Abstract

Individuals with spinal cord injury/disease (SCI/D) have a high incidence of urinary tract infections (UTI). This randomized controlled pilot trial investigated the effect of an immunomodulator (Uro-Vaxom) versus a placebo on the urinary tract microbiome of individuals with SCI/D to inform the design of a larger trial. Twenty participants with SCI/D undergoing primary rehabilitation were randomized to receive either Uro-Vaxom or a placebo for three months (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04049994 08/08/2019). Urine was collected at baseline, immediately post-treatment, and three months post-treatment. DNA was extracted and sequenced using full-length 16 S rRNA using Oxford Nanopore technology. Internal controls were added for absolute abundance estimation. There were 10 participants in Uro-Vaxom and 10 in placebo analyzed. The prevalence of Escherichia coli was lower in the Uro-Vaxom group (2/10) compared to the placebo group (5/10) post-treatment, although this difference was not statistically significant. Significant alpha and beta diversity differences were associated with the microbial load, sex, and voiding method. Uro-Vaxom showed potential in reducing E. coli prevalence during the treatment period, but this result requires validation in a larger trial. Future trials should consider the baseline microbial load and optimal timing of intervention to ensure that the observed effects are attributable to immunomodulation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-96939-y.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Uro-Vaxom, Full length 16S rRNA, Immunomodulation, Urinary tract infections

Subject terms: Urinary tract infection, Metagenomics

Introduction

Individuals with spinal cord injury or disease (SCI/D) are highly susceptible to urinary tract infections (UTIs) and have a high prevalence of bacteriuria, which is defined as the presence of bacteria in the urine without clinical symptoms1–3. Although bacteriuria does not always lead to UTIs, it considerably increases the risk, especially in the SCI/D population. The use of catheterization for bladder management further elevates the risk of introducing external microorganisms into the urinary tract, thereby increasing the likelihood of both bacteriuria and UTIs2–4. Moreover, individuals with SCI/D are prone to infections because of compromised immune system5. The frequent recurrence of UTIs in this population necessitates multiple courses of antimicrobial treatment, raising major concerns regarding the development of antimicrobial resistance. Given these challenges, there is a pressing need for alternative preventive and management strategies for UTIs in individuals with SCI/D.

One proposed approach to UTI prevention is immunomodulation. Uro-Vaxom is a commercially available immunomodulator that contains lyophilized lysate of 18 E. coli strains6,7. The mechanism of action of Uro-Vaxom involves stimulation of innate and adaptive immune responses. When administered orally, it activates dendritic cells and macrophages in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines8. This activation triggers a cascade of immune responses, including the enhancement of natural killer cell activity and the stimulation of B-lymphocytes to produce specific antibodies against E. coli strains8. Furthermore, Uro-Vaxom has been shown to increase the secretion of mucosal IgA in the urinary tract, providing a local defensive barrier against bacterial adherence and invasion9. This multifaceted immune stimulation is particularly relevant for individuals with SCI/D, who often have compromised immune function and altered urinary tract physiology. Targeting E. coli through immunomodulation is a logical approach, as it is the predominant causative agent of UTIs in SCI/D3. In a retrospective cohort study on Uro-Vaxom, results showed a significant and clinically relevant decrease in the frequency of UTIs in patients with SCI7, although no new randomized controlled trial has been published to date. By potentially reducing the microbial load and prevalence of E. coli in the urinary tract, Uro-Vaxom may offer a non-antimicrobial strategy to prevent UTIs and reduce the need for frequent antimicrobial use in this vulnerable population.

This study aimed to investigate the effect of immunomodulation using Uro-Vaxom versus a placebo on the urinary tract microbiome in individuals with SCI/D. By examining the changes in microbial composition and abundance, we sought to elucidate the potential mechanisms by which Uro-Vaxom may prevent UTIs in this vulnerable population. Additionally, we aimed to assess the feasibility of using full-length 16 S rRNA sequencing to characterize the urinary microbiome in patients with SCI/D. The insights gained from this pilot study will inform the design of a larger and more comprehensive trial on UTI prevention in the SCI/D population, potentially leading to improved management strategies and reduced antimicrobial use.

Results

Participants’ demographics

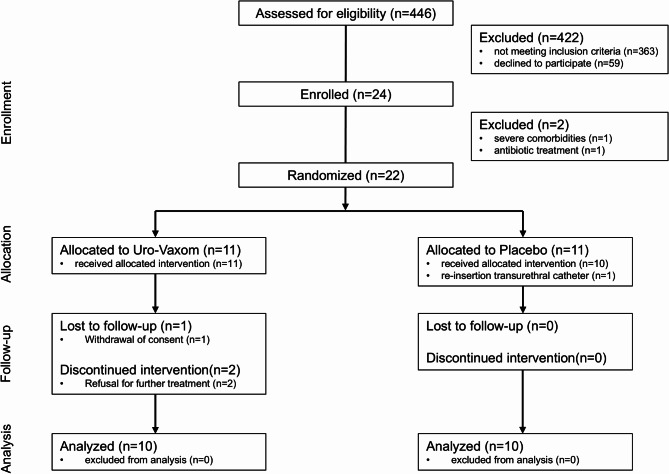

Participant recruitment and enrolment details are shown in Fig. 1. Recruitment was conducted from January 2020 to February 2022 at Swiss Paraplegic Research in Nottwil, Switzerland. The trial enrolled 24 participants, of which 22 were randomized, and 20 completed the trial. The demographic characteristics demographics of the evaluated 20 participants are presented in Table 1. The main results (feasibility outcomes and incidence of UTIs) of the pilot trial are presented in another publication10.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the Uro-Vaxom pilot as per consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) 2010 guidelines.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of individuals with SCI whothat completed the Uro-Vaxom pilot study.

| Variables | Categories | Uro-Vaxom (n = 10) | Placebo (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.5 ± 14.0 | 41.2 ± 12.3 | |

| Duration SCI/D (days) | 43.7 ± 7.1 | 42.8 ± 11.4 | |

| Sex (n) | Females | 4 | 3 |

| Males | 6 | 7 | |

| Injury Severity (n) | C1-C4 AIS A-C | 1 | 1 |

| C5-C8 AIS A-C | 1 | 0 | |

| T1-S5 AIS A-C | 6 | 7 | |

| AIS D | 2 | 2 | |

| Etiology (n) | Traumatic | 8 | 9 |

| Non-traumatic | 2 | 1 | |

| Voiding method (n) | IC | 7 | 9 |

| Spontaneous | 3 | 1 |

Effect of immunomodulation on the urinary tract microbiome

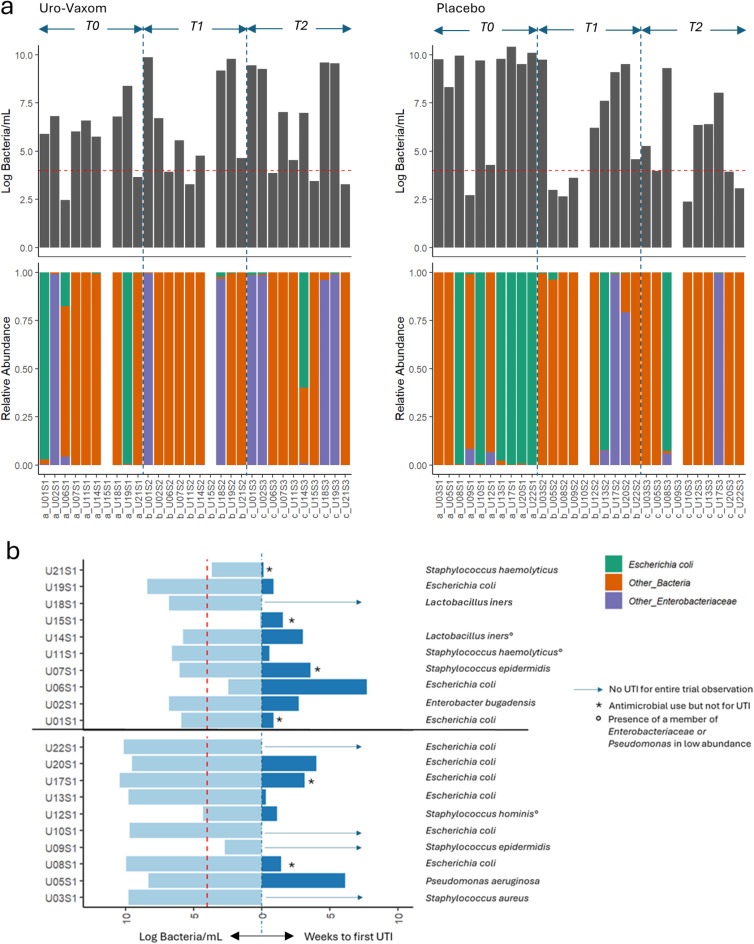

The effects of immunomodulation on the microbiome are summarized in Fig. 2a. There was no difference observed in the microbial composition within groups nor between groups at different timepoints. Likewise, there was no significant difference in microbial load before, after immunomodulation and 3-months after immunomodulation between groups (Uro-Vaxom vs. placebo) or within groups. Before immunomodulation, the prevalence of E. coli was 50% (5/10) in the Uro‑Vaxom group and 70% (7/10) in the placebo group. Following treatment, the prevalence was 20% (2/10) in the Uro‑Vaxom group and 50% (5/10) in the placebo group. At three months post‑immunomodulation, the prevalence was 40% (4/10) in the Uro‑Vaxom group and 20% (2/10) in the placebo group. No statistically significant differences were observed between or within groups over time. The time from baseline urine collection for microbiome analysis to the first UTI was recorded (Fig. 2b), but did not differ significantly between groups. Six (30%) of the 20 participants had used antimicrobials but not for UTI, 9/20 (45%) participants had their first UTI with a mean of 1.9 ± 2.2 weeks, and 5/20 (25%) did not developed an UTI in the entire 6-month trial run. Among those who developed UTI, 8/9 (88%) had high microbial load in baseline urine, 5/9 (56%) had a dominant Enterobacteriaceae at baseline, and 3/9 (33%) had either an Enterobacteriaceae or Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified in low abundance. Among the participants who did not develop UTI, 4/5 (80%) had a high microbial load at baseline and 2/5 (40%) had E.coli.

Fig. 2.

Summary of the microbial load and relative abundance profile of the urinary tract microbiome of individuals with SCI who participated in the pilot randomized control trial on Uro-Vaxom versus placebo (a) and the time in weeks to develop the first UTI among the trial participants with their baseline microbial load and dominant organisms in urine (b).

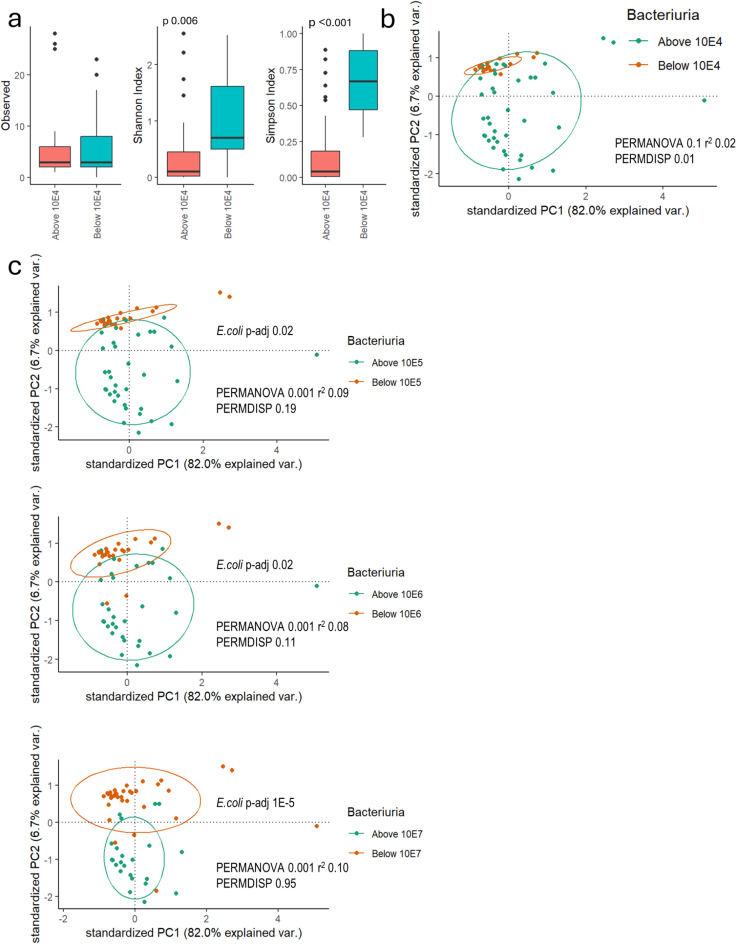

Low versus high microbial load microbiome characteristics

The estimated urine microbial load ranged from zero to 1010 bacteria/mL. The most prevalent species were E. coli (42%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (18%), Enterococcus faecalis (18%), Lactobacillus iners (18%) and L. crispatus (15%). Alpha diversity indices differed significantly between low and high microbial load samples (Fig. 3a). There was significant beta diversity difference (PERMDISP 0.01) between low vs. high microbial load (Fig. 3b). The PERMANOVA showed significant differences between high and low microbial loads when the threshold was scaled up to > 104 bacteria/mL (Fig. 3b). E. coli abundance was significantly higher at higher microbial load thresholds compared to lower loads (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Alpha (a) and beta diversity (b) differences in microbial load in participants’ urine and the summary of the differences in the beta diversity and the differential abundance results for E. coli when the threshold for bacteriuria is scaled up by magnitude (c).

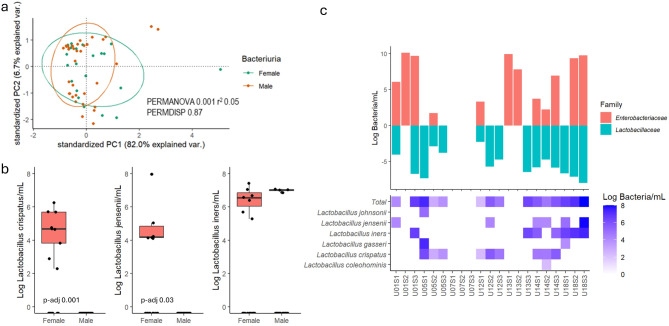

Difference in microbial composition and abundance between sexes

Urinary bacterial composition in women was significantly different (PERMANOVA p = 0.001) from that in male with SCI (Fig. 4a). Differential abundance analysis revealed sex-specific patterns with L. crispatus and L.jensenii significantly more abundant in females compared to males (Fig. 4b). L. iners was observed in four male urine samples in the presence of a dominant Enterobacteriaceae, and in 4/8 (50%) of female urine samples with high microbial load and a dominant Enterobacteriaceae. L. crispatus was exclusively present in females and was found in 8/13 (62%) female urine samples without Enterobacteriaceae and those with low microbial load (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Summary of the comparisons of the beta diversity between sexes (a), the differential abundance results of the three most prevalent Lactobacillus species identified between sexes (b), and the heat map of the log10 absolute abundance of the Lactobacillus species identified in relation to the presence of an Enterobacteriaceae (c).

Difference in microbial composition and abundance between voiding methods

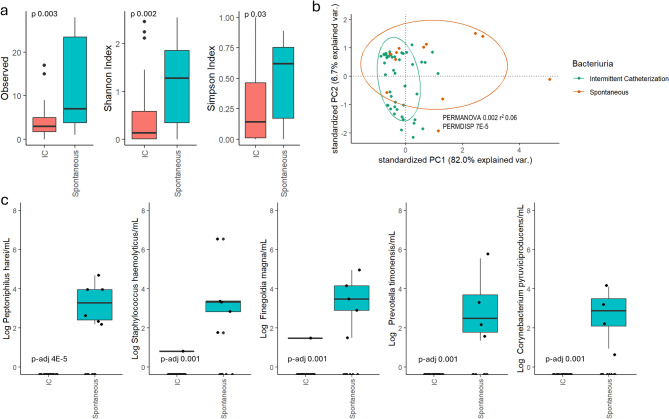

Significant differences in alpha diversity indices (observed [p = 0.003], Shannon [p = 0.002], Simpson [p = 0.03]; Fig. 5a) and beta diversity (PERMANOVA [p = 0.002], PERMDISP [p < 0.001]; Fig. 5b) were observed between voiding methods. The compositional difference between voiding methods was mainly driven by species from gram-positive anaerobic cocci genera (Peptoniphilus, Finegoldia and Anaerococcus), Staphylococcus, Prevotella and Corynebacterium, which were more abundant in urine from participants voiding spontaneously compared to those using IC. The five most prevalent and differentially abundant species among spontaneous voiders compared to IC users are summarized in Fig. 5c, with the full list provided in Supplementary Table 2. Notably, fecal bacteria were identified in 4/60 (7%) urine samples, evenly split between spontaneous voiders and IC users.

Fig. 5.

Summary of the alpha (a) and beta (b) diversity differences between voiding methods, with the most prevalent differentially abundant species (c).

Discussion

This pilot randomized controlled trial investigated the effects of Uro-Vaxom, an oral immunomodulator, on the urinary tract microbiome of patients with SCI/D. The prevalence of E. coli was lower in the Uro-Vaxom group compared to the placebo group after the 3-month immunomodulation period, although this difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, we observed significant differences in microbial diversity associated with microbial load, sex, and voiding method. E.coli was differentially abundant with low vs. high microbial load but at threshold set higher than 104 bacteria/mL. Differentially abundant species were likewise observed with sex and voiding method but does not include E. coli.

The immunomodulator did not influence the microbiome, although a lower prevalence of E. coli was observed post‑treatment; this difference was not statistically significant. Unlike antimicrobials, the immunomodulator act indirectly to prevent UTIs by enhancing the immune response and only to specific organisms, thus explaining the results. After oral administration of Uro-Vaxom, the initial presentation of E. coli lysates is with to the gut immune system and occurs in the gut, and the local E. coli population in the gut may be reduced with Uro-Vaxom use. This reduction leads to less E. coli in the perineum and adjacent skin, thus less likely to be introduced into the bladder. This idea needs to be tested but is supported by the presence of fecal bacteria in the urine as seen in this study and by the presence of fecal bacteria on the pelvic region skin of individuals with SCI11. For those who spontaneously void, the fecal bacteria indicated contamination during collection, while for those who used IC, the fecal bacteria represented the introduction of foreign organisms to the bladder. However, the decreased in prevalence of E. coli can also be explained by improved knowledge and self-management of urination, especially since the trial was conducted on their primary rehabilitation post-injury, considering that the prevalence of E. coli in placebo group also decreased.

We observed that having a high microbial load in the urine did not necessarily lead to a UTI, although the odds were especially high when the dominant organism belonged to an Enterobacteriaceae. This indicated that some organisms were well tolerated by the body and were probably non-pathogenic. Even among E. coli there were suspected non-pathogenic strains to the urinary tract and virulence of known uropathogens is hypothesized to be partly determined by the host12.

Studies of the urinary tract microbiome in patients with SCI are scarce, and comparisons based on specific population characteristics are lacking13. Our findings highlight the complex interplay among host factors, microbial communities, and UTI risk in individuals with SCI/D. The observed differences in microbial composition based on sex and voiding method underscore the importance of personalized approaches for UTI prevention in this population. Differences were observed in the urinary tract microbiomes between the sexes. L. crispatus and L.jensenii were more abundant in females. L. iners on the other hand was able to grow with Enterobacteriaceae in the urine of both sexes. The presence of Lactobacillus species in the urinary tract of males has been previously reported14. Lactobacillus species have been implicated in the development of bacterial vaginosis15. L. crispatus was associated with healthy vaginal microbiome while L. iners was associated with bacterial vaginosis. The vaginal microbiome is likely to influence the urinary tract microbiome because of the proximity of the vagina and the short urethra in females.

Likewise, the voiding method, whether urinating spontaneously or using catheters, influenced the bacteria detected in urine and was reflected in the diversity index differences. Spontaneously voided urine contained more and a diverse range of bacterial species. Collecting mid-stream urine in individuals with SCI is difficult and thus likely contaminated with the urethral microbiome and from the perineum and adjacent skin. Intact skin in the pelvic region mostly contains gram-positive anaerobic cocci, Staphylococcus, and Corynebacterium11. These organisms were differentially abundant in the urine collected via spontaneous voiding versus IC. The use of catheters in collecting urine reduces the risk of contamination from the urethra and, when done correctly, it represents the microbiome in the bladder16; however, when improperly done, it introduces external microorganisms into the bladder.

The results of our analysis of the Uro-Vaxom trial should be interpreted with caution and validated in larger, more diverse cohorts. The limited size of the study population and the pilot nature of the trial were not intended to test a hypothesis. However, the trial proved that that the use of full-length 16 S rRNA sequencing with an internal control could characterize the urinary tract microbiome in this population, provided estimates of their absolute abundance, and captured the differences in the microbiome based on sex, voiding method, and microbial load. Differences in sex and voiding method did not affect the abundance of E.coli. Differences in microbial load though need to be considered in the future trial designs. As seen at baseline, there were microbial load differences and known uropathogens were present which may be associated with the early occurrence of UTIs. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain whether the UTI or its prevention is attributable to the intervention being tested. A possible solution is to recruit from a pool of individuals who have recently undergone antimicrobial therapy for either for a urinary tract procedure or a UTI. Thus, the baseline urinary tract microbiome characteristics are more homogenous. Additionally, the timing of trial implementation—whether during primary rehabilitation or routine rehabilitation—affects the interpretation of outcomes by considering the time elapsed since injury and concurrent improvements in urinary tract management. Such factors may influence the effect attributed to immunomodulation. Both the immunomodulation and improved management of participants’ urination affected the introduction of organisms into the bladder. Therefore, this could result into a smaller observed effect size for immunomodulation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this pilot randomized controlled trial provides valuable insights into the effects of Uro-Vaxom on the urinary tract microbiome of individuals with SCI/D. Although the immunomodulator showed potential in reducing E. coli prevalence during the treatment period, these findings require validation in a larger trial. Our study demonstrates the feasibility and utility of full-length 16 S rRNA sequencing for characterizing the urinary microbiome in this population, revealing significant differences associated with microbial load, sex, and voiding methods.

Future trials should carefully consider the baseline microbial load and the optimal timing of intervention to ensure that the observed effects are truly attributable to immunomodulation. Additionally, the complex interactions among host factors, microbial communities, and UTI risk highlighted in this study suggest that personalized approaches to UTI prevention may be necessary for individuals with SCI/D.

Based on these findings, larger trials are needed to further elucidate the potential of immunomodulation as a non-antimicrobial strategy for UTI prevention in the SCI/D population. This approach may ultimately lead to reduced antimicrobial use and improved quality of life for individuals with SCI/D.

Methods

Participants recruitment and study design

This study was part of a pilot clinical trial on the effects of immunomodulation for the primary prevention of UTIs in patients with SCI/D during primary rehabilitation (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04049994; registered on 08/08/2019) and adhered to a previously published protocol11. The study complied to all the relevant guidelines and local regulations with the trial approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwestern and Central Switzerland (Project ID 2019 − 01768; final approval, 26 November 2019). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Randomization and blinding

Participants were randomly assigned to either the Uro-Vaxom or placebo groups using a 1:1 allocation ratio. Randomization was stratified according to sex to ensure balanced groups. Both the participants and investigators were blinded to the treatment allocation. Further details are provided in the protocol17.

Urine collection, DNA extraction and sequencing

Each participant provided 30 mL of urine at three time points: before the start of immunomodulation (T0), immediately after the completion of immunomodulation (T1) and three months post-immunomodulation (T2). Utilizing the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort (SwiSCI) biobank infrastructure, the urine processing and storage were conducted as described by Zeh et al.18. For deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis, 500 µL of thawed and suspended urine pellets were processed for DNA extraction using Fecal Power Amp Qiagen Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted DNA was eluted in 50 µL of buffer, and concentrations were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit and a Qubit 4.0 fluorimeter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Q33238) and stored at -20 °C. We then quantified the bacterial DNA in the extracted DNA by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and then we spiked the samples with an internal control (ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control I [High Microbial Load]) to a ratio of 9:1 bacterial DNA to spike to a total of 0.01 ng DNA template. Each sequencing batch included both a positive control (using an internal control) and a negative control (containing only distilled water). The detailed steps of the PCR conditions during sequencing have been previously described by Bertolo et al.19. Sequenced reads were classified using Emu20.

UTI diagnosis and management

Throughout the study period, UTIs were monitored every 2 weeks. A UTI event was defined as having at least one symptom, ≥ 100 leukocytes/mL in urine, and a positive urine culture (≥ 104 CFU/mL)11. When a UTI was suspected, the study physician evaluated the participant. If diagnosed, UTIs were managed according to standard clinical practice, which involved empirical antibiotic treatment based on local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, followed by targeted therapy based on urine culture results. The first UTI episode of the participants was recorded and the time elapse from baseline urine collection to the first UTI were noted.

Quantification of microbiome abundance

The microbiome profiles were normalized against the proportion of the internal controls, initial urine material, bacterial DNA concentration, dilutions and the number of the 16-subunit ribosome ribonucleic acid (16 S rRNA) gene copies per species. The median number of 16 S rRNA gene copies was sourced from the Ribosomal RNA Database of the Center for Microbial Systems at the University of Michigan21 and is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The microbiome data were analyzed using R (R Core Team, 2016, Vienna, Austria, version 4.2.2) and presented in their log10 estimates of absolute abundance. Classified reads with a relative abundance of 0.1% or higher were included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, and means with their standard deviations were reported. Urine samples were grouped by microbial load as either equal to or above (high microbial load) or below (low microbial load) the concentration of 104 bacteria/mL. Differences were further tested by moving the microbial load thresholds by a magnitude to check whether differences occurred at these levels. Dominant bacteria were defined as an organism with a magnitude higher abundance than the next organism in the urine. Alpha diversity was assessed using the observed taxa and Simpson and Shannon indices and compared using the Wilcoxon sum rank test. Beta diversity, a measure of assessing compositional differences, was assessed by generating dissimilarity matrices (Bray-Curtis) and then compared using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) and permutational multivariate analysis of dispersion (PERMDISP) and visualized by principal coordinate analysis (PCA). Differential abundance analysis was conducted using the Wilcoxon sum rank test, with the p-value adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg. Significant differences were accepted when the p-value or the adjusted p-value (p-adj) was at 0.05 or lower. Comparison between groups were conducted only when both groups have at least 5 samples.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement: We thank Ramona Schaniel, Nicole Nyfeler, Gion Fränkl for pre-processing the urine samples for storage. We thank Jasmine Mahler, Alexandra Widmer and the team at the CTU for participant recruitment and sample collection.

Author contributions

Author Contributions: EV had full access to all data in the study and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data in the study and accuracy of the analysis. Concept and design: JS, JK, JW, JP. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: EV, AB. Drafting of the manuscript: EV. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: EV, AB, JK, JW, JP, JS. Statistical analysis: EV. Supervision: JK, JS.

Funding

This project received funding from the Swiss Paraplegic Foundation. EV received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 801076, through the SSPH + Global PhD Fellowship Program in Public Health Sciences (GlobalP3HS) of the Swiss School of Public Health. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed in the current study are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository, BioProject ID: PRJNA1139160 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1139160).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jörg Krebs and Jivko Stoyanov contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Gao, Y., Danforth, T. & Ginsberg, D. A. Urologic management and complications in spinal cord injury patients: A 40- to 50-year Follow-up study. Urology104, 52–58 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shekelle, P. G., Morton, S. C., Clark, K. A., Pathak, M. & Vickrey, B. G. Systematic review of risk factors for urinary tract infection in adults with spinal cord dysfunction. J. Spinal Cord Med.22 (4), 258–272 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Togan, T., Azap, O. K., Durukan, E. & Arslan, H. The prevalence, etiologic agents and risk factors for urinary tract infection among spinal cord injury patients. Jundishapur J. Microbiol.7 (1), e8905 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krebs, J., Wollner, J. & Pannek, J. Risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infections in individuals with chronic neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Spinal Cord. 54 (9), 682–686 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valido, E. et al. Immune status of individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;24(22). (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Tammen, H. Immunobiotherapy with Uro-Vaxom in recurrent urinary tract infection. The German urinary tract infection study group. Br. J. Urol.65 (1), 6–9 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebs, J., Fleischli, S., Stoyanov, J. & Pannek, J. Effects of oral Immunomodulation therapy on urinary tract infections in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury-A retrospective cohort study. Neurourol. Urodyn.38 (1), 346–352 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer, H. W., Rahlfs, V. W., Lauener, P. A. & Blessmann, G. S. Prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections with immuno-active E. coli fractions: a meta-analysis of five placebo-controlled double-blind studies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 19 (6), 451–456 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naber, K. G., Cho, Y. H., Matsumoto, T. & Schaeffer, A. J. Immunoactive prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 33 (2), 111–119 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krebs, J. et al. Immunomodulation for primary prevention of urinary tract infections in patients with spinal cord injury or disease during primary in-house rehabilitation: results from a randomized placebo-controlled feasibility trial (UroVaxom-Pilot). Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wettstein, R. et al. Understanding the impact of spinal cord injury on the microbiota of healthy skin and pressure injuries. Sci. Rep.13 (1), 12540 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreiber HLt, Spaulding, C. N., Dodson, K. W., Livny, J. & Hultgren, S. J. One size doesn’t fit all: unraveling the diversity of factors and interactions that drive E. coli urovirulence. Ann. Transl Med.5 (2), 28 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valido, E. et al. Systematic review of the changes in the microbiome following spinal cord injury: animal and human evidence. Spinal Cord. 60 (4), 288–300 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth, R. S., Liden, M. & Huttner, A. The urobiome in men and women: a clinical review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.29 (10), 1242–1248 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter, K. A., Fischer, M. D., Petrova, M. I. & Balkus, J. E. Epidemiologic evidence on the role of Lactobacillus iners in sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis: A series of systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. Sex. Transm Dis.50 (4), 224–235 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karstens, L. et al. Community profiling of the urinary microbiota: considerations for low-biomass samples. Nat. Rev. Urol.15 (12), 735–749 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krebs, J., Stoyanov, J., Wollner, J., Valido, E. & Pannek, J. Immunomodulation for primary prevention of urinary tract infections in patients with spinal cord injury during primary rehabilitation: protocol for a randomized placebo-controlled pilot trial (UROVAXOM-pilot). Trials22 (1), 677 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeh, R. M. et al. The Swiss spinal cord injury cohort study (SwiSCI) biobank: from concept to reality. Spinal Cord. 62 (3), 117–124 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertolo, A., Valido, E. & Stoyanov, J. Optimized bacterial community characterization through full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing utilizing minion nanopore technology. BMC Microbiol.24 (1), 58 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curry, K. D. et al. Emu: species-level microbial community profiling of full-length 16S rRNA Oxford nanopore sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 19 (7), 845–853 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoddard, S. F., Smith, B. J., Hein, R., Roller, B. R. & Schmidt, T. M. RrnDB: improved tools for interpreting rRNA gene abundance in bacteria and archaea and a new foundation for future development. Nucleic Acids Res.43 (Database issue), D593–D598 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed in the current study are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository, BioProject ID: PRJNA1139160 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1139160).