Abstract

Splenic macrophage Fcγ receptors participate in the pathophysiology of immune cytopenias, and in such disorders, the beneficial effects of glucocorticoids are in part mediated by decreased expression of macrophage Fcγ receptors. In the animal model, progesterones, like glucocorticoids, inhibit expression of these receptors. Megestrol acetate (MA) is a progesterone frequently used for treating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated anorexia-cachexia. Twenty-eight patients with HIV-associated thrombocytopenia with shortened platelet survival and increased platelet-associated immunoglobulin G (IgG) who were being treated with MA for anorexia-cachexia were prospectively studied for a 6-month period to assess the potential role of progesterones in the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia. Treatment with MA for nonconsecutive periods of 2 months and 1 month significantly increased platelet count and platelet survival without significant alteration of platelet-associated immunoglobulin levels. Of the 28 patients studied, 22 presented a complete response, 19 presented a complete response 1 month after finishing the MA treatment regimen, and 12 remained in complete response for a further month. Expression of Fcγ receptors (FcγRI and FcγRII) by peripheral blood monocytes and the in vitro recognition of IgG-sensitized cells by monocytes were significantly decreased by the MA treatment. Decreased expression and functioning of these receptors significantly correlated with platelet counts and survival times, but no relationship was found with platelet-associated immunoglobulin, circulating immune complexes, body mass index, plasma HIV load, or CD4 lymphocyte levels. These results suggest that treatment with progesterones, like MA, may be an alternative therapy for immune cytopenias, with few side effects.

Preliminary data have suggested that treatment with megestrol acetate (MA) enhances the platelet count of malnourished patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated thrombocytopenia (21), most of whom present immunoglobulin G (IgG) antiplatelet antibodies (13, 27). Receptors for the Fc fragment of IgG (FcγRs) on macrophages play an important role in host defense against infection (10, 19), particularly in the pathophysiology of immune cytopenias (3, 5, 7, 8, 22, 23). Hence, regulation of the expression of these splenic receptors is an important target in the immunotherapeutic treatment of those disorders.

Glucocorticoid treatment is the standard therapy for immune cytopenias such as immune thrombocytopenic purpura and immune hemolytic anemia (1, 8), but its usefulness is limited by significant side effects. Glucocorticoids inhibit the expression of splenic macrophage Fcγ receptors and increase cell survival (6, 8, 22, 23). In an animal model (the guinea pig), progesterones have been shown to decrease the clearance of IgG-sensitized cells (11, 24) through their effect on the expression of these receptors. However, this effect of progesterone has not been reported before in humans.

MA is a progesterone already approved for the treatment of HIV-associated anorexia-cachexia (14, 25, 26) but not yet for thrombocytopenia. We have performed a prospective study of 28 patients presenting HIV-associated thrombocytopenia, with shortened platelet survival and elevated platelet-associated IgG, who were being treated with MA for anorexia-cachexia. The objective was to assess the role of MA in the specific treatment of HIV-associated thrombocytopenia by monitoring the platelet count and platelet survival and the surface expression and functioning of peripheral blood monocyte FcγRI and FcγRII.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

We prospectively studied patients with HIV-associated thrombocytopenia treated in the outpatient clinic of our hospital between January 1992 and December 1995. Data on 28 of these patients who were taking MA for anorexia-cachexia (4 females and 24 males; age, 29 ± 12 years) and who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and completed the 6-month follow-up period were analyzed (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristicsa

| Time of treatment | MA dose (mg/kg/day) | Response at end of mo (no. of patients)

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) | CD4 count (cells/μl) | HIV RNA load in plasma (RNA copies/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Partial | No response | |||||

| Before | 19 ± 3 | 252 ± 23 | 24,947 ± 1,201 | ||||

| Mo 1 | 640 | 15 | 8 | 5 | 19 ± 2 | ||

| Mo 2 | 826 ± 51 | 20 | 5 | 3 | 20 ± 3 | ||

| Mo 3 | None | 15 | 8 | 5 | 21 ± 5 | 242 ± 21 | 27,645 ± 2,471 |

| Mo 4 | 826 ± 51 | 22 | 3 | 3 | 21 ± 4 | ||

| Mo 5 | None | 19 | 6 | 3 | 22 ± 3 | ||

| Mo 6 | None | 12 | 8 | 8 | 22 ± 3 | 267 ± 19 | 27,273 ± 2,211 |

Twenty-eight patients (4 female, 24 male; mean age ± SEM, 29 ± 7 years) with HIV-associated thrombocytopenia, with shortened platelet survival and elevated platelet-associated IgG, treated with MA for anorexia-cachexia, participated in the study. The characteristics of patients on enrollment (before treatment), the dose of MA and the evolution of HIV infection during follow-up are shown. Results are expressed as means ± SEM. HIV-pVL = HIV-RNA load in plasma.

The patients eligible for this study were between 18 and 60 years old, with at least three platelet counts of less than 50,000/ml during the previous 6 months, shortened platelet survival, and elevated platelet-associated IgG levels. We excluded patients with renal disease (plasma creatinine ≥2 mg/dl), liver disease (prothrombin or prothrombin time below 80% of the levels of controls, serum albumin <3.5 mg/dl, or bilirubin ≥3 mg/dl), cirrhosis, ultrasonographic signs of portal hypertension, active infection, sepsis, neoplasia, and autoimmune disorders. Patients with an AIDS-defining event or those receiving immunosuppressive treatment during follow-up were also excluded. Patients gave informed consent before enrollment. The study was approved by the Ethic and Clinical Trials Committee of our university hospital.

The characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1. None of the patients were excluded because they developed an AIDS-defining event. Two patients were excluded because they failed to comply with MA treatment during the first month of treatment. These two patients were not considered for analysis because they generated no more data than the parameters before commencement of the treatment.

Seventeen patients acquired HIV infection by intravenous drug abuse (60.71%), 6 patients by heterosexual transmission (21.43%), and 5 patients by homosexual or bisexual practices (17.86%). Six patients were being treated with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase analogs (four with zidovudine [AZT] plus zalcitabine [DDC] and two with AZT plus didanosine [DDI]), and 22 patients were being treated with AZT monotherapy when this study commenced. No patients had received protease inhibitors, and all of them had detectable virus loads (200 HIV RNA copies/ml) in plasma on enrollment or during follow-up.

Treatment and response.

Oral treatment with MA, 320 mg twice per day for the first month, was increased to 320 mg three times per day during the second month if a complete response was not obtained at the end of the first month. MA was not administered during the third month after enrollment. During the fourth month, patients were again treated with MA at the same dose as that given during the second month. The MA was provided to patients on their weekly visits to the clinic, at which time the attending nurse applied a questionnaire to confirm that the patient had complied with the treatment regimen (Table 1).

An increase in the platelet count of ≥80,000/ml over the baseline value was taken as a complete response, an increase in the platelet count of >40,000/ml but ≤79,999/ml as a partial response, and an increase in the platelet count of ≤39,999/ml as no response.

Study protocol.

Complete blood count, the Westergren sedimentation rate, urinalysis, and renal and liver function tests were done on enrollment and monthly thereafter. Serologic tests for hepatitis B and C virus, syphilis, antinuclear antibodies, and bone marrow aspiration were performed on enrollment.

The number of CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes and the plasma HIV RNA load were determined on enrollment and after 3 and 6 months. CD4 and CD8 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, and the plasma HIV RNA load was determined using a commercial PCR technique (Amplicor, Roche Diagnostics, Madrid, Spain) in samples frozen at −70°C.

Platelet survival, platelet-associated immunoglobulin (IgG and IgM), and circulating immune complexes were measured both on enrollment and at the end of the second, fourth, and sixth months. Survival of autologous platelets was determined by 51Cr labeling and clearance, using the method for radioisotope platelet studies of the International Committee for Standardization in Hematology (15). Platelet survival is expressed as time (T 1/4) in minutes in which 20% of 51Cr-labeled autologous platelets are cleared. Platelet-associated IgG and IgM levels were determined by a commercial reference laboratory, based on radiolabeled monoclonal anti-IgG and anti-IgM antibodies (1). Results are expressed in femtomoles of IgG or IgM per platelet. Circulating immune complexes were determined by precipitation with polyethylene glycol (4).

The in vitro recognition of sheep IgG-sensitized red blood cells RBCs by peripheral blood monocytes and the surface expression of peripheral blood monocyte Fcγ receptors, FcγRI and FcγRII, were determined on inclusion and at the end of the first, second, fourth, and sixth months after enrollment.

Preparation of monocytes.

Human monocytes were isolated in suspension as previously described (9, 17, 18). Briefly, mononuclear cells were isolated from heparinized blood by density gradient centrifugation. Between 40 × 106 and 60 × 106 mononuclear cells in RPMI 1640 medium containing 25 mg of glutamine, 100 U of penicillin, 100 mg of streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) per ml were incubated in 125-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Corning, Madrid, Spain) pretreated with heat-inactivated FCS (M.A. Bioproducts, Madrid, Spain) and were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed five times with RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS to remove nonadherent cells. Adherent cells were harvested by striking the flasks against a soft surface to dislodge the cells and were then rinsed with Hanks' balanced salt solution (without Ca2+ or Mg2+) containing 0.5 mM EDTA. Cells presented the appearance of monocytes after Wright-Giemsa staining (Diff-Quik, Dade Diagnostics, Madrid, Spain); more than 95% stained positive with nonspecific esterase, more than 90% were able to phagocytose latex particles and to readhere to plastic, and more than 95% were viable as assessed by trypan blue dye exclusion (9, 17, 18).

Flow cytometry.

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) directed against FcγRI (MAb32.2), FcγRII (MAbIV.3), and FcγRIII (MAb3G8) were used in indirect immunofluorescence binding studies to assess protein expression of these receptors on monocytes. Experiments were performed as previously described (9, 17, 18). Cells were incubated with antibodies for 30 min at 4°C and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 0.02% sodium azide. Bound antibodies were labeled by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse Ig antibody (Tago, Inc., Burlingame, Calif.) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed twice, fixed with 4.0% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Fluorescence was measured by a FACScan cytometer with Consort 32 software (Becton-Dickinson, Madrid, Spain). For all samples, 10,000 events were recorded on a logarithmic fluorescence scale, and the actual mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for each sample was determined. In order to correct for autofluorescence, the MFI of a nonreactive murine IgG1 antibody (P3×63) was subtracted from the MFI of the anti-FcγR-stained cells. Change in mean fluorescence intensity was calculated as ΔMFI (change in MFI) = (MFI of anti-FcγR MA-treated cells − MFI of P3×63 MA-treated cells) − (MFI of anti-FcγR control cells − MFI of P3×63 control cells).

Preparation of IgG-sensitized RBCs.

Antibody-sensitized sheep erythrocytes were prepared as previously described (9, 17, 18). In brief, 1 × 109 sheep RBCs in 1.0 ml of 0.01-mol/liter EDTA buffer were sensitized by adding mouse monoclonal antibody Sp2/HL, subclass IgG2b (Serotec Ltd., Bicester, Oxon, England), in 0.1 ml at 37°C for 1 h. We used the optimal antibody dilutions found in previous studies, 1:20 and 1:80 (9, 17, 18). The IgG-sensitized sheep RBCs were washed twice and resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution to a final concentration of 108 cells/ml.

Monocyte recognition of sheep IgG-sensitized RBCs.

In vitro monocyte recognition of IgG-sensitized RBCs was assessed as previously reported (9, 17, 18). Monocyte monolayers containing 106 cells were prepared from peripheral blood (9, 17, 18). These cells were incubated at 4 or 37°C in phosphate buffer at an ionic strength of 0.07 or 0.15, respectively. After 2 h, the plates were washed and stained with Wright's Giemsa. Two hundred monocytes were counted blind under light microscopy to assess the number of IgG-sensitized RBCs bound per monocyte. Monocytes binding ≥3 RBCs per monocyte were determined. Binding tests of murine IgG-sensitized RBCs by human monocytes from normal volunteers were performed in parallel.

Statistics.

To assess whether the difference between two means was significant, the unpaired or paired t test was used. Correlation between variables was assessed by Wilcoxon's correlation test.

RESULTS

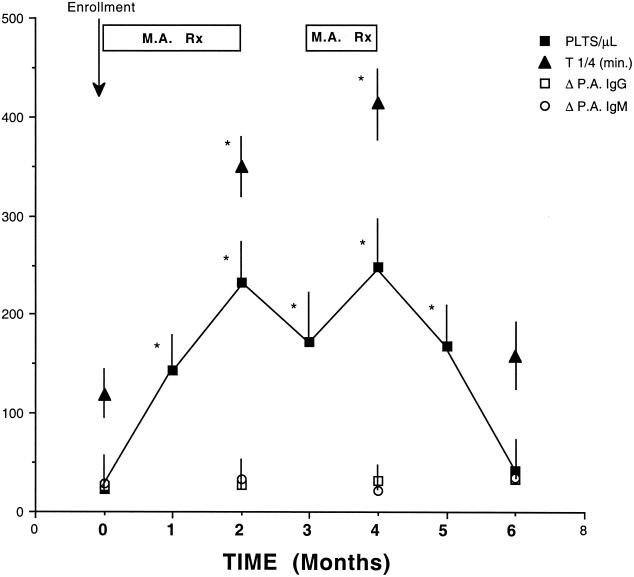

Treatment with MA under the regimen described enhanced the platelet count in all 28 patients. Platelet count increased from 22,280 ± 2,110 per ml (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) before treatment to 232,472 ± 3,122 per ml after 2 months of MA treatment (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). One month after MA withdrawal (i.e., in months 3 and 5), the mean platelet counts (171,830 ± 2,742 per ml and 247,378 ± 3,014 per ml, respectively) were significantly higher than pretreatment values (P < 0.001). Two months after MA withdrawal (i.e., in month 6), the mean platelet count (41,170 ± 2,436 per ml) did not differ significantly from baseline values (P = not significant). Twenty two patients (78.57%) presented a complete response with MA treatment (i.e., in month 4). One month after terminating MA treatment (i.e., in month 5), 19 patients (67.86%) presented a complete response, 6 patients a partial response, and 3 patients no response, while a month later (i.e., in month 6) 12 patients (42.86%) were still in complete response.

FIG. 1.

Effects of treatment with MA on platelet count, platelet survival, and platelet-associated immunoglobulin. Patients were treated with MA during the first, second, and fourth months after enrollment (MA Rx). Patients were not treated with MA during the third, fifth, and sixth months after enrollment. Platelet count and platelet survival (T 1/4, in minutes) increased significantly after the first and second months of treatment with MA (P < 0.001). Platelet-associated immunoglobulins (Δ P.A. IgG and Δ P.A. IgM) were not significantly altered by MA treatment at any stage of the study. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗, P < 0.001.

Platelet survival (mean ± SEM) was significantly shortened on enrollment (T 1/4 = 118.50 ± 28 min) (P < 0.001). Two months of MA treatment increased the platelet survival in all patients; 17 of the 28 patients (60.07%) attained normal platelet survival. Mean platelet survival increased significantly to T 1/4 = 350.10 ± 43 min after 2 months of MA treatment (i.e., by month 2) (P < 0.001). Two months after MA withdrawal (i.e., in month 6), mean platelet survival (156.90 ± 87 min) did not differ significantly from baseline values (Fig. 1). Platelet-associated immunoglobulins, change in platelet-associated IgG, and change in platelet-associated IgM were not significantly altered by MA treatment at any stage of the study (Fig. 1).

We assessed the surface expression of both Fcγ receptors expressed by peripheral blood monocytes, FcγRI and FcγRII by using flow cytometry (Table 2). Results are expressed as percent inhibition of the mean fluorescence intensity below pretreatment values (mean ± SEM). The expression of peripheral blood monocyte FcγRI decreased significantly 1 and 2 months after MA treatment, by 41.13% ± 3.71% and 51.80% ± 4.73%, respectively (P < 0.001). The expression of peripheral blood monocyte FcγRII decreased significantly 1 and 2 months after MA treatment by 36.83% ± 4.21% and 45.53% ± 4.47%, respectively (P < 0.001). Two months after MA withdrawal, the expression of peripheral blood monocyte Fcγ receptors FcγRI and FcγRII did not differ significantly from baseline (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effect of treatment with MA on platelet count and platelet survivala

| Parameter | Before treatment | Mo 1 | Mo 2 | Mo 3 | Mo 4 | Mo 5 | Mo 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA dose (mg/kg/day) | 640 | 826 ± 51 | None | 826 ± 51 | None | None | |

| Platelet count (no./μl) | 22,280 ± 2,110 | 147,522 ± 2,620 | 232,472 ± 3,122 | 171,830 ± 2,742 | 246,378 ± 3,014 | 170,306 ± 2,916 | 41,170 ± 2,036 |

| Responders | 152,762 ± 2,813 | 239,931 ± 3,213 | 186,244 ± 2,991 | 257,703 ± 3,121 | 174,707 ± 3,011 | 49,933 ± 2,996 | |

| Partial responders | 96,331 ± 1,602 | 98,271 ± 1,917 | 76,207 ± 1,237 | 97,326 ± 1,826 | 94,201 ± 1,348 | 37,126 ± 2,198 | |

| Nonresponders | 41,670 ± 1,172 | 43,771 ± 1,237 | 41,891 ± 1,301 | 44,212 ± 1,403 | 42,137 ± 1,205 | 27,733 ± 2,343 | |

| Platelet survival, T 1/4 (min) | 118,50 ± 28 | 350,12 ± 43 | 426,32 ± 51 | 156,91 ± 87 | |||

| Responders | 391,72 ± 39 | 455,37 ± 58 | 167,07 ± 89 | ||||

| Partial responders | 267,91 ± 32 | 297,92 ± 42 | 132,27 ± 39 | ||||

| Nonresponders | 107,73 ± 24 | 132,33 ± 38 | 122,56 ± 31 |

Twenty-eight patients with HIV-associated thrombocytopenia, with shortened platelet survival and elevated platelet associated IgG, treated with MA for anorexia-cachexia, participated in the study. The evolution of the platelet count and the platelet survival on enrollment (before treatment) and during treatment with MA are shown. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM for the 28 patients as well as for those patients showing a complete response (responders), a partial response, or no response.

The in vitro recognition of IgG2b-sensitized RBCs by peripheral blood monocytes at two ionic strengths (0.15 and 0.07) was determined to assess the functioning of FcγRI (Δμ = 0.15) and FcγRII (Δμ = 0.07) (9, 18). Results are expressed as percent inhibition compared with pretreatment values (mean ± SEM). The recognition of IgG2b-sensitized RBCs by peripheral blood monocyte FcγRI (μ = 0.15) was significantly inhibited after 1 and 2 months of MA treatment, by 22.23% ± 1.71% and 43.30% ± 2.26%, respectively (P < 0.001). The recognition of IgG2b-sensitized RBCs by peripheral blood monocyte FcγRII (μ = 0.07) was significantly inhibited after 1 and 2 months of MA treatment, by 18.42% ± 1.41% and 35.43% ± 2.37%, respectively (P < 0.001). Two months after MA withdrawal, the recognition of IgG2b-sensitized RBCs by peripheral blood monocyte Fcγ receptors FcγRI and FcγRII did not differ significantly from baseline (Table 2).

Platelet survival significantly correlated with platelet count (P < 0.001). No relationship was observed between platelet survival and the level of platelet-associated IgG or IgM. Neither the platelet count nor the expression of monocyte Fcγ receptors was correlated with body mass index, number of CD4 cells, plasma RNA HIV load, or circulating immune complexes.

MA treatment was well tolerated. No side effects severe enough to discontinue treatment were reported. No changes were observed in hematologic parameters other than platelets during the course of treatment. Increased appetite and weight gain were observed in 85.71% of the patients. No consistent elevation of blood glucose, total cholesterol, or triglyceride levels was observed in this short-term study. No significant alterations of liver enzymes by treatment with MA were observed in the 17 (60.71%) patients with chronic hepatitis C virus liver disease.

DISCUSSION

The data obtained in this short-term study suggest that treatment with MA significantly enhances platelet count and survival; it decreases the surface expression of macrophage Fcγ receptors, FcγRI and FcγRII, and does not alter the platelet-associated immunoglobulin. Treatment with MA for 1 month produced a complete response in the majority (78.57%) of the patients studied, while 2 months after MA withdrawal, 42.86% of patients were still in complete response.

Platelet-associated IgG or IgM and circulating immune complexes were not altered by MA treatment. The increased platelet count and survival and decreased expression of peripheral blood monocyte Fcγ receptors, FcγRI and FcγRII, observed do not seem to be due to weight gain or to progression of HIV infection, since those effects of MA were not correlated with the body mass index or with the number of CD4 cells and HIV RNA plasma viral load, respectively. No significant changes were observed in the body mass index, number of CD4 cells, or plasma HIV load during follow-up.

Enhanced platelet production by MA may in part explain the increased platelet count. Nevertheless, our findings of enhanced platelet survival and decreased expression of macrophage Fcγ receptors, with no alteration of platelet-associated immunoglobulin following MA treatment, cannot be explained by an improved bone marrow production of platelets. Therefore, the most consistent mechanism for the observed MA treatment effect is a decreased macrophage Fcγ receptor-dependent phagocytosis, resulting in longer platelet survival and platelet count.

It has recently been observed that the beneficial effects of treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin for immune cytopenias depends upon induction of the surface expression of macrophage FcγRIIB (21). Our finding of decreased monocyte FcγRII expression is not in contradiction with that observation, since our experimental design does not differentiate between the expression of receptor isotypes FcγRIIA and FcγRIIB. Thus, while the surface expression of the monocyte receptor FcγRIIB may indeed be enhanced, the surface expression of the other receptor isotype FcγRIIA may have been decreased. Another pathophysiological limitation of our study is the lack of data on the macrophage FcγRIII that is also involved in the pathophysiology of immune cytopenias (2, 3, 5-7, 12). We have not performed invasive studies to harvest macrophages (peritoneal, pulmonary, or splenic). Nevertheless, we did determine the surface expression of FcγRIII by peripheral blood monocytes in some patients, but its expression was either very low or absent.

Our results indicate that MA treatment improves platelet count and platelet survival in patients with HIV-associated thrombocytopenia, with shortened platelet survival and with elevated platelet-associated immunoglobulin. Therefore, progesterones such as megestrol acetate may be used in the treatment of immune cytopenias, with few short-term side effects. The effect of MA compared with glucocorticoids and the risk-benefit ratio of glucocorticoids in combination with MA for the treatment of immune cytopenias await confirmation by appropriate clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia (PM92-0259 and RE-28515062) and the Consejería de Educacion, Junta de Andalucía (Group 3224).

We are grateful to Royston F. Snart for assistance with the English language presentation of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, J. 1994. Response of resistant idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura to pulsed high-dose dexamethasone therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 330:1560-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bussel, J. B. 2001. Fc receptor blockade and immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Semin. Hematol. 37:261-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bussel, J. B., R. P. Kimberly, and R. D. Inman. 1983. Intravenous gammaglobulin treatment of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 62:480-486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creighton, W. D., P. H. Lambert, and P. A. Miescher. 1973. Detection of antibodies and soluble antigen-antibody complexes by precipitation with polyethylene glycol. J. Immunol. 111:1219-1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debré, M., M.-C. Bonnet, W.-H. Fridman, and E. Carosella. 1993. Infusion of Fcγ fragments for treatment of children with acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Lancet 342:945-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deo, Y. M., R. F. Graziano, R. Repp, and J. G. J. van de Winkel. 1997. Clinical significance of IgG Fc receptors and FcγR-directed immunotherapies. Immunol. Today 18:127-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fehr, J., V. Hoffman, and U. Kappele. 1982. Transient reversal of thrombocytopenia in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura by high dose intravenous gammaglobulin. N. Engl. J. Med. 306:1254-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George, J. N., M. A. El-Harake, and G. E. Raskob. 1994. Chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. N. Engl. J. Med. 331:1207-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez, F., P. Chien, M. King, P. McDermott, A. I. Levinson, M. D. Rossman, and A. D. Schreiber. 1989. Monocyte Fcγ receptor recognition of cell bound and aggregated IgG. Blood 74:1058-1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez, F., P. Ruiz, and A. D. Schreiber. 1994. Impairment of Fcγ-receptor predisposes to severe bacterial infection in alcoholic cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 331:1122-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez, F., P. Ruiz, F. Briceño, R. Lopez, and A. Michan. 1998. Treatment with progesterone analogues decreases macrophage Fcγ receptors expression. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 89:231-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimberly, R. P., J. E. Salmon, and J. B. Bussel. 1984. Modulation of mononuclear phagocyte function by intravenous gammaglobulin. J. Immunol. 132:745-749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris, L., A. Distenfeld, E. Amorosi, and S. Karpatkin. 1982. Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura in homosexual men. Ann. Intern. Med. 96:714-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oster, M. H., S. R. Enders, S. J. Samuels, L. A. Cone, T. M. Hooton, H. P. Browder, and N. M. Flynn. 1994. Megestrol acetate in patients with AIDS and cachexia. Ann. Intern. Med. 121:400-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panel on Diagnostic Application of Radioisotopes in Hematology International Committee for Standardization in Hematology. 1977. Recommended methods for radioisotope platelet survival studies. Blood 50:1137-1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravetch, J. V., and S. Bolland. 2001. IgG Fc receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:275-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossman, M. D., P. Ruiz, P. Comber, F. Gomez, M. Rottem, and A. D. Schreiber. 1993. Modulation of macrophage Fcγ receptors by rGM-CSF. Exp. Hematol. 21:177-181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruiz, P., F. Gomez, R. Lopez, P. Chien, M. D. Rossman, and A. D. Schreiber. 1992. Granulocyte Fcγ receptor recognition of cell bound and aggregated IgG: effect of γ-interferon. Am. J. Hematol. 39:257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz, P., F. Gomez, and A. D. Schreiber. 1990. Impaired macrophage Fcγ receptor function in chronic renal failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 322:717-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz, P., R. Lopez, and F. Gomez. 1992. Megestrol acetate treatment of symptomatic HIV-1 associated thrombocytopenia. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 22:218. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuelsson, A., T. L. Towers, and J. V. Ravetch. 2001. Anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG mediated through the inhibitory Fc receptor. Science 29:484-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiber, A. D., and M. M. Frank. 1972. Role of antibody and complement in the immune clearance and destruction of erythrocytes. I. In vivo effects of IgG and IgM complement-fixing sites. J. Clin. Investig. 81:575-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiber, A. D., and M. M. Frank. 1972. Role of antibody and complement in the immune clearance and destruction of erythrocytes. II. Molecular nature of IgG and IgM complement-fixing sites and effects of their interaction with serum. J. Clin. Investig. 51:583-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schreiber, A. D., F. M. Nettl, M. C. Sanders, M. King, P. Szabolcs, D. Friedman, and F. Gomez. 1988. Effect of endogenous and synthetic sex steroids on the clearance of antibody-coated cells. J. Immunol. 141:2959-2963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Von Roenm, J. H., R. L. Murphy, and K. M. Weber. 1988. Megestrol acetate for the treatment of cachexia associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 109:840-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Von Roenm, J. H., D. Armstrong, D. P. Kotler, D. L. Cohn, N. G. Klimas, N. S. Tchekmedyian, L. Cone, P. J. Brennan, and S. A. Weitzman. 1994. Megestrol acetate in patients with AIDS-related cachexia. Ann. Intern. Med. 121:393-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh, C. M., M. A. Nardi, and S. Karpatkin. 1984. On the mechanism of thrombocytopenic purpura in sexually active homosexual men. N. Engl. J. Med. 311:1052-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]