Abstract

Objectives.

Functional limitation is a major driver of medical costs. This study evaluates the prevalence of functional limitation among adults with arthritis, the frequency of functional decline over two years, and investigates factors amenable to public health intervention that predict functional decline.

Methods.

Longitudinal data (1998–2000) from a cohort of 5715 adults 65 years or older with arthritis from a national probability sample are analyzed. Function was defined from ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and basic ADL tasks. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) from multiple logistic regression estimated the association between functional decline with comorbid conditions, health behaviors, and economic factors.

Results.

Overall, 19.7% of this cohort had functional limitation at baseline, including 12.9% with ADL limitations. Over the subsequent two years, function declined in 13.6% of those at risk. Functional decline was most frequent among older women (15.0%) and minorities with arthritis (18.0% Hispanics, 18.7% African Americans). Lack of regular vigorous physical activity (RVPA), the most prevalent risk factor (65%), almost doubled the odds of functional decline (AOR=1.9 95% CI =1.5, 2.4) controlling for all risk factors. If all subjects engaged in RVPA, the expected functional decline could be reduced as much as 36%. Other significant predictors included cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, diabetes, physical limitations, no alcohol use, stroke, and vision impairment.

Conclusions.

Lack of RVPA is a potentially modifiable risk factor, which could substantially reduce functional decline and associated health care costs. Prevention/intervention programs should include RVPA, weight maintenance, and medical intervention for health needs.

INTRODUCTION

High economic, societal, and personal costs from functional limitation among older adults, makes the prevention of functional problems an important public health issue.1–3 Medical spending among the elderly is related more strongly to the presence of functional limitation than remaining life expectancy.4, 5 Over 44 million Americans had one or more conditions that result in a limitation of life activities during 1999. 6 Direct medical costs for persons with disability exceeded $260 billion in 1996.6 Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (hereafter called arthritis) are leading causes of disability in the United States.6 Arthritis affects almost 60% of persons 65 years and older,7 of whom more than one in ten persons report activity limitations.8 By 2010 almost 40 million persons 65 years or older are projected to have arthritis, potentially escalating the numbers of older adults with functional impairments.9

Understanding risk factors related to functional decline is essential to the development of population-based public health programs to help maintain functional abilities and prevent limitation among older adults with arthritis. While population-based longitudinal studies have investigated risk factors for functional decline, they have not been specific to persons with arthritis.10–12 Literature dealing with functional limitation in arthritis includes a wealth of cross-sectional studies, but few longitudinal studies;13, 14 and even these have not been based on national samples.

The present study addresses three questions on functional limitation among persons aged 65 and older with arthritis. First, what is the frequency with which this cohort experiences functional task limitations? Second, what is the magnitude of two-year functional decline among persons at risk? Third, what factors amenable to intervention, are the strongest predictors of functional decline? These questions are addressed using longitudinal 1998–2000 data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The 1998 HRS is a national probability sample, facilitating findings that represent the national experience. Identification of comorbidities, health behaviors, and/or economic factors that may reduce functional decline in the cohort of persons 65 or older with arthritis is important information to address economic and personal costs in this high-risk disability group whose medical costs are largely covered by public insurance via Medicare.

METHODS

Study Population

This study analyzed national public data on adults age 65 years or older with arthritis. This arthritis cohort is taken from the 1998 Health and Retirement Study (HRS) national probability sample of US adults, who are interviewed biennially.15 The HRS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging, conducted by the University of Michigan, and is described in detail elsewhere.16 Estimates of the prevalence of functional limitations are based on the arthritis cohort of 5715 respondents age 65 and older. Analyses on risk factors of functional decline are restricted to 4922 arthritis cohort members at risk of decline, whose function was ascertained at the subsequent 2000 interview.

Arthritis

Baseline (1998) arthritis was determined from an affirmative response to the question, "Have you ever had or has a doctor ever told that you have arthritis or rheumatism?" Self-reported arthritis is relevant from a public policy perspective because many persons with arthritis do not see a health care provider for their symptoms;17 thus, measuring the full burden of arthritis often relies on self-reported data.

Functional Limitation

We adhere to the Institute of Medicine’s classification,18 which defines functional limitation as the inability to carry out functional tasks at the personal level. Functional limitations are defined in terms of higher-level instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and basic ADL tasks. IADL tasks included: preparing hot meals, shopping for groceries, making telephone calls, taking medications, and managing money. ADL tasks included: walking across a room, dressing, bathing, eating, using the toilet, and transferring from a bed. A limitation in a specific IADL or ADL task expected to last three months or longer is ascertained from affirmative responses to avoidance, inability, or receiving help or using equipment to perform the task. Functional limitation in 1998 and 2000 was classified as either none; mild=IADL only; moderate=1-2 ADL; severe=≥3ADL limitations. This categorization parallels the definition of Mor and colleagues.19 Functional decline was identified by two-year progression to a more severe level functional limitation, to capture substantial change in a person’s ability to function independently.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics included race/ethnicity, age, gender, and marital status. HRS ethnicity/race information was used to classify people into three mutually exclusive groups: (non-Hispanic) African American, Hispanic, and (non-Hispanic) White/Other.

Comorbid health conditions were assessed at baseline from self-reported health information. Chronic health conditions were ascertained from a self-report of a physician diagnosis of conditions that included cancer, diabetes, heart disease (heart attack, coronary artery disease, angina, and congestive heart failure), hypertension, pulmonary disease (chronic bronchitis, emphysema, not including asthma), or stroke. The presence of depressive symptoms was determined by an abbreviated Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) assessment. For analytic purposes, the presence of depressive symptoms was determined from the report of one or more non-somatic CES-D mood items (felt depressed, not happy, felt lonely, did not enjoy life, felt sad), consistent with work by Stump and colleagues, 20 to avoid confounding somatic depressive symptoms with arthritis-related symptoms. Cognitive status is based on a summary measure from response to tests indicating four types of mental ability: a modified version of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS), tests of immediate and delayed verbal recall, and Serial 7’s test21. Scores from these individual measures were combined into a single summary measure of cognitive function scaled from 0 to 35, ranging from lower to higher ability. Following the practice of HRS researchers, respondents scoring 8 or less on the summary measure were classified as having moderate to severe cognitive impairment.21 Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI)≥30 [weight (kg)]/[height (m)]2, calculated from self-reported height and weight. Low weight was defined as BMI <18.5.22 Vision impairment was based on the report of poor vision or legally blind.

Since severity of disease was not assessed by HRS, a surrogate of disease/arthritis severity based on limitations in physical activities was used in sensitivity analyses. The presence of physical limitations was assessed from reports of inability or avoidance of walking several blocks, climbing several flights of stairs without resting, pulling or pushing large objects, lifting or carrying weights over 10 pounds.

Health behavior factors included smoking, alcohol consumption, regular vigorous physical activity (RVPA), and weight change. Smoking was ascertained from a positive response to “Do you smoke cigarettes now?” Alcohol use was based on an affirmative answer to “Do you ever drink any alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, or liquor?” Regular vigorous physical activity was based on a positive response to “On average, over the last 12 months have you participated in vigorous physical activity or exercise three times a week or more? By vigorous physical activity, we mean things like sports, heavy housework, or a job that involves physical labor.” Weight change two years prior to baseline or since the previous HRS interview (1995–1996) was characterized as: gain over 10 pounds, loss over 10 pounds, or stable. Weight change was imputed as stable for 2.3% of the arthritis cohort, for whom weight change information was not available. Sensitivity analyses omitting these people produced virtually identical results.

Economic access factors included education, wealth, and family income and health insurance. Education, a measure of human capital, was dichotomized as 12 or more versus fewer completed years of education. For analytic purposes family income (all sources received by the respondent and spouse/partner during the preceding year) and wealth were dichotomized using the lowest 1998 HRS population-weighted quartiles of $16,800 and $44,800, respectively. If only partial income or wealth information was provided, dichotomized values were based on imputed estimates developed at the University of Michigan23. Health insurance information distinguished private insurance holders from reliance solely on Medicare, Medicaid, and other government health insurance (e.g., insurance through the Veterans Administration).

Statistical Analysis

The HRS is a national probability sample. All analyses use person-weights, stratum, and sampling error codes for the 1998 HRS data developed at the University of Michigan24 to provide valid inferences to the U.S. population. Analyses use SUDAAN software to account for the complex HRS sampling design and the arthritis subset analyzed.25 All statistical testing is done at a nominal five percent alpha significance level.

Prevalence estimates of functional limitation are based on a cohort of 5715 persons age 65 or older interviewed by the 1998 HRS with self-reported arthritis and baseline information. Another 609 persons with proxy interviews were handled as 1998 HRS non-respondents. For analytical purposes, an additional 6 with missing baseline functional information, and 53 with insufficient data on baseline covariates were omitted from analyses. To make statements about two-year functional decline, we limited these analyses to 4922 members of the 1998 arthritis cohort at risk of decline who lived at least 2 years following the 1998 interview, excluding by design 180 persons reporting severe (≥3ADL) baseline limitation and 366 decedents. For analytical purposes, 239 HRS 2000 non-respondents and 8 with missing follow-up functional information were also omitted from functional decline analyses.

We adjust for potential bias due to missing interview information and/or non-response by handling respondents with complete data as an additional sampling stage to obtain adjusted sampling weights, using standard sampling methodology. 26 The adjusted sampling weight for arthritis cohort members equals the 1998 HRS sampling weight multiplied by the inverted probability of being in the study cohort given the following characteristics: age, gender, race/ethnicity, an incomplete interview, Spanish language, proxy or phone interview, designated respondent, Hispanic ethnicity, education, withholding permission to additional records, changed residence, number of children, chronic diseases, nonresponse to sensitive questions, negative interview attitude, and geographic region. That probability is estimated using logistic regression.

Direct standardization methods 26 are used to illustrate the potential mediating effect of a risk factor on functional decline. This approach averages the expected functional decline probabilities across the cohort members based on the estimated multiple logistic model given the actual characteristics of each person (comorbidities, health behaviors, economic resources, demographics) but without the target risk factor.

To determine the relative effect of risk factors on functional decline, demographic, comorbidties, health behaviors, and economic resource factors were simultaneously included in a multiple regression logistic model. Based on this inclusive model, those risk factors with the highest adjusted odd ratios (AOR) are the strongest predictors of functional decline relative to other investigated risk factors.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics from the 5715 members of the 1998 HRS arthritis cohort aged 65 or older are shown in Table 1. This population of Medicare-aged persons with arthritis is primarily female (64.2%), and includes 8.6% African Americans and 4.5% Hispanics. More than 87.8% of this cohort reported one or more comorbid health conditions. Comorbid health conditions were particularly more frequent among minorities (African Americans: 93.8%, Hispanics: 93.1%) than Whites or others (86.9%) (not shown). The most prevalent single risk factor for functional decline was lack regular vigorous physical activity (RVPA), reported by more than 64.2% of this cohort. Lack of RVPA was more frequently reported among women (women: 68.2% versus men: 56.9%) and minorities (African Americans: 73.4%, Hispanics: 69.6% versus Whites/others: 63.0%) compared to their peers (not shown). Almost all these respondents had health insurance, largely through Medicare (93.4%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Arthritis Cohort Age 65 or Older from 1998 Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) Study

| Baseline Characteristics | 1998 Arthritis Cohort n=5715 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Population % | ±95% CI | |

| Demographic Factors | |||

| Hispanic | 337 | 4.51 | 1.41 |

| African American | 737 | 8.57 | 1.45 |

| Non-Hispanic White/Other | 4641 | 86.93 | 1.98 |

| Female | 3625 | 64.19 | 1.70 |

| Married | 3137 | 52.04 | 1.75 |

| Age 65–74 | 2956 | 52.42 | 1.91 |

| 75–84 | 2061 | 37.21 | 1.78 |

| >=85 | 698 | 10.37 | 0.89 |

| Comorbid Health Conditions | |||

| No chonric conditions | 688 | 12.23 | 1.04 |

| Cancer | 859 | 15.13 | 1.04 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | |||

| Heart Disease | 1647 | 28.54 | 1.44 |

| Hypertension | 3242 | 56.37 | 1.17 |

| Stroke | 550 | 9.54 | 0.78 |

| Cognitive impairment | 188 | 2.66 | 0.44 |

| Depressive symptoms | 2321 | 40.30 | 2.03 |

| Diabetes | 1025 | 17.30 | 1.13 |

| Pulmonary Disease | 699 | 12.57 | 1.22 |

| Vision (poor to legally blind) | 484 | 8.16 | 0.95 |

| Weight problem | |||

| Under-weight | 144 | 2.42 | 0.39 |

| Obesity | 1240 | 21.49 | 1.36 |

| Physical Limitation | |||

| Walk Several Blocks | 433 | 7.20 | 1.11 |

| Climb Several Flights of Stairs | 1458 | 24.07 | 2.00 |

| Push/Pull Large Objects | 1007 | 17.28 | 1.38 |

| Lift/Carry Weight >= 10 lbs | 674 | 10.92 | 1.10 |

| Economic Access | |||

| Education < 12 years | 2057 | 33.72 | 1.96 |

| Annual Family Income < lower quartile($16,800) | 2074 | 35.96 | 1.85 |

| Net Worth < lower quartile ($44,800) | 1595 | 26.36 | 1.97 |

| Health Insurance | |||

| Medicare Only | 3088 | 54.87 | 2.40 |

| Private (employer/other) | 1938 | 34.28 | 2.46 |

| Government Only | 623 | 9.95 | 1.15 |

| None/missing | 66 | 0.89 | 0.29 |

| Health Behaviors | |||

| Lack of regular vigorous physical activity | 3797 | 64.20 | 2.03 |

| Current Smoker | 556 | 9.88 | 0.85 |

| Ever Use Alcohol | 2711 | 49.70 | 2.42 |

| Weight Gain over 10 | 836 | 14.67 | 0.97 |

| Weight Loss over 10 pounds | 1110 | 19.11 | 1.23 |

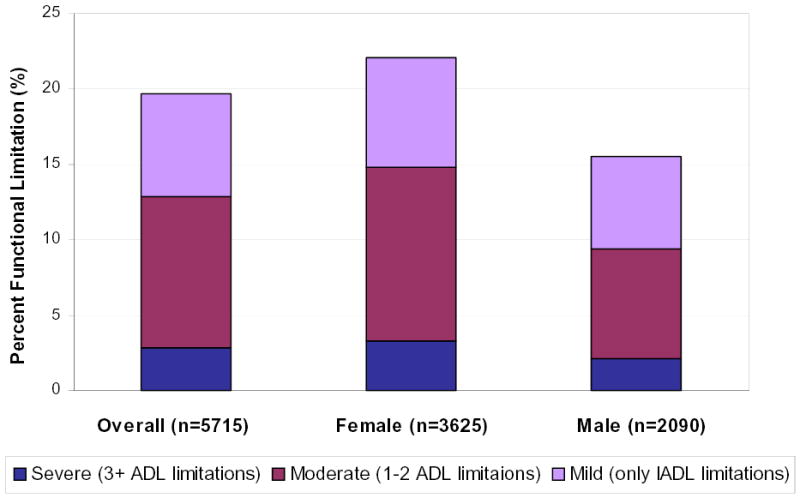

Prevalence of functional limitations in daily tasks is estimated from the 5715 arthritis cohort members. Overall, limitations in functional tasks are reported by 19.7% of the cohort, including 12.9% with at least one ADL limitation, 5.6% had two or more, and 2.9% had 3 or more. Older women (22.0%) are more likely than older men (15.5%) to experience daily task limitations, as shown in Figure 1. More than one in seven women (14.8%) and almost one in ten men (9.4%) with arthritis report limitations in at least one basic ADL task. Severe functional limitations (≥3 ADL limitations) are reported by 3.3% of women and 2.1% of men with arthritis.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Functional Limitation of Arthritis Cohort Aged 65 or older (N=5715) Stratified by Gender from the 1998 Health and Retirement Survey

Decline in function was assessed in 4922 persons without severe baseline functional limitation. Over the subsequent two years, function declined in 13.6% of this group. Table 2 summarizes two-year rates of functional decline by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Functional decline increased with age, as expected, almost doubling in frequency for approximately every additional decade (65–74 years: 8.8%; 75–84 years: 16.8%; 85 years 30.3%). Function declined significantly more frequently in women than men (odds ratio [OR]=1.4, CI=1.2,1.7), a trend that was consistent across age groups. Functional decline was significantly greater among older Hispanics (OR=1.5, CI=1.1, 2.0) and African American (OR=1.6, CI=1.2, 2.0) with arthritis compared to Whites/Others (12.9%).

Table 2.

Rates of Two-Year (1998–2000) Functional Decline by Gender and Age Among 1998 HRS Arthritis Cohort with None-Moderate Baseline Functional Limitation

| Two-Year Functional Decline | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % | 95% CI |

| Male (n=1766) | 11.03 | 9.55, 12.51 |

| 65–74 | 6.96 | 5.42, 8.50 |

| 75–84 | 14.66 | 12.03, 17.28 |

| >=85 | 25.18 | 17.14, 33.21 |

| Female (n=3156) | 14.99 | 13.38, 16.60 |

| 65–74 | 9.79 | 8.24, 11.34 |

| 75–84 | 17.91 | 15.13, 20.69 |

| >=85 | 32.33 | 26.51, 38.16 |

| White/Other (n=4028) | 12.89 | 11.58, 14.21 |

| 65–74 | 7.84 | 6.76, 8.93 |

| 75–84 | 16.12 | 13.90, 18.34 |

| >=85 | 29.93 | 24.96, 34.91 |

| AA (n=611) | 18.67 | 15.07, 22.27 |

| 65–74 | 13.36 | 9.88, 16.83 |

| 75–84 | 24.68 | 17.03, 32.32 |

| >=85 | 31.89 | 21.35, 42.43 |

| Hispanic (n=283) | 18.04 | 14.13, 21.97 |

| 65–74 | 15.56 | 9.56, 21.57 |

| 75–84 | 19.54 | 11.23, 27.86 |

| >=85 | 34.11 | 14.34, 53.88 |

| Total (n=4922) | 13.60 | 12.36, 14.84 |

| 65–74 | 8.75 | 7.71, 9.80 |

| 75–84 | 16.80 | 14.69, 18.90 |

| >=85 | 30.29 | 25.89, 34.70 |

To determine the strongest predictors of functional decline, their relative effect based on an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was estimated to simultaneously control for comorbid health conditions, health behaviors, economic risk factors, and demographic differences (Table 3). Comorbid health conditions that increased the risk of functional decline included cognitive impairment (AOR= 2.9, CI=1.7,4.8), poor vision (AOR=1.6, CI=1.2, 2.2), diabetes (AOR=1.6, CI=1.2, 2.0), a history of stroke (AOR=1.6, CI=1.1, 2.3), depressive symptoms (AOR=1.3, CI=1.1, 1.6), and physical limitation (surrogate for disease severity) in push/pull large objects (AOR=1.3, CI=1.0, 1.6). Significant health behaviors include lack of regular vigorous physical activity (AOR=1.9, CI=1.5, 2.4) and use of alcohol (AOR=0.8, CI=0.6, 0.9). Economic factors were not significant predictors of functional decline in this Medicare-aged population. Many Table 2 demographic differences in functional decline are attenuated after accounting for health and economic factors (Table 3). Specifically, the greater frequencies of functional decline among older women and African-American and Hispanic minorities are largely explained by their greater burden of other risk factors. For example, significant and highly prevalent risk factors including lack of RVP and depressive symptoms were reported substantially more frequently among women (lack of RVPA: 68.3%, depressive symptoms: 44.2%) than men (57.0%, 33.3%) and minorities (72.1%, 55.3%,) than White/others (63.0%, 38.1%). Older age, however, remains a significant risk factor for functional decline that increases with each decade.

Table 3.

Arthritis Cohort: Risk Factor Adjusted Odds Ratio for Two-Year Functional Limitation Decline (n=4922)

| Risk Factors | Logistic Regression Results | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR† | 95% CI | |

| Comorbid Health Conditions | ||

| Cancer | 0.97 | 0.75, 1.25 |

| Cognitive Impairment | 2.86 | 1.71, 4.78 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 1.27 | 1.05, 1.55 |

| Diabetes | 1.55 | 1.21, 1.99 |

| Heart Disease | 1.14 | 0.92, 1.43 |

| Hypertension | 1.15 | 0.99, 1.34 |

| Weight Problem | ||

| Under-weight | 1.40 | 0.75, 2.63 |

| Obesity | 1.27 | 1.00, 1.61 |

| Pulmonary Disease | 1.20 | 0.93, 1.55 |

| Stroke | 1.56 | 1.06, 2.30 |

| Vision (poor or legally blind) | 1.63 | 1.20, 2.20 |

| Physical Limitation | ||

| Walk Several Blocks | 1.16 | 0.89, 1.50 |

| Climb Several Flights of Stairs | 1.11 | 0.89, 1.39 |

| Push/Pull Large Objects | 1.29 | 1.02, 1.64 |

| Lift/Carry Weight >= 10 lbs | 1.24 | 0.89, 1.73 |

| Health Behaviors | ||

| Lack of regular vigorous Physical activity | 1.94 | 1.54, 2.44 |

| Current Smoker | 1.20 | 0.85, 1.70 |

| Ever Use Alcohol | 0.75 | 0.61, 0.92 |

| Weight Gain over 10 pounds | 0.84 | 0.63, 1.13 |

| Weight Loss over 10 pounds | 1.23 | 0.94, 1.60 |

| Weight stable [Reference] | - | - |

| Economic Access | ||

| Education <12 years | 1.07 | 0.83, 1.38 |

| Income < lower quartile | 1.20 | 0.96, 1.51 |

| Net Worth < lower quartile | 1.21 | 0.90, 1.62 |

| Health Insurance | ||

| Medicare only | 1.12 | 0.95, 1.32 |

| Government Only | 0.99 | 0.70, 1.41 |

| None/Missing | 1.25 | 0.57, 2.77 |

| Private [Reference] | - | - |

| Demographic | ||

| Hispanic | 0.92 | 0.65, 1.31 |

| African American | 0.96 | 0.71, 1.31 |

| White/Other [Reference] | - | - |

| Female | 1.04 | 0.84, 1.29 |

| Age 65–74 [Reference] | - | - |

| 75–84 | 1.79 | 1.45, 2.20 |

| 85 or Older | 3.10 | 2.29, 4.19 |

| Not Married | 0.81 | 0.65, 1.01 |

Adjusted odds ratios from a multiple logistic regression model that simultaneously controls for demographics, comorbid conditions, health behaviors, and economic factors. Bolded AOR have associated 95% CI that excludes one, indicating statistical significance at nominal alpha=.05 level.

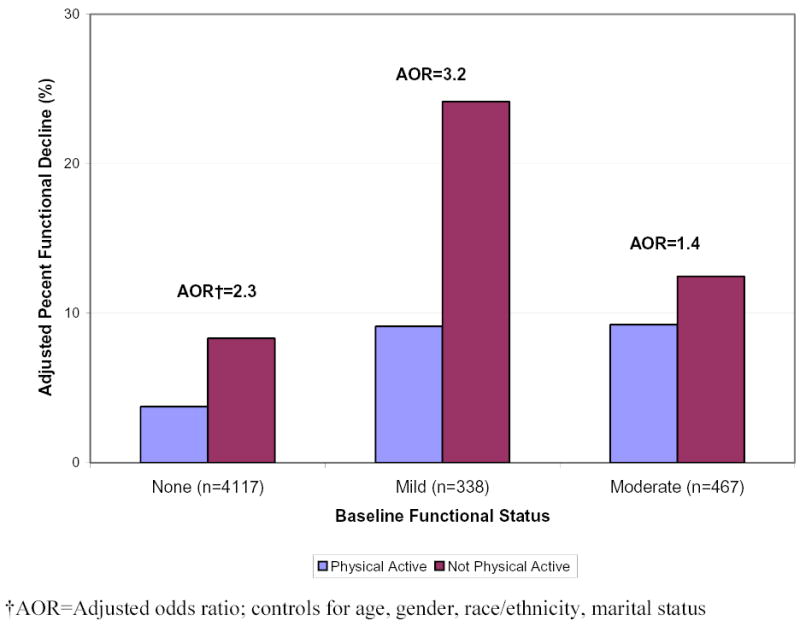

The strong relative effect of lack of regular vigorous physical activity on functional decline is important from a public health perspective since it is a highly prevalent risk factor (64.2%) that is modifiable. Among other health factors, only cognitive impairment, which is true for only 3% of the cohort and less amenable to intervention, has a stronger relative effect on functional decline. To better understand the potential impact from lack of RVPA, Figure 2 explores its effect on functional decline stratified by baseline functional ability for persons with arthritis. Function declined less frequently in persons who engaged in RVPA, regardless of their baseline functional ability. Lack of RVPA was a particularly strong risk factor for persons with none (AOR=2.3, CI=1.8, 3.0) or only mild baseline functional limitation (AOR=3.2, CI= 1.3, 7.6), after adjusting for demographic differences.

Figure 2. Two-Year Functional Decline by Baseline Functional Status of 1998–2000 HRS Arthritis Cohort Aged 65 or Older (n=4922).

Since people with severe health burdens may be unable to do RVPA, we explored whether the report of specific physical limitations (walking several blocks, climbing several flights of stairs without resting, pulling or pushing large objects, lifting or carrying weights over 10 pounds), altered the relationship of lack of RVPA to functional decline. Sensitivity analysis (not shown) added interaction terms between physical activity and individual physical limitations; none of these interactions were significant. Further analyses explored whether RVPA had particular benefit for certain age, gender, or racial/ethnic groups by adding interaction terms between physical activity and demographics to the multiple logistic regression model. None of the interactions from this analysis (not shown) were significant, indicating that lack of RVPA is equally detrimental in vulnerable female and minority populations.

To provide a perspective on the potential benefit from RVPA as a modifiable risk factor, we used standardized rates to estimate how functional decline might be affected if all persons not engaged in RVPA could be persuaded to become active. Overall, the two-year rate of functional decline would be reduced by over one-third, from 13.6% to 9.2%, based on standardized rates with RVPA participation by the entire risk group. Estimated functional decline would be reduced in women from 15.0% to 10.0%; in men from 11.0% to 7.6%; in African Americans from 18.7% to 12.6%; in Hispanics from 18.0% to 12.2%; in White/others from 12.9% to 8.7%.

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence of the substantial national public health burden related to functional limitations among Medicare-aged U.S. adults with arthritis. Nearly one out of every five adults over 65 years with arthritis reported limitations in functional tasks. More than 12% of this cohort reported ADL task limitations; 5.6% had two or more and 2.9% had three or more ADL limitations. This finding represents impressively high prevalence of IADL and ADL limitations among a group of adults whose health care is largely covered by public insurance via Medicare. Among persons at risk of functional decline, over 13% had a lower level of function two years later. Other than cognitive impairment, which was true for only 3% of this population, lack of regular vigorous physical activity was the strongest predictor across the spectrum of comorbid health conditions, health behavior and economic factors examined. The odds of functional decline over two years almost doubled for persons not engaged in RVPA compared to their active peers, controlling for all other risk factors.

The prospect of developing worse levels of function is particularly daunting for older women, African Americans, and Hispanics. Approximately one in eight women and almost one in five African Americans and Hispanics declined in function within two years. Function deteriorated 35% more frequently among women (15.0%) compared to men (11.0%) and 45% more frequently among minorities (African Americans: 18.7%, Hispanics: 18.0%) compared to White/Others (12.9%). The higher rates of functional decline among older women and minorities with arthritis are largely due to greater burdens of health risk factors, such as comorbid chronic conditions and lack of RVPA.

To guide a public health response, we investigated the relative impact of risk factors on functional decline controlling for comorbid health conditions, health behavior, economic, and demographic factors. In addition to lack of RVPA and cognitive impairment which approximately double and triple the odds of functional decline, respectively, other significant predictors of functional decline were age, depressive symptoms, diabetes, physical limitation in push/pull large objects, stroke, and vision impairment, while use of alcohol was protective after controlling for all risk factors. Since frail individuals are characterized by older age and chronic health conditions, these characteristics are consistent with geriatric literature on functional limitation risk factors. 27, 28 Alcohol use has also been shown protective in other population-based studies.29

The strong association of lack of RVPA with subsequent functional deterioration in this national arthritis cohort is particularly important from a public health point of view, since this risk factor is highly prevalent among persons with arthritis and is amenable to intervention. More than 60% of adults with arthritis do not meet the U.S. Surgeon General’s recommendations for physical activity.30 The present study showed that function declined less frequently in older adults with arthritis who engaged in RVPA, regardless of their baseline functional ability. To provide a perspective on the potential public health benefit from physical activity, we estimated the expected 2-year rates of functional decline if all persons in this cohort had engaged in RVPA. Functional decline would have been reduced as much as 32% (from 13.6% to 9.2%). These findings indicate that older persons with chronic conditions need to be encouraged to participate in physical activities, whatever their current capabilities.

Physical activity has been considered a safe, efficacious, and widely advocated method of controlling arthritis disease consequences.31, 32 Clinical studies of specific types of exercise programs demonstrate that physical activity interventions result in improved strength, aerobic capacity, flexibility and physical function in persons with RA,33, 34 OA,35, 36 and sedentary elders in general.37, 38 However, it is worth noting that in each of these clinical studies, very specific training programs were devised to produce the resulting outcomes, requiring professional resources and high motivation level from participants. For example, strength training (all major muscle groups of the lower and upper extremities and trunk, repetitions with loads of 50–70% of maximum) was tested in rheumatoid arthritis, 34 while studies of persons with osteoarthritis utilized an aerobic exercise program and a resistance exercise program, 35 or resistance training without an aerobic component.36 In elders without specific musculoskeletal diagnoses, a specific protocol of combined endurance and strength training was designed to be performed at 75% to 80% of maximal intensity; with the groups meeting 3 times/week for 6 months of supervised sessions.37 The impact of less formalized physical activities on the functional outcomes of persons with arthritis is not known.

Large epidemiologic studies show lack of physical activity to be a risk factor for functional limitation based on longitudinal findings. 29, 39–43 However, these longitudinal studies are largely based on community samples, 29, 39, 41, 42 rely on data from over a decade ago, 29, 39–43 and seldom control for health and economic factors that may partially explain their findings. 29, 39–41, 42 Population-based longitudinal studies among persons with arthritis are particularly limited.43 The present study documents lack of RVPA to be a risk factor for functional decline from the strong methodological platform of longitudinal data from a recent national probability sample that analytically controls for demographic, health, and economic factors. The focus on the experience of an arthritis cohort makes these findings relevant to the design of public health intervention and prevention programs to maintain and improve function among persons with arthritis.

Despite its strengths, several limitations common to secondary databases may affect the present findings. Since baseline factors were assessed cross-sectionally, it is unknown which may be consequences or causes of baseline functional problems (e.g., depressive symptoms). Second, the physical activity assessment does not provide information on the types or levels of activities in which people engaged. Also, people were not asked whether or not they were capable of physical activity. However, the relative impact of lack of RVPA to other risk factors controlled for baseline physical limitations, a surrogate for the severity of health burdens. Also, the risk group used for this risk factor analysis excluded people who initially reported severe (≥3ADL) functional limitations, which bases these findings on people most likely to be capable. Among this risk group, further analyses showed that lack of RVPA was a particularly strong risk factor for functional decline among subgroups with the highest baseline functional capability (none or mild baseline functional limitations). Finally, some of the differences found in our multiple statistical tests could have been due to chance.

Functional limitation is a recognized driver of health care costs.5, 44 Findings from this study show that almost 20% of persons with arthritis have limitations in daily functional tasks in a cohort whose medical expenses are largely covered by Medicare. The burden of functional limitation and subsequent decline in function was greatest among older women and minorities. These findings point to the importance of prevention programs targeted at and tailored to the needs of these vulnerable populations. The good news is that the most prevalent significant risk factor examined and among the strongest predictors of functional decline, lack of RVP, is amenable to prevention efforts. Motivating older persons with arthritis who are not engaged in regular physical activity to change behavior, could reduce subsequent functional decline among these older Americans by almost one-third. RVPA is an important risk factor for all racial/ethnic groups and both genders. Prevention/intervention programs should include regular physical activity, weight maintenance, and medical intervention for health needs.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported in part by funding from NIH/National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases P60-AR48098, and NIH/National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research R01-HD45412. The Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) is sponsored by the National Institute of Aging and conducted by the University of Michigan. This study received exemption from Human Subjects Review by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board for these analyses of public data.

Footnotes

This study was supported in part by funding from NIH/National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases P60-AR48098, and NIH/National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research R01-HD45412.

References

- 1.Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Salive ME. Disability as a public health outcome in the aging population. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:25–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, D.C January 2000.

- 3.VonKorff M, Ormel J, Katon W, Lin EHB. Disability and depression among high utilizers of health care: A longitudinal analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:91–100. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820020011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutler DM. Disability and the future of Medicare. N Engl J Med. 2003 Sep 11;349(11):1084–1085. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe038129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lubitz J, Cai L, Kramarow E, Lentzner H. Health, life expectancy, and health care spending among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003 Sep 11;349(11):1048–1055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults--United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001 Feb 23;50(7):120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of self-reported arthritis or chronic joint symptoms among adults--United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002 Oct 25;51(42):948–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Arthritis prevalence and activity limitations, United States, 1990. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review. 1994;43:433–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health and aging: projected prevalence of self-reported arthritis or chronic joint symptoms among persons aged >65 years--United States, 2005–2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003 May 30;52(21):489–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Bula CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1999 Feb;48(4):445–469. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkisian CA, Liu H, Gutierrez PR, Seeley DG, Cummings SR, Mangione CM. Modifiable risk factors predict functional decline among older women: a prospectively validated clinical prediction tool. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000 Feb;48(2):170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, van Belle G, Kukull WB, Larson EB. Predictors of functional change: a longitudinal study of nondemented people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002 Sep;50(9):1525–1534. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma L, Cahue S, Song J, Hayes K, Pai YC, Dunlop D. Physical functioning over three years in knee osteoarthritis: role of psychosocial, local mechanical, and neuromuscular factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Dec;48(12):3359–3370. doi: 10.1002/art.11420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rejeski WJ, Miller ME, Foy C, Messier S, Rapp S. Self-efficacy and the progression of functional limitations and self-reported disability in older adults with knee pain. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001 Sep;56(5):S261–265. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.5.s261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeringa S, Connor J. Technical description of the Health and Retirement Study Sample Design. HRS Documentation. Ann Arbor, MI:: Population Studies Center; 1995. HRS Documentation Report DR-002.

- 16.Heeringa S. Technical description of the Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) Study Sample Design. Ann Arbor, MI: Population Studies Center; 1995. HRS Documentation Report DR-003.

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adults who have never seen a health-care provider for chronic joint symptoms--United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003 May 9;52(18):416–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. Disability in America: Toward A National Agenda for Prevention Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1991.

- 19.Mor V, Wilcox V, Rakowski W, Hiris J. Functional transitions among the elderly: patterns, predictors, and related hospital use. Am J Public Health. 1994 Aug;84(8):1274–1280. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.8.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stump TE, Clark DO, Johnson RJ, Wolinsky FD. The structure of health status among Hispanic, African American, and white older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. May 1997;52 Spec No:49–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Herzog AR, Wallace RB. Measures of cognitive functioning in the AHEAD Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. May 1997;52 Spec No:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW., Jr Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1999 Oct 7;341(15):1097–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith JP. Wealth inequality among older Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. May 1997;52 Spec No:74–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Health and Retirement Study. Sampling Weights Revised for Tracker 2.0 and Beyond. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Survey Research Center; 2002.

- 25.Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS. SUDAAN User's Manual Release 7.5 Research Triangle Park, NC:: Research Triangle Institute; 1997.

- 26.Korn EL, Graubard, B.I. Analysis of Health Surveys New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1999.

- 27.Sands LP, Yaffe K, Lui LY, Stewart A, Eng C, Covinsky K. The effects of acute illness on ADL decline over 1 year in frail older adults with and without cognitive impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002 Jul;57(7):M449–454. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.7.m449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin APMJ, Dekker JM, Feskens EJ, Schouten EG, Kromhout D. How to select a frail elderly population? A comparison of three working definitions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999 Nov;52(11):1015–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, van Eijk JT, Guralnik JM. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1999 Sep;89(9):1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontaine KR, Heo M, Bathon J. Are US adults with arthritis meeting public health recommendations for physical activity? Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Feb;50(2):624–628. doi: 10.1002/art.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jette AM, Keysor JJ. Disability models: implications for arthritis exercise and physical activity interventions. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Feb 15;49(1):114–120. doi: 10.1002/art.10909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Ende CH, Breedveld FC, le Cessie S, Dijkmans BA, de Mug AW, Hazes JM. Effect of intensive exercise on patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000 Aug;59(8):615–621. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.8.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hakkinen A, Sokka T, Lietsalmi AM, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P. Effects of dynamic strength training on physical function, Valpar 9 work sample test, and working capacity in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Feb 15;49(1):71–77. doi: 10.1002/art.10902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hakkinen A, Sokka T, Kotaniemi A, Hannonen P. A randomized two-year study of the effects of dynamic strength training on muscle strength, disease activity, functional capacity, and bone mineral density in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2001. 2001;44(3):515–522. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200103)44:3<515::AID-ANR98>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ettinger WH, Jr, Burns R, Messier SP, et al. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST) Jama. 1997 Jan 1;277(1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Topp R, Woolley S, Hornyak J, 3rd, Khuder S, Kahaleh B. The effect of dynamic versus isometric resistance training on pain and functioning among adults with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002 Sep;83(9):1187–1195. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cress ME, Buchner DM, Questad KA, Esselman PC, deLateur BJ, Schwartz RS. Exercise: effects on physical functional performance in independent older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999 May;54(5):M242–248. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.5.m242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keysor JJ, Jette AM. Have we oversold the benefit of late-life exercise? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001 Jul;56(7):M412–423. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.7.m412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leveille SG, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Langlois JA. Aging successfully until death in old age: opportunities for increasing active life expectancy. Am J Epidemiol. 1999 Apr 1;149(7):654–664. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller ME, Rejeski WJ, Reboussin BA, Ten Have TR, Ettinger WH. Physical activity, functional limitations, and disability in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000 Oct;48(10):1264–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gregg EW, Mangione CM, Cauley JA, et al. Diabetes and incidence of functional disability in older women. Diabetes Care. 2002 Jan;25(1):61–67. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tager IB, Haight T, Sternfeld B, Yu Z, van Der Laan M. Effects of physical activity and body composition on functional limitation in the elderly: application of the marginal structural model. Epidemiology. 2004 Jul;15(4):479–493. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000128401.55545.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Yelin EH, Song J, Chang RW. The cost of arthritis (Invited paper) Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Feb 15;49(1):101–113. doi: 10.1002/art.10913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Culler SD, Callahan CM, Wolinsky FD. Predicting hospital costs among older decedents over time. Med Care. 1995 Nov;33(11):1089–1105. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]