Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the one of the most fatal and frequent form of urological malignancy worldwide. The von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumour suppressor gene is a critical component of the VHL-Cullin2-ElonginB/C (VCB) complex that regulates the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of proteins with mutations consistently associated with the development of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Despite extensive investigations conducted worldwide, there is a notable lack of data concerning VHL mutations in sporadic ccRCC patients from India. Our study aimed to investigate the sporadic VHL mutations within the tumours of 210 ccRCC patients without a familial history of VHL disease. We extracted genomic DNA from tumour and adjacent normal tissues, PCR amplified and sequenced the VHL gene. In silico tools were used assess the damaging potential of missense variants on pVHL structure and stability. Protein-protein docking and protein flexibility molecular docking simulation study were employed to study the interaction between wild-type and mutated VHL models with Elongin C. Sequence analysis revealed seven novel missense mutations in patient tumour tissues p.(Val170Phe), p.(Arg69Cys), p.(Phe76Leu), p.(Glu173Asp), p.(Leu201Val), p.(His208Leu), p.(Arg205Pro). I-Mutant 2.0 indicated these mutations reduced pVHL stability (ΔΔG < -0.5 kcal/mol). Protein Flexibility-Molecular Dynamic (MD) Simulation study indicated that mutations weaken the interaction of VHL with Elongin C, with V170F showing the most significant reduction in binding quality and stability. In conclusion, this study introduces novel genetic data from an understudied population and highlights the impact of VHL mutations on its interaction with Elongin C. These findings contribute to our understanding of the molecular basis of VHL-related pathologies and may guide future therapeutic strategies targeting these interactions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-95875-1.

Keywords: VHL, Renal cell carcinoma (RCC), Novel mutations, In silico, Protein flexibility modelling

Subject terms: Cancer genetics, Cancer, Computational biology and bioinformatics

Background

Kidney cancer is the most common form of human urological malignancy. Despite recent developments in diagnosis and treatment regimes, its prevalence has continued to rise globally1. The annual incidence of kidney cancer in India is 16,861, with a 5-year frequency of 2.84 per 100,000 people (GLOBOCAN, 2020). Moreover, ~ 90% of all kidney malignancies are renal cell carcinomas (RCC). RCC can be classified into distinct subtypes based on specific histopathological and genetic features, of which clear-cell RCC (ccRCC) is the most common (80–90%) and deadly subtype2. The most popular treatment for this disease is surgical ablation, but about 20–40% of patients experience recurrence and metastasis after surgery3. Radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy treatments for RCC have only modest therapeutic benefits3–6. In spite of treatment with new targeted and immune therapies, patients with metastatic ccRCC still have poor outcomes with a median progression-free survival of 15.1 months. Despite the regulatory clearance of many tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immunotherapies in India, there are no India-specific guidelines for ccRCC management or treatment7.

The VHL tumour suppressor gene, located at chromosome 3p25.3, is distributed over three exons and codes for 213 amino acids (ENST00000256474.3). It has been determined that the VHL gene product (pVHL), which consists of two domains, is a multi-adaptor protein that interacts with more than 30 distinct binding partners8. pVHL in conjunction with transcription elongation factors Elongin C and B, constitutes the VCB complex9. The VCB complex then interacts with CR protein conjugate [comprising Cullin-2 (CUL2) and the RING finger protein RBX1] forming the VCB-CR complex that functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase10, which targets hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF1α or HIF2α, also known as EPAS1) for polyubiquitylation and subsequent proteolytic degradation in normal physiological conditions11. HIFs participate in cellular oxygen detection and modulate the expression of genes like VEGF, PDGF, EPO, CA9 and CXCR4, known to be important in angiogenesis, cell proliferation and metastases12,13. In normoxic conditions, HIF-1α undergoes hydroxylation on two proline residues, facilitating its association with pVHL, which is followed by ubiquitination by the VCB-CR complex. In hypoxic settings, HIF-1α remains unhydroxylated, inhibiting negative regulation by pVHL, which allows active HIF-1α to promote the expression of hypoxia-related genes14,15. According to X-ray crystallographic studies of the VCB complex, VHL binds directly to Elongin C, while Elongin C, through a separate domain, binds to Elongin B, suggesting that Elongin B does not interact directly with pVHL16. VHL proteins with mutations in the Elongin-binding domain tend to be unstable and are rapidly degraded via the proteasome17. In fact, pVHL mutants unable to bind Elongin C complexes also fail to inhibit the accumulation of hypoxia-inducible mRNAs, underscoring the importance of the VHL-Elongin C interaction for tumour suppression18. Studies also show, germline or somatic VHL mutations that disrupt pVHL’s binding to Elongin C lead to HIF stabilization and activation of hypoxic-gene response pathways, promoting tumour progression19, suggesting that the interaction of VHL with Elongin C is crucial for its tumour-suppressing activities.

The deletion or mutation of the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) gene is generally recognised as one of the crucial early stages in the development of ccRCC20. According to studies, the VHL gene is down-regulated in more than 80% of cases of ccRCC, either by mutations (70–80%), promoter methylation (19%), or allelic deletions21,22. The inactivation of pVHL is a crucial step in the beginning of tumour formation in ccRCC23–25. According to several studies, more than 90% of patients with sporadic ccRCC had VHL gene inactivation26, whereas germline loss of VHL leads to Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHLS), a rare, but highly penetrant, autosomal dominant hereditary neoplastic disorder27. Current studies show conflicting results regarding the association of VHL mutations with overall and disease- free survival6,22,28–32.

Advances in high-throughput sequencing techniques have paved the path for the development of gene alteration databases as part of large-scale projects such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)33 and the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC)34. However, the United States and Europe have been major contributors of genetic information in such projects, making the major contributors of patient samples of Caucasian and Black ethnicities, with relatively few Asian patients being included in the studies. Merely 98 ccRCC samples from Japanese patients have been examined at the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org)35. According to the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) Data Portal (https://dcc.icgc.org), only ten Asian patient data was available and only seven Asian patients were included in TCGA database.

The lack of broad representation of the Indian population in global cancer research studies may fail to report or overlook tumour-specific mutations that are common or unique to this population. While improved clinical health awareness has resulted in the detection of more cancer patients, research into tumour genetics remains critical for the advancement of Indian medicine. Screening of the VHL gene in Indian patients has so far been limited to patients that have reported with symptoms of familial VHLS-associated pheocytochroma36–38, paraganglioma39 or congenital erythrocytosis40. In India, there is still a lack of comprehensive genetic screening of the VHL gene to assess the frequency and range of somatic VHL mutations, especially in rare cases of ccRCC. Therefore, our study aimed to identify the VHL gene mutation in Bengali patients with sporadic ccRCC and bioinformatically analyse the mutation-associated protein structural and stability changes and their effect on VHL-Elongin C interactions.

Results

Clinicopathological characterization of patient data

Table 1 represents the clinicopathological features of the patients. The median age of the patients was 54. 77 patients had newly diagnosed disease (less than six months). Histopathological analysis revealed that 210 (79.5%) patients had the clear cell subtype of RCC, 11 (4%) had the papillary subtype, 5 (1%) had the chromophobe subtype and the remaining samples showed a mixed histological structure. Early stages (T1 and T2) of the cancer made up 85% of the total sample pool. While smoking status and disease phenotype did not significantly correlate, 84% of patients were found to be moderate to severely alcoholic, raising the possibility that alcohol consumption may be related to the development of this cancer.

Table 1.

The clinical and demographic characteristics of RCC patients.

| Characteristics | No of cases |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 167 |

| Female | 94 |

| Mean age at diagnosis | |

| Male | 53.98 ± 6.212 |

| Female | 52.08 ± 6.014 |

| Localization | |

| Right | 138 |

| Left | 123 |

| Histological type | |

| Clear cell renal cell carcinoma | 210 |

| Others | 51 |

| Tumour stage | |

| T1 | 101 |

| T2 | 120 |

| T3 | 27 |

| T4 | 13 |

| Fuhrman grade | |

| 1 | 116 |

| 2 | 105 |

| 3 | 31 |

| 4 | 7 |

| Smoking status | |

| Smoking | 135 |

| Non-smoking | 126 |

| Drinking status | |

| Non-alcoholic | 41 |

| Moderately alcoholic (< 3 times/week) | 175 |

| Severely alcoholic (> 3 times/week) | 45 |

| Blood pressure | |

| Normal (90–120/60–80 mmHg) | 74 |

| Low (< 90/60 mmHg) | 29 |

| High (> 120/80 mmHg) | 158 |

| Blood sugar | |

| Normal (70–120 mg/dL) | 102 |

| High (> 120 mg/dL) | 159 |

| Urea | |

| Normal | 162 |

| High | 99 |

| Creatinine | |

| Normal | 158 |

| Low | 24 |

| High | 79 |

| Na+/K+ level | |

| Normal | 231 |

| Low | 9 |

| High | 21 |

Results of DNA sequencing

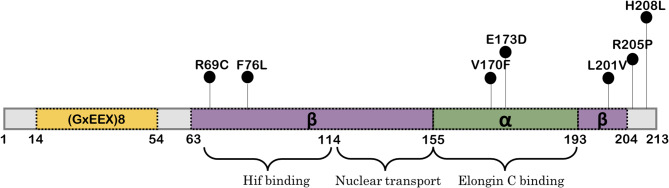

In the 210 ccRCC patients, a total of thirty-two different somatic genetic variations were observed distributed across 171 (81.4%) patient tumour tissue samples which included changes in both non-coding and coding region of the VHL gene. We found two novel missense variants (OR125592 C>T (p.Arg69Cys), OR026462 C>G (p.Phe76Leu)) in Exon 1 and five novel missense variants in Exon 3 (OR250431 G>T (p.Val170Phe), OR100596 G>T (p.Glu173Asp), OR100598 C>G (p.Leu201Val), OR250432 G>C (p.Arg205Pro), OR100599 A >T (p.His208Leu)). All of the variations were found to be heterozygous. The data supporting our findings are available at NCBI Nucleotide (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.go). An overview of the distribution of VHL novel mutations across the various binding domains of pVHL are shown in Fig. 1. The sequencing electropherogram results are provided in Fig. 2. A detailed list of genomic locations, corresponding altered amino acid data and of novel variants (according to Ensembl 110: Jul 2023) found within our sample pool is given in Table 2. There were no significant correlations between the presence of a specific mutation and patient clinicopathological parameters.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of novel missense mutations across the VHL protein.

Fig. 2.

Electropherograms showing genotypes of VHL CDS mutations in cancer tissues and adjacent normal tissues; (a) OR125592 C>T, (b) OR026462 C>G, (c) OR250431 G>T, (d) OR100596 G>T, (e) OR100598 C>G, (f) OR250432 G>C, (g) OR100599 A>T.

Table 2.

Results of in Silico prediction of functional impact of novel variants by SIFT, Polyphen-2, UMD predictor pro, SNP’s & GO and mutation taster and the effect of the CDS variations on VHL protein’s stability as determined by DUET.

| Accession No. | Chromosomal location | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Domain | SIFT score | Polyphen2 | UMD Predictor Pro | SNP’s & GO | Mutation taster | DUET | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔΔG value (Kcal/mol) | Prediction | ||||||||||

| OR125592 | 3:10142052 | c.205 C>T | R69C | BD | 0.2 | 0.715 | Pathogenic | Disease | Disease Causing | − 0.127 | Destabilizing |

| OR026462 | 3:10142075 | c.228 C>G | F76L | BD | 0.038 | 0.999 | Pathogenic | Disease | Disease Causing | − 0.298 | Destabilizing |

| OR250431 | 3:10149831 | c.508G>T | V170F | AD | 0.003 | 1 | Pathogenic | Disease | Disease Causing | − 0.983 | Destabilizing |

| OR100596 | 3:10149842 | c.519G>T | E173D | AD | 0.058 | 0.86 | Pathogenic | Disease | Disease Causing | − 0.571 | Destabilizing |

| OR100598 | 3:10149924 | c.601 C>G | L201V | AD | 0.04 | 0.929 | Pathogenic | Disease | Disease Causing | − 1.829 | Destabilizing |

| OR250432 | 3:10149937 | c.614G>C | R205P | − | 0.062 | 0.365 | Probable polymorphism | Disease | Polymorphism | − 0.435 | Destabilizing |

| OR100599 | 3:10149946 | c.623 A>T | H208L | − | 0.01 | 0.002 | Probable polymorphism | Neutral | Polymorphism | 1.055 | Stabilizing |

BD (Beta domain), AD (Alpha domain). The amino acid substitution is predicted damaging by the score of SIFT (ranges from 0 to1, damaging < = 0.05, tolerated > 0.05) and Polyphen-2 (0 being least and 1 being most).

In silico analysis for functional prediction of CDS variants

The seven novel variants were analysed using various bioinformatic tools. We used five different in silico prediction tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, UMD Predictor Pro, SNP’s & GO and Mutation Taster) to find out the pathogenic effect of the missense mutations that can cause alterations in the structure or stability of VHL protein. F76L, V170F and L201V, were consistently predicted as pathogenic by all tools, with SIFT and PolyPhen-2 scoring these mutations as damaging (≤ 0.05 and >0.9, respectively), and UMD Predictor Pro, SNPs & GO, and Mutation Taster identifying them as disease-causing. E173D was similarly predicted to be pathogenic by all tools, except SIFT, where it was predicted to be tolerated. In contrast, R205P and H208L were classified as benign polymorphisms by most tools; additionally, H208L was consistently predicted to be neutral by all tools. The results of in silico pathogenicity prediction is given in Table 2.

Novel mutations alter VHL stability

DUET analysis of the mutations revealed that the majority of them affected the stability of the VHL protein as evidenced by their score, which was less than 0. The values of the free energy change (ΔΔG) and the server’s projected signs are shown in Table 2. R69C and F76L located in the beta domain, demonstrated moderate destabilization with ΔΔG values of −0.127 kcal/mol and 0.298 kcal/mol, respectively. In the alpha domain, V170F showed a ΔΔG value of −0.983 kcal/mol, further supporting its classification as a pathogenic mutation due to its destabilizing impact. E173D also located in the alpha domain, was seen to be moderately destabilizing (ΔΔG = −0.571 kcal/mol). L201V exhibited the most destabilizing effect, with a ΔΔG value of −1.829 kcal/mol, possibly causing a severe disruption of protein stability in the alpha domain. H208L, was the only stabilizing mutation in the dataset, that showed a ΔΔG value of +1.055 kcal/mol, consistent with its classification as a benign polymorphism.

Protein homology modelling

Using the AlphaFold protein model A0A7J8HSN4.1A as a reference template, the 3D structure of the VHL protein was predicted in the SWISS-Model workspace. This template was selected due to its high sequence similarity and suitability for accurately modelling the structure of VHL. Structural comparison of the predicted VHL model with the experimental crystal structure (PDB ID: 1VCB) showed high similarity, with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.74 Å. The TM-score was 0.95807, indicating a highly conserved global topology. Structural alignment using PyMOL further confirmed near-identical structures, with minimal deviations observed in the loop regions, particularly around residues 205–213, which were absent in the crystal structure but critical for our study due to mutations in these regions. Detailed results of structural comparison and RMSD values are provided in Supplementary File S2. Each of the 15 amino acid changes in the protein’s structure was also modelled separately. Following the completion of the modelling, the quality of the protein models was assessed using the Ramachandran plot and ERRAT score from the SAVES6 server, as well as the QMEAN and MolProbity score obtained from the SWISS-MODEL structure evaluation tool. Supplementary Table 2 displays the outcomes. The wild-type and mutant projected models in this investigation all had 87% of their residues in the Ramachandran preferred region. QMEAN values show the degree of nativeness of a particular protein structure, with scores around 0.0 signifying a native-like structure and scores below −4.0 suggesting a model with low quality. All of the models in this investigation had a Z score between 0 and 1. Another evaluation score was the MolProbity score, a measure of protein quality that takes into account the crystallographic resolution at which a given quality might be anticipated. The ERRAT score was the final tool used to verify the accuracy of the protein structures. Higher scores on ERRAT are thought to indicate higher quality overall for non-bonded atomic interactions. According to41, a protein model is considered to be of excellent quality if it receives a score of at least 50. In this study, all predicted models received scores of at least 90. Supplementary Fig. 1 displays the Ramachandran plots produced by PROCHECK for each mutant structure as well as the wild-type model.

To determine whether the mutant protein structures were different from the wild-type protein structures, structural comparisons had to be made. Two distinct scores were examined for this purpose the findings of which are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The topological similarity between the two structures is scaled by the TM-score, which is the result of the sequence-independent structural comparison by TM-align. The TM-score ranges from 0 to 1. A score of 1 indicates an exact match between the wild-type and the altered structures. The TM align values ranged from 0.9 to 1, indicating slight differences in the architecture of the wild-type and mutant proteins. Furthermore, RMSD (Root-mean-square deviation) number represents the standard deviation between the corresponding atoms of two proteins. For all of the modified models, the RMSD values were quite low (less than or around 0.1), demonstrating that the mutant protein structures did not deviate significantly from the wild-type protein structures. It can be seen from Supplementary Table 2 that in the case of R205P substitution, the TM-score were less than 1 when the mutant structures were compared to the wild-type protein model, indicating structural disturbances induced by these particular mutations.

VHL-Elongin C interaction with molecular Docking

The structural comparison of the predicted VHL-Elongin C docked model with VHL-Elongin C from the crystal structure (PDB ID: 1VCB) yielded an RMSD of 0.63 Å, indicating minimal structural deviations. The TM-score was 0.97671, confirming a highly similar global topology between the two structures. Further structural alignment using PyMOL resulted in an RMSD of 0.7314 Å, with minor deviations attributed to additional residues present in the predicted model, which were absent in the crystal structure but were necessary for studying the effects of novel mutations. Detailed results of structural comparison and RMSD values are provided in Supplementary File S2. Analysis of HADDOCK results showed that the wild type VHL-Elongin C had the best binding characteristics overall with the lowest HADDOCK score (-82.6 ± 3.1), high cluster size, and good structural similarity. R69C-EloC, F76L-EloC, E173D-EloC, and L201V-EloC had binding characteristics very similar to the wild type, indicating that these mutations have minimal impact on binding affinity and structural stability. V170F-EloC showed significantly weaker binding (-61.5 ± 8.3), poor structural similarity, and lower interaction surface area, making it the least favourable interaction among the studied complexes. R205P-EloC also showed weaker binding (-75.7 ± 3.6) with higher RMSD and a positive Z score (2.2), indicating a significant decline in binding quality. Despite being a mutant, H208L-EloC showed very favourable binding characteristics, even slightly better than the wild type in terms of the Z score (-2.8). The results of docking analyses are presented in Table 3. The electrostatic energy values highlight the importance of electrostatic interactions in the VHL-EloC binding. Most mutations lead to a less negative electrostatic energy compared to the wild type (-271.4 ± 64.1 Kcal/mole), indicating that these mutations generally weaken the electrostatic component of the protein-protein interaction. The degree of change in electrostatic energy could be correlated with the overall stability and quality of the interaction. V170F-EloC showed the most significant reduction in electrostatic energy (-168.6 ± 30.1 Kcal/mole) and also the poorest overall binding characteristics (-1.7), indicating that electrostatic interactions are critical for maintaining a strong and stable complex. The high positive Van der Waals energy (37.3 ± 8.9 Kcal/mole) of the wild type complex also indicated strong attractive interactions, contributing to the stability of the complex. Mutations like R69C, F76L, and R205P, which show significantly negative Van der Waals energies, may introduce steric clashes or disrupt hydrophobic cores, leading to destabilization.

Table 3.

Docking results from HADDOCK. HADDOCK score for wild-type VHL-Elongin C complex is more negative compared to the mutated complexes.

| VHL-EloC Complexes | Cluster | HADDOCK Score | Cluster Size | RMSD (Å) |

Van der Waals energy (Kcal/mol) | Electrostatic energy (Kcal/mol) | Desolvation energy (Kcal/mol) | Restraints violation energy (Kcal/mol) | Buried Surface Area (Ų) | Z Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type-EloC | Cluster 1 | − 82.6 ± 3.1 | 30 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | − 37.3 ± 8.9 | − 271.4 ± 64.1 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 33.0 ± 29.7 | 1291.4 +/-50.3 | − 2.7 |

| R69C-EloC | Cluster 1 | − 80.3 ± 3.0 | 27 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | − 42.3 ± 6.8 | − 236.0 ± 20.9 | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 40.0 ± 23.3 | 1341.5+/- 60.8 | − 2.7 |

| F76L-EloC | Cluster 1 | − 80.3 ± 3.1 | 31 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | − 41.8 ± 6.8 | − 231.2 ± 34.0 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 29.8 ± 30.3 | 1320.9+/- 19.8 | − 2.1 |

| V170F-EloC | Cluster 1 | − 61.5 ± 8.3 | 07 | 2.7 ± 1.0 | − 26.1 ± 9.3 | − 168.6 ± 30.1 | 5.1 ± 4.4 | 33.5 ± 32.6 | 1075.2+/127.7 | − 1.7 |

| E173D-EloC | Cluster 1 | − 78.0 ± 0.9 | 32 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | − 36.3 ± 2.4 | − 264.3 ± 22.1 | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 37.7 ± 31.4 | 1349.1+/- 36.8 | − 2.6 |

| L201V-EloC | Cluster 1 | − 79.1 ± 3.1 | 35 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | − 39.5 ± 4.6 | − 241.7 ± 34.4 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 34.0 ± 28.7 | 1310.8+/- 14.2 | − 2.7 |

| R205P-EloC | Cluster 2 | − 75.7 ± 3.6 | 20 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | − 41.8 ± 4.1 | − 209.3 ± 52.2 | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 19.7 ± 29.8 | 1275.3 ± 5.2 | 2.2 |

| H208L-EloC | Cluster 2 | − 78.3 ± 4.2 | 16 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | − 40.7 ± 4.8 | − 237.8 ± 26.7 | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 40.8 ± 23.4 | 1279.8+/59.5 | − 2.8 |

Parameters obtained from docking instigates that the wild-type complex seems to be more stable compare to the mutated complexes.

Identification of the interface residues

Interface residues were identified by PPCheck. In the wild-type VHL-Elongin C complex, the common hot spot residues predicted by PPCheck were 104Leu, 105Val, 106Lys, 112Arg, 113Leu and 114Asp of VHL and 41Thr, 44Ala and 109Phe of Elongin C. In the case of the mutated complexes, for Elongin C we often found Met45, 63Arg and Asn109 of Elongin C to be included as hotspot residues. We also observed that Lys106 of VHL which was designated as a hotspot residue in the case of wild-type complex, was often not designated as hotspot residue in most of the mutated complexes. Interestingly, in the case of the V170F-Elongin C complex, we found 106Lys of VHL had been replaced by Asn109, and 41Thr and 109Phe of Elongin C were replaced by 45Met and 47Ser, as new hotspots. The detailed results obtained from the PPCheck server are provided in Supplementary File S1.

Next, the residues interactions were visualised in PDBsum. This webserver helped to differentiate between the change in interaction of interface residues in terms of hydrogen bonds, salt bridges and non-bonded hydrophobic contacts, when VHL was mutated. Results showed that while the wild-type VHL-Elongin C complex had 3 salt bridges, 10 hydrogen bonds and 63 non-bonded contacts, upon mutation these contacts were seen to change sufficiently. For instance, in the case of F76L mutation, we observed a significant increase in non-bonded contacts of interface residues (103) and in V170F we see the hydrogen bonds were reduced to 5. A summarised result of PDBsum is given in Table 4 and the extracts of residue interactions are provided in Fig. 3.

Table 4.

A summary of PDBsum result shows the salt bridges, hydrogen bonds and non-bonded contacts between wild type and mutated VHL-Elongin C complexes.

| Protein complex | Salt bridges | Hydrogen bonds | Non-bonded contacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT-EloC | 3 | 10 | 63 |

| R69C-EloC | 3 | 10 | 63 |

| F76L-EloC | 2 | 7 | 103 |

| V170F-EloC | 2 | 5 | 70 |

| E173D-EloC | 2 | 8 | 83 |

| L201V-EloC | 3 | 8 | 93 |

| R205P-EloC | 2 | 9 | 87 |

| H208L-EloC | 3 | 9 | 97 |

Fig. 3.

Summary of PDBsum and LigPlot+ analysis of wild type and mutated VHL-Elongin C complexes showing (a) total residue interactions (b) 3D structure showing interacting residues (c) nature of contacts (hydrogen, salt bridges, non-bonded contacts) between interacting residues as visualized in PDBsum (amino acid positions correspond to a N-terminally truncated version of VHL (first 65 residues removed)) (d) DIMPLOT 2D diagram from Ligplot+.

The VHL-Elongin C complexes were further visualized using the DIMPLOT module of the LigPlot+ package to determine their polar bonds and non-polar connections. In the case of wild-type VHL and Elongin C, the residues actively participating in the formation of polar bonds were Lys106, Asp114, Arg112, Cys97 and Ser47, Asn55, Arg63, Glu64, Met105, Asn108, Asp111 respectively. In the case of hydrophobic or non-polar interactions, Leu104, Val101, Val105, Leu 113 and Asn109 of VHL and Gly40, Thr41, Ala44, Met45, Asn61 and Phe109 of Elongin C were seen to be involved. Contrastingly in the case of mutated VHL-Elongin C complexes, the VHL-Tyr120 residue of R69C, V170F, L201V, R205P and the VHL-Arg111 residue of F76L, V170F, L201V, R205P and H208L were seen to form polar bonds with Arg63 of Elongin C. In the R69C-Elongin C complex, the Glu108 residue of VHL formed new polar bonds with Asn108 of Elongin C which were absent in wild-type VHL-Elongin C. Polar interaction between Cys97-Ser47 in wild type VHL-Elongin C complex was lost in case of V170F and R205P. In the F76L-Elongin C complex, we observed additional residues like Val100 and Arg111 of VHL and Gly40, Lys43 and Arg63 of Elongin C, to be actively participating in hydrophobic interactions which were absent in wild type complex. Additionally, we saw a novel salt bridge between Arg112 and Glu64 in case of F76L, V170F, E173D and R205P, and between Asp114 and Arg63 in case of H208L. Figure 3d represents the 2D diagrams of DIMPLOT representing the polar bonds and non-polar connections.

Protein flexibility-molecular dynamic (MD) simulation of VHL variants and Elongin C interaction

The flexibility of protein conformers for wild type and mutant VHL-Elongin C complexes was evaluated by CABS-flex 2. The data demonstrated the fluctuation of protein residues which are correlated with NMR ensembles. The influence of the mutations on the atomic level dynamic behaviour of the residues was determined by the RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) values from the CABS-flex 2.0 outcome. For wild-type VHL-Elongin C, the average RMSF of active residues (A97-A114) was 1.097Å for VHL. Contrastingly, in the case of the complexes having R69C, F76L, V170F, E173D, L201V, R205P and H208L VHL mutant with Elongin C, the average active site RMSF were 0.46, 0.64, 0.75, 0.67, 0.55, 0.76 and 0.96 respectively. Thus, it clearly indicated that there is an overall reduction in the fluctuation of the VHL mutated complexes with respect to the wild type complex. The overlapping fluctuation plots of the wild type and mutated complexes are given in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) plots of overlapping wild type and mutated VHL-Elongin C complexes showing structural deviations and altered flexibility in (a) R69C-Elongin C (b) F76L- Elongin C (c) V170F-Elongin C (d) E173D-Elongin C (e) L201V-Elongin C (f) R205P-Elongin C (g) H208L-Elongin C.

Discussion

The complicated interaction between genetic changes and the tumour microenvironment is an essential element of cancer biology, and tissue-specific mutations play a vital role in unravelling this complexity. Identifying tissue-specific mutations in cancer is critical for improving our understanding of the complex genetic interactome that drives cancer development and progression.

India has a diverse population with varying genetic backgrounds, ethnicities, and lifestyles. The limited representation of the Indian population in international cancer research studies42 may have resulted in the underreporting or oversight of tumour-specific mutations that are prevalent or unique to this population. While identifying more cancer cases is a positive outcome of increased clinical health awareness, understanding tissue-specific oncogenetics remains imperative for advancing medicine in India43. Therefore, our study aimed to screen ccRCC tumour tissues for novel sporadic mutations in patients with ccRCC from the Bengali ethnic population and provide a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of the pathogenic effects of these mutations and their effect on protein stability and structural changes, as well as protein-protein interactions.

In the present study, we screened a cohort of 210 individuals with sporadic ccRCC from West Bengal for the presence of VHL mutations and identified novel unreported mutations. We have also evaluated the effects of these screened mutations in silico, to understand the impact of point mutations on protein structure, stability and interactions. In our study, we found seven novel mutations from exon one and exon three of VHL, which were submitted to Banklt, NCBI. Our study aimed to investigate by in silico analysis the impact of these novel variations on the VHL-Elongin C binding interface, subsequently affecting the overall assembly and stabilisation of the VCB complex. Pathogenicity analysis revealed that the variants c.205 C>T (R69C) and c.228 C>G (F76L) are located in the beta domain of the VHL protein. The beta domain of VHL is responsible for binding HIF-α, a vital part of the oxygen-sensing pathway. Previous studies show that the VHL R69 mutants displayed significantly reduced capacity to bind HIF-1α compared to the wild-type pVHL44. Furthermore, Phe76 forms a part of the hydrophobic core of VHL protein45. Mutations in hydrophobic core residues can disrupt the VHL structural conformation46. Conversely, the variants c.508G>T (V170F), c.519G>T (E173D), and c.601C> G (L201V) are situated in the alpha domain. The alpha domain contains a BC box and an alpha-helical domain with the xLxxxCxxx[AILV] motif, serving as the binding site for Elongins, cullins, p53, Nur77, HuR, and VBP147.

In silico analysis provided valuable insights on the probable effects of the mutations on protein structure and stability. V170F (OR250431) and L201V (OR100598), located in the alpha domain (AD), exhibited the strongest destabilizing effects with ΔΔG values of −0.983 kcal/mol and −1.829 kcal/mol, respectively. Both mutations were classified as pathogenic by all predictive tools, underscoring their potential role in disease. The L201V mutation is located in the C terminal end of pVHL. The C-terminal α-helical domain of the pVHL (amino acids 195–208) has been identified as essential for its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity in regulating HIF-1α48. F76L (OR026462) located in the beta domain (BD), also showed significant destabilization (-0.298 kcal/mol) and was consistently predicted to be damaging. The PolyPhen-2 score of 0.999 suggested a substantial impact on protein functionality. Phe76 and Val170 are located in the hydrophobic core of VHL. Mutations in the hydrophobic core of VHL might disrupt critical functional regions of the protein, highlighting their importance in structural integrity and biological activity49,50. Despite being in the alpha domain and classified as pathogenic by most tools, the SIFT score (0.058) of E173D (OR100596) suggested that this mutation might be tolerated and further functional validation would be needed to confirm its true impact. Two mutations, R205P (OR250432) and H208L (OR100599), were classified as probable polymorphisms. R205P was predicted as destabilizing (ΔΔG = − 0.435 kcal/mol) but was labelled as a polymorphism by UMD Predictor Pro and Mutation Taster. This contradiction suggests that the destabilization caused by this nucleotide change might be balanced by other compensatory mechanism. H208L, on the other hand, showed a stabilizing ΔΔG value (+1.055 kcal/mol) and was classified as neutral by SNPs & GO and Mutation Taster. These results indicate it is unlikely to contribute to disease pathology. Mutations influence protein structure and function not only through localized changes but also by affecting stability and dynamics throughout the entire protein. Mutations can influence residues far from the mutated site, altering protein stability and adjusting the protein’s shape and flexibility in ways that influence its overall function51. While various studies have directly associated missense mutations in pVHL with its binding ability to HIFα, its overall tumour suppressor function is mediated by the assembling the VCB complex prior to recognition of the substrate52.

Docking of novel VHL mutants with Elongin C revealed intriguing results in which the mutants could change the binding efficiency between VHL and Elongin C. Wild-type VHL binds with Elongin C to recognise HIF-1α in hypoxic conditions effectively45. VHL mutations can cause structural changes in VHL protein in the tumour microenvironment, disturbing its orientation and initial association with Elongin C when forming the VCB complex. The Z score reflects the overall quality and reliability of the binding interaction with more negative values indicating better quality. Most mutants had Z scores close to the wild type, except for V170F and R205P, which showed significantly worse scores, indicating lower quality interactions. The electrostatic and van der Waals interactions between protein residues are both crucial for stabilizing protein-protein complexes53. Electrostatic interactions are driven by the attraction or repulsion between charged residues, with negatively charged groups attracting positively charged ones. These interactions are particularly important for aligning proteins at their binding interfaces and guiding them toward each other with specific orientation54.Alterations in electrostatic energy due to mutations may disrupt the interaction, leading to weaker and less stable complexes55. Even distal mutations can significantly impact binding affinity without disrupting the overall structure56. In the wild-type VHL-Elongin C complex, strong electrostatic attractions contribute significantly to the stability of the interaction, helping anchor the proteins together. The electrostatic energy for V170F was significantly less negative (-168.6 ± 30.1 kcal/mol) than the wild-type (-271.4 ± 64.1 kcal/mol). On the other hand, van der Waals interactions arise from the subtle attraction between nonpolar atoms, promoting close packing in the hydrophobic core of the complex57. These interactions are particularly significant in the core regions, where the packing of the molecules must be tight and efficient to minimize the system’s free energy. The VHL-Elongin C interface is almost completely hydrophobic45 and the wild type complex showed a highly favourable Van der Waals energy (−37.3 ± 8.9 kcal/mol) suggesting a strong hydrophobic packing between VHL and Elongin C. Conversely, the V170F-Elongin C complex had a significantly less negative (−26.1 ± 9.3 kcal/mol) than the wild type, indicating weaker hydrophobic interactions. The substitution of valine, a smaller, aliphatic residue with phenylalanine, a bulkier, aromatic residue most likely introduces steric clashes with nearby atoms, distorting the packing within the hydrophobic interface, leading to the loss of charge complementarity and reducing the number of optimal van der Waals contacts that can be formed. In protein–protein interactions, buried surface area (BSA) is a key parameter in understanding the extent of interaction between proteins or within protein complexes58. It represents the area of the protein surface that becomes inaccessible to solvent upon binding or folding, indicating the degree of interface burial and interaction stability. Greater BSA indicates greater binding affinity59. The wild type VHL-Elongin C complex had a BSA of 1291.4 Ų, reflecting strong packing and a well-buried interface that stabilizes the complex. Contrastingly, V170F mutation showed the lowest BSA (1075.2 Ų) among the tested variants, indicating reduced interface burial. Docking also revealed that the structure of V170F-Elongin C had a higher RMSD (2.7 ± 1.0) compared to the wild type complex (0.8 ± 0.5), suggesting more structural variability and weaker binding.

The specificity and strength of protein-protein interactions rely heavily on residue interactions at the binding interface54,60. These residues are critical for maintaining the structural integrity and functional interaction between VHL and Elongin C. Mutations can alter the interaction landscape by introducing new critical contact points while eliminating others. PDBsum analysis provided insights into the structural changes at the interface. The wild-type complex exhibited a stable configuration with 3 salt bridges, 10 hydrogen bonds, and 63 non-bonded contacts. Mutations disrupted this stability, leading to significant changes. For instance, the F76L mutation resulted in a substantial increase in non-bonded contacts to 103, highlighting a denser network of weak interactions. Molecular dynamics simulations showed that mutation at Phe76 may enlarge the HIF-1α binding pocket in pVHL, create an internal cavity, and destabilize key beta-sheets, leading to a loss of hydrogen bonds with HIF-1α61. Conversely, the V170F mutation reduced the number of hydrogen bonds to 5, suggesting a potential weakening of the interaction strength and stability. The structure of the HIF-1α-pVHL complex shows that the hydroxyproline of HIF-1α inserts into the hydrophobic core of pVHL, enabling oxygen-dependent signalling62. Previously, research has also demonstrated that mutations in the hydrophobic cores of VHL, such as F76 and V170, can alter VHL subunit conformation and disrupt the hydrophobic interactions that stabilize the VCB complex46.

Additionally, mutations were also seen to introduce new interaction dynamics. Notably, the polar bond between Cys97 and Ser47 present in the wild-type was lost in V170F and R205P mutants. Cys97 in our VHL model corresponds to Cys162 of the VHL protein. Previous studies have demonstrated that the Cys162 residue of VHL is critical for ElonginC binding, which when mutated leads to HIF accumulation63,64. Polar bonds play a critical role in stabilizing protein-protein interactions by contributing to the specificity and strength of binding interfaces. Additionally, the F76L mutation introduced new hydrophobic interactions involving Val100 and Arg111 in VHL and Gly40, Lys43, and Arg63 in Elongin C. These findings underscore how mutations can reconfigure both polar and non-polar interaction networks, potentially altering the functional interface between VHL and Elongin C. The observed alterations in hotspot residues and interaction patterns have significant implications for understanding the functional consequences of VHL mutations. These changes can influence the stability and efficacy of VHL-Elongin C binding, potentially impacting the degradation pathway of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) regulated by this complex. Flexibility of the active site residues can impact protein conformational changes, binding affinity, specificity, and catalytic activity, ultimately impacting the functional properties of the protein complex. CABS-flex simulations were able to demonstrate the change in dynamics of protein structure in the mutant VHL-Elongin C complex. The alterations found in the protein-protein interaction investigation were further reflected in the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis.

RMSF analysis indicated that the mutant VHL demonstrates somewhat less flexibility in its active site residues relative to the wild-type complex. The elevated fluctuations observed in the active site residues of the wild type may suggest greater docking flexibility and more favourable electrostatic interactions, while the reduced fluctuations in the mutants could signify a more rigid binding interface. This decreased flexibility may affect the specificity of Elongin C recognition and binding, however further experimental validation is required. The reduced RMSF values at the mutation sites of VHL indicate slight deviations from the native dynamics, perhaps leading to small structural alterations that may impact function. These structural and dynamic alterations highlight possible impacts of the novel VHL mutations on the stability and assembly of the VCB complex.

Over the years, even while the knowledge of the effects of VHL loss has grown, the majority of RCC therapies currently being utilised in clinical settings are aimed at inhibiting HIF signalling, and while they are successful, the outcomes have not been very noteworthy65,66. While mutations in the HIF-binding region of VHL have been extensively studied67–69, mutations in the VHL gene that are not located within the HIF binding region can still have a impact on the formation and function of the VCB complex32. These mutations may not just lead to HIF accumulation but also disrupt other HIF-independent VHL functions, hence contributing to cellular process dysregulation70. Our study sheds focus on novel heterozygous VHL mutations in Indian patients that are associated with sporadic ccRCC development. The concept of tumour suppressor genes (TSGs) has evolved significantly since the two-hit hypothesis. While initially thought to require complete inactivation for tumorigenesis, recent evidence suggests that even partial inactivation of TSGs can contribute critically to cancer development. This has led to the proposal of a continuum model of TSG function. The model incorporates both classical complete inactivation and partial loss of function, including the concept of “obligate haploinsufficiency” where partial loss may be more tumorigenic than complete loss71. While heterozygous mutations alone may be insufficient to cause tumorigenesis initially, with increasing age of patients, accumulation of additional risk factors coupled with less effective cellular repair mechanisms, might eventually lead to disease manifestation. Understanding the many effects of VHL mutations beyond the HIF-binding region is critical for gaining a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind VHL-related disorders and developing targeted therapeutic approaches.

In conclusion, this study identifies novel tissue-specific mutations of the VHL gene from the Indian population which are associated with sporadic ccRCC and uses in-silico tools to identify complex changes in binding energies of hotspot residues caused due to these mutations which predict to affect the interface interactions between VHL and Elongin C. These insights are crucial for advancing personalized medicine, especially in the context of India’s rich genetic diversity, and for addressing gaps in global cancer research.

There are some limitations to this study. Our study uses bioinformatics and computational modelling to predict the effects of the novel variants on pVHL-Elongin C binding. Predicted models, especially those based on homology modelling, may have limitations in representing the conformational flexibility or subtle structural variations present in the actual, experimentally determined structures. Consequently, the docking results should be interpreted with caution, as the binding poses and interactions derived from these models may differ from those obtained using experimentally validated structures. There would be a number of binding poses and interactions in both cases, but the best pose would interpret the binding affinity, binding free energy and the stability to execute its specific function. While computational approaches provide valuable structural insights, which is a significant finding in context of disease-causing mechanisms, future experimental studies directly testing the functional consequences of these variants would enhance the robustness of our findings.

Methods

Study participants

All participating patients belonged to the Bengali ethnic group, an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group residing in the province of West Bengal, in the eastern region of India. All participants in this study had given written consent and belonged from similar socio-economic background. Patients diagnosed with clear renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) between 2018 and 2023 and who were undergoing surgical treatment were included in the study. Selection was based on clinical diagnosis, with no confounding underlying conditions. Patients were excluded if they had a history of other cancers, had received prior treatment for any cancer, had incomplete clinical data, or were under the age of 35 years. Patients with family history of renal cancer were also excluded. Before taking written informed consent, each participant was carefully informed about the research utilities, outcomes, and also their orientations of association in their own language(s) and were requested to take part in this study while complying with all medical and legal requirements under strict supervision of proper medical team. The study design was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education & Research, Kolkata [Memo No. IPGME&R/IEC/2020/620] and Calcutta Medical College, Kolkata [MC/KOL/IEC/NON-SPON/1871/04/2023]. Indian Ethical compliance was followed as outlined by declaration of Helsinki (2013) and ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research).

Sample collection

Tissue samples were collected from 210 clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) patients (63 females, 147 males, and average age 55) undergoing surgical treatment, following detailed clinical questioning at the Department of Urology, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research (IPGME&R) and Calcutta Medical College and Hospital (CMC), Kolkata. None of the patients had undergone preoperative chemotherapy or immunotherapy of any kind. Roughly 1 cm3 of dissected kidney carcinoma tissue (tumour) along with a small piece of adjacent normal tissue (< 1 cm3, ‘controls’) was removed from the patients (ex vivo) during radical nephrectomy. Samples were stored in -20 °C until DNA was extracted.

Histopathological analysis

FFPE tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin for light microscopy. Macroscopic and histological parameters analysed included tumour size and nuclear Fuhrman grade, according to the WHO/ISUP grading system72 and stage according to the TNM AJCC/UICC 2009 classification73. Based on microscopic characteristics of the cancer cells, such as the size and shape of the nucleus and the prominence of the nucleoli, the Fuhrman nuclear grade was determined. Kidney tumours were categorised into one of four classes using the Fuhrman nuclear grading system.

DNA isolation

Tissue samples were homogenized using Kontes® Tissue homogenizer. Genomic DNA was isolated from all blood and tissue samples by using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Aliquots were prepared by diluting the DNA with T.E. Buffer in variable amount to achieve a final concentration of 35 ng/µl, which is optimum for PCR based sequencing. Implen NanoPhototometer® was used to measure the DNA concentration.

Genotyping

Primers were designed to amplify the entire coding sequence and exon–intron boundaries of the VHL gene in the tumour tissues (cases) and adjacent normal tissue (controls). Supplementary Table 1 contains the primer sequences. PCR amplification was undertaken in a 20 µl volume containing 35 ng of DNA, 0.5 µl of each primer (10 mmol/L), 0.2mM of deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate mix (dNTPs, 10 mmol/ L), 2mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2, 25mmol/L), 1X PCR reaction buffer and 0.5 µl of Taq Polymerase (5 units/µl). The cycling program was maintained by denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C and 60 °C 50 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min were performed for 35 cycles. A 1.5% agarose gel was used to visualize the PCR end products. All PCR products were treated with ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH, USA) and sequenced in both directions using the ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences were compared with the VHL reference (ENST00000256474.3) using the CLCBio Genomics Workbench software.

In silico analysis for functional prediction of variants

To evaluate their probable pathogenic nature, the detected novel missense variants were analysed using several bioinformatics software. To predict whether an amino acid substitution will affect protein function based on sequence homology and the physical properties of amino acids, we used SIFT (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/sift4g/) (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant)74. PolyPhen2 ( http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/)75 was used to predict the possible impact of an amino acid substitution on the structure and function of a human protein using physical and comparative considerations. We used UMD-Predictor Pro (https://umd-predictor.genomnis.com/) to further distinguish pathogenic nucleotide changes from neutral variants76. This programme offers a combinatorial method that combines the following data: location within the protein, conservation, biochemical features of the mutant and wild-type residues, and the possible influence of the variation on mRNA. The SVM classifier known as SNP’s&GO (https://snps-and-go.biocomp.unibo.it/snps-and-go/) collects unique framework information derived from protein sequence, evolutionary information and function44 as encoded in the Gene Ontology terms77. It was used for predicting whether a mutation at the protein level, is disease-related or not. Lastly, we used MutationTaster, an online bioinformatics tool that estimates the disease-causing potential of DNA sequence variations. It examines genetic mutations by combining data from many sources, such as known variant databases, evolutionary conservation data, and predictive models to predict whether a mutation is likely to cause disease or is harmless78.

Protein stability analysis

Missense mutations can alter protein stability and interaction with other biological molecules79. We investigated the changes in protein stability upon amino acid replacements and thus computed the possible effects on the folding free energy (∆∆G) using DUET80, which combines the results of two different computational approaches, mCSM and SDM.

Protein 3D modelling and structural analysis

The FASTA sequence of pVHL (P40337) was obtained from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/). Due to presence of disordered region in the first 65 amino acids of pVHL, the first 65 residues were removed for ease of docking. In the homology modelling server SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/), the 3D structures of proteins with wild-type amino acids and proteins with mutant amino acids were simulated81. The quality of structures was assessed using the SWISS-MODEL structure evaluation tool and the SAVES v6 server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/)82. Following the prediction and verification of each mutant protein model as well as the wild-type protein model, the models were examined in TM-align (https://zhanggroup.org/TM-align/)83 and visualised in PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC). The immediate interactor of pVHL in the VCB complex is Elongin C. The crystal structure of Elongin C was isolated from the 1VCB PDB model obtained from RCSB database (https://www.rcsb.org/). Prior docking, the energy of the protein models were minimised by using the YASARA energy minimisation server (http://www.yasara.org/)84. This server performs an energy minimization using the YASARA force field to eliminate undesirable elements including heteroatoms, water molecules, metal ions, ligands and additional chains. To evaluate the accuracy of our prediction, we compared the structures of our predicted VHL model and VHL model from experimentally derived PDB structure (1VCB). This comparison was carried out using multiple alignment tools, including RCSB Pairwise Alignment (https://www.rcsb.org/alignment), TM-Align, and PyMOL, to assess structural similarities and deviations.

Molecular docking

The protein models of the novel mutations were then submitted to the HADDOCK 2.4 webserver (https://wenmr.science.uu.nl/haddock2.4/). Two molecules were loaded as molecule 1 (wild type or mutated VHL) and molecule 2 (Elongin C) with their active residues (selected active residues of VHL: 97, 100, 102, 106, 113; selected active residues of Elongin C: 45, 61, 63, 64, 66) and keeping the other docking parameters same as given by HADDOCK server. Active residues were selected from the VHL-Elongin C binding region as described by64 and those selected residues of the binding region were further analysed by using CAST-p (Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of Proteins). HADDOCK uses ambiguous interaction restraints (AIRs) to encode information from known or predicted protein interfaces, which drives the docking process. It also accepts a variety of other experimental data, including NMR residual dipolar couplings, pseudo contact shifts, and cryo-EM maps, and allows for the construction of exact, unambiguous distance limits (e.g., from MS crosslinks). We compared the structures of our predicted VHL-Elongin C docked complex with the VHL-Elongin C complex from experimentally derived PDB structure (1VCB) in order to assess the precision of our prediction.

Investigation of residue interactions

The residues at the interfaces of the investigated protein–protein complexes were predicted using PPCheck85. The interaction network, which included salt-bridges, hydrogen interactions, and non-bonded contacts, was visualised using PDBsum86. The interactions of the residues were also analyzed and displayed in 2D maps by employing DIMPLOT from Ligplot+ v2.2 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LigPlus/)87. The 3D representation of the LIGPLOT diagram was visualised in PyMOL.

Protein flexibility-molecular dynamic (MD) simulation

Coarse-grained simulations of protein-protein complexes were conducted using CABS-flex v2.0 (https://biocomp.chem.uw.edu.pl/CABSflex2) to evaluate and compare the structural flexibilities of the wild type pVHL-Elongin C and mutated pVHL-Elongin C complexes88. CABS-flex provides rapid simulations of protein flexibility with significantly reduced computational demands. The flexibility simulations generated by CABS-flex have been shown to correlate strongly with results from NMR studies89. CABS-flex enables high-resolution (10-ns) simulations of near-native protein dynamics, making it a valuable tool for assessing protein–protein stability in real time. In this study, the CABS-flex simulation was conducted using the default settings, with 50 cycles.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s χ2 test was performed to ensure that allele frequencies in the sample population were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Since the frequency of the novel mutations were less than 1% and not found in adjacent control tissue, any statistical inferences regarding risk association could not be deduced.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors gratefully acknowledge the University Grants Commission for the fellowship of Srilagna Chatterjee, Anwesha Das, Kunal Sarkar and Sarbashri Bank (D.S Kothari Fellow, BL/20-21/0274). We also acknowledge The Zoological Society, Kolkata [35, Ballygunge Circular Rd, Ballygunge, Kolkata, West Bengal 700019] (Award no- ZSK/NRF/2022/3) for granting the fellowship award of Nirvika Paul. The authors are also thankful to Late Prof. Dilip Kumar Pal for providing the bio-samples and his constant assistance in the work of the manuscript. In addition, we are also thankful to the Department of Health Research, Govt. of India Scheme Multidisciplinary Research Unit, Medical College and Hospital Kolkata for their laboratory support.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.C., M.D.; Data curation: S.C, S.B.; Formal analysis: S.C, N.P., S.B.; Investigation: S.C., N.P., S.B., B.B., A.D., R.Y.; Methodology S.C., N.P., B.B., A.D., S.B., K.S.; Resources: S.S., S.M., S.C.; Software: S.C., S.B.; Supervision: M.D.; Validation: S.C., M.D.; Visualization: S.C., M.D.; Roles/Writing - original draft: S.C., S.B.; and Writing - review & editing: S.B., B.B., M.D., S.G.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under accession numbersOR125592(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR125592),OR026462 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR026462),OR250431(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR250431),OR100596(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR100596), OR100598(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR100598),OR250432(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR250432),OR100599(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR100599).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kovacs, G. et al. The Heidelberg classification of renal cell tumours. J. Pathol.183, 131–133 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choueiri, T. K. & Motzer, R. J. Systemic therapy for metastatic Renal-Cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med.376, 354–366 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsieh, J. J. et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 3, 1–19 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallah, J. & Rini, B. I. HIF inhibitors: status of current clinical development. Curr. Oncol. Rep.21, 6 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choueiri, T. K. et al. Von Hippel-Lindau gene status and response to vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Urol. (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bhagat, S., Khatri, N., Patil, S. & Barkate, H. V. Role of axitinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J. Curr. Oncol.5, 35 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonardi, E., Murgia, A. & Tosatto, S. c. E. Adding structural information to the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor interaction network. FEBS Lett.583, 3704–3710 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.William, G. & Kaelin, J. Von Hippel–Lindau disease: insights into oxygen sensing, protein degradation, and cancer. J. Clin. Investig.132, e162480 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardote, T. A., Gadd, M. S. & Ciulli, A. Crystal structure of the Cul2-Rbx1-EloBC-VHL ubiquitin ligase complex. Structure(London England:1993). 25, 901 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohh, M. et al. Ubiquitination of hypoxia-inducible factor requires direct binding to the β-domain of the von Hippel–Lindau protein. Nat. Cell. Biol.2, 423–427 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen, C., William, G. & Kaelin, J. The VHL/HIF axis in clear cell renal carcinoma. Sem. Cancer Biol.23, 18 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Struckmann, K. et al. pVHL co-ordinately regulates CXCR4/CXCL12 and MMP2/MMP9 expression in human clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Pathol.214, 464–471 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haase, V. H. The VHL tumor suppressor: master regulator of HIF. Curr. Pharm. Design. 15, 3895 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maxwell, P. H. et al. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature399, 271–275 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takagi, Y., Pause, A., Conaway, R. C. & Conaway, J. W. Identification of Elongin C sequences required for interaction with the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein**. J. Biol. Chem.272, 27444–27449 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoenfeld, A. R., Davidowitz, E. J. & Burk, R. D. Elongin BC complex prevents degradation of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.97, 8507–8512 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaakkola, P. et al. Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-Regulated Prolyl hydroxylation. Science292, 468–472 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreou, A. et al. Elongin C (ELOC/TCEB1)-associated von Hippel–Lindau disease. Hum. Mol. Genet.31, 2728 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, E. & Zschiedrich, S. Renal cell carcinoma in von Hippel–Lindau Disease—From tumor genetics to novel therapeutic strategies. Front. Pediatr.6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Young, A. C. et al. Analysis of VHL gene alterations and their relationship to clinical parameters in sporadic conventional renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.15, 7582–7592 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gossage, L. & Eisen, T. Alterations in VHL as potential biomarkers in renal-cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.7, 277–288 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banks, R. E. et al. Genetic and epigenetic analysis of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene alterations and relationship with clinical variables in sporadic renal cancer. Cancer Res.66, 2000–2011 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickerson, M. L. et al. Improved identification of von Hippel-Lindau gene alterations in clear cell renal tumors. Clin. Cancer Res.14, 4726–4734 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo, K. et al. Comprehensive mutational analysis of the VHL gene in sporadic renal cell carcinoma: relationship to clinicopathological parameters. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 34, 58–68 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu, S. L. et al. The nephrologist’s tumor: basic biology and management of renal cell carcinoma. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.27, 2227–2237 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chittiboina, P. & Lonser, R. R. Von Hippel–Lindau disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol.132, 139–156 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowey, C. L. & Rathmell, W. K. VHL gene mutations in renal cell carcinoma: role as a biomarker of disease outcome and drug efficacy. Curr. Oncol. Rep.11, 94–101 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schraml, P. et al. VHL mutations and their correlation with tumour cell proliferation, microvessel density, and patient prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Pathol.196, 186–193 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song, Y., Huang, J., Shan, L. & Zhang, H. T. Analyses of potential predictive markers and response to targeted therapy in patients with advanced Clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Chin. Med. J.128, 2026–2033 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genotype–phenotype correlation in. Von Hippel-Lindau disease - Reich – 2021 - Acta Ophthalmologica - Wiley Online Library. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Xie, H. et al. Novel genetic characterisation and phenotype correlation in von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease based on the Elongin C binding site: a large retrospective study. J. Med. Genet.57, 744–751 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linehan, W. M. & Ricketts, C. J. The cancer genome atlas of renal cell carcinoma: findings and clinical implications. Nat. Reviews Urol.16, 539–552 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tate, J. G. et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res.47, D941–D947 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, J. et al. Somatic mutations in renal cell carcinomas from Chinese patients revealed by whole exome sequencing. Cancer Cell. Int.18, 159 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dwivedi, A. et al. Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease and VHL-associated tumors in Indian subjects: VHL gene testing in a resource constraint setting. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet.23, 126 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.John, A. M. et al. p.Arg82Leu von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene mutation among three members of a family with Familial bilateral pheochromocytoma in india: molecular analysis and in Silico characterization. PLOS ONE. 8, e61908 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lomte, N. et al. Genotype phenotype correlation in Asian Indian von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome patients with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. Fam Cancer. 17, 441–449 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandrasekhar, C., Kumar, P. S. & Sarma, P. V. G. K. Novel Mutations in the EPO-R, VHL Genes and a Reported Mutation in EPAS1 Gene in the Congenital Erythrocytosis Patients in a Southern State of India (2019).

- 40.Chandrasekhar, C., Pasupuleti, S. K. & Sarma, P. V. G. K. Novel mutations in the EPO-R, VHL and EPAS1 genes in the congenital erythrocytosis patients. Blood Cells Molecules Dis.85, 102479 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Khayyat, M. Z. S. & Al-Dabbagh, A. G. A. In Silico prediction and Docking of tertiary structure of LuxI, an inducer synthase of vibrio fischeri. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biology. 4, 66 (2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao, P. et al. Landscape of cancer clinical trials in India – a comprehensive analysis of the clinical trial Registry-India. Lancet Reg. Health - Southeast. Asia. 24, 100323 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sri Guru Ram Das University Of Health Sciences & Jain, N. Cancer Scenario In India. GGS4, 1–3 (2019).

- 44.Miller, F., Kentsis, A., Osman, R. & Pan, Z. Q. Inactivation of VHL by tumorigenic mutations that disrupt dynamic coupling of the pVHL·Hypoxia-inducible transcription Factor-1α complex**. J. Biol. Chem.280, 7985–7996 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stebbins, C. E., Kaelin, W. G. & Pavletich, N. P. Structure of the VHL-ElonginC-ElonginB complex: implications for VHL tumor suppressor function. Science284, 455–461 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gossage, L. et al. An integrated computational approach can classify VHL missense mutations according to risk of clear cell renal carcinoma. Hum. Mol. Genet.23, 5976–5988 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabaro, F. et al. VHLdb: A database of von Hippel-Lindau protein interactors and mutations. Sci. Rep.6, 31128 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewis, M. D. & Roberts, B. J. Role of the C-terminal α-helical domain of the von Hippel–Lindau protein in its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Oncogene23, 2315–2323 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan, P. et al. Germline mutations in the VHL gene associated with 3 different renal lesions in a Chinese von Hippel-Lindau disease family. Cancer Biol. Ther.17, 599–603 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Hoffman, M. A. Hippel-Lindau protein mutants linked to type 2 C VHL disease preserve the ability to downregulate HIF. Hum. Mol. Genet.10, 1019–1027 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naganathan, A. N. Modulation of allosteric coupling by mutations: from protein dynamics and packing to altered native ensembles and function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.54, 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jr, W. G. K. Von Hippel–Lindau disease: insights into oxygen sensing, protein degradation, and cancer. (2022). https://www.jci.org/articles/view/162480/pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Persson, B. A., Jönsson, B. & Lund, M. Enhanced protein steering: cooperative electrostatic and Van der Waals forces in Antigen – Antibody complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 113, 10459–10464 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou, H. X. & Pang, X. Electrostatic interactions in protein structure, folding, binding, and condensation. Chem. Rev.118, 1691–1741 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karshikov, A., Bode, W., Tulinsky, A. & Stone, S. R. Electrostatic interactions in the association of proteins: an analysis of the thrombin–hirudin complex. Protein Sci.1, 727–735 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baugh, L. et al. A distal point mutation in the Streptavidin – Biotin complex preserves structure but diminishes binding affinity: experimental evidence of electronic polarization effects?? Biochemistry49, 4568–4570 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roth, C. M., Neal, B. L. & Lenhoff, A. M. Van der Waals interactions involving proteins. Biophys. J.70, 977 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kastritis, P. L. & Bonvin, A. M. J. J. On the binding affinity of macromolecular interactions: daring to ask why proteins interact. J. Royal Soc. Interface. 10, 20120835 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chakravarty, D., Guharoy, M., Robert, C. H., Chakrabarti, P. & Janin, J. Reassessing buried surface areas in protein–protein complexes. Protein Sci.22, 1453–1457 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vishwanath, S., Sukhwal, A., Sowdhamini, R. & Srinivasan, N. Specificity and stability of transient protein–protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.44, 77–86 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Limaverde-Sousa, G., De Andrade Barreto, E. & Ferreira, C. G. Cláudio Casali‐da‐Rocha, J. Simulation of the mutation F76del on the von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor protein: mechanism of the disease and implications for drug development. Proteins81, 349–363 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Min, J. H. et al. Structure of an HIF-1α-pVHL complex: hydroxyproline recognition in signaling. Science296, 1886–1889 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knauth, K., Bex, C., Jemth, P. & Buchberger, A. Renal cell carcinoma risk in type 2 von Hippel–Lindau disease correlates with defects in pVHL stability and HIF-1α interactions. Oncogene25, 370–377 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohh, M. et al. Synthetic peptides define critical contacts between Elongin C, Elongin B, and the von Hippel-Lindau protein. J. Clin. Invest.104, 1583 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mazumder, S., Higgins, P. J. & Samarakoon, R. Downstream targets of VHL/HIF-α signaling in renal clear cell carcinoma progression: mechanisms and therapeutic relevance. Cancers15, 1316 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharma, R. et al. Determinants of resistance to VEGF-TKI and immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res.40, 186 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Razafinjatovo, C. et al. Characterization of VHL missense mutations in sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: hotspots, affected binding domains, functional impact on pVHL and therapeutic relevance. BMC Cancer. 16, 638 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rechsteiner, M. P. et al. VHL gene mutations and their effects on hypoxia inducible factor HIFα: identification of potential driver and passenger mutations. Cancer Res.71, 5500–5511 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu, S. J. et al. Genotype and phenotype correlation in von Hippel–Lindau disease based on alteration of the HIF-α binding site in VHL protein. Genet. Sci.20, 1266–1273 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li, M. & Kim, W. Y. Two sides to every story: the HIF-dependent and HIF-independent functions of pVHL. J. Cell. Mol. Med.15, 187–195 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Couvé, S. et al. Genetic evidence of a precisely tuned dysregulation in the hypoxia signaling pathway during oncogenesis. Cancer Res.74, 6554–6564 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moch, H. [The WHO/ISUP grading system for renal carcinoma]. Pathologe37, 355–360 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Edge, S. B. & Compton, C. C. The American joint committee on cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann. Surg. Oncol.17, 1471–1474 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sim, N. L. et al. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res.40, W452–W457 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carter, H., Douville, C., Stenson, P. D., Cooper, D. N. & Karchin, R. Identifying Mendelian disease genes with the variant effect scoring tool. BMC Genom.14, S3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Salgado, D. et al. UMD-Predictor: A High-Throughput sequencing compliant system for pathogenicity prediction of any human cDNA substitution. Hum. Mutat.37, 439–446 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet.25, 25–29 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Steinhaus, R. et al. Mutation Taster Nucleic Acids Res.49, W446–W451 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Shoichet, B. K., Baase, W. A., Kuroki, R. & Matthews, B. W. A relationship between protein stability and protein function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.92, 452–456 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pires, D. E., Ascher, D. B. & Blundell, T. L. DUET: a server for predicting effects of mutations on protein stability using an integrated computational approach. Nucleic Acids Res.42, W314 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Waterhouse, A. et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res.46, W296 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Colovos, C. & Yeates, T. O. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Science: Publication Protein Soc.2, 1511 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang, Y. & Skolnick, J. TM-align: a protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res.33, 2302 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krieger, E. et al. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins77, 114 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sukhwal, A., Sowdhamini, R. & PPCheck A webserver for the quantitative analysis of Protein–Protein interfaces and prediction of residue hotspots. Bioinform. Biol. Insights. 9, 141 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Laskowski, R. A. PDBsum: summaries and analyses of PDB structures. Nucleic Acids Res.29, 221 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Laskowski, R. A., Swindells, M. B. & LigPlot+ Multiple Ligand–Protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model.51, 2778–2786 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuriata, A. et al. CABS-flex 2.0: a web server for fast simulations of flexibility of protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res.46, W338 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kmiecik, S. et al. Coarse-Grained protein models and their applications. Chem. Rev.116, 7898–7936 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under accession numbersOR125592(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR125592),OR026462 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR026462),OR250431(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR250431),OR100596(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR100596), OR100598(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR100598),OR250432(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR250432),OR100599(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR100599).