Abstract

Benzodiazepines, widely prescribed psychoactive drugs, may contain DNA-reactive (mutagenic) impurities formed during synthesis, posing significant health risks. Owing to animal testing requirements, traditional in vitro and in vivo methods for assessing mutagenicity are time-consuming, costly, and ethically challenging. Computational approaches, particularly in silico (Q)SAR models, provide an efficient alternative for predicting toxicity based on chemical structure. This study evaluated the mutagenic potential of 88 benzodiazepine-related impurities using three freely accessible (Q)SAR tools: TOXTREE (Ames Test Alert by ISS), Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (TEST) with nearest neighbour and consensus models, and VEGA, a QSAR tool that integrates multiple mutagenicity prediction models, including the CAESAR Ames Mutagenicity Model. The tools were validated using a dataset of 99 chemicals with known Ames test results. TOXTREE exhibited the highest sensitivity (80.7 %) and accuracy (72.2 %) for predicting mutagenicity, whereas VEGA and TEST provided balanced accuracy (66.2 % and 66.7 %, respectively) and high specificity (74.5 % and 76.6 %, respectively). The risk assessment categorised 21 impurities as high risk, 11 as moderate-high risk, 28 as moderate-low risk, 22 as low risk, and 6 as equivocal, with expert review finalising classifications. The findings emphasise the integration of multiple (Q)SAR tools for early mutagenicity detection, regulatory compliance, and reduced reliance on animal testing. Further refinement of predictive models and additional computational approaches are recommended to enhance the accuracy of the risk assessment.

Keywords: Benzodiazepines, Mutagenic impurities, In silico evaluation, (Q)SAR tools, Regulatory implications

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Evaluated 88 benzodiazepine impurities using TOXTREE, TEST, and VEGA tools.

-

•

Validated QSAR tools with Ames test data for accuracy and reliability.

-

•

TOXTREE showed the highest sensitivity (80.7 %) and accuracy (72.2 %) in predictions.

-

•

21 impurities were classified as high risk, with a final expert-reviewed classification.

-

•

Aligned genotoxic impurity assessment with ICH M7 regulatory guidelines.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Benzodiazepines are psychoactive drugs that act on the central nervous system (CNS) by modulating the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmitter system, providing anxiolytic, hypnotic, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant properties [1], [2], [3], [4]. Despite their widespread therapeutic use, benzodiazepine-active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) may contain mutagenic impurities formed during synthesis, degradation, or contamination from raw materials, intermediates, and reagents [5], [6]. Given the potential health risks associated with DNA-reactive impurities, regulatory agencies have emphasised their identification and control.

Benzodiazepine impurities often lack sufficient mutagenicity data. To address this gap, computational methods, such as quantitative structure-activity relationship ((Q)SAR) models, have become valuable tools for assessing mutagenic potential. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M7 guidelines recommend using in silico (Q)SAR methodologies to predict bacterial mutagenicity, mainly through Ames test-based models [7], [8], [9]. This guideline advocates employing two complementary computational approaches–an expert rule-based system and a statistical-based model–to enhance the reliability of mutagenicity risk assessments.

The predictive accuracy of in silico models depends on the availability of the representative chemical datasets. To enhance model performance, the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA) compiled Ames test data from eight pharmaceutical companies covering 99 chemicals used in drug manufacturing.

These data were analysed using Derek Nexus (a knowledge-based model) and CASE Ultra (a statistical-based model) to refine in silico predictions and improve our understanding of mutagenesis mechanisms through structure-activity relationship (SAR) models [10].

Advancements in Ames mutagenicity prediction have extended beyond the JPMA initiative. The AMES/QSAR International Collaborative Study, launched in 2014 by Japan's National Institute of Health Sciences (DGM/NIHS), has been instrumental in improving the reliability of (Q)SAR models by integrating high-quality experimental data and optimising QSAR algorithms for greater predictive accuracy [34]. This initiative involved 12 international participants, including the USA, the UK, Italy, Spain, Bulgaria, Sweden, and Japan. It was conducted in three phases to evaluate whether expanding the knowledge base enhances the QSAR model performance.

This study provided QSAR model developers with Ames test data for approximately 12,000 new chemical compounds, enabling improved Ames mutagenicity predictions. The key objectives included harmonising mutagenicity predictions across computational models, validating model outputs with large-scale Ames test datasets, and addressing discrepancies in predictive performance. These efforts have significantly enhanced the sensitivity and specificity of in silico models, ensuring a better alignment with experimental outcomes.

Integrating the JPMA dataset into predictive frameworks aligns with the broader advancements in Ames prediction methodologies. By combining rule-based, statistical, and machine learning approaches, recent efforts have expanded the applicability domain of in silico models, reduced false-positive and false-negative rates, and strengthened the regulatory acceptance of computational toxicology tools. Future research should continue to refine and expand the chemical datasets, particularly for pharmaceutical impurities, to improve the robustness and predictive reliability of QSAR-based mutagenicity assessments.

In this study, we employed three freely accessible (Q)SAR tools: TOXTREE (https://toxtree.sourceforge.net/), a rule-based model (Ames Test Alert by ISS); TEST (https://www.epa.gov/comptox-tools/toxicity-estimation-software-tool-test/), a statistical-based model with nearest-neighbour and consensus approaches; and VEGA (https://www.vegahub.eu/portfolio-types/in-silico-tools/), a software platform that integrates multiple QSAR models to predict the mutagenicity of 88 benzodiazepine-related impurities. These computational tools offer non-animal, cost-effective, and regulatory-compliant alternatives for early mutagenicity screening [11], [12], [13]. Our findings will contribute to impurity profiling, support regulatory compliance, and reduce reliance on conventional in vitro and in vivo testing.

1.2. Structural alert

Structural alerts are the molecular features associated with toxicological endpoints, including mutagenicity. These alerts are critical indicators of potential genotoxicity and are widely used in pharmaceutical impurity assessments. Medicinal chemists and toxicologists use structural alerts to guide the design of safer molecules, reduce toxicity risks, and comply with regulatory frameworks, such as ICH M7. Identifying these alerts is particularly crucial for assessing the mutagenic potential of benzodiazepine-related impurities, as recommended by regulatory agencies.

1.2.1. Key structural classes and their mutagenic potential

Based on the Ames test results of the 99-substance dataset, several structural classes were identified as frequently associated with mutagenicity, including compounds relevant to benzodiazepine synthesis and degradation pathways.

Nitroaromatic compounds such as 1-iodo-4-nitrobenzene and methyl 2-methyl-3-nitrobenzoate exhibit strong mutagenic responses. The presence of a nitro group (-NO₂) is a well-known structural alert for mutagenicity because of its metabolic reduction to reactive nitroso and hydroxylamine intermediates, which can form DNA adducts and induce genetic mutations [39], [40]. Similarly, aromatic amines, including 4-amino-2-fluorophenol and methyl 3-amino-2-methyl benzoate, yielded positive Ames test results. These compounds undergo metabolic activation via cytochrome P450 enzymes, forming highly reactive N-hydroxy intermediates that contribute to DNA alkylation and potential carcinogenic effects [41], [42], [43], [44]. These findings are particularly relevant for benzodiazepine-derived impurities, because specific synthetic routes involve aromatic amines and nitro-functionalised intermediates.

Thiazole derivatives are another class of mutagenic compounds identified in the datasets. Some thiazole-based chemicals, such as 4-hexyl-1,3-thiazol-2-amine, exhibit mutagenic effects, possibly because of the electrophilic nature of their metabolic intermediates, which can interact with nucleophilic sites in DNA [45], leading to genotoxicity. Several halogenated compounds, including 1-bromohexane and 2-chloro-N-methoxy-N-methylacetamide, tested positive for mutagenic potential. The presence of halogen substituents, particularly bromine and chlorine, increases the electrophilicity of a molecule, enhancing its reactivity with DNA nucleophiles, and contributing to its mutagenic potential [46], [47], [48]. Some halogenated benzodiazepine-related impurities may also fall within this category, warranting further in silico and experimental evaluation.

Epoxides and quinolinones have also been identified as mutagenic classes. Epoxides such as 6-(2,3-epoxypropoxy)-2(1H)-quinolinone are highly reactive because of their strained three-membered ring structure. These compounds readily form covalent adducts with DNA [49], [50], [51], a mechanism that is strongly linked to Ames-positive results. Similarly, quinolinone derivatives exhibit mutagenicity through various pathways, including metabolic activation and DNA intercalation. Some benzodiazepine degradation products may form epoxide intermediates, increasing their mutagenic potential and regulatory concerns.

These structural alerts are crucial for predicting genotoxic potential and are vital for pharmaceutical impurity profiling, risk assessment, and regulatory decision-making. The presence of these alerts in benzodiazepine-related impurities further reinforces the need for robust in silico evaluations and expert reviews to ensure compliance with regulatory guidelines and to minimise mutagenic risks.

1.3. Regulatory framework for genotoxic impurities in pharmaceuticals

Regulatory authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [14]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and ICH have established guidelines for identifying and controlling mutagenic pharmaceutical impurities. FDA guidelines provide a comprehensive framework for assessing and managing DNA-reactive impurities to mitigate mutagenic risks. The FDA and EMA have set impurity limits and risk assessment strategies to ensure patient safety and regulatory compliance. These regulations align with the ICH M7 framework, which emphasises evaluating and controlling mutagenic impurities to reduce the risk of genetic mutations caused by pharmaceutical products.

1.4. Role of in silico tools in mutagenic risk assessment

(Q)SAR tools are crucial for assessing the mutagenic potential of chemical impurities. These computational models analyse structural features to predict toxicity, aiding impurity risk assessments. Understanding and minimising the genotoxic risks of benzodiazepines is essential, given the stringent regulatory environment. Danieli et al. [15] demonstrated that VEGA improves the confidence of (Q)SAR predictions by evaluating the applicability domain (AD), which is a critical factor in assessing the QSAR model reliability. In silico tools complement the traditional testing methods by offering cost-effective and rapid toxicity screening. Their integration into impurity profiling enhances regulatory compliance while reducing reliance on experimental mutagenic assays.

1.5. Literature reported validation and performance of (Q)SAR models

Validation is crucial for establishing the reliability of (Q)SAR tools for toxicity prediction. Cassano et al., [16] evaluated multiple freely available (Q)SAR tools for Ames genotoxicity. The Benigni/Bossa rule base [17] on the VEGA platform demonstrated the highest accuracy (92 %) and specificity (93 %). Contrera [18] validated SciQSAR and ToxTree using the Hansen benchmark dataset of 6489 non-proprietary compounds, highlighting specificity, sensitivity, and concordance values of 66 %, 80 %, and 74 %, respectively.

Melnikov et al., [19] found that TEST's consensus model provided the most reliable mutagenicity estimates. Priyanka et al. [20] reviewed the (Q)SAR model reliability, emphasising the dataset quality, descriptor selection, and validation techniques. They highlighted methods like double cross-validation and intelligent consensus predictors to improve prediction accuracy.

OECD [21], [22] provides a structured framework to evaluate the regulatory applicability of (Q)SAR tools. Our study validated three (Q)SAR tools using the Ames test data from 99 pharmaceutical compounds. According to a study by Hakura et al., [10] Derek Nexus and CASE Ultra demonstrated accuracy rates of 70 % and 57 %, respectively. Notably, no previous study has specifically assessed the mutagenicity of benzodiazepine API impurities by using (Q)SAR models.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. (Q) SAR tools, validation, and application data set used

This study focused on predicting mutagenicity (Ames Test Prediction) using three (Q)SAR tools aligned with the ICH M7 guidelines.

2.1.1. TOXTREE (v3.1.0.1851): Ames test alert by ISS for bacterial mutagenicity

.

2.1.2. TEST (v5.1.2, USEPA): Nearest neighbour and consensus models explicitly designed for mutagenicity assessment

.

2.1.3. VEGA (v1.2.3): CAESAR Ames mutagenicity model for evaluating bacterial mutagenicity

We used TOXTREE, TEST (USEPA), and VEGA, freely accessible QSAR tools that ensure transparency, reproducibility, and regulatory compliance with ICH M7 guidelines. Unlike proprietary software, which requires paid licences, these tools allow for independent verification of the results. Our selection was based on regulatory acceptance, literature support, and practical accessibility, making them suitable for cost-effective mutagenicity assessments. Furthermore, we validated our models using a dataset of 99 Ames test compounds, confirming their reliability without relying on commercial software.

A curated dataset containing experimentally verified Ames test results for 99 chemicals was used to assess the predictive accuracy of the (Q)SAR tools. For practical applications, 88 benzodiazepine-related impurities were analysed using the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) names obtained from official pharmacopoeias, including the United States Pharmacopoeia [23], Indian Pharmacopoeia [24], and European Pharmacopoeia [25].

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Systematic literature search

We compiled detailed structural data on mutagenic impurities found in benzodiazepines through a comprehensive literature review. We searched databases such as Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and pharmaceutical monographs, including USP, IP, and Ph. Eur. The search used terms like "benzodiazepines," "benzodiazepine-related impurities," "Mutagenic impurities," "sources of mutagenic impurities," and "regulatory implications." We included peer-reviewed journals, review papers, and regulatory guidelines like those of the ICH and USFDA. We excluded studies focusing on unrelated impurities, non-peer-reviewed sources, or conference abstracts. After obtaining and assessing the full texts of potentially relevant publications, we screened and reviewed the titles and abstracts of the appropriate research and review articles for inclusion.

2.2.2. Risk categorisation approach

The risk assessment of impurities follows a structured approach based on their mutagenic potential, in alignment with ICH M7 guidelines. Impurities are categorized using the consensus predictions of TOXTREE, T.E.S.T, and VEGA in silico tools. While QSAR predictions provide valuable insights, they alone are not always sufficient for regulatory classification, particularly for high-risk impurities.

2.2.3. ICH M7 classification

ICH M7 classifies impurities into five categories based on their mutagenicity and carcinogenicity potential.

2.2.3.1. Class 1: known mutagenic carcinogens

Class 1 impurities are those that are both mutagenic and carcinogenic. These impurities have tested positive in the Ames test and have evidence of carcinogenicity in long-term studies. Due to their confirmed risk, these impurities require the strictest control measures, and their acceptable limits must be established based on the Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC).

2.2.3.2. Class 2: known or predicted mutagenic impurities

Class 2 impurities are those that have been identified as mutagenic based on Ames-positive results or strong evidence from QSAR predictions when Ames data is unavailable. According to ICH M7, impurities in this category require strict control and monitoring to minimize potential carcinogenic risks. If Ames test data is not available, a weight-of-evidence approach, including structural alerts and QSAR predictions, can be used for an initial risk assessment, with experimental testing recommended as needed.

2.2.3.3. Class 3: structural alerts without experimental mutagenicity data

Class 3 impurities contain structural alerts for mutagenicity but lack Ames or in vivo mutagenicity data. According to ICH M7, these impurities are considered potentially mutagenic until further evidence is available. While an Ames test is recommended to confirm their mutagenicity, it is not mandatory if sufficient weight-of-evidence suggests a low risk. If an Ames test confirms mutagenicity, the impurity is reclassified as Class 2 and requires strict control. If the Ames test is negative, the impurity may be reclassified as Class 4 or Class 5, depending on additional supporting data.

2.2.3.4. Class 4: no structural alerts & negative Ames data

Class 4 impurities lack structural alerts and have been shown to be non-mutagenic based on negative Ames test results. ICH M7 states that negative Ames test data alone can be sufficient for classification as Class 4—additional in vivo data is not always required. These impurities are considered non-mutagenic and do not require additional regulatory control unless new data suggests otherwise.

2.2.3.5. Class 5: no structural alerts & no evidence of mutagenicity

Class 5 impurities lack structural alerts and show no evidence of mutagenicity in any available data. These impurities are not considered a concern for mutagenicity and do not require further regulatory action. However, if new data suggests a structurally similar analogue with known mutagenicity concerns, additional evaluation may be necessary.

2.2.4. Application to benzodiazepine-related impurities

In the context of benzodiazepine-related impurities, classification was conducted following ICH M7 principles to ensure a structured and regulatory-compliant assessment. Class 2 impurities include those that are Ames-positive or strongly predicted to be mutagenic by QSAR tools when Ames data is unavailable. These impurities require strict control and monitoring based on the Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC) to mitigate potential risks. Class 3 impurities contain structural alerts for mutagenicity but lack Ames test data, necessitating further Ames testing to confirm or refute their mutagenicity before regulatory classification. Class 4 impurities, which lack structural alerts and have negative Ames test results, are considered non-mutagenic and do not require additional regulatory control. Lastly, Class 5 impurities also lack structural alerts and have no evidence of mutagenicity, meaning they are not subject to regulatory action unless new data emerges. This structured classification approach ensures compliance with ICH M7 guidelines by integrating QSAR predictions, expert judgment, and experimental validation, leading to a comprehensive and risk-based evaluation of pharmaceutical impurities.

3. Experimental

3.1. In-silico assessment of impurities for bacterial mutagenicity

Impurities were evaluated for bacterial mutagenicity (Ames test) following ICH M7 guidelines, which recommend using at least two complementary (Q)SAR methodologies: an expert rule-based and a statistical-based model [14]. The selected tools described in Section 2.1 provided complementary predictive approaches to assess potential mutagenicity.

Predictions were generated for each impurity, and VEGA's applicability domain assessment was considered to determine whether the predictions fell within a valid chemical space [27]. When discrepancies arose between model predictions, an expert review was conducted to resolve inconsistencies, considering structural alerts, model confidence scores, and applicability domain limitations [26], [27]. This approach ensures robust assessment while minimising false positives and false negatives.

3.1.1. Comparison with previous Ames QSAR studies

Previous QSAR-based Ames test evaluations primarily relied on single-model approaches, such as DEREK Nexus (knowledge-based rule model) and CASE Ultra (statistics-based model), to predict mutagenicity [10]. Although these tools have been widely used in regulatory toxicology, their predictive accuracy varies depending on the chemical dataset used for evaluation.

A study analysing 99 pharmaceutical-related chemicals found that DEREK Nexus exhibited a sensitivity of 65 % (15/23), a specificity of 71 % (47/66), and an overall accuracy of 70 % (62/89). Meanwhile, CASE Ultra had a lower sensitivity of 50 % (6/12), a specificity of 60 % (25/42), and an accuracy of 57 % (31/54) [10]. The disagreement ratio between CASE Ultra "known" positives/negatives and actual Ames test results was 11 % (4/35), indicating inconsistent prediction reliability.

Our study improves upon these previous QSAR-based Ames evaluations by employing a structured multi-tool framework integrating rule-based (TOXTREE), statistical (TEST), and hybrid (VEGA) tool. Unlike previous assessments that relied on one QSAR methodology, our multi-model approach aligns with ICH M7 recommendations by ensuring cross-verification between different prediction methodologies, thereby reducing the likelihood of false-positive and false-negative results. Additionally, including VEGA's applicability domain assessment helps to identify predictions outside the model's training set, further enhancing reliability.

3.2. Selection of QSAR tools

Freely available QSAR tools were selected based on their predictive capabilities to provide a comprehensive and cost-effective assessment. ToxTree identifies structural alerts for mutagenicity using the Benigni/Bossa rule set, offering expert rule-based predictions. T.E.S.T. applies statistical-based modelling to predict mutagenicity through quantitative structure-activity relationships. VEGA is a QSAR tool that contains multiple predictive models. In this study, we used only the CAESAR Ames test model within VEGA for mutagenicity assessment.

3.2.1. Data collection and input preparation

We collected structural data and chemical identifiers, including International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) names, Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) notations, and Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) numbers, from literature sources, such as research articles and pharmacopoeias, including USP, EP, and IP. These data were analysed using three (Q)SAR tools. The TOXTREE tool with the model Ames Test Alert by ISS for bacterial mutagenicity evaluates the mutagenic structural alerts of benzodiazepine API-related impurities. The TEST (USEPA) consensus prediction model, nearest neighbour method, and VEGA tool was used to generate in silico mutagenicity predictions using its CAESAR Ames test model.

We selected TOXTREE, the Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (TEST), and the VEGA platform for their complementary strengths in predicting bacterial mutagenicity and adherence to OECD validation guidelines for (Q) SAR tools.

3.2.2. TOXTREE analysis

TOXTREE uses an expert rule-based methodology to predict toxic hazards using a decision-tree approach. This tool was used as an initial screening method to identify structural alerts that could indicate in vitro mutagenicity (Ames test) alerts by ISS, which categorises chemical structures into mutagenic and non-mutagenic classes based on predefined decision trees. However, TOXTREE provides a preliminary identification of potential mutagenic hazards.

3.2.3. TEST analysis

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) developed TEST software, which uses (Q) SAR tools to provide more precise probabilistic estimations of mutagenicity.

This study used the TEST tool to refine the initial predictions from TOXTREE by incorporating quantitative dimensions into the analysis. The nearest neighbour and consensus models within TEST were selected to predict mutagenicity, providing a data-driven approach to enhance the accuracy of the predictions.

3.2.4. VEGA-(Q)SAR model analysis

The VEGA platform, developed by the Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, was integrated into the assessment to enhance the validation of findings from TOXTREE and T.E.S.T. It employs multiple (Q)SAR models and uses quantitative measurements to evaluate the applicability domain (AD), considering factors such as chemical similarity, endpoint-specific criteria, and algorithm reliability.

This study systematically analysed the VEGA AD index for each impurity to determine whether predictions fell within the chemically relevant space of the model's training set. Predictions of compounds within the applicability domain (high AD index values) were considered reliable and directly interpreted. However, the predictions were flagged for expert review of compounds outside the applicability domain (low AD index values) to ensure scientific validity.

For out-of-domain compounds, additional steps were taken, including cross-checking with alternative QSAR tools (TOXTREE and TEST) to verify consistency, examining similarity indices to assess the structural relevance to the training set, and evaluating structural alerts to determine the mechanistic plausibility of the predicted mutagenicity. Confidence levels were adjusted based on the applicability domain status, with lower confidence assigned to out-of-domain compounds to ensure cautious regulatory decision making.

This structured approach ensured that computational assessments were scientifically sound, reducing the likelihood of false-positive or false-negative classifications, and improving the overall reliability of QSAR-based mutagenicity predictions. By integrating applicability domain considerations, VEGA predictions contributed to resolving discrepancies and strengthening the credibility of the overall risk assessment in alignment with ICH M7 guidelines.

3.3. Integrated assessment workflow

The workflow was structured to sequentially apply TOXTREE for initial screening, T.E.S.T. for detailed probabilistic evaluation, and VEGA for in-depth comparative assessment. This systematic approach ensured a thorough evaluation of benzodiazepine mutagenic impurities by identifying consistencies and discrepancies across different QSAR tools. Variations in predictions were carefully analysed, with greater emphasis placed on VEGA outputs because of its advanced modelling capabilities and integration of multiple predictive algorithms, followed by an expert review.

Impurities were classified into distinct risk categories based on the consensus of the three QSAR tools. If all three tools predicted a positive Ames test alert, the impurity was classified as a high risk. Conversely, if all three tools predicted a negative Ames test alert, the impurity was classified as low-risk. In cases where the predictions were discordant, further classification was applied. The result was considered equivocal if one (Q)SAR tool predicted a positive mutagenicity alert (+), whereas the other two tools predicted negative mutagenicity outcomes (-) or lacked sufficient data (NA). A negative outcome (-) in this context means that the (Q)SAR tool did not identify any structural alerts associated with bacterial mutagenicity and predicted the impurity to be non-mutagenic. VEGA, a QSAR tool containing multiple models but used here solely for the CAESAR Ames test model, and TEST provided a negative (non-mutagenic) prediction without an associated confidence warning

The in-silico analysis workflow is presented as a flowchart in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of In-Silico Evaluation and Assessment of Mutagenic Impurities in Benzodiazepine Molecules.

Structural data for 88 impurities associated with 18 benzodiazepine-active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) (Fig. 2) were sourced from the literature and pharmacopoeias to assess their potential genotoxic risks.

Fig. 2.

Chemical Structures of Common Benzodiazepine Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (API's).

3.4. Interpretation of results

Impurities were classified into different risk categories based on the consensus of the three (Q)SAR tools. High-risk impurities (Class 1 or Class 2) were identified when all three tools yielded positive predictions, indicating a high likelihood of mutagenicity. All three tools consistently predicted low-risk impurities (Class 5) as non-mutagenic. Equivocal cases (Class 3) occurred when one tool predicted a positive result while the other two were negative; these underwent expert review. If structural analysis and literature support confirmed a positive alert, the impurity was classified as Class 2; otherwise, it was assigned to Class 5. Impurities with two positive and one negative prediction were also considered potential mutagens (Class 2).

3.5. Expert review process

An expert review was conducted to enhance the reliability of the (Q)SAR predictions and ensure alignment with the ICH M7 guidelines. This process aimed to resolve discrepancies among TOXTREE, T.E.S.T., and VEGA by evaluating structural alerts, applicability domain (AD) coverage, and mechanistic plausibility [26], [27]. The first step involved structural alert assessment, where impurities flagged as mutagenic by TOXTREE were analysed to determine whether the alerts aligned with the established mutagenic mechanisms. This evaluation utilised the scientific literature, regulatory toxicology databases, and known structural alert rules. Alerts lacking mechanistic support or identified as known false positives were deprioritised in classification decisions. Next, an applicability domain (AD) evaluation was conducted to assess the reliability of the predictions from the T.E.S.T. and VEGA tools. Predictions for compounds outside the AD were considered less reliable, and alternative supporting evidence was incorporated to improve classification accuracy.

3.5.1. Applicability domain and overlap with training datasets

To ensure the reliability of QSAR predictions, we evaluated the applicability domain (AD) of the models used in this study. In the T.E.S.T. QSAR tool, 71 out of 88 compounds (80.68 %) were within the applicability domain, indicating reliable predictions, while 17 compounds (19.32 %) were outside the AD, suggesting limited confidence in their predictions. Similarly, in the VEGA QSAR tool the Mutagenicity (Ames test) CAESAR model, 56 out of 88 compounds (63.64 %) were entirely within AD, 20 compounds (22.73 %) were classified as borderline cases (potentially out of AD), and 12 compounds (13.64 %) were explicitly outside AD, requiring cautious interpretation. We comprehensively evaluated the prediction reliability by integrating AD assessments from both T.E.S.T. and VEGA. We ensured that these tools remained applicable to most datasets while identifying lower-confidence cases. Unlike T.E.S.T. and VEGA, TOXTREE does not assess applicability domains because it is a rule-based system that detects toxicity-related structural alerts (SAs). Unlike QSAR models, which use training datasets and descriptor-based chemical spaces, TOXTREE identifies toxicophores without considering chemical-space limitations. Therefore, although TOXTREE is valuable for hazard identification, its predictions should be interpreted cautiously, particularly for novel compounds whose predefined structural alert rules may not be representative.

Additionally, we examined the potential overlap between our experimental dataset and the training sets of QSAR models. A direct comparison was impossible because the complete training datasets for T.E.S.T. and VEGA are not publicly available. However, a chemical space analysis based on structural diversity and similarity suggested that the dataset includes a mix of structurally similar and novel compounds, ensuring that memorised structures from the training data do not solely influence predictions. This finding strengthens the validity of our in silico mutagenicity predictions and supports their regulatory applications.

3.5.2. Evaluating the plausibility of predicted mutagenic mechanisms

The plausibility of the predicted mutagenic mechanisms was assessed by determining the alignment of the QSAR-predicted mechanisms with known toxicological pathways. Mutagenic predictions were considered plausible if they were consistent with the established mechanisms of DNA reactivity, oxidative stress, or metabolic activation, as documented in the scientific literature and regulatory toxicology databases [17]. Steric and electronic effects were considered to refine the mechanistic plausibility [52], particularly for structural alerts requiring metabolic activation. The prediction was downgraded in confidence if a reactive site was sterically hindered or if the electronic distribution prevented DNA interactions. Additionally, structure-activity relationship (SAR) pattern recognition was applied to identify compounds with similar functional groups but differing reactivities, further validating or deprioritising QSAR alerts.

3.5.3. Weight-of-evidence approach for impurity classification

A robust weight-of-evidence (WoE) approach was applied to classify impurities based on QSAR outputs, applicability domain assessments, structural similarity, and mechanistic plausibility. QSAR predictions from T.E.S.T., VEGA, and TOXTREE served as the primary assessment, with a strong consensus across all three models increasing classification confidence. The applicability domain evaluation was used as a supporting factor, where predictions from compounds outside the AD were assigned lower weights owing to reduced reliability. More predictions for structurally similar compounds were considered, notably when multiple analogues confirmed or contradicted the QSAR results. Mechanistic plausibility played a final validation role, ensuring that alerts requiring metabolic activation were considered relevant only when steric and electronic factors permitted activation. This hierarchical integration of QSAR results, AD coverage, structural similarity, and mechanistic considerations ensured that the impurity classification was scientifically robust and aligned with ICH M7 guidelines.

3.5.4. Uncertainty evaluation

Multiple factors were considered to account for uncertainties in the classification. QSAR model confidence was evaluated by assessing the agreement among tools; a strong consensus resulted in higher confidence, whereas conflicting predictions introduced uncertainty. Applicability domain considerations played a key role, where compounds outside AD had inherently lower reliability. The lack of relevant structural analogues further increased the uncertainty, as no comparative data were available to validate the QSAR predictions. Additionally, steric and electronic factors were considered to assess whether QSAR-predicted alerts were truly reactive or mechanistically plausible. A final weight-of-evidence decision was made by integrating all these factors, ensuring that the impurity classification was scientifically valid.

3.6. External validation of QSAR models

To ensure the reliability of QSAR predictions, external validation was performed using a dataset of 99 molecular structures with known Ames test results. This dataset, compiled from experimentally confirmed mutagenicity outcomes, evaluates the predictive performance of T.E.S.T., VEGA, and TOXTREE. Each model's predictions were compared with Ames test classifications, and the following performance metrics were assessed:

3.6.1. Accuracy: proportion of correct predictions (true positives and negatives) in all cases

.

3.6.2. Sensitivity: ability of the model to correctly identify mutagenic compounds (true positives)

.

3.6.3. Specificity: the ability of the model to correctly identify non-mutagenic compounds (true negatives)

.

3.6.4. Precision: proportion of predicted mutagenic compounds that are truly mutagenic

.

Where:

True Positive (TP): Mutagenic compounds were correctly predicted as mutagenic.

True Negative (TN): Non-mutagenic compounds were correctly predicted as non-mutagenic.

False Positive (FP): non-mutagenic compounds incorrectly predicted to be mutagenic.

False Negative (FN): Mutagenic compounds were incorrectly predicted as non-mutagenic.

A confusion matrix was constructed based on the experimental and predicted results to facilitate calculations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Confusion Matrix of Predictions and Experimental Results for the Validation of (Q) SAR Tools.

| Matrix | TOXTREE (In vitro mutagenicity Ames test by ISS | TEST (Predicted Result Nearest Neighbor) | TEST (Predicted Result consensus) | Vega Mutagenicity (Ames test) model (CAESAR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True Positive (TP) | 21 | 11 | 12 | 20 |

| True Negative (TN) | 44 | 33 | 35 | 32 |

| False Positive (FP) | 20 | 16 | 12 | 21 |

| False Negative (FN) | 5 | 9 | 12 | 9 |

The dataset included various chemical classes consisting of 27 Ames test-positive (+) and 72 Ames test-negative (−) compounds, Nitrobenzenes, Aromatic Amines, Aminothiazoles, Quinolinones, Fluoroquinolones, Pyrimidinediones, Triazoles, Heterocyclic compounds, Sulfonyl derivatives, Sulfonate esters, Sulfonyl and benzoyl chlorides, Halogenated alkanes, Halogenated benzenes, Cinnamyl alcohol esters, Benzoates, Phosphorus-containing chemicals, Cyanides, Aldedehydes and Miscellaneous was used for validation, which was presented in Table 8 (Supplementary data)

Because the QSAR tools used in this study were preexisting models that were not modified or retrained, internal validation was not conducted. Instead, external validation was prioritised, as it provides a real-world assessment of QSAR model predictivity and aligns with regulatory expectations under ICH M7 guidelines. Furthermore, applicability domain (AD) considerations were incorporated to determine the reliability of each model's predictions. Impurities outside the AD were flagged as lower-confidence predictions and further evaluated using structural analogue analysis and expert review.

By validating QSAR tools against experimentally verified Ames test data, this study ensures that mutagenicity predictions are scientifically robust and regulatory-compliant. Future refinements should focus on expanding the external validation datasets and integrating metabolic transformation models to enhance the predictive accuracy of QSAR-based mutagenicity assessments.

3.7. Risk classification criteria

Benzodiazepine-related impurities were classified into five risk categories based on the consensus of the TOXTREE, TEST, and VEGA predictions aligned with the ICH M7 guidelines.

3.7.1. High risk (class 2 – known/predicted mutagenic impurities)

All three (Q)SAR tools consistently predicted mutagenic impurities. These impurities are considered high-risk and require analytical monitoring and control limits based on the Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC).

3.7.2. Moderate-high risk (class 2 – potential mutagenic impurities)

Impurities with a positive consensus (two of three tools predicting mutagenicity). These impurities were classified as potential mutagens, requiring control strategies similar to those for high-risk impurities.

3.7.3. Equivocal risk (class 4 – unresolved by QSAR, expert review performed)

Impurities with conflicting QSAR predictions (one positive and two negative) were subjected to expert review. If the structural assessment supported a positive alert (e.g. presence of nitro, azo, or reactive functional groups), the impurity was classified as Class 2. Otherwise, it was assigned to class 5 (non-mutagenic).

3.7.4. Moderate-low risk (class 5 – alerting structure, no mutagenicity evidence)

Impurities with structural alerts but consistently negative predictions across all three tools. These impurities do not require strict regulatory limits unless additional supporting data are provided.

3.7.5. Low risk (class 5 – no structural alerts or non-mutagenic)

All three tools consistently predicted that the impurities were non-mutagenic, indicating no structural alerts or mutagenic concerns. Therefore, these impurities do not require additional regulatory controls.

The comparison and performance of each (Q)SAR tool for the Ames Test Mutagenicity Prediction Models are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Validation Results Across (Q)SAR Tools for Ames Test Mutagenicity Prediction Models.

| Validation parameter | TOXTREE (In vitro mutagenicity Ames test by ISS (%) | TEST (Nearest Neighbor) (%) | TEST (consensus) (%) | Vega Mutagenicity (Ames test) model (CAESAR) (%) |

| Accuracy Result |

72.22 | 63.77 % | 66.20 | 63.41 |

| Sensitivity Result |

80.77 | 55.00 % | 50.00 | 68.97 |

| Specificity Result |

68.75 | 67.35 % | 74.47 | 60.38 |

| Precision Result |

51.22 | 40.74 % | 50.00 | 48.78 |

3.8. Data synthesis

We categorised the impurities using the (Q)SAR data based on their risk level. When all three (Q)SAR tool outputs were positive, the impurity was classified as high-risk. Table 3 shows the distribution of high-risk impurities, Table 4 presents moderate-risk impurities, and Table 5 lists low-risk impurities across various benzodiazepine APIs and

Table 3.

Summary of High-Risk Mutagenic Impurities in Benzodiazepine APIs Identified by (Q)SAR Analysis, and ICH M7 Classification (The (+) symbol represents positive results).

| SL.No | Compound Name | IUPAC Name | Chemical Structure | TOX TREE Result | TEST Result |

VEGA Result | Consensus | Classification | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alprazolam Impurity A |

(4RS)−3-amino−6-chloro−2-methyl−4-phenyl−3,4-dihydroquinazolin−4-ol |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | [23], [25] |

| 2 | Alprazolam Impurity G |

7-chloro−1-methyl−5-phenyl-[1], [2], [4]triazolo[4,3-a]quinolin−4-amine |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 3 | Alprazolam Impurity E |

(2-amino−5-chlorophenyl)phenyl methanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 4 | Bromazepam Impurity A |

(2-amino−5-bromophenyl)(pyridin−2-yl)methanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 5 | Bromazepam Impurity B |

N-[4-bromo−2-(pyridine−2-carbonyl)phenyl]−2-Chloroacetamide |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 6 | Bromazepam Impurity D |

3-amino−6-bromo−4-(pyridin−2-yl)quinolin−2(1H)-one |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 7 | Chlordiazepoxide Impurity B | 6-chloro−2-(chloromethyl)−4-phenylquinazoline 3-oxide |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 8 | Chlordiazepoxide Impurity C | (2-amino−5-chlorophenyl) phenyl methanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 9 | Clonazepam EP Impurity A, USP Related Compound B |

(2-amino−5-nitrophenyl) (2-chlorophenyl) methanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 10 | Clonazepam Related compound C |

2-bromo−2′-(2-chlorobenzoyl)−4′-nitroacetanilide |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | [23], [25] |

| 11 | Diazepam EP Impurity D, USP Related Compound A |

[5-chloro−2-(methylamino) phenyl]phenyl methanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 12 | Flunitrazepam Impurity C |

3-amino−4-(2-fluorophenyl)−1-methyl−6-nitroquinolin−2(1H)-one |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | [25] |

| 13 | Flunitrazepam Impurity D |

(2-fluorophenyl)[2-(methylamino)−5-nitrophenyl]-Methanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 14 | Lorazepam Impurity B |

2-Amino−2′,5-dichloro benzophenone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | [23], [25] |

| 15 | Nitrazepam Impurity B |

(2-amino−5-nitrophenyl)phenyl methanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | [25] |

| 16 | Nitrazepam Impurity C |

2-bromo-N-[4-nitro−2-(phenylcarbonyl)phenyl]acetamide |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 17 | Nitrazepam Impurity D |

2-(1,3-dioxo−1,3-dihydro−2H-isoindol−2-yl)-N-[4-nitro−2-(phenylcarbonyl)phenyl] acetamide |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 18 | Olanzapine Impurity A |

5-Methyl−2-((2-nitrophenyl)amino)−3-thiophenecarbonitrile |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | [23], [25] |

| 19 | Oxazepam Impurity D |

(2-amino−5-chlorophenyl)phenylmethanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 20 | Temazepam Impurity A |

[5-chloro−2-(methylamino)phenyl]phenylmethanone |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | |

| 21 | Zolazepam Impurity A |

2-Azido-N-[4-(2-fluorobenzoyl)−1,3-dimethyl−1H-pyrazol−5-yl]-acetamide |  |

(+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Class 2 | [23] |

Table 4.

Summary of Moderate-Risk Mutagenic Impurities in Benzodiazepine APIs Identified by (Q)SAR Analysis, Expert Review, and ICH M7 Classification (The (+) symbol represents positive results, the (-) symbol represents negative results, and NA represents data not available).

| SL.No | Compound Name | IUPAC Name | Chemical Structure | TOX TREE Result |

TEST Result |

VEGA Result | Consensus | Expert Review | Classification | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alprazolam Impurity F | [5-chloro−2-[3-(chloromethyl)- 5-methyl−4H−1,2,4-triazol−4-yl]phenyl]phenylmethanone |

|

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | [25] |

| 2 | Alprazolam Related Compound A | 2-(2-Acetylhydrazino)−7-chloro−5-phenyl−3H−1,4-benzodiazepine |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | [23] |

| 3 | Bromazepam Impurity C | 7-bromo−5-(6-methylpyridin−2-yl)−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-Benzodiazepine−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [25] |

| 4 | Bromazepam Impurity E | 2-bromo-N-[4-bromo−2-(pyridine−2-carbonyl)-phenyl]acetamide |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | |

| 5 | Chlordiazepoxide Impurity A | 7-chloro−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one 4-oxide |  |

(-) | NA | (+) | Equivocal | Un resolved | Class 4 | [23], [25] |

| 6 | Clonazepam EP Impurity B, USP Related Compound A | 3-amino−4-(2-chlorophenyl)−6-nitroquinolin−2(1H)-one |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | |

| 7 | Diazepam Impurity B | N-(2-benzoyl−4-chlorophenyl)−2-chloro-N-methylacetamide |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | [25] |

| 8 | Diazepam EP Impurity C, USP Related Compound B | 3-amino−6-chloro−1-methyl−4-phenylquinolin−2(1H)-one |  |

(+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 9 | Diazepam Impurity F | 7-chloro−2-methoxy−5-phenyl−3H−1,4-benzodiazepine |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [25] |

| 10 | Flunitrazepam EP Impurity A | 7-amino−5-(2-fluorophenyl)−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 11 | Flunitrazepam EP Impurity B | 5-(2-fluorophenyl)−7-nitro−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4 benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | |

| 12 | Flurazepam EP Impurity A |

[5-chloro−2-[[2-(diethylamino)ethyl]amino]phenyl](2-fluorophenyl)methanone |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 13 | Flurazepam Related compound C | 5-Chloro−2-(2-diethylaminoethylamino)−2′-fluorobenzophenone hydrochloride |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [23] |

| 14 | Flurazepam EP Impurity C | 7-chloro−5-(2-fluorophenyl)−1-[(1RS)−1-hydroxyethyl]−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [25] |

| 15 | Lorazepam Related compound A | 7-Chloro−5-(o-chlorophenyl)−1,3-dihydro−3-acetoxy−2H−1,4benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [23] |

| 16 | Lorazepam Related compound C | 6-Chloro−4-(o-chlorophenyl)−2-Quinazolinecarboxaldehyde |  |

(+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [23] |

| 17 | Lorazepam Related compound D | 6-Chloro−4-(o-chlorophenyl)−2-quinazolinecarboxylic acid |  |

(-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 18 | Lorazepam Related compound E | 6-Chloro−4-(o-chlorophenyl)−2-quinazoline methanol |  |

(-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 19 | Lorazepam EP Impurity D |

(5RS)−7-chloro−5-(2-chlorophenyl)−4,5-dihydro−1H−1,4-benzodiazepine−2,3 dione |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [25] |

| 20 | Midazolam EP Impurity A |

(6RS)−8-chloro−6-(2-fluorophenyl)−1-methyl−5,6-dihydro−4H-imidazo[1,5-a][1], [4]benzodiazepine |  |

(-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 21 | Midazolam EP Impurity H |

6-chloro−4-(2-fluorophenyl)−2-methylquinazoline |  |

(-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [25] |

| 22 | Midazolam EP Impurity I |

(3aRS)−8-chloro−6-(2-fluorophenyl)−1-methyl−3a,4-dihydro−3H-imidazo[1,5-a][1], [4]benzodiazepine |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 23 | Midazolam Nitromethylene compound | 7-Chloro−1,3-dihydro−2-nitromethylene−5-(2-fluorophenyl)−2H−1,4-benzodiazepine−4-oxide |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [23] |

| 24 | Nitrazepam EP Impurity A |

3-amino−6-nitro−4-phenylquinolin−2(1H)-one |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | [25] |

| 25 | Olanzapine piperazin Impurity | 2-methyl−4-(4-methyl piperazin−1-yl)−10-((methylthio)methyl)-thieno[2,3-b][1], [5] benzodiazepine. |  |

(-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [28] |

| 26 | Olanzapine imidazole impurity | 10-(3-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol−2-yl)−5-methylthiophen−2-yl)−2-methyl−4-(4-methyl piperazin−1-yl)-thieno[2,3-b][1], [5]benzodiazepine |  |

(-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 27 | Olanzapine Impurity B |

2-Methyl−10H-thieno-[2,3-b][1], [5]benzodiazepin−4[5H]-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 28 | Olanzapine Impurity C |

1-Chloromethyl−1-methyl−4-(2-methyl−10H-benzo[b]thieno[2,3-e][1], [4]diazepin−4-yl)piperazin−1-ium chloride |  |

(+) | NA | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | |

| 29 | Olanzapine Impurity D |

1-methyl−4-(2-methyl−10H-thieno[2,3-b][1], [5]benzodiazepin−4-yl)piperazin−1-oxide |  |

(-) | NA | (+) | Equivocal | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [25] |

| 30 | Olanzapine methyl thiophene impurity | 1-(5-methylthionphen−2-yl)−1H-benzimidazol−2(3H)-one |  |

(-) | NA | (+) | Equivocal | Unresolved | Class 4 | [29] |

| 31 | Olanzapine Hydroxy methylidene thione impurity |

4-(4-methyl−1-piperazinyl)−3-hydroxymethylidene−1H-benzo[b][1], [4]diazepine−2(3H)-thione |  |

(-) | NA | (+) | Equivocal | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [30] |

| 32 | Olanzapine Acetoxy methylidene thione impurity |

(Z)−4-(4-methyl−1-piperazinyl)−3-acetoxymethylidene−1H-benzo[b][1], [4]diazapine−2(3H)-thione |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 33 | Oxazepam Impurity A |

(5RS)−7-chloro−5-phenyl−4,5-dihydro−1H−1,4-benzodiazepine−2,3-dione |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 34 | Oxazepam Impurity B |

(3RS)−7-chloro−2-oxo−5-phenyl−2,3-dihydro−1H−1,4 benzodiazepin−3-yl acetate |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | |

| 35 | Oxazepam Impurity C |

6-chloro−4-phenylquinazoline−2-carbaldehyde |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as class 2 | Class 2 | [23], [25] |

| 36 | Oxazepam EP Impurity E, USP Related Compound A |

7-chloro−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one 4-oxide |  |

(-) | NA | (+) | Equivocal | unresolved | Class 4 | |

| 37 | Quazepam Impurity A |

7-Chloro−1-(2,2,2 trifluoroethyl)−5-(2-Fluorophenyl)−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepine−2-one |  |

(-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as Class 5 | Class 5 | [23] |

| 38 | Temazepam Impurity C |

(3RS)−7-chloro−1-methyl−2-oxo−5-phenyl−2,3-dihydro−1H−1,4-benzodiazepin−3-yl acetate |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as Class 5 | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 39 | Temazepam Impurity D |

(3RS)−7-chloro−3-methoxy−1-methyl−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as Class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 40 | Temazepam Impurity E |

7-chloro−1-methyl−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one 4-oxide |  |

(-) | NA | (+) | Equivocal | unresolved | Class 4 | |

| 41 | Temazepam Impurity F |

(5RS)−7-chloro−1-methyl−5-phenyl−4,5-dihydro−1H−1,4-benzodiazepine−2,3-dione |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 42 | Temazepam Impurity G |

(5RS)−7-chloro−1,4-dimethyl−5-phenyl−4,5-dihydro−1H−1,4-benzodiazepine−2,3-dione |  |

(-) | (-) | (+) | (-) | Resolved as Class 5 | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 43 | Tetrazepam keto impurity | 7-chloro−5-(3-keto-cyclohexen−1 -yl)−1,3-dihydro−1 -methyl−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as Class 5 | Class 5 | [31] |

| 44 | Tetrazepam epoxy impurity | 7-chloro−5-(1,2-epoxy cyclohexane−1-yl)- 1,3-dihydro−1-methyl−2H−1,4-benzodiazepine−2-one |  |

(+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Resolved as Class 5 | Class 5 | |

| 45 | Triazolam Impurity A | 2-(2-Acetylhydrazino)−7-chloro−5-phenyl−3H−1,4-Benzodiazepine |  |

(+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | Resolved as Class 2 | Class 2 | [23] |

Table 5.

Summary of Low-Risk Mutagenic Impurities in Benzodiazepine APIs, Identified by (Q)SAR Analysis, and ICH M7 Classification, The (-) symbol represented negative results.

| SL. No | Compound Name | IUPAC Name | Chemical Structure | TOX TREE Result |

TEST Result |

VEGA Result | Consensus | Classification | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alprazolam EP Impurity B | [5-chloro−2-[3-(hydroxymethyl) −5-methyl−4H−1,2,4-triazol−4-yl] phenyl] phenylmethanone |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [25] |

| 2 | Alprazolam EP Impurity C | [5-chloro−2-[3-methyl−4H−1,2,4-triazol−4-yl]phenyl]phenylmethanone |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | |

| 3 | Alprazolam EP Impurity D | 8-chloro−1-ethenyl−6-phenyl−4H-[1,2,4]triazolo[3a,4][1,4]benzodiazepine |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | |

| 4 | Diazepam Impurity A | 7-chloro−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one (nordazepam) |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 5 | Diazepam Impurity E | 6-chloro−1-methyl−4-phenylquinazolin−2(1H)-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [25] |

| 6 | Alpha-hydroxy etizolam | 1-[7-(2-chlorophenyl)−13-methyl−3-thia−1,8,11,12-tetrazatricyclo[8.3.0.02,6]trideca−2(6),4,7,10,12-pentaen−4-yl]ethanol |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [32], [33] |

| 7 | Flurazepam EP Impurity B, USP impurity F | 7-chloro−5-(2-fluorophenyl)−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 8 | Lorazepam EP Impurity-C | 7-chloro−5-(2-chlorophenyl)−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4 benzodiazepin−2-one 4-oxide |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [25] |

| 9 | Midazolam EP Impurity B, USP Impurity H | (6RS)−8-chloro−6-(2-fluorophenyl)−1-methyl−6H-imidazo-[1,5-a][1], [4]benzodiazepine |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 10 | Midazolam Impurity J | 8-Chloro−6-(2-fluorophenyl)−3a,4,5,6-tetrahydro−1-methyl−3H-imidazo[1,5-a][1], [4]-benzodiazepine |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [23] |

| 11 | Midazolam EP Impurity C | 8-chloro−6-(2-fluorophenyl)−1-methyl−4H-imidazo[1,5a][1,4]benzodiazepine−3-carboxylic acid |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [25] |

| 12 | Midazolam EP Impurity D | 8-chloro−6-(2-fluorophenyl)−1-methyl−4H-imidazo-[1,5-a][1], [4]benzodiazepine 5-oxide |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 13 | Midazolam EP Impurity E | [(2RS)−7-chloro−5-(2-fluorophenyl)−2,3-dihydro−1H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-yl]methanamine |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | |

| 14 | Midazolam Impurity F | 7-Chloro−5-(2-fluorophenyl)−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [25] |

| 15 | Midazolam Impurity G | 8-chloro−1-methyl−6-phenyl−4H-imidazo-[1,5-a][1], [4]benzodiazepine |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [23], [25] |

| 16 | Temazepam Impurity B | (3RS)−7-chloro−3-hydroxy−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | |

| 17 | Tetrazepam EP Impurity A | 7-chloro−1-methyl−5-(3-oxocyclohex−1-enyl)−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [25] |

| 18 | Tetrazepam EP Impurity B | 7-chloro−5-cyclohexyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | |

| 19 | Tetrazepam EP Impurity C | 7-chloro−5-cyclohexyl−1-methyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | |

| 20 | Tetrazepam EP Impurity D | 7-chloro−5-(1-chlorocyclohexyl)−1-methyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | |

| 21 | Tetrazepam EP Impurity E | 7-chloro−5-(cyclohex−1-enyl)−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | |

| 22 | Tetrazepam dihydro impurity | 7-chloro−1,3- dihydro−1-methyl−2H−1,4-benzodiazepine−2,5-dione |  |

(-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Class 5 | [31] |

The distribution of risk levels high, moderate, and low in various benzodiazepine impurities is shown in Fig. 3

Fig. 3.

Distribution of High, Moderate, and Low-Risk Levels in Various Benzodiazepine APIs.

If one or two (Q) SAR tool results were positive or negative, we categorised the impurity as moderate risk, as presented in Table 4.

We considered the impurity low risk when all three (Q) SAR tool outputs were negative, as indicated in Table 5.

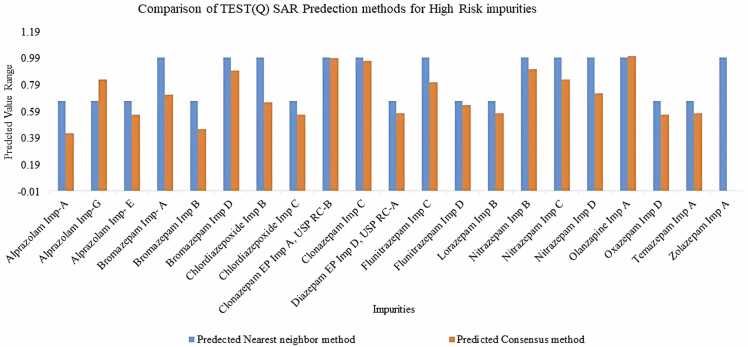

The comparison of High-Risk Predicted Value of TEST QSAR Tools for Mutagenicity Endpoint: Consensus vs Nearest Neighbor Method shown in (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

High-Risk Predicted Values of TEST QSAR Tool for Mutagenicity Endpoint: Consensus Comparison with Nearest Neighbor Method.

4. Results

The mutagenic potential of 88 benzodiazepine impurities was assessed using three in silico (Q)SAR tools: TOXTREE, VEGA, and the Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (TEST), following the ICH M7 guidelines. TOXTREE exhibited the highest accuracy (72.2 %) and sensitivity (80.7 %) for Ames test predictions, demonstrating a strong performance in detecting true positives. VEGA's Ames mutagenicity model provided balanced sensitivity (68.9 %) and specificity (76.5 %), whereas TEST's consensus model outperformed its nearest-neighbour counterpart regarding accuracy and specificity.

Based on in silico analysis, 21 impurities were classified as high risk due to consistently positive predictions across all three tools, indicating a significant mutagenic potential requiring stringent monitoring and control. Additionally, 45 impurities in Table 4, 11 as moderate to high risk, 28 as moderate low risk, 22 as low risk, and 6 compounds fall under the equivocal category and classification finalised by expert review. Class 4 categories across models require further experimental evaluation.

Discrepancies between QSAR predictions were analysed with expert input guiding the interpretation of borderline extreme cases.

An expert review was conducted for moderate-risk benzodiazepine impurities, which were further classified into moderate-low, moderate-high, and equivocal categories, as presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Risk Assessment table for benzodiazepine impurities.

| Risk Category | Criteria | Total compounds | ICH M7 Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Risk | All Positive Predictions | 21 | Class 2 (Known/Predicted Mutagenic Impurities) |

| Moderate-High Risk | Positive Consensus | 11 | Class 2 (Known/Predicted Mutagenic Impurities) |

| Moderate-Low Risk | Negative Consensus | 28 | Class 5 (Alerting Structure, No Mutagenicity) |

| Low Risk | All Negative Predictions | 22 | Class 5 (No Structural Alerts or Non-Mutagenic) |

| Equivocal | Unresolved (One Positive, One Negative) | 2 | Class 5 (Expert Review Finalized) |

| 4 | Class 4 (Expert review unresolved) |

Among these, impurities in the equivocal category require further evaluation because of the inconsistent (Q)SAR predictions. These impurities were subjected to detailed structural analysis to determine their mutagenic risk, focusing on structural alert concerns and metabolic activation potential. The results of this structural assessment are summarised in Table 6.

Table 6.

Structural Analysis and Mutagenicity Risk Assessment by Expert Review for Equivocal Category Impurities.

| Impurity Name | IUPAC Name | Structural Alert Concerns | Metabolic Activation Concern | Expert Review Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlordiazepoxide Impurity A | 7-chloro−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one 4-oxide | Oxygenated benzodiazepine scaffold, chloro substitution | Potential reduction to reactive species | Requires experimental validation (Class 4) |

| Olanzapine Impurity D | 1-methyl−4-(2-methyl−10H-thieno[2,3-b][1,5]benzodiazepin−4-yl)piperazin−1-oxide | Thieno benzodiazepine, Piperazine-oxide | Limited metabolic activation, but oxidation potential exists | Class 5 (No strong evidence of mutagenicity) |

| Olanzapine Methyl Thionphen Impurity | 1-(5-methylthionphen−2-yl)−1H-benzimidazol−2(3H)-one | Benzimidazole core, methyl-thiophene | Potential for metabolic activation via oxidation | Requires experimental validation (Class 4) |

| Olanzapine Hydroxy Methylidene Thione Impurity | 4-(4-methyl−1-piperazinyl)−3-hydroxymethylidene−1H-benzo[b][1,4]diazepine−2(3H)-thione | Hydroxy-methylidene thione, benzodiazepine core | Potential for oxidation to reactive metabolites | Class 5 (No strong alerts or supporting Ames data) |

| Oxazepam EP Impurity E, USP Related Compound A | 7-chloro−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one 4-oxide | Oxygenated benzodiazepine scaffold, chloro substitution | Potential for reductive activation | Requires experimental validation (Class 4) |

| Impurity E (Temazepam-related) | 7-chloro−1-methyl−5-phenyl−1,3-dihydro−2H−1,4-benzodiazepin−2-one 4-oxide | Methylated benzodiazepine-oxide, chloro substitution | Potential reduction of reactive species | Requires experimental validation (Class 4) |

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of QSAR methodologies in compliance with ICH M7

The ICH M7 guidelines recommend applying two complementary (Q)SAR methodologies—one expert rule-based and one statistical-based—to improve the reliability of mutagenicity assessments. Rule-based models rely on well-established toxicological knowledge to identify structural alerts associated with mutagenicity and provide a clear mechanistic interpretation. However, they are inherently limited by predefined rules, meaning they may fail to detect novel mutagenic mechanisms.

Statistical-based models, however, analyse large datasets of experimentally validated compounds to detect patterns beyond predefined alerts. These models offer greater flexibility but are highly dependent on the quality and diversity of their training data, which can affect their reliability when assessing structurally novel impurities. By integrating both approaches, a weight-of-evidence strategy strengthens impurity classification and supports regulatory decision-making. A scientific justification is required if only one methodology is used, as per the ICH M7 guidelines.

5.1.1. Expert rule-based models

Expert rule-based models such as TOXTREE apply a set of predefined structural alerts derived from known mutagenicity mechanisms. These models systematically analyse molecular structures to determine the presence of reactive functionalities linked to DNA damage or mutagenicity. Their primary advantage lies in their transparency and mechanistic interpretability, making them valuable for identifying well-characterised mutagenic risks. However, their reliance on fixed rule sets may cause them to overlook emerging mutagenicity mechanisms that are not explicitly encoded in the system.

5.1.2. Statistical-based models

Statistical-based models, such as TEST (Toxicity Estimation Software Tool), use machine learning algorithms and statistical regression models trained on large datasets of experimentally validated compounds. These models predict mutagenicity based on molecular descriptors and structure-activity relationships (SARs) rather than relying on predefined alerts. Their data-driven approach allows the assessment of structurally diverse compounds, including those without known alerts. However, their reliability depends heavily on the representativeness of their training datasets, meaning that predictions can be less accurate for compounds that fall outside the model's chemical space.

5.1.3. Hybrid QSAR approaches

The VEGA platform integrates multiple (Q)SAR models, including rule-based and statistical methodologies, making it a hybrid system that enhances prediction reliability. By combining different predictive algorithms and mechanistic insights, VEGA provides quantitative applicability domain (AD) assessments, ensuring that predictions are scientifically valid and relevant to the assessed impurity.

VEGA serves as a bridge between rule-based and statistical models, allowing for the cross-validation of predictions. This integration is particularly valuable when rule-based models lack coverage for novel structures or when statistical models yield uncertain results. By leveraging both methodologies, VEGA aligns with ICH M7 recommendations to improve confidence in mutagenicity assessments. This approach reduces the risk of false positives and negatives, reinforcing the scientific rigor of impurity risk evaluation.

5.2. Application of QSAR methodologies in impurity classification

The combined use of (Q)SAR tools enhances the reliability of mutagenicity risk assessment and ensures compliance with ICH M7 recommendations. This study utilised TOXTREE for initial structural alert screening, while T.E.S.T and VEGA provided quantitative predictions and additional corroboration. The expert review process was instrumental in refining the impurity classification by resolving discrepancies among QSAR predictions, ensuring a scientifically robust and well-justified assessment of benzodiazepine API impurities.

Using multiple (Q)SAR tools follows ICH M7 weight-of-evidence approach, ensuring that impurity classifications are not based on a single predictive model but on a balanced assessment of mechanistic alerts, statistical analysis, and expert review. This integrated approach minimises uncertainty and enhances regulatory confidence in impurity classification and control strategies [38].

High- and moderate-high-risk impurities were classified as ICH M7 Class 2, based on consistent positive predictions across all QSAR tools or strong positive consensus. These impurities require stringent control measures, including limits based on the Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC) and the development of sensitive analytical methods for monitoring.

Moderate-low-risk impurities, classified under ICH M7 Class 5, contained structural alerts but were predicted to be non-mutagenic by all tools. Although immediate regulatory action is unnecessary, continuous monitoring is advisable if new data emerges. Similarly, low-risk impurities without structural alerts or mutagenicity predictions require no further regulatory controls.

Equivocal impurities, categorised as ICH M7 Class 4, exhibited inconsistent (Q)SAR predictions and were subjected to an expert review. This evaluation led to their final classification as Class 5, indicating the absence of additional regulatory actions. However, further experimental validation, such as Ames testing, is recommended to confirm the classification and reduce the uncertainty in borderline cases.

5.3. Limitations and future perspectives

Although in silico methodologies provide an efficient and scientifically sound approach to mutagenicity prediction, they have inherent limitations. The absence of experimental validation limits their ability to fully confirm predictions, and the chemical diversity of the training datasets influences their accuracy. This is particularly relevant for benzodiazepine impurities, where structural variability may affect model reliability.

Future research should focus on integrating experimental validation with computational assessments to refine the predictive models and increase confidence in borderline cases. Expanding training datasets to include structurally diverse compounds can help mitigate the limitations of statistical-based QSAR models. Developing hybrid QSAR approaches and incorporating rule-based mechanisms with deep-learning statistical models could also significantly enhance predictive performance.

The broader adoption of in silico tools for pharmaceutical impurity assessment can improve regulatory compliance, streamline risk assessments, and reduce reliance on in vivo testing. However, to ensure scientifically sound and regulatory-compliant impurity evaluations, in silico predictions should be complemented by experimental data, when necessary.

6. Conclusion

The predictive performance and regulatory applicability of (Q)SAR-based mutagenicity assessments are contingent upon the quality of training datasets, mechanistic interpretability, and consideration of metabolic activation pathways. Although TOXTREE, T.E.S.T., and VEGA have demonstrated utility in evaluating the mutagenic potential of benzodiazepine impurities, opportunities exist to enhance their predictive power and reliability through methodological refinements.

One of the primary areas of improvement is the expansion of QSAR training datasets to encompass a more diverse chemical space, particularly concerning pharmaceutical impurities. Many existing QSAR models have been developed and validated using industrial chemical, pesticide, and known carcinogen datasets. However, these may not fully capture the structural diversity and metabolic transformation characteristics of drug-related impurities. Including pharmaceutical-specific compounds in QSAR training sets would improve their relevance to impurity assessment and reduce the likelihood of false-positive or false-negative predictions in the context of pharmaceutical mutagenicity evaluations.

Beyond dataset expansion, integrating advanced machine learning (ML) methodologies represents a promising avenue for refining QSAR models. Conventional QSAR approaches primarily rely on predefined molecular descriptors and expert-defined structural alerts, which may not adequately capture the complex, nonlinear relationships between chemical structure and biological activity. The application of deep learning architectures, random forest classifiers, and support vector machines has demonstrated an enhanced predictive performance in toxicology modelling by leveraging data-driven pattern recognition to identify mutagenicity determinants that may not be evident through traditional QSAR paradigms. Incorporating AI-driven QSAR frameworks can enhance the prediction accuracy, improve model generalisability, and provide a more robust basis for in silico mutagenicity assessment.

Another critical limitation of current QSAR models is the incomplete representation of metabolic activation processes, which play a pivotal role in the mutagenicity of many pharmaceutical impurities. Several compounds exhibit mutagenicity only after biotransformation into reactive electrophilic metabolites, which is a phenomenon in which rule-based or statistical QSAR models are not adequately captured. Although some predictive tools, such as the OECD Toolbox and certain VEGA submodels, incorporate metabolic transformation modules, these approaches remain limited in their ability to fully recapitulate enzyme-specific metabolic pathways and the formation of DNA-reactive intermediates. Developing hybrid QSAR models that integrate computational metabolism prediction algorithms with traditional structure-activity relationship (SAR) analyses would provide a more physiologically relevant assessment of mutagenicity potential, particularly for compounds subject to extensive Phase I and Phase II metabolism.

6.1. Variability of Ames test results

In addition to these refinements in the QSAR methodology, it is crucial to acknowledge the inherent variability associated with the Ames test results, which directly affect the interpretation and validation of in silico mutagenicity predictions. The reproducibility of Ames test outcomes between laboratories varies from 80 % to 90 %, with discrepancies arising from differences in bacterial strain selection, metabolic activation conditions (S9 fraction) [35], test concentrations, and procedural variations. Notably, using rat-derived [36] versus human-derived S9 fractions [37] can influence the metabolic activation of test compounds, leading to inter-laboratory differences in mutagenicity outcomes. Furthermore, variations in plating techniques, incubation periods, and solvent controls contribute to experimental inconsistencies, further complicating the direct comparison of the Ames test results across different testing facilities.

This recognised variability underscores the need for harmonised Ames test datasets to enhance the QSAR model training and validation reliability. A curated database integrating Ames test data from multiple laboratories under standardised testing conditions would provide a more robust reference set for in silico model development. Integrating such datasets with advanced QSAR methodologies, including machine learning algorithms and metabolism-aware modelling, would substantially improve the predictive reliability of in silico mutagenicity assessments and further align these approaches with the regulatory expectations under ICH M7.

Refinements in QSAR models through expanded training datasets, machine learning integration, and metabolic activation modelling are critical for improving the accuracy of mutagenicity predictions. Recognising the variability of the Ames test results reinforces the importance of applying a weight-of-evidence approach in regulatory decision-making. Addressing these challenges will further strengthen the scientific and regulatory credibility of QSAR-based mutagenicity assessments and ensure their continued applicability in pharmaceutical impurity risk evaluation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Srinivas Birudukota: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Bhaskar Mangalapu: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ramesha Andagar Ramakrishna: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Swagata Halder: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors did not employ generative AI tools to draft or edit this manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the REVA University for their invaluable support. Special recognition goes to Professor Madhusudhana Reddy M. B. Heartfelt appreciation goes to Trroy Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd. and Flowchem Pharma Pvt. Ltd. for their support.

Handling Editor: Prof. L.H. Lash

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2025.102008.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Sigel E., Ernst M. Benzodiazepine binding sites of GABAA receptors. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2018 Jul;39(7):659–671. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waters L., Manchester K.R., Maskell P.D., Haegeman C., Haider S. A quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) model was used to predict GABA-A receptor binding of newly emerging benzodiazepines. Sci. Justice. 2018 May;58(3):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen M.J., Sabir S., Sharma S. GABA Recept. 2024 〈https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526124/〉 PMID: 30252380. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewett B.E., Sharma S. Physiol., GABA. 2024 PMID: 30020683 〈https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513311/〉. [Google Scholar]