Abstract

Immunotherapy employing natural killer (NK) cells has emerged as a transformative approach to treating hematological malignancies. The reprogramming of NK cells by incorporating a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) equipped with potent signaling domains has demonstrated efficacy in enhancing NK cell responses and improving specificity in recognizing cancerous cells. Despite these advancements, the primary challenge in implementing allogeneic NK cell therapy requiring a viable donor source for clinically relevant doses remains unresolved. This study tested NK cells obtained from leukoreduction filters (LRF) post-blood donation to address the need for an efficient and scalable supply of NK cells for generating anti-BCMA CAR NK cells. LRF-NK cells were isolated under sterile conditions and compared with peripheral blood (PB)-derived NK cells in terms of immunophenotype, proliferation capacity, and functional characteristics. Notably, no significant differences in inherent characteristics were observed between LRF-NK and PB-NK cells. Subsequently, both NK cell populations were employed to generate anti-BCMA CAR-NK cells. The data revealed a high specific cytotoxicity of Anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK cells during co-culture with U266-B1 cells (70.3 ± 4.78%), surpassing that observed with CCRF-CEM cells (31.3 ± 2.35%) and similar to Anti-BCMA CAR PB-NK cells. Furthermore, the expression of IFN-γ and Granzyme B, following the co-culture of Anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK cells with target cells, mirrored that observed in Anti-BCMA CAR PB-NK cells. This study provides the rationale and feasibility of utilizing LRF-NK cells as a safe, high-yield, accessible, and optimal cost-effective source for cancer immunotherapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-97584-1.

Keywords: Natural killer (NK) cell, Leukoreduction filters (LRF), Healthy donor, Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Cancer, Cell biology, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Immunology, Oncology, Cancer

Introduction

Cell-based immunotherapy represents a pivotal strategy for eliminating tumor cells by enhancing the patient’s immune system1,2. A promising avenue involves the modification of immune cells, particularly T cells and, more recently, natural killer (NK) cells, to intensify their recognition and clearance of target cells1,3,4.

In addition to progress across various domains of immunotherapy, such as Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) therapy, immune checkpoint blockers, and small molecule-based immunomodulators, the emergence of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) cells stands as a revolutionary stride in cancer treatment in the last decade. This advancement positions CAR cells at the forefront, poised to become a potent immunotherapeutic tool, particularly for hematologic malignancies2,5–8. The CAR construct comprises the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) domain, recognizing tumor-associated antigens (TAA) alongside transmembrane and intracellular domains that robustly activate cells for cytotoxic responses9,10.

Despite the initial success of CAR-T cell therapy, its widespread application is hampered by various side effects, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurotoxicity, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), on-target/off-tumor effects, tumor escape, and challenges of individualized preparation and high costs4,11,12. In light of these considerations, NK cells emerge as superior drivers of CARs compared to T cells in terms of safety, feasibility, and tolerability, as evidenced by diverse clinical trials13. In addition to their ability to eliminate cancer cells through TAA recognition with scFv domains, CAR-NK cells exhibit cytotoxic effects through the diversity of activating receptors, such as natural cytotoxicity receptors. They also mediate antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) via FcγRIII. Furthermore, CAR-NK cells demonstrate efficacy in eliminating residual malignant cells that may have altered phenotypes during ongoing treatment, a challenge not effectively addressed by CAR-T cells14,15. In contrast to CAR T cells, the capacity of CAR-NK cells to infiltrate tumor tissues positions them as promising therapeutic options for the treatment of solid tumors16.

The diminished risk of alloreactivity and subsequent GVHD, even with allogeneic NK cells, renders CAR NK cells potentially accessible from diverse sources, including umbilical cord blood (UCB), bone marrow, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and the NK-92 cell line. However, certain restrictions and challenges are associated with these sources, limiting the scope of NK cell-based immunotherapy14,17,18.

Leukoreduction filters (LRFs) have emerged as an alternative source of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Routinely employed to selectively remove white blood cells (WBCs) from donated whole blood samples to mitigate adverse transfusion reactions, these filters trap PBMCs, typically discarded, for potential reutilization. Studies have indicated that lymphocytes and monocyte-derived dendritic cells isolated from LRFs exhibit activity and biological function comparable to those derived from peripheral blood19–21.

Despite the increasing availability of effective treatments for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM), relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) remains inevitable in the majority of patients22. The B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) emerges as a potential candidate for CAR cell therapy, with its selectively induced expression during plasma cell differentiation essential for prolonged survival without perturbing normal B-cell homeostasis23. Consequently, the heightened expression of BCMA on MM-derived plasma cells, relative to normal cells, positions it as a favorable therapeutic TAA23–25.

In this context, our objective was to isolate NK cells from LRFs and peripheral blood, conducting a comparative analysis of their phenotype and functionality. Subsequently, these NK cells were employed to generate anti-BCMA CAR-NK cells, and their functional and cytotoxic effects were compared.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human BCMA+ multiple myeloma cell line (U266-B1), BCMA- acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line (CCRF-CEM), human erythroleukemic cell line (K562), and human embryonic kidney cell line (HEK293T) were procured from the Pasteur Institute (Tehran, Iran). The mentioned cell lines, isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), natural killer (NK).

cells, and the subsequently generated chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-NK cells were cultured in RPMI1640 (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Biosera, France) in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. DMEM media was employed for the culture of the HEK293T cell line.

NK cell isolation from peripheral blood (PB-NK) and leukoreduction filters (LRF-NK)

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were extracted from 30 mL of peripheral blood containing EDTA obtained from healthy donors through Ficoll gradient centrifugation following Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) elimination. Subsequently, the isolated PBMCs underwent a 2-hour culture period to eliminate monocytes. The resultant peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were harvested and utilized for NK cell isolation using a human NK cell isolation kit (Mojo sort TM, Biolegend, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The untouched NK cells were collected through a negative magnetic cell separator (MACS) LD column after incubation with a cocktail of biotin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies, including anti-CD14, CD15, CD3, CD4, CD279, CD19, CD36, CD123, and CD235 antibodies.

For the isolation of LRF-NK cells, Leukoflex LCR-5 filters (Macopharma, France) were obtained from the Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization (IBTO, Tehran, Iran). Each LRF is designed to separate leukocytes from 450 ± 50 mL of donated whole blood. The leukocytes trapped in the LRFs were collected using the standard back-flushing method. Subsequently, NK cells were purified using the human NK cell isolation kit (Mojo sort TM, Biolegend, USA). Following isolation, both PB-NK and LRF-NK cells, characterized by high purity, were cultured in 400 IU/mL hIL-2 (Miltenyi Biotec, USA) for subsequent experiments.

Purity and immunophenotype assessment of LRF-NK and PB-NK cells

For the assessment of the purity and immunophenotype of isolated LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, we conducted surface staining using 5 µL FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 (Abnova, Taiwan), 5 µL APC-conjugated anti-CD16 (Biolegend, USA), and 5 µL PE-conjugated anti-CD56 (Abnova, Taiwan) antibodies. Data acquisition was carried out using flow cytometry, utilizing a flow cytometer (Partec, CyFlow® MLS, Germany).

NK cell proliferation assay

LRF-NK and PB-NK cells were subjected to staining with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) cell division tracker kit (Biolegend, USA) and subsequently cultured in complete media supplemented with 400 IU/mL hIL-2 to evaluate their proliferative capacity. In this assay, cells were incubated with CFSE dye at 5 mM at 37 °C for 15 min in darkness. Proliferation dynamics were monitored at two-day intervals up to day 14 post-isolation, employing the flow cytometry method. Negative and positive controls were delineated by untreated and PHA-treated NK cells (Phytohemagglutinin, PHA, Sigma, USA), respectively.

NK cell cytotoxicity assay

For the comparison of cytotoxic effects, LRF-NK and PB-NK cells were cultured separately with a consistent number of target cells (5 × 104 cells), which were pre-stained with CFSE. The stained K562, CCRF-CEM, and U266-B1 cell lines, serving as target cells, were incubated with effector cells at a 10:1 ratio for 4 hours. Subsequently, cells were harvested and stained with a PE Annexin V apoptosis detection kit and 7-AAD (Biolegend, USA). Assay controls were employed to define the target cell populations, including spontaneous lysis in an independent culture and maximum lysis achieved by adding 100 µL of 100% ethanol (Merck, Germany). The percentage lysis of target cells was calculated as [(percent experimental lysis - percent spontaneous lysis)/ (percent maximum lysis - percent spontaneous lysis)] × 100.

In-silico process and generation of anti-BCMA CAR-NK cells

The anti-BCMA CAR construct was meticulously designed, and the CAR-NK cell construct was generated as described in previously established protocols26. In brief, the second generation of the construct was designed containing sequences including the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) domain against BCMA, CD8α as the hinge domain, CD28 as the transmembrane and co-stimulatory domain, and CD3ζ as the stimulatory domain, utilizing the SnapGene software (Northwestern University, USA). Subsequently, the stability, solubility, specificity, and surface expression of the construct were predicted using in-silico methods, including mfold, I-TASSER, Galaxy Refine, ERRAT, Expasy’s ProtParam, SOLpro, HDock, Ellipro, and PyMOL servers, as previously described26.

The complete CAR construct was then cloned into the pCDH vector containing GFP and puromycin resistance genes, utilizing SnabI and BstbI restriction enzymes. Lentiviruses were generated following transfection of HEK293T cells with the transgenic plasmid (pCDH-CAR) and helper plasmids, including psPAX (Packaging) and pMD2G (Envelope) plasmids. Lentiviral titer was determined by detecting GFP+ cells using flow cytometry. Subsequently, LRF-NK and PB-NK cells were successfully transduced with the lentiviral vectors at a MOI = 10 in the presence of 8 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) through a spinoculation process. The resulting CAR LRF-NK and CAR PB-NK cells were cultured in 400 IU/mL hrIL-2 and subjected to a comparative analysis concerning DNA integration, CAR expression, functionality, and cytotoxicity effects.

Lentiviral DNA integration in genomic DNA

Initially, the expression of GFP by transduced NK cells was confirmed through fluorescence microscopy 48 h post-transduction. Subsequently, lentiviral DNA integration was assessed utilizing the PCR method following genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction, performed using the Qiamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) and PCR product was checked using DNA gel electrophpresis method (InGenius3 gel documentation, Syngene, UK). Primers were specifically designed for the BCMA-specific scFv(Forward: TGGAGGATCATTGAGACTGT/Reverse: CGGATGAGGAAATGTAGGAC)and CD3ζ(Forward: CCAGAACCAGCTCTATAAC/ Reverse: CCTCCGCCATCTTATCTTTC), located at the beginning and the end of the CAR construct, respectively.

Identification of CAR expression on engineered LRF- and PB CAR-NK cells

To determine the surface expression of the anti-BCMA CAR on transduced LRF and PB-NK cells, we conducted labeling using 5 µL PE-conjugated F(ab’)2 anti-human IgG (Abcam, USA) and 5 µL PE-conjugated anti-CD8 antibody (Dako, Denmark) on days 3, 6, and 10 post-transductions. Subsequently, flow cytometer acquisition was performed. To confirm the lack of scFv and CD8 expression before CAR transduction, LRF-NK, and PB-NK cells were subjected to analysis.

CD107a assay

On day 3 post-transduction, LRF-CAR NK and PB-CAR NK cells were individually co-cultured with K562, U266-B1, and CCRF-CEM cell lines at a 10:1 (T: E ratio), maintaining cell-cell contact. The cells were incubated for 1 h at 37˚C in 5% CO2. Brefeldin A solution (Biolegend, USA) was then added to a final 5 mg/mL concentration and incubated for 3 h at 37 ˚C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, the expression of CD107a, serving as a marker of cell degranulation in the cytotoxicity process, was assessed using a 5 µL PE-conjugated anti-CD107a antibody (Biolegend, USA) through flow cytometry. CD107a expression was measured in GFP+-gated NK cells.

CD69 assessment as an early activation marker of NK cells

To evaluate the CD69 expression as the CAR NK-cell activity marker, on day 3 post-transduction, anti-BCMA CAR LRF/PB NK-cells were co-cultured with BCMA+/− cell lines (5 × 104) in a ratio of 10:1(T: E ratio) for 4 h. Next, CD69 expression was measured in GFP-gated CAR NK-cells using 5 µl APC conjugated anti-human CD69 antibody (Dako, Denmark) with flow cytometry method.

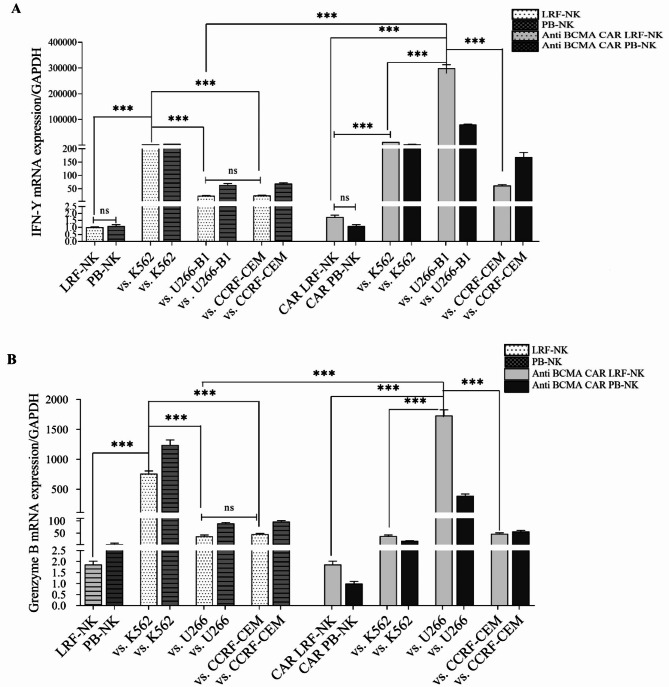

The mRNA expression of IFN-γ and granzyme B by NK cells and CAR-NK cells

The mRNA expression levels of IFN-γ and Granzyme B (GrB) in LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, as well as their respective anti-BCMA CAR NK cells, in response to BCMA+/− target cells were assessed through quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‑PCR). Both CAR NK cells were co-cultured with target cells, maintaining a constant number of target cells (5 × 104) at a 10:1 ratio for 4 hours. Subsequently, cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted using RNX plus (CinnaGen, Iran). DNase treatment (Fermentas, Canada) was applied, and cDNA was synthesized using a cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, Canada) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

The qRT‑PCR was conducted on the Rotor-Gene Q Series (Qiagen, Germany). In brief, 2 µL of cDNA was amplified in a total volume of 20 µL containing 10 µL of 2X SYBR Green Master Mix (Fermentas, Canada), 7.4 µL DEPC-treated water (CinnaGen, Iran), and 0.3 µL of each 10 pmol/µL forward and reverse primers (CinnaGen, Iran). Thermal cycling was initiated with denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing, and extension at 55 °C for 40 s. All data were normalized to the GAPDH housekeeping gene, and the gene mRNA expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

The sequences of specific primers for qRT‑PCR were as follows: IFN-γ (Forward: GCAGGTCATTCAGATGTAGCG / Reverse: GGCAGGACAACCATTACTGG), Granzyme B (Forward: GAAACGCTACTAACTACAGG / Reverse: GGCAGGACAACCATTACTGG), GAPDH(Forward: TGAGCAAGAGAGGCCCTATC/Reverse: AGGCCCCTCCTGTTATTATG).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SD of three replicates for three different donors from independent experiments. The normal distribution was ascertained by the Kolmogorov – Smirnow test. Significance levels were determined by Student’s t-test and One-Way ANOVA test. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism.

Ethics declarations

All methods were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study received approval from the institutional ethics committee (Ethic code: IR.TMI.REC.1398.009) of the High Institute for Education and Research in Transfusion Medicine. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Comparative analysis of phenotypic similarities in High-Count isolated cells from LRF-NK and PB-NK

In the study, the mean ± standard deviation of isolated leukocytes per filter using the back-flushing method was 8.1 × 108 ± 0.97 × 108 cells. Following platelet depletion and Ficoll-density gradient, the mean percentage of isolated PBMCs per filter was 73.0 ± 3.4, reaching 92.0 ± 2 after monocyte depletion, referred to as PBL. NK cells were enriched by MACS to a mean level of 8.5 × 107 ± 0.57 × 107 cells per filter. In comparison, PB-NK cells were purified to a mean level of 8.1 × 106 ± 0.35 × 106 cells per 30 mL.

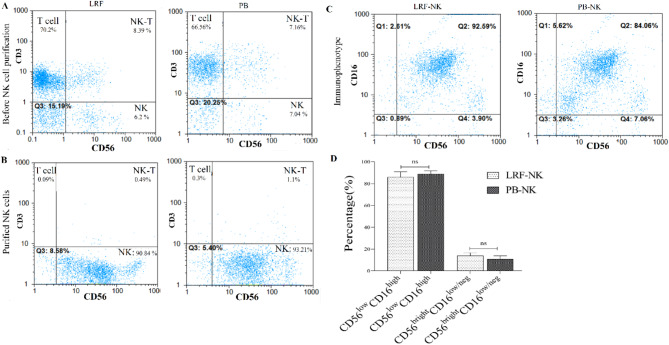

The mean percentage of the CD3+ cell population in PBLs isolated from LRFs was 70 ± 3.4, with no significant differences compared to those isolated from PB 67.0 ± 8.7 (P = 0.6) (Fig. 1A). The mean purity percentage of LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, characterized by a CD3− CD56+ phenotype, was 93.5 ± 1.8 and 92.0 ± 2.2, respectively, following MACS columns cell separation. This was observed considering a frequency of < 1% CD3+ cells population, as illustrated in Fig. 1B.

Fig. 1.

The purity and phenotype of LRF-NK and PB-NK cells. (A) Pre-MACS NK cell isolation: phenotypic analysis of anti-CD3 and anti-CD56-labeled isolated lymphocytes from LRF and PB. (B) Post-MACS separation: Purified LRF-NK and PB-NK cells characterized based on CD56 expression and the absence of CD3 expression. (C) CD16 and CD56 phenotypic expression on LRF-NK and PB-NK cells post-MACS separation. (D) Statistical comparison reveals no significant differences in the immunophenotype of NK cells from LRF-NK and PB-NK, considering populations with CD56dimCD16bright and CD56brightCD16dim/neg phenotypes (P = 0.14 and P = 0.32, respectively). LRF: leukocyte reduction Filter, PB: peripheral blood.

Two distinct NK cell subsets were evident in the LRF-NK and PB-NK cell sources, delineated by the expression pattern of CD56 and CD16 markers, as depicted in Fig. 1B. These subsets included a predominant population exhibiting a CD56dim CD16 bright phenotype, with mean percentage levels of 86.0 ± 3.2 and 89.0 ± 2.8 in LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, respectively. Furthermore, a smaller subset characterized by a CD56 bright CD16 dim/neg phenotype was identified, with mean percentage levels of 14.0 ± 4.0 and 10.5 ± 2.6 in LRF-NK and PB-NK cell sources, respectively(Fig. 1C). There were no significant differences (P > 0.05) in the distribution of these two distinct NK cell subsets between the two groups of cell sources, Fig. 1D.

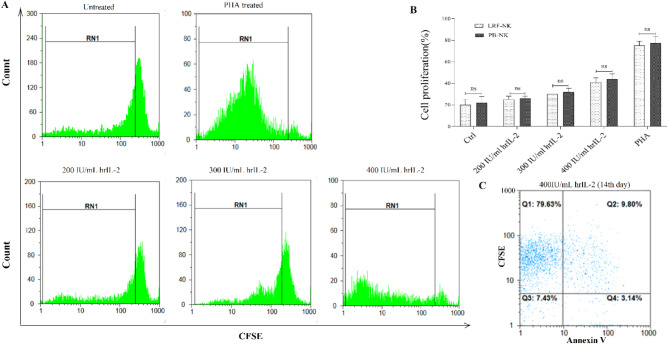

LRF-NK cells demonstrate comparable proliferation capacity to PB-NK cells

In evaluating proliferation, we treated both LRF-NK cells and PB-NK cells with hrIL-2 and subsequently assessed the expression of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) on day 14 post-culture. In Fig. 2A, the mean ± standard deviation of LRF-NK cell proliferation rates following treatment with 200, 300, and 400 IU/mL of hrIL-2 and phytohemagglutinin (PHA) were 25.0 ± 3.0%(undergoing up to two fold changes), 30.0 ± 2.9%(undergoing up to three fold changes), 41.0 ± 3.9%(undergoing up to four fold changes), and 75.0 ± 4.1%, respectively. Similarly, PB-NK cells exhibited proliferation rates of 26.0 ± 1.9%, 32.0 ± 3.3%, 44.0 ± 4.7%, and 77.0 ± 6.6% under the same conditions.

Fig. 2.

Proliferation and Viability Comparison of LRF and PB-NK Cells. (A) The dose-dependent proliferation of LRF-NK cells with 200, 300, and 400 IU/mL hrIL-2 treatment on day 14 was detected by CFSE staining. Untreated and PHA-treated LRF-NK cells served as negative and positive controls, respectively. LRF-NK cells, undergoing up to two, three and four division cycles following induction with 200, 300 and 400 IU doses of IL-2 respectively. (B) Statistical analysis reveals no significant differences in proliferation capacity between LRF-NK and PB-NK cells treated with different hrIL-2 concentrations. (C) The LRF-NK cell viability following treatment with 400 IU/mL IL-2 was detected using the annexin V on day 14. Data presented as mean ± SD. ** Represents P < 0.001 and *** P < 0.0001 (N = 3). LRF: Leukocyte reduction filter, PB: peripheral blood, PHA: phytohemagglutinin, CFSE: carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester.

Untreated LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, representing the negative control group, displayed proliferation capacities of 20.0 ± 4.9% and 22.0 ± 5.6%, respectively. Statistical analysis indicated no significant difference in proliferation between LRF-NK and PB-NK cells for each treatment condition (P = 0.99), as illustrated in Fig. 2B. Additionally, the viability of LRF-NK cells, after treatment with 400 IU/mL of hrIL-2, assessed by annexin V on day 14 post-isolation, was determined to be 88.0 ± 2.3%, as depicted in Fig. 2C.

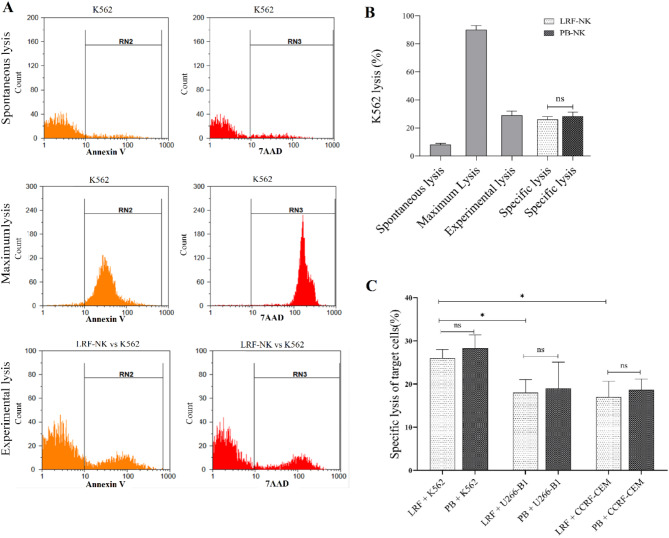

A comparable cytotoxic effect observed in LRF-NK and PB-NK cells

In Fig. 3A, comparable cytotoxic effects were observed in LRF-NK and PB-NK cells. The mean ± standard deviation of spontaneous and maximum lysis of K562 cells, detected by Annexin V and 7AAD, were 8.0 ± 1.0 and 90 ± 3.0, respectively. When evaluating the cytotoxic impact on the seventh-day post-NK cell isolation, both LRF-NK and PB-NK cells exhibited experimental lysis rates of 29.0 ± 5.4% and 31.0 ± 3.7% of K562 cells, respectively(Fig. 3B). As shown in Fig. 3C Statistical analysis indicated no significant difference in the cytotoxic effect between PB and LRF-NK cells co-cultured with K562, U266-B1, and CCRF-CEM cell lines (P > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

The cytotoxic effect of LRF-NK and PB-NK cells against CFSE-labeled target cell lines. (A) Flow cytometric representation of spontaneous and maximum lysis of the K562 cell line and experimental lysis following co-culture with LRF-NK cells was detected by Annexin V and 7AAD staining. (B) Statistical comparison of spontaneous, maximum, experimental, and specific lysis of the K562 cell line. (C) Mean percentages of specific lysis for K562, U266-B1, and CCRF-CEM cell lines following co-culture with LRF-NK and PB-NK cells. A significant increase in K562-specific lysis was observed compared to U266-B1 (P = 0.0184) and CCRF-CEM cells (P = 0.0194). No significant difference was observed in the specific lysis of U266-B1 and CCRF-CEM cell lines (P = 0.7306). LRF-NK and PB-NK cells showed no significant differences in inducing specific lysis across the three mentioned cell lines (P > 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD. (** rEpresents P < 0.001 and *** P < 0.0001, N = 3). LRF: Leukocyte reduction filter, PB: peripheral blood.

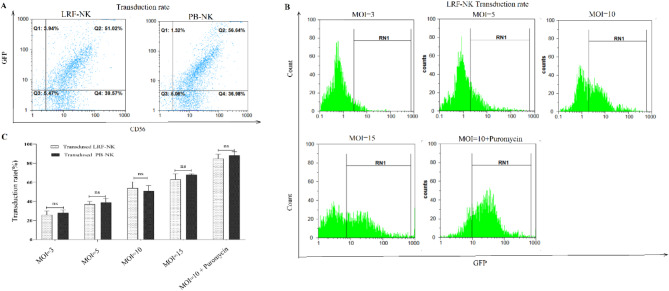

Generation of LRF-NK and PB-NK cells carrying the anti-BCMA CAR

Isolated PB and LRF-NK cells were transduced by the lentiviral vectors. The transduction efficiency was assessed by flow cytometry on day 3 post-transduction.

As depicted in Fig. 4A and B, the mean percentage of GFP-expressing cells, representing the transduction rate in transduced LRF-NK cells, was observed to be 26.0 ± 4.0, 37.0 ± 8.0, 54.0 ± 7.0, 63.0 ± 4.0, and 84.0 ± 7.0 with MOI 3, 5, 10, 15, and MOI 10 supplemented with puromycin, respectively. Similarly, transduced PB-NK cells exhibited mean percentage GFP expression at 28.0 ± 5.0, 39.0 ± 4.0, 51.0 ± 8.0, 68.0 ± 6.0, and 88.0 ± 4.0 with MOI 3, 5, 10, 15, and MOI 10 supplemented with puromycin, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Transduction rate of LRF-NK and PB-NK cells. (A) Flow cytometry representation of the transduction rate of LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, detected through GFP expression. (B) Flow cytometric visualization of the transduction rate of LRF-NK cells at MOIs of 3, 5, 10, 15, and 10 supplemented with puromycin. (C) Statistical analysis revealed an augmented transduction rate with increasing MOI and puromycin treatment. No significant differences were observed in the transduction rates between LRF-NK and PB-NK cells (P > 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD. (** represents P < 0.001 and *** P < 0.0001, N = 3). LRF: leukocyte reduction filter, pb: peripheral blood.

Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in the transduction rates of NK cells derived from LRF and PB sources (P > 0.05). Furthermore, the viability of transduced LRF-NK cells with MOI 10 in puromycin was determined to be 95.0 ± 3.0% (Fig. 4C).

NK cells that underwent transduction with an MOI of 10, supplemented with puromycin, demonstrated a greater transduction rate than other experimental conditions. Consequently, these cells were subjected to analyses for the detection of CAR expression and assessments of cytotoxicity.

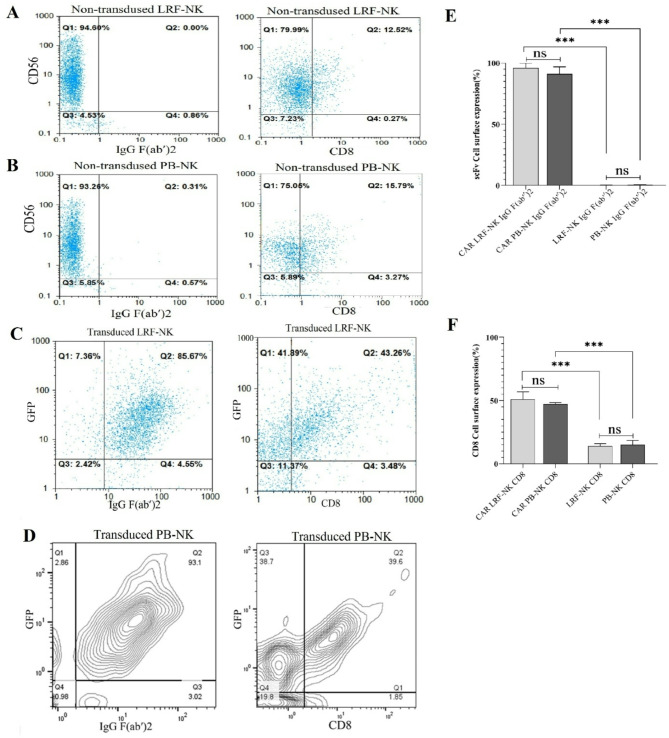

The high expression of CAR protein by transduced LRF-NK and PB-NK cells

The non-transduced LRF-NK and PB-NK cells underwent assessment for the absence of scFv and CD8 expression. In non-transduced LRF-NK, only 1.17 ± 0.47 and 14 ± 2% of CD56− cells exhibited positivity for IgG (Fab′)2 and CD8 markers, respectively (Fig. 5A,E,F). In non-transduced PB-NK, the mean expression levels of the same markers, IgG (Fab′)2 and CD8, by CD56− cells were 1.01 ± 0.13 and 15 ± 3%, respectively (Fig. 5B,E,F). The expression of scFv and CD8α on transduced LRF-NK, indicative of CAR protein presence, is shown in Figs. 5C and D. As depicted in Fig. 5E, the mean percentage of scFv expression was expressed at 96.0 ± 4.0 CAR LRF-NK, akin to the expression levels observed in PB-NK cells. No statistically significant disparities in scFv expression were noted between transduced LRF-NK and PB-NK cells (P > 0.05), affirming the successful transduction of both LRF-NK and PB-NK cells for CAR NK cell generation. As well as, As depicted in Fig. 5F, the mean percentage of CD8 expression was expressed at 50 ± 3.1 CAR LRF-NK, akin to the expression levels observed in PB-NK cells. No statistically significant disparities in scFv expression were noted between transduced LRF-NK and PB-NK cells (P > 0.05), affirming the successful transduction of both LRF-NK and PB-NK cells for CAR NK cell generation.

Fig. 5.

Anti-BCMA CAR expression on LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, emphasizing key aspects of scFv and CD8 expression. (A) Non-transduced LRF-NK cells lack scFv expression and low CD8 surface expression, detected by anti-IgG (Fab’)2 and Anti CD8 antibodies. (B) Similarly, non-transduced PB-NK cells show no scFv expression, detected by anti-IgG (Fab’)2 and low CD8 surface expression. (C) High expression of scFv and CD8 on GFP + transduced LRF-NK cells. (D) The scFv expressions by GFP+ transduced LRF NK cells are illustrated through the contour plot demonstration a significantly increased expression. (E) The scFv expressions by non-transduced LRF/PB NK cells in comparison with GFP+ transduced LRF/PB NK cells are illustrated through the contour plot demonstration a significantly increased expression (F). The CD8 expressions by non-transduced LRF/PB NK cells in comparison with GFP+ transduced LRF/PB NK cells are illustrated through the contour plot demonstration a significantly increased expression. LRF: leukoreduction filters, PB: peripheral blood.

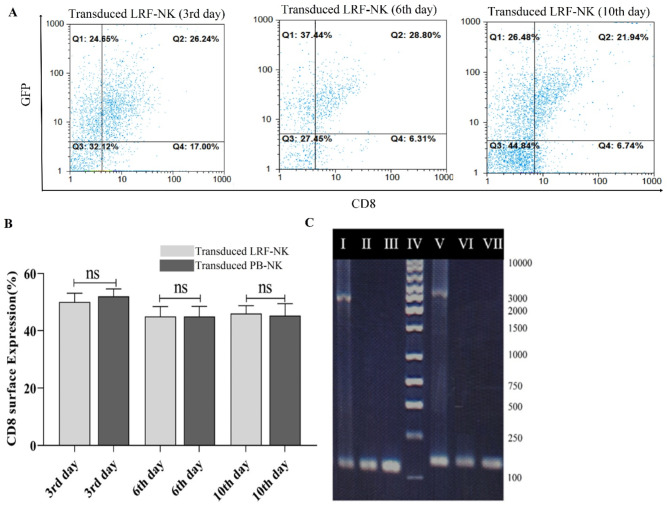

The persistent CAR protein expression and anti-BCMA CAR sequence integration in genomic DNA of transduced LRF-NK and PB-NK cells

To evaluate the persistent expression of CAR protein on the surface of transduced LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, we utilized flow cytometry to monitor the levels of the specified markers on days 3, 6, and 10 post-transductions.

As depicted in Fig. 6A and B, the mean percentage of CD8α expression in anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK cells (MOI = 10) remained consistently at 50.0 ± 3.1, 45.0 ± 3.5, and 46.0 ± 2.8 at 3-, 6-, and 10-days post-transduction, respectively. Similarly, the mean CD8α expression percentages for anti-BCMA CAR PB-NK cells were 52.0 ± 2.1, 45.0 ± 2.8, and 45.0 ± 4.2 at the corresponding time points.

Fig. 6.

Persistent Expression of Anti-BCMA CAR in LRF-NK Cells and Integration of CAR Construct into NK Cells. (A) Assessment of the sustained expression of the CAR construct through detecting the CD8 marker on GFP + transduced LRF-NK cells at days 3, 6, and 10 post-transductions. (B) Mean percentage of CD8 expression on transduced LRF-NK cells compared to PB-NK cells on days 3, 6, and 10 post-transduction. (C) Electrophoresis plot illustrating the integration of the CAR gene into NK cells. I: CD3ζ positive control, II: CD3ζ (CAR LRF-NK), III: CD3ζ (PB-NK), IV: 100 bp Ladder, V: scFv positive control, VI: scFv (CAR LRF-NK), VIII: scFv (CAR PB-NK).

Moreover, validation of the integration of the anti-BCMA CAR sequence into the genomic DNA of transduced LRF-NK and PB-NK cells was conducted. Molecular confirmation involved the utilization of primers specific for CD3ζ, yielding a product size of 162 bp, and scFv, yielding a product size of 122 bp. These primers were strategically positioned at the initiation and termination points of the CAR construct. The graphical representation in Fig. 6C visually attests to the successful integration, thereby furnishing molecular substantiation for the enduring presence of the anti-BCMA CAR sequence within the genomic DNA of both transduced LRF-NK and PB-NK cells.

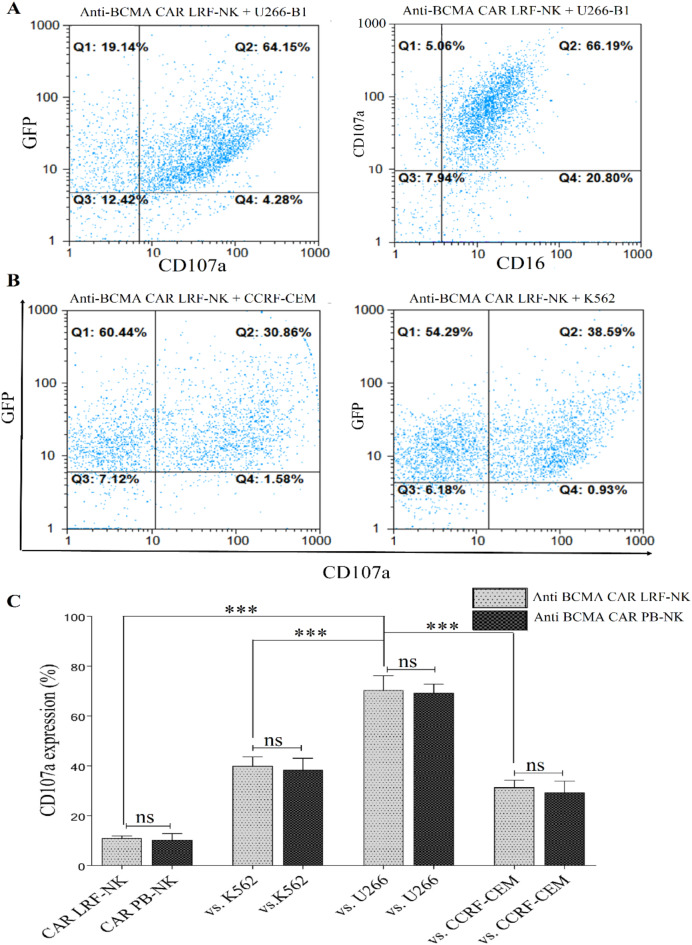

Analogous and highly specific CD107a expression in anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and PB-NK cells upon BCMA+ target cell recognition

In the evaluation of cytotoxic effects, co-culturing anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and PB-NK cells with U266-B1, CCRF-CEM, and K562 cell lines revealed analogous and highly specific CD107a expression levels (Fig. 7A and B ). The mean percentages of CD107a expression were 70.3 ± 4.78, 31.3 ± 2.35, and 40 ± 2.9 for LRF-NK, and 69.3 ± 2.86, 29.3 ± 3.68, and 38 ± 3.85 for PB-NK when interacting with the respective target cells (Fig. 7C). Additionally, the baseline expression levels of CD107a on anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, when cultured alone, were measured at 11 ± 0.8 and 10.3 ± 2.05, respectively (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

High cytotoxicity of anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and PB-NK cells against BCMA-expressing cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis depicts CD107a expression on anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK cells (GFP+ population) post-co-culture with U266-B1 cells (BCMA+ cells). (B) the mean percentage of CD107a expression on anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK cells (GFP+ population) after co-culture with CCRF-CEM (BCMA− cells) and K562 cell lines. (C) Statistical analysis indicates significantly elevated CD107a expression on anti-BCMA CAR LRF- and PB-NK cells when co-cultured with U266-B1 compared to CCRF-CEM and K562 cells. No significant difference in CD107a expression exists between anti-BCMA CAR LRF- and PB-NK cells. Data presented as Mean ± SD. (** Represents P < 0.001, and *** P < 0.0001, N = 3). LRF: Leukocyte reduction filter. PB: peripheral blood.

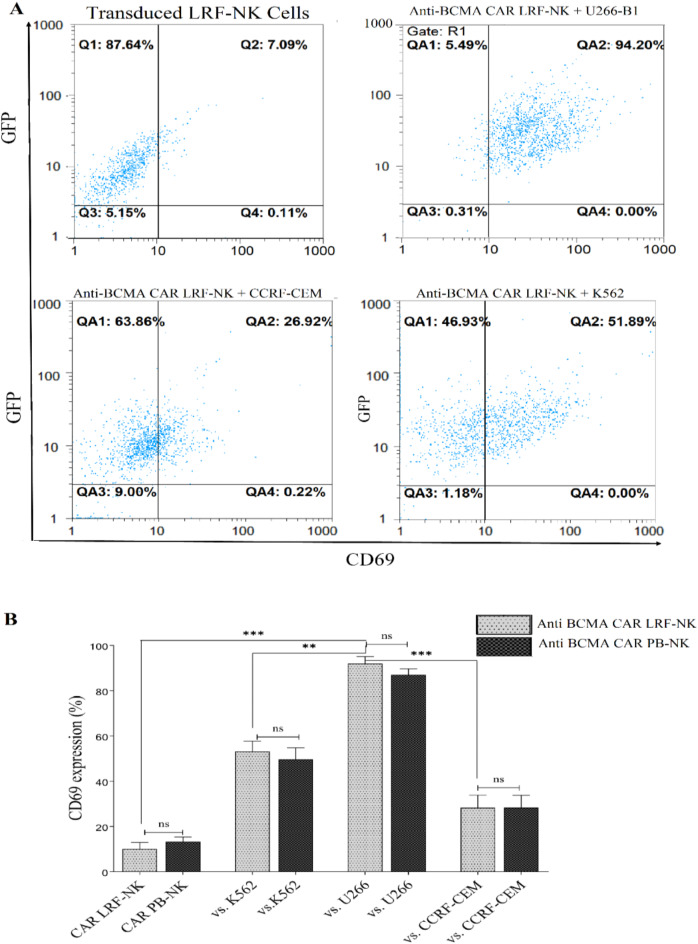

Analogous and highly specific CD69 expression in Anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and PB-NK cells upon BCMA+ target cell recognition

CD69 surface expression as an NK cell early activation marker was measured through Co-culturing anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and anti-BCMA CAR PB-NK cells with U266-B1, CCRF-CEM, and K562 cell lines and revealed analogous and highly specific anti BCMA CAR LRF/NK cell activation (Fig. 8A). The mean percentages of CD69 expression were 92.3 ± 2.5, 28.2 ± 4.6, and 53.2 ± 3.7 for Anti BCMA LRF-NK, and 87.3 ± 2.2, 28.3 ± 4.5, and 49.7 ± 4.2 for Anti BCMA PB-NK when interacting with the respective target cells. Additionally, the baseline expression levels of CD69 on anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and PB-NK cells, when cultured alone, were measured at 10 ± 2.4 and 13.3 ± 1.7, respectively (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Specific activation of transduced NK cells. (A) The baseline expression levels of CD69 (upper left) on anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK cells, when cultured alone and CD69 expression following the co-cultivation of anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK cells with U266-B1 (upper right) CCRF-CEM (Lower Left) and K562 (lower left) cell lines. (B) The mean percentage of CD69 as an early activation marker significantly increased on anti-BCMA CAR LRF/PB cells following co-cultivation with the U266-B1 compared to CCRF-CEM cell lines.

Elevated and specific IFN-γ and Granzyme B expression by anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and PB-NK Cells in response to BCMA+ target cells

IFN-γ and Granzyme B (GrB) expression were assessed as cytotoxic markers using a real-time PCR method following treatment of all groups with IL-2. As depicted in Fig. 9, the expression of IFN-γ (Fig. 9A) and GrB (Fig. 9B) by both LRF-NK and PB-NK cells significantly increased after co-culture with K562 as an NK-sensitive cell line, compared to NK cells treated solely with IL-2, control group ( P < 0.0001). Additionally, there was a substantial over-expression of IFN-γ and GrB in NK cells co-cultured with K562 compared to those co-cultured with U266-B1 and CCRF-CEM cell lines (P < 0.0001). The expression of both cytotoxic markers by NK cells over U266-B1 and CCRF-CEM cell lines was elevated compared to the control group. However, no significant differences were observed between NK cells co-cultured with BCMA-positive and BCMA-negative cell lines, revealing unspecific and conventional activation of NK cells against cancer cells. Furthermore, both LRF-NK and PB-NK cells showed no significant differences in the production of IFN-γ and GrB following co-culture with their respective target cell lines (P > 0.05).

Fig. 9.

mRNA expression of IFN-γ (A) and granzyme B (B) in anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK and PB-NK cells following co-culture with U266-B1 (BCMA+), CCRF-CEM (BCMA−), and K562 Cell Lines. The augmented expression of IFN-γ and granzyme B was evident in LRF-NK and PB-NK cells after co-cultivation with the K562 cell line, as opposed to their counterparts co-cultivated with U266-B1 and CCRF-CEM cell lines, as well as IL-2 treated NK cells. No statistically significant distinctions were discerned between LRF-NK and PB-NK cells. Conversely, Anti-BCMA CAR NK cells demonstrated a notable increase in the expression of IFN-γ and GrB after co-culture with U266-B1 compared to CCRF-CEM. The absence of significant differences between LRF and PB CAR NK cells in IFN-γ and GrB expression under identical conditions is noteworthy. Notably, a significantly heightened expression of IFN-γ and GrB in CAR NK cells compared to regular NK cells was observed after co-culture with U266-B1 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. (Double asterisks (**) signify P < 0.001, and triple asterisks (***) denote P < 0.0001; N = 3). LRF: leukocyte reduction filter. PB: peripheral blood.

In contrast, the engineered NK cells, designed as anti-BCMA CAR NK cells, demonstrated significantly elevated levels of IFN-γ and GrB expression upon co-culture with the BCMA-positive cell line U266-B1 compared to co-culture with the BCMA-negative cell line CCRF-CEM (P < 0.001). This underscores the specific recognition and activation of anti-BCMA CAR NK cells in response to BCMA-positive target cells. Moreover, the expression of IFN-γ and GrB by anti-BCMA CAR LRF-NK cells against U266-B1 cells was significantly increased compared to IL-2 treated NK cells co-cultured with U266-B1 (P < 0.0001 for both) and K562 cell lines (P < 0.0001 for both). Notably, no significant differences were observed in the expression of IFN-γ and GrB between LRF and PB CAR NK cells following co-culture with BCMA+/− cell lines (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The redirection of natural killer (NK) cells against tumor cells represents a promising strategy for enhancing the recognition of targeted antigens and optimizing their responsiveness in the context of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) cell immunotherapy27. However, a critical challenge in the field has been the identification of a safe, cost-effective, and high-yield source of NK cells for CAR-NK cell therapy14.

The distinct advantage of CAR-NK cells lies in their reduced risk of alloreactivity and subsequent GVHD, even when utilizing allogeneic NK cells. This flexibility enables the generation of CAR-NK cells from diverse sources, including NK-92 cell lines, PBMCs, UCB, and iPSCs3,28,29. Despite this potential, certain limitations have hampered the efficacy and widespread adoption of these cellular sources.

Peripheral blood and bone marrow serve as secure reservoirs of NK cells, yet challenges such as insufficient cell counts and complexities associated with volunteer recruitment have been encountered. Notably, NK-92 cells exhibit stable CAR expression but are marked by limitations such as the absence of CD16 and NKp44 expression. Additionally, their tumoral nature necessitates pre-injection irradiation, impacting their lifespan and proliferative capacity and resulting in short-lived responses3. Cord blood-derived natural killer (NK) cells, despite demonstrating elevated proliferation capacity, safety, and persistence in CAR NK trials, manifest heterogeneity when contrasted with other NK cell sources such as NK-92 and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived NK cells. Moreover, they exhibit diminished expression levels of natural cytotoxicity receptors14,30. iPSC-derived NK cells present a homogeneous off-the-shelf product with reduced cytokine release but demonstrate a high killing capacity. However, their adoption is hindered by cost considerations, potential immunogenicity, and the risk of malignant transformation14,31,32. Thus, the quest for an ideal NK cell source for CAR-NK cell therapy involves navigating a complex landscape of advantages and limitations associated with each cellular origin.

In the current investigation, we aimed to isolate NK cells from leukocyte reduction filters (LRF) and compare them with peripheral blood-derived NK (PB-NK) cells in terms of viability, cytotoxicity, and proliferation following interleukin-2 (IL-2) treatment, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The NK cell isolation from LRF employed a modified back-flushing method involving a two-step process of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and monocyte depletion, resulting in enhanced lymphocyte purity. Post-magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) column separation, the purity of LRF-NK cells reached 95%. Viability and proliferation analyses revealed no significant differences between LRF-NK and PB-NK cells across varying IL-2 doses up to 14 days post-isolation. Both cell populations exhibited robust proliferation capacity, with over 90% viability, indicating the preservation of NK cell viability and proliferation potential within LRF (Fig. 2).

Peripheral blood NK cells are typically categorized into two significant phenotypes: CD56dimCD16bright and CD56brightCD16dim/neg33. The CD56dimCD16bright NK cell subset expresses high levels of KIRs, the CD57 maturation marker, and mediates natural and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, exhibiting high levels of perforin expression and enhanced killing effect33,34. However, the CD56brightCD16dim/neg NK cells are characterized by NKG2A expression and low levels of perforin. Usually, these kinds of cells are primarily specialized for cytokine production34,35.

Immunophenotyping of LRF-NK cells in our study revealed a distribution of 86 ± 3.2% CD56dimCD16bright and 14 ± 4% CD56brightCD16dim/neg cells, mirroring the proportions observed in PB-derived NK cells (Fig. 1D). This indicates NK cells retained their normal phenotypic characteristics within the LRF filter.

NK cells were co-cultured with K562, U266-B1, and CCRF-CEM cell lines to assess cytotoxicity. Our data demonstrated that LRF-NK cells exhibited a high cytotoxic effect comparable to PB-NK cells (Fig. 3), indicating that LRF-NK cells maintained their proliferation, phenotypic, and cytotoxic characteristics during preservation in LRFs, with no significant differences from normal PB-NK cells.

Leukocyte reduction filters are typically discarded after producing packed red blood cells devoid of white blood cells and platelets, which can be returned for clinical use. These filters offer a readily available, cost-effective, and relatively safe source of NK cells, as they undergo strict screening for common blood-borne infectious agents, including hepatitis and HIV viruses, during blood donation19,21.

In this context, M. Valizadeh isolated monocyte-derived dendritic cells from leukocyte reduction filters (LRFs) and found no significant differences compared to dendritic cells from conventionally derived buffy coat monocytes in terms of morphology, surface markers, antigen uptake potency, and IL-12 secretion36. Furthermore, Peytour developed a method to harvest highly enriched CD34 + cells from LRFs, demonstrating their functional equivalence to those obtained from bone marrow, cord blood, and peripheral blood20. Our results, in alignment with these studies, suggest that LRFs represent a novel source of leukocytes with a highly desirable yield and maintained features across various aspects, including viability, proliferation, and functional capability.

We aimed to employ NK cells derived from leukoreduction filters (LRF) for the generation of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-NK cells specifically targeting the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA). These were systematically compared with CAR-NK cells sourced from peripheral blood. The primary objective involved utilizing LRF-NK cells in the development of anti-BCMA CAR-NK cells, employing a pre-existing CAR construct. This comparison focused on discerning the characteristics of CAR-NK cells derived from LRF-NK cells against those designed from peripheral blood NK cells.

Effective NK cell therapy often requires a substantial quantity of NK cells, ranging from 105 to 108 cells/kg, for optimal therapeutic outcomes14. Our successful isolation of approximately 108 NK cells per filter aligns with this optimal cell count for patient-based immunotherapy. This advantageous count can be obtained with just one LRF, reducing variability between different donors and offering an allogeneic source for CAR LRF-NK cells, thereby serving as an off-the-shelf treatment option. Importantly, patients with multiple myeloma (MM) often exhibit significantly reduced NK cell counts during advanced stages of the disease, coupled with limited cytotoxic activity. NK cell-based therapy can restore NK cell count and enhance cytotoxic abilities37.

Despite the numerous benefits of CAR NK cell therapy, a significant hurdle has been the lack of an efficient gene transfer method in primary NK cells3,38,39. Building on our previous studies, wherein pretreatment of NK cells with IL-2, polybrene, and spinoculation in lentivirus-based transduction achieved transduction rates of 50–65% with MOI 10 and 15 and 90% transduction rate with MOI 10 when using puromycin without compromising viability26,40.

In addition to employing F(ab’)2-anti human IgG to detect CAR expression on the surface of NK cells, we proposed simultaneous detection of CD8, an extracellular part of the CAR construct. The data in Figs. 5C and D indicate that the mean percentage of CD8 expression on both LRF and PB-CAR NK cells with MOI 10 and puromycin was approximately 50% at day 3, serving as a novel marker for CAR detection, as demonstrated previously in the CAR T-cell model26. Notably, the low expression of CD8 expression on NK cells provides a reliable means of detecting CD8 (extracellular domain) as a marker for CAR expression on the surface of CAR NK cells, minimizing the risk of false-positive results compared to CAR T cells. Therefore it is suggested that the investigation of the frequency of hinge domain expressing population and the intensity of expression be considered as a preliminary approach to confirm the expression of the desired construct. Additionally, the data demonstrate sustained CAR expression on transduced NK cells, as depicted in Fig. 6A.

CD107a and CD69 expression serves as crucial markers associated with NK cell-mediated lysis of target cells and cytokine secretion, providing valuable insights into effector cell activation41,42. Notably, studies by Han Dong and colleagues demonstrated significantly enhanced anti-NPM1c CAR-NK cell antitumor function through the evaluation of CD107a and IFN-gamma expression, indicating improved cytotoxicity43. Similarly, in a study on SARS-CoV-2, Minh Tuyet Ma observed a significant increase in CD107a surface expression on CAR-NK cells following co-culture with target cells, underscoring the activation of these effector cells44.

In alignment with these findings, our study, consistent with Yan Liu’s work, utilized CD107a expression and cytokine production to assess the function, specificity, and cytotoxicity characteristics of anti-BCMA CAR LRF- and PB-NK cells39. The results depicted in Figs. 7 and 8 revealed significantly elevated CD107a and CD69 expression on anti-BCMA CAR LRF- and PB-NK cells following co-culture with U266-B1, emphasizing the specific cytotoxicity against the targeted antigen. Furthermore, as depicted in Fig. 9 our data demonstrated no significant differences in IFN-γ and GrB expression between LRF-NK and PB-NK cells and their respective anti-BCMA CAR-NK cells, signifying comparable cytotoxic function. Importantly, both anti-BCMA CAR-NK cell types exhibited significantly higher expression of these factors after co-culture with U266-B1 cells compared to conventional NK cells, indicating the specificity and sensitivity of CAR-NK cells in recognizing BCMA as the targeted antigen.

Consequently, LRF-NK cells, offering an “off-the-shelf” product, emerge as a promising source in CAR-NK cell therapy. CAR-LRF NK cells eliminate the need for personalized products, addressing a significant challenge in current CAR-T cell therapies, which often involve substantial delays between CAR cell indication and patient infusion, reaching up to 2 months—a critical time lapse for patients with uncontrolled refractory malignancies.

Conclusion

Despite the substantial advantages of CAR-NK cell therapy, the limitation in sourcing NK cells has posed a significant obstacle. Our findings propose LRF as a novel and viable source for CAR-NK cell therapy. LRF-derived NK cells exhibit phenotypic, proliferative, and cytotoxic characteristics comparable to those derived from peripheral blood, as reflected in CAR cells originating from these sources. The abundance, safety, potential cost-effectiveness, and preserved features make CAR LRF-NK a compelling off-the-shelf treatment option for patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all colleagues in the Blood Transfusion Research Center labs in IBTO for their kind contributions to this project.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by A.M and M.Kh. A.M wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and the writing – review, and editing were done by M.Kh. All authors have read the manuscript and agreed to publish it. M. Kh and Gh. Kh has acquired financial support for the project leading to this manuscript. (Grant No 1089)

Funding

This study received financial support from the High Institute for Research and Education in Transfusion Medicine (IBTO) [Grant no IR.TMI.REC.1398.009] and Bushehr University of Medical Sciences [Grant no 1089]. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, publication decision, or manuscript preparation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Gh.Khamisipour], upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Maryam Kheirandish and Gholamreza Khamisipour contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Maryam Kheirandish, Email: M.Kheirandish@ibto.ir.

Gholamreza Khamisipour, Email: Khamisipourgholamreza@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Shin, M. H. et al. NK cell-based immunotherapies in cancer. Immune Netw.20(2) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Feins, S., Kong, W., Williams, E. F., Milone, M. C. & Fraietta, J. A. An introduction to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Am. J. Hematol.94(S1), S3–S9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie, G. et al. CAR-NK cells: A promising cellular immunotherapy for cancer. EBioMedicine59, 102975 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miliotou, A. N. & Papadopoulou, L. C. CAR T-cell therapy: a new era in cancer immunotherapy. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol.19(1), 5–18 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu, Y., Tian, Z. & Zhang, C. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-transduced natural killer cells in tumor immunotherapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin.39(2), 167 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma, P. et al. Immune checkpoint therapy—current perspectives and future directions. Cell186(8), 1652–1669 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao, Y. et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy for solid tumor treatment: progressions and challenges. Cancers14(17) (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Wu, Y., Yang, Z., Cheng, K., Bi, H. & Chen, J. Small molecule-based immunomodulators for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kim, D. W. & Cho, J-Y. Recent advances in allogeneic CAR-T cells. Biomolecules10 (2), 263 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujiwara, K., Masutani, M., Tachibana, M. & Okada, N. Impact of ScFv structure in chimeric antigen receptor on receptor expression efficiency and antigen recognition properties. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.527(2), 350–357 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu, H., Zhao, X., Li, Z., Hu, Y. & Wang, H. From CAR-T cells to CAR-NK cells: A developing immunotherapy method for hematological malignancies. Front. Oncol.11, 720501 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabbah, M. et al. CAR-NK cells: A chimeric hope or a promising therapy?? Cancers14(15), 3839 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marofi, F. et al. CAR-NK cell: a new paradigm in tumor immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2078 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 14.Gong, Y., Klein Wolterink, R. G. J., Wang, J., Bos, G. M. J. & Germeraad, W. T. V. Chimeric antigen receptor natural killer (CAR-NK) cell design and engineering for cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol.14(1), 73 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruppel, K. E., Fricke, S., Köhl, U. & Schmiedel, D. Taking lessons from CAR-T cells and going beyond: Tailoring design and signaling for CAR-NK cells in cancer therapy. Front. Immunol.13, 976 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maalej, K. M. et al. CAR-cell therapy in the era of solid tumor treatment: current challenges and emerging therapeutic advances. Mol. Cancer. 22(1), 20 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu, J. et al. Natural killer cells: A promising immunotherapy for cancer. J. Translational Med.20(1), 1–19 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebrahimiyan, H. et al. Novel insights in CAR-NK cells beyond CAR-T cell technology; promising advantages. Int. Immunopharmacol.106, 108587 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peytour, Y., Villacreces, A., Chevaleyre, J., Ivanovic, Z. & Praloran, V. Discarded leukoreduction filters: A new source of stem cells for research, cell engineering and therapy? Stem Cell. Res.11(2), 736–742 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peytour, Y. et al. Obtaining of CD34 + cells from healthy blood donors: Development of a rapid and efficient procedure using leukoreduction filters. Transfusion50(10), 2152–2157 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bashiri Dezfouli, A. et al. Optimizing the recovery of peripheral blood mononuclear cells trapped in leukoreduction filters—A comparison study. Hematol. Transfus. Cell. Therapy44, 197–205 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimopoulos, M-A., Richardson, P. & Lonial, S. Treatment options for patients with heavily pretreated relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk.22(7), 460–473 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen, A. D. et al. B cell maturation antigen–specific CAR T cells are clinically active in multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Investig.129(6), 2210–2221 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng, D. & Sun, J. Overview of anti-BCMA CAR‐T immunotherapy for multiple myeloma and relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Scand. J. Immunol.92(2), e12910 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CRS CRS, NT NT, Lymphohistiocytosis H. US Food and Drug Administration approves Bristol Myers Squibb’s and bluebird bio’s Abecma (idecabtagene vicleucel), the first anti-BCMA CAR T cell therapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Abecma is a first-in-class BCMA-directed personalized immune cell therapy delivered as a one-time infusion for triple-class exposed patients with multiple survival. 5, 11−2 (2021).

- 26.Moazzeni, A., Kheirandish, M., Khamisipour, G. & Rahbarizadeh, F. Directed targeting of B-cell maturation antigen-specific CAR T cells by bioinformatic approaches: from in-silico to in-vitro. Immunobiology228(3), 152376 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valeri, A. et al. Overcoming tumor resistance mechanisms in CAR-NK cell therapy. Front. Immunol.13, 4208 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daher, M., Melo Garcia, L., Li, Y. & Rezvani, K. CAR-NK cells: the next wave of cellular therapy for cancer. Clin. Translational Immunol.10(4), e1274 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heipertz, E. L. et al. Current perspectives on off-the-shelf allogeneic NK and CAR-NK cell therapies. Front. Immunol.12, 732135 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, E. et al. Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia32(2), 520 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saetersmoen, M. L., Hammer, Q., Valamehr, B., Kaufman, D. S. & Malmberg, K-J. Off-the-shelf Cell Therapy with Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived Natural Killer Cells (Seminars in immunopathology, 2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Lu, S-J. & Feng, Q. CAR-NK cells from engineered pluripotent stem cells: Off-the-shelf therapeutics for all patients. Stem Cells Transl. Med.10(S2), S10–S7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rad, H. A. et al. Evaluation of peripheral blood NK cell subsets and cytokines in unexplained recurrent miscarriage. J. Chin. Med. Association. 81(12), 1065–1070 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michel, T. et al. Human CD56bright NK cells: An update. J. Immunol.196(7), 2923–2931 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stabile, H., Fionda, C., Gismondi, A. & Santoni, A. Role of distinct natural killer cell subsets in anticancer response. Front. Immunol.8, 293 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valizadeh, M., Purfathollah, A. A., Raoofian, R., Homayoonfar, A. & Moazzeni, M. Optimized simple and affordable procedure for differentiation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells from LRF: An accessible and valid alternative biological source. Exp. Cell Res.406(2), 112754 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pazina, T. et al. Alterations of NK cell phenotype in the disease course of multiple myeloma. Cancers13(2), 226 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlsten, M. & Childs, R. W. Genetic manipulation of NK cells for cancer immunotherapy: Techniques and clinical implications. Front. Immunol.6, 266 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng, M., Chen, Y., Xiao, W., Sun, R. & Tian, Z. NK cell-based immunotherapy for malignant diseases. Cell Mol. Immunol.10(3), 230 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajabzadeh, A., Hamidieh, A. A. & Rahbarizadeh, F. Spinoculation and retronectin highly enhance the gene transduction efficiency of Mucin-1-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) in human primary T cells. BMC Mol. Cell. Biology. 22(1), 1–9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pera, A. et al. CMV latent infection improves CD8 + T response to SEB due to expansion of polyfunctional CD57 + cells in young individuals. PloS One9(2), e88538 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alter, G., Malenfant, J. M. & Altfeld, M. CD107a as a functional marker for the identification of natural killer cell activity. J. Immunol. Methods294 (1–2), 15–22 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong, H. et al. Engineered memory-like NK cars targeting a neoepitope derived from intracellular NPM1c exhibit potent activity and specificity against acute myeloid leukemia. Blood136, 3–4 (2020).32614960 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma, M. T. et al. CAR-NK cells effectively target SARS-CoV-2-spike-expressing cell lines in vitro. Front. Immunol.12, 652223 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Gh.Khamisipour], upon reasonable request.