Abstract

The diagnosis of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL), a dermatosis that provides the only known reservoir for the parasite Leishmania donovani in India, remains a problem. Timely recognition and treatment of PKDL would contribute significantly to the control of kala-azar. We evaluated here the potential of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as a diagnostic tool for PKDL. Antigen prepared from promastigotes and axenic amastigotes with parasite isolates that were derived from skin lesions of a PKDL patient gave sensitivities of 86.36 and 92%, respectively, in the 88 PKDL cases examined. The specificity of the ELISA test was examined by testing groups of patients with other skin disorders (leprosy and vitiligo) or coendemic infections (malaria and tuberculosis), as well as healthy controls from areas where this disease is endemic or is not endemic. A false-positive reaction was obtained in 14 of 144 (9.8%) of the controls with the promastigote antigen and in 14 of 145 (9.7%) of the controls with the amastigote antigen. Evaluation of the serodiagnostic potential of recombinant k39 by ELISA revealed a higher sensitivity (94.5%) and specificity (93.7%) compared to the other two antigens used. The data demonstrate that ELISA with crude or recombinant antigen k39 provides a relatively simple and less-invasive test for the reliable diagnosis of PKDL.

Individuals infected with the protozoan parasite Leishmania donovani present with the clinical disease visceral leishmaniasis (VL) or kala-azar (KA), which is fatal if left untreated. The annual incidence and prevalence levels of VL are 0.5 and 2.5million, respectively, of which 90% of cases occur in the Indian subcontinent and Sudan (3). Post-KA dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) is a dermatotropic form of disease caused by L. donovani that develops as a sequela in 10 to 20% of VL cases in India and in >50% of VL cases in Sudan (18, 30). PKDL is characterized by hypopigmented macules and erythematous eruptions leading to the formation of papules and nodules (13, 18). In India, PKDL occurs several months to as many as 35 years after KA is cured and is considered to be the main reservoir for transmission of the visceral disease in the absence of a zoonotic host (1, 27).

Definitive diagnosis of PKDL by demonstration of L. donovani parasites (LD bodies) in skin biopsies has a sensitivity of only 58% (23), since parasites are scanty in the lesions. The disease is therefore often misdiagnosed as leprosy, a coendemic disease that resembles PKDL both clinically and pathologically (17). Serodiagnosis has been used as an important alternative for the diagnosis of KA, although its value is often limited for specificity and reproducibility when crude parasite antigen is used (6, 12, 24, 25). The use of recombinant k39 (rk39) has been shown to overcome these limitations to a considerable extent (2, 16, 22, 26, 29). Antileishmanial antibodies of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM classes have been demonstrated in the sera from PKDL patients (8, 20); however, limited studies have been conducted to develop serological methods for the diagnosis of PKDL (9). Increased sensitivity has been reported when the immunoperoxidase technique and PCR are used (10, 15, 21). We evaluate here the utility of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in diagnosing PKDL with total antigen extract and rk39. Antigen extracts were prepared from indigenous parasites at two different developmental stages—promastigotes and amastigotes—isolated from PKDL lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture for sera from individuals in the following clinical categories.

PKDL.

A group of 88 patients from Bihar, where PKDL is endemic, and reporting to Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, India, over a period of 4 years were included in this category. PKDL was diagnosed clinically and confirmed by the demonstration of parasites in skin lesions or by histopathologic findings (18). All patients included in this category were found to respond to therapy with sodium antimony gluconate.

KA.

Thirty patients reporting to the Department of Medicine, Safdarjung Hospital, with fever and splenomegaly and parasitologically confirmed to have leishmania parasites in bone marrow aspirates were categorized as having KA.

Tuberculosis and malaria.

A total of 22 patients with confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis and another 19 with malaria (peripheral blood smear positive) were included in this group.

Leprosy and vitiligo.

This group included 30 patients confirmed to have lepromatous leprosy and 20 vitiligo patients (confirmed by histopathology) who reported to the Department of Dermatology, Safdarjung Hospital.

Healthy controls.

Healthy controls (n = 32) were subjects living in Delhi, India, an area where KA is not endemic.

Endemic controls.

“Endemic controls” (n = 22) were the first-degree healthy relatives of patients living in Muzaffarpur, Bihar, an area known for its KA endemicity.

Parasite cultures.

Parasites isolated from lesions of PKDL patients propagated as promastigotes in M199 supplemented with 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10% fetal calf serum as described earlier (19). Axenically grown amastigotes were cultured by the gradual adaptation of promastigotes to growth at pH 5.5 and 37°C in a 6 to 7% CO2 atmosphere as described by Joshi et al. (11).

Antigens.

rk39, prepared as described previously (4), was a kind gift from Steve Reed, Corixa Corp., Seattle, Wash. Promastigotes and amastigotes of L. donovani isolated from PKDL lesions as described above were harvested in late log phase and lysed in buffer containing 3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.0), and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The amount of protein in the lysate was estimated by using a DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad).

ELISA.

Serum samples were tested by ELISA according to a standard method described elsewhere (28). In brief, polystyrene 96-well microtiter plates (Corning, N.Y.) were coated overnight with 10 ng of rk39 or 200 ng of promastigote or amastigote antigen in 100 μl of 0.1 M bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.0). The plates were blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at 37°C, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-Tween 20, and incubated for 2 h with 100 μl of patient serum at various dilutions as specified. Wells were washed three times with the same buffer and incubated with 100 μl of goat anti-human IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 2 h. This step was followed by three rinses with PBS-Tween 20 and the addition of ortho-phenylenediamine substrate with hydrogen peroxide. The optical density (OD) of each well was measured at 492 nm in an ELISA reader (Titertek Multiskan Plus). Each sample was assayed in triplicate or more, along with appropriate controls. The ELISA reader was set to subtract the reading of a blank control from the test samples. The cutoff value was derived on the basis of the mean absorbance obtained with normal human sera from an area of endemicity with the three antigens. The cutoff value (i.e., 0.45) was twice that of the mean absorbance obtained. The statistical significance of the results of the study was compared by using the unpaired Student's t test, and P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

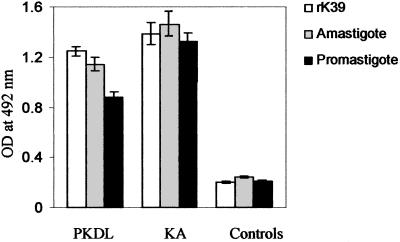

A total of 263 serum samples were collected and tested by ELISA using three different antigens: the promastigote antigen, the amastigote antigen, and the rk39 antigen. Initially, we compared results with antigen derived from promastigotes of reference strain AG83 (MHOM/IN/83/AG83) and those derived from dermal lesions and found that the latter gave higher absorbance values upon ELISA with PKDL sera (data not shown). Subsequently, the promastigotes and amastigotes used for antigen preparation were those cultured from parasites isolated from PKDL lesions. The test samples included 88 PKDL patients and 146 controls, along with 30 KA patients to serve as positive control samples. In PKDL samples, the mean OD was highest with rk39 antigen, even though the serum dilution was double (1:200) compared to that used for amastigote and promastigote antigens (1:100; Fig. 1). The titer for PKDL cases was up to 10−5 with rk39 (data not shown). The controls, on the other hand, gave lowest mean OD with rk39 antigen, making it the most suitable antigen to use as a diagnostic agent. The amastigote antigen gave a significantly higher mean OD (P < 0.05) compared to the promastigote antigen in PKDL patients, but the OD was not significantly different in the control group. In general, KA samples gave higher OD values than the PKDL samples with all three antigens, but the difference in the mean OD was statistically significant (P < 0.05) only with the crude antigens and not with the rk39 antigen.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of ELISA with rk39 antigen and antigens derived from promastigotes and amastigotes of L. donovani isolated from the dermal lesions of a PKDL patient. Sera were used in a 1:200 dilution with rk39 and a 1:100 dilution for promastigote and amastigote antigens in all of the samples. The mean OD values at 492 nm as determined by ELISA for patient and control sera were plotted.

As seen in Table 1 the ELISA sensitivities for the detection of PKDL cases were 84 of 88 (94.5%), 81 of 88 (92%), and 76 of 88 (86.36%), respectively, for the rk39, amastigote, and promastigote antigens. Among the controls, the use of rk39 led to a correct diagnosis in 135 of 144 (93.7%) cases. The use of amastigote and promastigote antigens gave correct diagnoses in 131 of 145 (90.3%) and 130 of 144 (90.2%) of the control samples. The estimated sensitivity of the ELISA test at a 95% confidence interval ranged from 98.7 to 92.5% for the rk39 antigen and from 96.1 to 88% and from 91.3 to 83.7% for the amastigote and promastigote antigens, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the results of ELISA for the three serological assays—performed with the rk39 antigen, the amastigote antigen, and the promastigote antigen—used to diagnose PKDL in Indian patientsa

| Group | ELISA result (no. of sera) with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rk39 Ag

|

Amastigote Ag

|

Promastigote Ag

|

||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |

| PKDL | 84 | 4 | 81 | 7 | 76 | 12 |

| KA | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| Leprosy | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 |

| Vitiligo | 0 | 20 | 1 | 19 | 1 | 19 |

| Tuberculosis | 3 | 19 | 4 | 18 | 4 | 18 |

| Malaria | 1 | 18 | 2 | 17 | 2 | 17 |

| Healthy control | 1 | 31 | 3 | 29 | 3 | 29 |

| Endemic control | 4 | 17 | 4 | 18 | 4 | 17 |

An OD of 0.45 was used as a cutoff value in all cases. Ag, antigen.

Analysis of the mean OD as a function of a history of KA was made among PKDL patients. The mean OD was found to be independent of a history of KA (Table 2). A majority (62 of 88) of the PKDL patients had recovered from KA more than 5 years previously, whereas 9 of 88 were not aware of any history of KA.

TABLE 2.

ELISA values obtained with the three antigens in 88 PKDL cases grouped according to KA historya

| Group | KA history (yr) | No. of cases | ELISA result (Mean OD ± SD) with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rk39 Ag | Amastigote Ag | Promastigote Ag | |||

| 1 | <5 | 17 | 1.306 ± 0.217 | 1.19 ± 0.38 | 1.057 ± 0.469 |

| 2 | 5-10 | 43 | 1.087 ± 0.424 | 1.036 ± 0.435 | 0.805 ± 0.392 |

| 3 | 10-15 | 19 | 1.27 ± 0.40 | 1.29 ± 0.524 | 0.836 ± 0.33 |

| 4 | -b | 9 | 1.31 ± 0.324 | 1.061 ± 0.489 | 0.977 ± 0.377 |

Ag, antigen.

-, no history of KA.

DISCUSSION

In India, PKDL occurs in 10 to 20% of KA cases months to as many as 35 years after patients are cured of KA. This is quite different from the situation with PKDL in Sudan, since PKDL occurs in >50% of cured KA cases usually weeks or months after recovery from the visceral disease (30). Diagnosis of PKDL is a problem since it is often confused with other dermatological conditions such as leprosy. It is important to identify and treat PKDL patients, since they constitute the only known reservoir for L. donovani in India (27). We recently described a sensitive and species-specific PCR assay for the diagnosis of PKDL (21); however, PCR is expensive and requires sophisticated facilities and trained personnel. Each of the ELISA tests described in the present study, although not as sensitive or as specific as a PCR assay, would provide a more economical and practical assay for the diagnosis of PKDL.

The serodiagnostic potential of rk39 for VL has been shown with subjects from various parts of the world, including the Indian subcontinent, Brazil, and Sudan, establishing conservation of the k39 epitope among visceralizing species of Leishmania (2, 16, 22, 29). In a study with a limited number of PKDL patients in Sudan, an rk39 ELISA was found to be sensitive and specific as a diagnostic test (29). In the present study we used a large number of serum samples to demonstrate that PKDL patients in India have high titers of anti-k39 IgG and that ELISA with rk39 antigen provides a highly sensitive (95.45%) and specific (93.5%) tool for diagnosing PKDL.

Several studies have shown serological tests to be useful in the diagnosis of KA; however, methods for the diagnosis of KA often lack sensitivity for the diagnosis of PKDL. In order to improve the sensitivity of the ELISA, we used promastigote antigen prepared with parasite isolates from dermal lesions of a PKDL patient. The indigenous PKDL antigen was found to give generally higher titers than those obtained with the reference strain (AG83), which is similar to the observation made during a direct agglutination test for PKDL in Sudan (9). Since Leishmania parasites are present in the amastigote form in the human host, the humoral immune response would be directed against antigens of the amastigote form. Antigen prepared from amastigotes has indeed been shown to be superior to the promastigote-derived antigen (25); however, amastigotes are generally difficult to isolate in large quantity and in pure form. To overcome this problem, we set up an axenic amastigote culture from parasites isolated from dermal lesions and used it for antigen preparation. The amastigote antigen was found to give significantly higher absorbance values and better sensitivity compared to the promastigote antigen, although the specificity was similar in both the cases. Hence, the amastigote antigen is recommended for use when recombinant K39 is not available or affordable. Use of crude antigen is known to lead to false-positive results with samples of other diseases due to certain common antigenic epitopes. Sera from patients suffering from other common skin disorders in India, namely, leprosy and vitiligo, have been examined, since PKDL is most frequently misdiagnosed as one of these. Among this group use of the promastigote and amastigote antigens gave false-positive results in only 1 of 50 cases. False-positive results were more frequent in patients with malaria (2 of 19) and tuberculosis (4 of 22). The overall specificity of detection was ca. 90% with either promastigote or amastigote antigens.

The causative organism in PKDL has been characterized as L. donovani by methods such as isoenzyme typing (5), reaction with monoclonal antibodies (P. Salotra et al., unpublished data), and species-specific PCR (21). It has also been demonstrated that there are indeed molecular differences between PKDL isolates and KA isolates of L. donovani (7). Gene expression in the parasite is also expected to be different in PKDL since not only the site of infection but also the host humoral immune response is distinct compared to KA (20). The antibody titer to leishmanial antigens is known to be much lower in PKDL patients than in KA patients (8). We observed here high anti-k39 titers of up to 10−5 in PKDL patients in a large number of serum samples, indicating that k39 is abundantly expressed in parasites causing PKDL.

Antileishmanial antibody titers measured by direct agglutination test have been reported to remain positive for up to 5 years after recovery in >50% of VL patients examined (14). In our study only 17 of 88 (19.3%) patients had a history of KA of <5 years. The remaining 80.7% had either no history of KA or a history of KA exceeding 5 years for periods of even up to 15 years. Therefore, it would be reasonable to conclude that the antibodies detected in ELISA were largely due to PKDL and not those persisting due to a history of KA.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Steve Reed for providing rk39 antigen. Rabbit anti-human IgG-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were a kind gift from J. K. Batra, National Institute of Immunology, New Delhi, India. The technical assistance of P. D. Sharma is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addy, M., and A. Nandy. 1992. Ten years of Kala-azar in west Bengal, Part 1: did PKDL initiate the outbreak in 24 parganas? Bull. W. H. O. 70:341-346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badaro, R., D. Benson, M. C. Eulalio, M. Freire, S. Cumba, E. M. Netto, D. P. Sampaio, C. Madureira, J. M. Burns, R. L. David, and S. G. Reed. 1996. rk39: a cloned antigen of Leishmania chagasi that predicts active visceral leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 173:758-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bora, D. 1999. Epidemiology of visceral leishmania in India. Natl. Med. J. India 12:62-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns, J. M., Jr., W. G. Shreffler, D. R. Benson, H. W. Ghalib, R. Badaro, and S. G. Reed. 1993. Molecular characterization of a kinesin-related antigen of Leishmania chagasi that detects specific antibody in African and American visceral leishmaniasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:775-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee, M., M. Manna, A. N. Bhaduri, and D. Sarkar. 1995. Recent kala-azar cases in India: isoenzyme profiles of Leishmania parasites. Ind. J. Med. Res. 106:165-172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudary, A., P. Y. Guru, A. Tandon, and K. C. Saxena. 1994. Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of Kala-azar in Bhadohi (Varanasi), India. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 84:363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasgupta, S., D. K. Ghosh, and H. K. Majumder. 1991. A cloned kinetoplast DNA minicircle fragment from a Leishmania sp. specific for PKDL strains. Parasitology 102:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haldar, J. P., K. C. Saha, and A. C. Ghose. 1981. Serological profiles in India post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 75:514-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harith, A. E., S. Chowdary, A. Al-Masum, S. S. Santos, P. K. Das, S. Akhter, J. C. M. Vetter, and I. Haq. 1996. Reactivity of various leishmanial antigens in a direct agglutination test and their value in differentiating post-kala azar dermal leishmaniasis from leprosy and other skin conditions. J. Med. Microbiol. 44:141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ismail, A., A. Kharazmi, A. Permin, and A. M. El Hassan. 1997. Detection and characterization of Leishmania in tissues of patients with post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis using specific monoclonal antibody. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91:283-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi, M., D. M. Dwyer, and H. L. Nakhasi. 1993. Cloning and characterization of differentially expressed genes from in vitro grown amastigotes of Leishmania donovani. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 58:345-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kar, K. 1995. Serodiagnosis of leishmaniasis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 21:123-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukherjee, A., V. Ramesh, and R. S. Misra. 1993. Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: a light and electron microscopic study of 18 cases. J. Cut. Pathol. 20:120-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odera, O., E. A. A. Wamachi, J. M. Kagai, J. A. L. Kurtzhals, J. I. Githure, A. S. Hey, J. B. O. Were, D. K. Koech, E. S. Mitema, and A. Kharazmi. 1993. Field application of an ELISA using redefined Leishmania antigens in the detection of visceral leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 87:423-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osman, O. F., L. Oskam, N. C. Kroon, G. J. Schoone, E. T. A. G. Khalili, A. M. El-Hassan, E. E. Zijlstra, and P. A. Kager. 1998. Use of PCR for diagnosis of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1621-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu, J. Q., L. Ahong, M. M. Yasinzai, M. Ras, H. S. Z. Iaksu, S. G. Reed, K. P. Chang, and A. G. Sachs. 1994. serodiagnosis of Asian leishmaniasis with recombinant antigen from repetitive domain of a leishmania kinesin. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 88:543-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramesh, V. 1994. On the difference between Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis and leprosy. Trop. Doc. 24:120-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramesh, V., and A. Mukherjee. 1995. Post Kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Int. J. Dermatol. 34:85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salotra, P., R. Ralhan, and R. Bhatnagar. 1994. Differential expression of stress proteins in virulent and attenuated promastigotes of Leishmania donovani. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 33:691-697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salotra, P., A. Raina, and V. Ramesh. 1999. Western blot analysis of humoral immune response to Leishmania donovani antigens in patients with post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:98-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salotra, P., G. Sreenivas, G. P. Pogue, N. Lee, H. Nakhasi, V. Ramesh, and N. S. Negi. 2001. Development of a species-specific PCR assay for detection of Leishmania donovani in clinical samples of kala-azar and post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:849-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh, S. A., G. Sachs, K. P. Chang, and S. G. Reed. 1995. Diagnostic and prognostic value of k39 recombinant antigen in Indian leishmaniasis. J. Parasitol. 81:1000-1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh, R. P. 1968. Observation on dermal leishmanoid in Bihar. Ind. J. Dermatol. 13:59-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singla. N., G. S. Singh, S. Sundar, and V. K. Vinayak. 1993. Evaluation of the direct agglutination test as an immunodiagnostic tool for Kala-azar in India. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 87:276-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha. R., and S. Sehgal. 1994. Comparative evaluation of serological tests in Indian Kala-azar. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97:333-340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundar, S., S. G. Reed, V. P. Singh, P. C. K. Kumar, and H. W. Murray. 1998. Rapid accurate field diagnosis of Indian visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet 351:563-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thakur, C. P., and K. Kumar. 1992. Post Kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: a neglected aspect of kala-azar control programmes. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 86:355-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voller, A., A. Bartlett, and D. E. Bidwell. 1978. Enzyme immunoassay with special reference to ELISA techniques. J. Clin. Pathol. 31:507-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zijlstra, E. E., N. S. Daifalla, P. A. Kager, E. A. G. Khalil, A. M. El-Hassan, S. G. Reed, and H. W. Ghalib. 1998. rk39 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of Leishmania donovani infection. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:717-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zijlstra, E. E., E. A. G. Khalil, P. A. Kager, and A. M. El Hassan. 2000. Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in the Sudan: clinical presentation and differential diagnosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 143:136-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]