Abstract

Transplantation of corneal tissue is the standard treatment for irreversible corneal endothelium decompensation by replacing the malfunctioning corneal endothelial cells and Descemet’s membrane. However, this surgery depends on limited donor tissue supply. Thus, developing suitable alternatives for donor grafting material through a tissue engineering approach is needed to enable the transplantation of cultured endothelial cells to restore normal endothelial function. Here, we proposed using a plastic compressed collagen 3D matrix called Real Architecture For 3D Tissues (RAFT) as a scaffold for cell culture. The porcine cornea endothelial cells (PCECs) were seeded on RAFT to construct a tissue-engineered corneal endothelium. Then, the porcine cell-seeded-RAFT graft was transplanted onto a human cornea and maintained in an ex vivo organ culture model. The results showed that PCECs formed a high-density monolayer on RAFT expressing endothelial cell markers, ZO-1, Na/K ATPase and N-cadherin. More importantly, the cell-seeded RAFT transplantation successfully restored corneal endothelium function, drawing the thickness of endothelium-wounded cornea back to normal in two weeks of the ex vivo human cornea organ culture.

Subject terms: Translational research, Tissue engineering

Introduction

Cultured human corneal endothelial cell therapy has the potential to be the surrogate of endothelial transplantation for treating sight-threatening eye conditions, such as Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy1, post-keratoplasty endothelial decompensation2, or even virus-infected endothelial dysfunction3. While human corneal endothelial cells have very limited regenerative capacity in vivo, they can display increased capacity for proliferation in vitro, albeit also restricted4. Cell-based therapy and tissue engineering could substitute for native tissue to ease the shortage of donor corneas by transplanting cultured endothelial cells to restore normal endothelial function5,6.

For the application of cell therapy in treating corneal endothelial diseases, the cultured cells are either directly injected into the anterior chamber or transplanted through a cell carrier. The concept of injecting cell suspension into the anterior chamber was introduced years ago, where the endothelial cells were able to repopulate and self-organize on the posterior surface of the cornea; meanwhile, possessing pumping function to maintain normal corneal thickness7,8. Recently, the first clinical trial of endothelial cell injection therapy was conducted by injecting endothelial cell suspension into the anterior chamber with ROCK inhibitor for treating bullous keratopathy9. The results showed that normal corneal endothelial function was restored with visual acuity improvement in 10 of 11 eyes, and the mean cell density was 1257 cells/mm210. However, the success of seeding cell suspension into the anterior chamber relied on the presence of the recipient’s Descemet membrane (DM) to promote cell attachment. In the clinical trial, the endothelial cells were scraped with a silicone tip needle but left behind the abnormal DM. Thus, the deposits of guttae on the DM still existed at 5 years of follow-up10. Long-term observation might still be needed to see if the abnormal DM will affect the re-populated endothelial cells.

Transplantation of cell sheets potentially outweighs injecting cell suspension as it not only replaces the diseased cells but also removes the underlying abnormal DM. The difficulty of cell sheet transplantation is that the cultured cells require a suitable cell carrier for delivery, which needs to be transparent and stiff enough for surgical handling. Numerous scaffold materials have been proposed and used in animal experiments to test if it is a suitable cell carrier for delivering cultured endothelial cells, including collagen11,12, gelatin13–15, human corneal stroma disc16, and decellularised human corneal stroma disc17,18. Published results showed that tissue-engineered cell sheets were able to attach to the posterior surface of the cornea, expressed endothelial cell markers and functioned properly to maintain a normal cornea thickness in the animal model19.

Here, we proposed using Real Architecture For 3D Tissues (RAFT) to create compressed collagen I hydrogel, whose translucent and strong properties are suitable for corneal tissue engineering and carrying cells for transplantation20,21. The compressed collagen I hydrogel can substitute for the stroma to support the single-cell layer of the endothelium, like the endothelial keratoplasty (EK) graft. Our published results have shown that cultured human corneal endothelial cells formed a high cell density monolayer on an early prototype of RAFT and expressed the endothelial cell markers ZO-1 and Na/K ATPase22. However, none of these studies used human corneas as recipients to test the feasibility of cell sheet transplantation to evaluate the tissue-engineered graft’s endothelial function.

Recently, an ex vivo human corneal endothelium wound model was established by mounting human corneal tissue in an artificial anterior chamber infusion organ culture system, where corneal endothelium function can be evaluated by the corneal thickness changes. The endothelium wound model showed a thickened and swelling cornea, which was able to simulate the clinical manifestation of endothelial decompensation23. This model is an alternative to the animal model for assessing cell therapy transplantation. In the present study, a tissue-engineered corneal endothelium was developed by seeding PCECs onto RAFT. Then, the porcine cell-seeded RAFT graft was transplanted into the ex vivo human corneal endothelium wound model to investigate if the cultured cell sheet can attach to the recipient’s cornea and restore endothelium function.

Results

PCECs formed a high cell density monolayer expressing endothelial cell markers ZO-1, NA/K ATPase, and N-cadherin on RAFT graft

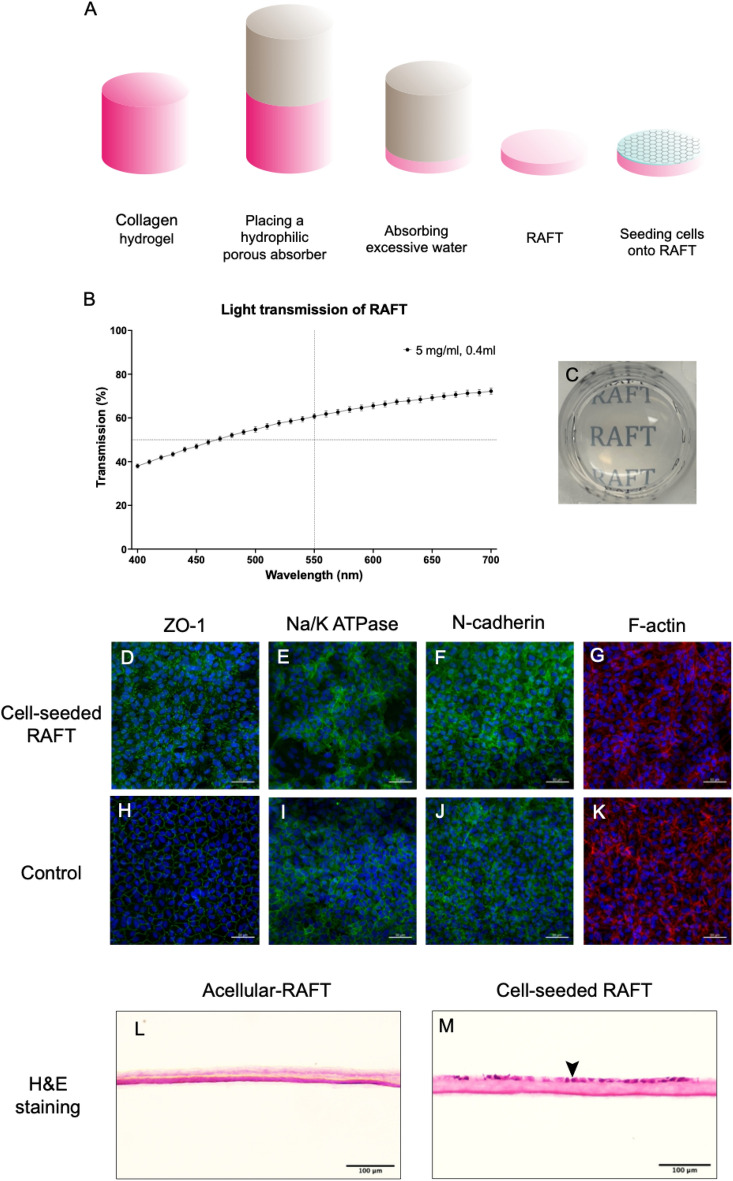

A tissue-engineered corneal endothelium was developed by seeding PCECs on 5 mg/ml, 0.4 ml, RAFT to construct a porcine cell-seeded-RAFT graft for transplantation. The RAFT was translucent, with 60.71 ± 1.17% light transmittance at 550 nm. The immunostaining results showed that PCECs formed a confluent monolayer on the surface of RAFT. Cells expressed continuous ZO-1 at the cell borders and showed organized F-actin filaments in a polygonal shape. Cells also expressed Na/K ATP and N-cadherin at the cell borders and the cell membrane, displaying the polygonal shape of endothelial cells. The RAFT formed a compressed, homogenous, and dense collagen hydrogel. Cross-sectional H&E staining showed that cells formed a confluent monolayer of endothelial cells on the surface of the RAFT (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence and cross-sectional H&E staining of porcine cell-seeded-RAFT (A) Schematic diagram showing that excessive hydrogel water was wicking into the absorber to produce RAFT. After that, PCECs were seeded on RAFT (0.4 ml of 5 mg/ml collagen I) coated with collagen IV and culture for 7 days to construct a porcine cell-seeded-RAFT. (B) The light transmission of RAFT across wavelengths from 400 to 700 nm, n = 3 biological replicates. (C) Camera image of RAFT in a 24-well plate. (D, H) Immunofluorescence staining results showed the expression of ZO-1, Na/K ATPase, N-Cadherin and F-actin on RAFT and control. The control was PCECs seeded on a round glass cover slip at the same seeding density as on the cell-seeded RAFT. Continuous expression of ZO-1 was observed at the cell–cell borders on RAFT and control. (E, I) The expression of Na/K ATP at the cell borders and cell membrane on RAFT and control. (F, J) The expression of N-Cadherin at the cell borders and cell membrane on RAFT and control. (G, K) The expression of F-actin filaments showed the polygonal shape of cells on RAFT and control. Images are representative of n = 3 biological replicates. Scale bar = 50 µm. (L) The cross-sectional H&E staining showed that RAFT was a compressed, homogenous, and dense collagen hydrogel. (M) PCECs formed a mono-cell layer on the surface of the cell-seeded-RAFT (➤). Images are representative of n = 3 biological replicates. Scale bar = 100 µm.

The corneal thickness of the endothelium wound cornea was decreased after RAFT transplantation

Three pairs of human corneas were used in this experiment (n = 3 biological replicates). The corneal endothelial wound was prepared by manually peeling the central 8.5 mm DM and endothelium. RAFT was trephined as an 8.25 graft for RAFT transplantation. The recipient corneas were maintained in the ex vivo organ culture model for two weeks (Fig. 2A). Following RAFT graft transplantation, the recipient cornea thickness was significantly lower in the cell-seeded-RAFT group than in the acellular RAFT group. The initial corneal thickness for the acellular RAFT group and the cell-seeded-RAFT group were 915.20 ± 46.1 µm and 926.27 ± 30.17 µm, respectively.

Fig. 2.

RAFT transplantation in an ex vivo human cornea organ culture model (A) The diagram illustrates the experimental design of RAFT transplantation. (B) The corneal thickness was significantly decreased after cell-seeded RAFT transplantation compared to acellular RAFT transplantation. The mean corneal thickness difference between the cell-seeded-RAFT group and the acellular RAFT group was 82.57 ± 15.62 µm, with a significant difference of p < 0.05. Three pairs of donor corneas were used in this experiment (n = 3 biological replicates). The donor’s age and gender were 77 y/o female, 72 y/o male, and 78 y/o female. (C) The recipient cornea remained cloudy on day 14 after RAFT transplantation with an acellular graft. The cornea showed irregular light reflection on the cornea surface. (D) The stroma oedema of the recipient subsided after 14 days of the cell-seeded-RAFT transplantation. The cornea showed regular light reflection on the surface, and the RAFT graft also became transparent. Images are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

On day 2, the corneal thickness was decreased in both groups at 733.27 ± 34.94 µm in the acellular RAFT group and at 673.86 ± 49.83 µm in the cell-seeded-RAFT group with significant difference in the corneal thickness (p < 0.05). After that, the corneal thickness of the cell-seeded-RAFT group was maintained in lower thickness figures from 666.47 ± 62.39 µm on day 4 to 641.6 ± 57.00 µm on day 14. On the contrary, the corneal thickness of the acellular RAFT group was significantly thicker than the corneal thickness of the cell-seeded-RAFT group, from 739.27 ± 42.58 µm at day 4 to 752.87 ± 48.87 µm at day 14. Overall, the mean corneal thickness difference between the cell-seeded-RAFT group and the acellular RAFT group was 82.57 ± 15.62 µm, which was significantly different (p < 0.05; Fig. 2B).

From the camera images, the cornea stromal oedema subsided for the cell-seeded RAFT transplantation, while the cornea remained cloudy for the acellular RAFT transplantation. The middle of the cell-seeded-RAFT graft also became transparent, compared to acellular RAFT graft (Fig. 2C, D).

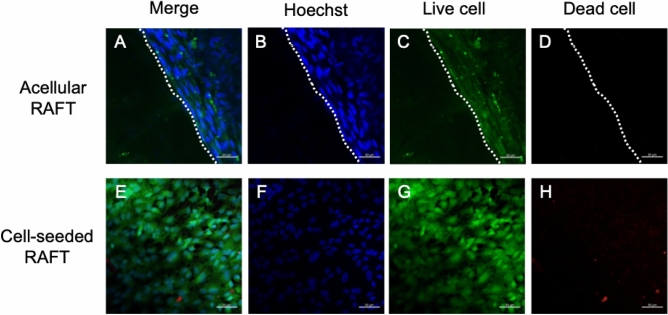

Endothelial cells on the RAFT graft remained alive after 14 days of RAFT transplantation

At the end of the organ culture, corneas were stained with Live/Dead assay to visualise the cell viability on RAFT grafts after RAFT transplantation. For the cell-seeded-RAFT group, most endothelial cells were still alive after 14 days of RAFT transplantation, showing a round cell nucleus, small cell size and compact cell arrangement. No cells were observed on the acellular RAFT graft, and no cells migrated onto the graft (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Live/Dead cell viability assay of RAFT following transplantation (A–D) There were no cells on the acellular RAFT graft. The border of the graft was indicated by the dashed line to show that no cells migrated onto the graft. (E–H) Cells on the cell-seeded-RAFT graft remained alive after 14 days of RAFT transplantation. Images are representative of n = 3 biological replicates. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Endothelial cells on RAFT graft expressed endothelial cell markers, ZO-1 and Na/K ATPase after 14 days of RAFT transplantation

After 14 days of RAFT transplantation, both groups of the corneas were taken out of the ex vivo model for endothelial cell marker staining (ZO-1 and Na/K ATPase). There were no cells on the acellular RAFT graft and no ZO-1 and Na/K ATPase expression on the acellular RAFT graft. After transplantation, no cell migration or cell infiltration was observed on the acellular RAFT graft. For the cell-seeded-RAFT graft, cells on the graft showed a polygonal cell shape, expressing continuous ZO-1 on the cell–cell borders with compact cell arrangement (Fig. 4A,D). Similar results were also observed in Na/K ATPase staining. Cells expressed Na/K ATPase on the cell–cell borders, retaining close cell–cell contact with a high cell density of around 3000 cells/mm2 (Fig. 4B,E).

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescence and cross-sectional H&E staining following 14 days of RAFT transplantation. (A, B) There were no cells on the acellular RAFT graft and no cells expressing ZO-1 and Na/K ATP on the cell–cell borders. (C) The cross-sectional H&E staining showed that an acellular RAFT graft (❖) was attached to the posterior surface of the cornea, and no cells grew on the graft. (D, E) Cells on the cell-seeded-RAFT graft expressed Na/K ATPase on the cell–cell borders, retaining close cell–cell contact with a high cell density. (F) A monolayer of endothelial cells (▲) was observed on the surface of the cell-seeded-RAFT graft (✱). Images are representative of n = 3 biological replicates. Scale bar = 50 µm for the immunostaining images. Scale bar = 100 µm for the cross-sectional H&E staining images.

RAFT grafts were attached to the posterior surface of the cornea and maintained a monolayer of endothelial cells post-RAFT transplantation. The histological observation was conducted after 14 days of RAFT transplantation. Both RAFT grafts were attached to the posterior surface of the recipient cornea, as shown by H&E staining. Endothelial cells maintained a monolayer on the cell-seeded-RAFT graft, while cells were found in the interface between the graft and the recipient’s posterior stroma (Fig. 4C,F).

Discussion

PCECs were successfully seeded on the surface of the RAFT to form a high-density cell monolayer useful for constructing a tissue-engineered corneal endothelium. The cell viability assay showed that most PCECs remained alive after 7 days of cell culture, even though a few cell defects were observed. PCECs culture on RAFTs showed immunofluorescent expression of tight junction protein ZO-1 on the cell–cell border and the active transport pump Na/K ATPase on the cell membrane and cell border. These results are in line with previous studies that human corneal endothelial cells and immortal cell lines grown on preliminary RAFT showed a compact cobblestone cellular morphology and expressed the corneal endothelial cell markers, ZO-1 and Na/K ATPase22.

To evaluate the feasibility of transplanting a tissue-engineered corneal endothelium into the novel human ex vivo model and its subsequent ability to maintain a normal corneal thickness, PCEC cell-seeded RAFT grafts were transplanted into the ex vivo human endothelium wound model as a surrogate for treating endothelium decompensation. Corneal thickness post-RAFT transplantation was used to assess the graft’s endothelium pumping function. The results showed that the corneal thickness significantly decreased after the cell-seeded RAFT transplantation compared to acellular RAFT transplantation. This indicated that a transplanted cell-seeded RAFT graft successfully re-established an endothelium and functioned properly to pump water out of the swelling cornea stroma. Also, immunostaining showed that cells on the cell-seeded graft were still alive and expressed endothelial cell markers ZO-1 and Na/K ATPase markers post RAFT transplantation. Cross-sectional H&E staining showed that the RAFT graft attached to the posterior surface of the cornea and the collagen fibres of the RAFT were integrated into the recipient’s posterior stroma.

The immunostaining results for ZO-1 and Na/K ATPase indicated the endothelial cell boundaries on the graft after RAFT transplantation. The cell boundaries became less organised and blurred, which may relate to the serum concentration of the culture medium and the cell interactions between the recipient’s stromal cells and the graft’s endothelial cells. The cell-seeded graft was prepared by seeding porcine corneal endothelial cells on RAFT, which were then cultured and maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS. While the high serum culture medium is suitable for culturing porcine endothelial cells in vitro, it may not be suitable for human stromal cells. Previous research has shown that removing the DM exposes the keratocyte to the culture medium, and its growth factors may activate the keratocytes to transform into myofibroblasts23,24. In the present study, although the wound area was covered by the RAFT graft after transplantation, growth factors within the culture medium could still contact the recipient’s keratocytes and induce cell differentiation. This differentiation can interact with the graft’s endothelial cells, leading to cell morphology changes. Future optimisation of the culture medium may improve the cell morphology and the endothelial pumping function on the graft, such as using primary human corneal endothelial cells for the graft preparation and maintaining them in the serum-reduced M5 culture medium for extending the barrier and pump function of the endothelium25. Another possible explanation for the changes in cell morphology on the graft might have something to do with an indirect immune reaction. The alloantigen travels from the graft to the recipient and is captured by the recipient’s antigen-presenting cells (APCs)26,27. Corneal APCs primarily reside in the peripheral cornea, including epithelial Langerhans cells and anterior stromal dendritic cells28. Recently, APCs have also been found in the posterior stroma expressing macrophage cell markers CD11c+ CD11b+29. The APCs in the posterior recipient’s stroma may sense antigens derived from the graft, triggering an immune reaction that might influence the cells on the graft. If that is so, this indicates that the APC within the cadaver human cornea stroma can still be activated to induce an immune reaction in the ex vivo organ culture model. More studies are needed to shed light on cell interactions between posterior stromal cells and endothelial cells in the ex vivo organ culture model.

Previous work has shown that acellular RAFT was able to be folded and delivered into the anterior chamber of an ex vivo pig eyeball, indicating that RAFT has sufficient mechanical strength as a suitable cell carrier for the EK surgical procedure22. However, whether cell-seeded-RAFT can also be delivered onto the posterior surface of the cornea without damaging the cells remained unknown. In the current study, a cell-seeded-RAFT was trephined as a cellular graft and was transplanted onto the ex vivo human corneal endothelium wound model by using the EndoGlide insertion technique. Endoglide is a graft insertion device widely used in Descemet’s Stripping Endothelial Automated Keratoplasty (DSEAK) and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). The device consists of a preparation base, a glide cartridge and a glide introducer, allowing the graft to be folded into a double-coiled tube shape to minimise endothelial cell loss during the transfer30,31. Like the use of Endoglide in DSEAK graft, the cell-seeded-RAFT was able to be folded into the double-coil configuration when being pulled into the cartridge of the Endoglide. The cell viability results showed a high cell density of live PCECs was observed on RAFT after 14 days of transplantation without noticeable cell loss. Our results showed that Endoglide is a suitable graft-delivering device for tissue-engineered corneal endothelium used in DSEAK surgical procedures.

Cell therapy is an alternative to EK surgery (e.g., DSEAK) for treating endothelium dysfunction by injecting cultured cell suspension into the anterior chamber7,8,32 or transplanting cultured cell sheets onto the posterior surface of the cornea11,18,33. Recently, Kinoshita et al. published a promising result of the first clinical trial of endothelial cell injection therapy for treating bullous keratopathy9, which showed that normal corneal endothelial function was restored with visual acuity improvement in 10 of 11 eyes with the mean endothelial cell density of 1257 cell/mm2 at five years after cell injection10. One of the drawbacks of cell injection is that the success of seeding cell suspension into the anterior chamber relies on the presence of the recipient’s DM to promote cell attachment18. However, abnormal ECM secretion from Fuchs corneal endothelial dystrophy can also be deposited in the DM. Preserving the abnormal DM might pose a potential threat to the re-populated endothelial cells in the long term.

Transplantation of a tissue-engineered corneal endothelium following the standard EK surgery technique not only replaces the diseased endothelial cells but also removes the underlying abnormal DM11,19. In the current study, endothelial cell-seeded RAFT was transplanted into the ex vivo endothelium wounded model (peeling of DM and endothelium of a cadaver human cornea) for testing the feasibility and functionality of tissue-engineering cell therapy. The results showed that the transplanted cell-seeded RAFT graft successfully re-established an endothelium and functioned properly to pump water out of the swelling cadaver human cornea in the ex vivo organ culture model. Also, the cell-seeded RAFT graft was able to be folded into the double-coil configuration in the Endoglide (a widely used graft insertion device in DSAEK) without noticeable cell loss during cell transfer. Like previous research, our results present a proof of concept for transplanting cultured cell sheets in the treatment of endothelial dysfunction. The endothelium-wounded cornea showed corneal oedema at the beginning of the experiment, but the corneal oedema subsided after cell-seeded RAFT transplantation. The cell-seeded RAFT successfully re-established the endothelium cell barrier function to reduce the corneal thickness on day 2. Moreover, our study builds on others in that the use of cadaver human corneas as the recipients for receiving the tissue-engineered graft may make our study more comparable to the published in vivo cell therapy studies. For example, after cell-seeded RAFT transplantation, the recipient’s corneal thickness was decreased and then maintained at around 650 µm for 14 days in our model. This figure is close to the corneal thickness changes after cell injection in the results of the published clinical trial9.

This indicated that our ex vivo organ culture model could mimic the in vivo corneal thickness changes post-cell therapy transplantation. Moreover, the cell-seeded graft became more transparent than the acellular graft on day 14. The cultured PCECs were able to resume endothelial pump function, not only pumping water out of the recipient cornea but also removing water out of the RAFT to restore the clarity of the recipient cornea and the graft. The cultured PCECs seeded on RAFT were able to express endothelial cell markers and meanwhile possess normal endothelial function. This suggested that inserting a tissue-engineered graft for transplantation might be a feasible and practical cell therapy treatment for endothelium decompensation.

Conclusion

In summary, PCECs formed a high-cell-density monolayer on the surface of RAFT to construct a tissue-engineered corneal endothelium. This tissue-engineered cell-seeded-RAFT could be an alternative to the EK graft for transplantation. The ex vivo RAFT transplantation showed proof-of-concept results of the possibility of endothelial cell therapy by treating endothelial dysfunction with a cell-seeded RAFT graft. Furthermore, the results supported the hypothesis that the cells transplanted on RAFT could re-establish a functional corneal endothelium to reduce cornea thickness in endothelial wounded corneas.

Methods

Consent statement of research-grade human cornea tissues

This research project was approved by The Moorfields Biobank Internal Ethics Committee, UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, South West–Central Bristol Research Ethics Committee (Ethics reference 20/SW/0031; Moorfields Biobank reference: 10/H0106/57-2011ETR10). All human cornea tissues were obtained from the National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT). All participants have provided written informed consent for research studies. All research performed with human-derived tissue was carried out in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Human cornea preparation

Corneas unsuitable for clinical transplantation were discarded and transferred for research use. The blood tests of all the donors were negative for HIV, HTLV, syphilis, HBV, HCV, and HEV. For ex vivo model experiments, human corneas were briefly washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 1% Antibiotic–Antimycotic( AA; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The donors were 77-year-old females, 72-year-old males, and 78-year-old females.

Porcine cornea preparation

Porcine eyeballs from 6 to 8-month-old pigs were obtained from local abattoirs within 4 h of extraction and transported to the laboratory on ice. Extraocular muscle, connective tissue, and conjunctiva were removed, followed by washing with DPBS without calcium and magnesium and containing 1% AA. Then, the eyeballs were submerged in 2% Povidone-Iodine solution for 2 min and rinsed with DPBS containing 1% AA for 1 min. The corneas were excised from the eyeballs with a 17 mm trephine and briefly washed with DPBS containing 1% AA before primary cell culture.

Porcine corneal endothelial cell (PCEC) isolation and culture

The corneas were placed endothelial side up on a 7 ml Bijou cap and incubated with 300 μl of Dispase II (1.2 U/ml; Roche, UK) at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, corneal endothelial cells were disaggregated into the solution by gentle scraping with a scleral golf knife (Altomed, UK). After being centrifuged for 5 min at 400 g, cells were re-suspended in endothelial culture medium consisting of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with high glucose (4.5 g/L), GlutaMAXTM (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% AA. The PCECs obtained from individual corneas were plated in an individual well of a 12-well plate. Cells were maintained at 37 °C, with 5% CO2 in air until confluent. Cell culture medium changes were carried out every other day. Cell growth and morphology changes were monitored under a phase contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope with a Nikon DS-L2 digital camera).

PCECs reached confluence in 7–8 days. Primary cell cultures were designated as passage 0 (P0). For sub-culturing and seeding for experiments, PCECs were washed with DPBS without calcium and magnesium before being incubated with TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in air. Upon cell detachment, cells were re-suspended in endothelial culture medium. Then, PCECs were pelleted by centrifugation at 400 g for 5 min and counted for plating in a T25 flask coated with FNC at a seeding density of 10,000 cells/cm2.

Ex vivo anterior chamber infusion model

The method of setting up an ex vivo anterior chamber infusion model was published elsewhere23. Human cornea tissue was briefly washed with DPBS before being mounted onto the platform of the artificial anterior chamber (Barron, USA). The cornea was positioned in the centre of the platform and locked with a tissue retainer to create a closed chamber for culture medium infusion. There were two ports on the base of the chamber, allowing the culture medium to flow in and out. The inlet and outlet of the ports were connected to a peristaltic pump (100 µl/min), and a culture medium reservoir bottle was connected to the artificial anterior chamber to complete the flow circuit. Also, a 0.2 µm filter was attached to the reservoir bottle to enable air exchange and equalise internal and external pressures. The upper medium container contained the epithelium culture medium (1:1 ratio of DMEM high glucose: F12, 10% FBS, and 1% AA). The reservoir bottle contained the endothelium culture medium (DMEM high glucose, 10% FBS, and 1% AA) (Fig. 5). The ex vivo anterior chamber infusion model was placed on a 3D orbital rotating shaker in the incubator at 37 °C, with 5% CO2 in the air. The culture medium was changed every other day.

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of the ex vivo anterior chamber infusion model. This infusion model comprises a reservoir bottle, a peristaltic pump, and an artificial anterior chamber. The anterior chamber infusion system uses a peristaltic pump to create a flow so the culture medium can flow back to the culture medium reservoir bottle. The arrowhead (➤) indicates the direction of the culture medium flow. Cornea tissue is mounted on the anterior chamber and locked with a tissue retainer to create a closed chamber for culture medium infusion. The inlet and outlet of the ports were connected to a peristaltic pump (100 µl/min) and a culture medium reservoir bottle with connecting tubing to complete the flow circuit. A 0.2 µm filter was attached to the reservoir bottle to enable air exchange.

Preparation of collagen hydrogel and construction of Real Architecture For 3D Tissue (RAFT)

Collagen gel solution was prepared on ice by mixing 80% soluble bovine dermis type I collagen 5 mg/ml (Koken, Japan), 10% 10X Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK), 3% neutralising solution consisting of 0.325 M sodium hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) and 7% endothelial culture medium. The collagen gel solution was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 3 min to remove small bubbles and then kept on ice for 30 min to disperse any further air bubbles. This mixture was then pipetted in 400 µl volumes into individual wells of a 24-well plate (Greiner Bio-One) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to allow fibrillogenesis for collagen hydrogel formation. To construct a RAFT tissue equivalent, a hydrophilic porous absorber (Lonza) was placed on each collagen hydrogel for 30 min at room temperature to remove most of the fluid and to increase the collagen density. After removing the excess water from the hydrogel, 0.5 ml of DPBS was added to the RAFT to prevent dehydration. RAFT was stored at 4 °C in DPBS for up to 1 day for experiments.

Light transmission measurements of RAFT

The light transmission of RAFTs was measured with a spectrophotometer (SAFIRE, Tecan, Reading, UK). In brief, RAFTs were immersed in 1 ml of Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the light absorbance was assessed with wavelength ranging from 400 to 700 nm. A well containing 1 ml of PBS alone was used as a control. Absorbance readings were converted to transmission percentage with the formula as light transmission (%) = 10 − absorbance × 100. Three samples were measured to calculate the mean and standard deviation.

Cell-seeded RAFT graft preparation

P2 PCECs were seeded on RAFTs coated with collagen IV (50 µg/ml; Sigma, UK) at a seeding density of 300,000 cells/RAFT. Cell-seeded-RAFT was maintained in endothelial culture medium and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in air. Acellular RAFT coated with collagen IV (50 ng/ml) was prepared with no cells seeded onto it. The acellular RAFT was maintained in DPBS at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in air. Cell-seeded-RAFT and acellular RAFT were trephined as 8.25 mm RAFT grafts for RAFT transplantation.

Surgical procedure of ex vivo RAFT transplantation

Human corneas from the same donors were divided into the cell-seeded-RAFT transplantation group and the acellular RAFT transplantation group. An 8.25 mm RAFT graft was taken out of the 24-well plate and placed onto the donor well of the EndoGlide Ultrathin (Coronet, UK). Viscoelastic product sodium hyaluronate (Bausch & Lomb, UK) was applied on the surface of the graft to protect endothelial cells during the transfer. Then, the graft was pulled into the cartridge using loading forceps (Coronet, UK). The cartridge was then transferred to the 8.5 mm wounded recipient cornea. The graft was pulled out from the cartridge and placed in the middle of the wound area. Residual viscoelastic was washed out with DPBS. Finally, the recipient cornea was mounted onto the ex vivo anterior chamber infusion model and connected to the pumping system for organ culture. Corneal thickness was measured every other day to evaluate graft function. At the end of the experiment, cornea tissue with transplanted RAFT grafts was taken out of the model and used for H&E and immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

RAFT transplantation. Representative pictures show the RAFT transplantation process in the ex vivo human anterior chamber infusion model. (A) RAFT was trephined as an 8.25 mm graft for transplantation and transferred onto the donor well of the EndoGlide Ultrathin. A small amount of the viscoelastic product was applied on the surface of the RAFT graft to protect endothelial cells during the transfer. (B) The graft was pulled into the cartridge using loading forceps. (C) The cartridge was attached to a loading handle. (D) The cartridge was transferred to the recipient cornea with endothelium face up. (E) The graft was pulled out of the cartridge. (F) The graft was unfolded and placed in the middle of the wound area. The residual viscoelastic product was washed out with DPBS. (G) The front view of the recipient cornea with transplanted graft. A dashed circular line indicates the graft on the posterior surface of the cornea. (H) The recipient cornea was mounted onto the ex vivo anterior chamber infusion model and connected to the pumping system for organ culture at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in air.

Cornea thickness measurement

The central corneal thickness was measured using an ultrasonic handheld pachymeter (P-1 pachymetry, Takagi, Japan) at a speed of sound at 1640 m/s. Five applications were carried out for each cornea, and the individual measurements were recorded. The corneal thickness was measured every other day until the end of the experiment.

Live/dead cell viability staining of the flat-mounted cornea

Corneas were cut into four or six pie-shaped wedges for preparation. The corneas were washed with DPBS three times and incubated with DPBS containing Live/Dead viability kit reagent (2 μM Calcein AM and 4 μM Ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature. The corneas were placed on glass slides covered with DPBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then gently flattened using a rectangular coverslip. Fluorescent cell images were captured within 1 h using ZEN Blue software connected to an LSM 700 confocal microscope (Zeiss) operating at wavelengths of 526 nm for Calcein AM and 613 nm for EthD-1.

Flat-mounted immunofluorescence staining

Corneas were cut into four or six pie-shaped wedges and rinsed with DPBS before staining. The corneas were washed with DPBS before being fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution (NBF; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at room temperature and permeabilised in 0.25% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS for 5 min at room temperature. The non-specific binding sites were then blocked in DPBS containing 5% heat-inactivated goat serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at 37 °C. The primary mouse anti-ZO-1 antibody (339,100, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was diluted in DPBS at 1:200 and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The primary mouse anti-Na/K ATPase antibody (M7-PB-E9, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was diluted in DPBS at 1:100 and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was diluted at 1:500 in DPBS and incubated with the cells for 1 h at 37 °C. F-actin was stained with Alexa Fluor 594 phalloidin (A12381, Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in DPBS at 1:400 and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Cell nuclei were finally counterstained with Hoechst 33,342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted at 1:1000 in DPBS for 15 min at room temperature. Three rinses in DPBS were performed between all steps, except the steps between blocking non-specific protein binding sites and incubating with primary antibody. The corneas were mounted with slow fade glass mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and covered with a coverslip. Fluorescent images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope with ZEN Blue software.

Cryosection staining

RAFTs and the corneas were rinsed with DPBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight. Then, the sample was cryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4 °C overnight before being embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT; VWR, UK) and transferred on dry ice until the OCT became frozen. The sample containing the OCT block was stored at − 80 °C until further use. Embedded sample blocks were serially sectioned at 7 μm using a Leica CM1850 cryostat (Leica) and transferred onto SuperFrost Plus adhesion microscope slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The slides were air dried at room temperature for at least 1 h and then stored at − 80 °C.

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

Haematoxylin and eosin staining were conducted using kit reagents (Vector, UK). Frozen tissue sections were thawed at room temperature for 30 min and then stained in Mayer’s haematoxylin solution for 5 min. The sections were washed with distilled water twice (15 s each) before staining with Bluing Reagent for 15 s. Following two washes with distilled water (15 s each), the sections were dipped in 100% ethanol for 10 s. After that, the sections were stained with Eosin Y Solution for 3 min, rinsed with 100% ethanol for 10 s, and dehydrated in 3 changes of 100% ethanol (2 min each). Finally, the sections were covered with Canada balsam (Sigma Aldrich). Section images were captured using an EVOS™ XL Core Imaging System (ThermoFisher, UK).

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.0 for macOS (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA) with one-way or two-way ANOVA and Turkey multiple comparisons test. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) Tissue and Eye services in obtaining consent and providing the tissue (corneas) from UK donors.

Author contributions

Conception, study design, conducting experiment and drafting of the manuscript: M.C.T Revising and final approval of the version to be published: A.K and J.T.D.

Data availability

All the relevant data are presented in the manuscript. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fu, L. & Hollick, E. J. Long-term outcomes of descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty: Ten-year graft survival and endothelial cell loss. Am. J. Ophthalmol.234, 215–222. 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.08.005 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anshu, A., Price, M. O. & Price, F. W. Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty under failed penetrating Keratoplasty: Visual rehabilitation and graft survival rate. Ophthalmology118, 2155–2160. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.04.032 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang, M., Sng, C. C., Chee, S. P., Tan, D. T. & Mehta, J. S. Outcomes of corneal transplantation for irreversible corneal decompensation secondary to corneal endotheliitis in Asian eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol.156, 260-266.e262. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.03.020 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyce, N. C. Proliferative capacity of corneal endothelial cells. Exp. Eye Res.95, 16–23. 10.1016/j.exer.2011.08.014 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faye, P. A. et al. Focus on cell therapy to treat corneal endothelial diseases. Exp. Eye Res.204, 108462. 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108462 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodríguez-Fernández, S. et al. Current development of alternative treatments for endothelial decompensation: Cell-based therapy. Exp. Eye Res.207, 108560. 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108560 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mimura, T. et al. Magnetic attraction of iron-endocytosed corneal endothelial cells to Descemet’s membrane. Exp. Eye Res.76, 745–751. 10.1016/S0014-4835(03)00057-5 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, K. H., Azar, D. & Joyce, N. C. Transplantation of adult human corneal endothelium ex vivo: A morphologic study. Cornea20, 731–737 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinoshita, S. et al. Injection of cultured cells with a ROCK inhibitor for bullous keratopathy. N. Engl. J. Med.378, 995–1003. 10.1056/NEJMoa1712770 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Numa, K. et al. Five-year follow-up of first 11 patients undergoing injection of cultured corneal endothelial cells for corneal endothelial failure. Ophthalmology128, 504–514. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.09.002 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mimura, T. et al. Cultured human corneal endothelial cell transplantation with a collagen sheet in a rabbit model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.45, 2992–2997. 10.1167/iovs.03-1174 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi, M. et al. Optimization of cultured human corneal endothelial cell sheet transplantation and post-operative sheet evaluation in a rabbit model. Curr. Eye Res.41, 1178–1184. 10.3109/02713683.2015.1101774 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai, J. Y., Chen, K. H. & Hsiue, G. H. Tissue-engineered human corneal endothelial cell sheet transplantation in a rabbit model using functional biomaterials. Transplantation84, 1222–1232. 10.1097/01.tp.0000287336.09848.39 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsiue, G. H., Lai, J. Y., Chen, K. H. & Hsu, W. M. A novel strategy for corneal endothelial reconstruction with a bioengineered cell sheet. Transplantation81, 473–476. 10.1097/01.tp.0000194864.13539.2c (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niu, G. et al. Heparin-modified gelatin scaffolds for human corneal endothelial cell transplantation. Biomaterials35, 4005–4014. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.033 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda, N., Mimura, T., Usui, T. & Amano, S. Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty using cultured corneal endothelial cells in a rabbit model. Arch. Ophthalmol.127, 1321–1326. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.253 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peh, G. S. L. et al. Functional evaluation of two corneal endothelial cell-based therapies: Tissue-engineered construct and cell injection. Sci. Rep.9, 6087. 10.1038/s41598-019-42493-3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peh, G. S. L. et al. Regulatory compliant tissue-engineered human corneal endothelial grafts restore corneal function of rabbits with bullous keratopathy. Sci. Rep.7, 14149. 10.1038/s41598-017-14723-z (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mimura, T., Yamagami, S. & Amano, S. Corneal endothelial regeneration and tissue engineering. Prog. Retin. Eye Res.35, 1–17. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.01.003 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levis, H. J. et al. Tissue engineering the cornea: The evolution of RAFT. J. Funct. Biomater.6, 50–65. 10.3390/jfb6010050 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massie, I., Kureshi, A. K., Schrader, S., Shortt, A. J. & Daniels, J. T. Optimization of optical and mechanical properties of real architecture for 3-dimensional tissue equivalents: Towards treatment of limbal epithelial stem cell deficiency. Acta Biomater.24, 241–250. 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.06.007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levis, H. J. et al. Plastic compressed collagen as a novel carrier for expanded human corneal endothelial cells for transplantation. PLoS ONE7, e50993. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050993 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai, M.-C., Kureshi, A. & Daniels, J. T. Establishment of an Ex vivo human corneal endothelium wound model. Translat. Vision Sci. Technol.14, 24–24. 10.1167/tvst.14.1.24 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medeiros, C. S., Marino, G. K., Santhiago, M. R. & Wilson, S. E. The corneal basement membranes and stromal fibrosis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.59, 4044–4053. 10.1167/iovs.18-24428 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frausto, R. F. et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of corneal endothelial cells during in vitro expansion. Sci. Rep.10, 7402. 10.1038/s41598-020-64311-x (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dietrich, T. et al. Cutting edge: Lymphatic vessels, not blood vessels, primarily mediate immune rejections after transplantation. J. Immunol.184, 535–539. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903180 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hos, D. et al. Immune reactions after modern lamellar (DALK, DSAEK, DMEK) versus conventional penetrating corneal transplantation. Prog. Retin. Eye Res.73, 100768. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.07.001 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamrah, P. & Dana, M. R. Corneal antigen-presenting cells. Chem. Immunol. Allergy92, 58–70. 10.1159/000099254 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamrah, P., Liu, Y., Zhang, Q. & Dana, M. R. The Corneal stroma is endowed with a significant number of resident dendritic cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.44, 581–589. 10.1167/iovs.02-0838 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khor, W.-B., Mehta, J. S. & Tan, D.T.-H. Descemet stripping automated endothelial Keratoplasty with a graft insertion device: Surgical technique and early clinical results. Am. J. Ophthalmol.151, 223-232.e222. 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.027 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gangwani, V., Obi, A. & Hollick, E. J. A prospective study comparing endoglide and busin glide insertion techniques in descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty. Am. J. Ophthalmol.153, 38-43.e31. 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.06.013 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okumura, N. et al. Rho kinase inhibitor enables cell-based therapy for corneal endothelial dysfunction. Sci. Rep.6, 26113. 10.1038/srep26113 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koizumi, N. et al. Cultivated corneal endothelial cell sheet transplantation in a primate model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.48, 4519–4526. 10.1167/iovs.07-0567 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the relevant data are presented in the manuscript. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.