Abstract

Proteins of plant cell walls serve as structural macromolecules and play important roles in morphogenesis and development but have not been reported to be the origins of peptide signals that activate genes for plant defense. We report here that the mRNA coding the tomato leaf polyprotein precursor of three hydroxyproline-rich glycopeptide defense signals (called LeHypSys I, II, and III) is synthesized in phloem parenchyma cells in response to wounding, systemin, and methyl jasmonate, and the nascent protein is sequestered in the cell wall matrix. These findings indicate that the plant cell wall can play an active role in defense as a source of peptide signals for systemic wound signaling.

Keywords: phloem parenchyma, tomato leaves, wound signals, plant defense

Peptide hormone signaling in plants is a growing area of research in which nearly 20 peptide signals (hormones) have been identified to date that regulate genes for cell division, development, reproduction, nodulation, and defense (1-8). Plant peptide signals have several characteristics that are found in animals and yeast peptide hormones (1) that include being derived from larger precursor proteins, being receptor mediated, and being active at low nanomolar concentrations. Three novel hydroxyproline-rich glycopeptide signals (LeHypSys I, II, and III) were recently isolated from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) leaves that are powerful activators of the same intracellular defense-related genes that are activated by wounding and systemin, mediated by the octadecanoid pathway (7). The three peptides are composed of 18, 20, and 15 amino acids, respectively, and are derived from a single polyprotein precursor (7), here called LepreproHypSys. Whereas the tomato prosystemin precursor is synthesized and compartmentalized in the cytosol and nucleus of phloem parenchyma cells (9), the cell types and subcellular localization of the precursor of the HypSys peptides has not been known. Here, we report that the LeproHypSys precursor protein is synthesized in the phloem parenchyma cells of the vascular bundles of tomato leaves and is localized in the cell wall matrix. The results reveal a role for the cell wall matrix in harboring the precursor of peptides that are known to be powerful signals for the activation of defense genes of tomato leaves.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Treatments. Wild-type tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. Castlemart) and transgenic tomato plants were grown in growth chambers under 18 h of light (300 μmol photons m-2 s-1) at 28°C and 6-h nights at 18°C. To assay wound inducibility, terminal leaflets of the lower leaves of 2-week-old plants were wounded twice across the mid-vein with a hemostat. Plants were then incubated for 24 h under continuous light at 28°C, and undamaged tissue from wounded and unwounded leaves was collected and processed for LeproHypSys mRNA and protein localization analyses. Two-week-old plants were also treated with methyl jasmonate vapors as described in ref. 10.

DNA Blot Analyses. Tissues from wild-type and transgenic tomato plants were immersed in liquid nitrogen, ground to a fine powder, and stored at -80°C until used. Genomic DNA was extracted from ≈5 g of fresh weight leaf tissue by using DNAzol (Invitrogen) and following the manufacturer's protocol. Five micrograms of genomic DNA was separately digested with restriction enzymes, fractionated on agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes, and probed with a random-primed 32P-labeled LepreproHypSys cDNA, and the hybridized membranes were washed as described in ref. 10.

In Situ Hybridization. In situ hybridization analyses to visualize LepreproHypSys mRNA were carried out by using 10-μm paraffin sections of leaf and petioles of tomato plants with methods described in ref. 9. Sections were hybridized with in vitro transcribed digoxigenin-labeled LepreproHypSys sense or antisense RNA probes, synthesized from linearized pBluescript plasmids containing a full-length LepreproHypSys cDNA (7). Hybridized probes were colorimetrically detected with antidigoxigenin antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis). Sections were mounted in DPX embedding medium (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA), examined, and photographed with an Olympus BH2 light microscope.

Expression of a LepreproHypSys-GFP Fusion Gene. A LepreproHyp-Sys-GFP fused gene was prepared first by amplifying the LepreproHypSys gene by PCR from the full-length cDNA clone (7) with both a sense primer (5′-CGGAATTCATGATCAGCTTCTTCAGAGCTTTCT-3′) and an antisense primer (5′-CGGGATCCATAGGAAGCTTGAAGAGGCAAAGTA-3′). The amplified PCR product contained the LepreproHypSys ORF without a stop codon and with an introduced EcoRI and BamHI recognition sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and was ligated to the N terminus of GFP within the pEZR-LN vector (11). The LepreproHypSys-GFP chimeric gene constructs was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and stably transformed into tomato plants (cv. Microtome) as described in ref. 12. At least 15 independent primary transformants were regenerated and assayed for the expression of the different gene constructs by Northern blotting and confocal laser scanning microscopy. As a negative control for the localization of the LeproHypSys-GFP fusion protein, tomato plants were also independently transformed with the pEZR-LN vector alone. The GFP protein was visualized with a Bio-Rad MRC-1024 confocal laser scanning microscope by using blue laser excitation light (488 nm). Optical sections were digitally processed by using photoshop 8.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Preparation of LeproHypSys Peptide Antibodies. Rabbit antibodies were prepared against synthetic peptide sequences of N- and C-terminal regions of the LepreproHypSys protein that were distal from putative glycosylation sites and did not include amino acids from the bioactive peptide sequences (7). The N-terminal peptide consisted of 17 amino acids (from Asn-30 to Asn-46), and the C-terminal peptide included 14 amino acids (from Gln-90 to Thr-103). Synthetic peptides were conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) by using the Imject mcKLH kit (Pierce) and following the manufacturer's recommendations. LeproHypSys-KLH conjugated peptides were injected into rabbits (Pocono Rabbit Farm and Laboratory, Canadensis, PA), and the presence of cross-reacting antibodies in rabbit serum were monitored by ELISA and protein immunoblot analyses. For immunocytochemistry, primary antibodies were affinity purified by using protein-G coated magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech, Oslo), as described in ref. 9.

Protein Immunoblots. Leaves from 2-week-old tomato plants were frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground to a fine powder with a mortar and pestle, extracted with an equal volume of 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) in a 1.7-ml Eppendorf tube, and incubated on ice for at least 1 h. Cell debris was pelleted at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and stored at -20°C until use. Proteins in the supernatant were quantified with the BCA kit (Pierce) with BSA as a protein standard. Fifty micrograms of total soluble proteins were mixed with an equal volume of 2× Laemmli's sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and loaded into 12% polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis in duplicate gels, proteins in one gel were stained with Coomassie blue, and the others were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, probed with LeproHypSys peptide antibodies, and exposed to anti-IgG secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase, followed by colorimetric development.

Immunocytochemical Staining. Immunocytochemistry was performed as described in ref. 9. Briefly, leaf samples were fixed overnight at 4°C in 50 mM Pipes buffer (pH 7.2), containing 2% (vol/vol) formaldehyde and 0.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, dehydrated, and embedded in L.R. White resin (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA). Leaf cross-sections (0.1 μm) were incubated 2 h at 25°C in blocking solution [100 mM Tris, pH 7.2/500 mM NaCl/0.3% (vol/vol) Tween-20/0.5% (wt/vol) PVP (Mr 10,000)/0.5% (vol/vol) donkey serum/1% (wt/vol) BSA/0.02% (wt/vol) NaN3], followed by 3-18 h in blocking solution containing protein-G affinity purified anti-LeproHypSys peptide antibodies (1:50-1:200 dilution). A similar dilution of the corresponding preimmune serum IgGs was always used as a negative control. Thereafter, sections were washed four times with blocking solution alone, incubated 2 h with blocking solution containing 18-nm gold-labeled donkey anti-rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:20 dilution, Jackson ImmunoResearch), and washed four times with blocking solution and three times with distilled water. Sections were poststained 5 min with a 1:3 mixture of 1% (vol/vol) potassium permanganate and 2% (vol/vol) uranyl acetate in water and examined with a transmission electron microscope, Model JEM 1200 EX (JEOL) at 100 kV.

Results and Discussion

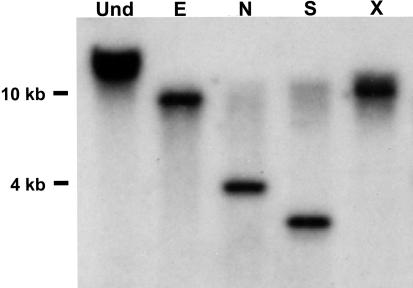

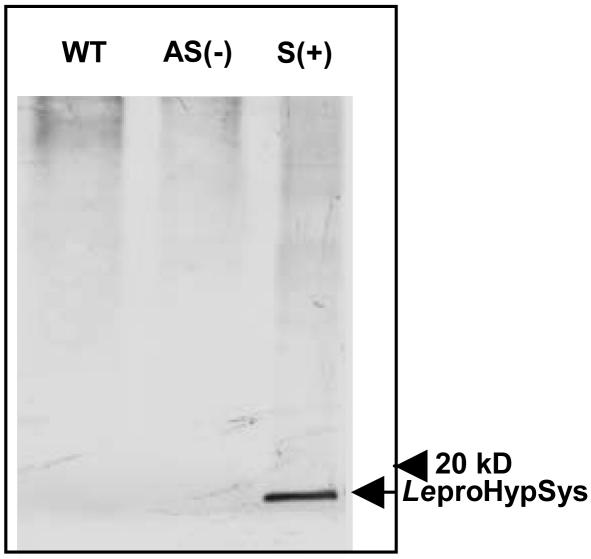

The protein precursor of HypSys I, II, and III peptide defense signals, LepreproHypSys, is composed of 146 amino acids with a leader sequence that directs its synthesis through the secretory pathway (7), where the protein is postranslationally decorated with hydroxyl groups and pentose residues. LepreproHypSys, like prosystemin (12), is encoded by a single copy gene (Fig. 1) that is up-regulated in tomato leaves by wounding, systemin, and methyl jasmonate treatments (7). When each of the three peptides were supplied to young, excised tomato plants through their cut petioles, they activated the synthesis and accumulation of proteinase inhibitor protein in leaves (7), demonstrating that the peptides were behaving as signals for defense. The LeproHypSys precursor protein was shown to accumulate in the leaves of plants constitutively overexpressing the prosystemin gene (13) (Fig. 2), indicating that the peptide precursor gene is regulated by systemin. The rabbit antibodies used to identify the protein was prepared against synthetic peptide sequences of the N- and C-terminal regions of LeproHypSys protein that were distal from putative glycosylation sites and did not include any sequences from the regions containing the bioactive peptides. The protein did not accumulate in leaves of plants overexpressing the prosystemin gene in its antisense orientation (Fig. 2), and the LeproHypSys mRNA accumulation was suppressed in wounded leaves of antisense transgenic plants (data not shown). In wild-type plants, the LeproHypSys mRNA has been shown to be systemically induced to accumulate in response to wounding (7). The experiments demonstrated that the gene is among the wound/systemin responsive genes in tomato plants, suggesting that the role of HypSys peptides, like systemin, may be to amplify the wound response in tissues throughout the plants (13).

Fig. 1.

DNA blot analysis of the LeproHypSys precursor gene. Five micrograms of genomic DNA isolated from tomato leaves was digested with the restriction enzymes EcoRI (E), NdeI (N), SpeI (S), and XhoI (X). Digested and undigested (Und) DNA were separated on an agarose gel, transferred to nylon membranes, and probed with the LeHypSys precursor cDNA. Nucleic acid lengths (kb) are indicated on the left.

Fig. 2.

Protein immunoblot analysis of LeproHypSys in leaves of wild-type (WT) tomato plants and in plants overexpressing the prosystemin gene in its sense [S(+)] and antisense [AS(-)] orientations. Fifty micrograms of total soluble proteins extracted from leaves in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) were mixed with equal volume of Laemmli's sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and loaded into 12% polyacrylamide gels (SDS/PAGE). After electrophoresis, proteins were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with LeproHypSys peptide antibodies, followed by exposure to anti-IgG secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase and color development. The arrow on the right indicates a cross-reacting band (≈16 kDa) corresponding to the LeproHypSys precursor protein.

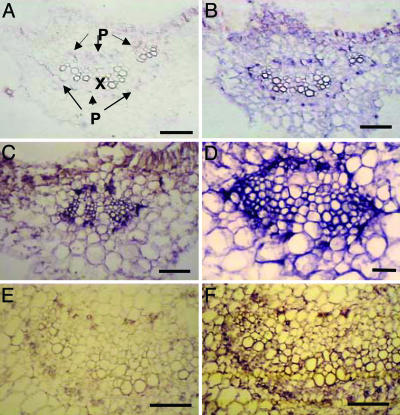

To identify the specific cell types in which the LepreproHypSys gene is expressed, leaves and petioles of young tomato plants were analyzed by using in situ hybridization techniques. LepreproHypSys mRNA was found to be synthesized exclusively within the vascular bundles of mid-veins of leaves and petioles, associated with parenchyma cells of phloem bundles (Fig. 3). Phloem parenchyma cells have been shown to be the sites of synthesis of the prosystemin precursor mRNA (9), where the release of the peptides in cells near the companion cells of the phloem facilitate the amplification of systemic signaling (9, 14, 15).

Fig. 3.

Localization of LepreproHypSys precursor mRNA in tissue sections from leaves and petioles of tomato by in situ hybridization. Sections were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled LepreproHypSys sense or antisense RNA probes. Hybridized probes were detected with digoxigenin antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase, as described in ref. 9. (A) Cross-section through the mid-vein of a leaf from a control untreated plant hybridized with the sense probe (negative control). (B) Similar section as in A, hybridized with the antisense probe, showing very low constitutive levels of LepreproHypSys mRNA accumulation. (C) Section from a wounded leaf, hybridized with the antisense RNA probe (6 h after wounding). (D) Methyl jasmonate-induced LepreproHypSys mRNA accumulation in phloem bundles of a mid-vein, 6 h after treatment. (E) Cross-section of a petiole from a wounded leaf hybridized with the sense probe. (F) Wound-induced accumulation of LepreproHypSys mRNA in phloem bundles of a petiole. P, phloem bundles; X, xylem. (Scale bars: 50 μm.) Arrows show concentrations of label.

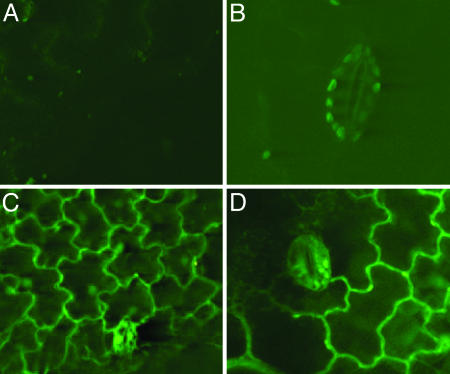

The specific localization of newly synthesized LeproHypSys protein was visualized in leaves of tomato plants transformed with a constitutively expressed LepreproHypSys-GFP fusion gene. The visual detection of the gene, monitored by using confocal microscopy, was found to be associated primarily with cell walls (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Visualization of a LeproHypSys-GFP fusion protein in leaves of transgenic tomato plants visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy. (A and B) Leaf epidermal cells of a control plant transformed with the GFP gene construct alone. (C and D) Confocal image showing GFP fluorescence localized to the cell walls of epidermal cells of transgenic plants expressing the LeproHypSys-GFP fusion protein.

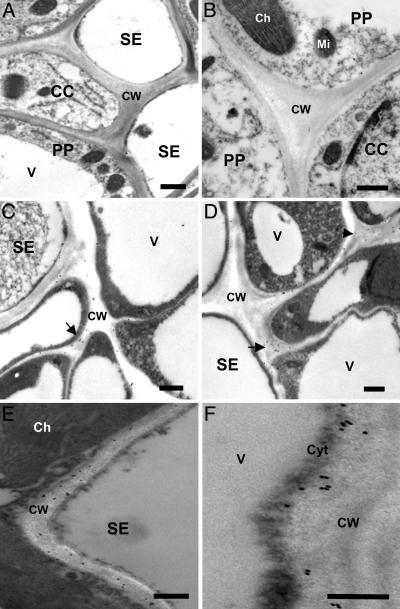

Transmission electron microscopy analyses of the subcellular localization of the LeproHypSys protein in leaves of wounded tomato plants, methyl jasmonate-treated plants, and plants overexpressing the prosystemin gene, demonstrated that under all of these conditions, the accumulation of the precursor protein was found to be in the cell wall matrix of vascular parenchyma cells (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Electron micrographs showing immunogold labeling of the LeproHypSys protein in leaf cross-sections from tomato plants. Leaf tissue was obtained from wild-type plants that had been unwounded (A and B), wounded (C), and methyl-jasmonate-treated (D), and from transgenic tomato plants overexpressing the prosystemin gene (E and F). Tissue was processed for immunocytochemical analysis under the transmission electron microscope as described in ref. 9. (A) A section through a vascular bundle of a leaf from unwounded wild-type tomato plant treated with preimmune serum, followed by treatment with 18-mm gold-labeled secondary donkey anti-rabbit polyclonal antibody. (B) Similar section as in A but treated with affinity purified anti-LeproHypSys protein serum (1:100 dilution). (C) Leaf section from wounded wild-type plant treated as in B. (D) Leaf section from a methyl jasmonate-treated wild-type tomato plant treated as in B.(E and F) Transgenic tomato leaf sections treated as in B. CW, cell wall; Ch, chloroplast, Mi, mitochondria; V, vacuole; Cyt, cytoplasm; PP, phloem parenchyma cell; CC, companion cell; SE, sieve element. (Scale bars: 0.5 μm.)

Hundreds of hydroxyproline-rich proteins (HPRGs) have been reported to be components of cell walls of plants, including green algae (16). All HPRGs contain motifs with hydroxyproline residues that are unique to specific classes of proteins. All of these proteins have been suggested to be members of a superfamily, related to HPRG proteins found in early life forms (17). The hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein precursors of HypSys defense-signaling peptides present in leaves of tobacco (6) and tomato (7) plants do not fit into this structural scenario, because they are very small (≈150 amino acids) and they lack repeating motifs as found in HPRGs. However, the functional HypSys peptides do contain regions rich in hydroxyproline and proline residues interspersed with serine and threonine residues and flanked by charged amino acids (6, 7), and they appear to represent a previously uncharacterized subfamily of cell wall HPRGs.

The localization of the precursor of the three HypSys defense signaling peptides in the cell wall indicates that the peptides may result from regulated processing events that occur in the cell wall matrix in response to trauma. Several scenarios for the generation of processing activity are possible. Wounding may cause proteases present in the extracellular matrix to mix with the precursor as a consequence of cell damage, resulting in processing. The alkalinization of the cell wall apoplast is one of the earliest events induced after wounding of tomato leaves (18), and changes in extracellular pH may have a role in the activation of processing peptidases. It is also possible that specific wound-inducible processing proteases are synthesized through the Golgi and secretory pathway in response to wounding and are transported to the cell walls. Proteinases released by invading pathogens may also produce peptides from the precursor, signaling intracellular defense responses. In any event, the production of multiple signals produced from HypSys peptide precursors in the cell walls may be among the plant's earliest events in response to pest and pathogen attacks. The generation of extracellular peptide signals by proteolysis is a strategy that occurs in animals during growth and differentiation (19).

The identification of a hydroxyproline-rich glycopeptide precursor protein that produces multiple peptide defense signals within the matrix of cell walls provides a previously uncharacterized paradigm for cell wall matrix proteins. More than 100 species of plants from diverse families exhibit systemic wound signaling for defense (20). In addition to being present in tomato plants (7), multiple hydroxyproline-rich glycopeptide signals derived from single protein precursors have been purified from tobacco (6), petunia, nightshade, and potato (G.P., W. Siems, and C.A.R., unpublished data). The next step should be to find small, related HypSys peptide signals in species throughout the plant kingdom where they may have a general role in amplifying defense gene activation in response to herbivores and/or pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to the memory of Prof. Vincent Franceschi. We thank the Washington State University Electron Microscopy Center staff for their technical advice. This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IBN 0090766, the Charlotte Y. Martin Foundation, and the College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resources Sciences.

Author contributions: J.N.-V. and C.A.R. designed research; J.N.-V. performed research; G.P. and C.A.R. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.N.-V. and C.A.R. analyzed data; and J.N.-V., G.P., and C.A.R. wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Ryan, C. A. & Pearce, G. (2004) in Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action!, ed. Davies, P. J. (Springer, Secaucus, NJ) pp. 654-670.

- 2.Matsubayashi, Y. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 3863-3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narita, N. N., Moore, S., Horiguchi, G., Kubo, M., Demura, T., Fukuda, G., J. Goodrich, J. & Tsukaya, H. (2004) Plant J. 38, 699-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butenko, M. A., Patterson, S. E., Grini, P. E., Stenvik, G.-E., Amundsen, S. S., Mandal, A. & Aalen, R. B. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 2296-2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mergaert, P., Nikovics, K., Kelemen, Z., Maunoury, N., Vaubert, D., Kondorosi, A. & Kondorosi, E. (2003) Plant Physiol. 132, 161-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearce, G., Moura, D. S., Stratmann, J. & Ryan, C. A. (2001) Nature 411, 817-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearce, G. & Ryan, C. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30044-30050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan, C. A. & Pearce, G. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, Suppl. 2, 14573-14577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narváez-Vásquez, J. & Ryan, C. A. (2004) Planta 218, 360-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheer, J. M. & Ryan, C. A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9585-9590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnurr, J. A., Shockey, J. M., de Boer, G. T. & Browse, J. A. (2002) Plant Physiol. 129, 1700-1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGurl, B., Pearce, G., Orozco-Cárdenas, M. L. & Ryan, C. A. (1992) Science 255, 1570-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGurl, B., Orozco-Cardenas, M. L., Pearce, G. & Ryan, C. A. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9799-9802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hause, B., Hause, G., Kutter, C., Miersch, O. & Wasternack, C. (2003) Plant Cell Physiol. 44, 643-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schilmiller, A. L & Howe, G. A. (2005) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8, 369-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassab, G. I. (1998) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 281-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kieliszewski, M. J. & Lamport, D. T. A. (1994) Plant J. 5, 157-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaller, A. & Oecking, C. (1999) Plant Cell 11, 263-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massague, J. & Pandiella A. (1993) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62, 515-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karban R. & Baldwin, I. T. (1997) Induced Responses to Herbivory (Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago).