Abstract

Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) plays essential roles in transcriptional control of muscle development. However, signaling pathways acting downstream of MEF2 are largely unknown. Here, we performed a microarray analysis using Mef2c-null mouse embryos and identified a novel MEF2-regulated gene encoding a muscle-specific protein kinase, Srpk3, belonging to the serine arginine protein kinase (SRPK) family, which phosphorylates serine/arginine repeat-containing proteins. The Srpk3 gene is specifically expressed in the heart and skeletal muscle from embryogenesis to adulthood and is controlled by a muscle-specific enhancer directly regulated by MEF2. Srpk3-null mice display a new entity of type 2 fiber-specific myopathy with a marked increase in centrally placed nuclei; while transgenic mice overexpressing Srpk3 in skeletal muscle show severe myofiber degeneration and early lethality. We conclude that normal muscle growth and homeostasis require MEF2-dependent signaling by Srpk3.

Keywords: Myocyte enhancer factor 2, transcriptional regulation, serine arginine protein kinase (SRPK), Stk23/Srpk3, centronuclear myopathy

Skeletal muscle differentiation is cooperatively controlled by two families of transcription factors, the myogenic basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) proteins and the myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) family of MADS domain proteins (Black and Olson 1998; Bailey et al. 2001; Pownall et al. 2002; Buckingham et al. 2003; Parker et al. 2003). Myogenic bHLH proteins, such as MyoD and myogenin, recognize a DNA sequence called an E box (CANNTG). Myogenic bHLH proteins associate and synergistically activate transcription with MEF2 factors, which bind to the A/T-rich DNA consensus [CTA-(A/T)4-TA-G/A]. Additionally, myogenic bHLH proteins activate their own expression and the expression of MEF2, while MEF2 stimulates expression of myogenic bHLH protein genes and the Mef2c gene (Cserjesi and Olson 1991; Lassar et al. 1991; Edmondson et al. 1992; Cheng et al. 1993; Yee and Rigby 1993; Wang et al. 2001; Teboul et al. 2002; Dodou et al. 2003). Such auto- and cross-regulatory interactions establish a mutually reinforcing circuit to achieve myogenesis.

The essential role of MEF2 in muscle development was first shown in Drosophila in which a loss-of-function mutation in the single MEF2 ortholog D-mef2 results in a complete block to differentiation of all muscle lineages: somatic, cardiac, and visceral (Bour et al. 1995; Lilly et al. 1995). In mice, the existence of four Mef2 genes—Mef2a, Mef2b, Mef2c, and Mef2d—with overlapping expression patterns makes it more difficult to assess the roles of these factors individually (Black and Olson 1998). Mice homozygous for a Mef2c-null allele show embryonic lethality around embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) caused by improper development of the heart (Lin et al. 1997). The mutant hearts do not undergo looping morphogenesis, the future right ventricle does not form, and a subset of cardiac muscle genes is not expressed. MEF2 has also been implicated in maintenance of the slow fiber phenotype of skeletal muscle, in the control of striated muscle energy metabolism, and in pathological remodeling of the adult heart in response to stress signaling (Black and Olson 1998; McKinsey et al. 2002).

In principle, MEF2 may regulate muscle-specific target genes directly, or it may act indirectly by controlling the expression of subordinate transcription factors or signaling molecules that act as intermediaries to connect MEF2 to downstream targets that themselves are not dependent on MEF2-binding sites in their cis-regulatory regions. Indeed, vast arrays of direct and indirect targets of MEF2 in skeletal muscle cells in culture were recently described (Blais et al. 2005).

In an effort to identify MEF2 target genes that serve as “downstream” effectors of MEF2 action during muscle development, we performed a microarray analysis using Mef2c-null embryos and identified a novel muscle-specific protein kinase Stk23/Srpk3, which is encoded by a direct MEF2 target gene. Srpk3-null mice display a new entity of centronuclear myopathy, while transgenic mice overexpressing Srpk3 in skeletal muscle show severe myofiber degeneration. These findings reveal an essential role for serine arginine protein kinase (SRPK)-mediated signaling in muscle growth and homeostasis downstream of MEF2 transcription factors.

Results

Srpk3: a novel muscle-specific protein kinase gene

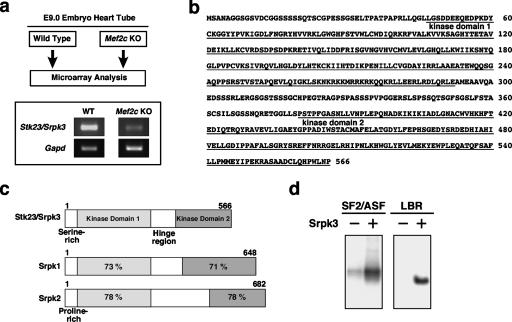

In an attempt to identify novel MEF2-regulated genes, we compared the gene expression profiles of hearts from wild-type and Mef2c-null mouse embryos by an RNA microarray analysis. Because Mef2c-null embryos die around E9.5 (Lin et al. 1997), we used hearts from wild-type and null embryos at E9.0 prior to overt cardiac demise. Among the genes that were dysregulated in the Mef2c mutants, we found the expression of Stk23 to be significantly decreased in the Mef2c-null hearts. The down-regulation of Stk23 expression in the Mef2c-null hearts was confirmed by RT–PCR (Fig. 1a). Residual expression of Stk23 in the mutants may reflect the presence of other MEF2 factors that partially compensate for MEF2C.

Figure 1.

Identification of Stk23/Srpk3 as a novel SRPK. (a) Microarray analysis was performed using the hearts of E9.0 Mef2c-null and wild-type embryos. Down-regulation of the Stk23/Srpk3 expression in the Mef2c-null hearts was confirmed by RT–PCR. (Gapd) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression as a control. (b) Amino acid structure of mouse Stk23/Srpk3. Srpk3 is a 566-amino-acid protein that contains a bipartite kinase domain (underlined), N terminus, and a hinge region. (c) Schematic representation of mouse SRPK family kinases. Srpk3 shows high sequence similarity to Srpk1 and Srpk2 in the kinase domain, but not in the N terminus and hinge region. The percentages in the boxes are identities of Srpk1 and Srpk2 to Srpk3 at an amino acid level. Srpk3 and Srpk2 have serine- and proline-rich sequences in the N terminus, respectively. Amino acid numbers are also shown. (d) Phosphorylation assays using SR domain proteins. Srpk3 phosphorylated SF2/ASF and the N-terminal region of Lamin B Receptor (LBR) in vitro.

Stk23 was described in an analysis of human chromosomal DNA methylation as a potential protein-kinase-encoding gene (Grunau et al. 2000), but its expression profile and function have not been described. Structural comparison with various protein kinases clearly indicated that Stk23 possesses a bipartite kinase domain with high sequence similarity to the SRPK family kinases, Srpk1 and Srpk2 (Fig. 1b,c; Gui et al. 1994; Bedford et al. 1997; Kuroyanagi et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998). As expected, Stk23 efficiently phosphorylated known SRPK substrates, the splicing factor SF2/ASF, and Lamin B Receptor in in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 1d; Nikolakaki et al. 1997; Koizumi et al. 1999; Yeakley et al. 1999; Takano et al. 2002). Therefore, we propose a functionally descriptive nomenclature, Srpk3, for Stk23.

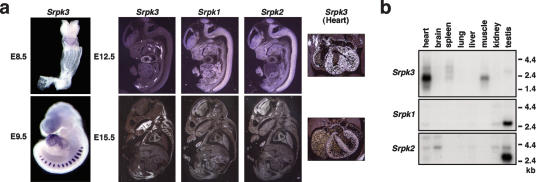

In situ hybridization with mouse embryos showed Srpk3 to be specifically expressed in the developing heart, somites, and skeletal muscles, in contrast to broad expression of Srpk1 and Srpk2 (Fig. 2a). Expression in the heart was first detected in the heart tube, immediately following expression of MEF2C, and expression in the somite myotomes was observed by E9.5. Within the embryonic heart, Srpk3 is expressed throughout the atrial and ventricular chambers (Fig. 2a). Srpk3 is highly expressed in the heart and skeletal muscle in adult mice (Fig. 2b). Muscle-specific expression was also observed in human fetal and adult tissues (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Muscle-specific expression of Srpk3. (a) Expression of the SRPK family in mouse embryos. Whole-mount and section in situ hybridization. Srpk3 is expressed exclusively in the developing heart, somites, and embryonic skeletal muscle. Srpk1 and Srpk2 are widely expressed in embryonic tissues, with enrichment in the neural tube and brain. Enlargements of the heart from each stage are shown to the right. (b) Expression of the SRPK family in adult mice. Srpk3 is specifically expressed in the heart and skeletal muscle, with a faint expression in the spleen. Testis-enriched expression of Srpk1 and Srpk2 is also shown below. With longer exposure, lower levels of Srpk1/-2 expression were observed ubiquitously.

Regulation of the Srpk3 promoter by MEF2

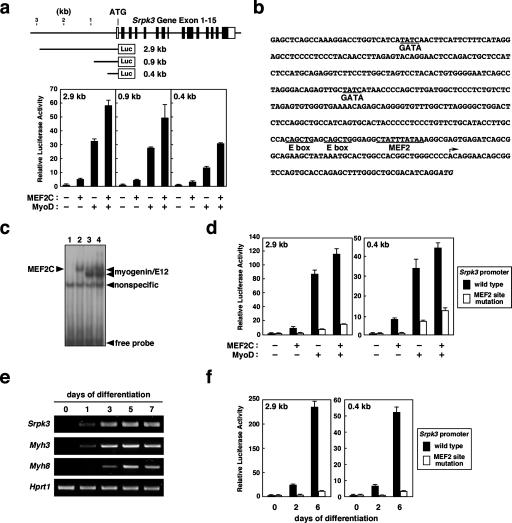

To examine if Srpk3 is transcriptionally regulated by MEF2, we performed reporter analyses in vitro and in vivo. MEF2C and MyoD significantly activated the expression of a luciferase reporter controlled by a 2.9-kb DNA fragment encompassing the 5′ Srpk3 promoter region, and serial deletion analysis revealed that a 0.4-kb fragment was sufficient for the activation by MEF2C and MyoD (Fig. 3a). Indeed, the 0.4-kb fragment contains a MEF2-binding site and two E boxes (Fig. 3b). Although there are also two GATA sites in the 0.4-kb fragment, GATA proteins did not enhance Srpk3 promoter activity in luciferase assays (data not shown). An oligonucleotide probe, containing the MEF2 site and E boxes in the Srpk3 promoter, was bound by MEF2C as well as by myogenin and its ubiquitous bHLH dimerization partner, E12 (Fig. 3c). Mutation of the MEF2 site in the context of the 2.9- or 0.4-kb fragment significantly decreased the response to MEF2C and MyoD in luciferase assays (Fig. 3d), suggesting that MEF2 is an obligate activator of the Srpk3 promoter.

Figure 3.

MEF2-dependent muscle-specific transcription of Srpk3. (a) The structure of the mouse Srpk3 gene with schematics of the luciferase constructs and the results of luciferase assays are shown. Filled and open boxes indicate the exons for protein-coding and noncoding regions, respectively. MEF2C and MyoD strongly activate luciferase reporter expression controlled by the Srpk3 enhancer/promoter in C2C12 myoblasts. The 0.4-kb fragment is sufficient for the response. (b) Sequence of the 0.4-kb minimal muscle enhancer/promoter of Srpk3. The MEF2-binding site, E boxes, and GATA-binding sites are underlined. The putative transcriptional start site estimated by the most 5′-end of Srpk3 cDNA clones is indicated by an arrow. The translational start site (ATG) is italicized. (c) MEF2C and the myogenin/E12 complex bind to the fragments encompassing the MEF2 site and E boxes in the minimal muscle enhancer of Srpk3. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. (Lane 1) Control. (Lane 2) MEF2C. (Lane 3) Myogenin and E12. (Lane 4) MEF2C, myogenin, and E12. (d) Mutation of the MEF2-binding site in the context of the 2.9- or 0.4-kb Srpk3 fragments significantly impairs the response to MEF2C and MyoD in luciferase assays. (e) Srpk3 expression is activated by 1 d after stimulation during myogenic conversion of C2C12 cells. Expression patterns of embryonic and perinatal myosins, Myh3 and Myh8, respectively, are also shown. (Hprt1) Hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 as a control. (f) Activity of the Srpk3 luciferase reporters is markedly stimulated during myogenic conversion of C2C12 cells, while mutation of the MEF2-binding site almost abolishes it.

Transcriptional control of Srpk3 during myogenic differentiation in vitro

We next examined the expression of Srpk3 mRNA during differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts, which are triggered to differentiate and form myotubes upon transfer to medium with low serum (Lu et al. 2000). Srpk3 mRNA was not expressed in C2C12 myoblasts but was markedly induced together with embryonic and perinatal myosin genes, Myh3 and Myh8, during myogenesis (Fig. 3e).

Consistently, expression of a luciferase reporter controlled by the Srpk3 promoter was markedly enhanced during differentiation of C2C12 cells (Fig. 3f). Mutation of the MEF2 site almost abolished the promoter activity, suggesting that Srpk3 expression is activated upon myogenic differentiation directly by MEF2 proteins.

Transcriptional control of Srpk3 in vivo

We further examined the transcriptional regulation of Srpk3 expression in transgenic mice. The 2.9-kb and 0.4-kb Srpk3 regulatory regions fused to the HSP68 basal promoter (Fig. 4a) directed the expression of a LacZ reporter in the embryonic heart and somites (Fig. 4b,c), recapitulating the muscle-specific expression pattern of the endogenous gene. The 0.4-kb fragment was also sufficient to direct muscle-specific expression without the HSP68 minimal promoter (data not shown). Analyses of embryo sections confirmed that LacZ expression was observed throughout cardiac muscle walls, including the outflow tract, and in the somite myotomes (data not shown).

Figure 4.

MEF2-dependent transcriptional control of Srpk3 in mouse embryos. (a) Schematic representation of Srpk3-HSP68-LacZ reporter constructs and results of F0 transgenic mouse analysis. The number of embryos that showed representative expression patterns and total transgenic embryos are shown on the right. Representative results are shown in panels b–e. The 2.9- and 0.4-kb fragments drove LacZ expression in the heart and somites in E11.5 embryos (b,c, respectively). The MEF2 site mutation (d), but not the E-box mutations (e), abolished the LacZ activity both in the heart and somites.

Consistent with the luciferase reporter analyses, the mutation of the MEF2-binding site in the context of the 0.4-kb fragment completely abolished LacZ expression in the heart and somites. Ten out of 16 transgenic embryos harboring the transgene with the mutant MEF2 site showed no LacZ staining (Fig. 4d), and the remaining showed weak ectopic expression that was not specific to the heart and somites. In contrast, mutation of the two E boxes did not result in a significant decrease of LacZ expression in the heart and somites (Fig. 4e). We conclude that Srpk3 is a direct transcriptional target of MEF2 proteins in vivo.

Muscle defects in Srpk3 transgenic mice

SRPKs are known to regulate mRNA splicing and the assembly of nuclear lamina proteins, by phosphorylating SR splicing factors and Lamin B Receptor (Gui et al. 1994; Bedford et al. 1997; Nikolakaki et al. 1997; Kuroyanagi et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998; Koizumi et al. 1999; Yeakley et al. 1999; Takano et al. 2002). RNAi experiments showed that SRPK is essential for germline development in Caenorhabditis elegans (Kuroyanagi et al. 2000), but in vivo functions of the SRPK family have not been examined in mammals.

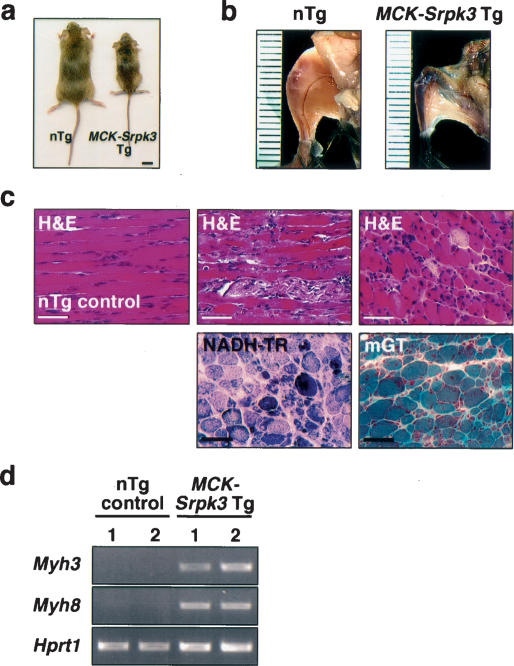

To analyze the effects of excessive SRPK activity in striated muscles, we generated transgenic mice overexpressing Srpk3 in skeletal muscle, using the muscle creatine kinase (MCK) gene promoter and enhancer (Sternberg et al. 1988). Multiple F0 transgenic mice died pre-maturely with severe muscle wasting and growth retardation. Two F0 mice survived to sexual maturity and were fertile, but the F1 transgenic mice derived from these founders died at 2–8 wk of age, which prevented us from establishing transgenic mouse lines. However, those transgenic mice shared muscle defects with myofiber disarray and degeneration (Fig. 5a–c). These mice also showed myocyte regeneration characterized by an increase in centrally placed nuclei (Fig. 5c) and activation of embryonic gene markers (Fig. 5d). Although these characteristics are similar to those of muscular dystrophy, Evans Blue dye injection did not show abnormalities of sarcolemmal integrity (data not shown), and the expression of dystrophin and related sarcolemmal proteins was intact (Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting that excess SRPK activity causes muscle degeneration by a different mechanism.

Figure 5.

Muscle defects in MCK–Srpk3 transgenic mice. (a,b) Muscle creatine kinase (MCK)–Srpk3 transgenic (Tg) mice showed significant growth retardation and muscle defects compared with nontransgenic (nTg) littermates at 1 mo of age. Bar in panel a represents 1 cm. (c) Histological analysis of MCK–Srpk3 Tg mice showed severe muscle degeneration with myofiber disarray, increase in centrally placed nuclei, and fibrosis. Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E), NADH-tetrazolium reductase (NADH-TR), and modified Gomori Trichrome (mGT) staining of gastrocnemius muscle. H&E staining of nTg control is also shown. Bar, 100 μm. (d) Muscle regeneration markers, Myh3 and Myh8, are up-regulated in the skeletal muscle of MCK–Srpk3 Tg mice. Similar results were obtained using F1 mice derived from two F0 founders of MCK–Srpk3 transgenic mice.

Centronuclear myopathy in Srpk3-null mice

To further elucidate the significance of Srpk3 in vivo, we generated Srpk3-null mice (Fig. 6a–c). The mutation we introduced into the gene deleted parts of exons 1 and 5 and all of exons 2, 3, and 4, which encode the N-terminal portion of Kinase Domain 1 (Fig. 6a). Northern analysis showed the complete absence of Srpk3 transcripts in the heart and skeletal muscle of mutant mice (Fig. 6c).

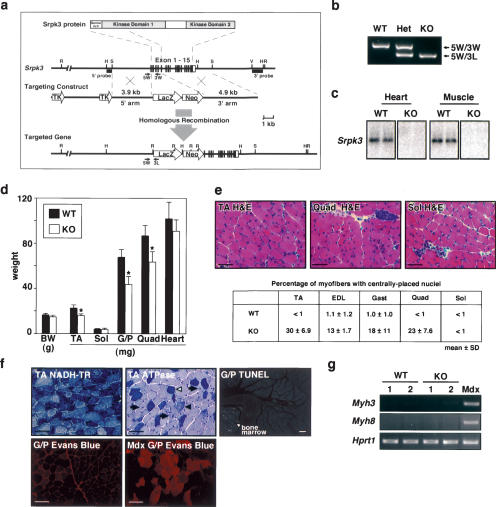

Figure 6.

Centronuclear myopathy of Srpk3-null mice (a) Gene targeting strategy. The mouse Srpk3 gene is shown with the targeting vector and the targeted allele. Parts of the exons 1 and 5, and the entire exons 2, 3, and 4 were replaced with the LacZ–neomycin resistance gene (Neo) cassette. Genotypes were determined by Southern blot analysis and PCR. The positions of the 5′ and 3′ Southern probes and PCR primers (5W, 3W, 3L) are shown. (TK) Thymidine kinase; (R) EcoRI; (H) HindIII; (S) SpeI; (V) EcoRV. (b) A representative result of PCR genotyping. (WT) Wild-type mouse; (Het) female heterozygous mouse; (KO) male hemizygously null mouse. (c) The Srpk3 mRNA expression is not detectable in the heart and skeletal muscle of Srpk3-null mice by Northern blot analysis. (d) The weight of various skeletal muscle groups significantly decreased in Srpk3-null mice. (BW) Body weight. Mean ± SD; n = 6; (*) p < 0.01. (E) H&E staining of various muscle groups of Srpk3-null mice. Bars, 100 μm. Percentages of centrally placed nuclei are also shown (n = 400–600). (f) The NADH-TR, ATPase and TUNEL staining, and the result of Evans Blue injection of Srpk3-null mice. ATPase activity stains type 1 fibers dark blue (open triangle), type 2B fibers blue (filled triangle), and type 2A fibers light blue (arrows). Cells in the bone marrow, but not skeletal myocytes, showed positive signals in TUNEL staining. Evans Blue injection showed no apparent abnormality of sarcolemmal integrity in Srpk3-null mice, in contrast to Mdx dystrophic mice shown as a positive control. Bar, 100 μm. Muscle groups: (EDL) extensor digitorum longus; (G/P) gastrocnemius and plantaris; (Quad) quadriceps; (Sol) soleus; (TA) tibialis anterior. (g) Expression of muscle regeneration markers, Myh3 and Myh8, is not activated in Srpk3-null mice, in contrast to Mdx mice. RT–PCR analysis.

Since the Srpk3 gene is located on the X chromosome, wild-type and hemizygously null male mice were examined in this study. Srpk3-null mice were viable to adulthood, but displayed apparent defects in skeletal muscle growth. The mass of various skeletal muscle groups was significantly smaller than that of wild-type littermates at 1 mo (Fig. 6d) and 3 mo of age (data not shown). Histological analysis revealed a marked increase in centrally placed nuclei and a disorganized intermyofibrillar network, occasionally with ring-fiber-like structure or spheroid bodies (Fig. 6e,f; data not shown).

The pathological characteristics of Srpk3-null muscle were different from those of MCK–Srpk3 transgenic mice. Although an increase in centrally placed nuclei is frequently indicative of muscle regeneration in response to disease or injury (Garry et al. 2000; Carpenter and Karpati 2001; Emery 2002), Srpk3-null mice did not show up-regulation of embryonic/perinatal muscle markers, which is typically seen during muscle regeneration (Fig. 6g). There were no signs of inflammation, neutrophil infiltration, or fibrosis in Srpk3-null mice (Fig. 6e), nor was there an increase in apoptotic cell death detectable by TUNEL staining (Fig. 6f). The serum creatine kinase activity indicative of sarcolemmal leakage also did not significantly increase in Srpk3-null mice (wild type, 409 ± 192; null, 486 ± 291; IU/L, n = 10), and Evans Blue dye injection did not show abnormalities of sarcolemmal integrity (Fig. 6f).

The pathological characteristics of the skeletal muscle in Srpk3-null mice, especially an increase of centronucleated myofibers without apparent myocyte death, are reminiscent of human centronuclear myopathy (Carpenter and Karpati 2001; Jeannet et al. 2004). However, centrally placed nuclei were observed only in type 2 fibers, but not in type 1 fibers, in Srpk3-null mice (Fig. 6f), in contrast to type 1 fiber specific abnormalities associated with human centronuclear myopathy (Laporte et al. 1996; Carpenter and Karpati 2001; Jeannet et al. 2004). These results suggested that Srpk3-null mice displayed a new entity of centronuclear myopathy.

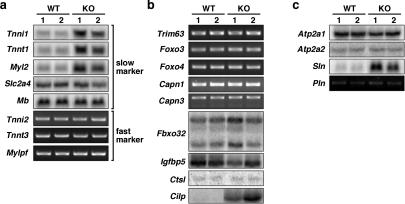

Alteration of muscle gene expression in Srpk3-null mice

To further characterize muscle abnormalities of Srpk3-null mice, we examined the expression of various muscle genes in type 2 fiber-enriched tibialis anterior muscles. A subset of type 1/slow fiber-enriched genes showed increased expression in Srpk3-null mice; however, the lack of activation of two representative slow twitch fiber markers (Serrano et al. 2001; McCullagh et al. 2004), Slc2a4/Glut4 and Myoglobin (Mb), suggests that the altered gene expression patterns are not a simple reflection of fiber type switching (Fig. 7a). Consistently, expression of type 2/fast fiber-enriched genes (Fig. 7a) as well as the proportions of type 1 and 2 fibers were not altered in Srpk3-null mice (wild type: type 1, 14.6%; type 2, 85.4%, n = 700; Srpk3 null: type 1, 17.9%; type 2, 82.1%, n = 800).

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of muscle genes in Srpk3-null mice Expression of various muscle genes in the tibialis anterior muscle of Srpk3-null mice (KO) and wild-type control (WT). Ethidium bromide staining of RT–PCR products or phosphorimages of Northern blot hybridization are shown. (a) Slow- and fast-twitch myofiber markers. (b) Atrophy-related proteins. (c) Molecules related to calcium handling. At least three mice for each genotype were examined, and two representative results are shown. Gene names: (Atp2a1) ATPase, Ca++ transporting, cardiac muscle, fast twitch 1 or Serca1; (Atp2a2) ATPase, Ca++ transporting, cardiac muscle, slow twitch 2 or Serca2; (Capn1/-3) Calpain 1/-3; (Cilp), cartilage intermediate layer protein; (Ctsl) Cathepsin L; (Fbxo32) F-box-only protein 32, MAFbx or Atrogin-1; (Foxo3/-4) Forkhead box o3/o4; (Igfbp5) insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5; (Mb) myoglobin; (Myl2) myosin, light polypeptide 2, regulatory, cardiac, slow; (Mylpf) myosin light chain, phosphorylatable, fast skeletal muscle; (Pln) Phospholamban; (Slc2a4) solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 4 or Glut4; (Sln) sarcolipin; (Tnni1) Troponin I, skeletal, slow 1; (Tnni2) Troponin I, skeletal, fast 2; (Tnnt1) Troponin T1, skeletal, slow; (Tnnt3) Troponin T3, skeletal, fast; (Trim63) tripartite motif-containing 63 or MuRF1.

Although there was a significant decrease of muscle mass in Srpk3-null mice, most atrophy-related genes (McKinnell and Rudnicki 2004) did not show alteration of expression in Srpk3-null mice. However, we observed a significant increase in expression of the cartilage intermediate layer protein (Cilp) gene (Fig. 7b), which encodes a secreted inhibitor of transforming growth factors and insulin-like growth factors (Lorenzo et al. 1998; Johnson et al. 2003; Seki et al. 2005). Given the importance of growth factor signaling in muscle diseases (McKinnell and Rudnicki 2004), up-regulation of Cilp expression may contribute, at least in part, to myopathy and muscle growth defects in Srpk3-null mice.

Calcium homeostasis plays critical roles in the regulation of skeletal muscle growth and contractility, and abnormalities in calcium handling have been implicated in various muscle diseases (MacLennan et al. 2003). Interestingly, mRNA expression of Sarcolipin (Sln) markedly increased in Srpk3-null mice (Fig. 7). Sln shares structural and functional similarity with Phospholamban, and they physically associate with and inhibit sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (Tupling et al. 2002; MacLennan et al. 2003). Forced expression of Sln in skeletal muscle represses sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium uptake and impairs contractile function (Tupling et al. 2002). Despite its important function, the expression patterns of Sln in muscle diseases have not been previously studied. We also observed that Sln expression increased in dystrophic Mdx mice as well as in cardiotoxin muscle injury models (Garry et al. 2000; Carpenter and Karpati 2001; Emery 2002; data not shown). How Sln expression is regulated in those conditions is unknown, but up-regulation of Sln expression may be a common characteristic of muscle diseases.

Discussion

MEF2 is a key regulator of cardiac and skeletal muscle development as well as remodeling of adult muscles in response to physiologic and pathologic signals (Black and Olson 1998; McKinsey et al. 2002). While MEF2 has been shown to regulate a wide range of muscle structural genes, few other target genes that might mediate its actions in muscle have been identified (Kuisk et al. 1996; Anderson et al. 2004; Phan et al. 2005). The results of the present study identify Srpk3 as a novel muscle-specific protein kinase, which is directly regulated by MEF2 and is essential for normal growth and homeostasis of skeletal muscle.

Abnormalities in skeletal muscle resulting from dysregulation of Srpk3

Striated muscles are highly sensitive to the level of Srpk3 expression. Overexpression of Srpk3 in skeletal muscle causes severe myofiber abnormalities, while overexpression in the heart results in dilated cardiomyopathy characterized by chamber dilatation, reduced contractility, and disease marker expression (M. Arnold, M. Nakagawa, H. Hamada, O. Nakagawa, J.A. Richardson, and E.N. Olson, unpubl.). Conversely, targeted deletion of the Srpk3 gene results in a unique form of skeletal myopathy with a marked increase in centrally placed nuclei. The histological characteristics of these mice share similarity with those in human centronuclear myopathy, a congenital myopathy characterized by the presence of numerous centronuclear myofibers (Laporte et al. 1996; Carpenter and Karpati 2001; Jeannet et al. 2004).

Central placement of myonuclei occurs in various pathological conditions and commonly accompanies the regeneration process following myofiber degeneration and death (Garry et al. 2000; Carpenter and Karpati 2001; Emery 2002). In response to muscle injury, quiescent muscle progenitor cells, called satellite cells, are activated and differentiate into new myofibers with centrally placed nuclei as are also seen in newly formed muscle fibers during embryonic development. However, in contrast to muscular dystrophy models, Srpk3-null mice did not show histological signs of myocyte death or reactivation of early developmental markers, which typically accompanies regeneration. Instead, the skeletal muscle of Srpk3-null mice may retain partially immature characteristics, although myofiber differentiation in these mice apparently progresses beyond the stages with embryonic and perinatal myosin expression. The conclusion that centronuclear myopathy in Srpk3 mutant mice reflects a developmental abnormality is also supported by the absence of signs of muscle degeneration and regeneration, such as muscle cell death, myofiber disarray, or neutrophil infiltration, at early ages (data not shown).

The only gene shown to be involved in human centronuclear myopathy is myotubularin 1 (MTM1), which encodes a ubiquitously expressed dual-specificity phosphatase (Laporte et al. 1996, 2003; Buj-Bello et al. 2002). Mutations of MTM1 cause an X-linked form of centronuclear myopathy, characterized by an immature myotube-like appearance of skeletal muscle (Carpenter and Karpati 2001; Laporte et al. 2003). Null mutation of the Mtm1 gene also causes centronuclear myopathy in mice (Buj-Bello et al. 2002). Muscle growth defects in Mtm1-null mice are more severe than those of Srpk3-null mice, and centrally placed nuclei are observed predominantly in type 1 fibers. However, these two models share similar features, such as the proportions of centronuclear myofibers and the lack of inflammation, apoptosis, and sarcolemmal disruption. The Myotubularin substrates that are related to skeletal muscle abnormalities remain unidentified. Perhaps there is cross-talk of signaling pathways downstream of Srpk3 and Myotubularin. The phenotype of Srpk3 null mice also raises the question whether mutations in the SRPK3 gene might be responsible for human myopathies that have not yet been ascribed to a specific gene.

Cellular functions of SRPK in skeletal muscle

The SRPK family of protein kinases is highly conserved among species; Sky1p and Dsk1 in yeast, SPK-1 in C. elegans, SRPK in Drosophila, and Srpk1 and Srpk2 in mice and humans (Gui et al. 1994; Bedford et al. 1997; Kuroyanagi et al. 1998, 2000; Tang et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998; Siebel et al. 1999). SRPKs phosphorylate serine/arginine (SR)-rich domain proteins and modulate their protein–protein interactions and intracellular localization. For example, unphosphorylated SR splicing factors associate with SRPK in the cytoplasm and, once phosphorylated, dissociate from SRPK and are translocated to the nucleus (Koizumi et al. 1999; Yeakley et al. 1999).

In this regard, it is interesting to note that abnormal mRNA splicing has been implicated in a variety of muscle diseases (Maniatis and Tasic 2002), and cardiac-specific deletion of the SR splicing factor genes, Sfrs1 and Sfrs2, causes dilated cardiomyopathy in mice (Ding et al. 2004; Xu et al. 2005). Additionally, splicing defects of the tyrosine phosphatase-like gene, Ptpla, lead to centronuclear myopathy in dogs (Pele et al. 2005). SRPKs also phosphorylate Lamin B Receptor, an integral protein in the inner nuclear membrane or nuclear lamina (Nikolakaki et al. 1997; Ye et al. 1997; Takano et al. 2002). Mutations of the genes encoding the nuclear lamina proteins, Emerin or Lamin A/C, cause Emery-Dreifuss type muscular dystrophy (Wilson 2000). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that defects of mRNA splicing or nuclear lamina assembly contribute to the muscle abnormalities in Srpk3-null and Srpk3 transgenic mice.

It should also be pointed out that proteins without typical SR-rich domains have recently been shown to serve as SRPK substrates (Daub et al. 2002). Although Srpk3 expression is equivalent in type 1- and type 2-enriched muscles (data not shown), there is apparent fiber type specificity of the muscle pathology in Srpk3-null mice, suggesting the involvement of Srpk3 in muscle functions that are important in type 2 fibers, such as glycolytic metabolism. The abnormal muscle gene expression profiles of Srpk3-null mice suggest roles of Srpk3 in growth factor signaling and calcium homeostasis. Identification of muscle-enriched SRPK substrates will provide further insights into functions of Srpk3 in muscle development and disease.

MEF2 as a nexus of kinase signaling pathways

A variety of kinase signaling pathways have been shown to augment MEF2 activity (McKinsey et al. 2002). Signaling by p38 MAP kinase, for example, results in phosphorylation of the transcription activation domain of MEF2 and consequent enhancement of transcriptional activity (Han et al. 1997), while the MAP kinase ERK5 interacts directly with MEF2 and serves as a transcriptional coactivator (Kato et al. 1997; Yang et al. 1998; Kasler et al. 2000). In addition, signaling by calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase and protein kinases C and D induces MEF2 activity by releasing the repressive influence imposed by class II histone deacetylases (McKinsey et al. 2000; Vega et al. 2004). The results of this study, which show that MEF2 is an obligate activator of Srpk3 expression, point to MEF2 as a nexus between upstream and downstream kinase signaling pathways that control muscle development and function.

Materials and methods

Mef2c-null embryos, microarray analysis, and cloning of Srpk3 cDNA

Since Mef2c-null embryos die around E9.5 (Lin et al. 1997), the hearts from the wild-type and Mef2c-null embryos were collected prior to overt cardiac demise at E9.0. Microarray analysis was performed using 1 μg of total RNA as previously described (Belbin et al. 2002). The data were queried for difference of signal intensity between two samples, reproducibility in dye swap arrays, and signal intensity compared with local background. A clone that showed decreased signals in the hybridization with Mef2c-null embryo-derived RNA probes was identical to a part of mouse Stk23/Srpk3 cDNA sequence (NM_019684). Full-length Srpk3 cDNA fragments were isolated by screening of an embryonic heart cDNA library (Stratagene), using partial cDNA fragments obtained from the EST resources as a probe. Full-length cDNA fragments of human SRPK3 were also obtained from the EST resources.

Cell culture

C2C12 myoblasts were maintained in the growth medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, and the plasmid transfection was performed using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells was triggered by the transfer to the differentiation medium containing 2% horse serum (Lu et al. 2000). For the luciferase assays during the course of differentiation, C2C12 cells were transfected with the plasmids in growth medium, and myogenic differentiation was stimulated 2 d after the transfection.

Srpk3 transgenic mice

Transgenic mice overexpressing Flag-tagged Srpk3 were generated using the MCK promoter/enhancer (Sternberg et al. 1988). Genotyping was performed by Southern blot analysis, and the skeletal muscle-specific expression of Flag-Srpk3 was confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Srpk3-null mice

A BAC clone containing the Srpk3 gene was obtained by screening of a 129s6/SvEvTAC mouse genomic BAC library (BACPAC Resources). The targeting vector was linearized and electroporated into mouse embryonic stem cells of 129Sv origin. Correctly targeted embryonic stem cell clones, as identified by Southern blotting using both 5′ and 3′ probes, were injected into blastocysts isolated from C57BL/J mice. Chimeras obtained from these blastocyst injections were bred to obtain heterozygous mice that carry the targeted Srpk3 locus in their germline. Genotyping was performed by Southern blot analysis and PCR (primers: 5W, 5′-AGGTCTTCCTTGGCTAGTCCTACACTGTGG-3′; 3W, 5′-TAGTCCTTAGGGTCTTCCTGTTCCTCAT C-3′; and 3L, 5′-CCATGGTGGATCCTGAGACTGGGGAATT C-3′). Srpk3-null mice in the pure 129s6/SvEvTAC background and the mixed 129s6/SvEvTAC-C57BL6/J background showed identical skeletal muscle pathology.

In situ hybridization

Whole-mount and radioactive section in situ hybridization was performed as described (Nakagawa et al. 1999), using Srpk1/-2/-3 RNA probes. For each gene, identical results were obtained using two probes that were prepared using different cDNA fragments.

Northern blot analysis

Northern blot analysis of the SRPK family genes was performed on mouse and human poly(A)+ RNA blots (Clontech), as described (Nakagawa et al. 1999). Northern blot analysis of muscle genes was performed using total RNA of the tibialis anterior muscle of Srpk3-null and wild-type mice. cDNA fragments for probe preparation were prepared by RT–PCR or were obtained from the EST resources. Detailed information of the cDNA probes is available upon request.

RT–PCR

RT–PCR was performed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and Advantage2 DNA polymerase (Clontech). Primer sequences are available upon request.

Luciferase and LacZ reporter analyses

Three different Srpk3 genomic DNA fragments, which had the identical 3′-ends at the translational start site, were ligated into a luciferase reporter plasmid, pGL3 basic (Promega). The genomic DNA fragments were also ligated into a promoter-less LacZ reporter plasmid or a LacZ reporter plasmid containing the HSP68 minimal promoter sequence (Wang et al. 2001). Mutations were introduced by PCR into a MEF2-binding site (wild-type, 5′-GGCTATTTATAAAG-3′; mutant, 5′-GGCTAGGGCTAAAG-3′) and E boxes (wild-type, 5′-CAGCTG-3′; mutant, 5′-ACGCGT-3′) in the Srpk3 regulatory region of the reporter plasmids. Luciferase assays were performed in C2C12 cells, and LacZ reporter assays of F0 transgenic mouse embryos were performed as previously described (Nakagawa et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2001).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The cell lysates containing MEF2C, myogenin, and/or E12 were prepared from COS1 cells transfected with combinations of expression plasmids. In vitro binding analysis was performed as previously described (Wang et al. 2001), using oligonucleotide fragments that contained a MEF2-binding site and E boxes (underlined) in the Srpk3 promoter (5′-CTTGCCCACAGCTGAGCAGCTGGGAGGCTATTTATAAAGGCGAG-3′). The oligonucleotide fragments with a mutated MEF2-binding site (5′-GGCTAGGGCTAAAG-3′) and those with mutated E boxes (5′-ACGCGT-3′) did not show binding by MEF2C and the myogenin/E12 complex, respectively (data not shown).

In vitro phosphorylation assays

Myc-tagged proteins of full-length SF2/ASF (Koizumi et al. 1999) and the N terminus of Lamin B Receptor (Ye et al. 1997) were prepared by in vitro transcription and translation using TNT reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). Myc-Srpk3 and the control sample prepared using the empty plasmid vector were also prepared by the TNT reaction. Proteins were immunoprecipitated using rabbit polyclonal anti-Myc antibody (Santa Cruz), and in vitro kinase reaction was performed with [γ-32P]ATP at 30°C.

Histological analysis of skeletal muscle

Histological staining of skeletal muscles, myofiber typing by the ATPase staining, TUNEL staining, and the Evans Blue dye injection were performed as previously described (Woods and Ellis 1996; Wu et al. 2000; Lu et al. 2002; Kanagawa et al. 2004).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Hagiwara and H. Worman for plasmids; J. Hill, K. Kamm, M. Bennett, L. Leinwand, Y.K. Hayashi, K. Murayama, D. Garry, and R. Bassel-Duby for discussion; and J. McAnally, C. Nolan, J. Bartos, and J. Fields for technical assistance. O.N. was supported by a grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association. E.N.O. was supported by grants from the NIH, the Donald W. Reynolds Center for Clinical Cardiovascular Research, the Robert A. Welch Foundation, and the Muscular Dystrophy Association. G.C. and T.M.M. were supported by an NIH grant (NIH HL083488). M.A. was supported by the Medical Scientist Training Program at University of Texas Southwestern and NIH T-32-GM08014.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1338705.

Corresponding authors.

References

- Anderson J.P., Dodou, E., Heidt, A.B., De Val, S.J., Jaehnig, E.J., Greene, S.B., Olson, E.N., and Black, B.L. 2004. HRC is a direct transcriptional target of MEF2 during cardiac, skeletal, and arterial smooth muscle development in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 3757-3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey P., Holowacz, T., and Lassar, A.B. 2001. The origin of skeletal muscle stem cells in the embryo and the adult. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13: 679-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford M.T, Chan, D.C., and Leder, P. 1997. FBP WW domains and the Abl SH3 domain bind to a specific class of prolinerich ligands. EMBO J. 16: 2376-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbin T., Singh, B., Barber, I., Socci, N., Wenig, B., Smith, R., Prystowsky, M., and Childs, G. 2002. Molecular classification of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma using cDNA microarrays. Cancer Res. 62: 1184-1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black B.L. and Olson, E.N. 1998. Transcriptional control of muscle development by myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14: 167-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais A., Tsikitis, M., Acosta-Alvear, D., Sharan, R., Kluger, Y., and Dynlacht, B.D. 2005. An initial blueprint for myogenic differentiation. Genes & Dev. 19: 553-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bour B.A., O'Brien, M.A., Lockwood, W.L., Goldstein, E.S., Bodmer, R., Taghert, P.H., Abmayr, S.M., and Nguyen, H.T. 1995. Drosophila MEF2, a transcription factor that is essential for myogenesis. Genes & Dev. 9: 730-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M., Bajard, L., Chang, T., Daubas, P., Hadchouel, J., Meilhac, S., Montarras, D., Rocancourt, D., and Relaix, F. 2003. The formation of skeletal muscle: From somite to limb. J. Anat. 202: 59-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buj-Bello A., Laugel, V., Messaddeq, N., Zahreddine, H., Laporte, J., Pellissier, J.F., and Mandel, J.L. 2002. The lipid phosphatase myotubularin is essential for skeletal muscle maintenance but not for myogenesis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 15060-15065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S. and Karpati, G., 2001. Pathology of skeletal muscle. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Cheng T.C., Wallace, M.C., Merlie, J.P., and Olson, E.N. 1993. Separable regulatory elements governing myogenin transcription in mouse embryogenesis. Science 261: 215-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserjesi P. and Olson, E.N. 1991. Myogenin induces the myocyte-specific enhancer binding factor MEF-2 independently of other muscle-specific gene products. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11: 4854-4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub H., Blencke, S., Habenberger, P., Kurtenbach, A., Dennenmoser, J., Wissing, J., Ullrich, A., and Cotton, M. 2002. Identification of SRPK1 and SRPK2 as the major cellular protein kinases phosphorylating hepatitis B virus core protein. J. Virol. 76: 8124-8137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J.H., Xu, X., Yang, D., Chu, P.H., Dalton, N.D., Ye, Z., Yeakley, J.M., Cheng, H., Xiao, R.P., Ross, J., et al. 2004. Dilated cardiomyopathy caused by tissue-specific ablation of SC35 in the heart. EMBO J. 23: 885-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodou E., Xu, S.M., and Black, B.L. 2003. Mef2c is activated directly by myogenic basic helix–loop–helix proteins during skeletal muscle development in vivo. Mech. Dev. 120: 1021-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson D.G., Cheng, T.-C., Cserjesi, P., Chakraborty, T., and Olson, E.N. 1992. Analysis of the myogenin promoter reveals an indirect pathway for positive autoregulation mediated by the muscle-specific enhancer factor MEF-2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 3665-3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery A.E. 2002. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet 359: 687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry D.J., Meeson, A., Elterman, J., Zhao, Y., Yang, P., Bassel-Duby, R., and Williams, R.S. 2000. Myogenic stem cell function is impaired in mice lacking the forkhead/winged helix protein MNF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 5416-5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau C., Hindermann, W., and Rosenthal, A. 2000. Largescale methylation analysis of human genomic DNA reveals tissue-specific differences between the methylation profiles of genes and pseudogenes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9: 2651-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui J.F., Lane, W.S., and Fu, X.D. 1994. A serine kinase regulates intracellular localization of splicing factors in the cell cycle. Nature 369: 678-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Jiang, Y., Li, Z., Kravchenko, V.V., and Ulevitch, R.J. 1997. Activation of the transcription factor MEF2C by the MAP kinase p38 in inflammation. Nature 386: 296-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannet P.Y., Bassez, G., Eymard, B., Laforet, P., Urtizberea, J.A., Rouche, A., Guicheney, P., Fardeau, M., and Romero, N.B. 2004. Clinical and histologic findings in autosomal centronuclear myopathy. Neurology 62: 1484-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Farley, D., Hu, S.I., and Terkeltaub, R. 2003. One of two chondrocyte-expressed isoforms of cartilage intermediate-layer protein functions as an insulin-like growth factor 1 antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 48: 1302-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagawa M., Saito, F., Kunz, S., Yoshida-Moriguchi, T., Barresi, R., Kobayashi, Y.M., Muschler, J., Dumanski, J.P., Michele, D.E., Oldstone, M.B., et al. 2004. Molecular recognition by LARGE is essential for expression of functional dystroglycan. Cell 117: 953-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasler H.G., Victoria, J., Duramad, O., and Winoto, A. 2000. ERK5 is a novel type of mitogen-activated protein kinase containing a transcriptional activation domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 8382-8389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y., Kravchenko, V.V., Tapping, R.I., Han, J., Ulevitch, R.J., and Lee, J.D. 1997. BMK1/ERK5 regulates serum-induced early gene expression through transcription factor MEF2C. EMBO J. 16: 7054-7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi J., Okamoto, Y., Onogi, H., Mayeda, A., Krainer, A.R., and Hagiwara, M. 1999. The subcellular localization of SF2/ASF is regulated by direct interaction with SR protein kinases (SRPKs). J. Biol. Chem. 274: 11125-11131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuisk I.R., Li, H., Tran, D., and Capetanaki, Y. 1996. A single MEF2 site governs desmin transcription in both heart and skeletal muscle during mouse embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 174: 1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroyanagi N., Onogi, H., Wakabayashi, T., and Hagiwara, M. 1998. Novel SR-protein-specific kinase, SRPK2, disassembles nuclear speckles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 242: 357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroyanagi H., Kimura, T., Wada, K., Hisamoto, N., Matsumoto, K., and Hagiwara, M. 2000. SPK-1, a C. elegans SR protein kinase homologue, is essential for embryogenesis and required for germline development. Mech. Dev. 99: 51-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte J., Hu, L.J., Kretz, C., Mandel, J.L., Kioschis, P., Coy, J.F., Klauck, S.M., Poustka, A., and Dahl, N. 1996. A gene mutated in X-linked myotubular myopathy defines a new putative tyrosine phosphatase family conserved in yeast. Nat. Genet. 13: 175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte J., Bedez, F., Bolino, A., and Mandel, J.L. 2003. Myotubularins, a large disease-associated family of cooperating catalytically active and inactive phosphoinositides phosphatases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 Spec No 2: R285-R292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassar A.B., Davis, R.L., Wright, W.E., Kadesch, T., Murre, C., Voronova, A., Baltimore, D., and Weintraub, H. 1991. Functional activity of myogenic HLH proteins requires hetero-oligomerization with E12/E47-like proteins in vivo. Cell 66: 305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly B., Zhao, B., Ranganayakulu, G., Paterson, B.M., Schulz, R.A., and Olson, E.N. 1995. Requirement of MADS domain transcription factor D-MEF2 for muscle formation in Drosophila. Science 267: 688-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Schwarz, J., Bucana, C., and Olson, E.N. 1997. Control of mouse cardiac morphogenesis and myogenesis by transcription factor MEF2C. Science 276: 1404-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo P., Bayliss, M.T., and Heinegard, D. 1998. A novel cartilage protein (CILP) present in the mid-zone of human articular cartilage increases with age. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 23463-23468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., McKinsey, T.A., Zhang, C.L., and Olson, E.N. 2000. Regulation of skeletal myogenesis by association of the MEF2 transcription factor with class II histone deacetylases. Mol. Cell 6: 233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.R., Bassel-Duby, R., Hawkins, A., Chang, P., Valdez, R., Wu, H., Gan, L., Shelton, J.M., Richardson, J.A., and Olson, E.N. 2002. Control of facial muscle development by MyoR and capsulin. Science 298: 2378-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan D.H., Asahi, M., and Tupling, A.R. 2003. The regulation of SERCA-type pumps by phospholamban and sarcolipin. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 986: 472-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T. and Tasic, B. 2002. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing and proteome expansion in metazoans. Nature 418: 236-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh K.J., Calabria, E., Pallafacchina, G., Ciciliot, S., Serrano, A.L., Argentini, C., Kalhovde, J.M., Lomo, T., and Schiaffino, S. 2004. NFAT is a nerve activity sensor in skeletal muscle and controls activity-dependent myosin switching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 10590-10595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnell I.W. and Rudnicki, M.A. 2004. Molecular mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Cell 119: 907-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey T.A., Zhang, C.L., Lu, J., and Olson, E.N. 2000. Signal-dependent nuclear export of a histone deacetylase regulates muscle differentiation. Nature 408: 106-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey T.A., Zhang, C.L., and Olson, E.N. 2002. Signaling chromatin to make muscle. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14: 763-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa O., Nakagawa, M., Richardson, J.A., Olson, E.N., and Srivastava, D. 1999. HRT1, HRT2, HRT3: A new subclass of bHLH transcription factors marking specific cardiac, somitic and pharyngeal arch segments. Dev. Biol. 216: 72-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa O., McFadden, D.G., Nakagawa, M., Yanagisawa, H., Hu, T., Srivastava, D., and Olson, E.N. 2000. Members of the HRT family of bHLH proteins act as transcriptional repressors downstream of Notch signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 13655-13660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolakaki E., Meier, J., Simos, G., Georgatos, S.D., and Giannakouros, T. 1997. Mitotic phosphorylation of the Lamin B Receptor by a serine/arginine kinase and p34(cdc2). J. Biol. Chem. 272: 6208-6213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M.H., Seale, P., and Rudnicki, M.A. 2003. Looking back to the embryo: Defining transcriptional networks in adult myogenesis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4: 497-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pele M., Tiret, L., Kessler, J.L., Blot, S., and Panthier, J.J. 2005. A SINE exonic insertion in the PTPLA gene leads to multiple splicing defects and segregates with the autosomal recessive centronuclear myopathy in dog. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14: 1417-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan D., Rasmussen, T.L., Nakagawa, O., McAnally, J., Gottlieb, P.D., Tucker, P.W., Richardson, J.A., Bassel-Duby, R., and Olson, E.N. 2005. Bop, a regulator of right ventricular heart development, is a direct transcriptional target of MEF2C in the anterior heart field. Development 132: 2669-2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pownall M.E., Gustafsson, M.K., and Emerson Jr., C.P. 2002. Myogenic regulatory factors and the specification of muscle progenitors in vertebrate embryos. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 18: 747-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S., Kawaguchi, Y., Chiba, K., Mikami, Y., Kizawa, H., Oya, T., Mio, F., Mori, M., Miyamoto, Y., Masuda, I., et al. 2005. A functional SNP in CILP, encoding cartilage intermediate layer protein, is associated with susceptibility to lumbar disc disease. Nat. Genet. 37: 607-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano A.L., Murgia, M., Pallafacchina, G., Calabria, E., Coniglio, P., Lomo, T., and Schiaffino, S. 2001. Calcineurin controls nerve activity-dependent specification of slow skeletal muscle fibers but not muscle growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 13108-13113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebel C.W., Feng, L., Guthrie, C., and Fu, X.D. 1999. Conservation in budding yeast of a kinase specific for SR splicing factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 5440-5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg E.A., Spizz, G., Perry, W.M., Vizard, D., Weil, T., and Olson, E.N. 1988. Identification of upstream and intragenic regulatory elements that confer cell-type-restricted and differentiation-specific expression on the muscle creatine kinase gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8: 2896-2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M., Takeuchi, M., Ito, H., Furukawa, K., Sugimoto, K., Omata, S., and Horigome, T. 2002. The binding of lamin B receptor to chromatin is regulated by phosphorylation in the RS region. Eur. J. Biochem. 269: 943-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Yanagida, M., and Lin, R.J. 1998. Fission yeast mitotic regulator Dsk1 is an SR protein-specific kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 5963-5969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teboul L., Hadchouel, J., Daubas, P., Summerbell, D., Buckingham, M., and Rigby, P.W. 2002. The early epaxial enhancer is essential for the initial expression of the skeletal muscle determination gene Myf5 but not for subsequent, multiple phases of somitic myogenesis. Development 129: 4571-4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupling A.R., Asahi, M., and MacLennan, D.H. 2002. Sarcolipin overexpression in rat slow twitch muscle inhibits sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake and impairs contractile function. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 44740-44746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega R.B., Harrison, B.C., Meadows, E., Roberts, C.R., Papst, P.J., Olson, E.N., and McKinsey, T.A. 2004. Protein kinases C and D mediate agonist-dependent cardiac hypertrophy through nuclear export of histone deacetylase 5. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 8374-8385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.Y., Lin, W., Dyck, J.A., Yeakley, J.M., Songyang, Z., Cantley, L.C., and Fu, X.D. 1998. SRPK2: A differentially expressed SR protein-specific kinase involved in mediating the interaction and localization of pre-mRNA splicing factors in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 140: 737-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.Z., Valdez, M.R., McAnally, J., Richardson, J., and Olson, E.N. 2001. The Mef2c gene is a direct transcriptional target of myogenic bHLH and MEF2 proteins during skeletal muscle development. Development 128: 4623-4633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K.L. 2000. The nuclear envelope, muscular dystrophy and gene expression. Trends Cell Biol. 10: 125-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods A.E. and Ellis, R.C. 1996. Laboratory histopathology, a complete reference. Churchill-Livingston Press, Oxford.

- Wu H., Naya, F.J., McKinsey, T.A., Mercer, B., Shelton, J.M., Chin, E.R., Simard, A.R., Michel, R.N., Bassel-Duby, R., Olson, E.N., et al. 2000. MEF2 responds to multiple calcium-regulated signals in the control of skeletal muscle fiber type. EMBO J. 19: 1963-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Yang, D., Ding, J.H., Wang, W., Chu, P.H., Dalton, N.D., Wang, H.Y., Bermingham Jr., J.R., Ye, Z., Liu, F., et al. 2005. ASF/SF2-regulated CaMKIIδ alternative splicing temporally reprograms excitation–contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Cell 120: 59-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.C., Ornatsky, O.I., McDermott, J.C., Cruz, T.F., and Prody, C.A. 1998. Interaction of myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) with a mitogen-activated protein kinase, ERK5/BMK1. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 4771-4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q., Callebaut, I., Pezhman, A., Courvalin, J.C., and Worman, H.J. 1997. Domain-specific interactions of human HP1-type chromodomain proteins and inner nuclear membrane protein LBR. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 14983-14989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeakley J.M., Tronchere, H., Olesen, J., Dyck, J.A., Wang, H.Y., and Fu, X.D. 1999. Phosphorylation regulates in vivo interaction and molecular targeting of serine/arginine-rich pre-mRNA splicing factors. J. Cell Biol. 145: 447-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee S.P. and Rigby, P.W. 1993. The regulation of myogenin gene expression during the embryonic development of the mouse. Genes & Dev. 7: 1277-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]