ABSTRACT

Mechanobiology studies how mechanical forces influence biological processes at different scales, both in homeostasis and in pathology. Organoids, 3D structures derived from stem cells, are particularly relevant tools for modeling tissues and organs in vitro. They currently constitute one of the most suitable models for mechanobiology studies. This review provides an overview of existing or applicable approaches to organoids for mechanical studies. We first present the different types of culture supports, including hydrogels and organ‐on‐chip. We then discuss advanced imaging techniques, particularly suitable for studying the physical properties of cells, allowing the visualization of mechanical forces and cellular responses. We also describe the approaches and tools available to observe the organoids by microscopy. Finally, we present analytical methods, including computational models and biophysical measurement approaches, which facilitate the quantification of mechanical interactions. This review aims to provide the most comprehensive overview possible of the methods, instrumentations, and tools available to conduct a mechanobiological study on organoids.

Keywords: imaging analysis, mechanobiology, microscopy, organoids

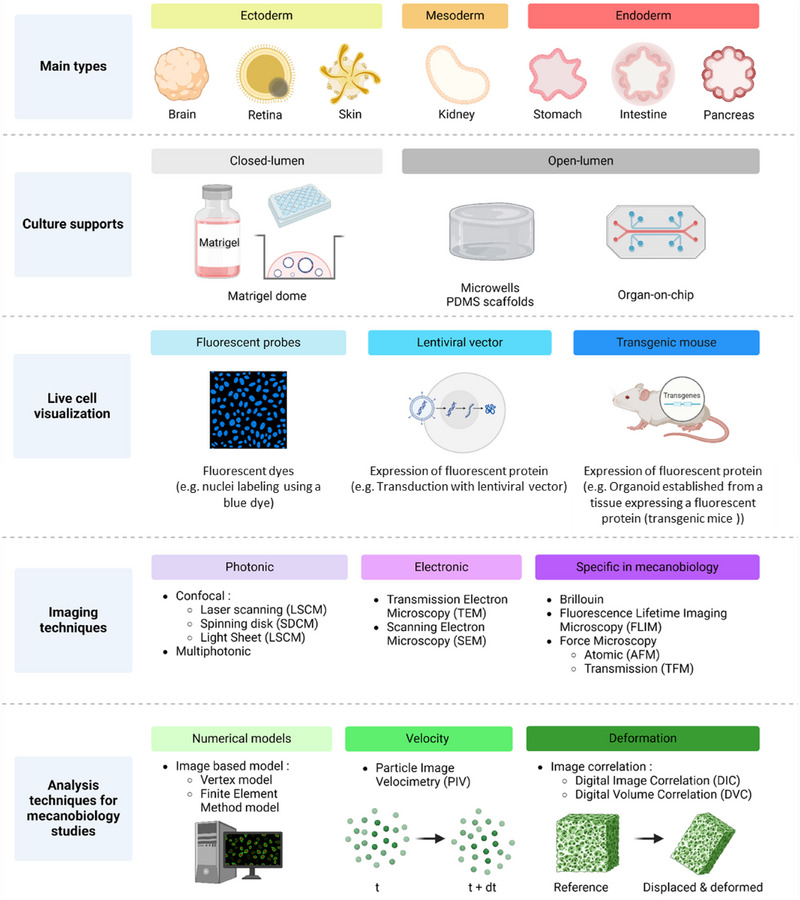

Mechanical forces can influence biological processes in both healthy and pathological contexts. Organoids are 3D structures derived from stem cells that can be used to model tissues and organs in vitro. The objective of this review is to present the different ways to culture and observe organoids under a microscope to study mechanical interactions in different tissues. We also present analytical methods, such as computational models, applicable to organoids. Created in BioRender. HAMEL, D. (2025) https://BioRender.com/xlfs16s.

1. Introduction

Mechanobiology is a relatively new field of study that focuses on how mechanical forces influence biological processes at the cellular and tissue level. In other words, it seeks to understand how cells use, detect, and respond to mechanical signals (Nelson et al. 2024). These stimuli can be of a different nature depending on the tissue considered, but among the most frequent in vivo are pressure, tension, or stiffness of the substrate. These mechanical constraints can also influence essential biological functions such as proliferation, migration, differentiation, and morphogenesis (Miller et al. 2020).

In recent years, mechanobiology has become an increasingly popular topic of study, as the crucial role of mechanics in organ homeostasis and pathology has become evident. Indeed, if physical constraints are important and necessary for the morphogenesis of many tissues and their proper functioning, they are also involved in regeneration and healing processes (Vining and Mooney 2017). From a pathological perspective, as in the case of cancer, for example, it is known that the stiffness and mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in which cancer cells develop can influence the process of invasion and metastasis (Vasudevan et al. 2023).

To effectively study mechanobiology, selection of an appropriate model is crucial. Biological models, whether in vivo, in vitro, or ex vivo, have evolved considerably over time and continue to progress, providing valuable information on living processes in various species, particularly on aspects of physio(patho)logy. In addition, as mentioned previously, understanding the mechanical interactions within a tissue or between the tissue and its matrix environment is essential to decipher their functions and dysfunctions. To achieve this, it is not only necessary to choose a relevant biological model but also to integrate suitable imaging and analysis techniques. Increasingly sophisticated biological models have been developed in recent years, including organoids.

By definition, an organoid is a 3D biological structure, derived from pluri‐ or multi‐potent stem cells (SC), capable of self‐assembly and reproducing the architecture and at least one function of the tissue of the organ of origin of the stem cells. These cells, mainly adult stem cells, but possibly also embryonic stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells, are cultured in 3D in a hydrogel, generally Matrigel (Rahman et al. 2021), supplemented with factors necessary for their development. The culture relies on the renewal properties and the differentiation capacity of active SCs present in the tissue of origin to multiply and self‐organize into 3D structures. One of the many advantages of this model is the rapid production of mature structures (around 10–15 days for intestinal organoids), thus not requiring protocols as long as those using animal models. This type of culture can be established from a sample of normal tissue from a patient, but also from cells from a tumoral (tumoroids) or inflammatory area. In addition, it is possible to create biobanks of organoids established from tissues from different patients, representative of different types of pathologies. This makes it a very useful tool for preclinical studies but also for the study of mechanical changes that can occur in the event of pathology (Perrone and Zilbauer 2021). Furthermore, the organoid model offers a very important feature for the study of mechanical interactions between tissue and its matrix environment, since the matrix is easily accessible. This means it can be modified and studied, using the addition of beads, for example (Magne et al. 2024). In the context of mechanobiology studies, organoids represent a model of choice, and in particular colonic epithelial organoids. This continuous monolayer of polarized epithelial cells, where invaginations called “crypts” and plateaus face the intestinal lumen, is subjected to numerous constraints, such as traction or intercellular tension (Pérez‐González et al. 2022). In the same idea, organoids of different organs can be cultured to study the mechanical constraints they undergo in their environment. Organoids used in organs‐on‐chip also provide a significant advantage as they allow the study of the application of external forces, such as peristalsis and shear stress, to mimic the in vivo environment and analyze how these conditions influence cellular behavior. Finally, as detailed below, the variety of imaging techniques that can be applied to organoids, including living (as opposed to fixed) ones, constitutes a real argument in favor of their use in mechanobiological studies.

In this review, we will list the different possible supports for organoid culture, as well as the different imaging and analysis techniques that can be implemented in the context of mechanobiology studies (Figure 1). Indeed, the type of support, microscope, and analyses must be chosen according to the data that we wish to obtain and the question asked. Thus, each technique cited will be explained, with its advantages, its disadvantages but especially with the data that it allows to obtain or the cases where it is applicable.

Figure 1.

Overview of different options for studying organoid mechanobiology. The main culture supports, cell labeling options, imaging techniques, and analysis methods that can be used in organoid mechanobiology studies are shown schematically, and explained in more detail in the text. Created in BioRender. HAMEL, D. (2025) https://BioRender.com/g28p111.

1.1. Organoid Culture Systems

Depending on the study, organoids can be cultured using different supports. Most of the time, they are seeded in Matrigel and grown in 3D. Epithelial organoids growing in 3D while creating a lumen are called “closed‐lumen organoids”. It is also possible to partially dissociate these structures to culture them on a 2D scaffold, such as, for example, a PDMS scaffold coated with biocompatible proteins ensuring cell adhesion (collagen, laminin …). These 2D cultures are then called “2D organoids monolayers” or “open‐lumen organoids” (Pérez‐González et al. 2022). To faithfully reproduce the in vivo ECM of the epithelium, particularly in terms of stiffness and topography, different systems can be used, ranging from simple models, such as 2D cultures, to more complex configurations, such as microphysiological systems (MPS; or organ‐on‐chip).

Intestinal organoids are a valuable asset for mechanobiology studies, particularly studies on the intrinsic constraints of epithelia. These constraints are an integral part of tissue homeostasis. They are found in tissue morphogenesis, proliferation, differentiation, migration, or cell extrusion. For example, the cytoskeleton of cells of murine intestinal organoid plated as open‐lumen organoid on a 2D substrate drives the folding of intestinal crypts after actomyosin accumulation at the apical surface of the cells (Pérez‐González et al. 2021). Crypt cells also maintain an apical enrichment of actomyosin even after the end of morphogenesis, which is necessary for crypt maintenance. These results are supported by Yang et al. who showed that organoids cultured in 3D in Matrigel spontaneously break their spherical symmetry and generate crypt‐like structures by apical constriction (Yang et al. 2021). They also confirm those from Sumigray et al. on the morphogenesis and compartmentalization of the intestinal crypt in vivo (Sumigray et al. 2018). In this way, intestinal organoids cannot only reproduce biological observations made in histology, but also allow these events to be studied from a mechanical point of view.

Taking the example of the intestinal epithelium, we have seen that certain processes inherent to the proper functioning of the tissue generate intrinsic constraints (i.e., from the tissue itself). However, organoid culture is also used in studies on extrinsic constraints of tissues. Indeed, the intestinal epithelium undergoes external (or extrinsic) constraints that occur at the organ level (peristalsis, shear stress). For example, it has made it possible to highlight the capacity of murine epithelial cells to self‐organize as in vivo. Indeed, by imposing a physiological topology on mouse intestinal stem cells (ISCs) using PEG hydrogels coated with RGD peptides or laminin‐1, the cell culture colonizes the scaffold and cells differentiate according to a specific distribution: intestinal SCs are found at the bottom of the crypt while differentiated cells are found in the upper compartment, perfectly reproducing the in vivo cell distribution (Gjorevski et al. 2022). Microwell systems also allow the topology of the matrix to be varied, in particular its curvature, to study its effect on cells (Luciano et al. 2021; Pentinmikko et al. 2022). By using PDMS molds to shape collagen culture scaffolds on which open‐lumen organoids are cultured, Pentinmikko et al. demonstrated that lower scaffold curvature is associated with a decrease in the number of stem cells capable of proliferating, highlighting the existence of an optimal curvature for the maintenance of intestinal SC (Pentinmikko et al. 2022). In addition to guiding cellular self‐organization, it has been shown that tissue shape can be associated with cell shape: for example, the conical shape of ISCs facilitates their self‐renewal and stem function when cultured on collagen scaffolds (Pentinmikko et al. 2022). Furthermore, inhibition of apical constriction of ISCs is associated with a reduction in crypt curvature but also in their stem cell capacity. This last point raises the importance of tissue topology in intestinal homeostasis and highlights the existence of an optimal curvature necessary for the maintenance of ISCs.

In vitro, two studies have shown that the development of cultures from intestinal epithelial organoids seeded on scaffolds of different stiffnesses, consisting of polyacrylamide coated with collagen I and laminin I, is conditioned by the mechanical properties of the scaffold which also participate in cellular compartmentalization (Gjorevski et al. 2016; Pérez‐González et al. 2021). The first study shows that the expansion of ISCs is favored on scaffolds of 1.7 kPa compared to those of 0.3 kPa, the scaffold must have a minimum stiffness to obtain a better culture development (Gjorevski et al. 2016). The second, carried out on a range of scaffold stiffness from 0.2 to 15 kPa also shows that the number of murine intestinal stem decreases as the stiffness of the scaffold increases (Pérez‐González et al. 2021). However, more recent study, still using murine intestinal organoids, has provided new insights into the interaction between scaffold stiffness and ISC populations. A study aimed at investigating the impact of matrix stiffening, as observed in an inflammatory context, on the fate and function of ISCs, demonstrated that an increase in substrate stiffness reduced the proliferative LGR5+ cells population. In contrast, cells expressing OLFM4, another stem cell marker, became predominant in the crypts and invaded the regions corresponding to the villi (He et al. 2023). Moreover, substrate stiffness may influence cell fate since its stiffening led ISCs to preferentially differentiate into goblet cells.

More recently, a microfluidic model with a hydrogel scaffold composed of a mixture of collagen I and matrigel made it possible to reproduce a topology close to colonic crypts but also fluidic control at the luminal level (Nikolaev et al. 2020). This colon‐on‐chip, seeded with murine organoids, allowed to re‐establish ISC/differentiated cell compartmentalization (including certain cell types rarely found within organoids such as tuft cells), but also co‐culture with stromal cells for the study of epithelium–stroma interactions. Initially used with murine organoids, the authors very recently succeeded in culturing human primary cells using this device, thus further increasing the pre‐clinical relevance of the system (Mitrofanova et al. 2024). This colon‐on‐chip has notably been used to study tumorigenesis in vitro (Lorenzo‐Martín et al. 2024). The formed tumors can be followed in real‐time, at single‐cell resolution, for several weeks. This model represents an important advance for the study of colonic oncogenesis since until now, the available in vitro models did not allow real‐time access to the tumor development process, particularly in terms of tissue architecture.

Colon‐on‐chip allows the study of shear stress and peristalsis, the main extrinsic constraints on the colonic epithelium. Indeed, it has been shown that cell patches detach from their collagen scaffold if they are cultured in static conditions, while no detachment is observed when the cells are subjected to luminal flow (Verhulsel et al. 2021). This study therefore shows that shear stress improves the maintenance of the epithelial monolayer. Interestingly, murine intestinal organoids have also demonstrated that luminal flow is essential for villi formation (Sugimoto et al. 2021). In addition, Fang et al. recently developed a system allowing to apply cyclic contractions whose amplitude and rhythm are controlled (Fang et al. 2021) leading to an improvement of Lgr5, a stem cell marker, and Ki67, a cell proliferation marker, expressions demonstrating the importance of considering mechanical stimuli mimicking the physiological environment when using in vitro models.

1.2. Techniques for Labeling Living Organoids

To observe organoids by microscopy, it is essential to choose a protocol that enables them to be visualized, generally in fluorescence (Figure 1). In mechanobiology, we are mainly interested in the real‐time observation of living cells and their environment. Concerning cells, it is therefore necessary to choose a technique that will allow them to be analyzed alive over the long‐term. When they are cultivated in 3D in Matrigel, labeling organoids before microscopic observation represents a major technical challenge. Unlike 2D cultures, these 3D structures pose specific difficulties due to their high cell density, their variable size, and their architectural organization. Consequently, efficient labeling requires the homogeneous penetration of markers, such as antibodies or probes, which can be hampered by the surrounding matrix or the epithelial barrier. Furthermore, in the case of fixed organoids, it is essential to preserve their integrity and minimize morphological disturbances during the fixation, permeabilization, and labeling steps. Although the use of fluorescent probes is the simplest technique to implement, particularly on human organoids, other approaches such as lentiviral transduction or generation of transgenic mice can also be employed (Figure 1).

1.2.1. Fluorescent Probes

Fluorescent probes are molecules that can emit light, visible as fluorescence when excited by specific wavelengths of light (Fluorescent probes—Latest research and news | Nature s. d.). They are often used to label specific structures or molecules inside organoid cells. Among the most useful in mechanobiology are probes that can assess cellular morphological parameters, for example, by visualizing cell membranes, nuclei, or the cytoskeleton. Some of the most commonly used probes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of the main fluorescent probes that could be used in mechanobiology studies on organoids.

| Probe | Supplier | Wavelength (Excitation in nm) | Principle | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membranes | CellMask Membrane | Invitrogen | 522, 554, 649 | Amphipathic molecules with a lipophilic moiety (loading the membrane) and a hydrophilic dye (anchoring the probe to the membrane) |

Preserved after formaldehyde fixation Specific and rapid staining of the membrane Staining between 60 and 90 min Not preserved after cell permeabilization |

| CellBrite | Biotium | 366, 484, 549, 644 | Accumulation in the membrane and covalent binding to membrane proteins |

Resist to fixation and permeabilization Very specific with low background, Long lasting labeling (24–72 h) |

|

| BioTracker Cytoplasmic Membrane | SigmaAldrich | 366, 484, 549, 644 | Lipophilic membrane dye of the carbocyanine type: intercalates into the lipid bilayer where it fluoresces intensely |

Very stable Low toxicity Resist to fixation but permeabilization may alter the repartition of the probe |

|

| Nuclei | Hoechst | Multiple | 350 | DNA intercalating agent |

Risk of cytotoxicity On live or fixed cells |

| Spy‐DNA | Spirochrome | 505, 555, 595, 620, 650, 700 | SPY technology, no more information from the supplier |

High specificity Low background On living or fixed cells |

|

| BioTracker Nuclear | SigmaAldrich | 500, 650 | Fluorescent DNA dye capable of crossing membranes that specifically stains the nucleus |

On living or fixed cells Important photostability Exhibit blue fluorescence in “DAPI” channel: not suitable for imaging with blue probes Use with verapamil, an efflux pump inhibitor to improve probe retention |

|

| Actin/Fast‐Actin | Spy‐Actin | Spirochrome | 555, 620 | SPY technology, no more information from the supplier |

High specificity Low background On living or fixed cells |

| Spy‐FastAct | Spirochrome | 555, 650, 700 | SPY technology, no more information from the supplier |

High specificity Low background On living and fixed cells |

|

| CellMask Actin | Invitrogen | 503, 545, 652 | Staining of F‐actin in living or fixed cells without staining G‐Actin by using a targeting molecule that resembles Jasplakinolide (inductor of actin polymerization) |

Follow‐up for 24 h or more On living or fixed cells |

|

| Tubulin | BioTracker Microtubule | SigmaAldrich | 500 | Cell‐permeable, Taxol‐based probe for imaging microtubules in living cells |

Only for living cells Does not resist to fixation Use with verapamil, an efflux pump inhibitor to improve probe retention |

| Spy‐Tubulin | Spirochrome | 555, 650, 700 | SPY technology, no more information from the supplier |

High specificity Low background On living or fixed cells |

|

| Intermediate filaments | BioTracker Vimentin | SigmaAldrich | 553 | Vimentin labeling, particularly tumor‐initiating cells | Only on living cells |

The use of this type of marker has both advantages and disadvantages. This technique is one of the easiest to implement, since most probes simply need to be added to the culture medium a few hours before image acquisition according to the technical datasheet. They therefore generally do not require any specific sample preparation, and can be used for monitoring from a few hours to a few days. However, some are not suitable for long‐term use, due to the rejection of the probe by the cell or loss of fluorescence during successive illuminations. Moreover, although more and more probes are available on the market, the proteins or structural elements that can currently be labeled using this approach remain limited. Indeed, for example, there is currently no probe of this type that can visualize integrins, key proteins in mechanical interactions between cells and their ECM, or YAP proteins, a very important relay in mechanotransduction signals.

1.2.2. Lentiviral Vectors

Lentiviral vectors are viral vectors derived from lentiviruses, used to deliver genetic material into cells in a stable, long‐lasting manner. They come from the retrovirus family and are used to integrate a gene of interest into the genome of a cell (Tiscornia et al. 2006). Functionally, the lentivirus is modified to be non‐pathogenic, and contains a DNA sequence comprising a gene of interest and a fluorescent marker. Once the virus infects a cell of the organoid, it integrates the genetic material into the genome of the cell, allowing continuous and stable expression of the gene and the associated fluorophore over time, and therefore its visualization. Although relatively few studies have reported the use of this technique on organoids, a number of protocols have been published in recent years to facilitate its implementation, notably in intestinal, liver, and breast organoids (Dekkers et al. 2021; Lian et al. 2022; Lin et al. 2022; Van Lidth de Jeude et al. 2015).

As with any technique, the use of lentiviral vectors has both advantages and limitations. Indeed, this method is particularly useful for permanent labeling, if the virus infects a stem or progenitor cell, allowing all daughter cells to also express the introduced marker. This makes it a technique of choice for long‐term imaging. In particular, since organoids are derived from stem cells, several generations of organoid can express the gene of interest with its fluorescent reporter from a single infection. Moreover, lentiviral vectors can be designed to express a wide variety of genes, making it possible to visualize proteins or cellular elements in living cells that cannot be labeled using the probes mentioned above. However, while their use allows for stable integration of the gene into the recipient cells, the construction of a lentiviral vector remains a complex process, aiming at modifying a virus in order to introduce a gene of interest into host cells without causing pathogenic infections and altering cellular function if this is not desired. Indeed, the generation of lentiviral particles requires several complex steps, which can make the procedure relatively expensive and time‐consuming even if new, simpler protocols are emerging (Soldi et al. 2020). Additionally, the lentiviral vector has a limited capacity in terms of the size of the gene that can be inserted (typically between 8 and 10 kB) (Kalidasan et al. 2021), which may be a limitation for applications requiring larger genes. Finally, although lentiviral vectors are modified to be non‐pathogenic, their handling requires specific biosafety facilities, which may limit their use in some laboratories.

1.2.3. Transgenic Mice

In studies using organoids generated from tissues of animal models, particularly mice, one of the preferred solutions is often the use of transgenic mice. These mice are genetically modified to produce the protein of interest coupled to a fluorescent reporter, typically GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein), mCherry, or tdTomato (Abe and Fujimori 2013). This involves inserting the fluorophore gene directly into the mouse genome, coupled to the gene of interest. In this way, the protein to be visualized is produced by being coupled to the chosen fluorescent protein, and can be observed using a fluorescence microscope (Serra et al. 2019). Organoids grown from transgenic mouse cells express the same fluorescent proteins, which allows them to be monitored over the long term in real‐time without requiring additional labeling.

One of the main advantages of this technique is that it does not require any additional labeling protocol on the organoids. In addition, the expression of GFP, mCherry, or other markers is stable throughout the life of the cell, and will be transmitted to daughter cells after cell division, enabling studies over several generations of organoids. As with lentiviral vectors, the production of transgenic mice allows the fluorescent protein to be coupled to any protein, for example, cytoskeletal elements that cannot be visualized using probes (Yang et al. 2021). However, this method involves creating transgenic mice, which is a time‐consuming and expensive process.

1.3. Imaging Tools

Different tools are needed to gather information on the mechanical interplays between the epithelium and its matrix, the first being the choice of an observation system that is both technically adapted and in line with the biological question addressed. Imaging organoids presents several technical and methodological challenges due to their structural and functional complexity. Their dense three‐dimensional architecture can limit light penetration, reducing the efficiency of traditional 2D imaging techniques. Additionally, the variability between organoids within the same culture (e.g., size and maturation state) complicates the acquisition of standardized data. Furthermore, it is essential to develop non‐invasive imaging techniques to preserve their viability and biological dynamics while ensuring accurate and reproducible quantitative data. Existing imaging techniques are numerous, ranging from photonic microscopy to electron microscopy and local probe microscopy (Table 2). In particular, mechanobiology is interested in dynamic processes that evolve over time. Therefore, the most suitable techniques are those that can be applied to living cells and allow monitoring over time, as we will see below. However, visualization of the architecture of fixed organoids may be necessary, which is why techniques applicable only to fixed cells will also be mentioned in this review. The main imaging techniques used for mechanobiology on organoid models are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of the main imaging techniques used for mechanobiology on organoid models.

| Microscopy technique | Obtained data | Imaging of living cells | User‐friendly sample preparation | 3D acquisition speed | Advantages in organoids imaging | Limitations in organoids imaging |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Scanning Confocal (LSCM) | High‐resolution fluorescence images, in 3D | Yes | + | — | Present in most laboratories, easy to access, good resolution | Slow to image large volumes, possible phototoxicity |

| Spinning Disk Confocal (SDCM) | + | + | Fast, suitable for real‐time imaging | Requires long working distance objectives to image in depth | ||

| Light Sheet Microscopy (LSFM) | –/+ | ++ | Very fast, full 3D volumetric imaging, isotropic voxels | Lower resolution, complex installation | ||

| Multiphotonic | Deep fluorescence imaging in thick tissue | –/+ | — | Excellent penetration, low phototoxicity | Slow acquisition, lower resolution | |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Ultra‐detailed images of internal structures | No | — | — | Ultra‐high resolution for fine, structural details | No live cell imaging, complex and time‐consuming sample preparation |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Details of topography and surface composition | — | –/+ | High‐resolution surface details | No volumetric or live imaging, complex sample preparation | |

| Brillouin Microscopy | Mechanical properties of tissues and cells (elasticity) | Yes | –/+ | –/+ | Measuring the mechanical and physical properties of living organoids | Limited resolution, lack of structural details |

| Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) | Information on fluorescence lifetime, reflecting, for example, membrane tension | + | –/+ | Information on molecular interactions in organoids | Slow acquisition, specific probes, long image processing before analysis | |

| Force Microscopy Atomic (AFM) | 3D atomic‐scale topography, mechanical properties | No | — | NA | Nanometric details of organoid surface structures | No imaging of internal volumes, slow acquisition |

| Traction Force Microscopy (TFM) | Forces exerted by cells on their substrate | Yes | –/+ | Analysis of mechanical forces | Limited resolution for structural details, requires a microscope with a high acquisition frequency |

Note: The main technical features are shown, along with the inherent specificities of each system, as well as the main advantages and disadvantages.

1.3.1. Study of Dynamic Processes in Organoids

The study of dynamic mechanical interactions within the organoid or between it and its ECM requires the use of living cells, increasing the complexity of the imaging process. Indeed, this involves the use of a non‐destructive microscope, where the temperature and CO2 concentration can be controlled, and whose phototoxicity is limited. In order to observe living organoids and visualize biological processes and/or mechanical interactions in real‐time, photonic imaging is then particularly suitable and therefore used. Depending on the type of microscope chosen, it is indeed possible to obtain images with good resolution (<1 µm), but also with a significant penetration depth (several hundred µm). The speed of acquisition is also a key factor in order to study different biological processes or mechanical interactions in live.

The most commonly used microscopes to visualize organoids are fluorescence microscopes. This type of device uses a given wavelength as a light source to irradiate the sample in order to make it emit fluorescence. The wavelengths commonly used cover the entire visible range as well as the infrared domain. This type of acquisition allows for qualitative and quantitative analysis of signals, and offers a spatial resolution of several tens to hundreds of nanometers (Sanderson et al. 2014). One of the major limitations in the use of fluorescence microscopes is the risk of photobleaching and phototoxicity (Fei et al. 2022). Fluorescence microscopy is broken down into different techniques, including confocal microscopy (Meng et al. 2022; Zheng et al. 2023) and multiphoton microscopy (Schafer et al. 2023), which is particularly widespread in organoid imaging.

Multiphoton microscopy uses pulsed infrared laser sources, which emit more than one photon at a time, usually two (two‐photon microscopes), of low energy, to excite fluorophores. The combined energy of these different photons is necessary to raise an electron to the excited state. This type of device is particularly interesting for 3D imaging of organoids because infrared light offers greater penetration than visible light in the sample, up to 1 mm. Multiphoton excitation has precise localization characteristics, which means that only photons arriving at the focal point can excite the fluorophores. The risks of phototoxicity and photobleaching are much reduced with this type of acquisition and are only likely to occur in the vicinity of the focal point. However, like most systems, multiphoton microscopes have limitations, in particular the image acquisition time, which is often extremely long and therefore incompatible with a high acquisition frequency necessary for monitoring biological events. In addition, the emission spectra of fluorochromes are often more spread out in multiphoton illumination than in single‐photon excitation, which allows several fluorochromes to be excited simultaneously by a single wavelength. This spread of the emission spectra poses a problem of specificity of the emissions and can therefore lead to interpretation problems.

A confocal microscope has the particularity, compared to conventional optical microscopes, of producing low depth of field images called “optical sections” that can be taken at different depths in the sample by positioning the focal plane of the objective at these different depths, allowing, after image processing, a 3D representation of the observed sample (Nwaneshiudu et al. 2012). Among the confocal microscopes, we find the laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM), widely used for imaging organoids (Fei et al. 2022; Gjorevski et al. 2022; Yavitt et al. 2023). As its name suggests, optical sections are obtained by scanning the sample point by point with a laser beam. Its penetration depth, of around a hundred micrometers, allows the acquisition of small organoids in their entirety in 3D. By analyzing the images thus obtained, various parameters can be quantified, such as signal intensity, cell shape, and distribution of cell types or the number of dividing cells. Although LSCMs are theoretically compatible with live and time‐lapse image acquisition, this technology uses a very small laser beam to illuminate the image point by point and line by line through a single pinhole, which results in a long acquisition time incompatible with the live monitoring of biological processes such as mitosis, in addition to increasing the risk of phototoxicity.

In response to this technical limitation, spinning disk confocal microscopes (SDCM) are frequently used in organoid model studies (Pérez‐González et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2021). The principle of SDCM microscopy consists of placing a Nipkow disk on the optical plane of the object, on which several pinholes are arranged in a helix. In this case, the laser light source covers all the pinholes in a single pass (Oreopoulos et al. 2014). The complete scanning of the sample is achieved by high‐speed rotation of the disk (up to 10,000 rpm) during which the pinholes are all scanned (Stehbens et al. 2012). The use of a rotating disk greatly reduces the image acquisition speed, with a theoretical acquisition rate of up to 2000 images/s (Fei et al. 2022). The main disadvantage of SDCM technology is the crosstalk effect: part of the emitted light is transmitted to the camera through adjacent pinholes, which can result in a slightly blurrier signal than with a single pinhole, and therefore slightly affect the image resolution. Since SDCM are much faster to acquire and less phototoxic, they are perfectly suited for the acquisition of 3D images of organoids, including in time‐lapse: we can then speak of 4D (or 3D + time) imaging. It is then possible to follow in real‐time the course of certain biological phenomena, such as apoptosis, cell migration, and mitosis, particularly from a mechanical point of view.

Finally, a final imaging technique suitable for visualizing organoids has been in full development in recent years: light sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) (de Medeiros et al. 2022; Serra et al. 2019). In this type of device, the light that illuminates the sample is a very thin sheet of light (a few micrometers), oriented orthogonally to the detection objective, which limits phototoxicity (Stelzer et al. 2021). Moving the object in this sheet of light allows optical sections to be made at all depths of the sample, thus allowing it to be observed it in its entirety. With LSFM, the imaged object can be moved or rotated to make optical sections at different angles and depths in order to obtain a complete 3D image. However, LSFMs also have some limitations, the main one being the complex sample assembly of the sample (Fei et al. 2022). Indeed, LSFM requires samples to be completely clean. For example, obstacles such as bubbles or cellular waste can induce shadows on the illumination path and prevent good acquisition. It should also be noted that to benefit from the advantages offered by the different types of microscopes mentioned, some teams are working to develop protocols combining several microscopy approaches, for example, with the development of a new multiphoton microscope using the illumination principle of light sheet microscopes used to image brain organoids (Rakotoson et al. 2019).

1.3.2. Electron Microscopy

All the techniques mentioned for imaging living organoids are applicable to fixed organoids, in an even simpler manner since phototoxicity is not to be taken into account and in this type of imaging, time constraints are not dictated by the speed of the biological processes to be studied (Dekkers et al. 2019; Lallemant et al. 2020). Conversely, electron microscopy can only be used on fixed biological objects. Electron microscopy, whether scanning or transmission, uses an electron beam to illuminate a sample and allows very high magnifications to be obtained, up to 2 million times the size of the sample observed. The preparation of the sample is very specific, contributing to the fact that few studies use this imaging technique on organoids. However, we can cite the development of an approach combining several imaging techniques at several scales on organoids, including electron microscopy. This study, aimed at developing a protocol for preparing and imaging 3D samples, shows good preservation of the morphology for the different organoids used. Their ultrastructural observation has allowed to deepen the knowledge of the architecture of organoids, particularly at the junctional level and in particular for cancer cells (D'Imprima et al. 2023).

Another interesting technique is volumetric electron microscopy (vEM), which is particularly interesting for studying 3D structures such as organoids. It is a technique that allows three‐dimensional structures to be visualized and studied at a very fine scale, often at the nanoscale. Using an electron beam that interacts with the sample to produce highly detailed images, volumetric electron microscopy creates a 3D reconstruction by combining several thin “slices” of a sample (Peddie et al. 2022). Prior to imaging, the sample is typically embedded in a solid resin and then sliced into ultra‐thin layers on the order of a few nanometers. These slices can be made using a microtome or other techniques such as focused ion beam (FIB). Each layer is then imaged with an electron microscope, and the images of the different layers are aligned and assembled by computer to produce a 3D visualization. This technique, to our knowledge, has rarely been used on the organoid model so far. However, D'Imprima et al. included it in their approach for multi‐scale imaging of 3D cell cultures from mice and humans, thus proposing a protocol applicable to any type of organoid (D'Imprima et al. 2023). However, although it represents a significant advance in the study of organoids due to its volumetric nature, electron microscopy, including volumetric imaging, has limitations that should be kept in mind when choosing an imaging technique, starting with the very complex preparation of the sample. Furthermore, this technique requires fixation of the sample, preventing any study on living cells, in addition to being destructive (since the organoid is sliced into sections).

1.3.3. Specific Microscopy Used in Mechanobiology Studies

1.3.3.1. Atomic Force Microscopy and Traction Force Microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) involves bringing a tip close to the surface of an object or tissue to obtain characteristics such as surface topography or elasticity. Although commonly used in biology, particularly in the study of DNA–protein interactions, this type of imaging is not intended to study events that occur over time but rather to characterize samples at a given moment. This technique is notably used to characterize the physical and mechanical properties of tissues, cells, ECM, but also organoids. For example, it has been used to determine the Young's modulus of brain organoids (Ryu et al. 2021), but also the mechanical characteristics of human hepatic organoids (Kobayashi et al. 2020) or to compare the elasticity of healthy human brain organoids with those from patients with schizophrenia (Dutta et al. 2022).

Traction force microscopy (TFM) is not directly an imaging technique, but rather an experimental method to determine the traction forces exerted by a tissue, cells, organoids, and so forth on their matrix environment. This method is particularly useful in mechanobiology, and is increasingly used on the organoid model (Broguiere et al. 2018). TFM allows in particular the observation and measurement of the forces involved in intestinal organoids during laser ablation of a cell but also during the re‐closure of the organoid following this loss (Donath et al. 2023). Using 3D TFM, the traction forces exerted by an intestinal organoid monolayer on supports according to their stiffness could be studied (Pérez‐González et al. 2021).

1.3.3.2. Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) is an imaging technique based on the properties of fluorescent probes because each one has its own lifetime. This lifetime corresponds to the time taken by the fluorophore to emit a photon after being excited. FLIM is generally associated with conventional photon microscopy, such as confocal or multiphoton. This technique is generally used to characterize the metabolic evolution of organoids (Browne et al. 2017; Dmitriev and Okkelman 2020). However, the development of specific probes in recent years has made it possible to use FLIM technology in mechanobiology studies. For example, FLIM has been used to study the viscosity of tumoroids and their evolution in real‐time (Shirmanova et al. 2017). The Flipper‐TR probe, developed in 2018, targets the plasma membrane of cells, including in organoids, and allows the visualization of changes in membrane tension; in fact, the lifetime of the fluorescence of the probe depends on the tension in the membrane in which it is inserted (Colom et al. 2018). Thanks to this probe, it was notably possible to show that the membrane tension of intestinal organoid monolayers depends on the curvature of the substrate on which it is cultured (Yavitt et al. 2023).

1.3.3.3. Brillouin Microscopy

Another specific method for studying mechanics in biology, including on organoids, is Brillouin microscopy. By definition, this is a non‐destructive imaging technique usable on living cells, characterized in particular by the absence of labeling and contact. From a technical point of view, when laser light comes into contact with a transparent or semi‐transparent medium, part of it is scattered inelastically by the acoustic waves of the material. This phenomenon causes a frequency shift of the scattered light, called Brillouin shift. This shift, linked to the speed of acoustic waves in the material, directly depends on its mechanical properties. By combining the measurement of the frequency shift with knowledge of the properties of the material, it is possible to deduce mechanical parameters. In particular, it makes it possible to obtain information on the viscoelastic properties of the biological samples studied, in 3D (Prevedel et al. 2019). Currently, Brillouin microscopy in biology can be described as an emerging technique. In this sense, there are only few studies using it on organoid models. However, we can report the use of this particular technique on mouse mammary gland organoids to validate its applicability (Yang et al. 2023). To cite another example, we can cite a study published in 2024, aimed at evaluating the impact of dolutegravir during pregnancy on the risk of neural tube defects. The combined use of cerebral organoids and Brillouin microscopy shows that cerebral organoids exposed to dolutegravir exhibit increased stiffness (Caiaffa et al. 2024).

1.3.3.4. Second/Third Harmonic Generation Microscopy

Second and Third harmonic microscopy (SHG and THG, respectively) are nonlinear microscopy techniques that allow the study of tissue structure and dynamics without the use of exogenous markers (Débarre et al. 2006). In mechanobiology, these techniques are particularly useful for analyzing the mechanical properties of extracellular matrices (ECM). SHG microscopy is sensitive to optically non‐centrosymmetric structures, such as collagen fibers, enabling their organization and orientation to be visualized, as well as the impact of mechanical forces on their arrangement to be studied. Similarly, THG microscopy allows the observation of cellular and tissue structures, including those involved in membrane tension and deformation. These techniques are therefore crucial for understanding the mechanical responses of cells and tissues to external stimuli, thus contributing to the study of pathophysiological processes such as cancer (Keikhosravi et al. 2014). Furthermore, these techniques are applicable to living cells, allowing to capture the dynamics of these processes. However, the components that can be visualized are limited, as they must naturally generate a second or third harmonic signal. To our knowledge, these techniques have never been applied directly to organoids, but interestingly, tubulin, which makes up the mitotic spindle during cell division and is a key player in cell mechanobiology, can be visualized using this method (Aghigh et al. 2023).

1.4. Analysis Techniques

As we have just seen, there are many imaging techniques that can be implemented in the case of mechanobiology studies on organoids. In addition, it is essential to perform imaging on living cells in order to fully capture the different cellular mechanics in real‐time. In order to fully analyze them, different techniques are possible. If a simple observation, for example, of a distribution of cell types, can be carried out without a particular analysis tool (Gjorevski et al. 2022), we will see here the more specific methods (Table 3) for studying mechanical interactions in vitro.

Table 3.

Comparison of mechanical interaction analysis techniques that can be used at least theoretically on organoid models.

| Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) | Digital Image Correlation 2D (DIC 2D) | Digital Image Correlation 3D (DIC 3D) | Digital Volume Correlation (DVC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Tracking the movement of particles in a flow using images captured at regular intervals | Tracking texture patterns on the surface of a material to analyze 2D displacements and deformations | Tracking of 3D texture patterns using images taken by several cameras to analyze 3D displacements and deformations | Volumetric analysis of 3D deformations, generally using several views or optical tomography |

| Application domains | Fluid mechanics, gaseous and liquid flows | Solid mechanics, analysis of plane deformations | Solid mechanics, analyzing deformations on complex surfaces | Analysis of internal deformations and displacements in three‐dimensional objects |

| Already used on organoids? | Yes, frequently | No | No | Only in one study |

| Dimension | 2D ou 3D (stéréo‐PIV) | 2D: deformation in plane | 3D: 2D surface with out‐of‐plane deformation | 3D: deformation in the volume |

| Imaging technique | Based on traced particles illuminated by a laser | 2D images, only one camera needed | At least two cameras needed to reconstruct the 3D surface | Volumic images (3D images) or assembly of 2D images to obtain a “z‐stack” |

| Spatial resolution | Depends on particle density. Variable resolution depending on the microscope used | Limited to the resolution of the cameras and the quality of the surface speckle pattern | Depends on the camera resolution and the density of speckle pattern in the volume | |

| Temporal resolution | Very high, limited by the sampling frequency of cameras and lasers | Varies according to image acquisition frequency. | Limited by the complexity of the volume and the image acquisition frequency | |

| Advantages | Enables fast, accurate measurements in complex flows, particularly in organ‐on‐a‐chip systems with organoids | A simple, accessible method for analysing 2D deformations | Enables more accurate and realistic analysis of deformations on surfaces | Enables the capture of internal volumetric information not accessible with 2D or 3D techniques |

| Limitations |

Requires tracer particles and sophisticated laser illumination. Points not very dense, difficult to obtain displacement fields |

Limited to flat surfaces and well‐defined textures. Need to create the speckle pattern if the surface is not naturally textured. |

More complex to implement, requiring precise camera calibration and a minimum of two cameras Need to create the speckle pattern if the surface is not naturally textured |

High complexity, longer processing time. Need to create the speckle pattern if the surface is not naturally textured. |

1.4.1. Construction of Numerical Models From Organoid Images

Mathematical models built from biological data from organoids can help to better analyze observed mechanical interactions, predict behaviors to anticipate reactions of biological models without the need to perform costly or lengthy experiments, or test different hypotheses in silico before testing them in vivo or in vitro, thus saving time and resources. As a result, more and more research teams are using numerical models to try to answer different biological questions, particularly on the mechanical interactions between an epithelium and its matrix environment. Numerical simulation makes it possible to quickly affirm or refute hypotheses that could hardly be tested on purely biological models. However, these models are also dependent on simplifying hypotheses and mathematical theories, and thus on the numerical errors generated, and are therefore often more qualitative than quantitative in cell biology. Here, we will show the numerical models based on image analysis used in conjunction with an organoid model in the study of intrinsic or extrinsic forces experienced by the epithelium. For example, a numerical mechanical model of intestinal epithelial organoids based on a finite element method (FEM) combined with a vertex model has also been recently developed from organoid images. The advantage of implementing an FEM method in a vertex model lies in the fact that it can consider the physical properties of the materials as well as the deformation stresses. The ability of this model to relate the behavior of individual cells to the overall deformation of tissues imposed could have future applications in diagnostic and screening approaches, making it possible to identify early alterations in a patient's organoids (Laussu et al. 2025).

To study the forces that enable organoids to form crypts, have cellular compartmentalization and collective movements, images of mouse intestinal organoids were used to implement a numerical model (Pérez‐González et al. 2021). The authors were able to observe a non‐monotonic distribution of constraints that defines mechanical and cellular compartments. The numerical model reveals that the shape of the crypt and the distribution of forces depend on the tensions on the surface of the cells as a function of actomyosin density. Still with the aim of studying the forces that allow organoids to form crypts, Liberali's team worked on a mouse organoid model to show that crypt formation coincides with a strong reduction in the volume of the intestinal lumen (Yang et al. 2021). In addition to this biological model, a 3D numerical model was developed to screen by computation different mechanical scenarios that could explain crypt morphogenesis, scenarios that were experimentally verified. Indeed, by applying different mechanical perturbations to the organoids such as blocking cell division or actomyosin contraction, one of the scenarios obtained by computation was validated. Thus, crypt morphogenesis is due to a simultaneous action of the reduction of the volume of the lumen and the apical contraction of the crypt cells.

So far, we have presented in particular numerical models to assess the impact of external mechanical constraints on epithelia. However, to fulfill their different functions, the mechanical properties of the epithelia themselves can prove to be crucial parameters. Thanks to a combination of biological and theoretical models, it is known that the Young's moduli of monolayers of epithelial cell lines are much higher than those of isolated cells (1 MPa vs. 1 kPa). This very important difference illustrates the importance of cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions in tissue stiffness (Li et al. 2023) which can also be altered in the event of pathology. Thus, this type of multidisciplinary study could provide mechanical information on changes in tissue stiffness involved in pathological development involving an alteration of matrix stiffness (fibrosis, cancer etc.).

1.4.2. Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV)

PIV is an imaging technique aimed at obtaining the velocity field within a flow (Abdulwahab et al. 2020). This optical method is used in flow visualization and in fluid dynamics studies. The principle of PIV is as follows: particles, naturally present or added to the system studied, are imaged using a camera at short intervals (Fischer 2014). By using the scale and knowing the time delay between the different acquisitions, the speed can be easily determined. In order to obtain the speed fields in a three‐dimensional system, two cameras positioned in a stereoscopic configuration will be necessary to measure all the components of the speed.

The applications of PIV in fields related to biology are numerous, such as the study of blood flow. Indeed, PIV can be used to study the dynamics of blood flow in vessels in order to understand the mechanisms underlying conditions such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, and other cardiovascular diseases (Franzetti et al. 2022). This technique can also be used in the field of mechanobiology, particularly in association with the organoid biological model. Indeed, part of the knowledge we currently have on the mechanical interactions between the epithelium and the ECM is due to PIV coupled with an organoid model, such as the mechanisms behind the movements of cells from the crypt to the villi. PIV revealed strong spatial fluctuations in cell speed, characterized by clusters of fast‐moving cells surrounded by almost immobile cells. Kymographic representation showed that the speed is low in the stem cell compartment, increases near the transit amplification zone, and reaches a maximum at the border with the villi domain (Pérez‐González et al. 2021). To illustrate its use with organoids from different tissues, PIV was applied to the matrix surrounding human mammary gland organoids to study how the development of epithelial branches deforms the matrix. By performing confocal imaging over time periods of up to several days, the authors observed that the development of each branch led to significant deformations of the matrix, of several millimeters (Buchmann et al. 2021). Open‐source PIV software could also be developed in response to a specific need, such as PIV‐MyoMonitor, designed to study the contractility of cardiac organoids (Lee et al. 2024).

In addition, PIV is commonly used in organ‐on‐a‐chip models to assess the flows circulating in them (Busek et al. 2023; Carvalho et al. 2024; Matsumoto et al. 2022), in some cases with organoids as a biological model. In particular, it has recently been used to characterize the flows in an organ‐on‐a‐chip system based on liver organoids and aimed at recirculating immune cells (Busek et al. 2023). In order to apply flow constraints on human intestinal organoids, a microfluidic device was developed to trap these organoids and force them to let a fluid pass (Matsumoto et al. 2022). In this study, the authors use PIV to characterize in particular the speed of the circulating fluid.

1.4.3. Digital Correlation

As we have just seen, PIV has a wide field of application in mechanobiology. However, the information it provides is generally limited to velocity fields. In PIV, the points used for tracking a sample are sparse: they are tracked individually, each point being identifiable and tracked independently of the others. Therefore, even if it is theoretically possible to use PIV to obtain displacement fields and deduce deformation fields, the sparse density of tracking points can lead to inaccuracy in the calculated stresses. For this, Digital Image Correlation (DIC), using a much higher point density, can be used. DIC is an experimental technique that relies on the exploitation of two images, the first in a reference state, the other in a deformed state of the same surface. Image correlation techniques can be classified into three main categories: two‐dimensional DIC (2D‐DIC), three‐dimensional DIC (3D‐DIC), and Digital Volume Correlation (DVC). The difference between 3D‐DIC and DVC lies in the geometric nature of the object studied. In the case of 3D‐DIC, it is a surface, which can be deformed in the three dimensions of space (like a metal plate that undergoes an impact, thus deforming it out of the plane) while in the case of DVC, the displacement fields measured are in the volume of the object which is itself in 3D. Given the three‐dimensional nature of organoids embedded in a 3D matrix, DVC appears to be the most appropriate technique in this context. The principle of DVC is to cut the reference volume image using a grid, and to individually search for each of the sub‐volumes thus obtained in the deformed image (Pan and Wang 2020). For this, it is essential that each sub‐volume is textured and different from those surrounding it, in order to be identifiable in the deformed state. The sample studied can be naturally textured or not; in the second case, it is necessary to create an artificially random texture, called speckle. Generally speaking, and regardless of the nature of the samples, the displacements observed in the images of the deformed state are quantified using algorithms specifically designed for these purposes, which can be either open‐source (such as YaDiCs, CORRELI Volumique or X‐DVCorrel), or integrated into commercial software (such as VicVolume, StrainMaster or VGSTUDIO MAX).

DIC, and even DVC, techniques are well‐developed in many areas of experimental mechanics, but studies on biological models present difficulties for their use, among which the possibility of obtaining a speckle of sufficient quality. Although DIC‐2 and DIC‐3D techniques have become widespread in the field of animal biology in the broad sense, DVC remains much less used today, although its first use dates back to 1999. The first use of DVC, a stress mapping in a knee bone, dates back to 1999 and was possible thanks to the spongy aspect which offered a natural texture similar to the speckles used in image correlation (Bay et al. 1999). Since this first application, constraints have been mapped in other types of musculoskeletal tissues (Dall'Ara and Tozzi 2022), including human shoulder blades, human femurs, or even the vertebral body (Boulanaache et al. 2020; Martelli et al. 2021; Palanca et al. 2021).

The use of DVC on soft tissues, such as organs and therefore organoids, is not yet widespread, but can be considered an emerging field, with few studies on the subject. An example is the work of Nahas et al. who used optical coherence tomography as an imaging technique, capable of imaging biological tissues in 3D with micrometric resolution, to which a DVC approach was coupled. Different biological tissues were used, such as pig cornea, human mammary tissue or rat heart, on which mechanical constraints were applied ex vivo (Nahas et al. 2013). This study, providing a proof of concept for the use of DVC on soft tissues, shows that it is possible to produce precise 3D displacement maps at the micrometric scale in biological tissues, from which it is possible to establish local 3D deformation maps. A study was conducted in 2018 on the ECM surrounding mouse tendons, showing that DVC allows to precisely detect deformations and to observe temporal changes in matrix mechanics (Fung et al. 2018). Still concerning the study of the ECM, DVC allowed to demonstrate the existence of localized changes in the orientation, curvature, and deformation of collagen fibers within intervertebral discs. These changes indicate differences in the transfer of stresses through the tissues, altering mechanical functions with a reduction in flexibility (Disney et al. 2022). Very recently, DVC was used for the first time to our knowledge on the human colonic epithelium organoid model. By adding fluorescent silica beads to the ECM (Matrigel) and using time‐lapse imaging with a spinning disc confocal microscope, this method demonstrated that the orientation of the mitotic spindle during cell division plays a role in the deformations undergone by this ECM in 3D. In particular, this study provides an interesting proof of concept for the use of image correlation methods on biological models, and organoids in particular (Magne et al. 2024).

2. Conclusion and Perspectives

For several years, mechanobiology has been at the heart of many studies. It is now essential to understand how mechanical forces, whether intrinsic or extrinsic, influence cells and the biological processes inherent in any tissue. To carry out this type of study, it is necessary not only to select a relevant biological model, but also to combine it with appropriate imaging and analysis techniques. In this sense, organoid culture ensures the adequacy of the biological model for this type of study on the basis of several major criteria: physiological relevance, self‐organization in 3D structure, rapid growth, the possibility of imposing certain constraints, the choice of the associated culture support (stiffness, topology), and finally the accessibility of the ECM. Currently, this type of real‐time study is limited by technical constraints, mainly 3D resolution imaging. In this review, we examined the different types of microscopes that can be used to visualize organoids, and the contributions of each in terms of tissue and/or cell mechanics. From the point of view of analysis and extraction of mechanical information, this review shows the variety of techniques that can be applied to organoids. It should be noted that the vast majority of the methods mentioned, and in particular image correlation and PIV, were initially used in other fields of research, such as mechanics of materials or fluidics studies. Based on this observation, we can envisage in the years to come the development of other techniques, from other disciplines, to deepen current knowledge in the field of mechanobiology, including on organoids. In fact, new approaches in mechanobiology of organoid have the potential to revolutionize the discipline by offering a better understanding of tissue dynamics and cellular behavior. Microfluidic technologies are now being integrated with organoids in organ‐on‐a‐chip systems, enabling real‐time monitoring of biomechanical signals and precise management of the microenvironment. These platforms enable the study of physiologically relevant conditions, such as shear stress or cyclic deformation (such as peristalsis), and how they affect organoid development and function. Furthermore, AI‐based image analysis techniques are revolutionizing organoid research by automating the measurement of complex aspects such as branching morphogenesis or 3D cellular configurations and revealing phenotypic alterations that might otherwise go unnoticed. Together, these advances have the potential to increase the predictability, scalability, and repeatability of organoid models, leading to potentially breakthrough discoveries.

To address the brad perspectives of the field, it would be interesting to explore several directions. First, combining some of the methods mentioned above, such as the integration of advanced imaging approaches with predictive computational models and artificial intelligence, could allow a more detailed understanding of the underlying mechanisms. This synergy would not only facilitate the real‐time visualization of biological processes, but also allow the modeling of complex interactions often inaccessible by traditional experimental methods. Additionally, it is crucial to focus on unsolved challenges, such as the standardization of culture, imaging, and analysis protocols to improve reproducibility, or the creation of biological models that more accurately reflect in vivo conditions. These models should encompass not only matrix characteristics (topology, stiffness, composition) but also cell populations (epithelial cells, fibroblasts, immune cells, etc.) while considering other aspects of the analyzed environment, such as the microbiota. By overcoming these obstacles, these emerging approaches could not only address current limitations but also foster new discoveries in this ever‐evolving field.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an ANR grant to the Molière project granted to FB (agreement grant number R21171BB), and two Cancer Plan funding: Mocassin—Biosystem 2017, granted to AF and Melchior—MIC 2020, granted to F.B. L.M. is supported by the INSERM and the Région Occitanie.

F. Bugarin and A. Ferrand contributed equally to this article.

Contributor Information

Florian Bugarin, Email: florian.bugarin@univ-tlse3.fr.

Audrey Ferrand, Email: audrey.ferrand@inserm.fr.

References

- Fluorescent probes—Latest research and news | Nature. (s. d.). Consulté 24 septembre 2024, à l'adresse. https://www.nature.com/subjects/fluorescent‐probes.

- Abdulwahab, M. R. , Ali Y. H., Habeeb F. J., Borhana A. A., Abdelrhman A. M., and Al‐Obaidi S. M. A.. 2020. “A Review in Particle Image Velocimetry Techniques (Developments and Applications).” Journal of Advanced Research in Fluid Mechanics and Thermal Sciences 65, no. 2: Article 2. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, T. , and Fujimori T.. 2013. “Reporter Mouse Lines for Fluorescence Imaging.” Development, Growth & Differentiation 55, no. 4: 390‑405. 10.1111/dgd.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghigh, A. , Bancelin S., Rivard M., Pinsard M., Ibrahim H., and Légaré F.. 2023. “Second Harmonic Generation Microscopy: A Powerful Tool for Bio‐Imaging.” Biophysical Reviews 15, no. 1: 43‑70. 10.1007/s12551-022-01041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay, B. K. , Smith T. S., Fyhrie D. P., and Saad M.. 1999. “Digital Volume Correlation: Three‐Dimensional Strain Mapping Using X‐Ray Tomography.” Experimental Mechanics 39, no. 3: 217‑226. 10.1007/BF02323555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanaache, Y. , Becce F., Farron A., Pioletti D. P., and Terrier A.. 2020. “Glenoid Bone Strain After Anatomical Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: In Vitro Measurements With Micro‐CT and Digital Volume Correlation.” Medical Engineering & Physics 85: 48‑54. 10.1016/j.medengphy.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broguiere, N. , Isenmann L., Hirt C., et al. 2018. “Growth of Epithelial Organoids in a Defined Hydrogel.” Advanced Materials 30, no. 43: 1801621. 10.1002/adma.201801621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne, A. W. , Arnesano C., Harutyunyan N., et al. 2017. “Structural and Functional Characterization of Human Stem‐Cell‐Derived Retinal Organoids by Live Imaging.” Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 58, no. 9: 3311‑3318. 10.1167/iovs.16-20796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann, B. , Engelbrecht L. K., Fernandez P., et al. 2021. “Mechanical Plasticity of Collagen Directs Branch Elongation in Human Mammary Gland Organoids.” Nature Communications 12, no. 1: 2759. 10.1038/s41467-021-22988-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busek, M. , Aizenshtadt A., Koch T., et al. 2023. “Pump‐Less, Recirculating Organ‐on‐a‐Chip (rOoC) Platform.” Lab on a Chip 23, no. 4: 591‑608. 10.1039/D2LC00919F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiaffa, C. D. , Tukeman G., Delgado C. Z., et al. 2024. “Dolutegravir Induces FOLR1 Expression During Brain Organoid Development.” Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 17: 1394058. 10.3389/fnmol.2024.1394058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, V. , Gonçalves I. M., Rodrigues N., et al. 2024. “Numerical Evaluation and Experimental Validation of Fluid Flow Behavior Within an Organ‐on‐a‐Chip Model.” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 243: 107883. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2023.107883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom, A. , Derivery E., Soleimanpour S., et al. 2018. “A Fluorescent Membrane Tension Probe.” Nature Chemistry 10, no. 11: 1118‑1125. 10.1038/s41557-018-0127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall'Ara, E. , and Tozzi G.. 2022. “Digital Volume Correlation for the Characterization of Musculoskeletal Tissues: Current Challenges and Future Developments.” Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 10: 1010056. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Débarre, D. , Pena A.‐M., Supatto W., et al. 2006. “[Second‐ and Third‐Harmonic Generation Microscopies for the Structural Imaging of Intact Tissues].” Medicine Sciences: M/S 22, no. 10: 845‑850. 10.1051/medsci/20062210845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers, J. F. , Alieva M., Wellens L. M., et al. 2019. “High‐Resolution 3D Imaging of Fixed and Cleared Organoids.” Nature Protocols 14, no. 6: 1756‑1771. 10.1038/s41596-019-0160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers, J. F. , van Vliet E. J., Sachs N., et al. 2021. “Long‐Term Culture, Genetic Manipulation and Xenotransplantation of Human Normal and Breast Cancer Organoids.” Nature Protocols 16, no. 4: 1936‑1965. 10.1038/s41596-020-00474-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medeiros, G. , Ortiz R., Strnad P., et al. 2022. “Multiscale Light‐Sheet Organoid Imaging Framework.” Nature Communications 13, no. 1: 4864. 10.1038/s41467-022-32465-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Imprima, E. , Garcia Montero M., Gawrzak S., et al. 2023. “Light and Electron Microscopy Continuum‐Resolution Imaging of 3D Cell Cultures.” Developmental Cell 58, no. 7: 616–632.e6. 10.1016/j.devcel.2023.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disney, C. M. , Mo J., Eckersley A., et al. 2022. “Regional Variations in Discrete Collagen Fibre Mechanics Within Intact Intervertebral Disc Resolved Using Synchrotron Computed Tomography and Digital Volume Correlation.” Acta Biomaterialia 138: 361‑374. 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev, R. , and Okkelman I.. 2020. “Multi‐Parameter Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) for Imaging Metabolism in the Intestinal Organoids Model.” Biophysical Journal 118, no. 3: 330a. 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.11.1846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donath, S. , Seidler A. E., Mundin K., et al. 2023. “Epithelial Restitution in 3D—Revealing Biomechanical and Physiochemical Dynamics in Intestinal Organoids via Fs Laser Nanosurgery.” iScience 26, no. 11. 10.1016/j.isci.2023.108139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, A. , Biber J., Bae Y., et al. 2022. “Model‐Based Investigation of Elasticity and Spectral Exponent From Atomic Force Microscopy and Electrophysiology in Normal Versus Schizophrenia Human Cerebral Organoids.” Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference, 2022 , 1585‑1589. 10.1109/EMBC48229.2022.9871376. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fang, G. , Lu H., Al‐Nakashli R., et al. 2021. “Enabling Peristalsis of Human Colon Tumor Organoids on Microfluidic Chips.” Biofabrication 14, no. 1: 015006. 10.1088/1758-5090/ac2ef9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei, K. , Zhang J., Yuan J., and Xiao P.. 2022. “Present Application and Perspectives of Organoid Imaging Technology.” Bioengineering 9, no. 3: 121. 10.3390/bioengineering9030121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J. 2014. “ Identification de Sources Aéroacoustiques au Voisinage De Corps Non Profilés par Formation De Voies Fréquentielle et Temporelle .” 10.13140/RG.2.1.1919.6966. [DOI]

- Franzetti, G. , Bonfanti M., Homer‐Vanniasinkam S., Diaz‐Zuccarini V., and Balabani S.. 2022. “Experimental Evaluation of the Patient‐Specific Haemodynamics of an Aortic Dissection Model Using Particle Image Velocimetry.” Journal of Biomechanics 134: 110963. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2022.110963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung, A. K. , Paredes J. J., and Andarawis‐Puri N.. 2018. “Novel Image Analysis Methods for Quantification of In Situ 3‐D Tendon Cell and Matrix Strain.” Journal of Biomechanics 67: 184‑189. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjorevski, N. , Nikolaev M., Brown T. E., et al. 2022. “Tissue Geometry Drives Deterministic Organoid Patterning.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 375, no. 6576: eaaw9021. 10.1126/science.aaw9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjorevski, N. , Sachs N., Manfrin A., et al. 2016. “Designer Matrices for Intestinal Stem Cell and Organoid Culture.” Nature 539, no. 7630: 560‑564. 10.1038/nature20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, S. , Lei P., Kang W., et al. 2023. “Stiffness Restricts the Stemness of the Intestinal Stem Cells and Skews Their Differentiation Toward Goblet Cells.” Gastroenterology 164, no. 7: 1137–1151.e15. 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalidasan, V. , Ng W. H., Ishola O. A., Ravichantar N., Tan J. J. , and Das K. T.. 2021. “A Guide in Lentiviral Vector Production for Hard‐to‐Transfect Cells, Using Cardiac‐Derived C‐Kit Expressing Cells as a Model System.” Scientific Reports 11, no. 1: 19265. 10.1038/s41598-021-98657-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keikhosravi, A. , Bredfeldt J. S., Sagar A. K., and Eliceiri K. W.. 2014. “Second‐Harmonic Generation Imaging of Cancer.” Methods in Cell Biology 123: 531‑546. 10.1016/B978-0-12-420138-5.00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, N. , Togo S., Matsuzaki T., et al. 2020. “Stiffness Distribution Analysis in Indentation Depth Direction Reveals Clear Mechanical Features of Cells and Organoids by Using AFM.” Applied Physics Express 13, no. 9: 097001. 10.35848/1882-0786/abaeb5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemant, L. , Lebreton C., and Garfa‐Traoré M.. 2020. “Comparison of Different Clearing and Acquisition Methods for 3D Imaging of Murine Intestinal Organoids.” Journal of Biological Methods 7, no. 4: e141. 10.14440/jbm.2020.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laussu, J. , Michel D., Magne L., et al. 2025. “Deciphering the Interplay Between Biology and Physics With a Finite Element Method‐Implemented Vertex Organoid Model: A Tool for the Mechanical Analysis of Cell Behavior on a Spherical Organoid Shell.” PLOS Computational Biology 21, no. 10: e1012681. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1012681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. , Kim B., Yun J., et al. 2024. “PIV‐MyoMonitor: An Accessible Particle Image Velocimetry‐Based Software Tool for Advanced Contractility Assessment of Cardiac Organoids.” Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 12. 10.3389/fbioe.2024.1367141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.‐Y. , Chen P.‐C., Lin S.‐Z., and Li B.. 2023. “Characterizing Mechanical Properties of Epithelial Monolayers Based on Indentation.” European Physical Journal Special Topics 232, no. 16: 2727‑2738. 10.1140/epjs/s11734-023-00931-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lian, J. , Meng X., Zhang X., and Hu H.. 2022. “Establishment and Genetic Manipulation of Murine Hepatocyte Organoids.” Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE 180. 10.3791/62438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.‐C. , Haga K., Zeng X.‐L., and Estes M. K.. 2022. “Generation of CRISPR–Cas9‐Mediated Genetic Knockout Human Intestinal Tissue–Derived Enteroid Lines by Lentivirus Transduction and Single‐Cell Cloning.” Nature Protocols 17, no. 4: 1004‑1027. 10.1038/s41596-021-00669-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo‐Martín, L. F. , Hübscher T., Bowler A. D., et al. 2024. “Spatiotemporally Resolved Colorectal Oncogenesis in Mini‐Colons Ex Vivo.” Nature 629, no. 8011: 450‑457. 10.1038/s41586-024-07330-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, M. , Xue S.‐L. , De Vos W. H. , et al. 2021. “Cell Monolayers Sense Curvature by Exploiting Active Mechanics and Nuclear Mechanoadaptation.” Nature Physics 17, no. 12: 1382‑1390. 10.1038/s41567-021-01374-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magne, L. , Pottier T., Michel D., et al. 2024. “Unveiling Mechanical Interactions Between Cell Division and Extracellular Matrix in human Colonic Epithelium Organoids: A 4D Study Using DVC.” bioRxiv p. 2024.10.07.617033. 10.1101/2024.10.07.617033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli, S. , Giorgi M., Dall″ Ara E., and Perilli E.. 2021. “Damage Tolerance and Toughness of Elderly human Femora.” Acta Biomaterialia 123: 167‑177. 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, M. , Morimoto Y., Sato T., and Takeuchi S.. 2022. “Microfluidic Device to Manipulate 3D Human Epithelial Cell‐Derived Intestinal Organoids.” Micromachines 13, no. 12: Article 12. 10.3390/mi13122082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F. , Shen C., Yang L., et al. 2022. “Mechanical Stretching Boosts Expansion and Regeneration of Intestinal Organoids Through Fueling Stem Cell Self‐Renewal.” Cell Regeneration 11: 39. 10.1186/s13619-022-00137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. E. , Hu P., and Barker T. H.. 2020. “Feeling Things out: Bidirectional Signaling of the Cell‐ECM Interface, Implications in the Mechanobiology of Cell Spreading, Migration, Proliferation, and Differentiation.” Advanced Healthcare Materials 9, no. 8: e1901445. 10.1002/adhm.201901445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrofanova, O. , Nikolaev M., Xu Q., et al. 2024. “Bioengineered Human Colon Organoids With In Vivo‐Like Cellular Complexity and Function.” Cell Stem Cell . 10.1016/j.stem.2024.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nahas, A. , Bauer M., Roux S., and Boccara A. C.. 2013. “3D Static Elastography at the Micrometer Scale Using Full Field OCT.” Biomedical Optics Express 4, no. 10: 2138‑2149. 10.1364/BOE.4.002138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]