30.00 ± 0.000 | 11.30 ± 2.197 | < 0.001a |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 25 (10.6) | 74 (31.5) | < 0.001* |

| Female | 210 (89.4) | 161 (68.5) | |

| Mother’s Education Level | |||

| No school | 16 (6.8) | 42 (17.9) | 0.002* |

| Primary school | 138 (58.7) | 111 (47.2) | |

| High school | 81 (34.5) | 82 (34.9) | |

| Mother’s Employment Status | |||

| Working | 10 (4.3) | 54 (23.0) | < 0.001* |

| Not working | 225 (95.7) | 181 (77.0) | |

| Type of healthcare facilities | |||

| Public | 227 (96.6) | 235 (100.0) | 0.007* |

| Private | 8 (3.4) | 0 | |

| Logistical issues | |||

| Yes | 25 (10.6) | 17 (7.2) | 0.196* |

| No | 210 (89.4) | 218 (92.8) | |

aDescriptive analysis

*Chi-square test of Independence

For the primary outcome, 189 (80.4%) participants in the intervention group completed the MCV, while 187 (79.6%) participants in the control group completed their MCV (Table 3). Furthermore, among those with incomplete MCV, the intervention group showed a higher percentage (17.0%) of children who completed at least two out of the three doses of measles vaccine, with a lower percentage of those who completed one dose (2.6%) and no dose at all compared to the control group. Between the two groups, the odds of completing the MCV were three times higher in the intervention group (95% CI: 0.176- 45.996) with adjusted odds ratio of 2.848, although the results were insignificant due to the wide interval and p value of 0.460 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Immunisation completion according to study group for community-based intervention to improve measles vaccination completion in marginalised community settlements in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, from March 2022 to March 2023

| Trial Arms | Immunisation Complete, % | Immunisation Incomplete, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 doses | 2 doses | 1 dose | 0 dose | |

| Intervention | 80.4 | 17.0 | 2.6 | 0.0 |

| Control | 79.6 | 14.5 | 4.3 | 1.7 |

Table 4.

Multilevel logistic regression analysis of community-based intervention association with measles immunisation completion (n = 470) for Community-based intervention to improve measles vaccination completion in marginalised community settlements in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, from March 2022 to March 2023

| Independent Variables | Odds Ratioa (95% CI) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| COR | aOR | ||

| Fixed effects | |||

| Trial Arm | |||

| Intervention | 1.055 (0.671, 1.660) | 2.848(0.176, 45.996) | 0.460 |

| Control (Ref) | - | - | - |

| Baseline Age | - | 1.072 (0.889, 1.292) | 0.468 |

| Caretaker’s age | - | 1.007 (0.976, 1.040) | 0.652 |

| Travel time to nearest clinic | - | 0.945 (0.816, 1.093) | 0.446 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | - | 0.916 (0.502, 1.670) | 0.774 |

| Female (Ref) | - | - | - |

| Mother’s Education Level | |||

| Secondary school | - | 1.198 (0.684, 2.457) | 0.622 |

| Primary school | - | 1.696 (0.845, 3.403) | 0.137 |

| No school (Ref) | - | - | - |

| Mother’s Employment Status | |||

| Working | - | 1.042 (0.512, 2.122) | 0.910 |

| Not working (Ref) | - | - | - |

| Logistical issues to access healthcare services | |||

| Yes | - | 1.025 (0.449, 2.338) | 0.953 |

| No (Ref) | - | - | - |

aOR adjusted Odds Ratio, Ref Reference

aMultilevel logistic regression analysis taking into account of cluster (villages that was randomised into trial arms) and adjusted to the sociodemographic characteristics: gender, baseline age, caretaker’s age, mother’s education level, mother’s employment status, travel time to the nearest clinic, and the logistical issues to access nearest healthcare facilities

Next, for the secondary outcome, the mean CSQ- 8 score of the intervention group was 28.988 while that of the control group was 23.212. Furthermore, the intervention group had a six-unit increase in satisfaction while holding as constant the sociodemographic characteristics of gender, baseline age, caretaker’s age, mother’s education level, mother’s employment status, travel time to the nearest clinic, and logistical issues with accessing the nearest healthcare facilities. The analysis revealed a statistically significant effect, with p < 0.001 and 95% CI: 2.634- 8.919 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multilevel linear regression analysis of the association between the community-based intervention with the satisfaction score (N = 470) for community-based intervention to improve measles vaccination completion in marginalised community settlements in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, from March 2022 to March 2023

| Independent Variables | Intervention effecta (95% CI) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted coefficient | Adjusted coefficient | ||

| Fixed effects | |||

| Trial Arm | |||

| Intervention | 2.282 (1.493,3.071) | 5.777 (2.634, 8.919) | < 0.001 |

| Control (Ref.) | - | - | - |

| Baseline Age | - | 0.117 (− 0.318, 0.083) | 0.251 |

| Caretaker’s age | - | 0.022 (− 0.013, 0.056) | 0.217 |

| Travel time to nearest clinic | - | 0.207 (− 0.371, − 0.043) | 0.014 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | - | 1.098 (− 1.759, − 0.437) | 0.774 |

| Female (Ref.) | - | - | - |

| Mother’s Education Level | |||

| Secondary school | - | 0.866 (0.022, 1.709) | 0.044 |

| Primary school | - | 1.125 (0.320, 1.929) | 0.006 |

| No school (Ref.) | - | - | - |

| Mother’s Employment Status | |||

| Not working (Ref.) | - | - | - |

| Logistical issues to access healthcare services | |||

| Yes | - | 0.799 (− 0.371, − 0.043) | 0.014 |

| No (Ref.) | - | - | - |

aMultilevel linear regression analysis taking into account of cluster (villages that was randomised into trial arms) and adjusted towards the sociodemographic characteristics: gender, baseline age, caretaker’s age, mother’s education level, mother’s employment status, travel time to the nearest clinic, and the logistical issues to access nearest healthcare facilities

Meanwhile, the mean AIM-IAM-FIM score was 50.6 (SD = 6.36,). The score was then classified according to the percentile (quartile), where 2.6% of the participants were classified as ‘unaccepting’ of the intervention they received, 48.9% were ‘mildly accepting,’ 23.4% were ‘accepting’, and 25.1% were ‘very accepting’ (Table 6).

Table 6.

Acceptability of intervention measure (AIM) for community-based intervention to improve measles vaccination completion in marginalised community settlements in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, from March 2022 to March 2023

| Percentile | Acceptability Score Range | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not acceptable | 3 | 0—36 | 2.6 |

| Mildly acceptable | 25 | 37—48 | 48.9 |

| Acceptable | 50 | 49—55 | 23.4 |

| Very acceptable | 75 | 56—60 | 25.1 |

Discussion

In the Western Pacific Region, Malaysia is one of the countries that is committed to eradicate measles and supports the Immunization Agenda 2021–2030. Measles is still a public health concern in this country despite the National Immunisation Programme (NIP) being in place, the MMR vaccine being available, as well as the implementation of successful surveillance programmes, strategic outbreak preparedness, and case management [5]. An effective community-based strategy especially involving the marginalised community could help to address the immunity gap that commonly occurred in Sabah, Malaysia in an equitable and sustainable way. Thus, the aim of this study was similar to that of other community-based health initiatives in Malaysia, which was to find a solution for an infectious disease issue. The MIICA programme was assessed across 10 villages that were inhabited by individuals from marginalised communities. The assessment of the program's outcomes was conducted. The results of the analyses demonstrate that there was a threefold increase in the probability of complete measles immunisation among individuals who participated in the community-based intervention. Although the statistical significance of this discovery is lacking, the adoption of the programme by the marginalised community offers a hopeful prospect for its future accomplishments provided that further enhancements are implemented. The individuals who received the intervention demonstrated significant satisfaction score outcomes.

In this study, the main issue was the low coverage of MCV among the marginalised population in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, which could lead to measles outbreaks. This was similar to the country’s Communication for Behavioural Impact (COMBI) programme, which was initiated based on the evidence of the high number of dengue cases reported among the community [36] and was aimed at reducing dengue outbreaks in the country [37]. However, very few studies used an RCT as their study design to evaluate the effectiveness of the programme [38–40]. After all, an RCT provides the best evidence of the effectiveness of a community-based intervention.

Furthermore, the intervention used a recall and reminder strategy that has been shown to have been successful in other low- and middle-income countries [22], and which can successfully boost vaccination rates [41]. This method can also directly affect behaviour without changing thoughts or feelings and has been proven to be excellent for vaccination uptake interventions [42]. A study was carried out using the computer-generated recall and reminder method, which was also found to be effective [43]. However, the application of this method may be challenging as extra expenses are required to install and maintain a separate reminder-recall system for use in health clinics.

Hence, at the end of the study, all the participants who were enrolled at the beginning were followed up and none were lost or became uncontactable. However, several variables showed significant differences in the baseline demographic characteristics, causing the intervention and control groups to become non-comparable. The variables included gender, the mother’s employment status, and the time needed to go to the nearest health facility. This was attributed to the location of the settlements, where those in the intervention group were on Gaya Island, which is five minutes from the city centre of Kota Kinabalu via speedboat, while the settlements of those who were in the control group were located on the mainland, within the city itself. Those living in the settlements also had distinctively different economic backgrounds, where the mothers in the control group were living in the city itself and many were working at the nearby shopping malls. Hence, to ensure an optimal comparison to determine the effectiveness of the community-based intervention, a multilevel logistic regression analysis was done to take into account the cluster design effect and to adjust to the individual sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in the study.

In addition, an insignificant increase in MCV completion was noted in the intervention group due to several factors. Firstly, the duration of this trial was limited to 12 months. Based on the routine vaccination schedule for children, the final MCV dose is given at the age of 12 months. So, the participants had to be recruited immediately after their birth and followed up for one year. More participants could have been recruited if there had been more time, and this could have increased the statistical power of the study to detect meaningful differences between the studied groups. Secondly, there may have been implementation issues, where the intervention might not have been implemented as intended. The turnover of community volunteers may have affected the consistent application of the intervention, thereby diluting the potential impact.

In contrast to the findings of this study, several other studies have reported different results, where it was found that community-based programmes are effective in attaining their intended goals, notably in the field of mother and child health initiatives [27, 44], and possess the capacity to significantly improve vaccination coverage in disadvantaged communities that have traditionally demonstrated inadequate levels of childhood vaccinations [45]. However, there have been studies that showed mixed outcomes, where some findings were insignificant [46–48]. One community-based study found that it was effective in ensuring that individuals received up-to-date vaccination for the first two doses only, while the subsequent doses showed a decline. This significant difference was attributed to the limited time of the study, thus confirming that a more extended follow-up period may be necessary to demonstrate improved rates of vaccination completion [49]. There was also a similar study that used the same strategy on a similar type of population, namely, low-income families, and produced similar results of more people having achieved up-to-date vaccination through the intervention that they received [50].

Nevertheless, the intervention group had a higher percentage of participants who received ≥ 2 doses of measles vaccine. The WHO recommends two MCV doses to help stimulate a more robust and long-lasting immune response in the majority of individuals to ensure optimal protection against the measles virus. Some people may not develop sufficient immunity after just one dose, but the second dose helps to fill this gap and provides better protection [8, 51]. Furthermore, having two MCV doses provides effective protection of around 92.5% for children vaccinated at ≥ 12 months [52]. Thus, the adoption of the programme by the marginalised community could offer a hopeful prospect for its future accomplishments. The intervention group was also satisfied with and accepted the programme, which is important, since having a programme that is highly appreciated and recognised by the community will cause it to be more successful [53].

Nevertheless, this study had its limitations. Firstly, the recruited marginalised population sample was not representative of the nation since their sociodemographic factors differed from those of other marginalised populations in different states and countries. Hence, the findings of this study cannot be generalised as it was carried out on a specific type of population. The turnover of community volunteers, at least one person every 2–3 months, could also have affected the implementation of the proposed intervention and impacted the outcome. Finally, there were changes in the exemption of charges for hexavalent vaccines, where some parents brought their children for the vaccination appointment at the health clinic, but skipped the MCV and only took the hexavalent vaccine instead. This affected the completion of the three MCV doses as fewer people took the final dose for immunisation.

Hence, to improve the community-based intervention programme, a similar intervention design can be implemented, with larger funds, a longer duration of study, and a bigger sample size. Future initiatives must also offer effective interventions and a wider reach to accomplish better improvements in MCV completion. As such, future studies could compare alternatives such as deploying trained workers to administer vaccines on-site and active case-finding for defaulters to complete vaccination schedules. The trained workers could be from the non-governmental organisations (NGOs), like the Red Crescent Society or the Malaysian Medical Relief Society (MERCY), to assist and act as the go-between to assist in communications between the marginalised community and healthcare providers. The community is a known key stakeholder in assisting in healthcare services in various countries, especially among marginalised people. Thus, it is worthwhile to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in improving children’s vaccinations with the involvement of the community compared to routine healthcare services. Furthermore, added resources from the community could also assist those with financial difficulties in getting vaccines. Future studies could then explore the challenges and motivations of community volunteers. Remuneration for community volunteers should also be considered to compensate them for their help and sacrifices to their community. Finally, further evaluation is needed to assess not only the effectiveness but on how to enhance adherence and acceptance of the interventions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this cluster RCT demonstrated the potential effectiveness of a community-based intervention through the involvement of community volunteers, who reminded parents of their children’s MCV appointments. Although the intervention did not have a significant impact, more people were able to get two doses or more of the measles vaccine to ensure a long-lasting immune response, thus reducing the likelihood of measles outbreaks and maintaining herd immunity. The participants were also significantly satisfied with and accepted the intervention, which suggested that engaging the involvement of the community in vaccination activities could ensure the sustainability of the programme, especially among the marginalised population. After all, community-based interventions that are tailored to the unique challenges and needs of a community help to address the specific needs of the community, promote equitable health, and encourage the engagement and ownership of the community.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Director-General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article. The authors would also like to express our gratitude to the Sabah State Health Department, particularly the Kota Kinabalu District Health Office.

Authors’ contributions

H.S. and R.A. conceptualized and designed the study. H.S. did the data collection and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. H.S., R.A., and H.A.K., did data interpretation, and contributed to data analysis. All authors reviewed, edited the manuscript, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study paper was written, edited, and published without outside funding.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study is obtained from the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (NMRR ID- 22–00051 - 88 T (IIR)) Ministry of Health, Malaysia as well as the ethical committee of University Malaysia Sabah (JKEtika 1/22 (2)). Every participant gave their written authorization after being informed of the study’s objectives and any potential negative side effects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. Measles. World Health Organization. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles#:~:text=During2000–2021%2Csupportedby,RegionandGavi-supportedcountries.

- 2.Fernald LCH, Gertler PJ, Neufeld LM. Role of cash in conditional cash transfer programmes for child health, growth, and development: an analysis of Mexico’s Oportunidades. Lancet (London, England). 2008;371:828–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Communities vulnerable without immunization against infectious diseases. UNICEF. 2020. https://www.unicef.org/malaysia/press-releases/communities-vulnerable-without-immunization-against-infectious-diseases.

- 4.Gupta PC, Satapathy P, Gupta A, Sah R, Padhi BK. The fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic: missed measles shots? - correspondence. Ann Med Surg. 2023;85:561–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mat Daud MRH, Yaacob NA, Ibrahim MI, Wan Muhammad WAR. Five-Year Trend of Measles and Its Associated Factors in Pahang, Malaysia: A Population-Based Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):8017. 10.3390/ijerph19138017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Mansour Z, Arab Id J, Said Id R, Rady A, Hamadeh R, Gerbaka B, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the utilization of routine immunization services in Lebanon. 2021. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.da Silva TMR, de Sá ACMGN, Vieira EWR, Prates EJS, Beinner MA, Matozinhos FP. Number of doses of Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine applied in Brazil before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.WHO. Measles Vaccine Coverage. 2023. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/coverage/MCV.html?CODE=MYS&ANTIGEN=&YEAR=.

- 9.States M, Preuve T, Advi- WHOS, Grade T, Sage T. Measles vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2017. Relev Epidemiol Hebd. 2017;92:205–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Express D. Foreigners make up one-third. Daily Express. 2018. https://www.dailyexpress.com.my/news.cfm?NewsID=127532.

- 11.World Health Organization - WHO. Fourth Biregional Cross-border Meeting on Polio, Measles, Rubella and other vaccines preventable diseases. Who Meet Reports. 2019;46 SUPPL. 1.

- 12.Azhar SS, Nirmal K, Nazarudin S, Rohaizat H, Noor AA, Rozita H. Factors influencing childhood immunization defaulters in sabah, malaysia. Int Med J Malaysia. 2012;11:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S. Vaccination outreach programme arrives in hard-to-reach Sabah communities. In: The Star News. 2022. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2022/12/07/vaccination-outreach-programme-arrives-in-hard-to-reach-sabah-communities. Accessed 9 April 2025.

- 14.Chan J. Sabah on alert for measles after Philippine crisis but says matters in hand. Malay Mail News. 2019. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2019/02/14/sabah-on-alert-for-measles-after-philippine-crisis-but-says-matters-in-hand/1722925. Accessed on 9 April 2025.

- 15.Thanaraju VP and A. Fourth Polio Case Hits Malaysia, Unvaccinated Foreign Sandakan Boy. Code Blue. 2020. https://codeblue.galencentre.org/2020/03/10/fourth-polio-case-hits-malaysia-unvaccinated-foreign-sandakan-boy/.

- 16.WHO. Measles outbreaks strategic response plan 2021–2023. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240018600.

- 17.Omoleke SA, Getachew B, Igoh CS, Yusuf TA, Lukman SA, Loveday N. The Potential Contribution of Supplementary Immunization Activities to Routine Immunization in Kebbi State. Nigeria J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720932698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raganathini Vethasalam FZ, RM. Parents urged to get children vaccinated. The Star News. 2023. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2023/03/04/parents-urged-to-get-children-vaccinated. Accessed 9 April 2025.

- 19.Raganathini Vethasalam FZ, RM. More than 700 kids identified for boosters. The Star News. 2023. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2023/03/04/more-than-700-kids-identified-for-boosters. Accessed 9 April 2025.

- 20.Crocker-Buque T, Mindra G, Duncan R, Mounier-Jack S. Immunization, urbanization and slums - A systematic review of factors and interventions. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petridou ET, Antonopoulos CN. Injury Epidemiology. Second Edi: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey H, Reissland N, Mason J. Parental reminder, recall and educational interventions to improve early childhood immunisation uptake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2015;33:2862–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brugha RF, Kevany JP. Maximizing immunization coverage through home visits: A controlled trial in an urban area of Ghana. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:517–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes K, Friedman SM, Namerow PB, Honig J. Impact of community volunteers on immunization rates of children younger than 2 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuang Kuay L, Ismail H, Liana Ab Majid N, Arasu Saminathan T, Ramly R, Ying Ying C, et al. Factors Associated with Non-Participation in a Health Screening Programme and its Barriers: Findings from the Community Empowers the Nation Programme (KOSPEN), Malaysia 2016. Int J Public Heal Res. 2020;10:1166–73.

- 26.Hod R, et al. The COMBI Approach in Managing Dengue Cases in an Urban. 2013;3:347–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, Haws RA. Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: A review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115:519–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardoel ZE, Reijneveld SA, Postma MJ, Lensink R, Koot JAR, Swe KH, et al. A Guideline for Contextual Adaptation of Community-Based Health Interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholson A, Minicucci C, Liao J, National Academies of Sciences and Medicine E. A Systems Approach to Increasing Vaccine Confidence and Uptake: Opportunities for Community-Based Strategies. In: The Critical Public Health Value of Vaccines: Tackling Issues of Access and Hesitancy: Proceedings of a Workshop. National Academies Press (US); 2021.

- 30.Salleh H, Avoi R, Abdul Karim H, Osman S, Dhanaraj P, Ab Rahman MA. A Behavioural-Theory-Based Qualitative Study of the Beliefs and Perceptions of Marginalised Populations towards Community Volunteering to Increase Measles Immunisation Coverage in Sabah, Malaysia. Vaccines. 2023;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328:702–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale, Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2:197–207. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Salleh H, Avoi R, Karim HA, Osman S, Kaur N, Dhanaraj P. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation to Malay, and psychometric evaluation of the AIM-IAM-FIM questionnaire: Measuring the implementation outcome of a community-based intervention programme. PLoS One. 2023;18 11 November:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Bangure D, Chirundu D, Gombe N, Marufu T, Mandozana G, Tshimanga M, et al. Effectiveness of short message services reminder on childhood immunization programme in Kadoma, Zimbabwe - A randomized controlled trial, 2013. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu LY, Zook K, Gingold JA, Gillespie CW, Briccetti C, Cora-Bramble D, et al. Strategies for Improving Vaccine Delivery: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6). 10.1542/peds.2015-4603. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Aris T. Prolonged dengue outbreak at a high-rise apartment in Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia: A case study. Trop Biomed. 2019;36:550–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ministry of Health M. COMBI. 2023. https://idengue.mysa.gov.my/ide_v3/combi.html.

- 38.Kuay LK. Technical Report Evaluation fo Effectiveness of Implementation of "Lomuniti Sihat Perkasa Negara" (KOSPEN) Programme in Malaysia- Phase 1, 2016. https://iku.nih.gov.my/images/teknikal-report/kospen-p1.pdf.

- 39.Sondaram NK, Manaf RA. Factors Associated with Knowledge of Healthy Community, Empowers Nation (KOSPEN) and its Implementation among Community Health Volunteers in Kulim District, 2017. Malaysian J Med Heal Sci. 2018;14(2).

- 40.Kuay LK, Azlan Kassim MS, Ismail H, Harith AA, Ying CY, Abdullah Z. Methodology of the Evaluation of “Komuniti Sihat Pembina Negara-Plus”(KOSPEN Plus) Programme among Workers in Malaysia (Phase 1). Budapest Int Res Exact Sci J. 2021;3:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cataldi JR, Kerns ME, O’Leary ST. Evidence-based strategies to increase vaccination uptake: A review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32:151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brewer NT. What Works to Increase Vaccination Uptake. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:S9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dini EF, Linkins RW, Sigafoos J. The impact of computer-generated messages on childhood immunization coverage. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maldonado LY, Bone J, Scanlon ML, Anusu G, Chelagat S, Jumah A, et al. Improving maternal, newborn and child health outcomes through a community-based women’s health education program: A cluster randomised controlled trial in western Kenya. BMJ Glob Heal. 2020;5(12):e003370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Sengupta P, Benjamin AI, Myles PR, Babu BV. Evaluation of a community-based intervention to improve routine childhood vaccination uptake among migrants in urban slums of Ludhiana, India. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2017;39:805–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mussa EC, Palermo T, Angeles G, Kibur M, Otchere F. Impact of community-based health insurance on health services utilisation among vulnerable households in Amhara region. Ethiopia BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gago C, Aftosmes-Tobio A, Beckerman-Hsu JP, Oddleifson C, Garcia EA, Lansburg K, et al. Evaluation of a cluster-randomized controlled trial: Communities for Healthy Living, family-centered obesity prevention program for Head Start parents and children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2023;20:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoong JM, Koh HA, Wong K, Lee HH. Effects of a community-based chronic disease self-management programme on chronic disease patients in Singapore. Chronic Illn. 2023;19:434–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg Z, Sally Findley SM. Community-based Strategies for Immunizaing ‘Hard-To-Reach’ Child: The New York State Immunization and Health Care Initiative. Am J Prev Med. 1995;11(3):14–20. [PubMed]

- 50.Vivier PM, Alario AJ, O’Haire C, Dansereau LM, Jakum EB, Peter G. The impact of outreach efforts in reaching underimmunized children in a Medicaid managed care practice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:1243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LeBaron CW, Beeler J, Sullivan BJ, Forghani B, Bi D, Beck C, et al. Persistence of measles antibodies after 2 doses of measles vaccine in a postelimination environment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uzicanin A, Zimmerman L. Field effectiveness of live attenuated measles-containing vaccines: a review of published literature. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl):S133–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gebretsadik A, Melaku N, Haji Y. Community acceptance and utilization of maternal and community-based neonatal care services provided by health extension workers in rural sidama zone: barriers and enablers: a qualitative study. Pediatr Heal Med Ther. 2020;11:203–17. 10.2147/PHMT.S254409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript.