Summary

We conducted a retrospective observational study to examine whether anti-inflammatory medications prescribed peri-operatively of resective brain surgery can reduce long-term seizure recurrence for individuals with drug-resistant focal epilepsy. We used insurance-claims data from across the United States to screen medications prescribed to 1,993 individuals undergoing epilepsy. We then validated the results in a well-characterized cohort of 671 epilepsy patients from a major surgical center. Twelve medications met the screening criteria and were evaluated, identifying dexamethasone and zonisamide as potentially beneficial. Dexamethasone reduced seizure recurrence by 42% over 9 years of follow-up (hazard-ratio = 0.742; 95% CI = 0.662, 0.831), and zonisamide reduced recurrence by 33% (HR = 0.782; 95% CI = 0.667, 0.917). While dexamethasone could not be validated, analysis of zonisamide in the clinical cohort corroborated the beneficial effect (HR = 0.828; 95% CI = 0.706, 0.971). If prospectively validated, this study suggests surgeons could improve long-term outcomes of epilepsy surgery by medically reducing neuro-inflammation in the surgical bed.

Subject areas: Health informatics, Health sciences, Health technology, Internal medicine, Medical specialty, Medicine, Neurology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Analyzed two cohorts of epilepsy patients undergoing focal resection surgery

-

•

A Screening cohort of insurance claims and a validation cohort of EHRs from a clinical center

-

•

Perioperative dexamethasone or zonisamide intake may reduce long-term seizure recurrence

-

•

Incremental support for the neuroinflammation hypothesis of late epileptic seizure recurrence

Health informatics; Health sciences; Health technology; Internal medicine; Medical specialty; Medicine; Neurology

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent and unprovoked epileptic seizures that are caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain.1 It is estimated to affect around 5 out of every 1,000 people in the United States and between 4 and 10 people out of every 1,000 worldwide, making it one of the most prevalent neurological disorders.2,3 Treatment primarily consists of antiseizure medications, however, cases of drug-resistant epilepsy suffering from focal seizures may opt for a more invasive resective brain surgery.4

Resective brain surgery is the standard treatment for drug-resistant focal epilepsy, with demonstrated superiority over medications in adults5 and children.6 Half the patients immediately become seizure-free and sustain seizure-freedom for a decade or more post-surgery.7,8,9 For the remaining half, the mechanisms of seizure recurrence can be differentiated into early and late recurrences. While early recurrences can be easily explained by inaccurate localization—failing to properly remove the epileptogenic zone—allowing seizures continue unabated, the mechanisms behind late recurrences—recurring after months or years of a patient being seizure-free—are still incompletely understood. Seizures recurring beyond six months after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery are often localized to the resection bed edges.10 Beyond that, transcriptomic analyses identified neuroinflammation and brain healing pathways as differentiating seizure-free patients from those with late recurrence.10,11

While post-operative epileptic progression in tissues distant to the resection has been explored as a putative recurrence mechanism,12,13,14 the contribution of peri-operative neuroinflammation in the surgical bed has not been investigated despite prior literature linking neuroinflammation to epileptogenicity.15,16,17 We hypothesize that excessive neuroinflammation in the surgical bed can predispose some individuals to pathological healing and future epileptogenicity. If correct, this could shift the paradigm of epilepsy surgery, combining surgery with medical anti-inflammatory therapy for best outcomes, mirroring the premise that antiplatelets reduce re-thrombosis after cardiac stenting,18,19 and drug-eluting stents outperform bare-metal stenting.20

Here, we leverage big data from insurance claims and electronic medical records with causal inference methodologies to generate observational support for a peri-surgical neuroinflammation-mediated epileptogenic hypothesis, finding dexamethasone and zonisamide have the potential to reduce or delay epileptic seizures recurrence for patients undergoing epilepsy surgery.

Results

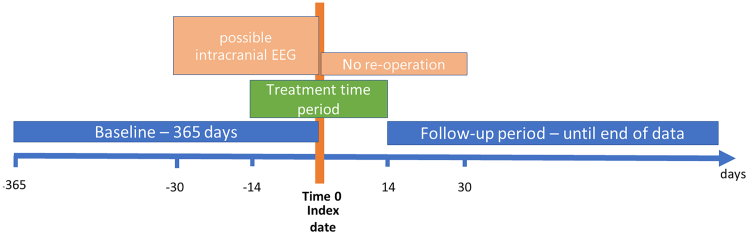

To examine the effect of peri-surgical medication on seizure recurrence, we have considered drugs prescribed within 2 weeks before or after the surgery took place (Figure 1). The study was carried out in two phases. First, a screening phase for identifying potential drug candidates from MarketScan©—a nationwide insurance claims database. Second, the statistically significant drugs with beneficial effects were validated using electronic medical records and pre-surgical testing data from the Cleveland Clinic epilepsy clinic—a large center performing focal resection surgery in the United States.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the study

A person’s index date is marked at time 0. This is the first surgery date that does not have a subsequent surgery within 30 days (orange rectangle to the right of index date). To allow for scenarios where intracranial EEG evaluations preceded a resection, prior surgeries might have occurred 30 days prior to index date (orange rectangle to the left of index date). Blue rectangles mark the “Baseline period” of 365 days, and the “Follow up period” starting 14 days post index date. Baseline features are extracted only from the baseline period, while outcomes are extracted from the follow up period. “Treatment period” is 14 days before/after index date (green rectangle).

Screening finds dexamethasone and zonisamide possibly benefiting patients

1.5 million patients had an epilepsy diagnosis in MarketScan©, including 2,972 who had resective surgery. The average age in this base cohort was 28.5 years, with a standard deviation of 17.5, and 52% were males. We excluded 59 individuals whose epilepsy diagnosis was after the surgery, and 842 with insufficient pre-operative data, leaving 1,993 patients for analysis (Figure 2). Mean post-operative follow-up was 2.89 years, median 2.33 years, and maximum of 9.08 years. Around 50% of study patients experienced an outcome event reflective of seizure recurrence, including 10% who first experienced it within 14 post-operative days (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Attrition flow for screening cohort

A flow chart breaking down the eligibility process applied to the screening cohort, starting with the entire MarketScan© database and ending with a cohort of people with sufficient baseline information who underwent a resective surgery after an epilepsy diagnosis.

Of the 61 medications screened, 12 [dexamethasone and 11 anti-seizure medications] were used peri-operatively by > 100 patients and were evaluated for their effect on differential recurrence in three different time windows: early recurrence (within 1 year), late recurrence (after >1 year), and throughout the entire follow-up period (Table 1). Out of the 12 drugs, only dexamethasone and zonisamide have showed a statistically significant benefit after correcting for multiple hypotheses testing. Figures 3 and 4 show seizure-free survivorship curves, as well as detailed model evaluation metrics for both drugs. All features were balanced with absolute standardized mean difference below 0.1.

Table 1.

Drug cohort sizes before and after positivity correction for the twelve experiment medications that met study criteria, and statistical significance testing of survival analyses comparing treatment to control groups using inverse probability weighted log rank test

| Drug Name | Na of patients in pre-positivity control group | Na of patients in pre-positivity treatment group | Na of patients in post-positivity control group | Na of patients in post-positivity treatment group | p valueb for log-rank testc on the entire timeline | p valueb for log-rank testc on early recurrenced | p-valueb for log-rank testc on late recurrencee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dexamethasone | 1297 | 696 | 957 | 666 | 1.11e-05 | 0.43 | 1.55e-07 |

| zonisamide | 1761 | 232 | 684 | 220 | 0.047 | >1 | 0.057 |

| oxcarbazepine | 1635 | 358 | 744 | 332 | >1 | >1 | 0.13 |

| carbamazepine | 1880 | 113 | 519 | 112 | 0.23 | >1 | >1 |

| clobazam | 1781 | 212 | 585 | 203 | >1 | >1 | >1 |

| clonazepam | 1794 | 199 | 774 | 190 | >1 | >1 | >1 |

| lacosamide | 1482 | 511 | 1024 | 496 | >1 | >1 | >1 |

| lamotrigine | 1592 | 401 | 898 | 381 | >1 | >1 | >1 |

| levetiracetam | 1298 | 695 | 1013 | 646 | 0.43 | >1 | >1 |

| phenytoin | 1877 | 116 | 528 | 111 | >1 | 0.02 | >1 |

| topiramate | 1775 | 218 | 733 | 211 | 0.98 | >1 | >1 |

| valproate | 1888 | 105 | 513 | 102 | >1 | 0.05 | >1 |

Number.

p value adjusted for multiple hypotheses using Holm-Bonferroni (of all drugs and all log rank tests - 36 total hypothesis tested).

log rank test adjusted for potential confounding through inverse probability weighting.

Defined from day 0–365 in follow-up.

Defined from day 365 to end of follow-up.

Figure 3.

Dexamethasone results in screening cohort

(A–E) (666 treated patients and 957 controls after positivity trimming). The calibration curve, with a 95% Wilson confidence interval, shows alignment along the diagonal (indicating strong agreement between the predicted and observed probabilities of the weight model) (A). The propensity distribution of the features included in the analysis show acceptable overlap between the treatment and control cohort after positivity trimming (B). The weighted AUC is 0.62, higher than the sought-after random AUC of 0.5 (C). Eventually, all 646 unweighted features (orange triangles) were reweighted to an absolute standard main difference of <0.1 indicating excellent balance between treatment and control groups (D). In (E), Kaplan Meier survival curves with logistic regression as weight model fitted on the data with 95% confidence intervals generated after 100 bootstraps show that early seizure recurrence rates (within 1st postoperative year) were not differentiated between treatment and control groups, but then diverged to demonstrate lower risk of recurrence in the treatment cohort.

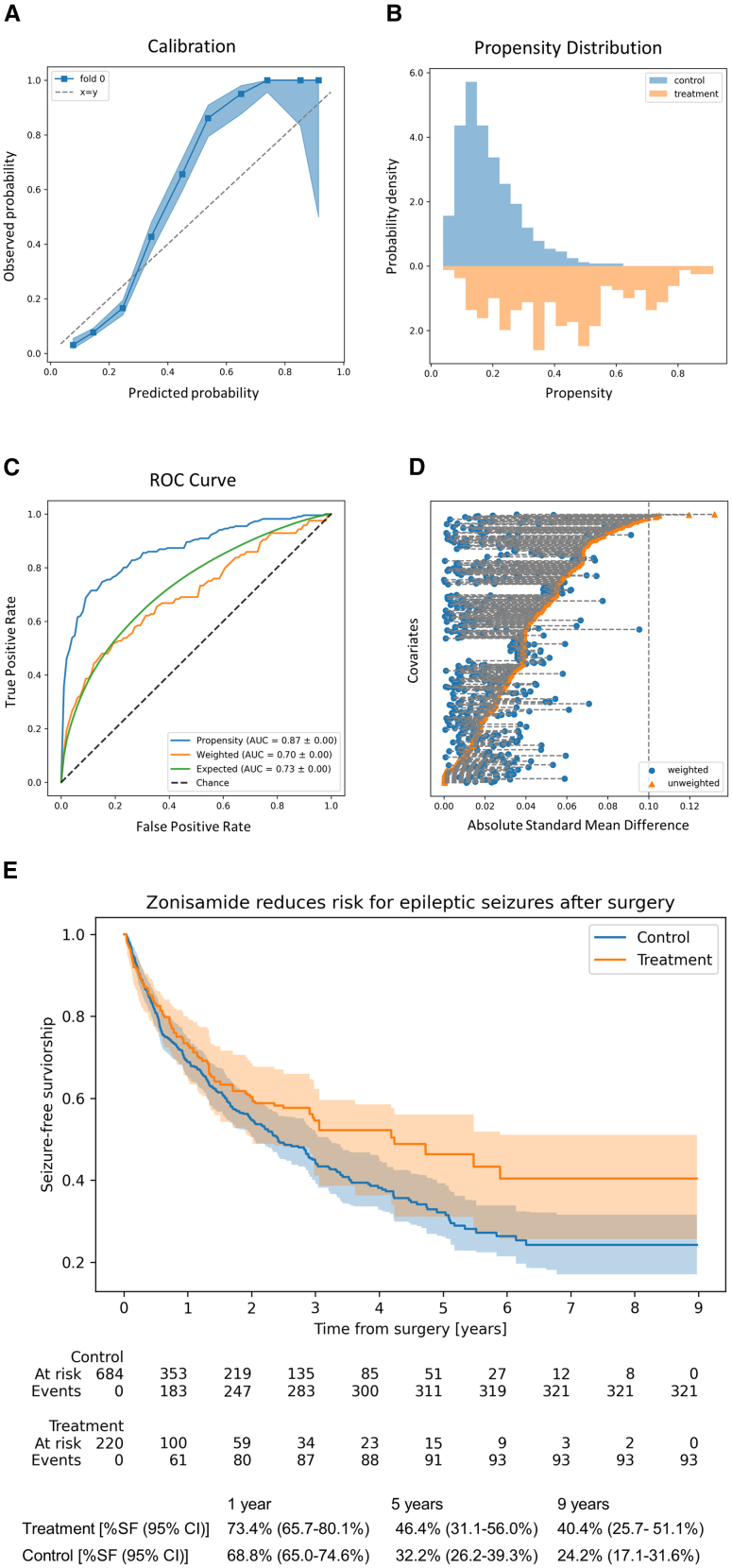

Figure 4.

Zonisamide results in screening cohort

(220 treated patients and 684 controls after positivity trimming). The calibration curve, with a 95% Wilson confidence interval, shows modest alignment along the diagonal (A). The propensity distribution of the 645 features included in the analysis shows acceptable overlap between the treatment and control cohort after positivity trimming (B). The weighted AUC is 0.70, higher than the sought-after random AUC of 0.5 (C). Eventually though, all features were corrected after weighting to an absolute standard main difference of <0.1 indicating good balance marginally between treatment and control cohorts (D). Covariate-adjusted survival curves with with 95% confidence intervals from 100 bootstraps show that Early seizure recurrence rates (within 1st postoperative year) were not differentiated between treatment and control groups, but then diverged to demonstrate lower risk of recurrence in the treatment cohort (E).

In the post-positivity corrected dexamethasone cohort (N = 666 treated and 957 controls), seizure recurrence was 42% lower in the treated group across the entire follow-up (hazard-ratio [HR] = 0.742 [95% CI 0.662, 0.831]; corrected p value = 1.11 × 10–5). This outcome was mainly driven by improvements in late recurrence rates (HR = 0.588; 95% CI = 0.491–0.705; corrected p = 1.55x10−7) (Figure 3). With zonisamide (N = 220 treated, 684 controls), seizure recurrence was 33% lower in the treated group across the entire timeline (HR = 0.782 [95% CI 0.667,0.917]; corrected p = 0.047) (Figure 4). Neither medication showed statistically significant evidence of influencing early recurrence.

Validating zonisamide as a potential therapeutic agent

The validation phase used an additional independent well-characterized surgical cohort from a large clinical center performing epilepsy surgery to validate whether the positive results for dexamethasone and zonisamide from the screening phase replicate.

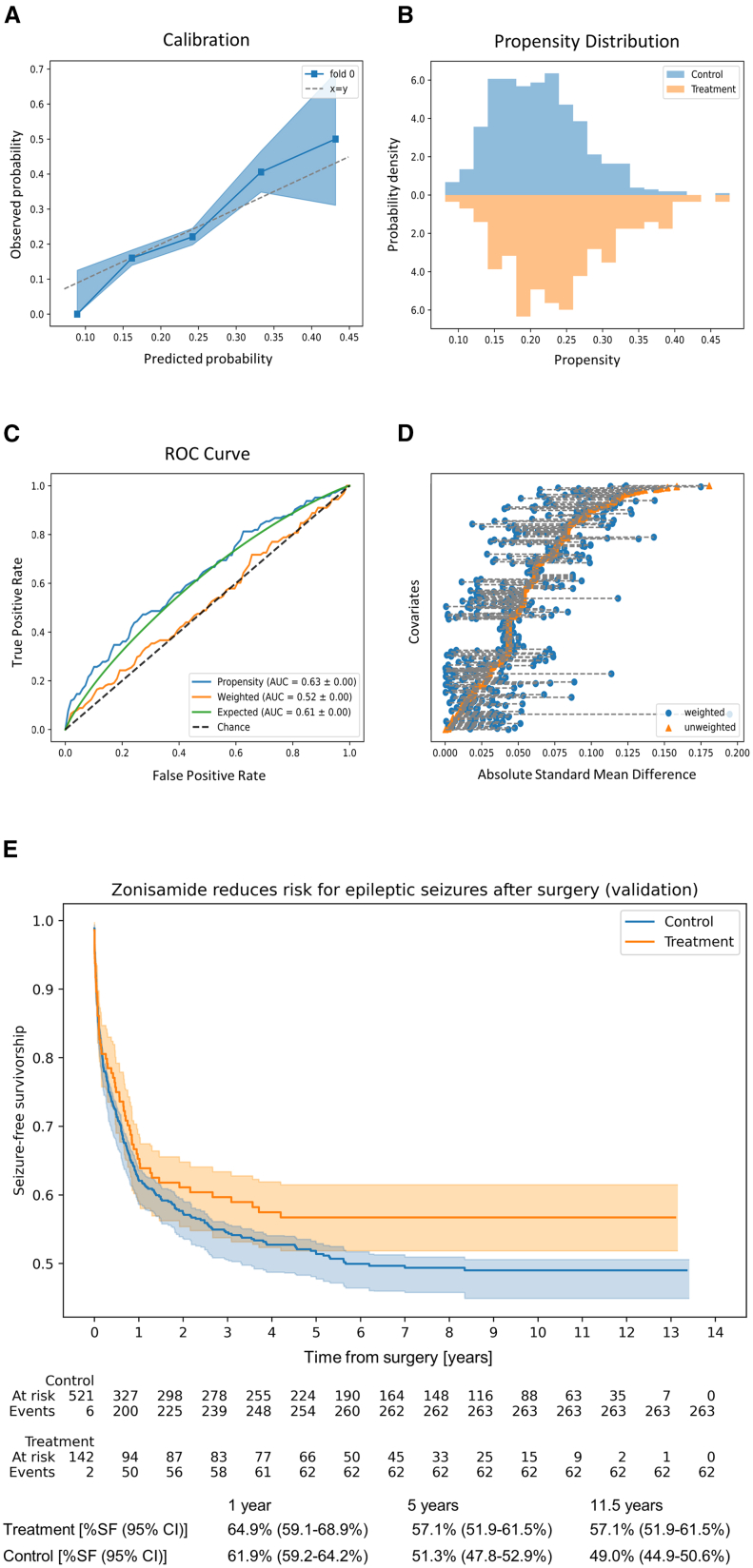

For zonisamide, a positivity-trimmed cohort of 671 subjects was identified (N = 142 treated and 523 controls). The average age was 38.3 years with a standard deviation of 13.7 years, and 50% were males. Mean follow-up was 3.81 years with a median of 3.42 years, max of 11.4 years. Figure 5 shows the model metrics and validation. Out of the 450 features included in the analysis, 36 were found to have an absolute standardized mean difference above 0.1 but below 0.2, though none were epilepsy-related, and nine of which had uncorrected p value below 0.05 in a univariable log-rank test. Replicating the results of the screening phase, lower rates of seizure recurrence were observed with peri-operative use of Zonisamide across the entire timeline (HR = 0.828 [95% CI 0.706,0.971]; corrected p-value = 0.02) and in the late recurrence period (HR = 0.599 [95% CI 0.421,0.853]; corrected-p = 0.004) (Figure 5), while the corrected p value for survival analysis for early recurrence (from time 0 to 365 days) was not statistically significant (p = 0.59).

Figure 5.

Zonisamide results in validation cohort

(A–E) (142 treated patients and 521 controls after positivity trimming). The calibration plot, with a 95% Wilson confidence interval, shows that the predicted probabilities of the weight model are well calibrated to the observed probabilities (A). The propensity distribution exhibits a good overlap between the treatment and control groups, indicating that the two groups are comparable (B). The weighted ROC curve is very well-aligned to the baseline (the diagonal) with a weighted AUC of 0.52, suggesting that the treatment and control groups after weighting are well mixed and therefore comparable (C). No sharp segments signaling positivity violation are found. The Love plot comparing the difference between the treatment and control groups calculated for the original data and the weighted data show that some variables are better balanced than others, but all were corrected to ASMD <0.2 (D). Covariate-adjusted survival curves with with 95% confidence intervals from 100 bootstraps show that seizure outcomes again diverged after the first post-operative year in favor of the treatment cohort (E).

Dexamethasone was peri-operatively prescribed for all patients at Cleveland Clinic whose medical records were used for validation, preventing us from constructing a control group and consequently validating its comparative effectiveness.

Discussion

Trying to improve epilepsy surgery outcomes has typically focused on refining anatomical planning of resection or ablation or neuromodulation. We explore a different path, building on prior established work.9,10,11,21,22,23 Specifically, we hypothesize that excessive neuroinflammation in the surgical bed can predispose certain individuals to pathological healing and future epileptogenicity. If this peri-surgical neuroinflammation-mediated epileptogenic hypothesis is correct, peri-operative anti-inflammatory medications or seizure medications with anti-inflammatory properties should influence seizure outcomes. We provide a data-driven observational analysis to answer this question.

Main finding: seizure outcomes are improved in patients who used either dexamethasone or zonisamide within 14 days before or after epilepsy surgery. With both medications, there was no evidence for effectiveness during the early postoperative period, while late seizure recurrence was lower (panel E in Figures 3, 4, and 5). The premise that the peri-operative molecular, cellular, and circulatory milieu may influence post-operative recovery and later seizure outcomes is an emerging hypothesis supported by prior literature. For example, recurrence within two years after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery was predicted by markers of poor epilepsy localization (bilateral structural brain abnormalities, postoperative spiking, and the need for intracranial EEG),24 while later seizures first manifesting beyond 6 months after surgery localized to the surgical bed.22 Furthermore, seizure-freedom odds dropped with every subsequent resection in patients who required re-operation after failed epilepsy surgeries,23 and transcriptomic analyses identified neuroinflammation and healing pathways that differentiate patients with late recurrence from those seizure-free.10,11

The findings are biologically plausible: Dexamethasone is widely used in neuro-oncology, central nervous system infections,25 and variably used with epilepsy surgery in practice—as evident from our validation cohort in which all patients were treated with dexamethasone peri-operatively—and in prior literature.26 Furthermore, in animal models, it reduces inflammation by modifying inflammatory genes,27 accelerating healing of the blood-brain barrier,28 and partially inhibiting the cytokine-induced upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9, a key chemokine activator.29 It protected against reduced cell viability and increased permeability caused by kainate in primary rat brain endothelial cell, pericyte and astroglia cultures.30 This multipronged anti-inflammatory activity likely explains dexamethasone’s ability to reduce foreign body reaction and minimize scar tissue formation to intraneural implants in rat peripheral nerves31 and brain.32 Brain surgery for epilepsy triggers a local milieu with a disrupted blood-brain barrier, tissue injury, cytokine, and chemokine release which conceivably might be mitigated by dexamethasone to reduce surgical bed encephalomalacia and secondary epileptogenesis.

Similarly, emerging literature in Parkinson’s disease animal models supports an anti-inflammatory activity for zonisamide33,34 mediated through modified microglial activation35,36 underpinning interest in exploring a disease-modifying effect of zonisamide in that disease,37,38 as it further suppressed a series of signaling events in microglia and Fas/FasL-mediated pathway of spinal cord injury models.39 In epilepsy, zonisamide reduced neuroinflammatory markers and seizure-induced free radical production in brain tissue following maximal electroshock seizures,40 and reduced connexin 43 expression and glial gap-junction coupling in an astrocyte-microglia co-culture model of inflammation.41

While the relation between epilepsy and neuroinflammation is well-documented, multiple pathways are involved in a neuroinflammatory response, and the effects of various seizure medications on neuroinflammation are not homogeneous, with some being more beneficial than others. For instance, in rats, levetiracetam (corrected-p = 0.43) is known to induce inflammation in rats via TGFβ1 regulation,42 and carbamazepine (corrected-p = 0.23) reduces inflammatory IL-1β and TNF-α expression in the hippocampus43 as well as reducing glial viability,44 while valproate (corrected-p > 1) can increase neuroinflammation.43,44 In contrast, zonisamide affects antiinflammation via pathways particularly relevant the peri-operative milieu. For example, by scavenging free radicals,45 inhibiting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production,33,36 and inhibiting microglial activation,46 as well as recent evidence of attenuating α-synuclein-induced neurotoxicity in human Parkinson’s disease patients through its anti-inflammatory effects.47 As the heterogeneity in mechanisms may partially account for why prior clinical trials are often inconclusive,48 the biochemical pathways of zonisamide might potentially support its unique role in the unique context of surgical bed healing and scarring.

Foundational strengths and considerations of study design

A randomized clinical trial (RCT) of peri-operative anti-inflammatory medications in epilepsy surgery is premature and can be logistically challenging for two main reasons. First, there are relatively few surgeries occurring every year, limiting possible sample size and therefore reducing statistical power. Second, the follow-up required for late recurrence can be substantial as resolved epilepsy is measured in scales of 5–10 years.1 In the absence of RCTs, observational research provides a viable alternative to accumulate knowledge.35,49 More broadly, causal inference techniques applied to biomedical data are among the most prominent methods used to generate novel hypotheses and discover new knowledge.50 The target trial framework51 used in this paper—deriving statistically valid causal inference from retrospective observational data by closely mimicking an RCT—has been successfully applied before to demonstrate, among others, effectiveness of colonoscopy for colorectal cancer,52 metformin for cancer prevention,53 statins for type-2 diabetes,54 as well as COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness55 and safety.56 In the domain of epilepsy, causal inference from insurance claims data have been used to optimize anti-epileptic drug prescription57 and compare the effectiveness of anti-seizure medications.58 Our study presents several additional strengths:

(1) efficient design: Most epilepsy surgical programs perform 25–50 procedures yearly. Assembling a cohort large enough for multiple statistical tests is challenging. We address this through a two-step design first utilizing a large Screening national dataset for hypothesis generation, followed by focused candidate validation in a curated cohort. The combination of two complementary views—both insurance records and clinical records—provide orthogonal evidence for the conclusions, making them even stronger.

(2) operational outcome definition: While seizure outcomes are defined via proxies using insurance claims, they are thoroughly documented in the electronic health records of the validation cohort. Figure S1 suggests that seizure recurrences were appropriately approximated in the screening cohort. The overall rate of any outcome event was 50%, in line with post-surgical seizure recurrence literature.4 Our observed 10% event rate within 14 days of index date mirrors published rates of acute postoperative seizures.23 Additionally, our retrospective observational design allows us to follow up on patients long enough for the results to be clinically relevant for epilepsy time frames.

Limitations of the study

Health insurance claims data provide otherwise unreachable sample sizes but have limited depth of epilepsy-specific phenotypic information. We carefully considered proxies to seizure recurrence to compensate, and included a validation cohort where epilepsy characteristics are thoroughly accounted for in model testing. Despite the large sample size, only 12 medications had sufficient patients to allow evaluation, so potential impact of the remaining drugs is unknown. Among those who were assessed and were found beneficial, dexamethasone could not be validated using medical records as all patients of the clinical center take it peri-operatively as part for their procedure, but the fact it is used throughout such a large facility may hint at its potential in practice. Eligibility in the validation cohort is slightly different from screening cohort (e.g.,: age >18 years in validation, and only unilobar resections in validation, but no such restriction in screening), but an upside of this limitation may, however, be demonstrating reproducibility of the findings across slightly more heterogeneous populations.

We accounted for >600 variables reflecting overall medical status, epilepsy characteristics, types of surgeries, patient demographics, age groups at surgery, and medications used in conjunction to the experiment drugs available in MarketScan© to rule out that the effects observed with dexamethasone or zonisamide are attributed to confounding; and the validation cohort allowed even deeper phenotyping of detailed epilepsy characteristics. However, as is the case in most observational studies, we cannot guarantee no residual confounding bias. We were, however, able to marginally balance all those reach variables (Figures 3, 4, and 5 panel D), though not necessarily jointly (Figures 3 and 4 panel C), and although propensity calibration for zonisamide is lacking (Figure 4A) results were replicated with proper calibration and joint covariate balance in the validation cohort (Figure 5A).

Conclusion

This study provides observational evidence supporting an emerging hypothesis of altered neuroinflammation as a mechanism of seizure-recurrence after brain surgery for epilepsy. If validated in prospective and mechanistic research, these findings could lead to safer and a more targeted anti-inflammatory treatment path than a “shot-gun” approach of dexamethasone to improve outcomes of epilepsy surgery, and potentially to reduce risk of seizures after brain surgery for other indications. Combining surgery with medicinal surgery has been proven to sum larger than its part in other disease domains and can be a real paradigm shift in the world of epilepsy surgery.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Liran Szlak (liran.szlak@ibm.com).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

This study contains two sources of private patient data, one of which is further limited by the legal agreement that provided the study team access to the Marketscan database from Merative L.P., which prevents public re-distribution of the data. For more information about access, please see: https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases.

-

•

While the complete system used to extract, wrangle, and analyze the data is proprietary, the statistical analysis was mostly done with causallib—an open-source Python package for causal inference modeling, available at https://github.com/IBM/causallib.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Cleveland Clinic Discovery Accelerator funded by the Cleveland Clinic and IBM Research.

Graphical abstract has been designed using resources from Flaticon.com.

The MarketScan data were supplied by Merative L.P. as part of one or more Merative Marketscan Research Databases. Any analysis, interpretation, or conclusion based on these data are solely that of the authors and not Merative L.P. and its subsidiaries.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: L.J., Y.S., and M.R.-Z. methodology: L.S. software: E.K. and L.S. validation: J.S. analysis and investigation: L.S., J.S., and E.Z. data curation: L.S., J.S., E.Z., and D.V. writing—original draft: E.K., L.J., L.S., V.P., D.R., and J.S. writing—review and editing: E.K., L.J., and M.R.Z. supervision: L.J. and Y.S. project administration: D.V. funding acquisition: M.R.-Z., L.J., and Y.S.

Declaration of interests

D.R. has an equity stake in Clarified Precision Medicine, LLC.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Python 3.10.7 | Python Software Foundation | https://www.python.org; RRID:SCR_008394 |

| Causallib 0.9.7 | IBM Research | https://github.com/IBM/causallib |

| Scikit-learn v1.1.3 | Pedregosa et al.59 | ; RRID:SCR_002577 |

| lifelines v0.27.8 | Davidson-Pilon60 | https://lifelines.readthedocs.io; RRID:SCR_024899 |

| statsmodels v0.14.0 | Seabold and Perktold61 | https://www.statsmodels.org; RRID:SCR_016074 |

| pandas v1.5.3 | McKinney62 and The pandas development team63 | https://pandas.pydata.org/; RRID:SCR_018214 |

| matplotlib v3.8.0 | Hunter64 | https://matplotlib.org; RRID:SCR_008624 |

Experimental model and study participant details

The study follows a two-phase design. Phase 1: Screening: we apply causal inference methods in a national claims dataset to screen for candidate medications potentially reducing seizure recurrence when used peri-operatively. Phase 2: Validation: we validate the identified candidates in a well-curated surgery cohort from our program. Both phases adhere to the target trial approach,51 emulating a possible randomized controlled trial using observational Big Data.

Phase 1: Screening

Data source

We used the MarketScan© insurance claims database that aggregated de-identified medical insurance claims between 2011-2020 from >350 insurance companies and 172 million individuals insured through Medicare supplemental, Medicaid, or commercial health insurance. The data comprise of medical billing events, including drug prescription purchases, inpatient and outpatient visits, and medical procedures.

Eligibility criteria

We extracted all patients with an epilepsy diagnosis from MarketScan© (diagnostic codes in Table S1) and identified the subgroup who underwent resective brain surgery (procedure codes in Table S2). While previous work suggests using multiple billing code occurrences for epilepsy to identify patients with epilepsy,65 we use a single occurrence since we combine it with a subsequent resective brain surgery to reflect the cohort of surgical drug-resistant epilepsy more pertinently. We defined an “Index date” as the first surgery that was not followed by additional brain surgery within 30 days to exclude immediate planned or unplanned re-operations. Patients were included if they had a focal resection at index date, AND at least one epilepsy diagnosis before or at index date, AND at least one year of data prior to index date (Figure 1).

In observational settings, individuals are not randomly assigned into experimental groups, potentially introducing confounding bias. To emulate randomization and remove spurious correlations between medications and outcome, it is required to statistically adjust for confounding factors, which are specified next.

Features definition

To isolate the causal effect of each medication, we extracted 645 features from the baseline period starting 365 days before index date (see Methods Details). These included demographics using age at surgery and biological sex, clinical diagnostics using Clinical Classifications Software Refined codes, drug prescriptions using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification 2nd level codes, and epilepsy-specific features that are clinically relevant and are plausible confounding factors [medical co-morbidities,66 epilepsy characteristics, and influencers of anti-inflammatory medication usage or postsurgical outcomes (Table S8)]. These features represented the confounders used to calculate propensity scores (probability of treatment assignment conditional on observed baseline characteristics, see quantification and statistical analysis below) and thus balance intervention and control groups.

Noticeably, being a claims database, race or ethnicity of the insured individuals are not recorded and were therefore not adjusted for. Additionally, since the main contrast of interest is the average treatment effect, associations between demographic factors and outcome were not investigated, as well as effect heterogeneity based on such demographics. We believe that this decision did not affect generalizability, as a main component of the study is its replication in a medical patient cohort.

Phase 2: Validation

Cohort definition

We analyzed an existing well-characterized cohort of patients with epilepsy who had unilobar resections at Cleveland Clinic (Ohio, USA) from 2010-2022. All patients were ≥18 years old, with no prior history of resective surgery or neuromodulation, and with ≥1 year of postoperative follow-up.

Features definition

Data included demographics (sex, race, age at epilepsy onset and at surgery), detailed epilepsy characteristics [history of convulsions, EEG (focal interictal spikes or not), MRI (Abnormal/Normal), seizure type (non-localizable or generalized seizures vs other), invasive monitoring (done/not done), type and side of surgery]; features from Table S8; medical comorbidities (mirroring features used in Screening) and drug usage information pulled from the Clinic’s electronic health record system (Epic©) using RxNorm definitions and an automated validated pipeline. The statistical analysis mirrored the Screening Phase.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study—retrospective and based on already recorded data—was approved by the Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), protocol number 16-1539, and consent requirement was waived.

Method details

We now describe more details about our study design and definition of the target trials emulated in both study phases.

Phase 1: Screening

Drug candidates

We screened 61 candidate medications (traditional immunosuppressants, biologics, disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis, corticosteroids, and anti-seizure medications, listed in Table S3 with their RxNorm Concept Unique Identifier (RxCUI), and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code. RxCUI is a unique identifier assigned to a drug in RxNorm, a normalized drug naming system. HCPCS includes standardized codes representing medical procedures, supplies, products, and services.

Treatment and control group definition

For each of the 61 candidates, we generated a sub-cohort for an emulated clinical trial where the “treatment group” received the corresponding medication within 14-days before or after the index date, and “control group” did not. We further excluded medications with <100 patients in either treatment or control group to increase the trustworthiness of each hypothesis by allowing sufficient sample size to fit the models, and to reduce the number of downstream hypotheses to correct for.

Outcome definition

Primary endpoint was seizure-freedom at last follow-up. We used proxies for recurrence (Table S4) because seizures are not well-documented in claims data (e.g., epilepsy billing codes are used in outpatients even when no seizure occurred since prior visit; or patients may address a breakthrough seizure via an unbillable telephone encounter). Detailed definitions used for each proxy measure are available in Table S5, Tables S6, and S7. To capture persistent recurrence rather than acute postoperative seizures without long-term sequelae, we only categorized a patient as “recurred” if events first observed within 14 post-index days persisted beyond that interval.

Follow-up

Eligible individuals were followed up starting day 15 after surgery. Follow-up ended on the day of outcome of interest (any occurrence of the components in Table S4), last date of interaction with the insurance system (loss to follow-up), or administrative end of data (December 2020), whichever happened first.

Causal contrasts

We focused on the intention-to-treat estimand, comparing those who had a prescription for the medication of interest at the time-window surrounding the resection in each emulated trial to eligible individuals who were not prescribed that medication in that timeframe.

Phase 2: Validation

Drug candidates

Drugs deemed beneficial and statistically significant with reducing seizure outcomes in the Screening Phase.

Treatment and control group definition

Same as in Screening Phase (date of surgery defined as index date; and a 14-day window for experimental groups).

Outcome definition

The primary outcome is Engel class I at last follow-up.67 Detailed follow-up was collected from clinic visits or phone calls at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and then yearly after surgery with an attrition rate of <10%.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using causallib, an open-source package for estimating causal effects in observational studies. Each emulated trial followed four steps:

-

•

Step 1: Positivity identification: positivity filtering68 is intended to “trim” the study cohorts and keep individuals with similar propensity scores across treatment and control groups. We fitted a logistic regression-based propensity score model and excluded individuals with extreme propensity scores, exceeding a dynamically-set threshold based on the method from Crump et al.69

-

•

Step 2: Survival analysis: We then conducted a time-to-event analysis for seizure recurrence on the “trimmed” dataset. We fitted an additional propensity score model using an L2-penalized logistic regression on the dataset and constructed inverse propensity weights to balance baseline characteristics between treatment and control groups. We then applied the weights to estimate covariate-adjusted cumulative incidence curves for the two groups using two Kaplan Meier estimators.70

-

•

Step 3: Model evaluation was done through calculating the absolute standardized mean difference after weighting to validate covariate balance,71 calibration plots to evaluate propensity probability,72 area under the receiver operating characteristics of the propensity scores weighted by inverse weights. After weighting, the treatment indicator should be uncorrelated to baseline characteristics and accuracy of predicting treatment assignment should be close to chance.73

-

•

Step 4: Statistical inference: to generate 95% confidence intervals around the survival curves, we repeated steps 1-2 for 100 bootstrap samples used to estimate mean and standard deviation of a normal distribution. We also used the estimated inverse probability weights to performed weighted log-rank tests and weighted Cox regressions74 for three time periods: entire follow-up, days 0 to 365 (early recurrence), and days 365 to end of timeline (late recurrence), applying Holm correction for multiple hypothesis testing75 Statistical significance assumed at the 5% level.

Published: February 28, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.112124.

Contributor Information

Liran Szlak, Email: liran.szlak@ibm.com.

Yishai Shimoni, Email: yishais@il.ibm.com.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Fisher R.S., Acevedo C., Arzimanoglou A., Bogacz A., Cross J.H., Elger C.E., Engel J., Forsgren L., French J.A., Glynn M., et al. ILAE Official Report: A practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:475–482. doi: 10.1111/epi.12550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiest K.M., Sauro K.M., Wiebe S., Patten S.B., Kwon C.-S., Dykeman J., Pringsheim T., Lorenzetti D.L., Jetté N. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Neurology. 2017;88:296–303. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forsgren L., Beghi E., Õun A., Sillanpää M. The epidemiology of epilepsy in Europe – a systematic review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2005;12:245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krucoff M.O., Chan A.Y., Harward S.C., Rahimpour S., Rolston J.D., Muh C., Englot D.J. Rates and predictors of success and failure in repeat epilepsy surgery: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Epilepsia. 2017;58:2133–2142. doi: 10.1111/epi.13920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiebe S., Blume W.T., Girvin J.P., Eliasziw M., Effectiveness and Efficiency of Surgery for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Study Group A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:311–318. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dwivedi R., Ramanujam B., Chandra P.S., Sapra S., Gulati S., Kalaivani M., Garg A., Bal C.S., Tripathi M., Dwivedi S.N., et al. Surgery for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy in Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:1639–1647. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Englot D.J., Chang E.F. Rates and predictors of seizure freedom in resective epilepsy surgery: an update. Neurosurg. Rev. 2014;37:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s10143-014-0527-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Tisi J., Bell G.S., Peacock J.L., McEvoy A.W., Harkness W.F.J., Sander J.W., Duncan J.S. The long-term outcome of adult epilepsy surgery, patterns of seizure remission, and relapse: a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60890-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najm I., Jehi L., Palmini A., Gonzalez-Martinez J., Paglioli E., Bingaman W. Temporal patterns and mechanisms of epilepsy surgery failure. Epilepsia. 2013;54:772–782. doi: 10.1111/epi.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louis S., Busch R.M., Lal D., Hockings J., Hogue O., Morita-Sherman M., Vegh D., Najm I., Ghosh C., Bazeley P., et al. Genetic and molecular features of seizure-freedom following surgical resections for focal epilepsy: A pilot study. Front. Neurol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.942643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jehi L., Yehia L., Peterson C., Niazi F., Busch R., Prayson R., Ying Z., Bingaman W., Najm I., Eng C. Preliminary report: Late seizure recurrence years after epilepsy surgery may be associated with alterations in brain tissue transcriptome. Epilepsia Open. 2018;3:299–304. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold T.C., Kini L.G., Bernabei J.M., Revell A.Y., Das S.R., Stein J.M., Lucas T.H., Englot D.J., Morgan V.L., Litt B., Davis K.A. Remote effects of temporal lobe epilepsy surgery: Long-term morphological changes after surgical resection. Epilepsia Open. 2023;8:559–570. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill R.S., Hong S.-J., Fadaie F., Caldairou B., Bernhardt B.C., Barba C., Brandt A., Coelho V.C., d’Incerti L., Lenge M., et al. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018 Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Frangi A.F., Schnabel J.A., Davatzikos C., Alberola-López C., Fichtinger G., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2018. Deep Convolutional Networks for Automated Detection of Epileptogenic Brain Malformations; pp. 490–497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan V.L., Rogers B.P., González H.F.J., Goodale S.E., Englot D.J. Characterization of postsurgical functional connectivity changes in temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosurg. 2020;133:392–402. doi: 10.3171/2019.3.JNS19350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W., Wu J., Zeng Y., Zheng W. Neuroinflammation in epileptogenesis: from pathophysiology to therapeutic strategies. Front. Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1269241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vezzani A., Balosso S., Ravizza T. Neuroinflammatory pathways as treatment targets and biomarkers in epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019;15:459–472. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villasana-Salazar B., Vezzani A. Neuroinflammation microenvironment sharpens seizure circuit. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023;178 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2023.106027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertrand M.E., Rupprecht H.J., Urban P., Gershlick A.H., CLASSICS Investigators Double-blind study of the safety of clopidogrel with and without a loading dose in combination with aspirin compared with ticlopidine in combination with aspirin after coronary stenting : the clopidogrel aspirin stent international cooperative study (CLASSICS. Circulation. 2000;102:624–629. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.6.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schömig A., Neumann F.J., Kastrati A., Schühlen H., Blasini R., Hadamitzky M., Walter H., Zitzmann-Roth E.M., Richardt G., Alt E., et al. A randomized comparison of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy after the placement of coronary-artery stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334:1084–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604253341702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rokoszak V., Syed M.H., Salata K., Greco E., de Mestral C., Hussain M.A., Aljabri B., Verma S., Al-Omran M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of plain versus drug-eluting balloon angioplasty in the treatment of juxta-anastomotic hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula stenosis. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020;71:1046–1054.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hershberger C.E., Louis S., Busch R.M., Vegh D., PB I.N., Eng C., Jehi L., Rotroff D.M. Molecular Subtypes of Epilepsy Associated with Post-Surgical Seizure-Recurrence. Brain Communications. 2023;5 doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcad251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jehi L.E., Silveira D.C., Bingaman W., Najm I. Temporal lobe epilepsy surgery failures: predictors of seizure recurrence, yield of reevaluation, and outcome following reoperation. J. Neurosurg. 2010;113:1186–1194. doi: 10.3171/2010.8.JNS10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yardi R., Morita-Sherman M.E., Fitzgerald Z., Punia V., Bena J., Morrison S., Najm I., Bingaman W., Jehi L. Long-term outcomes of reoperations in epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2020;61:465–478. doi: 10.1111/epi.16452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeha L.E., Najm I.M., Bingaman W.E., Khandwala F., Widdess-Walsh P., Morris H.H., Dinner D.S., Nair D., Foldvary-Schaeffer N., Prayson R.A., et al. Predictors of outcome after temporal lobectomy for the treatment of intractable epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;66:1938–1940. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219810.71010.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gundamraj S., Hasbun R. The Use of Adjunctive Steroids in Central Nervous Infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.592017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopes M.W., Leal R.B., Guarnieri R., Schwarzbold M.L., Hoeller A., Diaz A.P., Boos G.L., Lin K., Linhares M.N., Nunes J.C., et al. A single high dose of dexamethasone affects the phosphorylation state of glutamate AMPA receptors in the human limbic system. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6:e986. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coyle P.K. Glucocorticoids in central nervous system bacterial infection. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:796–801. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.7.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hue C.D., Cho F.S., Cao S., Dale Bass C.R., Meaney D.F., Morrison B. Dexamethasone Potentiates in Vitro Blood-Brain Barrier Recovery after Primary Blast Injury by Glucocorticoid Receptor-Mediated Upregulation of ZO-1 Tight Junction Protein. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harkness K.A., Adamson P., Sussman J.D., Davies-Jones G.A., Greenwood J., Woodroofe M.N. Dexamethasone regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in CNS vascular endothelium. Brain. 2000;123:698–709. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.4.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barna L., Walter F.R., Harazin A., Bocsik A., Kincses A., Tubak V., Jósvay K., Zvara Á., Campos-Bedolla P., Deli M.A. Simvastatin, edaravone and dexamethasone protect against kainate-induced brain endothelial cell damage. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2020;17 doi: 10.1186/s12987-019-0166-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De La Oliva N., Navarro X., Del Valle J. Dexamethasone Reduces the Foreign Body Reaction to Intraneural Electrode Implants in the Peripheral Nerve of the Rat. Anat. Rec. 2018;301:1722–1733. doi: 10.1002/ar.23920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong Y., Bellamkonda R.V. Dexamethasone-coated neural probes elicit attenuated inflammatory response and neuronal loss compared to uncoated neural probes. Brain Res. 2007;1148:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Condello S., Currò M., Ferlazzo N., Costa G., Visalli G., Caccamo D., Pisani L.R., Costa C., Calabresi P., Ientile R., Pisani F. Protective effects of zonisamide against rotenone-induced neurotoxicity. Neurochem. Res. 2013;38:2631–2639. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He J., Zhang X., He W., Xie Y., Chen Y., Yang Y., Chen R. Neuroprotective effects of zonisamide on cerebral ischemia injury via inhibition of neuronal apoptosis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2021;54 doi: 10.1590/1414-431X202010498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hossain M.M., Weig B., Reuhl K., Gearing M., Wu L.J., Richardson J.R. The anti-parkinsonian drug zonisamide reduces neuroinflammation: Role of microglial Na(v) 1.6. Exp. Neurol. 2018;308:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tada S., Choudhury M.E., Kubo M., Ando R., Tanaka J., Nagai M. Zonisamide Ameliorates Microglial Mitochondriopathy in Parkinson’s Disease Models. Brain Sci. 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/brainsci12020268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cha P.C., Satake W., Ando-Kanagawa Y., Yamamoto K., Murata M., Toda T. Genome-wide association study identifies zonisamide responsive gene in Parkinson’s disease patients. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;65:693–704. doi: 10.1038/s10038-020-0760-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C., Xue L., Liu Y., Yang Z., Chi S., Xie A. Zonisamide for the Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Current Update. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.574652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koshimizu H., Ohkawara B., Nakashima H., Ota K., Kanbara S., Inoue T., Tomita H., Sayo A., Kiryu-Seo S., Konishi H., et al. Zonisamide ameliorates neuropathic pain partly by suppressing microglial activation in the spinal cord in a mouse model. Life Sci. 2020;263 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar B., Medhi B., Modi M., Saikia B., Attri S.V., Patial A. A mechanistic approach to explore the neuroprotective potential of zonisamide in seizures. Inflammopharmacology. 2018;26:1125–1131. doi: 10.1007/s10787-018-0478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ismail F.S., Faustmann P.M., Förster E., Corvace F., Faustmann T.J. Tiagabine and zonisamide differentially regulate the glial properties in an astrocyte-microglia co-culture model of inflammation. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2023;396:3253–3267. doi: 10.1007/s00210-023-02538-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stienen M.N., Haghikia A., Dambach H., Thöne J., Wiemann M., Gold R., Chan A., Dermietzel R., Faustmann P.M., Hinkerohe D., Prochnow N. Anti-inflammatory effects of the anticonvulsant drug levetiracetam on electrophysiological properties of astroglia are mediated via TGFβ1 regulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;162:491–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gómez C.D., Buijs R.M., Sitges M. The anti-seizure drugs vinpocetine and carbamazepine, but not valproic acid, reduce inflammatory IL -1β and TNF -α expression in rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 2014;130:770–779. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dambach H., Hinkerohe D., Prochnow N., Stienen M.N., Moinfar Z., Haase C.G., Hufnagel A., Faustmann P.M. Glia and epilepsy: Experimental investigation of antiepileptic drugs in an astroglia/microglia co-culture model of inflammation. Epilepsia. 2014;55:184–192. doi: 10.1111/epi.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mori A., Noda Y., Packer L. The anticonvulsant zonisamide scavenges free radicals. Epilepsy Res. 1998;30:153–158. doi: 10.1016/S0920-1211(97)00097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yokoyama H., Yano R., Kuroiwa H., Tsukada T., Uchida H., Kato H., Kasahara J., Araki T. Therapeutic effect of a novel anti-parkinsonian agent zonisamide against MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine)neurotoxicity in mice. Metab. Brain Dis. 2010;25:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s11011-010-9191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terada T., Bunai T., Hashizume T., Matsudaira T., Yokokura M., Takashima H., Konishi T., Obi T., Ouchi Y. Neuroinflammation following anti-parkinsonian drugs in early Parkinson’s disease: a longitudinal PET study. Sci. Rep. 2024;14:4708. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-55233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenhalgh J., Weston J., Dundar Y., Nevitt S.J., Marson A.G. Antiepileptic drugs as prophylaxis for postcraniotomy seizures. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007286.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walicke P., Abosch A., Asher A., Barker F.G., Ghogawala Z., Harbaugh R., Jehi L., Kestle J., Koroshetz W., Little R., et al. Launching Effectiveness Research to Guide Practice in Neurosurgery: A National Institute Neurological Disorders and Stroke Workshop Report. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:505–514. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyw133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malinverno L., Barros V., Ghisoni F., Visonà G., Kern R., Nickel P.J., Ventura B.E., Šimić I., Stryeck S., Manni F., et al. A historical perspective of biomedical explainable AI research. Patterns. 2023;4 doi: 10.1016/j.patter.2023.100830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hernán M.A., Robins J.M. Using Big Data to Emulate a Target Trial When a Randomized Trial Is Not Available: Table 1. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016;183:758–764. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.García-Albéniz X., Hsu J., Bretthauer M., Hernán M.A. Effectiveness of Screening Colonoscopy to Prevent Colorectal Cancer Among Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 70 to 79 Years: A Prospective Observational Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017;166:18–26. doi: 10.7326/M16-0758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dickerman B.A., García-Albéniz X., Logan R.W., Denaxas S., Hernán M.A. Evaluating Metformin Strategies for Cancer Prevention: A Target Trial Emulation Using Electronic Health Records. Epidemiology. 2023;34:690–699. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Danaei G., García Rodríguez L.A., Fernandez Cantero O., Hernán M.A. Statins and risk of diabetes: an analysis of electronic medical records to evaluate possible bias due to differential survival. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1236–1240. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dagan N., Barda N., Kepten E., Miron O., Perchik S., Katz M.A., Hernán M.A., Lipsitch M., Reis B., Balicer R.D. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:1412–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barda N., Dagan N., Ben-Shlomo Y., Kepten E., Waxman J., Ohana R., Hernán M.A., Lipsitch M., Kohane I., Netzer D., et al. Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:1078–1090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Devinsky O., Dilley C., Ozery-Flato M., Aharonov R., Goldschmidt Y., Rosen-Zvi M., Clark C., Fritz P. Changing the approach to treatment choice in epilepsy using big data. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;56:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.kan-Tor Y., Ness L., Szlak L., Benninger F., Ravid S., Chorev M., Rosen-Zvi M., Shimoni Y., Fisher R.S. Comparing the efficacy of anti-seizure medications using matched cohorts on a large insurance claims database. Epilepsy Res. 2024;201 doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2024.107313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pedregosa F., Varoquaux G., Gramfort A., Michel V., Thirion B., Grisel O., Blondel M., Prettenhofer P., Weiss R., Dubourg V., et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davidson-Pilon C. lifelines: survival analysis in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 2019;4:1317. doi: 10.21105/joss.01317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seabold S., Perktold J. 9th Python in Science Conference. 2010. statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with python. [Google Scholar]

- 62.McKinney W. In: Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference. van der Walt S., Millman J., editors. 2010. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python; pp. 56–61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.The pandas development team . Zenodo; 2020. Pandas-Dev/pandas: Pandas. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hunter J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007;9:90–95. doi: 10.1109/MCSE.2007.55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tu K., Wang M., Jaakkimainen R.L., Butt D., Ivers N.M., Young J., Green D., Jetté N. Assessing the validity of using administrative data to identify patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:335–343. doi: 10.1111/epi.12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Engel J., Jr., van Ness P., Rasmussen T., Ojemann L. 2nd ed. Raven Press; 1993. Outcome with Respect to Epileptic Seizures. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Westreich D., Cole S.R. Invited Commentary: Positivity in Practice. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;171:674–681. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crump R.K., Hotz V.J., Imbens G.W., Mitnik O.A. Dealing with limited overlap in estimation of average treatment effects. Biometrika. 2009;96:187–199. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asn055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cole S.R., Hernán M.A. Adjusted survival curves with inverse probability weights. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2004;75:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Austin P.C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat. Med. 2009;28:3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gutman R., Karavani E., Shimoni Y. Improving Inverse Probability Weighting by Post-calibrating Its Propensity Scores. Epidemiology. 2024;35:473–480. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shimoni Y., Karavani E., Ravid S., Bak P., Ng T.H., Alford S.H., Meade D., Goldschmidt Y. An Evaluation Toolkit to Guide Model Selection and Cohort Definition in Causal Inference. arXiv. 2019 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1906.00442. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chesnaye N.C., Stel V.S., Tripepi G., Dekker F.W., Fu E.L., Zoccali C., Jager K.J. An introduction to inverse probability of treatment weighting in observational research. Clin. Kidney J. 2022;15:14–20. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfab158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Holm S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

This study contains two sources of private patient data, one of which is further limited by the legal agreement that provided the study team access to the Marketscan database from Merative L.P., which prevents public re-distribution of the data. For more information about access, please see: https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases.

-

•

While the complete system used to extract, wrangle, and analyze the data is proprietary, the statistical analysis was mostly done with causallib—an open-source Python package for causal inference modeling, available at https://github.com/IBM/causallib.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.