Abstract

The design of new cost‐effective and water‐resistant acid catalysts is crucial for valorizing aqueous side‐streams to increase the efficiency and competitiveness of bio‐refineries in a sustainable way. In this work, Sn−Ti mixed oxides are prepared via a green and scalable co‐precipitation method. This synthesis procedure allows obtaining homogeneous rutile‐phase Sn−Ti mixed oxides with enhanced textural properties and a higher amount of Lewis acid sites. More importantly, the catalytic behavior of these Sn−Ti mixed oxides is investigated by using an aqueous mixture of C2‐C3 representative oxygenated compounds, closer to real industrial conditions and differing from usual individual probe molecules studies performed even in the absence of water. Catalytic experiments combined and correlated with spectroscopic measurements (i. e., XRD, TEM, FT‐IR with pyridine adsorption‐desorption and N2 adsorption) are performed to better understand the properties of different Sn−Ti catalysts. These materials show promising results in the condensation of light oxygenated compounds present in aqueous fractions. Homogeneous and robust rutile‐phase structures with inherent hydrophobic characteristics turn these Sn−Ti materials into active and highly resistant catalysts capable to transform these low‐value oxygenated compounds into a mixture of hydrocarbons and aromatics useful for blending with automotive fuels, especially under complex acidic aqueous environments and moderate process conditions.

Keywords: Oxygenated compounds, Condensation, Rutile-phase, Tin-titania, Water-resistant

Sn−Ti mixed oxides prepared via co‐precipitation with rutile structure, enhanced textural properties and an optimized distribution of Lewis acid sites are highly active and water‐resistant catalysts for the consecutive condensation of C2‐C3 oxygenated compounds present in aqueous effluents from biorefineries into C5‐C10 low O‐content products, which spontaneously form a separate organic phase that can be further processed into automotive fuels.

Introduction

The valorization of lignocellulosic biomass and its derivatives has become one of the most sustainable alternatives to the use of fossil sources for the production of fuels and chemicals.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] In this context, bio‐oils (obtained from fast pyrolysis processes) are complex mixtures containing water (30–40 wt %) and multiple oxygenated organic compounds in varying concentration[ 4 , 5 , 6 ] characterized by their high reactivity. Therefore, upgrading approaches must be considered to improve their properties, which hinder their storage and direct use as liquid fuels.[ 7 , 8 ] The most common approach comprises bio‐oil hydrotreating at high temperatures and H2 pressures using Mo‐sulfide supported catalysts.[ 9 , 10 ] The major drawbacks of this process include high energy and H2 consumption and low fuel yields because of light oxygenated organic molecules are mainly converted into gases. Recently, an upgrading approach including a liquid‐liquid separation step by water addition has been proposed. [11] Separated organic fractions can be further processed as liquid fuels, whereas aqueous fractions containing C1‐C4 acids (i. e., acetic acid), aldehydes, ketones and alcohols, together with low amounts of heavier compounds are currently considered waste effluents at bio‐refineries.[ 8 , 12 ]

The transformation of these low‐value and water‐soluble oxygenated compounds into a mixture of hydrocarbons and aromatics useful for blending with automotive fuels can be achieved via consecutive C−C bond formation reactions including aldol condensation, ketonization, among others, performed in “one pot”.[ 13 , 14 ] Reaction mechanisms have been studied using propanal and acetic acid as probe molecules over TiO2 and ZrO2 as catalysts.[ 15 , 16 ] Moreover, the use of Ce−Zr mixed oxides in the gas‐phase condensation of small aldehydes at high temperatures (>300 °C) has also been considered. [17] The activity of these catalysts relies on their bi‐functional character, although their activity and stability under complex aqueous mixtures and faithful operation conditions has been barely tested. [18]

In the case of Ti(IV) oxides, the number and nature of acid sites are crucial for this type of aqueous‐phase condensation reactions. Specifically, TiO2 crystalline phase (Figure 1) determines Ti−Ti and O−O distances, which regulate how oxygenated compounds are coordinated to the catalyst surface and have been proved to be decisive in the condensation mechanism of carbonyl type compounds.[ 15 , 16 ] Then, the existence of coordinatively unsaturated Ti−O−Ti sites with intermediate acid‐base strength, together with catalyst geometry features are required for the formation of reactive intermediate species.[ 15 , 16 ] These required Ti−O−Ti sites (probably related to TiO2 structure defects, not shown in Figure 1) are commonly prevalent on anatase but not on rutile TiO2. [19] In this sense, rutile‐TiO2 has always been dismissed due to its poor textural and acid properties, although it has been interestingly claimed as the most hydrophobic TiO2 crystalline phase. [20] Nonetheless, the incorporation of another metal to TiO2 may modify both textural properties and electronic structure, which will have a major effect in increasing the concentration of coordinatively unsaturated Ti4+ sites and creating abundant water‐tolerant Lewis acid sites. [21]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of anatase and rutile TiO2 crystalline structures.

On the other hand, isolated Sn4+ centers present in homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts are broadly known as effective Lewis acid sites with high activity in diverse organic reactions as Baeyer‐Villiger, [22] Meerwein‐Ponndorf‐Verley [23] and isomerization reactions, [24] among others. In the case of solid materials, Sn4+ centers need to be dispersed over supports (i. e. zeolites), which possess higher surface areas, density of acid sites and hydrophobic properties. Nonetheless, zeolites are not adequate catalysts in the aqueous‐phase condensation of oxygenates mixtures, mainly due to their poor structural stability and the presence of high‐functionalized organic compounds in acidic aqueous environments. Notwithstanding, SnO2 catalysts usually crystallize in a rutile‐phase structure with low surface area and reduced number of acid sites. [25]

In this sense, a variety of Sn−Ti mixed oxides in a wide range of Sn−Ti ratios have been synthesized via hydrothermal and sol‐gel methods with homogeneous rutile structure [26] and enhanced textural properties.[ 27 , 28 , 29 ] These materials have been used as proton exchange membranes, in photocatalysis applications[ 30 , 31 , 32 ] and as solid catalysts (i. e., CO oxidation), but their acid characteristics in catalysis, and especially in condensation reactions have never been tested. Moreover, it will be of great interest to prepare these materials via easier and affordable synthesis procedures, not requiring organic templates or hydrothermal conditions.[ 33 , 34 , 35 ]

In this work, and taking into account the remarkable activity of Sn4+ centers as Lewis acid sites in a wide variety of reactions, optimized rutile‐phase Sn−Ti mixed oxides are studied as potential catalysts in the upgrading of light oxygenated compounds present in aqueous effluents obtained by phase separation of pyrolytic bio‐oils. The importance of rutile‐phase structures with hydrophobic characteristics is highlighted. Complex reaction mixtures together with moderate operation conditions employed during this work also differ from usual single molecule catalytic studies even performed in the absence of water.

Experimental Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Materials. The following reagent‐grade chemicals were used in this study: Acetic acid (99.8 %), propanal (97 %), acetol (90 %) and chlorobenzene (99 %) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used as received. Ethanol (99.9 %), methanol (99.9 %) supplied by Scharlau and water (Milli‐Q quality, Millipore) were used as solvents. Tin (IV) chloride pentahydrate and titanium (IV) oxychloride‐HCl acid solution (15 % Ti) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used during Sn−Ti catalysts synthesis. Commercial SnO2, rutile TiO2 and anatase TiO2 samples from Sigma‐Aldrich were dried and used as received. Finally, other commercial supports as ZrO2, CeO2, SiO2 and Al2O3 were also used for comparative purposes.

Preparation Methods

Synthesis of Sn‐Ti mixed oxides via co‐precipitation. Tin (IV) chloride pentahydrate and titanium (IV) oxychloride‐HCl acid solution (15 wt % Ti) were used as metal precursors and dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. After reaching pH=9 by adding a 28 wt % NH4OH aqueous solution, the gel was aged, washed, filtered and dried at 100 °C overnight. Finally, synthesized catalysts were calcined in air at 600 °C for 2 h with a heating rate of 2 °C/min. Samples are named as SnTi‐x, where x is the Sn/(Sn+Ti) molar ratio in the catalyst. Regarding the post‐synthesis thermal treatment (calcination), 600 °C was adopted because this is the required temperature to remove all the water and organic matter derived from metal precursors, as can be seen in the thermogravimetric (TG) analysis displayed in Figure S1. Additionally, Sn−Ti mixed oxides synthesized by co‐precipitation were compared to Sn/TiO2 and Ti/SnO2 catalysts prepared by incipient wetness impregnation (see SI) and the corresponding SnO2 and TiO2 commercial catalysts.

Characterization. XRD patterns were performed on a PANalytical Cubix diffractometer (Cu Kα radiation and graphite monochromator). Raman spectra were achieved in a 1000 inVIa Renishaw spectrometer equipped with an Olympus microscope, a CCD detector and a Renishaw HPNIR laser (λ=514 nm). Surface areas were calculated using the BET method by carrying out N2 adsorption experiments at 77 K using a Micromeritics ASAP 2420 instrument, while BJH method was used to determine pore volumes of the samples. SEM‐EDS was used to obtain the bulk composition and elemental mapping of the catalysts in a JEOL 6300 scanning electron microscope, with an Oxford LIK ISIS detector. Images were obtained with a focused beam of electrons (20 kV) and a counting time of 50–100 s. Moreover, TEM images of representative Sn−Ti mixed oxides were performed in a JEOL JEM‐1010 transmission electron microscope working at 100 kV. Acidity measurements were carried out by experiments of infrared spectroscopy (FT‐IR) using pyridine as probe molecule in a Nicolet710 FTIR spectrometer using self‐supported wafers (10 mg/cm2) diluted with silica. Samples were pretreated in vacuum at 400 °C, prior to pyridine chemisorption. Then, pyridine was desorbed at different temperatures and spectra were collected in each case. Thermogravimetric analysis (TG) was carried out in a Mettler Toledo TGA/SDTA 851 apparatus, using a heating rate of 10 °C/min in an air stream until 800 °C was reached. Finally, elemental analysis (EA) was carried out in a Fisons EA1108CHN−S apparatus.

Catalytic experiments. Reactions were performed in a 12 mL autoclave‐type reactor equipped with a PEEK (polyether‐ethyl‐ketone) interior, magnetic bar, pressure control and a valve for either liquid or gas sample extraction. Reactor was placed over a steel jacket individual support controlled with a temperature close loop system. The initial feed consisted of an aqueous model mixture containing C2‐C3 oxygenated compounds representing aqueous waste streams obtained by phase separation after biomass fast pyrolysis processes. In general, the following aqueous model mixture composition was used: water (30 wt %), acetic acid (30 wt %), propanal (25 wt %), acetol (5 wt %) and ethanol (10 wt %). This choice was made to study the effect of organic acids and water on catalyst peformance without the addition of heavier compounds such as furans or sugars, which may overcomplicate reaction mechanisms. Single compound reactions and different reaction mixtures were also used to confirm catalytic behavior of selected samples. Typically, 3.0 g of aqueous mixture and 0.15 g of catalyst were introduced in the reactor. It was sealed, pressurized at 13 bar of N2, and heated at 200 °C under continuous stirring. Small liquid aliquots (50–100 μL) were taken at different time intervals, filtered off and diluted in 0.5 g of methanol containing 2 wt % chlorobenzene as external standard. These liquid samples were analyzed by a Bruker 430 GC equipped with a FID detector and a capillary column (TRB‐624, 60 m length). Reactants and intermediate products were quantified from GC‐FID response factors calculated by calibration with the use of an internal standard, while long‐chain products were classified in intervals (C5‐C8 and C9‐C10) and group contribution technique was used to predict their corresponding response factors. Product identification was done by GC‐MS (Agilent 6890 N GC System coupled with an Agilent 5973 N mass detector and equipped with a HP‐5 MS, 30 m length capillary column).

Total organic products yield is calculated as the sum of 2‐methyl‐2‐pentenal (2M2P), other C5‐C8 products and C9‐C10 products yield. More information about reaction network and catalytic results quantification can be found in the SI. Based on the initial aqueous model mixture composition, a theoretical maximum attainable total organic products yield is determined, considering: a) 100 % conversion for all reactants; b) acetic acid is equally converted to ethyl acetate and acetone; and c) final products are only C9 compounds. In this ideal scenario, the composition of the final mixture is calculated as follows: 51.3 wt % of water, 19.1 wt % of ethyl acetate, and 29.6 wt % of C9 products. Therefore, results of catalytic experiments are expressed in terms of yields to the main reaction products separately; and total organic products yield, which are calculated and referred to ≈30.0 wt % as the maximum attainable value by considering the initial composition of the aqueous mixture employed in each case.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of Catalysts

Firstly, the prepared SnxTiyO materials were characterized by X‐ray diffraction measurements and their diffraction patterns were compared to commercial SnO2 and RUT‐TiO2 (Sigma Aldrich) samples (Figure 2). Commercial SnO2 (Figure 2A) presents characteristic Bragg peaks of the rutile structure of this metal oxide. [36] X‐ray patterns of co‐precipitated SnxTiyO materials with different Sn−Ti composition indicate that titanium is fully incorporated in the same rutile crystalline phase. [28] Thus, peaks shift is completely consistent with the progressive enrichment in Ti along all the range of composition studied (Figure 2B–E).

Figure 2.

XRD profiles of SnxTiyO catalysts: a) SnTi‐1.00; b) SnTi‐0.74; c) SnTi‐0.64; d) SnTi‐0.33; e) SnTi‐0.18; and f) RUT‐TiO2 (Commercial).

The concomitant variation of unit cell parameters (a and c) of SnxTiyO crystalline structure can be calculated from XRD profiles (Figure 3). This figure shows that homogeneous SnxTiyO materials can be prepared via co‐precipitation even for low Sn/(Sn+Ti) molar ratios (i. e. SnTi‐0.05 and SnTi‐0.09 samples in Figure 3).[ 28 , 37 ] It is worth noting that commercial RUT‐TiO2 catalyst was used as reference, because SnTi‐0.00 prepared by co‐precipitation and calcined under the same conditions (600 °C) was an exception and crystallized into an anatase‐phase TiO2 material.

Figure 3.

Variation of unit cell parameters of SnxTiyO catalysts from X‐ray diffraction measurements: Parameter a (empty squares); and parameter c (full diamonds).

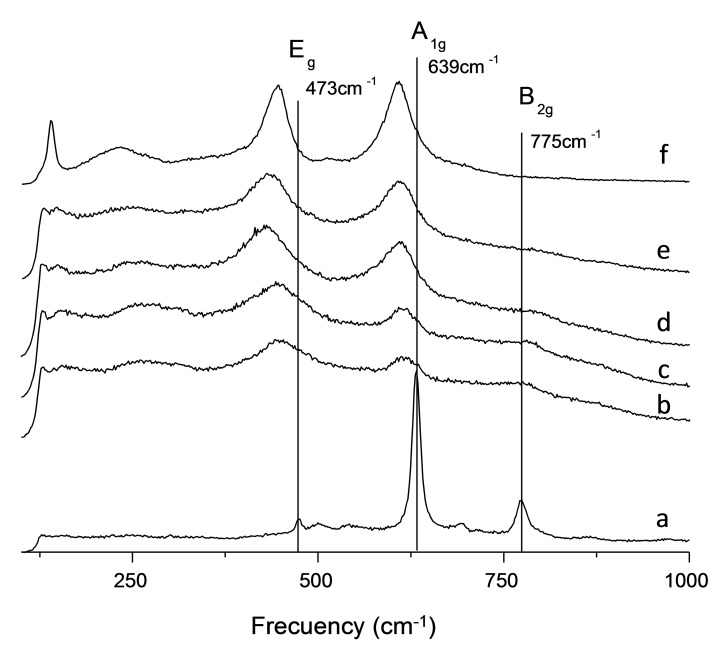

An equivalent behavior can be observed during Raman spectroscopy measurements of these samples. Characteristic signals assigned to rutile‐phase SnO2 are observed for commercial SnO2 catalyst (Figure 4A). Progressive incorporation of titanium into the crystalline structure leads to the disappearance of B2g mode (775 cm−1) and the analogous shift of Eg (473 cm−1) and A1g (639 cm−1) modes in the Raman spectra of all SnxTiyO catalysts studied (Figure 4B–E). Finally, commercial RUT‐TiO2 catalyst shows the characteristic Raman signals of this crystalline structure (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Raman spectra of SnxTiyO catalysts: a) SnTi‐1.00; b) SnTi‐0.74; c) SnTi‐0.64; d) SnTi‐0.33; e) SnTi‐0.18; and f) RUT‐TiO2 (Commercial).

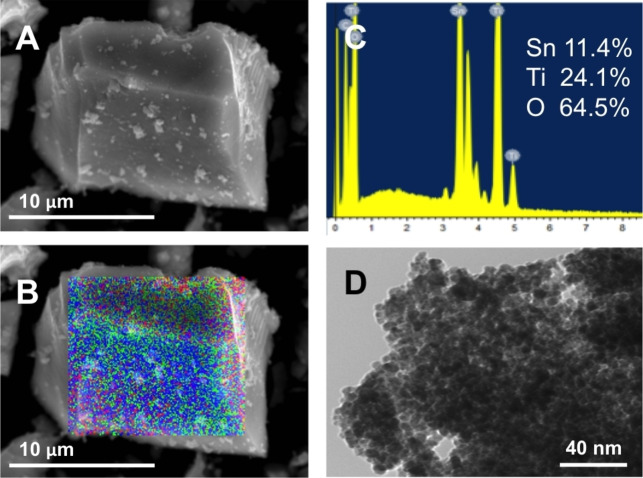

Therefore, the preparation of these catalysts via co‐precipitation allows obtaining homogeneous mixed oxides (elucidated by elemental mapping from SEM‐EDS) in all the range of composition studied (Figure 5B and C). Sn (blue), Ti (green), and O (red) are homogeneously dispersed all along the crystal of the SnTi‐0.33 sample (Figure 5B). Moreover, SnxTiyO mixed oxides show less intense and broad signals in both XRD diffraction (Figure 2B–E) and Raman spectroscopy measurements (Figure 4B–E), which can be ascribed to the formation of nanoparticles. [36] TEM images (Figure 5D) confirm these structural features, where agglomerated Sn−Ti nanoparticles ranging from 5–15 nm can be observed. In this regard, it has been reported that Ti−O−Sn interactions can inhibit the growth of the grains due to the existence of unalike boundaries. [37] In particular, estimated particle size (nm) for SnxTiyO materials from Scherrer's equation and TEM images can be compared in Table 1, where equivalent values were achieved from both methodologies. Moreover, SEM‐EDS and TEM images for all SnxTiyO catalysts are shown in Figure S2 and confirm catalysts homogeneity.

Figure 5.

Electron microscopy images of representative SnTi‐0.33 catalyst: a) SEM image; b) SEM‐EDS mapping image: Sn (blue), Ti (green), O (red); c) SEM‐EDS spectrum; and d) TEM image.

Table 1.

Main textural and physico‐chemical characteristics of SnxTiyO materials.

|

Catalyst |

Surface area (m2/g)[a] |

Pore volume (cm3/g) |

Lewis acid sites (μmolPY/g)[b] |

Particle size (nm) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scherrer equation |

TEM images |

||||

|

RUT‐TiO2 [c] |

2 |

0.00 |

12 |

‐ |

‐ |

|

SnTi‐0.00[d] |

12 |

0.00 |

15 |

‐ |

‐ |

|

SnTi‐0.18 |

87 |

0.15 |

85 |

5 |

10 |

|

SnTi‐0.33 |

116 |

0.16 |

84 |

4 |

8 |

|

SnTi‐0.64 |

118 |

0.13 |

132 |

6 |

7 |

|

SnTi‐0.74 |

103 |

0.12 |

148 |

8 |

8 |

|

SnTi‐1.00[d] |

8 |

0.01 |

23 |

‐ |

‐ |

|

SnO2 [e] |

15 |

0.01 |

29 |

20 |

‐ |

|

Sn/TiO2 |

2 |

0.00 |

‐ |

‐ |

‐ |

|

Ti/SnO2 |

13 |

0.01 |

‐ |

‐ |

‐ |

[a] Calculated from N2 adsorption isotherms (BET method); [b] FT‐IR with pyridine adsorption‐desorption at 150 °C; [c] Commercial RUT‐TiO2 (Sigma Aldrich); [d] TiO2 and SnO2 synthesized via the same procedure used for Sn−Ti mixed oxides; [e] Commercial SnO2 (Sigma Aldrich).

Finally, textural and acid characteristics of these materials were elucidated by N2 adsorption isotherms and FT‐IR experiments with pyridine adsorption‐desorption at 150 °C (Table 1). In this sense, the synthesis of SnxTiyO mixed oxides via co‐precipitation leads to catalysts showing enhanced surface areas (85–120 m2/g), pore volumes (0.12–0.16 cm3/g) and acid properties (85–150 μmolPY/g) compared to commercial catalysts or similar Ti/SnO2 and Sn/TiO2 mixed oxides prepared by incipient wetness impregnation (2–15 m2/g, <0.01 cm3/g and 10–30 μmolPY/g, respectively). These values match or even outperform textural properties reported for similar materials prepared via highly‐priced and challenging scalable synthesis methods.[ 31 , 38 ] It is also worth noting that co‐precipitated monometallic SnO2 shows similar characteristics than commercial SnO2, whereas co‐precipitated TiO2 catalyst shows an anatase structure with slightly higher surface area and acid properties compared to rutile structures. More interestingly, acid characteristics in these materials completely rely on Lewis acid sites, whereas Brönsted acid sites were barely detected by pyridine adsorption FT‐IR measurements (see Figure S3). Thus, the highest values for Lewis acidity are reached with SnTi‐0.64 and SnTi‐0.74 in agreement with the higher content of Sn in the samples, which favors the presence of Lewis acids sites in the mixed oxide.

Therefore, SnxTiyO preparation via co‐precipitation is essential to obtain homogeneous solid mixed oxides with a higher concentration of Lewis acid sites, adequate for aqueous‐phase condensation reactions of oxygenated compounds.

Catalytic Results

Catalytic Performance of Sn‐Ti Materials in the Condensation of a Mixture of Oxygenated Compounds in Aqueous Phase

Catalytic results of SnxTiyO materials in the consecutive condensation of oxygenated compounds in aqueous mixture containing: 30 wt % H2O, 30 wt % acetic acid, 25 wt % propanal, 10 wt % ethanol and 5 wt % acetol are shown in Table 2. Results are expressed in terms of oxygenated compounds conversion and yields to the main reaction products: ethyl acetate, 2‐methyl‐2‐pentenal, C5‐C8 and C9‐C10 products. A general reaction network (including most representative reaction products) is displayed in Figure 6 to facilitate results discussion. In this regard, acetic acid reacts with ethanol to produce ethyl acetate, whereas it can also generate acetone by reacting with another acetic acid molecule via ketonization reaction. Then, acetone may undergo self‐condensation to produce mesityl oxide and react with propanal and acetol to generate different C5‐C8 products via condensation reactions. Propanal self‐condensation leads to the formation of 2‐methyl‐2‐pentenal (2M2P), one of the main first condensation products in this process. Finally, consecutive condensation (2nd condensation) reactions between reactants, intermediates and first condensation products lead to a range of C9‐C10 final organic products (see also SI).[ 39 , 40 ]

Table 2.

Catalytic results of SnxTiyO materials in the condensation of oxygenated compounds in the aqueous phase.

|

Ti |

1.00 |

0.82 |

0.67 |

0.36 |

0.26 |

0.00 |

4 %Sn/TiO2 |

7 %Ti/SnO2 |

|

|

Sn |

0.00 |

0.18 |

0.33 |

0.64 |

0.74 |

1.00 |

|||

|

Conversion (%) |

Acetic acid |

10.7 |

7.5 |

12.2 |

6.7 |

9.0 |

6.8 |

0.8 |

8.2 |

|

Propanal |

35.2 |

56.4 |

57.8 |

55.7 |

51.9 |

30.9 |

34.8 |

38.1 |

|

|

Ethanol |

41.5 |

42.4 |

38.4 |

41.0 |

38.0 |

36.8 |

37.5 |

28.6 |

|

|

Acetol |

84.4 |

92.4 |

93.1 |

91.1 |

92.6 |

83.2 |

78.9 |

70.4 |

|

|

Products Yield (%) |

Ethyl acetate |

21.3 |

21.5 |

15.6 |

22.6 |

18.2 |

19.5 |

16.8 |

16.0 |

|

2M2P[a] |

13.9 |

17.9 |

18.8 |

19.3 |

16.4 |

15.9 |

13.5 |

13.4 |

|

|

C5‐C8 |

14.1 |

21.3 |

21.4 |

17.4 |

20.3 |

17.2 |

7.9 |

16.1 |

|

|

C9‐C10 |

4.3 |

6.9 |

5.1 |

5.3 |

3.9 |

3.3 |

4.9 |

2.2 |

|

|

Total |

32.3 |

46.0 |

45.3 |

42.0 |

40.7 |

36.4 |

26.3 |

31.7 |

|

|

Carbon balance (%) |

93.5 |

98.8 |

93.4 |

98.7 |

97.4 |

96.9 |

94.5 |

98.7 |

|

Reaction conditions: 3 g of aqueous mixture, 150 mg of catalyst, at 200 °C and 13 bar of N2 for 1 h. [a] 2M2P=2‐methyl‐2‐pentenal.

Figure 6.

Reaction network for the aqueous phase condensation of light oxygenated compounds.

Table 2 shows that co‐precipitated Sn−Ti mixed oxides achieve higher yields to the main condensation organic products. In particular, catalysts containing low amount of Sn (i. e. molar ratio from 0.18–0.33) increase reactants conversion: acetol (≈92 %), propanal (≈58 %), ethanol (≈40 %) and acetic acid (8–12 %). It is worth mentioning that acetic acid conversion via ketonization is limited as harsher reaction conditions are needed to achieve meaningful conversion values. [19] Therefore, higher total organic products yields (sum of first condensation and C5‐C10 products) of 45–46 % are achieved up to 1 h on stream. On the other hand, other Sn−Ti oxides and monometallic oxides (i. e. SnO2 and TiO2) show lower catalytic results, where propanal conversion values below 40 % can only be reached.

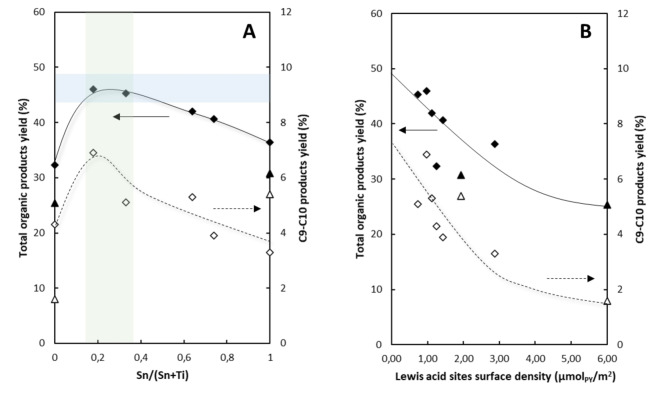

Figure 7A shows that catalyst composition optimization (i. e. 0.18<Sn/(Sn+Ti)<0.33) allows maximizing both C9‐C10 (2nd condensation step products) yield and total organic products yield, when results are analyzed at 1 h of reaction. These results can be directly correlated to Lewis acid sites surface density (Figure 7 B), where the formation of organic products increases when Lewis acid sites are widely spread on the catalyst surface. Moreover, catalytic results of SnxTiyO materials were compared to commercial SnO2 and RUT‐TiO2 oxides and other commercial materials traditionally used as catalysts in these processes including CeO2, ZrO2, SiO2 and Al2O3 materials (Table 3). Most of these catalysts show low total organic products yield when tested in the same reaction conditions. Differently, CeO2 displays high propanal conversion and excellent acetic acid conversion, but cerium acetate species are formed causing the total dissolution of the catalyst under these process conditions.

Figure 7.

A) Sn/(Sn+Ti) composition and B) Lewis acid sites surface density (μmolPY/m2) effect on total organic products and C9‐C10 products yield in the condensation of a mixture of oxygenated compounds in aqueous phase. Co‐precipitated (diamonds) and commercial catalysts (triangles).

Table 3.

Catalytic results of monometallic commercial materials in the condensation of oxygenated compounds in the aqueous phase.

|

ZrO2 |

CeO2 [b] |

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

SnO2 |

TiO2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Conversion (%) |

Acetic acid |

0.0 |

59.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

9.9 |

|

Propanal |

48.9 |

87.2 |

42.7 |

52.1 |

19.2 |

27.2 |

|

|

Ethanol |

43.6 |

47.0 |

43.6 |

30.9 |

20.1 |

26.9 |

|

|

Acetol |

76.9 |

100.0 |

39.2 |

73.8 |

84.0 |

85.2 |

|

|

Product Yield (%) |

Ethyl acetate |

1.9 |

15.3 |

22.0 |

14.2 |

15.0 |

17.8 |

|

2M2P[a] |

10.2 |

30.7 |

13.6 |

11.3 |

13.6 |

9.4 |

|

|

C5‐C8 |

12.4 |

4.3 |

8.4 |

11.4 |

11.8 |

14.4 |

|

|

C9‐C10 |

2.3 |

13.7 |

2.3 |

7.2 |

5.4 |

1.6 |

|

|

Total |

24.9 |

48.7 |

24.3 |

29.9 |

30.8 |

25.4 |

|

|

Carbon balance (%) |

89.0 |

66.6 |

91.0 |

100.0 |

99.5 |

98.3 |

|

Reaction conditions: 3 g of aqueous mixture, 150 mg of catalyst, at 200 °C and 13 bar of N2 for 1 h. [a] 2M2P=2‐methyl‐2‐pentenal. [b] CeO2 catalyst is completely dissolved under these conditions.

Therefore, SnxTiyO materials prepared via co‐precipitation show higher reaction rates at 1 h on stream (Table 4) and the highest yields to the main condensation organic products at 1 h and 7 h, when compared to SnO2 and RUT‐TiO2 commercial materials (see also Figure S4). More interestingly, only co‐precipitated Sn−Ti mixed oxides are able to produce enough heavier products after 7 h (total organic products ≥60 %, Table 4) for these hydrocarbons to become spontaneously separated from water and non‐converted reactants, which facilitates their isolation and subsequent use (see Figure S6). It must be highlighted that these differences become extremely relevant as the use of Sn−Ti mixed oxides allows obtaining higher yields of C5‐C10 products in a separated organic phase, which can be further upgraded, whereas other Sn‐ and Ti‐based materials only generate lower amounts of products that are still forming a single phase even after 7 h on stream. Overall, SnTi‐0.33 allows obtaining a simplified downstream organic product phase enriched with condensation products (38 %), where partition coefficients up to 75–80 % are obtained. Thus, a more efficient process with an atom economy of 0.56 and a ϵ factor of 4.0 is developed.

Table 4.

Reaction rates (at 1 h) and total organic products yield for SnxTiyO at different times on stream.

|

Catalyst |

Reaction rate at 1 h (μmol⋅min−1 g−1) |

Total organic products yield (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 h |

3 h |

5 h |

7 h |

||

|

RUT‐TiO2 [a] |

941 |

25.4 |

40.2 |

46.1 |

48.2 |

|

SnTi‐0.18 |

1449 |

46.0 |

56.1 |

59.6 |

60.9 |

|

SnTi‐0.33 |

1520 |

45.3 |

53.0 |

60.7 |

63.5 |

|

SnTi‐0.64 |

1412 |

42.0 |

56.2 |

58.4 |

60.4 |

|

SnTi‐0.74 |

1373 |

40.7 |

49.0 |

56.6 |

59.5 |

|

SnO2 [b] |

610 |

30.8 |

33.8 |

50.3 |

53.6 |

|

Sn/TiO2 |

961 |

26.3 |

37.8 |

45.5 |

46.4 |

|

Ti/SnO2 |

1049 |

31.7 |

39.5 |

45.3 |

51.4 |

[a] Commercial RUT‐TiO2 (Sigma Aldrich); [b] Commercial SnO2 (Sigma Aldrich). Reaction conditions: 3 g of aqueous mixture, 150 mg of catalyst, at 200 °C and 13 bar of N2 for 1–7 h.

Acetic Acid and H2O Effect on the Catalytic Performance of Sn‐Ti Materials in Light Oxygenates Condensation Reactions

Higher reaction rates and total products yields shown by co‐precipitated SnxTiyO materials are directly related to their enhanced textural and acid properties (Table 1). In particular, higher surfaces areas and pore volumes (interparticle mesoporosity formed due to small nanoparticles agglomeration) favor a higher accessibility of reactants to actives sites. Moreover, a larger number of Lewis acid sites are better dispersed on the catalyst surface. In fact, the correct distribution of acid sites (density of acid sites, expressed as μmolPY/m2) has been found to be a key feature in aqueous‐phase condensation reactions (Figure 7B and Figure S5).[ 28 , 29 ]

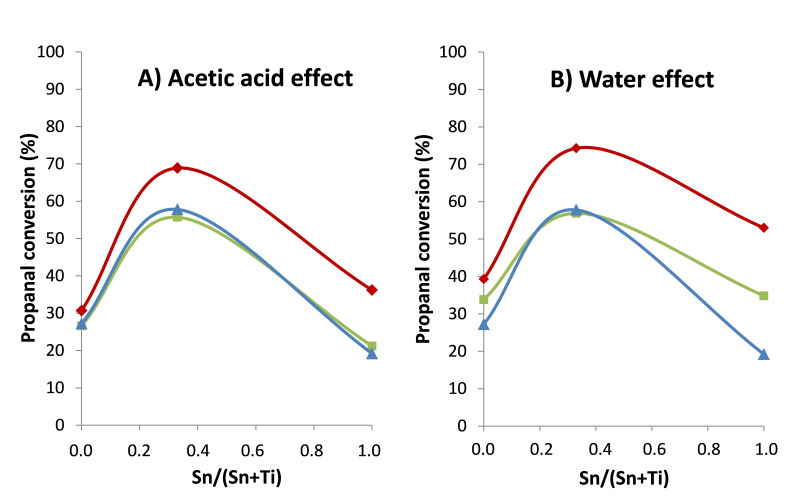

From this point, additional experiments were carried out in order to obtain further information about water and acetic acid effect on the conversion of light oxygenated compounds for this type of materials. On one hand, three different scenarios were considered to study acetic acid effect on propanal conversion: a) propanal aldol condensation in an ethanol/H2O system; b) 30 wt % of acetic acid was added to the previous medium; and c) the initial reference aqueous model mixture was used.

High propanal conversion (69 %) was reached in only 1 hour when SnTi‐0.33 was used in the absence of acetic acid in the reaction medium (Figure 8A), while propanal conversion slightly decreased (16 % decay) when 30 wt % of acetic acid was added. It is worth noting that the presence of acetic acid had a bigger impact on SnO2 (SnTi‐1.00) catalyst (i. e. 47 % decay), whereas RUT‐TiO2 catalytic activity was minimally affected (i. e. 11 % decay). Catalytic results for all materials were barely modified when the initial model aqueous mixture was used compared to the second scenario.

Figure 8.

Effects of acetic acid (A) and water (B) on propanal conversion for different SnxTiyO catalysts. Scenario (a) (red diamonds); scenario (b) (green squares); and scenario (c) (blue triangles). Reaction conditions: 3 g of mixture, 150 mg of catalyst, at 200 °C and 13 bar of N2 for 1 h.

On the other hand, the effect of water was also studied. In this context, three different scenarios were considered: a) water was eliminated and relative concentration of all reactants was kept constant; b) water was replaced by ethanol; and c) the initial reference aqueous model mixture was used.

In this case, the highest propanal conversion (74 %) was again reached in only 1 h when SnTi‐0.33 was used in the absence of water (Figure 8B). Propanal conversion slightly decreased (22 % decay) when a higher concentration of ethanol was added, while esterification reactions were maximized, whereas no further detrimental effects were observed when 30 wt % of water was added to the mixture. Both, commercial SnO2 and RUT‐TiO2 showed analogous trends, although in these cases, the addition of water led to worse catalytic results compared to the Sn−Ti mixed oxide (64 % and 31 % decay, respectively).

In this regard, water effect on total organic products yield (%) for the whole SnxTiyO series of catalysts was further studied. Figure 9 shows that RUT‐TiO2 and high Ti‐content SnxTiyO materials approximately maintained their activity when 30 wt % of water was added to the mixture, whereas much stronger adverse effects were observed for high Sn‐content samples and commercial SnO2 catalyst. In this sense, Ti4+ centers demonstrate to have a higher resistance to the presence of water compared to Sn4+ centers in the same rutile‐phase crystalline structure. Thus, taking into account the active sites deactivation behavior in aqueous environments, Sn−Ti catalysts can be categorized as “water resistant” and “non‐waterproof” materials. These results can be explained by the blocking of the catalyst surface by water adsorption and correlate to DFT calculations in literature, which show that Sn‐rich systems present higher water adsorption enthalpies and a higher H2O binding energy at monolayer and high coverages.[ 41 , 42 ]

Figure 9.

Water effect on the total organic products yield (%) vs Sn/(Sn+Ti) composition for different SnxTiyO catalysts. Reaction conditions: 3 g of mixture, 150 mg of catalyst, at 200 °C and 13 bar of N2 for 1 h.

These experiments also allow explaining previous results using more complex aqueous mixtures in detail, as catalytic results can be more easily correlated to textural and acid properties of the materials. On one hand, high Sn‐content SnxTiyO catalysts show a higher concentration of acid sites. Nonetheless, these materials also show lower resistance to water and organic acid addition in the reaction mixture. On the other hand, high Ti‐content SnxTiyO materials possess lower amounts of acid sites, but these are more resistant to the presence of water and organic acids in the media. These balanced characteristics explain why similar reaction rates and total organic products yields were achieved with all SnxTiyO mixed oxides, regardless of catalyst composition.

Moreover, commercial RUT‐TiO2 and in general, SnxTiyO mixed oxides have shown better resistance to the addition of water and acetic acid in the medium compared to other anatase phase TiO2 materials, previously reported in literature under the same reaction conditions. [29]

In this regard, commercial RUT‐TiO2 only showed low propanal conversion (i. e. 39 %) when organic solvents were used, whereas anatase phase TiO2 sample achieved the highest propanal conversion (i. e. 89 %) in these conditions. Nonetheless, when complex aqueous mixtures were employed, similar reaction rates were reached for ANA‐TiO2 and RUT‐TiO2 samples (see Table 4), in spite of rutile TiO2 presenting much lower surface area and acid properties than other TiO2 materials. This data is consistent with previous results in literature, which affirm that rutile TiO2 materials possess better hydrophobic characteristics compared to anatase phase TiO2 catalysts. [20]

More interestingly, SnTi‐0.33 catalyst (with rutile structure and enhanced surface area and acid properties) leads to the best catalytic results among all Ti‐based materials studied; when condensation reactions are performed in aqueous systems and in the presence of organic acids and other oxygenated mixtures. In this sense, the lowest decay effects caused by water and acetic acid addition can be observed on this SnTi‐0.33 material (see results in Table 5 and Figure 10).

Table 5.

Water and acetic acid effects on TiO2 and SnxTiyO catalysts.

|

Catalyst |

Propanal conversion at 1 h[a] |

Decay effect (%) |

Reaction rate at 1 h (μmol⋅min−1⋅g−1)[b] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Water addition |

Acetic acid addition |

|||

|

ANA‐TiO2 |

89 % |

−65 % |

−63 % |

1086 |

|

RUT‐TiO2 |

39 % |

−31 % |

−11 % |

941 |

|

SnTi‐0.33 |

85 % |

−22 % |

−16 % |

1520 |

[a] Reaction mixture: 25 wt % of propanal, 75 wt % of ethanol; [b] Initial reference aqueous model mixture.

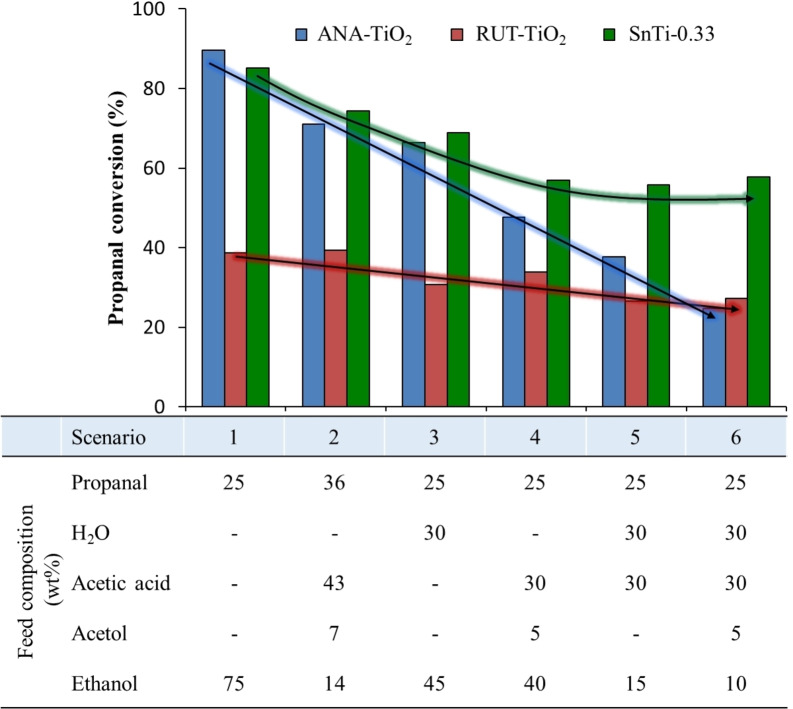

Figure 10.

Evolution of propanal conversion for ANA‐TiO2, RUT‐TiO2 and SnTi‐0.33 catalysts when more complex scenarios are gradually studied. Composition (wt %) of the mixture employed in each case is detailed.

In particular, the resistance of ANA‐TiO2, RUT‐TiO2 and SnTi‐0.33 samples against the combined action of organic acids and water was thoroughly investigated and attained data is depicted in Figure 10. Overall, six different scenarios with gradually increasing complexity (from scenario 1 to 6) have been analyzed. In this sense, commercial ANA‐TIO2 sample showed big detrimental effects when mixtures of oxygenated compounds with the progressive incorporation of acetic acid and water were employed. On the other hand, and due to the inherent hydrophobic characteristics of rutile‐phase structures, RUT‐TIO2 and SnTi‐0.33 catalysts maintained their catalytic activity to a higher extent, even in these more complex environments.

Stability Tests of SnxTiyO Materials in the Condensation of a Mixture of Oxygenated Compounds in Aqueous Phase

Recycling experiments were performed by testing a selected SnxTiyO catalyst (i. e. SnTi‐0.33) to corroborate its resistance under these reaction conditions. Results in terms of reactants conversion and products yield are given in Table 6. Despite its high catalytic activity, especially under complex aqueous environments, SnTi‐0.33 progressively deactivates after three consecutive reuses. Propanal conversion slightly decreased (from 85 % to 78 %) and thus, lower total organic products yields were observed after the second reuse (63 % to 57 %). These results can be partially explained by the carbon deposition (2.8 wt %) on the catalyst surface measured by elemental analysis (Table 7). Nevertheless, neither Sn nor Ti leaching from the solids to the solution was detected along the recycling experiments, while SnTi‐0.33 catalyst structure remained unaltered after all reuses.

Table 6.

Stability results of the reuse of SnTi‐0.33 and CeZrO catalysts in the condensation of oxygenated compounds in the aqueous phase.

|

Catalyst |

SnTi‐0.33 |

CeZrO |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

R0 |

R1 |

R2 |

R0 |

R2 |

||

|

Conversion (%) |

Acetic acid |

7.0 |

7.9 |

8.6 |

17.4 |

3.8 |

|

Propanal |

85.3 |

81.5 |

78.2 |

93.8 |

81.2 |

|

|

Ethanol |

46.1 |

53.5 |

46.2 |

47.8 |

55.3 |

|

|

Acetol |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Product Yield (%) |

Ethyl acetate |

20.2 |

21.6 |

21.8 |

20.3 |

21.0 |

|

2M2P[a] |

30.5 |

28.2 |

26.4 |

36.7 |

28.0 |

|

|

C5‐C8 |

16.7 |

16.6 |

15.3 |

6.7 |

8.0 |

|

|

C9‐C10 |

16.1 |

15.7 |

15.8 |

25.3 |

21.7 |

|

|

Total |

63.3 |

60.5 |

57.5 |

68.7 |

57.7 |

|

|

Carbon balance (%) |

95.8 |

95.4 |

95.8 |

93.0 |

98.0 |

|

Reaction conditions: 3 g of aqueous mixture, 150 mg of catalyst, at 200 °C and 13 bar of N2 for 7 h. [a] 2M2P=2‐methyl‐2‐pentenal. Reference and R0: 1st use; R1: 2nd use and R2: 3rd use.

Table 7.

Characterization of SnTi‐0.33 and CeZrO catalysts after their use in aqueous‐phase condensation reactions by elemental analysis (EA) and ICP measurements.

|

Catalyst |

EA (R2) |

Metal Lost |

|---|---|---|

|

SnTi‐0.33 |

2.8 % |

Non detected |

|

CeZrO |

4.8 % |

>30.0 % |

|

CeO2 |

‐ |

100.0 % |

It is worth noting that in all cases solids were merely separated and washed repeatedly with methanol after their use in reaction. Finally, after drying at 100 °C overnight, the catalysts were tested again in the condensation of oxygenated compounds present in the aqueous model mixture. In this sense, different solvents and heat‐treatment conditions could be applied in order to improve their stability in these processes. Moreover, the interaction of oxygenated compounds present in aqueous mixtures with these rutile‐phase materials should be further studied to increase their resistance in complex reaction media. These experiments should include additional model compounds such as furans, phenols or hydrolyzable sugars, which may also affect both performance and stability of acid heterogeneous catalysts employed in this type of reactions.

Notwithstanding, Sn−Ti mixed oxides still show better resistance under these reaction conditions than other catalysts widely employed in literature in this type of reactions, such as CeZrO mixed oxides. Table 6 shows that CeZrO catalytic activity strongly decays (>10 %) after two consecutive reuses (R2), this behavior being mainly attributed to a stronger carbon deposition (4.8 wt % measured by EA) and an evident partial leaching of Ce actives sites in CeZrO material (Table 7). [28] In addition, a complete dissolution of Ce species was observed in the case of a commercial CeO2 catalyst after the first use, which made impossible to recover the solid and carry out the consecutive catalytic recycling experiments.

Conclusions

There is a growing need in the design of new heterogeneous acid catalysts capable to operate under bio‐refineries process requirements for side‐streams valorization: complex aqueous environments and moderate reaction conditions. In this sense, Sn−Ti mixed oxides can be synthesized via a green and cost‐effective method as co‐precipitation. This synthesis procedure allows obtaining homogeneous rutile‐phase mixed oxides with enhanced textural properties and an optimized distribution of Lewis acid sites. These Sn−Ti mixed oxides have been tested for the first time as catalysts in the aqueous‐phase condensation of light oxygenated compounds by using complex model mixtures under more realistic operation conditions. These materials show better catalytic results in this process than monometallic SnO2 and RUT‐TiO2 catalysts, which are characterized by low surface areas and poor acid properties. More interestingly, and similarly to the behavior commonly attributed to RUT‐TiO2, Sn−Ti mixed oxides with rutile crystalline phase show better resistance to the addition of water and organic acids in the medium compared to other anatase TiO2 materials. Therefore, a larger amount of condensed and aromatic products can be obtained, which genuinely form an organic phase facilitating further downstream processing. In addition, the Sn−Ti mixed oxides remain stable after two consecutive catalytic reuses, their activity decay being lower when compared to that observed for CeZrO reference catalyst. This study may promote further research about water‐resistant acid catalysts with high activity in complex mixtures (including even heavier model compounds), closer to real industrial conditions.

Supporting Information Summary

Synthesis procedure of Sn−Ti mixed oxides via incipient wetness impregnation is detailed. Additional information about reaction mechanism and calculations is shown in Reactions S1‐S4 and Equations S1‐S3, respectively. Thermogravimetric analysis of a SnxTiyO sample (Figure S1), SEM‐EDS and TEM images of SnxTiyO catalysts (Figure S2), FT‐IR of adsorbed pyridine at 150 °C for SnxTiyO catalysts (Figure S3), total organic products yield along different reactions times (Figure S4), correlation between total organic products yield and Lewis acid sites density for rutile‐phase SnTi‐mixed oxides (Figure S5), and images of organic phase formation and product spontaneous separation (Figure S6) are included.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the Spanish Government (PGC2018‐097277‐B−I00 and PID2021‐125897OB−I00) is gratefully acknowledged. A. F−A. thanks “la Caixa‐Severo Ochoa” Foundation for the PhD fellowship. Authors also thank Miriam Parreño‐Romero and the Electron Microscopy Service of Universitat Politècnica de València for their support.

Fernández-Arroyo A., Domine M. E., ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202401761. 10.1002/cssc.202401761

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Huber G. W., Iborra S., Corma A., Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4044–4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tuck C. O., Pérez E., Horváth I. T., Sheldon R. A., Poliakoff M., Science 2012, 337, 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chheda J. N., Huber G. W., Dumesic J. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7164–7183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Resasco D. E., Crossley S. P., Catal Today. 2015, 257, 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stankovikj F., McDonald A. G., Helms G. L., Garcia-Perez M., Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 6505–6524. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iojoiu E. E., Domine M. E., Davidian T., Guilhaume N., Mirodatos C., Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2007, 323, 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grac̀a I., Lopes J. M., Cerqueira H. S., Ribeiro M. F., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 275–287. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Asadieraghi M., Wan Daud W. M. A., Abbas H. F., Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2014, 36, 286–303. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pinheiro A., Hudebine D., Dupassieux N., Geantet C., Energy Fuels. 2009, 23, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bui V. N., Toussaint G., Laurenti D., Mirodatos C., Geantet C., Catal. Today. 2009, 143, 172–178. [Google Scholar]

- 11.D. Radlein, A. Quignard, Methods of upgrading biooil to transportation grade hydrocarbon fuels. US 2014/0288338A1 (2014).

- 12. Stankovikj F., McDonald A. G., Helms G. L., Olarte M. V., Garcia-Perez M., Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 1650–1664. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gaertner C. A., Serrano-Ruiz J. C., Braden D. J., Dumesic J. A., J. Catal. 2009, 266, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pham T. N., Shi D., Resasco D. E., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2014, 145, 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang S., Goulas K., Iglesia E., J. Catal. 2016, 340, 302–320. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang S., Iglesia E., J. Catal. 2017, 345, 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gangadharan A., Shen M., Sooknoi T., Resasco D. E., Mallinson R. G., Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2010, 385, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu K., Wu Y., Chen Y., Chen H., Wang J., Yang M., ChemSusChem. 2016, 9, 1355–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boekaerts B., Lorenz W., Van Aelst J., Sels B. F., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2022, 305, 121052. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aranda-Pérez N., Ruiz M. P., Echave J., Faria J., Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2017, 531, 206–118. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sudarsanam P., Li H., Sagar T. V., ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 9555–9584. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Renz M., Blasco T., Corma A., Fornés V., Jensen R., Nemeth L., Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 51, 4708–4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Corma A., Domine M. E., Valencia S., J. Catal. 2003, 215, 294–304. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moliner M., Roman-Leshkov Y., Davis M. E., Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 6164–6168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Batzill M., Diebold U., Prog. Surf. Sci. 2005, 79, 47–154. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bakar A., Afaq A., Latif S., Iftikhar A., Asif M., Phys. B Cond. Matter. 2021, 619, 413210. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trotochaud L., Boettcher S. W., Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 4920–4930. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dong L., Tang Y., Li B., Zhou L., Gong F., He H., Sun B., Tang C., Gao F., Dong L., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2016, 180, 451–462. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao Y., Hou M., Shao Z., Zhang C., Qin X., Yi B., J. Energ. Chem. 2014, 23, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sharma S., Kumar N., Makgwane P. R., Chauhan N., Kumari K., Rani M., Maken S., Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2022, 529, 120640. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang J., Zhang J., Zou B., Zhang H., Wang J., Schubert U., Rui Y., ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 4265–4273. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spies J. A., Swierk J., Kelly R., Capobianco M. D., Regan K. P., Batista V. S., Brudvig G. W., Schmuttenmaer C. A., ACS Appl. Energ. Mater. 2021, 4, 4695–4703. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sohail M., Baig N., Sher M., Jamil R., Altaf M., Akhtar S., Sharif M., ACS Omega. 2020, 5, 6405–6413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tsoncheva T., Issa G., Genova I., Dimitrov M., Kovacheva D., Henych J., Kormunda M., Scotti N., Tolasz J., Stengl V., Micro. Meso. Mater. 2019, 276, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tsotetsi D., Dhlamini M., Mbule P., Res. Mater. 2022, 14, 100266. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumar V., Singh K., Kumar A., Kumar M., Singh K., Vij A., Thakur A., Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 85, 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shao G. N., Imran S. M., Abbas N., Kim H. T., Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 88, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shi J., Li J., Ma H., Tu D., Zhang Q., Mao W., Yang J., Lu J., Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 570, 151137. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fernández-Arroyo A., Lara M. A., Domine M. E., Sayagués M. J., Navío J. A., Hidalgo M. C., J. Catal. 2018, 358, 266–276. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fernández-Arroyo A., Delgado D., Domine M. E., López-Nieto J. M., Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 5495–5499. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miagava J., da Silva A. L., Navrotsky A., Castro R., Gouvêa D., J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 99(2), 638–644. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Konstanze R. H., Tricoli A., Santarossa G., Vargas A., Baiker A., Langmuir 2012, 28, 1646–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.