Abstract

An undeniable risk factor for cervical cancer and intraepithelial neoplasia is persistent infection with HPV – types 16,18, 31, 45, 52 and others. Changes in sexual behavior may, in the coming decades, influence the epidemiology of HPV-related lesions. For those diseases, vaccination against HPV may be the only effective mean of prevention. Our study aims to show the results and changes in the smear for HPV DNA in patients after receiving a vaccination course with a 9-valent HPV vaccine in women with HPV infection. Out of 320 subjects with HPV- positive result 250 (78.1%) decided to be vaccinated against HPV, and 70 (21.9%) did not. All patients included in the analysis had not been vaccinated with any commercially available HPV vaccines in the past. In the vaccinated group, the rate of HPV disappearance was significantly higher over the follow-up period than in the control group. This applies especially to the complete disappearance of the HPV - in 72.4% vaccinated women compared to 45.7% unvaccinated. This effect is especially visible when analyzing the disappearance of HPV genotypes covered by the 9-valent vaccine. The proportion of negative HPV outcome differed significantly between vaccinated patients with LEEP (81.1%), vaccinated patients without LEEP (59.8%), non-vaccinated patients with LEEP (57.1%), and non-vaccinated patients without LEEP (34.3%), and the differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Vaccination in patients with histopathologically confirmed HSIL will probably reduce the occurrence of different HPV-related lesions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-92861-5.

Keywords: HPV vaccination, 9-valent vaccination, HPV infection, Treatment of HPV, HPV-related disease, SIL, LEEP –conization, Disappearance of HPV infection

Subject terms: Vaccines, Population screening, Health care, Oncology

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) remains a significant global health challenge despite being theoretically preventable. It ranks as the fourth most common malignancy in women worldwide. In 2020 alone, there were an estimated 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths attributed to this disease1. An undeniable risk factor for cervical cancer and intraepithelial neoplasia is persistent infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV) – not only genotypes 16 and 18 but also 31, 45, and 522. Infections with oncogenic HPV genotypes include not only lesions of the cervix but also precancerous conditions and cancers of the head and neck, vagina, vulva, anus, and penis. Detection and treatment of LSIL-CIN 1, HSIL-CIN 2 and CIN 3 lesions is now simple and widely available. The availability of numerous diagnostic tests, including the self-sampling option, and the low invasiveness of colposcopic examination, now supported more and more often by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), mean that these tests are most often performed on an outpatient basis3,4. The LEEP-conization procedure, which involves excising the lesion without or with the entire transformation zone, is a simple procedure that does not require the conditions of an operating room and can be performed by any trained gynaecologist. Currently, a greater challenge is the diagnosis and treatment of HPV-related lesions, including lesions in the vagina, vulva, and anus5. Removal of this type of lesion is often not radical or impossible because the topography is too close to the bladder or rectum and carries a very high risk of damaging other organs and creating a fistula. The use of preventive vaccines in the population of sexually initiated women, including HPV-positive women, may facilitate remission of the HPV virus, create immunological immunity, and reduce the occurrence of SIL-type lesions, mainly in the cervix, vagina, vulva, and anus.

Due to the discovery and implementation of preventive vaccinations against HPV, many countries are on the way to eliminating HPV-related cancers and diseases. Examples include New Zealand and Australia, Scandinavia, and Great Britain. In addition to population vaccination, these countries are also introducing solutions for the adult population - such as opportunistic HPV vaccination at universities. Currently, the vaccine with the widest range of action is the 9-valent vaccine, which protects against HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58, is safe and effective and will further reduce the incidence of HPV infection and HPV-related cancers. The vaccine is usually administered according to a three-dose schedule, but adolescents receiving primary prevention receive two doses of the vaccine.

In fact, despite studies showing consistent results in the direction of efficacy, there is still scepticism in the scientific community about the use of the HPV vaccine as an adjuvant therapy after local treatment, against relapses and in HPV-positive population after sexual initiation. Individuals with human papillomavirus (HPV)-related disease remain at risk for subsequent HPV infection and related disease after treatment of specific lesions. Additionally, patients treated for HPV-related high-grade histologic lesions have a significantly increased risk of developing HPV-related malignancies in the 20 years following treatment compared with the general population6,7. More and more voices appear in the scientific and social debate, not only in the context of the preventive role of vaccination against HPV. The world is moving forward, now in the so-called “post-HPV vaccination era” - this is the time when the first patients vaccinated prophylactically at the age of 14 reached the common age for the development of CIN - studies and meta-analyses show what the risk is for these patients in terms of the development of HPV-dependent lesions. There are no documented contraindications to vaccination against HPV in people with current HPV infection8,9. Additionally, people with previously diagnosed HPV infection have an increased risk of recurrence of HPV-related lesions, even after surgical treatment10–12.

Moreover, not only children and young adults decide to get vaccinated - but also adult women and men. This is a dimension of mutual responsibility between couples. Evidence also shows the value of vaccinating people who are immunosuppressed and infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). People with warts and condylomas developing because of infection with non-oncogenic HPV types are vaccinated - although there is no hard evidence to reduce the risk of recurrence13,14.

Changes in sexual customs and behaviour in both women and men may, in the coming decades, influence the epidemiology of HPV-related cancers and diseases occurring in the nasopharynx, larynx, vagina, vulva, cervix, and anus. In these population groups, the vaccine may be the only effective mean of prevention. It is worth mentioning how difficult it is to obtain an appropriate amount of material for molecular tests and how difficult it is to detect and recognize precancerous lesions of the SIL type that do not occur in the cervix.

Secondary prevention tools beyond the cervix are non-existent. Since strictly therapeutic vaccines are still in the research phase and are not commercially available, many adults infected with HPV have undergone vaccination against HPV. Nowadays outcome measures concern different parameters—safety, the immune response against peptide p16, tumor response by RECIST, overall response rate (ORR), overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and more. There are four categories of HPV treatment vaccines: live vector-based vaccines, peptide and protein-based vaccines, nucleic acid-based vaccines, and whole-cell vaccines. The use of a preventive vaccine in the future should not exclude the possibility of using a therapeutic vaccine with a personalized distribution of HPV genotypes15,16. It should be emphasized that the vaccine should be an additional measure and therapeutic procedures cannot be abandoned in justified cases, such as HSIL changes. However, the population of people willing to vaccinate in adulthood is constantly increasing thanks to growing public awareness. In recent years, reports have begun to appear regarding the beneficial effect of vaccination, the possibility of reducing the risk of recurrence of lesions, and the potential impact on the disappearance of HPV. This study aims to show the results and changes in the smear for HPV DNA in patients after receiving a vaccination course with a 9-valent HPV vaccine in women with HPV infection diagnosed in a cervical smear and this is an extended study of work published last year.

Methodology

Study design

We provide a prospective, ongoing, non-randomized study to determine the effect of nine-valent HPV vaccination in HPV-positive patients with Gardasil®9 recombinant, a nine-valent vaccine. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Bioethical Committee approved the study protocol (95/2021). We obtained informed consent for the study from all patients.

All subjects reported to a private gynaecological practice focused on and specialized in cervical cancer diagnosis in the years 2020–2023. This is a group of patients who called for in-depth diagnostics due to a positive HPV HR test result and/or an abnormal cytological result. To verify the final diagnosis, the patients underwent colposcopy with cervical biopsy and curettage of the cervical canal. To enhance the immunological response, all subjects were offered vaccination against HPV with the nine-valent vaccine in the 0-2-6 scheme. Of 320 patients, 250 (78.1%) decided to be vaccinated and 70 (21.9%) did not. Wherever “Gardasil-type” genotypes are mentioned in the text, both in a matter of presence and disappearance, they were types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

The inclusion criteria comprised:

Adult females only, aged between 18 and 53.

Non-pregnant or postpartum individuals.

Subjects not undergoing immunosuppressive drug treatment.

No prior vaccination with other HPV vaccines.

Expressing informed consent to participate.

Consenting to proposed surgical diagnostics and potential surgical excision treatment if indicated.

Having received three doses of the nine-valent HPV vaccination following the 0- 2- 6 month schedule.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Refusal of potential treatment for squamous intraepithelial lesions.

Failure to complete the full vaccination regimen.

The analysis is the last chance to assess the effect of adjuvant anti-HPV vaccination in the population not vaccinated in adolescence because a generation more likely to be covered by primary prevention programs is entering adulthood.

All patients with histopathologically confirmed high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (CIN 2+) were treated according to the current recommendations of the Polish Colposcopic Society, with the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) and then subjected to strict control every six months. The control group includes seventy HPV-positive patients diagnosed with pre-neoplastic lesions who decided not to receive the HPV vaccine.

LBC, HPV genotyping and colposcopy with punch biopsy

The cervix and endocervix material were collected with a Cyto-Brush and placed in a liquid medium, PreservCyt® (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Meylan, France). Then, we performed PCR followed by a DNA enzyme immunoassay with a reverse hybridization line probe assay for HPV detection. Sequential analysis was performed to characterize HPV-positive samples. We used Roche Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test®, which identifies 32 HPV DNA of the following genotypes: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68 (high-risk genotypes); 26, 53, 66, 70, 73 and 82 (probable high-risk genotypes); and 6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 62, 67, 81, 83 and 89 (low-risk genotypes) or the BD Onclarity HPV Assay detecting 14 different HPV genotypes while incorporating a β-globin internal control (IC) as a processing control. The HPV genotypes that can be detected individually are HPV 16, 18, 31, 45, 51, and 52. The remaining genotypes are grouped as follows: HPV 33/58, 56/59/66, and 35/39/68. The IC serves as a control to ensure the accuracy and validity of the assay.

Colposcopy was performed in case of: (1) abnormal cervical image under gynaecological examination; (2) abnormal LBC result, i.e., ASC-US, AGC, LSIL, ASC-H, HSIL, cervical cancer; and (3) positive high-risk HPV test result (genotype 16, 18 or 31). The colposcopy was performed according to the International Federation of Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy classification. At least one cervix biopsy from the transformation zone (TZ) and cervical canal curettage was taken in all cases.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted with statistical software R, version R4.1.2. All analyses assumed a significance level of α = 0.05. Nominal variables were presented as n and %, and age was summarised with mean and standard deviation. Dependencies between categorical variables were analysed with Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A comparison of age as a numeric variable between study groups was conducted with a t-Student test. Normality of distributions was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test, as well as skewness and kurtosis. Variance homogeneity was assessed using Levene’s test.

Results

Study groups characteristics and comparison

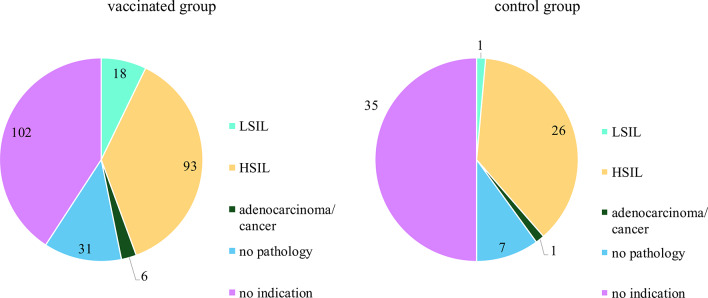

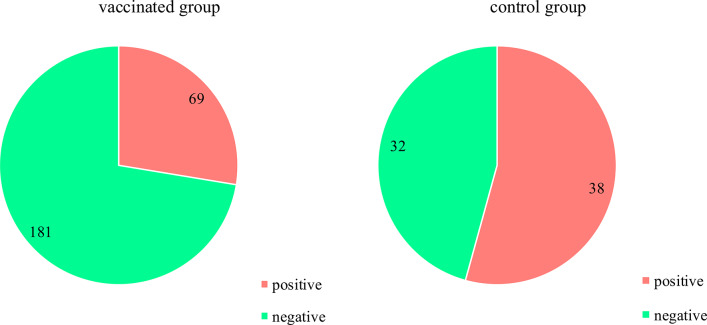

The study groups characteristics were presented in Table 1. There were 250 patients in the vaccinated group and 70 in the control group. The mean age in the vaccinated group was 32 years and the same in the control group. In both groups, the percentages in each age category were similar - most patients were aged 25–34, fewer in the group of patients 35 and older, and the least in the youngest age group. Patients from both study groups did not differ in cytology outcome, HPV genotypes before vaccination, biopsy outcome, and LEEP/surgery outcome (p > 0.05). HPV outcomes after vaccination differentiated the groups. The vaccinated group had significantly lower proportion of positive outcome for any HPV genotype (27.6% vs. 54.3% in the control group), p < 0.001. The vaccinated group had a significantly lower proportion of positive outcome for the HPV Gardasil genotype (14.8% vs. 40.0% in the control group), p < 0.001. We described the HPV results after the vaccination or observation period according to a 5-point scale that took into account whether the patient’s cervix remained the same HPV genotype (1), whether some of the genotypes disappeared (2), completely disappeared (3), or whether infection with a new genotype appeared (4) or some genotypes disappeared, but new ones also appeared (5). The vaccination/observation outcome described by the 5-category scale was significantly different between groups, p < 0.001. The proportion of patients with the same genotypes after vaccination was lower in the vaccinated group (6.4% vs. 32.9% in the control group). The proportion of patients with partially same genotypes after vaccination was lower in the vaccinated group (5.2% vs. 8.6%). The complete remission rate was higher in the vaccinated group (72.4% vs. 45.7%). The proportion of new infections was higher in the vaccinated group (12.4% vs. 5.7%), and the proportion of patients with the same/partially same genotype and new infection was higher in the vaccinated group (3.6% vs. 7.1% in the control group). Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 show the comparison between the vaccinated and control groups in terms of HPV outcomes, histopathological outcomes obtained by LEEP-conization or during surgery and after the vaccination or observation period - HPV outcomes in general and considering the genotypes included in the Gardasil® 9 vaccine.

Table 1.

Characteristics and comparison of study groups.

| Characteristics | Vaccinated group | Control group | MD (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 250 (100.0) | 70 (100.0) | - | - |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 32.72 ± 6.56 | 32.50 ± 6.69 | 0.22 (−1.55;2.00) | 0.8031 |

| Age, years, n (%) | ||||

| < 25 | 20 (8.0) | 10 (14.3) | - | 0.1102 |

| < 35 | 149 (59.6) | 33 (47.1) | ||

| ≥ 35 | 81 (32.4) | 27 (38.6) | ||

| Cytology, n (%) | ||||

| NILM | 40 (16.0) | 12 (17.1) | - | 0.831 |

| AS-CUS | 33 (13.2) | 14 (20.0) | ||

| LSIL | 88 (35.2) | 25 (35.7) | ||

| ASC-H | 47 (18.8) | 11 (15.7) | ||

| HSIL | 34 (13.6) | 7 (10.0) | ||

| AGC | 6 (2.4) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Cancer | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| HPV Gardasil genotype, n (%) | ||||

| Positive | 207 (82.8) | 54 (77.1) | - | 0.366 |

| Negative | 43 (17.2) | 16 (22.9) | ||

| HPV genotype, n (%)* | ||||

| 6 | 23 (9.2) | 1 (1.4) | - | 0.0542 |

| 11 | 5 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | 0.590 |

| 16 | 109 (43.6) | 37 (52.9) | - | 0.2152 |

| 18 | 37 (14.8) | 4 (5.7) | - | 0.0712 |

| 31 | 40 (16.0) | 10 (14.3) | - | 0.8712 |

| 33 | 14 (5.6) | 3 (4.3) | - | > 0.999 |

| 35 | 7 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | - | 0.354 |

| 39 | 13 (5.2) | 2 (2.9) | - | 0.537 |

| 40 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| 42 | 8 (3.2) | 2 (2.9) | - | > 0.999 |

| 43 | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| 44 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| 45 | 13 (5.2) | 1 (1.4) | - | 0.318 |

| 51 | 23 (9.2) | 7 (10.0) | - | > 0.9992 |

| 52 | 19 (7.6) | 6 (8.6) | - | 0.9872 |

| 53 | 15 (6.0) | 6 (8.6) | - | 0.6212 |

| 54 | 6 (2.4) | 3 (4.3) | - | 0.416 |

| 55 | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| 56 | 18 (7.2) | 8 (11.4) | - | 0.3702 |

| 58 | 9 (3.6) | 2 (2.9) | - | > 0.999 |

| 59 | 8 (3.2) | 2 (2.9) | - | > 0.999 |

| 61 | 7 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) | - | > 0.999 |

| 62 | 11 (4.4) | 2 (2.9) | - | 0.741 |

| 66 | 11 (4.4) | 7 (10.0) | - | 0.082 |

| 67 | 11 (4.4) | 1 (1.4) | - | 0.475 |

| 68 | 7 (2.8) | 2 (2.9) | - | > 0.999 |

| 70 | 4 (1.6) | 3 (4.3) | - | 0.180 |

| 73 | 9 (3.6) | 1 (1.4) | - | 0.697 |

| 81 | 4 (1.6) | 2 (2.9) | - | 0.615 |

| 82 | 8 (3.2) | 2 (2.9) | - | > 0.999 |

| 83 | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| 84 | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| 87 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| 89 | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.4) | - | 0.524 |

| 90 | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| CP6108 | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| CP6109 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| P1 | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | - | > 0.999 |

| P2 | 5 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | 0.590 |

| P3 | 4 (1.6) | 1 (1.4) | - | > 0.999 |

| Biopsy, n (%) | ||||

| LSIL | 57 (22.8) | 12 (17.1) | - | 0.669 |

| HSIL | 115 (46.0) | 32 (45.7) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 4 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Cancer | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No pathology | 55 (22.0) | 21 (30.0) | ||

| No indication | 17 (6.8) | 5 (7.1) | ||

| LEEP/surgery, n (%) | ||||

| LSIL | 18 (7.2) | 1 (1.4) | - | 0.3252 |

| HSIL | 93 (37.2) | 26 (37.1) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma/cancer | 6 (2.4) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| No pathology | 31 (12.4) | 7 (10.0) | ||

| No indication | 102 (40.8) | 35 (50.0) | ||

| LEEP/surgery, n (%) | ||||

| Any outcome | 148 (59.2) | 35 (50.0) | - | 0.2162 |

| No indication | 102 (40.8) | 35 (50.0) | ||

| HPV any genotype, after vac., n (%) | ||||

| Positive | 69 (27.6) | 38 (54.3) | - | < 0.0012 |

| Negative | 181 (72.4) | 32 (45.7) | ||

| HPV Gardasil genotype, after vac., n (%) | ||||

| Positive | 37 (14.8) | 28 (40.0) | - | < 0.0012 |

| Negative | 213 (85.2) | 42 (60.0) | ||

| Category (before vs. after vac.), n (%) | ||||

| Same genotype | 16 (6.4) | 23 (32.9) | - | < 0.0012 |

| Partially same genotype | 13 (5.2) | 6 (8.6) | ||

| Complete remission | 181 (72.4) | 32 (45.7) | ||

| New infection | 31 (12.4) | 4 (5.7) | ||

| Same/partially same genotype and new infection | 9 (3.6) | 5 (7.1) | ||

Groups were compared with t-Student test1, Pearson’s Chi-square test2, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

SD standard deviation, MD mean difference (Gardasil group vs. control group), n number, CI confidence interval, ASC-US atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance, AGC atypical glandular cells, ASC-H atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, LSIL low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HPV human papillomavirus, NILM negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy, LBC liquid-based cytology, P1 - HPV 33/58; P2 HPV 56/59/66; P3–35/39/68; LEEP loop electrosurgical excision procedure, vac vaccination.

*Various genotypes could be observed for one patient.

Fig. 1.

HPV outcome (Gardasil genotype) in the vaccinated group and the control group before vaccination/observation time.

Fig. 2.

Histopathological outcomes in LEEP-conization or during surgery in the vaccinated group and the control group.

Fig. 3.

HPV outcome (any genotype) in the vaccinated group and the control group after vaccination/observation time.

Fig. 4.

HPV outcome (Gardasil genotype) in the vaccinated group and the control group after vaccination/observation time.

Dependencies between age and HPV +/− after vaccination as well as between leep/surgery outcome and HPV +/− after vaccination

In the vaccinated group, HPV outcome after vaccination significantly depended on LEEP/surgery outcome. The proportion of no indication of LEEP/surgery was significantly higher among patients with positive HPV after vaccination compared to negative HPV after vaccination (59.4% vs. 33.7%), p < 0.001. The structure of LEEP/surgery detailed outcome was significantly different between positive and negative HPV after surgery, p = 0.005, with the main difference lying in the proportion of HSIL, which was lower among patients with positive HPV outcome (21.7% vs. 43.1% among patients with negative HPV outcome after vaccination). Dependence of age and HPV outcome after vaccination was not confirmed (p = 0.163).

In the control group, dependencies between age and HPV outcome after vaccination and between LEEP/surgery outcome and HPV outcome after vaccination were not confirmed (p > 0.05), Table 2.

Table 2.

Dependencies between HPV outcome after vaccination and age and between HPV outcome after vaccination and leep/surgery outcome.

| Characteristics | Vaccinated group | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV any genotype after vac. | p | HPV any genotype after vac. | p | |||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |||

| Age, years, n (%) | ||||||

| < 25 | 9 (13.0) | 11 (6.1) | 0.163 | 6 (15.8) | 4 (12.5) | 0.424 |

| < 35 | 37 (53.6) | 112 (61.9) | 20 (52.6) | 13 (40.6) | ||

| ≥ 35 | 23 (33.3) | 58 (32.0) | 12 (31.6) | 15 (46.9) | ||

| LEEP/surgery, n (%) | ||||||

| LSIL | 4 (5.8) | 14 (7.7) | 0.005 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.1) | 0.1611 |

| HSIL | 15 (21.7) | 78 (43.1) | 11 (28.9) | 15 (46.9) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma/cancer | 1 (1.4) | 5 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No pathology | 8 (11.6) | 23 (12.7) | 3 (7.9) | 4 (12.5) | ||

| No indication | 41 (59.4) | 61 (33.7) | 23 (60.5) | 12 (37.5) | ||

| LEEP/surgery, n (%) | ||||||

| Any outcome | 28 (40.6) | 120 (66.3) | < 0.001 | 15 (39.5) | 20 (62.5) | 0.093 |

| No indication | 41 (59.4) | 61 (33.7) | 23 (60.5) | 12 (37.5) | ||

Groups compared with Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test1, as appropriate.

n number, LSIL low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, LEEP loop electrosurgical excision procedure, vac vaccination.

Dependencies between HPV (Gardasil type) +/− before vaccination and HPV +/− after vaccination

In the Gardasil group, the proportion of positive HPV outcomes after vaccination did not depend on the proportion of positive outcomes of HPV Gardasil genotype before vaccination, both in perspective of any HPV genotype after vaccination and Gardasil HPV genotype after vaccination (p = 0.890 and p = 0.176, respectively).

In the control group no difference between groups with and without HPV Gardasil genotype before vaccination/observation was observed in the proportion of positive HPV of any genotype after vaccination/observation (p = 0.069). The proportion of positive HPV Gardasil genotype after vaccination/observation was higher in the group with positive HPV Gardasil genotype before vaccination/observation (51.9% vs. 0.0% in the group without HPV Gardasil genotype before vaccination/observation), p = 0.001, Table 3.

Table 3.

Dependence between HPV outcomes before vaccination (Gardasil genotype) and HPV outcomes after vaccination.

| Characteristics | vaccinated group | control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV Gardasil genotype before vac. | p | HPV Gardasil genotype before vac. | p | |||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |||

| HPV any genotype, after vac., n (%) | ||||||

| Positive | 58 (28.0) | 11 (25.6) | 0.890 | 33 (61.1) | 5 (31.2) | 0.069 |

| Negative | 149 (72.0) | 32 (74.4) | 21 (38.9) | 11 (68.8) | ||

| HPV Gardasil genotype, after vac., n (%) | ||||||

| Positive | 34 (91.9) | 173 (81.2) | 0.176 | 28 (51.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| Negative | 3 (8.1) | 40 (18.8) | 26 (48.1) | 16 (100.0) | ||

Groups compared with Pearson’s Chi-square test.

HPV human papillomavirus, vac vaccination.

Dependencies between age and category, as well as between leep/surgery outcome and category

In the Gardasil group category, HPV outcome after vaccination was significantly related to LEEP/surgery outcome. The proportion of no indication to LEEP/surgery was the highest among patients with the same genotype after vaccination (87.5%), lower among patients with new infection (54.8%), partially same genotype (46.2%, n = 6) and same/partially same genotype with new infections (44.4%, n = 4). The proportion of no indication was the lowest among patients with complete remission (33.7%), p = 0.041.

The detailed LEEP/surgery outcome was significantly related to the HPV outcome category after vaccination, p = 0.048. The main differences were observed in the proportion of HSIL and the proportion of no pathology. The proportion of HSIL was the highest among patients with the same/partially the same genotype and new infection (44.4%, n = 4) and patients with complete remission (43.1%), lower among patients with the partially same genotype (23.1%, n = 3) and new infection (22.6%, n = 2) and the lowest among patients with the same genotype (6.2%, n = The proportion of no pathology was the highest among patients with partially same genotype (23.1%, n = 1) and lower among patients with and new infections (16.1%, n = 5) and complete remission (12.7%). The proportion of no pathology was 0.0% in groups with the same genotype and the same/partially the same genotype and new infection.

In the control group, dependencies between age and category of HPV outcome after vaccination, as well as between LEEP/surgery outcome and category of HPV outcome after vaccination, were not confirmed (p > 0.05), Table 4.

Table 4.

Dependencies between the category of HPV outcomes after vaccination on age and leep/surgery outcome.

| Characteristics | Category of HPV outcomes after vaccination | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same genotype | Partially same genotype | Complete remission | New infection | Same/partially same genotype and new infection | ||

| Gardasil group | ||||||

| Age, years, n (%) | ||||||

| < 25 | 3 (18.8) | 2 (15.4) | 11 (6.1) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (22.2) | 0.674 |

| < 35 | 8 (50.0) | 9 (69.2) | 112 (61.9) | 16 (51.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

| ≥ 35 | 5 (31.2) | 2 (15.4) | 58 (32.0) | 13 (41.9) | 3 (33.3) | |

| LEEP/surgery, n (%) | ||||||

| LSIL | 1 (6.2) | 1 (7.7) | 14 (7.7) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (11.1) | 0.048 |

| HSIL | 1 (6.2) | 3 (23.1) | 78 (43.1) | 7 (22.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Adenocarcinoma/cancer | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.8) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No pathology | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 23 (12.7) | 5 (16.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No indication | 14 (87.5) | 6 (46.2) | 61 (33.7) | 17 (54.8) | 4 (44.4) | |

| LEEP/surgery, n (%) | ||||||

| Any outcome | 2 (12.5) | 7 (53.8) | 120 (66.3) | 14 (45.2) | 5 (55.6) | 0.041 |

| No indication | 14 (87.5) | 6 (46.2) | 61 (33.7) | 17 (54.8) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Control group | ||||||

| Age, years, n (%) | ||||||

| < 25 | 3 (13.0) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0.502 |

| < 35 | 12 (52.2) | 3 (50.0) | 13 (40.6) | 2 (50.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| ≥ 35 | 8 (34.8) | 1 (16.7) | 15 (46.9) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| LEEP/surgery, n (%) | ||||||

| LSIL | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.144 |

| HSIL | 4 (17.4) | 1 (16.7) | 15 (46.9) | 3 (75.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Adenocarcinoma/cancer | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No pathology | 1 (4.3) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No indication | 18 (78.3) | 3 (50.0) | 12 (37.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

| LEEP/surgery, n (%) | ||||||

| Any outcome | 5 (21.7) | 3 (50.0) | 20 (62.5) | 4 (100.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0.305 |

| No indication | 18 (78.3) | 3 (50.0) | 12 (37.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

Groups compared with Fisher’s exact test.

n number, LSIL low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, LEEP loop electrosurgical excision procedure, vac vaccination.

The proportion of negative HPV outcome differed significantly between vaccinated patients with LEEP (81.1%), vaccinated patients without LEEP (59.8%), non-vaccinated patients with LEEP (57.1%), and non-vaccinated patients without LEEP (34.3%), p < 0.001. The highest proportion of negative HPV outcome was accomplished in the vaccinated group with LEEP (81.1%). Vaccination increased the proportion of negative HPV outcomes among patients with LEEP. The proportion of negative HPV outcome among vaccinated patients with LEEP was 81.1%, and among non-vaccinated patients with LEEP, it was 57.1%, p = 0.008. Vaccination increased the proportion of negative HPV outcomes among patients without LEEP. The proportion of negative HPV outcome among vaccinated patients without LEEP was 59.8%, and among non-vaccinated patients without LEEP, it was 34.3%, p = 0.016, Table 5.

Table 5.

Dependencies between HPV outcome and vaccination/leep.

| Characteristics | Gardasil group with LEEP (1) | Control group with LEEP (2) | Gardasil group without LEEP (3) | Control group without LEEP (4) | p (comparison of 4 groups) | p (comparison 1 vs. 2) | p (comparison 3 vs. 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV any genotype after vac. | |||||||

| Positive | 28 (18.9) | 15 (42.9) | 41 (40.2) | 23 (65.7) | < 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.016 |

| Negative | 120 (81.1) | 20 (57.1) | 61 (59.8) | 12 (34.3) | |||

Groups compared with Pearson’s Chi-square test. p values were calculated using Benjamini & Hochberg’s adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

The study was intended to answer the question about changes in the cervical smear for HPV in HPV-positive patients after receiving the 9-valent HPV vaccine. The main result of the analysis was that in the vaccinated group the rate of HPV disappearance was significantly higher over the follow-up period than in the control group. This applies especially to the so-called complete remission, i.e., the complete disappearance of the HPV virus - it was observed in nearly ¾ of vaccinated women (72.4%) compared to less than half of unvaccinated patients (45.7%). This effect is especially visible when analysing the disappearance of HPV genotypes covered by the 9-valent vaccine. The proportion of positive HPV Gardasil genotype after vaccination/observation was significantly higher in group with positive HPV Gardasil genotype before vaccination/observation (51.9% vs. 0.0%, p = 0.001).

There are insufficient studies that could be related to our results. Just as the preventive effect of vaccination on the development of lesions has been proven, scientific reports show the beneficial effect of vaccination on reducing the recurrence of HPV-related lesions. However, we have not found any literature on the disappearance of HPV infection in the smear. Our previous analysis, including a smaller study group, showed the added value of vaccination in the group of HPV-positive patients17.

Vaccination can reasonably be expected to prevent new HPV infections caused by different HPV types, as well as reinfections with the same HPV type. This protection applies to new exposures from infected partners and to autoinoculation from adjacent or distant sites that are already productively infected. Since the recurrence rate of HSIL after surgical treatment is still over 6%, it means that only eliminating or neutralizing the HPV virus gives a chance to reduce the percentage18. Persistent infection with a highly oncogenic HPV genotype is the only modifiable risk factor for pre- and cancer-related conditions. However, the mechanism of function of the HPV vaccine in patients already infected with HPV is still not fully understood.

Konstantinos S Kechagias, with co-authors presented a systematic review and meta-analysis on the role of HPV vaccination at the time of local surgical treatment for cervical and other diseases related to HPV infection, with a rigorous methodological assessment of risk of bias, heterogeneity, and appropriate data. The researchers revealed that the risk of recurrence of CIN2 + was reduced in vaccinated patients who were vaccinated compared with those who were not vaccinated (according to data collected from 11 articles). Interestingly, the effect estimate was stronger when the risk of recurrence of CIN2 + was assessed for diseases related to HPV subtypes HPV16 or HPV18. The risk of recurrence of CIN3 was also reduced in vaccinated patients12. The authors’ conclusions that the impact on reducing the recurrence of lesions associated with the presence of HPV 16 and 18 may be related to the fact that the availability of bivalent and quadrivalent vaccinations was the highest a few or a dozen years ago. Perhaps, thanks to the increasing availability of the 9-valent vaccine, in a dozen or so years, we will be able to present a meta-analysis covering the disappearance of CIN 2 + lesions associated with other genotypes covered by the vaccine. Our study also shows how the number of HPV-negative patients changes in follow-up depending on both factors - not only LEEP-conization but also vaccination. The proportion of negative HPV outcome differed significantly between vaccinated patients with LEEP (81.1%), non-vaccinated patients with LEEP (57.1%), vaccinated patients without LEEP (59.8%) and non-vaccinated patients without LEEP (34.3%), and the differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

In addition to the potential effect of HPV vaccination on reducing the risk of cervical recurrence, studies have shown a beneficial effect on HPV-dependent, non-oncogenic lesions, such as recurrent laryngeal papillomatosis or condyloma acuminata. Researchers also attempted to assess the impact of vaccination in other, less common HPV-related diseases affecting the vulva or vagina. Testing for the presence of HPV DNA in a cervical smear is currently the only screening method allowing early detection of changes in the vagina or vulva. Evidence shows that prophylactic HPV vaccination, as in the case of cervical cancer precursors, also prevents HPV-related vulvar and vaginal HPV-associated precancers12,13.

Several studies suggested that HPV vaccination has a statistically significant impact in reducing post-surgical recurrent disease both in women and men exposed to previous HPV infection19–21. In 2012, Joura et al. reported that HPV vaccination among women after surgical treatment for HPV-related disease significantly reduced the incidence of subsequent significant impact of adjuvant HPV vaccination in reducing the risk of recurrence of genital warts after initial surgical treatment19. In 2021, Ghelardi et al. documented the effectiveness of the HPV vaccine in preventing recurrent disease after surgical treatment for vulvar high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions21. There are discussions in extensive reviews about the reduced risk of recurrence of CIN lesions22,23; however, the time of administering the vaccine peri- or post-procedure has not been standardised, and there are no clear guidelines on when it should be administered.

A similar analysis was presented by the publication’s authors in 2023, describing the evidence for using prophylactic HPV vaccines in patients with HPV-associated disease before, during, or after treatment. The researchers discussed potential mechanisms by which individuals with HPV-associated disease may or may not benefit from prophylactic vaccines18.

More and more doctors and scientific societies encourage vaccinating an increasingly older patient population. The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology recommends adherence to current CDC recommendations for vaccination of individuals aged 9 to 26 years and consideration of the possible benefit of adjuvant HPV vaccination during shared decision-making for previously unvaccinated individuals aged 27 to 45 years who are undergoing treatment for CIN2+24.

Our previous work on the immune response confirms a higher titer of anti-HPV antibodies in post-vaccination patients who remain infected with HPV. Still, no scientific studies to date describe the disappearance of infection in cervical smears25.

Our study group is under strict supervision, but observations made after more than a decade will undoubtedly be interesting. The question remains whether, in the future HPV- positive patients will experience a recurrence of SIL-type lesions in the cervix or lesions in the vagina and vulva.

Conclusions

Vaccination against HPV significantly affects the disappearance of the viral infection in women not vaccinated during puberty. A statistically significant disappearance of HPV infection occurs in patients both diagnosed with HPV and undergoing LEEP-conization due to HSIL. Vaccination of this group of women will probably reduce the occurrence of cervical, vaginal, and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and other HPV-related lesions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

The authors declare no conflict of interests.Conceptualization, D.P.; Methodology, D.P.; Software, D.P. and S.M.-K.; Formal analysis, S.M.-K. and D.P.; Investigation, D.P. and S.M.-K.; Resources, D.P. and M.P.; Data curation, D.P. and S.M.-K.; Writing—original draft, D.P. and S.M.-K.; Writing—review and editing, D.P., S.M.-K. and R.J.; Visualization, S.M.-K.; Supervision, M.P. and R.J.; Project administration, D.P.; Funding acquisition, D.P. and M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and the Supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in the author names and in the legend of Figure 1. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/11/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-025-02469-y

Contributor Information

Dominik Pruski, Email: dominik.pruski@icloud.com.

Sonja Millert-Kalińska, Email: millertsonja@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.. 74(3):229–263. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Pruski, D., Millert-Kalinska, S., Klemenska, P., Jach, R. & Przybylski, M. Clinical use of the onclarity test with extended HPV genotyping and phenotyping in patients with suspected squamous intraepithelial lesions. Ginekol. Pol.95 (5), 328–334. 10.5603/gpl.96712 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao, F. & Sui, L. Evaluation of a real-time optoelectronic method for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer in patients with different transformation zone types. Sci. Rep.14, 27220. 10.1038/s41598-024-78773-w (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue, P. et al. Deep learning in image-based breast and cervical cancer detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Npj Digit. Med.5, 19. 10.1038/s41746-022-00559-z (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kesic, V. et al. The European society of gynaecological oncology (ESGO), the international society for the study of vulvovaginal disease (ISSVD), the European college for the study of vulval disease (ECSVD), and the European federation for colposcopy (EFC) consensus statement on the management of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 33 (4), 446–461. 10.1136/ijgc-2022-004213 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan, J. et al. Increased risk of HPV-associated genital cancers in men and women as a consequence of pre-invasive disease. Int. J. Cancer. 145, 427–434 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strander, B., Hällgren, J. & Sparén, P. Effect of ageing on cervical or vaginal cancer in Swedish women previously treated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: population based cohort study of long term incidence and mortality. BMJ348, f7361 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Medicines Agency (EMA). Gardasil 9 Summary of Product Characteristics, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/gardasil-9-epar-product-information_en.pdf (Accessed 9 Sep 2020). (2020).

- 9.Merck, Sharp, Dohme, L. L. C., Rahway, N. J. & Gardasil®9, U. S. A. US Prescribing Information, https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/g/gardasil_9/gardasil_9_pi.pdf, (Accessed 9 Apr 2023). (2023).

- 10.Preti, M. et al. Risk of HPV-related extra-cervical cancers in women treated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. BMC Cancer. 20, 972. 10.1186/s12885-020-07452-6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rene ´e, M. F. et al. Long-Lasting increased risk of human Papillomavirus–Related carcinomas and premalignancies after cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: A Population-Based cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol.35, 2542–2550. 10.1200/JCO.2016 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kechagias, K. S. et al. Role of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on HPV infection and recurrence of HPV related disease after local surgical treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ378, e070135. 10.1136/bmj-2022-070135 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joura, E. A. et al. Efficacy of a quadrivalent prophylactic human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against high-grade vulval and vaginal lesions: a combined analysis of threerandomizedd clinical trials. Lancet 369(9574):1693 -1702.10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60777-6. (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Dehlendorff, C., Baandrup, L. & Kjaer, S. K. Real-World effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination against vulvovaginal High-Grade precancerous lesions and cancers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.113 (7), 869–874. 10.1093/jnci/djaa209 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mo, Y. et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic HPV vaccines: current scenario and perspectives. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.12, 909223 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eerkens, A. L. et al. Vvax001, a therapeutic vaccine for patients with HPV16-positive High-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a phase II trial. Clin. Cancer Res.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-24-1662 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Pruski, D. et al. Effect of HPV vaccination on virus disappearance in cervical samples of a cohort of HPV-Positive Polish patients. J. Clin. Med.12 (24), 7592. 10.3390/jcm12247592 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reuschenbach, M. et al. Prophylactic HPV vaccines in patients with HPV-associated diseases and cancer. Vaccine41 (42), 6194–6205 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joura, E. A. et al. Effect of the human papillomavirus (HPV) quadrivalent vaccine in a subgroup of women with cervical and vulvar disease: retrospective pooled analysis of trial data. BMJ344, e1401 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coskuner, E. R., Ozkan, T. A., Karakose, A., Dillioglugil, O. & Cevik, I. Impact of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine on disease recurrence in men exposed to HPV infection: arandomizedd study. J. Sex. Med.11, 2785–2791 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghelardi, A. et al. Surgical treatment of vulvar HSIL: adjuvant HPV vaccine reduces recurrent disease. Vaccines (Basel). 9 (2), 83. 10.3390/vaccines9020083 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksen, D. O., Jensen, P. T., Schroll, J. B. & Hammer, A. Human papillomavirus vaccination in women undergoing excisional treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and subsequent risk of recurrence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand.101 (6), 597–607. 10.1111/aogs.14359 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Donato, V. et al. HPV vaccination after primary treatment of HPV-Related disease across different organ sites: A multidisciplinary comprehensive review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 10 (2), 239. 10.3390/vaccines10020239 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharpless, K. E., Marcus, J. Z., Kuroki, L. M., Wiser, A. L. & Flowers, L. ASCCP committee opinion: adjuvant human papillomavirus vaccine for patients undergoing treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis.27 (1), 93–96. 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000703 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pruski, D. et al. Immunity after HPV vaccination in patients after sexual initiation. Vaccines (Basel). 10 (5), 728. 10.3390/vaccines10050728 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript and the Supplementary information files.