Abstract

Academic self-efficacy (ASE), the belief in one’s ability to succeed in academic tasks, plays a crucial role in student motivation, learning, and performance. Reliable measurement of this construct is essential for identifying students’ strengths and areas for improvement. This study aims to translate and validate the Academic Self-Efficacy Scale for use among university students from six different Arab countries. Using the Snowball sampling technique, participants (n = 2131), university students six Arab countries (i.e., KSA, UAE, Egypt, Lebanon, Oman, and Kuwait), answered the demographic questions and completed the Arabic Academic Self-Efficacy Scale, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-8, and the Multidimensional Social Support Scale. Confirmatory Factor Analysis proved a one-factor solution for the ASE scale. Adequate composite reliability was found (ω =.96; α =.96). Convergent and concurrent validity was assessed and proven by a negative correlation with measures of psychological distress and positive correlation with measures of social support. Our translation of the ASE scale was invariant across sexes and countries, with females scoring significantly higher than males. Our Arabic version of the ASE scale is a validated and reliable tool for assessing ASE in Arabic speaking populations, and shall provide means for assessing students’ confidence in their academic abilities and help improve student support.

Keywords: Academic self-efficacy, Psychometric properties, Arabic

Subject terms: Psychology, Human behaviour

Introduction

Academic success is shaped by a constellation of psychological indicators that intertwine to influence a student’s performance and perseverance. At the core is self-efficacy, where students with strong beliefs in their academic capabilities show greater persistence and are more likely to excel1. Academic self-efficacy plays a crucial role in students’ educational journeys by shaping their beliefs in their ability to perform and excel in academic tasks. This confidence influences how students approach learning challenges, with those possessing higher academic self-efficacy demonstrating greater persistence, resilience, and willingness to tackle difficult coursework1. It also directly correlates with improved academic performance and better stress management, as students with strong self-efficacy can better regulate their emotional responses and maintain a positive outlook in the face of setbacks2. Furthermore, academic self-efficacy serves as a buffer against adversity, promoting academic resilience by fostering positive coping strategies and encouraging students to seek support when needed3.

Academic self-efficacy is influenced by a range of factors that shape how students perceive their academic capabilities. Mastery experiences, or direct successes in academic tasks, are considered the most influential factor, as repeated successes reinforce students’ belief in their ability to achieve future goals1. Vicarious experiences, where students observe their peers achieving success, also contribute, as students are more likely to believe they can succeed if they see others like them do so4. Verbal persuasion, in the form of encouragement from teachers, peers, or family, can strengthen self-efficacy, particularly when delivered in supportive and credible ways5. Also, emotional and physiological states, such as stress or anxiety, can undermine self-efficacy by making students feel less capable, while positive emotional experiences can enhance it3. In addition to that, the association between academic self-efficacy and social support is well-established, showing that social support significantly boosts students’ belief in their academic abilities. Chen et al.6 found that high perceived social support enhances academic self-efficacy among preservice special education teachers in China. Hussain et al.7 demonstrated that social support mediates the relationship between academic motivation and self-efficacy. Similarly, Zander et al.8 showed that students integrated into social support networks report higher academic self-efficacy, improving their academic performance.

Academic self-efficacy is deeply rooted in various psychological theories, primarily within the framework of Albert Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory4, which underscores its pivotal role in behavioral regulation and personal agency. Bandura posits that self-efficacy influences the choices people make, the effort they expend, their resilience to adversity, and the extent of their success. This theory highlights the dynamic interaction between behaviors, personal factors, and environmental influences4. Further extending this framework, self-efficacy aligns with Self-Determination Theory by Ryan and Deci9, where it contributes to intrinsic motivation by satisfying basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. In this context, self-efficacy enhances a student’s motivation by fostering a belief in their competence, thereby increasing their intrinsic motivation to engage in and persist with academic tasks9. In Expectancy-Value Theory10, academic self-efficacy forms part of the expectancy construct, influencing students’ expectations of success, which together with the value they attach to the task, determines their task choice and performance persistence. This suggests that a student’s belief in their capability greatly influences their expectancy of success, which in turn impacts their academic engagement and achievement10. Moreover, in Goal Theory11, academic self-efficacy is crucial in defining goal orientation. Students with high self-efficacy are more likely to adopt mastery goals, focusing on learning and understanding, which are linked to deeper engagement and better academic outcomes. Conversely, low self-efficacy may predispose students towards performance-avoidance goals, where the emphasis is on avoiding failure rather than on achieving personal mastery11. These theoretical connections underline the importance of academic self-efficacy not only as a predictor of academic performance but also as a vital component of motivational psychology, impacting students’ learning processes, emotional regulation, and overall academic behaviors.

Several scales have been designed to measure academic self-efficacy, including the General Academic Self-Efficacy Scale12, Academic and Social Self-Efficacy Scale13, and Self-Efficacy and Test Anxiety Scales14. The Academic Self-Efficacy Scale15 developed by M. M. Chemers is distinctive because it is designed specifically to assess self-efficacy within the context of college environments, focusing on the unique challenges and tasks that students face in higher education settings. This scale is particularly noted for its ability to predict academic performance effectively through its tailored approach to measuring self-efficacy in academic tasks. Furthermore, Chemers’ scale is unique because it emphasizes the multifaceted nature of academic tasks in college, such as handling academic stress, coping with a diverse range of coursework, and navigating the social and administrative aspects of college life15. This comprehensive approach allows the scale to capture a broad spectrum of self-efficacy beliefs related to both academic and social tasks, providing a nuanced view of how self-efficacy influences student success in a university setting15. Moreover, Chemers’ scale often includes dimensions that assess self-regulatory behaviors, goal-setting abilities, and response to academic challenges, making it a valuable tool for understanding the complex interactions between students’ beliefs in their capabilities and their actual performance outcomes15. This focus on specific, context-relevant factors sets it apart from more general self-efficacy measures that may not account for the unique aspects of the college experience.

In 2001, Chemers et al.15, developed a specialized nine-item Academic Self-Efficacy scale to evaluate first-year college students’ confidence in their academic capabilities. This scale was designed based on the principles outlined by Bandura in 199716, emphasizing a comprehensive assessment of skills essential for academic success. The items on the scale covered a range of academic tasks such as scheduling, note-taking, test-taking, and the skills involved in researching and writing academic papers15. Participants rated their confidence levels using a 7-point Likert scale, reflecting their agreement with statements related to their academic competence. The construction of the scale intentionally avoided focusing on subject-specific skills like math or science to ensure a broader applicability for predicting overall academic performance at college. The inclusion of general statements about scholarly abilities also aimed to capture a holistic view of students’ self-perceived academic efficacy15. Importantly, the scale demonstrated robust reliability with a coefficient alpha of 0.8115, validating its use as an effective measure for this study. In the original study15, the ASE scale showed a one factor solution and was invariable across sexes, meaning it was understood in a similar way by both males and females and measured one construct; i.e., academic self-efficacy. This tool was crucial for gauging how self-efficacy beliefs among students influenced their academic performance and personal adjustment during their initial year at university, providing valuable insights into the psychological factors that contribute to educational outcomes.

The ASE scale has been translated to Arabic by Al Mohazie et al.17 and validated on a group of Arabic-speaking students at King Faisal University in Saudi Arabia. However, the aim of our study is to translate the ASE scale into Arabic and prove its psychometric validities on a sample of Arab speaking students from six different Arab countries. Conducting our study to validate the ASE scale across multiple Arabic-speaking countries is essential for several reasons. The initial validation of the scale17 was limited to students from King Faisal University in Saudi Arabia, and while this provides valuable insights, it does not account for the diverse cultural, social, and educational contexts present in other Arabic-speaking countries. Saudi Arabian society and culture cannot be representative of the rest of Arab countries and cultural backgrounds18. Cross-cultural validation ensures that the scale measures the intended constructs equivalently across different cultural settings, which is crucial for the reliability and validity of the findings. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance studies have demonstrated that scales often need adjustments to maintain their validity across different cultures. In addition, important psychometric properties of the ASE scale have not been assessed in the former validation work, including measurement invariance across sex groups. Therefore, conclusions regarding significant differences in ASE scores between male and female students may be limited and should be interpreted with caution. Investigating both cross-sex and cross-country measurement invariance of the ASE allows researchers and educators in Arabic-speaking regions to accurately assess the construct of academic self-efficacy and to develop culturally-tailored strategies that enhance students’ self-beliefs and academic performance. It also supports broader educational research and comparisons across different cultural contexts, contributing to a more global understanding of academic self-efficacy.

Our objectives are to assess the factor-structure, convergent, and concurrent validity of our Arabic translation of the ASE, in addition to its internal consistency. We hypothesize a one-factor solution similar to the original scale, invariability across sexes and countries, and good concurrent validity through positive correlation with measures of social support and negative correlation with measures of psychological distress.

Methods

Participants

Data was collected through Google Forms. Arabic speaking university students from KSA, UAE, Egypt, Lebanon, Oman, and Kuwait were asked to fill the survey. We selected these six Arab countries based on the willingness and availability of collaborators who agreed to participate in the study. We initially reached out to researchers from various Arab nations, but only those from these six countries accepted our invitation and contributed to the data collection. We employed the Snowball sampling technique, whereby participants are asked to spread the Google Form link to people they know, and then these people spread it to their friends. After providing digital informed consent, participants were permitted to fill out the relevant scales in the Google Form. Participation in our study was completely anonymous, confidential, and voluntary.

Translation procedure

Before being used in this study, the ASE scale was translated and culturally adapted to fit the Arabic language and context. This process ensured semantic consistency between the original and Arabic versions, following international standards and guidelines19. The translation followed a forward and backward method: a Lebanese translator not involved in the study first translated the scale from English to Arabic, and then a Lebanese psychologist fluent in English retranslated it back into English. This method aimed to balance direct and contextual translations. A panel of experts, including two psychiatrists, one psychologist, the research team, and the translators, reviewed both the original and retranslated English versions to resolve any discrepancies and ensure accuracy20. The scale was also adapted to the study context to clarify ambiguities and facilitate interpretation, maintaining its conceptual integrity in both the original and Arabic contexts21. A pilot test confirmed the clarity of the questions, and no further modifications were required.

Questionnaire

Participants in our study provided their age, sex, country of birth, type of major they are studying, and the Household Crowding Index (HCI), which is calculated by dividing the total count of people living in a household, excluding a newborn child, by the total number of rooms in that household, excluding the kitchen22. Additionally, participants were prompted answer the following scales:

The Academic Self-Efficacy Scale15 developed by Chemers et al. to measure college students’ confidence in their academic abilities. The scale consists of 9 items, e.g. “I know how to take notes”, each rated on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 represents strong disagreement and 7 represents strong agreement17. A higher score represents greater academic self-efficacy, and thus students scoring closer to the higher end of the scale are those who believe strongly in their ability to perform academic tasks successfully.

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale- 8 (DASS- 8)23, validated in Arabic, was designed to measure psychological distress, i.e., emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress. The DASS- 8 consists of 8 items, measuring three main factors: depression (e.g., “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to”), anxiety (e.g., “I felt I was close to panic”), and stress (e.g., “I found it difficult to relax”). Respondents answer each item on a 4-point Likert scale. Scores on the DASS- 8 are indicative of the severity of each emotional state. Higher scores denote greater levels of psychological distress24. The Cronbach’s α value was 0.89 in the original study23 and 0.86 in the current one.

The Multidimensional Social Support Scale (MSPSS)25, validated in Arabic26, measures the degree of individual perception of social support from three sources: Family, Friends and a Significant Other. The total number of items is 12 (e.g. “There is a special person who is around when I am in need”). Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert rating scale. Higher scores illustrate stronger perception of social support. The Cronbach’s α value was 0.88 in the original study25 and 0.97 in the current one.

Analytic strategy

There were no missing responses in the dataset. To examine the factor structure of the ASE, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis using the data from the total sample via SPSS AMOS v.29 software. A minimum sample varying between 27–180 participants was deemed necessary to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis following a recommendation between 3–20 times the number of the scale’s variables27. Our intention was to test the original model of the scale. Parameter estimates were obtained using the maximum likelihood method. Calculated fit indices were the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the comparative fit index (CFI). Values ≤ 0.08 for RMSEA, ≤ 0.05 for SRMR and 0.95 for CFI and TLI indicate good fit of the model to the data28. Multivariate normality was not verified at first; therefore, we performed non-parametric bootstrapping procedure.

To examine sex and country invariance of ASE scores, we conducted multi-group CFA29 using the total sample. Measurement invariance was assessed at the configural, metric, and scalar levels30. We accepted ΔCFI ≤ 0.010 and ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015 or ΔSRMR ≤ 0.010 as evidence of invariance29. Comparison between males and females was done using the Student t-test only if scalar or partial scalar invariance. ANOVA test was used to compare scores between countries.

Composite reliability in both subsamples was assessed using McDonald’s ω and Cronbach’s alpha, with values greater than 0.70 reflecting adequate composite reliability. Normality of the ASE score was verified since the skewness and kurtosis values for each item of the scale varied between − 1and + 131. To assess concurrent validity, Pearson test was used to correlate ASE scores with other continuous variables using the total sample.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

A total of 2131 participants filled the survey, with a mean age of 21.78 ± 4.21 years, 72.7% females, 69.0% enrolled in a science major and a mean HCI of 1.31 ± 0.61. The mean ASE score was 35.08 ± 13.48 in the total sample. The description by country can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

| Saudi Arabia (n = 394) | United Arab Emirates (n = 381) | Egypt (n = 225) | Lebanon (n = 318) |

Oman (n = 319) |

Kuwait (n = 494) |

Total (n = 2131) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21.82 ± 4.66 | 21.06 ± 3.44 | 21.21 ± 3.03 | 21.22 ± 3.76 | 21.78 ± 3.37 | 22.94 ± 5.25 | 21.78 ± 4.21 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 151 (38.3%) | 78 (20.5%) | 70 (31.1%) | 97 (30.5%) | 74 (23.2%) | 112 (22.7%) | 582 (27.3%) |

| Female | 243 (61.7%) | 303 (79.5%) | 155 (68.9%) | 221 (69.5%) | 245 (76.8%) | 382 (77.3%) | 1549 (72.7%) |

| Major | |||||||

| Medical | 262 (66.5%) | 286 (75.1%) | 107 (47.6%) | 193 (60.7%) | 242 (75.9%) | 381 (77.1%) | 1471 (69.0%) |

| Non-medical | 132 (33.5%) | 95 (24.9%) | 118 (52.4%) | 125 (39.3%) | 77 (24.1%) | 113 (22.9%) | 660 (31.0%) |

| Household crowding index | 1.34 ± 0.65 | 1.23 ± 0.52 | 1.32 ± 0.59 | 1.32 ± 0.58 | 1.35 ± 0.66 | 1.29 ± 0.62 | 1.31 ± 0.61 |

| Academic self-efficacy | 30.18 ± 11.64 | 35.53 ± 12.79 | 36.07 ± 14.15 | 38.69 ± 13.13 | 35.97 ± 14.23 | 35.28 ± 13.77 | 35.08 ± 13.48 |

Confirmatory factor analysis of the ASE scale

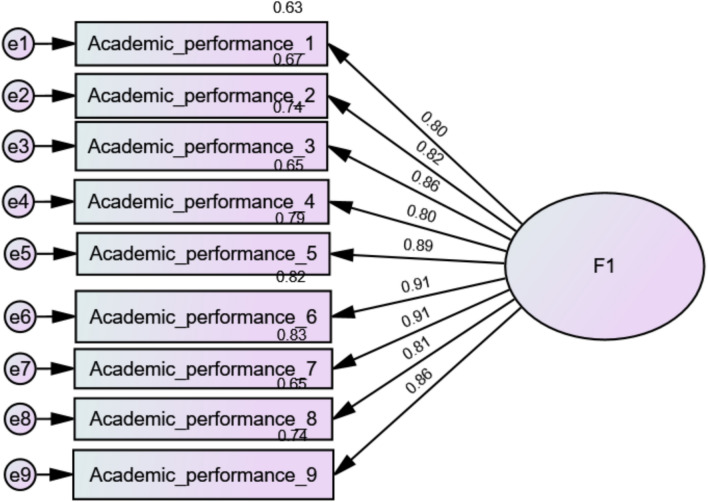

CFA indicated that fit of the one-factor model of ASE scores was excellent: RMSEA = 0.103 (90% CI 0.096, 0.110), SRMR = 0.024, CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.957. The standardised estimates of factor loadings were all adequate (Table 2; Fig. 1). Internal reliability was very good (ω = 0.96; α = 0.96). The AVE value was excellent = 0.73.

Table 2.

Standardised estimates of factor loadings of the 9-item Academic Self-Efficacy scale in the total sample.

| Item | Loading factor |

|---|---|

| 1. I know how to schedule my time to accomplish my tasks | 0.80 |

| 2. I know how to take notes | 0.82 |

| 3. I know how to study to perform well on tests | 0.86 |

| 4. I am good at research and writing papers | 0.80 |

| 5. I am a very good student | 0.89 |

| 6. I usually do very well in school and at academic tasks | 0.91 |

| 7. I understand my academic tasks | 0.91 |

| 8. I find my university academic work is interesting | 0.81 |

| 9. I am very capable of succeeding at the university | 0.86 |

Fig. 1.

Standardised estimates of factor loadings of the 9-item Academic Self-Efficacy scale in the total sample.

Measurement invariance by gender and countries

Indices suggested that configural, metric, and scalar invariance was supported across gender and countries (Table 3). A higher mean ASE score was significantly found in females (M = 35.71, SD = 13.57) compared to males (M = 33.38, SD = 13.11) in the total sample, t(2129) = − 3.57, p < 0.001.

Table 3.

Measurement Invariance across sex and countries in the total sample.

| Model | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Model Comparison | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Gender | |||||||

| Males | 0.969 | 0.101 | 0.024 | ||||

| Females | 0.963 | 0.111 | 0.026 | ||||

| Configural | 0.964 | 0.077 | 0.024 | ||||

| Metric | 0.965 | 0.071 | 0.025 | Configural vs metric | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 |

| Scalar | 0.965 | 0.067 | 0.025 | Metric vs scalar | < 0.001 | 0.004 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2: Countries | |||||||

| KSA | 0.987 | 0.061 | 0.021 | ||||

| UAE | 0.952 | 0.129 | 0.029 | ||||

| Egypt | 0.971 | 0.101 | 0.025 | ||||

| Lebanon | 0.952 | 0.119 | 0.032 | ||||

| Oman | 0.971 | 0.106 | 0.020 | ||||

| Kuwait | 0.942 | 0.134 | 0.038 | ||||

| Configural | 0.961 | 0.046 | 0.021 | ||||

| Metric | 0.960 | 0.042 | 0.025 | Configural vs metric | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Scalar | 0.958 | 0.039 | 0.025 | Metric vs scalar | 0.002 | 0.003 | < 0.001 |

Note. CFI = Comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = Standardised root mean square residual.

The highest ASE scores were found in Lebanese participants (38.69 ± 13.13), followed by Egyptian (36.07 ± 14.15), Omani (35.97 ± 14.23), Emirati (35.53 ± 12.79), Kuwaiti (35.8 ± 13.77) and Saudi (30.18 ± 11.64) participants, F(5, 2125) = 16.17, p < 0.001. The post-hoc Bonferroni analysis showed that the difference between countries in terms of ASE scores was significant, with significant difference seen between KSA and UAE (p < 0.001), KSA and Egypt (p < 0.001), KSA and Lebanon (p < 0.001), KSA and Oman (p < 0.001), KSA and Kuwait (p < 0.001), UAE and Lebanon (p = 0.026), and Lebanon and Kuwait (p = 0.005).

Concurrent validity

Higher depression (r = − 0.17; p < 001), anxiety (r = − 0.14; p < 001), and overall psychological distress (r = − 0.13; p < 001) were significantly associated with lower ASE, whereas higher perceived social support from family (r = 0.43; p < 0.001), from friends (r = 0.40; p < 0.001), and from significant others (r = 0.41; p < 0.001) was significantly associated with higher ASE. The full table of correlations between ASE scores and DASS- 8 and MSPSS total and subscales scores are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Academic self-efficacy | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Psychological distress (DASS- 8 total score) | − 0.13*** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. DASS- 8 Depression | − 0.17*** | 0.90*** | 1 | |||||

| 4. DASS- 8 Anxiety | − 0.14*** | 0.90*** | 0.69*** | 1 | ||||

| 5. DASS- 8 Stress | 0.01 | 0.80*** | 0.59*** | 0.59*** | 1 | |||

| 6. Social support (MSPSS total score) | 0.45*** | − 0.15*** | − 0.18*** | − 0.17*** | 0.001 | 1 | ||

| 7. Perceived social support from family | 0.43*** | − 0.18*** | − 0.21*** | − 0.20*** | − 0.03 | 0.92*** | 1 | |

| 8. Perceived social support from friends | 0.40*** | − 0.12*** | − 0.15*** | − 0.13*** | 0.003 | 0.92*** | 0.75*** | 1 |

| 9. Perceived social support from significant others | 0.41*** | − 0.11*** | − 0.15*** | − 0.13*** | 0.03 | 0.94*** | 0.78*** | 0.80*** |

***p < 0.001. DASS- 8: Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales- 8; MSPSS: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

Discussion

The ASE scale is an instrument designed to measure Academic Self-Efficacy in college students. Our study validated an Arabic translation of the ASE scale and proved its psychometric soundness on a group of Arabic speaking university students from different Arab countries. Our translation of the ASE scale had good factorial, convergent, and concurrent validity. It was also shown that the ASE scale was invariant across sexes.

We obtained a single factor solution for the ASE scale, which means that the scale measures a single variable of self-efficacy, similar to the original scale32and the previous Arabic translation among Saudi students17. Furthermore, the internal reliability was excellent (ω = 0.96; α = 0.96), very similar to the original study32, and higher than that of the original Arabic validation17 (α = 0.925), which means that the ASE scale is effective in assessing Academic Self-Efficacy in Arab speaking students just as well as other groups.

A significant finding of our study is that our translation of the ASE scale remained consistent across sexes and between countries. This means that both sexes and respondents from the different countries understand the scale items equally. Females scored higher than males on our ASE scale. This gender disparity in self-efficacy can be attributed to societal and cultural expectations that shape students’ perceptions of their abilities from a young age, and females are generally found to internalize academic successes more effectively, attributing them to their own abilities and efforts, which reinforces their self-efficacy33. Conversely, males are more likely to attribute successes to external factors, which might explain their lower academic self-efficacy in areas where they do not traditionally excel34. Additionally, females often receive more encouragement and support in academic settings, contributing to higher self-efficacy scores35. Furthermore, significant differences in ASE scores were observed among participants from various countries, which can be attributed to several socio-cultural and educational factors. Lebanese participants had the highest ASE scores, followed by Egyptian, Omani, Emirati, Kuwaiti, and Saudi participants. The significant variation, which highlighted specific significant differences between countries, suggest that cultural and educational contexts play a crucial role. Lebanese students might benefit from a cultural context that emphasizes individual achievement and confidence, potentially supported by a relatively liberal educational system that encourages self-efficacy. On the other hand, Saudi students, who scored the lowest, might be influenced by a more conservative cultural context where modesty is valued, potentially leading to lower self-reported self-efficacy. The significant differences between Saudi Arabia and other countries, including UAE, Egypt, Lebanon, Oman, and Kuwait, highlight how varying educational practices, societal norms, and support systems can impact students’ academic self-efficacy. These findings align with previous research indicating that cultural values such as collectivism, power distance, and response styles significantly influence self-efficacy scores36,37.

In order to prove the concurrent validity of the ASE scale, we compared the scores on that scale with psychological distress and social support measures. ASE scale scores correlated well with lower total psychological distress scores, as well as with depression and anxiety subscores. This can be explained by the fact that higher self-efficacy beliefs enhance an individual’s capacity to manage anxio-depressive symptoms and maintain mental well-being. Studies indicate that students with higher academic self-efficacy are better equipped to handle academic challenges, reducing the likelihood of experiencing significant psychological distress2. Additionally, self-efficacy fosters a sense of control and confidence in one’s abilities, which mitigates negative feelings associated with academic pressures38. This relationship is evident in various student populations, where higher self-efficacy is consistently linked to lower levels of psychological distress and better mental health outcomes39. Furthermore, interventions aimed at increasing self-efficacy have been shown to effectively reduce psychological distress and improve overall academic performance40.

In our findings, ASE scores correlated positively with all dimensions of perceived social support (i.e. family, friends and significant others). This suggests that students with higher perceived social support levels tend to be more academic self-efficacious and feel more confident in their abilities to manage academic tasks independently. Our findings are in line with those of previous research, suggesting that perceived social support positively influences academic self-efficacy41,42. For instance, a study showed that the more support received from friends and parents during early adolescence, the greater the self-efficacy level during late adolescence42. Indeed, reduced social support perceived by the student during the learning process may negatively impact their enthusiasm for learning43. Social support as subjectively perceived from different social networks may lower academic pressures and enhance coping abilities to current difficult situations44.

Clinical implications

Translating and validating the ASE scale into Arabic has significant clinical implications, particularly for enhancing the educational and psychological support provided to Arabic-speaking students. Firstly, a culturally adapted and validated scale ensures accurate measurement of self-efficacy, which is crucial for identifying students’ confidence in their academic abilities. This can help educators and clinicians to develop tailored interventions aimed at boosting students’ self-efficacy, potentially improving their academic performance and overall mental health. Furthermore, reliable self-efficacy measurements can aid in the early identification of students at risk of academic underachievement and psychological distress, enabling timely and targeted support interventions. By providing a valid tool for assessing academic self-efficacy in the Arabic context, researchers and practitioners can better understand the unique challenges faced by Arabic-speaking students, facilitating more effective educational strategies and mental health support programs.

Limitations

Our study, as with all research, carries several limitations. Firstly, cross-sectional design inherently captures data at a single point in time, which prevents the assessment of changes in self-efficacy over time and the potential long-term impact of educational interventions. This temporal limitation also restricts the ability to establish causality between variables. Secondly, the cultural diversity within the sample, although beneficial for generalizability, might introduce variability due to different educational systems, cultural norms, and socioeconomic factors across the countries involved, which can affect the consistency and reliability of the scale. Additionally, the convenience sampling method used in our study may lead to selection bias, as the sample might not be representative of the broader population of Arabic-speaking college students. These limitations suggest the necessity for longitudinal studies and further validation across diverse Arabic-speaking populations. Finally, as the recruitment was done online, only students who had internet connections were involved in this study. However, those having internet access may be related to factors and circumstances that shape their emotions, thoughts, behaviours and environment, such as socioeconomics, motivation to school, career aspirations, and parents’ attitudes towards education45.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study successfully translated and validated the ASE scale into Arabic, providing a reliable tool for assessing academic self-efficacy among multiple Arabic-speaking college students across multiple linguistically, culturally and socioeconomically diverse Arab countries. Our findings indicate that the Arabic version of the scale is valid, reliable and invariant across sexes and Arab nations, which broadens the scale’s applicability in the region. This scale can now be utilized to identify students’ academic confidence levels and to develop targeted interventions aimed at improving educational outcomes and mental health among Arabic-speaking university students. The validated Arabic ASE scale is a significant step forward in educational and psychological research within the Arab world, offering a robust tool for enhancing student support services. Future perspectives for this study include expanding the validation of the ASE scale across a broader range of Arabic-speaking countries to enhance its cross-cultural applicability. Further research could explore the specific cultural, educational, and socio-economic factors contributing to variations in ASE scores, providing deeper insights into the mechanisms driving self-efficacy in different contexts. Longitudinal studies could assess the stability of ASE over time and its impact on academic performance and career outcomes. Additionally, intervention studies aiming to enhance ASE through targeted educational programs could offer practical strategies for educators to support student success across diverse cultural settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants.

Author contributions

FFR, SO and SH designed the study; AH drafted the manuscript; SH carried out the analysis and interpreted the results; AA, MH, MR, SAR, RA, NF, REH, and JM collected the data. DM, RH, MB and SEK reviewed the paper for intellectual content; all authors reviewed the final manuscript and gave their consent.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due the restrictions from the ethics committee but are available upon a reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board in the faculty of pharmacy at Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan, with an approval number of 2023-PHA- 43. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects; the online submission of the soft copy was considered equivalent to receiving a written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Sahar Obeid, Souheil Hallit, and Feten Fekih-Romdhane.

Contributor Information

Rabih Hallit, Email: hallitrabih@hotmail.com.

Feten Fekih-Romdhane, Email: feten.fekih@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Pajares, F. Self-Efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Rev. Educ. Res.66, 543–578 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zajacova, A., Lynch, S. M. & Espenshade, T. J. Self-Efficacy, Stress, and Academic Success in College. Res. High. Educ.46, 677–706 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassidy, S. Resilience building in students: The role of academic self-efficacy. Front Psychol.6, 1781. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01781 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning. Educ. Psychol.28, 117–148 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morosanova, V. I., Fomina, T. G. & Bondarenko, I. N. Academic achievement: intelligence, regulatory, and cognitive predictors. Psychol. Russia8, 136–156 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, X., Zhong, J., Luo, M. & Lu, M. Academic self-efficacy, social support, and professional identity among preservice special education teachers in China. Front Psychol. 11, 374. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00374 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussain, A., Safdar, Q. & Khan, A. Relationship Of academic motivation & self-efficacy with academic grades of students: Social support as A mediator. Pakistan Journal of Social Research.5(02), 803–811 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zander, L., Brouwer, J., Jansen, E. P. W. A., Crayen, C. & Hannover, B. Academic self-efficacy, growth mindsets, and university students’ integration in academic and social support networks. Learn. Individ. Differ.62, 98–107 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol.25(1), 54–67 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wigfield, A. & Eccles, J. S. Expectancy-Value theory of achievement motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol.25(1), 68–81 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dweck, C. S. Motivational processes affecting learning. Am. Psychol.41(10), 1040 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Zyl, L. E., Klibert, J. J., Shankland, R., See-To, E. W. K. & Rothmann, S. The General Academic Self-Efficacy Scale: Psychometric properties, longitudinal invariance, and criterion validity. J. Psychoeduc. Assess.40, 777–789 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gresham, F. M., Evans, S. & Elliott, S. N. Academic and Social Self-Efficacy Scale: Development and Initial Validation. J. Psychoeduc. Assess.6, 125–138 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onyeizugbo, E. U. Self-Efficacy and test anxiety as correlates of academic performance. Educ. Res.1, 477–480 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chemers, M. M. Hu L-t, Garcia BF: Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. J. Educ. Psychol.93(1), 55 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohazie A, Mohammed F: Reliability and Validity of an Arabic Translation of Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (ASE) on Students at King Faisal University. In: 2018; (2018).

- 18.Almutairi, S., Heller, M. & Yen, D. Reclaiming the heterogeneity of the Arab states. Cross Cultural Strategic Manag.28(1), 158–176 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Widenfelt, B. M., Treffers, P. D., de Beurs, E., Siebelink, B. M & Koudijs E. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of assessment instruments used in psychological research with children and families. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev.8(2), 135–147. 10.1007/s10567-005-4752-1 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fenn, J., Tan, C.-S. & George, S. Development, validation and translation of psychological tests. BJPsych. Adv.26(5), 306–315 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambuehl, B. & Inauen, J. Contextualized measurement scale adaptation: a 4-Step tutorial for health psychology research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19(19), 12775 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melki, I., Beydoun, H., Khogali, M., Tamim, H. & Yunis, K. Household crowding index: a correlate of socioeconomic status and inter-pregnancy spacing in an urban setting. J. Epidemiol. Community Health58(6), 476–480 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali, A. M., Hori, H., Kim, Y. & Kunugi, H. The Depression anxiety stress scale 8-items expresses robust psychometric properties as an Ideal shorter version of the depression anxiety stress scale 21 among healthy respondents from three continents. Front. Psychol.13, 799769 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali, A. M. et al. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8: investigating its cutoff scores in relevance to loneliness and burnout among dementia family caregivers. Sci. Rep.14(1), 13075. 10.1038/s41598-024-60127-1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G. & Farley, G. K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess.52(1), 30–41 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fekih-Romdhane, F. et al. Psychometric properties of an Arabic translation of the multidimensional social support scale (MSPSS) in a community sample of adults. BMC Psychiatry.23(1), 432. 10.1186/s12888-023-04937-z (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mundfrom, D. J., Shaw, D. G. & Ke, T. L. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. Int. J. Test.5(2), 159–168 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lt, Hu. Bentler PM: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling6(1), 1–55 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Modeling14(3), 464–504 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vadenberg, R. & Lance, C. A review and synthesis of the measurement in variance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ Res Methods3, 4–70 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hair, J. F. Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M. & Gudergan, S. P. Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling (SaGe publications, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chemers, M. Hu L-t, Garcia B: Academic Self-Efficacy and First-Year College Student Performance and Adjustment. J. Educ. Psychol.93, 55–64 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoen, L. G. & Winocur, S. An investigation of the self-efficacy of male and female academics. J. Vocat. Behav.32, 307–320 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endawoke, Y. Gender differences in causal attributions for successes and failures, and academic self-efficacy among high school students. Ethiopian J. Educ.16, 50–74 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baji, M. I. Analysis of gender difference in academic self-efficacy and achievements among senior secondary school students in niger state Nigeria. People: Int. J. Soc. Sci.5, 659–675 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin, R., Wu, R., Xia, Y. & Zhao, M. What cultural values determine student self-efficacy? An empirical study for 42 countries and economies. Front Psychol.14, 1177415. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1177415 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vieluf, S., Kunter, M. & Vijver, F. J. R. Teacher self-efficacy in cross-national perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ.35, 92–103 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Honicke, T. & Broadbent, J. The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev.17, 63–84 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grøtan, K., Sund, E. R. & Bjerkeset, O. Mental Health, academic Self-Efficacy and study progress among college students - The shot study. Norway. Front. Psychol.10, 45 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bani, M., Zorzi, F., Corrias, D. & Strepparava, M. G. Reducing psychological distress and improving student well-being and academic self-efficacy: the effectiveness of a cognitive university counselling service for clinical and non-clinical situations. Br. J. Guid. Couns.50, 757–767 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen, X., Zhong, J., Luo, M. & Lu, M. Academic self-efficacy, social support, and professional identity among preservice special education teachers in China. Front. Psychol.11, 374 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adler-Constantinescu, C., Beşu, E.-C. & Negovan, V. Perceived social support and perceived self-efficacy during adolescence. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci.78, 275–279 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao, H. & Zhang, X. The influence of field teaching practice on pre-service teachers’ professional identity: A mixed methods study. Front. Psychol.8, 1264 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sippel, L. M., Pietrzak, R. H., Charney, D. S., Mayes, L. C., & Southwick, S. M. How does social support enhance resilience in the trauma-exposed individual? Ecol. Soc.20(4). http://www.jstor.org/stable/26270277 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Odacı, H., Kaya, F., Kınık, Ö. & Aydın, F. Assessing the satisfaction with school life among Turkish adolescents: Adapting the Academic Life Satisfaction Scale. Educ. Dev. Psychol.42(1), 94–104 (2025). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due the restrictions from the ethics committee but are available upon a reasonable request from the corresponding author.