ABSTRACT

Background

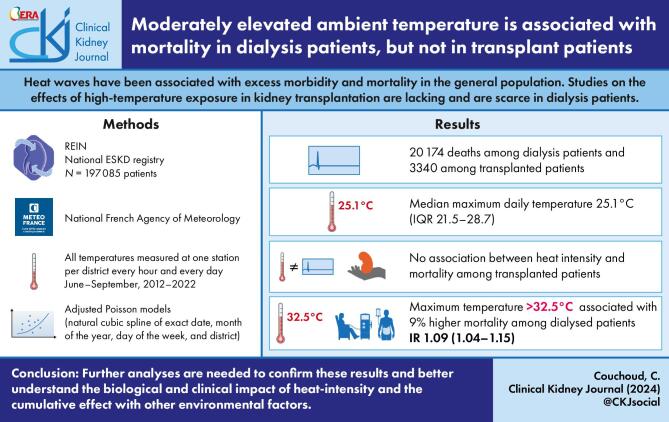

In many parts of the world, heat waves have been associated with excess morbidity and mortality in the general population. Studies on the effects of high-temperature exposure in kidney transplantation are lacking and are scare in dialysis patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between high temperatures and mortality for chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 5 patients treated with dialysis or with a kidney graft in France using various definition of elevated temperature.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, the association between temperature indicators and mortality was analysed with Poisson models taking into account the trend over time and seasonality and possible confounding factors. Models were compared by their AIC. All patients treated with RRT between 2012 and 2022 in France were extracted from the national REIN registry. Various definitions of elevated temperatures were explored based on all temperature measured at one station per district per hour and per day, from June to September during the years 2012–2022 in Metropolitan France.

Results

Between June and September, over the years 2012–2022, temperatures varied from 6.7 to 45.4°C. During this period, 20 174 deaths were recorded among 116 808 dialysis patients and 3340 among 64 531 transplanted patients. A maximum temperature >32.5°C was associated with mortality and an incidence ratio (IR) of 1.09 (1.04–1.15) in the dialysed population. No association was found among transplanted patients.

Conclusions

Further analyses are needed to confirm these results and better understand the biological and clinical impact of heat intensity and the cumulative effect with other environmental factors such as air pollution. More detailed studies on reasons for hospitalizations and causes of death are also planned.

Keywords: dialysis, epidemiology, heat, kidney transplantation, mortality

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What was known:

Heat waves have been associated with excess morbidity and mortality in the general population.

Studies on the effects of high-temperature exposure in kidney transplantation are lacking and are scare in dialysis patients.

This study adds:

This national retrospective cohort study shows an association between heat intensity and mortality in chronic dialysis patients with a relatively moderate threshold at 32.5°C.

However, we found no association between heat intensity and mortality among transplanted patients.

Potential impact:

This field of research is becoming increasingly important at a time of global warming to better identify the most vulnerable populations that need particular protection.

INTRODUCTION

In many parts of the world, heat waves have been associated with excess morbidity and mortality in the general population [1]. More specifically, many studies have shown a positive association between elevated ambient temperatures and/or heatwaves and cardiovascular disease-related mortality or adverse mental health outcomes as well as kidney related morbidity (urolithiasis, acute kidney injury, or urinary tract infection) or mortality [2, 6]. Patients with severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) are particularly vulnerable due to an altered balance of the internal environment caused by renal failure and associated comorbidities [7]. To our knowledge, studies on the effects of high-temperature exposure in kidney transplantation are lacking and are scare in dialysis patients [8, 9].

The definition of a heat wave or the threshold of mean daily temperature varies between studies from the 90th to 98th percentile with no real justification for the choice of threshold, leading to differences in association estimates.

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between high temperatures and mortality for CKD stage 5 patients treated with dialysis or with a kidney graft in France using various definition of elevated temperature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective cohort study with two national French databases.

Temperature data were provided by MétéoFrance, the national French Agency of meteorology. The first file consisted of all temperatures measured at one station per district every hour and every day, from June to September during the years 2012–2022 in Metropolitan France. Owing to some missing temperature data (5%), a single imputation was done using exact date, region, and district. A second file consisted of the identifying heat waves day according to MétéoFrance and severity was defined as the cumulative duration of episodes of temperature above the 97.5th percentile calculated over a reference period (1981–2010) of each district.

Data on patients on kidney replacement therapy were extracted from the national French ESKD REIN registry. Two indicators have been created: the number of deaths in dialysis and the number of deaths with a renal graft, per day in each district of residency.

The work table consists of one line per day, per district, with the maximum temperature for that day in that district, the number of patients treated by dialysis or renal transplant, and the number of patients who died.

The association between temperature indicators and mortality was analysed using a generalized linear mixed model with a Poisson distribution including a random intercept, allowing for overdispersion. The models took into account the trend over time and seasonality (natural cubic spline of the exact date, 44 knots) and possible confounding factors: month of the year, day of the week, and the 96 administrative districts.

Maximum temperature was entered in the models with various approaches: continuous variable, natural cubic spline, in classes, or as a binary item. In the last case, the final threshold was tested for each centile between the 90th and 99th percentiles. Heat wave severity according to MétéoFrance was entered as a continuous variable. Models were compared by their AIC.

Stratified analyses were done in sub-groups according to age and risk factors and across the four climate zones of France: oceanic, degraded oceanic, semi-continental, and Mediterranean climate. Risk factors used were retrieved from the REIN registry: age, obesity (defined as a body mass index over 30 kg/m²), heart failure, coronary heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebral vascular disease, arrythmia, chronic respiratory disease. These were prospectively collected according to a protocol followed by the research assistants of the registry [10].

Results are presented as incidence ratios (IR) with their 95% confidence intervals.

Additional exploratory analyses introduced a heat wave duration (HWD) variable that takes into account the interactions in case of additional effects from persistent periods of extreme heat [11]. In the case where three lag days were used, HWD is equal to Tt × Tt-1 + Tt × Tt-1 × Tt-2; the HWD variable takes the values 0, 1, and 2 depending on how many consecutive days of extreme temperatures there were in before day t. We have explored up to six lag days.

RESULTS

Data from 116 808 patients on dialysis and 64 531 patients with a kidney graft were analysed. Between June and September, over 2012–2022, 20 174 deaths were recorded among dialysis patients and 3340 among transplanted patients and temperatures varied from 6.7 to 45.4°C. The median maximum daily temperature was 25.1°C (IQR 21.5–28.7).

We found no statistically significant association between heat intensity and mortality among transplanted patients, whatever heat indicator was used (Supplementary Table 1). However, we found an association between heat intensity and mortality among patients on dialysis whatever heat indicator was used (Supplementary Table 2). The lowest AIC was found for the model using a threshold at 92th percentile. A maximum temperature >32.5°C was associated with 9% higher mortality [IR 1.09 (1.04–1.15)] in the total population. In the four French climate zones, results were as follows: oceanic 1.06 (0.93–1.20), degraded oceanic 1.10 (0.99–1.21), semi-continental 1.12 (1.02–1.23), and Mediterranean climate 1.08 (0.99–1.18).

Introducing the model maximal temperature from previous days and an interaction term (HWD) did not change the association between maximal heat intensity and mortality on a given day (Supplementary Table 3). No HWD estimates were statistically significant at the 5% level.

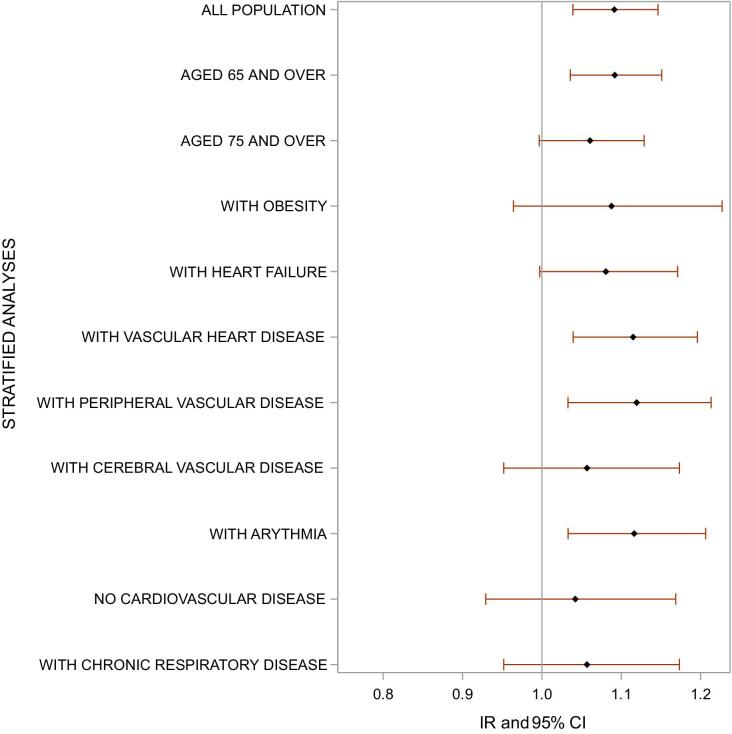

Stratified analyses showed similar results in the population aged 65 years and over: IR 1.09 (95% CI 1.04–1.15) and a non-significant trend in patients aged 75 years and over: IR 1.06 (0.99–1.13, P = .057) (Fig. 1). No association was found in patients with no comorbidities (IR 0.98; 0.8–1.18) or with chronic respiratory disease (1.05 (0.95–1.17) or obesity (1.08 (0.96–1.22). In patients with at least one cardiovascular comorbidity or with diabetes the IRs were 1.11 (1.05–1.17) and 1.10 (1.03–1.18), respectively.

Figure 1:

IR of mortality associated with 32.5°C (92th percentile) in various sub-groups of patients treated by dialysis.

DISCUSSION

We found an association between heat intensity and mortality in chronic dialysis patients with a relatively moderate threshold at 32.5°C (92th percentile). Clinicians are aware that in hot weather dialysis patients have sharply lowered blood pressure, sometimes becoming hypotensive requiring a halt in treatment. Such fluctuations in blood pressure are often poorly tolerated in these patients, who often suffer from cardiovascular comorbidities.

Our results are in accordance with two studies that took place in the USA. In a case-crossover study of 7445 patients on haemodialysis, a 95th-percentile maximum temperature was associated with increased risk of mortality (RR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.01–1.70) [8]. After stratifying by pre-existing comorbidities, extreme heat events were associated with increased risk of mortality among patients living with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or diabetes. A recent cohort study including 945 251 incident patients showed an increased risk of death (HR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.15–1.20) during extreme humid-heat exposure [9].

In transplanted patients, in the absence of any study on the subject, so for the first time, we have not found any association between temperature and mortality. We can argue that these patients are less vulnerable than dialysis patients with less hemodynamic fluctuations. However, our study did not take into account their eGFR or associated comorbidities. In these patients, we might imagine that winter periods and their associated viral infections may be more harmful.

As in any ecological study, the results must be interpreted with caution, without making any causal links. In fact, an ecological bias cannot be ruled out. Summer months are also periods of tension in the healthcare supply due to the vacations of healthcare professionals. Similarly, periods of hot weather are also associated with peaks in air pollution. The present study shows an association between heatwaves and mortality in the very short term. We did not find any evidence of a delayed effect. However, we cannot rule out such an association with morbidity and mortality in the medium term. In the reduction in life expectancy of dialysis patients, the summation of aggression is probably frequent.

This field of research is becoming increasingly important at a time of global warming to better identify the most vulnerable populations that need particular protection [12]. However, further analyses are needed to confirm these results and better understand the biological and clinical impact of heat intensity and the cumulative effect with other environmental factors such as air pollution. More detailed studies on reasons for hospitalizations and causes of death are also planned. Similarly, smaller-scale studies are needed to consider factors such as housing quality and urban heat islands. These studies are more necessary as, in view of what lies ahead, precise guidelines need to be prepared for healthcare professionals and patients alike.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

D.C., conseiller référendaire en service extraordinaire, 6ème Chambre, Cour des comptes, which has enabled the link with MétéoFrance. J.-M.S., directeur adjoint scientifique au sein de la Direction de la climatologie et des services climatiques, MétéoFrance. We thank all the REIN registry participants, especially nephrologists, and professionals in charge of data collection and quality control. Centres participating in the registry are listed in the REIN annual report (https://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/Les-chiffres-du-R-E-I-N ).

Contributor Information

Cécile Couchoud, REIN registry, Agence de la biomédecine, Saint Denis La plaine, France.

Thierry Lobbedez, Service de néphrologie, CHU Caen, France.

Sahar Bayat, Univ Rennes, EHESP, CNRS, Inserm, Arènes - UMR 6051, RSMS (Recherche sur les Services et Management en Santé) - U 1309, Rennes, France.

François Glowacki, Service de néphrologie, CHU Lille, France.

Philippe Brunet, Service de néphrologie, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Marseille, France.

Luc Frimat, Service de néphrologie, CHU Nancy, France.

FUNDING

No funding to declare.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors have participated to the design of the study, the collection of the REIN data, and the redaction of the manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data used for this research were extracted from the REIN registry, coordinated, and supported by the French Biomedecine Agency. The access to national data is regulated by a scientific committee of French Biomedecine Agency that analyses each request, and so cannot be made publicly available due to legal restrictions. Also, access to the data of MétéoFrance is only available on specific request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Faurie C, Varghese BM, Liu Jet al. Association between high temperature and heatwaves with heat-related illnesses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 2022;852:158332. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, Varghese BM, Hansen Aet al. Is there an association between hot weather and poor mental health outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int 2021;153:106533. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Varghese BM, Hansen Aet al. Heat exposure and cardiovascular health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health 2022;6:e484. 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00117-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borg M, Bi P, Nitschke Met al. The impact of daily temperature on renal disease incidence: an ecological study. Environ Health 2017;16:114. [accessed 22 March 2024]. http://ehjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12940-017-0331-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasai F, Roncal-Jimenez C, Rogers Ket al. Climate change and nephrology. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023;38:41. 10.1093/ndt/gfab258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKenna ZJ, Atkins WC, Foster Jet al. Kidney function biomarkers during extreme heat exposure in young and older adults. JAMA 2024;32:333 [accessed 26 June 2024]; https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2820322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arsad FS, Hod R, Ahmad Net al. The impact of heatwaves on mortality and morbidity and the associated vulnerability factors: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:16356. 10.3390/ijerph192316356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remigio RV, Jiang C, Raimann Jet al. Association of extreme heat events with hospital admission or mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e198904. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blum MF, Feng Y, Tuholske CPet al. Extreme humid-heat exposure and mortality among patients receiving dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2024;84:582–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caillet A, Mazoué F, Wurtz Bet al. Which data in the French registry for advanced chronic kidney disease for public health and patient care? Néphrol Thérapeut 2022;18:228. 10.1016/j.nephro.2022.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocklov J, Barnett AG, Woodward A.. On the estimation of heat-intensity and heat-duration effects in time series models of temperature-related mortality in Stockholm, Sweden. Environ Health 2012;11:23. 10.1186/1476-069X-11-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romanello M, McGushin A, Di Napoli Cet al. The 2021 report of the Lancet countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. Lancet North Am Ed 2021;398:1619. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used for this research were extracted from the REIN registry, coordinated, and supported by the French Biomedecine Agency. The access to national data is regulated by a scientific committee of French Biomedecine Agency that analyses each request, and so cannot be made publicly available due to legal restrictions. Also, access to the data of MétéoFrance is only available on specific request.