Abstract

Aging is associated with dysregulated methionine metabolism and increased levels of enzymes in the tyrosine degradation pathway (TDP). To investigate the efficacy of targeting either methionine metabolism or the TDP for healthspan improvement in advanced age, we initiated dietary MetR or TDP inhibition in 18-month-old C57BL/6J mice. MetR significantly improved neuromuscular function, metabolic health, lung function, and frailty. In addition, we confirmed improved neuromuscular function from dietary MetR in 5XFAD mice, whose weight was not affected by MetR. We did not observe benefits with TDP inhibition. Single-nucleus RNA and ATAC sequencing of muscle revealed cell type–specific responses to MetR, although MetR did not significantly affect mouse aging epigenetic clock markers. Similarly, an 8-week MetR intervention in a human trial (NCT04701346) showed no significant impact on epigenetic clocks. The observed benefits from late-life MetR provide translational rationale to develop MetR mimetics as an antiaging intervention.

Late-life methionine restriction extends healthspan in aged mice, revealing a promising target for antiaging therapies in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Aging is the primary risk factor for human pathologies including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases (1). Metabolic reprogramming represents a major driving force in aging and in turn impairs organismal fitness, decreases the capacity to mount a stress response, increases susceptibility to diverse diseases, and increases frailty. Targeting aging processes via reprogramming metabolism back to a more youthful state is a potentially powerful approach to delay or even reverse the aging process (2).

We and others previously demonstrated that both steady-state and methionine flux are altered during aging using Drosophila as a model system (3–6). Moreover, targeting methionine metabolism via dietary manipulations of fly food, enzymatic degradation, or manipulation of enzymes either directly involved in methionine metabolism or those that affect the levels of methionine metabolism metabolites extend health- and lifespan (4–8). In addition to results seen in Drosophila, methionine restriction (MetR) extends lifespan in yeast, rodents, and human diploid fibroblasts (6, 9–11). We have also demonstrated that the levels of enzymes in the tyrosine degradation pathway (TDP) increase with age in flies with the concomitant decrease of the levels of tyrosine and tyrosine-derived neurotransmitters, and either whole-body or neuronal-specific down-regulation of enzymes in the TDP significantly extends Drosophila health- and lifespan (12). Similar to Drosophila, downregulation of the TDP enzymes, hpd-1 and tatn-1, in worms also extended lifespan (13, 14). Although the beneficial effects of MetR under a high-fat diet and on lifespan have been demonstrated when started early or mid-age (11, 15), it is poorly understood whether MetR would improve healthspan when started late in life. Similarly, the role of the TDP in aged mice has not been previously explored.

Methionine and tyrosine metabolism pathways can both be targeted via dietary interventions, with Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs or drugs that are under development for human applications. Dietary MetR has been tested in a clinical trial in obese adults with metabolic syndrome (16–21) and several cancer clinical trials (22, 23). NTBC/nitisinone/Orfadin (2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)cyclohexane-1,3-dione) is an FDA-approved drug that inhibits 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase, an enzyme in the TDP, and is currently approved for the treatment of hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 (24). This creates a strong rationale for translating these treatments to mammalian systems as antiaging interventions or for the potential treatment of various age-related diseases.

Here, we determine whether targeting either methionine metabolism with dietary MetR or targeting the TDP with nitisinone started late in life in 18-month-old male and female C57BL/6J mice for 6 months affects various aspects of aging-related phenotypes. Dietary MetR does not affect mouse epigenetic clocks despite multiple improvements in different parameters of metabolic health, neuromuscular function, lung function, and frailty index. In contrast, we observed no such signal of benefit with nitisinone treatment. Similarly, we did not observe any effects of dietary MetR on human epigenetic clocks. Using single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) on the muscle tissues, we identified several subtype-specific processes and transcription factors (TFs) activated by dietary MetR that indicates a cell type–specific response to MetR. In addition, we confirm the beneficial effects of dietary MetR on neuromuscular function in a separate disease cohort using the Alzheimer 5XFAD mouse model. Based on these mouse studies, targeting methionine metabolism holds great promise as an antiaging intervention in humans.

RESULTS

Dietary MetR significantly decreases weight with relative increase of lean mass when started late in life

In this study, we used 18-month-old C57BL/6J mice to determine the effects of targeting methionine or tyrosine metabolism on healthspan when started late in life. To decrease circulating concentrations of methionine, we used dietary MetR. To elevate circulating tyrosine levels, we inhibited TDP with nitisinone. Previous studies on dietary exposure of mice to nitisinone ranged from 1 to 350 mg kg−1 day−1, and growth inhibition was the only treatment-related toxicity, emerging only with high doses (25). MetR provides health- and lifespan benefits only in the narrow range of the dietary concentration of methionine, as previously demonstrated both in mice (26) and flies (6). Decreasing the concentration of methionine outside this range results in the switch from MetR to methionine starvation which is detrimental to health. In most murine studies, dietary MetR is achieved by decreasing the concentration of methionine from 0.86% (control diet) to either 0.17 or 0.12% in the cysteine-free diet. We selected 0.17% as a milder regimen that is more translatable to humans.

Male and female 18-month-old C57BL/6J mice were placed on either a control diet (0.86% methionine as a proportion of protein, cysteine free) or dietary MetR (0.17% as a proportion of protein, cysteine free) and administered the vehicle control solution for nitisinone [50 mM sodium bicarbonate, 3 days/week, oral gavage (p.o.)]. Mice placed on the control diet were administered vehicle control, [3 days/week, per orally (p.o.), control group] or nitisinone (1 mg/kg, p.o., 3 days/week) for 6 months. Sham-treated, sex-matched young control mice (4 months of age) were administered the identical oral gavage regimen (vehicle control, 3 days/week; p.o.) in parallel as a control. As expected, young mice gained weight over 6 months, while dietary MetR significantly decreased the weight of aged mice—this effect being much stronger in males than in females (Fig. 1, A to F). Using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), we demonstrated that dietary MetR–induced weight loss was associated with decreased total body fat mass and percent fat mass, as well as an increased percentage of lean mass (Fig. 1, G to N). We next used indirect calorimetry chambers to evaluate preterminal whole-animal metabolism as an assessment of metabolic function, including energy expenditure (EE), respiratory exchange ratio that reflects substrate utilization, and food uptake (total and normalized to lean mass) (averaged over 24 hours, as well as broken into the light and dark cycle averages). We detected no significant differences in any of the measured parameters (Fig. 1, O to R, and fig. S1, E to T). Decreased fat mass without a corresponding reduction in food consumption could indicate a MetR-effect on lipid metabolism. Alternatively, it could reflect a reduction in EE that is either transient or below the level of easy detectability as previously published data demonstrate that low-level changes in energy balance in the range of 2.5% require approximately 350 mice to achieve adequate statistical power (27). Across all measured metrics of metabolic health, we detected no significant nitisinone effects.

Fig. 1. Dietary MetR significantly decreases weight with relative increase of lean mass when started late in life.

Male and female C57BL/6J mice fed with control (0.86% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) or MetR diet (0.17% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) or nitisinone for 6 months beginning at 18 months of age. Young (4 months) male and female C57BL/6J mice fed with control (0.86% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) diet were given an oral gavage with a mock solution and used in parallel as a control. On the graphs: Young, control young group after 6 months (10 months old); “Old,” control group of aged mice after 6 months (24 months old); “Nitisinone,” control group of aged mice after 6 months treatment with nitisinone (24 months old); “MetR,” control group of aged mice after 6 months treatment with MetR (24 months old). Means ± SD. n = 8 to 10 mice per group. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with posthoc correction for multiple hypothesis testing. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant. (A) Male and (B) female weekly [week (w)] weights after beginning of treatments. (C) Male and (D) female final weights. (E) Male and (F) female weight differences between the end and the beginning of treatment. (G) Male and (H) female % of fat mass normalized to body weight of male. (I) Male and (J) female differences in the total amount of fat between the end and the beginning of treatment. (K) Male and (L) female % of lean mass normalized to body weight. (M) Male and (N) female differences in the total amount of lean mass between the end and the beginning of treatment. (O) Male and (P) female EE (per mouse). (Q) Male and (R) female EE (per kilogram of lean mass).

In summary, nitisinone did not significantly affect any of the measured aspects of metabolic health. Dietary MetR started late in life decreased weight in aged mice to young levels with a relative increase in lean mass.

Dietary MetR improves plasma metabolic markers and returns methionine levels to youthful levels

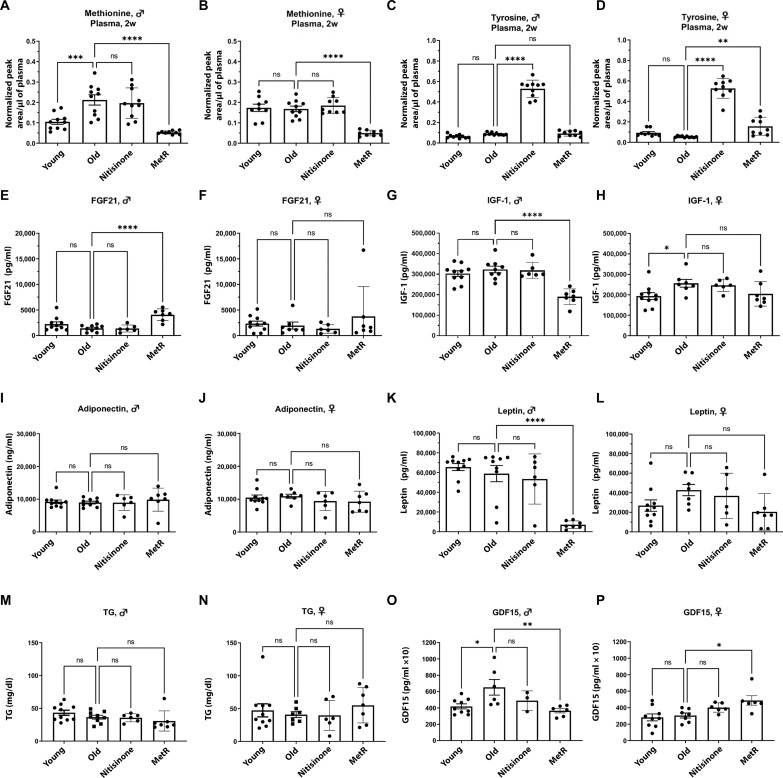

We used liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to quantify methionine and tyrosine levels (as well as other amino acids) in plasma of mice to test the effects of dietary MetR and nitisinone after 2 weeks of treatment. We found a significant aging-related elevation of circulating methionine only in male mice (Fig. 2, A and B) potentially indicative of decreased methionine flux in specific tissues, as we previously observed in Drosophila (3, 4, 28). This apparent sexual dimorphism in circulating methionine may partially explain the stronger effect of dietary MetR on age-related phenotypes in male mice. As expected, dietary MetR significantly decreased plasma methionine levels in both male and female mice to a similar extent (Fig. 2, A and B). We did not detect a significant difference in tyrosine levels between young and old mice in either sex (Fig. 2, C and D). The inhibition of the TDP significantly elevated plasma levels of tyrosine in both male and female mice to a similar extent (Fig. 2, C and D).

Fig. 2. Dietary MetR improves plasma metabolic markers and returns methionine levels to youthful levels.

LC-MS analysis of plasma samples (after 2 weeks of treatment) and analysis of plasma metabolic markers (after 6 months of treatment) from male and female C57BL/6J mice fed with either control (0.86% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) or MetR diet (0.17% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) or treated with nitisinone for 6 months beginning at 18 months of age. Young (4 month aged) male and female C57BL/6J mice fed with control (0.86% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) diet were given an oral gavage with a mock solution and used in parallel as a control. Means ± SD. n = 8 to 10 mice per group. ANOVA test with posthoc correction for multiple hypothesis testing. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Methionine levels in (A) male and (B) female plasma samples after 2 weeks (2w) of treatment. Tyrosine levels in (C) male and (D) female plasma samples after 2w of treatment. FGF21 levels in (E) male and (F) female plasma samples after 6 months of treatment. IGF-1 levels in (G) male and (H) female plasma samples after 6 months of treatment. Adiponectin levels in (I) male and (J) female plasma samples after 6 months of treatment. Leptin levels in (K) male and (L) female plasma samples after 6 months of treatment. Triglyceride levels (TG) in (M) male and (N) female plasma samples after 6 months of treatment. GDF15 levels in (O) male and (P) female plasma samples after 6 months of treatment.

We also examined additional amino acids known to be modulated by aging or by MetR in young mice (table S1 and fig. S2) including threonine, serine, tryptophan, glycine, and the branched-chain amino acids (29–33). Aside from an aging increase in threonine levels in male mice and a MetR-mediated tryptophan reduction in female mice, the levels of amino acids linked to lifespan did not show aging effects of MetR responsiveness.

Circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) are biomarkers of effective MetR in mice (11, 34–37) and humans (38), which we measured in plasma in addition to adiponectin, leptin, and triglycerides. As in young mice, aged male mice demonstrated significantly increased FGF21 levels and decreased IGF-1 and leptin without an aging effect (except in aged female mice, in which IGF-1 levels were increased). Since leptin levels reflect fat mass, the observed reduction in male mice (Fig. 1, G and I) is in line with the coincident decrease in fat mass (39). We did not detect significant effects of dietary MetR or nitisinone on plasma levels of adiponectin or triglycerides (Fig. 2, I, J, M, and N). Similarly, no metabolic measure reached significance for either intervention in female mice despite a significant decrease in body weight under dietary MetR, suggesting sexually dimorphic effects of dietary MetR at the mechanistic level beyond weight loss (Fig. 2, E to N). GDF15 has been shown to modulate metabolic health in coordination with FGF21, but whether it may mediate some of the beneficial effects of MetR is unknown (40). GDF15 levels were up-regulated with age in male mice. Unexpectedly, dietary MetR significantly decreased GDF15 levels in male mice but significantly up-regulated GDF15 levels in females (Fig. 2, O and P).

In summary, dietary MetR started late in life significantly decreased plasma levels of methionine and was associated with improved hormonal markers of metabolic health in male mice. However, the treatment of aged mice with nitisinone did not affect any hormonal markers of metabolic health despite significantly elevated plasma tyrosine levels.

Dietary MetR improves neuromuscular function in aged mice

We next aimed to test the possible effects of dietary MetR and nitisinone on coordination and basic neuromuscular function by assessing a battery of fitness metrics upon study entry and after 6 months of treatment. Rotarod testing is a well-established measure of overall motor coordination and balance, in which mice are placed on a rotating and accelerating cylinder, with time to falling as the primary readout. While control aged males demonstrated a significant decline in rotarod performance relative to young mice, dietary MetR significantly improved latencies to fall from the accelerating rotarod in old mice (Fig. 3, A and C), as seen in a prior study of MetR in young mice (34). Grip strength is a measure of peak force during grasping of a force dynamometer. While control aged males demonstrated a significant grip strength decline in forepaws (Fig. 3E and G) or all paws (Fig. 3, I and K) when compared to young mice, dietary MetR significantly improved grip strength in males only seen in the all paws measure in females (Fig. 3, J and L) but not in forepaws (Fig. 3, F and H). In an open-field assay of spontaneous exploratory activity, in which mice are free to explore a novel environment for a 60-min period, dietary MetR significantly improved the total distance traveled in both sexes relative to age-matched controls (Fig. 3, M to P) without an effect on vertical activity (rearing behavior) or time spent at the perimeter (a measure of anxiety-like behavior) (fig. S3, A to D).

Fig. 3. Dietary MetR improves neuromuscular function in aged mice.

Male and female C57BL/6J mice were fed a control diet (0.86% methionine, cysteine free), a MetR diet (0.17% methionine, cysteine free), or treated with nitisinone for 6 months starting at 18 months of age. Young male and female C57BL/6J mice (4 months old) fed the control diet and gavaged with a mock solution served as a young control group. On the graphs: Young, control group of young mice after 6 months (10 months old); Old, control group of aged mice after 6 months (24 months old); Nitisinone, control group of aged mice after 6 months of treatment with nitisinone (24 months old); MetR, control group of aged mice after 6 months of treatment with MetR (24 months old). Means ± SD. n = 8 to 10 mice per group. ANOVA test with posthoc correction for multiple hypothesis testing.*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Rotarod latency to fall: Male (A) and female (B) mice after 6 months of treatment; differences between treatment start and end (C and D). Forepaw grip strength (normalized to body weight): Male (E) and female (F) mice after 6 months of treatment; differences from baseline (G and H). All-paw grip strength (normalized to body weight): Male (I) and female (J) mice after 6 months of treatment; differences from baseline (K and L). Open field cumulative distance traveled: Male (M) and female (N) mice after 6 months of treatment; differences from baseline (O and P).

We also assessed activity levels with voluntary homecage wheel running in individual mice. Although young mice of both sexes were more active than old mice as expected, MetR transiently decreased the total time spent running in males on the first night, but all other measures were not modulated by intervention (fig. S3, E to H). Across all of the measured neuromuscular parameters, we did not detect a significant effect of nitisinone treatment. In summary, dietary MetR started late in life significantly improved metrics of neuromuscular function, while nitisinone did not have a significant effect.

Dietary MetR causes heterogeneous cell type–specific responses in the gastrocnemius muscle

To identify potential mediators of dietary MetR benefits, we performed snRNA-seq and ATAC-seq on aged control and dietary MetR gastrocnemius muscle samples. Muscle cell types [fibro-adipogenic progenitors (FAPs)] and four major myofiber types I, IIa, IIb, and IIx were annotated on the basis of the profiles of differentially expressed cell type–specific gene markers (Fig. 4A, fig. S4A, and table S2). We next looked at the changes in the cellular composition between the control aged and dietary MetR–treated muscle samples, where we can see a change in the fiber type composition (Fig. 4B), which can be further visualized when analyzing the snRNA-seq Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot split by the dietary conditions (fig. S4B). We performed Gene Ontology analysis for each cell type using significant differentially expressed genes with a log-fold threshold of 0.25 as input (Fig. 4C and table S3). In FAPs from MetR-treated muscle samples, we observe an enrichment of pathways related to skeletal muscle homeostatic processes. The FAPs from the control diet, on the other hand, are enriched for transition between fast and slow fiber. We also found enrichment for migratory pathways in MetR-treated FAPs, indicating a difference in motility between the control and dietary MetR conditions. (Fig. 4C). By contrast, type IIb myonuclei from dietary MetR–treated mice were enriched for metabolic and protein translation pathways as well as for RNA processing, consistent with induction of a heightened metabolic state. The type IIb myonuclei from the control diet exhibited enrichment in skeletal muscle processes, which stands in stark contrast to FAPs from control diet mice (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. Dietary MetR causes heterogeneous cell type–specific responses in the gastrocnemius muscle.

(A) UMAP plot of annotated clusters identified from snRNA-seq data from the gastrocnemius muscle tissues from the control aged and dietary MetR–treated muscle samples. (B) Muscle cell types distribution in the gastrocnemius muscle tissues between control aged and dietary MetR–treated muscle samples. (C) Top 5 Gene Ontology pathways differentially enriched in the gastrocnemius muscle tissues from the control aged and dietary MetR–treated muscle samples across cell types. (D to F) Up-regulated motifs in the gastrocnemius muscle tissues from the control aged and dietary MetR–treated muscle samples for type I myonuclei (D), FAPs (E), and type IIa myonuclei (F) conducted on the snATAC-seq data.

Aging is characterized by the accumulation of senescent cells in several tissues, including different muscle subtypes (41–43). To evaluate the potential effects of dietary MetR on senescence in the gastrocnemius muscle, we compared the senescence signature in our snRNA-seq dataset using the curated gene set SenMayo. We found no significant enrichment for the senescence signature in any cell type (fig. S4C).

To identify candidate TFs driving cell-specific responses, we performed motif analysis on the snATAC-seq data and identified several candidate MetR-sensitive and subtype-specific TFs in type I myonuclei, FAPs, and type IIa myonuclei (Fig. 4, D to F). Collectively, these analyses suggest differential activity of metabolic pathways and protein translation in a cell type–specific manner, although other signatures of muscle aging, including cellular senescence, were not significantly modulated at the transcriptomic level.

Dietary MetR decreases frailty in aged mice without an effect on epigenetic clocks

In light of the emerging signal of improved neuromuscular function with dietary MetR, we broadened our analyses to the composite measures of healthspan, such as frailty index and epigenetic (methylation) clocks. The frailty index is a noninvasive measure in mice that can assess the effect of treatment on different aspects of healthspan and predict life expectancy and the efficacy of lifespan–extending interventions up to a year in advance (44, 45). In this protocol, mice are individually observed and evaluated for the presence and severity of 26 different characteristics each scored as 0, 0.5, or 1 based on the level of severity and in turn, summed as a composite measure of healthspan. As expected, the frailty index was significantly higher in old male and female mice (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S5). The cumulative frailty score was significantly lower in dietary MetR, suggesting a protective effect, while nitisinone treatment did not improve frailty scores relative to aged controls (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5. Dietary MetR decreases frailty in aged mice without an effect on epigenetic clocks.

Male and female C57BL/6J mice fed with either control (0.86% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) or MetR diet (0.17% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) or treated with nitisinone for 6 months beginning at 18 months of age. Young (4 month aged) male and female C57BL/6J mice fed with control (0.86% methionine as proportion of protein, cysteine free) diet were given an oral gavage with a mock solution and used in parallel as a control. On the graphs: Young, control group of young mice after 6 months (10 months old); Old, control group of aged mice after 6 months (24 months old); Nitisinone, control group of aged mice after 6 months of treatment with nitisinone for 6 months (24 months old); MetR, control group of aged mice after 6 months of treatment with MetR for 6 months (24 months old). Means ± SD. n = 8 to 10 mice per group. ANOVA test with posthoc correction for multiple hypothesis testing; and paired t test *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Frailty index in male (A) and female (B) mice after 6 months of treatment. Body temperature in male (C) and female (D) mice after 6 months of treatment. Biological age based on different versions of epigenetic clocks from the blood samples in male (E, G, I, and K) and female (F, H, J, and L) mice after 6 months of treatment. Correlation between leptin DNA methylation and plasma levels of Leptin from human samples used to build epigenetic clocks (M). Biological age from human blood samples (STAY clinical trial) from MetR arm before and after 16 weeks of treatment (N). Disease burden in male (O) and female (P) mice after 6 months of treatment.

In one prior human clinical trial, healthy adults assigned to sulfur amino acid restriction (SAAR) exhibited a small (1%) but significant increase in body temperature (20). Similarly, in a previous study of MetR (SAAR) restriction in rats, 1 to 2% increases in core body temperature were reported in adult animals (46). In parallel to measuring frailty index, we also assessed the effects of dietary MetR and nitisinone on core body temperature before and after the treatment. Neither MetR nor nitisinone significantly affected the core body temperature (Fig. 5, C and D).

Fluctuations in DNA methylation predict biological age, and therefore the assessment of corollary epigenetic (or methylation) clocks represents a blood-based aging biomarker (47, 48). Several types of mouse epigenetic clocks have been developed differing in the subset of CpGs that go into the age estimation model, some of which are cell or tissue specific, while others are applicable across tissues. As expected, old mice had significantly higher epigenetic age in both sexes using different epigenetic clocks (Fig. 5, E to L, and table S5). Unexpectedly, we did not detect a significant effect of dietary MetR on any of epigenetic clocks tested (Fig. 5, E to L, and table S5).

Since universal mammalian clocks were trained on more than 250 mammalian species including diverse cell types and tissues (49), we sought to test whether dietary MetR may be effective in altering biological age in humans. We used the blood samples from the STAY (sulfur amino acids, energy metabolism, and obesity) clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT04701346), a double-blind 8-week dietary intervention study, where the participants were randomized in a 1:1 manner to a diet with either low or high sulfur amino acids (methionine and cysteine), and the primary and secondary outcomes were previously published in (18, 21). We first used leptin methylation status as a positive control that our epigenetic clocks work as anticipated. The level of DNA methylation for leptin (one of the epigenetic marks that were measured to build the epigenetic clocks) correlated with plasma leptin levels (Fig. 5M) previously measured in the same samples (18). As observed in mice, 8 weeks of the sulfur amino acids diet did not affect the epigenetic age (Fig. 5N).

We also performed pathological assessments of different organs and calculated the pathological disease burden score based on histopathology data from selected organs/tissues. As expected, aged mice had a significantly higher disease burden score, while dietary MetR reversed it back in females to the levels of young (10-month-old) mice (Fig. 5, O and P). In summary, dietary MetR started late in life significantly decreased the frailty index and disease burden (in female mice) without an effect on the epigenetic age in either mice or humans.

Dietary MetR improves lung function without an effect on visual acuity, short-term spatial working memory, cardiovascular function, age-related hearing loss, and benign prostatic hyperplasia

We further assessed the effects of dietary MetR and nitisinone on the function of different organs, including visual acuity (optokinetic function testing), hippocampal spatial working memory (the spontaneous alternation test), renal function (urine microalbumin and blood urea nitrogen), cardiac function (echocardiography), hearing (acoustic startle reflex), prostatic hypertrophy in males (histologic metrics), and lung remodeling (pulmonary function testing) (Fig. 6, A to P; figs. S5 and S6; and tables S5 and S6). No major changes in the airway compartment were observed; however, we did detect age-related changes in the tissue component of respiratory mechanics. Specifically, aged animals showed decreased tissue damping due to alveolar simplification when compared with their younger counterparts. Nitisinone had no significant impact on any of these measurements. By contrast, dietary MetR treatment resulted in significantly improved tissue damping in female mice and a slight change in the estimated inspiratory capacity calculated from the pressure-volume loops (Fig. 6, G and H, and fig. S5, K to N). In summary, dietary MetR improves lung function without affecting visual acuity, short-term spatial working memory, cardiovascular function, age-related hearing loss, or benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Fig. 6. Dietary MetR improves lungs function without an effect on visual acuity, short-term spatial working memory, cardiovascular function, age-related hearing loss, and benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Male and female C57BL/6J mice were fed either a control diet (0.86% methionine, cysteine-free), a MetR diet (0.17% methionine, cysteine-free), or treated with nitisinone for 6 months starting at 18 months of age. Young male and female C57BL/6J mice (4 months old) fed the control diet and gavaged with a mock solution served as a young control group. On the graphs: Young, control group of young mice after 6 months (10 months old); Old, control group of aged mice after 6 months (24 months old); Nitisinone, control group of aged mice after 6 months of treatment with nitisinone for 6 months (24 months old); MetR, control group of aged mice after 6 months of treatment with MetR for 6 months (24 months old). Means ± SD. n = 8 to 10 mice per group. ANOVA test with posthoc correction for multiple hypothesis testing. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Visual acuity in male (A) and female (B) mice after 6 months of treatment. Percent of spontaneous alteration in male (C) and female (D) mice after 6 months of treatment. Number of total entries in the spontaneous alternation test in male (E) and female (F) mice after 6 months of treatment. Tissue damping in male (G) and female (H) mice after 6 months of treatment. Urine albumine/creatinine ratio in male (I) and female (J) mice after 6 months of treatment. Left ventricular mass in male (K) and female (L) mice after 6 months of treatment. Ejection fraction in male (M) and female (N) mice after 6 months of treatment. Acoustic startle response in male (O) and female (P) mice after 6 months of treatment.

Dietary MetR improves renal and neuromuscular function without altering plasma amyloid in 5XFAD mice

Increased levels of plasma homocysteine (one of the metabolites in the methionine cycle) have been recognized as a risk factor for a number of diseases of aging including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), cardiovascular disease, and stroke (50). Moreover, methionine intake is positively associated with mild cognitive impairment and dietary MetR improves cognitive function in male amyloid-β precursor protein (APP)/PS1 mice as assessed by the Morris water maze test (51). We previously demonstrated that methionine metabolism is reprogrammed in the heads of the Drosophila model of AD (4). To test whether dietary MetR reduces amyloid plaque deposition, we applied dietary MetR for 6 months to aged male and female 5XFAD on a congenic C57BL/6J background (JAX# 034848) (52). The 5XFAD transgenic mouse overexpresses human APP with three FAD mutations [the Swedish (K670N and M671L), Florida (I716V), and London (V7171) mutations] and human PSEN1 with two FAD mutations (M146L and L286V) under the neuronal-specific Thy1 promoter (53). 5XFAD mice exhibit amyloid deposition, gliosis, and progressive neuronal loss accompanied by cognitive and motor deficiencies without forming neurofibrillary tangles, recapitulating some of the features of human AD (53). At 10 months of age, 5XFAD male mice had reduced body weights with bothMetR and control diet (Fig. 7, A and B). Dietary MetR also did not affect lean or fat mass percentages in 5XFAD mice (fig. S8, A and B). 5XFAD mice had higher levels of methionine in the plasma, in the brain, and in the gastrocnemius muscle tissues compared to wild-type (WT) (Fig. 7, C to E). After 6 months of dietary MetR, all tissues tested exhibited significantly decreased methionine levels (Fig. 7, C to E). Circulating FGF21 and IGF-1 levels, markers of MetR (11, 34–37), were significantly up- and down-regulated, respectively, by dietary MetR in 5XFAD mice (Fig. 7, F and G). IGF-1 levels were significantly lower in 5XFAD mice compared to their WT littermate controls (Fig. 7G) according to the previously characterized role of insulin signaling in the pathogenesis of AD (54). Adiponectin levels were significantly up-regulated by dietary MetR (Fig. 7H), as was previously observed in the young or mid-age mice (34, 37). Leptin levels were not affected by dietary MetR, but they were dramatically lower in 5XFAD mice compared to their WT littermate controls (Fig. 7I). Last, we did not observe differences in the levels of GDF15 between WT and 5XFAD mice or in the response to dietary MetR (Fig. 7J). As expected, plasma AB40, AB42, and the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratios were significantly up-regulated in 5XFAD mice at the baseline, before dietary intervention (Fig. 7K and fig. S8, C and D). We did not observe a significant effect after 6 months of dietary MetR on plasma amyloid and observed increased AB42 levels in insoluble brain fraction (Fig. 7, L and M, and fig. S8, E to L) despite the significant decrease of both plasma and brain methionine levels in the response to dietary MetR (Fig. 7, C and D). We also measured whether dietary MetR would elicit similar beneficial effects as we observed in the aged mice. We found that dietary MetR significantly improved grip strength in all and forepaws (Fig. 7, N and O) as we observed in aged mice. Dietary MetR also significantly improved renal function in 5XFAD mice (fig. S8, M to O).

Fig. 7. Dietary MetR improves renal and neuromuscular function without altering plasma amyloid in 5XFAD mice.

Data presented as means ± SD, n = 8 to 10 mice per group. ANOVA test with posthoc correction for multiple hypothesis testing. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. (A) Weekly weights of WT and 5XFAD mice after beginning of dietary MetR. (B) Final weights of WT and 5XFAD mice after 6 months of dietary MetR. Plasma (C), brain (D), and muscle (E) methionine levels in WT and 5XFAD mice after 6 months of dietary MetR. Plasma FGF21 (F), IGF-1 (G), adiponectin (H), leptin (I), and GDF15 (J) levels in WT and 5XFAD mice after 6 months of dietary MetR. Plasma Ab42/40 levels in WT and 5XFAD mice before beginning dietary MetR (baseline) (K) and after 6 months of dietary MetR (L). (M) Plasma Ab42/40 differences between the end and the beginning of treatment. Grip strength of forepaws (N) and all paws (O) normalized to body weight after 6 months of dietary MetR. Immunoblot analysis (P) and quantification (Q) of ACC, phosphor-ACC (Ser79), 53BP, and Tubulin in the gastrocnemius muscle tissue after 6 months of dietary MetR.

We also compared several markers in the gastrocnemius muscle tissue associated with the muscle function that may be affected by dietary MetR. Dietary MetR did not affect levels of pS6/total S6 [a marker of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation], increased the ratio of pACC/total ACC (a marker of adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase activation), had no effect on levels of H3K4me3/H3 total (a marker of active transcription), and decreased levels of 53BP1 (a marker of DNA damage) (Fig. 7, P and Q). In summary, while we did not observe a significant effect on amyloid deposition in the 5XFAD model of AD, we replicated the neuromuscular functional benefits of dietary MetR in this distinct mouse model without coincident weight loss, which argues against the MetR effect being purely secondary to weight loss.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the effects of long-term dietary MetR and nitisinone started late in life on diverse determinants of mouse healthspan. We observed that MetR mediated improvements in several parameters related to coordination, lung function, and frailty in mice of both sexes.

Direct versus indirect effects of dietary MetR and the heterogeneity of the response to MetR

We observed several beneficial effects of dietary MetR when initiated late in life: improved body weight, increase in lean mass relative to body weight, improved parameters of neuromuscular health, and improved lung function. However, it is unclear whether MetR directly affects muscle function or whether it functions via non–cell autonomous mechanisms. We demonstrated that dietary MetR significantly decreased methionine levels in the gastrocnemius muscle tissue. However, dietary MetR may affect the function of tissues via non–cell-autonomous mechanisms, such as by increased secretion of soluble mediators like FGF21 (11, 36), and we demonstrated that dietary MetR significantly up-regulated FGF21 levels. Furthermore, muscle function can be improved indirectly via a decrease of fat mass, improved vascularization, and/or an altered innervation. In addition, the response to dietary MetR may be different across different cell types in the muscle tissue. Using snRNA-seq, we found that the same process (cytoplasmic translation) was the most down-regulated process in fibro-adipogenic cells and the most up-regulated process in type IIb myofibers. On the basis of ATAC-seq analysis, we identified several TFs that were specifically affected in a cell type–specific manner in mice under dietary MetR. A future goal is to target these TFs specifically in muscle tissue to determine whether they mediate the beneficial effects of MetR on neuromuscular health. Although it is expected that dietary MetR inhibits translation as methionine plays a well-known role as an initiator of protein synthesis in prokaryotes and eukaryotes and via production of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), methionine can affect the function of different rRNA-, tRNA- and mRNA-specific methyltransferases, which are critical players in the regulation of protein synthesis. However, it remains to be determined how dietary MetR up-regulates the cytoplasmic translation in type IIb myofibers, which correlates with the increased percentage of lean mass to body weight. The percentage of lean mass may increase because of reduced fat mass. However, up-regulation of cytoplasmic translation and improved muscle function in 5XFAD mice without weight loss points toward up-regulation of the anabolic program specifically in muscle cells. To dissect the role of the methionine metabolism pathway in the specific tissues or cell types, it requires methionine depletion in a tissue-specific manner. To create a system in Drosophila for efficient tissue-specific methionine depletion without altering food composition and to study tissue-specific effects of MetR, we previously used a bacterial enzyme, methioninase, which degrades methionine to ammonia, α-ketobutyrate, and methanethiol. In Drosophila, degradation of methionine in one organ does not affect methionine levels in another organ (4). Using a similar tool in mice may enable future dissection of cell-autonomous versus non–cell-autonomous roles of methionine metabolism in different tissues.

Using nitisinone as a potential healthspan–extending compound in mice

NTBC/nitisinone/Orfadin (2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)cyclohexane-1,3-dione) is an FDA-approved drug that inhibits 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase in the TDP and is currently approved for the treatment of hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 (24). Given that our previous study, which showed an extension of lifespan in Drosophila with genetic inhibition of the TDP and specifically of CG11796, the fly ortholog of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (12), we tested the potential of NTBC/nitisinone/Orfadin to extend healthspan in mice. We did not observe any beneficial effects of nitisinone on any markers of healthspan despite increased plasma tyrosine levels in both male and female mice confirming successful inhibition of the TDP. In Drosophila, we observed a positive effect of the TDP inhibition on the lifespan when we used an RNA interference approach that causes only partial inhibition of its target and the effect was much stronger with a neuronal-specific driver. It is possible that the dose of nitisinone used in our current murine study resulted in a strong inhibitory effect on the TDP, and future experiments with the neuronal-specific manipulations of different TDP enzymes may highlight their role in the regulation of healthspan.

Dietary MetR improves frailty index but does not affect the epigenetic clock

In addition to testing the effects of interventions on age-dependent deterioration of specific organs, we aimed to determine their effects on composite markers of health such as frailty index, epigenetic clocks, and the geroscience score. Although dietary MetR significantly decreased the frailty index in both male and female mice and geroscience score in females, we did not observe significant effects on different types of epigenetic clocks. There may be several potential reasons for the apparent insensitivity of epigenetic clocks to dietary MetR: (i) Epigenetic clocks may be more sensitive to modifiers of lifespan than interventions that change healthspan. Dietary MetR started early in life only moderately extends lifespan (11). We started dietary MetR in aged mice, and lifespan was not a measured outcome. It can be expected that shorter durations of dietary MetR will result in smaller lifespan effects that would not be detected by epigenetic clocks. A previous study with a 3-month-long heterochronic parabiosis reduced the epigenetic age of blood and liver based on various clock models. This rejuvenation effect persisted even after 2 months of detachment and resulted in an increased lifespan (55). In relation to these past studies, the lack of effect with MetR may be due to a smaller impact on the rate of aging or technical differences in how epigenetic age was determined. Comparing the two interventions side by side with a standardized methodology would help resolve this question in the future. (ii) Epigenetic clocks measured from blood cells reflect the biological age of the whole organism (48, 56–58). Although we found a significant effect on several parameters of health (metabolic health, neuromuscular function, and lung function), we may not have affected a sufficiently broad swath of organs to improve a global composite score. It is possible that an epigenetic clock built from an organ, such as skeletal muscle that demonstrated improved function, would better capture the effect of dietary MetR than epigenetic clocks built from the blood samples. (iii) Methionine and adenosine triphosphate are the sole precursors for the production of SAM, the principal and rate-limiting methyl donor for methyltransferases, the enzymes responsible for setting the epigenetic clocks (59). Although the epigenetic clocks were developed to predict life/healthspan, it is unclear whether altering the levels of methionine or SAM can decouple epigenetic clocks from biological age. It is possible that dietary MetR affects SAM levels in the blood cells, which may decouple the epigenetic clock from biological age.

Dietary MetR may exacerbate amyloid deposition in 5XFAD mice

Methionine metabolism represents an ideal target for testing in the context of AD pathogenesis as (i) increased levels of plasma homocysteine have been recognized as a risk factor for a number of human diseases including dementia and AD; (ii) methionine metabolism is reprogrammed with age in different species; (iii) methionine metabolism produces SAM, which is critical for the function of all methyltransferases regulating all different aspects relevant to the AD pathogenesis; and (iv) the first and rate-limiting enzyme (MAT2A) in the methionine metabolism can be targeted with small molecules that have been tested in human cancer clinical trials. According to this, we previously demonstrated that the steady-state levels of multiple methionine metabolism intermediates (3) and methionine metabolic flux (4) are altered during aging both in whole flies and in brain tissues of Drosophila model relevant to AD. Moreover, we found that the plasma, brain, and muscle methionine levels were significantly up-regulated in 5XFAD mice. As dietary MetR may not equally affect methionine levels in different organs, we confirmed that dietary MetR efficiently decreased methionine levels in the plasma and the brains of 5XFAD mice. 5XFAD mice on the C57BL/6J background are characterized by increased AB deposition in the brain and hyperactivity, which may be a driver of their cognitive impairment in behavioral tests (52). On this basis, we tested whether 6 months of dietary MetR would alter amyloid in the brain and plasma and exhibit the same beneficial effects as we observed in aged C57BL/6J mice and that are not affected by their hyperactivity. Unexpectedly, we did not observe a significant effect of dietary MetR on amyloid deposition in plasma. Moreover, MetR increased insoluble (intracellular) amyloid deposition in the brain despite the characteristic MetR-mediated increase in production of FGF-21 and adiponectin and decreased levels of IGF-1. However, we did replicate the beneficial effect of dietary MetR on grip strength and renal function in the absence of significant weight loss. One explanation for the lack of effect of MetR on amyloid deposition is that the extent of MetR has to be tightly controlled and as previously demonstrated in mice (26), decreasing the concentration of methionine outside of the beneficial range results in the switch from MetR to methionine starvation, which is detrimental, or results in a lack of beneficial effect(s). It is possible that the extent of MetR in our study is sufficient to improve the neuromuscular, lung, and renal function but insufficient to affect overexpression of amyloid at the advanced age of 10 months when we began treatment in the 5XFAD model, which is well beyond the 2-month age when significant amyloid accumulation can first be detected in 5XFAD mice. An alternative strategy to dietary MetR is to inhibit the first and rate-limiting enzyme, methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT). Recently, several MAT2A inhibitors have been tested in human clinical trials to treat solid tumors or lymphomas (60). Future testing of MAT2A inhibitors may provide mechanistic insight into the reprogramming of methionine metabolism and AD.

Dietary MetR effects are sex specific

We observed several beneficial effects of dietary MetR that diverged in scope between male and female mice. Dietary MetR had a stronger effect on parameters of metabolic health and neuromuscular function in male mice, while dietary MetR induced GDF-15 and improved lung function in female mice. Although we do not know the exact mechanisms mediating these sex-specific differences, it is possible that lower levels of IGF-1 in female mice protect them from aging effects on metabolic health and attenuates the effect of dietary MetR. Future studies will be required to investigate the mechanisms underlying these sex-specific differences. In addition, as intermittent dietary MetR may recapitulate some of the effects of the continuous dietary MetR on metabolic health in mice under high-fat diet (61), it would be important to evaluate the temporal aspects of MetR on healthspan.

Several dietary regimens (ketogenic, diet, depletion of specific amino acids, and changing the regimen) (33, 62–65), mTORC1 inhibition (66–69), nuclear factor κB inhibition (70), increasing telomere length (71), PI3K inhibition (72), senolytics (73), hormonal interventions (74–76), epigenetic interventions (77), and others have been shown to extend healthspan in mice. As we have limited knowledge on how different interventions interact in extension of health- and lifespan (78), it would be critical to further test how dietary MetR interacts with other interventions extending healthspan.

Limitations

(i) Although we observed the beneficial effects of dietary MetR on different healthspan parameters, this study did not formally assess lifespan. (ii) We used only one inbred strain of mice, and we plan further expansion of our analysis in the future on outbred HET3 mice. (iii) Some of the phenotypes may not be evident at 24 months of age. We selected this time frame as it represents the elderly human population, and we wanted to prevent selection for the most resilient mice (due to the death of a substantial number of mice after this age from natural causes). (iv) We used only one type of clocks (epigenetic clocks) to estimate the effect of dietary MetR on biological age as they are the only clocks that can be used across different species (in our case, mice and humans) and utilization of other types of clocks in the future will be beneficial. We also do not have a positive control in parallel to demonstrate that an intervention previously shown to decrease epigenetic age when started late in life, such as heterochronic parabiosis (55), worked in our cohort of mice. (v) We used a single dose of nitisinone for this study. While we confirmed pathway engagement as indicated by elevated plasma tyrosine levels, it is possible that a different nitisinone dose might improve healthspan. (vi) We have only comprehensively assessed the effects of dietary MetR and nitisinone on different aspects of healthspan in aged mice using young mice as a reference control. Comprehensively assessing the effects of dietary MetR in young mice will help distinguish between reversing aging and aging-unrelated effects. As previously shown, some effects of rapamycin are unrelated to its effects on aging (66, 79). Moreover, some lifespan–extending interventions may have beneficial effects during one stage of life while exerting detrimental effects in another (80). Recently, it has been shown that mortality is not equally affected by lifespan–extending drugs across the lifespan in Interventions Testing Program (ITP) studies (80).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and housing conditions at the University of Pittsburgh

Adult male and female inbred C57BL/6J (JAX stock #: 000664) mice were received from The Jackson Laboratory at approximately 3 and 17 months of age. To generate cohorts of WT and 5XFAD mice, male hemizygous 5XFAD mice on a congenic C57BL/6J background (MMRRC stock #: 034848) were crossed with female C57BL6/J mice (JAX stock #: 000664). Male mice were group-housed within sex (n = 3 to 4 per cage) before starting the baseline phenotyping assessments, after which the animals were single-housed. Female mice were group-housed within sex (n = 3 to 4 per cage) through the whole experiment. The housing rooms within the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC)-certified vivarium at the University of Pittsburgh consisted of ventilated caging and an automated watering system with room temperature controlled at a setting of 22° ± 2°C and humidity at 50 ± 10%. The facility was on a 12:12 L:D schedule (lights on at 7:00 a.m.). Housing cages contained coarse certified Aspen Sani-chip bedding (PJ Murphy, Mount Jewett, PA, USA) and enrichment in the form of nestlets (Ancare Corp., Bellmore, NY, USA) and translucent domes (Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree, MA, USA). LabDiet 5P76, irradiated chow (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO, USA) was available ad libitum before switching mice onto a special control (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA, #510072) containing 0.86% of methionine or methionine-restricted diet (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA, #510071) containing 0.17% of methionine. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Pittsburgh (IACUC protocol#: IS00024514).

Human study

The study protocol outlining the design and main results from the human study has been published previously (21). Briefly, 59 men and women with overweight or obesity, but otherwise healthy, were randomized to SAAR (~2 g total SAA/day, n = 31) or a control diet (~5.6 g total SAA/day, n = 28) for 8 weeks. In the present study, we included whole-blood samples from a subset of n = 20 individuals from the SAAR group. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by Regional Ethical Committee South-East (ref. no. 123644).

Blood samples were collected into EDTA-lined 6-ml tubes and immediately frozen at –80°C until analysis. At baseline, the 24 included participants (17 females and 7 males) were on average 32.9 ± 6.12 years old and had an average BMI of 31.5 ± 2.32 kg/m2.

Body composition

Body composition (% fat mass and % lean mass) was assessed at baseline and after 6 months of the treatment using an NMR machine (EchoMRI, Echo Medical Systems). Nonanesthesized individual mice were placed in a plastic cylinder in the EchoMRI and scanned once for 2 min. Data were expressed as % of body mass or total amount of fat/lean mass.

Frailty assessment

The frailty assessment was conducted as previously described (45) to assess the spectrum of aging-related characteristics and determine whether treated mice demonstrated alterations in normal healthy aging relative to controls. Following acclimation to the testing room as described above, the participants were individually evaluated for the absence, presence, and severity of 26 characteristic traits and reflexes and scored as 0, 0.5, or 1 by a trained observer who was blind to genotype/age. The following were assessed: alopecia, loss of fur color, dermatitis/skin lesions, loss of whiskers, coat condition, piloerection, cataracts, eye discharge/swelling, microphthalmia, nasal discharge, rectal prolapse, vaginal/uterine/penile, diarrhea, vestibular disturbance, vision loss by visual placing upon the subject being lowered to a grid, menace reflex, tail stiffening, impaired gait during free walking, tremor, tumors, distended abdomen, kyphosis, body condition, breathing rate/depth, malocclusions, and righting reflex. The participants were evaluated for each measure independently, and a cumulative score of all measures was calculated with a maximum score of 26 (frailty index). Normal healthy aging is indicated by age-dependent increases in the cumulative frailty score.

Core body temperature

Core body temperature was recorded before the conclusion of the frailty assessment with a glycerol-lubricated thermistor rectal probe [Braintree Scientific product # RET 3, measuring 3/4″ (1.905 cm) L0.028 dia.0.065 tip] inserted ∼2 cm into the rectum of a manually restrained mouse for approximately 10 s. The temperature was recorded to the nearest 0.1°C (Braintree Scientific product, # TH5 Thermalert digital thermometer). Reductions in core body temperature are typical with aging and inversely correlate with frailty score, indicating morbidity. Increases in body temperature relative to controls may indicate hyperthermic responses induced by stress or inflammation.

Open field test

Versamax Open Field Arenas (40 cm by 40 cm by 40 cm; Omnitech Electronics, OH, United States) were housed in sound-attenuated chambers with lighting consistent with the housing room. Following acclimation to the testing room as described above, mice were placed individually into the center of the arena, and infrared beams recorded distance traveled (centimeter), vertical activity, and perimeter/center time. Data were collected in 5 min intervals for 60 min.

Rotarod

An accelerating rotarod (Ugo-Basile, model 47600) was used for this test. Lighting in the testing room was consistent with the housing room. Following acclimation to the testing room as described above, the mice were placed on the rotating rod (4 rpm), which accelerated up to 40 rpm over 300 s. Each mouse was subjected to three consecutive trials with an approximate 1-min intertrial interval to clean the rod between trials. Latency to fall (seconds) was measured. Subjects that fell upon initial placement on the rod before acceleration started were scored as 0 s for that trial.

Grip strength

For grip strength, the subjects were weighed and acclimated for at least 1 hour before the test. Grip strength was assessed using the Bioseb grip strength meter (model # BIO-GS3 Bioseb Inc., Vitrolles, France) equipped with a grid suited for mice (100 mm by 80 mm, angled 20°). For forepaw and all paws grip strength testing, the mice were lowered toward the grid by their tails to allow for visual placing and for the mice to grip the grid with their paws. The subjects were firmly pulled horizontally away from the grid (parallel to the floor) for six consecutive trials with a brief (<30 s) rest period on the bench between trials. Trials 1 to 3 tested only the forepaw grip, whereas trials 4 to 6 included all four paws. The average of the three forepaw trials and the average of the three four-paw trials were analyzed with normalization for body weight.

Home cage wheel running

Subjects were individually housed with a wireless running wheel (Med Associates Inc., Fairfax, VT, USA, catalog no. ENV-047) and left undisturbed for three consecutive nights except for daily welfare checks. Data were analyzed in 1-min epochs and calculated as the cumulative time spent running and the average total distance traveled over 30-min periods.

Spontaneous alternation

The spontaneous alternation test was performed as previously described (45, 52). Mice were acclimated to the testing room under ambient lighting conditions (∼50 lux). A clear polycarbonate y maze (arm dimensions: 33.65-cm length, 6-cm width, and 15-cm height) was placed on top of an infrared reflecting background (Omnitech, USA), surrounded by a black floor-to-ceiling curtain to minimize extra-maze visual cues. The mice were placed midway in the start arm (A) facing the center of the y for an 8-min test period. The sequence of entries into each arm was recorded via a ceiling-mounted infrared camera integrated with behavioral tracking software (Noldus Ethovision XT). Percent spontaneous alternation was calculated as the number of triads (entries into each of the three different arms of the maze in a sequence of three without returning to a previously visited arm) relative to the number of alteration opportunities.

Metabolic cage studies

The major determinants of energy balance were measured in the Sable Systems Promethion Multi-plexed Metabolic Cage system, including feeding, activity, EE by indirect calorimetry, and respiratory exchange ratio. The mice were individually housed during metabolic cage studies. Studies consisted of 72 hours of cage time where the first 24 hours were considered acclimation, and the subsequent 48 hours were used to calculate the 24-hour and 12-hour light and dark cycle averages and totals for each parameter measured.

Blood biochemical tests

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were used to measure leptin (MOB00B), IGF-1 (MG100), adiponectin (ADIPOQ) (MRP300) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota), and FGF21 (EZRMFGF21-26 K) (Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts). A colorimetric assay was used to determine plasma triglycerides (TR22421) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts).

Epigenetics clock analysis

The epigenetics clock analysis was performed by the Epigenetic Clock Development Foundation (Torrance, CA). DNA from the whole blood from young, old, and mice under dietary MetR was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit from QIAGEN. Nucleic acid purity was inspected with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and quantified using a Qubit fluorometer dsDNA BR Assay. DNA samples were profiled on the Illumina HorvathHumanMethylChip40 array. Different types of mouse clocks were calculated as it has been previously described (81).

Homogenization and protein extraction for Aβ analysis

Each hemibrain without cerebellum was weighed before homogenizing in tissue protein extraction reagent (T-PER, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1 ml per 100 mg of tissue weight) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Total protein concentration was measured using bicinchoninic acid (Pierce). Hemibrain lysates were then aliquoted and kept in the −80C freezer for long-term storage. Following tissue homogenization, the DEA extraction of the soluble components and the formic acid extraction of the insoluble components were performed as previously reported (82). The soluble and insoluble components were used for AB analysis and normalized to total protein.

Aβ ELISA

The plasma samples and soluble (DEA) and insoluble (formic acid) fractions from hemibrain samples were assayed in duplicate using MesoScale Discovery Aβ Peptide Panel I (4G8, K15200E, MSD) following the manufacturer’s guidelines and similar to as previously described for 5XFAD mice (52).

Amino acids analysis

Amino acids were extracted from samples according to Yuan et al. (83). Briefly, metabolites from tissue samples were extracted with 500 μl of 80% methanol (ice cold) containing heavy internal standards (Metabolomics Amino Acids Standard, MSK-A2, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). Samples were sonicated, vortexed, and incubated for 30 min at −80 C. The samples were centrifuged (14,000g, 4 C, 10 min), and the supernatants were transferred to new tubes and dried in speedvac. Samples were reconstituted in 45 μl of water before injection.

Amino acids were analyzed on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 LC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a TSQ Quantiva mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) fitted with an XBridge Amide HILIC column (3.5 μm, 100 by 4.6 mm i.d., Waters). The following LC solvents were used: solution A, 95:5 water:acetonitrile, 20 mM ammonium hydroxide, 20 mM ammonium acetate; solution B, 100% acetonitrile. The flow rate was 0.4 ml/min, and the following gradient was used: 85 to 60% B for 2 min, 60 to 50% B for 8 min, 50 to 2% B for 2 min, 2% B for 4 min, 2 to 85% B in 1 min, and re-equilibration with 85% B for 7 min (total run time of 24 min). Sample injection volume was 10 μl, the column oven temperature was set to 25°C, and the autosampler kept at 4°C. MS analyses were performed using electrospray ionization in positive ion mode, with spray voltages of 3.5 kV, ion transfer tube temperature of 325°C, and vaporizer temperature of 275°C. Multiple reaction monitoring was performed by using mass transitions between specific parent ions into corresponding fragment ions for each analyte (table S7). Skyline program was used to measure peak areas, and absolute quantitation was obtained by using heavy internal standards (84).

Measurement of urine albumin-creatinine ratio

Spot urines were obtained from mice at the time of euthanasia and stored at −80°C. Albumin levels in diluted spot urines were measured by ELISA according to the protocol provided by the discontinued mouse albumin ELISA kit from Bethyl Laboratories (Worthington, TX) and using the same primary and secondary antibodies [affinity-purified goat anti-mouse albumin antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, NC9197876) and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated detection antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, NC9617149)]. Creatinine levels were quantitated from the same spot urine samples using the Creatinine Enzymatic Reagent Set (Pointe Scientific, C7548-480, creatinine standard: C7513-STD). Albumin/creatinine ratios were calculated as albumin (milligram)/creatinine (milligram) for each sample.

Blood urea nitrogen detection

Blood urea nitrogen was determined from serum with use of an assay kit (Bioassay Systems, DIUR-100, Hayward, CA).

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis of prostate tissues

Prostate tissues were fixed in 10% formalin for at least 24 hours before paraffin embedding. Prostate sections were examined for defects by a board-certified animal pathologist in a blinded fashion as in Shappell, et al. (85). Sections were stained as previously described. Primary antibodies were rabbit monoclonal anti–Ki-67 (D3B5, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti-CD68 (KP1, CM033, BioCare Medical, Pacheco, CA, USA). Masson’s Trichrome histochemical staining was performed using HT15 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Stained sections were imaged with an Olympus BX51 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) equipped with F-View Soft Imaging System software. Mean Ki-67–positive and CD68-positive cell densities were determined by analysis of at least five nonoverlapping fields from at least five mice and from all lobes of the prostate of each mouse at 40× magnification. The extracellular matrix was quantified by determining the average intensity of blue staining in Masson’s trichrome stain using Adobe PhotoShop 2021.

Pulmonary function testing

Respiratory function testing was performed before terminal sample collection (N = 6 to 10 per group). Animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal ketamine/xylazine mixture (300 and 100 mg/kg, respectively) and underwent tracheostomy with a blunt tip 18G metal cannula. The cannula is then attached to a SCIREQ FlexiVent module 1 (SCIREQ Scientific Respiratory Equipment Inc., Montreal, Canada), and the default mouse ventilation pattern (tidal volume of 10 ml/kg, 150 breaths/min, PEEP of 3 cm H2O, and FIO2 of 21%) initiated. Once on the ventilator, intraperitoneal pancuronium bromide (13 mg/kg) was given for muscle relaxation and to ensure passive ventilation. Readouts of positive end expiratory pressure and positive inspiratory pressure were recorded in real-time. Baseline data and step-wise pressure-volume curves were obtained after approximately 5 min of equilibration without evidence of spontaneous respiratory effort.

Cross-sectional pathological assessment

The cross-sectional pathological analyses were conducted with young and old untreated and treated male and female mice. After the gross pathological examinations, the organs and tissues were excised and preserved in 10% buffered formalin. The fixed tissues were processed conventionally, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The diagnosis of each histopathological change was made with histological classifications in aging mice as previously described (86, 87). A list of pathological lesions was constructed for each mouse that included both neoplastic and nonneoplastic diseases. On the basis of these histopathological data, the tumor burden, disease burden, and severity of each lesion in each mouse were assessed as previously described (86, 87).

snRNA library preparation and sequencing

Libraries were prepared using 10X-Multiome [Gene Expression (GE) + ATAC] kit (10X Genomics) as per the manufacturer’s instruction. The libraries’ quality and quantity were assessed using the TapeStation DNA High-Sensitivity analysis and the Qubit dsDNA high-sensitivity assay. The GE libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Next Generation Sequencing Core, Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) using the SP flow cell (sequencing depth PE100) and 1% PhiX resulting in 960 M reads total. The ATAC libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform (Next Generation Sequencing Core, Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) using the P3 flow cell (sequencing depth PE100) and 1% PhiX resulting in 1.41 B reads total.

Multiome data processing

The multiome data (ATAC + RNA) (n = 4) were preprocessed using the Cell Ranger pipeline and aligned to the mm10 genome. The cellranger output was then processed using FindIntegrationAnchors. Low QC cells were filtered out.

The multiome data from different mice were pooled using Seurat and Signac for snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq, respectively. For the snRNA-seq object, sctransform normalization was applied, followed by principal components analysis (PCA), and 30 principal components were used for UMAP embedding and clustering.

snRNA-seq analysis

From the filtered barcode and count matrices, downstream analysis was performed using R (v.4.3.2). Quality control, filtering, data clustering, visualization, and differential expression analysis were performed using Seurat. Datasets were processed following Seurat standard integration protocol. Cells with less than 200 transcripts or more than 5000 transcripts and more than 60% reads mapping to mitochondrial genes were removed. PCA was performed for dimensionality reduction, and the first 50 components were used for UMAP embedding and clustering.

Skeletal muscle cell type annotation

Annotations of these clusters were finalized on the basis of the expression of marker genes for distinct skeletal muscle cell types (88). In the end, 16 clusters were retained in the snRNA-seq object. We combined and curated to yield five annotated cell-type clusters capturing the major skeletal muscle populations based on the expression of cell type–specific marker genes. The annotation of clusters was done in a semiautomated using the scSorter package from R (89). The following markers have been used: for type I myonuclei: Myh7, Myh7b, Tnnc1, and Tnnt1; for type IIa myonuclei: Myh2; for type IIx myonuclei: Myh1; for type IIb myonuclei: Myh4, Pvalb, Pfkfb3, Mical2, and Mybpc2; and for FAPs: Pdgfra and Ly6a.

Gene ontology

We used the ClusterProfiler package (90) for all Gene Ontology enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes for each cell type annotated in the snRNA-seq object. Biological processes were specified for ontology.

Gene set enrichment analysis

We used the fgsea package (91) in R for gene set enrichment analysis. Taking a dataset of differentially expressed genes between the two diet conditions in each cell type, we generated an ordered list of differentially expressed genes descending from the top spot based on average log-fold change.

The gene set we chose is SenMayo, a curated gene set for senescence markers. We then ran the function fgsea to compute enrichment score and significance of the enrichment of SenMayo features in the differentially expressed genes matrix.

snATAC-seq analysis

Four snATAC-seq samples were preprocessed using the Cell Ranger ATAC pipeline and aligned to the mm10 genome. The Cell Ranger output was processed using Signac (92). Nuclei with sequencing depth less than 1000 or more than 15,000, a nucleosome signal of more than 1, and a transcription start-site enrichment score of less than 3 were removed. Post QC, the cells were processed via a term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) followed by Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) dimension reduction (92). The first 50 components (excluding the top component) were used for UMAP embedding and clustering.

The snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq objects were integrated using FindIntegrationAnchors() followed by PCA (93). The first 30 components were used for UMAP embedding and clustering for the final integrated object.

Motifs

Before conducting the enrichment analysis, motif information was added to the pooled object using the AddMotifs function in Signac (92). Motif information for mm10 was added to the object from the JASPAR2020 database.

We calculated overrepresented motifs in a set of differentially accessible peaks. Differential accessibility (DA) analysis was carried out using the integrated snATAC-seq object using Seurat’s FindMarkers function by conducting pairwise comparisons between the experimental diet condition and the control diet condition for each tissue. The normalized ATAC counts matrix was used for DA analysis using a logistic regression framework, and differential peaks with an adjusted P value < 0.05 were kept. Taking the top differential peaks, we used the FindMotifs (which uses hypergeometric testing) function to find overrepresented motifs.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIA P30 AG024827 pilot grant (A.A.P.), NIGMS R35 GM146869 (A.A.P.), NIA R01 AG082696 (A.A.P.), NIA R00 AG057792 (A.A.P.), NIA R03 AG075651 (A.A.P.), Richard King Mellon Foundation award (A.A.P.), NAM Healthy Longevity Catalyst Award (A.A.P.), CAIRIBU Convergence Award NIDDK (L.E.P.), NIDDK K01DK115543 (K.A.F), R21DK121266 (K.A.F), R01HL135062 (J.K.A.), U54AG075931 (J.K.A.), NIH P30 AG013319 (Y.I.), R01 AG070034 (Y.I.), by the MODEL-AD consortium grant NIA U54 AG054345 (S.J.S.R.), and by Secretaría de Eduacón, Ciencia, Tecnología en Innovación de la Ciudad de México (SECTEI) (U.H.-A.). This research was also supported in part by the University of Pittsburgh Preclinical Phenotyping Core Facility for behavioral studies and by the Mass Spectrometry Core of the Salk Institute with funding from NIH-NCI CCSG: P30 014195 and the Helmsley Center for Genomic Medicine; by the Orentreich Foundation for the Advancement of Science Inc. (ASL31); by San Antonio Nathan Shock Center Pathology Core (NIH grant AG13319); by the University of Pittsburgh Small Animal Ultrasonography Core and the funding source for the instrument (NIH 1S10OD023684-01A1; S10 OD023684/OD/NIH HHS/United States); and the University of Pittsburgh Single Cell Core. This work was also supported by the NGS Core Facility of the Salk Institute with funding from NIH-NCI CCSG: P30 CA01495, NIH-NlA San Diego Nathan Shock Center P30 AG068635, the Chapman Foundation, and the Helmsley Charitable Trust (E.M.). The human study was supported by The Research Council of Norway (grant no: 310475) under the umbrella of the European Joint Programming Initiative “A Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life” (JPI HDHL) and of the ERA-NET Cofund HDHL INTIMIC (GA no. 727565 of the EU Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme) and the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Oslo. These institutions did not provide direct funding for the work in the current manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions: Writing—original draft: S.J.S.R., M.B., T.F., S.Y., Y.I., and A.A.P. Conceptualization: O.E., S.J.S.R., L.E.P., R.J.T., T.O., B.Mc.M., T.F.G., T.F., M.J.J., Y.I., A.A.P., M.L.S., and F.A. Investigation: R.T.B., A.F.M.P., U.H.-A., O.E., L.E.P., J.K.D., R.J.T., W.N.A., K.A.F., T.O., M.B., B.Mc.M., H.L.H., T.F.G., C.S., S.Y., I.J.S., G.J.L., G.P.A., M.J.J., Y.I., E.M., L.C.F., A.A.P., A.M.V., B.C., D.C., J.K.A., E.S., H.T., A.G., F.A., K.J.V., S.-P.G.W., and A.S. Writing—review and editing: A.E., R.T.B., U.H.-A., O.E., S.J.S.R., L.E.P., R.J.T., W.N.A., K.A.F., T.O., M.B., H.L.H., T.F., G.J.L., G.P.A., M.J.J., Y.I., O.A.W., E.M., A.A.P., C.N., H.T., F.A., K.J.V., M.L.S., J.K.A., B.O., and A.S. Methodology: O.E., S.J.S.R., L.E.P., R.J.T., W.N.A., K.A.F., T.O., M.B., B.Mc.M., M.J.J., Y.I., O.A.W., A.A.P., C.N., A.G., F.A., B.O., and K.J.V. Resources: R.T.B., O.E., S.J.S.R., R.J.T., K.A.F., T.O., M.B., B.Mc.M., H.L.H., T.F.G., G.J.L., G.P.A., M.U.N., M.J.J., Y.I., E.M., A.A.P., E.S., F.A., J.K.A., D.C., and K.J.V. Funding acquisition: O.E., K.A.F., T.O., and A.A.P. Data curation: R.T.B., T.O., M.B., B.Mc.M., T.F.G., I.J.S., G.P.A., M.U.N., Y.I., O.A.W., A.A.P., and A.G. Validation: U.H.-A., S.J.S.R., L.E.P., W.N.A., K.A.F., M.B., B.Mc.M., H.L.H., S.Y., I.J.S., G.J.L., G.P.A., M.U.N., Y.I., A.A.P., A.G., F.A., S.-P.G.W., and K.J.V. Formal analysis: R.T.B., U.H.-A., O.E., S.J.S.R., L.E.P., R.J.T., W.N.A., K.A.F., T.O., M.B., H.L.H., T.F.G., S.Y., G.J.L., G.P.A., M.J.J., Y.I., O.A.W., L.C.F., A.A.P., C.N., A.G., F.A., S.-P.G.W., and A.S. Software: M.U.N. and C.N. Visualization: U.H.-A., O.E., L.E.P., W.N.A., T.O., M.B., B.Mc.M., T.F.G., Ce.S., S.Y., G.J.L., M.U.N., Y.I., A.A.P., A.G., A.S. Supervision: O.E., S.J.S.R., R.J.T., T.O., T.F., M.J.J., O.A.W., A.A.P., C.N., and A.S. Project administration: T.O., M.J.J., A.A.P., and F.A.

Competing interests: S.J.S.R. is adjunct faculty at the Jackson Laboratory. She is a paid consultant for Hager Bioscences and GenPrex Inc. and holds stock for Merck, Organon, Pfizer, and Momentum Bioscences. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The availability of human data is regulated by the University of Oslo where the study was conducted in accordance with local and European privacy laws (General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR). At the time of publication, GDPR limits sharing of raw data points from the human study. However, access will be granted as long as a data transfer agreement is established to ensure compliance with the GDPR and approval by relevant ethical committees are in place. Requests for data access can be directed to Head of Section of Clinical Nutrition at the Department of Nutrition, University of Oslo, C. Henriksen at christine.henriksen@medisin.uio.no. She will assist with notification of the Regional Ethical Committee South-East and the Norwegian Agency of Shared Services in Education and Research, and coordinate institutional data transfer agreements.

Supplementary Materials

The PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S8

Legends for tables S1 to S7

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Tables S1 to S7

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Lopez-Otin C., Blasco M. A., Partridge L., Serrano M., Kroemer G., Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 186, 243–278 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkhitko A. A., Filine E., Mohr S. E., Moskalev A., Perrimon N., Targeting metabolic pathways for extension of lifespan and healthspan across multiple species. Ageing Res. Rev. 64, 101188 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkhitko A. A., Binari R., Zhang N., Asara J. M., Demontis F., Perrimon N., Tissue-specific down-regulation of S-adenosyl-homocysteine via suppression of dAhcyL1/dAhcyL2 extends health span and life span in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 30, 1409–1422 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]