Summary

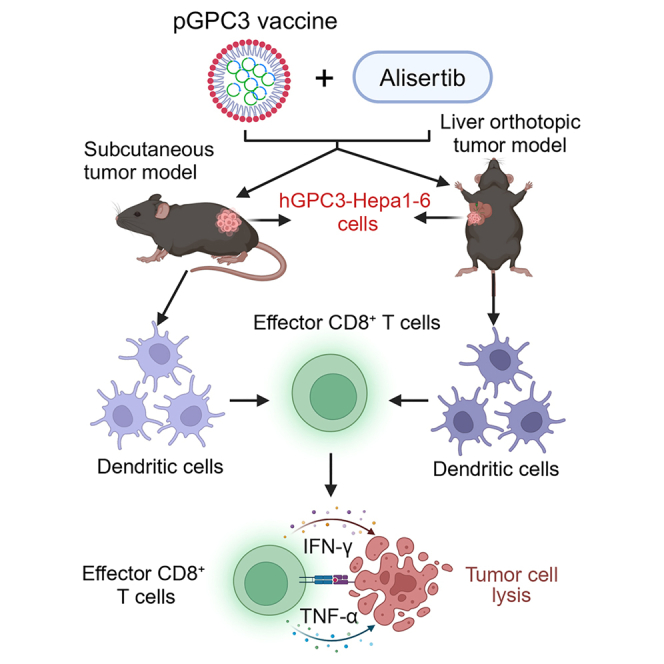

Alisertib is a potent aurora A kinase inhibitor in clinical trials for cancer treatment, but its efficacy on cancer vaccines remains unclear. Here, we developed a DNA vaccine targeting glypican-3 (pGPC3) and evaluated its efficacy with alisertib in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) models. The combination therapy of pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib significantly inhibited subcutaneous tumor growth, enhanced the induction and maturation of CD11c+ and CD8+CD11c+ dendritic cells (DCs), and expanded tumor-specific CD8+ T cell responses. CD8+ T cell depletion abolished the anti-tumor effects, underscoring the essential role of functional CD8+ T cell responses. Moreover, the combined treatment promoted memory CD8+ T cell induction, providing long-term protection. In liver orthotopic tumor models, the combination of pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib demonstrated potent therapeutic efficacy through CD8+ T cell responses. These results indicate that alisertib enhances the pGPC3 vaccine’s therapeutic effect, offering a promising strategy for HCC treatment.

Subject areas: Natural sciences, Biological sciences, Immunology, Systems biology, Cancer systems biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib inhibited subcutaneous tumor growth

-

•

The combination treatment relied on DC-mediated CD8+ T cell immune responses

-

•

This treatment provided a long-term anti-tumor effect by memory CD8+ T cells

-

•

This treatment effectively protected against liver orthotopic tumors

Natural sciences; Biological sciences; Immunology; Systems biology; Cancer systems biology

Introduction

Therapeutic cancer vaccines have emerged as a crucial focus in cancer immunotherapy, achieving notable advancements in recent years.1,2 These vaccines aim to harness the body’s immune system, particularly activating CD8+ T cell responses to destroy tumor cells, thus offering a potential treatment for various cancers.3,4 However, when used as monotherapy, cancer vaccines often struggle to overcome the immune evasion tactics employed by tumors.5 Tumor cells utilize sophisticated mechanisms, such as downregulating major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and increasing the recruitment of immunosuppressive cells, to inhibit CD8+ T cell responses.6 The relatively modest immune activation by vaccines results in suboptimal clinical outcomes in some patients, likely due to factors like individual variation, tumor heterogeneity, and the presence of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.7,8 Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (e.g., PD-1 or CTLA-4 antibodies) are designed to release the immune system from tumor-induced suppression, allowing for a stronger anti-tumor response.9 Combining cancer vaccines with ICIs generates a synergistic effect, enhancing anti-tumor efficacy.10,11 However, these inhibitors’ overall effectiveness and safety profiles remain areas of concern. As a result, there is an urgent need to explore novel strategies to boost the therapeutic potential of cancer vaccines, optimizing their efficacy in overcoming immune resistance and improving patient outcomes.

Alisertib is a selective aurora A kinase inhibitor that has shown promising potential in the treatment of various cancers.12 Aurora A kinase regulates the cell cycle, particularly during the process of mitosis.13,14 Its overactivity is closely linked to the proliferation and survival of tumor cells, making it an important target for anti-cancer therapies.15 Alisertib disrupts spindle assembly by inhibiting aurora A kinase, leading to cell-cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and ultimately triggering apoptosis in tumor cells.16 Studies have demonstrated that alisertib exhibits significant anti-tumor activity against several types of cancer, including breast cancer, colorectal cancer, liver cancer, and ovarian cancer.17,18,19,20 Moreover, alisertib has been found to enhance the sensitivity of tumor cells to radiotherapy.21 In clinical trials, alisertib achieves an overall response rate of 30%–35% in patients with relapsed/refractory peripheral T cell lymphoma, and it extends progression-free survival.22 Its use in small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) has also shown potential for improving chemotherapy sensitivity and prolonging patient survival.23 When combining with mTOR inhibitors or ICI, alisertib further enhances anti-tumor effects, especially in drug-resistant tumors.24,25 Therefore, combining treatment with alisertib may modulate immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, potentially improving the efficacy of therapeutic DNA vaccines.

Combination therapies have become central to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treatment, enhancing anti-tumor efficacy. ICIs like anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies reinvigorate exhausted T cells, and when combined with targeted therapies, they modulate the HCC tumor microenvironment.26 Atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) and bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) are the first approved combination therapy for HCC, showing superior survival benefits over sorafenib.27 Targeted therapies like lenvatinib and cabozantinib, which inhibit oncogenic pathways (VEGF, MET, and FGFR), also boost T cell activation when combined with ICIs.28 Preclinical models show that lenvatinib and bevacizumab normalize tumor vasculature and activate immunity.29 While tyrosine kinase inhibitors like sorafenib and regorafenib combined with anti-VEGF therapies have promising preclinical data, clinical validation is still needed.30 Vaccines targeting tumor antigens, such as glypican-3 (GPC3) and p53 mutations, induce T cell responses and can be combined with anti-PD-1 therapies for enhanced tumor suppression.31,32 Thus, combining DNA vaccines with therapies like alisertib represents a transformative approach to HCC treatment.

In this study, we designed a DNA vaccine targeting GPC3 and evaluated its therapeutic potential in combination with alisertib for the treatment of HCC in subcutaneous and orthotopic tumor models. The combination treatment of alisertib with the pGPC3 vaccine markedly suppressed tumor growth while promoting the infiltration of immune cells into the tumor microenvironment. This co-administration significantly enhanced dendritic cell (DC) antigen presentation and triggered a strong antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response, which played a critical role in mediating the observed anti-tumor effects. These pronounced anti-tumor responses were further validated in the liver orthotopic tumor model. Overall, our findings indicate that the combination of alisertib with tumor vaccines potentiates their efficacy, offering a promising strategy for treating solid tumors such as HCC.

Results

Effective vaccine antigen expression and high safety in the combination treatment with pGPC3 and alisertib

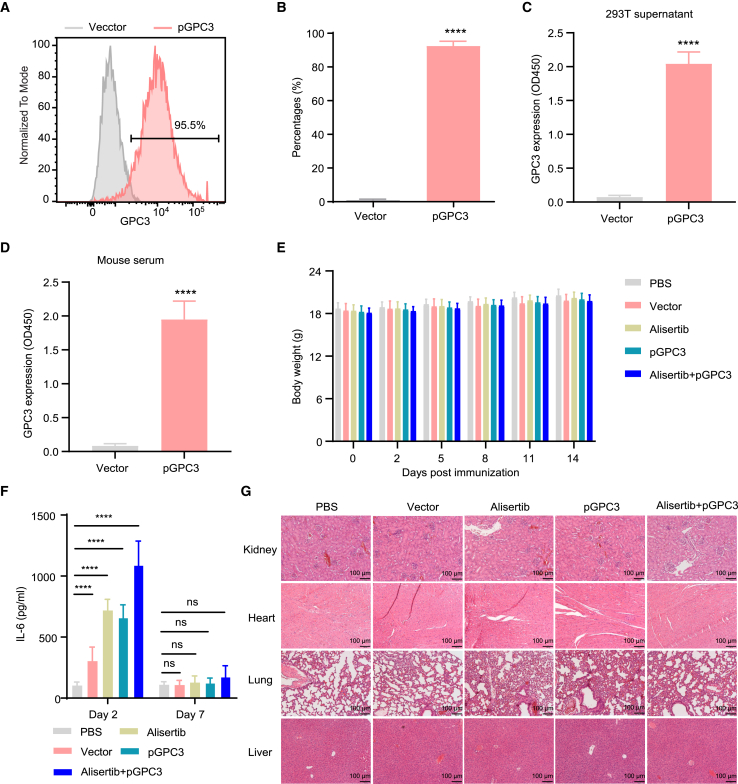

The efficiency of antigen expression by the vaccine determines the strength of the induced specific immune response, which plays a crucial role in tumor control.33 Therefore, we first evaluated the expression of pGPC3 vaccine in vitro. Intracellular staining was performed using flow cytometry, and the results showed that GPC3 expression in the pGPC3-transfected group was significantly higher than in the control group after transfecting 293T cells with pGPC3 via PLGA/PEI delivery (Figures 1A and 1B). Furthermore, the design of the pGPC3 vaccine included an N-terminal secretory signal peptide, and the GPC3 protein was secreted into the cell supernatant. ELISA analysis of the supernatant from pGPC3-transfected 293T cells revealed a significant increase in GPC3 protein levels (Figure 1C). To further verify in vivo vaccine antigen expression, mice were intramuscularly injected with the pGPC3 vaccine, and serum was collected 3 days later to detect GPC3 expression. Compared to the control group, significantly elevated levels of GPC3 protein were detected in the serum of mice immunized with the pGPC3 vaccine (Figure 1D). These results indicate that the pGPC3 vaccine can effectively express the GPC3 antigen protein both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of vaccine antigen expression and safety in the combination treatment of pGPC3 and alisertib

(A) GPC3 protein expression was analyzed by flow cytometry in pGPC3-transfected 293T cells.

(B) Quantification of the proportion of GPC3-positive cells from (A).

(C) The protein level of GPC3 was measured by ELISA in the supernatant of pGPC3-transfected 293T cells.

(D) The level of GPC3 protein was detected by ELISA in the serum of pGPC3-immunized mice.

(E) Body weight changes in tumor-bearing mice were monitored every 2–3 days across the PBS, vector, alisertib, pGPC3, and alisertib + pGPC3 treatment groups.

(F) Serum IL-6 levels were assessed via ELISA in mice treated with PBS, vector, alisertib, pGPC3, and the combination of alisertib and pGPC3.

(G) Histopathological analysis of kidney, heart, lung and liver tissues from treated mice was performed using HE staining. Scale bar: 100 μm. All experiments were conducted with 5 mice per group.

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were conducted using a two-tailed independent Student’s t test, while multiple group comparisons were performed using ANOVA. Statistical significance was defined as ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

For safety assessment, mice were treated with PBS, vector, alisertib, pGPC3, or a combination of alisertib and pGPC3. No significant differences in body weight were observed among the treatment groups (Figure 1E). Additionally, compared to the PBS control group, transient increase in the inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-6 was detected in the vector, alisertib, pGPC3, and combination treatment groups on the second day post treatment, but IL-6 levels returned to normal by day 7 (Figure 1F). Histological analysis showed no significant inflammatory responses in kidney, heart, lung, or liver tissues after treatment (Figure 1G). These data suggest that the combination treatment of alisertib and pGPC3 effectively expresses the antigen protein with minimal toxicity.

Administration of alisertib and pGPC3 vaccine inhibits tumor progression and enhances CD8+ T cell infiltration and DC maturation

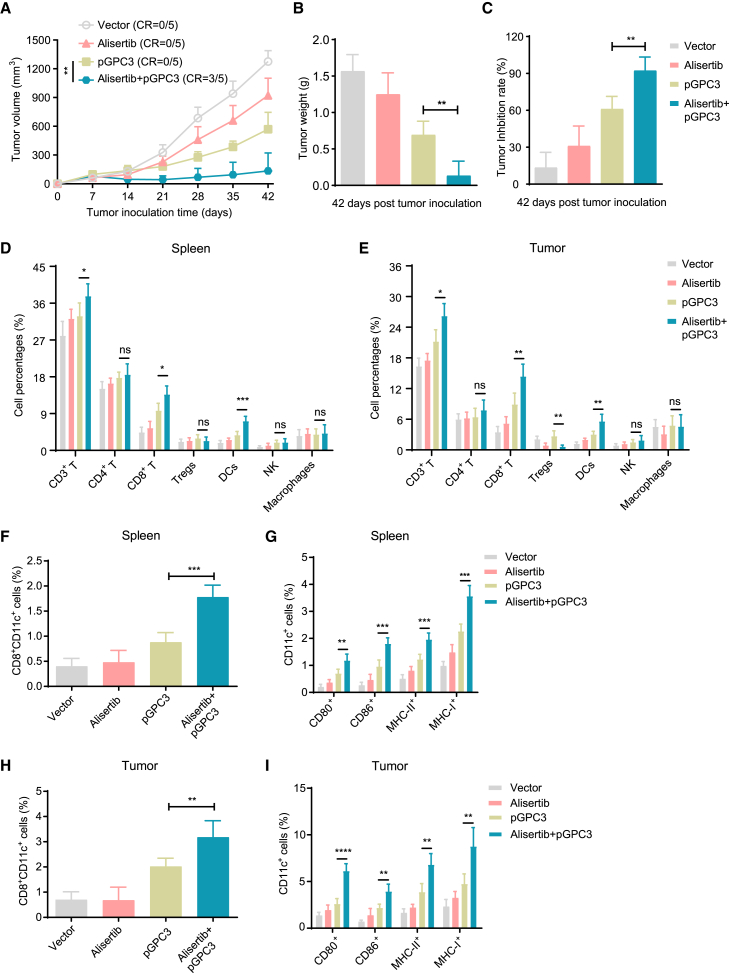

To evaluate the therapeutic effect of the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib, mice were subcutaneously injected with tumor cells to establish a subcutaneous tumor model and treated with vector, alisertib, pGPC3, and the combination of alisertib and pGPC3. A significant inhibition of tumor growth was observed in the combination therapy group (alisertib + pGPC3), where a complete response (CR, indicating the disappearance of all detectable tumors) was approximately 60%, while no CR was observed in the other treatment groups (Figure 2A). After the treatment period, tumors were surgically removed from the mice and weighed. The combination therapy group showed a significant reduction in tumor weight and an increase in the tumor inhibition rate (Figures 2B and 2C). Changes in the infiltrating immune cell subsets within the tumor microenvironment are critical for tumor control. Therefore, we first used flow cytometry to assess the effect of the vaccine combined with alisertib on immune subset modulation. The results showed that the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib promoted an increased proportion of CD3+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and DCs. There were no statistically significant differences in CD4+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, or macrophages in the spleen and tumor tissues from the treated mice (Figures 2D and 2E). Notably, the proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) was significantly reduced in the tumor tissues from the combination therapy group or alisertib group compared to the pGPC3 vaccine alone group (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Therapy efficacy and immune cell infiltration in a subcutaneous tumor model treated with the pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib

Mice were intramuscularly immunized with vector, pGPC3, on days 7, 17, and 27, or combined therapy with intraperitoneal injection of alisertib on days 10, 14, 17, 21, 24, and 27 following inoculation with hGPC3-Hepal1-6 cells.

(A) Tumor volumes were measured weekly from day 7 to day 42.

(B) Tumor weights were recorded on day 42 post inoculation.

(C) Tumor inhibition rates were calculated for each treatment group.

(D and E) Flow cytometric analysis of the percentages of CD3+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Tregs, DCs, NK cells, and macrophages in the spleens (n = 5) and tumors (n = 5) of mice treated with vector, alisertib, pGPC3, or the combination therapy.

(F) The percentages of CD8+CD11c+ cells in the splenocytes of each group were assessed by flow cytometry.

(G) Frequencies of DC subsets, including CD80+CD11c+, CD86+CD11c+, MHC-II+CD11c+, and CD40+CD11c+, in the spleens from each group.

(H) The percentages of CD8+CD11c+ cells in the tumors from each group were detected by flow cytometry.

(I) Frequencies of CD80+CD11c+, CD86+CD11c+, MHC-II+CD11c+, and CD40+CD11c+ DC subsets in tumors across all groups. All experiments were performed with 5 mice per group.

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Multiple group comparisons were performed using ANOVA. Statistical significance was set at ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

The CD8+CD11c+ DC subset can effectively present tumor antigens to CD8+ T cells and activate CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immune responses.34 Flow cytometry results showed a significant increase in the proportion of CD8+CD11c+ DC in spleens and tumors from the combination therapy group of alisertib and pGPC3 (Figures 2F and 2H). Further investigation revealed that the expression of DC activation surface markers, such as CD80, CD86, MHC-II, and MHC-I, was also significantly elevated in the spleens and tumors from the combination therapy group (Figures 2G and 2I), indicating that the combination therapy of alisertib and pGPC3 vaccine enhances DC maturation and induces a robust antigen-specific immune response. These results demonstrate that the combination therapy of alisertib and pGPC3 significantly inhibits tumor progression, promotes the infiltration of anti-tumor immune cells, while decreasing the presence of immunosuppressive cells.

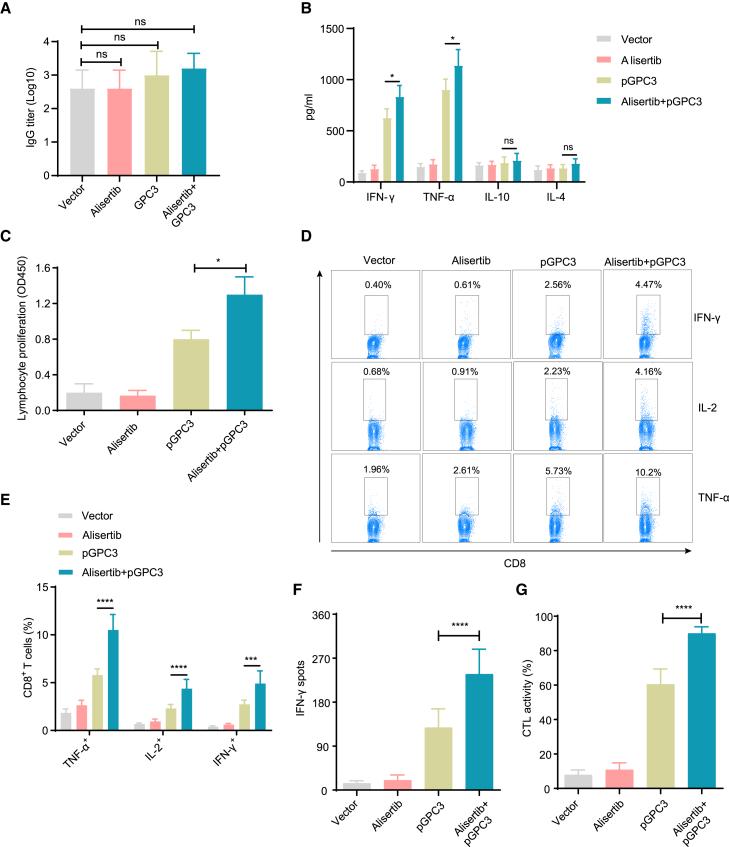

pGPC3 vaccine combining with alisertib induces strong cellular immune responses

To determine whether the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib enhances antigen-specific immune responses, we first assessed the changes in specific antibodies in the serum of treated mice. Compared to the vector, pGPC3, or alisertib treatment groups, the alisertib plus pGPC3 combination treatment group exhibited no significant difference in IgG antibody levels in tumor-bearing mice (Figure 3A), which may be attributed to the strong anti-hGPC3 antibody response induced by overexpression of hGPC3 in tumor cells. Furthermore, the Th1 cytokine levels (interferon-gamma [IFN-γ] and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) were notably higher in the group treated with alisertib and pGPC3 compared to the group treated with pGPC3 vaccine (Figure 3B). In contrast, the Th2 cytokine levels (IL-4 and IL-10) showed only slight variation between the combination treatment group and pGPC3 treatment group. These findings indicate that the alisertib plus pGPC3 treatment significantly boosted the Th1 immune response and T cell proliferation, which are critical for effective tumor cell elimination. Lymphocyte proliferation assay results showed that the combination therapy significantly promoted antigen-specific lymphocyte proliferation (Figure 3C). Functional CD8+ T cells secrete cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α, which effectively kill tumor cells and promote their own proliferation. Our results showed a significant increase in the percentages of IFN-γ+CD8+, IL-2+CD8+, and TNF-α+CD8+ T cells in the combination treatment group of alisertib and pGPC3 (Figures 3D and 3E). Additionally, in vitro ELISPOT assays further confirmed that the number of IFN-γ-secreting T cells was significantly higher in the combination treatment group compared to the single treatment groups (Figure 3F). Furthermore, we observed strong specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) killing activity in the combination therapy group (Figure 3G). These results indicate that the combination treatment of alisertib and pGPC3 effectively induces both strong specific humoral and cellular immune responses, which will be beneficial for tumor control.

Figure 3.

Humoral and cellular immune responses induced by pGPC3 and alisertib in a subcutaneous tumor model

(A) Anti-hGPC3 total IgG antibody levels in serum were measured by ELISA at day 35 post tumor inoculation.

(B) The expression levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-4 were quantified in the culture supernatants of splenocytes stimulated with hGPC3 protein (10 μg/mL) for 48 h using ELISA.

(C) Splenocytes isolated from treated mice (n = 5) were stimulated in vitro with IL-2 (100 U/mL) and hGPC3 protein (10 μg/mL) for 72 h; the cell proliferation assay was conducted and presented as optical density (OD) values.

(D) Splenocytes in RPMI 1640 complete medium containing IL-2 (100 U/mL) were stimulated with hGPC3 protein (10 μg/mL) for 72 h, followed by ionomycin (500 ng/mL), PMA (50 ng/mL), and BFA (5 μg/mL) for the final 5 h. Flow cytometry was used to analyze TNF-α, IL-2, and IFN-γ-expressing CD8+ T cells in each group.

(E) Statistical analysis of TNF-α, IL-2, and IFN-γ-expressing CD8+ T cell percentages from (D).

(F) The number of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells was measured using the ELISPOT assay.

(G) CTL activity was assessed using a co-culture-killing assay. All experiments were performed with 5 mice per group.

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Multiple group comparisons were performed using ANOVA. Statistical significance was set at ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

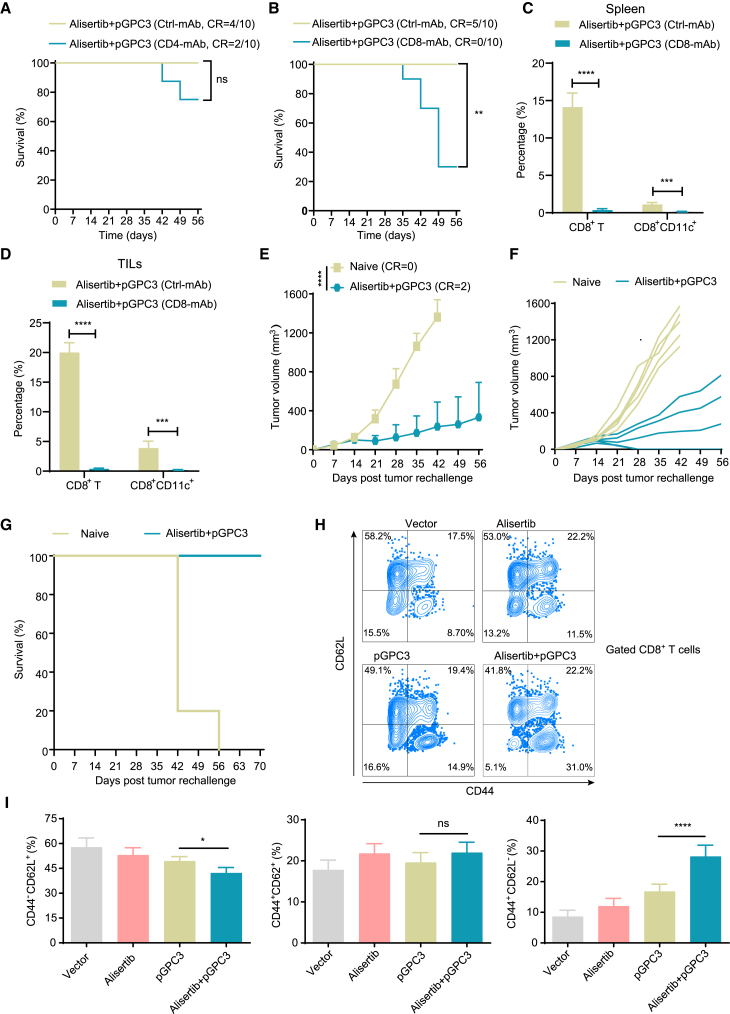

Combination treatment of pGPC3 and alisertib exhibits the long-term anti-tumor effect by enhancing the memory CD8+ T cell immune responses

The pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib induced a strong CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immune response. To investigate the essential role of CD8+ T cells in the anti-tumor effects of the combination therapy of pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib, we conducted in vivo CD4+ or CD8+ T cell depletion experiments. The results showed that administration of CD4+ T cell-depleting antibodies did not significantly abrogate the anti-tumor effects of the alisertib plus pGPC3 treatment (Figure 4A), but CD8+ T cell depletion significantly impaired the therapeutic efficacy of the combination therapy (Figure 4B). Correspondingly, CD8+ T cell depletion reduced the proportion of CD8+ T cells and CD8+CD11c+ DCs in both the spleen and tumor tissues (Figures 4C and 4D). To further determine whether the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib can provide long-term anti-tumor protection, we performed a tumor rechallenge in cured mice by the combination therapy of the pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib. The results of the rechallenge experiment indicated that tumor growth was significantly suppressed in the combination treatment group of alisertib and pGPC3, with 40% of the mice remaining tumor-free, while all tumors in the naive control group grew and were significantly larger than those in the combination treatment group (Figures 4E and 4F).

Figure 4.

Memory CD8+ T cells are essential for the long-term anti-tumor effect of pGPC3 and alisertib

(A and B) Survival curves of tumor-bearing mice treated with pGPC3 and alisertib after depletion of CD4+ T or CD8+ T cells.

(C and D) Percentages of CD8+ T cells and CD8+CD11C+ subsets in splenocytes and TILs, measured by flow cytometry.

(E) Tumor growth in cured mice after rechallenge with tumor cells.

(F) Individual tumor growth curves for each mouse in different groups were monitored up to 56 days post rechallenge; naive mice served as controls.

(G) Survival curves comparing rechallenged mice to naive controls (n = 5).

(H) Flow cytometry dot plots showing CD8+ memory T cell populations in splenocytes from four experimental groups (n = 5).

(I) Statistical analysis of the proportions of effector memory (CD62L−CD44+), central memory (CD44+CD62L+), and naive (CD44−CD62L+) CD8+ T cells in splenocytes from treated mice. All experiments were performed with 5 mice per group.

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were performed using a two-tailed independent Student’s t test. Multiple group comparisons were performed using ANOVA. Survival analysis was conducted using the log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Statistical significance was set at ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Observing the survival rate of the treated mice, we observed that the survival rate in the combination therapy group reached 100% by day 70, while all mice in the control group had to be sacrificed due to tumor burden by day 56 (Figure 4G). Memory CD8+ T cells are reactivated upon re-encountering tumor antigens, producing strong CTL effects to eliminate tumor cells. Therefore, we used flow cytometry to examine the changes in memory CD8+ T cells in the spleen. The pGPC3 vaccine combined with the alisertib treatment group showed a significantly increased proportion of effector memory CD8+ T cells and a reduced proportion of naive CD8+ T cells, but the proportion of central memory CD8+ T cells did not change significantly (Figures 4H and 4I). These results indicate that the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib induces long-term anti-tumor effects by enhancing memory CD8+ T cell immune responses.

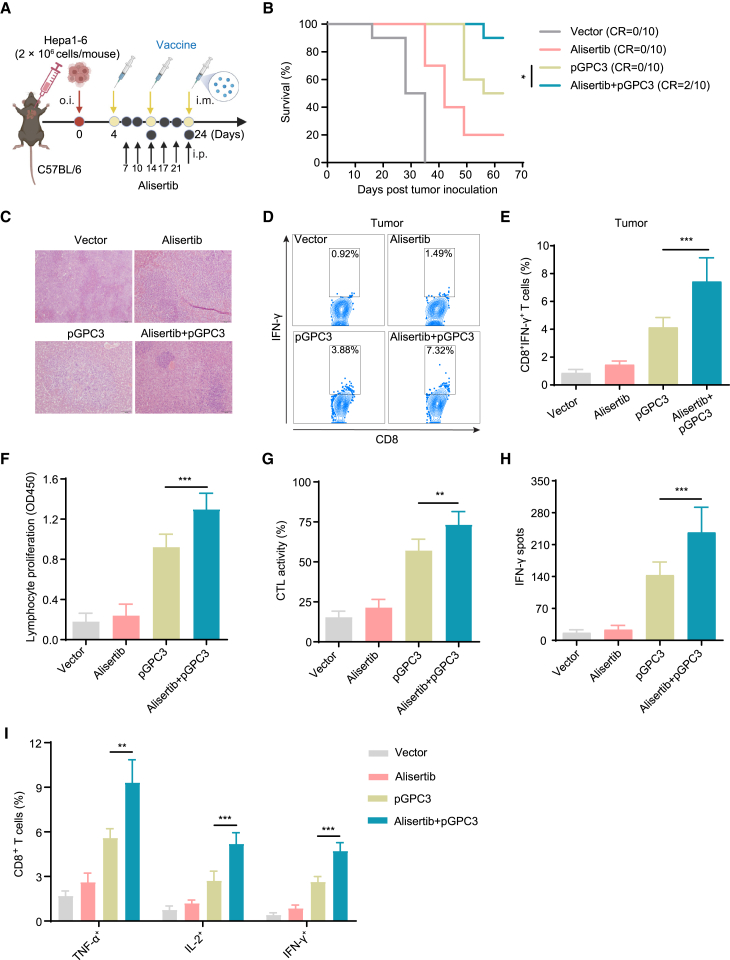

Treatment with pGPC3 and alisertib suppresses tumor growth in orthotopic tumor models

To further investigate the therapeutic efficacy of the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib in an orthotopic liver tumor model, mice were orthotopically injected with tumor cells into the liver on day 0. The treatment with the vaccine (intramuscular immunization on days 4, 14, and 24) and alisertib (intraperitoneal injection on days 7, 10, 14, 17, 21, and 24) was administered after tumor injection (Figure 5A). After treatment, we monitored the survival of the mice until day 63 post tumor injection. The results showed that the combination therapy of alisertib and pGPC3 significantly improved the survival rate of the tumor mice (survival rate of 90%) compared to the other control groups (Figure 5B). After the treated mice were sacrificed, liver tissues were surgically removed, and tumor nodules were examined by histological staining. The results showed that the combination therapy group had fewer and smaller tumor nodules (Figure 5C). Furthermore, there was a significant increase in the infiltration of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells in the liver tumor tissues from the combination therapy group compared to the other control groups (Figures 5D and 5E). Correspondingly, increased lymphocyte proliferation, stronger CTL cytotoxic activity, and a higher number of IFN-γ-secreting T cells were also observed in the pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib combination therapy group (Figures 5F–5H). In addition, the proportion of functional CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α was significantly higher in the combination therapy group (Figure 5I). These results indicate that the combination therapy of pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib effectively inhibits the growth of orthotopic liver tumors by inducing strong CD8+ T cell immune responses.

Figure 5.

The combination therapy of pGPC3 and alisertib inhibited liver tumor progression

(A) Mice were orthotopically inoculated with Hepa1-6 cells on day 0 and treated with vector or pGPC3 on days 4, 14, and 24, alisertib or alisertib + pGPC3 on days 7, 10, 14, 17, 21, and 24 post tumor inoculation.

(B) Survival of liver tumor-bearing mice was monitored up to 63 days after inoculation.

(C) HE staining of liver sections showing tumor foci from representative mice in each treatment group.

(D and E) Flow cytometric analysis of the percentages of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in each group.

(F) Lymphocyte proliferation.

(G) CTL activity analysis.

(H) Quantification of IFN-γ-secreting T cells using ELISPOT assay.

(I) Flow cytometric analysis of the percentages of TNF-α, IL-2, and IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells in stimulated splenocytes from each treatment group. Survival experiments involved 10 mice per group, while other assays were conducted with 5 mice per group.

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Survival analysis was performed using the log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Multiple group comparisons were performed using ANOVA. Statistical significance was set at ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Discussion

GPC3 is a cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is highly expressed in most HCC cells but minimally expressed in normal adult tissues, making it a key therapeutic target for HCC.35 Strategies targeting GPC3 in liver cancer treatment include GPC3 antibody-drug conjugates, chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, and vaccine therapies.36,37,38 As a promising immunotherapy approach, the GPC3 vaccine activates the body’s immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells.39 Compared to traditional cancer therapies, vaccine treatment offers several advantages including high specificity, the potential for long-term immune memory, enhanced synergy with other therapies, reduced tumor immune evasion, and low toxicity.40 The GPC3 peptide vaccine shows limited response in patients with HCC with GPC3-positive tumors in clinical study.41,42 HMGB1 enhancing GPC3 vaccine or GPC3-coupled lymphocytes elicited robust specific antibody and CTL responses against anti-HCC cells.38,39

In this study, we utilized the kinase inhibitor alisertib to enhance the therapeutic effect of the DNA vaccine pGPC3, effectively inhibiting the growth of subcutaneous liver cancer tumors while promoting the tumor infiltration of anti-tumor immune cells, particularly DCs and CD8+ T cells. Additionally, the combination therapy facilitated the induction and increased proportion of the CD8+CD11c+ DC subset and enhanced DC activation, while reducing the tumor infiltration of immunosuppressive Treg cells. The pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib significantly induced antigen-specific CD8+ T cell immune responses, skewing the immune response toward a Th1 phenotype. Although there was no significant difference in total IgG antibody levels among the four treatment groups in the tumor models, we did not assess the changes in IgG subclass levels, which may differ between the subclasses induced by tumor cell overexpression of the hGPC3 antigen and those induced by the vaccine. During the anti-tumor process, CD8+CD11c+ DCs act as key APCs that deliver antigens to CD8+ T cells, inducing antigen-specific CD8+ T cell immune responses to kill tumor cells.34 Alisertib treatment results in high expression of antigen-presentation genes in SCLC mouse models.43 Cell depletion experiments demonstrated that the therapeutic effect of the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib is primarily dependent on DC-mediated CD8+ T cells, rather than CD4+ T cells. However, CD4+ T cells enhance CD8+ T cell immune responses by providing cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-2, enhancing antigen presentation, providing co-stimulatory signals, promoting memory formation, and enhancing effector functions. This synergy plays a critical role in immune responses against tumors, enabling CD8+ T cells to exert maximum efficacy and provide long-lasting immune protection.44,45

IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2, in the combination treatment group, are critical for promoting CD8+ T cell activation, cytotoxicity, and memory T cell responses, aligning with the robust anti-tumor immunity and tumor growth inhibition observed in our study. In contrast, levels of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10, which are associated with anti-inflammatory responses and potential immune suppression, remained low across treatment groups. This skewing toward a Th1-dominated immune response suggests that the combination of the vaccine and alisertib effectively promotes a pro-inflammatory, tumor-suppressive environment. Notably, we observed a positive correlation between elevated IFN-γ levels and the frequency of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, further supporting the role of Th1 cytokines in driving tumor-specific immunity. Conversely, low levels of IL-10, which can inhibit DC maturation and T cell activation, may have contributed to the enhanced functionality of CD8+ T cells and DCs observed in the combination group.

To further verify whether the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib induces long-term anti-tumor immunity, we conducted a tumor rechallenge experiment in cured mice. The results showed that the combination therapy of pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib significantly inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival. To explore the underlying mechanisms further, we found that the combination therapy induced a strong memory CD8+ T cell response, suggesting that the CD8+ T cells induced by the combination therapy persisted as memory CD8+ T cells in the mice, ensuring long-term anti-tumor effects. As is well known, liver cancer primarily occurs in the liver. To simulate the clinical presence of liver cancer, we established an orthotopic liver tumor model and investigated the effects of the pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib. Similarly, the combination therapy significantly inhibited tumor growth and improved survival in the orthotopic liver tumor model. Whether this combination therapy can effectively alleviate liver tumor metastasis remains unclear, and future studies will further investigate its effects in a metastatic model. The pGPC3 vaccine combined with alisertib also induced a robust CD8+ T cell immune response in the orthotopic liver tumor model, providing strong therapeutic potential for treating liver tumors. However, we did not perform the combination therapy in a more advanced tumor setting, which could provide additional insights into its efficacy and translational potential. In future studies, we plan to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of this combination strategy in models where treatment begins at later stages, when tumors are larger and more established. Such experiments will help determine whether the combination therapy can overcome the heightened immunosuppression in advanced tumors while sustaining robust anti-tumor responses.

Alisertib is a selective inhibitor of aurora A kinase with potential immunomodulatory effects in anti-tumor immunity. Studies have shown that alisertib can enhance CD8+ T cell immune responses through various mechanisms, playing a critical role in anti-tumor immunity.46 Therefore, we reasonably hypothesized that alisertib increases the release of tumor antigens by inducing tumor cell apoptosis. These antigens are captured by DCs and can be cross-presented to CD8+ T cells via MHC class I molecules, further promoting CD8+ T cell activation and expansion. Immunosuppressive cell populations, such as Tregs, can inhibit the anti-tumor functions of CD8+ T cells within the tumor microenvironment.47 Alisertib has been shown to reduce the number or suppress the function of Tregs, thereby enhancing the anti-tumor activity of CD8+ T cells. Moreover, alisertib can alter the cellular composition and signaling pathways within the tumor microenvironment, promoting the production of pro-inflammatory signals.48 These signals attract more CD8+ T cells to the tumor site and enhance their anti-tumor activity. Alisertib may also induce immune cells, such as DCs or macrophages, to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines like IFN-γ and TNF-α.49,50 These cytokines can enhance the effector functions of CD8+ T cells and promote their infiltration into the tumor. Alisertib has been shown to induce PD-L1 expression involving its effects on the STING pathway in tumor cells, thereby attenuating its anti-tumor efficacy.51 Although alisertib is a more selective inhibitor of aurora kinase A, it can also inhibit aurora kinase B at higher doses.52 Aurora kinase B has been shown to phosphorylate cGAS,53 leading to the inhibition of the STING pathway and subsequent downregulation of PD-L1 expression. Thus, alisertib may activate the STING pathway by inhibiting aurora kinase B, resulting in PD-L1 upregulation. Future studies are needed to explore this potential mechanism and its contribution to the limited efficacy observed with alisertib monotherapy in our study.

Our findings indicate that the addition of the pGPC3 DNA vaccine effectively overcame this limitation by eliciting robust anti-tumor immune responses. The vaccine’s ability to promote CD8+ T cell infiltration and activity within the tumor microenvironment likely synergized with alisertib’s effects, resulting in the observed enhancement of anti-tumor immunity. The combination may have also mitigated the immune suppression induced by PD-L1 upregulation through the activation of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and the reduction of immunosuppressive cell populations, such as regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Although the exact mechanism by which alisertib enhances the CD8+ T cell immune response induced by the pGPC3 vaccine is not yet fully understood, future experiments are needed to elucidate these intricate mechanisms.

In conclusion, the combination therapy of the pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib effectively suppressed tumor growth in both subcutaneous and orthotopic liver cancer models. It enhanced immune cell infiltration, particularly by activating DCs, and strengthened tumor-specific CD8+ T cell responses. Moreover, the combination treatment induced long-lasting anti-tumor effects by promoting memory CD8+ T cell responses. This study highlights that alisertib significantly boosts the anti-tumor efficacy of the pGPC3 vaccine, primarily through enhancing DC-mediated CD8+ T cell immune responses, providing promising new strategies for the clinical management of HCC.

Limitations of the study

Although the study highlighted the enhanced anti-tumor efficacy of the combination therapy, the precise mechanisms by which alisertib modulates the immune microenvironment and synergizes with the pGPC3 vaccine remain insufficiently explored. Further investigation is required to elucidate the specific pathways and molecular interactions underpinning this therapeutic synergy. Additionally, the study relied primarily on murine HCC models, which, while valuable, may not fully capture the complexity and heterogeneity of human HCC. Differences between the murine and human immune systems further limit the translatability of the findings. The lack of validation in additional animal models or patient-derived xenograft models limits the immediate applicability of the results. Future research should focus on humanized models or early-phase clinical trials to assess the safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of this combination therapy in humans.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information or requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Fang Xue (0700036@bbmu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

No new unique reagents were developed in this study.

Data and code availability

-

•

The data supporting this study are available from the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This study does not include any original code.

-

•

Additional data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2208085MH248), Anhui Provincial Department of Education Fund (SK2019A0210), and the Science and technology project of Bengbu Medical College (2022byzd115sk).

Schematic diagram was created with BioRender.com.

Author contributions

F.X. and J.Z. were responsible for the study’s conception and design. F.X. and J.L. conducted the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, prepared figures, and drafted the manuscript. J.W., M.Z., S.T., and R.W. contributed to the tumor model study, while H.D. and R.W. assisted with in vitro experiments. N.Z., H.D., J.Z., S.T., and R.W. provided reagents, materials, and analytical tools. F.X. and J.Z. oversaw the study, provided supervision, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-human GPC3 | Nature Biosciences | Cat# A41348 |

| HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human GPC3 | Nature Biosciences | Cat# A12941 |

| HRP-conjugated horse anti-mouse IgG | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 7076; RRID:AB_330924 |

| Recombinant APC anti-human GPC3 | SinoBiological | Cat# 100393-R024-A; RRID:AB_2860068 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD45 | BioLegend | Cat# 103116; RRID:AB_312981 |

| PE anti-mouse CD3ε | BioLegend | Cat# 100308; RRID:AB_312673 |

| PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD4 | BioLegend | Cat# 116012; RRID:AB_2563023 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse CD8α | BioLegend | Cat# 100734; RRID:AB_2075238 |

| APC anti-mouse CD11c | BioLegend | Cat# 117310; RRID:AB_313779 |

| APC anti-mouse NK1.1 | BioLegend | Cat# 156506 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse FOXP3 | BioLegend | Cat# 118906 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD11b | BioLegend | Cat# 101206; RRID:AB_312789 |

| PerCP anti-mouse F4/80 | BioLegend | Cat# 123126; RRID:AB_893483 |

| PE anti-mouse CD80 | BioLegend | Cat# 104708; RRID:AB_313129 |

| PE anti-mouse CD86 | BioLegend | Cat# 159204; RRID:AB_2832568 |

| PE anti-mouse I-A/I-E | BioLegend | Cat# 107608; RRID:AB_313323 |

| PE anti-mouse H-2Kd/H-2Dd | BioLegend | Cat# 114708; RRID:AB_313607 |

| PE anti-mouse CD62L | BioLegend | Cat# 104408; RRID:AB_313095 |

| APC anti-mouse CD44 | BioLegend | Cat# 103012; RRID:AB_312963 |

| APC anti-mouse IFN-γ | BioLegend | Cat# 505810; RRID:AB_315404 |

| PE anti-mouse IL-2 | BioLegend | Cat# 503808; RRID:AB_315302 |

| FITC anti-mouse TNF-α | BioLegend | Cat# 506304; RRID:AB_315425 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro-hGPC3 | Stored in the lab | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Mouse tumor tissues | Stored in the lab | N/A |

| Chemicals and recombinant proteins | ||

| PLGA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P2066 |

| PEI | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 408727 |

| Alisertib | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-10971 |

| Human GPC3 | Stored in the lab | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Mouse IFN-γ ELISA Kit | Invitrogen | Cat# BMS606-2 |

| Mouse TNF-α ELISA Kit | Invitrogen | Cat# BMS607-3 |

| Mouse IL-10 ELISA Kit | Invitrogen | Cat# BMS614 |

| Mouse IL-4 ELISA Kit | Invitrogen | Cat# BMS613 |

| Mouse IFN-γ Single-Color ELISPOT kit | ImmunoSpot | Cat# SKU: mIFNgp-1M |

| ELISA bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Kit | Roche | Cat# 11647229001 |

| Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH) | Roche | Cat# 11644793001 |

| Mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-096-730 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HEK293T | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216 |

| Hepa1-6 | Beyotime | Cat# C7355 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6 mice; male | Experimental Animal Center at Bengbu Medical University | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pcDNA3.1-hGPC3 | Stored in the lab | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism version 9 | GraphPad | N/A |

| FlowJo software version 10.8.1 | FlowJo | N/A |

Experimental model and study participant details

Cell line and culture

Human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, and mouse liver cancer Hepa1-6 cell lines were purchased from Beyotime, China. Hepa1-6-hGPC3, a Hepa1-6 stable expressing human GPC3 (hGPC3) cell line, was generated using the recombinant lentivirus pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro-hGPC3. The lentivirus production was achieved by co-transfecting 293T cells with pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro-hGPC3 plasmid, along with psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmids. After 48 h, the virus-containing supernatant was harvested and used to infect Hepa1-6 cells. Infected cells were then treated with puromycin 24 h post-infection, leading to the generation of a stable Hep1-6-hGPC3 cell line after one-week selection. These cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA), which was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA). The cells were cultured continuously in a sterile environment at 37°C with 5% CO2 to ensure optimal growth conditions. These cell lines have undergone authentication and have been confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination.

Mice

C57BL/6 male mice, aged 6 to 8 weeks and of wild type, were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center at Bengbu Medical University, where they were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions. The mice lived on a 12-h light/dark cycle at a temperature range of 22–25°C and had unrestricted access to food and water. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council's guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and received approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Bengbu Medical University (No. 2023–478). Mice were used to establish subcutaneous or orthotopic HCC tumor model, and subsequently treated with pGPC3 vaccine and alisertib.

Method details

In vivo treatment

For plasmid preparation, the secreting signal peptide sequence (ATGGACAGTAAGGGCTCTTCTCAGAAGGGAAGCAGGCTGCTGCTGCTGCTGGTGGTGTCTAATCTGCTGCTGCCTCAGGGCGTGCTGGCT) linked to the N-terminus of full-length hpGPC3 was synthesized from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector using HindIII and XbaI. The plasmid pcDNA3.1-hGPC3 (pGPC3) was amplified in bacteria, followed by purification with the EndoFree Plasmid Kit (Qiagen, 12362). PLGA/PEI nanoparticle vaccines were prepared using the water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) double emulsion solvent evaporation process.38 To generate tumor models, mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) with 2 × 106 Hepa1-6-hGPC3 tumor cells in 100 μl on the right flank, and then randomly assigned to groups. Seven days post-tumor inoculation, each mouse was immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with 50 μg of the pGPC3 nanoparticle vaccine on days 7, 17, and 27, while alisertib (MedChemExpress, HY-10971) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a dose of 20 mg/kg for a total of six treatments on days 10, 14, 17, 21, 24 and 27. In the rechallenge experiment, naive mice and those cured by the combined therapy were re-injected subcutaneously with 2 × 106 Hepa1-6 cells, and tumor volumes were measured weekly. Tumor size was determined using the formula: V (mm3) = 0.5 × (Length × Width2).

For the orthotopic HCC tumor model, mice were anesthetized and performed orthotopic injection (o.i.) with 2 × 106 Hepa1-6-hGPC3 cells suspended in 20 μl of a solution containing 50% Matrigel directly into the left lobe of the liver. Afterward, the liver was repositioned, and the peritoneum and skin were sutured. Seven days post-injection, the mice were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with 50 μg of the pGPC3 nanoparticle vaccine on days 4, 14, and 24, and alisertib was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 20 mg/kg for three doses on days 7, 10, 14,17, 21 and 24. Mouse survival was monitored following the treatment.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

To measure GPC3 protein levels in cell supernatants or serum, ELISA 96-well plates (Corning, 9018) were coated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg/ml of anti-hGPC3 antibody (Nature Biosciences, A41348) and then blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the plates were incubated with the samples for 2 h. Following this, the plates were washed again and treated with HRP-conjugated anti-hGPC3 (Nature Biosciences, A12941) for 1 h at room temperature. The plate was developed and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

To assess the protein levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-4 in culture supernatants, splenocytes were plated in a 24-well culture dish at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml and stimulated with 10 μg/ml of hGPC3 protein that was purified from the HEK293 cell expression system at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment for 48 h. The culture supernatants or serum were then analyzed using an ELISA kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's guidelines.

To determine the IgG antibody titer, the plates were coated with 5 μg/ml of hGPC3 protein and incubated with mouse sera diluted in a tenfold series for 2 h. After the primary serum incubation, the plates were washed and treated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, 7076) antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were developed and stopped the reaction with 1 N hydrochloric acid and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

ELISPOT assay

The assay was conducted using the Mouse IFN-γ Single-Color ELISPOT kit following the manufacturer's protocol (ImmunoSpot, Cat# SKU: mIFNgp-1M). Splenocytes were isolated from the spleens of treated mice and seeded into an IFN-γ capture plate at 5 × 105 cells per well. They were then re-stimulated with human GPC3 protein (10 μg/ml) in 200 μl of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 100 U/ml IL-2. After 48 h of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the plates were washed and incubated with the IFN-γ detection antibody. The color development was achieved through enzyme-catalyzed substrate precipitation, and IFN-γ-expressing cells were analyzed using an ImmunoSpot S6 Ultimate Reader.

Lymphocyte proliferation assay

Splenocytes were harvested from treated mice and seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates. The cells were cultured in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/ml) and recombinant GPC3 protein (10 μg/ml), and the plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator for 5 days. On day 3, the culture medium was refreshed. Cell proliferation was measured using the ELISA bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Kit (Roche, 11647229001), following the manufacturer's colorimetric immunoassay protocol.

CTL assay

Lymphocytes isolated from the spleens of immunized mice were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 100 U/ml IL-2 and 10 μg/ml GPC3 protein, for 5 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Half of the medium was replaced on day 3. After the incubation period, the lymphocytes, serving as effector cells, were washed and resuspended in a fresh medium. The hGPC3-Hepa1-6) were used as target cells. Effector and target cells were co-cultured at a 50:1 ratio in U-bottom 96-well plates for 3 days. Cytotoxicity was assessed by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release in the supernatant using the Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Roche, 11644793001), following the manufacturer's protocol.

Flow cytometric analysis

Spleens were harvested and processed into a single-cell suspension, followed by filtration through a 70 μm nylon filter. Tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs) were isolated from tumor tissues using enzymatic digestion with the Mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-096-730). The resulting cell suspension was centrifuged at 300 × g at 4°C, and cell pellets were washed twice with PBS. Red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysis buffer. To prepare for staining, Fc receptors were blocked, and dead cells were excluded using the Zombie Aqua Fixable Viability Kit (BioLegend, 423102). Surface staining was performed with specific antibodies for 30 minutes at 4°C. For intracellular markers, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma Aldrich, 100496) and permeabilized using permeabilization buffer (BioLegend, 421002), followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with antibodies specific to intracellular proteins. The antibodies used included: Recombinant APC anti-human GPC3 (SinoBiological, 100393-R024-A), APC/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD45 (BioLegend, 103116), PE anti-mouse CD3ε (BioLegend, 100308), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD4 (BioLegend, 116012), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD8α (BioLegend, 100734), APC anti-mouse CD11c (BioLegend, 117310), APC anti-mouse NK1.1 (BioLegend, 156506), Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse FOXP3 (BioLegend, 118906), FITC anti-mouse CD11b (BioLegend, 101206), PerCP anti-mouse F4/80 (BioLegend, 123126), PE anti-mouse CD80 (BioLegend, 104708), PE anti-mouse CD86 (BioLegend, 159204), PE anti-mouse I-A/I-E (BioLegend, 107608), PE anti-mouse H-2Kd/H-2Dd (BioLegend, 114708), PE anti-mouse CD62L (BioLegend, 104408), APC anti-mouse CD44 (BioLegend, 103012), APC anti-mouse IFN-γ (BioLegend, 505810), FITC anti-mouse TNF-α (BioLegend, 506304), PE anti-mouse IL-2 (BioLegend, 503808). Isotype-matched control antibodies were included for appropriate comparison. Samples were analyzed on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer, and the data were processed using FlowJo V10.8.1 software.

CD4+ or CD8+ T cell depletion

To deplete CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, mice in the treatment group were injected with 500 μg of anti-mouse CD4 antibody (BioXcell, BE0119) or anti-mouse CD8α antibody (BioXcell, BE0061) two days before the first administration of the vaccine. Additional doses were administered on days 5 and 12 post-initial vaccination to ensure effective depletion throughout the treatment period. This approach allowed for the assessment of the role of CD8+ T cells in the anti-tumor immune response induced by the vaccine.

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5-μm-thick slides. HE staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the sections were assessed by a pathologist blinded to the treatment group. HE-stained slides were imaged using an Olympus IX73 microscope (Olympus).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Quantification and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 Software. Data, presented as mean ± SD, were analyzed using a two-tailed independent Student's t-test for comparisons between two groups or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparisons among multiple groups. Survival analysis was conducted using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Statistical significance levels were set as follows: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Published: March 15, 2025

Contributor Information

Fang Xue, Email: 0700036@bbmu.edu.cn.

Huan Duan, Email: duanhuan886@sina.com.

Rui Wang, Email: ruiwang1011@163.com.

Jing Zhang, Email: 0700007@bbmc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lin M.J., Svensson-Arvelund J., Lubitz G.S., Marabelle A., Melero I., Brown B.D., Brody J.D. Cancer vaccines: the next immunotherapy frontier. Nat. Cancer. 2022;3:911–926. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saxena M., van der Burg S.H., Melief C.J.M., Bhardwaj N. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021;21:360–378. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baharom F., Ramirez-Valdez R.A., Khalilnezhad A., Khalilnezhad S., Dillon M., Hermans D., Fussell S., Tobin K.K.S., Dutertre C.A., Lynn G.M., et al. Systemic vaccination induces CD8(+) T cells and remodels the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2022;185:4317–4332.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopes A., Bastiancich C., Bausart M., Ligot S., Lambricht L., Vanvarenberg K., Ucakar B., Gallez B., Préat V., Vandermeulen G. New generation of DNA-based immunotherapy induces a potent immune response and increases the survival in different tumor models. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2021;9 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Burg S.H., Arens R., Ossendorp F., van Hall T., Melief C.J.M. Vaccines for established cancer: overcoming the challenges posed by immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:219–233. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhatchinamoorthy K., Colbert J.D., Rock K.L. Cancer Immune Evasion Through Loss of MHC Class I Antigen Presentation. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.636568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan T., Zhang M., Yang J., Zhu Z., Cao W., Dong C. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: advancements, challenges, and prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023;8:450. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritah H., Rovelli R., Chiang C.L.L., Kandalaft L.E. The current clinical landscape of personalized cancer vaccines. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;106 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu L., Sun M., Zhang Q., Zhou Q., Wang Y. Harnessing the immune system by targeting immune checkpoints: Providing new hope for Oncotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.982026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neeli P., Maza P.A.M.A., Chai D., Zhao D., Hoi X.P., Chan K.S., Young K.H., Li Y. DNA vaccines against GPRC5D synergize with PD-1 blockade to treat multiple myeloma. NPJ Vaccines. 2024;9:180. doi: 10.1038/s41541-024-00979-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salvatori E., Lione L., Compagnone M., Pinto E., Conforti A., Ciliberto G., Aurisicchio L., Palombo F. Neoantigen cancer vaccine augments anti-CTLA-4 efficacy. NPJ Vaccines. 2022;7:15. doi: 10.1038/s41541-022-00433-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liewer S., Huddleston A. Alisertib: a review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and toxicity in patients with hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2018;27:105–112. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2018.1417382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marumoto T., Hirota T., Morisaki T., Kunitoku N., Zhang D., Ichikawa Y., Sasayama T., Kuninaka S., Mimori T., Tamaki N., et al. Roles of aurora-A kinase in mitotic entry and G2 checkpoint in mammalian cells. Genes Cells. 2002;7:1173–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikonova A.S., Astsaturov I., Serebriiskii I.G., Dunbrack R.L., Jr., Golemis E.A. Aurora A kinase (AURKA) in normal and pathological cell division. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70:661–687. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin X., Xiang X., Hao L., Wang T., Lai Y., Abudoureyimu M., Zhou H., Feng B., Chu X., Wang R. The role of Aurora-A in human cancers and future therapeutics. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020;10:2705–2729. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malumbres M., Pérez de Castro I. Aurora kinase A inhibitors: promising agents in antitumoral therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2014;18:1377–1393. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.956085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding Y.H., Zhou Z.W., Ha C.F., Zhang X.Y., Pan S.T., He Z.X., Edelman J.L., Wang D., Yang Y.X., Zhang X., et al. Alisertib, an Aurora kinase A inhibitor, induces apoptosis and autophagy but inhibits epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015;9:425–464. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S74062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J.P., Yang Y.X., Liu Q.L., Pan S.T., He Z.X., Zhang X., Yang T., Chen X.W., Wang D., Qiu J.X., Zhou S.F. The investigational Aurora kinase A inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237) induces cell cycle G2/M arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy via p38 MAPK and Akt/mTOR signaling pathways in human breast cancer cells. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015;9:1627–1652. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S75378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Pitts T.M., Bradshaw-Pierce E.L., Bagby S.M., Hyatt S.L., Selby H.M., Spreafico A., Tentler J.J., McPhillips K., Klauck P.J., Capasso A., et al. Antitumor activity of the aurora a selective kinase inhibitor, alisertib, against preclinical models of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:50290–50301. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Q., Yu X., Zhou Z.W., Zhou C., Chen X.W., Zhou S.F. Inhibition of Aurora A Kinase by Alisertib Induces Autophagy and Cell Cycle Arrest and Increases Chemosensitivity in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2017;17:386–401. doi: 10.2174/1568009616666160630182344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tayyar Y., Idris A., Vidimce J., Ferreira D.A., McMillan N.A. Alpelisib and radiotherapy treatment enhances Alisertib-mediated cervical cancer tumor killing. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021;11:3240–3251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connor O.A., Özcan M., Jacobsen E.D., Roncero J.M., Trotman J., Demeter J., Masszi T., Pereira J., Ramchandren R., Beaven A., et al. Randomized Phase III Study of Alisertib or Investigator's Choice (Selected Single Agent) in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:613–623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melichar B., Adenis A., Lockhart A.C., Bennouna J., Dees E.C., Kayaleh O., Obermannova R., DeMichele A., Zatloukal P., Zhang B., et al. Safety and activity of alisertib, an investigational aurora kinase A inhibitor, in patients with breast cancer, small-cell lung cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer, head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma, and gastro-oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a five-arm phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:395–405. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis S.L., Ionkina A.A., Bagby S.M., Orth J.D., Gittleman B., Marcus J.M., Lam E.T., Corr B.R., O'Bryant C.L., Glode A.E., et al. Preclinical and Dose-Finding Phase I Trial Results of Combined Treatment with a TORC1/2 Inhibitor (TAK-228) and Aurora A Kinase Inhibitor (Alisertib) in Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:4633–4642. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin T., Zhao Z.B., Guo J., Wang T., Yang J.B., Wang C., Long J., Ma S., Huang Q., Zhang K., et al. Aurora A Inhibition Eliminates Myeloid Cell-Mediated Immunosuppression and Enhances the Efficacy of Anti-PD-L1 Therapy in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:3431–3444. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X., Liu X., Du S. Unveiling the Role of Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells and Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers. 2023;15 doi: 10.3390/cancers15205046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogel A., Finn R.S., Blanchet Zumofen M.H., Heuser C., Alvarez J.S., Leibfried M., Mitchell C.R., Batson S., Redhead G., Gaillard V.E., Kudo M. Atezolizumab in Combination with Bevacizumab for the Management of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the First-Line Setting: Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Liver Cancer. 2023;12:510–520. doi: 10.1159/000533166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hao L., Li S., Ye F., Wang H., Zhong Y., Zhang X., Hu X., Huang X. The current status and future of targeted-immune combination for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1418965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y., Dai S., Cheng C.S., Chen L. Lenvatinib and immune-checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanistic insights, clinical efficacy, and future perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024;17:130. doi: 10.1186/s13045-024-01647-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granito A., Marinelli S., Forgione A., Renzulli M., Benevento F., Piscaglia F., Tovoli F. Regorafenib Combined with Other Systemic Therapies: Exploring Promising Therapeutic Combinations in HCC. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma. 2021;8:477–492. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S251729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung V., Kos F.J., Hardwick N., Yuan Y., Chao J., Li D., Waisman J., Li M., Zurcher K., Frankel P., Diamond D.J. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of p53MVA vaccine combined with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid cancers. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2019;21:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s12094-018-1932-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carloni R., Sabbioni S., Rizzo A., Ricci A.D., Palloni A., Petrarota C., Cusmai A., Tavolari S., Gadaleta-Caldarola G., Brandi G. Immune-Based Combination Therapies for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma. 2023;10:1445–1463. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S390963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J., Fu M., Wang M., Wan D., Wei Y., Wei X. Cancer vaccines as promising immuno-therapeutics: platforms and current progress. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022;15:28. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding J., Jiang N., Zheng Y., Wang J., Fang L., Li H., Yang J., Hu A., Xiao P., Zhang Q., et al. Adenovirus vaccine therapy with CD137L promotes CD8(+) DCs-mediated multifunctional CD8(+) T cell immunity and elicits potent anti-tumor activity. Pharmacol. Res. 2022;175 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.106034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Y., Liu H., Ding H. GPC-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: current perspectives. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma. 2016;3:63–67. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S116513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu Y., Urban D.J., Nani R.R., Zhang Y.F., Li N., Fu H., Shah H., Gorka A.P., Guha R., Chen L., et al. Glypican-3-Specific Antibody Drug Conjugates Targeting Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 2019;70:563–576. doi: 10.1002/hep.30326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Z., Jiang X., Chen S., Lai Y., Wei X., Li B., Lin S., Wang S., Wu Q., Liang Q., et al. Anti-GPC3-CAR T Cells Suppress the Growth of Tumor Cells in Patient-Derived Xenografts of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:690. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi X., Ding J., Zheng Y., Wang J., Sobhani N., Neeli P., Wang G., Zheng J., Chai D. HMGB1/GPC3 dual targeting vaccine induces dendritic cells-mediated CD8(+)T cell immune response and elicits potential therapeutic effect in hepatocellular carcinoma. iScience. 2023;26 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Q., Pi L., Le Trinh T., Zuo C., Xia M., Jiao Y., Hou Z., Jo S., Puszyk W., Pham K., et al. A Novel Vaccine Targeting Glypican-3 as a Treatment for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:2299–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu B., Lim J.M., Yu B., Song S., Neeli P., Sobhani N., K P., Bonam S.R., Kurapati R., Zheng J., Chai D. The next-generation DNA vaccine platforms and delivery systems: advances, challenges and prospects. Front. Immunol. 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1332939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawada Y., Yoshikawa T., Ofuji K., Yoshimura M., Tsuchiya N., Takahashi M., Nobuoka D., Gotohda N., Takahashi S., Kato Y., et al. Phase II study of the GPC3-derived peptide vaccine as an adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. OncoImmunology. 2016;5 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1129483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuchiya N., Yoshikawa T., Fujinami N., Saito K., Mizuno S., Sawada Y., Endo I., Nakatsura T. Immunological efficacy of glypican-3 peptide vaccine in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. OncoImmunology. 2017;6 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1346764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y., Mahadevan N.R., Duplaquet L., Hong D., Durmaz Y.T., Jones K.L., Cho H., Morrow M., Protti A., Poitras M.J., et al. Aurora A kinase inhibition induces accumulation of SCLC tumor cells in mitosis with restored interferon signaling to increase response to PD-L1. Cell Rep. Med. 2023;4 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laidlaw B.J., Craft J.E., Kaech S.M. The multifaceted role of CD4(+) T cells in CD8(+) T cell memory. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:102–111. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montauti E., Oh D.Y., Fong L. CD4(+) T cells in antitumor immunity. Trends Cancer. 2024;10:969–985. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2024.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han J., Jiang Z., Wang C., Chen X., Li R., Sun N., Liu X., Wang H., Hong L., Zheng K., et al. Inhibition of Aurora-A Promotes CD8(+) T-Cell Infiltration by Mediating IL10 Production in Cancer Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020;18:1589–1602. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li C., Jiang P., Wei S., Xu X., Wang J. Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: new mechanisms, potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19:116. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01234-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choy L., Norris S., Wu X., Kolumam G., Firestone A., Settleman J., Stokoe D. Inhibition of Aurora Kinase Induces Endogenous Retroelements to Induce a Type I/III IFN Response via RIG-I. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024;4:540–555. doi: 10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-23-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yin Y., Kong D., He K., Xia Q. Aurora kinase A regulates liver regeneration through macrophages polarization and Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Liver Int. 2022;42:468–478. doi: 10.1111/liv.15094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varshney N., Pandey R.K., Mishra A., Kumar S., Jha H.C. Aurora Kinase A: Integrating Insights into Cancer. Gut Microbes Rep. 2024;1:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X., Huang J., Liu F., Yu Q., Wang R., Wang J., Zhu Z., Yu J., Hou J., Shim J.S., et al. Aurora A kinase inhibition compromises its antitumor efficacy by elevating PD-L1 expression. J. Clin. Investig. 2023;133 doi: 10.1172/JCI161929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin D., Fallaha S., Proctor M., Stevenson A., Perrin L., McMillan N., Gabrielli B. Inhibition of Aurora A and Aurora B Is Required for the Sensitivity of HPV-Driven Cervical Cancers to Aurora Kinase Inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017;16:1934–1941. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li T., Huang T., Du M., Chen X., Du F., Ren J., Chen Z.J. Phosphorylation and chromatin tethering prevent cGAS activation during mitosis. Science. 2021;371 doi: 10.1126/science.abc5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

-

•

The data supporting this study are available from the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This study does not include any original code.

-

•

Additional data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from the lead contact upon request.