Abstract

Cancer risk is influenced by inherited mutations, DNA replication errors, and environmental factors. However, the influence of genetic variation in immunosurveillance on cancer risk is not well understood. Leveraging population-level data from the UK Biobank and FinnGen, we show that heterozygosity at the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-II loci is associated with reduced lung cancer risk in smokers. Fine-mapping implicated amino acid heterozygosity in the HLA-II peptide binding groove in reduced lung cancer risk, while single-cell analyses showed that smoking drives enrichment of pro-inflammatory lung macrophages and HLA-II+ epithelial cells. In lung cancer, widespread loss of HLA-II heterozygosity (LOH) favored loss of alleles with larger neopeptide repertoires. Thus, our findings nominate genetic variation in immunosurveillance as a critical risk factor for lung cancer.

One-Sentence Summary:

Genomic and epidemiological analyses reveal that HLA-II heterozygosity is associated with reduced risk of lung cancer in smokers, underscoring the importance of the host immune system in protecting against cancer.

Lung cancer is currently the leading cause of worldwide cancer mortality (1–3). Although diagnosis rates for advanced-stage disease continue to decline, rates for early-stage disease have increased (2), highlighting the need for research clarifying the factors underpinning lung cancer risk.

Smoking causes lung cancer through DNA damage and other mechanisms, and accounts for more than 80% of lung cancer deaths (4). The role of smoking in lung cancer risk and mortality was initially defined in seminal work by Richard Doll over 70 years ago (5) and validated in countless studies since then, including recent meta-analyses highlighting a severe dose-response relationship between the number of packs smoked and mortality of lung cancer and other diseases (6). Genetic studies have implicated germline genetic variation in lung cancer risk, including mutations in p53, EGFR, and others (1, 7). Together, these studies have established lung cancer as a multifactorial disease with diverse genetic and environmental triggers (8). However, our understanding of the full spectrum of lung cancer risk factors and how they interact remains incomplete—for example, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) explain only a tiny proportion of the genetic variability in lung cancer risk (9). Indeed, there exists wide variability in lung cancer risk even among smokers (9, 10).

The importance of the immune system in conferring protection against pathogens is well-established (11). However, there is a long-standing debate regarding whether the immune system also protects against cancer. The cancer immunosurveillance hypothesis, initially developed by Paul Ehrlich, Lewis Thomas, and Frank Macfarlane Burnet (12–16) posits that lymphocytes constantly survey tissues for neoplastic cells presenting mutation-derived neoantigens, which could trigger an effective immune response that eliminates developing cancers. The cancer immunoediting theory suggests that the immune system plays dual protective and promoting roles in neoplastic transformation (17). Moreover, large cohort studies have noted an increased risk of cancer among solid organ transplant recipients, likely due to ineffective immune control of viruses and infections (18). A plausible interpretation of these seminal studies is that abrogation or differences in the strength of immune surveillance may lead to variations in cancer risk (19–21).

Lung cancer is an exemplary disease for the study of immunosurveillance in cancer, as the healthy lung is among the most heavily T cell-infiltrated tissues (22). Additionally, metastatic lung cancers demonstrate encouraging responses to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) agents targeting T cells via the PD-L1/PD-1 and CTLA-4 axes (23–25), highlighting an important role for neoantigen-driven cytotoxic activity in the disease. Furthermore, key studies investigating the basis for ICB response in lung cancer and other tumor types (26) have shown that the elevated mutation rate caused by smoking (23) promotes increased visibility of neoantigens to cytotoxic T cells (27). Thus, these prior studies suggest that there may exist interactions between smoking and the immune system in the development of lung cancer. Yet, such interactions—and indeed, the role of the immune system in cancer risk in general—are not well understood.

One clue to how the immune system is involved in lung cancer risk has arisen from GWAS, which have implicated individual SNPs and alleles of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I (HLA-I) and II (HLA-II) genes in lung cancer susceptibility (28–30). The HLA genes are highly polymorphic (31) and encode the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, which serve as critical gatekeepers of the adaptive immune response through the presentation of self and foreign antigens for recognition by T cells. Prior work has highlighted the somatic loss of HLA-I as a mechanism of immune evasion in lung cancer (32, 33). Furthermore, HLA class I and class II genotypes influence the oncogenic driver landscape (34, 35). However, whether and how HLA polymorphism interacts with smoking and other risk factors in driving lung cancer risk over time has not currently been addressed.

The heterozygote advantage hypothesis is a foundational principle of the evolution of the HLA system and HLA-mediated protection against disease. According to this hypothesis (36), individuals heterozygous at HLA are afforded greater protection against disease because they present more antigens for T cell recognition via their two different HLA allomorphs than homozygous individuals, and consequently clear infected or neoplastic cells more efficiently. While evidence for heterozygote advantage theory has been demonstrated most clearly in the context of clinical outcomes among individuals who already have the disease—i.e., in delaying progression to AIDs among individuals with HIV (37, 38), clearance of hepatitis B (39), or response to ICB in metastatic cancer (40–46)—whether there exists a protective effect of HLA heterozygosity against the development of lung cancer (or other cancer types) is currently unknown. Such an effect, together with established risk factors such as smoking and age, may underscore HLA heterozygosity and the immune system in general as critical factors in lung cancer risk.

Here we hypothesized that heterozygosity at the HLA genes is associated with reduced lung cancer risk over time, based on the assumption that two different HLA allomorphs will present more neoplastic antigens than a single HLA allomorph (47), thus increasing the likelihood of a cytotoxic reaction against the mutated cells. To test this hypothesis, we leveraged clinical, genetic, environmental, and longitudinal data from two large-scale population biobanks: the UK Biobank (N=391,182) and FinnGen (N=183,163) (Fig. S1). We then employed multiple approaches—including fine-mapping and structural analyses of the peptide-binding groove and genomic profiling of the healthy lung via single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)—to clarify the mechanisms underlying HLA-mediated protection against lung cancer. Finally, we investigated somatic loss of heterozygosity of the HLA-I and HLA-II loci in lung cancer tumors from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort, Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) cohort, and Hartwig Medical Foundation cohorts.

Immunogenetic and demographic characterization of individuals in the UK Biobank and FinnGen

We sought to examine the effects of HLA heterozygosity on lung cancer risk at the population level, defined here as the odds ratio or hazard ratio corresponding to diagnosis or death due to lung cancer as a function of HLA zygosity and other clinical variables. Thus, we first assembled individual-level genetic, clinical, environmental, and longitudinal clinical data from the UK Biobank and FinnGen (48, 49) (Table 1). The UK Biobank and FinnGen are unique in size and scope, with rich longitudinal phenotypic and health-related information available via linkage to medical records for each participant followed over time. In addition, the UK Biobank and FinnGen consist of roughly 500,000 and 350,000 genotyped individuals from the UK and Finland, respectively, including the imputation of genotypes at the classical HLA-I (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C) and HLA-II (HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DPB1, HLA-DPA1) genes. FinnGen in particular has employed a Finnish-specific reference panel for HLA imputation (50). Thus, the UK Biobank and FinnGen are uniquely suited to address whether HLA heterozygosity affects cancer risk.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of lung cancer cases and controls in UK Biobank and FinnGen.

| Characteristic | UK Biobank Full Cohort | UK Biobank Lung Cancer | FinnGen Full Cohort | FinnGen Lung Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total individuals | 391182 | 2468 | 183163 | 3480 |

| Healthy controls | 384928 | 179233 | ||

| Lung cancer subtype | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma (%) | 700 (28.3%) | 801 (23.0%) | ||

| Squamous (%) | 338 (13.7%) | 679 (19.5%) | ||

| Small cell (%) | 192 (7.8%) | 336 (9.7%) | ||

| Other / unknown (%) | 1238 (50.2%) | 1664 (47.8%) | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current (%) | 40674 (10.5%) | 1107 (44.9%) | 50179 (27.4%) | 2464 (70.8%) |

| Former (%) | 135410 (35.0%) | 1035 (41.9%) | 43493 (23.7%) | 666 (19.1%) |

| Never (%) | 211312 (54.5%) | 326 (13.2%) | 89041 (48.6%) | 350 (10.1%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 177259 (54.2%) | 1270 (48.5%) | 89052 (48.6%) | 2724 (78.3%) |

| Female | 210137 (45.8%) | 1297 (51.4%) | 93661 (51.1%) | 756 (21.7%) |

| Age (I.Q.R.) | 58 (50-63) | 67 (63-71) | 63 (49-74) | 75 (70-80) |

Following quality control of HLA genotypes as recommended by the UK Biobank and filtering out any individuals with a cancer diagnosis prior to the start of the UK Biobank study (48) (fig. S2; Materials and Methods), a cohort of 391,182 individuals was identified for further analysis. The primary clinical endpoint of interest in our study was a first diagnosis or death due to lung cancer (defined by ICD-10 codes) over a roughly 14-year follow-up period, with participants recruited between March 2007 and October 2011. We documented 2,468 individuals in the UK Biobank fitting these criteria of lung cancer risk, with the remaining individuals designated as healthy controls (N=384,928) after excluding individuals with missing data (fig. S2). Consistent with prior reports, the most common histological subtypes of lung cancer were adenocarcinoma (N = 700), squamous cell carcinoma (N = 338), and small cell carcinoma (N = 192); with the remaining patients representing other or missing histologies. 86.8% of lung cancer cases recorded as current or former smokers, and the remainder as never-smokers. Gender was roughly evenly split between males and females in both cases and controls. To replicate our findings from the UK Biobank, we assembled lung cancer case and control data from FinnGen (51–53) using the same criteria applied to the UK Biobank. We identified 3,480 lung cancer cases in FinnGen (N = 183,163 total individuals after filtering; fig S3). While the distribution of lung cancer subtypes in FinnGen was similar to that in the UK Biobank, a key difference was the proportion of smokers in each category among lung cancer cases (for instance, 70.8% current smokers in FinnGen compared to 41.8% current smokers in the UK Biobank). The percentage of male lung cancer patients (78.3%) far exceeded the percentage of female patients (21.7%) in FinnGen, while the distribution was more balanced in the UK Biobank.

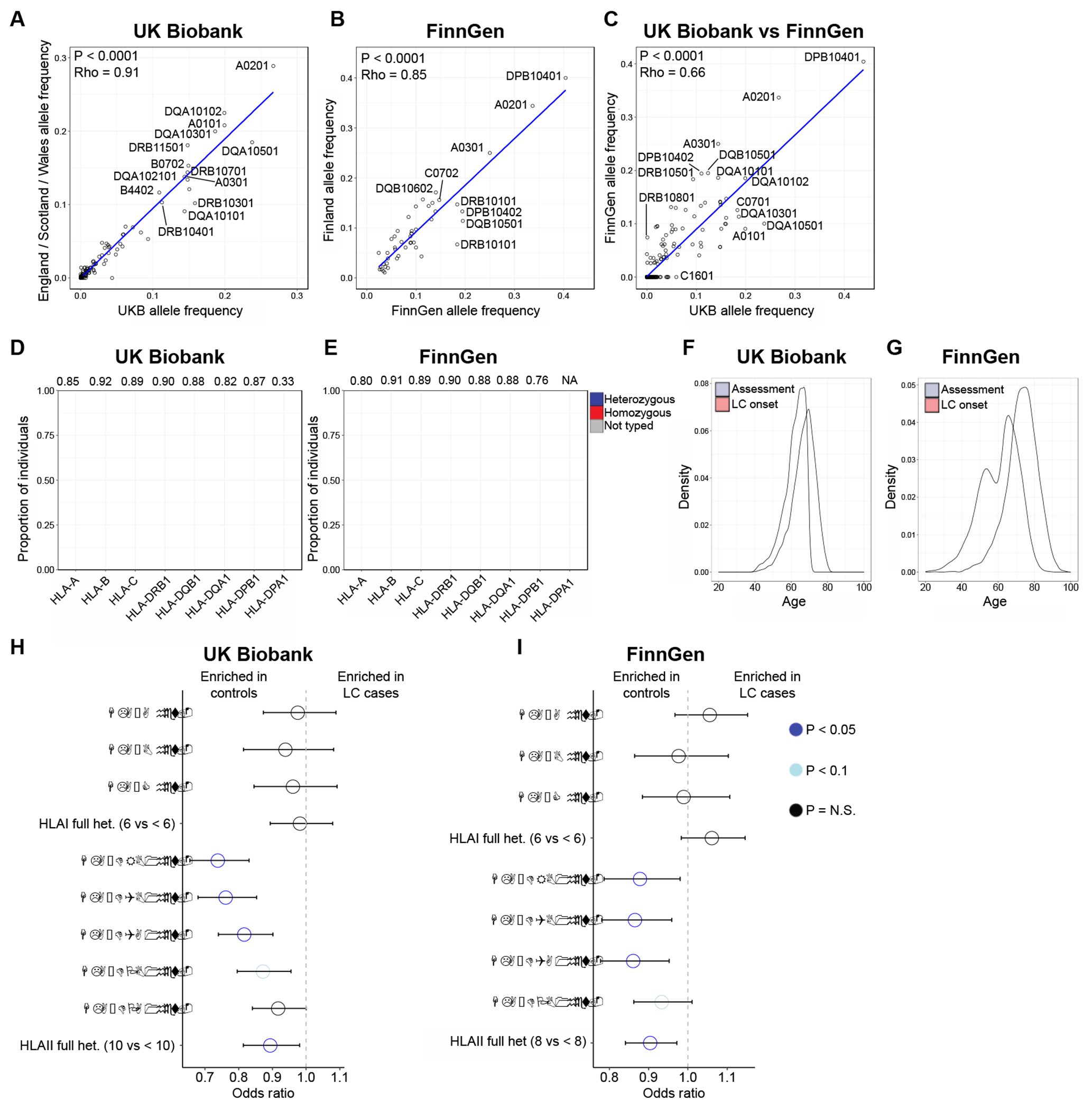

Although several prior studies have used the imputed HLA genotypes provided by the UK Biobank for bespoke analyses (54), we undertook several additional quality checks to validate the quality of imputed HLA genotyping in the UK Biobank. We first compared the allele frequency of 2-field (a.k.a. 4-digit) alleles in the UK Biobank to population-level allele frequencies from the Allele Frequency Net Database (AFND) (55) (Fig. 1A); the frequencies were highly correlated (P < 0.0001; Spearman rho = 0.91), suggesting that allele genotyping in the UK Biobank is representative of the allele genotypes in the wider UK population. We observed similar results comparing allele frequencies in FinnGen to Finnish population allele frequency data (P < 0.0001; Spearman rho = 0.85) (Fig. 1B). We then directly compared allele frequencies in the UK Biobank to those in FinnGen (Fig. 1C)—allele frequencies were generally correlated (P < 0.0001; Spearman rho = 0.66) except for a few HLA-I and HLA-II alleles which approached allele frequencies of up to 10% in the individual cohorts. The strong correlations between allele frequencies in the UK Biobank or FinnGen with the general population—and with each other—were also observed when stratifying the correlation analyses by locus (fig. S4 and tables S1 to S3). Earlier literature demonstrates that HLA allele frequencies differ across geographic locations and across ethnic groups (56). Furthermore, prior comparisons of genetic ancestry and population structure in large cohorts such as gnomAD and FinnGen have shown that the Finnish population is genetically isolated from the rest of Europe. Furthermore, due to relatively recent bottlenecks, the Finnish population is enriched in alleles that have not yet been selected out (49, 57). However, our data suggest that in general, HLA allele frequencies are correlated between the two studies. Consistent with earlier studies (38, 40, 41), we defined heterozygosity at each of the 8 HLA-I and II loci as different alleles at 2-field resolution, since the 2-field allele codes represent variation at the amino acid sequence level of the HLA molecules (58). Consistent with our analyses showing broad concordance of allele frequencies between the two cohorts, we found that the rates of HLA allele heterozygosity between UK Biobank and FinnGen were also highly comparable (Fig. 1, D and E).

Fig. 1. HLA genotype and associations with lung cancer risk in UK Biobank and FinnGen.

(A) Correlation of HLA allele frequencies in the UK Biobank with mean allele frequencies across England, Scotland, and Wales was obtained from the Allele Frequency Net Database (AFND). P-value computed using Spearman correlation. (B) Correlation of HLA allele frequencies in FinnGen with allele frequencies from Finland obtained from AFND. P-value calculated using Spearman correlation. (C) Correlation of HLA allele frequencies in UK Biobank with allele frequencies in FinnGen. P-value calculated using Spearman correlation. (D) Rates of heterozygosity at 4-digit allele resolution in UK Biobank. (E) Rates of heterozygosity at 4-digit allele resolution in FinnGen. HLA-DPA1 genotypes were not imputed in FinnGen and are thus left gray. (F) Distribution of age at onset among lung cancer cases compared to age at first assessment in UK Biobank. (G) Distribution of age at onset among lung cancer cases compared to age at first assessment in FinnGen. (H) Multivariable logistic regression analyses testing heterozygosity at the indicated locus together with all clinical and demographic covariates for associations with lung cancer case/control status in UK Biobank. Forest plots depict odds ratio from logistic regression and 95% confidence interval. (I) Multivariable logistic regression analyses testing heterozygosity at the indicated locus and all clinical and demographic covariates for associations with lung cancer case/control status in FinnGen. Forest plots depict odds ratio from logistic regression and 95% confidence interval.

To provide additional confidence in the robustness of our association results using imputed HLA genotypes, we assessed the concordance of HLA genotypes called from whole-exome sequencing data with imputed genotypes, both assessed in the same individuals from the UK Biobank. We used two independent, well-validated tools for genotyping of HLA-I and HLA-II—HLA*LA (59) and HLA-HD (60)—both of which have strong performance relative to other methods (61). Using these methods, we genotyped HLA-I and HLA-II from 43,000 individuals from the UK Biobank based on whole-exome sequencing data available from blood. The proportion of individuals heterozygous at individual HLA-II loci across the three methods (imputation, exome typed with HLA*LA, and exome typed with HLA-HD) was comparable (fig. S5A) except for heterozygosity at HLA-DQA1 assessed with HLA*LA (proportion of individuals heterozygous = 0.52). The frequencies of individual alleles were also concordant between imputed genotypes and exome genotypes, regardless of whether the exome genotypes were called using HLA*LA or HLA-HD (fig. S5B). We then calculated the concordance between zygosity (either heterozygous or homozygous) defined using the imputed HLA genotypes provided by the UK Biobank and zygosity using genotypes obtained from exome data using HLA*LA or HLA-HD. The concordance rates were 95% or higher for all loci except for HLA-DQA1 (69%) (fig. S5C), suggesting that any significant association results for HLA-DQA1 should be interpreted with caution and replicated in an independent cohort.

HLA-II heterozygosity is associated with reduced lung cancer risk

Having validated the high quality of HLA genotyping in the UK Biobank, we next asked whether HLA heterozygosity provides a reduced lung cancer risk in the UK Biobank using a multivariable logistic regression analysis. We controlled for clinical and demographic covariates that are known to influence lung cancer risk and outcomes in the UK Biobank (62). We reasoned that a multivariable model accounting for all covariates would be especially critical given the drastic difference in age among lung cancer cases in the UK Biobank (median 67) (Table 1 and Fig. 1F) and FinnGen (median 75) (Table 1 and Fig. 1G). Specifically, we fit an independent multivariable logistic regression for each HLA locus testing heterozygosity at the locus as a predictor together with clinical and demographic covariates, including smoking status (Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1H). The outcome was a binary variable indicating diagnosis or death due to lung cancer (N = 2468 in the UK Biobank) or healthy control (N = 384928 in the UK Biobank) (Table 1). In addition to the 8 multivariable models fit for each HLA-I (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C) and HLA-II (HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DPB1, HLA-DPA1) locus, we fit two additional models for maximal heterozygosity at HLA-I (6 alleles vs < 6) and maximal heterozygosity at HLA-II (10 alleles vs. < 10), consistent with the original definition of heterozygote advantage (38) (table S4). This analysis revealed that HLA-II heterozygosity was significantly enriched in controls relative to lung cancer cases, thus associated with reduced risk of lung cancer. We observed a protective effect for heterozygosity at each HLA-II locus and for maximal heterozygosity across all 5 HLA-II loci, but not for HLA-I. The effect of heterozygosity was strongest for HLA-DRB1 (P = 5.19 x 10−7, logistic regression estimate = −0.3, OR = 0.74, OR 95% CI: 0.88 to 1.09) and HLA-DQB1 (P = 2.80 x 10−6, logistic regression estimate = −0.27, OR = 0.76, OR 95% CI: 0.68 to 0.85) (Fig. 1H). We then repeated these analyses using the subset of individuals in the UK Biobank for whom whole-exomes were available. We observed that the protective effect of heterozygosity was also seen when using HLA genotypes called from exomes using both HLA*LA and HLA-HD, despite the much smaller sample size of the exome subset (N = 835 cases, 41708 and 41618 controls for HLA*LA and HLA-HD, respectively) (fig. S6), suggesting that the effect of HLA-II heterozygosity on reduced risk of lung cancer is independent of the genotyping method used. Although genotypes for HLA-DPA1 were not available in FinnGen, we observed a similar protective effect of overall HLA-II heterozygosity (P < 0.05) and for heterozygosity at HLA-DRB1 (P = 0.02), HLA-DQA1 (P = 0.004) and with HLA-DQB1 (P = 0.006) (table S5). HLA-DPB1 heterozygosity did not associate with lung cancer. However, the point estimate was protective and P-value close to significance (P = 0.06), suggesting that larger sample sizes may clarify the association (Fig. 1I). These results suggest that heterozygosity at HLA-II is associated with reduced risk of lung cancer.

We next asked whether HLA-II heterozygosity conferred protection against lung cancer risk over time. We computed follow-up times and censoring for all participants in the UK Biobank as the time from the date of first assessment to the date of diagnosis or death due to lung cancer (Materials and Methods). We first assessed the effect of smoking on lung cancer risk in the UK Biobank using a multivariable Cox regression analysis, treating smoking status as a positive control for our follow-up time and censoring calculations. As expected, current smokers had the highest risk of developing lung cancer in both the UK Biobank (Fig. 2A, fig. S9A) and FinnGen (Fig. 2B, fig. S9B), followed by former smokers. To define the role of HLA-II heterozygosity in mediating lung cancer risk over time, we asked whether heterozygosity afforded additional protection against lung cancer within current, former and never smokers, reasoning that HLA heterozygosity may account for some of the variability in lung cancer risk among individuals with the dominant risk factor. Thus, we assessed the effect of maximal HLA-II heterozygosity (10 alleles vs. < 10) in the UK Biobank and FinnGen within each smoking category (current / former/ never), adjusting for all covariates within each category (i.e., a separate multivariable Cox regression analysis within each smoking category) (fig. S7).

Fig. 2. Maximal HLA-II heterozygosity is associated with reduced lung cancer incidence among smokers in UK Biobank and FinnGen.

(A) Effect of smoking status (current/former/never) on lung cancer incidence in UK Biobank. (B) Effect of smoking status (current/former/never) on lung cancer incidence in FinnGen. (C) Association of maximal HLA-II heterozygosity (10 unique alleles at HLA-DRB1, DQB1, DQA1, DPB1, DPA1) with reduced lung cancer incidence among former smokers in UK Biobank. Heterozygous individuals are denoted by dotted lines; solid lines denote homozygous individuals. (D) Association of maximal HLA-II heterozygosity (8 unique alleles at HLA-DRB1, DQB1, DQA1, DPB1 as DPA1 genotypes were unavailable in FinnGen) with reduced lung cancer incidence among former smokers in FinnGen. Heterozygous individuals are denoted by dotted lines; solid lines denote homozygous individuals. Plots with 95% confidence intervals shown in fig. S9. All P-values were calculated via multivariable Cox regression.

Strikingly, we found that among former smokers, maximal HLA-II heterozygosity was associated with reduced risk of lung cancer (P = 0.006, HR = 0.82, HR 95% CI 0.71-0.94) (Fig. 2C, fig. S9C, and table S6). This result suggests two critical points—first, that HLA-II heterozygosity is associated with reduced lung cancer risk even when adjusting for known clinical and demographic covariates. Secondly, the data suggest that HLA-II heterozygosity accounts for some of the variability in lung cancer risk among smokers. We repeated these analyses in FinnGen and found that maximal HLA-II heterozygosity (8 alleles vs. < 8, as DPA1 genotypes were not available in FinnGen) was associated with reduced risk of lung cancer among current smokers (Fig. 2D, fig. S9D, and table S7). The fact that the protective effect of HLA-II heterozygosity was observed in former smokers in the UK Biobank and current smokers in FinnGen may reflect differences in smoking habits between the two populations, differences in the proportions of current and former smokers among lung cancer cases in each cohort (41.8% current smokers in the UK Biobank, 78.3% current smokers in FinnGen), or a higher proportion of former smokers misclassified as current smokers in FinnGen compared to the UK Biobank (Table 1). Importantly, we did not observe a significant difference in cancer risk between heterozygous and homozygous never-smokers, suggesting a possible interaction between HLA-II heterozygosity and smoking in driving lung cancer risk.

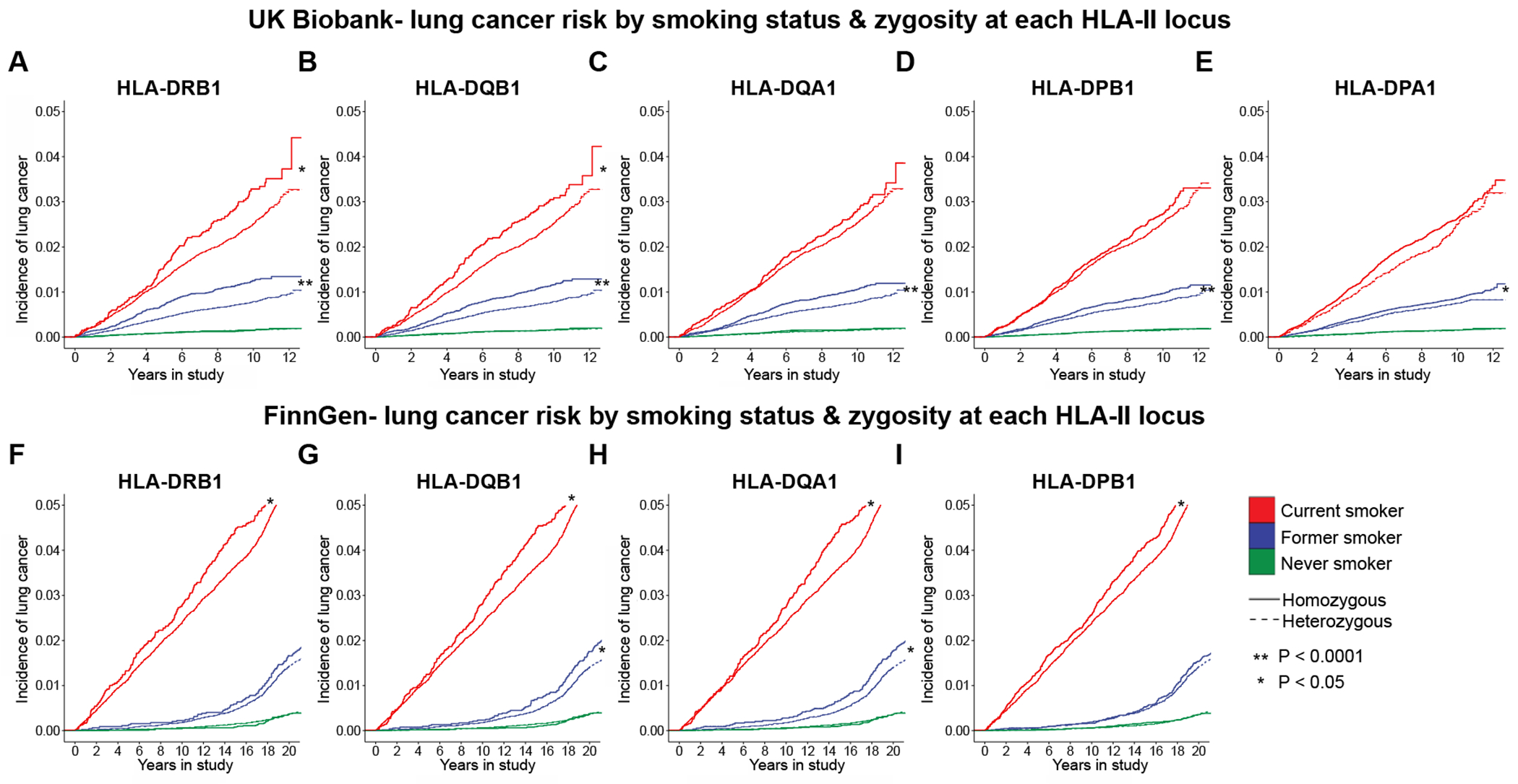

We next assessed the effects of heterozygosity at each HLA-II locus on lung cancer risk over time using multivariable Cox regression analyses in the UK Biobank (table S6). Consistent with our earlier logistic regression analyses (Fig. 1H), the strongest effects of heterozygosity were observed for HLA-DRB1 (former smokers P = 1.47 x 10−7, HR = 0.64, HR 95% CI: 0.55-0.76) (Fig. 3A) and HLA-DQB1 (former smokers P = 1.71 x 10−6, HR = 0.68, HR 95% CI: 0.58-0.79) (Fig. 3B), with a protective effect observed in both current and former smokers. Given the linkage disequilibrium between these two loci, we performed Cox regression analyses testing the effect of HLA-DRB1 heterozygosity among individuals homozygous at HLA-DQB1. This analysis confirmed that the effect of HLA-DRB1 heterozygosity on reduced lung cancer risk was stronger than that of HLA-DQB1 heterozygosity in the UK Biobank (fig. S8, A to C). Interestingly, genetic variation in HLA-DRB1 has been strongly linked to changes in the peripheral TCR repertoire (63) and risk of autoimmune diseases (64, 65). In both cohorts, heterozygosity at both HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1 was associated with reduced risk compared to homozygosity at both (fig. S8, A to F). While the protective effects of HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1 heterozygosity were observed in both current and former smokers, the protective effects of heterozygosity at HLA-DQA1 (Fig. 3C), HLA-DPB1 (Fig. 3D), and HLA-DPA1 (Fig. 3E) were observed only in former smokers (fig. S9, E to I). In general, we replicated the protective effects of heterozygosity at each of the HLA-II loci among smokers in FinnGen (table S7), with DQB1 and DQA1 mediating the strongest effects in both current and former smokers (Fig. 3, F to I, fig. S8, D to F, fig. S9, J to M). We note that while we did not detect any effect of HLA-II heterozygosity in never smokers, the lack of such an association may be due to power, given the much lower number of never smokers compared to current and former smokers in both cohorts. To examine whether the protective effect of heterozygosity was driven by the presence or absence of individual HLA-I or HLA-II alleles, we performed multivariable Cox regression analyses in the UK Biobank and FinnGen controlling for all alleles associated with lung cancer risk, and found that all heterozygosity signals remained significant even after adjusting for the effects of individual alleles, either when testing all individual alleles (fig. S10A to C, tables S8 and S9) or when testing those enriched in individuals fully heterozygous or homozygous at HLA-II (fig. S10D to G, tables S10 and S11). We also observed similar results using Cox regression models unadjusted for any covariates (tables S12 and S13), and when adding up to 20 genetic ancestry principal components to the multivariable Cox regression model (tables S14 and S15). Collectively, these analyses underscore the robustness of the association between HLA-II heterozygosity and reduced risk of lung cancer.

Fig. 3. Heterozygosity at individual HLA-II loci is associated with reduced lung cancer incidence among smokers in UK Biobank and FinnGen.

(A to E) Association of heterozygosity at the indicated HLA-II locus with reduced lung cancer incidence among current and former smokers in UK Biobank. Dotted lines denote heterozygous individuals; solid lines represent homozygous individuals. (F to I) Association of heterozygosity at the indicated HLA-II locus with reduced lung cancer incidence among smokers in FinnGen. Dotted lines denote heterozygous individuals; solid lines represent homozygous individuals. Plots with 95% confidence intervals shown in fig. S9. All P-values were calculated via multivariable Cox regression.

We next used the UK Biobank data to estimate the lifetime risk of lung cancer by age 80 (53) among individuals heterozygous or homozygous at HLA-II using age as the timescale (fig. S11), analogous to prior studies (53, 66) (table S6). We observed striking differences in lifetime risk between smokers heterozygous and homozygous at HLA-II in the UK Biobank; for example, among current smokers homozygosity at HLA-DRB1 was associated with a 13.92% lifetime risk of lung cancer compared to an 10.81% risk among current smokers heterozygous at HLA-DRB1, representing an excess risk of 3.11% (fig. S12). We observed similar trends in FinnGen (table S7), with 26.3% lifetime risk attributed to HLA-DRB1 homozygotes compared to 22.0% for HLA-DRB1 heterozygotes (fig. S13).

To evaluate the potential effect of HLA-II heterozygosity on reduced lung cancer risk in comparison to genetic predisposition conferred by other loci of the genome, we applied a recently developed polygenic risk score (PRS) for lung cancer (67) to both the UK Biobank (fig. S14) and FinnGenn (fig. S15). We evaluated two forms of the PRS, starting in the UK Biobank—one without SNPs in the MHC region (‘PRS no MHC’; fig. S14A), and one with SNPs in the MHC region (‘PRS w/ MHC’, fig. S14B). The HRs for HLA-DRB1 homozygosity was comparable to the HRs for both versions of the PRS: homozygosity DRB1 HR = 1.36 compared to PRS no MHC HR = 1.57, compared to PRS w/ MHC HR = 1.42. As expected, these results suggest that HLA-II homozygosity is associated with lung cancer risk, but not to the same extent as a genome-wide PRS, which includes many more loci. We next asked whether HLA-II heterozygosity remains independently associated with lung cancer risk even after adjusting for the effect of the PRS. Indeed, this was the case regardless of which version of the PRS was used; importantly, none of the HLA-I loci showed significant heterozygosity effects when adjusting for continuous PRS (fig. S14, C to D). Notably, even among individuals with high PRS, HLA-II homozygosity was able to further stratify lung cancer risk (fig. S14 E to N). In particular, even among individuals with high genome-wide PRS, HLA-II homozygosity conferred up to 8.2% additional lifetime risk in current smokers and 2.1% additional lifetime risk in former smokers in the UK Biobank (fig. S14 O to P). We repeated these analyses in FinnGen and observed similar results (Fig. S15). In FinnGen, the combination of PRS high and HLA-II homozygosity conferred up to 9.0% additional lifetime risk in current smokers and up to 2.89% additional lifetime risk among former smokers (fig. S15 O and P). These analyses show that HLA-II heterozygosity is a critical and independent factor associated with reduced risk of lung cancer, even among smokers and individuals with high genome-wide genetic predisposition.

Although we did not observe significance for HLA-I heterozygosity in our logistic regression analyses (Fig. 1), we tested the effects of maximal HLA-I heterozygosity and heterozygosity at each HLA-I locus (fig. S16, A to D and table S6) on lung cancer risk over time using multivariable Cox regression analyses as performed for HLA-II. Curiously, we observed a significant effect of maximal HLA-I heterozygosity and heterozygosity at HLA-C among former smokers in the UK Biobank, but these results did not replicate in FinnGen (fig. S16, E to H and table S7). These data suggest that further studies, perhaps at larger sample sizes, are required to clarify the effect of HLA-I heterozygosity on lung cancer risk.

We further performed subgroup multivariable Cox regression analyses in the UK Biobank to test the effect of HLA-II heterozygosity in individual lung cancer subtypes. First, the effect of smoking alone was significant in all three histologies evaluated and strongest in small cell and squamous carcinoma (fig. S17A), consistent with prior reports (1). Furthermore, our analyses revealed that the protective effect of HLA-II heterozygosity was observed in small cell carcinoma, squamous carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma, with most effects observed in former smokers, consistent with the combined analyses (fig. S17). Moreover, the hazard ratios for HLA-II heterozygosity were lower in squamous (HR range for significant loci 0.49-0.66) and small cell (HR range for significant loci 0.47-0.56) than adenocarcinoma (HR range for significant loci 0.69-0.76) (table S16). Thus, our data may suggest that the protective effect of HLA-II heterozygosity could be attenuated by smoking; that is, the protective effect is strongest in lung cancer subtypes, in which the effect of tobacco is also the strongest. We also observed significant associations between HLA-II heterozygosity and reduced risk of squamous carcinoma in FinnGen (fig. S18, table S17).

We also evaluated the effect of HLA-II evolutionary divergence (HED), a quantitative measure of the antigen presentation capacity of an individual’s HLA-II allomorphs captured by measuring the molecular distance between the peptide binding grooves of each allele (41, 47) on lung cancer risk in the UK Biobank. Among former smokers, we observed a protective effect of HED at HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1 against lung cancer risk when treating HED as a continuous variable and adjusting for all covariates (fig. S19A). We repeated these analyses in FinnGen, and replicated the HED association for HLA-DRB1 among both current and former smokers (fig S19B). These data suggest that granular differences between amino acids within HLA-II peptide binding grooves may be associated with a reduced risk of lung cancer.

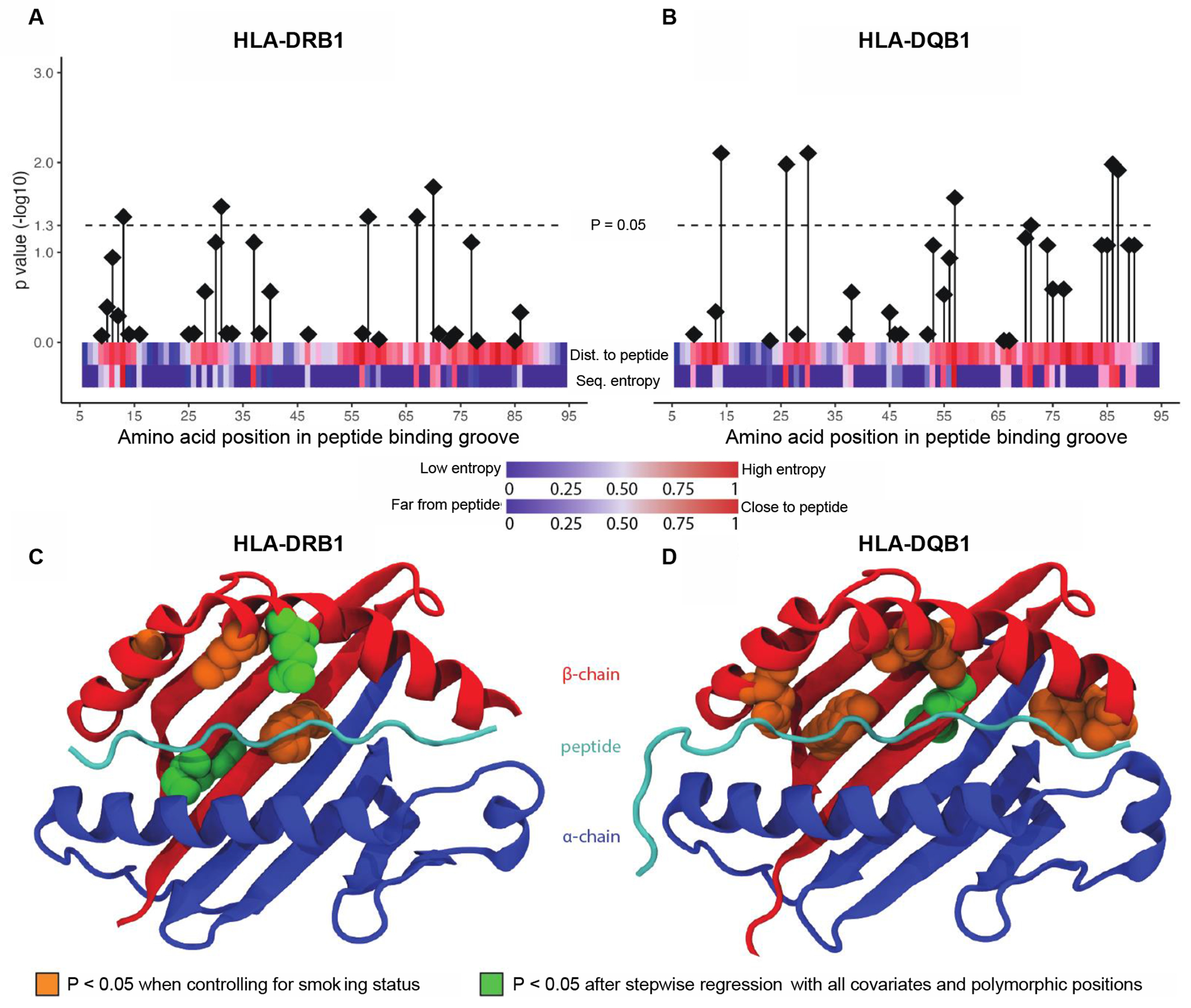

Fine-mapping implicates amino acid heterozygosity within the HLA-II peptide binding groove in reducing lung cancer risk

To explore the relationship between HLA-II heterozygosity, antigen presentation, and lung cancer risk, we sought to perform fine-mapping analyses using the amino acid sequences of the peptide binding groove of HLA-II alleles (Materials and Methods). Indeed, fine-mapping of the peptide binding groove of the MHC has been conducted previously to directly implicate antigen presentation in HIV-1 control (68, 69). To examine the effect of amino acid polymorphisms in the peptide binding groove on lung cancer risk, we first collected the amino acid sequences of the peptide binding grooves of all HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 alleles in the UK Biobank, as heterozygosity at DRB1 and DQB1 mediated the strongest protective effects against lung cancer in the UK Biobank. We then defined the polymorphic positions within the peptide binding groove through sequence entropy analysis, to narrow the peptide binding groove to a core set of polymorphic positions to test for association with lung cancer risk. Our entropy analysis revealed that roughly 33% of the amino acid positions were polymorphic (fig. S20A). We analyzed the average C-α distances between bound peptides and HLA DRB1 and DQB1 protein residues using peptide-MHC crystal structure data from PDB (Materials and Methods and table S18), which showed that polymorphic residues are significantly closer to bound peptides than monomorphic residues (P < 0.01 for HLA-DQB1; P < 0.0001 for HLA-DRB1) (fig. S20, B and C), suggesting their relevance in peptide presentation.

We next tested the set of polymorphic positions defined through sequence entropy analysis for association with lung cancer risk using multivariable logistic regression in the UK Biobank. In standard MHC fine-mapping analysis, amino acid positional diversity within individual HLA alleles is tested for disease associations or quantitative traits (e.g., HIV-1 viral load). Since our interest is in heterozygosity, we adapted MHC fine-mapping to test heterozygosity at each position within the peptide binding groove, defined as two different amino acids at a particular position. We fit a multivariable logistic regression for each position in the peptide binding groove incorporating heterozygosity and smoking status, with a binary outcome representing lung cancer case or control as defined in earlier analyses. This analysis revealed that five positions within the DRB1 peptide binding groove and seven positions within that of DQB1 remained significant after multiple testing corrections with the Benjamini-Hochberg method (Fig. 4, A and B and table S19). Notably, several of the significant positions have been previously implicated in other diseases, e.g. P70 in DRB1, previously associated with rheumatoid arthritis (70), in addition to smoking and Parkinson’s disease (71). We also observed the effect of P57 in DQB1, previously associated with type 1 diabetes (72). A stepwise regression analysis in the UK Biobank incorporating all covariates yielded significance for P31 and P70 in HLA-DRB1 and P14 in DQB1 (Fig. 4, A and B). The significant positions were found to be a median of 7.04 (HLA-DQB1) and 9.04 (HLA-DRB1) angstroms (both in 21st percentile) to bound peptides through quantification and visual inspection of peptide-MHC crystal PDB structures (Fig. 4, C and D). We repeated these analyses in FinnGen, and found that we replicated four associations from the UK Biobank, including DRB1 P70 (fig S21). Altogether, these data implicate antigen presentation together with heterozygosity at both the population level (via differences in allele identity across individuals) and at the molecular level (via differences in amino acid sequence at particular positions in HLA peptide binding grooves) in reduced lung cancer risk. While the association of HLA-II heterozygosity with reduced lung cancer risk in the longitudinal Cox regression analyses implies that variation within the peptide binding groove should also be associated with reduced lung cancer risk, the principal contribution of our fine-mapping analyses is that heterozygosity of specific amino acid positions within the peptide binding groove are themselves associated with reduced lung cancer risk.

Fig. 4. Heterozygosity fine-mapping and structural analyses of HLA-II peptide binding groove amino acid sequences.

(A and B) Associations between heterozygosity at the indicated position of the peptide binding groove of HLA-DRB1 (A) and HLA-DQB1 (B), respectively, and lung cancer risk using a multivariable logistic regression in UK Biobank adjusting for smoking status. The dotted line indicates FDR P = 0.05. Annotation bars indicate polymorphism at the indicated position defined by sequence entropy and distance from peptide based on analysis of representative peptide-MHC crystal structures. (C) Structural visualization of significant amino acid positions from (A) and positions significant after stepwise regression on a representative HLA-DRB1 crystal structure in complex with bound peptide. (D) Structural visualization of significant amino acid positions from (B) and positions significant after stepwise regression on a representative HLA-DQB1 crystal structure in complex with bound peptide.

Single-cell RNA sequencing of the adjacent normal lung reveals that smoking drives upregulation of HLA-II and pro-inflammatory pathways in alveolar macrophages

Our data suggest that HLA-II heterozygosity and smoking interact via antigen presentation to modulate lung cancer risk. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is increased neoantigen presentation due to an elevated mutation rate induced by smoking. A complementary hypothesis is that smoking alters the lung microenvironment to create an inflammatory milieu that favors antigen presentation by the HLA-II allomorphs. To define the molecular effects of smoking on the lung microenvironment, we analyzed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from three lung cancer studies profiling the adjacent normal lung (73–75). Despite these prior studies and others assessing the effect of smoking on the lung tumor microenvironment (76), the effect of smoking on the normal lung microenvironment is unclear. We hypothesized that smoking might modulate the expression of the HLA-II genes in relevant immune cell subsets; such modulation of HLA-II gene expression may promote antigen presentation within an inflammatory milieu created in response to tissue damage by smoking.

We first analyzed scRNA-seq data from the matched adjacent normal lung of 27 individuals (N = 19 smokers, 8 never-smokers) who underwent surgical resection for lung cancer from Leader et al. (73) (Fig. 5, A to C). We used cell type annotations as specified in the original study and noted a large compartment of myeloid cells and alveolar macrophages (Fig. 5A). We first asked whether smoking induces changes in the proportion of cell types in the healthy lung. We directly compared cell type prevalence in smokers vs. never-smokers, accounting for the compositional nature of the data using a Dirichlet multinomial regression adjusting for clinical covariates as used in prior studies (77, 78). This analysis revealed an enrichment of alveolar macrophages (C25) in smokers (Dirichlet multinomial P = 0.03) (Fig. 5D and table S20). Differential expression analysis performed among all individuals comparing C25 to all other macrophage clusters showed that the C25 alveolar macrophages cluster markedly upregulated the HLA-II genes (Fig. 5E and table S21), in addition to other inflammatory markers such as IFI6 and ISG15. While high expression of the HLA-II genes was also observed in C55, C25 was the only macrophage cluster (and the only cluster overall) with significantly different prevalence between smokers and never-smokers. To examine granular differences in cell state, we performed differential expression analysis within C25 between smokers and never-smokers (table S19). This analysis revealed that HLA-DRB1 was upregulated on smoker C25 cells, in addition to other inflammatory genes related to the innate immune response (CXCL8, ISG15, DEFB1, IFITM3) (Fig. 5F). Moreover, unbiased pathway analysis of the differentially expressed genes confirmed enrichment of pro-inflammatory pathways in smoker C25 cells compared to never-smoker C25 cells (Fig. 5G and table S22). Additionally, we queried an independent dataset of scRNA-seq data from the normal lung from Travaglini et al. (74), for which cluster annotations and smoking status were available. Though limited in sample size, this analysis demonstrated a two-fold enrichment of alveolar macrophages in a smoker compared to two never-smokers (Fig. 5H). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the differentially expressed genes from Leader et al. C25 and the macrophage cluster from Travaglini et al. as input showed that genes defining the Travaglini et al. macrophage cluster were enriched in C25 (fig. S22A, table S23), suggesting that the clusters were similar across datasets. Alveolar macrophages can act as antigen-presenting cells (79); thus, our data indicate that smoking may increase antigen presentation and inflammatory responses by HLA-II-high alveolar macrophages.

Fig. 5. Tobacco smoking-induced inflammatory programs identified via single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis of the normal lung from three independent cohorts.

(A) UMAP of normal lung scRNA-seq data from Leader et al. Broad compartments containing multiple clusters are labeled. (B) UMAP of cells from smokers only from Leader et al. (C) UMAP of cells from never-smokers only from Leader et al. (D). Increased prevalence of the C25 alveolar macrophage cluster in smokers compared to never-smokers. Boxplots depict minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, maximum, and outliers. (E) Upregulation of HLA-II genes in C25 compared to other macrophage clusters from Leader et al. (F) Differential expression analysis comparing smoker C25 cells to never-smoker C25 cells. (G) Pathway analysis using differentially expressed genes from (F) as input. (H) Enrichment of macrophages in a smoker compared to two never-smokers in an independent scRNA-seq dataset from Travaglini et al. (I) Expression of HLA-II cells in antigen-presenting cells (B cells and macrophages) and epithelial cells from an independent scRNA-seq dataset from Kim et al. containing both tumor and normal lung data. (J) Upregulation of HLA-DRB1 expression across immune and epithelial cells in smokers compared to never-smokers from Kim et al.

Prior work in mice has suggested that MHC-II can be expressed on tumor cells, and that such expression may be correlated with improved clinical outcomes (80). To explore this hypothesis in humans, we obtained a third scRNA-seq dataset (75) of 44 patients for whom both immune and epithelial cells were profiled from both tumor and normal lung. Using this dataset, we found that the HLA-II genes were expressed most highly on myeloid cells and B cells, consistent with their role as antigen presenting cells. However, we also detected expression of the HLA-II genes in small amounts on epithelial cells (Fig. 5I), consistent with prior reports (81). Indeed, the HLA-II genes were expressed on epithelial cells from both normal (fig. S22B) and tumor lung (fig. S22C). Differential expression analyses comparing smokers to never-smokers confirmed that, as observed in myeloid cells, HLA-DRB1 was upregulated in smokers− normal epithelial cells (both AT1 and AT2) (Fig. 5J and table S24). Our findings are supportive of prior studies demonstrating that lung epithelial cells can present antigen to CD4+ T cells via HLA-II (82). Our results validate earlier observations of MHC-II expression in tumors (83) and suggest that alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells may cooperatively respond to tobacco smoking via upregulation of the HLA-II genes and pro-inflammatory pathways in normal tissues.

To investigate the effects of HLA-II heterozygosity on cellular phenotypes in non-small cell lung cancer, we used CIBERSORTx (84) to deconvolve cell type-specific expression from bulk RNA-sequencing data in the TCGA adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and squamous carcinoma (LUSC) cohorts. We performed exploratory analyses assessing the effect of HLA-II heterozygosity HLA-II expression in specific cell types. Notably, this analysis revealed that HLA-II heterozygosity drove higher expression of the HLA-II genes in intratumoral dendritic cells in both LUAD and LUSC (fig. S23) and increased TCR clonality (fig. S24 A and B); in LUSC, we also observed a trend towards higher CD4+ T cell infiltration in HLA-II heterozygous individuals (fig. S24 C and D). Altogether, these data suggest that in lung tumors, HLA-II heterozygosity is associated with increased expression of HLA-II primarily in dendritic cells. Indeed, while dendritic cells and other professional antigen presenting cells are the dominant expressers of HLA-II, our data in normal tissues indicate that epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages may also contribute to risk of lung cancer through expression of HLA-II.

Our observations of both HLA-II expression on epithelial cells from tumor scRNA-seq samples and the effect of HLA-II heterozygosity on reduced lung cancer risk prompted us to ask whether lung tumors evade the immune system via loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the HLA-II genes. Such LOH events would dampen the tumor’s ability to present HLA-II-restricted neoantigens, thus evading recognition by CD4+ T cells, which would provide further evidence for the importance of HLA-II expression on epithelial cells for tumor immune surveillance. While prior work has estimated that roughly 40% of lung cancers exhibit allele-specific LOH at the HLA-I genes (32), the presence and extent of HLA-II LOH in cancer remain unknown. To investigate whether HLA-II LOH occurs in lung cancer, we adapted LOHHLA (32), originally developed to compute allele-specific HLA-I loss in cancer, to evaluate allele-specific loss of HLA-II genes using exome sequencing data from lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD; N = 486) and squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC; N = 450) from TCGA (Materials and Methods). We observed that HLA-II LOH was just as prevalent as HLA-I LOH in NSCLC; in particular, we observed rates of 24% and 38% HLA-II LOH in LUAD and LUSC respectively. For HLA-I LOH, we observed rates of 24% and 37% in LUAD and LUSC (Fig. 6A). Unequivocally, these data suggest that HLA-II LOH, which was previously uncharacterized, is widespread in NSCLC. To validate the observed rates of HLA-II LOH discovered in TCGA, we obtained whole-genome sequencing from two independent cohorts of patients with NSCLC- The Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (85) (PCAWG; N = 83), and the Hartwig Medical Foundation cohort (86) (N = 657). We adapted the methodology from Martínez-Jiménez et al. used to call HLA-I LOH (33) to call HLA-II LOH in these two additional cohorts. In PCAWG, 19-34% of patients had HLA-II LOH; comparably, 26-28% of patients in the Hartwig cohort had HLA-II LOH (Fig. 6A). While the rates of HLA-II LOH are comparable to those of HLA-I LOH, our analysis demonstrates across three independent cohorts and two independent algorithms that HLA-II LOH is as prevalent in NSCLC as HLA-I LOH. Importantly, our data show that HLA-I LOH is often accompanied by HLA-II LOH, suggesting that loss of both loci may be important for tumor evolution.

Fig. 6. HLA-I and HLA-II loss of heterozygosity and immunopeptidome dynamics in lung cancer.

(A) Rates of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at HLA-I and HLA-II across multiple independent large lung cancer cohorts. HLA LOH at all 8 HLA loci in TCGA was calculated using LOHHLA. The proportion of individuals with loss at any class HLA-I (any one or more of HLA-A/B/C) or any class HLA-II locus (any one or more of HLA-DRB1/DQB1/DQA1/DPB1/DPA1) was determined for LUAD (HLA-I: N = 458, HLA-II: N = 465), LUSC (HLA-I N = 416, HLA-II N = 381), and the full cohort, NSCLC, (HLA-I: N =874 , HLA-II N= 846), and displayed as the mean across six LOHHLA coverage filters (5 to 30 in increments of 5). For individuals evaluated at >=1 HLA-I locus and >=1 HLA-II locus, LOH at only HLA-I was defined as LOH at one or more HLA-I loci but no HLA-II loci, and vice versa for HLA-II only LOH (LUAD N = 437, LUSC N = 347). For PCAWG and Hartwig, HLA-I and HLA-II LOH were determined using the Hartwig Medical Foundation analytical pipeline (33). Loss at any HLA-I locus and any HLA-II locus was calculated similarly for the full NSCLC cohort (TCGA= 784; Hartwig: N = 657, PCAWG: N = 83). A subset of samples in Hartwig and PCAWG were specifically annotated by histology (LUAD or LUSC); for these samples, rates within each histology were also calculated (Hartwig LUAD N = 273, Hartwig LUSC N = 35, PCAWG LUAD N = 36, PCAWG LUSC N = 47). All other samples in Hartwig and PCAWGare labeled in the original metadata as NSCLC and are presented in the rightmost panel NSCLC (LUAD+LUSC), which includes samples with and without histology annotation. Dynamics of the predicted neopeptide repertoire in TCGA LUAD (B) and TCGA LUSC (C) in tumors with and without HLA-II LOH. The neopeptide repertories of heterozygous patients unaffected by LOH are indicated by the red boxes. The neopeptide repertoires of patients with LOH at the specified locus before accounting for peptide loss and after accounting peptide loss due to the LOH event are signified by the green and blue boxes, respectively. Homozygous patients without LOH are shown by the purple boxes. Boxplots in (B) and (C) depict minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, maximum, and outliers. Numbers above boxplots in (B) and (C) indicate P-values computed with two-sided Wilcoxon test.

We next sought to investigate the effects of germline HLA-II heterozygosity and HLA-II LOH on the tumor mutational landscape and immunopeptidome. In TCGA LUAD, HLA-II heterozygosity had no effect on tumor mutational burden (TMB) (fig. S25A) but was associated with a larger predicted neopeptide repertoire (fig. S25B), suggesting HLA-II heterozygosity specifically affects MHC-bound mutations. Next, we asked whether HLA-II LOH affected both TMB and the neopeptide repertoire- strikingly, tumors with HLA-II LOH had a higher TMB compared to individuals without LOH (fig. S25C), and a larger neopeptide repertoire at baseline (LOH pre-loss compared to tumors with no LOH) (Fig. 6B). This result suggests that HLA-II LOH is selected for in lung cancer through preferential loss of HLA-II alleles with larger neopeptide repertoires. Moreover, we found that LOH of HLA-DRB1 was associated with lower expression of HLA-II in NSCLC epithelial cells (fig. S24E), suggesting that HLA-II LOH may affect both the tumor immunopeptidome and microenvironment. We next repeated these analyses in the TCGA LUSC cohort—as in LUAD, germline HLA-II heterozygosity was not associated with TMB (fig. S26A) but was associated with a larger neopeptide repertoire (fig. S26B). While in LUSC HLA-II LOH was not associated with TMB (fig. S26C), we observed that tumors with LOH at HLA-DPB1 and HLA-DPA1 had higher neopeptide repertoires at baseline (pre-LOH) compared to those with no HLA-II LOH, again suggesting selection for HLA-II LOH in lung cancer (Fig. 6C). To investigate the properties of peptides lost through HLA-II LOH, we calculated peptide hydrophobicity, previously shown to be a critical determinant of neoantigen immunogenicity (87–90). In both LUAD and LUSC, peptides lost via HLA-DRB1 LOH tended to be more hydrophobic than those that were not lost (fig. S25D and fig. S26D). Collectively, these analyses demonstrate that HLA-II LOH is as prevalent as HLA-I LOH in lung cancer and affects the dynamics of the tumor immunopeptidome.

Discussion

Here we show that HLA-II heterozygosity is associated with reduced risk of lung cancer and accounts for the variability in lung cancer risk among current and former smokers. Through analysis of genetic epidemiological data from two large-scale population cohorts and multimodal genomic data, our study comprises an immunogenetic basis for lung cancer risk. Our data underscore the role of immunosurveillance in protecting against lung cancer. We propose that the immune system—comprised of immunogenetic and cellular diversity—comprises the foundation of tumor rejection and initiation (12–16), together with replicative and hereditary defects and environmental exposures as proposed by Tomasetti and Vogelstein (91, 92).

Our study represents a multimodal interrogation of the influence of HLA heterozygosity on lung cancer risk. The combination of orthogonal approaches—including epidemiological, genetic, and transcriptomic analyses—suggests several complementary mechanisms that may explain the association of HLA-II heterozygosity with reduced risk of lung cancer. Heterozygosity at HLA-II may lead to increased diversity of smoking-related antigens in developing tumors, which could be presented by alveolar macrophages—which express inflammatory markers in response to tissue damage by smoking—or dendritic cells, for recognition by CD4 T cells. It is also possible that antigens could be presented to T cells by precancerous epithelial cells, such as AT1 or AT2 cells. Indeed, the importance of HLA-II expression on epithelial and tumor cells is underscored by our finding of widespread HLA-II loss of heterozygosity in lung cancer. Indeed, we show that HLA-II LOH favors the loss of alleles with larger neopeptide repertoires, underscoring the importance of the HLA-II loci in lung cancer. Further investigation is required to clarify the exact mechanisms by which HLA-II heterozygosity reduces lung cancer risk, including clarification of whether CD4+ T cells themselves clear early neoplastic cells or facilitate their clearance via CD8+ T cell help. Altogether, our data are in agreement with an increasing body of evidence suggesting that CD4+ T cells and MHC-II are critical in the immune response to cancer (83, 93–95).

While our study revealed an HLA-II heterozygote advantage in reducing lung cancer risk, examples of HLA-II heterozygote advantage have been shown previously for other diseases, including ulcerative colitis (96) and hepatitis B infection (39). However, given the many prior examples of HLA-I heterozygote advantage, e.g., in individuals with HIV (38) and metastatic cancer (40–46), it is notable that we did not observe a robust association between HLA-I heterozygosity and lung cancer risk in our study. We note that statistical power may influence the observed associations; indeed, we conducted a power analysis down-sampling the number of lung cancer cases in UK Biobank and found that the number of cases required to observe significance for heterozygosity varied even across the individual HLA-II loci (fig. S27); accordingly, perhaps larger cohorts are needed to observe a signal at HLA-I. In addition, the effects of HLA-II vs HLA-I heterozygosity on cancer risk may depend on the cancer type—to explore this question, we investigated the effects of HLA heterozygosity on risk of 16 other cancer types in the UK Biobank and FinnGen (fig. S28). This analysis revealed that HLA-II heterozygosity was associated with reduced risk of multiple additional solid tumor types in either the UK Biobank or FinnGen. The strongest effects of both HLA-I and HLA-II heterozygosity were observed in lymphoma in both biobanks, motivating further investigation of immunogenetic mechanisms of blood cancer risk (97, 98). However, further work is needed to clarify the differences between immunosurveillance mediated by HLA-I and HLA-II in early tumor development, including the development of refined models in other cancer types incorporating disease-specific covariates.

GWAS have strongly implicated HLA-II alleles in risk of autoimmune diseases (99–101); indeed, our fine-mapping analyses identified positions within the peptide binding groove of HLA-II alleles previously identified by fine-mapping of the MHC in autoimmune disease. Indeed, the varying roles of HLA-II heterozygosity in cancer, infectious disease, and autoimmunity should be investigated further. In particular, HLA-II heterozygosity may also be associated with risk of viral or bacterial infections; these risks, in turn could be exacerbated by one’s smoking status. Importantly, we recommend that such studies should combine longitudinal and lifetime risk data available in large biobanks with mechanistic analyses investigating the various genomic effects of HLA heterozygosity, which together represent key advances of our study in contrast to traditional GWAS or other studies investigating the effect of HLA diversity on cancer risk (98).

An important consideration with respect to replication of our heterozygosity results is the major compositional differences between the UK Biobank and FinnGen. While both datasets represent population-scale cohorts with longitudinal follow-up data for cancer risk analyses, an essential difference between the two cohorts is the previously described healthy volunteer bias in the UK Biobank (102). This healthy volunteer bias results in lower rates of cancer incidence in the UK Biobank compared to the general population, and lower rates of smoking, which may explain in part the relatively low number of small cell lung cancer cases included in the cohort. For these reasons, we sought to validate our results in FinnGen, which recruited healthy volunteers in addition to individuals diagnosed with particular diseases (51, 52), and is thus more representative of general population in terms of disease incidence. The preponderance of individuals with disease in FinnGen may in part explain the higher number of lung cancer cases in FinnGen compared to the UK Biobank despite the smaller total sample size of FinnGen (183163 individuals compared to 391182 individuals). Overall, we believe that the broad replication of the protective effect of HLA heterozygosity discovered in the UK Biobank represents a clinically relevant effect, given how different the two cohorts are with respect to demographics and healthy volunteer bias.

Our study nominates population-level immunogenetic variation as a factor underlying the risk of lung cancer. A greater understanding of immunogenetic determinants of cancer risk—including genetic variation in HLA and other immune genes and pathways commonly associated with autoimmune and infectious diseases—may foster the development of improved strategies for cancer prevention. Indeed, our study suggests that current or former smokers homozygous at HLA-II could be considered at an earlier age for low-dose computed tomographic (LDCT) screening, which may reduce lung cancer mortality (103). Whether the combination of genotype-driven risk assessment and LDCT reduces lung cancer mortality compared to either method alone should be comprehensively investigated in a future prospective clinical trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work was carried out under UK Biobank application 61123. We acknowledge the participants and investigators of FinnGen study. The FinnGen project is funded by two grants from Business Finland (HUS 4685/31/2016 and UH 4386/31/2016) and the following industry partners: AbbVie Inc., AstraZeneca UK Ltd, Biogen MA Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb (and Celgene Corporation & Celgene International II Sàrl), Genentech Inc., Merck Sharp & Dohme LCC, Pfizer Inc., GlaxoSmithKline Intellectual Property Development Ltd., Sanofi US Services Inc., Maze Therapeutics Inc., Janssen Biotech Inc, Novartis AG, and Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH. Following biobanks are acknowledged for delivering biobank samples to FinnGen: Auria Biobank (www.auria.fi/biopankki), THL Biobank (www.thl.fi/biobank), Helsinki Biobank (www.helsinginbiopankki.fi), Biobank Borealis of Northern Finland (https://www.ppshp.fi/Tutkimus-ja-opetus/Biopankki/Pages/Biobank-Borealis-briefly-in-English.aspx), Finnish Clinical Biobank Tampere (www.tays.fi/en-US/Research_and_development/Finnish_Clinical_Biobank_Tampere), Biobank of Eastern Finland (www.ita-suomenbiopankki.fi/en), Central Finland Biobank (www.ksshp.fi/fi-FI/Potilaalle/Biopankki), Finnish Red Cross Blood Service Biobank (www.veripalvelu.fi/verenluovutus/biopankkitoiminta), Terveystalo Biobank (www.terveystalo.com/fi/Yritystietoa/Terveystalo-Biopankki/Biopankki/) and Arctic Biobank (https://www.oulu.fi/en/university/faculties-and-units/faculty-medicine/northern-finland-birth-cohorts-and-arctic-biobank). All Finnish Biobanks are members of BBMRI.fi infrastructure (www.bbmri.fi). Finnish Biobank Cooperative -FINBB (https://finbb.fi/) is the coordinator of BBMRI-ERIC operations in Finland. The Finnish biobank data can be accessed through the Fingenious® services (https://site.fingenious.fi/en/), managed by FINBB. This work was supported in part through the computational and data resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing and Data at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) grant ULTR004419 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. This publication and the underlying study have been made possible partly on the basis of the data that the Hartwig Medical Foundation and the Center of Personalised Cancer Treatment have made available to the study. F.M.J. would like to acknowledge the Cellex Foundation for providing research facilities and equipment.

Funding:

Alexander and Alexandrine Sinsheimer Foundation (D.C.)

US National Institutes of Health grant DP5 OD028171 (R.M.S.)

Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists (R.M.S.)

American Lung Association Lung Cancer Discovery Award (R.M.S.)

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Translational Immunology Training Program (T32 AI078892) (M.S.)

Instrumentarium science foundation (H.O., A.T.)

Academy of Finland 331671 (N.M.)

University of Helsinki HiLIFE Fellows Grant 2023-2025 (N.M.)

Finska Lakaresallskapet (N.M.)

LUNGevity Foundation (M.E.S., Z.H.G.)

Cancer Moonshot NCI R33 award # CA263705-01 (M.E.S., Z.H.G.)

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) 437857095 (T.L.L.)

State Agency for Research (Agencia Estatal de Investigación) Center of Excellence Severo Ochoa CEX2020-001024-S/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (F.M.J.)

The CaixaResearch Advanced Oncology Research Programme supported by “La Caixa” Foundation (F.M.J.)

Footnotes

Competing interests:

D.C. and R.M.S. have filed a patent application related to tumor mutational load (17536715). D.C., C.K., and T.L have filed a patent application related to HLA class I sequence divergence and cancer therapy (17770259). M.M. serves on the scientific advisory board and holds stock from Compugen, Myeloid Therapeutics, Morphic Therapeutics, Asher Bio, Dren Bio, Nirogy, Oncoresponse, Owkin, Pionyr, OSE and Larkspur. M.M. serves on the scientific advisory board of Innate Pharma, DBV, and Genenta. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All source data for epidemiological analyses can be accessed through applications to the UK Biobank (application 61132; https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research/apply-for-access) and FinnGen R8 (https://www.finngen.fi/en). HLA allele amino acid sequences for the fine-mapping analyses can be accessed through IMGT (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/imgt/hla/alleles/). Datasets used for single cell RNA-sequencing analyses can be accessed from the corresponding studies listed in the methods section—links to the public repositories containing these data are as follows: Leader et al.- www.github.com/effiken/Leader_et_al, Travaglini et al.- https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn21041850/wiki/600865, Kim et al.- deposited in GEO with accession ID GSE131907. Whole exome sequencing and RNA-sequencing data from the TCGA can be accessed at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/. Re-analyzed whole-genome sequencing data from the PCAWG and Hartwig Medical Foundation samples can be accessed from the original study listed in the methods section (Martínez-Jiménez et al.) at the following repositories- https://icgc.bionimbus.org/files/5310a3ac-0344-458a-88ce-d55445540120, https://dcc.icgc.org/releases/PCAWG/Hartwig, and https://www.hartwigmedicalfoundation.nl/en/applying-for-data.

References

- 1.Herbst RS, V Heymach J, Lippman SM, Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 359, 1367–1380 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2022. CA. Cancer J. Clin 72, 7–33 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F, Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin 71, 209–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida K, Gowers KHC, Lee-Six H, Chandrasekharan DP, Coorens T, Maughan EF, Beal K, Menzies A, Millar FR, Anderson E, Clarke SE, Pennycuick A, Thakrar RM, Butler CR, Kakiuchi N, Hirano T, Hynds RE, Stratton MR, Martincorena I, Janes SM, Campbell PJ, Tobacco smoking and somatic mutations in human bronchial epithelium. Nature. 578, 266–272 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DOLL R, HILL AB, Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. Br. Med. J 2, 739–748 (1950). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai X, Gil GF, Reitsma MB, Ahmad NS, Anderson JA, Bisignano C, Carr S, Feldman R, Hay SI, He J, Iannucci V, Lawlor HR, Malloy MJ, Marczak LB, McLaughlin SA, Morikawa L, Mullany EC, Nicholson SI, O’Connell EM, Okereke C, Sorensen RJD, Whisnant J, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Murray CJL, Gakidou E, Health effects associated with smoking: a Burden of Proof study. Nat. Med 28, 2045–2055 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long E, Patel H, Byun J, Amos CI, Choi J, Functional studies of lung cancer GWAS beyond association. Hum. Mol. Genet 31, R22–R36 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill W, Lim EL, Weeden CE, Lee C, Augustine M, Chen K, Kuan F-C, Marongiu F, Evans EJ, Moore DA, Rodrigues FS, Pich O, Bakker B, Cha H, Myers R, van Maldegem F, Boumelha J, Veeriah S, Rowan A, Naceur-Lombardelli C, Karasaki T, Sivakumar M, De S, Caswell DR, Nagano A, Black JRM, Martínez-Ruiz C, Ryu MH, Huff RD, Li S, Favé M-J, Magness A, Suárez-Bonnet A, Priestnall SL, Lüchtenborg M, Lavelle K, Pethick J, Hardy S, McRonald FE, Lin M-H, Troccoli CI, Ghosh M, Miller YE, Merrick DT, Keith RL, Al Bakir M, Bailey C, Hill MS, Saal LH, Chen Y, George AM, Abbosh C, Kanu N, Lee S-H, McGranahan N, Berg CD, Sasieni P, Houlston R, Turnbull C, Lam S, Awadalla P, Grönroos E, Downward J, Jacks T, Carlsten C, Malanchi I, Hackshaw A, Litchfield K, Lester JF, Bajaj A, Nakas A, Sodha-Ramdeen A, Ang K, Tufail M, Chowdhry MF, Scotland M, Boyles R, Rathinam S, Wilson C, Marrone D, Dulloo S, Fennell DA, Matharu G, Shaw JA, Riley J, Primrose L, Boleti E, Cheyne H, Khalil M, Richardson S, Cruickshank T, Price G, Kerr KM, Benafif S, Gilbert K, Naidu B, Patel AJ, Osman A, Lacson C, Langman G, Shackleford H, Djearaman M, Kadiri S, Middleton G, Leek A, Hodgkinson JD, Totten N, Montero A, Smith E, Fontaine E, Granato F, Doran H, Novasio J, Rammohan K, Joseph L, Bishop P, Shah R, Moss S, Joshi V, Crosbie P, Gomes F, Brown K, Carter M, Chaturvedi A, Priest L, Oliveira P, Lindsay CR, Blackhall FH, Krebs MG, Summers Y, Clipson A, Tugwood J, Kerr A, Rothwell DG, Kilgour E, Dive C, Aerts HJWL, Schwarz RF, Kaufmann TL, Wilson GA, Rosenthal R, Van Loo P, Birkbak NJ, Szallasi Z, Kisistok J, Sokac M, Salgado R, Diossy M, Demeulemeester J, Bunkum A, Stewart A, Frankell AM, Karamani A, Toncheva A, Huebner A, Chain B, Campbell BB, Castignani C, Puttick C, Richard C, Hiley CT, Pearce DR, Karagianni D, Biswas D, Levi D, Hoxha E, Cadieux EL, Colliver E, Nye E, Gálvez-Cancino F, Athanasopoulou F, Gimeno-Valiente F, Kassiotis G, Stavrou G, Mastrokalos G, Zhai H, Lowe HL, Matos IG, Goldman J, Reading JL, Herrero J, Rane JK, Nicod J, Lam JM, Hartley JA, Peggs KS, Enfield KSS, Selvaraju K, Thol K, Ng KW, Dijkstra K, Grigoriadis K, Thakkar K, Ensell L, Shah M, Duran MV, Litovchenko M, Sunderland MW, Dietzen M, Leung M, Escudero M, Angelova M, Tanić M, Chervova O, Lucas O, Al-Sawaf O, Prymas P, Hobson P, Pawlik P, Stone RK, Bentham R, Hynds RE, Vendramin R, Saghafinia S, López S, Gamble S, Ung SKA, Quezada SA, Vanloo S, Zaccaria S, Hessey S, Ward S, Boeing S, Beck S, Bola SK, Denner T, Marafioti T, Mourikis TP, Watkins TBK, Spanswick V, Barbè V, Lu W-T, Liu WK, Wu Y, Naito Y, Ramsden Z, Veiga C, Royle G, Collins-Fekete C-A, Fraioli F, Ashford P, Clark T, Forster MD, Lee SM, Borg E, Falzon M, Papadatos-Pastos D, Wilson J, Ahmad T, Procter AJ, Ahmed A, Taylor MN, Nair A, Lawrence D, Patrini D, Navani N, Thakrar RM, Janes SM, Hoogenboom EM, Monk F, Holding JW, Choudhary J, Bhakhri K, Scarci M, Hayward M, Panagiotopoulos N, Gorman P, Khiroya R, Stephens RCM, Wong YNS, Bandula S, Sharp A, Smith S, Gower N, Dhanda HK, Chan K, Pilotti C, Leslie R, Grapa A, Zhang H, AbdulJabbar K, Pan X, Yuan Y, Chuter D, MacKenzie M, Chee S, Alzetani A, Cave J, Scarlett L, Richards J, Ingram P, Austin S, Lim E, De Sousa P, Jordan S, Rice A, Raubenheimer H, Bhayani H, Ambrose L, Tracer. Consortium, Lung adenocarcinoma promotion by air pollutants. Nature. 616, 159–167 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malhotra J, Malvezzi M, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P, Eur. Respir. J, in press, doi: 10.1183/13993003.00359-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bach PB, Kattan MW, Thornquist MD, Kris MG, Tate RC, Barnett MJ, Hsieh LJ, Begg CB, Variations in Lung Cancer Risk Among Smokers. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst 95, 470–478 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corthay A, Does the immune system naturally protect against cancer? Front. Immunol 5, 197 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrlich P, Über den jetzigen Stand der Chemotherapie. Berichte der Dtsch. Chem. Gesellschaft 42, 17–47 (1909). [Google Scholar]

- 13.BURNET M, Cancer: a biological approach. III. Viruses associated with neoplastic conditions. IV. Practical applications. Br. Med. J 1, 841–847 (1957). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.BURNET M, IMMUNOLOGICAL FACTORS IN THE PROCESS OF CARCINOGENESIS. Br. Med. Bull 20, 154–158 (1964). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas L, On immunosurveillance in human cancer. Yale J. Biol. Med 55, 329–333 (1982). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnet FM, The concept of immunological surveillance. Prog. Exp. Tumor Res 13, 1–27 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ, Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 331, 1565–1570 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Fraumeni JFJ, Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Wolfe RA, Goodrich NP, Bayakly AR, Clarke CA, Copeland G, Finch JL, Lou Fleissner M, Goodman MT, Kahn A, Koch L, Lynch CF, Madeleine MM, Pawlish K, Rao C, Williams MA, Castenson D, Curry M, Parsons R, Fant G, Lin M, Spectrum of cancer risk among US solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 306, 1891–1901 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burch PR, Leucocyte phenotypes in Hodgkin’s disease. Lancet (London, England). 2, 771–772 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schratz KE, Flasch DA, Atik CC, Cosner ZL, Blackford AL, Yang W, Gable DL, Vellanki PJ, Xiang Z, Gaysinskaya V, Vonderheide RH, Rooper LM, Zhang J, Armanios M, T cell immune deficiency rather than chromosome instability predisposes patients with short telomere syndromes to squamous cancers. Cancer Cell (2023), doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billerbeck E, Wolfisberg R, Fahnøe U, Xiao JW, Quirk C, Luna JM, Cullen JM, Hartlage AS, Chiriboga L, Ghoshal K, Lipkin WI, Bukh J, Scheel TKH, Kapoor A, Rice CM, Mouse models of acute and chronic hepacivirus infection. Science. 357, 204–208 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marderstein AR, Uppal M, Verma A, Bhinder B, Tayyebi Z, Mezey J, Clark AG, Elemento O, Demographic and genetic factors influence the abundance of infiltrating immune cells in human tissues. Nat. Commun 11, 2213 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGranahan N, Furness AJS, Rosenthal R, Ramskov S, Lyngaa R, Saini SK, Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, Birkbak NJ, Hiley CT, Watkins TBK, Shafi S, Murugaesu N, Mitter R, Akarca AU, Linares J, Marafioti T, Henry JY, Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Schadendorf D, Garraway LA, Makarov V, Rizvi NA, Snyder A, Hellmann MD, Merghoub T, Wolchok JD, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Peggs KS, Chan TA, Hadrup SR, Quezada SA, Swanton C, Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science. 351, 1463–1469 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM, Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med 377, 2500–2501 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chowell D, Yoo S-K, Valero C, Pastore A, Krishna C, Lee M, Hoen D, Shi H, Kelly DW, Patel N, Makarov V, Ma X, Vuong L, Sabio EY, Weiss K, Kuo F, Lenz TL, Samstein RM, Riaz N, Adusumilli PS, Balachandran VP, Plitas G, Ari Hakimi A, Abdel-Wahab O, Shoushtari AN, Postow MA, Motzer RJ, Ladanyi M, Zehir A, Berger MF, Gönen M, Morris LGT, Weinhold N, Chan TA, Improved prediction of immune checkpoint blockade efficacy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Biotechnol (2021), doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01070-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samstein RM, Lee C-H, Shoushtari AN, Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, Barron DA, Zehir A, Jordan EJ, Omuro A, Kaley TJ, Kendall SM, Motzer RJ, Hakimi AA, Voss MH, Russo P, Rosenberg J, Iyer G, Bochner BH, Bajorin DF, Al-Ahmadie HA, Chaft JE, Rudin CM, Riely GJ, Baxi S, Ho AL, Wong RJ, Pfister DG, Wolchok JD, Barker CA, Gutin PH, Brennan CW, Tabar V, Mellinghoff IK, DeAngelis LM, Ariyan CE, Lee N, Tap WD, Gounder MM, D’Angelo SP, Saltz L, Stadler ZK, Scher HI, Baselga J, Razavi P, Klebanoff CA, Yaeger R, Segal NH, Ku GY, DeMatteo RP, Ladanyi M, Rizvi NA, Berger MF, Riaz N, Solit DB, Chan TA, Morris LGT, Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet 51, 202–206 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, Miller ML, Rekhtman N, Moreira AL, Ibrahim F, Bruggeman C, Gasmi B, Zappasodi R, Maeda Y, Sander C, Garon EB, Merghoub T, Wolchok JD, Schumacher TN, Chan TA, Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 348, 124–128 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKay JD, Hung RJ, Han Y, Zong X, Carreras-Torres R, Christiani DC, Caporaso NE, Johansson M, Xiao X, Li Y, Byun J, Dunning A, Pooley KA, Qian DC, Ji X, Liu G, Timofeeva MN, Bojesen SE, Wu X, Le Marchand L, Albanes D, Bickeböller H, Aldrich MC, Bush WS, Tardon A, Rennert G, Teare MD, Field JK, Kiemeney LA, Lazarus P, Haugen A, Lam S, Schabath MB, Andrew AS, Shen H, Hong Y-C, Yuan J-M, Bertazzi PA, Pesatori AC, Ye Y, Diao N, Su L, Zhang R, Brhane Y, Leighl N, Johansen JS, Mellemgaard A, Saliba W, Haiman CA, Wilkens LR, Fernandez-Somoano A, Fernandez-Tardon G, van der Heijden HFM, Kim JH, Dai J, Hu Z, Davies MPA, Marcus MW, Brunnström H, Manjer J, Melander O, Muller DC, Overvad K, Trichopoulou A, Tumino R, Doherty JA, Barnett MP, Chen C, Goodman GE, Cox A, Taylor F, Woll P, Brüske I, Wichmann H-E, Manz J, Muley TR, Risch A, Rosenberger A, Grankvist K, Johansson M, Shepherd FA, Tsao M-S, Arnold SM, Haura EB, Bolca C, Holcatova I, Janout V, Kontic M, Lissowska J, Mukeria A, Ognjanovic S, Orlowski TM, Scelo G, Swiatkowska B, Zaridze D, Bakke P, Skaug V, Zienolddiny S, Duell EJ, Butler LM, Koh W-P, Gao Y-T, Houlston RS, McLaughlin J, Stevens VL, Joubert P, Lamontagne M, Nickle DC, Obeidat M, Timens W, Zhu B, Song L, Kachuri L, Artigas MS, Tobin MD, V Wain L, Rafnar T, Thorgeirsson TE, Reginsson GW, Stefansson K, Hancock DB, Bierut LJ, Spitz MR, Gaddis NC, Lutz SM, Gu F, Johnson EO, Kamal A, Pikielny C, Zhu D, Lindströem S, Jiang X, Tyndale RF, Chenevix-Trench G, Beesley J, Bossé Y, Chanock S, Brennan P, Landi MT, Amos CI, Consortium S, Large-scale association analysis identifies new lung cancer susceptibility loci and heterogeneity in genetic susceptibility across histological subtypes. Nat. Genet 49, 1126–1132 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]