Abstract

Recent studies indicate that interleukin 8 (IL-8) production contributes to the host immune responses against mycobacterial infection. In this study, we were interested to determine whether induction of IL-8 in human monocytes infected with Mycobacterium bovis was regulated by other monocyte-derived cytokines important in antimycobacterial immunity: IL-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β). Here, we report that IL-10 reduced, in a graded and significant manner, IL-8 production by M. bovis-infected human monocytes. Additionally, the specificity of the observed inhibition was further confirmed, since the addition of an anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody completely reversed the inhibitory effect. In contrast, addition or neutralization of TGF-β appeared to have no significant effect on M. bovis-induced IL-8 secretion by human monocytes, whereas CD40 expression on M. bovis-infected monocytes was significantly inhibited by this cytokine. This was consistent with the finding by the reverse transcription-PCR method that pretreatment with IL-10, but not TGF-β, potently inhibited IL-8 mRNA levels. Interestingly, neutralization of endogenous IL-10 did not significantly alter IL-8 secretion, suggesting that induction of IL-8 was not significantly affected by coexpression of IL-10 during infection of human monocytes with M. bovis. Collectively, these data indicate that IL-8 production may be regulated when human monocytes are exposed to IL-10 prior to activation with M. bovis BCG. These data will aid in our understanding of the mechanisms involved in regulating the protective immune response to stimulation with M. bovis BCG.

The Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) strain is the current vaccine available for protection against tuberculosis (34). Infection of human cells with M. bovis induces the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and IL-8. IL-8, first isolated from monocytes as a neutrophil attractant (1), is a member of the CXC (α) chemokine family that is also chemotactic for T lymphocytes (19). IL-8 has been found during the course of the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, resulting in tissue inflammation, granuloma formation, and a major chemotactic factor for neutrophils (11, 12, 35). Neutrophils chemoattracted into the alveolus by IL-8 during pulmonary tuberculosis may have a direct role in mycobacterial killing (14). Alveolar macrophages and monocytes, recruited early in the course of pulmonary infection with M. tuberculosis, have previously been considered the major cellular source of immunoregulatory cytokines, including IL-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β). IL-10 is an 18-kDa homodimeric cytokine secreted by activated T cells, B cells, and monocytes (25). IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated Th1 cells (9, 10, 24) and IL-8 synthesis triggered by LPS-stimulated monocytes (4, 5). TGF-β is a member of a family of pleiotropic 25-kDa homodimeric proteins representing signaling molecules with potent immunoregulatory properties (21). TGF-β can modulate the expression of class II major histocompatibility complex and costimulatory molecules (20). Increased production of IL-10 and TGF-β in tuberculosis patients has been observed and can contribute to the inability of human cells to control mycobacterial infection (7, 13). It has been reported that IL-10 and TGF-β down-regulate IL-8 production in response to IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha, or LPS, but the effect of these cytokines on IL-8 secretion by human monocytes infected with M. bovis has not been shown previously. The aim of the present work was to determine the effects of IL-10 and TGF-β on M. bovis-induced IL-8 secretion by human monocytes. In the present study, we demonstrate down-regulation of IL-8 production and mRNA expression in M. bovis-activated human monocytes by exogenous IL-10. By using IL-10-blocking antibodies, these results were confirmed. Our studies indicate that IL-10 should be included in the cytokine regulatory network for IL-8 secretion in healthy human monocytes infected with M. bovis BCG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Recombinant IL-10 (19110V) was purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.). Recombinant TGF-β (240-B) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.). The following antibodies were obtained: anti-human IL-10 (AB217-NA), anti-TGF-β (AB-101-NA), and isotype-matched control antibody from R&D Systems and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD40 (5C3) from PharMingen. Live M. bovis Danish strain 1331 was kindly supplied by J. Ruiz (Birmex, México, D.F., México).

Cell culture.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from normal healthy volunteers and separated out by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll Histopaque 1077 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The peripheral blood mononuclear cells were enriched for monocytes by adherence on petri dishes at 37°C for 1 h. Then, the plates were vortexed, and nonadherent cells were removed by vigorous washing with RPMI 1640 (GIBCO BRL, Rockville, Md.). Adherent cells were then cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 10% fetal calf serum, and the monolayers were washed again before infection with M. bovis. The purity of monocyte preparations was 87% ± 4%, as determined by morphology on Giemsa staining and by flow cytometry using the monocyte-specific monoclonal antibody Leu M3 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). In some experiments, cultured monocytes were preincubated with medium or different concentrations of IL-10 or TGF-β for 4 h prior to the addition of M. bovis. For stimulation studies, human peripheral blood monocytes at 105 per well were infected with 105 M. bovis organisms or exposed to medium alone at 37°C in a 5% CO2-95% humidified air incubator. Neutralizing antibody to IL-10 was added to some cultures. Culture supernatants for the detection of IL-8 and IL-10 were harvested, centrifuged to remove any debris, and then stored in frozen aliquots at −20°C.

Cytokine protein measurement.

Concentrations of IL-8 and IL-10 in the supernatant were measured by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) system purchased from Amersham (Aylesbury, United Kingdom). The assays were carried out according to the methodology suggested by the manufacturer. Concentrations of cytokines are expressed as picograms per 105 cells.

IL-8 mRNA expression.

IL-8 mRNA expression in M. bovis-infected monocytes was measured by the reverse transcription-PCR method. Monocytes were pretreated with IL-10 (2 ng/ml) or TGF-β (3 ng/ml) for 4 h and then infected with 105 M. bovis organisms overnight. Total RNA from cells was prepared according to the method of Chomczynski and Sacchi (3). Briefly, the cells were lysed in Trizol (Life Technologies), and total RNA was quantified on a spectrophotometer, followed by a reverse-transcription reaction using random hexamer primers (GIBCO BRL) and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (GIBCO BRL). The resulting cDNAs were amplified by PCR in the standard reaction mixture using Taq DNA polymerase and sense and antisense primers for IL-8 (5′ TTG GCA GCC TTC CTG ATT TC 3′ and 5′ AAC TTC TCC ACA ACC CTC TG 3′). The PCR product was subjected to electrophoresis and visualized by staining it with ethidium bromide. Bands were quantified by densitometry. IL-8 levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) to account for loading differences between lanes.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Cells were cultured for 4 h in RPMI 1640 medium in the presence or absence of TGF-β and then infected with 105 M. bovis organisms at 37°C overnight. The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then reacted with FITC-conjugated anti-CD40 antibody for 30 min, washed twice with 0.2% bovine serum albumin-PBS, and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.2) for 10 min. After being washed with PBS, the resulting cells were subjected to flow cytometry using FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San José, Calif.). Ten thousand events were recorded for each cell culture. The mean fluorescence index of cells with CD40 antibody was subtracted from the mean fluorescence index of cells with matched isotype immunoglobulin G control.

Statistical analysis.

In statistical calculations, the results were analyzed by using Student's t test. The results are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean (SEM) of at least three independent experiments. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effects of IL-10 and TGF-β on IL-8 protein production in human monocytes infected with M. bovis.

In preliminary experiments, we determined the production of IL-8 by human monocytes after infection with 101, 103, 105, or 107 M. bovis organisms. In the culture supernatants, IL-8 production was dose dependent after stimulation with M. bovis, and the maximal production of IL-8 was reached with 105 M. bovis organisms (one bacillus per cell; 5,734 ± 489 pg/105 monocytes). The IL-8 response of M. bovis-infected cell cultures increased over time, with significant production observed 24 h after infection. In these experiments, spontaneous IL-8 release was significantly reduced when cells were cultured prior to infection and washed extensively every 20 h. To determine the effects of anti-inflammatory cytokines on IL-8 production, monocytes were pretreated for 4 h with increasing concentrations of IL-10 and then stimulated with M. bovis or medium alone. Supernatants were collected after 24 h, and the accumulated IL-8 produced over this time was measured by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1, the production of IL-8 in response to M. bovis was inhibited by IL-10 at levels of 54% inhibition at maximal dose. This inhibitory effect was significant (P < 0.05). No IL-8 secretion was observed in the absence of stimulation (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of M. bovis-induced IL-8 secretion in human monocytes by IL-10. Monocytes (105/well) were treated with BCG alone (solid bar) or with increasing concentrations of IL-10 (shaded bars) for 4 h at 37°C; 105 M. bovis organisms were added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h at 37°C. The cell culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for IL-8 protein by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. The results are the means + SEM of five independent experiments. The number in parentheses indicates the percentage of inhibition by IL-10 with respect to M. bovis cultures.

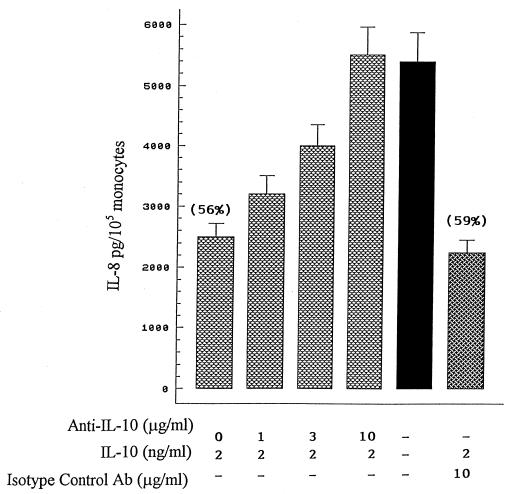

To further evaluate the specificity of the inhibitory effect of IL-10 on M. bovis-induced IL-8 production, increasing concentrations of a neutralizing antibody to IL-10 or an isotype-matched control Ab (10 μg/ml) was added to monocytes treated with IL-10 (2 ng/ml) for 4 h at 37°C. Then, the cells were infected with M. bovis for an additional 24 h at 37°C. As indicated in Fig. 2, suppression of M. bovis-mediated IL-8 secretion (56% inhibition) was completely neutralized with 10 μg of antibody/ml. In contrast, an isotype-matched control immunoglobulin G1 antibody was without effect (59% inhibition). These results confirmed that IL-10 is a major inhibitor of M. bovis-induced IL-8 secretion.

FIG. 2.

Neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody significantly reverses the inhibitory effect of IL-10 on M. bovis-mediated IL-8 production. Monocytes (105/well) were incubated with IL-10 (2 ng/ml) in the presence of different amounts of an anti-IL-10 antibody or 10 μg of an isotype control antibody/ml for 4 h prior to M. bovis stimulation for an additional 24 h at 37°C. IL-8 levels were measured by ELISA. The numbers in parentheses indicate the percentages of inhibition by IL-10 with respect to M. bovis cultures. The results are the means + SEM for four separate experiments.

It is important to note that IL-10 treatment did not affect the uptake of M. bovis by monocytes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Quantification of intracellular bacteria in monocytes treated or not treated with IL-10a

| Treatment | Uninfected cells | Infected cells that contained:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-10 b/c | >10 b/c | ||

| M. bovis | 17 ± 4.2 | 28 ± 7.1 | 39 ± 12 |

| M. bovis + IL-10 | 19 ± 5.0 | 27 ± 6.5 | 41 ± 9.7 |

Monocytes were purified by adherence and treated with IL-10. After 24 h, the cells were washed and infected with M. bovis. The cells were stained by the Ziehl-Neelsen method, and acid-fast bacilli were counted by direct microscopy. b/c, bacilli per cell. The results are the means ± SEM of three different experiments and are expressed as percentages of cells.

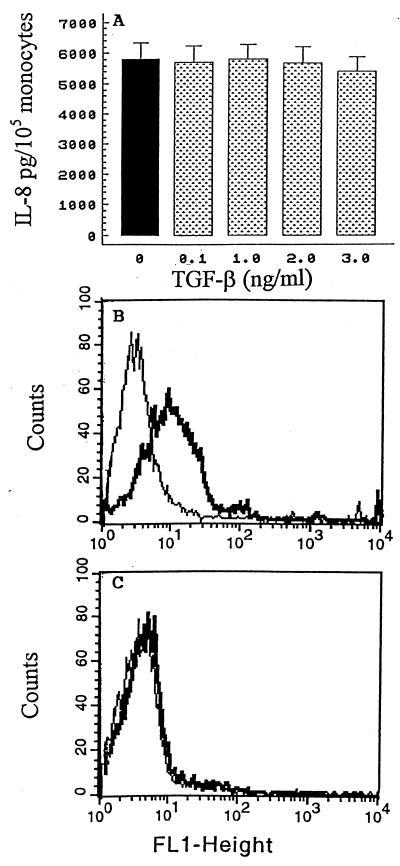

TGF-β, a monocyte-deactivating cytokine, is produced by monocytes following infection with mycobacterial antigens. Therefore, we determined whether exogenous TGF-β, like IL-10, contributed to the regulation of IL-8. Cells were pretreated for 4 h with increasing concentrations of TGF-β and then stimulated with M. bovis or medium alone. Cell culture supernatants were harvested after 24 h, and the concentrations of IL-8 were measured by ELISA. In contrast with the results obtained with IL-10, TGF-β appeared to have no significant effect on M. bovis-induced IL-8 production (Fig. 3A). IL-10 or TGF-β alone had a minimal effect on constitutive production relative to the amount of control production of IL-8, and no synergistic inhibition was observed when IL-10 and TGF-β were added together (data not shown). In order to examine whether TGF-β is functional, the effect of TGF-β on the expression of an important costimulatory molecule (CD40) on M. bovis-infected monocytes was measured by flow cytometry. As shown in a representative experiment, treatment with this cytokine for 4 h resulted in the down-regulation of CD40 expression on M. bovis-infected monocytes (mean fluorescence index, 178 ± 19 [Fig. 3B] versus 59 ± 6 [Fig. 3C]; n = 3; P < 0.05). Together, these results indicate that TGF-β is a functionally important immunosuppressive cytokine implicated in mycobacterial infection but is not critical for controlling IL-8 protein production in human monocytes infected with M. bovis.

FIG. 3.

Effect of exogenous recombinant TGF-β on M. bovis-mediated IL-8 secretion. (A) Monocytes (105/well) were cultured in the absence (solid bar) or presence of increasing concentrations of TGF-β (shaded bars) for 4 h at 37°C; 105 M. bovis organisms were added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h at 37°C. The cell culture supernatants were harvested, and the concentrations of IL-8 were determined by ELISA. The results are the means + SEM of five independent experiments. (B and C) CD40 surface expression on monocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. Monocytes were cultured in the absence (B) or the presence (C) of TGF-β for 4 h and then infected with 105 M. bovis organisms overnight. The cells were washed twice, stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD40 antibody, and analyzed by one-color flow cytometry. One representative experiment of three is shown. FL1-height represents FITC fluorescence. The thin lines indicate the basal levels of fluorescence with isotype control antibody, and the thick lines indicate monocyte CD40 expression.

IL-10 and TGF-β effects on IL-8 mRNA expression.

To correlate IL-8 protein secretion with levels of IL-8 mRNA, total mRNA was isolated from monocytes, pretreated with exogenous recombinant IL-10 or TGF-β for 4 h, and then stimulated with M. bovis. Controls were treated either with medium or with M. bovis alone. When reverse transcription-PCR was used at the transcriptional level, control monocytes treated with medium expressed undetectable or very low constitutive levels of IL-8 mRNA, whereas M. bovis triggered significant IL-8 mRNA expression in human monocytes (Fig. 4A). These data confirmed the ELISA results showing that M. bovis triggers significant IL-8 production. It is important to note that cells treated with M. bovis exhibited a smaller band when pretreated with IL-10 (Fig. 4A), whereas TGF-β appeared to have no significant effect on M. bovis-induced IL-8 mRNA expression. To compare the relative expression of IL-8 RNA with that of the control gene, the intensity of the band was analyzed and the ratio of IL-8 to GAPDH was calculated. As shown in Fig. 4B, the presence of IL-10 inhibited IL-8 expression, which was also consistent with the amounts of IL-8 protein. Higher concentrations of TGF-β did not enhance inhibition (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cytokine regulation of IL-8 mRNA expression in M. bovis-infected monocytes. (A) Cells were pretreated with IL-10 or TGF-β for 4 h and then infected with 105 M. bovis organisms overnight (IL-10 +M.bovis and TGF-β+M.bovis). Controls were treated either with medium (Med) or with M. bovis alone (M.bovis). Total RNA was isolated from the cells and subjected to reverse transcription-PCR analysis. GAPDH served as an internal control. (B) IL-8 levels were quantified by densitometry relative to GAPDH. The results are from one of three independent experiments with similar results. +, present; −, absent.

To examine the regulation of IL-8 production in monocytes by endogenous IL-10 or TGF-β, monocytes were pretreated with increasing concentrations of a neutralizing anti-IL-10 or anti-TGF-β antibody starting 1 h before and continuing throughout the infection period (0 to 24 h). As shown in Fig. 5 A, neutralization of endogenous IL-10 starting 1 h before infection appeared to enhance IL-8 protein in a dose-dependent manner. However, the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The mean levels of IL-8 were unaffected by TGF-β neutralizing antibody (Fig. 5B). These findings indicate that coexpression of IL-10 or TGF-β by M. bovis-infected monocytes has a minimal role in regulating IL-8 secretion.

FIG. 5.

Effects of anti-IL-10 and anti-TGF-β on M. bovis-induced IL-8 production. Monocytes were preincubated in culture medium in the presence of different amounts of an anti-IL-10 antibody (A) or anti-TGF-β (B). An isotype-matched control antibody was used as a negative control. M. bovis organisms (105) were added to single cultures, and incubation continued for 24 h. The supernatants were collected and filtered, and IL-8 levels were measured by ELISA. The results are the means + SEM of five different experiments. +, present; −, absent.

DISCUSSION

Protective immunity against mycobacterial infections requires activated monocytes and T cells. This activation takes place in a complex cytokine environment where proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8, are balanced by inhibitory cytokines, such as TGF-β and IL-10. Inhibitory activities of IL-10 for human and mouse immune responses have been documented in numerous studies, including antigen processing and presentation, costimulatory function, and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (6, 16, 28). Although IL-10 has been reported to inhibit IL-8 production by LPS-activated mononuclear cells (4, 5), its regulatory role in M. bovis-induced IL-8 production is not known. This study demonstrates for the first time that M. bovis-induced secretion of IL-8 is particularly sensitive to inhibition by IL-10. In addition, the specificity of the observed inhibition was confirmed, since the addition of an anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody completely reversed this inhibitory effect. Furthermore, the finding that exogenous recombinant IL-10 has a significant inhibitory effect on M. bovis-induced IL-8 protein secretion by human monocytes correlated with mRNA IL-8 levels. Such an inhibition is in agreement with the concept that IL-10 deactivates macrophages (27, 33).

A surprising and counterintuitive finding was that TGF-β did not significantly inhibit M. bovis-stimulated IL-8 production. This finding contrasts with recent studies reporting that addition of TGF-β to cell cultures before LPS or IL-1β stimulation inhibited the secretion of IL-8 (8, 23, 29). One possible explanation is that the effect of TGF-β on IL-8 secretion may depend on the stimulus. It is important to note that TGF-β was indeed implicated in the regulation of monocyte function, since our results demonstrated down-regulation of CD40 expression on monocytes, indicating a biologically active TGF-β. These results are in agreement with a previous report of the role of this cytokine in down-regulating costimulatory molecules (20) and at the same time are consistent with other reports indicating that TGF-β is less effective than IL-10 in directly inhibiting cytokine expression (32). On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that IL-10 synergizes with TGF-β to inhibit macrophage antimicrobial activity (2, 30, 31). In our study, no synergy between IL-10 and TGF-β was observed. However, our data do not allow us to exclude the possibility that IL-10 synergizes with other cytokines to regulate IL-8 production.

Significantly, we demonstrated that IL-10 has an important role in the regulation of M. bovis-induced IL-8 expression in human monocytes. This may be relevant, as IL-8 is an important chemoattractant for neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells in a human system of mycobacterial infection, and these cells are central components of the granulomatous response to M. tuberculosis (15, 18, 22).

The mechanism(s) of IL-10-induced inhibition of M. bovis-induced IL-8 secretion is still unknown. Our data provide evidence that IL-10 could act on IL-8 production, at least in part, in a direct fashion through down-regulation of IL-8 gene transcription. Recently, studies of the transcriptional control of the IL-8 gene suggest that gene activation is differentially regulated in an NF-κB-dependent manner (17, 26). Experiments are under way in our laboratory to thoroughly address the relationship between NF-κB and IL-8 secretion in human cells infected with M. bovis. In addition to a direct effect of IL-10 on cells, mycobacterial uptake by monocytes was not affected by pretreatment with IL-10 (Table 1). Therefore, treatment with IL-10 during uptake could not explain decreased IL-8 production.

In conclusion, this study shows that while M. bovis up-regulates the production of IL-8 by human monocytes at a protein and a transcriptional level, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 may inhibit IL-8 synthesis at that same level. The data presented here indicate that in mycobacterial functions, IL-10 plays an important role in the cytokine network by inhibiting IL-8 production. It remains to be established under which circumstances IL-10 plays a significant regulatory role in vivo. However, our results may represent an important mechanism for the down-regulation of the protective immune response to M. bovis BCG.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Coordinación General de Estudios de Posgrado e Investigación (CGPI) for their financial support of this work. P.M.-S. is an EDI, COFAA, and SIN fellow.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baggiolini, M., B. Dewald, and B. Moser. 1994. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines: CXC and CC chemokines. Adv. Immunol. 55:97-179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, C. C., and A. Manning. 1996. TGF-β1, IL-10, and IL-4 differentially modulate the cytokine-induced expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in human endothelial cells. Cytokine 8:58-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Waal Malefyt, R., J. Abrams, B. Bennett, C. Fidgor, and J. E. de Vries. 1991. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 174:1209-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Waal Malefyt, R., C. Fidgor, R. Huijbens, S. Mohan-Peterson, B. Bennett, J. Culpepper, W. Dang, G. Zurawski, and J. E. de Vries. 1993. Effects of IL-13 on phenotype, cytokine production, and cytotoxic function of human monocytes. Comparison with IL-4 and modulation by IFN-γ or IL-10. J. Immunol. 151:6370-6381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Waal Malefyt, R., J. Haanen, H. Spits, M. G. Roncarolo, A. te Velde, C. Fidgor, K. Johnson, R. Kastelein, H. Yssel, and J. E. de Vries. 1991. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J. Exp. Med. 174:915-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dlugovitzky, D., A. Torres-Morales, L. Rateni, M. A. Farroni, C. Largacha, O. Molteni, and O. Bottasso. 1997. Circulating profile of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in tuberculosis patients with different degrees of pulmonary involvement. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 18:203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich, L. C., S. Hu, W. S. Sheng, R. L. Sutton, G. L. Rockswold, P. K. Peterson, and C. Chao. 1998. Cytokine regulation of human microglial cell IL-8 production. J. Immunol. 160:1944-1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiorentino, D. F., A. Zlotnik, T. R. Mosmann, M. Howard, and A. O'Garra. 1991. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J. Immunol. 147:3815-3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiorentino, D. F., A. Zlotnik, P. Vieira, T. R. Mosmann, M. Howard, K. W. Moore, and A. O'Garra. 1991. IL-10 acts on the antigen-presenting cell to inhibit cytokine production by Th1 cells. J. Immunol. 146:3444-3451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedland, J. S., J. C. Hartley, C. G. Hartley, R. J. Shattock, and G. E. Griffin. 1995. Inhibition of ex vivo proinflammatory cytokine secretion in fatal Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 100:233-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedland, J. S., D. G. Remick, R. J. Shattock, and G. E. Griffin. 1992. Secretion of interleukin-8 following phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by human monocyte cell lines. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:1373-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch, C. S., R. Hussain, Z. Toossi, G. Dawood, F. Shahid, and J. J. Ellner. 1996. Cross-modulation by transforming growth factor beta in human tuberculosis: suppression of antigen-driven blastogenesis and interferon γ production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3193-3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones, G. S., H. S. Amirault, and B. R. Anderson. 1990. Killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by neutrophils: a nonoxidative process. J. Infect. Dis. 162:700-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasahara, K., T. Tobe, M. Tomita, N. Mukaida, S. Shao-Bo, K. Matsushima, T. Yoshida, S. Sugihara, and K. Kobayashi. 1994. Selective expression of monocyte chemotactic and activating factor/monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in human blood monocytes by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 170:1238-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koppelman, B., J. J. Neefjes, J. E. de Vries, and R. De Waal Malefyt. 1997. Interleukin-10 down-regulates MHC class II alphabeta peptide complexes at the plasma membrane of monocytes by affecting arrival and recycling. Immunity 7:861-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunsch, C., and C. A. Rosenn. 1993. NF-κB subunit-specific regulation of the interleukin-8 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:6137-6142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurashima, K., N. Mukaida, M. Fujimura, M. Yasui, Y. Nakazumi, T. Matsuda, and K. Matsushima. 1997. Elevated chemokine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of tuberculosis patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155:1474-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen, C. G., A. O. Anderson, E. Appella, J. J. Oppenheim, and K. Matsushima. 1989. The neutrophil-activating protein (NAP-1) is also chemotactic for T lymphocytes. Science 243:1464-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, Y. J., Y. Han, H. T. Lu, V. Nguyen, H. Qin, P. H. Howe, B. A. Hocevar, J. M. Boss, R. M. Ransohoff, and E. N. Benveniste. 1997. TGF-beta suppresses IFN-gamma induction of class II MHC gene expression by inhibiting class II transactivator messenger RNA expression. J. Immunol. 158:2065-2075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letterio, J. J., and A. B. Roberts. 1998. Regulation of immune responses by TGF-beta. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:137-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, Y., M. Zhang, and P. F. Barnes. 1998. Chemokine production by a human alveolar epithelial cell line in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 66:1121-1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lügering, N., T. Kucharzik, H. Gockel, C. Sorg, R. Stoll, and W. Domschke. 1998. Human intestinal epithelial cells down-regulate IL-8 expression in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells; role of transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1). Clin. Exp. Immunol. 114:377-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Méndez-Samperio, P., E. Garcia-Martínez, M. Hernández-Garay, and M. Solis-Cardona. 1997. Depletion of endogenous interleukin-10 augments interleukin-1β secretion by Mycobacterium bovis BCG-reactive human cells. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:138-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore, K. W., A. O'Garra, R. de Waal Malefyt, P. Vieira, and T. R. Mosmann. 1993. Interleukin-10. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11:165-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukaida, N., S. Okamoto, Y. Ishikawa, and K. Matsushima. 1994. Molecular mechanisms of interleukin-8 gene expression. J. Leukoc. Biol. 56:554-558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oswald, I. P., T. A. Wynn, A. Sher, and S. L. James. 1992. Interleukin 10 inhibits macrophage microbicidal activity by blocking the endogenous production of tumor necrosis factor alpha required as a costimulatory factor for interferon gamma-induced activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8676-8680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ralph, P., I. Nakoinz, A. Sampson-Johannes, S. Fong, D. Lowe, H. Y. Min, and L. Lin. 1992. IL-10, T lymphocyte inhibitor of human blood cell production of IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor. J. Immunol. 148:808-814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, W. B., L. Noack, Y. Khew-Goodall, S. Isenmann, M. A. Vadas, and J. R. Gamble. 1996. Transforming growth factor-β1 inhibits the production of IL-8 and the transmigration of neutrophils through activated endothelium. J. Immunol. 157:360-368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toossi, Z., P. Gogate, H. Shiratsuchi, T. Young, and J. Ellner. 1995. Enhanced production of TGF-β by blood monocytes from patients with active tuberculosis and presence of TGF-β in tuberculous granulomatous lung lesions. J. Immunol. 154:465-473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toossi, Z., T. G. Young, L. E. Averill, B. D. Hamilton, H. Shiratsuchi, and J. J. Ellner. 1995. Induction of transforming growth factor β1 by purified protein derivative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 63:224-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, P., P. Wu, M. I. Siegal, R. W. Egan, and M. Billah. 1994. IL-10 inhibits transformation of cytokine genes in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Immunol. 153:811-816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willems, F., A. Marchant, J. Delville, C. Gérard, A. Delvaux, T. Velu, M. de Boer, and M. Goldman. 1994. Interleukin-10 inhibits B7 and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 expression on human monocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 24:1007-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. 1996. W. H. O. report on the tuberculosis epidemic. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 35.Zhang, Y., M. Broser, H. Cohen, M. Bodkin, K. Law, J. Reibman, and W. N. Rom. 1995. Enhanced interleukin-8 release and gene expression in macrophages after exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its components. J. Clin. Investig. 95:586-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]