Abstract

Introduction

Anemia is a prevalent public health issue affecting millions worldwide, particularly among vulnerable populations. This study examines anemia prevalence among Iran's Kurdish population, revealing socioeconomic inequality and emphasizing the need for targeted interventions.

Materials & methods

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted in 2019 using baseline data from the Dehgolan Prospective Cohort Study, involving 3,869 adults aged 35–70. Anemia was defined according to WHO guidelines, and socioeconomic status was assessed through household asset indices and educational attainment. Logistic regression and concentration index methods were employed to analyze the data.

Results

The prevalence of anemia was found to be 4.4%, with a higher rate in females (6.1%) compared to males (2.2%). Significant disparities were observed based on education and wealth, with illiterate individuals showing a prevalence of 5.5%. The analysis revealed that education and gender were the most influential factors contributing to socioeconomic inequality in anemia prevalence.

Conclusion

The study highlights the critical role of socioeconomic factors in the prevalence of anemia among the Kurdish population. Addressing these inequalities is essential for improving health outcomes and developing effective public health strategies.

Keywords: Anemia, Socioeconomic factors, Inequality, Kurdish population, Health disparities

Introduction

Anemia is a significant public health concern due to its high prevalence and impact on adults'health and well-being. It may result in symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, palpitations, tachycardia and impaired cognitive function [1, 2]. In adults, can lead to decreased work productivity, and increased healthcare costs [3]. By disrupting oxygenation, and reducing exercise tolerance and quality of life, it's one of the main determinants of the complications of various diseases worldwide. [4, 5] Hemoglobin levels were assessed through complete blood count (CBC) using the Sysmex XP- 300 analyzer to determine anemia status based on World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines [6]. Iron deficiency anemia was classified as having a hemoglobin concentration of less than 13 g/dL in males and less than 12 g/dL in females. These cutoff values are widely accepted as the thresholds for diagnosing anemia, as hemoglobin levels below these concentrations are associated with impaired oxygen-carrying capacity and increased risk of adverse health outcomes.

The global prevalence of anemia across all age was estimated of 22.8% corresponding to 1.2 prevalent cases. A significant disparity in the prevalence of anemia has been noted across different demographic groups and geographic regions. Children under the age of 5, women, and countries within sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia have been identified as particularly vulnerable to the burden of anemia [7].The burden of anemia has affected 27% of the world's population so developing countries alone account for more than 89%. [8] recently a large study reported the prevalence of anemia among Iranian adults aged 35 and above at 8.83% [9].

Anemia arises from a complex interplay of factors, with iron deficiency being the predominant cause. Various correlates based on its underlying pathophysiology, such as infectious diseases, nutritional deficiencies and chronic conditions are generally the most common pathogenesis of anemia [10]. Predisposing socioeconomic factors have a significant influence on human health. In developing areas, lower socioeconomic households often have higher rates of anemia [11]. Addressing these disparities is crucial for improving health and reducing inequalities. Understanding the impact of socioeconomic factors allows for targeted interventions and policies to improve the well-being of vulnerable populations. Although there have been numerous reports of anemia among children, woman [12] and older adults [13], few studies attempt to investigate anemia in younger adults of general population and its underlying socioeconomic disparity in minority population. Despite the growing body of literature on anemia, there remains a significant gap in understanding its prevalence and the socioeconomic factors influencing it specifically among minority populations in Iran, particularly the Kurdish community. Previous studies, such as those by Akbarpour [14], Zamani [15] and Mashreghi [16], have primarily focused on broader demographics without delving into specific ethnic or socioeconomic disparities. In contrast, numerous studies have been conducted in other countries and regions examining the socio-economic status and its relationship with anemia across various populations [17–19]. This highlights the necessity of our study, as addressing these gaps is essential for developing targeted health interventions that can effectively reduce anemia prevalence in this vulnerable population. Therefor we utilized data from Dehgolan prospective cohort study (DehPCS) to estimate prevalence and underling factors of anemia and its socioeconomic inequality in Kurd population in west of Iran.

Materials and methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2019, involving individuals participated in the enrollment phase of the DehPCS, which is a part of the larger PERSIAN cohort study [20]. Dehgolan is located in the southern part of Kurdistan Province in Iran. The region has a population of approximately 68,000, predominantly consisting of Kurds ethnic. Its economy is largely centered around agriculture. The detailed information on the DehPCS has been explained elsewhere [21]. Briefly the purpose of this cohort study was to identify the risk factors of the most common non-communicable diseases in the Kurd population. Participants were recruited in this study with a systematic random 1-stage cluster sampling method. We carried out a comprehensive census and subsequently selected 50% of the 721 blocks using systematic random sampling. The initial block for sampling was determined randomly. The process began with the first building located on the right-hand side of the nearest street to the cohort study center. All households within the selected blocks were thoroughly assessed, and participants were chosen based on predefined eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria consisted of individuals aged 35–70, holding Iranian citizenship, and being permanent residents of Dehgolan with at least one year of residency and no intention to migrate. In this study, individuals with incomplete data on the required hematologic laboratory parameters were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, pregnant women, individuals with an untreated mental disorder such as psychosis and those who were unable to effectively answer questions were also excluded from the study sample. Finaly, out of 4400 individuals invited to participate, 404 declined, and 127 lacked laboratory data, resulting in a final sample size of 3869 participants. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUK.REC.1402.082). Written informed consent to participate in the survey was obtained from all participants.

Data collection and measurements

The data was collected using a structured checklist administered through in-person interviews conducted by a proficient interviewer fluent in Kurdish. The study included the collection of key demographic variables such as gender, age, and marital status. Participants were classified into three distinct smoking status categories: current smokers with a history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, individuals who had quit smoking, and those who had never smoked [22]. The criteria for alcohol consumption are met when an individual drinks at least one standard alcoholic drink per week for a minimum duration of 6 months. This standard drink is defined as 200 mL of beer or 45 mL of other alcoholic beverage, consumed once a week for at least 6 months [23]. Similarly, the use of drugs is classified as Illicit/illegal drug use when it occurs at least once a week for a minimum duration of 6 months.

The Body Mass Index (BMI) was determined by dividing the participant's weight in kilograms by the square of their height in meters (kg/m2). According to the guidelines set by the World Health Organization (WHO) [24], participants were categorized into three BMI groups. Those with a BMI ≤ 24.9 kg/m2 were classified as having a normal weight. Individuals with a BMI ranging from 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2 were categorized as overweight, while those with a BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 were classified as obese. Physical activity levels were evaluated by utilizing the metabolic equivalent of task (MET) as a standardized measure of energy expenditure across different activities. This allowed for the calculation of MET values for each participant based on their self-reported physical activity over a 24-h period [25].

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status (SES) was evaluated by considering both household asset index and educational attainment. The asset index was developed using the principal component analysis (PCA) method, and the data were segmented into five quartiles based on the index scores [26]. This household asset index served as a composite measure of wealth, taking into account the ownership of assets like a house and the area of living space (measured in square meters), as well as possession of items such as a mobile phone, laptop or PC, are considered. Additional assets include appliances like a freezer, washing machine, dishwasher, vacuum cleaner, and types of televisions (regular color TV or Plasma TV). Other factors include access to the internet, owning a motorcycle, and having a car. It functioned as a proxy for long-term economic status, allowing for the ranking of households based on their asset index score and categorization into wealth quintiles. The participants'educational attainment was categorized based on the highest level of education completed and the number of years spent on education. The categories for education were defined as follows: illiterate, indicating zero years of education; 1–6 years of education; 7–12 years of education; and university, indicating completion of more than 12 years of education.

Statistical analysis

In this research, participant data was analyzed with STATA version 17 software. The study calculated the prevalence of anemia and used summary statistics (mean and standard deviation for continuous variables; frequency and percentage for categorical variables) to describe sample characteristics. Additionally, logistic regression was employed to explore the relationship between the outcome variable and predictor variables, considering potential confounding factors. The study assessed socioeconomic inequality using the concentration curve and concentration index. Concentration curve depict the cumulative percentage of participants ranked by SES (y-axis) relative to the cumulative percentage of the anemia outcome variable (x-axis). To quantify inequality, the concentration index was calculated using the standardized Wagstaff formula (Eq. 1), which denote mean value of outcome y, n is the sample size and R denotes the individual’s fractional rank in the asset distribution. which yields a value between − 1 and 1, where zero represents perfect equality [27]. Additionally, the concentration index decomposition method was applied to quantify the contribution of various determinants to anemia inequality. Statistical significance for all analyses was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05.

| 1 |

Results

The study involved 3,869 participants, of which 2,176 (56.2%) were women. The mean age of participants was 48.4 ± 8.9 with the majority (89.4%) belonging to the age group of 35–60 years. 31.3% of participants was illiterate and 12.9% had more than 12 years of education experience (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of anemia and their association with socioeconomic variables in multivariable logistic regression among Dehgolan Prospective Cohort Study participants

| Variables | N (%)a | Anemia status | Adjusted odds ratio (95%CI)b | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 2176 (56.24%) | 133 | 6.11% | Ref | |

| Male | 1693 (43.75%) | 38 | 2.24% | 0.43 (0.26–0.70) | 0.001 |

| Age categories | |||||

| 35–45 | 1894 (48.95%) | 90 | 4.75% | Ref | |

| 46–60 | 1565 (40.44%) | 64 | 4.09% | 0.77 (0.52–1.13) | 0.187 |

| ≥ 61 | 410 (10.61%) | 17 | 4.15% | 0.69(0.37–1.28) | 0.235 |

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 1201 (31.34%) | 66 | 5.50% | Ref | |

| 1–5 | 1093 (28.52%) | 56 | 5.12% | 1.03 (0.67–1.59) | 0.878 |

| 6–12 | 1042 (27.19%) | 38 | 3.65% | 0.80 (0.46–1.40) | 0.444 |

| University | 496 (12.94%) | 8 | 1.61% | 0.37 (0.14–0.94) | 0.038 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 3517 (91.77%) | 149 | 4.24% | - | |

| Single | 315 (8.22%) | 19 | 6.03% | - | |

| Job | |||||

| No | 2009 (52.64%) | 118 | 5.87% | - | |

| Yes | 1807 (47.35%) | 50 | 2.77% | - | |

| Chronic disease | |||||

| No | 2136 (55.43%) | 85 | 3.98% | - | |

| Yes | 1717 (44.56%) | 86 | 5.01% | - | |

| Smoking | |||||

| No smoker | 2929 (76.53%) | 142 | 4.85% | Ref | |

| Ex-smoker | 317 (8.28%) | 14 | 4.42% | 1.56 (0.84–2.89) | 0.151 |

| Smoker | 581 (15.18%) | 15 | 2.58% | 1.06 (0.57–1.99) | 0.831 |

| Use alcohol | |||||

| No | 3327 (87.76%) | 161 | 4.84% | Ref | |

| Yes | 464 (12.23%) | 7 | 1.51% | 0.46 (0.20–1.04) | 0.062 |

| Use drugs | |||||

| No | 3352 (88.44%) | 157 | 4.68% | - | |

| Yes | 438 (11.55%) | 11 | 2.51% | - | |

| BMI d | |||||

| < 25 | 953 (24.69%) | 43 | 4.51% | Ref | |

| 25–29.9 | 1652 (42.80%) | 69 | 4.18% | 0.72 (0.48–1.08) | 0.117 |

| ≥ 30 | 1254 (32.49%) | 59 | 4.70% | 0.69 (0.45–1.07) | 0.099 |

| Met category | |||||

| Low | 1566 (40.81%) | 66 | 4.21% | - | |

| Moderate | 1736 (45.24%) | 88 | 5.07% | - | |

| Vigorous | 535 (13.94%) | 17 | 3.18% | - | 3790 |

| Socio-economic status | |||||

| Q1 (poorest) | 750 (19.78%) | 47 | 6.27% | Ref | |

| Q2 | 757 (19.97%) | 31 | 4.10% | 0.69 (0.43–1.11) | 0.125 |

| Q3 | 757 (19.97%) | 33 | 4.36% | 0.82 (0.51 − 1.32) | 0.412 |

| Q4 | 767 (20.23%) | 32 | 4.17% | 0.89 (0.54–1.46) | 0.0.640 |

| Q5 (richest) | 759 (20.02%) | 24 | 3.16% | 0.96 (0.53–1.74) | 0.906 |

| Total | |||||

an (%) = number (percent)

bCI = Confidence interval

dBMI: Body Massive Index

The findings indicate a total prevalence of anemia was 4.4% (95% CI, 3.5–5.1), with 2.72 percentage points higher in females (6.11%) compared to males (2.24%). Anemia prevalence was 3.89 percentage points higher in the illiterate group (5.50%) compared to those who had more than 12 years of education experience (1.61%). Furthermore, anemia increased across wealth index quantiles, with the prevalence in the poorest group being about 2 times higher than in the richest group. Additionally, individuals with no history of alcohol and drug use had approximately 3 times and 1.9 times higher prevalence of anemia compared to users, respectively (Table 1).

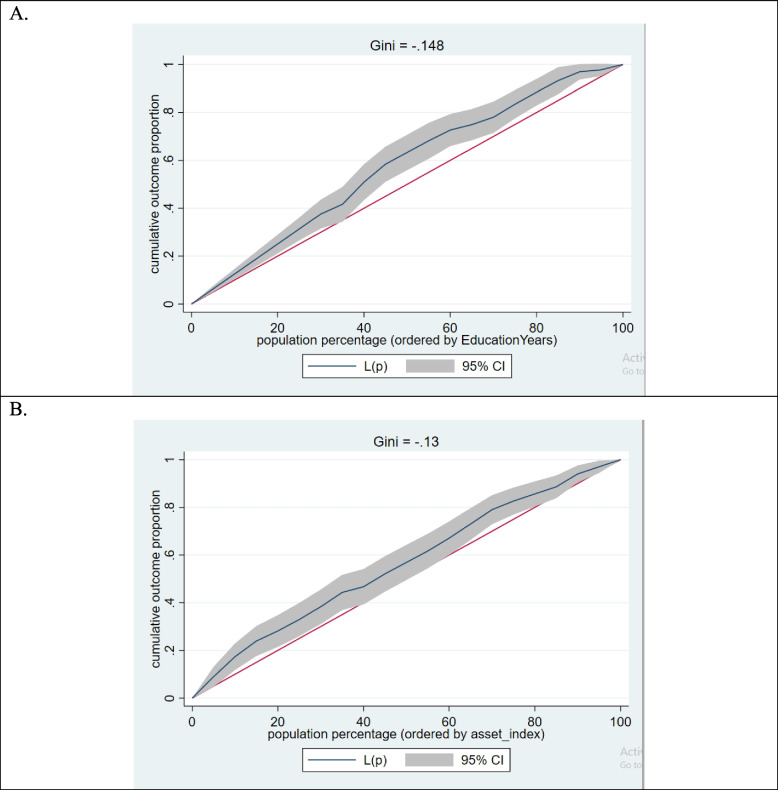

The normalized concentration index values for wealth index and education level indicate a significant concentration of anemia among the socioeconomically disadvantaged population. Table 2 and Fig. 1, indicating negative CI values of − 0.135 and − 0.155 for wealth index and education level, respectively, highlight the extent of this concentration.

Table 2.

Socioeconomic-related inequality for prevalence of Iron deficiency anemia

| Normalized concentration index | Confidence interval 95% | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth index | − 0.135 | − 0.046, − 0.225 | 0.003 |

| Education level | − 0.155 | − 0.068, − 0.243 | 0.0005 |

Fig. 1.

Concentration Index (CI) Values for Education and Asset Index. A illustrates the negative concentration index value of − 0.155 for education level, B shows a CI of − 0.135 for the wealth index. Concentration curve 1. The cumulative outcome proportion of anemia by education years

To identify the various contributors to socioeconomic inequality in anemia, we conducted a multiple logistic regression analysis. The final model, as shown in Tables 3 and 4, includes gender, age, education level, smoking, alcohol use, BMI categories, and wealth index quintile as potential contributors to inequality.

Table 3.

The decomposition analysis results for anemia based on the asset index

| Coefficient | Mean | Elasticity | Concentration index | Contribution | Contribution Sum | Percentage contribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Reference: female | − 0.035 | 0.44 | − 0.35 | 0.19 | − 0.066 | − 0.07 | 51.04 |

| Age groups | Reference: 35–45 | 0.02 | − 13.45 | |||||

| 46–60 | − 0.011 | 0.40 | − 0.10 | − 0.04 | 0.004 | |||

| > 60 | − 0.015 | 0.10 | − 0.04 | − 0.36 | 0.013 | |||

| Education | Reference: Illiterate | − 0.07 | 55.21 | |||||

| 1–5 | 0.002 | 0.29 | 0.01 | − 0.08 | − 0.001 | |||

| 6–12 | − 0.009 | 0.27 | − 0.06 | 0.20 | − 0.011 | |||

| > 12 | − 0.030 | 0.13 | − 0.09 | 0.67 | − 0.059 | |||

| SES | Reference: poorest | 0.01 | − 9.10 | |||||

| Poor | − 0.015 | 0.20 | − 0.07 | − 0.40 | 0.027 | |||

| middle | − 0.009 | 0.20 | − 0.04 | − 0.01 | 0.0002 | |||

| rich | − 0.005 | 0.20 | − 0.02 | 0.40 | − 0.010 | |||

| very rich | − 0.002 | 0.20 | − 0.01 | 0.80 | − 0.006 | |||

| BMI | Reference: < 24.9 | − 0.01 | 3.97 | |||||

| 25–29.9 | − 0.015 | 0.43 | − 0.15 | 0.06 | − 0.008 | |||

| > = 30 | − 0.016 | 0.32 | − 0.12 | − 0.02 | 0.003 | |||

| Smoking status | Smoking status | 0.00 | 1.22 | |||||

| ex | 0.022 | 0.08 | 0.04 | − 0.04 | − 0.002 | |||

| smoker | 0.003 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.000 | |||

| Alcohol use | Reference: No | − 0.033 | 0.12 | − 0.09 | 0.15 | − 0.013 | − 0.01 | 10.44 |

| sum | − 0.128 | 99.335 | ||||||

| Resi | − 0.001 | 0.665 | ||||||

| Anemia P | 0.044 | |||||||

| CI | − 0.129 |

Table 4.

The decomposition analysis results for anemia based on the education status

| Coefficient | Mean | Elasticity | Concentration index | Contribution | Contribution Sum | Percentage contribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Reference: female | − 0.035 | 0.44 | − 0.35 | 0.20 | − 0.070 | − 0.070 | 47.00 |

| Age groups | Reference: 35–45 | 0.038 | − 25.67 | |||||

| 46–60 | − 0.011 | 0.40 | − 0.10 | − 0.20 | 0.021 | |||

| > 60 | − 0.015 | 0.10 | − 0.04 | − 0.48 | 0.017 | |||

| Education | Reference: Illiterate | − 0.104 | 70.31 | |||||

| 1–5 | 0.002 | 0.29 | 0.01 | − 0.09 | − 0.001 | |||

| 6–12 | − 0.009 | 0.27 | − 0.06 | 0.46 | − 0.026 | |||

| > 12 | − 0.030 | 0.13 | − 0.09 | 0.87 | − 0.077 | |||

| SES | Reference: poorest | 0.012 | − 8.13 | |||||

| Poor | − 0.015 | 0.20 | − 0.07 | − 0.25 | 0.017 | |||

| middle | − 0.009 | 0.20 | − 0.04 | − 0.06 | 0.002 | |||

| rich | − 0.005 | 0.20 | − 0.02 | 0.14 | − 0.003 | |||

| very rich | − 0.002 | 0.20 | − 0.01 | 0.56 | − 0.004 | |||

| BMI | Reference: < 24.9 | 0.008 | − 5.68 | |||||

| 25–29.9 | − 0.015 | 0.43 | − 0.15 | 0.06 | − 0.009 | |||

| > = 30 | − 0.016 | 0.32 | − 0.12 | − 0.14 | 0.017 | |||

| Smoking status | Smoking status | − 0.001 | 0.63 | |||||

| ex | 0.022 | 0.08 | 0.04 | − 0.04 | − 0.002 | |||

| smoker | 0.003 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.001 | |||

| Alcohol use | Reference: No | − 0.033 | 0.12 | − 0.09 | 0.19 | − 0.018 | − 0.018 | 11.87 |

| Sum | − 0.134 | 90.343 | ||||||

| Resi | − 0.014 | 9.657 | ||||||

| Anemia P | 0.044 | |||||||

| CI | − 0.148 |

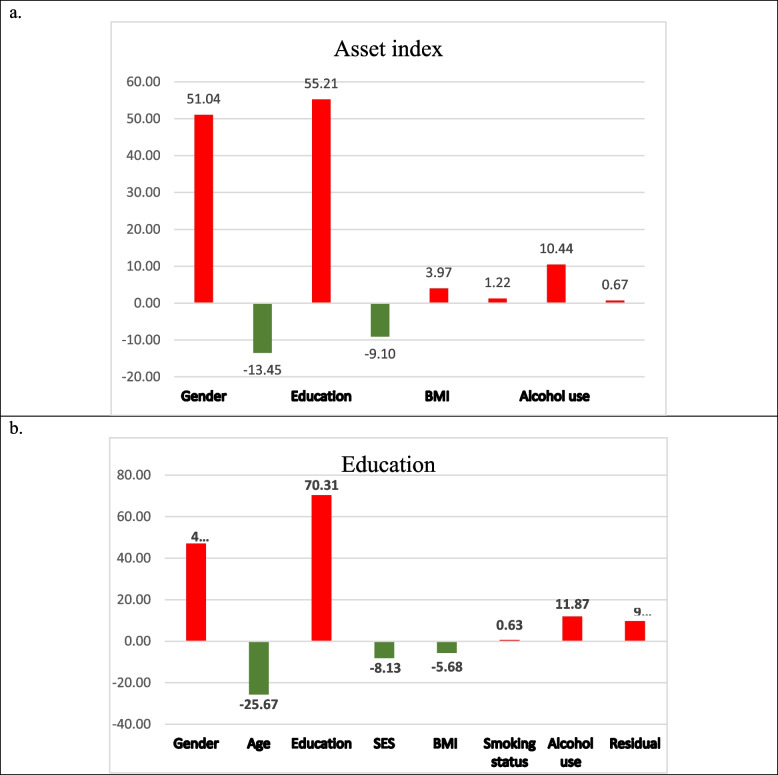

The distribution of wealth inequality in anemia is largely accounted for by several key factors, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The model indicates that a substantial 99.3% of wealth inequality can be attributed to the included variables. Notably, education and gender emerged as the most influential factors, contributing approximately 55.2% and 55.0% respectively to the overall wealth disparity. Conversely, age groups and wealth index exhibit a negative contribution of − 13.4% and − 9.1% respectively. These findings underscore the complex interplay of socio-economic factors in shaping wealth distribution within the anemia, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to address underlying disparities.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of Wealth Inequality in Anemia. A presents the asset index, highlighting its role in wealth distribution, while B focuses on education and its impact

The analysis of education inequality in anemia reveals that a significant portion, approximately 90.3%, of the disparity can be explained by key factors as depicted in Fig. 2b. Among these factors, education and gender stand out as the most influential, contributing around 70.3% and 47.0% respectively to the overall wealth gap. In contrast, age groups and wealth index show a negative contribution of − 25.7% and − 8.1% respectively.

Discussion

The findings of the study revealed that the prevalence of anemia in the studied population was 4.4%, with a significantly higher prevalence among women at 6.1%. Comparatively, the prevalence of anemia among American women was similarly reported to be 6.3% [28]. In urban residents of Brazil, the prevalence of anemia was reported to be 1.1%. In contrast, in Oman, the prevalence of anemia was estimated to be 26% in 2018 [29]. Petry et al. [30] underscored the necessity of distinguishing between various types of anemia and advocated for the customization of anemia -reduction strategies and programs due to the considerable heterogeneity in the prevalence of anemia across different countries [30, 31]. Their analysis revealed that in approximately 50% of the assessed countries, the proportion of anemia was lower than previously estimated. They documented that the prevalence of anemia ranged from 9.1% in Vietnam to 76.3% in Sierra Leone, while the prevalence of anemia varied from 0.1% in Georgia to 21.2% in Liberia [30].

The presented results derived from DehPCS showed that the prevalence of anemia was higher in females than in males. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have reported the association of anemia with gender and its biological and social determinants. [32–34] which is justified by the following reasons. Higher physiological requirements in females, food insecurity, poverty, or cultural practices, lower access to health services and preventive interventions, and more exposure to infections which contribute to anemia [35, 36]. Hence, it is critical to address the gender-specific variables of anemia among women and to design effective interventions that can improve their health [36, 37].

The concentration curve of anemia by SES and education was above the line of equality, showing that the low SES and education group had a higher prevalence of anemia which is in line with previous findings [38]. The logistic regression analysis results indicated that none of the variables were significantly associated with anemia. This means that the odds of anemia were not different across the categories of age, marital status, education, SES, and job which was similar to the results of some studies [39]. This finding is contrary to the previous studies, as they detailed that these socio-demographic variables are related to the predominance and chance of anemia in different populations [40–42]. Some possible explanations for this finding are the sample size to detect any significant differences in anemia among the subgroups of the participants; the measurement of anemia was based on a single hemoglobin test, which may not reflect the true anemia status of the participants; A more detailed or relevant classification of the socio-demographic variables would allow for a better comparison of anemia among the participants.

A person’s health and well-being can be influenced by various factors, such as smoking, BMI, drug use, alcohol use, chronic disease, and physical activity measured as metabolic equivalent of task (MET) category. According to a previous study, anemia risk was lower among past or current smokers, and hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were higher among current smokers [43]. However, another study reported that smoking elevated the levels of erythrocytes, hemoglobin, hematocrit, leukocytes, mean corpuscular volume, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, which could increase the likelihood of developing atherosclerosis, polycythemia vera, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and/or cardiovascular diseases [44]. These parameters were not assessed in our study, but they may have implications for our findings. Moreover, alcohol use was positively associated with anemia [43]. However, a study among traders in the Tamale metropolis of Ghana found no significant difference in anemia rates between alcohol consumers and non-consumers [45]. Furthermore, BMI and central obesity were directly related to anemia risk [43]. In conclusion, adopting a healthy lifestyle is an essential strategy to prevent and treat anemia.

This study investigated the socio-economic inequalities in anemia among the residents of Dehgolan city in Iran. The results showed that anemia was more prevalent and concentrated among the low SES group, especially among women. These findings suggest that anemia is a public health problem that is influenced by socio-economic determinants and requires appropriate interventions to reduce the disparities and improve the health outcomes of the population. The results of this study are consistent with previous studies that have reported the association of anemia with socio-economic factors such as education, wealth, occupation, and region [8, 41]. Education is an important factor that affects the nutritional status, health awareness, and health-seeking behavior of individuals [46]. Wealth is another factor that determines the access and affordability of health services and nutritious food. Occupation is related to physical activity, exposure to environmental hazards, and income level of individuals. The region is a factor that reflects the geographic, climatic, and cultural diversity of the population. Gender is a factor that influences the biological, social, and economic aspects of health [46, 47]. Therefore, addressing these factors is essential for reducing the burden of anemia and improving the quality of life of the affected individuals.

This study is strengthened by its large sample size and the consistency of the data, which enhance the reliability of the findings. However, the study has notable limitations. The cross-sectional design restricts causal inferences, and the urban setting may limit the generalizability of the results to rural populations. Additionally, important factors influencing anemia inequality such as dietary intake, genetic disorders, infectious diseases, and cultural practices were not measured or controlled for. Moreover, the potential confounding or interaction effects of unmeasured variables in the logistic regression analysis may have obscured the relationship between anemia and socio-demographic factors. For instance, dietary habits, genetic predispositions, and cultural practices can significantly impact anemia risk and may correlate with socio-demographic variables.

Conclusion

This study underscores the critical issue of inequality in anemia prevalence, revealing that socio-economic factors significantly contribute to this health disparity. With an overall prevalence of 4.4%, the data highlights that women and illiterate individuals are disproportionately affected, with anemia rates markedly higher in these groups. The concentration index values indicate a strong association between socio-economic status and anemia, with education and gender emerging as the most influential contributors to inequality. Notably, the analysis shows that approximately 99.3% of wealth inequality in anemia can be attributed to these socio-economic determinants. Furthermore, the findings reveal that education and gender account for a substantial portion of the disparities, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions. Addressing these inequalities is essential not only for improving anemia outcomes but also for promoting greater health equity among disadvantaged populations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the executive personnel for their assistance and to all individuals whose support and guidance have been invaluable throughout the course of this study.

Authors’ contributions

A.M., A.SH, and M.A. were involved in data collection and drafting the manuscript. Y.M. and F.M. contributed to the study's conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of results. P.M., Gh.M., N.M., A.M.B., and B.P. assisted with result interpretation and provided critical feedback on the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education has contributed to the funding used in the PERSIAN Cohort through Grant no 700/534.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences. The project was found to be by ethical principles and national norms and standards for conducting Medical Research in Iran. Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all participants'legal guardians. In cases where participants were illiterate or lacked formal education, informed consent was provided by an appropriate representative on their behalf.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kumar A, Sharma E, Marley A, Samaan MA, Brookes MJ. Iron deficiency anaemia: pathophysiology, assessment, practical management. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022;9(1):e000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andro M, Le Squere P, Estivin S, Gentric A. Anaemia and cognitive performances in the elderly: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20(9):1234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haas JD, Brownlie Tt. Iron deficiency and reduced work capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal relationship. J Nutr. 2001;131(2S-2):676S-88S; discussion 88S-90S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Martinsson A, Andersson C, Andell P, Koul S, Engström G, Smith JG. Anemia in the general population: prevalence, clinical correlates and prognostic impact. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Izaks GJ, Westendorp RG, Knook DL. The definition of anemia in older persons. JAMA. 1999;281(18):1714–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization 2011 [Available from: http://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf.

- 7.Gardner W, Kassebaum N. Global, regional, and national prevalence of anemia and its causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2020;4(Supplement_2):830-.

- 8.Kumar P, Sharma H, Sinha D. Socio-economic inequality in anaemia among men in India: a study based on cross-sectional data. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamani M, Poustchi H, Shayanrad A, Pourfarzi F, Farjam M, Noemani K, et al. Prevalence and determinants of anemia among Iranian population aged ≥35 years: A PERSIAN cohort-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2): e0263795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Karamzad N, Bragazzi NL, et al. Burden of anemia and its underlying causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Ozaltin E, Shankar AH, Subramanian SV. Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2123–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silla LM, Zelmanowicz A, Mito I, Michalowski M, Hellwing T, Shilling MA, et al. High prevalence of anemia in children and adult women in an urban population in southern Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7): e68805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosseini SR, Zabihi A, Ebrahimi SH, Jafarian Amiri SR, Kheirkhah F, Bijani A. The Prevalence of Anemia and its Association with Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults in North of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2018;18(4): e00431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akbarpour E, Paridar Y, Mohammadi Z, Mard A, Danehchin L, Abolnezhadian F, et al. Anemia prevalence, severity, types, and correlates among adult women and men in a multiethnic Iranian population: the Khuzestan Comprehensive Health Study (KCHS). BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamani M, Poustchi H, Shayanrad A, Pourfarzi F, Farjam M, Noemani K, et al. Prevalence and determinants of anemia among Iranian population aged≥ 35 years: A PERSIAN cohort–based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2): e0263795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mashreghi Y, Kheradmand M, Hedayatizadeh-Omran A, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Espahbodi F, Khademloo M, et al. Prevalence of anemia and related factors among Tabari cohort population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lokare PO, Karanjekar VD, Gattani PL, Kulkarni AP. A study of prevalence of anemia and sociodemographic factors associated with anemia among pregnant women in Aurangabad city, India. Annals of Nigerian Medicine. 2012;6(1):30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JY, Shin S, Han K, Lee KC, Kim JH, Choi YS, et al. Relationship between socioeconomic status and anemia prevalence in adolescent girls based on the fourth and fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(2):253–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le CHH. The prevalence of anemia and moderate-severe anemia in the US population (NHANES 2003–2012). PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11): e0166635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poustchi H, Eghtesad S, Kamangar F, Etemadi A, Keshtkar AA, Hekmatdoost A, et al. Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in Iran (the PERSIAN Cohort Study): Rationale, Objectives, and Design. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(4):647–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moradpour F, Ghaderi E, Moradi G, Zarei M, Bolbanabad AM, Piroozi B, et al. The Dehgolan Prospective Cohort Study (DehPCS) on non-communicable diseases in a Kurdish community in the west of Iran. Epidemiol Health. 2021;43: e2021075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC. tobacco_glossary: National Center for Health Statistics 2017. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/nchs/nhis/tobacco/tobacco_glossary.htm. Cited 2025 01.09

- 23.CDC. Alcohol's Effects on Health: Research-based information on drinking and its impact: National institute for health 2024 [cited 2025 01.09]. Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/what-standard-drink.

- 24.Committee WE. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:312–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prevention OoD, Promotion H. Physical activity guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008.

- 26.Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(6):459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagstaff A. The bounds of the concentration index when the variable of interest is binary, with an application to immunization inequality. Health Econ. 2005;14(4):429–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weyand AC, Chaitoff A, Freed GL, Sholzberg M, Choi SW, McGann PT. Prevalence of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in US females aged 12–21 years, 2003–2020. JAMA. 2023;329(24):2191–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alkindi S, Al Musalami A, Al Wahaibi H, Al Ghammari N, Panjwani V, Fawaz N, et al. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in the adult omani population. J Appl Hematol. 2018;9(1):11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petry N, Olofin I, Hurrell RF, Boy E, Wirth JP, Moursi M, et al. The proportion of anemia associated with iron deficiency in low, medium, and high human development index countries: a systematic analysis of national surveys. Nutrients. 2016;8(11):693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, De Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO vitamin and mineral nutrition information system, 1993–2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(4):444–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levi M, Simonetti M, Marconi E, Brignoli O, Cancian M, Masotti A, et al. Gender differences in determinants of iron-deficiency anemia: a population-based study conducted in four European countries. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(7):1573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akbarpour E, Paridar Y, Mohammadi Z, Mard A, Danehchin L, Abolnezhadian F, et al. Anemia prevalence, severity, types, and correlates among adult women and men in a multiethnic Iranian population: the Khuzestan Comprehensive Health Study (KCHS). BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO. Anaemia - World Health Organization (WHO) 2023 [Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/anaemia.

- 35.Feskens EJ, Bailey R, Bhutta Z, Biesalski H-K, Eicher-Miller H, Krämer K, et al. Women’s health: optimal nutrition throughout the lifecycle. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61(Suppl 1):1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beyene SD. The impact of food insecurity on health outcomes: empirical evidence from sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Food Research & Action Center. Hunger and health: the impact of poverty, food insecurity, and poor nutrition on health and well-being. Available from: https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/hunger-health-impact-poverty-food-insecurity-health-well-being.pdf.

- 38.Styszynski A, Mossakowska M, Chudek J, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Klich-Raczka A, Neumann-Podczaska A, et al. Prevalence of anemia in relation to socio-economic factors in elderly Polish population: the results of PolSenior study. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;69(1):75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoang NTD, Orellana L, Le TD, Gibson RS, Worsley A, Sinclair AJ, et al. Anaemia and Its Relation to Demographic, Socio-economic and Anthropometric Factors in Rural Primary School Children in Hai Phong City. Vietnam Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahamoud NK, Mwambi B, Oyet C, Segujja F, Webbo F, Okiria JC, et al. Prevalence of anemia and its associated socio-demographic factors among pregnant women attending an antenatal care clinic at Kisugu Health Center IV, Makindye Division, Kampala, Uganda. Journal of blood medicine. 2020;11:13-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Safiri S, Kolahi A-A, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Karamzad N, Bragazzi NL, et al. Burden of anemia and its underlying causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bishwajit G, Yaya S, Tang S, Hossain A, Fan Y, Akter M, et al. Association of Living Arrangement Conditions and Socioeconomic Differentials with Anemia Status among Women in Rural Bangladesh. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:4571686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paramastri R, Hsu CY, Lee HA, Lin LY, Kurniawan AL, Chao JC. Association between Dietary Pattern, Lifestyle, Anthropometric Status, and Anemia-Related Biomarkers among Adults: A Population-Based Study from 2001 to 2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malenica M, Prnjavorac B, Bego T, Dujic T, Semiz S, Skrbo S, et al. Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Haematological Parameters in Healthy Population. Med Arch. 2017;71(2):132–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anabire NG, Billak GD, Helegbe GK. Alcohol intake, smoking, self-medication practices and burden of anaemia among traders in Tamale metropolis of Ghana. BMC Res Notes. 2023;16(1):214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sunuwar DR, Singh DR, Pradhan PMS, Shrestha V, Rai P, Shah SK, et al. Factors associated with anemia among children in South and Southeast Asia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alao R, Nur H, Fivian E, Shankar B, Kadiyala S, Harris-Fry H. Economic inequality in malnutrition: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(12):e006906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.