Abstract

Offshore carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) is to capture CO from emission sources and then inject the captured CO into sub-seabed geological reservoirs, thus it will be permanently isolated from the atmosphere. CCUS was therefore proposed as a technological decarbonization strategy to prevent millions of tonnes of anthropogenic CO from entering and remaining in the atmosphere. In this review, the necessity and suitability of offshore CCUS in China are explored, involving examining the potential for sedimentary basins offshore China to act as carbon sinks for industrialized coastal regions and investigating the opportunities of developing a commercial full value chain. In China, the CO emissions from the 14 coastal provincial administrative regions are estimated to be over 4.2 Gt, occupying 41% of the country’s carbon emissions, whereas the storage capacity of the sedimentary basins offshore China is estimated to be 573–779 GtCO. This could total 140–190 years of emissions from China’s coastal regions, which also avoids complex legal regulation and public opposition. However, economic costs pose substantial challenges to deploying offshore CCUS on a commercial scale, which requires significant technological innovations, national contributions, and business investments, particularly in the eastern and southeastern regions.

Keywords: Offshore; Carbon capture, utilization, and storage; CCUS; Carbon-neutral; China

1. Introduction

To achieve China’s goal of carbon neutrality by 2060, greenhouse gas emissions from atmospheric sources of carbon need to be mitigated and preferably permanently sequestered. This has encouraged the development of methodologies to mitigate CO emissions, including electrification, fuel switching, renewable energy, bio-energy, and carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS). China has made substantial progress in electrification and renewable energy deployment, while the carbon-intensive generation reflects a paradox in China’s energy revolution, suggesting the necessity of an extra substantial carbon emission reduction strategy. The large-scale deployment of the CCUS can avoid the failure of assets in existing fossil energy industries and reduce the resistance of incumbents [1]. With an estimated storage capacity between 1873 and 3067 GtCO, China has enormous potential for CCUS deployment.

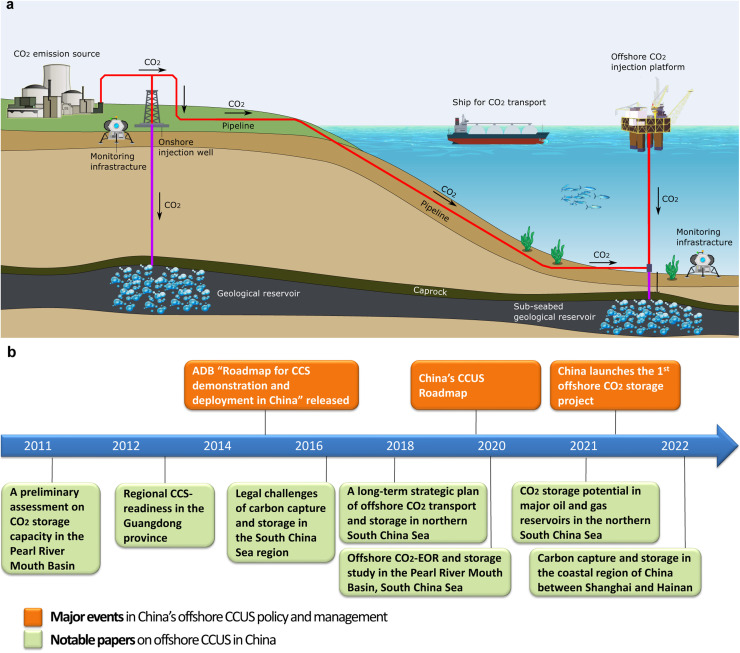

Of the 34 provincial administrative regions in China, 12 are along the mainland coast and 2 are islands, which occupy less than 14% of the nation’s territorial area, but contribute approximately 41% of the country’s CO emissions [2], [3]. In these regions, most large stationary sources, e.g., power plants, refineries, and cement plants, are along the coast. The water area close to the coast comprises China’s ten offshore sedimentary basins, which cover 1.7 million square kilometers. These basins were proposed to allow for point elimination of greenhouse gases through a complete technically workable and safe full-chain offshore CCUS (Fig. 1). This value chain can be developed by engaging contractors and suppliers, whereas the potential risks must be fully characterized and mitigated.

Fig. 1.

Offshore CCUS and notable publications. (a) Key elements and processes in offshore CCUS. Offshore CCUS is to capture CO from industrial emission sources, transport it via either pipeline or ship, and inject it into sub-seabed geological reservoirs, contributing to the isolation of CO from the atmosphere. (b) Timeline indicating the evolution of notable papers [2], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9] concerning China’s offshore CCUS as on 31 Oct. 2022, and major moments [10], [11], [12] in China’s key events in offshore CCUS policy and management.

The CCUS in China has been tested both onshore and offshore [2], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Onshore geologic reservoirs in China are mostly in the northern and western regions, which are distant from the industrialized and populated coastal regions and may raise extra costs and safety issues. Compared to onshore storage sites, access to offshore sites will not pose issues such as CO contamination of drinking water, and potential damage to agricultural and industrial operations [13]. In addition, to provide energy for the CCUS offshore infrastructure, low-carbon opportunities from wind, solar, waves, and tides could be introduced [14].

Globally, the distribution and thickness of sediment accumulations over continental margins have been mapped for prospective offshore storage resource regions [15]. And it is inferred that the cumulative storage of over 100 GtCO by 2050 is the most efficient achieved with 5–7 regions pursuing an offshore well development model on a Norwegian scale [15]. These regions include the North Sea, Tomakomai Port Japan’s offshore area, Brazil’s Santos Basin, the South China Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Gippsland Basin of Australia. These areas have been prospective targeted large-scale geologic storage sites for full-chain offshore CCUS (Table 1), among which two have been completed (“K12-B” in the Netherlands and “Tomakomai” in Japan) and four are active (“Sleipner” and “Snöhvit” in Norway, “Lula” in Brazil and “Enping” in China). These projects, particularly the “Sleipner” and “K12-B”, have several decades of safe CO injection. Among these projects, the “Lula” project in Brazil uses offshore carbon dioxide-enhanced oil recovery (CO-EOR) in the ultra-deepwater field, which produces approximately 800,000 barrels per day [16], [17]. The “Tomakomai” project in Japan captured CO from the refinery’s hydrogen production facility and reduced CO emissions from onshore industries. There are also several planned advanced offshore CCUS projects based on the development of industrial hubs, aiming to benefit from economies of scale and reduce integration risk through shared CO transport and storage infrastructure. These include the Port of Rotterdam (Porthos) project in the Netherlands, the Acorn & Net Zero Teesside projects in the UK, and the CarbonNet project in Australia. To explore the involvement of renewable energies in the chain, several of these offshore CCUS hubs involve the production of low-carbon hydrogen [18].

Table 1.

Commercial offshore CCUS projects completed, in operation, and planned in 2022.

| Country | Project | Operation date | Termination date | Source of CO | Capture capacity (Mt/year) | Primary storage type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | Sleipner | 1996 | / | Natural gas processing | 1.0 | Dedicated |

| Netherlands | K12-B | 2004 | 2017 | Natural gas processing | 0.02 | Dedicated |

| Norway | Snöhvit | 2008 | / | Natural gas processing | 0.7 | Dedicated |

| Brazil | Lula | 2011 | / | Natural gas processing | 0.7 | EOR |

| Japan | Tomakomai | 2016 | 2019 | Hydrogen production | 0.1 | Dedicated |

| China | Enping | 2021 | / | Natural gas processing | 0.3 | Dedicated |

| Norway | Northern Lights | planned | / | Onshore industries | 0.8 | Dedicated |

| Norway | Longship | planned | / | Onshore industries | 1.5 | Dedicated |

| Netherlands | Porthos | planned | / | Onshore industries | 2.5 | Dedicated |

| Australia | CarbonNet | planned | / | Onshore industries | 5 | Dedicated |

| UK | Acorn & Teesside | planned | / | Onshore industries | 10 | Dedicated |

| US | Houston Ship Channel | planned | / | Onshore industries | 50-100 | Dedicated |

In 2021, China launched its first offshore CCUS project in the northern South China Sea’s Pearl River Mouth Basin (PRMB). Under this project, the injection of 1.46 MtCO into sub-seabed saline formations was planned by 2026, which would achieve near-zero emissions from offshore oil production [12], [19]. This has provided a prior workable test of the long-term performance and security of offshore CO storage for maturing China’s offshore CCUS as an attractive and efficient long-term strategy [15], [20], particularly for those industrialized coastal regions to achieve their “ahead of time” Carbon Neutrality commitments.

In this review, to evaluate the necessity and feasibility of developing offshore CCUS in China, Section 2 presents the distribution of national carbon emissions and Section 3 assesses the potential capacity of offshore basins to mitigate CO emissions in China. While the large-scale deployment of offshore CCUS in China faces cost challenges and technology gaps, these are discussed in Sections 4 and 5, respectively. To progress China’s net-zero emissions, opportunities for developing offshore CCUS are explored in Section 6. And Section 7 summarizes the path of accelerating offshore CCUS to achieving China’s target of Carbon Neutrality by 2060.

2. Distribution of carbon emissions

In China, carbon emissions vary geographically depending on the level of industrial development. Most communities and industries are in the east and southeast coastal regions, which are also the most populous. These coastal regions contribute 64% of the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP), account for 43% of the country’s energy use, possess 39% of the country’s population, and have been dominantly driving China’s economy in the last 40 years [21], [22]. While contributing to the economy, these areas also account for 41% of the country’s annual CO emissions, i.e., 4.2 Gt [2], scattering notable CO emission hotspots. This is because fossil fuels are widely used to provide energy supplements [2]. Apart from mobile emissions sources such as aircraft, shipping, and automobiles, many world-class stationary CO emission sources are in these regions [22], including power plants, cement and refineries, and steel and iron foundries [8], [23], [24].

In 2020, China emitted 10.67 GtCO, burning coal, oil, and gas for 70%, 15%, and 6%, respectively [25]. To reduce the consumption of coal, China has justified ongoing efforts to support the use of renewable energy and natural gas, while over 50% of the electricity mix is still from coal-fired power plants, this represents potential emissions of 85 GtCO if they continue to operate at current load factors for the remaining of their lives [26]. A more worrying thing is that some of the world-class CO emission sources in China are from relatively newly built power plants, the average of which is less than 15 years and could still operate in 2060 [27]. This poses a particular challenge in meeting the national goal of carbon neutrality. More severely, in recent years, because of climate change, renewable capacity has indicated an unstable electric power supply, which makes it unlikely to be a stable alternative to replace the coal-fired power plants in the following 40 years. As a result, retrofitting the power plant is an indispensable means of achieving the Carbon Neutrality target, and geological storage has the greatest potential. In the IEA Sustainable Development Scenario relative to the Stated Policies Scenario, the CCUS accounts for nearly 15% of the cumulative reductions in carbon emissions from 2020 to 2070 [28]. To realize this, China, particularly the eastern and southeastern regions with the heavy industry of large CO emissions and with limited access to onshore storage, has to adopt high-efficiency retrofits on its coal-fired plants and develop offshore CCUS.

3. Geological storage in offshore sedimentary basins

For the best candidate, the geological storage sites for the retrofits of the CCUS in power plants are of critical importance, considering the distance, cost, technology, and public perception (Table 2) [26]. China’s coastal water zone extends over 4.73 million square kilometers and comprises ten offshore sedimentary basins (Fig. 2). This provides excellent opportunities for the permanent sequestration of CO at sea near coastal regions [2] and makes the transport of CO at sea less costly and has fewer safety concerns.

Table 2.

Pros and Cons of the offshore CCUS compared to the onshore CCUS for various factors.

| Offshore vs. Onshore | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Geography | 1. For East and Southeast China, access to onshore CO storage would normally be greater than 750 km, while the offshore sites can be within 200 km. | n/a |

| Society | 1. Offshore CO storage is unlikely to damage the groundwater, agricultural and industrial operations, which could be an issue for onshore storage. | n/a |

| 2. Offshore storage may face less opposition as it takes away CCUS infrastructure and the associated perceived risks from populations. | ||

| 3. Offshore sites provide jurisdictional simplicity. | ||

| 4. The unlikely leakage offshore is less damaging than onshore, as CO can disperse into the seawater column. | ||

| Economy | 1. For East and Southeast China, the shorter distance from offshore storage sites may need to pay less for CO transport. | 1. Operational complexity and costs can increase with offshore conditions. |

| 2. Offshore CO transport and storage do not have to pay high land prices. | ||

| 3. Managing the offshore geological pressure of storage reservoirs avoids the production of brine onshore, the cost of which can be high. | ||

| Technology | 1. Managing formation pressure from large-scale CO injection into offshore geological formations is relatively simpler than onshore. | 1. Limited space and weight on offshore platforms. |

| 2. Offshore sites can provide electrical generation opportunities through low-carbon technologies, such as wind, waves, and tides. | 2. Extra effort to adjust to sub-sea conditions. |

Fig. 2.

Estimated COstorage capacity of the ten offshore basins in China[4], [9], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. Some error bars are not shown because of a lack of reliable data sources.

3.1. Distribution and capacity assessment for storage reservoirs

The evaluation of the suitability and capacity of geological CO storage in China has been intensively conducted over the past decade [29], [30]. Twenty three main onshore and ten main offshore sedimentary basins account for 1300–2288 GtCO and 573–779 GtCO storage capacity, respectively, which could total 200–300 years of emissions from China [10], [31]. For these basins, onshore formations are dominantly in north and west China, while offshore formations are available along most of the coastal regions, providing potential offshore CCUS locations [11].

For the carbon source-sink pairing, the heavily industrialized eastern and southeastern coastal regions would have less access to the abundant onshore storage basins as they are normally over 750 km from the potential large-scale onshore CO reservoirs, which potentially raises the transportation cost and the safety risk. Many large emission sources, such as power plants, in the coastal regions, have no suitable onshore geologic basins within 1500 km, which makes the onshore access to them less cost-effective as it would need to develop long-distance CO pipeline infrastructure to the distant northern and western onshore reservoirs [18]. In contrast, large-scale offshore sub-sea basins may be available within 50 to 300 km in most of the coastal regions and the average CO transport distance may be within 200 km. This offers lower overall costs and makes offshore storage a more natural and primary option for disposing of CO for the eastern and southeastern coastal regions where high CO emissions are located [6] (see Section 4.1).

Most offshore storage capacity is in saline formations, with the CO storage capacity estimation of the PRMB to 70–300 Gt, the Yinggehai Basin to 56–160 Gt, the Beibu Gulf Basin to 24–57 Gt, and the Qiongdongnan (Southwest Hainan) Basin to 41 Gt, etc. (Fig. 2) [4], [31], [32]. Amongst these basins, PRMB is the most studied (in terms of publication numbers related to offshore CCUS) and has been the focus of research on the targeted carbon storage site for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Taiwan, the largest island in China, where the onshore storage capacity is estimated to be 2.8 Gt while the offshore West Taiwan Basin (3.6–13.7 Gt) and the Southwest Taiwan Basin (68 Gt) can provide 72–82 Gt capacity for CO geological storage [31], [34], [35]. In these basins, oil and gas fields account for ∼2.5% of the total 4 GtCO storage capacity [7]. The reservoir geology of these fields has now been well understood and there is existing offshore infrastructure (pipeline and platforms), which is considered a priority for near-term offshore CO storage project opportunities [36].

3.2. Social reflection

While offshore storage reservoirs provide sufficient volume to dispose of CO from eastern and southeastern China, there are fewer safety concerns with the offshore CCUS. In some regions, such as the North, onshore CCUS could be economically and technically workable, while concerns have been related to health, safety, and environmental issues relative to pipeline construction and CO storage sites [37], [38]. These concerns are mainly coming from the potential leakage of CO from the pipelines and/or the geologic reservoirs in their vicinity, threatening the human community, local property, agriculture, and livestock [39], [40], [41]. According to a statistical investigation in China concerning the development of onshore CCUS, over 90% of respondents do not object to it, but few of them were willing to allow a CCUS project within 100 km of where they are living [42].

In the social sciences [40], [43], [44], some planned onshore CCUS projects have been criticized and led to strong protests among local communities [41]. This raises a critical warning about the large-scale deployment of onshore geological CO storage in populated northern China, such as Shandong, Hebei, and Liaoning provinces. In contrast, offshore CO storage moves infrastructure away from coastal populations, which reduces these challenges and is therefore preferred. In addition, it offers jurisdictional simplicity for regional governments to manage the utilization of area of jurisdiction for CO storage as offshore transport would be less visible and would unlikely impact the local population and could be easier to perform the carbon source-sink pairing for the highest economic benefit. Further, the seawater column off the coast (minimum 50 km in the South and the East China Sea) acts as a natural barrier, which not only minimizes the unlikely environmental risk to the coastal communities but also reduces underwater hazards to the marine environment and ecosystem by dispersing the unlikely CO leakage.

4. Cost evaluations and reduction potentials

High costs are currently the major impediment to the deployment of the offshore CCUS and opportunities to reduce costs need to be explored to minimize them. To evaluate the cost reduction potentials for future offshore CCUS projects, the specific net present costs (NPC), Chinese Yuan (CNY or ¥) ton of CO stored have to be firstly estimated. Estimates are based on updated data from industrial engineering studies and operational cost calculations for the offshore CCUS [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54]. The cost estimates from the capture, transport, and storage are often provided in a cost breakdown structure (CBS) for detailed analyses (Table 3) [52], i.e., the capture for a specific plant type, the transport to the nearest suitable geological storage site, and the storage at that site determined by the type of the geological resources in offshore depleted oil and gas fields (DOGF) or saline aquifers (SA). With specific contributions to the technology and supply chain development of each component of the offshore CCUS, a full demonstration value chain will lower costs.

Table 3.

Cost breakdown structure of the full offshore CCUS value chain. These estimates could estimate potential cost reduction curves based on future economies of scale, value chain optimization, and technology development [52].

| Capture | Transport | Storage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration | Connection to Chimneys | CAPEX | Docks | Quay & items offloading to interim storage | |

| COcapture | Pre-treatment of flue gases | OPEX | Temporary storage | Interim storage | |

| CO Absorbtion | Pump & temp. control | ||||

| Landfall for pipeline | |||||

| Treatment for transport | Solvent regenerationCompression, liquifaction, conditioning | Docks | Onshore transport to interim storage,Transport to ships/pipes | Injection | CO injection well(s)Control system |

| Temporary storage | Transport to temporary storageTemporary storage | Pipes | Offshore CO pipesSubsea itemsUmbilical | Monitoring | Monitoring equipment for CO storage locationControl system |

| Ancillary systems | Ancillary systemsAdditional costsOwners costs | Ships | Compressed tankersFuels | Ancillary systems | Ancillary systemsAdditional costsOwners costs |

4.1. Cost evaluations

When estimating the large-scale full value chain of the offshore CCUS, costs are expected to decrease due to scale effects [48]. Fig. 3 shows cost reductions from the increased transport and field storage capacity, as well as the average cost per ton for possible large-scale onshore and offshore CCUS implementations for China’s eastern and southeastern regions. Note that the inputs to explore the cost estimate are evaluated from literature values multiplying currency exchange rates and the Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index (CEPCI) [55] for the cost year of study [50]. For transport and storage, the cost per ton decreases significantly when the value chain capacity is fully used from 2.5 to 20 million tons per annum (Mtpa) for transport and from 40 to 200 Mtpa for storage [46], [47]. This is due to increased capacity utilization in transportation and storage facilities. This includes short-distance offshore pipeline transport (i.e., 180 km to offshore storage sites) instead of transport by ships and long-distance onshore pipeline transport (i.e., 750 km or 1500 km to the major north or northwest onshore storage sites) with both cost reductions and savings. When the accumulated storage capacity increased from 40 to 200 MtCO annually, the cost levels could be reduced by about 3/4, indicating that field capacity has a high effect on costs for storage sites. The estimation also reveals that pipeline transport is normally cheaper than shipments; onshore storage is normally cheaper than offshore; qualification of storage in DOGF is normally cheaper than the qualification of storage in SA, and cost savings can be achieved if legacy wells and infrastructure can be re-used. It is also worth noting that even though a “general” cost could be estimated based on industry data, the cost, in reality, could be highly site-specific and a project cost estimation would need to take a range of practical implementation factors into account to reduce uncertainties.

Fig. 3.

Levelized costs in constant CNYtonCO. (a) Transport costs [46] per type and distance case; 180 km is a case of distance from the southeast coast to an offshore storage site, whereas 750 km and 1500 km are cases of onshore transport distance to the far north. (b) Storage costs per field capacity case to 40 Mtpa, 66 Mtpa, and 200 Mtpa scenarios [47]; Ons: onshore, Offs: offshore, DOGF: depleted oil/gas field, SA: saline aquifer, Leg: legacy infrastructure, No Leg: no legacy infrastructure.

A cost estimate for a value chain based on ZEP reports is presented in Table 4 [45], [46], [47], [48]. The estimate is based on captured CO from a coal-fired power plant with a 700 MWh electric capacity, which is expected to capture approximately 10 MtCO annually via post-combustion capture. The CO will be transported by pipes to an onshore storage site in the far northern or northwestern regions (750 km and 1500 km as examples) or an offshore site in the coast’s vicinity (180 km as a case [12]) with a medium field capacity of 66 Mtpa. The option of the offshore CCUS value chain with DOGF storage for China’s east and southeast industrialized regions shows the lowest cost level (i.e., the NPC for a 40-year horizon is CNY 404 ton CO). This is mainly because of the short distance transport from the capture site to the offshore storage reservoir and the avoidance of implementing new facilities. Notably, the simplified application does not account for the significant economies of scale that come with planned pipelines or shipment networks organized to facilitate efficient transport from clusters of emissions point source locations to clusters of geological sinks [56].

Table 4.

Overview of data for integrated offshore CCUS cases with a 40-year horizon[45], [46], [47], [48]. Costs for power plants and CO capture calculated for medium fuel costs; costs for pipeline transportation calculated for medium volume capacity 10 Mtpa; costs for storage reservoirs calculated for medium field capacity 66 Mtpa each field. All values are in constant CNY.

| CO Capture |

CO Transportation |

CO Storage |

Integrated |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | Cost | Volume | Transport |

Cost |

Accum. | Type | Legacy | Cost | Cost |

|||||

| MWh | ¥/t | Mtpa | km | type | CAPEX | OPEXpa | ¥/t | 40y Mt | Medium | Wells | ¥/t | ¥/t | 40y T¥ | |

| Coal-fired power plant | 700 | 300 | 10 | 750 | onshore | M¥9970 | M¥50 | 89 | 400 | DOGF | Yes | 33 | 423 | 169 |

| 700 | 300 | 10 | 750 | onshore | M¥9970 | M¥50 | 89 | 400 | DOGF | No | 45 | 434 | 174 | |

| 700 | 300 | 10 | 750 | onshore | M¥9970 | M¥50 | 89 | 400 | SA | No | 56 | 445 | 178 | |

| 700 | 300 | 10 | 1500 | onshore | M¥19807 | M¥100 | 176 | 400 | DOGF | Yes | 33 | 510 | 204 | |

| 700 | 300 | 10 | 1500 | onshore | M¥19807 | M¥100 | 176 | 400 | DOGF | No | 45 | 521 | 209 | |

| 700 | 300 | 10 | 1500 | onshore | M¥19807 | M¥100 | 176 | 400 | SA | No | 56 | 533 | 213 | |

| 700 | 300 | 10 | 180 | offshore | M¥3765 | M¥53 | 37 | 400 | DOGF | Yes | 67 | 404 | 162 | |

| 700 | 300 | 10 | 180 | offshore | M¥3765 | M¥53 | 37 | 400 | DOGF | No | 111 | 449 | 181 | |

| 700 | 300 | 10 | 180 | offshore | M¥3765 | M¥53 | 37 | 400 | SA | No | 156 | 494 | 197 | |

The capture cost shown in Table 4 is an average of several realistic estimates for coal-fired power plants [45], [54]. It accounts for more than half the cost of the value chain [48], [52]. Capture is the least mature part of the value chain and therefore has the greatest potential for reducing future costs. Pipeline costs are roughly proportional to distance and consist primarily (normally greater than 2/3) of capital expenditures (CAPEX) over 40 years. Because of high technical and commercial risk, the construction of a “point-to-point” offshore pipeline for a single demonstration project may be less attractive than ship transport, which is less CAPEX-intensive (normally less than 1/2 of total annual costs).

4.2. Cost reduction potentials

One of the major barriers for offshore CCUS has been to establish a viable business model which can cover the costs for the handling of CO through carbon capture, transport, and permanent storage. The other major barrier is that there are high initial costs for demonstration projects and substantial risks of the high investments for first-movers, which are needed for a full value chain of permanent storage [52]. Future scale-up and cost reductions depend first on the increased capacity utilization of the established infrastructure. The next step would be to develop further clusters with the expansion of volumes with large-scale capture and additional large-scale storage sites with direct pipeline injection. Large-scale offshore CCUS networks and implementation with several clusters are necessary to establish a commercially competitive offshore CCUS industry [52]. It is also important to investigate the logistics in more detail since it can be less expensive to use an easily accessible storage site closer to a CO source, even if it is an offshore site than to transport CO over long distances to an onshore established storage site. Details on the potential for cost reduction of an offshore CCUS value chain are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Opportunities to reduce direct and/or indirect costs for each component of the offshore CCUS.

| Components | Cost reduction opportunities |

|---|---|

| Capture | 1. From practice-based learning & economy of scale. Move from small pilots to large demonstration volumes, which will indicate capture costs and lessons learned from newer capture facilities. |

| 2. From generic learning rates. Implementing technology in the engineering processes of capture plants could reduce the overall cost. | |

| 3. From the improvement of post-combustion technologies. Post-combustion capture represents the current state-of-the-art technology to capture CO from flue gas. | |

| 4. From next-generation capture technologies. Cost savings are expected by continuing to research and develop promising breakthrough concepts. | |

| Transport | 1. From an understanding of the constraints for each transport case. The necessary CO specifications vary from chain to chain and some excessive designs may be reduced. |

| 2. From technology development and deployment. Optimal cost design for a pipeline network and, to a lesser extent, shipping. | |

| Storage | 1. From reciprocal arrangements for alternative COstorage. Offshore CCUS projects could consider themselves as an option for storing their CO emissions. |

| 2. From the reuse of existing infrastructure and established clusters. Offshore assets could be re-used if they were connected to a CO transportation system before decommissioning. | |

| 3. From technology development and deployment. This includes site characterization, injector drilling, operations, maintenance, and monitoring. | |

| 4. From offshore CO-EOR in a short term. CO-EOR would make the offshore CCUS a cost-effective technology. | |

| Value chain | 1. From the first complete process of offshore CCUS. This includes industry capture, ship and pipeline transportation, and DOFG or SA-based storage. |

| 2. From the establishment of predictable regulatory regimes. This can transfer risk categories and remove barriers for the private sector to invest in the offshore CCUS. |

4.2.1. Cost reduction in capture

The application of the offshore CCUS on a regional scale would likely incorporate a variety of technologies that optimize plant-specific retrofitting costs. Post-combustion capture as a technology category for combustion processes is mature and is considered to have a high level of technological preparedness for the offshore CCUS. Despite this, there is still a lot to learn from applying these technologies to different emission sources, on a larger scale, and optimizing energy use. At present, the greatest potential for cost reduction is the application of the technology to many industrial sources. This will promote research into future large-scale solutions and optimize existing technologies. Future large-scale emerging technologies that could contribute significantly to reducing capture costs are oxy-combustion and the redesign of cement and steel processes. Less advanced capture technologies can also help reduce costs in the long run.

4.2.2. Cost reduction in transport

For choosing an appropriate mode of transportation for CO, economics and regulatory frameworks are key considerations. For large volumes and moderate distances, pipelines are the most economical to transport. There may be volumes from remote areas that would depend on vessel transportation to a nearby hub with additional pipeline transportation. The selected transport solution with ships could be selected to make the offshore CCUS chain flexible, and because of the relatively low volume of CO over long distances and short time-frame. In China, particularly in the eastern and southeastern regions, strong transport capacity could situate the CO transport networks in advance [57], and retrofitting the existing offshore infrastructure could enable cost reduction [58].

4.2.3. Cost reduction in storage

In China, SA has been used for CO storage in the “Enping” offshore CCUS project. The injection and storage of approximately 0.3 MtCO annually at individual sites are technically viable, and innovative research has therefore gone beyond the viability of the technology. This project requires government support and currently cannot be described as commercial. To reduce CAPEX, CO-EOR has been practiced onshore in China for several years to enhance oil recovery from depleted or near-depleted reservoirs. There is a wealth of existing experience and knowledge, which has enabled CO-EOR to reach the highest level of technological maturity and operate commercially with bankable assets. Storage in DOGF is normally less expensive than storage in SA, particularly when EOR applies to make the offshore CCUS an economically viable technology today. However, its economic viability is subject to the cost per ton of CO delivered and the evolution of the oil price [59], [60], [61]. A 2016 review estimated that Brent’s price of ₤66–76 per barrel would be required for CO-EOR projects to be viable [62].

4.2.4. Cost reduction for the value chain

To offset the high cost, the most effective measure could be “smart planning”, including smart source-sink pairing and regional network design, as well as the smart use of existing infrastructure when the offshore hydrocarbon fields are depleted. The platforms in these fields are distributed in groups and clusters, facilitating CO transport and source-sink pairing with the quantified CO storage capacity in the sub-seabed reservoirs. An offshore CCUS value chain can be designed with different configurations, with different parts of the value chain at high or low costs. High-cost capture volumes require more operational experience and learning on a broader scale before more of these volumes are provided cost-effectively for storage. Improved technologies can help reduce heat or electricity consumption from a first pilot project. The goal of pilot projects would need to limit CAPEX while still getting industrial and relevant learning, reduce cost for following projects and enable further industrial opportunities related to offshore CCUS. Government investment support may have to optimize investment costs rather than the current net cost. It is expected that contingencies and allowances will be higher for the first-in-kind and subsequent initial projects than for future projects that have well-identified risks and measures to manage them.

5. Technology gaps in the offshore CCUS

Uncertainty about the costs of implementing the offshore CCUS is an efficiency penalty and should be reduced by the technological improvements and risk premium reductions faced by pioneers. To effectively achieve cost reduction and large-scale deployment, multiple ocean-based technologies need to be grouped and key bottlenecks at each stage of the offshore CCUS chain need to be identified (Table 6).

Table 6.

Technological challenges and innovation gaps associated with the capture, transport, storage, and utilization of COoffshore[17], [19], [82], [83], [84]. S: require strong effort; A: require additional effort; O: on track.

| Offshore CCUS | Technology challenges | Innovation gaps |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 capture | 1. High-capacity materials: materials (e.g., sorbents, solvents, membranes, etc.) with minimal energy requirements for regeneration, low toxicity, and long lifetime. (offshore & onshore) | S |

| 2. Cost reduction: configurations and engineering solutions that minimize costs, particularly in large-scale post-combustion capture. (offshore & onshore) | O | |

| 3. Flexible and retrofit: offshore engineering solutions that allow the capture of CO2 by bolting on the side steps required for large-footprint permanent structures. | A | |

| 4. Sub-sea separation: technologies that run sub-sea to unlock cheaper offshore CO2 separation closer to the storage point. | A | |

| 5. Direct air/seawater capture: technologies to decouple CO2 capture from point sources, allowing flexibility in the approach of a full carbon reduction facility. | A | |

| CO2 transport | 1. Corrosion: characterization and coatings and material solutions to prevent corrosion because of contaminants present in anthropic CO2. (offshore & onshore) | O |

| 2. Crack propagation: predictive maintenance solutions to prevent crack propagation and maintain pipeline integrity. (offshore & onshore) | O | |

| 3. Pressure control: low-cost control valves to maintain consistent pressure, especially in long sub-sea pipelines. (offshore & onshore) | O | |

| 4. Retrofit aging gas pipelines: clear understanding of costs and methods for retrofitting existing gas pipelines. (offshore & onshore) | O | |

| CO2 storage | 1. Modeling: more robust modeling of CO2 migration and interactions in various rock structures to predict the risk of leakage. (offshore & onshore) | O |

| 2. Site selection and injection strategy: compare disparate datasets of key metrics to optimize site selection and injection strategy. (offshore & onshore) | O | |

| 3. Geological behavior of CO2: improved characterization of in situ CO2 behavior at different injection sites. (offshore & onshore) | A | |

| 4. Site monitoring: standardized, low-cost, long-term post-sealing CO2 monitoring. (offshore & onshore) | O | |

| CO2 utilization | 1. Compact CO2treatment equipment: low-cost, compact treatment equipment to allow offshore CO2 handling for EOR. | A |

| 2. Sub-sea CO2separation and injection: technologies that work sub-sea and can unlock the cheaper offshore CO2 separation closer to the point of injection. | A | |

| 3. High-efficiency CO2conversion: low-cost CO2 utilization pathways to value-added products, e.g., blue hydrogen. | S |

5.1. Offshore CO capture technology

In China, many CO capture or separation technologies (e.g., amine-based chemical solvents, selectively permeable membranes, solid sorbent agents, and cryogenic separation [63], [64]) have been in commercial use for decades [65]. While only a small-scale pilot CO capture project is located offshore China, i.e., the Enping 15-1 [12], which makes the commercial prospect of offshore CO separation challenging. However, two CO separation methods could be considered: natural gas treatment and post-combustion CO capture. Well-head gas with higher impurities must be treated and post-combustion CO capture technology is the most established. However, space constraints on platforms make the deployment of logistics and economical technology offshore. Centralized offshore capture concepts have therefore been proposed [66], in which emissions from multiple nearby platforms are collected and treated on a fixed or floating central platform. This would bypass space constraints and provide economies of scale for carbon capture. A further feasibility study should be carried out on this concept. For the foreseeable future, mitigating platform emissions through hydrogen fuel switching or electrification is a more likely strategy to reduce carbon emissions in China.

The economics of offshore CO capture is affected by the concentration of CO in the gas/oil stream, the pre-treatment process filtering out impurities [67], [68], and the inherent limitations of the capture materials [69]. Emerging capture technologies, such as polymeric membranes [70], solid absorbent processes, and looping technologies, mitigate some of these challenges in specific industrial applications [71]. Additional innovations combine new CO capture materials with engineering to form flexible and hybrid solutions. In the long term, technologies such as direct air/seawater capture (DAC/DSC) could also be deployed offshore as a complement to offshore bolt-on capture solutions, compensating for residual CO that is uneconomical to capture directly from plant emissions [17].

5.2. Offshore CO transport technology

In China, there is over 165,000 km of gas & oil pipelines in operation; a significant portion of these are offshore to connect gas & oil platforms and to transport gas & oil from offshore fields (e.g., Bohai and Chunxiao) to onshore industrial hubs (e.g., Circum-Bohai Sea Economic Zone and Yangtze River Delta Economic Zone). There are ongoing studies on the potential of repurposing existing gas pipelines for CO transport to build out an offshore CCUS value chain to transport CO [72], [73], rather than having to build new pipelines, to save on capital costs and progressing offshore CCUS projects. However, there are still technological challenges related to retrofits, long-term integrity, and monitoring, which could be resolved through the expertise of the oil and gas industry.

The cost of retrofitting will ultimately depend on the current state of existing pipelines. Differences between natural gas pipelines and CO pipelines are minimal and center on the level of controls required to maintain safety and asset integrity over time, especially with anthropogenic CO [74]. CO pipelines often need more meters, pumps, and controls to maintain their condition. Anthropogenic CO in addition is more likely to contain corrosive contaminants [74], which would need to be controlled with corrosion-resistant pipeline materials or through additional purification measures at loading, to protect asset integrity over time.

Unlike fixed offshore pipeline infrastructure requiring enormous capital outlay, shipping CO in tankers could serve as a near- to mid-term solution to help demonstrate multiple CO storage sites on the annual scale of 1 MtCO [17]. Full-scale CO tankers are like commercial, semi-refrigerated liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers, but any larger vessels would require significant refit. Despite industry hesitancy about the viability of flexible containers and the lack of regulatory frameworks, marine transportation does not present major technical barriers. In contrast, it provides a viable option for long-distance and low-volume CO transport [75].

5.3. Offshore CO storage technology

Several offshore storage sites have been nominated as high-priority storage clusters because of their known physical geological attributes, e.g., Bohai Basin and part of PRMB [7], [8], [9], [31]. Oil and gas operators in China (e.g., CNOOC) have been collecting subsurface data for decades [76], [77], providing a solid foundation for characterizing potential storage in offshore DOGF or SA [19]. To date, there is an abundance of geospatial data available to characterize basins offshore China, while various technologies and knowledge gaps exist. These gaps include issues related to data availability, interoperability of different data sets, and the ability to model CO behavior over time, which presents technical challenges (Table 6).

Standard methods are first needed to model CO migration and interactions [78] in various rock structures and potential cracking and chemical reactions through the multiple stages of storage (e.g., pre-injection, operation, and post-sealing) [79]. This is important for existing wells, which may be at a higher risk of leakage. In addition, it is difficult to compare disparate data sets of key metrics during site selection and to optimize injection strategies for different storage sites. This requires further research and development on the behavior of hydrocarbons before extraction. Moreover, CO behaves differently in its various phases, which can affect the trapping mechanisms after injection. This phenomenon needs to be carefully studied across the unique rock formations present offshore China, particularly in highly depleted gas/oil fields, e.g., some could exist in the Yinggehai Basin [80] over the next several decades. Finally, the industry lacks a standard set of tools and guidelines to establish safe and cost-effective long-term monitoring of storage sites [79] and thus some cross-project learning and interdisciplinary research would be required [81].

5.4. Offshore CO utilization technology

Most offshore CO use pathways require significant development before they can be fully deployed. Besides the CO storage innovation gaps for CO-EOR, industries in China are also grappling with the deployment of offshore infrastructure and sub-sea technologies. Space and weight limitations on existing offshore platforms limit the viability of large-footprint CO equipment, such as compressors and recycling units. A large centralized CO processing unit could overcome several challenges in single-platform injection, including lower flow quantity, variable flow rate, and physical constraints. This concept needs further exploration to verify its economic and logistic feasibility. While all the components for gas/oil processing are already commercially available, adapting these to sub-sea conditions could be challenging and it would be critical to bringing down the cost.

6. Practical aspects of deployment

Technological innovations are key to minimizing the implementation costs of the offshore CCUS and accelerating the demonstration of the full-chain offshore CCUS [15]. While the underlying deployment of offshore CCUS technology in China is at a pilot scale, uncertainty in cost and performance largely reflects the lack of integrated applications and workable business models of large-scale commercial operations [17], [26]. Grants supporting the construction of commercial-scale offshore CCUS projects promote one-of-a-kind construction that allows for learning, feasibility testing, and risk reduction for future commercial implementations [85]. Coordinated financial and political support will be necessary to create the right conditions for the start-up of the offshore CCUS industry.

6.1. Relevance to nationally determined contribution (NDC)

Achieving the scale of offshore CCUS deployment to deliver maximum decarbonization benefits requires strong governance and support from governments, recipient industries, corporations, and communities. In China, regulation of the offshore disposal of CO and ocean jurisdiction remains unclear, including the development of procedures and standards for undertaking a full-chain offshore CCUS, as well as a concrete legal framework to guide offshore CCUS public participation and consultation [86]. To avoid interaction without rules, associated regulations and laws at the national, provincial, and local levels are expected to be planned on a specific and legitimate mandatory basis before the large deployment of offshore projects [42]. To facilitate the cost-cutting of the offshore CCUS, environmental policy initiatives should be supported by the Chinese government to encourage world-class construction. This is important to guarantee regulated income for service providers on full-chain offshore CCUS components [85], [87].

To make offshore CCUS projects commercially viable, a tax on CO emissions from the offshore oil and gas industry could be introduced by the Government of China. This provides strong revenue and viable incentive, which will draw down the cost of offshore CCUS as that has been introduced by Norway and the United States (45Q tax credit) [88], [89]. While uncertainty exists in all CO pricing systems, the 45Q tax credits allot US$35 ton for CO utilization and US$50 ton for permanent sequestration of CO in geologic reservoirs [87]. It helps companies deliver offshore CCUS solutions to develop supply chains in a coordinated way [86]. If China’s carbon tax were introduced, it should avoid most of CCUS costs for the infrastructural establishment of the supply chain, and let the cost of carbon increase sufficiently to be an important driver for the profitable offshore CCUS business.

The initial development of specialized offshore CCUS projects is an expensive process. For large-scale CO storage below the seabed, detailed geological mapping and site characterization of abandoned drilling and reservoirs are required. This requires substantial investment, which is a disincentive for independent organizations to invest in offshore storage infrastructure and related technologies, particularly when combined with the uncertainty of future revenues. China has large state-owned enterprises, where direct investment can support the first offshore CCUS projects. This could boost deployment, guarantee sufficient investment returns, and help develop the carbon market through procurement policies [18], [89]. In China, an offshore CCUS project is already implemented in the northern South China Sea, which is currently generating valuable information about the cost and operation experience for offshore CCUS and therefore offers opportunities to develop market-based mechanisms that take advantage of existing frameworks for carbon offsets. Future projects can be developed in partnership with those wanting to purchase offsets, whether in the public or private sector, with the chance to make additional contributions from other financial streams [90], [91].

6.2. Economic activities

The offshore CCUS, as a solution to reduce carbon emissions, is considered a commercial activity and maybe a future industry component, while coal-fired power and steel assets present a particular challenge. In east and southeast China, to retire existing power and industrial plants early or repurpose them to operate at lower rates of capacity utilization or with alternative fuels, offshore CCUS is the only alternative. Retrofitting CO capture equipment can enable the continued operation of existing plants and supply chains, but with significantly reduced emissions. It would also help to preserve employment and economic prosperity in the emissions-intensive industrialized coastal regions of the east and southeast while avoiding the economic and social disruptions caused by early retirements. Therefore, to support coal mine and power plant owners and the communities that will be affected, a compensation package would have to stimulate the economy. This could involve novel approaches, such as blended financing whereby a commercial project provides societal benefits plus financial returns to investors, and/or pairing with co-benefits such as reduction of insurance premiums related to carbon isolation, which can help enhance uptake and progression to verification in the coming years (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Key suggestions for accelerating full-chain offshore CCUS development in China concerning components inFig. 4. The differentiation between certain components may not be definitive.

| Components | Key suggestions on accelerating full-chain offshore CCUS in China |

|---|---|

| Feasibility study | 1. Offshore sites can provide electrical generation opportunities through low-carbon technologies, such as wind, waves, and tides. |

| Concept selection | 1. Use the social cost of carbon (SCC) to evaluate China’s offshore CCUS assets. |

| 2. Low-carbon portfolio standard with tradable certificates. | |

| 3. Minimum standards, such as a requirement for offshore CCUS for new facilities beyond 2030. | |

| Definition (FEED) | 1. Use existing or new frameworks to facilitate the identification of offshore CCUS opportunities nationally or sub-nationally. |

| Source-sink data | 1. Confidently assess the storage site for ongoing carbon sequestration. |

| 2. Estimate and publish a confirmed sub-seabed carbon storage inventory. | |

| 3. Provide full offshore storage capacity at the source of carbon emissions. | |

| Identify knowledge gaps | 1. Develop a national sub-sea carbon storage map to estimate the wealth of the offshore CCUS. |

| 2. Understand fluid migration in sub-seabed storage formations and potential pathways. | |

| 3. Estimate the time taken for the offshore CCUS to achieve net-zero emissions. | |

| 4. Assess options and consider the reuse of existing offshore facilities. | |

| Demonstration projects | 1. Fully leverage CO-EOR to balance the investment and financial returns. |

| 2. Develop tools for cost-effective capture, transport, storage, and utilization of CO offshore. | |

| 3. Develop new tools for monitoring CO fluids in the sub-seabed and seawater column. | |

| 4. Develop demonstration projects to highlight successes and failures at the regional deployment level, and to create data sets, information, and outreach for future offshore CCUS projects. | |

| 5. Identify cost-effective pairs of carbon source-sink for the deployment of offshore CCUS pilot projects. | |

| Cross-disciplinary engagement | 1. Develop public, interactive maps of China’s carbon emissions and offshore storage data. |

| 2. Combine measures to improve the suitability of offshore storage and capture capacity to enable carbon source-sink connections. | |

| Policy, legal & regulatory | 1. Fully integrate the offshore CCUS within carbon source-sink policies and mechanisms. |

| 2. Improve standard protocols for accounting for the benefits of decarbonization to improve the feasibility and uptake of carbon credit projects. | |

| 3. Establish a carbon tax credit to lower the cost of the offshore CCUS. | |

| 4. Reduce insurance premiums for the offshore CCUS related to the carbon isolation of the atmosphere. | |

| Carbon markets | 1. Establish blended financing for the CCUS to deliver societal benefits and financial returns. |

| 2. Introduce the carbon trading system. |

To date, state-owned enterprises in China have been major players in the execution of CCUS projects, while they often face incentive opportunities and frameworks to access financing that differ from their private sector counterparts [26]. For private property in the orbit of free initiative, they can conduct activities in an environment of free competition [92]. Such competition in the offshore CCUS can be a priority for accessing the best CO storage locations or a preferred shared offshore CO storage site, such as for CO-EOR. This might guide to develop of industrial hubs with shared CO transport and storage infrastructure, which would open up new investment opportunities and improve the economics of offshore CCUS by reducing unit costs through economies of scale as well as reducing commercial risk and financing costs by separating the capture, transport and storage components of the value chain. To provide guidance and optimize the investment environment of consistent offshore CCUS development, an acceptable risk allocation of commercial debt is expected to be demonstrated, and a standardized financial template should be introduced [26]. Large-scale offshore CCUS projects are complex and expensive, where debt might be available, particularly for early offshore projects where grant funding can help to close a significant financial gap [26].

6.3. Cross-disciplinary engagement

Another major challenge to the development of the offshore CCUS is the problem of coordination. The CO emission sources are scattered in the main industrial clusters of the eastern and southeastern regions, while the offshore geological investigation and exploration are operated by various enterprises, such as large state-owned petroleum companies. In addition, offshore CCUS research and development is carried out by universities and research institutions, and financial support and debt are provided by public sector banks. Therefore, good cooperation and coordination mechanisms among governments, businesses, research organizations, and financial sectors are important to accelerate the development of the offshore CCUS in China.

For the design of offshore CCUS projects, a wide range of procedures and risks must be reviewed and assessed. This involves collaboration in studying the feasibility of storage reservoirs, carbon source-sink database, identifying knowledge gaps, front-end engineering and design (FEED), leakage monitoring, as well as external quality assurance, etc., as mapped in Fig. 4 and summarised in Table 7. In addition, specific non-technical uncertainties related to supply across the chain, regulatory framework, liabilities, financial factors, social acceptability, etc., should be considered. These critical considerations will require a clear regulatory framework. Therefore, continuous research on full-chain offshore CCUS technologies and the development of pilot demonstration offshore CCUS projects should be carefully conducted, which will accelerate incremental steps toward maturing offshore projects and minimizing uncertainties and comprehensive risks [14]. Our current challenge today is to overcome the scientific, technological, financial, social, governance, and policy barriers that currently prevent the widespread deployment of offshore CCUS projects. Particular attention should be given to new offshore CCUS projects, in which the associated technical and financial risks are relatively high, a joint cross-disciplinary development should be considered coinciding risk reduction with offshore CCUS success for long-term commercial adoption and commitment to carbon credits [85].

Fig. 4.

Roadmap of a full-chain offshore CCUS project development model. The timing of the external quality assurance is required by large public projects, from the start of the feasibility study to the start of an offshore CCUS project [93]. There are various linkages and feedback between these development stages. Table 7 provides the main suggestions for those components.

7. Summary and path to 2060

Offshore CCUS as a decarbonization strategy in China is exciting, workable, and indispensable, with the potential to significantly mitigate carbon emissions to the atmosphere, particularly in the coastal regions where onshore geological CO storage is distant or suffering from public opposition. To maintain the uptake and progression of offshore CCUS toward large-scale deployment, suitable incentives and requisite political backing to create a commercial environment and favorable regulations must be included in the national plan. The deployment of large-scale offshore CCUS is complex and must take a range of factors into account, including emission source accounting, geographical spreading of storage sources, technology implementations, project designs, risk assessments, economic effects, financing, social factors, and administrative policies. These complexities are not insurmountable, but they require careful planning and further research, including consideration of how national and subnational policies can better reward long-term sustainable deployment of offshore CCUS to achieve China’s national target of Carbon Neutrality by 2060.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares that there is no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2024ZD1406600, 2024ZD1406604, 2024ZD1406604-11), and the National Science Foundation of Xiamen, China (3502Z202373006). The author would like to thank the reviewers and the editor for their comments and suggestions, which significantly improved the work.

Biography

Jianghui Li(BRID: 08712.00.78155) received his bachelor’s degree in communications engineering from Huazhong University of Science and Technology in 2011 and then joined the Chinese Academy of Sciences as a research assistant. In 2013 and 2017, he received his master’s degree in communications engineering and Ph.D. in electronic engineering from the University of York, UK. After that, he served as a research fellow at the University of Southampton and the National Oceanography Centre, UK. In 2021, he joined Xiamen University as a professor and became a faculty member of the State Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Science (MEL). His current research is focused on offshore CCUS, underwater acoustics and ocean engineering.

References

- 1.Xu S., Dai S. CCUS as a second-best choice for China’s carbon neutrality: An institutional analysis. Clim. Policy. 2021;21:927–938. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li H., Lau H.C., Wei X., et al. CO storage potential in major oil and gas reservoirs in the northern South China Sea. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2021;108:103328. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shan Y., Huang Q., Guan D., et al. China CO emission accounts 2016–2017. Sci. Data. 2020;7(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0393-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou D., Zhao Z., Liao J., et al. A preliminary assessment on CO storage capacity in the pearl river mouth basin offshore Guangdong, China. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2011;5(2):308–317. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou D., Zhao D., Liu Q., et al. The GDCCSR project promoting regional CCS-readiness in the Guangdong Province, South China. Energy Procedia. 2013;37:7622–7632. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou K., Zhang L. Legal challenges of carbon capture and storage in the South China sea region. Mar. Policy. 2017;84:167–177. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou D., Li P., Liang X., et al. A long-term strategic plan of offshore CO transport and storage in northern South China Sea for a low-carbon development in Guangdong Province, China. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2018;70:76–87. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li P., Yi L., Liu X., et al. Screening and simulation of offshore CO-EOR and storage: A case study for the HZ21-1 oilfield in the Pearl River Mouth basin, northern South China Sea. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2019;86:66–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang K., Lau H.C., Liu S., et al. Carbon capture and storage in the coastal region of China between Shanghai and Hainan. Energy. 2022;247:123470. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asian Development Bank, Roadmap for Carbon Capture and Storage Demonstration and Deployment in the People’s Republic of China, Asian Development Bank (2015) 1–88.

- 11.Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China . Science Press; 2019. Roadmap for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage Technology in China; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.China’s first offshore carbon capture project launched, 2021. https://www.offshore-energy.biz/chinas-first-offshore-carbon-capture-project-launched/, accessed: 2022-10-31.

- 13.Schrag D.P. Storage of carbon dioxide in offshore sediments. Science. 2009;325(5948):1658–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.1175750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerrard M., et al. Report on October 2020 Workshop. Columbia University; 2020. Accelerating offshore carbon capture and storage - opportunities and challenges for CO removal; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ringrose P.S., Meckel T.A. Maturing global CO storage resources on offshore continental margins to achieve 2DS emissions reductions. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54363-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosa M.B., de Araújo Cavalcante J.S., Miyakawa T.M., et al. Offshore Technology Conference, OnePetro. 2018. The giant Lula field: World’s largest oil production in ultra-deep water under a fast-track development. [Google Scholar]; pp. OTC–29043–MS

- 17.OGTC . Technology Driving Transition; 2020. Closing the Gap Technology for a Net Zero North Sea; pp. 1–236. [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Energy Agency Special report on carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS in clean energy transitions) Energy Technol. Perspect. 2020;2020:1–174. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu L., Wang J., Tian D., et al. The 32nd International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, OnePetro. 2022. Innovation conceptual design on carbon neutrality deepwater drilling platform. [Google Scholar]; Pp. ISOPE–I–22–199

- 20.Brus M. Legal Design of Carbon Capture and Storage; Developments in the Netherlands from an International and EU Perspective. vol. 10. 2009. Challenging complexities of CCS in public international law; p. 41. (Energy & Law). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michener A. IEA Clean Coal Centre CCC/190 ISBN. 2011. CCS challenges and opportunities for China; pp. 978–992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y., Qu S., Cai B., et al. Mapping global carbon footprint in China. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15883-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Y., Guo H., Liao C., et al. The study on prospect and early opportunities for carbon capture and storage in Guangdong Province, China. Energy Procedia. 2013;37:3221–3232. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li P., Zhang Y., Zhou D., et al. Geological characterization and numerical modelling of CO storage in an aquifer structure offshore Guangdong Province, China. Energy Procedia. 2018;154:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 25.China: CO country profile, 2022, https://ourworldindata.org/co2/country/china, accessed: 2022-10-31.

- 26.International Energy Agency . IEA Publications; 2016. 20 Years of Carbon Capture and Storage: Accelerating Future Deployment; pp. 1–115. [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Energy Agency . Energy Technology Perspectives 2020. 2020. Special report on carbon capture utilisation and storage; pp. 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Energy Agency, Energy Technology Perspectives 2020(2020) 1–400.

- 29.Hao A., Li R., Shi J., et al. Suitability evaluation map of CO geological storage in main sedimentary basins in China and its adjacent sea area. Atlas Geol. Environ. China. 2017;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo J., Wen D., Zhang S., et al. Potential and suitability evaluation of CO geological storage in major sedimentary basins of China, and the demonstration project in Ordos basin. Acta Geol. Sin. - English Edition. 2015;89(4):1319–1332. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahowski R.T., Li X., Davidson C.L., et al. Pacific Northwest National Lab. (PNNL), Richland, WA (United States) 2009. Regional opportunities for carbon dioxide capture and storage in China: A comprehensive CO storage cost curve and analysis of the potential for large scale carbon dioxide capture and storage in the People’s Republic of China; pp. 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li P., Zhou D., Zhang C., et al. Potential of sub-seafloor CO geological storage in northern South China Sea and its importance for CCS development in South China. Energy Procedia. 2013;37:5191–5200. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li P., Zhou D., Zhang C., et al. Assessment of the effective CO storage capacity in the Beibuwan basin, offshore of southwestern PR China. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2015;37:325–339. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu C., Lei S., Chiao C., et al. Injection risk assessment for intra-formational seal geological model in a carbon sequestration application in Taiwan. Greenh. Gases. 2017;7:225–240. [Google Scholar]

- 35.International Energy Agency . IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme; 2020. IEAGHG Meeting Report - 4th International Workshop on Offshore Geologic CO Storage; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei N., Li X., Wang Y., et al. A preliminary sub-basin scale evaluation framework of site suitability for onshore aquifer-based CO storage in China. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2013;12:231–246. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q., Liu G., Liu X., et al. Application of a health, safety, and environmental screening and ranking framework to the Shenhua CCS project. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2013;17:504–514. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webb R.M., Gerrard M.B. Overcoming impediments to offshore CO storage: Legal issues in the United States and Canada. Environ Law. Report. News Anal. 2019;49:10634. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gough C., Mander S., et al. Public perceptions of CO transportation in pipelines. Energy Policy. 2014;70:106–114. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terwel B.W., Harinck F., Ellemers N., et al. Going beyond the properties of CO capture and storage (CCS) technology: How trust in stakeholders affects public acceptance of CCS. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2011;5(2):181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallquist L., Seigo S.L., Visschers V.H., et al. Public acceptance of CCS system elements: A conjoint measurement. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2012;6:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Z., Li Q., Liu L., et al. A large national survey of public perceptions of CCS technology in China. Appl. Energy. 2015;158:366–377. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shackley S., McLachlan C., Gough C. The public perception of carbon dioxide capture and storage in the UK: Results from focus groups and a survey. Clim. Policy. 2004;4(4):377–398. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallquist L., Visschers V.H., Siegrist M. Impact of knowledge and misconceptions on benefit and risk perception of CCS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44(17):6557–6562. doi: 10.1021/es1005412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zero Emissions Platform, The Costs of CO Capture, European Technology Platform for Zero Emision Fossil Fuel Power Plants(2011a) 1–81.

- 46.Zero Emissions Platform, The Costs of CO Transport, European Technology Platform for Zero Emision Fossil Fuel Power Plants(2011b) 1–54.

- 47.Zero Emissions Platform, The Costs of CO Storage, European Technology Platform for Zero Emision Fossil Fuel Power Plants(2011c) 1–42.

- 48.Zero Emissions Platform, The Costs of CO Capture, Transport and Storage, European Technology Platform for Zero Emision Fossil Fuel Power Plants (2011d) 1–50.

- 49.D. Zhou, Y. Zhang, S.R. Haszeldine, Engineering requirements for offshore CO transportation and storage: A summary based on international experiences, UK-China (Guangdong) CCUS Centre(2014) 1–64.

- 50.Rubin E.S., Davison J.E., Herzog H.J. The cost of CO capture and storage. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2015;40:378–400. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan J.-L., Xu M., Yang L., et al. How can carbon capture utilization and storage be incentivized in China? A perspective based on the 45Q tax credit provisions. Energy Policy. 2019;132:1229–1240. [Google Scholar]

- 52.S.F. Gassnova, Potential for reduced costs for carbon capture, transport and storage value chains (CCS), The Norwegian Full-Scale CCS Demonstration Project(2020) 1–61.

- 53.Yang B., Wei Y.-M., Liu L.C., et al. Life cycle cost assessment of biomass co-firing power plants with CO capture and storage considering multiple incentives. Energy Econ. 2021;96:105173. [Google Scholar]

- 54.China Ministry of Ecology and Environment, et al. China CCUS Annual Report. China CCUS Roadmap Study; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cost indices, 2022, https://www.toweringskills.com/financial-analysis/cost-indices/#:∼:text=Web accessed: 2022-10-31.

- 56.de Coninck H., Benson S.M. Carbon dioxide capture and storage: Issues and prospects. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2014;39(1):243–270. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang P., Wei Y., Yang B., et al. Carbon capture and storage in China’s power sector: Optimal planning under the 2 C constraint. Appl. Energy. 2020;263:114694. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alcalde J., Heinemann N., Mabon L., et al. Acorn: Developing full-chain industrial carbon capture and storage in a resource-and infrastructure-rich hydrocarbon province. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;233:963–971. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dahowski R.T., Davidson C.L., Li X., et al. Examining CCS deployment potential in China via application of an integrated CCS cost curve. Energy Procedia. 2013;37:2487–2494. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei N., Li X., Dahowski R.T., et al. Economic evaluation on CO-EOR of onshore oil fields in China. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2015;37:170–181. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang L., Ren B., Huang H., et al. CO-EOR and storage in Jilin oilfield China: Monitoring program and preliminary results. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015;125:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghanbari S., Mackay E., Pickup G. Offshore Technology Conference Asia. 2016. Comparison of CO-EOR performance between offshore and onshore environments; pp. 762–776. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wei Y., Yang W., Caro J., et al. Dense ceramic oxygen permeable membranes and catalytic membrane reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;220:185–203. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vega F., Baena-Moreno F., Fernandez L.M.G., et al. Current status of CO chemical absorption research applied to CCS: Towards full deployment at industrial scale. Appl. Energy. 2020;260:114313. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang J., Xu S. CO capture RD&D proceedings in China Huaneng Group. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2014;1(1):129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Interlenghi S.F., de Pádua F.S.R., de Medeiros J.L., et al. Low-emission offshore gas-to-wire from natural gas with carbon dioxide: Supersonic separator conditioning and post-combustion decarbonation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019;195:1334–1349. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khraisheh M., Almomani F., Walker G. Solid sorbents as a retrofit technology for CO removal from natural gas under high pressure and temperature conditions. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fosbøl P.L., Gaspar J., Ehlers S., et al. Benchmarking and comparing first and second generation post combustion CO capture technologies. Energy Procedia. 2014;63:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neele F., de Kler R., Nienoord M., et al. CO transport by ship: The way forward in Europe. Energy Procedia. 2017;114:6824–6834. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peletiri S.P., Rahmanian N., Mujtaba I.M. CO pipeline design: A review. Energies. 2018;11(9):2184. [Google Scholar]

- 71.A. Doyle, Aker solutions to provide carbon capture technology to waste-to-energy plant, 2019. https://www.thechemicalengineer.com/news/aker-solutions-to-provide-carbon-capture-technology-to-waste-to-energy-plant/, accessed: 2022-10-31.

- 72.Roussanaly S., Brunsvold A.L., Hognes E.S. Benchmarking of CO transport technologies: Part II—Offshore pipeline and shipping to an offshore site. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2014;28:283–299. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brownsort P.A., Scott V., Haszeldine S.R. Reducing costs of carbon capture and storage by shared reuse of existing pipeline–case study of a CO capture cluster for industry and power in Scotland. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2016;52:130–138. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Serpa J., Morbee J., Tzimas E. Technical and economic characteristics of a CO transmission pipeline infrastructure. JRC. 2011;62502:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raza A., Gholami R., Rezaee R., et al. CO storage in depleted gas reservoirs: Astudy on the effect of residual gas saturation. Petroleum. 2018;4(1):95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang L., Ren S., Zhang Y., et al. Canadian Unconventional Resources and International Petroleum Conference. OnePetro; 2010. CO storage in saline aquifers: Design of a demonstration project to dispose CO associated with natural gas fields in South China Sea. [Google Scholar]; pp. SPE–133975–MS

- 77.Sun Q., Cartwright J., Wu S., et al. 3D seismic interpretation of dissolution pipes in the South China Sea: Genesis by subsurface, fluid induced collapse. Mar. Geol. 2013;337:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aminu M.D., Nabavi S.A., Rochelle C.A., et al. A review of developments in carbon dioxide storage. Appl. Energy. 2017;208:1389–1419. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dot P.B. A Summary of Results from the Strategic UK CO. Pale Blue Dot Energy; 2016. Progressing development of the UK’s strategic carbon dioxide storage resource; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang B., Xiao X., Hu Z., et al. Geochemistry and episodic accumulation of natural gases from the Ledong gas field in the Yinggehai basin, offshore South China Sea. Org. Geochem. 2005;36(12):1689–1702. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Connelly D., Bull J., Flohr A., et al. Assuring the integrity of offshore carbon dioxide storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022;166:112670. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baroudi H.A., Awoyomi A., Patchigolla K., et al. A review of large-scale shipping and marine emissions management for carbon capture, utilisation and storage. Appl. Energy. 2021;287:116510. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hill L.B., Li X., Wei N. CO-EOR in China: A comparative review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2020;103:103173. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jiang K., Ashworth P., Zhang S., et al. Print media representations of carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) technology in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022;155:111938. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schmelz W.J., Hochman G., Miller K.G. Total cost of carbon capture and storage implemented at a regional scale: Northeastern and midwestern United staztes. Interface Focus. 2020;10(5):20190065. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2019.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.International Energy Agency Ready for CCS retrofit: The potential for equipping China’s existing coal fleet with carbon capture and storage. Insights Ser. 2016;2016:1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Folger P.F. Carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) in the United States. Congr. Res. Serv. 2017;1:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 88.H. Herzog, Lessons learned from CCS demonstration and large pilot projects, An MIT Energy Initiative Working Paper(2016) 1–46.

- 89.Lockwood T. IEA Clean Coal Centre; 2018. Reducing China’s coal power emissions with CCUS retrofits; pp. 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sutton-Grier A.E., Moore A. Leveraging carbon services of coastal ecosystems for habitat protection and restoration. Coastal Manag. 2016;44(3):259–277. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Macreadie P.I., Costa M.D., Atwood T.B., et al. Blue carbon as a natural climate solution. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021;2(12):826–839. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Costa H.K., Musarra R.M., Silva I.M.M.e., et al. Legal aspects of offshore CCS: Case study–salt cavern. Polytechnica. 2019;2(1):87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sundset T. GASSNOVA; 2020. Developing Longship - Key Lessons Learned; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]