Abstract

Data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) has become increasingly pivotal in quantitative proteomics. In this study, we present DIA-BERT, a software tool that harnesses a transformer-based pre-trained artificial intelligence (AI) model for analyzing DIA proteomics data. The identification model was trained using over 276 million high-quality peptide precursors extracted from existing DIA-MS files, while the quantification model was trained on 34 million peptide precursors from synthetic DIA-MS files. When compared to DIA-NN, DIA-BERT demonstrated a 51% increase in protein identifications and 22% more peptide precursors on average across five human cancer sample sets (cervical cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, myosarcoma, gallbladder cancer, and gastric carcinoma), achieving high quantitative accuracy. This study underscores the potential of leveraging pre-trained models and synthetic datasets to enhance the analysis of DIA proteomics.

Subject terms: Proteome informatics, Protein sequence analyses, Proteomics

Data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) has emerged as a key technology in quantitative proteomics. Here, the authors introduce DIA-BERT, a transformer model pre-trained on existing DIA datasets to enhance peptide identification and quantification.

Introduction

Analyzing data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) based proteomics data remains a formidable challenge1–3. Pioneering DIA identification tools, such as OpenSWATH4 and Spectronaut5, employ a targeted data analysis strategy similar to that used in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), like mProphet6 and Skyline7. In this strategy, peak groups, instead of mass spectra, are extracted for scoring, significantly reducing data complexity, and largely preserving the major ion trace and retention information of peptide precursors and top N fragment ions. Recent DIA identification tools, such as DIA-NN8, MaxDIA9, Specter10 and DreamDIA11, typically employ a multi-stage approach. They initially score peak groups with relatively simple rules or models and then refine the selection through an iterative procedure. This process leverages an expanding array of features, progressively enhancing the discriminative power of the scoring model to improve selection accuracy. Nevertheless, current DIA identification tools face limitations. They train independent scoring models for each mass spectrometry file, and due to the limited training sample size in a single file, these tools typically rely on conventional machine learning models with limited capacity to avoid overfitting. Training the scoring model separately for each MS file prevents it from leveraging information from other files. As a result, they often fail to adequately capture intricate peptide-peak-group matching patterns. Their reliance on manually engineered features such correlations between different metrics in current methodologies further limits the overall analytical performance. Additionally, training the representation model and the scoring model independently, or relying on handcrafted features, prevents an information feedback loop between these two stages, thus missing opportunities for joint learning.

Emerging approaches, such as AlphaTri12and Alpha-XIC13, attempt to use more complex deep learning models specifically designed for MS spectra to capture intricate peptide-peak-group matching patterns. However, their scoring model is still trained independently for each individual mass spectrometry file, which limits the complexity of the models. It uses the relatively simple two-layer Long Short-Term Memory14 models with limited scoring performance. DreamDIA11 employs a more sophisticated approach. It first trains a deep representation model using training samples extracted from multiple mass spectrometry files. The learned representation is then fed into an XGBoost15-based scoring model, along with some manual features, to filter peak groups. While the representation model is trained on one million representative spectral matrices, the shallow XGBoost scoring model is still trained separately for each mass spectrometry file and the representation model and the scoring model are still trained independently, limiting its power.

BERT16, an acronym for Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, stands at the forefront of natural language processing breakthroughs. Here, we introduce DIA-BERT (Fig. 1a, Methods), a transformer-based pre-trained AI model tailored for analyzing DIA-MS proteomics data. We present a DIA identification algorithm leveraging an encoder-only transformer model. The models in the initial (pre-filtering model) and subsequent (pre-trained scoring model) stages undergo training on extensive datasets comprising 276 million and 318 million training instances sourced from 952 DIA proteomics files from various human specimens, respectively.

Fig. 1. DIA-BERT workflow and its performance on different human cancer datasets.

a The workflow of DIA-BERT. b Comparison of peptide and protein identification between DIA-BERT and DIA-NN (library-based mode) in human proteome datasets18. A two-sided paired Student’s t-test was performed without adjustment. The p values for peptide precursor and protein, respectively, are: 0.0711 and 0.0060 (pancreatic adenocarcinoma), 0.1655 and 0.0011 (cervical cancer), 0.0025 and 0.0009 (myosarcoma), 0.0091 and 0.0064 (gallbladder cancer), and 0.0263 and 0.0108 (gastric carcinoma). c The overlap of identified human tissue peptide precursors or proteins using DIA-BERT and DIA-NN (library-based mode). d Comparison of peptide and protein identifications between DIA-BERT and DIA-NN (library-free mode) in human proteome datasets. A two-sided paired Student’s t-test was performed without adjustment. The p values for peptide precursor and protein, respectively, are: 0.0275 and 0.0046 (pancreatic adenocarcinoma), 0.0018 and 0.0005 (cervical cancer), 0.0020 and 0.0009 (myosarcoma), 0.0002 and 0.0022 (gallbladder cancer), and 0.0028 and 0.0056 (gastric carcinoma). Data (b, d) are presented as mean values ±SD. The statistics (b, d) are derived from three biological replicates per cancer type. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. For (b–d), brownish-orange color represents DIA-BERT; Light green color represents DIA-NN.

Our model undergoes end-to-end training, eliminating the necessity for a separate handcrafted feature extraction or representation learning step required by solutions such as DreamDIA11 and other conventional machine learning-based methods. For each precursor, the model extracts fragment ion peak group information and combines it with library information like fragment intensities, feeding this raw data directly into the model. The model is then tasked with learning how to assess the consistency of peaks within a peak group and the correlation between peak intensity and library intensity, harnessing the robust data modeling capabilities inherent in convolutional and transformer networks. This unified training process enables our model to concurrently optimize representation learning and scoring model learning, leading to enhanced identification sensitivity.

The pre-trained scoring model is then fine-tuned on each mass spectrometry file to be tested. Pre-training reduces overfitting that may result from training on individual files with limited data. The fine-tuning procedure further enhances the model’s adaptability by fine-tuning its parameters to align with file-specific characteristics, such as variations in fragment ion intensity patterns or retention time distribution, thereby improving the accuracy and sensitivity of identifications. Similarly, the quantification model also benefits from the fine-tuning procedure, enabling it to achieve more precise and accurate quantification results.

In this work, DIA-BERT17 significantly improves peptide identification by effectively capturing complex peptide-peak-group matching patterns through its use of transformers, end-to-end learning from raw data, and large-scale pre-training on diverse proteomics datasets (see more details in Supplementary Discussion).

Results

To evaluate the performance of DIA-BERT, we used DIA proteome datasets consisting of various human tumor tissues18. These datasets include DIA maps of five different cancers (cervical cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, myosarcoma, gallbladder cancer, and gastric carcinoma), each with three samples, sourced from the iProx database (IPX0001981000). The DIA pan-human library (DPHL) v.2 was employed as the spectral library19. Given that DIA-NN is currently one of the best-performing DIA proteome software tools, as shown in multiple evaluation studies20,21, and it is free to the academic community, we compared the performance of our DIA-BERT tool with DIA-NN.

As shown in Fig. 1b and Zenodo file 1, DIA-BERT outperformed DIA-NN (version 1.9.2) in all DIA files, with conservative FDR values below 0.01, using a two-species spectral library method (see Methods), as demonstrated in previous studies8,21. On average, DIA-BERT identified 22% more peptide precursors and 51% more proteins than DIA-NN. Furthermore, DIA-BERT recalled 80% of peptide precursors and 98% of proteins identified by DIA-NN (Fig. 1c, Zenodo file 2).

We also assessed the consistency of identifications across the five human cancer sample sets, requiring detection in at least two-thirds of the samples. The results showed that DIA-BERT consistently identified 62% of precursors and 86% of proteins on average, compared to DIA-NN (library-based mode) with 62% and 78%, respectively (Zenodo file 2).

In addition, we compared DIA-BERT’s performance with DIA-NN in library-free mode. Using DIA files from the five human tumors, DIA-BERT identified 73% more proteins and 56% more peptide precursors on average compared to DIA-NN (Fig. 1d, Zenodo file 1). Notably, the average conservative FDR for DIA-BERT (precursor: 0.00356; protein: 0.00646) was significantly lower than that of DIA-NN (precursor: 0.01107; protein: 0.01289), highlighting the robustness and reliability of DIA-BERT’s identification capabilities.

We conducted a deeper analysis of the unique peptide precursors and proteins identified by DIA-BERT compared to DIA-NN in library-based mode. Specifically, we examined one-hit-wonder proteins, which are proteins identified by only a single peptide precursor. On average, DIA-BERT identified 150% more human one-hit-wonder proteins than DIA-NN when using the two-species spectral library method (Supplementary Fig. 1a). After filtering out these one-hit-wonder proteins, DIA-BERT still identified 29% more proteins than DIA-NN (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The number of both one-hit-wonder and multi-peptide proteins identified by DIA-BERT was significantly higher than that of DIA-NN, as confirmed by a two-sided paired Student’s t-test (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

We hypothesized that DIA-BERT has an improved ability to detect low-abundance proteins. To test this, we compared the abundance levels of unique and common peptide precursors/proteins identified by DIA-BERT and DIA-NN. Our analysis showed that the abundance of unique precursors and proteins was significantly lower than that of common precursors and proteins (two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test, p < 0.05), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1b. This pattern was also observed in DIA-NN (Supplementary Fig. 1c), indicating that DIA-BERT enhances the identification of low-abundance peptide precursors and proteins while maintaining similar performance for high-abundance ones.

Since the DIA-BERT is a pretraining model, we hypothesized that the model’s performance is dependent on the volume of training data. To test this, we trained BERT models using varying data volumes by randomly selecting 1, 35, 106, and 317 files from the 952 available for DIA-BERT. These models (Model_1file, Model_35files, Model_106files, Model_317files) were evaluated on the five human cancer sample sets, using a two-species spectral library method8,21. The results showed that all conservative FDRs were below 0.01, and the number of human precursors and proteins identified by the models increased with the log₁₀ (training dataset size), following an approximately linear correlation (adjusted R-squared > 0.9) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although this correlation was observed specifically within the tested range of data volumes (1 to 952 files) and may not extend beyond this range, the result indicates promising potential for further improvement with larger training datasets.

We further evaluated the performance of DIA-BERT using a three-species dataset20,22 (human, yeast, and C. elegans) sourced from the PRIDE database (PXD016647). Compared to DIA-NN, DIA-BERT achieved a 6% increase in protein identification and a 4% improvement in peptide precursor identification (Supplementary Fig. 3a, Zenodo file 1). The number of peptide precursors and proteins identified by DIA-BERT was significantly higher than that of DIA-NN, as confirmed by a two-sided paired Student’s t-test (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 3a). DIA-BERT re-called over 84% of peptide precursors and 93% of proteins initially identified by DIA-NN (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Interestingly, peptide precursors and proteins exclusively identified by DIA-BERT were found at significantly lower abundance compared to those commonly identified by both DIA-BERT and DIA-NN (two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test, p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 3c). A similar trend was observed for DIA-NN (Supplementary Fig. 3d), reinforcing that DIA-BERT enhances the identification of low-abundance peptide precursors and proteins in library-based mode. This capability extends beyond human proteomes to the proteomes of multiple species. Compared to human tumor tissue datasets (DPHL v.2 library size: 601,982 precursors), the identification improvement in the three-species dataset was less pronounced. This may be attributed to the relatively small size of the spectral library (262,227 precursors), which may not have reached saturation. Notably, DIA-BERT has already identified 50% of the human precursors, 63% of the yeast precursors, and 48% of the C. elegans precursors contained in the library. We also assessed DIA-BERT’s performance against DIA-NN in library-free mode, DIA-BERT identified 28% more proteins and 40% more peptide precursors on average across the three-species dataset (Zenodo file 1).

To ensure precise quantification of peptide precursors and proteins, we developed a novel peak area estimation algorithm based on transformer models (see Methods). Current DIA data analysis methods typically rely on simplistic heuristic rules to compute peak areas8,9, followed by basic adjustments based on metrics such as correlation coefficients between peaks within the same group. However, due to substantial noise interference in mass spectrometry signals and complex mutual interference among multiple peak groups, these methods often produce suboptimal results.

While downstream correction techniques, such as MaxLFQ23 and DirectLFQ24, can improve cross-run analysis, initial estimation errors remain difficult to fully compensate for, ultimately limiting quantification accuracy. Our transformer-based algorithm addresses these challenges by leveraging deep learning-driven signal processing, enhancing the reliability of peak area estimation in DIA-MS data analysis.

We utilized Synthedia25, a software package designed for simulating DIA data, to generate training DIA datasets annotated with TRUE peak area values. This synthetic data was then used to train a transformer-based peak area estimation model, enhancing the accuracy of area estimation.

Our peak area estimation model follows a structure similar to our peak group scoring model, with a key distinction: it employs a regression loss function to predict peak areas. By processing the entire peak group’s information, the model leverages data from all peaks within a group to mitigate noise interference, improving robustness in real experimental conditions.

To ensure that our model can handle the complexity of experimental DIA-MS data, we modified Synthedia to account for seven critical factors commonly encountered in real mass spectrometry experiments: (1) high interference among different simulated peptides; (2) retention time shifts due to instrument instability and batch effects; (3) peptide precursor permeation resulting from incomplete peptide fragmentation; (4) unbalanced density between MS1 and MS2 spectra; (5) variations in fragment ion intensity across different samples; (6) differences in chromatographic gradients among samples; (7) the presence of heavy and light fragments. These seven main sources of variations are derived from extensive manual inspection of real DIA-MS files.

We employed a diverse set of chromatographic and mass spectrometry parameters (see Zenodo file 3) to generate an extensive training dataset. In total, 360 mzML files (6.87 TB, comprising 34 million training instances) were simulated. Finally, we fine-tuned our quantification model using 36 existing DIA-MS files from human cell line samples, ensuring its applicability to real-world proteomics data.

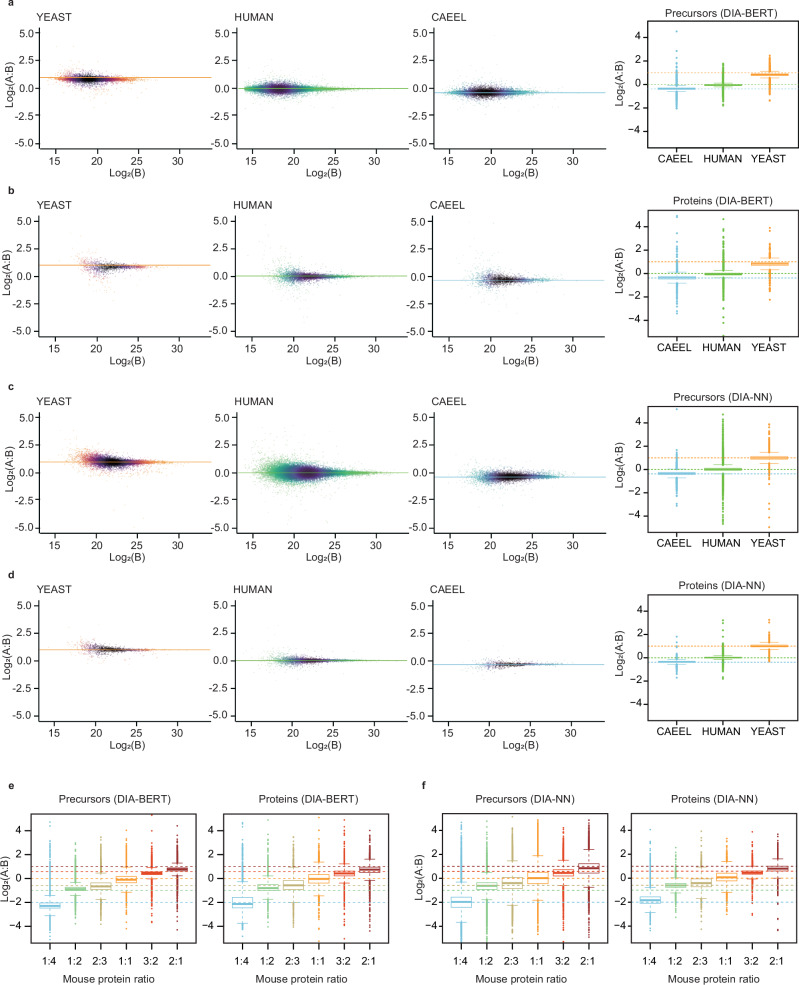

To evaluate the quantification model, we again utilized the three-species dataset20,22, consisting of human, yeast, and C. elegans samples with predefined pairwise ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 1:1.3, respectively. For single-file searches, DIA-BERT demonstrated quantification performance comparable to DIA-NN, achieving average Spearman’s correlation coefficients of 0.94 for peptide precursor quantification and 0.92 for protein quantification. For combined searches (Zenodo file 4), cross-run normalization was applied (see Methods). The median log₂-ratios predicted by DIA-BERT for peptide precursors (−0.05, 0.84, and −0.36) and proteins (−0.05, 0.83, and −0.36) closely align with the theoretical values (0, 1, and −0.38) for each species (Fig. 2). Additionally, DIA-BERT exhibited a comparable median coefficient of variation (CV) for peptide precursors (4%) and proteins (8%), compared to DIA-NN’s CV values of 9% and 5%, respectively.

Fig. 2. The quantification performance of DIA-BERT.

a–d, Quantification precision was evaluated using a proteome dataset comprising three different species. Yeast and C. elegans peptide mixtures were spiked into a human peptide sample at two different ratios (A and B), with three replicate injections per condition20,22. a The peptide precursor quantification by DIA-BERT. b The protein quantification by DIA-BERT. c The peptide precursor quantification by DIA-NN. d The protein quantification by DIA-NN. The quantification results are visualized as scatterplots in the left three panels and as boxplots in the right panel (boxes: interquartile range; whiskers: 1.5× interquartile range). The n numbers for peptide precursor ratios obtained from DIA-BERT and DIA-NN reports, respectively, are: 83,270 and 78,468 (human), 9322 and 10,188 (yeast), and 15,903 and 8857 (C. elegans). For protein ratios obtained from DIA-BERT and DIA-NN reports, n numbers are: 5976 and 5546 (human), 1463 and 1487 (yeast), and 2717 and 1089 (C. elegans). Orange color represents yeast; Green color represents human; Sky-blue color represents C. elegans. e, f Quantification benchmarking in the mouse-yeast dataset was performed using a single peptide preparation (yeast), which was spiked into a mouse peptide preparation at six different proportions, with five replicate injections for each21. e The peptide precursor and protein quantification by DIA-BERT. f The peptide precursor and protein quantification by DIA-NN. The quantification results are visualized using boxplots (boxes: interquartile range; whiskers: 1.5× interquartile range). The n numbers for peptide precursor ratios obtained from DIA-BERT and DIA-NN reports, respectively, are: 11,560 and 16,032 (mouse protein ratio 1:4), 24,908 and 30,415 (1:2), 25,226 and 31,118 (2:3), 29,833 and 35,901 (1:1), 35,006 and 42,084 (3:2), and 36,119 and 42,560 (2:1). For protein ratios obtained from DIA-BERT and DIA-NN reports, respectively, n numbers are: 2494 and 2759 (mouse protein ratio 1:4), 3891 and 4015 (1:2), 3925 and 4094 (2:3), 4307 and 4405 (1:1), 4578 and 4579 (3:2), and 4622 and 4599 (2:1). For panels (e, f), different colors represent different mouse protein ratios: light blue (1:4), light green (1:2), olive green (2:3), yellow (1:1), red (3:2), and brown (2:1). The center of boxplots (a–f) represents the median value. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To evaluate the impact of fragment ion intensity on quantification model generalization, we trained Model1 using 36 human DIA-MS files, while Models 2 and 3 were pre-trained on simulated DIA-MS files with relatively low and high fragment ion intensities, then fine-tuned on the same 36 human DIA-MS files. These models were then integrated into DIA-BERT as DIA-BERT_Model1, DIA-BERT_Model2, and DIA-BERT_Model3. To estimate the quantification models, we selected high- and low-abundance peptide precursors and proteins. High and low abundance were defined as the top and bottom 25%, respectively, based on quantification results from the three-species dataset analyzed with DIA-NN.

Compared to theoretical log₂(A:B) values (human: 0, yeast: 1, C. elegans: -0.38), DIA-BERT_Model2 outperformed DIA-BERT_Model3 for the relatively low-abundance peptide precursors and proteins, while DIA-BERT_Model3 excelled in the relatively high-abundance peptide precursors and proteins (Zenodo file 5). DIA-BERT_Model1 performed the worst. These results suggest that the simulated data with relatively high fragment ion intensities improvequantification of the relatively high-abundance peptide precursors and proteins, while the simulated data with the relatively low fragment ion intensities enhance quantification of the relatively low-abundance peptide precursors and proteins. DIA-BERT maintained consistent performance across all abundance levels (Zenodo file 5), whereas DIA-NN exhibited greater variability (CV = 0.14) than DIA-BERT (CV = 0.05) in the relatively low-abundance peptide precursors and proteins.

To further validate the quantification model, we analyzed a mouse-yeast hybrid proteome dataset21 comprising six mixtures with varying mouse-to-yeast ratios: 5:95, 10:90, 13:87, 20:80, 30:70, and 40:60. The 20:80 hybrid sample was set as the reference sample. Compared with this reference sample, this dataset features a wide range of mouse protein ratios (1:4, 1:2, 2:3, 1:1, 3:2, and 2:1). In the combined search analysis (Zenodo file 4), DIA-BERT achieved median log₂-ratios of −2.29, −0.88, −0.66, −0.1, 0.45, and 0.77 for peptide precursors respectively and −2.14, −0.8, −0.56, −0.03, 0.43, and 0.74 for proteins respectively, closely matching the theoretical values (−2, −1, −0.58, 0, 0.58, and 1) (Fig. 2).

In contrast, DIA-NN produced median log₂-ratios of −1.97, −0.62, −0.4, 0.02, 0.46, and 0.84 for peptide precursors respectively and −1.84, −0.6, −0.4, 0.07, 0.46, and 0.8 for proteins respectively. Notably, at the 1:2 mouse protein ratio, DIA-BERT (peptide precursors: −0.88; proteins: −0.8) demonstrated higher accuracy than DIA-NN (peptide precursors: −0.62; proteins: −0.6). Additionally, DIA-BERT exhibited reasonable median coefficient of variation (CV) values (9% for peptide precursors and 16% for proteins) compared to DIA-NN (12% and 7%, respectively).

The quantitative peptide precursor and protein data from DIA-BERT for the mouse-yeast dataset correlated with that from DIA-NN (Spearman’s correlation coefficients of 0.89 for peptide precursors and 0.9 for proteins). But the coefficients were slightly lower than that for the three-species dataset (Spearman’s correlation coefficients of 0.94 for peptide precursors and 0.92 for proteins). This discrepancy may arise because DIA-BERT aligns more closely with theoretical values than DIA-NN.

DIA-BERT is designed for user-friendliness, featuring an intuitive graphical interface (GUI) and exporting results in CSV format. The GUI consists of four main sections: Input, Configuration, Run Progress, and Log (Supplementary Fig. 4), collectively streamlining the analysis workflow. The Input section allows users to easily set up raw file paths and customize the output directory. The Configuration section enables users to adjust key parameters, including the spectral library, run threads, GPU allocation, decoy method, RT normalization, m/z unit, RT peak size, RT unit, instrument, batch size, batch score size, fine-tune score, training epochs, protein inference, and cross-run quantification. The Run Progress section provides real-time monitoring, allowing users to run and stop analysis as needed. The Log section serves as a comprehensive runtime log, capturing key events, errors, warnings, and critical runtime details, helping users assess and troubleshoot their analyses.

Additionally, DIA-BERT allows independent execution of spectral library preprocessing (including decoy generation), single-file analysis, and cross-run quantification. This allows library preprocessing and cross-run quantification to be performed once per project, significantly reducing computational overhead.

In summary, DIA-BERT introduces a pre-trained transformer-based model that significantly enhances peptide precursor and protein identification across diverse DIA proteome datasets. This study demonstrates the power of pre-trained transformer models in DIA proteomics analysis, unlocking new possibilities for advancing understudied areas in the field.

Discussion

Beyond proteomics, DIA-BERT has the potential to be extended for DIA-based metabolomics and lipidomics analysis. Additionally, we present a transformer-based model for precise DIA quantification, leveraging simulated DIA datasets for training—a cost-effective approach that eliminates the need for complex and time-consuming experimental data generation.

Together, this work presents a powerful new tool for DIA-based identification and quantification, underscoring the transformative potential of pre-trained models and simulation-driven training in advancing DIA proteomics.

Like other large pretraining models, DIA-BERT requires GPU for both training and application due to its processing of large volumes of raw DIA spectra. This approach differs from software like DIA-NN, which extracts a limited set of peak group features for machine learning, allowing CPU processing but introducing information loss. DIA-BERT’s improved performance partly stems from considering more spectral information, necessitating GPU usage. We acknowledge that many scientists analyzing DIA data are not accustomed to working with GPUs. However, we respectfully argue that the trend in AI-empowered proteomics data analysis points towards increased GPU utilization in the future.

As a pre-training model, the performance of DIA-BERT heavily depends on the volume and characteristics of the training data. Since DIA-BERT version 1.0 is based on Orbitrap data, it is optimized for such datasets, which are widely used in DIA experiments. While some labs, including ours, also use timsTOF and tripleTOF for DIA-MS analysis, the current version of DIA-BERT was not trained with timsTOF and tripleTOF data. Therefore, we do not recommend applying this version to timsTOF or tripleTOF-based DIA files, although it may still work. The identification performance on these files may differ from that observed with Orbitrap-based datasets, especially since timsTOF DIA files contain CCS values, which are not included in the current version. The DIA-BERT can be upgraded in the future to accommodate timsTOF data and other instrument types. Ideally, a pre-trained model works best with data similar to the training set, but we recognize that it may be inconvenient for users to switch between models. Therefore, the longer-term goal is to build a comprehensive BERT model that integrates all relevant data types.

The performance of DIA-BERT on post-translational modifications (PTMs) and non-trypsin peptides has not been evaluated, and the data preprocessing pipeline is not yet fully tested and optimized for these scenarios, despite the model’s theoretical capability to handle PTMs and peptides digested by different enzymes.

Future work will focus on improving model effectiveness by incorporating high-quality MS files from TOF instruments and spectral libraries with diverse peptide distribution to enhance identification accuracy in varied scenarios. Additionally, efforts will include evaluating performance on PTMs and non-trypsin peptides, testing and optimizing the data preprocessing pipeline to ensure reliable identification in these scenarios. Finally, inference efficiency will be enhanced using techniques like quantization and model pruning, ensuring both applicability and computational efficiency.

Methods

Mass spectrometry files used in training model

Mass spectrometry files were collected from PRIDE database (PXD033475, PXD016400, PXD023139, PXD025560, PXD032191, PXD033515, PXD034913, PXD021197, PXD026302, PXD034803, PXD023584, and PXD037428).

Preparation of the training set for pre-filtering model

The 952 files were analyzed for precursor identification using DIA-NN8 (version 1.8.1), DIA-NN (version 1.7.12, downloaded from https://github.com/YuAirLab/Alpha-Tri12), and Spectronaut5 (version 14.6). The parameters of DIA-NN (version 1.8.1) were set as ‘--qvalue 0.01 --gen-spec-lib --min-fr-mz 200 --max-fr-mz 1800 --met-excision --cut K*,R* --missed-cleavages 1 --min-pep-len 7 --max-pep-len 30 --min-pr-mz 300 --max-pr-mz 1800 --min-pr-charge 2 --max-pr-charge 4 --unimod4 --var-mods 1 --var-mod UniMod:35,15.994915,M --int-removal 1 --relaxed-prot-inf --smart-profiling --quant-fr 6 --no-prot-inf --verbose 4 --predictor --matrices’. The DIA-NN (version 1.7.12) parameters were configured identically to those of DIA-NN (version 1.8.1), except for the q-value cutoff, which was set to 0.1. The parameters of Spectronaut were set as default without cross run normalization.

Target precursors identified by DIA-NN (version 1.8.1) and Spectronaut (version 14.6) were used as positive samples, while decoy precursors identified by DIA-NN (version 1.7.12) served as negative samples. If the number of decoy precursors identified by DIA-NN (version 1.7.12) exceeded the total number of target precursors identified by DIA-NN (version 1.8.1) and Spectronaut, those decoy precursors with higher q-values were removed to balance the number of positive and negative samples.

Decoy precursors were acquired using DIA-NN (version 1.7.12), which can output decoy precursors along with the retention times (RTs)of their peak groups. DPHL v.219 was utilized as the spectral library for library-based database searches. Decoy sequences were generated using mutation methods. The FDR threshold for all the database searches was set to 0.01.

For each precursor identified in each mass spectrometry file, peak groups were extracted based on the specified retention time (RT), as well as the precursor’s m/z and fragment m/z from DPHL v.2. Peak groups were extracted from MS1 spectra to include the precursor m/z and its five isotopic peaks, and from MS2 spectra to include fragment m/z along with their corresponding heavy and light isotopic peaks. Each peak was extracted over an m/z range of [ion m/z − 20 ppm, ion m/z + 20 ppm] and covered 16 spectra (the spectrum corresponding to the precursor’s RT, plus seven spectra before and eight spectra after). The extracted peak group data from MS1 and MS2 were merged to create a 330 × 16 peak group matrix (the matrix was padded with zeros in the remaining rows if the precursor did not have enough fragments in the spectral library to fill the 330 rows).

For each target, in addition to extracting peak groups centered around the spectrum indicated by the RT in the identification results, we randomly selected one spectrum from the spectrum immediately before (denoted as RT - 1) or after (denoted as RT + 1) and extracted peak groups centered around it as positive samples. Similarly, for each decoy, peak groups were extracted centered around a randomly selected spectrum within the [RT - 5, RT + 5] range as negative samples. This additional sampling helps the model classify diverse peak groups correctly during the pre-filtering process.

Preparation of the training set for the pre-trained scoring model

Using the pre-filtering model, the best peak group for each precursor in the DPHL v.2 spectral library was determined in each mass spectrometry file. Specifically, a mapping function between iRT and RT was established for each mass spectrometry file. Then, for each precursor, the estimated RT was obtained based on its iRT in the spectral library using the mapping function. Peak groups were extracted for each spectrum within the [RT - n, RT + n] range and scored using the pre-filtering model. The peak group with the highest score for each precursor was retained. Precursors and their peak groups with scores above a certain experimentally determined threshold were kept as positive samples. The peak group with the highest score for each decoy was selected. For each MS file, an equal number of decoys to the targets were chosen as negative samples.

Preparation of the training set for the quantification model

A simulated dataset is prepared for the pre-training of quantification model. Empirically-corrected peptide library was build using EncyclopeDIA26,27 (version 2.12.30) and Prosit28 based on uniport human fasta file (20,427 reviewed proteins, downloaded on 2023/10/26). For EncyclopeDIA, we used the convert tool panel to convert fasta to Prosit csv file by default parameters. For Prosit, we select “Prosit_2020_intensity_hcd” as intensity prediction model, and selected “Prosit_2019_irt” as iRT prediction model.

After obtaining the empirically-corrected peptide library, it was split into smaller libraries. The m/z was corrected using the method used in Synthedia (considering the mass of iodoacetamide modification and proton). Every four smaller libraries were randomly combined into a sub-library. For RT shift situations, the iRT of each fragment was randomly shifted negatively or positively. For peptide precursor permeation, we randomly selected a fragment ion and changed its m/z and charge to match with the peptide precursor’s m/z and charge for each peptide precursor in the smaller library. To introduce a variety of intensities, we introduced two factors (F1 and F2) to adjust the relative intensity of the smaller libraries. F1 consists of a set of random numbers for coarse adjustments, while F2 consists of a set of random numbers for fine-tuning. Forty percent of the adjusted intensities were randomly set to zero. For adding heavy and light fragments, we randomly added heavy fragments with an 80% probability and light fragments with a 20% probability for each fragment. The peak group and label were extracted based on RT and TRUE area values recorded during simulation.

The quantification model was finally fine-tuned on a dataset extracted from 36 existing DIA-MS files of human cell line samples (PXD023139: WT and Ezh2-KO K562 cells; PXD033515: AML ex vivo cells). For each file, peak groups were extracted for target precursors identified by DIA-NN (version 1.9.2), and the sum of peak areas, serving as the label values, were extracted from the quantification result of DIA-NN (version 1.9.2). In our experiments, only the peaks of the first six fragments in the spectral library are included.

Identification and quantification model

The identification model primarily consists of five components. Initially, for each row (ion) in the 330 × 16 peak group matrix, attributes from the spectral library, like ion intensity and m/z, are encoded into numerical features using numerical embeddings and concatenated with the peak group matrix and input to the model. Secondly, the input peak group matrix is processed through two convolutional layers, which include convolution, average pooling, and layer normalization. Thirdly, a transformer model with 8 self-attention blocks is applied to the matrix to capture long-range correlations, and then the matrix is downsampled to a 1D tensor through two fully connected layers. Fourthly, attributes of the current MS file, such as gradient and instrument type, and attributes of the current precursor, such as iRT, delta-RT, m/z, charge and sequence length, are encoded into numerical features using numerical embeddings, concatenated, and then downsampled into a 1D tensor through two fully connected layers. Finally, the above two 1D tensors are concatenated, and two fully connected layers are applied to map them to the sample label space through binary cross-entropy loss.

The architecture of our peak area estimation Transformer model mirrors that of the model used for peak group scoring, with the primary distinction being the use of a regression loss function to estimate the sum of peak areas. In our experiments, only the peaks of the first six fragments in the spectral library are included during training and identification.

Precursor identification process

DIA-BERT employs a two-stage method for precursor identification in mass spectrometry files. The first stage is pre-filtering, which processes the mass spectrometry files similarly to the “Preparation of the training set for pre-trained scoring model” process, outputting a dataset composed of target and decoy precursors. In the second stage, the dataset is used to fine-tune a model initialized with the pre-trained scoring model. During fine-tuning, DIA-BERT splits the data into five parts to prevent overfitting by monitoring the decrease in validation set loss. DIA-BERT then re-scores the peak groups in the dataset using the fine-tuned scoring model and determines the identification results based on an FDR threshold of 0.01.

Cross-run normalization

DIA-BERT enables cross-run precursor ion normalization. The intensities of precursors were firstly normalized by dividing the summed precursor ion intensity in each acquisition. Precursors were sorted by their indexed retention time (iRT) and grouped into bins of 100 precursors. For each bin, the median retention time (RT) across samples was calculated, and RT normalization was performed by subtracting these medians from the RT values. Then the RT-dependent normalization was conducted. For the initial sample, precursors were sorted by RT and grouped into bins of 400. For subsequent samples, precursors were assigned to bins based on the RT boundaries defined by the first sample. The difference in bin rank between samples was calculated, and quantification values were marked as missing (NA) if the bin-difference exceeded 2. The bin ranks for each precursor across samples were adjusted to the median rank. Within each RT bin, precursor quantification was normalized by dividing by the median quantification value of that bin in each sample. Protein quantification was then performed using MaxLFQ23 utilizing the RT-dependent normalized precursors. The resulting protein quantification was used to further adjust precursor quantification. For each precursor within a protein, the intensities across samples were summed, and the summed values were converted to percentages, which served as adjustment factors. The adjusted precursor quantification was obtained by multiplying the protein quantification by these factors. Finally, any precursor quantification associated with NA values in the RT-dependent normalized matrix was also set to NA.

Spectral library building

For the two-species spectral library, we first built a yeast library by analyzing all yeast DDA data from QE HF and the corresponding fasta file (6727 proteins) from the public database21 (IPX0004576000, iProX). Peptides identical to those in the human library (DPHL v.2) were removed before merging the two libraries. Similarly, for the mouse-yeast library, we used all mouse and yeast DDA data with the corresponding fasta file (23,813 proteins) from the same database. Both libraries were constructed using Spectronaut (v14.6) without selecting fragments per peptide.

Conservative FDR estimation using the two-species spectral library

The estimation is demonstrated in previous studies8,21. Briefly, the human tissue proteomic datasets (Fig. 1b–d, Supplementary Fig. 1–2) were analyzed using each software tool with the two-species spectral library described above. Precursors or proteins with a q-value < 0.01 were considered identified. The numbers of identified human and yeast precursors or proteins were then calculated ([human IDs] and [yeast IDs], respectively).

A conservative FDR estimate was then obtained:

Benchmark experiment

For identification comparisons, including the identification of peptide precursors and proteins, as well as the quantification correlations, each benchmarking file was independently searched using DIA-NN (version 1.9.2). For quantification comparisons, proteome files from three species (n = 6) and mouse-yeast (n = 35) were processed with DIA-NN (version 1.9.2) using combined search, respectively. The parameters were set as ‘--qvalue 0.01 --cut K*,R* --min-fr-mz 200 --max-fr-mz 1800 --missed-cleavages 1 --min-pep-len 7 --max-pep-len 30 --min-pr-mz 300 --max-pr-mz 1800 --min-pr-charge 2 --max-pr-charge 4 --unimod4 --var-mods 1 --var-mod UniMod:35,15.994915,M --relaxed-prot-inf --rt-profiling --pg-level 0’. For the library-based database search, the two-species library was used for the human proteome search, while a spectral library from our previous work20 and a re-build mouse-yeast library was used for the three-species and mouse-yeast database search.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study and its coauthors were jointly supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFA1301600 to T.G.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Key Joint Research Program): Systematic identification and functional characterization of understudied proteins in multiple cancers using proteomics (Grant No. U24A20476 to T.G.). We also acknowledge support from the Pioneer and Leading Goose R&D Program of Zhejiang (Grant No. 2024SSYS0035 to T.G.), the Funded by the State Key Laboratory of Medical Proteomics (Grant No. SKLP-K202406 to T.G.), and the Westlake Educational Foundation. Additionally, we thank the Westlake University Supercomputer Center for assistance with data analysis and storage.

Author contributions

T.G. acquired funding for and supervised the project. T.G. and Y.C. conceptualized the research and provided supervision. Y.C. designed the methodology and setting the stage for the research implementation. P.L. implemented the overall experiment pipeline. Z.N. developed the data preprocessing component and DIA-BERT software system. Z.L. implemented the simulation component and produced the simulated data. Z.L., Z.N., and Y.S. curated the data. P.L., Z.L., Z.N., Y.S., X.Z., and Y.Z. conducted the model parameter tuning and carried out analyses. Z.L. devised benchmark experiments and drafted initial manuscript with contribution from P.L. and Z.N. Z.L., T.G., Y.C., and Y.S. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Liang Qiao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The matrix data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file and Zenodo files which have been deposited in the Zenodo repository29 [10.5281/zenodo.15087104]. Accession codes used in this study are listed below: PXD033475, PXD016400, PXD023139, PXD025560, PXD032191, PXD033515, PXD034913, PXD021197, PXD026302, PXD034803, PXD023584, PXD037428.

Code availability

The codes17 in this study are available at https://github.com/guomics-lab/DIA-BERT. The executable version of DIA-BERT and manual are available at https://guomics.com/DIA-BERT/.

Competing interests

T.G. is the founder of Westlake Omics (Hangzhou) Biotechnology Co., Ltd., while P.L. is staff of this company. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zhiwei Liu, Pu Liu, Yingying Sun.

Contributor Information

Yi Chen, Email: chenyi@westlake.edu.cn.

Tiannan Guo, Email: guotiannan@westlake.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-58866-4.

References

- 1.Zhang, F., Ge, W., Ruan, G., Cai, X. & Guo, T. Data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry-based proteomics and software tools: a glimpse in 2020. Proteomics.20, e1900276 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitata, R. B., Yang, J. C. & Chen, Y. J. Advances in data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry towards comprehensive digital proteome landscape. Mass Spectrom. Rev.42, 2324–2348 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lou, R. & Shui, W. Acquisition and analysis of DIA-based proteomic data: a comprehensive Survey in 2023. Mol. Cell Proteom.23, 100712 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rost, H. L. et al. OpenSWATH enables automated, targeted analysis of data-independent acquisition MS data. Nat. Biotechnol.32, 219–223 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruderer, R. et al. Extending the limits of quantitative proteome profiling with data-independent acquisition and application to acetaminophen-treated three-dimensional liver microtissues. Mol. Cell Proteom.14, 1400–1410 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiter, L. et al. mProphet: automated data processing and statistical validation for large-scale SRM experiments. Nat. Methods.8, 430–435 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacLean, B. et al. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics.26, 966–968 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demichev, V., Messner, C. B., Vernardis, S. I., Lilley, K. S. & Ralser, M. DIA-NN: neural networks and interference correction enable deep proteome coverage in high throughput. Nat. Methods.17, 41–44 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinitcyn, P. et al. MaxDIA enables library-based and library-free data-independent acquisition proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol.39, 1563–1573 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peckner, R. et al. Specter: linear deconvolution for targeted analysis of data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry proteomics. Nat. Methods.15, 371–378 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao, M. et al. Deep representation features from DreamDIA(XMBD) improve the analysis of data-independent acquisition proteomics. Commun. Biol.4, 1190 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song, J. & Yu, C. Alpha-Tri: a deep neural network for scoring the similarity between predicted and measured spectra improves peptide identification of DIA data. Bioinformatics.38, 1525–1531 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song, J. & Yu, C. Alpha-XIC: a deep neural network for scoring the coelution of peak groups improves peptide identification by data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry. Bioinformatics.38, 38–43 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput.9, 1735–1780 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. (San Francisco, California, USA, 2016).

- 16.Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, 2019).

- 17.Liu Z, et al. DIA-BERT: pre-trained end-to-end transformer models for enhanced DIA proteomics data analysis. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.15182347 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Ge, W. et al. Computational optimization of spectral library size improves DIA-MS proteome coverage and applications to 15 tumors. J. Proteome Res.20, 5392–5401 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue, Z. et al. DPHL v.2: an updated and comprehensive DIA pan-human assay library for quantifying more than 14,000 proteins. Patterns.4, 100792 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, F. et al. A comparative analysis of data analysis tools for data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell Proteom.22, 100623 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lou, R. et al. Benchmarking commonly used software suites and analysis workflows for DIA proteomics and phosphoproteomics. Nat. Commun.14, 94 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, T. et al. Combining precursor and fragment information for improved detection of differential abundance in data independent acquisition. Mol. Cell Proteom.19, 421–430 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox, J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol. Cell. Proteom.13, 2513–2526 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ammar, C., Schessner, J. P., Willems, S., Michaelis, A. C. & Mann, M. Accurate label-free quantification by directLFQ to compare unlimited numbers of proteomes. Mol. Cell Proteom.22, 100581 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leeming, M. G., Ang, C. S., Nie, S., Varshney, S. & Williamson, N. A. Simulation of mass spectrometry-based proteomics data with Synthedia. Bioinform. Adv.3, vbac096 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Searle, B. C. et al. Generating high quality libraries for DIA MS with empirically corrected peptide predictions. Nat. Commun.11, 1548 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pino, L. K., Just, S. C., MacCoss, M. J. & Searle, B. C. Acquiring and analyzing data independent acquisition proteomics experiments without spectrum libraries. Mol. Cell Proteom.19, 1088–1103 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gessulat, S. et al. Prosit: proteome-wide prediction of peptide tandem mass spectra by deep learning. Nat. Methods.16, 509–518 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, Z. et al. DIA-BERT: pre-trained end-to-end transformer models for enhanced DIA proteomics data analysis. Zenodo.10.5281/zenodo.15087104 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data are provided with this paper. The matrix data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file and Zenodo files which have been deposited in the Zenodo repository29 [10.5281/zenodo.15087104]. Accession codes used in this study are listed below: PXD033475, PXD016400, PXD023139, PXD025560, PXD032191, PXD033515, PXD034913, PXD021197, PXD026302, PXD034803, PXD023584, PXD037428.

The codes17 in this study are available at https://github.com/guomics-lab/DIA-BERT. The executable version of DIA-BERT and manual are available at https://guomics.com/DIA-BERT/.