ABSTRACT

Human monkeypox (Mpox) is a zoonotic disease caused by monkeypox virus (MPXV) present in western Africa and exported sporadically worldwide. MPXV causes illness in individuals and pregnant women which constitute a population at risk with obstetrical and fetal complications including miscarriage, stillbirth and premature delivery. There are accumulated data suggesting a vertical transmission of MPXV from mother to fetus. This review provides an overview of the literature on MPXV infection in pregnant women with a specific focus on vertical transmission.

Keywords: fetus, Monkeypox, placenta, pregnancy, vertical transmission

1. Introduction

Human monkeypox (Mpox) is a zoonotic disease caused by monkeypox virus (MPXV), a large double‐stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, family Poxviridae [1]. In 1958, skin lesions characteristics of smallpox disease and presence of OPXV‐specific antibodies in serum samples were observed in cynomolgus monkeys in a Danish laboratory. The use of electron microscopy enabled the detection of brick‐shaped particles between 100 and 150 nm, different in appearance from other known members of the genus OPXV [2]. This first observation led to propose the term « monkeypox virus ».

In 1970, a boy (9‐month‐old) was the first recognized case of human mpox infection. He was the only member of his family without a smallpox vaccination [3]. MPXV is present in western Africa and spreads sporadically worldwide [4, 5]. Sporadic cases of the disease were reported in the center of the African Republic, in Congo (Kinshasa), Cameroon, Liberia, Sudan and Nigeria [1, 5, 6]. This family of viruses includes DNA viruses such as cowpox, vaccinia and smallpox, which was eradicated in 1980 [7]. According to further research, MPXV has a wide variety of hosts, such as monkeys, squirrels, prairie dogs, gambian mice and humans [8]. This virus is transmitted through bites or scratches from infected animals or following contact with fluid from lesions of in sexual intercourse among men who have sex with men [9, 10]. MPXV presents a broad tissue tropism. Two variants of MPXV have been reported: West Africa and Central Africa. The variant from Central Africa is the most virulent with 10% mortality (vs. 1% for the West African variant) and seems to be responsible for the current 2022‐2024 global mpox outbreak [11, 12].

In 2022, the WHO declared the current MPXV epidemic a public health emergency and assigned the term “Mpox“ [13, 14]. Over 80 000 cases have been reported and recorded in more than 100 countries, which most of them were not previously endemic [15, 16]. The smallpox virus has been eradicated by the introduction of vaccination. This virus has genetic and antigenic characteristics common to orthopoxviruses. Thus, infection with an orthopoxvirus could lead to the production of antibodies that can resist other types of orthopoxviruses [17, 18]. However, since smallpox vaccination has been progressively discontinued in various countries, population resistance to various orthopoxviruses has gradually declined [19, 20]. The frequency and geographic distribution of human cases of monkeypox has increased significantly in recent years, which is a major public health threat [21, 22, 23].

Most people infected with MPXV exhibit mild disease. However, MPXV can cause serious illness in certain population groups such as children, immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women. Pregnant women present an at‐risk population with the outcome of obstetrical and fetal complications including miscarriage, stillbirth and premature delivery [24]. Accumulated data suggest a vertical transmission. This review provides an overview of the literature on MPXV infection in pregnant women by pointing at evidence of vertical transmission from mother to fetus.

2. MPXV

2.1. Monkeypox Virus

MPXV is a brick‐shaped enveloped double‐stranded DNA zoonotic virus with morphological characteristics of members of the orthopoxvirus family [25, 26]. MPXV is a zoonotic virus of the Orthopoxvirus genus in the Poxviridae family, which includes smallpox (variola), cowpox, and vaccinia viruses [27].

The size of MPXV particles is between 200 and 450 nm long, approximately 160–260 nm wide. They have a large genome of around 197 Kilobase pairs encoding 190 proteins [16, 28]. Viruses consist of a linear double strand. The genome consists of dsDNA, a nucleoprotein core containing transcription factors (TFs), surface tubules and two lateral bodies [29].

The genomes of MPXV comprise a conserved core region and inverted terminal repeats with tandem repeats [30]. 96.3% of its central genomic region is similar to the variola with 99.2% homologous of the amino acid sequences of this region [31]. The host‐virus interaction genes are relatively unconcerned and are in the terminal region. There are two types of MPXV: the mature intracellular virus and the extracellular envelope virus [25, 26, 32].

2.2. Discovery

In 1958, the first active infection of Mpox was identified in Singapore‐based Cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) monkeys held in captivity in Copenhagen (Denmark) [2]. Nevertheless, several evidence suggest that MPXV may have been in circulation many years before its first identification. The examination of historical (120 year old) skin samples African rope squirrels (Funisciurus sp.) from Central Africa (DRC) and the Central African Republic (CAR), shows the presence of MPXV as early as 1899 [33]. Interestingly, it is suggested that MPXV may have been separated from the Old World PCOV about 3,00 years ago [34]. For the West African subtype, it was estimated to have occurred between 600 years and 1200 years [34, 35].

2.3. MPXV Clades

As smallpox, two viral clades of MPXV clinically relevant were reported: MPXV clade I and clade II corresponding to the “Congo basin” clade and the “West African” clade, respectively.

Both clades have pronounced genetic differences [36] but they are phylogenetically distinct [36]. Their associated genomes date from the 1960s and 1970s suggesting that these two clades evolved separately from a recent common ancestor. Indeed, neither IIa nor IIb are descendants of the other [37]. Focusing on the genome, a difference of 0.55% and 0.56% nucleotides was observed between clades I and IIa respectively. This difference is found notably in virulence genes and clinical severity [38, 39, 40]. With 99.5% similarity at the protein level and 170 orthologs, both clades contain 173 and 171 functional single genes, for clade I and Clade IIa, respectively [38].

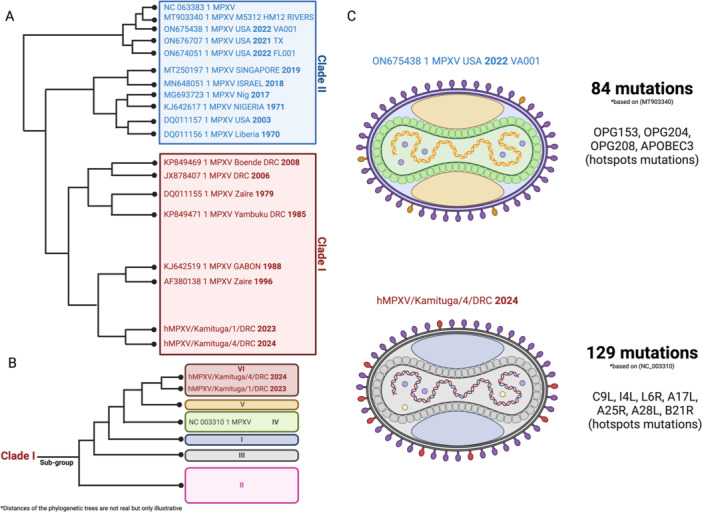

These two distinct clades of smallpox exhibited different mortality rates from 30% to 50% to < 2% [31]. The clade II is divided into two sub‐groups: clade IIa and IIb. Clade IIb is reported to be responsible for the 2022 pandemic and is more attenuated than clade IIa [41]. Compared to clade IIb, clade I causes severe illness with a threefold mortality rate [42, 43]. In April 2024, 27 countries have still reported new cases to the World Health Organization (WHO), including the rising Clade IIb epidemic in South Africa, mainly affecting men who have sex with men (MSM). At the same time, clade I MPXV epidemics are increasingly common in endemic regions, particularly in the DRC (Figure 1). Complete sequencing of the virus genome, sampled from 6 patients in the Kamituga region, shows a very high number of mutations compared with the clade I base sequence (NC_003310), with specific hotspots mutations [44].

Figure 1.

Phylogeny and evolution of MPXV over time. (A) Illustrative representation of the phylogeny of the various MPXV clades with a set of variants identified during the various epidemics. (B) Highlighting of the various MPXV clade I subgroups, with the last two variants responsible for the last two epidemics. (C) Structures and mutations of the last two variants responsible for the latest epidemics.

2.4. Transmission

Animal‐human transmission is assumed, especially during the manipulation of animals infected with MPXV, but route of transmission remains unknown [45]. The host of the MPXV reservoir remains unknown so far. Nevertheless, it has been reported that tree squirrels, Gambian pocket rats, rope squirrels, dormice and monkey species in Africa are infected and their rodents are involved in transmission [46]. Thus, people living near the habitats of these animals are directly exposed to these infected animals [47]. In 2003, the outbreak of MPXV infecting 70 people started with infection in a prairie dog farm in the United States due to the presence of a Gambian rat native to Africa [48, 49].

The virus spread between individuals through close contact with respiratory secretions or sexual intercourse, as well as through lesions on the skin of an infected person or recently contaminated objects [50].

2.5. Mechanism of Infection

MPXV binds to host cells by its glycosaminoglycans which are involved in endocytosis and viral entry [51]. Heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate have been proposed to be cell surface receptors involved in the binding of MPXV [52]. After attachment of the viral proteins to the cell membrane, MPXV is endocytosed by fusion with the cell membrane and the viral core is released within the cytoplasm. Viral genes are transcribed by a viral RNA polymerase 30 min after infection. Forty‐4 h after infection, late genes are expressed followed by the production of viral structural proteins [53]. These steps will eventually lead to the creation of the viral particle via assembly of the mpox offspring within the cytoplasm and the formation of an immature sphere that will mature in single membrane virion (SMI) [51, 52] The SMI moves towards the golgi body to acquire a double membrane conferring an antigenically distinct tri‐layer membrane. This enveloped external virion will be released from the host cell following its lysis.

2.6. Pathophysiology

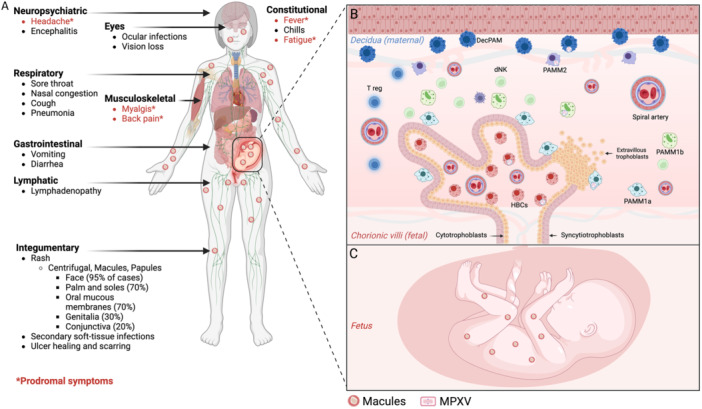

MPXV and smallpox present similar clinical features (Figure 2). MPXV infection presents a 5–12 days incubation period. The main feature of MPXV infection is the appearance of vesicles. The eruption phase begins with macules, then transforms into papules, vesicles and pustules before a scab appears after 7–14 days [54]. These can be macules, papules, vesicles or pustules, which can also appear all over the body and eyelids. The epithelial cell layers of the skin are disrupted by the appearance of lesions with bumps and/or pustules [1, 55, 56, 57]. The number of lesions is assessed during clinical examination because it evolves during the disease and especially correlated with the severity of the disease. Like smallpox disease, mpox has an incubation period of 7–14 days and begins with a presymptomatic stage of 1–4 days of fever, headache and myalgia with or without swelling in the lymph nodes. Exhaustion, chills, back pain, sore throat and malaise can be associated with lymphadenopathy [1, 55, 57]. The epithelial cells and surrounding tissues fall off with the scab, which heals 2–4 weeks later and renews itself. From then on, the subject is no longer considered infectious [1, 55, 56, 57].

Figure 2.

Clinicals outcome of MPXV infection in a vertebrate with different entry route. (A) Highlighting of all the clinical symptoms of MPXV infection, depending on the route of entry of the virus, with prodromal symptoms (highlighted in red). (B) Immunopathogenesis of MPXV in the placenta, with infection of different types of trophoblasts in the placental villi, but also of different types of placental macrophages. (C) Vertical transmission of MPXV infection to the fetus, with various fetal injuries and complications.

In 2022, a large‐scale outbreak was reported [58, 59, 60]. The epidemic in 2022 differed from previous epidemics. Firstly, infected individuals were predominantly in their thirties, but also mainly male. Risk factors and transmission routes were also different, notably sexual transmission was the most reported, with predominantly male‐male relations. In addition, the clinical presentation was atypical, characterized by anogenital lesions and rashes that relatively spared the face and extremities. The most common symptom reported was fever (54% of cases), followed by inguinal adenopathy (45%) and exanthema (40%). Asthenia, fatigue and headache were described in 22% and 25% of subjects respectively. Myalgia was present in 17% of cases. Genital and anal lesions, ulcers and vesicles were reported in 31% of cases. Finally, cervical lymphadenopathy was described in 11% of cases, while the least frequently reported symptoms were diarrhea and axillary lymphadenopathy [58, 59, 60].

The pathophysiology is dependent on the two clades. Experimentally, in infected nonhuman primates clade I has a higher pathogenicity than clade IIa [38, 61]. These differences are also observed in humans. In terms of mortality, clade I has a much higher rate (10%–15%) than clade IIa (1%–6%). This is associated with a difference in human‐to‐human transmission. Clade IIa is associated with lower transmissibility than clade I [42, 51, 62]. These differences are due to the ortholog of specific genes such as BR‐209 (interleukin (IL)‐1β binding protein), BR‐203 (virulence protein), COP‐C3L (complement enzyme inhibitor) [37, 38, 51] or D14R (complement‐binding protein inhibitor) [38, 63, 64]. To date, the functionality of these orthologs has yet to be determined.

2.7. Immune Response

To date, the immunity to MPXV infection remains not extensively characterized.

Regarding the innate immune response, monocytes appear to be the target cells of poxviruses. MPXV infection of cynomolgus macaques reveals viral pneumonia with an expansion of CD14+ monocytes and their active recruitment to the site of infection [65]. In parallel, a decrease in circulating neutrophils was associated with moribundity in MPXV‐infected animal models [66]. At the frontier between innate and adaptive immunity, natural killers (NKs) play a key role in the host immune response during MPXV infection. The NK population varies in MPXV‐infected rhesus macaques [67]. Initially, this population is altered by the infection with a direct impact on their recruitment to the site of infection. Then NK number expand in blood and lymph nodes. In the same model, a decrease in the expression of chemokine receptors (CXCR3, CCR5, CCR6, CCR7) and a loss of their ability to degranulate and secrete IFNγ and TNF had been reported [67]. The use of CAST/EiJ mice showed a correlation between viral clearance and number of NKs [68] and treatment of these mice with IL‐15 provided protection from lethal infection suggesting that NKs cell expansion has a protective effect against MPXV infection [69].

As demonstrating for variola virus infection, a “cytokine storm” was observed in MPXV‐infected cynomolgus macaques with high levels of IL‐1RA, IL‐2, IL‐6, IL‐8, IFNγ, CCL2, CCL5, G‐ CSF, GM‐CSF, CD40L soluble [65]. In human high levels of IL‐1β, IL‐1RA, IL‐2R, IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐13, IL‐15, IL‐17, CCL2, CCL5 was reported following MPXV infection regardless the disease severity [70]. Interestingly, patients with severe disease regarding their high number of lesions ( > 250), presented a significant higher concentration of IL‐2R, IL‐10, GM‐CSF, CCL5 compared to less severe disease patients, whereas IL‐6 level was lower [67]. Overall, these data suggest a dominant Th2 response complemented by an anti‐inflammatory environment associated with a regulatory T cell response.

Altogether, immune response during MPXV infection remains limited and will be required they are limited but necessary to understand the mechanisms of pathogenesis and immune defense.

3. MPXV and Pregnancy

3.1. Clinical Disease and Epidemiology

The first observation was made in 1980 in DR Congo in which a pregnant women was infected by MPXV [71]. After delivery, the liveborn presented skin rash suggesting a vertical transmission of the mpox disease. Six weeks later the newborn died of malnutrition.

To understand the natural history of mpox, a large study emerged in an endemic region in the Sankuru Province of DR Congo from March 2007 to July 2011: the Kole Human Monkeypox infection study [72, 73]. Among 222 patients, 36% were female which 4 were pregnant. This study reported that 75% of pregnant women (3/4) with PCR‐confirmed clade I mpox infection experienced a fetal demise (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported cases of MPXV infection in pregnant women population worldwide.

| Date (cases) | Countries | MPXV clade | Age (years) | Infection (weeks of gestation) | Symptoms | Obstetric complication | Fetal complication | Fetal Attachments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 (1 case) | RD Congo | Clade I | Not reported | Not reported |

|

Not reported |

|

Not reported | [71, 91] |

| 2007–2011 (4 cases) | Sankuru province in DR Congo | Clade I | 20 | 6 |

|

Not reported |

|

Not reported | [72] |

| 25 | 6–7 |

|

Not reported |

|

Not reported | ||||

| 22 | 18 |

|

Not reported |

|

|

||||

| 29 | 14 |

|

Not reported |

|

Not applicable | ||||

| 2017–2018 (1 case) | Nigeria | Clade IIa | Not reported | 26 |

|

Not reported |

|

Not reported | [39] |

| 2019 (1 case) | Nigeria | Clade IIa | Not reported | 16 |

|

Not reported |

|

Not reported | [39] |

| 2022 (24 cases) | United States | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

|

Not reported |

|

Not reported | [92] |

| Not reported | Not reported |

|

|

|

|

Not reported | [80] | ||

| 2023 (60 cases) | Global situation outside Africa and clade Ib | No clade Ib | Median age was 27.5 years (IQR: 22.75–31) |

|

Not reported | 15 cases hospitalized | Not reported | Not reported | [93] |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Regarding clade IIa MPXV infection and pregnancy, little data are available particularly from the endemic West African countries. Only two cases were reported in Nigeria [39, 74]. During 2017–2018, spontaneous abortion was reported for two pregnant women at 26 and 16 weeks of gestation. Pregnant women were both infected by the MPXV. No MPXV infection was reported at the fetal level and no fetal attachments were investigated.

During the 2022–2023 the virus spread outside endemic countries inducing global Mpox outbreak in which some cases of infected pregnant women by MPXV were reported but without maternal deaths (Table 1). In this period, more than 112 countries reported MPXV infection including 87,970 confirmed cases and 140 deaths between May 2022 and June 2023 [75]. Phylogenetic analyses showed that this outbreak was caused by a branch of the Clade II virus (West Africa). With a limited number of new mutations this clade could not be classified as a new clade, so it was called clade IIb [16, 76]. Compared to infected patients from West and Central Africa, during this Mpox outbreak people infected were bisexual men and gay men (MSM). The study of this small population of infected people showed that the transmission of the virus occurred during sexual activity with close contact with mpox lesions on the skin [59, 77, 78]. Nonpregnant and pregnant women as well as newborns were also infected during this global epidemic, whose overall mortality rate was less than 0.1% [10, 59, 79]. Fifty‐eight pregnant women with mpox infection were reported [75]. Among them 56 women were infected by MPXV during the 1st (4 cases), 2nd (12 cases) and 3rd (10 cases) trimester and 30 cases without available data. No maternal deaths and no information about fetal complications were reported.

The United States have also been affected by the spread of clade IIb MPXV. The first case of infection in a pregnant woman was reported in July 2022 without obstetric complications and a healthy newborn. Twenty‐three cases of MPXV infection of pregnant women were reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [80]. Infection was occurring during the 1st trimester for 3 cases, the 2nd trimester for 4 cases and the 3rd trimester for 3 cases; data were not available for the other cases. Data regarding delivery and fetal complications were poor reported. Two uncomplicated term abortions, one spontaneous abortion (11 weeks' gestation) were reported. Regarding newborn, two developed lesions of mpox after delivery suggesting a postpartum transmission.

Clade IIb infection was also reported in Brazil. In 2022, nine cases of mpox among pregnant women were reported by health authorities [81]. Eight were PCR positive for MPXV. Transmission phase with mother and baby were reported but no potential vertical transmission [81]. One year later, 22 pregnant women were infected by MPXV either in the 1st (2 cases), the 2nd (11 cases) or the 3rd (8 cases) trimester [82].

The major data reporting cases of vertical transmission come from retrospective cohorts from endemic regions associated with many biases. The first reason is the context of the investigation of these cohorts in resource‐limited countries, which will tend to focus on severe or fatal cases and whose asymptomatic infections will not be investigated by a lack of access to care. Regarding cohorts related to global epidemics, analyses associated with the obstetric field have not been studied because of a focus on infected men. These data highlight the need to standardize screen pregnant women and to set up prospective clinical studies framed by guidelines, standardized protocols and placenta/amniotic fluid exploration for MPXV‐positive pregnancies (PCR testing, histological and viral load) [83].

3.2. Risk of In Utero Transmission

The risk of transmission in utero was established following experiments carried out in rhesus macaques. Infection of pregnant rhesus macaques with MPXV clade IIb is associated with vertical transmission from the mother to the fetus and the occurrence of obstetric complications [84]. Other studies suggest different routes of infection hematogenous, genital ascending or lymphohematogenous [1]. MPXV was found to replicate in lymphoid tissues, after macaques' infection, and subsequently disseminated to others organ via the lymphohematogenous route [85, 86].

Accumulating evidence suggest a vertical transmission in humans (Table 1). In the Kole Human Monkeypox Infection Study, fetal attachments were analyzed [72, 73]. Among infected pregnant women, one case presented a mpox viremia with cessation of fetal movement and the delivery of a stillborn fetus. At delivery, stillborn fetus presented cutaneous maculopapular lesions (chest, head, abdomen, back, shoulders) including in the extremities (hands and feet). There was the presence of hydrops fetalis and hepatomegaly and peritoneal effusions characterizing the Congenital Mpox Syndrome [87]. During the membrane rupture, a transcutaneous amniocentesis revealed a positive PCR for mpox virus (2.6 × 107 genome copies/mL). After delivery, fetal blood from the umbilical vein (2.5 × 107 genome copies/mL), fetal tissue (1.7 × 107 genome copies/mL), peritoneal fluid (1.6 × 103 genome copies/mL), and placental tissue (2.4 × 107 copies/mL) were positive for MPXV. This first study highlighted the risk of MPXV infection for pregnant women and raises the question of the vertical transmission of the MPXV. In contrast, during the 2022–2023 mpox outbreak only one postpartum transmission was reported with nonintrauterine or placental infection [88, 89, 90, 91] questioning the vertical transmission of MPXV during pregnancy. These data come from infection with clade IIb whose overall lethality rate in pregnant women is relatively low ( < 0.1%). This may explain the absence of obstetric and fetal complications, especially since this clade is associated with a more attenuated form of the disease than the other clades. Recently, studies reported vertical transmission and fetal demise in a rhesus macaque model after intradermal clade IIb MPXV injection [84, 92]. Among 3 fetuses, two were dead in utero and the last one was associated to vaginal bleeding. Placental villi and fetal tissue were found positive for MPXV highlighting a vertical transmission to the fetus and adverse pregnancy outcomes. This finding raises regarding the absence of placental infection with clade IIb in human including low viral load, different viral replication kinetics [41], absence of vertical transmission or placental tropism. These hypotheses remain to be investigated in adapted experimental models.

Compared to clade I, clade IIb (2022–2023 outbreak) was associated to fewer fetal complications. Several hypotheses have been suggested. (1) No cases of perinatal complications have been reported in pregnant women infected with clade IIb and in contradiction to the observations communicated for the clade I and IIa [93]. (2) Clade IIb is associated with lower virulence than clade I (nonimmunocompromised individuals). The case fatality rate is less than 0.1% while clade I is associated with a higher rate (10%) and more severe clinical phases of the disease (congenital monkeypox syndrome and stillbirths) [41, 93]. (3) Clade‐specific mutations in entry proteins were reported. Recently, B22R was highlighted for genes deletion and single nucleotide polymorphisms [94]. B22R is a crucial protein involved in the host receptor binding and viral entry and immune evasion [94]. The authors reported correlation between B22R mutations and altered virulence, transmission and immune response. Also, the complement control protein, involved in the modulation of the host complement system, was found mutated (1141 bp deletion) in sequences of clade IIb [94]. (4) In vitro experiments revealed a less release of clade IIb compared to clade IIa from infected cells suggesting a reduced capacity of dissemination [41].

Although MPXV was found in the placenta so at the fetal‐maternal interface, no studies have identified the mechanisms involved in infection of fetal tissues after the virus has crossed the fetal‐placental barrier. Two options were proposed: (1) infection of the fetal‐maternal interface could be via the bloodstream. After viremia of the infected pregnant woman, MPXV may be found in the placenta via the arteries in the intervillous space. (2) MPXV found within the genital lesions could colonize the uterine cervical tissue as well as the decidua and chorionic membranes. The vaccina virus infection of pregnant mice revealed a long time required for contiguous virus spread from the mice blood to the fetus in utero. In this model, the authors reported the presence of the virus at the feto‐maternal interface with cytopathic syncytiotrophoblasts.

3.3. Response to Placental Infection

Finally, the presence of MPXV in placental tissue suggests a capacity of the virus to infect placental cells and/or immune cells (Figure 2), but no specific receptor for a cell tropism has been identified [95, 96]. As malaria [97], it was suggested that MPXV could exploit the chondroitin sulfate or the heparan sulfate as tissue receptors including placenta [98, 99, 100]. Research is expected to clarify placental tropism of MPXV.

We recently investigate the placental cell response against MPXV infection. Using full‐term placental explant from healthy donors infected in vitro by MPXV, we reported the presence of the virus in extra‐villous trophoblasts [26]. The long‐term MPXV infection induced loss of the tissue homogeneity and virus replication. We decipher the virus replication and highlight a specific release of MPXV particles through long filopodia where particles were project far away from the cell's soma. This study suggests that trophoblasts cells could be a target cell for MPXV.

Regarding innate immune response, we investigated macrophages from placenta response against MPXV infection (unpublished data). Using full‐term placental explant model, macrophages were recruited at site of infection. Isolated naïve macrophages are permissive to MPXV infection and express antiviral genes that do not suppress the virus. Interestingly, MPXV‐infected macrophages polarize into pro‐inflammatory secreting cells and secrete high levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines.

Studies of patients naturally infected with MPXV during pregnancy may better document the central role of the placenta and its immune cells.

3.4. Therapeutic Option

The tecovirimat and vaccinia immune globulin represent the only treatment options for pregnant women infected with MPXV although their use is limited. Tecovirimat is an antiviral drug initially developed against variola virus to treat smallpox, monkeypox and cowpox. Tecovirimat targets and inhibits the orthopoxvirus VP37 envelope wrapping protein to blocks the virus maturation and release from infected cell [101]. Focusing on obstetrical context, experiments with animal models reported no embryonic or fetal toxicity in mice and rabbits treated with doses up to 23 times higher than those used in humans. In treated mice, no prenatal and postnatal adverse effects were reported. Altogether suggesting a safety profile regarding pregnancy. Actually, tecovirimat is recommended a first‐line treatment option for pregnant women infected with MPXV if the benefits for the mother outweigh the potential risks for the fetus. It is recommended during breast‐feeding as the drug is excreted in breast milk in animals. Clinical studies in human report no significant adverse effects from 14 pregnant women treated with the drug [102]. Regarding severe orthopoxvirus infections, IGV is recommended for pregnant women despite few specific data on its efficacy or safety during pregnancy. To date, no specific data on the efficacy of tecovirimat or IGV were reported in the prevention of vertical transmission and fetal complications. A significant option is the possible cross‐reaction of smallpox vaccination with orthopoxviruses. Although suggested, this hypothesis should be explored taking into account the difficulties of interpretation with regard to the different clades.

4. Conclusion

Although little data is available, there is ample evidence to suggest that MPXV infection in pregnant women leads to obstetric and fetal complications. Nevertheless, the literature includes sporadic reports with a small number of cases, mostly in resource‐poor countries. Although cases of in utero infection have been reported, vertical transmission remains a source of controversy. However, the presence of the virus has been reported in fetal attachments including the placenta. Studies involving larger cohorts with investigation of the newborn and fetal attachments would allow a better understanding of the physiopathology of MPXV infection in pregnant women.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Jean‐louis Mège and Soraya Mezouar contributed equally.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text.

References

- 1. Lum F. M., Torres‐Ruesta A., Tay M. Z., et al., “Monkeypox: Disease Epidemiology, Host Immunity and Clinical Interventions,” Nature Reviews Immunology 22, no. 10 (2022): 597–613, 10.1038/s41577-022-00775-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magnus P., Andersen E. K., Petersen K. B., and Birch‐Andersen A., “A Pox‐Like Disease in Cynomolgus Monkeys,” Acta Pathologica Microbiologica Scandinavica 46, no. 2 (1959): 156–176, 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1959.tb00328.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sklenovská N. and Van Ranst M., “Emergence of Monkeypox as the Most Important Orthopoxvirus Infection in Humans,” Frontiers in Public Health 6 (2018): 241, 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rajsri K. S. and Rao M., “A Review of Monkeypox: The New Global Health Emergency,” Venereology 1, no. 2 (2022): 199–211, 10.3390/venereology1020014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pal M., Rebuma T., Berhanu W., Endale B., and Zende R., “Monkeypox: A New Challenge in Global Health Security,” Am J Epidemiol Infect Dis 12, no. 3 (2024): 37–43, 10.12691/ajeid-12-3-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alakunle E., Moens U., Nchinda G., and Okeke M. I., “Monkeypox Virus in Nigeria: Infection Biology, Epidemiology, and Evolution,” Viruses 12, no. 11 (2020): 1257, 10.3390/v12111257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brennan G., Stoian A. M. M., Yu H., et al., “Molecular Mechanisms of Poxvirus Evolution,” mBio 14 1 (2023): e01526‐22, 10.1128/mbio.01526-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jezek Z., Szczeniowski M., Paluku K. M., and Mutombo M., “Human Monkeypox: Clinical Features of 282 Patients,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 156, no. 2 (1987): 293–298, 10.1093/infdis/156.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hantz S., Mafi S., Pinet P., and Deback C., “Monkeypox to Mpox or the Re‐Emergence of an Old Zoonosis,” Revue francophone des laboratoires: RFL 2023, no. 553 (2023): 25–37, 10.1016/S1773-035X(23)00132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitjà O., Ogoina D., Titanji B. K., et al., “Monkeypox,” Lancet 401, no. 10370 (2023): 60–74, 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02075-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Titanji B. K., Tegomoh B., Nematollahi S., Konomos M., and Kulkarni P. A., “Monkeypox: A Contemporary Review for Healthcare Professionals,” Open Forum Infectious Diseases 9, no. 7 (2022): ofac310, 10.1093/ofid/ofac310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harapan H., Ophinni Y., Megawati D., et al., “Monkeypox: A Comprehensive Review,” Viruses 14, no. 10 (2022): 2155, 10.3390/v14102155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graham F., “Daily Briefing: Mpox — A New Name for Monkeypox,” Nature, ahead of print, November 29, 2022, 10.1038/d41586-022-04233-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. WHO Recommends New Name for Monkeypox Disease . WHO; Geneva, Switzerland. Published online November 28, 2022.

- 15. Hraib M., Jouni S., Albitar M. M., Alaidi S., and Alshehabi Z., “The Outbreak of Monkeypox 2022: An Overview,” Annals of Medicine & Surgery 79 (2022): 104069, 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Isidro J., Borges V., Pinto M., et al., “Phylogenomic Characterization and Signs of Microevolution in the 2022 Multi‐Country Outbreak of Monkeypox Virus,” Nature Medicine 28, no. 8 (2022): 1569–1572, 10.1038/s41591-022-01907-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zaeck L. M., Lamers M. M., Verstrepen B. E., et al., “Low Levels of Monkeypox Virus‐Neutralizing Antibodies After MVA‐BN Vaccination in Healthy Individuals,” Nature Medicine 29, no. 1 (2023): 270–278, 10.1038/s41591-022-02090-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yuan P., Tan Y., Yang L., et al., “Modeling Vaccination and Control Strategies for Outbreaks of Monkeypox at Gatherings,” Frontiers in Public Health 10 (2022): 1026489, 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1026489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Poland G. A., Kennedy R. B., and Tosh P. K., “Prevention of Monkeypox With Vaccines: A Rapid Review,” Lancet Infectious Diseases 22, no. 12 (2022): e349–e358, 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gruber M. F., “Current Status of Monkeypox Vaccines,” NPJ Vaccines 7, no. 1 (2022): 94, 10.1038/s41541-022-00527-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shaheen N., Diab R. A., Meshref M., Shaheen A., Ramadan A., and Shoib S., “Is There a Need to be Worried About the New Monkeypox Virus Outbreak? A Brief Review on the Monkeypox Outbreak,” Annals of Medicine & Surgery 81 (2022): 104396, 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ranganath N., Tosh P. K., O'Horo J., Sampathkumar P., Binnicker M. J., and Shah A. S., “Monkeypox 2022: Gearing Up for Another Potential Public Health Crisis,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 97, no. 9 (2022): 1694–1699, 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luo Q. and Han J., “Preparedness for a Monkeypox Outbreak,” Infectious Medicine 1, no. 2 (2022): 124–134, 10.1016/j.imj.2022.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nishiura H., “Smallpox during Pregnancy and Maternal Outcomes,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12, no. 7 (2007): 1119–1121, 10.3201/eid1207.051531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Witt A. S. A., Trindade G. S., Souza F. G., et al., “Ultrastructural Analysis of Monkeypox Virus Replication in Vero Cells,” Journal of Medical Virology 95, no. 2 (2023): e28536, 10.1002/jmv.28536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andrieu J., Valade M., Lebideau M., et al., “Pan‐Microscopic Examination of Monkeypox Virus in Trophoblasts Cells Reveals New Insights Into Virions Release Through Filopodia‐Like Projections,” Journal of Medical Virology 96, no. 4 (2024): e29620, 10.1002/jmv.29620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parker S., Nuara A., Buller R. M. L., and Schultz D. A., “Human Monkeypox: An Emerging Zoonotic Disease,” Future Microbiology 2, no. 1 (2007): 17–34, 10.2217/17460913.2.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang S., Wang F., Peng Y., et al., “Evolutionary Trajectory and Characteristics of Mpox Virus in 2023 Based on a Large‐Scale Genomic Surveillance in Shenzhen, China,” Nature Communications 15, no. 1 (2024): 7452, 10.1038/s41467-024-51737-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu Y., Wu Y., Zhang Y., et al., “Cryo‐EM Structures of Human Monkeypox Viral Replication Complexes With and Without DNA Duplex,” Cell Research 33, no. 6 (2023): 479–482, 10.1038/s41422-023-00796-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Monzón S., Varona S., Negredo A., et al., “Monkeypox Virus Genomic Accordion Strategies,” Nature Communications 15, no. 1 (2024): 3059, 10.1038/s41467-024-46949-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shchelkunov S. N., Totmenin A. V., Babkin I. V., et al., “Human Monkeypox and Smallpox Viruses: Genomic Comparison,” FEBS Letters 509, no. 1 (2001): 66–70, 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martínez‐Fernández D. E., Fernández‐Quezada D., Casillas‐Muñoz F. A. G., et al., “Human Monkeypox: A Comprehensive Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention Strategies,” Pathogens 12, no. 7 (2023): 947, 10.3390/pathogens12070947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tiee M. S., Harrigan R. J., Thomassen H. A., and Smith T. B., “Ghosts of Infections Past: Using Archival Samples to Understand a Century of Monkeypox Virus Prevalence Among Host Communities Across Space and Time,” Royal Society Open Science 5, no. 1 (2018): 171089, 10.1098/rsos.171089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Babkin I. V., Babkina I. N., and Tikunova N. V., “An Update of Orthopoxvirus Molecular Evolution,” Viruses 14, no. 2 (2022): 388, 10.3390/v14020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Babkin I. V. and Babkina I. N., “A Retrospective Study of the Orthopoxvirus Molecular Evolution,” Infection, Genetics and Evolution 12, no. 8 (2012): 1597–1604, 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ulaeto D., Agafonov A., Burchfield J., et al., “New Nomenclature for Mpox (Monkeypox) and Monkeypox Virus Clades,” Lancet Infectious Diseases 23, no. 3 (2023): 273–275, 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00055-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Likos A. M., Sammons S. A., Olson V. A., et al., “A Tale of Two Clades: Monkeypox Viruses,” Journal of General Virology 86, no. Pt 10 (2005): 2661–2672, 10.1099/vir.0.81215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen N., Li G., Liszewski M. K., et al., “Virulence Differences Between Monkeypox Virus Isolates From West Africa and the Congo Basin,” Virology 340, no. 1 (2005): 46–63, 10.1016/j.virol.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yinka‐Ogunleye A., Aruna O., Dalhat M., et al., “Outbreak of Human Monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017–18: A Clinical and Epidemiological Report,” Lancet Infectious Diseases 19, no. 8 (2019): 872–879, 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30294-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weaver J. R. and Isaacs S. N., “Monkeypox Virus and Insights Into Its Immunomodulatory Proteins,” Immunological Reviews 225, no. 1 (2008): 96–113, 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Americo J. L., Earl P. L., and Moss B., “Virulence Differences of Mpox (Monkeypox) Virus Clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a Small Animal Model,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, no. 8 (2023): e2220415120, 10.1073/pnas.2220415120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bunge E. M., Hoet B., Chen L., et al., “The Changing Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox—A Potential Threat? A Systematic Review,” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 16 (2022): e0010141, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Otu A., Ebenso B., Walley J., Barceló J. M., and Ochu C. L., “Global Human Monkeypox Outbreak: Atypical Presentation Demanding Urgent Public Health Action,” Lancet Microbe 3, no. 8 (2022): e554–e555, 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Masirika L. M., Kumar A., Dutt M., et al., “Complete Genome Sequencing, Annotation, and Mutational Profiling of the Novel Clade I Human Mpox Virus, Kamituga Strain,” Journal of Infection in Developing Countries 18, no. 04 (2024): 600–608, 10.3855/jidc.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brown K. and Leggat P., “Human Monkeypox: Current State of Knowledge and Implications for the Future,” Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 1, no. 1 (2016): 8, 10.3390/tropicalmed1010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. ECDPC . Mise à jour épidémiologique: épidémie de variole du singe, Centre européen de prévention et de contrôle des maladies. Published online 2022.

- 47. Peter O. J., Kumar S., Kumari N., Oguntolu F. A., Oshinubi K., and Musa R., “Transmission Dynamics of Monkeypox Virus: A Mathematical Modelling Approach,” Modeling Earth Systems and Environment 8, no. 3 (2022): 3423–3434, 10.1007/s40808-021-01313-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Choudhary O. P., Priyanka O. P., Chopra H., et al., “Reverse Zoonosis and Its Relevance to the Monkeypox Outbreak 2022,” New Microbes and New Infections 49–50 (2022): 101049, 10.1016/j.nmni.2022.101049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kozlov M., “How Does Monkeypox Spread? What Scientists Know,” Nature 608, no. 7924 (2022): 655–656, 10.1038/d41586-022-02178-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pan D., Nazareth J., Sze S., et al., “Transmission of Monkeypox/Mpox Virus: A Narrative Review of Environmental, Viral, Host, and Population Factors in Relation to the 2022 International Outbreak,” Journal of Medical Virology 95, no. 2 (2023): e28534, 10.1002/jmv.28534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lansiaux E., Jain N., Laivacuma S., and Reinis A., “The Virology of Human Monkeypox Virus (hMPXV): A Brief Overview,” Virus Research 322 (2022): 198932, 10.1016/j.virusres.2022.198932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mucker E. M., Thiele‐Suess C., Baumhof P., and Hooper J. W., “Lipid Nanoparticle Delivery of Unmodified mRNAs Encoding Multiple Monoclonal Antibodies Targeting Poxviruses in Rabbits,” Molecular Therapy ‐ Nucleic Acids 28 (2022): 847–858, 10.1016/j.omtn.2022.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lu J., Xing H., Wang C., et al., “Mpox (Formerly Monkeypox): Pathogenesis, Prevention and Treatment,” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 8, no. 1 (2023): 458, 10.1038/s41392-023-01675-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huang Y., Mu L., and Wang W., “Monkeypox: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention,” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 7, no. 1 (2022): 373, 10.1038/s41392-022-01215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McCollum A. M. and Damon I. K., “Human Monkeypox,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 58, no. 2 (2014): 260–267, 10.1093/cid/cit703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bryer J., Freeman E. E., and Rosenbach M., “Monkeypox Emerges on a Global Scale: A Historical Review and Dermatologic Primer,” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 87, no. 5 (2022): 1069–1074, 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jaiswal V., Nain P., Mukherjee D., et al., “Symptomatology, Prognosis, and Clinical Findings of Monkeypox Infected Patients During COVID‐19 Era: A Systematic‐Review,” Immunity, Inflammation and Disease 10, no. 11 (2022): e722, 10.1002/iid3.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vaughan A. M., Cenciarelli O., Colombe S., et al., “A Large Multi‐Country Outbreak of Monkeypox Across 41 Countries in the WHO European Region, 7 March to 23 August 2022,” Euro Surveillance: Bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 27, no. 36 (2022): 2200620, 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.36.2200620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thornhill J. P., Barkati S., Walmsley S., et al., “Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans Across 16 Countries ‐ April‐June 2022,” New England Journal of Medicine 387, no. 8 (2022): 679–691, 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Orviz E., Negredo A., Ayerdi O., et al., “Monkeypox Outbreak in Madrid (Spain): Clinical and Virological Aspects,” Journal of Infection 85, no. 4 (2022): 412–417, 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Saijo M., Ami Y., Suzaki Y., et al., “Virulence and Pathophysiology of the Congo Basin and West African Strains of Monkeypox Virus in Non‐Human Primates,” Journal of General Virology 90, no. 9 (2009): 2266–2271, 10.1099/vir.0.010207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gessain A., Nakoune E., Yazdanpanah Y., et al., “Monkeypox,” New England Journal of Medicine 38 (2022): 1783–1793, 10.1056/NEJMra2208860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lopera J. G., Falendysz E. A., Rocke T. E., and Osorio J. E., “Attenuation of Monkeypox Virus by Deletion of Genomic Regions,” Virology 475 (2015): 129–138, 10.1016/j.virol.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Liszewski M. K., Leung M. K., Hauhart R., et al., “Structure and Regulatory Profile of the Monkeypox Inhibitor of Complement: Comparison to Homologs in Vaccinia and Variola and Evidence for Dimer Formation,” Journal of Immunology 176, no. 6 (2006): 3725–3734, 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Johnson R. F., Dyall J., Ragland D. R., et al., “Comparative Analysis of Monkeypox Virus Infection of Cynomolgus Macaques by the Intravenous or Intrabronchial Inoculation Route,” Journal of Virology 85, no. 5 (2011): 2112–2125, 10.1128/JVI.01931-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nagata N., Saijo M., Kataoka M., et al., “Pathogenesis of Fulminant Monkeypox With Bacterial Sepsis After Experimental Infection With West African Monkeypox Virus in a Cynomolgus Monkey,” International journal of clinical and experimental pathology 7, no. 7 (2014): 4359–4370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Song H., Josleyn N., Janosko K., et al., “Monkeypox Virus Infection of Rhesus Macaques Induces Massive Expansion of Natural Killer Cells but Suppresses Natural Killer Cell Functions,” PLoS One 8, no. 10 (2013): e77804, 10.1371/journal.pone.0077804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Earl P. L., Americo J. L., and Moss B., “Natural Killer Cells Expanded In Vivo or Ex Vivo with IL‐15 Overcomes the Inherent Susceptibility of CAST Mice to Lethal Infection With Orthopoxviruses,” PLoS Pathogens 16, no. 4 (2020): e1008505, 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jayaraman A., Jackson D. J., Message S. D., et al., “IL‐15 Complexes Induce NK‐ and T‐Cell Responses Independent of Type I IFN Signaling During Rhinovirus Infection,” Mucosal Immunology 7, no. 5 (2014): 1151–1164, 10.1038/mi.2014.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Johnston S. C., Johnson J. C., Stonier S. W., et al., “Cytokine Modulation Correlates With Severity of Monkeypox Disease in Humans,” Journal of Clinical Virology 63 (2015): 42–45, 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kisalu N. K. and Mokili J. L., “Toward Understanding the Outcomes of Monkeypox Infection in Human Pregnancy,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 216, no. 7 (2017): 795–797, 10.1093/infdis/jix342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mbala P. K., Huggins J. W., Riu‐Rovira T., et al., “Maternal and Fetal Outcomes Among Pregnant Women With Human Monkeypox Infection in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 216, no. 7 (2017): 824–828, 10.1093/infdis/jix260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pittman P. R., Martin J. W., Kingebeni P. M., et al., “Clinical Characterization and Placental Pathology of Mpox Infection in Hospitalized Patients in the Democratic Republic of the Congo,” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 17 (2023): e0010384, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ogoina D., Iroezindu M., James H. I., et al., “Clinical Course and Outcome of Human Monkeypox in Nigeria,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 71, no. 8 (2020): e210–e214, 10.1093/cid/ciaa143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. World Health Organization . Multi‐Country Outbreak of Mpox, External Situation Report #25–24 June 2023, Edition 24. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/multi-country-outbreak-mpox-monkeypox-external-situation-report-25-published-24-june-2023. Published online July 7, 2023.

- 76. Luna N., Ramírez A. L., Muñoz M., et al., “Phylogenomic Analysis of the Monkeypox Virus (MPXV) 2022 Outbreak: Emergence of a Novel Viral Lineage?,” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 49 (2022): 102402, 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hoffmann C., Jessen H., Wyen C., et al., “Clinical Characteristics of Monkeypox Virus Infections Among Men With and Without HIV: A Large Outbreak Cohort in Germany,” HIV Medicine 24, no. 4 (2023): 389–397, 10.1111/hiv.13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Girometti N., Byrne R., Bracchi M., et al., “Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Confirmed Human Monkeypox Virus Cases In Individuals Attending a Sexual Health Centre in London, UK: An Observational Analysis,” Lancet Infectious Diseases 22, no. 9 (2022): 1321–1328, 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00411-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rodriguez‐Morales A. J. and Amer F. A., “Monkeypox Virus Infection in Women and Non‐Binary People: Uncommon or Neglected?,” Lancet 400, no. 10367 (2022): 1903–1905, 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02396-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Oakley L. P., Hufstetler K., O'Shea J., et al., “Mpox Cases Among Cisgender Women and Pregnant Persons — United States, May 11–November 7, 2022,” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72, no. 1 (2023): 9–14, 10.15585/mmwr.mm7201a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Khalil A., Samara A., O'Brien P., et al., “Monkeypox in Pregnancy: Update on Current Outbreak,” Lancet Infectious Diseases 22, no. 11 (2022): 1534–1535, 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00612-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Brazil Ministry of Health . Boletim Epidemiológico de Monkeypox no 22 (COE). 23 May 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/variola-dos-macacos/boletim-epidemiologico-de-monkeypox-no-22-coe/view. Published online June 19, 2023.

- 83. Dashraath P., Nielsen‐Saines K., Rimoin A., Mattar C. N. Z., Panchaud A., and Baud D., “Monkeypox in Pregnancy: Virology, Clinical Presentation, and Obstetric Management,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 227, no. 6 (2022): 849–861.e7, 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Krabbe N. P., Mitzey A. M., Bhattacharya S., et al., “Mpox Virus (MPXV) Vertical Transmission and Fetal Demise in a Pregnant Rhesus Macaque Model,” preprint, bioRxiv, May 30, 2024, 10.1101/2024.05.29.596240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zaucha G. M., Jahrling P. B., Geisbert T. W., Swearengen J. R., and Hensley L., “The Pathology of Experimental Aerosolized Monkeypox Virus Infection in Cynomolgus Monkeys (Macaca fascicularis),” Laboratory Investigation 81, no. 12 (2001): 1581–1600, 10.1038/labinvest.3780373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chapman J. L., Nichols D. K., Martinez M. J., and Raymond J. W., “Animal Models of Orthopoxvirus Infection,” Veterinary Pathology 47, no. 5 (2010): 852–870, 10.1177/0300985810378649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Schwartz D. A., Ha S., Dashraath P., Baud D., Pittman P. R., and Adams Waldorf K. M., “Mpox Virus in Pregnancy, the Placenta, and Newborn,” Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 147, no. 7 (2023): 746–757, 10.5858/arpa.2022-0520-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Antonello V. S., Cornelio P. E., and Dallé J., “Disseminated Neonatal Monkeypox Virus Infection: Case Report in Brazil,” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 42, no. 5 (2023): e152–e153, 10.1097/INF.0000000000003848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ramnarayan P., Mitting R., Whittaker E., et al., “Neonatal Monkeypox Virus Infection,” New England Journal of Medicine 387, no. 17 (2022): 1618–1620, 10.1056/NEJMc2210828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Mukit F. A., Louie E. M., Cape H. T., and Bohn S. N., “A Suspected Case of a Neonatal Monkeypox Infection With Ocular Involvement,” Cureus 15, no. 5 (2023): e38819, 10.7759/cureus.38819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Soares M. L. C., Teixeira D. C., Pinto W. R., Coelho I. A., Matos J. C., and Romanelli R. M. C., “Newborn Exposed to the Monkeypox Virus: A Brief Report,” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 42, no. 8 (2023): e316, 10.1097/INF.0000000000003935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Dashraath P., Alves M. P., Schwartz D. A., Nielsen‐Saines K., and Baud D., “Potential Mechanisms of Intrauterine Transmission of Monkeypox Virus,” Lancet Microbe 4, no. 1 (2023): e14, 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Schwartz D. A. and Pittman P. R., “Mpox (Monkeypox) in Pregnancy: Viral Clade Differences and Their Associations With Varying Obstetrical and Fetal Outcomes,” Viruses 15, no. 8 (2023): 1649, 10.3390/v15081649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kumar A., Jhanwar P., B R., Gulati A., and Tatu U. Genomic Analyses of Recently Emerging Clades of Mpox Virus Reveal Gene Deletion and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms That Correlate With Altered Virulence and Transmission. 25, 2024, 10.1101/2024.09.24.614696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zaga‐Clavellina V., Diaz L., Olmos‐Ortiz A., Godínez‐Rubí M., Rojas‐Mayorquín A. E., and Ortuño‐Sahagún D., “Central Role of the Placenta During Viral Infection: Immuno‐Competences and Mirna Defensive Responses,” Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular Basis of Disease 1867, no. 10 (2021): 166182, 10.1016/j.bbadis.2021.166182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Fuentes‐Zacarías P., Murrieta‐Coxca J. M., Gutiérrez‐Samudio R. N., et al., “Pregnancy and Pandemics: Interaction of Viral Surface Proteins and Placenta Cells,” Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular Basis of Disease 1867, no. 11 (2021): 166218, 10.1016/j.bbadis.2021.166218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Fried M., Domingo G. J., Gowda C. D., Mutabingwa T. K., and Duffy P. E., “Plasmodium Falciparum: Chondroitin Sulfate A Is the Major Receptor for Adhesion of Parasitized Erythrocytes in the Placenta,” Experimental Parasitology 113, no. 1 (2006): 36–42, 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hsiao J. C., Chung C. S., and Chang W., “Vaccinia Virus Envelope D8L Protein Binds to Cell Surface Chondroitin Sulfate and Mediates the Adsorption of Intracellular Mature Virions to Cells,” Journal of Virology 73, no. 10 (1999): 8750–8761, 10.1128/JVI.73.10.8750-8761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Chung C. S., Hsiao J. C., Chang Y. S., and Chang W., “A27L Protein Mediates Vaccinia Virus Interaction With Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate,” Journal of Virology 72, no. 2 (1998): 1577–1585, 10.1128/JVI.72.2.1577-1585.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Lin C. L., Chung C. S., Heine H. G., and Chang W., “Vaccinia Virus Envelope H3L Protein Binds to Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate and Is Important for Intracellular Mature Virion Morphogenesis and Virus Infection In Vitro and In Vivo,” Journal of Virology 74, no. 7 (2000): 3353–3365, 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3353-3365.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Russo A. T., Grosenbach D. W., Chinsangaram J., et al., “An Overview of Tecovirimat for Smallpox Treatment and Expanded Anti‐Orthopoxvirus Applications,” Expert Review of Anti‐Infective Therapy 19, no. 3 (2021): 331–344, 10.1080/14787210.2020.1819791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Matias W. R., Koshy J. M., Nagami E. H., et al., “Tecovirimat for the Treatment of Human Monkeypox: An Initial Series From Massachusetts, United States,” Open Forum Infectious Diseases 9, no. 8 (2022): ofac377, 10.1093/ofid/ofac377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text.