Abstract

Schizophrenia (SZ) and bipolar disorder (BD) pose diagnostic challenges due to overlapping clinical symptoms and genetic factors, often resulting in misdiagnosis and suboptimal treatment outcomes. This study aimed to identify EEG-based biomarkers that can differentiate SZ from BD using multiscale fuzzy entropy (MFE) and relative power (RP) analyses and to evaluate their diagnostic utility using machine learning. EEG data were collected from 65 patients with SZ and 49 patients with BD under resting-state conditions. The MFE and RP were calculated for the bilateral frontal, central, and parietal regions using 30 s EEG segments. For MFE, the band-scale fuzzy entropy (FuzzyEn) was determined across the theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands based on simulation results demonstrating an inverse relationship between scale factors and frequency components. RP was derived by segmenting the EEG data into 2 s intervals with a 500 ms moving window. A support vector machine (SVM) was used to differentiate between patients with SZ and BD based on band-scale FuzzyEn and RP. The SVM classifier achieved an accuracy of 78.94%, a sensitivity of 81.53%, and a specificity of 75.51%. Patients with SZ showed higher theta-scale FuzzyEn in the right frontal, left central, and bilateral parietal regions; higher alpha-scale FuzzyEn in the right parietal region; and increased theta power in the bilateral frontal, central, and right parietal regions. These differences remained robust after controlling for medication effects. These findings demonstrate the potential of combining MFE, RP, and machine learning to differentiate between SZ and BD, contributing to improved diagnostic precision in psychiatric disorders.

Subject terms: Bipolar disorder, Schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ) and bipolar disorder (BD) are severe mental illnesses that exhibit overlapping clinical symptoms, brain characteristics, and genetic risk factors, which often lead to misdiagnoses. These diagnostic inaccuracies can worsen patient outcomes and increase healthcare costs for individuals and society [1–3]. As a result, neuroimaging researchers have been striving to identify biomarkers that can more accurately differentiate these disorders [4, 5]. Among the various neuroimaging modalities, electroencephalography (EEG) offers distinct advantages in temporal resolution, affordability, and portability [6].

Several studies have demonstrated the potential of resting-state EEG data in distinguishing between patients with SZ and BD. For instance, a study reported that the power spectrum of EEG data could classify patients with SZ and BD with an accuracy of 98.00% [7]. Another study found that functional connectivity (FC) could differentiate between SZ and BD with an accuracy of 63.92% [8]. In addition, a study that used a multi-scale convolutional recurrent neural network to analyze EEG data from a broad psychiatric disorder database reported 68.20% accuracy in classifying four groups: SZ, BD, major depressive disorder, and healthy controls (HCs) [9]. Although these findings underscore the promise of resting-state EEG data for classification, they also reveal significant variability across studies, highlighting the need for further methodological refinements.

Furthermore, several questions must be addressed before these findings can be applied in clinical practice. In particular, the EEG features employed in the aforementioned machine learning studies were based on linear assumptions, whereas brain dynamics are widely considered nonlinear and nonstationary [10]. While linear methods—such as frequency-domain, time-frequency, and connectivity analyses—provide valuable insights into spectral characteristics, temporal changes, and linear interactions among brain regions, they may not fully capture the complex dynamics of the brain [11]. Previous research has demonstrated that nonlinear analysis complements the information obtained from linear measurements and enhances the performance of machine learning approaches when both feature types are combined [12]. Therefore, integrating linear and nonlinear methods can provide a more comprehensive perspective on brain activity, potentially leading to more effective differentiation between SZ and BD.

Moreover, the lack of rigorous machine learning techniques (e.g., proper cross-validation) or their incorrect implementation may have led to optimism bias in the previously reported 98.00% accuracy [7]. This bias can lead to an overestimation of the actual effectiveness of a method [13]. Although FC has shown potential as a biomarker for distinguishing between SZ and BD, its reported prediction accuracy of 63.92% is relatively low [8], suggesting that further research is required to improve its performance and establish its potential as a reliable biomarker.

This study employed two complementary approaches—multiscale fuzzy entropy (MFE) and relative power (RP) analyses—to address these methodological challenges and capture both linear and nonlinear aspects of brain dynamics. These methods were specifically chosen for their ability to characterize different aspects of neural activity while maintaining clinical applicability. Fuzzy entropy (FuzzyEn) quantifies the irregularity and unpredictability of time series data without assuming linearity, using a fuzzy membership function to assess the degree of pattern similarity. This technique has demonstrated enhanced consistency, reduced dependence on data length, and robustness to noise, making it particularly suitable for clinical applications [14, 15]. Indeed, a previous study reported that combining FuzzyEn features with deep learning achieved an accuracy of 99.22% in distinguishing patients with SZ from HCs [16]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated positive correlations between FuzzyEn values at frontal electrodes (Fz and AF3) and the severity of positive symptoms in patients with SZ [17].

MFE extends FuzzyEn by incorporating the concept of multiscale entropy, where multiple coarse-grained time series are constructed using different scale factors. For each scale factor τ, the original time series is divided into non-overlapping windows of length τ, and the data points within each window are averaged [18]. As the scale factor increases, averaging more data points within each window enhances the representation of lower-frequency components. This approach thus enables the characterization of neural oscillation dynamics across a broad frequency spectrum, ranging from high to low frequencies [19].

RP analysis offers a complementary perspective by quantifying the power distribution across EEG frequency bands. This spectral approach has demonstrated high clinical utility, such as distinguishing between BD and HCs with over 90.00% accuracy [4]. In patients with SZ, abnormally elevated theta power has been found to correlate negatively with cognitive performance, suggesting that spectral abnormalities may reflect the severity of cognitive deficits [20].

Finally, integrating MFE and RP analyses enabled the investigation of the nonlinear and linear components of brain activity in patients with SZ and BD. The integration of these complementary approaches enabled the capture of complex nonlinear dynamics through MFE and the traditional spectral characteristics through RP, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying neural mechanisms that differentiate these disorders. The study hypothesized that each disorder group would demonstrate distinct MFE and RP patterns reflecting their unique pathophysiological characteristics, enabling effective discrimination between the two disease groups.

Patients and methods

Participants

Records from the Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital database, which included information on patients diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, were retrospectively analyzed for the present study. The study included 114 participants: 65 patients with SZ and 49 with BD. The BD group comprised 26 patients with BD type I, 15 with BD type II, and 8 with Bipolar Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (BD-NOS). A board-certified psychiatrist established all diagnoses in accordance with the Axis I criteria outlined in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) or according to the diagnostic criteria in the fifth edition (DSM-5) [21, 22]. The severity of SZ symptoms was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [23], whereas the severity of BD symptoms was evaluated using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) [24]. None of the participants had a history of organic brain damage or neurological complications, and none were pregnant. The Institutional Review Board of Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital approved the study (IRB no. 2018-12-012) and waived the requirement for informed consent due to its retrospective nature.

EEG acquisition

Resting-state EEG recordings were obtained while participants closed their eyes for four minutes. EEG data were acquired using a NeuroScan SynAmps amplifier (Compumedics USA, Charlotte, NC, USA) with 62 Ag-AgCl electrodes mounted on a Quik-Cap following the extended 10–20 electrode placement scheme. To monitor eye movements, an electrooculogram (EOG) channel was placed beneath the right eye for vertical movement detection, and another EOG channel was positioned at the outer canthus of the same eye for horizontal movement detection. The EEG data were recorded at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz and were band-pass filtered from 0.1–100 Hz. A 60 Hz notch filter was applied to reduce power-line interference, and electrode impedances were maintained below 5 kΩ throughout data acquisition. A ground electrode was placed on the forehead, and the left and right mastoids served as reference electrodes.

EEG preprocessing

The mean amplitude of each EEG channel was first computed and subtracted from the corresponding signal for baseline correction, thereby removing the direct current offset. Artifact subspace reconstruction was then performed using a threshold of 20 times the standard deviation obtained from artifact-free EEG segments. Specifically, the continuous EEG data were segmented into 500 ms sliding windows and decomposed using principal component analysis. Signal components exceeding the predetermined threshold were identified, and these segments were reconstructed using the artifact-free portions of the EEG [25].

Subsequently, a wavelet-based method was implemented for additional artifact reduction [26]. Each channel underwent a 10-level discrete wavelet transform using the biorthogonal 4.4 wavelet. Level-specific thresholds for artifact detection were then determined via Bayesian estimation [27, 28]. Wavelet coefficients that surpassed these thresholds were classified as artifacts, reconstructed through the inverse wavelet transform, and removed from the original signals [29, 30]. Independent component analysis was then applied to address any remaining artifacts. Finally, a common average reference was applied across all channels to standardize reference conditions.

After preprocessing, the continuous EEG data were segmented into 30 s epochs. Any epoch containing amplitudes that exceeded ±75 μV was automatically excluded from further analysis. One epoch was randomly selected for MFE analysis from the remaining artifact-free epochs per participant. For RP analysis, fifty-seven 2 s segments were generated from the same 30 s EEG segment by shifting a 500 ms window, creating a 1.5 s overlap between consecutive segments (([30–2 s]/0.5 s) + 1 = 57).

Because the coarse-graining procedure in MFE analysis acts as a progressive low-pass filter by averaging consecutive data points at increasing scale factors, no additional filtering was applied during preprocessing. Previous research has shown that this coarse-graining process reduces high-frequency components via window averaging, rendering further filtering measures redundant and potentially detrimental to accurate entropy calculations across multiple scales [19, 31–33]. All preprocessing stages were performed using MATLAB R2021b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Multiscale fuzzy entropy analysis

MFE analysis is used to assess the complexity of EEG time series. The procedure is composed of the following steps:

Step 1: Coarse-graining the time series

This step generates coarse-grained representations from the original time series xn at various scales determined by a scale factor τ. Specifically, the original time series is divided into non-overlapping windows of length τ. The data points in each window are then averaged to form a new, shorter time series, referred to as the coarse-grained time series [18]. This process is described by:

where N denotes the length of the original time series, L indicates the length of the coarse-grained time series, and i denotes the index of the coarse-grained time series. When τ = 1, the sequence is identical to for all i.

Step 2: Forming vectors from the coarse-grained series

For each scale factor τ, vectors of length m are formed from with elements spaced by a time delay d. Each vector is defined as

where d determines the spacing between elements in each vector.

Step 3: Calculating distances between vectors

The maximum distance between corresponding elements of two vectors and is computed as follows:

Step 4: Calculating the average probability of similarity

Once these have been computed for every pair of vectors, the degree of similarity between a given vector and all other vectors (, and ) is determined using an exponential fuzzy membership function.

where r represents the threshold parameter determining the similarity tolerance.

Step 5: Calculating FuzzyEn

For each scale factor τ, FuzzyEn is obtained by comparing the average similarity probability for vectors of length m and m + 1. In a manner analogous to Step 2, vectors of dimension m + 1 are constructed, and their similarity measure is evaluated in the same way. The FuzzyEn value is then computed as [34]:

This study utilized the parameters m = 2, d = 1, and r = 0.15, aligning with common applications in the field [35, 36]. The process involved computing the MFE for each EEG signal first and then averaging the MFE values across signals within each of the six predefined electrode clusters corresponding to distinct brain regions [31]: left frontal (AF3, F1, F3, and F5), right frontal (AF4, F2, F4, and F6), left central (FC1, FC3, FC5, C1, C3, C5, CP1, CP3, and CP5), right central (FC2, FC4, FC6, C2, C4, C6, CP2, CP4, and CP6), left parietal (P1, P3, P5, PO3, and PO5), and right parietal (P2, P4, P6, PO4, and PO6). This yielded the regional average MFE values for each electrode cluster across different scale factors, reflecting regional EEG complexity variations.

Regional band-scale fuzzy entropy

A simulation analysis was conducted to investigate the inverse relationship between the scale factor and the frequency component under the described data conditions. Synthetic signals were generated by adding Gaussian noise to pure sinusoidal rhythms aligned with the boundary frequencies of the defined frequency bands (8, 12, 30, and 50 Hz). For each frequency component, 1000 synthetic signals were created, reflecting all parameters from the EEG signal acquisition process employed in the current study. The mean MFE curve for each frequency component was derived by averaging these 1000 simulated MFE curves, and the scale factor at which each MFE curve reached its first peak was recorded. Subsequently, 70 scale factors were categorized into four groups corresponding to the frequency bands (theta, alpha, beta, and gamma). Within each group, the FuzzyEn values were averaged to obtain a group mean—this represents the band-scale FuzzyEn.

Figure 1A illustrates the MFE analysis results for the simulated signals. The MFE curves for the sinusoidal rhythms in the frequency bands (8, 12, 30, and 50 Hz) peaked at 41, 30, 13, and 7 scale factors, respectively. These findings indicated that lower-scale factors were associated with complexity at higher frequencies, whereas higher-scale factors were associated with complexity at lower frequencies. Based on these observations, the band-scale FuzzyEn values were defined from the MFE curves as follows (Fig. 1B): theta-scale FuzzyEn (averaging FuzzyEn values across scale factors 41–70), alpha-scale FuzzyEn (scale factors 30–40), beta-scale FuzzyEn (scale factors 13–29), and gamma-scale FuzzyEn (scale factors 7–12). Furthermore, these band-scale FuzzyEn values were calculated for six predefined regions to assess regional EEG complexity across different frequency bands. This process yielded the final set of regional band-scale FuzzyEn values.

Fig. 1. Analysis of multiscale fuzzy entropy in simulated signals.

A Fuzzy entropy values are calculated up to 500 scale factors for simulated signals at different frequencies (8 Hz [blue], 12 Hz [purple], 30 Hz [red], and 50 Hz [yellow]). B Fuzzy entropy values are presented across scale factors up to 70, highlighting the corresponding frequency band regions: theta (scale factors 41–70), alpha (scale factors 30–40), beta (scale factors 13–29), and gamma (scale factors 7–12). Triangle markers indicate specific scale factors of interest: 41 (8 Hz), 30 (12 Hz), 13 (30 Hz), and 7 (50 Hz).

Regional relative power

The power spectral density was calculated using a fast Fourier transform to determine the RP of EEG signals within specific frequency bands. The analysis focused on four frequency bands of interest: theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (12–30 Hz), and gamma (30–50 Hz). The RP for each band was obtained by normalizing the absolute power to the total power within the 4–50 Hz range. Based on the electrode configuration specified in the MFE analysis, the RP values from the electrodes in each region were averaged to obtain the regional RP for each frequency band. A square root transformation was performed to address the skewed distribution of regional RP, resulting in a more normal distribution and improved statistical robustness [37].

Statistical analysis

Independent t-tests were conducted to analyze between-group differences in age, education, and duration of illness (DOI), while chi-square tests were performed to examine sex differences between groups. Prior to conducting the analyses, normality was assessed for regional band-scale FuzzyEn and RP variables. All variables satisfied the normality assumption, as their absolute skewness and kurtosis values remained below the thresholds of 2 and 7, respectively [38].

Levene’s test revealed significant heterogeneity of variances between groups following the normality assessment. Consequently, Welch’s independent t-tests were applied to address this violation. Furthermore, analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were performed with mood stabilizer and antipsychotic dosages as covariates, as these dosage levels differed significantly between groups. A false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied to the p-values obtained from Welch’s t-tests and ANCOVA to control for potential type I error inflation arising from multiple comparisons [39].

Pearson partial correlation analyses were conducted to evaluate the relationships between the statistically significant EEG features (regional band-scale FuzzyEn and RP) and clinical severity while controlling for medication dosage and DOI. The statistical significance of these findings was evaluated using 5000 bootstrap samples [40, 41]. All statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB and Jamovi (v2.2.5; The Jamovi Project, Sydney, Australia).

Feature selection and classification

The feature set comprised band-scale FuzzyEn and RP measurements obtained across four frequency bands (theta, alpha, beta, and gamma) in six brain regions (bilateral frontal, central, and parietal). These measurements generated 48 variables (6 regions × 4 bands × 2 measurements), constituting the initial feature set. An additional classification analysis incorporated mood stabilizer and antipsychotic medication dosages as potential features, thus expanding the feature set to 50 variables to assess their effects on classification performance.

Given the limited sample size, a leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) approach was employed [42]. At each iteration, the dataset was partitioned into a single-subject test set and a training set consisting of all remaining observations. Z-score normalization was applied to the training data to reduce inter-feature bias, with the derived parameters (mean and standard deviation) subsequently applied to the test set to prevent data leakage.

Fisher scores, which measure the ratio of between-class variance to within-class variance, were computed exclusively on each training set to identify the most discriminative features [43]. No information from the test set was used, further mitigating data leakage when determining Fisher scores and selecting features. Features were ranked based on these scores, and incremental subsets of features (from 1–20) were evaluated to determine the optimal subset within the training set.

Following this feature selection, classification was performed using a Support Vector Machine (SVM) with a sigmoid kernel. The SVM was configured with default parameters (including the regularization parameter C = 1.0). To address the class imbalance between patients with SZ (n = 65) and those with BD (n = 49), the model incorporated balanced class weights. Specifically, the weight for each class (wi) was computed according to the equation , which ensures that underrepresented classes receive proportionally higher weights [44]. Here n represents the total sample size, k denotes the number of classes, and indicates the number of samples in class i.

During each LOOCV iteration, the SVM model was trained on the features selected solely from the corresponding training set and tested on the corresponding test set, yielding performance metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity). Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, (po–pe)/(1-pe), was subsequently calculated from the confusion matrix, where po denotes the observed agreement, and pe represents the expected agreement by chance, thereby providing a comprehensive assessment that accounts for class imbalance [45].

Performance metrics for each sample and feature subset size were aggregated across all LOOCV folds. The subset achieving the highest average accuracy was deemed optimal. If multiple subsets yielded equivalent accuracy, the subset with the higher balanced accuracy was prioritized. After determining the optimal feature subset size, the feature selection frequency at that subset size was calculated across all LOOCV iterations. The final feature set was derived by selecting the most frequently chosen features, thereby ensuring that the final number of features matched the identified optimal subset size. All analyses were conducted in Python (version 3.9.13), utilizing the scikit-learn (version 1.1.2) library.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic and psychiatric symptom data. There were no significant differences between the patient groups in terms of age, sex, education, or DOI.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

| Variable | SZ (n = 65) | BD (n = 49) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 30/35 | 20/29 | 0.569 |

| Age (years) | 34.03 ± 12.37 | 34.28 ± 9.51 | 0.901 |

| Education (years) | 13.14 ± 2.58 | 13.02 ± 3.50 | 0.835 |

| DOI (months) | 105.51 ± 114.93 | 78.38 ± 78.90 | 0.138 |

| PANSS | |||

| Positive | 20.84 ± 8.88 | ||

| Negative | 21.44 ± 6.64 | ||

| General | 45.35 ± 12.58 | ||

| YMRS | 14.79 ± 9.50 | ||

| Mood Stabilizers | 176.34 ± 460.36 | 564.79 ± 583.23 | |

| Antipsychotics | 1462.25 ± 3784.00 | 297.12 ± 418.34 | |

| Benzodiazepines | 6.28 ± 7.87 | 4.50 ± 7.99 | |

The doses of mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines were converted into their respective valproate, chlorpromazine, and diazepam equivalents, all of which were expressed in milligrams.

SZ schizophrenia, BD bipolar disorder, DOI duration of illness, PANSS Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, YMRS Young Mania Rating Scale.

EEG feature analysis between groups

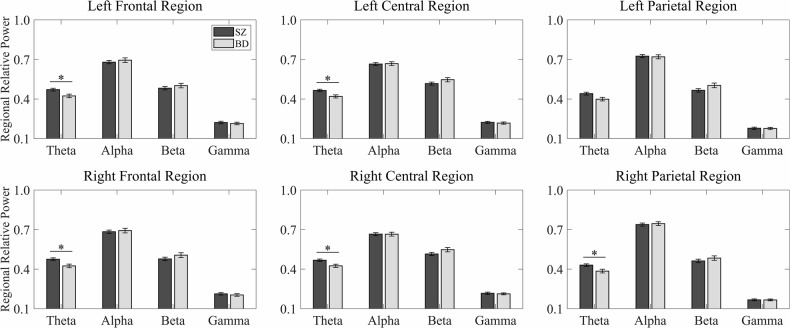

Patients with SZ showed significantly higher theta-scale FuzzyEn values in the right frontal, left central, and bilateral parietal regions than those with BD in the initial Welch’s t-test analyses (Fig. 2). Furthermore, alpha-scale FuzzyEn values were significantly higher in the right parietal region. Regarding regional RP values, patients with SZ exhibited significantly increased theta power in the bilateral frontal and central regions and the right parietal region (Fig. 3). All these differences remained statistically significant after FDR correction (all p < 0.05).

Fig. 2. Band-scale fuzzy entropy in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

This figure presents band-scale fuzzy entropy values from six distinct brain regions (left frontal, right frontal, left central, right central, left parietal, and right parietal) across four frequency bands (theta, alpha, beta, and gamma) for patients with schizophrenia (SZ, black bars) and bipolar disorder (BD, gray bars). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant group differences (p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

Fig. 3. Regional relative power in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

This figure presents regional relative power values from six distinct brain regions (left frontal, right frontal, left central, right central, left parietal, and right parietal) across four frequency bands (theta, alpha, beta, and gamma) for patients with schizophrenia (SZ, black bars) and bipolar disorder (BD, gray bars). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant group differences (p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

Subsequent ANCOVA analyses controlling for mood stabilizer and antipsychotic medication dosages confirmed these findings and revealed additional significant differences. After FDR correction, patients with SZ had higher theta-scale FuzzyEn values in the bilateral frontal, central, and parietal regions. Alpha-scale FuzzyEn values were significantly higher in the bilateral parietal regions, while theta power remained significantly elevated in the bilateral frontal, central, and parietal regions in patients with SZ. The consistency of these results across both analyses further substantiated the robustness of the observed group differences in EEG characteristics.

Correlation analysis of clinical symptoms and EEG features

No significant correlations were found between the statistically significant EEG features (regional band-scale FuzzyEn and RP) and clinical severity scores (PANSS subscales in the SZ group; YMRS in the BD group) in the partial correlation analyses controlling for medication dosage and DOI.

Machine learning-based diagnostic classification

Classification based solely on EEG characteristics yielded an accuracy of 78.94%, with a sensitivity of 81.53%, a specificity of 75.51%, and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.57. The 12 selected features consisted of seven regional band-scale FuzzyEn features (including theta-scale FuzzyEn in the bilateral frontal and parietal regions and the left central region; alpha-scale FuzzyEn in the bilateral parietal regions) and five regional RP features (comprising theta power in the bilateral frontal and central regions and the right parietal region). The detailed characteristics of these selected features are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, effect sizes, selection frequencies, and p-values for the selected features used to distinguish patients with schizophrenia from those with bipolar disorder.

| Selected features | SZ (n = 65) | BD (n = 49) | Effect size (Cohen’s d) | Frequency | P (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band-scale FuzzyEn | |||||

| Left frontal theta-scale FuzzyEn | 1.57 ± 0.08 | 1.53 ± 0.09 | −0.478 | 112 | 0.056 |

| Right frontal theta-scale FuzzyEn | 1.57 ± 0.07 | 1.53 ± 0.10 | −0.509 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Left central theta-scale FuzzyEn | 1.55 ± 0.07 | 1.51 ± 0.09 | −0.502 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Left parietal theta-scale FuzzyEn | 1.53 ± 0.09 | 1.47 ± 0.11 | −0.532 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Right parietal theta-scale FuzzyEn | 1.53 ± 0.09 | 1.46 ± 0.11 | −0.626 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Left parietal alpha-scale FuzzyEn | 1.72 ± 0.06 | 1.68 ± 0.07 | −0.483 | 109 | 0.055 |

| Right parietal alpha-scale FuzzyEn | 1.73 ± 0.06 | 1.69 ± 0.08 | −0.507 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Regional RP | |||||

| Left frontal theta power | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | −0.527 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Right frontal theta power | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | −0.553 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Left central theta power | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 0.41 ± 0.08 | −0.573 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Right central theta power | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 0.42 ± 0.08 | −0.529 | 114 | 0.049 |

| Right parietal theta power | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | −0.503 | 114 | 0.049 |

SZ schizophrenia, BD bipolar disorder, FuzzyEn fuzzy entropy, RP relative power.

An additional SVM analysis incorporating medication dosages as potential features demonstrated comparable performance, with an accuracy of 78.07%, a sensitivity of 78.46%, a specificity of 77.55%, and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.55. Among the 12 selected features in this expanded analysis, 11 remained consistent with those listed in Table 2. Specifically, the mood stabilizer dosage replaced the feature ‘left frontal theta-scale FuzzyEn’ as a discriminative measure. This consistency in both feature selection and classification accuracy reinforced the stability of EEG characteristics as diagnostic markers.

Discussion

This study investigated the complexity and power distribution in the brains of patients with SZ and BD using regional band-scale FuzzyEn and RP analyses. The calculation of regional band-scale FuzzyEn was based on the MFE, considering the inverse relationship between scale factors and frequency components demonstrated in the simulations. Initial analyses revealed that patients with SZ exhibited significantly higher theta-scale FuzzyEn values in the right frontal, left central, and bilateral parietal regions and a higher alpha-scale FuzzyEn value in the right parietal region than those with BD. Moreover, patients with SZ showed significant increases in theta RP values in the bilateral frontal and central regions and the right parietal region. The SVM classifier using 12 features achieved a classification accuracy of 78.94%, a sensitivity of 81.53%, and a specificity of 75.51%, along with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.57. Subsequent analyses that controlled for medication effects revealed additional significant differences in theta-scale FuzzyEn in the left frontal and right central regions, alpha-scale FuzzyEn in the left parietal region, and theta RP in the left parietal region. Furthermore, an SVM analysis incorporating medication information achieved comparable performance (accuracy: 78.07%, sensitivity: 78.46%, specificity: 77.55%), and 11 of the 12 selected features remained consistent with the initial analysis. No significant correlations were found between clinical severity scores and EEG characteristics.

The results indicated that patients with SZ exhibited significantly higher theta-scale FuzzyEn and theta RP values in almost all brain regions than those with BD. These differences persisted even after controlling for medication effects, thus underscoring the critical role of theta band alterations in differentiating SZ from BD. These findings align with previous neuroimaging studies. Specifically, a comparative analysis of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data between patients with SZ and BD demonstrated that patients with SZ exhibited significantly higher entropy values in the precuneus with increasing scale factors [46]. This finding parallels the EEG results presented in the study, as scale factors in fMRI analysis represent a temporal averaging process, where higher-scale factors average the blood-oxygen-level-dependent signal over longer time windows, capturing slow temporal trends and long-term dynamic patterns. Furthermore, a previous resting-state EEG study observed that patients with SZ displayed higher multiscale sample entropy (MSE) values at higher-scale factors (i.e., lower frequency) in the frontal, central, and parieto-occipital regions than those with BD [31]. Another resting-state EEG study reported that patients with SZ exhibited significantly increased theta phase instability at the frontocentral electrode compared with those with BD [47]. In addition, spectral power analyses indicated that patients with SZ had higher theta activity in the frontal, temporal, and central regions than those with BD [48].

The present study revealed that regional band-scale FuzzyEn and regional RP values, predominantly in the theta frequency band, were the most effective features for distinguishing between the SZ and BD groups. Among the 12 most discriminative features identified, 10 were related to theta activity, while only two were associated with the alpha band. Previous research suggests that abnormalities in low-frequency resting-state EEGs across various psychiatric disorders reflect disorder-specific pathophysiology [31, 49, 50]. Therefore, the elevated theta activity observed in patients with SZ may represent unique pathophysiological features that differ from those with BD.

Building on these findings, the abnormally increased entropy and power in the low-frequency bands identified in patients with SZ may reflect underlying pathological characteristics, particularly cognitive impairments. Several studies have established links between these EEG characteristics and clinical manifestations. A previous study reported positive correlations between MSE values at higher-scale factors and PANSS positive scores in the frontal and parieto-occipital regions in patients with SZ [31]. A resting-state fMRI study demonstrated that increased brain signal randomness in the prefrontal cortex correlates with reduced cognitive function in patients with schizoaffective disorder [51]. Moreover, previous neuroimaging studies have reported an association between theta power and impaired cognitive processes. Analyses of EEG data revealed that increased theta amplitude at the frontal midline electrode was associated with poor verbal memory performance in patients with SZ [52]. Further EEG investigations identified negative correlations between theta power in the central and parietal regions and processing speed scores in patients with SZ [53]. Another study showed that patients with SZ exhibited a significant association between their LFA factor (increased low-frequency power and diminished alpha-band activity) at central electrode sites and the severity of negative symptoms [54].

These distinct EEG patterns are likely linked to dopaminergic dysregulation, as dopamine modulates neural activity and network synchronization. Evidence supporting this relationship has emerged from multiple lines of research. A study of drug-naïve patients with SZ reported significantly elevated MSE values at higher-scale factors, particularly in the fronto-centro-temporal areas, compared to HCs. These elevated MSE patterns were normalized after the administration of antipsychotic medications, which primarily act through dopamine receptor antagonism [19]. Neuroimaging studies have further supported the link between dopaminergic activity and neural oscillations. A positron emission tomography study showed significant correlations between increased endogenous dopamine release and enhanced theta activity [55]. A controlled experimental study also established that selective dopamine elevation in the hippocampus through photouncaging techniques directly increased theta oscillatory activity [56].

In contrast to SZ, where dopamine hyperactivity is consistently reported [57, 58], BD is characterized by fluctuations in dopamine activity—increasing during manic episodes and decreasing during depressive episodes [59]. These characteristic dopaminergic variations provide a potential explanation for the relatively reduced low-frequency EEG activity observed in BD. Specifically, while dopamine hyperactivity during manic phases may temporarily enhance low-frequency activity, the subsequent periods of depressive hypo-dopaminergic states likely suppress this activity. The observed differences in low-frequency EEG activity between patients with BD and those with SZ may reflect these distinct patterns of dopaminergic activity.

The present study provides insights into the neurophysiological differences between patients with SZ and BD while acknowledging certain limitations. Although medication effects were statistically controlled for in the analyses and the results remained consistent, future studies incorporating drug-naïve patients would provide additional validation. The sample size was sufficient for statistical analysis, but subsequent research could benefit from larger cohorts to enhance the generalizability of these results. Furthermore, while no significant correlations were found between clinical severity and EEG characteristics, longitudinal studies might better elucidate the relationship between symptom progression and these neurophysiological markers. This study represents the first comprehensive investigation employing linear and nonlinear analyses to compare these disorders directly. The observed differences in entropy and power analyses, particularly in the theta band, support the potential clinical application of EEG-based biomarkers for differential diagnosis between SZ and BD.

Conclusion

This study investigated the complexity and power distribution in patients with SZ and BD using regional band-scale FuzzyEn and RP analyses. The findings showed that patients with SZ consistently demonstrated significantly higher theta-scale FuzzyEn and RP values across multiple brain regions than those with BD. Furthermore, these differences remained robust even after controlling for medication effects. In addition, the SVM classifier achieved a classification accuracy of 78.94% using only EEG features. Notably, its performance remained comparable when medication information was included. These results—particularly the significant and consistent differences in theta-band activity—underscore the potential of entropy and power analyses of low-frequency EEG as reliable biomarkers for differentiating SZ from BD.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF), funded by the Korean government (MSIT), under Grant No. RS-2024-00455484. Additionally, this research was supported by the K-Brain Project of the National Research Foundation (NRF), funded by the Korean government (MSIT), under Grant No. RS-2023-00262568.

Author contributions

Conception/design of the work: H-HH, SK, and S-HL; data acquisition and analysis: H-HH, K-MC, and S-HL; interpretation of data: H-HH, K-MC, SK, and S-HL; writing (original draft preparation and editing): H-HH, SK, and S-HL. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The EEG datasets analyzed in this study were collected from 65 patients with schizophrenia and 49 patients with bipolar disorder under resting-state conditions. Data supporting Figs. 2 and 3, as well as Tables 1 and 2, include raw EEG recordings, preprocessed EEG segments, multiscale fuzzy entropy values, and relative power measurements. Relevant clinical data include PANSS scores for individuals with schizophrenia and YMRS scores for individuals with bipolar disorder. Public access to these datasets is restricted to protect patient confidentiality and to comply with the research protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital (IRB no. 2018-12-012). All datasets are securely stored in the Clinical Emotion and Cognition Research Laboratory database at Inje University. Researchers seeking de-identified versions of these datasets for scientific inquiries may submit a formal request to the corresponding authors: Sungkean Kim, PhD (kimsk@hanyang.ac.kr) or Seung-Hwan Lee, MD, PhD (lshpss@paik.ac.kr). Any request for data sharing is subject to institutional ethics committee approval and requires a formal data use agreement to safeguard patient information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were conducted in compliance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Approval for this retrospective study was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital (IRB no. 2018-12-012). The IRB formally waived the requirement for informed consent in accordance with established protocols for retrospective studies analyzing existing medical records without additional patient contact.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sungkean Kim, Email: kimsk@hanyang.ac.kr.

Seung-Hwan Lee, Email: lshpss@paik.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Bambole V, Johnston M, Shah N, Sonavane S, Desouza A, Shrivastava A. Symptom overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar mood disorder: diagnostic issues. Open J Psychiatry. 2013;2013. 10.4236/ojpsych.2013.34A002.

- 2.Cardno AG, Owen MJ. Genetic relationships between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:504–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh T, Rajput M. Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry. 2006;3:57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravan M, Noroozi A, Sanchez MM, Borden L, Alam N, Flor-Henry P, et al. Diagnostic deep learning algorithms that use resting EEG to distinguish major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia from each other and from healthy volunteers. J Affect Disord. 2024;346:285–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alimardani F, Cho J-H, Boostani R, Hwang H-J. Classification of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia using steady-state visual evoked potential based features. IEEE Access. 2018;6:40379–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loo SK, Lenartowicz A, Makeig S. Research review: use of EEG biomarkers in child psychiatry research–current state and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57:4–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Gohary M, Al Zohairy T, Eissa A, El Deghaidy S, Hussein H. An intelligent system for diagnosis of schizophrenia and bipolar diseases using support vector machine with different kernels. Int J Appl Eng Sci. 2016;3:257568. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gan M, Lei L, Zeng L-L, Su J, Sun N, Yang C, et al. P182. diagnostic classification of schizophrenia and bipolar disorders using machine learning on resting-state EEG. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;91:S160–S1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan W, Yu L, Liu D, Sui J, Calhoun VD, Lin Z. Multi-scale convolutional recurrent neural network for psychiatric disorder identification in resting-state EEG. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1202049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stam CJ. Nonlinear dynamical analysis of EEG and MEG: review of an emerging field. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:2266–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahamed SI, Rabbani M, Povinelli RJ, editors. A comprehensive survey on detection of non-linear analysis techniques for EEG signal. IEEE international conference on digital health (ICDH); IEEE;2023.

- 12.Mahato S, Paul S. Detection of major depressive disorder using linear and non-linear features from EEG signals. Microsyst Technol. 2019;25:1065–76. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allgaier J, Pryss R. Practical approaches in evaluating validation and biases of machine learning applied to mobile health studies. Commun Med. 2024;4:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azami H, Li P, Arnold SE, Escudero J, Humeau-Heurtier A. Fuzzy entropy metrics for the analysis of biomedical signals: assessment and comparison. IEEE Access. 2019;7:104833–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Ezzi A, Al-Shargabi AA, Al-Shargie F, Zahary AT. Complexity analysis of EEG in patients with social anxiety disorder using fuzzy entropy and machine learning techniques. IEEE Access. 2022;10:39926–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun J, Cao R, Zhou M, Hussain W, Wang B, Xue J, et al. A hybrid deep neural network for classification of schizophrenia using EEG Data. Sci Rep. 2021;11:4706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiang J, Tian C, Niu Y, Yan T, Li D, Cao R, et al. Abnormal entropy modulation of the EEG signal in patients with schizophrenia during the auditory paired-stimulus paradigm. Front Neuroinform. 2019;13:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa M, Goldberger AL, Peng C-K. Multiscale entropy analysis of biological signals. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2005;71:021906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi T, Cho RY, Mizuno T, Kikuchi M, Murata T, Takahashi K, et al. Antipsychotics reverse abnormal EEG complexity in drug-naive schizophrenia: a multiscale entropy analysis. Neuroimage. 2010;51:173–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wichniak, Okruszek A, Linke M, Jarkiewicz M, Jędrasik-Styła M, Ciołkiewicz A, et al. Electroencephalographic theta activity and cognition in schizophrenia: preliminary results. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16:206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

- 22.American Psychiatric Association D, American Psychiatric Association D. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American psychiatric association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang C-Y, Hsu S-H, Pion-Tonachini L, Jung T-P. Evaluation of artifact subspace reconstruction for automatic artifact components removal in multi-channel EEG recordings. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2019;67:1114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez KL, Monachino AD, Morales S, Leach SC, Bowers ME, Gabard-Durnam LJ. HAPPILEE: HAPPE in low electrode electroencephalography, a standardized pre-processing software for lower density recordings. Neuroimage. 2022;260:119390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clyde M, George EI. Flexible empirical Bayes estimation for wavelets. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 2000;62:681–98. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnstone IM, Silverman BW. Empirical Bayes selection of wavelet thresholds. Ann Stat. 2005;33:1700–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donoho DL. De-noising by soft-thresholding. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 1995;41:613–27. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo D-F, Zhu W-H, Gao Z-M, Zhang J-Q. A study of wavelet thresholding denoising. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Signal Processing (ICSP 2000): WCC 2000–ICSP 2000, 16th World Computer Congress 2000; Beijing, China. Vol. 1. IEEE; 2000. pp. 329–332.

- 31.Hwang H-H, Choi K-M, Im C-H, Yang C, Kim S, Lee S-H. Comparative analysis of resting-state EEG-based multiscale entropy between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2024;134:111048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catarino A, Churches O, Baron-Cohen S, Andrade A, Ring H. Atypical EEG complexity in autism spectrum conditions: a multiscale entropy analysis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:2375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okazaki R, Takahashi T, Ueno K, Takahashi K, Ishitobi M, Kikuchi M, et al. Changes in EEG complexity with electroconvulsive therapy in a patient with autism spectrum disorders: a multiscale entropy approach. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li P, Karmakar C, Yearwood J, Venkatesh S, Palaniswami M, Liu C. Detection of epileptic seizure based on entropy analysis of short-term EEG. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azami H, Smith K, Escudero J. MEMD-enhanced multivariate fuzzy entropy for the evaluation of complexity in biomedical signals. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2016;2016:3761–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharyya A, Pachori RB, Acharya UR. Tunable-Q wavelet transform based multivariate sub-band fuzzy entropy with application to focal EEG signal analysis. Entropy. 2017;19:99. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee D. Analysis of phase-locked oscillations in multi-channel single-unit spike activity with wavelet cross-spectrum. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:16. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim S, Kim Y-W, Jeon H, Im C-H, Lee S-H. Altered cortical thickness-based individualized structural covariance networks in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henderson AR. The bootstrap: a technique for data-driven statistics. Using computer-intensive analyses to explore experimental data. Clinica Chim Acta. 2005;359:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng H, Garrick DJ, Fernando RL. Efficient strategies for leave-one-out cross validation for genomic best linear unbiased prediction. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2017;8:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamla H, Ghanem K. A hybrid feature selection based on Fisher score and SVM-RFE for microarray data. Informatica. 2024;48:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 44.King G, Zeng L. Logistic regression in rare events data. Political Anal. 2001;9:137–63. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22:276–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang N, Niu Y, Sun J, An W, Li D, Wei J, et al. Altered complexity of spontaneous brain activity in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;54:586–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lechner S, Northoff G. Temporal imprecision and phase instability in schizophrenia resting state EEG. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;86:103654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Narayanan B, O’Neil K, Berwise C, Stevens MC, Calhoun VD, Clementz BA, et al. Resting state electroencephalogram oscillatory abnormalities in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar patients and their relatives from the bipolar and schizophrenia network on intermediate phenotypes study. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:456–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jang K-I, Kim E, Lee HS, Lee H-A, Han JH, Kim S, et al. Electroencephalography-based endogenous phenotype of diagnostic transition from major depressive disorder to bipolar disorder. Sci Rep. 2024;14:21045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shim M, Im C-H, Lee S-H, Hwang H-J. Enhanced performance by interpretable low-frequency electroencephalogram oscillations in the machine learning-based diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Neuroinform. 2022;16:811756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hager B, Yang AC, Brady R, Meda S, Clementz B, Pearlson GD, et al. Neural complexity as a potential translational biomarker for psychosis. J Affect Disord. 2017;216:89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirihara K, Rissling AJ, Swerdlow NR, Braff DL, Light GA. Hierarchical organization of gamma and theta oscillatory dynamics in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:873–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao Y, Han C, Peng X, Su Z, Liu G, Xie Y, et al. Correlation between resting theta power and cognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16:853994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sponheim SR, Clementz BA, Iacono WG, Beiser M. Clinical and biological concomitants of resting state EEG power abnormalities in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:1088–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kjaer TW, Bertelsen C, Piccini P, Brooks D, Alving J, Lou HC. Increased dopamine tone during meditation-induced change of consciousness. Cogn Brain Res. 2002;13:255–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Velazquez-Delgado C, Perez-Becerra J, Calderon V, Hernandez-Ortiz E, Bermudez-Rattoni F, Carrillo-Reid L. Paradoxical boosting of weak and strong spatial memories by hippocampal dopamine uncaging. Eneuro. 2024;11. 10.1523/ENEURO.0469-23.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Brisch R, Saniotis A, Wolf R, Bielau H, Bernstein H-G, Steiner J, et al. The role of dopamine in schizophrenia from a neurobiological and evolutionary perspective: old fashioned, but still in vogue. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kraguljac NV, McDonald WM, Widge AS, Rodriguez CI, Tohen M, Nemeroff CB. Neuroimaging biomarkers in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:509–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berk M, Dodd S, Kauer‐Sant’anna M, Malhi G, Bourin M, Kapczinski F, et al. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: implications for a dopamine hypothesis of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The EEG datasets analyzed in this study were collected from 65 patients with schizophrenia and 49 patients with bipolar disorder under resting-state conditions. Data supporting Figs. 2 and 3, as well as Tables 1 and 2, include raw EEG recordings, preprocessed EEG segments, multiscale fuzzy entropy values, and relative power measurements. Relevant clinical data include PANSS scores for individuals with schizophrenia and YMRS scores for individuals with bipolar disorder. Public access to these datasets is restricted to protect patient confidentiality and to comply with the research protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital (IRB no. 2018-12-012). All datasets are securely stored in the Clinical Emotion and Cognition Research Laboratory database at Inje University. Researchers seeking de-identified versions of these datasets for scientific inquiries may submit a formal request to the corresponding authors: Sungkean Kim, PhD (kimsk@hanyang.ac.kr) or Seung-Hwan Lee, MD, PhD (lshpss@paik.ac.kr). Any request for data sharing is subject to institutional ethics committee approval and requires a formal data use agreement to safeguard patient information.