Abstract

The use of nanomaterials as drug delivery systems is an area of interest for various anticancer drugs, aiming to minimize their side effects while ensuring they reach the target site effectively. In the current study, Benzotriazole capsule as drug delivery system for cyclophosphamide (CP) and gemcitabine (GB) drugs adsorption is explored. Various electronic and structural parameters shows that both drugs have good interaction with nanocapsule and can be carried to the target site easily. The calculated binding energies of drug@Capsule complexes are in the range of −43.34 and − 56.64 kcal/mol, which shows stronger interaction of drug molecules with nanocapsule. The noncovalent interactions between CP, GB and capsule are confirmed through QTAIM and NCI analyses. NBO analysis is used to understand the shifting of electron density, which shifts from drug to surface. FMO analysis is performed to estimate the perturbations in the electronic parameters upon complexation, which reveals reduction in the EH−L gap. Moreover, pH effect and dipole moment analysis are performed to get insight into the drug release mechanism. Dipole moment values indicate that nanocapsule can effectively release CP drug on a target site. The findings suggest that benzotriazole capsule surface is highly selective toward CP and GB.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-91719-0.

Keywords: Drug delivery, Anticancer agents, Gemcitabine, Density-functional theory, Benzotriazole capsule, Sensing

Subject terms: Cancer, Chemistry, Supramolecular chemistry

Introduction

Among the global contributor to mortality, cancer remains a very significant cause of death. There are a number of anticancer drugs, but yet the number of patients are increasing continuously1. Although different strategies and medication have been used to treat cancerous cells, however, there are some shortcomings such as toxicity to normal cells along with low efficacy and complex treatments. The major factor behind the low treatment efficacy is poor targeting of the therapeutics which cause severe side effects on other healthy tissues2. Therefore, site-specific therapeutic agents for the affected regions are highly required. To overcome this problem, nanotechnology formulations are the effective approaches for overcoming the hurdles of undirected side effects, undesired biodistribution, and high-dose administration3.

Non-targeted drug delivery in the field of medicine, particularly in cancer treatment, involves the challenge of delivering therapeutic agents effectively to the intended site of action while minimizing systemic side effects. Traditional drug delivery methods often result in the distribution of drugs throughout the body, leading to reduced efficacy and increased toxicity4,5. With the more use of nanomedicine, different nano formulations with excellent pharmacokinetic properties, and biocompatibility have great potential for novel anti-cancer drugs delivery6–9. Nanoparticles enhance the therapeutic circulation period in blood for more tumor accumulation and facilitate their use for the tumor therapies. By encapsulating special therapeutic agents, the nanomedicines can be generated in nanocarriers to achieve satisfactory tumor targeting by using the effect-mediated passive targeting strategy10–16.

Over the past few decades, rapid progress has been observed in nanotechnology which brought various captivating ideas and possibilities for disease diagnosis and treatment17. Hence, nanocarriers have achieved considerable attention due to their targeted attack on cancerous cells. The nanocarriers for drug delivery in cancer therapy have shown promising results while avoiding damage to healthy cells18. Furthermore, nanoparticles based drug delivery vehicles provide solutions to lesser absorption issue, which reveal noteworthy aptitude of nanoparticle based DDS in cancer treatment19. Examples of such nanocarriers that have been used for encapsulation and effective drug delivery including, micelles, nanoparticles, polymeric conjugates, dendrimers, liposomes, carbon nanotubes, capsules and hydrogel20–22. These nanocarriers have been employed as anticancer drug vehicles and have revealed effective performance in minimizing side effects23.

Similarly, nano self-assembled structures formed from amphiphilic copolymers can act as excellent anticancer drug vehicles like doxorubicin24. Furthermore, various drug delivery carriers responsive to near-IR light have been synthesized and reported successfully. These drug delivery carriers show exceptional results for the treatment of cancer cells. P. N. Samanta et al. reported fullerene (C60) nanocage as a drug delivery vehicle for transport of carmustine and temozolomide drugs25. They observed that off-loading of carmustine and temozolomide drugs into biological systems is facilitated by the increase in polarity of C60 nanocage upon adsorption of these drugs. Moreover, graphene and graphene oxide (GO) have also been reported as the nanostructure drug delivery vehicles. Both can act as promising candidates for delivery of various drugs due to their effective loading, targeted drug delivery, and controlled release26. However, there is a room available to study new targeting material that should possess significant therapeutic efficacy large surface area, rapid response, higher selectivity and sensitivity along with reduced side effect27,28. Owing to the importance of targeted drug delivery in medicinal chemistry, the design and development of highly effective and innovative drug delivery system with better therapeutic profiles is undeniable.

In the current study, we investigate the drug delivery properties of benzotriazole capsule for cyclophosphamide and Gemcitabine drugs. Cyclophosphamide (CP) was first studied on rat tumors, due to anticancer, alkylating agent properties. It has oxazaphosphorine-substituted nitrogen mustard, having strong immunosuppressive and cytotoxic activity29. Whereas Gemcitabine is one of the cytotoxic drugs, a pyrimidine nucleoside antimetabolite. Gemcitabine has been authorized for treating non-small cell lung cancer, bladder, pancreatic, and breast cancer30–32. Moreover, extensive literature is available on benzotriazole capsule based cavitands in conjunction with recent advancement in supramolecular chemistry33–36. Benzotriazole nanocapsules can be engineered to enhance the specificity of drug delivery. By modifying their surface properties, these nanocapsules can be designed to recognize and bind to specific cancer cells, allowing for targeted delivery of anticancer drugs directly to the tumor site. This reduces the exposure of healthy tissues to the drug, thereby minimizing side effects.

In medicinal chemistry, weak noncovalent interactions play a vital role in the development of active and more selective ligands37. Deep benzotriazole cavitand-based dimeric nanocapsules can act as excellent hosts for small drug molecules38,39. The presence of cavity facilitates the adsorption of drugs on surface, therefore make surface as potential candidates for adsorption applications40. In this study, DFT simulation are carried out to study the adsorption of two anticancer drugs on nanocapsule. The change in electronic parameters upon complexation is studied via frontier molecular orbital analysis. Moreover, non-covalent interaction and quantum theory of atom in molecule analyses are performed to examine the nature of the interaction between drugs and nanocapsule.

Computational details

Gaussian 09 package is adopted to performed the quantum chemical simulation41. Geometry optimization is performed at M06-2X/6-31G(d, p) level of theory. M06-2X is a hybrid functional with double the amount of non-local exchange is considered best for studying the noncovalent interactions42. Chemcraft and GaussView 5.0 packages are utilized to visualize the optimized geometries43. The binding energies were calculated according to the following equation: Binding energy (Eb) values are computed by using Eq. (1)44–46.

|

1 |

Where k is the total number of atoms present in MWCNT complex, Ecomplex is the energy of functionalized MWCNT complex, whereas EC, EH, EN, EO and EX represent the energies of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and halogen atoms, respectively. Additionally, the comparative result with and without the employment of Grimme’s dispersion correction are presented in Table 1 to investigate the interactions between the drugs molecules and the capsule.

Table 1.

Binding energies (kcal/mol), BSSE, dispersion corrected (Edis) Kcal/mol and bond lengths (Å) of the Drugs@capsule complexes at the M06-2X/ 6-31G(d, p) level of theory.

| Drugs@Capsule | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | Intermolecular bond | Bond length (Å) | Eb (without dispersion correction) | Edis (with dispersion correction) |

| CP@Cap | H1–O5 | 2.97 | −43.34 | −53.35 |

| O2–H6 | 2.64 | |||

| H3–H7 | 2.82 | |||

| O4–H8 | 2.54 | |||

| GB@Cap | H1–O5 | 2.73 | −56.64 | −64.66 |

| N2–H6 | 2.80 | |||

| H3–F7 | 2.69 | |||

| O4–H8 | 2.65 | |||

The mode of charge transfer between drugs and capsule is performed through natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis. Moreover, visual depiction of charge transfer is evaluated via (EDD) analysis47,48. NCI and QTAIM analyses are employed to understand the nature of interactions between the interacting fragments i.e., drugs and nanocapsule. Multiwfn 3.7 software is implemented to study QTAIM and NCI analysis49. Moreover, visual molecular dynamics (VMD) package is for plotting three dimensional graphs40.

Results and discussion

Geometric optimization and adsorption energies

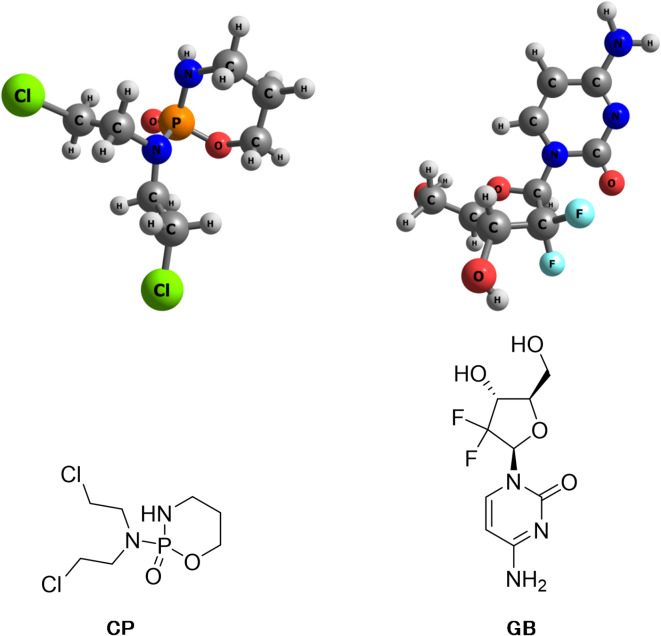

In this study, two different drugs; cyclophosphamide (CP) and gemcitabine (GB) have been selected to investigate the adsorption on benzotriazole capsule as a drug delivery system for CP and GB. Chemical structures of these drugs are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Optimized geometries and simple images of studied anticancer drugs.

The optimized Benzotriazole capsule surface is shown in Fig. 2. The structure consists of hydrogen bonds arranged in a cyclic array, bridged by water molecules, which stabilizes the complexes vase conformation. Computations show that the additional waters on the upper rim create a self-complementary hydrogen-bonding pattern for capsule formation. (see Fig. 2)39.

Fig. 2.

Stable structure of capsule at the M06-2X/6-31G(d, p) level of theory (blue, red, white and grey represent nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, and carbon, respectively).

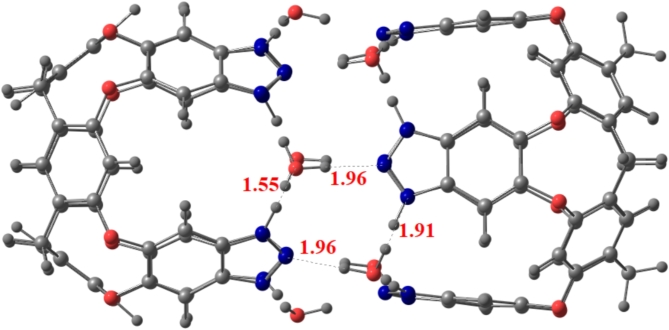

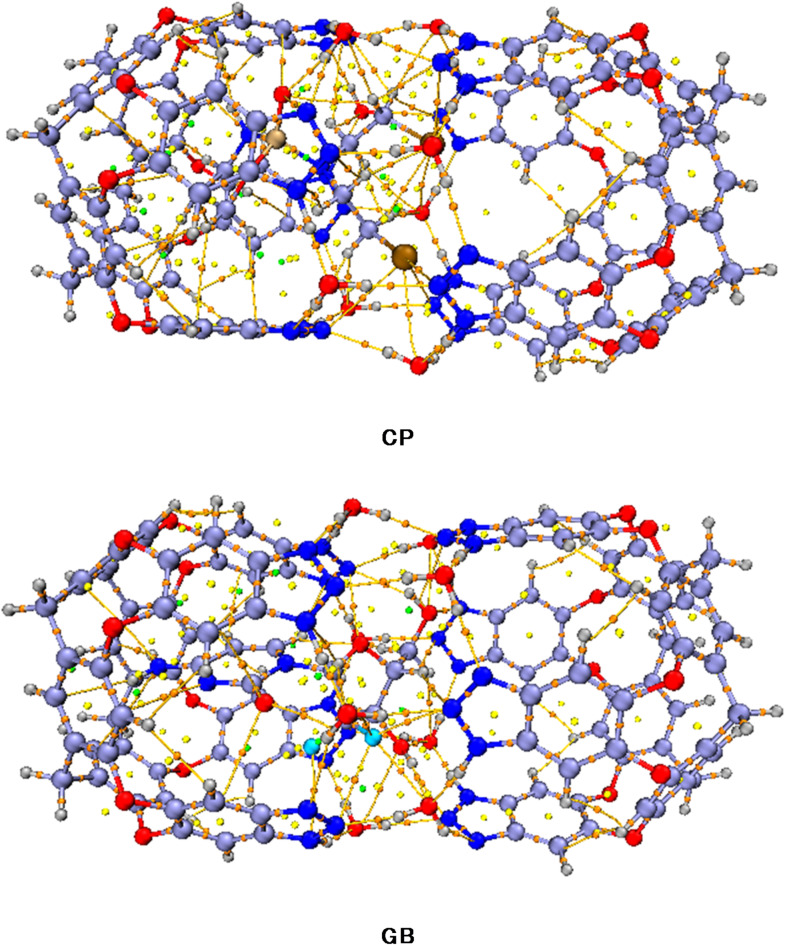

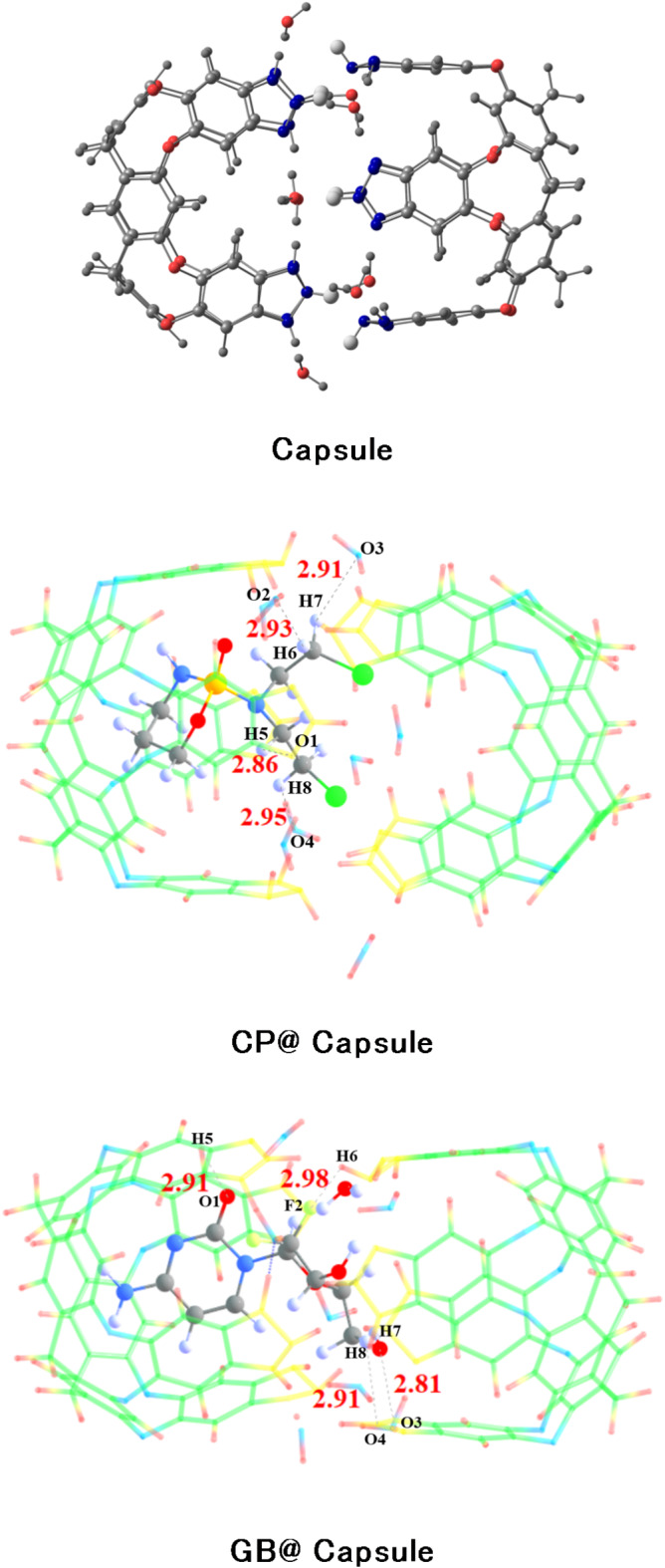

All possible orientations are investigated over four binding sites that are favorable to get the lowest energy and the most stable configuration for drug@capsule complexes. The most stable optimized geometries of drug@capsule complexes are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The most stable geometries of drugs@Capsule complexes at the M06-2X/6-31G(d, p) level of theory.

Interaction distances decrease when analytes approach towards surface (capsule) for complexation. Interactions existing between drugs and capsule surface can also be examined through interaction energy analysis. The calculated binding energy and interaction distances for studied drugs@capsule complexes are given in Table 1.

The binding energies of CP@Cap, and GB@Cap complexes are almost comparable with one another, and the computed binding energy (Eb) values are − 43.34 kcal/mol and − 56.64 kcal/mol, respectively. The same order of binding energy and BSSE corrected energy is observed in both the studied complexes. The stable structures of CP@Capsule display the presence of non-covalent interactions among O-atoms of nanocapsule and H-atoms of drug. The shortest interaction distance is seen among O…H bonds i.e., O4…H8 and O2…H6 bonds in the case of CP@Capsule complex show interaction distances of 2.54 Å and 2.64 Å, respectively (see Fig. 3). Moreover, a relatively weaker interaction is observed for O5…H1 (2.82 Å) bond of CP@Capsule complex, which shows that the presence of weak van der Waals forces.

The inclusion of Grimme’s dispersion significantly affects the binding energy of studied complexes. The binding energy with dispersion correction is somehow higher. However, the trend of binding energy is same with and without Grimme’s dispersion. The calculated dispersion corrected binding energy shows strong interaction for GB@Cap (-64.66 kcal/mol) as compared to CP@Cap (-53.35 kcal/mol). The binding energy of CP is lower as compared to GB. The higher binding energy values display the higher stability of drugs@Capsule. Overall, gemcitabine drug shows slightly higher stability as compared to cyclophosphamide. This might be due to the reason that gemcitabine fits better in the cavity of capsule than cyclophosphamide.

The stable geometry of GB@Cap complex shows that the N-atoms of GB are interacting with H-atoms of the surface. GB drug and capsule interacted with each other through N2…H6 (2.80 Å) and H3…F7 (2.69 Å) bonds.

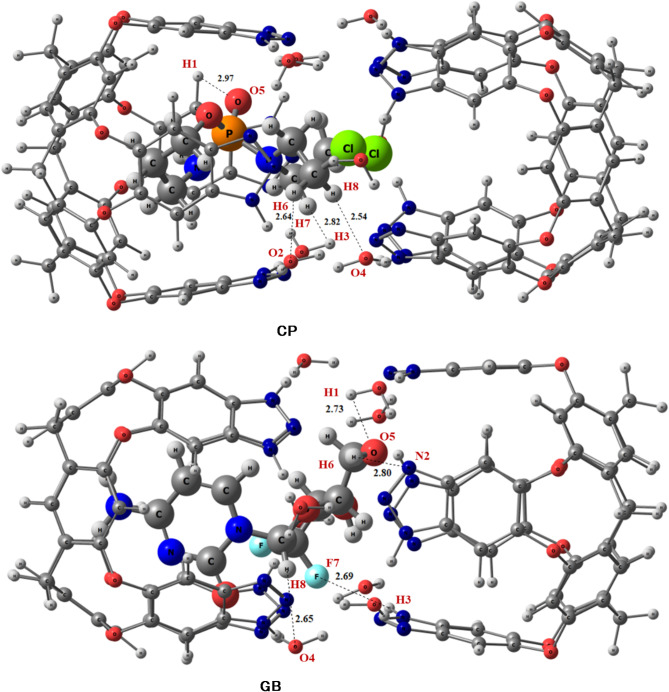

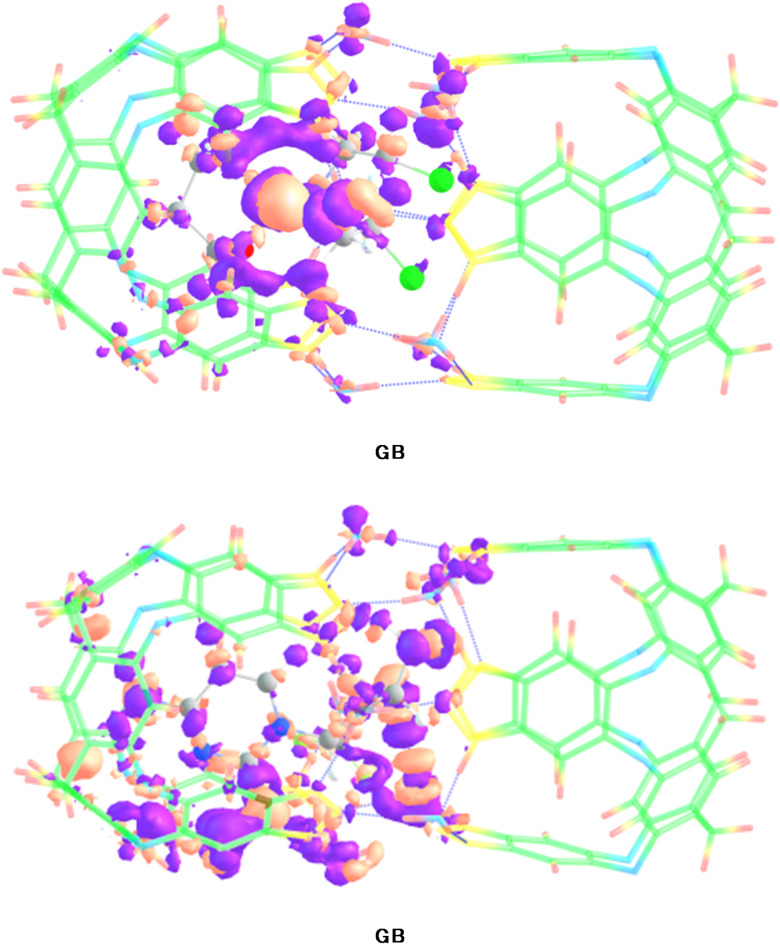

Reduced density gradient analysis

RDG analysis is a powerful tool for characterizing and differentiating the noncovalent interactions. The difference in different noncovalent interactions is based on the colors of contours i.e., blue, green and red patches indicate the presence of hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, and steric repulsions. RDG analysis provides clear picture of non-covalent interactions50.

The colored 3D patches and 2D-RDG graphs are given in Fig. 4. In 3D images, green and brownish patches appear between drugs and nanocapsule, which shows that the presence of weak van der Waals forces.

Fig. 4.

NCI 3D isosurfaces and 2D-RDG plots of stable CP@Capsule and GB@Capsule complexes at isovalue of 0.004 a.u. (red, green and blue color indicate steric repulsions, weak van der Waal’s forces and blue hydrogen bonding.

For CP@Capsule, the green patches are observed between the nanocapsule and the drug molecule which represents the existence of weak van der Waals forces. Similarly, in the 2D map the green colored spikes projected between − 0.01 and − 0.02 a.u. along X-axis corroborate the presence of weak van der Waals forces. Moreover, the blue colored spikes appear over − 0.03 a.u. corroborates the stabilization of CP drug inside the cavity of nanocapsule through hydrogen bonding. This hydrogen bonding is present mainly due to the interaction of oxygen atoms of nanocapsule and hydrogen atoms of CP drug.

For GB@Capsule, 3D structures reveal blue spikes mainly between H atoms of the drug and O atoms of capsule confirm the presence of hydrogen bonding. The green patches in 3D structure of GB@Capsule are more prominent as compared to CP@Capsule complex, which depict the higher stability of this complex. Moreover, these results are also strongly correlated with the interactions energy analysis. In the 2D graphs, the scattered green spikes appear in the range of 0.005 a.u. to -0.015 a.u. for GB@Capsule complex reveals weak van der Waals forces. Moreover, the red colored patches in the center of hexagon rings in both the considered complexes confirm the presence of steric repulsions (Fig. 4).

Similarly, higher negative signλ2(ρ) and deep RDG corroborates the exsitence of strong electrostatic interactions (hydrogen bonding). Moreover, in 2D graphs depict, the spikes present at signλ2(ρ) > −0.015 (a.u.) present electrostatic interactions or hydrogen bonding, whereas below − 0.015 (a.u.) value London dispersion forces exist. Moreover, these results shows that the noncovalent interactions are present between the drug and capsule which facilitates the easy release of drug at the target site.

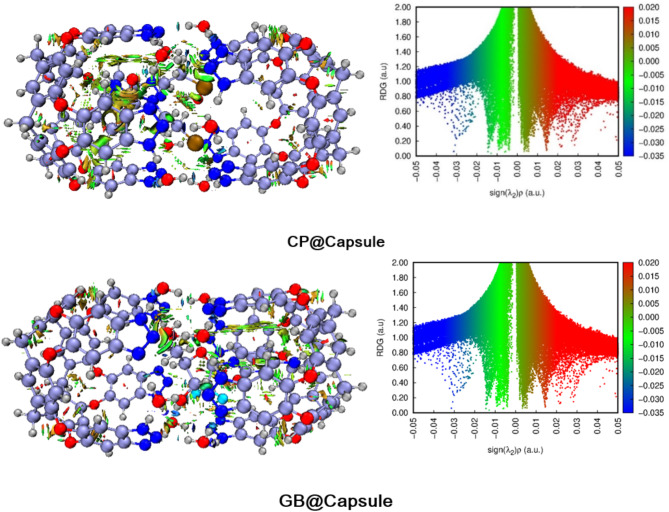

Quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) analysis

The noncovalent interactions between drugs and capsule are further examined through Bader’s QTAIM analysis. The calculated values of topological parameters of the considered drug@Capsule complexes through QTAIM analysis are listed in Table 2. Whereas the 3D topological isosurfaces of drug@capsule complexes are presented in Fig. 5. The values of total density of electrons (ρ) and Laplacian (∇2ρ) given in Table 2 justified the noncovalent interactions in both studied drugs@capsule complexes. 09 BCPs are present in case of CP@Capsule complex with two Cl…O, two Cl—N, two H…N, one O…C, one H…O, and one H…C bond interactions. The electronic density and Laplacian values are observed in the range of 0.001 a.u. to 0.011 a.u. and 0.014 a.u. to 0.040 a.u., respectively. The values of electronic density and Laplacian clearly show the presence of noncovalent interactions. Remaining parameters such as total electronic energy H(r), Potential energy V(r), and Lagrangian kinetic energy G(r) are also observed in the noncovalent weak interactions range (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Topological parameters for studied drugs@capsule complexes obtained through QTAIM analysis.

| Analyte C2N | ρ (a.u) | ∇2ρ (a.u) | G (r) (a.u) | V (r) (a.u) | H (r) (a.u) | −V/G | Eint (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP@Capsule | |||||||

| Cl226…O210 | 0.009 | 0.036 | 0.007 | −0.0062 | 0.0014 | −0.89 | −1.95 |

| Cl226…N103 | 0.008 | 0.028 | 0.006 | −0.0052 | 0.0009 | −0.87 | −1.63 |

| Cl226…N119 | 0.008 | 0.026 | 0.005 | −0.0047 | 0.0009 | −0.94 | −1.47 |

| H249…N194 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.004 | −0.0034 | 0.0008 | −0.85 | −1.07 |

| Cl225…O204 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.002 | −0.0020 | 0.0007 | −1.00 | −0.63 |

| O229…C166 | 0.011 | 0.040 | 0.009 | −0.0081 | 0.0010 | −0.90 | −2.54 |

| H243…C145 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.004 | −0.0022 | 0.0008 | −0.55 | −0.69 |

| H226…N197 | 0.001 | 0.033 | 0.007 | −0.0066 | 0.0008 | −0.94 | −2.07 |

| H250…O207 | 0.009 | 0.031 | 0.007 | −0.0031 | 0.0008 | −0.44 | −0.97 |

| GB@Capsule | |||||||

| O227…N195 | 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.004 | −0.0037 | 0.0006 | −0.93 | −1.16 |

| O230…C136 | 0.009 | 0.032 | 0.007 | −0.0061 | 0.0009 | −0.87 | −1.91 |

| F225…N162 | 0.012 | 0.053 | 0.012 | −0.0113 | 0.0010 | −0.94 | −3.55 |

| F226…O213 | 0.010 | 0.051 | 0.011 | −0.0092 | 0.0018 | −0.84 | −2.89 |

| F226…N193 | 0.013 | 0.053 | 0.012 | −0.0114 | 0.0009 | −0.95 | −3.58 |

| H249…N179 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.005 | −0.0045 | 0.0007 | −0.90 | −1.41 |

| O222…O228 | 0.009 | 0.037 | 0.008 | −0.0073 | 0.0009 | −0.91 | −2.29 |

| H246…O216 | 0.008 | 0.026 | 0.005 | −0.0054 | 0.0005 | −1.08 | −1.69 |

| H233…C107 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.002 | −0.0024 | 0.0005 | −1.20 | −0.75 |

| N232…C109 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.005 | −0.0043 | 0.0007 | −0.93 | −1.16 |

Fig. 5.

QTAIM analysis of studied drugs@Capsule complexes and orange-colored dots indicate the BCPs, whereas yellow lines between drug and capsule shows bond paths.

Similarly, 10 BCPs are observed for GB@capsule complex with one O…N, one O…C bond, one F…O, two F…N, one H…N, one O…O, one H…O, one H…C, and one N…C interactions. The highest interaction is seen for H11…N5 bond with electronic density value of 0.004 a.u. and Laplacian of 0.013 a.u. Overall, the values of electron density (ρ) are in range of 0.004 to 0.013 a.u. and Laplacian (∇2ρ) 0.013 to 0.053 a.u., respectively which indicate the presence of noncovalent interactions between drug and capsule surface.

Furthermore, the ratio of -V/G for each BCPs is computed for both the considered drugs@Capsule complexes (see Table 2). The largest individual values of -V/G for considered complexes i.e., CP@Capsule and GB@Capsule are 0.94, and 0.95, respectively. Additionally, the ratio of -V/G also indicate that V(r) parameter is dominant in both drugs@capsule complexes. Potential energy increase is associated with increase in electron density and Laplacian. The values of electron density, Laplacian, and -V/G also confirms that noncovalent interactions exist in both the studied complexes.

Moreover, the calculated topological parameters i.e., electronic density, Laplacian, total energy density, potential and kinetic energy for the studied drug@Capsule complexes reveal that only noncovalent interactions exist between drugs and capsule surface. Further in the studied drugs, a smaller number of BCPs are seen in the case of CP@Capsule i.e., nine. Furthermore, the topological parameters have lower values for CP@capsule complex as compared to the other complex.

Electronic characteristics

Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis

Upon complexation of drugs with nanocapsule, the amount of charge transfer is quantized with the help of NBO analysis. Electronic parameters play a crucial role in studying the presence of interactions between drugs and nanocapsule. The calculated values of natural bond orbital charges upon complexation are presented in Table S2. NBO charges have two values: a positive value that indicates the charge is transferred from the drug to the nanocapsule, and a negative value that indicates the charge is transferred from the nanocapsule to the interacting drug molecule51.

The computed NBO values presented in Table S2 show that the values are negative for both considered drugs@Capsule complexes. The magnitude of NBO charges on studied drugs is observed in the range of −0.046 e− to −0.058 e−. The negative sign on the magnitude of NBO charges indicates that the NBO charge is being transferred from nanocapsule to drug molecules for both drugs@Capsule complexes.

NBO analysis further reveals that GB@Capsule shows relatively higher charge transfer due to the presence of fluorine atom (highly electronegative) which attracts the electronic cloud with greater force than that of chlorine atom present in cyclophosphamide. The maximum NBO charge of -0.058 e− in the case of GB@Capsule is due the presence of electronegative atoms such as fluorine, oxygen and nitrogen. Similarly, NBO charge of -0.046 e− is calculated for CP@Capsule due to the existence of chlorine atoms which have higher electronegativity than carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen of the nanocapsule. These quantitative charge transfer results are further corroborated through EDD analysis (3D isosurfaces).

Electron density differences (EDD) analysis

The mode of charge transfer upon complexation is visually depicted through EDD analysis. The 3D isosurfaces of drugs@Capsule with Isovalue of 0.0004 a.u. are presented in Fig. 6. The isosurfaces are generated by using Multiwfn 3.7 package49.

Fig. 6.

EDD plots of drugs@capsule with Blue isosurfaces represent electron density accumulation, and red isosurfaces shows electron density depletion (Isovalue = 0.004 a.u.).

In EDD analysis, the red and blue contours indicate the presence of orbital interaction upon complexation between nanocapsule and drugs molecules (Fig. 6). Herein, the blue colored isosurfaces reveal the accumulation of electronic cloud, whereas red colored isosurfaces display the depletion of electronic cloud. Blue colored contours are seen due to the presence of electrostatic interaction of hydrogen atoms of drug molecules and nitrogen atoms of capsule surface, which leads to higher accumulation of electron density between drugs and capsule surface. Moreover, these blue and red surfaces also confirm the transfer of charge from nanocapsule towards drug molecules. EDD isosurfaces show the shifting of electronic density between anticancer drug molecules and nanocapsule. The results of EDD analysis show strong agreement with the NBO charge transfer analysis.

Dipole moment (µ) analysis

Finding the solubility of an anticancer drug molecule and facilitating its easy release at the site of action is made possible by the analysis of variations in the dipole moment’s magnitude. Before the medications are adsorbed, the dipole moment (ε) of the bare capsule is zero. The symmetric structure, which cancels the separate dipoles, may be the reason of this. Furthermore, the dipole moment values for CP and GB, respectively, for isolated drug molecules are 6.06 D and 5.44 D. The medications CP and GB interact with the capsule to produce complexes with dipole values of 6.34 D and 2.77 D, respectively. The formation of new dipoles at the system’s electron-donating and electron-withdrawing regions, where the medicines and capsule interact along particular interaction distances, causes the dipole moment’s amplitude to rise. Drug molecules’ mobility within a biological system is further aided by the complexes’ solubility in aqueous mediums, which is dependent on their dipole moment. The CP@Capsule exhibits a notable rise in the dipole moment value, suggesting that the CP medication is more attractive to biological systems than the GB drug. Therefore, compared to the GB drug molecule, the capsule may effectively release the CP medication on a target site, according to dipole moment study.

Drug release (pH effect)

The release of the drug from the drug carrier vehicle at the target site is the most important stage in the drug delivery process. Compared to the environment surrounding healthy blood cells (pH ≈ 7.35–7.45), the malignant (tumor) cell typically has a lower pH (pH < 6)52. To comprehend the drug release mechanism, it is important to examine the pH influence on the complexes of CP@Capsule and GB@Capsule that have been examined. DFT simulations are run in an acidic environment using two medicines (CP and GB) that are put into capsules. The examined capsule protonates the ends (N-atoms) with a proton to test the pH effect, and then it reoptimizes the complexes at the theoretical M06-2X/6-31G(d, p) level. A significant reduction in the interaction energy values from − 41.83 to − 53.39 to − 7.19 and − 3.63 kcal/mol is noted when comparing the interaction energy values of the CP@Capsule and GB@Capsule complexes during protonation (acidic environment). In a similar vein, for both complexes under consideration, interaction distances grow. The O—H bond distance increases from 2.73 Å to 2.91 Å in the case of GB@Capsule, whereas the O—H interaction distance increases from 2.54 Å to 2.95 Å in the case of CP@Capsule (see Figs. 3 and 7). To summarise, the observed rise in interaction distances and fall in interaction energy suggest that the anticancer medications under study can be readily released from the nanocapsule carrier at the intended place. Additionally, structural deformation is seen in both CP@Capsule and GB@Capsule following relaxation (in acidic solutions), which supports the anticancer medications’ facile release at the intended site.

Fig. 7.

Optimized structures of drug-capsule complexes after protonation at M06-2X/6-31G(d, p) level of theory.

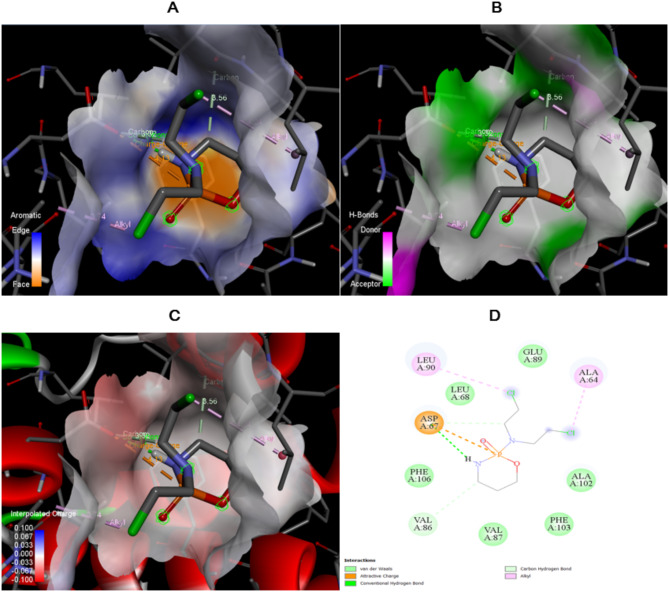

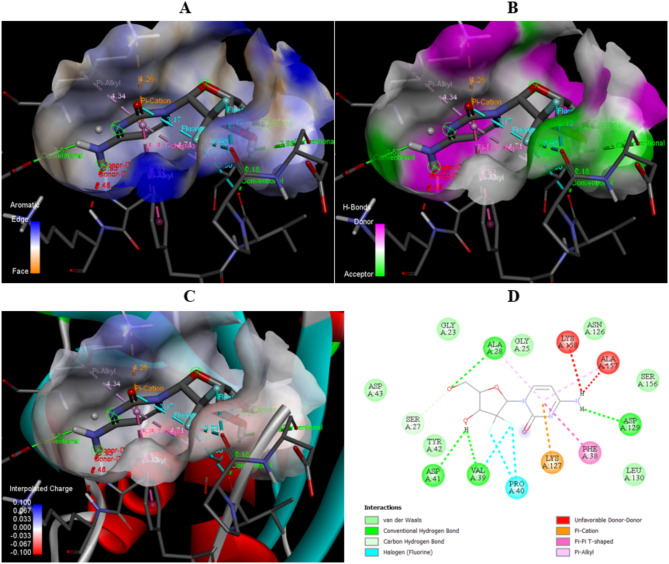

Docking studies

Protein: Human Deoxyribonucleic acid (hDNA).

Ligand: Cyclophosphamide.

This research involves the investigation of interaction between human Deoxyribonucleic acid (hDNA) and ligand Cyclophosphamide by using molecular docking through PyRx software. The 3D structure of the hDNA (PDB ID: 8xp5) downloaded from RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) database and 3D (PubChem ID: 2907) structure of ligand downloaded from PubChem in SDF format. The protein structure prepared by using Discovery studio and then docked by using PyRx software, after this the results visualized through Discovery studio.

Molecular docking results

The results of binding energy, ligand efficiency, and inhibition constant of cyclophosphamide drug with hDNA obtained after the molecular docking given in Table 3. The strength of the interaction between the drug and hDNA depends on the more negative value of binding energy. The low value of inhibition constant indicating the drug is the most potent inhibitor and higher Ki value indicating weaker inhibition.

Table 3.

Binding energy, ligand efficiency and inhibition constant of Cyclophosphamide with Hdna.

| Ligand | Protein | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Ligand efficiency (kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant (ki) (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide | Human deoxyribonucleic acid (hDNA) | −4.6 | −0.329 | 424.45 µM |

The detailed interactions between cyclophosphamide and hDNA given in Table 4 with specific amino acid and the corresponding distances between the interactions. There are multiple bonds forms between drug and target such as conventional hydrogen bond ensuring strong binding between cyclophosphamide and hDNA, alkyl involves in stability of the protein- ligand complex, carbon hydrogen bond, and attractive charge. All the interactions diagrams are shown in Fig. 8.

Table 4.

Binding interactions of Cyclophosphamide with human deoxyribonucleic acid (hDNA).

| Ligand | Amino acid | Interactions | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide | N: UNK1:P - A: ASP67:OD2 | Attractive charge | 4.12506 |

| N: UNK1:H - A: ASP67:OD2 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 2.1186 | |

| N: UNK1:C - A: VAL86:O | Carbon Hydrogen bond | 3.56399 | |

| N: UNK1:C - A: ASP67:OD2 | Carbon Hydrogen bond | 3.32042 | |

| A: ALA64 - N: UNK1:Cl | Alkyl | 3.73983 | |

| N: UNK1:Cl - A: LEU90 | Alkyl | 4.2366 |

Fig. 8.

The interaction diagram of Cyclophosphamide with Human Deoxyribonucleic acid (hDNA) in terms of (A) Aromatic, (B) H-bonds, (C) 3D structure of interpolated charges, and (D) 2D diagram.

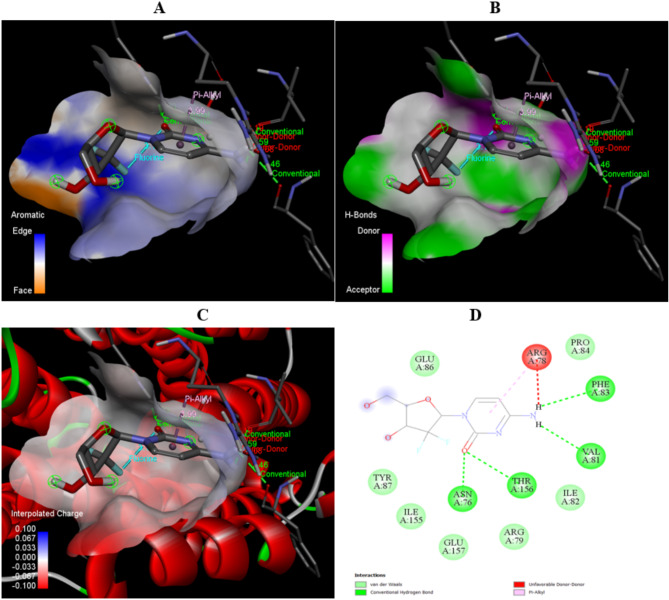

Protein: Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 (RRM2), Mutated KRAS (mKRAS).

Ligand: Gemcitabine.

The molecular docking via PyRx performed to investigate the interaction of gemcitabine drug with its two targets ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 (RRM2) and mutated KRAS (mKRAS). The 3D structure of the ligand gemcitabine (PubChem ID: 60750) from PubChem database in SDF format. The structure of targets (PDB ID: 3vpn, PDB ID: 7txh) obtained from RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) database. The protein structure prepared from Discovery studio by removing water and ligands attached, and hydrogens added. The targets were docked by gemcitabine drug using PyRx and resulting interactions are visualized in Discovery studio visualizer.

Molecular docking results

After docking process, the binding energies, ligand efficiencies, and inhibition constant of the drug and target complex given in Table 5. More negative binding energies corresponding to more stronger interactions of the complex such as in mutated KRAS (mKRAS) complex having − 7 binding energy. The low value of inhibition constant in mutated KRAS complex showing that it is a most potent inhibitor. On the other hand, higher values of Ki in RRM2 indicating weaker inhibition.

Table 5.

The binding energy, ligand efficiency, and inhibition constant of Gemcitabine with Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 (RRM2) and mutated KRAS (mKRAS).

| Ligand | Protein | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Ligand efficiency (kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant (ki) (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemcitabine | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 (RRM2) | -6.7 | −0.372 | 12.256 |

| Mutated KRAS (mKRAS) | -7 | −0.389 | 7.386 |

The detailed interactions between gemcitabine and the targets: RRM2 and mKRAS given in Table 6. In RRM2 complex, the interactions present are conventional Hydrogen bond, Halogen, and Pi alkyl. The conventional Hydrogen bond ensuring the strong binding between the complex, Halogen interactions contribute to complex interaction by improving the specificity, and Pi alkyl interactions are involved in improvement of binding affinity of drug with target. In mKRAS complex, there are Conventional hydrogen bond, halogen, Pi- cation, Pi-Pi- T- shaped and Pi alkyl interactions are present. The Pi- cation and Pi- Pi T- shaped interactions contributes toward specificity and binding affinity of drug toward the target, and Pi- alkyl interactions involved in the stability of the complex. All the visual illustration of the RRM2 and mKRAS complex with Gemcitabine given in Figs. 9 and 10.

Table 6.

The binding interactions of Gemcitabine with Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 (RRM2) and mutated KRAS (mKRAS).

| Ligand | Amino acid | Interactions | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 (RRM2) | |||

| Gemcitabine | A: ASN76:HD22 - N: UNK1:O | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 1.79845 |

| A: THR156:HN - N: UNK1:O | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 2.34548 | |

| N: UNK1:H - A: PHE83:O | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 2.46439 | |

| N: UNK1:H - A: VAL81:O | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 2.59163 | |

| N: UNK1:O - N: UNK1:F | Halogen (Fluorine) | 3.13723 | |

| N: UNK1 - A: ARG78 | Pi-Alkyl | 3.98543 | |

| Mutated KRAS (mKRAS) | |||

| Gemcitabine | A: ALA28:HN - N: UNK1:O | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 2.40076 |

| N: UNK1:H - A: ASP129:OD1 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 2.57188 | |

| N: UNK1:H - A: VAL39:O | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 2.1797 | |

| N: UNK1:H - A: ASP41:O | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | 2.95598 | |

| A: SER27:CB - N: UNK1:O | Carbon Hydrogen Bond | 3.55975 | |

| A: VAL39:O - N: UNK1:F | Halogen (Fluorine) | 3.30423 | |

| A: PRO40:O - N: UNK1:F | Halogen (Fluorine) | 3.03133 | |

| A: PRO40:O - N: UNK1:F | Halogen (Fluorine) | 3.13326 | |

| N: UNK1:O - N: UNK1:F | Halogen (Fluorine) | 3.16528 | |

| A: LYS127:NZ - N: UNK1 | Pi-Cation | 4.26415 | |

| A: PHE38 - N: UNK1 | Pi-Pi T-shaped | 4.91878 | |

| N: UNK1 - A: ALA28 | Pi-Alkyl | 4.71134 | |

| N: UNK1 - A: LYS127 | Pi-Alkyl | 4.34111 | |

| N: UNK1 - A: ALA157 | Pi-Alkyl | 5.13389 | |

Fig. 9.

The visual representation of interactions between Gemcitabine and Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 (RRM2) in terms of (A) aromatic, (B) H-bonds, (C) 3D structure of interpolated charges, (D) 2D diagram of interactions.

Fig. 10.

The visual representation of interactions of Gemcitabine with Mutated KRAS (mKRAS) in terms of (A) Aromatic, (B) H-bonds, (C) 3D structure of interpolated charges, and (D) 2D diagram of interactions.

Conclusion

Herein, the targeted drug delivery ability of nanocapsule is performed against anticancer drugs through DFT at M06-2X/6-31G(d, p) level of theory. Binding energy results reveal that GB@Capsule complex is thermodynamically more stable with higher Eint of (−56.64 kcal/mol) as compared to CP@Capsule (−43.34 kcal/mol). Moreover, QTAIM analysis validates the higher stability of GB@capsule complex which is mainly due to the presence of strong electrostatic interactions. The values of electron density, Laplacian, and −V/G ratio characterized through QTAIM analysis reveal the existence of noncovalent interactions between anticancer drug molecules and nanocapsule. Noncovalent interaction (NCI) analysis also indicates the presence of weak van der Waals interactions corroborated through the presence of green spikes among drug molecules and nanocapsule. Electronic properties analysis reveals the significant reduction in H-L energy gap upon complexation. The dipole moment of capsule was zero, but the value increased to 6.34 D and 2.77 D after interaction of CP and GB, respectively, suggesting more solubility and easy release of CP@Cap complex in biological systems. The increase in interaction distances and decrease in interaction energies indicate that anticancer drugs can easily be released at the targeted site due to the acidic pH of malignant cells compared to the normal cells. Key findings of the present study distinctly indicate the better performance of nanocapsule for anticancer drug delivery.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Universiti Brunei Darussalam for the research grant (UBD/RSCH/1.4/FICBF/2024/067) and EVPVA fund (UBD/OAVCR/EVPVA/LA/Jan24-27).

Author contributions

A.S.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-original draft. S.S.: Software, Methodology, Writing-original draft. M. H. S. A. H.: Conceptualization, validation, Funding. N.A.K: Methodology, Visualization, Funding. A.L.: Software, Validation. N.S.S.: Funding acquisition, Validation, Investigation. K.A.: Supervision, Writing-review & editing.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nadeem S. Sheikh, Email: nadeem.sheikh@ubd.edu.bn

Khurshid Ayub, Email: khurshid@cuiatd.edu.pk.

References

- 1.Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin.68 (6), 394–424 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien, N. A. et al. Tucatinib has selective activity in HER2-positive cancers and significant combined activity with approved and novel breast cancer–targeted therapies. Mol. Cancer Ther.21 (5), 751–761 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng, W. J. et al. Bispecific T-cell engagers non-covalently decorated drug-loaded pegylated nanocarriers for cancer immunochemotherapy. J. Control. Release. 344, 235–248 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corti, A. et al. Targeted drug delivery and penetration into solid tumors. Med. Res. Rev.32 (5), 1078–1091 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahrami, B. et al. Nanoparticles and targeted drug delivery in cancer therapy. Immunol. Lett.190, 64–83 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steichen, S. D., Caldorera-Moore, M. & Peppas, N. A. A review of current nanoparticle and targeting moieties for the delivery of cancer therapeutics. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.48 (3), 416–427 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutta, B. et al. Glutamic acid-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles for tumor-targeted imaging and therapeutics. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 112, 110915 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, Z. et al. Nanomaterials for cancer therapy: current progress and perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol.14 (1), 1–27 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Koker, S., Hoogenboom, R. & De Geest, B. G. Polymeric multilayer capsules for drug delivery. Chem. Soc. Rev.41 (7), 2867–2884 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoosefian, M. & Sabaghian, H. Silver nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems in the fight against COVID-19: enhancing efficacy, reducing toxicity and improving drug bioavailability. J. Drug Target.32 (7), 794–806 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasani, M. et al. In vitro and in Silico characteristics of doxorubicin-loaded four polymeric-based polysaccharides-modified super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for cancer chemotherapy and magnetic resonance imaging. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 73 (2), 117–130 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Najafi, V., Yoosefian, M. & Hassani, Z. Development of venetoclax performance using its new derivatives on BCL-2 protein Inhibition. Cell Biochem. Funct.41 (1), 58–66 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansarinik, Z., Kiyani, H. & Yoosefian, M. Investigation of self-assembled Poly (ethylene glycol)-poly (L-lactic acid) micelle as potential drug delivery system for poorly water soluble anticancer drug abemaciclib. J. Mol. Liq.365, 120192 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoosefian, M., Fouladi, M. & Atanase, L. I. Molecular dynamics simulations of docetaxel adsorption on graphene quantum Dots surface modified by PEG-b-PLA copolymers. Nanomaterials12 (6), 926 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fei, Z. & Yoosefian, M. Design and development of polymeric micelles as nanocarriers for anti-cancer ribociclib drug. J. Mol. Liq.329, 115574 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sargazi-Avval, H. et al. Potential applications of armchair, zigzag, and chiral Boron nitride nanotubes as a drug delivery system: letrozole anticancer drug encapsulation. Appl. Phys. A. 127, 1–7 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, W. & Huang, Y. Cell membrane-engineered nanoparticles for cancer therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 10 (37), 7161–7172 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, M. et al. Targeted nanodrugs to destroy the tumor extracellular matrix barrier for improving drug delivery and Cancer therapeutic efficacy. Mol. Pharm.20 (5), 2389–2401 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fayyaz, F. et al. First principles calculations of the adsorption of fluorouracil and nitrosourea on CTF-0; organic frameworks as drug delivery systems for cancer treatment. J. Mol. Liq.356, 118941 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang, L. et al. Overcoming drug-resistant lung cancer by Paclitaxel loaded dual-functional liposomes with mitochondria targeting and pH-response. Biomaterials52, 126–139 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, G. et al. Two-dimensional magnetic WS2@ Fe3O4 nanocomposite with mesoporous silica coating for drug delivery and imaging-guided therapy of cancer. Biomaterials60, 62–71 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou, Y. et al. Engineering a photosensitizer nanoplatform for amplified photodynamic immunotherapy via tumor microenvironment modulation. Nanoscale Horiz. 6 (2), 120–131 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardikis, K. et al. New drug delivery nanosystem combining liposomal and dendrimeric technology (liposomal locked-in dendrimers) for cancer therapy. J. Pharm. Sci.99 (8), 3561–3571 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh, Y. K. & Park, T. G. SiRNA delivery systems for cancer treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.61 (10), 850–862 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samanta, P. N. & Das, K. K. Noncovalent interaction assisted fullerene for the transportation of some brain anticancer drugs: a theoretical study. J. Mol. Graph. Model.72, 187–200 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, J., Cui, L. & Losic, D. Graphene and graphene oxide as new nanocarriers for drug delivery applications. Acta Biomater.9 (12), 9243–9257 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szefler, B. Nanotechnology, from quantum mechanical calculations up to drug delivery. Int. J. Nanomed., : pp. 6143–6176. (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Lee, J. H. & Yeo, Y. Controlled drug release from pharmaceutical nanocarriers. Chem. Eng. Sci.125, 75–84 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, J. & Chan, J. J. Cyclophosphamide in dermatology. Australas. J. Dermatol.58 (1), 5–17 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarvepalli, D. et al. Gemcitabine: a review of chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncog., 24(2). (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Samimi, S., Ardestani, M. S. & Dorkoosh, F. A. Preparation of carbon quantum dots-quinic acid for drug delivery of gemcitabine to breast cancer cells. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol.61, 102287 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohamad Saimi, N. I. et al. Aerosolized niosome formulation containing gemcitabine and cisplatin for lung cancer treatment: optimization, characterization and in vitro evaluation. Pharmaceutics13 (1), 59 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cram, D. J. Cavitands: organic hosts with enforced cavities. Science219 (4589), 1177–1183 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinalli, R. et al. Cavitand-based nanoscale coordination cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc.126 (21), 6516–6517 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malinowska, E. et al. Potentiometric studies of complexation properties of tetrafunctionalized resorcinarene-based cavitands. New J. Chem.27 (10), 1440–1445 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu, X. et al. Confinement effect on molecular conformation of alkanes in water-filled cavitands: a combined quantum/classical density functional theory study. Langmuir34 (45), 13491–13496 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dumele, O., Trapp, N. & Diederich, F. Halogen bonding molecular capsules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.54 (42), 12339–12344 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guan, H. W. et al. Recognition of hydrophilic molecules in deep cavitand hosts with water-mediated hydrogen bonds. Chem. Commun.57 (66), 8147–8150 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahman, F. U. et al. Binding and assembly of a benzotriazole cavitand in water. Angew. Chem.134 (29), e202205534 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yar, M. et al. Adsorption and sensor applications of C2N surface for G-series and mustard series chemical warfare agents. Microporous Mesoporous Mater.317, 110984 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaussian09, R. A. 1, Mj Frisch, Gw Trucks, Hb Schlegel, Ge Scuseria, Ma Robb, Jr Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, B. Mennucci, G. Petersson et al. Gussian. 121, 150–166. (2009).

- 42.Wang, Y. et al. Revised M06 density functional for main-group and transition-metal chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.115 (41), 10257–10262 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan, S. et al. First-principles study for exploring the adsorption behavior of G-series nerve agents on graphdyine surface. Comput. Theor. Chem.1191, 113043 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, C. et al. A DFT study on the high-density assembly of doxorubicin drug delivery by single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. E. Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct.134, 114892 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saikia, N. & Deka, R. C. Density functional calculations on adsorption of 2-methylheptylisonicotinate antitubercular drug onto functionalized carbon nanotube. Comput. Theor. Chem.964 (1), 257–261 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoosefian, M., Pakpour, A. & Etminan, N. Nanofilter platform based on functionalized carbon nanotubes for adsorption and elimination of acrolein, a toxicant in cigarette smoke. Appl. Surf. Sci.444, 598–603 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hussain, R. et al. Density functional theory study of palladium cluster adsorption on a graphene support. RSC Adv.10 (35), 20595–20607 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jadoon, T., Mahmood, T. & Ayub, K. Silver-graphene quantum Dots based electrochemical sensor for trinitrotoluene and p-nitrophenol. J. Mol. Liq.306, 112878 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem.33 (5), 580–592 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sajid, H. et al. Cyclic versus straight chain oligofuran as sensor: A detailed DFT study. J. Mol. Graph. Model.97, 107569 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rad, A. S. & Ayub, K. O3 and SO2 sensing concept on extended surface of B12N12 nanocages modified by nickel decoration: a comprehensive DFT study. Solid State Sci.69, 22–30 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alkhalifah, M. A. et al. Covalent organic framework (C6N6) as a drug delivery platform for fluorouracil to treat cancerous cells: a DFT study. Materials15 (21), 7425 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information.