Abstract

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) is a life-threatening malignancy characterized by its aggressive progression and detrimental effects on the hematopoietic system. Early and accurate diagnosis is paramount to optimizing therapeutic interventions and improving clinical outcomes. This study introduces a novel diagnostic framework that synergizes the EfficientNet-B7 architecture with Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) methodologies to address challenges in performance, computational efficiency, and explainability. The proposed model achieves improved diagnostic performance, with accuracies exceeding 96% on the Taleqani Hospital dataset and 95.50% on the C-NMC-19 and Multi-Cancer datasets. Rigorous evaluation across multiple metrics-including Area Under the Curve (AUC), mean Average Precision (mAP), Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score-demonstrates the model’s robustness and establishes its superiority over state-of-the-art architectures namely VGG-19, InceptionResNetV2, ResNet50, DenseNet50 and AlexNet . Furthermore, the framework significantly reduces computational overhead, achieving up to 40% faster inference times, thereby enhancing its clinical applicability. To address the opacity inherent in Deep learning (DL) models, the framework integrates advanced XAI techniques, including Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM), Class Activation Mapping (CAM), Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), and Integrated Gradients (IG), providing transparent and explainable insights into model predictions. This fusion of high diagnostic precision, computational efficiency, and explainability positions the proposed framework as a transformative tool for ALL diagnosis, bridging the gap between cutting-edge AI technologies and practical clinical deployment.

Keywords: Explainable artificial intelligence, XAI for medical diagnosis, EXplainble medical imaging, ALL detection, Decision support system, Responsible AI

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Engineering

Introduction

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) is a hematological malignancy characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal white blood cells, disrupting normal hematopoietic function. This aggressive progression, compounded by its impact on the immune system, makes ALL a significant global health challenge1. Projections from the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate a nearly 50% increase in cancer incidence and mortality rates by 2040 (https://platform.who.int/mortality/themes/theme-details/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/MDB/leukaemia). This alarming statistic underscores the critical need for advancements in diagnostic methodologies to facilitate timely and accurate detection2.

Traditional diagnostic methods, while effective, suffer from inherent limitations, including their invasive nature, time-intensive processes, and susceptibility to diagnostic inaccuracies. Microscopic differentiation between normal and ALL cells is further hindered by technical issues such as illumination errors and staining artifacts3. The advent of medical imaging and computational techniques offers a non-invasive alternative; however, manual interpretation of extensive datasets by radiologists remains labor-intensive and prone to errors, particularly when subtle cellular variations are critical for diagnosis.

DL-based methodologies have emerged as transformative methods in the diagnosis and classification of ALL. Numerous studies2,4–6 have explored the potential of various architectures, including VGG-19, InceptionResNetV2, DenseNet-121, and EfficientNet-B3, among others. While these models have demonstrated promising diagnostic performance, their adoption in clinical settings is constrained by computational inefficiencies, which result in significant processing times7,8. This computational overhead poses a critical bottleneck, particularly in time-sensitive medical scenarios where rapid decision-making is essential.

Another critical limitation of existing DL models lies in their lack of explainability. The “black-box” nature of these models often leaves patients, clinicians, and stakeholders unable to comprehend the decision-making process, thereby undermining trust and adoption9,10. Addressing this gap is crucial for fostering confidence in DL-driven diagnostic tools, ensuring their effective integration into Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS).

Motivated by these challenges, this study proposes a novel diagnostic framework for ALL that utilising the EfficientNet-B7 architecture, augmented with XAI techniques. The proposed framework addresses key technical gaps by delivering state-of-the-art diagnostic accuracy while significantly reducing computational time. To enhance explainability, XAI methodologies namely Grad-CAM11, CAM12, LIME13, and IG14 are integrated, providing transparent insights into model decisions and promoting trust among healthcare practitioners.

This study aims to address the following research questions:

R1: How can the diagnostic acculturates of ALL prediction models be improved while maintaining computational efficiency for real-time clinical applications?

R2: What are the key technical challenges in integrating XAI into ALL diagnosis, and how can these be overcome to enhance model explainability?

R3: To what extent can XAI methodologies improve trust and transparency in DL-based diagnostic frameworks for medical practitioners and patients?

To address these research questions, this study bridges gaps in diagnostic performance, computational efficiency, and model explainability through a novel framework.The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

Development of a robust diagnostic framework using EfficientNet-B7, demonstrating improved performance compared to traditional architectures namely VGG-19, InceptionResNetV2, ResNet50, DenseNet50 and AlexNet. The framework achieves high accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, mAP, and AUC across multiple datasets.

Significant reduction in computational time, improving the framework’s viability for real-time clinical applications and addressing critical bottlenecks in medical diagnostics.

Integration of XAI methodologies, including Grad-CAM, CAM, LIME, and IG, to provide interpretable and transparent explanations of model predictions, thereby enhancing trust and confidence in automated diagnostic systems.

This paper is structured as follows: The section on relevant studies reviews the current advancements and identifies gaps in the field. The methodology section elaborates on the proposed framework and the benchmark models used for performance comparison. The experimental results and discussion section presents key findings, highlighting the strengths of the proposed approach. Finally, the conclusion reflects on the study’s contributions, acknowledges its limitations, and outlines exciting directions for future research to build upon this work.

Relevant studies

In the extant literature, research works in the scope of detection, identification, classification and use of XAI in ALL were considered.

Mondal et al.2 utilised a CNN for the automated detection of ALL by exploring a weighted ensemble to enhance classification. The model was trained and validated using the C-NMC-19 dataset by incorporating various augmentation methods. A non-invasive diagnosis of ALL from images was presented by5 using VGG-16 and efficient channel attention (ECA) to distinguish cancerous and healthy cells through better feature extraction. An AI-based system was presented by15 to automate blast cell detection in microscopic images and to classify cells as either healthy or leukemic. The proposed method was tested on the ALL_IBD and CNMC-19 datasets. Kasani et. al.6 proposed a hybrid model that integrates various DL networks to identify leukemic B-lymphoblasts and enhances model performance using data augmentation with transfer learning strategies. Similarly, the researchers of16 utilised EfficientNet-B3 for ALL classification using the C-NMC-19 dataset with balancing and pre-processing techniques. Liu et.al.17 employed deep bagging ensemble learning (DLbased) for ALL cells classification using microscopic images. The authors of19 combined the vision transformer model and CNN for the classification of cancer and normal cells. The dataset was balanced using the data enhancement method (DERS).

In a study conducted by Abir et.al.4 developed a model for automatically detecting ALL by integrating various transfer learning approaches such as Inception-V3, ResNetV2, VGG-19 and InceptionResNetV2. The authors presented LIME as the XAI method in their research work. This study18 explored SHAP as an XAI approach and new therapeutic opportunities for histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in childhood acute leukaemia using drug repurposing approaches and molecular analysis.

Several studies have explored advanced techniques in EEG recognition, fault diagnosis, and neuroimaging-based CAD to address domain-specific challenges. DMV-MAT20 introduced a subject-specific EEG recognition framework leveraging multiview networks and module adaptation transfer to improve feature diversity and transfer performance, while STS-HGCN-AL21 utilized a spatio-temporal-spectral hierarchical graph convolutional network for patient-specific seizure prediction, incorporating active learning to adapt preictal intervals. In fault diagnosis, FEM simulation combined with ELM was applied for gear fault classification22, and a MED-based CNN23 approach was used for axial piston pump fault detection through automatic feature learning. Similarly, the PM-SMEKLM algorithm extended transfer learning (TL) to neuroimaging-based CAD24, using sparse learning and cross-domain transformations to diagnose brain diseases. However, these approaches did not incorporate explainability methods to interpret model decisions, limiting their utility in sensitive applications such as healthcare. Additionally, computational time was not reported in these studies, raising concerns about their practicality for real-time applications. Recent advancements advancements in ensemble learning (EL) frameworks for cervical cancer25 and COVID-19 detection26, showcasing techniques like feature fusion, ConvLSTM layers, and Grad-CAM-based interpretability. However, these methods lack computational efficiency and broader explainability integration.

This study explored various architectural methodologies and evaluation criteria, with the use of EfficientNet-B7 and integration of XAI standing as a novel contribution. While prior literature presented in Table 1 applied models like VGG-16/19, Inception-V3, ResNetV2/50, DenseNet121, and EfficientNet-B3, our choice of EfficientNet-B7 strikes a strategic balance between accuracy and efficiency. We employed comprehensive metrics, including AUC and mAP, and utilized the C-NMC-19, Multi cancer and Taleqani Hospital datasets, demonstrating improved performance. Unlike other studies, we integrated XAI techniques (Grad-CAM, CAM, LIME and IG), providing enhanced model explainability and addressing computational time, which has been largely overlooked in existing work. Thus, this study sets a potential new benchmark for XAI in ALL research.

Table 1.

Comparison with extant literature.

| Researchers | Architecture | Perf-metrics | Dataset | XAI integration | Computational time provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mondal et al.2 | VGG-16, InceptionResNet-V2, MobileNet, DenseNet-121 | Accuracy, AUC | C-NMC-19 | No | No |

| Amin et al.5 | ECA-Net utilizing VGG-16 | Accuracy, sensitivity, specificity | C-NMC-19 | No | No |

| Khandekar et al.15 | ResNet50, ResNext50, VGG-16, YOLOv4 | mAP, Recall, F1-score | C-NMC-19 | No | No |

| Kasani et al.6 | Aggregation-based architecture of VGG19 and NASNetLarge | Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score | ISBI-19 | No | No |

| El-Ghani et al.16 | EfficientNet-B3 | Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score | C-NMC-19 | No | No |

| Ying et al.17 | Deep Ensemble Learning | F1-score | ISBI-19 | No | No |

| Jiang et al. | ViT-CNN | Accuracy, precision | ISBI-19 | No | No |

| Abir et al.4 | Inception-V3 | Accuracy, F1-score | ISBI-19 | LIME | No |

| Uysal et al.18 | Decision Tree Regressor | Accuracy, F1-score | ChEMBL version | SHAP | No |

| Our proposed | EfficientNet-B7 | Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, AUC, mAP | C-NMC-19, Multi-cancer, Taleqani Hospital | Grad-CAM, CAM, LIME, IG | Yes |

Materials and methods

The proposed workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1, highlighting the key steps. It involves diagnostic screening, data collection, pre-processing, and feature extraction using EfficientNet-B7. The model undergoes compilation and training, followed by evaluation based on several metrics and computational efficiency. Finally, XAI methods like Grad-CAM, CAM, LIME, and IG are integrated to provide interpretable visual explanations, ensuring the framework is both accurate and transparent,enabling health staff, patients, and tech enthusiasts to better understand the proposed model’s decisions.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of the proposed methodology.

Experimental environment and implementation setup

The experiments were implemented using Python, selected for its flexibility and extensive ecosystem of DL libraries such as TensorFlow and Keras presented in Table 2. Model training and evaluation were conducted on a high-performance computational setup equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 5700X Eight-Core CPU and a 16GB NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU, ensuring efficient processing of DL workloads. The operating system utilized was Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, which provided a stable and optimized environment for executing computational tasks. To manage dependencies, Python virtual environments were created, ensuring consistency across experimental setups.

Table 2.

Implementation setup overview.

| Environmental details | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Operating system | Ubuntu 20.04 LTS |

| Processor | AMD Ryzen 7 5700X Eight-Core |

| Architecture | 64-bit |

| GPU | 16GB NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 |

| Programming language | Python |

| Framework | TensorFlow, Keras |

| Libraries utilised | Pandas, Numpy, cv2, Matplotlib, Seaborn, Scikit-learn, os |

The models were trained using the Adamax optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, batch size of 32, and early stopping to prevent overfitting. Additionally, TensorBoard was employed for real-time monitoring of the training process, allowing visualization of metrics such as accuracy and loss curves.

Description of datasets

Our study utilized three diverse datasets, each offering unique characteristics suitable for validating the proposed framework:

C-NMC-1927: This dataset contains either cancerous or normal cells derived from real-world microscopic images, consisting of 60% Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL) images and 40% normal images. Noise and illumination errors were corrected using a stain color normalization technique28, enhancing image quality. The dataset’s reliability is underpinned by the ground truth provided by expert oncologists, making it suitable for validating computational models.

Taleqani Hospital dataset29: Collected at the bone marrow laboratory of Taleqani Hospital in Tehran, this dataset includes 3,256 peripheral blood smear (PBS) images from 89 patients suspected of having ALL. The dataset is imbalanced and comprises meticulously prepared and stained images by skilled laboratory staff. The images underwent preprocessing, including resizing and normalization, to ensure compatibility with the proposed model.

Multi Cancer dataset30: This dataset includes 10,000 peripheral blood smear (PBS) images containing both ALL and healthy samples. Similar to the Taleqani Hospital dataset, it is imbalanced and comprises carefully prepared and stained images by professional staff. Preprocessing steps such as resizing and normalization were applied to standardize the dataset.

The datasets were divided into two subsets: training (75%) and testing (25%) to ensure sufficient data for both model training and performance evaluation. Stratified splitting was used to maintain the class distribution across the subsets, mitigating the impact of dataset imbalance and ensuring robust model evaluation.

Preprocessing

In the preprocessing stage, the considered datasets underwent a systematic filtration process to ensure uniformity and compatibility with the proposed framework. Let  represent the original dataset, where each image is denoted as

represent the original dataset, where each image is denoted as  , and its corresponding file extension is given by

, and its corresponding file extension is given by  . The filtration process is mathematically formulated in Eq1:

. The filtration process is mathematically formulated in Eq1:

|

1 |

where only images with valid extensions are retained, ensuring that corrupted or irrelevant files are removed. This step enhances data quality and prevents anomalies that could adversely affect model training.

Following filtration, the dataset was partitioned into training and testing subsets. Given a dataset  of size

of size  , a split ratio

, a split ratio  was applied to allocate images into training (

was applied to allocate images into training ( ) and testing (

) and testing ( ) sets:

) sets:

|

2 |

where  is selected to ensure sufficient training samples while maintaining a representative test set. This partitioning process, described in Eq. (2), is crucial for model generalization and robust performance evaluation.

is selected to ensure sufficient training samples while maintaining a representative test set. This partitioning process, described in Eq. (2), is crucial for model generalization and robust performance evaluation.

To meet the input dimensionality requirements of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)31, all images were resized to a fixed dimension of  pixels. Let an image

pixels. Let an image  be represented as a matrix of pixel intensities, presented in Eq3:

be represented as a matrix of pixel intensities, presented in Eq3:

|

3 |

where  and

and  denote the original height and width, respectively, and

denote the original height and width, respectively, and  represents the number of color channels. The resizing operation is performed as follows:

represents the number of color channels. The resizing operation is performed as follows:

|

4 |

where  is the transformed image with standardized dimensions

is the transformed image with standardized dimensions  . The transformation in Eq. (4) ensures uniform input size across the dataset, minimizes computational overhead, and facilitates the utilization of pre-trained CNN architectures, which typically require fixed input dimensions.

. The transformation in Eq. (4) ensures uniform input size across the dataset, minimizes computational overhead, and facilitates the utilization of pre-trained CNN architectures, which typically require fixed input dimensions.

Additionally, pixel intensities were normalized to the range  to improve training stability. If

to improve training stability. If  represents the pixel intensity at location

represents the pixel intensity at location  in the

in the  -th channel, normalization is applied as:

-th channel, normalization is applied as:

|

5 |

ensuring that all pixel values lie within a standard range. The normalization process, as defined in Eq. (5), prevents saturation effects and accelerates convergence during network training.

These preprocessing steps, detailed in Eqs. (1)-(5), play a critical role in optimizing dataset quality and ensuring the robustness of the proposed diagnostic framework.

Proposed model

In this study, we carefully selected methods and hyperparameters based on a combination of empirical practices and established best practices to optimize performance. The EfficientNet-B7 base model32 illustrated in Fig. 2, pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset, was utilized via the Keras framework. By leveraging pre-trained weights, the baseline model benefited from the rich features of ImageNet, enabling significant improvements in image recognition performance. EfficientNet-B7 is a convolutional neural network (CNN) with feed-forward training that progresses from the input layer to the classification layer, as shown in Eq. (6). The back-propagation of error begins at the classification phase and proceeds to the input layer, completing one pass. Information is passed from neuron  of

of  th to neuron

th to neuron  of the

of the  th layer, where

th layer, where  is the connection weight between the two neurons within the

is the connection weight between the two neurons within the  th layer33,34.

th layer33,34.

|

6 |

The base model was configured without the top layer, allowing for a customized output layer tailored to the specific task requirements. To facilitate feature map reduction and abstraction, we applied max pooling after the base model output. Max pooling enhanced the most salient features through spatial down-sampling, which not only reduced computational load but also ensured robustness to variations in input images. Following the initial output, batch normalization was employed to normalize inputs for subsequent layers using adjustment and activation scaling.

Fig. 2.

Proposed model (EfficientNetB7) architecture.

Additionally, to address potential class imbalances in the datasets, we utilized class weighting during model training. This approach ensured that minority classes were appropriately represented in the learning process, reducing bias in predictions. Furthermore, balanced datasets were created as part of the preprocessing stage to mitigate inherent data bias.

To further optimize performance, a dense layer with L1 and L2 regularization35,36 was employed to reduce overfitting, as illustrated in Eq. (7). The regularization parameters were carefully chosen to balance model complexity and the fidelity of the training data.

|

7 |

Here,  represents weights,

represents weights,  is the number of parameters in the model, and

is the number of parameters in the model, and  is the regularization strength. Techniques such as batch normalization, regularization, and dropout37, as shown in Eq. (8), were integrated to fine-tune the balance between reducing overfitting and maintaining model complexity and integrity, aligning with the unique aspects of the training dataset36.

is the regularization strength. Techniques such as batch normalization, regularization, and dropout37, as shown in Eq. (8), were integrated to fine-tune the balance between reducing overfitting and maintaining model complexity and integrity, aligning with the unique aspects of the training dataset36.

|

8 |

Where  denotes a neuron within the

denotes a neuron within the  th layer employing the activation function

th layer employing the activation function  . Here,

. Here,  is a random variable,

is a random variable,  is the input, and

is the input, and  represents the output of this neuron. The EfficientNet-B7 model concludes with an output layer integrating a dense layer with a sigmoid activation function for classification. During the model compilation phase, the Adamax optimizer was employed due to its proven effectiveness in handling embeddings and improving model optimization38. The hyper-parameter settings used for training the proposed model are summarized in Table 3, where key parameters such as dropout rate, optimizer, learning rate, batch size, number of epochs, activation function, and loss function are specified to ensure optimal performance and convergence.

represents the output of this neuron. The EfficientNet-B7 model concludes with an output layer integrating a dense layer with a sigmoid activation function for classification. During the model compilation phase, the Adamax optimizer was employed due to its proven effectiveness in handling embeddings and improving model optimization38. The hyper-parameter settings used for training the proposed model are summarized in Table 3, where key parameters such as dropout rate, optimizer, learning rate, batch size, number of epochs, activation function, and loss function are specified to ensure optimal performance and convergence.

Table 3.

Hyper-parameter settings for proposed model training.

| Hyper-parameters | Details |

|---|---|

| Dropout | 0.2 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Epochs | 30 |

| Activation function | ReLU |

| Loss function | Binary cross-entropy |

Benchmark architectures

In this study, several DL architectures, namely VGG-19, InceptionResNetV2 and ResNet50 were trained and evaluated as benchmark models. These models have been widely adopted in ALL diagnosis due to their valuable performance.

VGG-19

VGG-19 is a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture introduced by the Visual Geometry Group at the University of Oxford. It comprises 19 layers, including 16 convolutional layers, three fully connected layers, and a softmax classifier. The design of VGG-19 emphasizes simplicity by using fixed small  convolutional filters across all layers. This approach allows the model to capture spatial hierarchies while increasing depth.

convolutional filters across all layers. This approach allows the model to capture spatial hierarchies while increasing depth.

The working mechanism of VGG-19 includes convolutional operations to extract feature representations, max pooling layers to reduce spatial dimensions, and fully connected layers to map features to class probabilities. Mathematically, the convolution operation for generating a feature map  can be expressed as shown in Eq. (9):

can be expressed as shown in Eq. (9):

|

9 |

where  represents the convolutional kernel,

represents the convolutional kernel,  is the input image, and

is the input image, and  is the resulting feature map.

is the resulting feature map.

InceptionResNetV2

InceptionResNetV2 combines the strengths of Inception modules and residual connections, achieving efficient multi-scale feature extraction while mitigating the vanishing gradient problem. The Inception module applies parallel convolution operations of varying kernel sizes, such as  ,

,  , and

, and  , allowing the network to capture features at different spatial scales. Residual connections further enhance this architecture by introducing shortcut paths that bypass layers, ensuring gradient stability during backpropagation.

, allowing the network to capture features at different spatial scales. Residual connections further enhance this architecture by introducing shortcut paths that bypass layers, ensuring gradient stability during backpropagation.

The mathematical formulation for a residual block in this architecture is given by:

|

10 |

where  represents the transformations applied by the block, and

represents the transformations applied by the block, and  is the residual connection. As shown in Eq. (10), the output

is the residual connection. As shown in Eq. (10), the output  is obtained by summing the transformed input and the original input, ensuring that the network can learn both identity mappings and complex transformations effectively.

is obtained by summing the transformed input and the original input, ensuring that the network can learn both identity mappings and complex transformations effectively.

ResNet50

ResNet50 is another widely used architecture designed to address the degradation problem in very deep networks. This model features 50 layers and employs residual learning through identity mappings. These residual connections allow input features to flow directly to later layers, enabling efficient gradient propagation and improving optimization.

A single residual block in ResNet50 can be expressed as:

|

11 |

where  and

and  are the weights of the convolutional layers,

are the weights of the convolutional layers,  is the bias, and

is the bias, and  denotes the activation function (e.g., ReLU). The residual connection, represented by the term

denotes the activation function (e.g., ReLU). The residual connection, represented by the term  , facilitates the flow of information and gradients through the network by directly adding the input to the output of the transformed block.

, facilitates the flow of information and gradients through the network by directly adding the input to the output of the transformed block.

The introduction of batch normalization within ResNet50 further stabilizes training by normalizing intermediate layer activations, thereby enhancing the model’s robustness and convergence properties, as shown in Eq. (11).

DenseNet50

DenseNet50 is a CNN architecture that excels in medical image classification due to its efficient parameter usage and dense connectivity. Each layer in DenseNet50 connects to all subsequent layers within a dense block, enabling effective feature propagation and reuse. The input to the  -th layer is defined as:

-th layer is defined as:

|

12 |

where  includes batch normalization (BN), ReLU, and convolution, and

includes batch normalization (BN), ReLU, and convolution, and  denotes concatenation. Dense blocks extract hierarchical features, with a growth rate

denotes concatenation. Dense blocks extract hierarchical features, with a growth rate  determining the number of new features added per layer. The total number of output features at layer

determining the number of new features added per layer. The total number of output features at layer  is given by:

is given by:

|

13 |

where  is the initial feature count. Transition layers are used between dense blocks to reduce the feature dimensions. These layers combine 1x1 convolutions and average pooling, as expressed in:

is the initial feature count. Transition layers are used between dense blocks to reduce the feature dimensions. These layers combine 1x1 convolutions and average pooling, as expressed in:

|

14 |

where  and

and  represent the weights and biases, and

represent the weights and biases, and  denotes the average pooling operation.

denotes the average pooling operation.

Global Average Pooling (GAP) reduces the spatial dimensions of the feature maps to a feature vector, which is passed through a softmax function to compute class probabilities. This process is defined as:

|

15 |

where  is the logit for class

is the logit for class  , and

, and  is the total number of classes. During training, DenseNet50 minimizes the cross-entropy loss function, defined as:

is the total number of classes. During training, DenseNet50 minimizes the cross-entropy loss function, defined as:

|

16 |

where  is the ground truth label.

is the ground truth label.

Equation 12 highlights how each layer reuses the features from preceding layers, ensuring effective feature propagation. The growth rate of features, shown in Equation 13, demonstrates the model’s ability to incrementally build on extracted features. The dimensionality reduction in transition layers, described in Equation 14, ensures computational efficiency. Finally, Equations 15 and 16 describe the probability computation and loss function, respectively, which are central to the classification task.

AlexNet

AlexNet is a deep CNN designed for efficient image classification, making it suitable for medical imaging tasks. Input images, typically of size  , are normalized to ensure faster convergence during training. Feature extraction is performed in the convolutional layers using filters

, are normalized to ensure faster convergence during training. Feature extraction is performed in the convolutional layers using filters  , defined as:

, defined as:

|

17 |

where  represents the output at position

represents the output at position  , and

, and  is the bias term. The convolutional output is passed through a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function to introduce non-linearity, expressed as:

is the bias term. The convolutional output is passed through a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function to introduce non-linearity, expressed as:

|

18 |

Max pooling is applied to reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps while retaining important features. If the pooling kernel size is  , the pooling operation is given by:

, the pooling operation is given by:

|

19 |

The extracted features are flattened into a one-dimensional vector and passed through fully connected layers. The output of the fully connected layer is calculated as:

|

20 |

where  and

and  are the weights and biases, and

are the weights and biases, and  is the input vector. The final probabilities for each class are computed using the softmax function:

is the input vector. The final probabilities for each class are computed using the softmax function:

|

21 |

where  is the logit corresponding to class

is the logit corresponding to class  , and

, and  is the number of classes. During training, AlexNet minimizes the cross-entropy loss:

is the number of classes. During training, AlexNet minimizes the cross-entropy loss:

|

22 |

where  is the ground truth label.

is the ground truth label.

Equation 17 describes the feature extraction process through convolutional filters, while Equation 18 introduces non-linearity to the network. Equation 19 demonstrates how max pooling reduces spatial dimensions. The fully connected layers and their computation are detailed in Equation 20, with the softmax function and cross-entropy loss provided in Equations 21 and 22, respectively.

AlexNet’s ability to extract hierarchical features and its effective regularization techniques, such as dropout, make it a robust model for medical image classification tasks.

Integration of XAI

EfficientNet-B7 with its complex architecture extracts intricate features from the input cancerous images essential for high accuracy in ALL identification and classification. However, due to the deep architecture of this model, understanding the decision process for the Non-Tech community is challenging. In response to this gap, we employed XAI approaches namely LIME39, Grad-CAM40, CAM and IG14 to provide the visual explanation and interpretation of the image features which are influencing the model’s prediction.

Grad-CAM

Grad-CAM utilises the gradients of the last convolutional layer (top_activation) to generate a heatmap illustrated in Eq. (23) that illuminates the critical region within the image which affects the model decision.

|

23 |

The Eq. (23) represents this localization map for class  , where

, where  highlights important regions,

highlights important regions,  ensures non-negative output,

ensures non-negative output,  indicates the importance of feature map

indicates the importance of feature map  for class

for class  , and

, and  are the feature maps from convolutional layers.

are the feature maps from convolutional layers.

CAM

CAM12 provides a method to visually interpret a convolutional neural network’s decisions by highlighting regions of an image that are critical for a specific class prediction. CAM achieves this by leveraging the global average pooling layer to directly connect feature maps from the last convolutional layer to the final output. The importance of these feature maps is determined by the weights of the fully connected layer.

The localization map for class  , denoted as

, denoted as  , is mathematically represented as:

, is mathematically represented as:

|

24 |

where  represents the weight of the fully connected layer corresponding to feature map

represents the weight of the fully connected layer corresponding to feature map  for class

for class  , and

, and  denotes the activation at spatial location

denotes the activation at spatial location  of the

of the  -th feature map.

-th feature map.

Equation (24) highlights the regions of the image that contribute most to the network’s prediction for class  . By summing the weighted activations, CAM generates a class-specific heatmap that provides interpretability to convolutional neural network predictions, helping identify critical spatial regions in the input image.

. By summing the weighted activations, CAM generates a class-specific heatmap that provides interpretability to convolutional neural network predictions, helping identify critical spatial regions in the input image.

LIME

LIME provides an explanation by perturbing the input images, observing the changes in the model prediction, and pinpointing the image features that substantially impact the model’s prediction as shown in Eq. (25)41.

|

25 |

In Eq. (25),  measures the difference between the original model

measures the difference between the original model  and the interpretable model

and the interpretable model  , with

, with  as the proximity measure. Weights

as the proximity measure. Weights  are for perturbed samples

are for perturbed samples  .

.  is the complexity penalty for

is the complexity penalty for  .

.

IG

IG is an XAI approach that offers a way to attribute the prediction of the model to its input features, notably pixels for images by integrating the output gradients from a baseline to the actual image; thereby highlighting the role of an individual pixel in image analysis as shown in Eq. (26).

|

26 |

Here,  is the integrated gradient for feature

is the integrated gradient for feature  ,

,  is the actual input,

is the actual input,  is the baseline input, and

is the baseline input, and  scales the difference between inputs.

scales the difference between inputs.

Evaluation metrics

We utilized a series of evaluation metrics37 to gauge and benchmark the performance of the proposed model. Accuracy, precision, recall and f1-score stem from the confusion matrix. In addition, the area under the curve (AUC) and mean average precision are well-known performance evaluation metrics for AI models42.The confusion matrix, a fundamental tool in performance assessment, consists of True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN), which are defined within the context of this study as follows (Fig. 3):

True positive (TP): Instances where the model correctly identifies an image as ALL, and the corresponding ground truth label confirms the presence of ALL. This indicates a successful classification of a pathological case where malignant lymphoblasts, characterized by their large nuclei and abnormal morphology, proliferate uncontrollably, disrupting normal hematopoiesis.

True negative (TN): Cases where the model accurately predicts an image as Normal (Healthy), and the actual ground truth also corresponds to a healthy subject. This represents a correct exclusion of disease presence, ensuring that the model does not mistakenly detect pathology in normal blood samples.

False positive (FP): Instances where the model incorrectly classifies a Normal (Healthy) image as ALL, despite the ground truth indicating the absence of leukemia. This type of misclassification contributes to an increased false alarm rate, potentially leading to unnecessary clinical interventions, psychological distress for patients, and additional diagnostic testing.

False negative (FN): Cases where the model fails to detect ALL and instead classifies an image as Normal (Healthy), despite the ground truth confirming the presence of leukemia. This is the most critical misclassification type, as it poses significant clinical risks by failing to identify diseased cases, potentially delaying necessary medical treatment. In ALL cases, the presence of dysfunctional white blood cells (lymphoblasts) disrupts the normal immune function and blood cell production, leading to severe complications if left undiagnosed.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the confusion matrices for the proposed model across different datasets: (A) Taleqani Hospital dataset, (B) C-NMC-19 dataset, and (C) Multi cancer dataset. Each subfigure illustrates the model’s classification performance on the respective dataset.

Results and discussion

In this study, we employed the EfficientNet-B7, a forefront CNN architecture for the vital task of identification and classification of ALL utilising the microscopic images. Following the model’s training and validation phase, we integrated the XAI methodologies to demystify and explain the model’s prediction decision.

All diagnosis

Case study-Taleqani Hospital

The evaluation metrics for diagnosing ALL using the Talqani Hospital dataset are summarised in Table 4. These metrics include Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Area Under the Curve (AUC), Mean Average Precision (mAP), and computational time (in seconds), providing a thorough comparison of the benchmark models-VGG-19, InceptionResNetV2, and ResNet50-with the proposed model.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different models for ALL diagnosis on the Talqani Hospital dataset (Total images: 3256).

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | AUC (%) | mAP (%) | Computational time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG-19 | 89.56 | 89.51 | 89.56 | 89.50 | 90.01 | 89.04 | 89.9 |

| InceptionResNetV2 | 71.74 | 84.71 | 71.74 | 69.46 | 72.83 | 71.85 | 108.48 |

| ResNet50 | 89.80 | 91.66 | 89.80 | 89.08 | 88.90 | 89.45 | 121.28 |

| DenseNet50 | 86.41 | 82.66 | 84.13 | 86.50 | 88.17 | 88.15 | 129.27 |

| AlexNet | 84.71 | 83.16 | 84.13 | 86.50 | 88.17 | 84.19 | 121.33 |

| Our proposed | 96.78 | 97.00 | 96.25 | 96.57 | 99.85 | 99.56 | 59.28 |

VGG-19 achieved an accuracy of 89.56%, with Precision (89.51%) and Recall (89.56%) demonstrating balanced diagnostic performance. The F1-Score of 89.5% and AUC of 90.01% reflect a strong ability to differentiate classes, with an mAP of 89.04% indicating good overall performance. However, its computational time of 89.9 seconds highlights moderate efficiency, which could be a limiting factor for rapid diagnosis.

InceptionResNetV2 delivered suboptimal results, with an accuracy of 71.74% and an F1-Score of 69.46%, despite a relatively high Precision of 84.71%. Its Recall of 71.74% suggests a struggle in identifying all positive leukemia cases, and the AUC (72.83%) and mAP (71.85%) further underscore its limitations. Additionally, its computational time of 108.48 seconds makes it less suitable for clinical applications requiring timely results.

ResNet50 demonstrated better performance than VGG-19, achieving an accuracy of 89.8%, with Precision (91.66%) being the highest among the benchmark models. Its Recall (89.8%) and F1-Score (89.08%) indicate consistent diagnostic reliability, while the AUC (88.9%) and mAP (89.45%) reflect competitive class differentiation. However, with a computational time of 121.28 seconds, it is the least efficient model, presenting a trade-off between accuracy and computational cost.

DenseNet50 provides balanced performance across the evaluated metrics, achieving an accuracy of (86.41%). Its precision of (82.66%) and recall of (84.13%) result in an F1-Score of (86.50%. The AUC of (88.17%) demonstrates reasonable discriminatory power. However, DenseNet50’s computational time of (129.27 seconds) is the highest among all the tested models, highlighting its computational inefficiency despite its balanced performance.

AlexNet, while being a foundational architecture, demonstrates modest performance in this study. It achieves an accuracy of (84.71%), with a precision of (83.16%) and a recall of (84.13%), resulting in an F1-Score of (86.50%). The AUC of (88.17%) is comparable to DenseNet50. However, its computational time of (121.33 seconds) is high, indicating that while AlexNet provides satisfactory performance, it is not optimal for real-time or large-scale clinical applications.

The proposed model outperformed all benchmark models in every evaluated metric. It achieved an accuracy of 96.78%, with Precision (97%), Recall (96.25%), and an F1-Score (96.57%), demonstrating its ability to accurately and reliably diagnose ALL. Furthermore, the near-perfect AUC of 99.85% and mAP of 99.56% indicate exceptional class differentiation and prediction capability. Importantly, the proposed model required only 59.28 seconds for computation, making it the most efficient and effective solution for ALL diagnosis. These results highlight the superiority of the proposed model, particularly in its ability to combine high diagnostic accuracy with computational efficiency, making it suitable for clinical deployment.

The results in Table 4, combined with the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves shown in Fig. 4, clearly illustrate the potential of the proposed model as a robust and efficient diagnostic tool for ALL. The ROC curves, representing the classification performance for healthy and cancerous images, demonstrate the model’s strong ability to distinguish between the two classes, with high true positive rates significantly outperforming the random baseline. These findings highlight the model’s capability to meet the stringent demands of clinical settings with high reliability and precision.

Fig. 4.

AUC-ROC curves for healthy (red) and cancerous (black) image classification in the diagnosis of ALL using the Talqani Hospital Dataset.

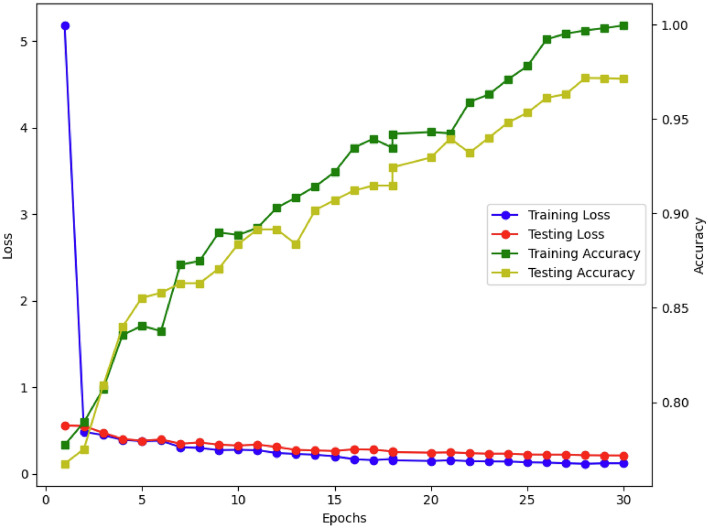

The results in Table 4, combined with the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves shown in Fig. 4, clearly illustrate the potential of the proposed model as a robust and efficient diagnostic tool for ALL. The training and testing performance curves, as depicted in Fig. 9, further reinforce this by demonstrating the model’s stable convergence, minimal overfitting, and strong classification ability. The ROC curves, representing the classification performance for healthy and cancerous images, demonstrate the model’s strong ability to distinguish between the two classes, with high true positive rates significantly outperforming the random baseline. These findings highlight the model’s capability to meet the stringent demands of clinical settings with high reliability and precision (Fig. 5).

Fig. 9.

Performance evaluation of the proposed model on the Multi-Cancer dataset over 30 epochs. The training loss (black) rapidly decreases, while the testing loss (red) remains stable at a low value, demonstrating effective learning and generalization. The training accuracy (green) shows a continuous upward trend, approaching 100%, while the testing accuracy (yellow) improves consistently, stabilizing above 95%. These trends indicate the model’s robustness in classifying ALL with high precision and reliability.

Fig. 5.

Performance evaluation of the proposed model on the Taleqani Hospital dataset over 30 epochs. The training loss (black) decreases rapidly, while the testing loss (red) remains stable, indicating effective generalization. The training accuracy (green) and testing accuracy (yellow) show consistent improvement, with testing accuracy reaching 96%.

Case study: C-NMC-19 dataset

The table 5 provides the performance evaluation of different deep learning models for diagnosing ALL using the C-NMC-19 dataset. The VGG-19 model delivered an accuracy of 87.3%, with a Precision of 87.54% and Recall of 87.3%. The F1-Score of 86.92% highlights a relatively balanced performance. The AUC value of 88.02% and mAP of 87.11% indicate strong predictive capability. However, the computational time of 1294.82 seconds makes it the least efficient model, suggesting that it may not be optimal for time-sensitive applications.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of different models for ALL diagnosis on the C-NMC-19 dataset (Total images: 4137).

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | AUC (%) | mAP (%) | Computational time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG-19 | 87.30 | 87.54 | 87.30 | 86.92 | 88.02 | 87.11 | 1294.82 |

| InceptionResNetV2 | 65.01 | 61.17 | 65.01 | 64.34 | 65.11 | 65.77 | 1081.24 |

| ResNet50 | 86.09 | 87.76 | 86.09 | 85.21 | 86.40 | 86.33 | 1091.64 |

| DenseNet50 | 85.11 | 82.56 | 86.42 | 82.05 | 83.96 | 86.33 | 1129.39 |

| AlexNet | 85.32 | 85.37 | 85.32 | 84.90 | 83.17 | 86.44 | 1098.39 |

| Our proposed | 97.13 | 99.32 | 92.42 | 95.75 | 96.04 | 94.45 | 882.88 |

InceptionResNetV2 showed a significantly lower performance, with an accuracy of 65.01%, a Precision of 61.17%, and a Recall of 65.01%. Its F1-Score of 64.34%, AUC of 65.11%, and mAP of 65.77% suggest limited effectiveness in handling this dataset. Although it required less computational time than VGG-19, taking 1081.24 seconds, its lower performance metrics indicate it is less suitable for the given diagnostic task.

ResNet50 demonstrated slightly better performance compared to VGG-19 in terms of Precision, achieving 87.76%, along with an accuracy of 86.09% and a Recall of 86.09%. Its F1-Score of 85.21%, AUC of 86.4%, and mAP of 86.33% indicate a strong ability to classify correctly. However, it required 1091.64 seconds of computational time, which, while better than VGG-19, remains resource-intensive.

DenseNet50 achieves an accuracy of 85.11%, with precision and recall values of 82.56% and 86.42%, respectively. The F1-Score of 82.05% reflects a slightly lower ability to balance predictions compared to ResNet50. The model attains an AUC score of 83.96% and an mAP score of 86.33%, showcasing moderate performance. However, DenseNet50 requires the highest computational time of 1,129.39 seconds, highlighting its inefficiency despite its reasonable performance metrics.

AlexNet achieves an accuracy of 85.32%, with precision and recall of 85.37% and 85.32%, respectively, leading to an F1-Score of 84.90%. The AUC score of 83.17% is similar to that of DenseNet50, while the mAP score of 86.44% demonstrates its moderate effectiveness in classification tasks. Its computational time of 1,098.39 seconds is slightly lower than DenseNet50 but remains higher than ResNet50.

The proposed model outperformed all the benchmark models across all performance metrics. It achieved the highest accuracy of 97.13%, with a Precision of 99.32% and a Recall of 92.42%, resulting in a robust F1-Score of 95.75%. Its AUC value of 96.04% and mAP of 94.45% highlight its superior ability to differentiate between classes accurately. Additionally, the computational time of 882.88 seconds is the lowest among the models, demonstrating remarkable efficiency. These results, along with Figs. 6 and 7, underscore the proposed model’s potential to be an exceptional tool for ALL diagnosis on the C-NMC-19 dataset, combining high accuracy with computational efficiency.

Fig. 6.

AUC-ROC curves for healthy (orange) and cancerous (black) image classification in the diagnosis of ALL using the C-NMC-19 Dataset.

Fig. 7.

Performance evaluation of the proposed model on the C-NMC-19 dataset over 30 epochs. The training loss (black) rapidly decreases, while the testing loss (red) remains stable at a low value, indicating effective generalization. The training accuracy (green) steadily increases, nearing 100%, while the testing accuracy (yellow) also improves consistently, stabilizing above 97%. These trends highlight the model’s strong learning capability and robust classification performance for ALL detection using the C-NMC-19 dataset.

Case study: multi cancer dataset

The table 6 presents the performance evaluation of various DL models for ALL diagnosis using the Multi Cancer Dataset. The VGG-19 model achieved an accuracy of 82.21% with a Precision of 83.91% and Recall of 82.32%. The F1-Score of 87.89% reflects a balanced performance, supported by an AUC of 84.41% and an mAP of 81.92%. However, its computational time of 1035.31 seconds indicates moderate efficiency compared to the other models.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of different models for ALL diagnosis on the Multi cancer dataset (total images: 10000).

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | AUC (%) | mAP (%) | Computational time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG-19 | 82.21 | 83.91 | 82.32 | 87.89 | 84.41 | 81.92 | 1035.31 |

| InceptionResNetV2 | 79.56 | 80.43 | 79.34 | 80.91 | 79.02 | 79.41 | 1021.03 |

| ResNet50 | 85.78 | 84.69 | 85.54 | 83.22 | 85.83 | 84.77 | 1231.11 |

| DenseNet50 | 85.78 | 84.69 | 83.74 | 81.32 | 84.13 | 84.17 | 1301.23 |

| AlexNet | 83.18 | 84.19 | 82.34 | 83.22 | 83.17 | 84.17 | 1251.23 |

| Our proposed | 95.86 | 96.11 | 95.61 | 95.82 | 96.72 | 96.23 | 912.13 |

InceptionResNetV2 showed a relatively lower performance with an accuracy of 79.56%, Precision of 80.43%, and Recall of 79.34%. Its F1-Score stood at 80.91%, with an AUC of 79.02% and an mAP of 79.41%. While its computational time of 1021.03 seconds is lower than VGG-19, its overall performance metrics are comparatively less favorable.

ResNet50 demonstrated improved accuracy at 85.78%, along with a Precision of 84.69% and Recall of 85.54%. Its F1-Score of 83.22% and AUC of 85.83% highlight its capability in classification tasks, supported by an mAP of 84.77%. However, the computational time of 1231.11 seconds, the highest among the models, reflects a significant trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

DenseNet50 matches ResNet50 in accuracy at 85.78%, with a precision of 84.69% and a recall of 83.74%. The F1-Score of 81.32% and AUC score of 84.13% are slightly lower than ResNet50, while the mAP score of 84.17% reflects moderate overall performance. However, DenseNet50 requires 1,301.23 seconds for processing, the highest among all models, indicating significant computational inefficiency.

AlexNet achieves an accuracy of 83.18%, with a precision of 84.19% and a recall of 82.34%. This results in an F1-Score of 83.22%. Its AUC score of 83.17% is comparable to DenseNet50, while its mAP score of 84.17% demonstrates moderate effectiveness in classification tasks. However, AlexNet’s computational time of 1,251.23 seconds is among the highest, highlighting its inefficiency for large-scale diagnostic applications.

The proposed model exhibited outstanding performance, surpassing all other models across all evaluation metrics. It achieved an accuracy of 95.86%, Precision of 96.11%, and Recall of 95.61%, leading to a highly balanced F1-Score of 95.82%. The AUC of 96.72% and mAP of 96.23% indicate exceptional class discrimination and prediction capability. Additionally, the computational time of only 912.13 seconds demonstrates its superior efficiency, making it suitable for practical clinical applications. This result, along with Figs. 8 and 9, positions the proposed model as not only the most accurate but also the most efficient, showcasing its potential as an excellent diagnostic tool for ALL detection using the Multi-Cancer dataset.

Fig. 8.

AUC-ROC curves for healthy (orange) and cancerous (black) image classification in the diagnosis of ALL using the multi cancer dataset.

The improved performance of our proposed model, based on EfficientNet-B7, across all three datasets (Talqani Hospital dataset, C-NMC-19 dataset, and Multi-Cancer dataset) can be attributed to its architectural efficiency, superior feature extraction capabilities, and optimized computational design. EfficientNet-B7 employs a compound scaling technique that balances network depth, width, and resolution to maximize feature extraction while minimizing computational costs. This scalability allows the model to capture fine-grained details crucial for microscopic image classification tasks. Unlike models such as VGG-19, which rely on fixed architectures, EfficientNet-B7 dynamically adjusts its design to ensure efficient feature utilization, explaining the consistently higher accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores achieved compared to other models.

EfficientNet-B7 utilising depthwise separable convolutions and squeeze-and-excitation blocks, which enhance its ability to focus on the most relevant features within ALL images. This attention mechanism gives it a distinct advantage over architectures like ResNet50 and DenseNet50, which lack explicit feature recalibration techniques. The improved AUC scores achieved by our proposed model across datasets highlight its ability to effectively distinguish between diagnostic labels (Healthy and ALL). Additionally, the proposed model demonstrates remarkable generalization across datasets of varying sizes and complexities, consistently outperforming benchmark architectures. While models such as InceptionResNetV2 and AlexNet show limited generalization, evidenced by their lower accuracy and AUC scores, EfficientNet-B7 maintains robust performance, showcasing its adaptability to diverse data distributions, a critical factor in medical diagnostics.

Our model achieves superior performance while being computationally efficient, with significantly lower computational times compared to DenseNet50, ResNet50, and AlexNet. This efficiency is due to its optimized architecture, which reduces redundant computations and using lightweight operations like depthwise separable convolutions. For instance, on the Talqani Hospital dataset, the proposed model processes images in just 59.28 seconds, compared to 129.27 seconds for DenseNet50 and 121.33 seconds for AlexNet, making it highly suitable for real-time applications in clinical settings. Furthermore, the consistently high mAP scores across datasets, such as 99.56% on the Talqani Hospital dataset and 96.23% on the Multi-Cancer dataset, highlight the model’s effectiveness in capturing both localization and classification accuracy. The F1-scores, which balance precision and recall, are also consistently higher, indicating the model’s ability to handle imbalanced datasets effectively. In contrast, baseline models such as InceptionResNetV2 exhibit significant challenges with imbalanced data, resulting in lower F1-scores.

Prediction explanation

XAI approaches namely Grad-CAM, CAM, LIME and IG were applied to the proposed model to explain the predictive decision and enhance the trust of medical professionals and patients. Comparative visualization with the original image of the mentioned techniques is illustrated in Figs. 10, 11 and 12.

Fig. 10.

Performance comparison of XAI techniques on the C-NMC-19 dataset for ALL diagnosis. (A) Original image. (B) Grad-CAM (best performer) effectively highlights diagnostically relevant regions. (C) CAM (second-best) identifies key areas with slightly less precision. (D) LIME (moderate performance) highlights localized regions but lacks clarity. (E) IG (weak performer) provides dispersed and less relevant explanations. This demonstrates the superiority of Grad-CAM for reliable explainability.

Fig. 11.

Performance comparison of XAI methods on the Taleqani Hospital dataset for ALL diagnosis. (F) Original image. (G) Grad-CAM (best performer) effectively highlights diagnostically significant regions with high clarity. (H) CAM (second-best) identifies relevant areas but with slightly reduced focus compared to Grad-CAM. (I) LIME (moderate performance) localizes some important regions but lacks precision. (J) IG (weak performer) provides dispersed and less informative explanations. This comparison underscores the reliability and superior explainability of Grad-CAM in this dataset.

Fig. 12.

Performance comparison of XAI approaches on the Multi-Cancer dataset for ALL diagnosis. (K) Original image. (L) Grad-CAM (best performer) highlights diagnostically important regions with superior clarity and focus. (M) CAM (second-best) identifies relevant regions, though with slightly less precision than Grad-CAM. (N) LIME (moderate performance) captures some critical areas but exhibits lower accuracy. (O) IG (weak performer) provides dispersed and less relevant explanations, making it the least reliable method. This comparison demonstrates the consistent superiority of Grad-CAM across datasets.

The Grad-CAM generated heatmaps in Figs. 10B, 11G and 12L, which offered a visual representation of the areas within the original ALL image that contribute most to the model’s prediction. The process involves the extraction of gradient values from the last convolutional layer (top_actovation) concerning ALL cancer, which indicates the non-functional white cells in the Leukaemia imagery. According to heatmap (B) in Fig. 10, the red area indicates the highest contribution, whereas the areas in black contribute the least. Similarly, the heatmap (G) shown in the Fig. 11 and (L) shown in Fig. 12 illustrates that the areas marked in white are the highest contributors to the model’s decision making process, whereas areas in other colors contribute less significantly.

The Class Activation Maps (CAM) shown in Figs. 10C, 11H, and 12M visually highlight the regions within the original ALL images that are most relevant to the model’s predictions. CAM works by utilizing the weighted activations of the final convolutional layer, mapping these activations back to the input space to identify areas of high importance for specific class predictions.

In the process, the feature maps are scaled by their associated weights from the fully connected layer, emphasizing the regions most associated with the model’s classification of ALL cancer. The heatmap in Fig. 10C demonstrates that the red regions signify the highest relevance to the prediction, while the black regions are less impactful. Similarly, the heatmaps in Figs. 11H and 12M indicate that white areas contribute the most to the decision-making process, whereas other colors signify regions with lower relevance. These CAM heatmaps offer valuable insights into the spatial features that the model relies on, thereby enhancing interpretability and supporting clinical decision-making in diagnosing ALL cancer.

In the LIME explanation Figs. 10D, 11I and 12N, the yellow areas are identified as key influencers in steering the model’s decision. LIME provided an explanation based on the perturbation of the input ALL image and observed the effect on the output.LIME was initially utilized to explain the Inception-V3 by4; however, it has shown enhanced effectiveness with the EfficientNet-B7.

In Figs. 10E, 11J, and 12O, the regions highlighted in green represent positive contributions to the model’s prediction, as determined by the Integrated Gradients (IG) method. IG works by computing the path integral of gradients along a straight-line path from a baseline input, such as a black image, to the actual input. This approach quantifies the contribution of each feature by accumulating gradients over the interpolation path, providing a clear attribution of the input features.

The visualizations generated by Grad-CAM, CAM, LIME, and IG were cross-verified against the ground truth provided in the dataset to evaluate their accuracy and reliability in identifying critical regions influencing the model’s predictions for ALL diagnosis. The results highlight varying degrees of effectiveness among these XAI methods in capturing relevant areas within the images.

Grad-CAM demonstrated the most accurate performance, effectively highlighting the critical regions when compared to the original image. Its ability to focus on the most relevant areas, particularly the non-functional white cells indicative of ALL, reinforces its reliability as an interpretability method. This alignment with the ground truth makes Grad-CAM a highly dependable tool for understanding the decision-making process of DL models.

CAM, while capturing the primary regions of interest, also included irrelevant areas in the prediction. Although it correctly identified the target cells, the inclusion of additional, less relevant cells reduced its precision compared to Grad-CAM. This highlights a potential limitation of CAM in distinguishing between the most and least relevant features within the complex cellular structures of ALL images.

LIME, on the other hand, struggled to maintain consistency with the ground truth. While it identified some relevant regions, it missed important features that were crucial for accurate predictions and, at the same time, included irrelevant areas. This inconsistency in capturing essential visual cues indicates that LIME may not be well-suited for tasks requiring high precision in localizing biologically significant features.

IG performed the weakest among the methods, failing to effectively capture the complex decision-making architecture of the model. Its inability to align with the ground truth highlights its limitations in interpreting intricate patterns in DL models, particularly for tasks with high architectural complexity, such as ALL diagnosis.

In summary, the results demonstrate that Grad-CAM provides the most reliable and accurate visual explanations for model predictions, closely matching the ground truth. CAM offers reasonable explanations but lacks the precision of Grad-CAM, while LIME and Integrated Gradients fall short in capturing the relevant features necessary for accurate explainability. This cross-validation emphasizes the importance of selecting appropriate XAI methods based on the task and complexity of the underlying model.

Conclusion, limitations and future research directions

In this study, we have effectively demonstrated the integration of EfficientNet-B7 with XAI methods across three datasets-Taleqani Hospital, C-NMC-19, and the Multi Cancer dataset-to enhance the diagnosis process and provide explainable model decisions through Grad-CAM, CAM, LIME, and IG for ALL. The incorporation of comprehensive evaluation metrics, namely AUC, mAP, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score, further validated the efficacy and reliability of our proposed framework presented in Tables 4, 5, and 6. These results establish a new benchmark for AI-driven diagnostics in ALL diagnosis, emphasizing both performance and explainability.

The necessity of this study stems from the critical demand for diagnostic frameworks that balance computational efficiency and explainability, particularly in time-sensitive medical scenarios. Our experimental results highlight the superiority of the proposed framework in achieving significantly lower computational times across all three datasets compared to benchmark models such as VGG-19, InceptionResNetV2, ResNet50, DenseNet50 and AlexNet, ensuring timely diagnosis without compromising accuracy. Additionally, the explainability offered by the integrated XAI methods promotes trust and transparency, addressing a key challenge in the adoption of AI systems in clinical settings.

However, certain limitations of the proposed framework warrant further investigation. First, while our framework achieves superior diagnostic accuracy and computational efficiency, its performance has been validated only on haematological (Microscopic images) datasets. Extending its applicability to other medical imaging domains and diseases will be crucial to generalize its utility. Second, the integration of multiple XAI methods, though beneficial for explainability, may introduce computational overhead that requires optimization in real-time clinical environments. Third, the reliance on labelled datasets poses challenges in scalability for regions with limited access to annotated medical data. Lastly, the smaller size of certain datasets could increase the risk of overfitting, despite mitigation strategies such as data augmentation and regularization.

Conclusively, this work not only proposed a novel framework for the diagnosis of ALL but also paved the way for future advancements in AI applications for medical diagnostics. By balancing computational efficiency with the imperative for explainability, clarity, and trust, this study sets a precedent for the integration of AI in healthcare. The results underscore the transformative potential of combining advanced DL architectures with XAI techniques to bridge the gap between technical performance and clinical applicability.

In future, we aim to explore additional architectures (Randomised and Spiking Neural network) and XAI methodologies to extend this framework to a broader spectrum of haematological diseases. Furthermore, we plan to address the scalability challenge by utilising semi-supervised and unsupervised learning techniques, enabling the framework to adapt to limited labelled data scenarios. Optimizing the computational overhead introduced by XAI methods will also be a priority to ensure real-time applicability in clinical settings. These directions will further enhance the diagnostic process, ensuring robust, explainable, and efficient solutions for diverse clinical challenges.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Science Foundation Ireland under grant numbers 18/CRT/6223 (SFI Centre for Research Training in Artificial Intelligence), 13/RC/2106/ (ADAPT Centre),13/RC/2094/

(ADAPT Centre),13/RC/2094/ (Lero Centre) and College of Science and Enginnering, UOG. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

(Lero Centre) and College of Science and Enginnering, UOG. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, D.M, M. S, M.B.; methodology, D.M, M.S; software, D.M, M.S; validation, D.M ,A,K,M.B; formal analysis,D.M, M.S; investigation, D.M, M.B; resources, D.M, M.B, data curation, D.M,M.B, writing- original draft preparation, D.M, M.S, ; writing-review and editing, D.M, A,K,M.B; visualization, D.M., supervision M.B; project administration, M.B; funding acquisition, D.M, M.B; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available: Mourya, S., Kant, S., Kumar, P., Gupta, A., & Gupta, R. ALL Challenge dataset of ISBI 2019 (C-NMC 2019). The Cancer Imaging Archive, DOI: 10.7937/tcia.2019.dc64i46r (2019). https://doi.org/10.7937/tcia.2019.dc64i46r. Aria, M. et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) image dataset. https://www.kaggle.com, DOI: 10.34740/KAGGLE/DSV/2175623 (2021). O. S. Multi Cancer dataset. Data set, DOI: 10.34740/KAGGLE/DSV/3415848 (2022).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

-

1.Gocher, A. M., Workman, C. J. & Vignali, D. A. Interferon-

: teammate or opponent in the tumour microenvironment?. Nature Reviews Immunology22, 158–172 (2022).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

: teammate or opponent in the tumour microenvironment?. Nature Reviews Immunology22, 158–172 (2022).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 2.Mondal, C. et al. Ensemble of convolutional neural networks to diagnose acute lymphoblastic leukemia from microscopic images. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked27, 100794 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghaderzadeh, M. et al. A fast and efficient cnn model for b-all diagnosis and its subtypes classification using peripheral blood smear images. International Journal of Intelligent Systems37, 5113–5133 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abir, W. H. et al. Explainable ai in diagnosing and anticipating leukemia using transfer learning method. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2022 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 5.Amin, M. M., Kermani, S., Talebi, A. & Oghli, M. G. Recognition of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in microscopic images using k-means clustering and support vector machine classifier. Journal of medical signals and sensors5, 49 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasani, P. H., Park, S.-W. & Jang, J.-W. An aggregated-based deep learning method for leukemic b-lymphoblast classification. Diagnostics10, 1064 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhammad, D., Ahmed, I., Ahmad, M. O. & Bendechache, M. Randomized explainable machine learning models for efficient medical diagnosis. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 1–10, 10.1109/JBHI.2024.3491593 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ali, M., Muhammad, D., Khalaf, O. I. & Habib, R. Optimizing mobile cloud computing: A comparative analysis and innovative cost-efficient partitioning model. SN Computer Science6, 1–25 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasir, S., Khan, R. A. & Bai, S. Ethical framework for harnessing the power of ai in healthcare and beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.00064 (2023).

- 10.Muhammad, D. & Bendechache, M. Unveiling the black box: A systematic review of explainable artificial intelligence in medical image analysis. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal24, 542–560. 10.1016/j.csbj.2024.08.005 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kellener, E. et al. Utilizing segment anything model for assessing localization of grad-cam in medical imaging. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.15692 (2023).

- 12.Zhou, B., Khosla, A., Lapedriza, A., Oliva, A. & Torralba, A. Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2016).

- 13.Shin, J. Feasibility of local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (lime) algorithm as an effective and interpretable feature selection method: comparative fnirs study. Biomedical Engineering Letters 1–15 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Sundararajan, M., Taly, A. & Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In International conference on machine learning, 3319–3328 (PMLR, 2017).

- 15.Khandekar, R., Shastry, P., Jaishankar, S., Faust, O. & Sampathila, N. Automated blast cell detection for acute lymphoblastic leukemia diagnosis. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control68, 102690 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abd El-Ghany, S., Elmogy, M. & El-Aziz, A. A. Computer-aided diagnosis system for blood diseases using efficientnet-b3 based on a dynamic learning algorithm. Diagnostics13, 404 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, Y. & Long, F. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells image analysis with deep bagging ensemble learning. In ISBI 2019 C-NMC Challenge: Classification in Cancer Cell Imaging: Select Proceedings, 113–121 (Springer, 2019).

- 18.Uysal, I. & Kose, U. Development of a simulation environment for the importance of histone deacetylase in childhood acute leukemia with explainable artificial intelligence. BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience 14, 254–286 (2023).

- 19.Jiang, Z., Dong, Z., Wang, L. & Jiang, W. Method for diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia based on vit-cnn ensemble model. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2021 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cui, W. et al. Deep multiview module adaption transfer network for subject-specific eeg recognition. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Li, Y. et al. Spatio-temporal-spectral hierarchical graph convolutional network with semisupervised active learning for patient-specific seizure prediction. IEEE transactions on cybernetics52, 12189–12204 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, X., Huang, H. & Xiang, J. A personalized diagnosis method to detect faults in gears using numerical simulation and extreme learning machine. Knowledge-Based Systems195, 105653 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, S. & Xiang, J. A minimum entropy deconvolution-enhanced convolutional neural networks for fault diagnosis of axial piston pumps. Soft Computing24, 2983–2997 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fei, X., Wang, J., Ying, S., Hu, Z. & Shi, J. Projective parameter transfer based sparse multiple empirical kernel learning machine for diagnosis of brain disease. Neurocomputing413, 271–283 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bilal, O. et al. Differential evolution optimization based ensemble framework for accurate cervical cancer diagnosis. Applied Soft Computing167, 112366 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asif, S. et al. A deep ensemble learning framework for covid-19 detection in chest x-ray images. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics13, 30 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mourya, S., Kant, S., Kumar, P., Gupta, A. & Gupta, R. ALL Challenge dataset of ISBI 2019 (C-NMC 2019). The Cancer Imaging Archive, 10.7937/tcia.2019.dc64i46r (2019). 10.7937/tcia.2019.dc64i46r. [DOI]

- 28.Dabass, M., Dabass, J., Vashisth, S. & Vig, R. A hybrid u-net model with attention and advanced convolutional learning modules for simultaneous gland segmentation and cancer grade prediction in colorectal histopathological images. Intelligence-Based Medicine7, 100094 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aria, M. et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (all) image dataset. https://www.kaggle.com, 10.34740/KAGGLE/DSV/2175623 (2021).

- 30.Naren, O. S. Multi cancer dataset. Data set, 10.34740/KAGGLE/DSV/3415848 (2022).

- 31.Ghosh, S., Das, N. & Nasipuri, M. Reshaping inputs for convolutional neural network: Some common and uncommon methods. Pattern Recognition93, 79–94 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan, M. & Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Chaudhuri, K. & Salakhutdinov, R. (eds.) Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 97 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

- 33.Ghosh, A., Soni, B. & Baruah, U. Transfer learning-based deep feature extraction framework using fine-tuned efficientnet b7 for multiclass brain tumor classification. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 1–22 (2023).