Abstract

Inhibiting the protein-protein interaction (PPI) between Keap1 and Nrf2 is theoretically an effective and safe strategy for activation of Nrf2 pathway to treat major depressive disorder (MDD). In this study, through bioinformatic analysis of the brain tissues and peripheral blood of MDD patients and depressive mice, we confirmed the involvement of oxidative stress, inflammation, and the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in depression. Subsequently, we developed a series of phosphodiester amino acidic diaminonaphthalene compounds as Keap1-Nrf2 PPI inhibitors for the first time. Screening using the LPS-stimulated SH-SY5Y and BV2 cell models identified compound 4–95 showing the best anti-oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory efficacy. The ability of 4–95 to penetrate the blood-brain-barrier was significantly enhanced. In a chronic unpredictable mild stress mouse model, treatment with 4–95 effectively ameliorated anxiety and depression behavior and restored serum neurotransmitter levels by promoting the Nrf2 nuclear translocation. Consequently, oxidative stress was reduced, and the expression of synaptic plasticity biomarkers, such as postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) and synapsin 1 (SYN1) were significantly increased, suggesting the recovery of neuronal function. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that the Keap1-Nrf2 PPI inhibitor holds great promise as a preclinical candidate for the treatment of depression.

Keywords: Keap1, Nrf2, Protein-protein interaction, Inhibitor, Anti-depressant, Phosphodiester

1. Introduction

Mental disorders, including depression, were the leading causes of the global health-related burden [1]. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a chronic, generally episodic and debilitating disease, characterized by long-term emotional problems, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, and many chronic physical discomforts [2]. The disorder results in social functioning problems and high rates of suicide or suicide attempts [3]. Nowadays, according to Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, MDD affects about 357 million people in the world, and the incidence is still increasing annually [4]. In China, the lifetime prevalence of adult depressive disorder is 6.8 %, with a high suicidal ideation rate of 53.1 %, which continuously causes great economic and social burdens [5]. World Health Organization predicts that, in 2030, MDD will be the leading cause of disease burden worldwide [6].

The etiology of depression is complex, which was considered as the combined results of genetic, biological, social, psychological, and other factors [7]. Moreover, the pathological mechanisms of depression involve multiple highly complex and interrelated pathways. The deficiency of monoamine, such as 5-serotonin (5-HT), noradrenaline (NA), and dopamine, has been accepted as the most common hypothesis of MDD for a long period [8]. The abnormal activity of other neurotransmitters, like gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamatergic systems, and related receptors, including N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, directly impacts on synaptic neurotransmission [[9], [10], [11]]. Besides, it indirectly affects intracellular pathways, resulting in enhanced potassium channel function, cell depolarization, and inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channel function [[12], [13], [14]]. These effects negatively regulate neurotransmitter release, ultimately influencing neuronal survival and plasticity [15]. The deficiency of neurotrophic factors and down-regulation of the related pathways compromise neuroplasticity, neurotrophy, and neurogenesis [15,16]. This impairment gives rise to neuronal dysfunction and contributes to the development of depression. Hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, particularly glucocorticoids (GCs), play a critical role in the behavioral and physiological consequences of exposure to stress. Dysfunction of the HPA axis is either associated with MDD and/or potentially related to treatment response [17]. Stress-induced alterations in the immune system and inflammation in peripheral organs may affect interaction between neurons and glial cells, including microglia and astrocytes [18,19]. This disruption gives rise to neuroinflammation, which is a contributing factor to brain dysfunction and ultimately leads to the manifestation of behavioral phenotypes. Imbalanced microbiota-gut-brain (MGB) axis regulation aggravates depression-related pathological changes through microbial metabolites, systemic inflammatory responses, immune defenses, motility, and permeability of gut [20]. Although many hypotheses have been used to explain the pathogenesis of depression, controversy persists. Given its high oxygen consumption and relatively weak antioxidative defense, the brain is particularly susceptible to oxidative stress (OS) [21]. In recent years, many studies have shown that OS serves as one of the important pathogenic factors in the onset and development of depressive disorders across different age groups [22]. It has been revealed that aged depressive patients exhibited lower antioxidant activities, which are associated with higher levels of ROS and oxidative damage products [23]. OS is also a contributing factor in childhood adversity and the development of several psychological disorders (e.g., MDD) in the adult populations. Moreover, higher levels of maternal OS during pregnancy have been linked to mental disorders in offspring [[24], [25], [26]]. More importantly, OS acts as a connecting factor among other pathological mechanisms in the pathogenesis of depression [22,27]. Consequently, anti-OS treatment could be a promising strategy for managing depression.

The master redox-sensitive transcription factor, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), occupies a central role in cell defensive system to OS [28]. The activity of the Nrf2 signaling pathway is predominantly regulated by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), an E3 ubiquitin ligase substrate adaptor. Keap1 negatively regulates Nrf2 by targeting it for rapid proteasomal degradation. Under OS and other stressed conditions, the double glycine repeat (DGR) domain of Keap1 undergoes conformational changes and dissociates from Keap1. This dissociation inhibits the ubiquitination and degradation of Nrf2. Subsequently, Nrf2 is released and translocated into the nucleus, which further increases the transcription of a series of antioxidant enzymes [29]. It has been discovered that the expression level of Nrf2 was decreased in the postmortem brain of depressive patients when compared to that of control subjects. Similarly, decreased Nrf2 expression has been observed in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), CA3 region and dentate gyrus (DG) of hippocampus in mice, exhibiting a depression-like phenotype [30,31]. Seasonal changes related to depression trigger multiple signaling pathways, among which Nrf2 antioxidant pathway is involved [32]. In a chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) model, the expressions of two antioxidant enzymes targeted by Nrf2, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1 (NQO1) and heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), are significantly reduced Moreover, the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) are also declined [33,34]. Mice deficient in Nrf2 experience persistent OS, which are more susceptible to depression [35]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that Nrf2 represents a potential target for the treatment of depression.

Small molecule chemicals have demonstrated the potential to ameliorate depressive and anxiety-like behaviors by activating of Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Dimethyl fumarate (DMF), a Nrf2 activator approved by US Food and Drug Administration, exhibits the anti-anxiety and anti-depressive-like effects [36]. Some natural products, such as sulforaphane, resveratrol, curcumin, have been shown to inhibit OS and inflammation in various depressive mouse models through Nrf2 activation [[37], [38], [39]]. In addition, edaravone, a classic agent to scavenge free radicals, activates Sirt1/Nrf2/HO-1/Gpx4 pathway in a chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) depression model [40]. Besides, physical exercise, transcranial magnetic stimulation, or other non-drug treatment, mediate the antidepressant effects, and their mechanisms are associated with up-regulation of the Nrf2 pathway [41]. All these findings suggest that the activation of Nrf2 may be beneficial for relieving depression. Nevertheless, it is important to note that some Nrf2 activators possess potentially high cytotoxicity due to their mechanism of action. These compounds are mainly electrophiles that covalently modify the cysteine residues in Keap1 cysteines, thereby releasing Nrf2 [42]. For the first time, we reported an 1,4-diaminonaphthalene non-covalent inhibitor of the Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction (PPI) inhibitor, NXPZ-2. The inhibitor demonstrated a protective effect in a β-amyloid stereotaxic brain injection-induced Alzheimer's disease (AD) mouse model [43]. Subsequently, a new phosphodiester containing diaminonaphthalene derivative, POZL, was further confirmed for the efficacy and safety in a transgenic AD mouse model [29]. Besides, several analogues have been validated in the inflammatory models [[44], [45], [46]]. In the present study, we provide the first evidence that a newly designed phosphodiester amino acidic diaminonaphthalene compound 4–95, with blood-brain-barrier (BBB) permeability, has promising effects on managing depression. In lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated SH-SY5Y and BV2 cells, 4–95 showed superior antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. In a CUMS mouse model, 4–95 effectively reduced anxiety and depression, restored neurotransmitters, and mitigated oxidative stress by promoting the Nrf2 nuclear translocation. It also increased synaptic plasticity markers like postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) and synapsin 1 (SYN1), and upregulated brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression by promoting cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation and inhibiting transcriptional repressors.

2. Results

2.1. Oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways are up-regulated in the brain tissues and peripheral blood of MDD patients

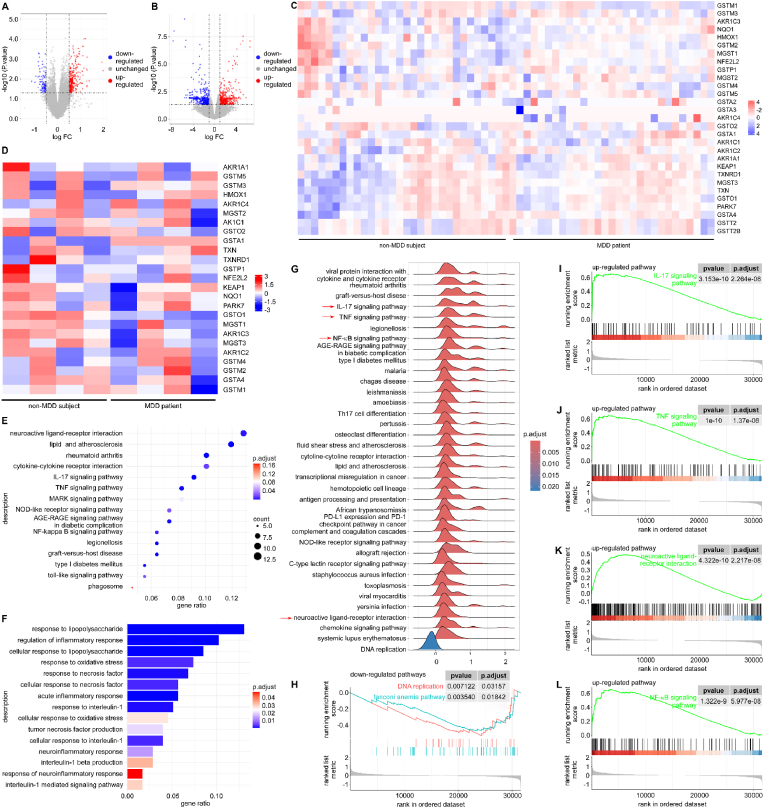

Depression has evolved into a pervasive public health problem, encompassing intricate pathophysiologic mechanisms that involve large amounts of diverse molecules and pathways. To identify the genes expressed in MDD patients as compared to non-MDD subjects, two gene expression profiles (GSE190518 and GSE101521) were carefully selected and retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The microarray dataset GSE101521, contained 21 subjects with MDD and suicide, 9 subjects with MDD but no suicide, and 29 subjects with sudden death but without MDD nor suicide (59 samples in total). We combined the patients of MDD with or without suicide into a single group, named depressive patient group. Compared with non-MDD subjects, the expression levels of 429 genes were significantly changed in the brain tissues. Specifically, 329 up-regulated genes and 100 down-regulated genes were observed (Fig. 1A). Nrf2 (encoded by NFE2L2) and some of Nrf2-targeted genes (database from https://www.genome.jp/entry/hsa:4780), such as NQO1, TXN, GSTM1, and HMOX1, were changed in the brain tissues (Fig. 1C). The microarray dataset GSE190518 include 4 samples of peripheral blood cells from MDD patients, and 4 samples from non-MDD subjects. In this dataset, 428 up-regulated genes and 381 down-regulated genes were identified (Fig. 1B). Remarkably, Nrf2 (NFE2L2) and many of Nrf2-targeted genes, including NQO1, TXN, GSTM1, and HMOX1, were still found in the peripheral blood cells. The two database results both suggested that the Nrf2 signaling pathway may play an essential role in the progression of depression (Fig. 1D). Next, gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis in the brain tissues revealed that the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were significantly enriched in those associated with the regulation of oxidoreductase activity (P < 0.01), oxidation-reduction process (P < 0.01), and the inflammatory production and response process (Fig. 1E). Subsequently, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis revealed that the up-regulated gene set was significantly enriched in pathways related to the TNF signaling pathway (P < 0.05), the IL-17 signaling pathway (P < 0.05), and the cytokine-cytokine interaction pathway (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1F). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was then performed to analyze the brain samples from the GSE101521 dataset. Further analysis using the KEGG gene set enrichment analysis (KEGG-GSEA) indicated that the set of DEGs was significantly enriched in the IL-17 signaling pathway (P < 0.001, Fig. 1G and I), and the TNF signaling pathway (P < 0.001, Fig. 1G and J). In addition, the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction (P < 0.001, Fig. 1G and K) and NF-κB signaling pathway (P < 0.001, Fig. 1G and L) were significantly changed. The representative down-regulated pathway was the DNA replication pathway, which showed little correlation with depression in this study (P < 0.01, Fig. 1H).

Fig. 1.

Bioinformatic analysis of the brain tissues and peripheral blood of MDD patients. (A) Volcano plots of all the genes of the brain tissue from non-MDD subjects and MDD patients. (B) Volcano plots of all the genes in the peripheral blood from non-MDD subjects and MDD patients. (C) Heatmap of the Nrf2 targeted genes in the brain tissues from non-MDD subjects (n = 29) and MDD patients (n = 30). (D) Heatmap of the Nrf2 targeted genes in the peripheral blood from non-MDD (n = 4) and MDD patients with (n = 4). (E) GO enrichment analysis of up-regulated enriched DEGs in the brain tissues from non-MDD and MDD patients. (F) KEGG enrichment analysis of up-regulated enriched DEGs in the brain tissues from non-MDD subjects and MDD patients. (G) Up-regulated pathways in brain tissues of volunteers without MDD and patients with MDD by the KEGG-GSEA analysis. (H) The relationship between the down-regulated pathways obtained from the GSE101521 dataset analyzed by GSEA. The relationship between up-regulated pathways obtained from the GSE101521 dataset analyzed by GSEA, which were IL-17 signaling pathway (I), TNF signaling pathway (J), neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction (K), and NF-κB signaling pathway (L), .

Besides, some further analyses have been conducted based on mouse datasets (GSE151807). Compared with control mice, the expression levels of 4040 genes were significantly altered in the brain tissues of chronic mild stress (CMS) mice. Specifically, 2029 genes were up-regulated and 2011 genes were down-regulated (Fig. S1A). Similar to human samples, we focused on Nfe2l2 and its downstream target genes (database from https://www.genome.jp/entry/mmu:18024). The results showed that Nfe2l2 and many of Nrf2-targeted genes, such as Nqo1, Hmox1, Txn, Gstm, Txnip, Gsto, Mgst, among others, underwent changes in the brain tissues of CMS mice (Fig. S1B). GO enrichment analysis showed that the up-regulated DEGs were significantly enriched in those related to the response to OS (P < 0.0025), IL-6 production (P < 0.0050), and the regulation of inflammatory response (P < 0.0025). Meanwhile, the down-regulated genes were significantly enriched in terms related to behavior, synaptic function, and neurotransmission (Fig. S1C). These results exhibited a high degree of consistency with those in the human database. In conclusion, OS and inflammation were up-regulated in the brain tissues and peripheral blood, related to depression, and Keap1-Nrf2 pathway seemed to be the vital one to play an important role in the pathology of depression both in human and experimental mice.

2.2. Rational design obtains the phosphodiester amino acidic diaminonaphthalene compounds effectively blocking Keap1-Nrf2 interaction

POZL is a phosphodiester diaminonaphthalene compound and the binding mode with Keap1 Kelch domain has been first determined by our group (PDB code: 7XOT) [29]. The diaminonaphthalene moiety of the lead compound NXPZ-2 is situated within the classical binding pocket [43] and the phosphodiester group is located in the solvent exposed region, with no critical binding interactions being observed. However, POZL still exhibited unsatisfactory properties, including low solubility and BBB permeability. The previous design on NXPZ-2 has confirmed that chemical modification on one side of diaminonaphthalene moiety to decrease the compound symmetry is useful to address the properties. The amino acid should be a good moiety to further change the properties that has been validated in Keap1-Nrf2 inhibitors [44,47]. In this study, different amino acids were introduced between the benzosulfamide and phosphodiester moiety. The main interactions of the newly designed compounds with the Kelch domain remained unchanged and their binding affinities were almost maintained within nanomolar range (Fig. 2A–H). 4–83 with a glycine (KD2 = 97 nM, Fig. 2B) and 4–107 with an alanine (KD2 = 115 nM, Fig. 2D) showed similar activities like that of POZL (KD2 = 112 nM, Fig. 2A). When using phenylalanine (Fig. 2C), methionine (Fig. 2F), and tyrosine (Fig. 2G) with high steric hindrance, the activities were decreased. With a proline, compound 4–114 (KD2 = 81 nM, Fig. 2E) and 4–95 (KD2 = 106 nM, Fig. 2H), exhibited higher activities than POZL (KD2 = 112 nM, Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

The biochemical assays of the compounds and the predicted binding modes of 4–95 with Keap1 Klech domain. (A–H) Determination of equilibrium dissociation constants KD2 for each compound was performed using the fluorescence anisotropy assay. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). (I) The first binding pose of 4–95 with Keap1 Klech domain (The protein is from PDB 7XOT). (J) The second binding pose of 4–95 with Keap1 Klech domain. (K) The superposition of two possible binding poses of 4–95, NXPZ-2 (purple) and Keap1 Klech domain in a ribbon mode. Keap1 is shown in gray ribbon and the key residues of Keap1 interacting with compounds labeled and shown in the gray stick model. 4–95 is shown in the green or blue stick mode. Hydrogen bonds are depicted as light green dashed lines. The π-π stacking interactions are depicted as gray dashed lines. (L) Superposition of two binding poses of 4–95 and Keap1 in a surface mode.

Next, molecular docking study was performed to better understand the molecular interactions between Kelch domain and the inhibitors. Here, we selected 4–95 as an example for the prediction. Structure analysis results showed that 4–95 bound to Keap1 within the same pocket as previous compounds [29,44] (Fig. 2I–L). This compound still interacted through two distinct modes with ∼50 % occupancy for each conformation, because 4–95 is unsymmetric binding with the approximate symmetric protein. Residues S363, N414, R415, S508, Q530 and S602 formed hydrogen-bonding interactions with 4–95. Y525, Y572 and F577 residues showed π-π packing interactions with the aromatic ring of 4–95 and R415 formed a π-cation interaction with diaminonaphthalene. Keap1-4–95 and the lead compound NXPZ-2 superimposed very well and all the residues were involved in the interactions (Fig. 2K). Two possible binding poses of 4–95 and Keap1 in a surface mode showed the phosphodiester amino acid located at the solvent exposed part as expected (Fig. 2L). The results of sequence alignment showed that both Keap1 and Nrf2 are highly conserved protein between human and mice, which were approximately 85 % and 94 % identical for Nrf2 (Fig. S2A) and Keap1 (Fig. S2B), respectively. Molecular docking study was performed to show the molecular interactions between mouse Kelch domain and 4–95. Notably, very similar binding features like those in human Keap1 were characterized (Figs. S2C–F).

The microscale thermophoresis (MST) was performed to evaluate the binding activity of 4–95 and Keap1 protein. 4–95 at different concentrations was incubated with Keap1, and the binding curve of 4–95 and protein was detected to determine a KD value of 343 nM (Figs. S3A–B). Next, to confirm the non-covalent binding characteristic of 4–95, a dialysis-based fluorescence anisotropy assay was conducted, as our previous study [48]. After incubation and dialysis, the dialyzed Keap1 protein retained its ability to bind to 4–95, and the dissociation constant (KD2) value was comparable to the previous measurement (Fig. S3C). These results strongly suggested that 4–95 bound to the Keap1 protein in a reversible manner. Furthermore, we evaluated whether 4–95 underwent a Michael addition reaction with glutathione (GSH) under the physiological temperature condition. As shown in Figure S3D, 4-95, and GSH remained stable throughout a 48-h observation period. The concentrations of neither 4–95 nor GSH showed significant decrease, suggesting the absence of a reaction between the two. All these results illustrated that 4–95 could non-covalently bind to the Keap1 protein.

2.3. 4–95 shows significant in vitro anti-OS activities by specifically activating the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway

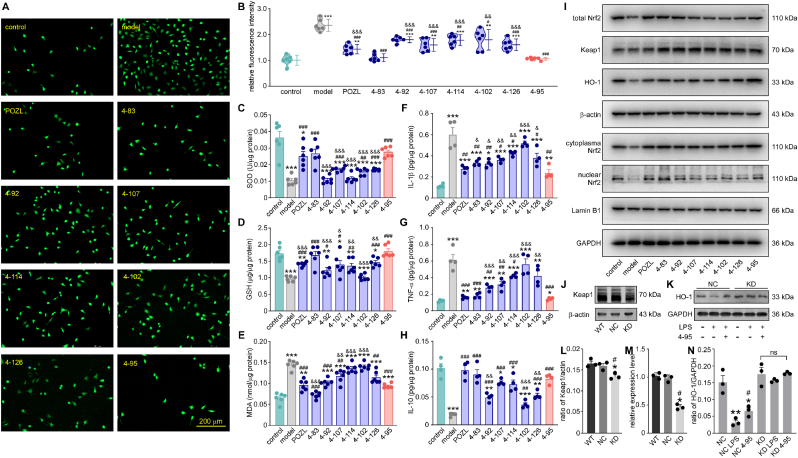

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was a common tool to induce OS and inflammation damage in vivo and in vitro. Here, the anti-OS activities of the derivatives were studied in an LPS-stimulated SH-SY5Y cell model. We measured intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) staining after compound treatments at a concentration of 10 μM. The results showed that 100 ng/mL LPS produced a large number of oxygen free radicals in SH-SY5Y cells, stained by the green fluorescence (P < 0.001, Fig. 3A). All the compounds were non-toxic at 100 μM (data not shown) and could reduce the ROS level to varying degrees (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 3B). Among them, the relative fluorescent intensity of 4–95 treatment was the lowest, suggesting the strongest ability to inhibit the production of ROS (P < 0.001, Fig. 3B). Some factors, involved in OS or anti-OS process, were also measured in cell lysate. GSH and SOD are both endogenous scavenger of the free radicals, reflecting the state of OS. With the treatment of compounds, the activities of SOD (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 3C) and GSH (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 3D) were significantly recovered in the LPS-stimulated cells, indicating the decreasing of oxidative stress in vitro. Malondialdehyde (MDA), one of the indicators of lipid peroxidation, was increased in LPS group, and was decreased with different treatments (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 3E). Among them, 4–95 showed the highest ability to increase these two anti-oxidants, and reduce the content of MDA, suggesting its better anti-OS ability than the analogues (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 3C–E). At the same time, two inflammatory factors, interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), were increased after LPS stimulation (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 3F and G). On the opposite, IL-10, a cytokine with anti-inflammatory properties, was decreased in the LPS-induced SH-SY5Y cells (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 3H). 4–95 showed the ability to inhibit the inflammation, as reflected by the reduction levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, along with the increased level of IL-10 (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 3F–H). However, some other compounds, such as 4–92 and 4–102, did not ameliorate LPS-induced damage in cells. These results initially illustrated that 4–95 showed the excellent potency to improve the oxidative and inflammatory condition.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the compounds on the capabilities of anti-oxidation and anti-inflammation in LPS-induced SH-SY5Y cells. control: cells were cultured under normal condition without LPS nor compound. model: cells were treated with 100 ng/mL LPS. The compound number: cells were treated with 100 ng/mL LPS and 10 μM compound. (A) Immunofluorescence of SH-SY5Y cells under different culture conditions, stained with DCFH-DA (green). Scale bar = 200 μm. (B) The relative immunofluorescence intensity of ROS in SH-SY5Y cells under different culture conditions. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6). The concentrations of SOD (C), GSH (D), and MDA (E) in the cell lysates with kits. The concentrations of IL-1β (F), TNF-α (G), and IL-10 (H) in the cell lysates with kits. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4–6). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs control. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs model. && P < 0.01, &&& P < 0.001 vs 4–95. (I) The protein expression levels of total Nrf2, Keap1, HO-1, nuclear Nrf2, cytoplasm Nrf2, Lamin B1 and GAPDH in the cell lysates at different culture conditions. (J) The expression levels of Keap1 in SH-SY5Y cells (WT), SH-SY5Y cells transfected with lentiviral vector (NC), and SH-SY5Y cells with Keap1 KD. (K) The expression level of HO-1 in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with lentiviral vector (NC), and SH-SY5Y cells with Keap1 KD under different culture conditions. (L) The density ratio of Keap1 to β-actin. (M) The RNA levels of Keap1 in SH-SY5Y cells (WT), SH-SY5Y cells transfected with lentiviral vector (NC), and SH-SY5Y cells with Keap1 KD. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05 vs WT. #P < 0.05 vs NC. (N) The density ratio of HO-1 to β-actin. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs NC. #P < 0.05 vs NC LPS.

Next, we further examined the expression levels of some key molecules in the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Keap1 expression was not changed in all groups as assumed (P > 0.05, Fig. 3I, S4B). Nrf2, extracted from whole cell lysates, was decreased in LPS-treated cells, while it was restored with different treatments to varying degrees (P < 0.05, Fig. 3I, S4A). Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), a Nrf2-regulated gene and crucial for preventing OS and inflammation, showed reduced expression levels in LPS-treated cells. However, upon treatments with specific compounds, the expression levels of HO-1 were increased (P < 0.01, Fig. 3I, S4C). The expression changes suggested the activation of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Compared with other compounds, 4–95 showed better ability to activate the pathway, with more expressions of total Nrf2 and HO-1 (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, Fig. 3I, S4A-C). Then, the Nrf2 cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted from cells under different conditions. As a result, both the cytoplasm and nucleus protein levels of Nrf2 were markedly decreased in model group, which were increased in 4–95 treatment group (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, Fig. 3I, S4D-E). More importantly, the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasm Nrf2 was increased in 4–95 treated-cells, suggesting that 4–95 promoted Nrf2 to enter the cell nucleus (P < 0.01, Fig. 3I, S4F). The result identified Nrf2 nuclear translocation and activation of Nrf2-targeted genes by 4–95 treatment in vitro. To further confirm the target of 4–95, we established Keap1 knockdown SH-SY5Y cell line (KD) by shRNA (Fig. 3J, 3L, 3M). 4–95 had no impact on HO-1 expression of the KD cells treated with LPS (Fig. 3K and N), further suggesting Keap1 as the action target of 4–95.

The BV-2 cell line was used to further analyze the anti-oxidative and anti-neuroinflammatory effect of 4–95. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. Subsequently, treatment with 4–95 led to significant increases in the nuclear protein levels of Nrf2 (P < 0.001, Figs. S5A and S5D) and the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasm Nrf2 level (P < 0.001, Figs. S5A and S5F). The expression level of HO-1 in total cell lysate was increased in 4-95-treated cells (P < 0.05, Figs. S5A and S5C). However, the expression levels of Keap1 and the cytoplasm Nrf2 were not changed (Fig. S5A–B, S5E). In addition, 4–95 increased the levels of SOD and GSH, decreased the level of MDA, suggesting that 4–95 decreased OS in microglial cells (P < 0.001, Figs. S5G–I). The inflammatory factors, IL-1β and TNF-α, were decreased after 4–95 treatment, and the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 was increased (P < 0.001, Figs. S5J–L), which showed consistent results with the SH-SY5Y cell line.

2.4. 4–95 treatment improves the depressive behavior and serum neurotransmitter levels in a CUMS mouse model

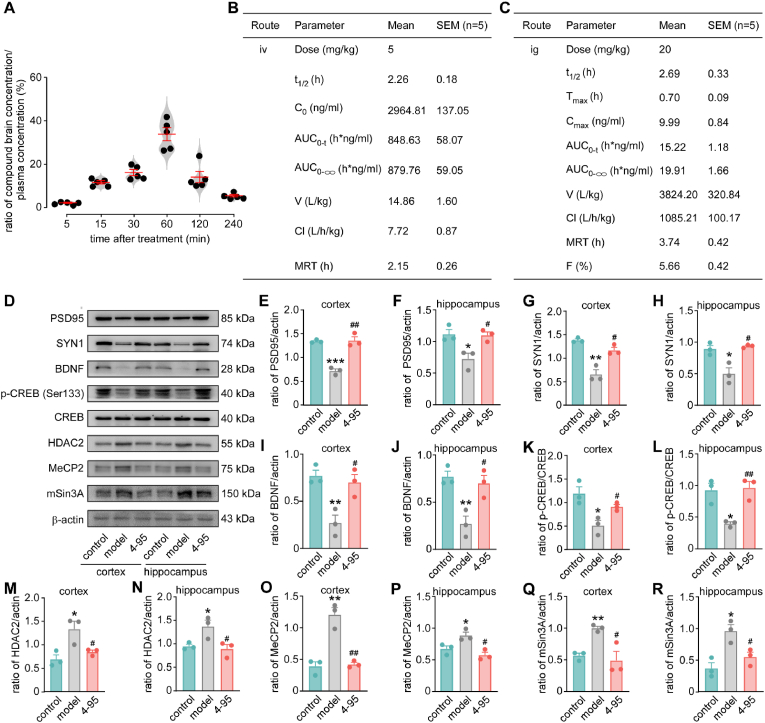

First, 8-week male C57BL/6J mice were used to study the BBB permeability of 4–95. Five mice at each time point were orally treated at a dose of 20 mg/kg (solution, 3 % Tween-80 + 0.5 % CMC-Na +96.5 % normal saline). Animals were euthanized and their blood and brains were collected at different time points. After treatment, the ratio of 4–95 concentration in the brains to that in the plasma was continuously increased over time, reaching a peak with a ratio of (33.87 ± 6.75 %) at 60 min, showing an acceptable brain penetration as the standard [[49], [50], [51]]. Subsequently, the concentration was decreased and reached (5.50 ± 1.26 %) at 6 h (Fig. 6A). Then, the basic pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters of 4–95 in the male Han Wistar rat via single intravenous (5 mg/kg) (Fig. 6B) or oral (28 mg/kg) (Fig. 6C) treatment were determined. The results showed that the oral bioavailability was not very high but still acceptable in this diaminonaphthalene series (F = 5.66 ± 0.42 %) (Fig. 6C). All these data supported the possibility for subsequent evaluation of 4–95 on neuropsychiatric diseases.

Fig. 6.

The basic PK properties of 4–95, and the effect of 4–95 on the synaptic function marker proteins and BDNF pathway in the brains of CUMS mice.

control: mice were cultured under normal condition without modeling nor treatment. model: mice underwent the CUMS protocol. 4–95: mice were subjected to the CUMS model and administered 4–95. (A) The ratio of brain compound concentration to blood compound concentration in male C57BL/6J mice. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5/each time point). The PK parameters of 4–95 after intravenous (iv) (B) or intragastric (i.g.) administration (C) in SD rats. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5). The expression levels of PSD95, and SYN1 in the frontal cortex (D, E, G) and hippocampus (D, F, H). The expression levels of BDNF, CREB, p-CREB, HDAC2, MeCP2, and mSin3A in the frontal cortex (D, I, K, M, O, Q) and hippocampus (D, J, L, N, P, R). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs control. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs model.

The CUMS paradigm, a widely adopted animal model for MDD, effectively simulated depressive behavior in mice [52] (Fig. 4A). Exposed to different stressors for 6 weeks, the CUMS mice (model) displayed characteristic depressive-like symptoms, including a shorter total distance of movement (P < 0.001, Fig. 4B), a shorter activity time through central area (P < 0.001, Fig. 4C), as well as decreased grooming times in the open field test (OFT) (P < 0.001, Fig. 4D). The track map was shown in Fig. 4E. The elevated plus maze (EPM) is an experimental method for evaluating anxiety responses in rodents. CUMS mice spent less time and fewer entry times in opened arm (P < 0.001, Fig. 4F–H). Novelty-suppressed feeding (NSF) experiment was used to evaluate the interest in food intake and appetite [53]. In this test, CUMS mice took significantly longer to take the first bite of food in the novel environment than control mice (P < 0.001, Fig. 4I), and they consumed less food in the subsequent 30 min (P < 0.001, Fig. 4J). Typically, normal rodents have a strong natural desire for sweet foods. However, depressive rodents display anhedonia, a core symptom of depression, which can be tested through sucrose preference test [54]. Despite all groups showed similar fluid intake volume after water and food deprivation for 24 h (P > 0.05, Fig. 4K), the CUMS group showed a reduced preference for the sucrose solution (P < 0.001, Fig. 4L), indicating the presence of anhedonia. Another important feature of depression was hopeless feelings, which was observable in the tail suspension test (TST) [55]. The first immobility was decreased, and the immobility time was increased in CUMS mice (P < 0.001, Fig. 4M and N), showing “behavioral despair” of the depressive animals. After 4-week CUMS modeling, mice in the treatment group were orally given 4–95 at a daily dose of 20 mg/kg (Fig. 4A). Concurrently, both the model and treatment groups continued to receive various stressful stimuli for another 2 weeks (Fig. 4A). At the end of 6-week modeling, treatment group was administrated with 4–95 continuously for 2 weeks (Fig. 4A). The results showed significant improvements on emotional and behavioral symptoms following treatment. Compared with the model group, the total distance of movement (P < 0.001, Fig. 4B), activity time through central area (P < 0.001, Fig. 4C), and the grooming times (P < 0.001, Fig. 4D) were all increased in 4–95 group, suggesting that the depression and anxiety were reduced. The percentage of time spent in opened arms and opened arm entries were increased (P < 0.001, Fig. 4F–H). The appetite (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 4I and J), and the pleasure for sweet (P < 0.001, Fig. 4K and L) were restored. The desperate behavior was also improved, reflected by longer latency of first immobility and less immobility time (P < 0.001, Fig. 4M and N).

Fig. 4.

The effect of 4–95 on the depressive phenotype in the CUMS mouse model. first sentence of legend ‘were received’ appears twice - this should be corrected. control: mice were cultured under normal condition without modeling nor treatment. model: mice underwent the CUMS protocol. 4–95: mice were subjected to the CUMS model and administered 4–95. (A) Schematic of CUMS model and the schedule of treatment (20 mg/kg). (B) The total travel distance during OFT. (C) The central travel distance during OFT. (D) The grooming times during OFT. The trajectory in OFT (E) and elevated plus maze (EPM, F). (G) The percentage time spent in opened arm in EPM. (H) The percentage of open arm entries in EPM. (I) Latency to feeding in NSFT. (J) The food consumption in 30 min in NSFT. (K) The total fluid consumption in SPT. (L) The percentage of sucrose consumption in SPT. (M) The latency of the first immobility in TST. (N) The percentage of duration of total immobility inTST. The concentrations of corticosterone (O, R), NA (P, S), and 5-HT (Q, T) in the hippocampus and cortex with kits. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 8–17). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs control. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs model.

In addition to behavioral alterations, depressive conditions also lead to changes in the levels of critical neurotransmitters and hormones [56]. Corticosterone, cortisol, 5-HT, and NA in blood, hippocampus, and cortex were measured using ELISA. The levels of corticosterone and cortisol, two typical stress hormones, were increased in CUMS mice, indicating high stress states in model group (P < 0.001, Fig. 4O and R, S6A, S6D-F). 5-HT and NA, two neurotransmitters influencing the mood, were reduced in model group (P < 0.001,Fig. 4P, 4Q, 4S, 4T, S6B-C). 4–95 treatment reduced the levels of corticosterone and cortisol, and increased the levels of 5-HT and NA, suggesting that the imbalanced neurotransmitter levels were restored (P < 0.001, Fig. 4O–T, S6). These findings, along with the behavioral experiments, provided evidence that 4–95 treatment effectively improved the anxiety and depression phenotype in CUMS mice.

2.5. 4–95 treatment decreases OS by activating Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in CUMS mice

Based on our previous bioinformatics analysis, we have demonstrated elevated levels of OS in the peripheral blood and brain tissues of MDD patients (Fig. 1). The cell-based model indicated that Nrf2 pathway was activated by 4–95 (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5). We further investigated the presence of certain anti-oxidants and oxidants in the serum of CUMS mice. Compared with the control mice, the serum levels of SOD, and GSH in CUMS mice were significantly reduced (P < 0.001, Fig. 5A–B). MDA in the serum of CUMS mice was elevated (P < 0.001, Fig. 5C), suggesting a state of high OS in depressive animals. 4–95 treatment led to increased levels of SOD and GSH, a reduced level of MDA (P < 0.001, Fig. 5A–C), which indicated that OS was ameliorated. The related RNA levels in whole blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) were measured. The results showed that RNA levels of Nfe2l2, Hmox-1, and Nqo1 were increased after 4–95 treatment (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, Fig. 5D–G), suggesting activation of Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in the peripheral. Next, the levels of Nrf2 and Nrf2 translocation were investigated in the cortex and hippocampus of mice. The results revealed that the expression levels of total Nrf2, as well as the two downstream anti-oxidative proteins, HO-1, and NQO1, were decreased both in the hippocampus and cortex of CUMS mice (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, Fig. 5H, S9A-B, S9E-H). Consistently, the expression levels of Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 in total cell lysate were increased in the hippocampus and cortex of 4-95-treated mice (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, Fig. 5H, S9A-B, S9E-H). The nucleus Nrf2 (P < 0.05, Fig. 5H, S9I-J) and the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasm Nrf2 (P < 0.01, Fig. 5H, S9M−N) were markedly increased in 4–95 treatment group. The Keap1 levels were expectedly similar to those three groups (P > 0.05, NS, Fig. 5H, S9C-D).

Fig. 5.

Effects of 4–95 on the Keap1- Nrf2 pathway in the serum and brains of CUMS mice. control: mice were cultured under normal condition without modeling nor treatment. model: mice underwent the CUMS protocol. 4–95: mice were subjected to the CUMS model and administered 4–95. The concentrations of SOD (A), GSH (B), and MDA (C) in the mouse serum with kits. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 10). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs control. ###P < 0.001 vs model. The RNA levels of Nfe2l2 (D), Hmox-1 (E), Keap1 (F), and Nqo1 (G) in whole blood and PBMC. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs control. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs model. (H) The protein expression levels of Nrf2, Keap1, HO-1, and NQO1 in the frontal cortex and hippocampus. (I) The Nrf2-ARE binding affinity determined by an EMSA in the hippocampus and cortex. (J) Immunofluorescence of brain slices of different groups stained with Nrf2 (red), Keap1 (green), and nuclear (DAPI, blue). Scale bar = 100/30 μm.

Besides, the results of electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showed that the binding of Nrf2 to the downstream antioxidant response element (ARE) was also increased in hippocampus and cortex of mice after 4–95 treatment (Fig. 5I). Immunofluorescence showed less co-localization of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the brain slices of 4–95 treated mice, demonstrating that 4–95 inhibited the interaction between Keap1 and Nrf2 to reduce the OS in depressive mice brains (Fig. 5J). These results supported that 4–95 treatment increased Nrf2 nuclear translocation and activated Keap1-Nrf2 pathway to reduce the OS in CUMS mice. This finding aligned with the observations in vitro (Fig. 3).

2.6. 4–95 treatment improves the synaptic function by activating Nrf2-BDNF pathway in CUMS mice

As the anxiety and depression behavior improved, we tested the biomarkers of neuron synaptic function. PSD95 is a pivotal postsynaptic scaffolding protein in excitatory neurons, playing a key role in bidirectional synaptic plasticity [57]. Besides, SYN1 acts as a regulator of synaptic vesicles trafficking, involved in the control of neurotransmitter release at the pre-synaptic terminal [58]. After 6-week CUMS modeling, the expression levels of PSD95 (P < 0.001, Fig. 6D–F) and SYN1 (P < 0.05, Fig. 6D, 6G–H) were decreased, which were recovered by 4–95 treatment (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, Fig. 6D–H). These results suggested that 4–95 improved both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic function. Neurotrophins such as BDNF, serves as an important factor in the physiological synaptic plasticity, pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental, psychiatric, and neurological conditions [59]. We found that the level of BDNF was reduced in model group, indicating impaired neuronal signaling transmission in depressive mice (P < 0.01, P < 0.01, Fig. 6D, 6I–J). 4–95 up-regulated BDNF expression in the hippocampus and cortex of CUMS mice, which further demonstrated the ameliorated effect on synaptic function (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, Fig. 6D, 6I–J). The expression of BDNF can be influenced by many transcription factors. CREB, has been reported to be one of the most major factors to regulate BDNF [60]. The phosphorylation level of CREB (p-CREB) stands for the degree of its activation. We found that the expression of p-CREB was decreased in the hippocampus and cortex of CUMS mice (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, Fig. 6D, 6K–L). Whereas, 4–95 increased p-CREB, which further illustrating the activation of CREB/BDNF pathway (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, Fig. 6D, 6K–L). Besides, BDNF expression can be regulated by some transcriptional repressor complex, which are formed by Methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2), mSin3A and histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) [61]. We found that CUMS significantly increased the levels of HDAC2 (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, Fig. 6D and 6M−N), M eCP2 (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, Fig. 6D, 6O–), and mSin3a (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, Fig. 6D, 6Q–R) in the hippocampus and cortex, and 4–95 treatment restored the expression levels (Fig. 6D, 6M–R). The above results revealed that Nrf2 regulated the transcription of BDNF by promoting the phosphorylation of CREB, and inhibiting the expression of its transcriptional repressors (HDAC2, mSin3A, and MeCP2) and ameliorating abnormal synaptic transmission.

3. Discussion

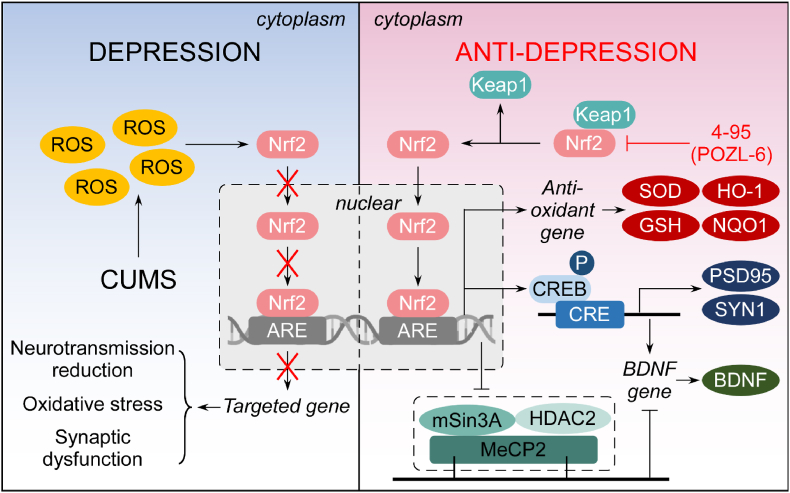

Our findings reveal that Nrf2 and the targeted anti-oxidative pathways were down-regulated in hippocampus and cortex of the CUMS mice, causing increased OS, synaptic dysfunction, and neurotransmission reduction. Pharmacological activation by Keap1-Nrf2 inhibitor 4–95 improved the depression behavior in vivo, through decreasing oxidative and inflammatory factors. As a result, the phosphorylation level of CREB was up-regulated, and the transcriptional repressor complex, consisted of MeCP2, mSin3A and HDAC2, was down-regulated, which increased the expression of BDNF to improve the synaptic function. A schematic representation of these findings is depicted in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The effect and mechanism of 4–95 on the CUMS model.

This study developed a novel series of phosphodiester amino acidic diaminonaphthalene compounds as Keap1-Nrf2 PPI inhibitors. The 1,4-diaminonaphthalene scaffold was firstly developed by our group and we validated this compound as a Keap1-Nrf2 inhibitor, possessing good effects on an AD mouse model [43]. Further optimizations on reducing the dosage and improving permeability of the inhibitors led to a new phosphodiester containing diaminonaphthalene compound, POZL [29]. This compound showed high efficacy at 40 mg/kg (NXPZ-2, 210 mg/kg) in a transgenic AD mice model, however, still limited permeability and oral bioavailability were observed. Besides, based on the co-crystallography on Keap1 and inhibitor, the unsymmetric compound was designed and successfully increased the bioavailability or water solubility, with great anti-inflammatory activity, such as compound 6k (F = 20 %, highest in the series to date) and 10u [44,45]. In the present study, we introduced amino acids to the phosphodiester side of POZL, because the amino acid should be a good moiety to improve BBB permeability and water solubility [44,47,[49], [50], [51]]. The PK profile and BBB penetration ability of the best compound 4–95 have been preliminarily investigated. 4–95 had a half-life of about 2.26 h in the intravenous administration. Although the oral bioavailability of 4–95 was a little higher than POZL, the ability of 4–95 to penetrate BBB increased significantly with a good ratio in the brains (>30 %) and quickly reached a peak concentration. Moreover, we performed several experiments, including MST, dialysis, and a Michael addition reaction with GSH, to show that amino acid modification did not change the target of the 1,4-diaminonaphthalene scaffold. The results validated the Keap1-Nrf2 PPI inhibitory mechanism of compound 4–95 in vitro.

The SH-SY5Y cell is a human-derived neuroblastoma cell line to study neuropsychiatric disorders [62] and the BV2 cell line is a immortalized microglial cell line for neuro-inflammatory research [63]. The LPS induced SH-SY5Y and BV2 cell injury models were used to analyze the ability of each compound against OS and inflammation, for selecting the most suitable compound for in vivo studies. Under the same concentration, the levels of ROS, MDA, IL-1β, and TNF-α were decreased in 4–95 treated SH-SY5Y cells, while SOD, GSH, and IL-10 were increased, suggesting a better capacity of 4–95 to reduce OS and inflammation. The similar results were shown in BV2 cell model stimulated with LPS. With 4–95 treatment, some anti-oxidants were up-regulated, the oxidant molecule was down-regulated, anti-inflammation factor was increased, and inflammatory factors were decreased. 4–95 promoted the expression and translocation of Nrf2. Combined with the in vitro results and the PK features, 4–95 might show potential values in oxidative-related or inflammatory-related central nervous system (CNS) disease.

CUMS is a commonly used animal model of depression in which animals are exposed to chronic unpredictable environmental and psychological stressors to mimic daily human life stressors [64]. Many studies have showed that the timing of exposure to chronic stress and the specific type of stress experienced are both critical factors, significantly influencing the behavioral and physiological outcomes in an organism [65,66]. In this study, depressive and anxious behaviors persisted, and typical neurotransmitter levels have also changed 6 weeks after modeling, which lasted until 2 weeks after the stress stimulation ended. Especially, CUMS caused OS as previous reports, suggesting the suitable model in this study [67]. Despite significant progresses in pharmacological treatments, attaining remission remains a significant challenge, as a considerable portion of patients exhibit resistance to current therapeutic modalities [68]. To some extent, the resistance correlates with increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, indicating a connection among inflammation, MDD pathophysiology, and treatment effectiveness [69]. We analyzed two gene expression profiles from human samples (GSE190518 and GSE101521) and one from mouse (GSE151807) related to depression. Nrf2 (NFE2L2) and many of Nrf2-targeted genes, such as NQO1, TXN, GSTM1, and HMOX1, were found both in the brain and the peripheral blood cells of MDD patients, and in depressive mice. Some inflammation related pathways, such as IL-17 signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway and NF-κB signaling pathway, were changed in MDD patients. Other researchers also found that patients and rodents with depression exhibit typical features of oxidative and inflammatory response, including increased expressions of oxidative molecules, pro-inflammatory factors, and pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage phenotype in peripheral blood [70]. All these findings identified that OS and inflammation were up-regulated in the brain tissues and peripheral blood. Our results, for the first time, confirmed the Keap1-Nrf2 PPI inhibitors could act as an anti-depressive agent. With 4–95 treatment, the anxiety and depression in CUMS mice could be effectively improved. 4–95 also showed the ability to reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNF-α, and increase the level of an anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10.

In CUMS mice, we found the high levels of stress hormones, corticosterone and cortisol, and the low levels of monoamines, 5-HT and NA, which suggested a stressful condition and an impaired monoamine system. The monoamine hypothesis, one of the most prevalent hypotheses, predicts that the underlying pathophysiologic basis of depression is a depletion in the levels of 5-HT, NA, and/or dopamine. However, this hypothesis cannot conclusively establish a connection between the acute biochemical action of antidepressants on monoamine levels and their delayed clinical efficacy. Additionally, it fails to explain the mechanism of some antidepressants with weak action on monoamine [8]. However, other possible pathological mechanisms have been proposed. Recently, many studies have suggested that OS plays an important role in the pathology of MDD, and Nrf2 is an important therapeutic target of MDD. The high level of OS was found in patients with a depression status, and there was a significant relationship between duration of illness, the number of episodes, and MDA, Nrf2, and SOD levels [71,72]. OS is also recognized as the link with the stress response, neuroinflammation, and synaptic plasticity in depression [22]. The serum GSH and SOD were reduced, and MDA was increased in model mice. The transcription levels of Nrf2, NQO1, and HO-1 in whole blood and PBMC were decreased in model mice. The expression levels of total Nrf2 and nuclear translocation of Nrf2 were also decreased in the hippocampus and cortex, suggesting a high OS status in depressive mice. Several different results showed increased nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and activation of Nrf2-targeted genes in blood and brain tissues of 4–95 treated mice from different aspects. Western blot results showed that both total Nrf2 and Nrf2 translocation levels were increased in the frontal cortex and hippocampus, as well as the expression levels of the downstream anti-oxidative genes, such as HO-1, and NQO-1, in 4-95-treated mice. The degree of OS (e.g. MDA) was decreased, and anti-oxidants (e.g. SOD, GSH) were increased. The binding of Nrf2 and ARE was increased detected by EMSA. The immunofluorescence of brain slices demonstrated that 4–95 inhibited the interaction between Keap1 and Nrf2. Besides, RNA levels of Nfe2l2, Hmox-1, and Nqo1 were increased in the whole blood and PBMC after 4–95 treatment. All these findings demonstrated that Nrf2-Keap1 pathway was activated both in the periphery and CNS. Nrf2 is well-known for its role in orchestrating the body's antioxidant response, and its activation in peripheral tissues can lead to the release of various signaling molecules capable of impacting CNS function. Emerging evidence indicated that peripheral activation of Nrf2 can modulate systemic inflammation, increase the production of neuroprotective factors, and potentially affect neuronal health indirectly. Moreover, it is crucial to recognize that the concentration of 4–95 achieved in the brain, even if modest, may be sufficient to elicit significant neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory outcomes, particularly when combined with the systemic activation of protective pathways. This may provide deeper insights into the therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activators, emphasizing the need for integrated approaches that consider both central and peripheral mechanisms of action. Besides, 4–95 reduced corticosterone, and cortisol levels, and increase 5-HT, and NA levels. Our current hypothesis is that 4–95 reduced OS to recover the function of HPA-axis, and recover 5-HT/NA neuron function to increase 5-HT/NA synthesis. However, future investigation is needed to test this hypothesis.

Synaptic plasticity of neurons was considered as a fundamental index for brain function [73]. In 4–95-treated group, the expression levels of PSD95 and SYN1 were increased, suggesting the recovery of presynaptic and postsynaptic transmission function. Among the members of the neurotrophic family, BDNF stands out for its ability to regulate synaptic plasticity [74]. Here, we found BDNF increased after 4–95 treatment, further demonstrating the improvement effect of 4–95 on neuronal function and depressive behavior [59]. CREB is a transcription factor to control the expression of BDNF, that has been linked to depression and antidepressant-like responses [75]. The expression of BDNF was also regulated by the transcriptional repressor complex, formed by MeCP2, mSin3A, and HDAC2 [76]. The results showed that 4–95 increased the phosphorylation level of CREB, and inhibit the expression levels of MeCP2, mSin3A, and HDAC2. Taken together, activation of Nrf2 signaling pathway reduced OS, promoted the expression of BDNF by two transcriptional regulators, and enhanced the synaptic function through up-regulation of PSD95 and SYN1, which finally ameliorated the depressive phenotype.

There might be potentially some limitations to our investigation. Firstly, it should be mentioned that the 1,4-diaminonaphthalene scaffold, occupying the Keap1 Kelch binding pocket with a high affinity, should have a symmetric conformation and a high molecular weight. These will inherently lead to unsatisfactory molecular properties, especially low solubility, BBB permeability and bioavailability [45]. Here, we attempted to try our strategy to unsymmetrically introduce substituents, e.g. amino acids, pseudo amino acids, and phosphodiesters, on the benzosulfamide moiety [29,[44], [45], [46]]. The strategy obtained novel active Keap1-Nrf2 inhibitors with improved bioavailability, permeability (B/P > 0.3), and solubility. However, it is still challengeable to optimize the compounds or perform pharmaceutical changes to advance it into clinical studies. Secondly, the mammalian brain consists of millions to billions of cells of many different cell types, and different cells own specific structural and functional properties and spatial distribution in the brain [77]. Gene expression profiles (GSE190518, GSE101521, and GSE151807) analyzed in this study were used conventional RNA sequencing, which was difficult to characterize complex regulation between cells. Further, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), or single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) might dissect the functions of different cell types more precisely [78,79]. Thirdly, in order to obtain more accurate data about compound permeable ability into the brain, there might be a need to use a real-time dynamic microdialysis system to collect cerebrospinal fluid from one conscious animal at different time points after a single-dose treatment. Lastly, synaptic plasticity is one of the fundamental processes and the cellular basis of higher brain functions such as learning, memory, and emotions [73]. We mainly focused on the expression levels of some proteins related to synaptic plasticity. However, other techniques, such as electrophysiology, might reveal synaptic function and neurocircuitry under Nrf2 activation.

In conclusion, we designed and synthesized a novel Keap1-Nrf2 PPI inhibitor 4–95. This compound could be orally active to improve the anxiety and depression behavior and inhibit oxidative stress in the CUMS mouse model. This study demonstrated that Keap1-Nrf2 pathway is a viable therapeutic target of depression, and direct inhibition of the Keap1-Nrf2 PPI is a potential drug development strategy for MDD treatment. Further optimizations by medicinal chemistry and drug design will be utilized to develop more efficient Keap1-Nrf2 PPI inhibitors.

4. Methods

4.1. Keap1 binding assays

Fluorescent anisotropy. The equilibrium dissociation constants KD2 for POZL was determined using a fluorescence anisotropy assay with FITC-βAla-DEETGEF-OH as the fluorescence probe. The binding affinity of the probe was determined as KD1 in our previous studies [29,44,47]. The fluorescence anisotropy was measured on a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5) with 485 nm excitation and 535 nm emission after 60 min incubation at room temperature. Three independent experiments were performed.

Reversible binding analysis. This assay was used to confirm the non-covalent binding feature of the compound with Keap1. The compound was incubated with Keap1 for 1 h, and then the compound was removed by dialysis (Millipore, UFC801024). The ability of the dialyzed Keap1 protein to bind the fluorescence probe was then measured using the fluorescent anisotropy assay [48].

Microscale thermophoresis (MST). The purified Keap1 protein was diluted to 20 nM in 100 μL of phosphate buffer with 0.05 % Tween-20. Then, 100 μL of 100 nM RED-tris-NTA dye (Nanotemper, MO-L008) was mixed with the protein. After a 30-min room temperature incubation, the mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. The 10 mM compound in DMSO was diluted to 100 μM with buffer, followed by 15 half-serial dilutions to get 16 concentrations in 10 μL aliquots per well. A 10 μL mixture of protein and probe was added to each well, mixed, and incubated at room temperature for another 30 min in the dark. Using capillary tubes, 10 μL of the incubated mixture from each well was loaded into microthermostrobe (Monolith NT. 115). Data were processed with MO.Analysis software, and a curve was fitted to obtain the KD values.

Michael addition reaction. The compound (0.5 mg) was dissolved in DMSO (10 μL) to prepare a stock solution. The stock solution was then diluted in 1 mL of ultrapure water containing 25 mg GSH to create the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C in a water bath to simulate human body temperature. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to monitor the relative concentrations of compound and GSH at the following time points: 0, 1, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h with the condition of 5-85 % acetonitrile in water, 15 min, 3.5 mL/min.

4.2. Cell culture

SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12. All medium were supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (v/v), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. BV2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium, supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (v/v), 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. These two cell lines were grown at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2, and for all experiments, cells were harvested from exponentially growing cultures.

4.3. Establishment of Keap1 knockdown SH-SY5Y cell line

The lentivirus was customized as follows: LV-U6-shRNA1(scramble)-CMV-mCherry-T2A-Puro-WPRE (NC), and LV-U6-shRNA1(KEAP1)-CMV-mCherry-T2A-Puro-WPRE (KD) (Brainvta, Hubei, China). After the SH-SY5Y cell confluence reached 50 %, NC-lentivirus and KD-lentivirus were added to the cells respectively and cultured under the condition of 5 % CO2 and 37 °C. The complete medium containing puromycin (0.75 μg/ml) was used for selection after 48 h, until the cell positive rate reached more than 95 %. RT-qPCR and Western blot were used to identify the interference of polyclonal stable cell line.

4.4. ROS measurement

SH-SY5Y cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h and then exposed to the compounds (10 μM) for 24 h. DCFH-DA staining for analysis of ROS level were followed our previous study. The images were captured under fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany). The fluorescence intensity was measured by microplate readers (TECAN Safire2, Austria).

4.5. Biochemical assay

Cell lysates and mouse serum were used to test some anti-oxidative and oxidative factors, including SOD, GSH, and MDA, using kits purchased from Boxbio, Beijing, China. Some inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, including IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-10 were analyzed with ELISA kits from Keygen Biotech, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. The neurotransmitters, including corticosterone, cortisol, 5-HT, and NA, were analyzed with ELISA kits from CUSABIO, Hubei, China.

4.6. Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (7 weeks) were purchased from Yangzhou University Medical Center (Yangzhou, China). All animals were housed on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with free access to food and water. Mice were allowed to habituate to this environment for a week before experiments were performed. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China) conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication, eighth Edition, 2011).

4.7. Establishment of the CUMS mouse model

CUMS was performed as described previously with slight modifications. Briefly, male C57BL/6J mice were subjected to a continuous variety of mild stressors for a total of 6 weeks, including food/water deprivation (24 h), cage tilt (45°, 12 h), wet bedding (24 h), bedding deprivation (24 h), light-dark reversal (24 h), physical constraint (2 h), and forced swimming (4 °C, 5 min). During the CUMS procedure, only one stressor was conducted per day, and no single stressor was performed consecutively for two days. The control mice were handled daily in the housing room. During the last 2 weeks of CUMS, mice in the treatment groups were given 4–95 (20 mg/kg) orally until the behavioral experiments were completed.

4.8. Behavioral experiments

Open field test (OFT). The OFT was used to observe locomotion and anxiety-like behavior in mice. Mice were transferred to the testing room and allowed to habituate for 2 h prior to testing. Each mouse was initially placed in the center of the open field cage (50 × 50 × 50 cm) with a floor divided into 25 equal squares and allowed to freely explore for 5 min under dim light. Their behavior was recorded with a video tracking system positioned directly above the field. The following parameters were analyzed: total activity distance, time spent in the central fields, and grooming times.

Elevated plus maze (EPM). The EPM is a simple method for assessing anxiety responses of rodents. The apparatus consisted of two open arms (25 × 5 cm) and two closed arms of the same size with 15-cm-high walls and a central square (5 × 5 cm) connecting the arms. Each mouse was placed in the central square of the maze facing one of the opened arms, whose movement trajectory was recorded by a video tracking system. The percentage time spent in opened arm (%), and the percentage of open arm entries (%) were automatically measured during a 5-min test period.

Novelty-suppressed feeding test (NSFT). Before the test, mice were deprived of food for 24 h with free access to water. On the testing day, a piece of sweetened fruit cereal was placed on a piece of filter paper in the center of an area (100 × 100 × 40 cm). Mice were then placed in a random corner of the arena and latency to enter the arena center and feed was recorded in seconds. Mice that took longer than 300 s to take their first bite were eliminated from the test. Immediately after the mice took the first bite of the sweetened fruit cereal, they were removed from the arena and returned to their home cages. In the home cages, a pre-weighed piece of sweetened fruit cereal was provided to the mice for 30 min to measure their home cage consumption. The latency of first bite and food consumption within 30 min in the home cage were recorded.

Sucrose preference test (SPT). The mice were single housed and trained to consume 1 % sucrose from 2 bottles. Mice were first habituated with 2 bottles of plain water for 24 h, and then they were provided 2 bottles of 1 % sucrose for another 24 h. Following 24 h of water and food deprivation, mice were individually provided with two bottles of the same size: one containing 1 % sucrose solution and the other containing plain water. Bottle positions were switched in the middle of the test. The amount of each liquid consumed over 24 h was recorded. The total fluid intake volume = sucrose consumption + plain water consumption. The sucrose preference rate = sucrose consumption/(sucrose consumption + plain water consumption) × 100 %.

Tail suspension test (TST). Mice were individually suspended in the TST apparatus (Tail Suspension PHM-300, Med Associates Inc., USA) with paper adhesive tape placed approximately 1 cm from the tip of the tail. Their behavior was monitored using a video tracking system for 6 min. The latency to the first immobility and the immobility time were recorded. The immobility time was defined as the ratio of the time the mouse hung passively, or was motionless to total test time. Each mouse was ensured to be free from interference throughout the entire test.

4.9. The basic PK analysis of compound 4-95

After one week adaptation, the male Han Wistar rat, aged 8 weeks, via single intravenous (5 mg/kg, solution, 3 % Tween-80 + 0.5 % CMC-Na +96.5 % NS) or oral treatment of 4–95 (20 mg/kg, solution, 3 % Tween-80 + 0.5 % CMC-Na +96.5 % NS) were used for PK analysis. At different time points after the treatments, blood was collected and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 min to obtain the plasma.

Eight-week male C57BL/6J mice, weighing 22-25 g, received a single oral treatment at a dose of 20 mg/kg. At various specific time points (5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 min, n = 5/each time point), the animals were euthanized, and their brains and blood were collected for compound concentration detection according to our previous study.

4.10. Western blotting

Tissues obtained from the hippocampus and frontal cortex or cells were placed in RIPA lysis buffer, containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted from fresh tissues, following the kit instructions (Invent Biotechnologies. Inc., sc-003). Protein samples (30 μg) were separated with SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The membrane was blocked with blocking buffer (TBS, 0.1 % Tween-20, 5 % non-fat milk or 2 % BSA), for 2 h at room temperature, and incubated with primary antibodies against Nrf2 (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), Keap1 (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), PSD95 (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), HO-1 (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), NQO1(1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), SYN1 (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), BDNF (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), CREB (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), Phospho-CREB (Ser133) (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), HDAC2 (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), MeCP2 (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), mSin3A (1:1000, Selleck Chemicals, Shanghai, China), β-actin (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), Lamin B1 (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and GAPDH (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), at 4 °C overnight. The membrane was then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:10000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) or anti-mouse IgG (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 60 min at room temperature, respectively. The protein bands were visualized using an ECL kit (Epizyme Biotech Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), and scanned by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (4200 Chemiluminescent Imaging System, Shanghai Tanon Science & Technology Co. Ltd, China). Relative protein expression levels were quantified by optical density analysis (Quantity-One software, Bio Rad Gel Doc 1000, Milan, Italy), and normalized to GAPDH or β-actin.

4.11. Immunofluorescence

The brains were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were blocked with 5 % bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with the indicated primary antibodies against Nrf2 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA.), and Keap1 (1:100, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China) overnight. After incubation, brain sections were incubated with CoraLite594-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG(H + L) (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China), and CoraLite488-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG(H + L) (1:1000, Proteintech, Wuhan Sanying, Hubei, China) secondary antibodies. And then, the sections were placed with DAPI (Servicebio, Hubei, China) for 3 min to stain nuclei. Images were captured by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica). The fluorescence intensity was analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0, and co-localization analyses were performed using ZEISS.

4.12. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA samples were isolated by RNA-easy Isolation Reagent (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) using homogenizer; RNA concentrations and purities were assessed by measuring absorbance values at 260 nm and 280 nm. cDNA was synthesized using 2 μg of total RNA and KeyPo Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). PCR amplification was performed using Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed and analyzed using ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). For analysis of mRNA expression, the following primers were used: Relative expression was calculated using the ACT method and normalized to the beta-actin. Relative level of mRNA was calculated in comparison with control samples. Also, the primers are shown in Table S1.

4.13. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

To calculate the binding activity of Nrf2 with ARE, EMSA was performed using an EMSA kit (Beyotime, Nanjing, China). Briefly, nuclear proteins were extracted from mouse brain using a cytoplasmic/nuclear protein extraction kit (KeyGene BioTECH, Nanjing, China). The nuclear extracts were incubated with labeled probes for 60 min at room temperature. ARE probe sequences are as follows: 5′-ACTGAGGGTGACTCAGCAAAATC-3′, 3′-TGACTCCCACTGAGTCGTTTTAG-5’. Unlabeled probe was used for competitive hybridization. The binding reactions (20 μL) were electrophoresed in 6 % native polyacrylamide gel, and then electro transferred onto a nylon membrane. A UV lamp was used in the clean bench and the membrane was irradiated for 15 min at a distance of about 10 cm. Images were photographed with detection system (Tanon Science & Technology Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China).

4.14. Molecular modelling

The modeling study was carried out using Schrödinger Maestro 11.4. Protein is prepared by Schrödinger protein preparation wizard using a default parameter. The protein preparation followed a standard protocol: 1) addition of missing hydrogen atoms to the X-ray structure, 2) removal of all crystallographic water, 3) assignment of ionizable state to each titrable groups by PropKa, and 4) energy minimization using OPLS-AA 2005 force field to optimize all hydrogen-bonding networks. The docking study was performed using Glide. The small molecule, taking from the PDB structures, was re-docked into its corresponding protein structure at the Standard Precision (SP) without the need of any constraints. The stability of the simulation was assessed by monitoring the RMSD with respect to the minimized starting structure. The flexible docking method docks the ligand automatically into the ligand-binding site of the receptor by using a protocol-based approach and an empirically derived scoring function. The molecular docking result was generated using PyMol (http://pymol.sourceforge.net/).

4.15. Sequence alignment

The sequence alignment of Nrf2 and Keap1 in human and mouse was performed online (https://www.uniprot.org/align).

4.16. Public gene expression dataset analysis

Public gene expression data (GSE190518, GSE101521, and GSE151807) was downloaded as raw signals from Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The GSE190518 datasets was used on the GPL20301 platform (Illumina HiSeq 4000, Homo sapiens), while the GSE101521 datasets was generated on both GPL15520 platform (Illumina MiSeq, Homo sapiens) and GPL16791 platform (Illumina HiSeq 2500, Homo sapiens). And the GSE151807 dataset was used on the GPL1261 platform (Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array). “Limma” package (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) in R software was used to investigate DEGs, which were specified as “P-value <0.05 and log2 (fold change) > 1 or log2 (fold change) < −1” for GSE190518 datasets, and “P-value <0.05 and log2 (fold change) > 0.5 or log2 (fold change) < −0.5” for GSE101521 datasets. For visualization, the volcano plots were generated to show DEGs. Functional enrichment analysis was conducted to evaluate major biological attributes of DEGs, specifically including GO and KEGG pathway analysis using “ClusterProfiler” package (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html) in R software. Threshold was set at P-value <0.05. To functionally investigate the biological significance of signature genes, GSEA (version 4.1.0) was performed between normal and depressive patients by using “ClusterProfiler” package (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html) in R software.

4.17. Chemistry

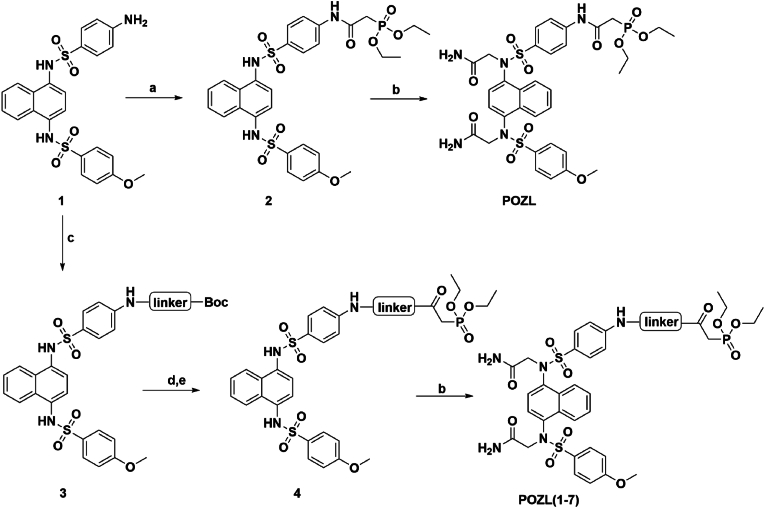

The synthesis of POZL derivatives is presented in Scheme 1. All solvents and starting materials, including anhydrous solvents and chemicals, were purchased from commercial vendors, and used without any further purification. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis was carried out on silica gel plates GF254 (Qingdao Haiyang Chemical, China). Column chromatography was carried out on silica gel 300–400 mesh. Nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR, 13C NMR) spectra were recorded in DMSO‑d6 on Bruker Avance 400/500/600 spectrometers (Bruker Company, Germany). Chemical shifts (δ values) and coupling constants (J values) are given in ppm and Hz, respectively, using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. High-resolution mass spectrometer (HRMS) data were acquired using a quadrupole time-of-flight micro mass spectrometer. The final structures were fully characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS. The spectra could be found in Supporting information. The compound was purified to >95 %, as determined by HPLC analysis, prior to use in biological evaluation.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route of POZL derivatives.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Diethylphosphoric acetic acid, HATU, Pyridine, 85 °C, 3h, 87 %; (b) 2-bromoacetamide, K2CO3, KI, dry DMF, 60 °C, overnight, 61–79 %; (c) Different types of N-Boc amino acids, HATU, pyridine, 85 °C, 3 h, 45–67 %; (d) TFA, DCM, room temperature, 2 h, 91 %; (e) Diethylphosphoric acetic acid, HATU, Pyridine, 85 °C, 3h, 87 %.

As shown in Scheme 1, to a solution of compound 1 (2.4 g, 4.96 mmol) in pyridine (15 mL), HATU (3.77g, 1.04 mmol), diethylphosphoacetic acid (1.19 mL, 7.44 mmol) was added at room temperature. The reaction was continued in 85 °C for 3 h, and TLC (DCM/MeOH = 30:1, Rf = 0.4) indicated that the reaction was completed. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (50 mL) and washed with water (30 mL × 2). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, dried to give the crude compound 2 (2.86 g, 4.32 mmol, 87 % yield) as a white solid. To a solution of the crude compound 2 (1.26 g, 1.9 mmol) in dry DMF (8 mL), K2CO3 (1.05 g, 7.6 mmol), KI (157.7 mg, 0.95 mmol), 2-bromoacetamide (919 mg, 1.05 mmol) were added at 50 °C, and then the mixture was stirred overnight. TLC (DCM/MeOH = 10:1, Rf = 0.2) showed that the reaction was completed. Water (10 mL) was added to the reaction mixture, and diluted with ethyl acetate (50 mL) and washed with saturated brine (30 mL × 2). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by flash column chromatography (DCM/MeOH = 20:1) on silica gel to afford the desired compound POZL (1.05 g, 0.18 mmol, 71.3 % yield) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 1.23–1.28 (m, 6H), 3.16 (dd, J = 21.64 Hz, J = 12.72 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (d, J = 22.00 Hz, 3H), 4.03–4.13 (m, 4H), 4.16–4.32 (m, 4H), 6.87 (dd, J = 18.80 Hz, J = 7.92 Hz, 1H), 6.95–7.07 (m, 4H), 7.13 (dt, J = 9.04 Hz, J = 2.96 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 19.20 Hz, 2H), 7.54–7.64 (m, 6H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.92 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.92 Hz, 1H), 8.16–8.23 (m, 1H), 8.28–8.33 (m, 1H), 10.57 (d, J = 29.80 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 168.8, 168.7, 163.8, 162.9143.1, 143.0, 137.1, 136.8, 133.2, 133.0, 132.1, 131.5, 130.2, 130.0, 129.4, 129.1, 129.0, 126.5, 126.0, 125.8, 124.8, 124.7, 118.5, 118.4, 114.2, 114.2, 62.0, 61.9, 55.9, 55.7, 54.0, 36.7, 35.4, 16.3, 16.2. HRMS (ESI, positive) m/z calcd for C33H38N5O11PS2 [M+H]+: 776.1827; found 776.1842, HPLC analysis: retention time = 7.5 min; peak area, >95 % (210, 254 nm).

Diethyl(2-((2-((4-(N-(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-((N-(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)-4-methoxyphenyl)sulfona-mido)naphthalen-1-yl)sulfamoyl)phenyl)amino)-2-oxoethyl)amino)-2-oxoethyl)phosphonate (4-83). Synthesized following the procedure of POZL, white solid (100 mg, 0.12 mmol, 65.3 % yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 1.23–1.26 (m, 6H), 3.02 (dd, J = 21.20 Hz, J = 9.90 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (d, J = 23.90 Hz, 3H), 3.95–4.00 (m, 2H), 4.01–4.08 (m, 4H), 4.12–4.31 (m, 4H), 6.85 (dd, J = 18.00 Hz, J = 7.95 Hz, 1H), 6.95–7.07 (m, 4H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.95 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 21.85 Hz, 2H), 7.54–7.62 (m, 6H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.80 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.95 Hz, 1H), 8.18–8.23 (m, 1H), 8.30–8.33 (m, 1H), 8.53 (q, J = 5.50 Hz 1H), 10.34 (d, J = 46.20 Hz, 1H).13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 168.8, 168.7, 168.6, 168.4, 164.9, 164.8, 162.9, 137.1, 136.8, 133.0, 132.8, 131.9, 131.4, 130.2, 130.0, 129.5, 129.3, 129.1, 129.0, 126.5, 126.0, 124.8, 124.7, 118.6, 118.5, 114.2, 114.1, 61.9, 61.8, 55.8, 55.7, 54.0, 43.2, 34.8, 33.8, 16.2, 16.1. HRMS (ESI, positive) m/z calcd for C35H41N6O12PS2 [M+H]+: 833.2041; found 833.2045, HPLC analysis: retention time = 6.6 min; peak area, >95 % (210, 254 nm).

Diethyl (R)-(2-((1-((4-(N-(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-((N-(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)-4-methoxyphenyl)sul-fonamido)naphthalen-1-yl)sulfamoyl)phenyl)amino)-1-oxopropan-2-yl)amino)-2-oxoethyl)phosphona-te (4–107). Synthesized following the procedure of POZL, white solid (100 mg, 0.12 mmol, 76.3 % yield). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 1.20–1.26 (m, 6H), 1.35 (dd, J = 20.88 Hz, J = 7.14 Hz, 3H), 2.96 -b 3.02 (m, 2H), 3.84–3.89 (m, 3H), 4.01–4.08 (m, 4H), 4.12–4.31 (m, 4H), 4.40–4.48 (m, 1H), 6.82–6.90 (m, 1H), 6.95–7.07 (m, 4H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.10 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 27.78 Hz, 2H), 7.54–7.62 (m, 6H), 7.80–7.82 (m, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 7.02 Hz, 1H), 8.21–8.23 (m, 1H), 8.30–8.34 (m, 1H), 8.48–8.52 (m, 1H), 10.33–10.42 (m, 1H).13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 171.8, 168.8, 168.7, 164.2, 162.9143.1, 143.0, 137.1, 136.9, 133.1, 133.0, 131.9, 131.3, 130.2, 130.0, 129.3, 129.0, 126.5, 126.4, 125.9, 124.8, 124.5, 118.8, 118.6, 114.2, 114.1, 61.9, 61.8, 55.8, 55.7, 54.0, 49.5, 34.7, 33.8, 17.8, 16.3, 16.2. HRMS (ESI, positive) m/z calcd for C36H43N6O12PS2 [M+H]+: 847.2198; found 847.2199, HPLC analysis: retention time = 6.7 min; peak area, >95 % (210, 254 nm).