Abstract

Antigen-specific T-cell responses may be described by combining three categories: (i) the specificity and effector functions of a T-cell population, (ii) the quantity of T-cell responses (i.e., the number of responding T cells within the CD4/CD8 population), and (iii) the “quality” of T cells (defined by the T-cell receptor [TCR] structure). Several methods to measure T-cell responses are now available including evaluation of T-cell precursors using limiting dilution, the enzyme-linked immunospot assay, ex vivo TCR variable (v)-segment analysis determined by flow cytometry, and TCR-CDR3 length analysis (spectratyping), as well as identification of peptide-specific T cells using major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I tetramers containing appropriate peptides. Until now, only a limited set of MHC-peptide complexes have been available as tetramer complexes. We demonstrate that CD8+ or CD4+ T cells in patients with cancer can be molecularly defined using a combination of spectratyping (TCR structure and “molecular composition”) plus the implementation of an antibody panel directed against 21 individual VB TCR chains (“quantity” of T-cell families). This approach is instrumental in defining and comparing the magnitudes of CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell responses over time in individual patients, in comparing the TCR VA and VB repertoire in different anatomic compartments, and in comparing the TCR VA-VB diversity with that in normal healthy controls. This method provides the means of objectively defining and comparing the TCR repertoire in patients undergoing vaccination protocols and underlines the necessity to calibrate the TCR-CDR3 analysis with a qualitative assessment of individual TCR VB families.

A wide variety of tumors in human malignancies can be characterized by expression of different tumor-associated antigens (TAA) (reviewed in references 22 and 26). These TAA epitopes are ligands for T-cell receptors clonally expressed in T lymphocytes. The presentation of TAA-derived peptides to T cells and the induction of TAA-specific T-cell responses is prerequisite for immunologic recognition and T-cell-mediated tumor cell destruction. Recent progress in immunologic approaches resulted in the characterization and development of a number of new epitopes, which can be utilized in immunotherapy, e.g., as components of antitumor vaccines. These epitopes may be provided by the wild-type TAA or they may represent altered ligands that are able to stimulate T cells which have not yet responded to the wild-type epitope but are able to cross-react to the naturally processed and presented peptides displayed by tumor cells (2, 15, 27, 33, 34). Clinical monitoring of TAA-specific T-cell responses in cancer patients prior to, during, and after the administration of anticancer vaccines is necessary for each immunotherapy session to monitor the effectiveness and to be able to devise strategies for improvement of anticancer vaccines. Recent reports emphasized that vaccine adjuvants, e.g., cytokines, critically impact on vaccine efficacy. These reagents may also affect the T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire reacting to the nominal target epitope (13, 19, 20), e.g., by affecting homing factors or by redistributing the T-cell pool. Thus, evaluation of the entire TCR repertoire may be critical to gauge immunomodulatory effects induced by the antigen and the respective adjuvant component of the vaccine.

Several methods to measure T-cell responses are now available, including evaluation of T-cell precursors using limiting dilution, the enzyme-linked immunospot assay, ex vivo TCR variable-segment analysis determined by flow cytometry, and TCR-CDR3 length analysis (spectratyping), as well as identification of peptide-specific T cells using major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I tetramers containing appropriate peptides (reviewed in reference 3). We demonstrate that CD8+ or CD4+ T cells in patients with cancer can be molecularly defined using a combination of spectratyping (TCR structure and molecular composition) plus the implementation of a comprehensive antibody panel directed against individual variable beta chain (VB) TCR (“quantity” of T-cell families). This approach is instrumental in defining and comparing the magnitudes of CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell responses and in detecting alterations in the TCR repertoire. This information may aid the enumeration of antigen-specific T cells using tetramer reagents to define whether a peptide-specific T-cell response is polyclonal, monoclonal, or dominated by a few TCR clonotypes. The ultimate goal of biologically and clinically relevant immunomonitoring is to address the detection of antigen-specific T cells and their functional activity (e.g., as determined by using intracellular cytokines).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

Tumor samples were isolated after surgery from two patients (designated as individuals 1 and 2) with advanced cervical cancer, snap-frozen for later use (in TCR-CDR3 analysis or immunohistochemistry), and stored in liquid nitrogen. The tumor from individual 1 (HLA-A26, A33, B14, B38, Cw7, Cw8, DR3, DR4, DQ2, DQ3) tested positive for human papillomavirus type 33 (HPV-33), and tumor tissue from individual 2 (HLA-A1, A11, B7, B55, Cw3, Cw7, DR1, DR15, DQ5) tested positive for HPV-16. Tumor and blood samples were obtained after gaining informed consent from the patients and after gaining approval from the local ethics committee [document reference 837.327.99 (2272)]. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were generated by culturing small tumor pieces in 48-well plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) in AIM-V medium (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands) supplemented with 100 IU of interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Chiron, Ratingen, Germany) per ml and 100 ng of IL-7 (provided by A. Minty, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Labege, France) per ml. TIL grew out from tumor pieces after 1 to 2 days of in vitro culture and were expanded in medium containing IL-2 and IL-7 without restimulation with tumor cells. TIL were analyzed for TCR composition after 4 days of in vitro culture. Alternatively, TIL were freshly isolated, harvested, and stored in liquid nitrogen as described previously (31). TIL and peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL), obtained by venipuncture and treated with Ficoll, were segregated into CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations using immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

Determination of the TCR repertoire by DNA fragment analysis.

Aliquots of cDNA (obtained from 106 cells) corresponding to 50 ng of total RNA were amplified in 20-μl reaction mixtures with 29 individual primers specific for the variable TCR alpha chain and with 24 individual primers specific for the TCR beta chain as described previously (8, 25). Aliquots (2 μl) of the 24 unlabeled VB and the 29 VA amplicons were further subjected to three to six cycles of a runoff reaction using a fluorophore-labeled TCR C-alpha chain-specific primer (5′-ATACACATCAGAATCCTTACTTTG) or C-beta chain-specific primer (5′-GTGCACCTCCTTCCCATTCACC). Labeled products were analyzed by DNA fragment analysis using a 310 DNA sequencer and Genescan software (ABI, Weiterstadt, Germany). Single peaks in individual TCR variable-chain families, suggesting clonality, were further analyzed by direct sequencing of the PCR products using the primer (5′-3′) GTCACTGGATTTAGAGAGTCT for the TCR alpha chain and the primer CACAGCGACCTCGGGTGGG for the variable TCR beta chain on a 310A DNA sequencer (ABI). Single peaks obtained by DNA fragment analysis may indicate a monoclonal TCR transcript or, alternatively, different TCRs with an identical TCR CDR3 length but with different nucleotide sequences (11). TCR transcripts are termed oligoclonal if one or two peaks are detected in the CDR length analysis and/or several individual TCR transcripts are present within a single peak; they are termed monoclonal if direct sequencing of the PCR product or all individual clones after subcloning of the respective PCR amplicon reveals a single TCR transcript.

Determination of VB families by flow cytometry.

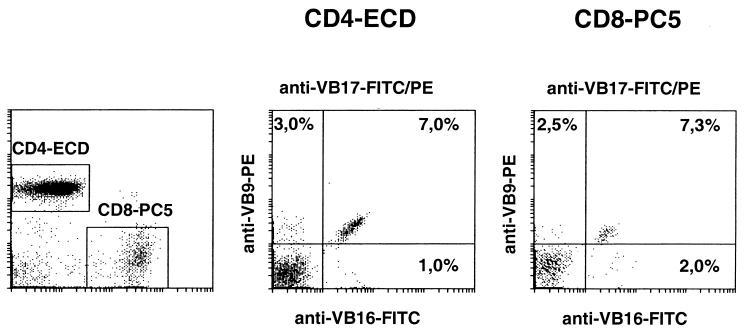

All reagents are from Beckman/Coulter, Krefeld, Germany. Detection of individual VB families was carried out in TIL or in freshly harvested PBL as described previously (12). A total of 2 × 105 cells were stained simultaneously with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) directed against CD4 (energy-coupled dye) and CD8 (R-phycoerythrin-cyanin 5 [PC5]) and a set of three antibodies directed against TCR-VB families as listed in Table 1. MAbs directed against TCR families were labeled with either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE), and the third anti-TCR directed MAb was labeled with PE and FITC. Flow cytometry was performed using a Coulter Epics XL instrument and XL-System II software version 2.1. Cells were gated either on the CD4+ or on the CD8+ population, and individual TCR families were evaluated based on T cells showing exclusive staining for either FITC or PE or double staining for both FITC and PE. Thus, 21 individual TCR VB families can be analyzed in seven individual tubes (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Reagent compositiona

| VB Family | Fluorochrome | Clone | Isotype (species) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VB 5.3 | PE | 3D11 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 7.1 | PE + FITC | ZOE | IgG2a (mouse) |

| VB 3 | FITC | CH92 | IgM (mouse) |

| VB 9 | PE | FIN9 | IgG2a (mouse) |

| VB 17 | PE + FITC | E17.5F3 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 16 | FITC | TAMAYA1.2 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 18 | PE | BA62.6 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 5.1 | PE + FITC | IMMU157 | IgG2a (mouse) |

| VB 20 | FITC | ELL1.4 | IgG (mouse) |

| VB 13.1 | PE | IMMU222 | IgG2b (mouse) |

| VB 13.6 | PE + FITC | JU74.3 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 8 | FITC | 56C5.2 | IgG2a (mouse) |

| VB 5.2 | PE | 36213 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 2 | PE + FITC | MPB2D5 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 12 | FITC | VER2.32 | IgG2a (mouse) |

| VB 23 | PE | AF23 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 1 | PE + FITC | BL37.2 | IgG1 (rat) |

| VB 21.3 | FITC | IG125 | IgG2a (mouse) |

| VB 11 | PE | C21 | IgG2a (mouse) |

| VB 22 | PE + FITC | IMMU546 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 14 | FITC | CAS1.1.3 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 13.2 | PE | H132 | IgG1 (mouse) |

| VB 4 | PE + FITC | WJF24 | IgM (rat) |

| VB 7.2 | FITC | ZIZOU4 | IgG2a (mouse) |

T cells were gated either on CD4+ T cells, using the MAb SFCI12TD11 (T4) labeled with ECD, or on CD8+ T-cells, using the MAb clone B9.11 coupled to PC5. A total of 21 individual VB-families can be evaluated using seven individual test tubes. This panel has been extended by three additional MAbs (the bottom three).

FIG. 1.

Flow-cytometric determination of three individual TCR VB chains in CD4+ or CD8+ PBL within a single test tube. PBL were gated on either CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells, and the relative frequency of VB16+ T cells (FITC), VB9+ T cells (PE), or CD8+ T-cell population was determined.

RESULTS

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the TCR repertoire.

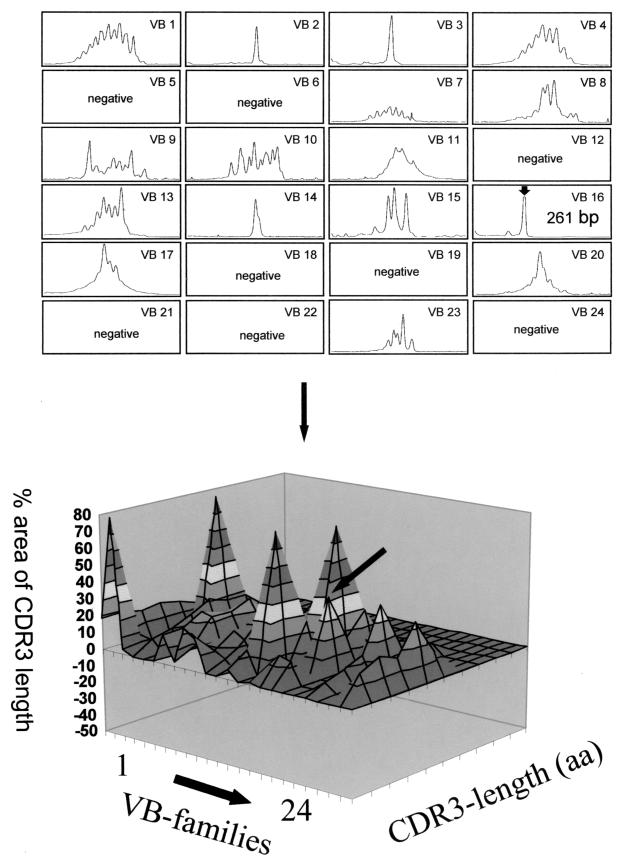

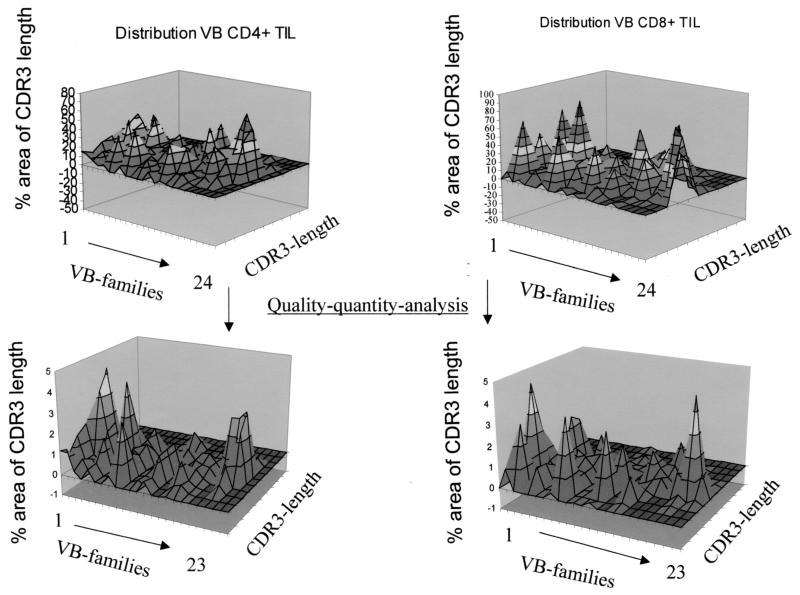

Each individual TCR variable CDR3 profile obtained from 29 TCR VA or 24 TCR VB families can be depicted as a function of the CDR3 length: each peak represents 3 bp coding for one amino acid (aa) residue. In general, 9 or 10 aa can be identified in each CDR3 profile. The area of the entire CDR3 analysis is estimated as 100% for each TCR VA or VB family, and the area under the curve for each individual CDR3 peak is expressed as the percentage of the entire CDR3 area. In normal healthy subjects, the CDR3 peak pattern represents a Gaussian distribution (9, 24). This CDR3 pattern may be depicted two-dimensionally, i.e., one picture for each TCR VA/VB family; alternatively, the entire TCR VA and VB repertoire may be combined in a single complex figure, thus creating a TCR VA or TCR VB “landscape” as a function of CDR3 length (as defined by the number of encoded amino acids) and the area under the curve for each individual CDR3 peak. For the sake of clarity, each 10% of the CDR3 peak is depicted in a different shade (Fig. 2). Of note, this analysis reflects the structural composition of the TCR repertoire but does not provide information pertaining to the quantity of each TCR VA plus VB family, since the PCR-based amplification is not quantitative. There are several possible ways to quantify of TCR families: (i) standardization for the constant (C) TCR CA or CB chain using a competitive PCR approach either at the RNA or at the cDNA level using competitor plasmids; (ii) a similar approach for each TCR VA or VB family; or (iii) monitoring of the amplification using Taq-man technology. These methods can be used in tissue sections or in CD4- and CD8-sorted PBL, but they are expensive and time-consuming. A different alternative, at least for PBL or TIL, is the use of flow cytometry to measure the frequency of individual VB families in T-cell subsets. This approach is useful only for TCR VB chains due to the small number of commercially available anti-human TCR VA MAbs. The flow cytometry-based approach results in the frequency of individual VB families within each CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell subset (i.e., the percentage of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells). This number can now be used to correct the CDR3 length analysis by using the individual VB family frequency; e.g. if only a single CDR3 peak occurs, it will be depicted as the percentage of VB staining cells within the CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell population, whereas if several CDR3 peaks are present, the frequency of an individual VB family is segregated into several peaks according to the area under the curve for each peak, since the entire CDR3 area represents 100% of a given VB family (Fig. 3). The 21 VB antibodies cover up to 80% of the VB repertoire. This panel has recently been expanded by using three additional MAbs covering VB13.2, VB4, and VB7.2, which enhances the coverage of the TCR VB repertoire (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Two-dimensional (top) and three-dimensional (bottom) picture of the TCR repertoire analysis as defined by TCR VB spectratyping in a CD4+ TIL line from a patient with cervical cancer. The two-dimensional picture allows us to analyze each VB family, and the landscape picture represents an overview of the TCR diversity. The single TCR VB16 chain (marked with the arrow) was found to be monoclonal and to recognize autologous tumor cells (10). aa, amino acids.

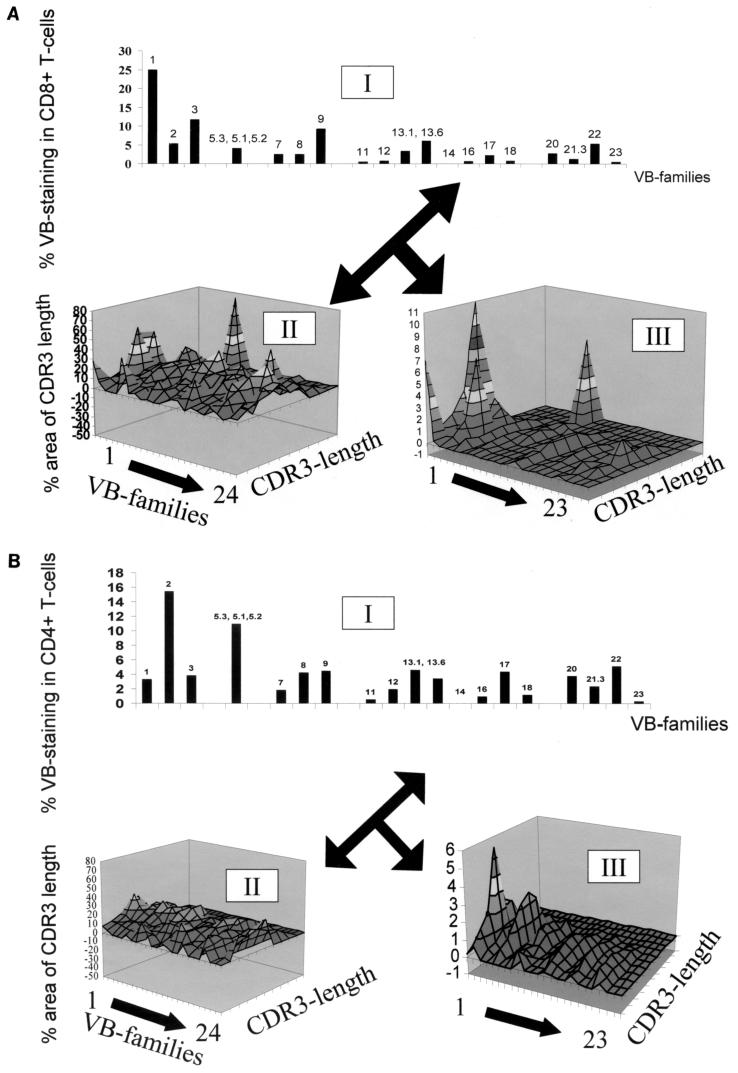

FIG. 3.

Qualitative and quantitative assessment of TIL. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were separated using immunomagnetic beads, and a TCR-VB-CDR3 analysis was performed for each T-cell subset (top). This landscape picture can be corrected by using the TCR VB frequencies of individual VB families as defined by flow cytometry. Note the difference between the “quality” and the “quality-quantity” analysis (bottom). The T cells were freshly harvested TIL from patient 2.

Differences in TCR VA and VB repertoires.

Individual TCR VA or VB repertoires may be depicted as a landscape analysis as a function of the CDR3 length (z axis), the VB family (x axis), and the percentage of each individual CDR3 in a distinct VA or VB family (y axis). This allows us to describe the TCR repertoire only at the time of evaluation. To compare either longitudinal differences (i.e., in PBL or tissue samples collected at different time points) or spatial differences (i.e., differences between a tumor sample and PBL or individual lymph node sections), the CDR3 distribution pattern of individual VA or VB families can be used as a control for other samples. This control sample can be obtained from an individual patient (i.e., pre- and postimmunization, tumor and normal tissue) or can be a representative Gaussian distributed sample from either CD4+ or CD8+ PBL from healthy blood donors (9, 24). The difference at each CDR3 peak (for each VA or VB family) is calculated by comparing the area under the curve in the test sample with that in the control sample. Three possibilities can occur: (i) the pattern is identical (a flat or smooth area of the TCR landscape occurs), (ii) some peaks are enhanced (resulting in overrepresentation of certain CDR3 peaks, which yields positive signals as a positive percent perturbation [y axis]), and (iii) some peaks are diminished or ablated (resulting in underrepresentation of CDR3 peaks, depicted as a negative percent perturbation [y axis]). For the sake of clarity, each 10% of over- or underrepresentation of the TCR CDR3 area (i.e., comparison of two samples) is depicted in a different shade. This comparison allows a detailed description and comparison of the entire VA and VB repertoire. However, if the frequency of individual VB families is also available, this information can also be used in the comparison of the TCR VB chains, which in this case would include the comparative analysis of the quality (CDR3 length) and quantity (frequency) of the TCR repertoire.

Combination of TCR VB CDR3 analysis with determination of the TCR VB frequency reflects a realistic picture of the TCR repertoire.

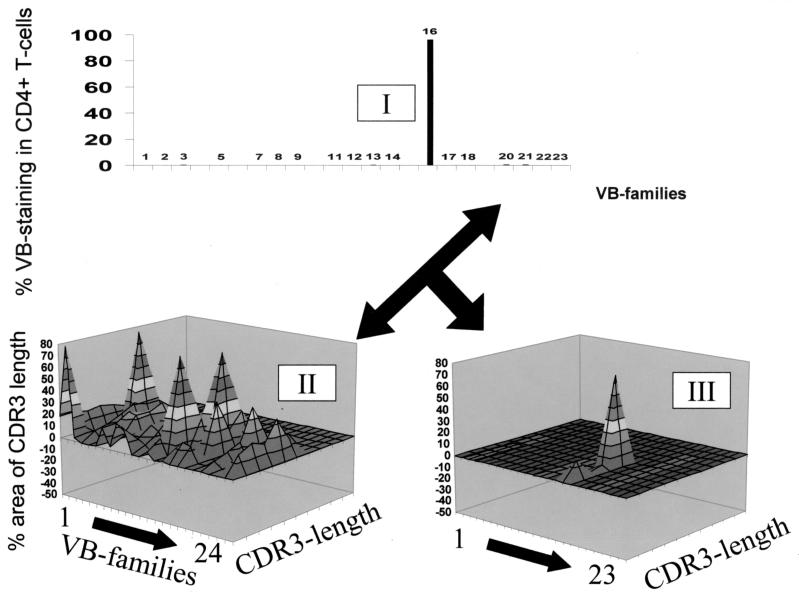

CDR3 analysis, i.e., the structural definition of a T-cell population, combined with a quantitative assessment of the T-cell population as defined by flow cytometry gives a more detailed description of a T-cell population. For instance, the majority of TIL from patient 1 stained positive for CD4. However, the TCR VB landscape (Fig. 2) suggests a rather oligoclonal or polyclonal nature of this T-cell population, but it does not provide any quantitative information pertaining to the frequency of individual VB families. Only if data obtained by flow cytometry are combined with the CDR3-spectratyping results does the real picture emerge: almost the entire CD4+ T-cell population of this TIL line stains positive for TCR VB16 (Fig. 4), which has been previously reported to be monoclonal and to define a peptide in the context of HLA-DR4 provided by HPV33-E7 (10). A similar picture emerges if PBL obtained from the same patient are analyzed for individual VB expression after gating on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. This TCR VB frequency allows us to correct the TCR CDR3 landscape analysis, which leads to a more realistic reflection of the TCR repertoire as defined by the TCR diversity and TCR frequency (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Combination of TCR quality and quantity. CD4+ TIL from patient 1 (Fig. 2) were stained for 21 individual VB families (I). This information, combined with the CDR3 analysis (II), yields the realistic picture that up to 70% of this CD4 T-cell line stain VB16-positive (III).

FIG. 5.

TCR quality and quantity in CD4+ (A) or CD8+ (B) PBL from patient #1. Flow-cytometric analysis (I) with CDR3 spectratyping (II) reflects a comprehensive ex vivo analysis of PBL (III). Note that the frequency of individual VB families (e.g., VB1 in CD8+ PBL [panel A, II]) corrects the entire area under the curve of the oligoclonal TCR VB1 family. Thus, the major CDR3 peak yields 11% of the CD8+ VB1+ population. In the case of a single, monoclonal peak, the VB1+ population would yield 25% of this VB family, as indicated in panel I.

Comparison of TCR repertoires.

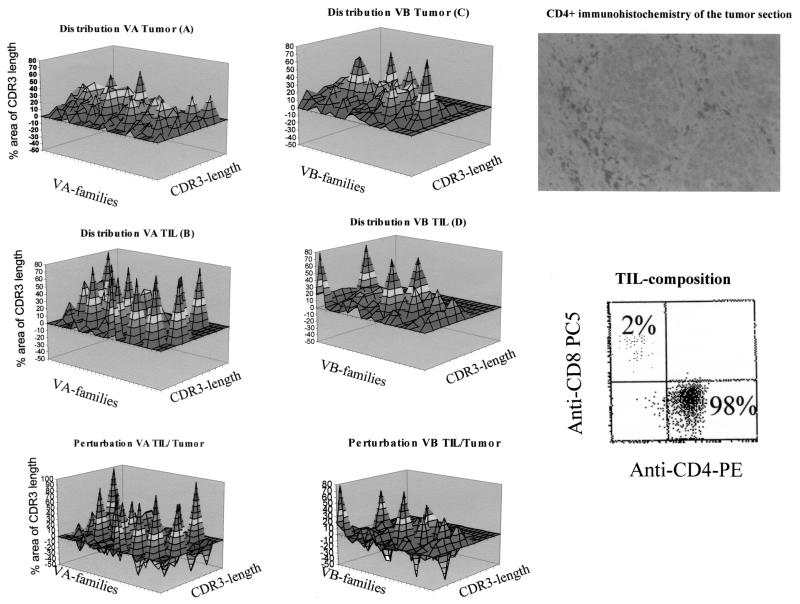

To compare the diversity of T-cell infiltrates in different anatomic compartments, we took advantage of the (snap-frozen) tumor sample from patient 1, which exhibits a dominant CD4+ T-cell infiltrate (Fig. 6). Thus, it may be compared to the CD4+ TIL population. Both samples, tumor or TIL, exhibited a diverse TCR VA (Fig. 6A and B) and VB (Fig. 6C and D) repertoire. Subtraction of each TCR VA or VB CDR3 peak present in TIL from the TCR landscape obtained in the tumor sample shows that the short-term (4-day)-expanded TIL population exhibits a qualitatively different TCR VA or VB repertoire from the CD4+ T cells residing in the tumor sample. This reflects a qualitative difference, since we did not measure the quantity of each VB family in the tumor specimen or in TIL. However, based on the flow cytometry data (Fig. 4), we know that the vast majority of CD4+ TIL are VB16 positive. Therefore, a quantitative comparison would be advantageous. This could potentially be performed by a molecular semiquantitative analysis, based on the assumption that the amounts of individual TCR mRNA transcripts do indeed reflect TCR protein expression, independent of the activation status of the T cell.

FIG. 6.

Comparative analysis of the TCR VA/VB repertoire in TIL and tumor tissue from patient 1. The polyclonal TCR VA repertoire in the CD4+ tumor specimen (A) and the oligoclonal TCR VA landscape in CD4+ TIL (B) are shown. TCR VB analysis exhibited a restricted TCR VB pattern both in tumor tissue (C) and in TIL (D). Note that this analysis depicts only the TCR diversity and does not address the quantitative aspect of individual TCR families. The TCR CDR3 patterns can now be subtracted; i.e., each area under the CDR3 peak of the tumor specimen is compared to the respective CDR3 peak areas of each individual TCR VA-VB family. This results in an over- or underrepresentation of individual TCR CDR3 peaks in each VA-VB family. For clarity, 10% differences are differentially shaded. A smooth surface indicates no difference from the control sample. This comparison was possible since the tumor was almost exclusively infiltrated with CD4+ T-cells (see photomicrograph, top panel). Otherwise, CD4+ areas should have been microdissected. In addition, a comparison of TIL and tumor tissue (or vice versa [see bottom panel]) was possible since 98% of in vitro-cultured TIL stained positive for CD4 (see flow cytometry, right side).

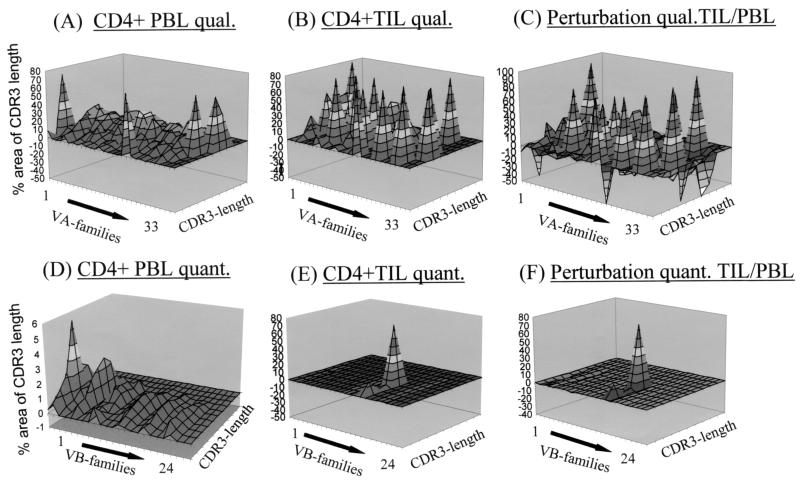

A different picture emerges if both qualitative and quantitative differences are examined in corresponding T-cell populations (e.g., CD4+ T cells) obtained from the peripheral circulation of patients at the same time as the tumor resection (Fig. 7). The difference in the results of the qualitative TCR analysis reveals prominent TCR VA and VB mRNA transcripts in TIL in contrast to CD4+ PBL. The quantitative TCR VB comparison exhibits the single prominent VB16 clone present in CD4+ TIL. Of note, CD4+ PBL stained up to 15% positive for TCR VB2 (Fig. 3A), which induces the almost invisible indent in the TCR landscape in the comparative analysis.

FIG. 7.

Comparative analysis of the TCR VA-VB repertoire in CD4+ TIL versus CD4+ PBL in patient 1. (A) Qualitative (qual.) TCR VA analysis in CD4+ sorted PBL. Due to the lack of anti-VA MAbs, no flow cytometry-based assessment was performed. (B and C) Similar to the experiment in Fig. 6, the TCR CDR3 landscape of the CD4+ TIL served as the control sample (B) and each VA CDR3 peak of CD4+ PBL was subtracted (C). (D and E) The same analysis was performed using the TCR VB-CDR3 pattern from TIL (E) as the template, from which the TCR VB CDR3 pattern from CD4+ PBL (D) was subtracted. These pictures allow an estimation of the degree of TCR similarity or dissimilarity in different T-cell compartments. (F) Subtraction of the qualitatively assessed CDR3-VB in PBL (Fig. 5A, panel III) from the CDR3-VB picture in CD4+ TIL (Fig. 4, panel III) shows the prominent overrepresentation of the TCR VB16 chain. quant., quantitative.

DISCUSSION

Clinical trials of the use of tumor-associated antigens in the form of antigenic peptides to augment CD8+ or CD4+ T-cell responses directed against autologous cancer cells have begun (12, 21, 27). Similar studies have been initiated targeting virus-associated antigens, e.g., from human immunodeficiency virus HIV, to induce a strong and effective cellular immune response (23, 28). One of the surrogate markers for successful immunization represents the “structural” characterization of T lymphocytes reacting to the immunizing peptide as determined by CDR3 length and DNA sequence analysis (36). CDR3, in which T-cell specificity resides (7), results from the somatic recombination of the TCR elements composed of the variable (v), joining (j), and constant (c) region of the TCR heterodimer.

The length of the TCR can be measured using a PCR-based approach by amplification of each individual TCR VA or VB family (Fig. 2). Typically, the length of the CDR3 in a given TCR VA or VB family represents a Gaussian distribution of 1 to 11 amino acid residues, or 3 to 33 bp, respectively (9, 24). Thus, using TCR CDR3 spectratyping, the nature of a given T-cell population can be molecularly described as polyclonal, oligoclonal, or monoclonal. This information can be useful in immunomonitoring (e.g., is the T-cell response directed against a defined target antigen monoclonal? Is the cellular immune response stable over time?). This PCR-based approach is very sensitive and may allow us to detect a single specific T cell out of 2 × 105 cells exhibiting different VDJ recombinations (5). Up to 54 individual reverse transcription-PCR amplifications, followed by a runoff reaction, must be performed to cover the TCR VA and VB repertoire. This also impacts on the expenses of clinical monitoring. This “low-resolution” approach has been instrumental in the study of T-cell dynamics, T-cell homeostasis, and restoration of the TCR repertoire in HIV-infected patients during antiretroviral therapy (23, 28, 36). In this situation, most studies addressed the quality, i.e., the structural anatomy, of the TCR repertoire as defined by the CDR3 length distribution. Different studies used TCR spectratyping in determining the TCR in patients with cancer (6, 16, 29, 30) or—the flip side of the coin—in those undergoing transplantation (3). A few pivotal studies showed that on immunization, a limited number of T-cell clones are activated and amplified, yielding a perturbation of the TCR landscape (4, 33). The disadvantage of this very powerful technique is the lack of quantitative measurement of individual VB families. At least in PBL, or in freshly isolated TIL or T cells from lymph nodes, a direct estimation of (almost) each TCR VB family can easily be performed using flow cytometry. Recent studies emphasized that the number of individual TCRs expressed on CTL is essential in determining the fine specificity and effector functions in antigen-specific T cells present in the peripheral circulation (14). These data emphasize the requirement for a quantitative TCR analysis, which is presently restricted to a comprehensive panel of TCR-specific VB MAbs. In addition, this information pertaining to quantity is critical, since approximately 40 to 70% of the T-cell pool in the peripheral circulation during the phase of an acute viral infection or in autoimmunity may be antigen specific and even dominated by a few T-cell clones (20, 37).

The examination of the total number of antigen-specific T cells has been revolutionized by using soluble MHC class I tetramer complexes loaded with the appropriate peptides (1). However, tetramer analysis allows exclusively the quantification of T cells for a given peptide in the context of a single MHC molecule. It does not provide information about whether the nature of an immune response is polyclonal or monoclonal or whether certain TCR VB families are expanded during the cellular immune response. This has been observed for some TCR VB families (e.g., VB14 and VB16) in patients with cancer (10, 12, 16, 29, 32). It may be advantageous to address the molecular composition and the quantity of the immune responses and to combine these results with tetramer staining (see e.g., reference 17). Tetramer analysis provides the number of MHC-restricted and peptide-specific T cells, and supplementation with the TCR-CDR3 analysis addresses whether this response is either polyclonal or monoclonal, or, rather, is dominated by a few TCR-clonotypes.

Cytotoxic T-cell responses play a pivotal role in the adaptive cellular immune response to tumor cells or in viral infections. Despite the potential number of peptide epitopes which could be presented on infected target cells, the majority of antitumor or antiviral cytotoxic T cells directed to one or several immunodominant T-cell epitopes is surprisingly focused (12, 18, 35). This may be dependent on the MHC-restriction of the peptide, which can be presented only by some MHC class I molecules, and the plasticity of the T-cell repertoire available at the time of infection. T-cell responses to viral components have been demonstrated to show antigen-specific biases in the variable-region usage of T cells and the CDR3 regions (35). If tetramer complexes are not used in the evaluation, at least two methods are available to gauge the quantity of TCR VB families in T-cell populations: either semiquantitative PCR analysis using competitor plasmids, Taq-man technology, or, alternatively, the direct determination of TCR VB families using a comprehensive panel of MAbs directed against the TCR VB chain (Table 1) in PBL or T cells infiltrating into tumor lesions (TIL). Our data show that the combination of the two data sets provides a more realistic picture of the CD4+ T-cell population. For instance, CDR3 analysis of patient 1 suggests an oligoclonal CD4+ T-cell population. This picture could be corrected only by using the flow cytometry-based determination of the TCR VB frequencies in this T-cell line. Almost all the CD4+ T cells are VB16 positive. This information is critical and would have been missed without a quantitative TCR analysis. Of note, these data provide the description of the molecular composition of a T-cell infiltrate which may be indicative of an ongoing immune response as determined by over-representation of (potentially monoclonal) TCR families. However, clinically meaningful data would have to be supplemented with information on the specificity and functional activity of these immune effector cells. To gauge the TCR VA frequencies, the number of anti-TCR VA-directed MAbs should be increased, which may represent a problem due to the relatively low antigenicity of the TCR VA chain compared to the VB chain in mice. Alternatively, a semiquantitative approach may be chosen to present a more realistic picture of a T-cell population. In summary, the TCR CDR3 analysis can be supplemented with a quantitative assessment of individual T-cell families. Flow cytometry-based quantification of TCR VB families present a fast and reliable assay to address the quantity of a T-cell response. The combined analysis of the CDR3 regions plus flow-based VB quantifications may be instrumental in the situations listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Indications for a combination of TCR CDR3 analysis with the quantitative TCR VB assessment

| Analysis | Advantages and comments |

|---|---|

| Definition of the CD4+/CD8+ T-cell population in patients with cancer or viral infection, or undergoing epitope-based vaccination | This may be useful if no tetramer reagents are available or if the entire CD4/CD8 T-cell population is examined for TCR diversity, particularly in studies addressing T-cell homeostasis |

| Identification of T-cell malignancies | Detection of monoclonal TCR transcripts and quantitation. |

| Determination of superantigen effects on T cells | Expansion of certain polyclonal VB families |

| Identification of individual expanded VB families in PBL or freshly harvested TIL | Individual VB families may be present in sufficient numbers to allow flow-cytometric sorting; such T cells may represent effector cells directed against cancer cells or virus-associated antigens |

| Longitudinal analysis of the quality and quantity of peripheral T cells in patients undergoing T-cell reconstitution, e.g. during highly active anti-retroviral therapy, or in patients receiving bone marrow transplantation | Can be used for gauging the restoration of the CD4/CD8 T-cell compartment(s) |

| Comparison of the TCR diversity within an individual patient in different anatomic compartments | To compare the T-cell infiltrate in the tumor (or any inflammatory) lesion, the T-cell infiltrate should be separated after CD4+/CD8+ staining to allow a comparison with the TCR diversity within the CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell population |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants SFB 432 (A9) and SFB 490 (C4) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to M.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman, J. D., P. A. Moss, P. J. Goulder, D. H. Barouch, M. G. McHeyzer-Williams, J. I. Bell, A. J. McMichael, and M. M. Davis. 1996. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 274:94-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker, A. B., S. H. van der Burg, R. J. Huijbens, J. W. Drijfhout, C. J. Melief, G. J. Adema, and C. G. Figdor. 1997. Analogues of CTL epitopes with improved MHC class-I binding capacity elicit anti-melanoma CTL recognizing the wild-type epitope. Int. J. Cancer 70:302-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bercovici, N., M. T. Duffour, S. Agrawal, M. Salcedo, and J. P. Abastado. 2000. New methods for assessing T-cell responses. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:859-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bousso, P., J. P. Levraud, P. Kourilsky, and J. P. Abastado. 1999. The composition of a primary T cell response is largely determined by the timing of recruitment of individual T cell clones. J. Exp. Med. 189:1591-1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casanova, J. L., and J. L. Maryanski. 1993. Antigen-selected T-cell receptor diversity and self-nonself homology. Immunol. Today 14:391-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole, D. J., M. C. Wilson, L. Rivoltini, M. Custer, and M. I. Nishimura. 1997. T-cell receptor repertoire in matched MART-1 peptide-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 57:5320-5327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, M. M., and P. J. Bjorkman. 1988. T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature 334:395-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genevee, C., A. Diu, J. Nierat, A. Caignard, P. Y. Dietrich, L. Ferradini, S. Roman-Roman, F. Triebel, and T. Hercend. 1992. An experimentally validated panel of subfamily-specific oligonucleotide primers (V alpha 1-w29/V beta 1-w24) for the study of human T cell receptor variable V gene segment usage by polymerase chain reaction. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:1261-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorochov, G., A. U. Neumann, A. Kereveur, C. Parizot, T. Li, C. Katlama, M. Karmochkine, G. Raguin, B. Autran, and P. Debre. 1998. Perturbation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell repertoires during progression to AIDS and regulation of the CD4+ repertoire during antiviral therapy. Nat. Med. 4:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hohn, H., H. Pilch, S. Gunzel, C. Neukirch, K. Freitag, A. Necker, and M. J. Maeurer. 2000. Human papillomavirus type 33 E7 peptides presented by HLA-DR*0402 to tumor-infiltrating T cells in cervical cancer. J. Virol. 74:6632-6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohn, H., T. Reichert, C. Neukirch, H. Pilch, and M. J. Maeurer. 1999. Monoclonal TCR mRNA transcripts are preferentially detected in the TCR variable alpha chain in CD8(+) T-lymphocytes: implications for immunomonitoring. Int. J. Mol. Med. 3:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jager, E., M. Maeurer, H. Hohn, J. Karbach, D. Jager, Z. Zidianakis, A. Bakhshandeh-Bath, J. Orth, C. Neukirch, A. Necker, T. E. Reichert, and A. Knuth. 2000. Clonal expansion of Melan A-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a melanoma patient responding to continued immunization with melanoma-associated peptides. Int. J. Cancer 86:538-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kugler, A., G. Stuhler, P. Walden, G. Zoller, A. Zobywalski, P. Brossart, U. Trefzer, S. Ullrich, C. A. Muller, V. Becker, A. J. Gross, B. Hemmerlein, L. Kanz, G. A. Muller, and R. H. Ringert. 2000. Regression of human metastatic renal cell carcinoma after vaccination with tumor cell-dendritic cell hybrids. Nat. Med. 6:332-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim, D. G., K. Bieganowska Bourcier, G. J. Freeman, and D. A. Hafler. 2000. Examination of CD8+ T cell function in humans using MHC class I tetramers: similar cytotoxicity but variable proliferation and cytokine production among different clonal CD8+ T cells specific to a single viral epitope. J. Immunol. 165:6214-6220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loftus, D. J., P. Squarcina, M. B. Nielsen, C. Geisler, C. Castelli, N. Odum, E. Appella, G. Parmiani, and L. Rivoltini. 1998. Peptides derived from self-proteins as partial agonists and antagonists of human CD8+ T-cell clones reactive to melanoma/melanocyte epitope MART1(27-35). Cancer Res. 58:2433-2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackensen, A., G. Carcelain, S. Viel, M. C. Raynal, H. Michalaki, F. Triebel, J. Bosq, and T. Hercend. 1994. Direct evidence to support the immunosurveillance concept in a human regressive melanoma. J. Clin. Investig. 93:1397-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maini, M. K., S. Reignat, C. Boni, G. S. Ogg, A. S. King, F. Malacarne, G. J. Webster, and A. Bertoletti. 2000. T cell receptor usage of virus-specific CD8 cells and recognition of viral mutations during acute and persistent hepatitis B virus infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:3067-3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maryanski, J. L., C. V. Jongeneel, P. Bucher, J. L. Casanova, and P. R. Walker. 1996. Single-cell PCR analysis of TCR repertoires selected by antigen in vivo: a high magnitude CD8 response is comprised of very few clones. Immunity 4:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miconnet, I., I. Coste, F. Beermann, J. F. Haeuw, J. C. Cerottini, J. Y. Bonnefoy, P. Romero, and T. Renno. 2001. Cancer vaccine design: a novel bacterial adjuvant for peptide-specific ctl induction. J. Immunol. 166:4612-4619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murali-Krishna, K., J. D. Altman, M. Suresh, D. J. Sourdive, A. J. Zajac, J. D. Miller, J. Slansky, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 8:177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nestle, F. O., S. Alijagic, M. Gilliet, Y. Sun, S. Grabbe, R. Dummer, G. Burg, and D. Schadendorf. 1998. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 4:328-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Offringa, R., S. H. van der Burg, F. Ossendorp, R. E. Toes, and C. J. Melief. 2000. Design and evaluation of antigen-specific vaccination strategies against cancer. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:576-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogg, G. S., S. Kostense, M. R. Klein, S. Jurriaans, D. Hamann, A. J. McMichael, and F. Miedema. 1999. Longitudinal phenotypic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: correlation with disease progression. J. Virol. 73:9153-9160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pannetier, C., J. Even, and P. Kourilsky. 1995. T-cell repertoire diversity and clonal expansions in normal and clinical samples. Immunol. Today 16:176-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puisieux, I., J. Even, C. Pannetier, F. Jotereau, M. Favrot, and P. Kourilsky. 1994. Oligoclonality of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from human melanomas. J. Immunol. 153:2807-2818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg, S. A. 1999. A new era for cancer immunotherapy based on the genes that encode cancer antigens. Immunity 10:281-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenberg, S. A., J. C. Yang, D. J. Schwartzentruber, P. Hwu, F. M. Marincola, S. L. Topalian, N. P. Restifo, M. E. Dudley, S. L. Schwarz, P. J. Spiess, J. R. Wunderlich, M. R. Parkhurst, Y. Kawakami, C. A. Seipp, J. H. Einhorn, and D. E. White. 1998. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat. Med. 4:321-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitz, J. E., M. J. Kuroda, S. Santra, V. G. Sasseville, M. A. Simon, M. A. Lifton, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, M. Dalesandro, B. J. Scallon, J. Ghrayeb, M. A. Forman, D. C. Montefiori, E. P. Rieber, N. L. Letvin, and K. A. Reimann. 1999. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science 283:857-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sensi, M., C. Farina, C. Maccalli, R. Lupetti, G. Nicolini, A. Anichini, G. Parmiani, and D. Berd. 1997. Clonal expansion of T lymphocytes in human melanoma metastases after treatment with a hapten-modified autologous tumor vaccine. J. Clin. Investig. 99:710-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sensi, M., and G. Parmiani. 1995. Analysis of TCR usage in human tumors: a new tool for assessing tumor-specific immune responses. Immunol. Today 16:588-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storkus, W. J., H. J. Zeh III, M. J. Maeurer, R. D. Salter, and M. T. Lotze. 1993. Identification of human melanoma peptides recognized by class I restricted tumor infiltrating T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 151:3719-3727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valmori, D., V. Dutoit, D. Lienard, F. Lejeune, D. Speiser, D. Rimoldi, V. Cerundolo, P. Y. Dietrich, J. C. Cerottini, and P. Romero. 2000. Tetramer-guided analysis of TCR beta-chain usage reveals a large repertoire of melan-A-specific CD8+ T cells in melanoma patients. J. Immunol. 165:533-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valmori, D., J. F. Fonteneau, C. M. Lizana, N. Gervois, D. Lienard, D. Rimoldi, V. Jongeneel, F. Jotereau, J. C. Cerottini, and P. Romero. 1998. Enhanced generation of specific tumor-reactive CTL in vitro by selected Melan-A/MART-1 immunodominant peptide analogues. J. Immunol. 160:1750-1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valmori, D., J. F. Fonteneau, S. Valitutti, N. Gervois, R. Dunbar, D. Lienard, D. Rimoldi, V. Cerundolo, F. Jotereau, J. C. Cerottini, D. E. Speiser, and P. Romero. 1999. Optimal activation of tumor-reactive T cells by selected antigenic peptide analogues. Int. Immunol. 11:1971-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace, M. E., M. Bryden, S. C. Cose, R. M. Coles, T. N. Schumacher, A. Brooks, and F. R. Carbone. 2000. Junctional biases in the naive TCR repertoire control the CTL response to an immunodominant determinant of HSV-1. Immunity 12:547-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson, J. D., G. S. Ogg, R. L. Allen, P. J. Goulder, A. Kelleher, A. K. Sewell, C. A. O'Callaghan, S. L. Rowland-Jones, M. F. Callan, and A. J. McMichael. 1998. Oligoclonal expansions of CD8(+) T cells in chronic HIV infection are antigen specific. J. Exp. Med. 188:785-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong, F. S., J. Karttunen, C. Dumont, L. Wen, I. Visintin, I. M. Pilip, N. Shastri, E. G. Pamer, and C. A. Janeway, Jr. 1999. Identification of an MHC class I-restricted autoantigen in type 1 diabetes by screening an organ-specific cDNA library. Nat. Med. 5:1026-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]